Submitted:

22 October 2024

Posted:

25 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- To evaluate the level of Emotional Intelligence among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- To assess nurses' perceptions of their work-life quality amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

- To examine the level of preparedness among nurses for managing COVID-19 patients.

- To analyze the interplay between Emotional Intelligence, preparedness to care for COVID-19 patients and quality of work-life among nurses.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Study Instrument

- Demographic and Occupational Characteristics: Participants provided information on their demographic and occupational characteristics, including age, gender, marital status, educational level, nationality, work location, unit, job title, and working hours. In addition, the preparedness to care for COVID-19 patients information included previous COVID-19-related training, direct interaction with COVID-19 patients, perceived support, PPE availability, and stress levels.

- Emotional Intelligence Scale (EI (PcSc) Scale): The EI of participants was measured using the EI (PcSc) Scale [47] based on Goleman’s Emotional Intelligence Competency Model [17]. This 69-item scale assesses personal competence (self-awareness, self-motivation, and emotion regulation) and social competence (social awareness, social skills, and emotional receptivity), scored on a 5-point Likert scale. Higher scores reflect greater emotional intelligence. The scale has demonstrated strong reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.91).

- Quality of Nursing Work Life (QNWL) Survey: The Quality of Nursing Work Life was assessed using a modified version of Brooks' Quality of Nursing Work Life Survey [48]. This 42-item survey covers four dimensions: work life, work context, work design, and work world, rated on a 5-point Likert scale. For this study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.95, indicating excellent reliability.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Method of Data Collection

- Adoption of Tools: Approval was sought from the original authors of the Emotional Intelligence (EI) Scale and Brooks' Quality of Nursing Work Life Survey to use and adapt their instruments for this study. Correspondence was initiated, and written consent was obtained, ensuring adherence to copyright regulations.

- Ethical Approval: Ethical clearance was obtained from the Research Ethics Committees in the Ministry of Health, ensuring compliance with national ethical guidelines for research involving human subjects. The research proposal was submitted for review, and feedback was incorporated before final approval was granted.

- Administrative Permissions: Official approval was secured from the administration of each participating hospital. This involved presenting the study’s objectives, methodology, and potential benefits to nursing staff and hospital management to ensure support and cooperation during the data collection process.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics:

3.2. Preparedness to Care for COVID-19 Patients

3.3. Emotional Intelligence Among Nurses

3.4. Quality of Work Life During the Pandemic

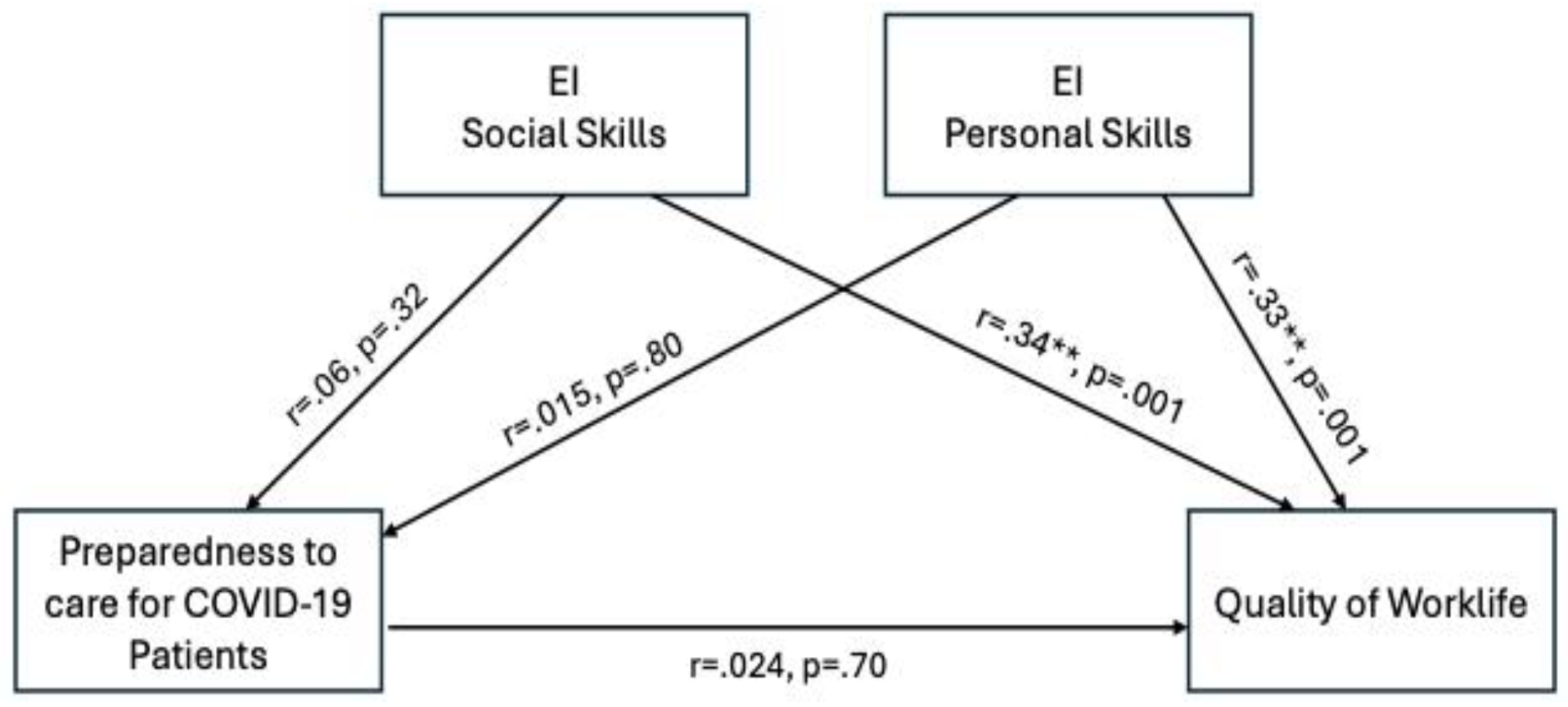

3.5. Correlation Between Emotional Intelligence, Preparedness, and Quality of Work Life

3.6. Moderation Effect of Emotional Intelligence

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Informed Consent Statement

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Drigas, A.S.; Papoutsi, C. A New Layered Model on Emotional Intelligence. Behavioral Sciences 2018, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacCann, C.; Fogarty, G.J.; Zeidner, M.; Roberts, R.D. Coping Mediates the Relationship between Emotional Intelligence (EI) and Academic Achievement. Contemporary Educational Psychology 2011, 36, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kord Tamini, B.; K. Chadha, N. Emotional Intelligence and Quality of Work Life between Iranian and Indian University Employees: A Cross–Cultural Study. International Journal of Psychology (IPA) 2018, 12, 91–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M. Emotional Intelligence. Global Leadership Foundation.

- Al-Oweidat, I.; Shosha, G.A.; Baker, T.A.; Nashwan, A.J. The Relationship between Emotional Intelligence and Organizational Commitment among Nurses Working in Governmental Hospitals in Jordan. BMC Nursing 2023, 22, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, M.I.; Khalifeh, A.; Oweidat, I.; Nashwan, A.J. The Relationship between Emotional Intelligence, Job Satisfaction, and Organizational Commitment among First-Line Nurse Managers in Qatar. Journal of Nursing Management 2024, 2024, 5114659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chams, N.; Chams, S.; Badran, R.; Shams, A.; Araji, A.; Raad, M.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Stroberg, E.; Duval, E.J.; Barton, L.M.; et al. COVID-19: A Multidisciplinary Review. Front Public Health 2020, 8, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydogdu, A.L.F. Ethical Dilemmas Experienced by Nurses While Caring for Patients during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Integrative Review of Qualitative Studies. J Nurs Manag 2022, 30, 2245–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, P.; Payal; Nain, P. ; Pooja; Rana, P.; Verma, P.; Yadav, P.; Poonam; Prerna; Kashyap, G.; et al. Perceived Risk of Infection, Ethical Challenges and Motivational Factors among Frontline Nurses in Covid-19 Pandemic: Prerequisites and Lessons for Future Pandemic. BMC Nursing 2024, 23, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, J.; Jackson, D.; Usher, K. The Potential for COVID-19 to Contribute to Compassion Fatigue in Critical Care Nurses. J Clin Nurs 2020, 29, 2762–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabra, M.A.; Mohammed, K.A.E.; Hegazy, M.N.; Hendi, A.E. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms among Nursing Staff Who Provided Direct Care to COVID-19 Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Middle East Current Psychiatry, Ain Shams University 2022, 29, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperling, D. Ethical Dilemmas, Perceived Risk, and Motivation among Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nurs Ethics 2021, 28, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Thobaity, A.; Alshammari, F. Nurses on the Frontline against the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Integrative Review. Dubai Medical Journal 2020, 3, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Edirippuige, S.; Snoswell, C.L.; Bambling, M.; Liu, D.; Smith, A.C.; Bai, X. It Was Like Going to a Battlefield: Lived Experience of Frontline Nurses Supporting Two Hospitals in Wuhan During the COVID-19 Pandemic. SAGE Open Nursing 2024, 10, 23779608241253977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Mao, A.; Wang, J.; Okoli, C.T.C.; Zhang, Y.; Shuai, H.; Lin, M.; Chen, B.; Zhuang, L. From Twisting to Settling down as a Nurse in China: A Qualitative Study of the Commitment to Nursing as a Career. BMC Nursing 2020, 19, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasek, R.A. Job Demands, Job Decision Latitude, and Mental Strain: Implications for Job Redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly 1979, 24, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goleman, D. Emotional Intelligence; 25th anniversary edition.; Bantam Books: New York, 2020; ISBN 978-0-553-90320-1. [Google Scholar]

- Soriano-Vázquez, I.; Cajachagua Castro, M.; Morales-García, W.C. Emotional Intelligence as a Predictor of Job Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Conflict Management in Nurses. Front. Public Health 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foji, S.; Vejdani, M.; Salehiniya, H.; Khosrorad, R. The Effect of Emotional Intelligence Training on General Health Promotion among Nurse. J Educ Health Promot 2020, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, L. Nurse Characteristics and the Effects on Quality. Nurs Clin North Am 2020, 55, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galanis, P.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Moisoglou, I.; Kalogeropoulou, M.; Gallos, P.; Vraka, I. Emotional Intelligence Protects Nurses against Quiet Quitting, Turnover Intention, and Job Burnout. AIMS Public Health 2024, 11, 601–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuza, H.; Lukito, H. The Effect of Emotional Intelligence and Job Stress on Nurse Commitment with Satisfaction as a Mediation Variable. AMAR (Andalas Management Review) 2022, 6, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regy, M.M.; Ramesh, N. Emotional Intelligence and Occupational Stress Among Nursing Professionals in Tertiary Care Hospitals of Bangalore: A Multicentric, Cross-Sectional Study. Indian Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2024, 28, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimi, L.; Leggat, S.G.; Bartram, T.; Afshari, L.; Sarkeshik, S.; Verulava, T. Emotional Intelligence: Predictor of Employees’ Wellbeing, Quality of Patient Care, and Psychological Empowerment. BMC Psychology 2021, 9, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljarboa, B.E.; Pasay An, E.; Dator, W.L.T.; Alshammari, S.A.; Mostoles, R.; Uy, M.M.; Alrashidi, N.; Alreshidi, M.S.; Mina, E.; Gonzales, A. Resilience and Emotional Intelligence of Staff Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare (Basel) 2022, 10, 2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathaya, A.D.; Hidayat, N.; Dalimunthe, S. The Effect of Emotional Intelligence with Work-Life Balance and Burnout on Job Satisfaction. Journal of Business and Behavioural Entrepreneurship 2022, 6, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajigharajeh, S.; Safari, M.; Abadi, T.S.H.; Abadi, S.S.H.; Kargar, M.; Panahi, M.; Hasani, M.; Ghaedchukamei, Z. Determining the Relationship between Emotional Intelligence and Interpersonal Sensitivity with Quality of Work Life in Nurses. J Educ Health Promot 2021, 10, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghdadi, N.A.; Sankarapandian, C.; Arulappan, J.; Taani, M.H.; Snethen, J.; Andargeery, S.Y. The Association between Nursing Students’ Happiness, Emotional Intelligence, and Perceived Caring Behavior in Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia. Healthcare (Basel) 2023, 12, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahin, M.A.; Al-Dubai, S.A.R.; Abdoh, D.S.; Alahmadi, A.S.; Ali, A.K.; Hifnawy, T. Burnout among Nurses Working in the Primary Health Care Centers in Saudi Arabia, a Multicenter Study. AIMS Public Health 2020, 7, 844–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almansour, A.M. The Level of Emotional Intelligence among Saudi Nursing Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Belitung Nurs J 2023, 9, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razu, S.R.; Yasmin, T.; Arif, T.B.; Islam, M.S.; Islam, S.M.S.; Gesesew, H.A.; Ward, P. Challenges Faced by Healthcare Professionals During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Inquiry From Bangladesh. Front Public Health 2021, 9, 647315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; National Academy of Medicine; Committee on the Future of Nursing 2020–2030. The Future of Nursing 2020-2030: Charting a Path to Achieve Health Equity; Flaubert, J.L., Le Menestrel, S., Williams, D.R., Wakefield, M.K., Eds.; National Academies Press (US): Washington (DC), 2021; ISBN 978-0-309-68506-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, M.; Smith, E.; Mills, B. Work-Based Concerns of Australian Frontline Healthcare Workers during the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Aust N Z J Public Health 2022, 46, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbaein, T.J.; Alharbi, K.K.; Alfahmi, A.A.; Alharthi, K.O.; Monshi, S.S.; Alzahrani, A.M.; Alkabi, S. Makkah Healthcare Cluster Response, Challenges, and Interventions during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study. J Infect Public Health 2024, 17, 975–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altwaijri, Y.; Bilal, L.; Almeharish, A.; BinMuammar, A.; DeVol, E.; Hyder, S.; Naseem, M.T.; Alfattani, A.; AlShehri, A.A.; Almatrafi, R. Psychological Distress Reported by Healthcare Workers in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0268976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheerah, H.A.; Almuzaini, Y.; Khan, A. Public Health Challenges in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Literature Review. Healthcare (Basel) 2023, 11, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goniewicz, M.; Khorram-Manesh, A.; Włoszczak-Szubzda, A.; Lasota, D.; Al-Wathinani, A.M.; Goniewicz, K. Influence of Experience, Tenure, and Organisational Preparedness on Nurses’ Readiness in Responding to Disasters: An Exploration during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Glob Health 2023, 13, 06034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, A.M.; Saber, E.H.; Gabra, S.F. Relation between Compassion Fatigue, Pandemic Emotional Impact, and Time Management among Nurses at Isolation Hospitals during COVID- 19. Minia Scientific Nursing Journal 2022, 012, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mutair, A.; Al Bazroun, M.I.; Almusalami, E.M.; Aljarameez, F.; Alhasawi, A.I.; Alahmed, F.; Saha, C.; Alharbi, H.F.; Ahmed, G.Y. Quality of Nursing Work Life among Nurses in Saudi Arabia: A Descriptive Cross-Sectional Study. Nurs Rep 2022, 12, 1014–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, M.F.; Basheer, A.F.; Alharbi, W.S.; Aljohni, E.A. Quality of Nursing Work Life and Level of Stress across Different Regions in Saudi Arabia- a Cross Sectional Study. J Nurs Manag 2022, 30, 3208–3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradian, S.T.; Movahedi, M.; Rad, M.G.; Saeid, Y. Emotional Intelligence of Nurses Caring for COVID-19 Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 2022, 36, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, F.; Yang, Q.; Rūtelionė, A.; Bhutto, M.Y. Virtual Leadership and Nurses’ Psychological Stress during COVID-19 in the Tertiary Hospitals of Pakistan: The Role of Emotional Intelligence. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhawatmeh, H.; Alsholol, R.; Dalky, H.; Al-Ali, N.; Albataineh, R. Mediating Role of Resilience on the Relationship between Stress and Quality of Life among Jordanian Registered Nurses during COVID-19 Pandemic. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jawabreh, N. The Relationship Between Emotional Intelligence and Coping Behaviors among Nurses in the Intensive Care Unit. SAGE Open Nursing 2024, 10, 23779608241242853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turjuman, F.; Alilyyani, B. Emotional Intelligence among Nurses and Its Relationship with Their Performance and Work Engagement: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Nursing Management 2023, 2023, 5543299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, S.; Singh, Ms.N. Development of the Emotional Intelligence Scale. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT & INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY 2013, 8, 1252–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, B.A.; Storfjell, J.; Omoike, O.; Ohlson, S.; Stemler, I.; Shaver, J.; Brown, A. Assessing the Quality of Nursing Work Life. Nurs Adm Q 2007, 31, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abualruz, H.; Hayajneh, F.; Othman, E.H.; Abu Sabra, M.A.; Khalil, M.M.; Khalifeh, A.H.; Yasin, I.; Alhamory, S.; Zyoud, A.H.; Abousoliman, A.D. The Relationship between Emotional Intelligence, Resilience, and Psychological Distress among Nurses in Jordan. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 2024, 51, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, W.; Han, G.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Q.; Pang, X. Correlation between Emotional Intelligence and Negative Emotions of Front-Line Nurses during the COVID-19 Epidemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Clin Nurs 2021, 30, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosentino, C.; Foà, C.; Bertuol, M.; Cappi, V.; Riboni, S.; Rossi, S.; Artioli, G.; Sarli, L. The Impact of the Alterations in Caring for COVID-19 Patients on Compassion Satisfaction and Compassion Fatigue in Italian Nurses: A Multi Method Study. Acta Biomed 2022, 93, e2022190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, J.M.; Magbee, T.; Yoder, L.H. The Experiences of Critical Care Nurses Caring for Patients with COVID-19 during the 2020 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study. Appl Nurs Res 2021, 59, 151418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcomini, I.; Agus, C.; Milani, L.; Sfogliarini, R.; Bona, A.; Castagna, M. COVID-19 and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder among Nurses: A Descriptive Cross-Sectional Study in a COVID Hospital. Med Lav 2021, 112, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balay-Odao, E.M.; Alquwez, N.; Inocian, E.P.; Alotaibi, R.S. Hospital Preparedness, Resilience, and Psychological Burden Among Clinical Nurses in Addressing the COVID-19 Crisis in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Front Public Health 2020, 8, 573932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billings, J.; Ching, B.C.F.; Gkofa, V.; Greene, T.; Bloomfield, M. Experiences of Frontline Healthcare Workers and Their Views about Support during COVID-19 and Previous Pandemics: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Meta-Synthesis. BMC Health Services Research 2021, 21, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasanpour Dehkordi, A.; Mirfendereski, S.; Hasanpour Dehkordi, A. Anxiety, Quality of Work Life and Fatigue of Iran Health Care Providers in Health Care Centers in COVID-19 Pandemic. Przegl Epidemiol 2021, 75, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Fernández, M.D.; Ramos-Pichardo, J.D.; Ibáñez-Masero, O.; Cabrera-Troya, J.; Carmona-Rega, M.I.; Ortega-Galán, Á.M. Compassion Fatigue, Burnout, Compassion Satisfaction and Perceived Stress in Healthcare Professionals during the COVID-19 Health Crisis in Spain. J Clin Nurs 2020, 29, 4321–4330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simms, L.; Ottman, K.E.; Griffith, J.L.; Knight, M.G.; Norris, L.; Karakcheyeva, V.; Kohrt, B.A. Psychosocial Peer Support to Address Mental Health and Burnout of Health Care Workers Affected by COVID-19: A Qualitative Evaluation. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20, 4536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Fuentes, M.D.C.; Molero Jurado, M.D.M.; Gázquez Linares, J.J.; Oropesa Ruiz, N.F. The Role of Emotional Intelligence in Engagement in Nurses. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018, 15, 1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragadóttir, H.; Kalisch, B.J.; Flygenring, B.G.; Tryggvadóttir, G.B. The Relationship of Nursing Teamwork and Job Satisfaction in Hospitals. SAGE Open Nurs 2023, 9, 23779608231175027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, H.; Han, K.; Cho, H.; Ju, J. Nursing Teamwork Is Essential in Promoting Patient-Centered Care: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Nurs 2023, 22, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babapour, A.-R.; Gahassab-Mozaffari, N.; Fathnezhad-Kazemi, A. Nurses’ Job Stress and Its Impact on Quality of Life and Caring Behaviors: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Nurs 2022, 21, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Yrs) | 37.47 | 8.09 | |

| Years of Experience (Yrs) | 8. 43 | 6.33 | |

| Variable |

Frequency (N=267) |

Percentage (%) |

|

| Gender | Men | 14 | 5.6 |

| Women | 252 | 94.4 | |

| Marital Status | Single | 95 | 35.6 |

| Married | 159 | 59.6 | |

| Divorced | 8 | 3 | |

| Widowed | 5 | 1.9 | |

| Educational Level | Diploma | 65 | 24.3 |

| Bachelor | 183 | 68.5 | |

| Postgraduate1 | 19 | 7.1 | |

| Nationality | Saudis | 56 | 21 |

| Non-Saudis | 211 | 79 | |

| Working Unit | General wards | 115 | 43.1 |

| Critical Care Units | 63 | 23.6 | |

| Specialized Units | 89 | 33.3 | |

| Job Title | Bedside nurse | 236 | 88.4 |

| Nurse managers | 31 | 11.6 | |

| Working hours per week | More than 40 hours | 219 | 82 |

| From 30 to 40 hours | 39 | 14.6 | |

| Less than 30 hours | 9 | 3.4 |

| Variable | Frequency (N=267) |

Percentage (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Attending COVID-19 related Workshop(s) | Yes | 233 | 87.3 |

| No | 34 | 12.7 | |

| Direct interaction with COVID-19 patients | Yes | 225 | 84.3 |

| No | 42 | 15.7 | |

| Received proper support during the pandemic | Yes | 194 | 72.7 |

| No | 73 | 27.3 | |

| PPEs are necessity to care for COVID-19 patients | Necessary | 267 | 100 |

| Not necessary | 0 | 0 | |

| Reported level of stress to care for COVID-19 patients | Very stressful | 118 | 44.2 |

| Moderately stressful | 92 | 34.5 | |

| Slightly stressful | 45 | 16.9 | |

| Not stressful | 12 | 4.5 | |

| Overall preparedness | Ready | 204 | 76.4 |

| Not decided | 27 | 10.1 | |

| Not ready | 36 | 13.5 |

| Emotional Intelligence | Frequency (N=267) |

Percentage (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Personal competence | Good | 250 | 93.6 |

| Fair | 17 | 6.4 | |

| Poor | 0 | 0% | |

| Social competence | Good | 228 | 85.4 |

| Fair | 39 | 14.6 | |

| Poor | 0 | 0 |

| Variable | Frequency (N=267) |

Percentage (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of work life | Good | 190 | 71 |

| Fair | 77 | 29 | |

| Poor | 0 | 0 |

| Variables | Personal competence | Social competence | Preparedness | Quality of work |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal competence | - | |||

| Social competence | r = .52** p = .000 |

- | ||

| Preparedness | r = .015 p = 80 |

r = .060 p = .32 |

- | |

| Quality of work life | r = .33** p = .000 |

r = .34** p = .000 |

r = .024 p = .70 |

- |

| Regression | B | SEB | β | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preparedness | -.487 | .081 | -1.17 | .000 |

| Personal competence x preparedness | .080 | .021 | .578 | .000 |

| Social competence x preparedness | .094 | .032 | .665 | .000 |

| r = .41** | p = .000 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).