Submitted:

23 October 2024

Posted:

24 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

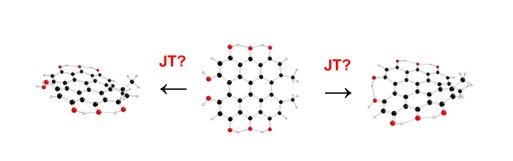

2. Theoretical Background

3. Results and Discussion

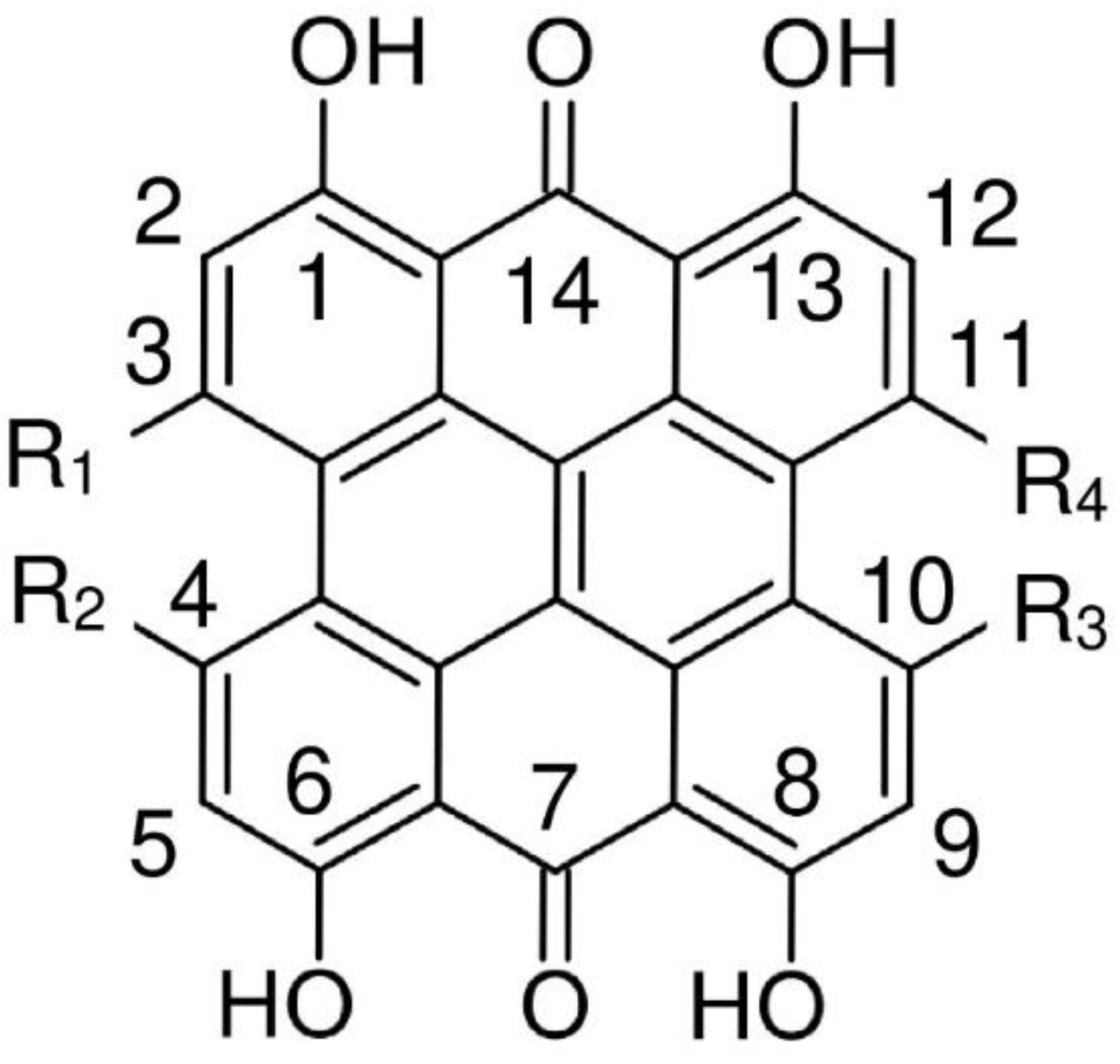

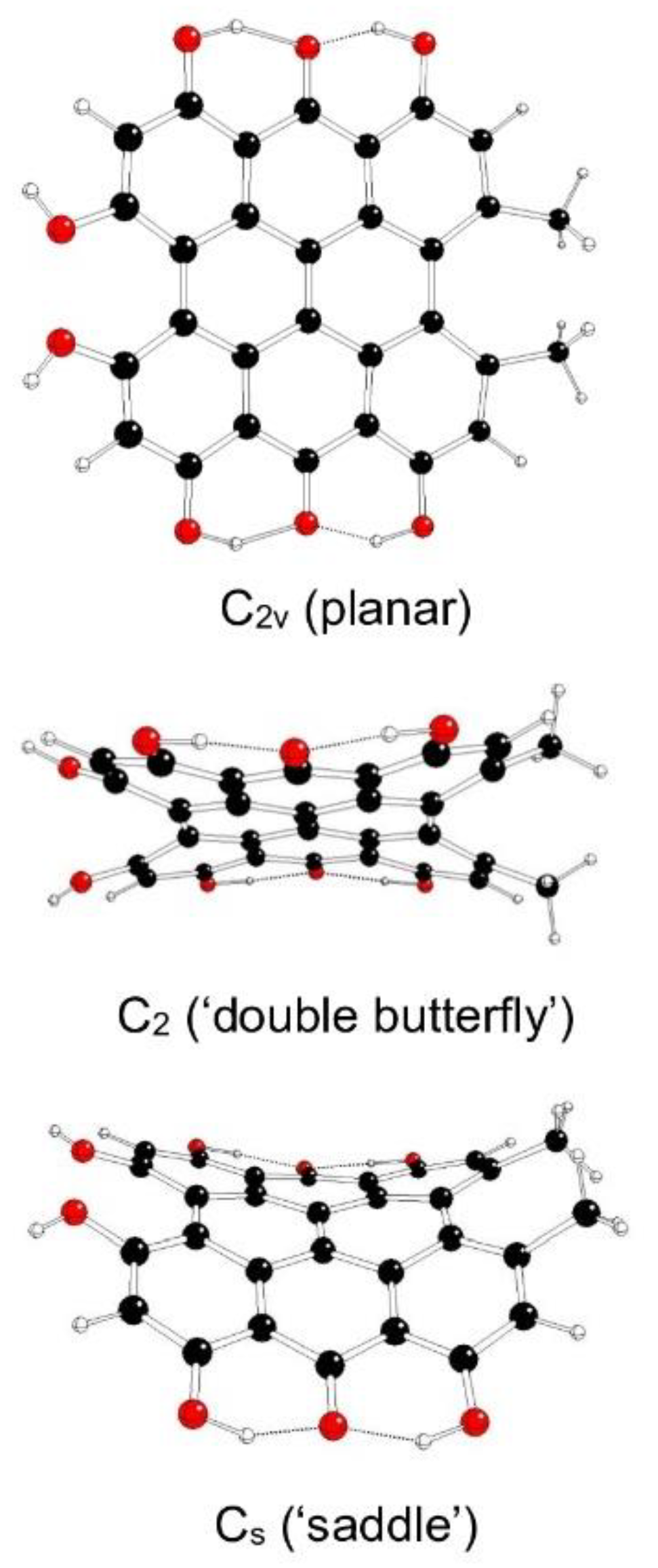

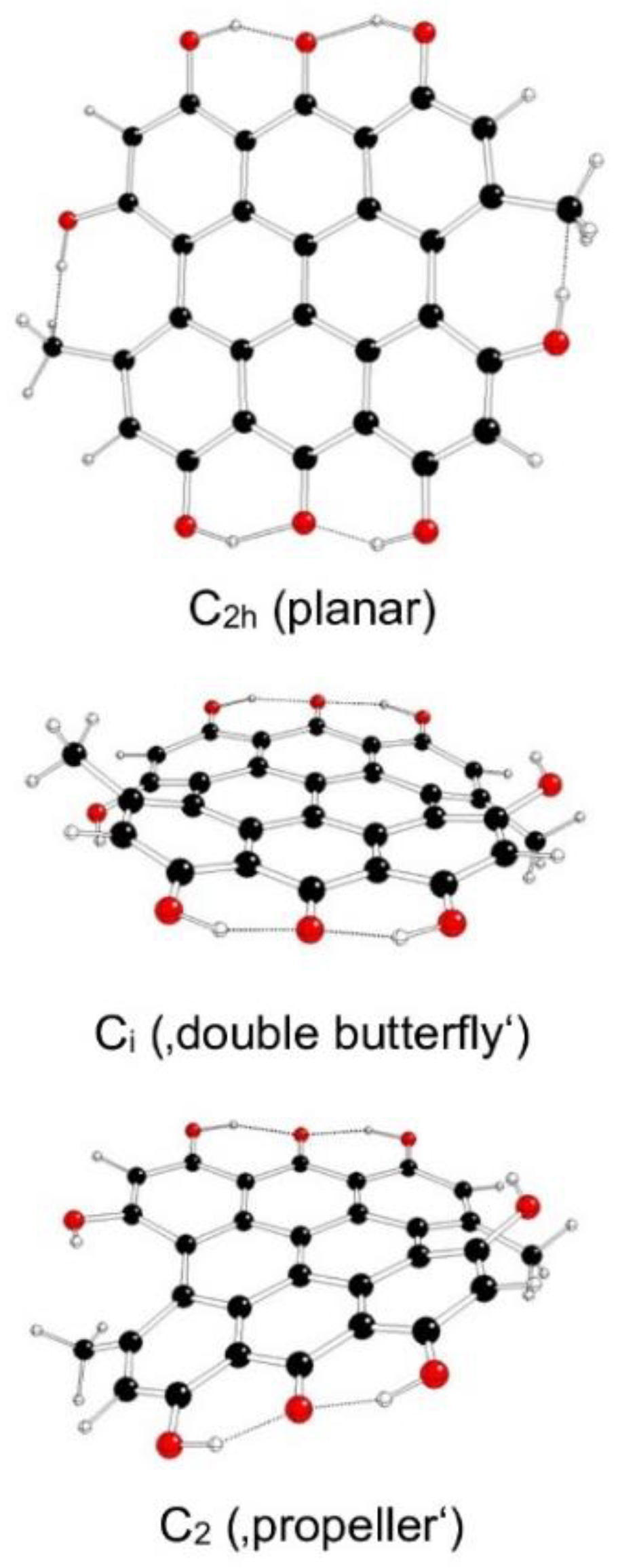

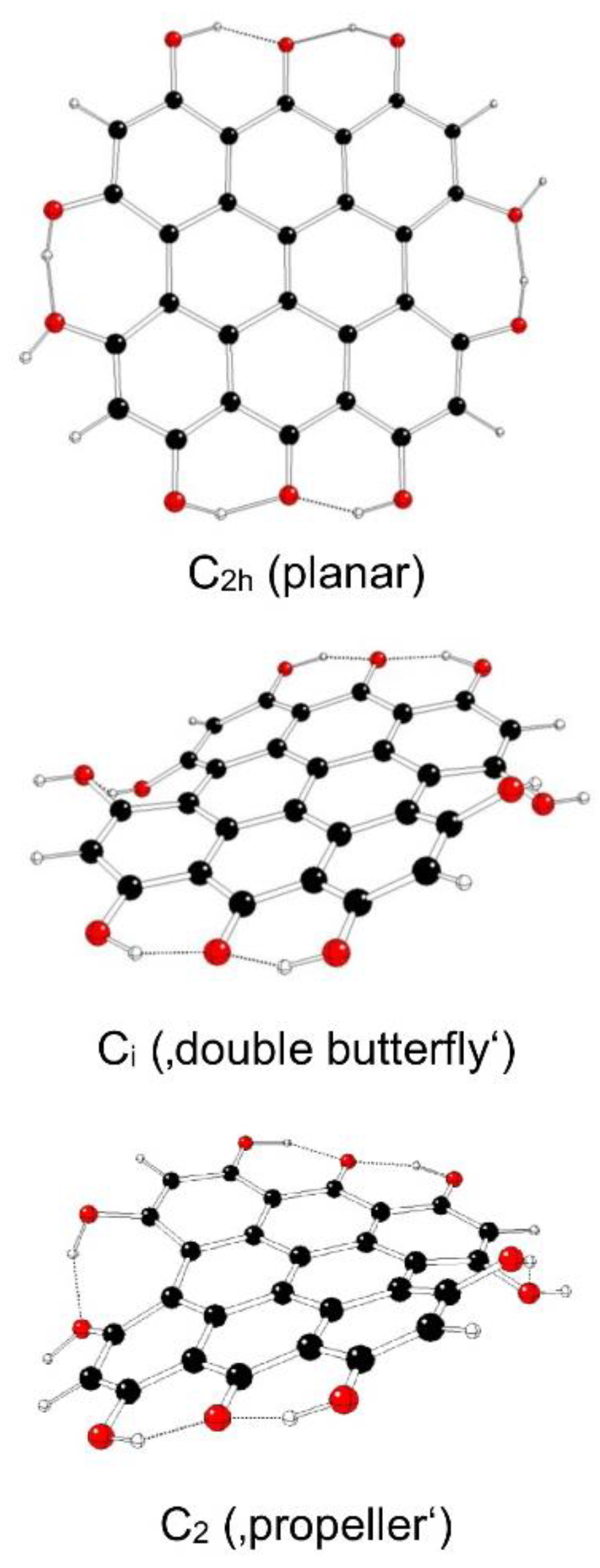

3.1. Hypericin (I)

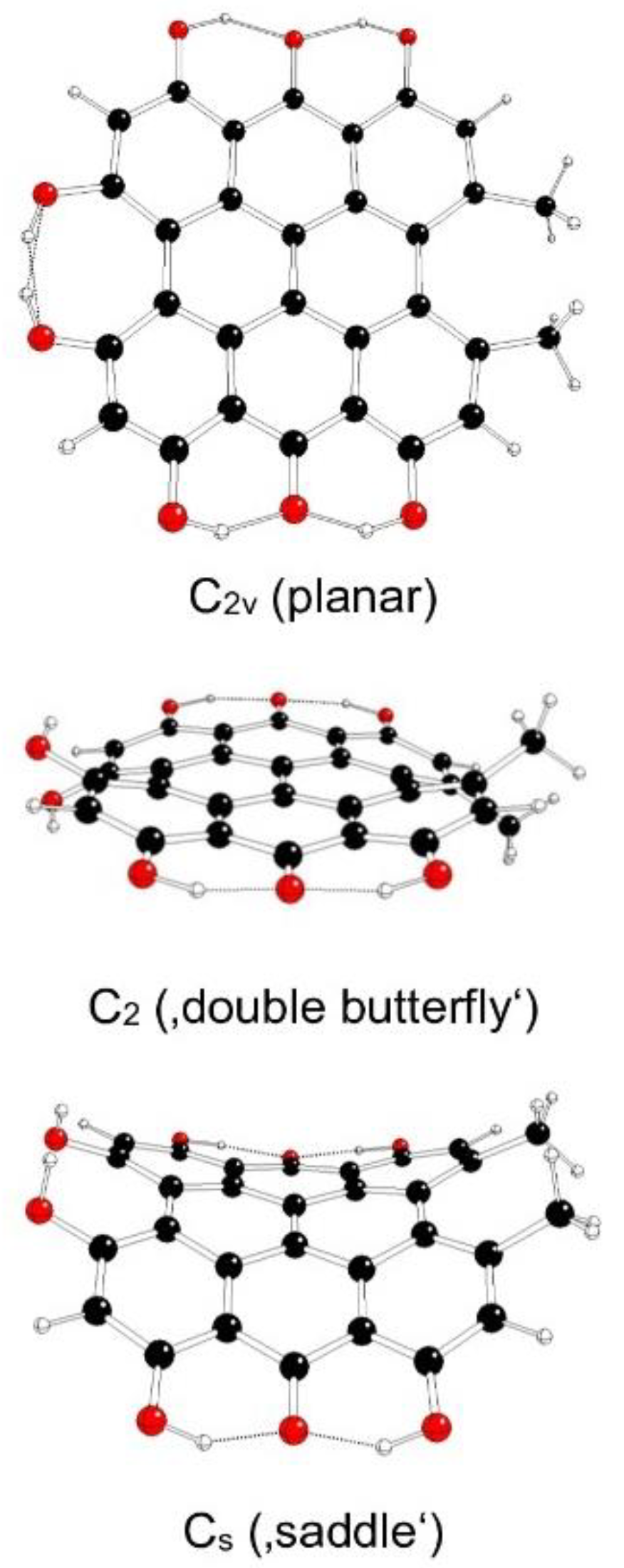

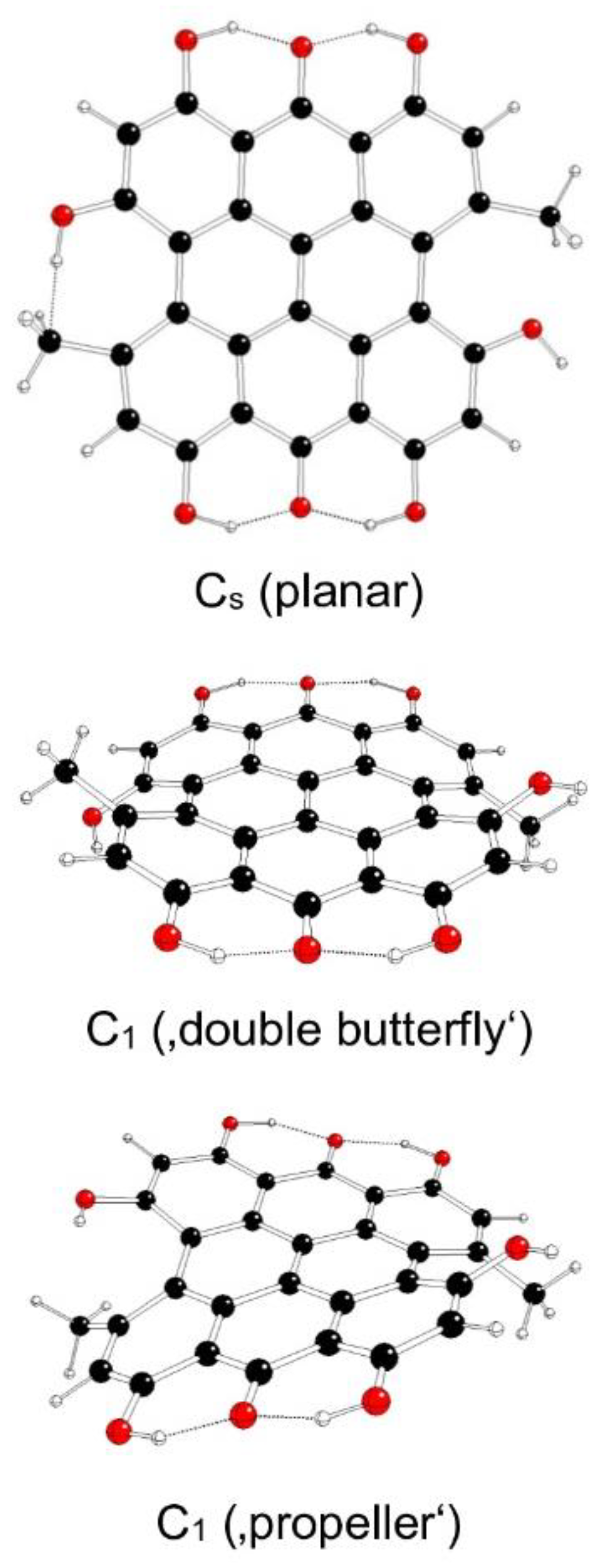

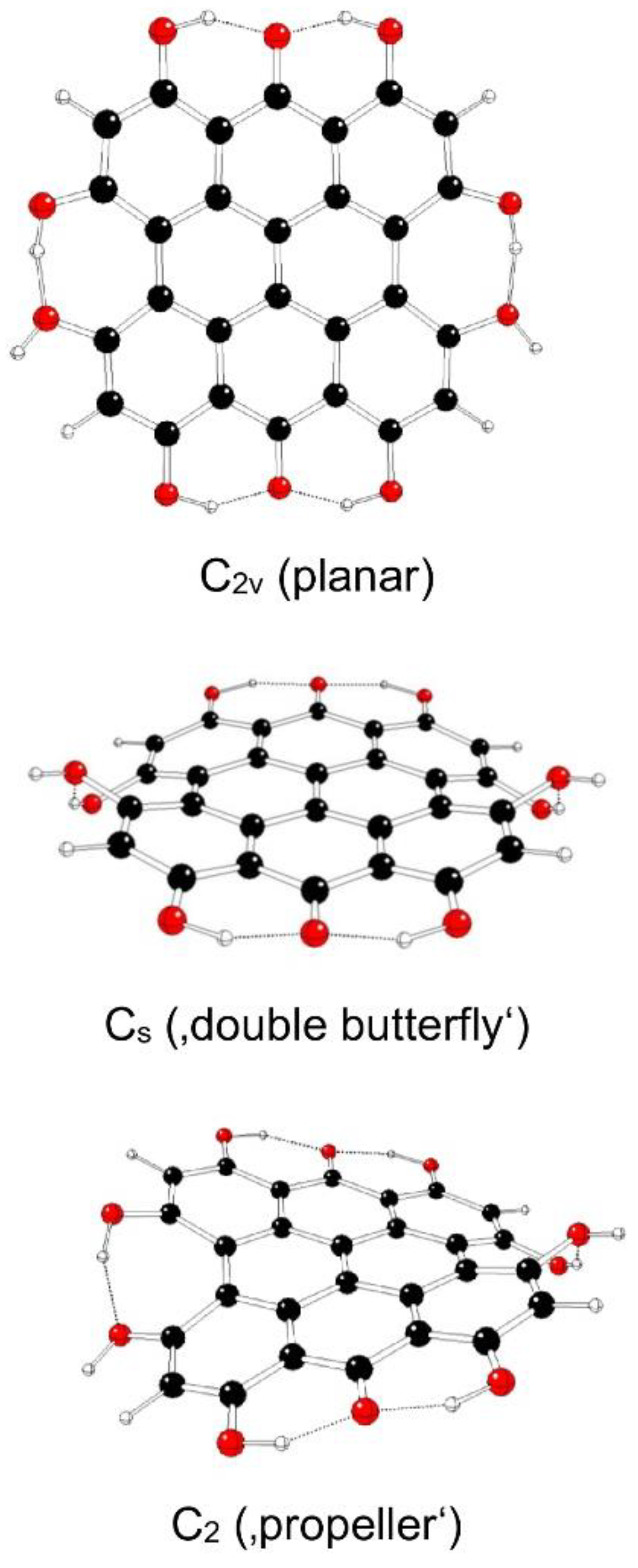

3.2. Isohypericin (II)

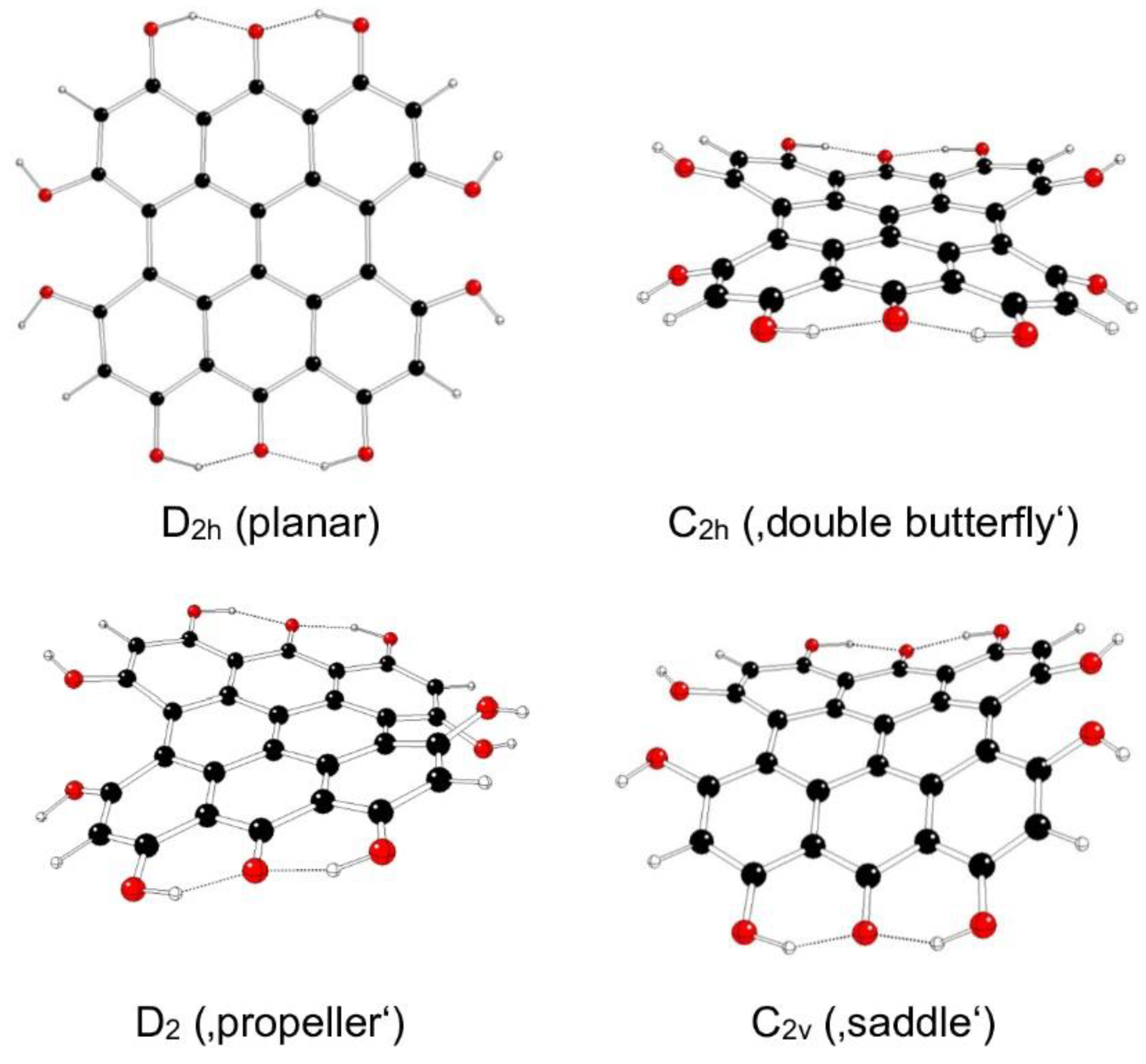

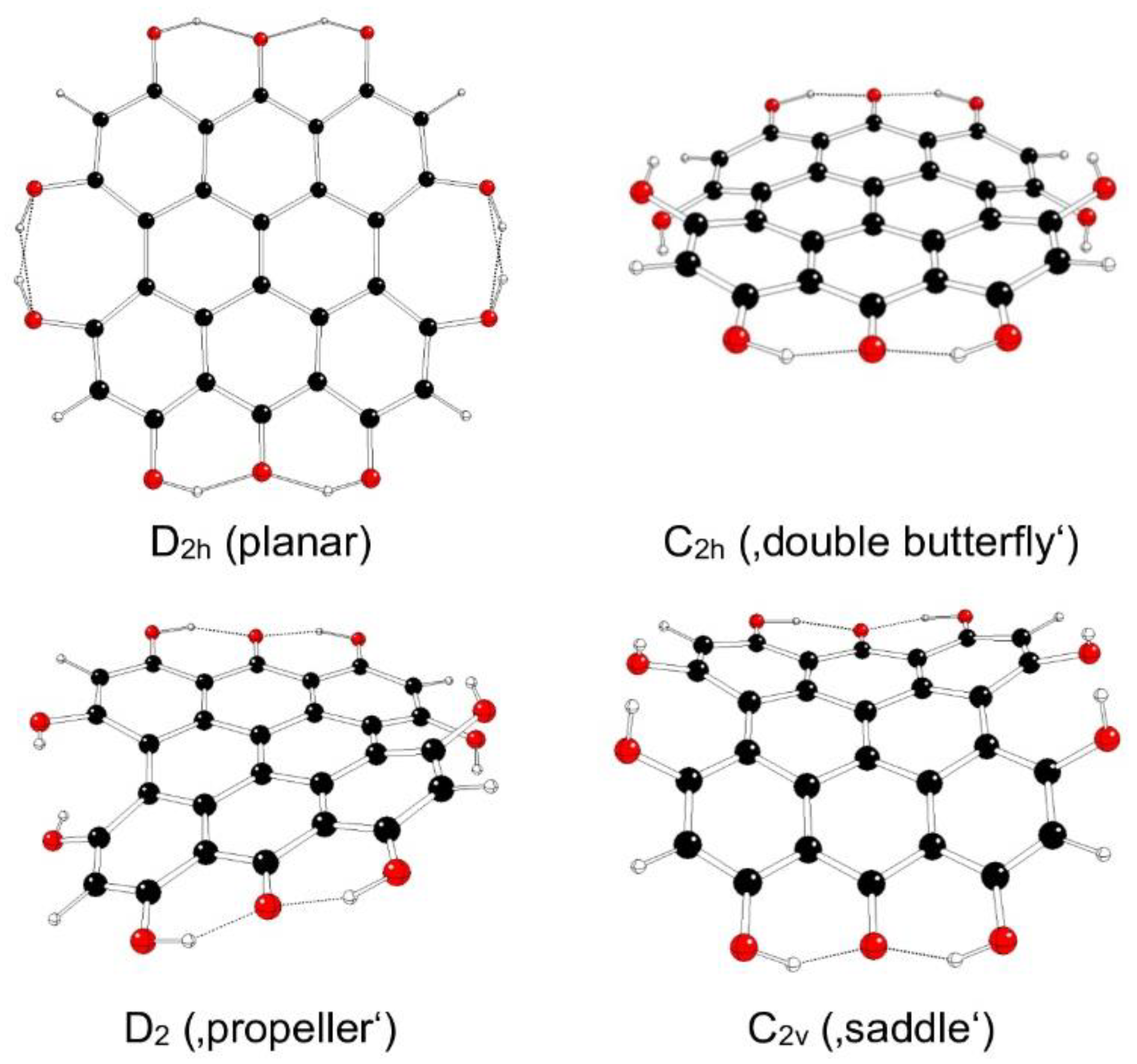

3.3. Fringelite D (III)

4. Method

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- Pandey, M.; Pandey, Ch.; Ahuja, R.; Kumar, R. Straining techniques for strain engineering of 2D materials towards flexible straintronic applications. Nano Energy 2023, 109, 108278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, S.; Atulasimha, J.; Barman, A. Magnetic straintronics: Manipulating the magnetization of magnetostrictive nanomagnets with strain for energy-efficient applications. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2021, 8, 041323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Bandari, V. K.; Schmidt, O. G. Molecular Electronics: Creating and Bridging Molecular Junctions and Promoting Its Commercialization. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2209088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, S.; Saka, S. K.; Xuan, F.; Yin, P. Molecular robotic agents that survey molecular landscapes for information retrieval. Nature Commun. 2024, 15, 3293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, M.; Gowtham, H.G.; Shilpa, N.; Krishnappa, H.K.N.; Ledesma, A.E.; Jain, A.S.; Shati, A.A.; Alfaifi, M.Y.; Elbehairi, S.E.I.; Achar, R.R.; Silina, E.; Stupin, V.; Ortega-Castro, J.; Frau, J.; Flores-Holguín, N.; Amruthesh, K. N.; Shivamallu, Ch.; Kollur, Sh. P.; Glossman-Mitnik, D. Exploration of Anti-HIV Phytocompounds against SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease: Structure-Based Screening, Molecular Simulation, ADME Analysis and Conceptual DFT Studies. Molecules 2022, 27, 8288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, D.; Frolow, F.; Kapinus, E.; Lavie, D.; Lavie, G.; Merueloc, D.; Mazur, Y. Acidic Properties of Hypericin and its Octahydroxy Analogue in the Ground and Excited States. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1994, 891–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrich,J. W.; Gordon, M. S.; Cagle, M. Structure and Energetics of Ground-State Hypericin: Comparison of Experiment and Theory. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 1647–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uličný, J.; Laaksonen, A. Hypericin, an intriguing internally heterogenous molecule, forms a covalent intramolecular hydrogen bond. Chem. Phys. Let. 2000, 319, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, R. C.; Eriksson, L. A. Theoretical study of hypericin. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 2005, 172, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Ji, H-F. ; Zhang, H-Y. Anion of hypericin is crucial to understanding the photosensitive features of the pigment. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Let. 2006, 16, 1414–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, R. C.; Eriksson, L. A. Photophysics, photochemistry, and reactivity: Molecular aspects of perylenequinone reactions. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2007, 6, 1089–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoaf, A. L.; Bayse, C. A. TD-DFT and structural investigation of natural photosensitive phenanthroperylene quinone derivatives. New J. Chem. 2016, 40, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanski, S.; Majerz, I. Aromaticity and Electron Density of Hypericin. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 2106–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siskos, M. G.; Choudhary, M. I.; Tzakos, A. G.; Gerothanassis, I. P. 1H NМR chemical shift assignment, structure and conformational elucidation of hypericin with the use of DFT calculations. The challenge of accurate positions of labile hydrogens. Tetrahedron 2016, 72, 8287–8293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetanovic Zobenica, K.; Lacnjevac, U.; Etinski, M.; Vasiljevic-Radovica, D.; Stanisavljev, D. Influence of the electron donor properties of hypericin on its sensitizing ability in DSSCs. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2019, 18, 2023–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Wackenhut, F.; Hauler, O.; Scholz, M.; zur Oven-Krockhaus, S.; Ritz, R. ; Adam, P-M.; Brecht, M., Ed.; Meixner, A. J. Hypericin: Single Molecule Spectroscopy of an Active Natural Drug. J. Phys. Chem. A 2020, 124, 2497−2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wackenhut, F.; Wang, L.; Hauler, O.; Roldao, J. C. ; Adam, P-M.; Brecht, M.; Gierschner, J.; Meixner, A. J. Direct Observation of Structural Heterogeneity and Tautomerization of Single Hypericin Molecules. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 1025–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Simone, B. C.; Mazzone, G.; Toscano, M.; Russo, N. On the origin of photodynamic activity of hypericin and its iodine-containing derivatives. J. Comput. Chem. 2022, 43, 2037–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murali, M.; Gowtham, H.G.; Shilpa, N.; Krishnappa, H.K.N.; Ledesma, A.E.; Jain, A.S.; Shati, A.A.; Alfaifi, M.Y.; Elbehairi, S.E.I.; Achar, R.R.; Silina, E.; Stupin, V.; Ortega-Castro, J.; Frau, J.; Flores-Holguín, N.; Amruthesh, K. N.; Shivamallu, Ch.; Kollur, Sh. P.; Glossman-Mitnik, D. Exploration of Anti-HIV Phytocompounds against SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease: Structure-Based Screening, Molecular Simulation, ADME Analysis and Conceptual DFT Studies. Molecules 2022, 27, 8288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peeters, S.; Losi, G.; Loehlé, S.; Righi, M.C. Aromatic molecules as sustainable lubricants explored by ab initio simulations. Carbon 2023, 203, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W-P. ; Wang, R-Q.; Zhang, Y-R.; Song, K.; Tian, Y.; Li, J-X.; Wang, G-Y.; Shi, G-F. HPLC, fluorescence spectroscopy, UV spectroscopy and DFT calculations on the mechanism of scavenging •OH radicals by Hypericin. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1274, 134472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bersuker, I. B. The Jahn-Teller Effect; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, U.K, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bersuker, I. B. Pseudo-Jahn−Teller Effect-A Two-State Paradigm in Formation, Deformation, and Transformation of Molecular Systems and Solids. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 1351–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewars, E. G. Computational Chemistry. Introduction to the Theory and Applications of Molecular and Quantum Mechanics. Third Edition 2016. Springer International Publishing: Switzerland, 2016.

- Ceulemans, A.; Beyens, D.; Vanquickenborne, L. G. Symmetry aspects of Jahn-Teller activity: structure and reactivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106, 5824–5837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, H. A.; Teller, E. Stability of polyatomic molecules in degenerate electronic states. I. Orbital degeneracy. Proc. R. Soc. London A 1937, 161, 220–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opik, U.; Pryce, M. H. L. Studies of the Jahn-Teller effect I. A survey of the static problem. Proc. R. Soc. London A 1957, 238, 425–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceulemans, A.; Vanquickenborne, L. G. The Epikernel Principle. Struct. Bonding 1989, 71, 125–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breza, M. Group-Theoretical Treatment of Pseudo-Jahn-Teller Systems. In Vibronic Interactions and the Jahn-Teller Effect: Theory and Application. (Prog. Theor. Chem. Phys. B 23); Atanasov, M., Daul, C., Tregenna-Piggott, P.L.W., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 59–82. ISBN 1567-7354. [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse, J. A.; Ware, M. J. Point group character tables and related data. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1972.

- Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D.G. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: Two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other function. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2008, 120, 215–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, G.W.; Trucks, M.J.; Schlegel, B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; Li, X.; et al. Gaussian 16, Revision B.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bauernschmitt, R.; Ahlrichs, R. Treatment of electronic excitations within the adiabatic approximation of time dependent density functional theory. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1996, 256, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalmani, G.; Frisch, M.J.; Mennucci, B.; Tomasi, J.; Cammi, R.; Barone, V. Geometries and properties of excited states in the gas phase and in solution: Theory and application of a time-dependent density functional theory polarizable continuum model. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 124, 94107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugliengo, P. MOLDRAW: A Program to Display and Manipulate Molecular and Crystal Structures, University Torino, Torino, 2012. Available online: https://www.moldraw.software.informer.com (accessed on 9 September 2019).

| Model | G | Γgr | EDFT [Hartree] | EJT [eV] | dOO [Å] | Γim | νim [cm-1] | K(G0, Γim) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G0 = C2v (Ia) | |||||||||||

| Ia | C2v a) | X1A1 | -1754.24175 | 0.000 | 2.253 | a2 | -169, -132, -26 | C2 | |||

| b1 | -51, -35 | Cs | |||||||||

| Ia | C2 b) | X1A | -1754.31051 | 1.871 | 2.515 | - | - | - | |||

| Ia | Cs c) | X1A’ | -1754.26014 | 0.500 | 2.363 | a” | -114, -86 | C1 | |||

| Ic | C1 d) | X1A | -1754.31780 | 2.069 | 2.547 | - | - | - | |||

| Ic | C1 b) | X1A | -1754.31525 | 2.000 | 2.534 | - | - | - | |||

| G0 = C2v(Ib) | |||||||||||

| Ib | C2v a) | X1A1 | -1754.19146 | 0.00 | 2.931 | a2 | -1469, -174, -147, -35 | C2 | |||

| b2 | -660 | Cs | |||||||||

| b1 | -653, -57, -53 | Cs | |||||||||

| Ib | C2 b) | X1A | -1754.31497 | 3.361 | 2.609 | - | - | - | |||

| Ib | Cs c) | X1A’ | -1754.24669 | 1.503 | 2.566 | a” | -530, -112, -106 | C1 | |||

| Ic | C1 b) | X1A | -1754.31525 | 3.368 | 2.534 | - | - | - | |||

| Ic | C1 d) | X1A | -1754.31780 | 3.438 | 2.547 | - | - | - | |||

| G0 = Cs(Ic) | |||||||||||

| Ic | Cs a) | X1A’ | -1754.25393 | 0.000 | 2.396 | a” | -169, -123, -52, -36, -26 | C1 | |||

| Ic | C1 d) | X1A | -1754.31780 | 1.738 | 2.547 | - | - | - | |||

| Ic | C1 b) | X1A | -1754.31525 | 1.669 | 2.534 | - | - | - | |||

| No. | Systems | Descent path |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ia, Ib | C2v C2 |

| 2 | Ia, Ib | C2v Cs C1 |

| 3 | Ib | C2v Cs C1 |

| 4 | Ic | Cs C1 |

| Model | G | Γgr | EDFT [Hartree] | EJT [eV] | dOC [Å] | Γim | νim [cm-1] | K(G0, Γim) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G0 = C2h(IIa) | |||||||||

| IIa | C2h a) | X1Ag | -1754.26464 | 0.000 | 2.423 | bg | -130, -19 | Ci | |

| au | -129, -39, -12 | C2 | |||||||

| IIa | Ci b) | X1Ag | -1754.31444 | 1.355 | 2.668 | - | - | - | |

| IIa | C2 c) | X1A | -1754.31670 | 1.417 | 2.677 | - | - | - | |

| G0 = C2h(IIb) | |||||||||

| IIb | C2h a) | X1Ag | -1754.24601 | 0.000 | 2.636 | bg | -380, -105, -15 | Ci | |

| au | -379, -103, -40, -20 | C2 | |||||||

| IIb | Ci b) | X1Ag | -1754.31792 | 1.957 | 2.745 | - | - | - | |

| IIb | C2 c) | X1A | -1754.31991 | 2.011 | 2.757 | - | - | - | |

| G0 = C2h(IIc) | |||||||||

| IIc | Cs a) | X1A’ | -1754.25521 | 0.000 | 2.419 2.641 |

a” | -393, -133, -107, -41, -20, -15 | C1 | |

| IIc | C1 b) | X1A | -1754.31619 | 1.659 | 2.744 2.666 |

- | - | - | |

| IIc | C1 c) | X1A | -1754.31834 | 1.718 | 2.753 2.677 |

- | - | - | |

| No. | Systems | Descent path |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | IIa, IIb | C2h Ci |

| 6 | IIa, IIb | C2h C2 |

| 7 | IIc | Cs C1 |

| Model | G | Γgr | EDFT [Hartree] | EJT [eV] | dOO [Å] | Γim | νim [cm-1] | K(G0, Γim) | ||

| G0 = D2h(IIIa) | ||||||||||

| IIIa | D2h a) | X1Ag | -1826.09765 | 0.000 | 2.262 | b2g | -127 | C2h | ||

| au | -126 | D2 | ||||||||

| b3u | -37 | C2v | ||||||||

| IIIa | C2h b) | X1Ag | -1826.13780 | 1.093 | 2.516 | - | - | - | ||

| IIIa | D2 d) | X1A | -1826.13963 | 1.142 | 2.526 | - | - | - | ||

| IIIa | C2v c) | X1A1 | -1826.10503 | 0.201 | 2.344 | b2 | -94 | Cs | ||

| a2 | -92 | C2 | ||||||||

| IIIc | C2 d) | X1A | -1826.15004 | 1.426 | 2.544 | - | - | - | ||

| IIId | C2 d) | X1A | -1826.14935 | 1.407 | 2.551 | - | - | - | ||

| IIIc | Cs b) | X1A’ | -1826.14682 | 1.338 | 2.539 | - | - | - | ||

| G0 = D2h(IIIb) | ||||||||||

| IIIb | D2h a) | X1Ag | -1825.99795 | 0.00 | 2.930 | b2g | -1466, -149 | C2h | ||

| au | -1466, -148, -35 | D2 | ||||||||

| b3g | -659 | C2h | ||||||||

| b1u | -657 | C2v | ||||||||

| b1g | -654, -54 | C2h | ||||||||

| b3u | -653, -53 | C2v | ||||||||

| IIIb | C2h b) | X1Ag | -1826.14666 | 4.047 | 2.610 | - | - | - | ||

| IIIb | D2 d) | X1A | -1826.14870 | 4.102 | 2.621 | - | - | - | ||

| IIIb | C2v c) | X1A1 | -1826.07720 | 2.157 | 2.552 | a2 | -531, -109 | C2 | ||

| b2 | -518, -109 | Cs | ||||||||

| IIIc | C2 d) | X1A | -1826.15004 | 4.139 | 2.544 | - | - | - | ||

| IIId | C2 d) | X1A | -1826.14935 | 4.120 | 2.551 | - | - | - | ||

| IIId | Cs b) | X1A’ | -1826.14682 | 4.051 | 2.539 | - | - | - | ||

| G0 = C2h(IIIc) | ||||||||||

| IIIc | C2h a) | X1Ag | -1826.12302 | 0.000 | 2.401 | bg | -118, | Ci | ||

| au | -117, -38 | C2 | ||||||||

| IIIc | Ci b) | X1Ag | -1826.14762 | 0.669 | 2.533 | - | - | - | ||

| IIIc | C2 d) | X1A | -1826.15004 | 0.735 | 2.544 | - | - | - | ||

| G0 = C2h(IIId) | ||||||||||

| IIId | C2v a) | X1A1 | -1826.12138 | 0.000 | 2.406 | b1 | -119, -38 | Cs | ||

| a2 | -118, -11 | C2 | ||||||||

| IIId | Cs b) | X1A’ | -1826.14682 | 0.692 | 2.539 | - | - | - | ||

| IIId | C2 d) | X1A | -1826.14935 | 0.761 | 2.551 | - | - | - | ||

| No. | Systems | Descent path |

| 8 | IIIa, IIIb | D2h C2h |

| 9 | IIIa, IIIb | D2h D2 |

| 10a | IIIa, IIIb | D2h C2v Cs |

| 10b | IIIa, IIIb | D2h C2v C2 |

| 11 | IIIb | D2h C2h |

| 12a | IIIb | D2h C2v Cs |

| 12b | IIIb | D2h C2v C2 |

| 13 | IIIb | D2h C2h |

| 14a | IIIb | D2h C2v Cs |

| 14b | IIIb | D2h C2v C2 |

| 15 | IIIc | C2h Ci |

| 16 | IIIc | C2h C2 |

| 17 | IIId | C2v Cs |

| 18 | IIId | C2v C2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).