Introduction

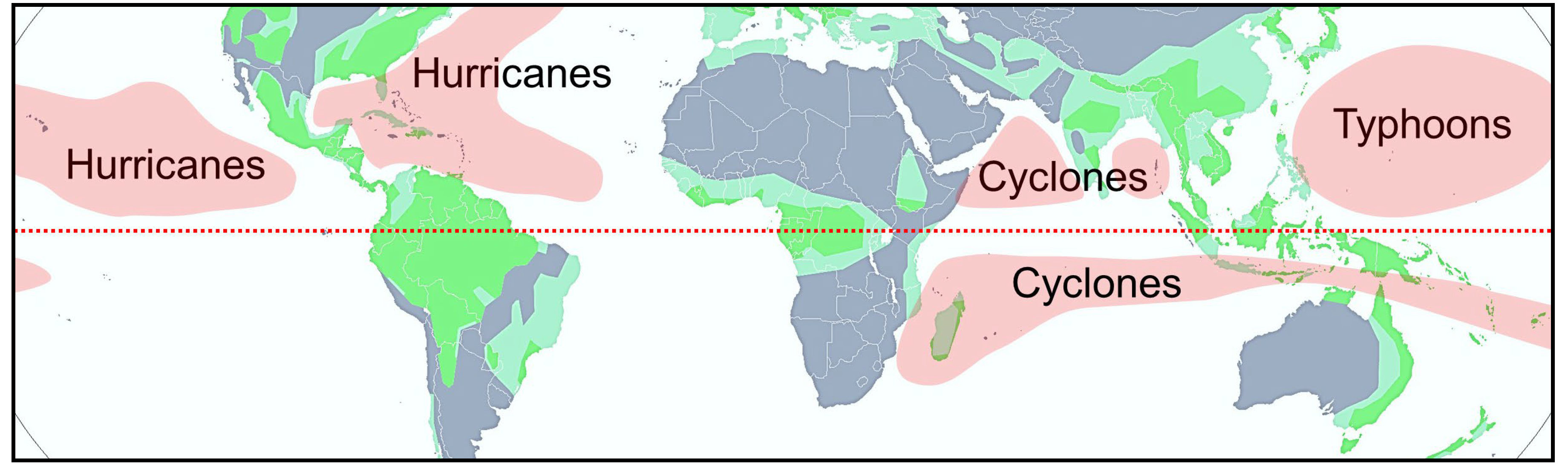

Tropical cyclones, also known as “hurricanes” or “typhoons” depending on where they occur (

Figure 1), are powerful weather systems characterized by a low-pressure “eye” surrounded by a vortex of rainbands and strong winds. The winds, rainfall, and flooding associated with these storms (henceforth “cyclones”) threaten lives, livelihoods, and infrastructure in many regions [

1,

2]. The poor tend to suffer disproportionately from the impacts [

3]. Recent investigations indicate that the frequency, power, and range of cyclones are increasing [

2,

4,

5,

6,

7].

The risk to life caused by tropical cyclones is poorly documented and often underestimated. A recent study examined 501 historical storms that hit the contiguous United States and considered long term impacts: it concluded that each tropical cyclone that makes landfall leads to an estimated 7,000–11,000 excess deaths (not just the 24 deaths average that occur immediately). According to the authors this makes cyclones a greater cause of excess mortality than motor accidents, infectious disease or military activity [

8].

While ecologists have long studied how forests respond to cyclones and other destructive events [

9,

10,

11], less attention has been given to how these events respond to forests. Such relationships are potentially important given the extent of global forest loss and proposed restoration efforts. Here, focusing on atmospheric and meteorological aspects, we examine the relationship between forest cover and the formation, frequency and violence of cyclones. Our hypothesis is that more (versus less) forest cover will reduce (increase) the formation, frequency and violence of cyclones. Science advances by identifying and testing valuable hypotheses so our main goal here is to explore if the hypothesis makes sense. Understanding these interactions could inform land-use planning in vulnerable regions, enhance disaster preparedness strategies, and add to ecosystem valuations. It might guide climate adaptation, disaster risk reduction, and sustainable development. Insights can inform global environmental policies and agreements, forest management and development. By synthesizing current understanding we hope to stimulate further investigation.

Context

Cyclones form over warm tropical seas. As moist air rises, it creates a low-pressure zone that draws in surrounding low-altitude air. This air converges, rises and cools—with most of the vapour it contains condensing or freezing—before the remaining drier air flows away at higher altitudes. Some of the dry air falls back into the eye and into bands while some rest spirals out and descends again some kilometres away. Intense water condensation around the eye of the cyclone creates dense clouds and heavy rain. Cyclones form in 5 to 30 degrees latitude bands either side of the equator. The characteristic vortex shape arises as a result of the Earth’s rotation (the “Coriolis force”) with counterclockwise storms forming in the northern hemisphere and clockwise in the south [

12,

13,

14].

While the conditions that lead to storms arising are relatively well known—for example, they only form where sea surface temperatures exceed 26.5°C—the specific processes remain a subject of research and debate [

15,

16,

17]. Cyclone formation takes days requiring suitable conditions to be sustained. While low pressure weather systems develop in many contexts, few become powerful cyclones. For example, over land, rough terrain slows and dissipates winds so that even if the surface is warm and moist, energy is lost faster than it is gained.

Mainstream understanding of cyclone development and functioning is summarized in models which likens a developing cyclone to a heat engine converting thermal energy from the ocean into kinetic energy that drives winds [

18,

19]. This model emphasizes the role of temperature differences, and the heat released from water vapor condensation in fuelling storms. While the subject of various adjustments and debates this model remains central to current theory [

18]. Storm formation, intensification and track prediction remain major research themes [

16].

This essay reflects recent technical insights and debates concerning the processes sustaining cyclones and also forests. Both cyclones and forests generate rainfall by drawing in large volumes of moist air. An appreciation of these processes offers insight into both how cyclones can generate two cubic kilometres of rain water per day [

20] and how tropical forests maintain high rainfall far from the ocean [

21]. Recent work suggests that moisture condensation plays a more central in these key processes than previously recognised [

22,

23]. While these ideas have been sketched out previously

1 they have not been the focus of a peer reviewed summary.

In brief, Makarieva and colleagues claim is that condensation of water vapour provides energy that generates and sustains the low pressure that that draws moisture into cyclones. In contrast to past theory that considers cyclones to be largely driven by ocean heat with moisture playing a minor role, Makarieva and colleagues argue that the energy provided to cyclones from water vapour is around five times that from ocean heat [

24]. Similarly, water vapour condensation is the dominant factor in driving the winds that draw moisture deep into forest rich continents [

25,

26]. This mechanism also suggests forests and cyclones compete for atmospheric moisture. Forests draw this moisture—that might otherwise spawn, or support the growth of, cyclones—away from the oceans. Of course, various other mechanisms and processes also influence outcomes. These relationships too require evaluation.

How Forests Influence Cyclones

Forests likely have various effects on cyclone creation and behaviours. We summarise what we know by considering temperature, surface friction, moisture (condensation) and aerosols.

Temperature

Cyclones need heat. Cyclones become more frequent and more powerful as temperatures rise. Forests influence temperatures through various mechanisms. Additional carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is believed to contribute to warming at the global scale [

27] with this heating being seen as the major reason that storms are believed to be becoming more frequent and covering a wider range of latitudes [

2,

5,

7]. Forests sequester large amounts of carbon from the atmosphere [

28], so, all else being equal, more forests means less carbon dioxide and a cooler climate while less forests means a warmer climate. Forests also influence air temperature more locally through effects on, radiation, moisture and heat flows [

29,

30]. Various details, such as the influence on clouds and thus on temperature, remain under active research. While the overall influence of boreal forest has been a subject of debate (being much darker than the snow for much of the year they can lead to local warming in the winter months) tropical forests have an overall cooling effect both locally and globally [

31,

32]. Such an overall colling effect from forests should dampen heat-dependent cyclone formation and growth.

Land surfaces and Friction

The destructive potential of cyclones depends on the speed of the winds and where they strike [

33]. Numerous studies have explored the factors influencing such outcomes and the role of land-cover [

34]. Friction is the best understood. The friction between air and land surface dissipates wind energy and thus slows cyclones and impedes their development. This is one reason why most cyclones form far from land (despite the heat and moisture over some land surfaces) and weaken as they near land (often over a few hours) [

35,

36,

37]. Compared to other land cover forests are particularly effective wind breaks [

38]. This is due to their high “aerodynamic roughness length”” a physical measure which estimates this friction and relates to the height, profile, and density of surface features including trees [

39]. Few storms that make landfall survive more than a few days.

Moisture Condensation

Evaporation leads to local cooling as energy is used to evaporate water rather than cause heating. Nearly half of all the sun’s energy reaching the Earth’s surface goes into vaporising water. Much of this vaporising is due to plants, in particular trees [

40,

41]. This is because trees can sustain high levels of transpiration when other land cover cannot [

42]. In areas with less vegetation where less moisture is returned to the atmosphere, more of the sun’s energy goes into heat [

30,

41]. These effects have both local and global contributions to heating and cooling, though there is uncertainty around the influence of these moisture and temperature processes regarding cloud dynamics and atmospheric flows.

As water vapour condenses it releases heat (“latent heat”) which can warm the local atmosphere and drive atmospheric motion via increased buoyancy. This energy contributes to the dynamics of cyclonic storms. This heat release adds to the heat gained directly from the warm ocean and is thus part of the models currently used to understand cyclone dynamics [

18,

19]. The winds that develop with cyclones bolster evaporation from the ocean by an order of magnitude and thus further bolster the energy of the storm [

12,

43].

Heat release isn’t the only contribution made by water vapour as it condenses: the reduction in gas molecules as vapor becomes liquid or solid also contributes. There is evidence that this process adds to storm power [

44]. Recent theoretical work on this effect suggests that as water vapor evaporates and condenses, changes in the number of gas molecules can also generate atmospheric pressure gradients that contribute to both cyclone dynamics and to global wind patterns [

24,

45]. The power generated is potentially large. Under this theoretical reappraisal the total energy provided to cyclones from water vapour is around five times that from ocean heat [

24]. This explains why the energy generated by a cyclone matches the water vapor condensing within it [

20,

45] –

Figure 2. The implication is that we can actually predict cyclone power from their rainfall.

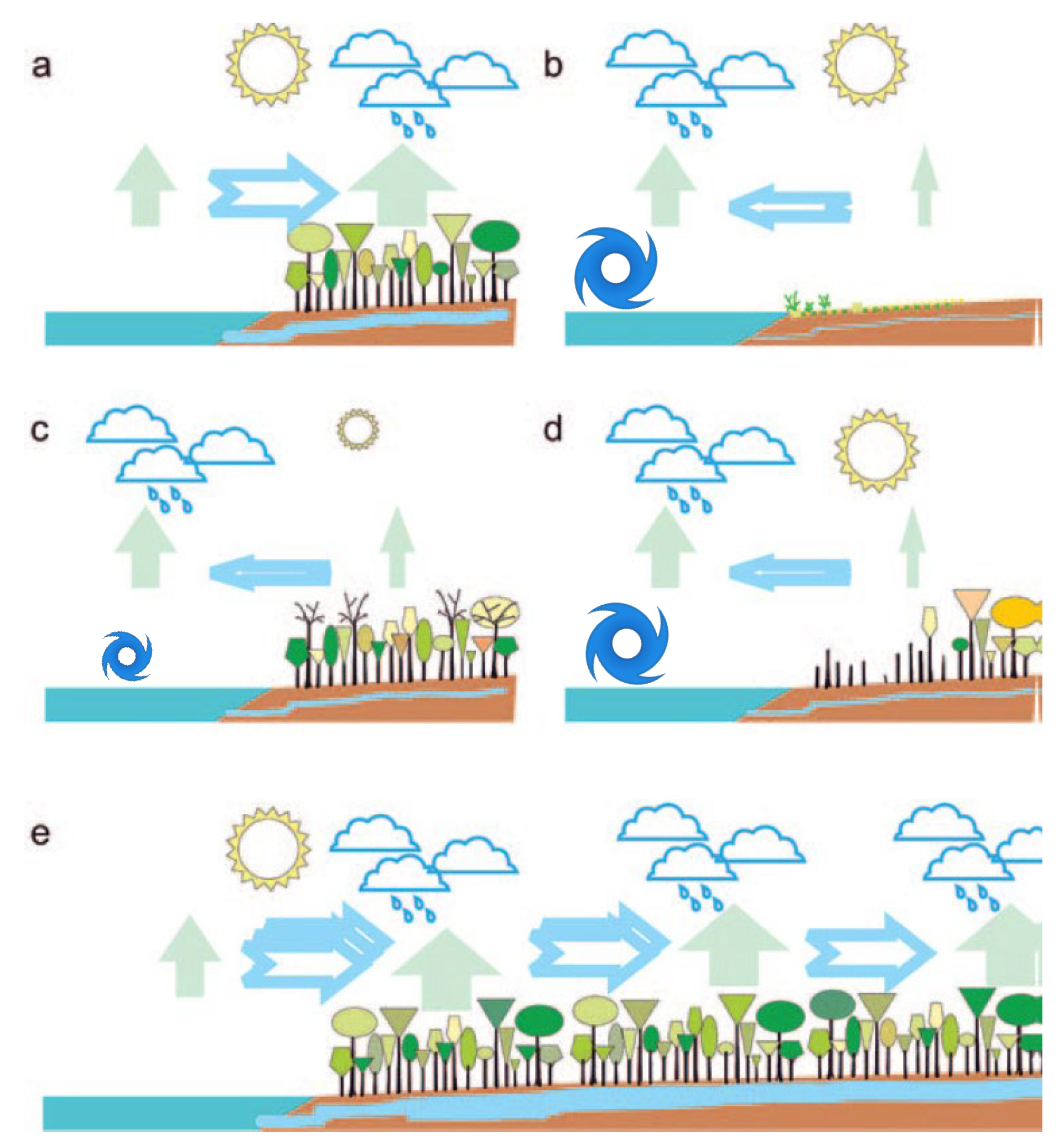

Similar to the discussion around the role of water vapour in fuelling cyclones there have been parallel developments around the role of water vapour (and forests as a major source of water vapour over land) in driving the winds that carry rainfall into continents. Theory and observations suggest that forests create persistent areas of low pressure that draw in moist warm low-lying air from surrounding regions and feeding rainfall inland [

22,

25,

46,

47]. This process is often referred to as the “Biotic Pump”. While still often portrayed as controversial e.g., [

48], these ideas have gained recognition over recent years and supporting evidence appears to be accumulating [

42,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53]. I wont attempt a full theoretical discussion here, but the key point is that the physical mechanisms that sustain the biotic pump are basically the same as those that drive cyclones—the condensation of water vapour leads to a reduction in air pressure that was not accounted for in previous models. The implication if the biotic pump means that forests play a major role in generating the low pressure areas that draw in atmospheric moisture from surrounding regions (

Figure 3). If this moisture is drawn in to provide rain over continents it is not accumulating over the ocean. The ability of forest to draw warm moist air in from the oceans results in a circulation in which the air over the tropical oceans is cooler and drier [

26]. With cooler drier air over the oceans cyclones are less likely to form or gain power. Nonetheless, as cyclones are generally believed to move with the ambient circulation they are embedded within [

54] there is a potential concern if forest related landward winds draw storms to landfall—whether a stronger draw increases the overall threat or perhaps reduces it, by not giving storms time to grow remains a matter of speculation.

There have been suggestions that forests themselves could act as sources of warm moist air that might generate and support cyclones [

55]. Evidence contradicts these speculations—no such processes have been observed. While forests indeed release large amounts of moisture back to the atmosphere providing a potential energy source, the frictional forces and diurnal temperature variations over these landscapes appear sufficient to prevent cyclone development. Similarly, any existing cyclones that approach are slowed as they dissipate energy more rapidly than it can be replenished. There are occasionally storms that, rather then slowing, actually gain energy as they approach land. These are generally small and associated with unusually clear skies which permits sunlight to heat the shallow near-shore seas—such continued heating is unlikely in large storm where clouds are typically widespread [

56]. There are also cases where heat and moisture from the land surface appear to sustain cyclones as they reach land. Such effects have been reported where tree cover is sparse and moist heat is available, e.g., a wet desert [

57].

Aerosols

Aerosols—particles and droplets suspended in the air—play a major role in atmospheric processes. Potential interactions between aerosols and cyclones are multifaceted and uncertain with few direct observations to guide us. Various interactions are believed to influence cloud development and how heat moves within the atmosphere and are likely to play some role [

58,

59] though much remains uncertain [

60].

A key influence of aerosols is in determining the conditions under which water vapour condenses to liquid water or freezes to ice (ice nucleation). These processes are heavily influenced by aerosol properties, including size, composition, and concentration [

61,

62,

63]. I will not attempt a comprehensive review here as the topic is technical and remains a field of active research, but in general some particles are much better at contributing to condensation and freezing than others (allowing these to occur at lower humidity levels and high temperatures) and many of the more potent aerosols have a biological origin associated with forest I provide a more complete introduction with various examples in [

52].

Forests are significant sources and sinks of various aerosols. They emit “primary biological aerosol particles” (PBAPs) such as pollen, spores, and bacteria, as well as “volatile organic compounds” (VOCs). The volatile compounds undergo various reactions in the atmosphere and interact with each other and with the particles to form diverse “secondary organic aerosols” (SOAs) some of which may, depending on conditions, persist for only seconds or minutes, while other persist for days [

52,

64,

65]. These forest-derived aerosols can influence cloud formation and precipitation [

65,

66].

Ice formation plays a major role in cloud dynamics and related meteorological phenomena [

67,

68]. There is evidence that particles can influence this process. These particles facilitate the freezing of water at warmer temperatures than would otherwise be required, impacting cloud formation and precipitation [

69]. Such particles include not only salts, ash and mineral dust but also various biological materials—and various studies indicate that the biological particles are not only diverse but often the most abundant and influential [

70,

71]. Forests, and indeed other vegetation, appear to emit many such particles to the atmosphere though their wider implications are uncertain [

52].

Aerosols that promote condensation and/or freezing likely affect storm dynamics in various ways as they influence the conditions under which water vapor becomes ice or water and thus determine where the energy from these processes is released and what ice and water is being carried (Thompson & Eidhammer, 2014; Zhang et al., 2024). Simulations suggest that cyclone behaviour will be sensitive to many of these aerosol determined atmospheric processes though the details debated, with some recent work suggesting contradictory effects [

72]. The impacts may vary with particle properties, concentrations, and context. Some research has suggested that aerosols might suppress intensification in the early stages of cyclone formation [

58].

For the purpose of our discussion we note that atmospheric moisture is a key energy source for cyclones and thus any factors influencing this moisture, and its distribution in time and space, will also affect the distribution of energy available to create and sustain storms. Aerosols that reduce the moisture holding capacity of the air also reduce the energy that is subsequently available. Noting that forests are often a major source of such aerosols and that some of these are likely to promote condensation in the often relatively aerosol free air that moves in from over the ocean, suggests that forest may reduce the potential energy available (i.e., condensation happens at lower water vapour concentrations). As saturated air moves from lower aerosol concentrations, where condensation is inhibited, to higher aerosol concentrations (over and near forests) where condensation is promoted and this energy release is likely to lower air pressure and reduce the ability of stable weather systems to develop in nearby oceans (as these will be drawn towards the forest). Research to clarify these relationships is lacking.

Any relationship between forests and aerosols is further complicated by spatial and temporal variability in forest cover. Deforestation, forest fires, and land-use changes can significantly modify aerosol composition and concentrations over time and space, potentially influencing atmospheric processes at local, regional, and even global scales [

73,

74]. For example, deforestation can lead to increased dust emissions, while forest fires produce large quantities of black carbon and other aerosols that can have wide-ranging atmospheric effects.

The potential effect of aerosols (from forests and otherwise) on cyclones is not limited to direct interactions as aerosols may influence larger-scale atmospheric circulation and climate which in turn can affect the frequency and intensity of cyclones over longer time scales [

60,

75].

Synthesis and Conclusions

Assessing the overall impact of forest gain and loss on cyclones requires somehow balancing multiple uncertain relationships and influences. Some of the uncertainties involve theory while many simulations that have been used to propose relationships remain of unknown validity in practice. Giver current knowledge, forests appear likely to be able to inhibit cyclone formation by mitigating key requirements: heat, moisture, and especially low friction. The positive contribution of heat and the negative role of friction are not contested. While the specific mechanisms remain contested there is no disagreement about water vapour having a generally positive role in contributing to cyclones. The dominant role of heat, moisture and friction, means that the hypothesis that, despite various uncertainties, more (versus less) forest cover will reduce (increase) the formation, frequency and violence of cyclones appears plausible and justifies further evaluation.

The role of moisture could explain the scarcity of cyclones in the South Atlantic despite warm ocean conditions—atmospheric moisture is regularly drawn to the forests of the Amazon and Congo. Forests near to what would otherwise be expected to be potential cyclone formation areas— the low pressure over the nearby forests divert the necessary moisture away. Observations confirm that long lived patches of high moisture are generally scarce in this region though more formal assessments should be possible to quantify these differences (see

http://tropic.ssec.wisc.edu/real-time/mtpw2/about.html).

Relationships regarding landfall are less clear. Forests’ low-pressure systems might attract storms, potentially increasing the likelihood and frequency of landfall while also reducing time for storms to grow before this happens. These local effects could also influence affected coastlines, latitudes, and inland storm tracks. Aerosols introduce additional complexity, potentially intensifying energy use in some areas while limiting available energy in others and overall. The interplay of these factors underscores the need for further research to fully understand forest-cyclone interactions.

We have focused on the hypothesis that the presence and extent of forests will influence the atmospheric processes that determine cyclone formation and power. The key underlying idea is that increased forest cover reduces the threat from such storms. But there are, of course, many other good arguments for conserving and restoring tropical forests—these include the maintenance of the water cycle [

52,

76], the sequestration of carbon [

28], and the preservation of habitat for biodiversity [

77] as well as many other goods and services—[

78,

79,

80,

81]. Some of these arguments will be relevant if and when a cyclone strikes. There is for example, evidence to show that mangrove forests reduce the harm due to cyclones that hit coastal communities [

82,

83]. Furthermore, communities with access to forest have additional options and may cope better and recover more quickly from destructive storms and floods than communities without such access [

84,

85].

The potential for forests to influence tropical cyclones is evident, but the nature and extent of such relationships remain unclear. There are good reasons to suggest that forest conservation and expansion may reduce cyclone frequency and severity when compared to a world with less forests. In a world grappling with climate change, biodiversity decline and poverty, this warrants attention.

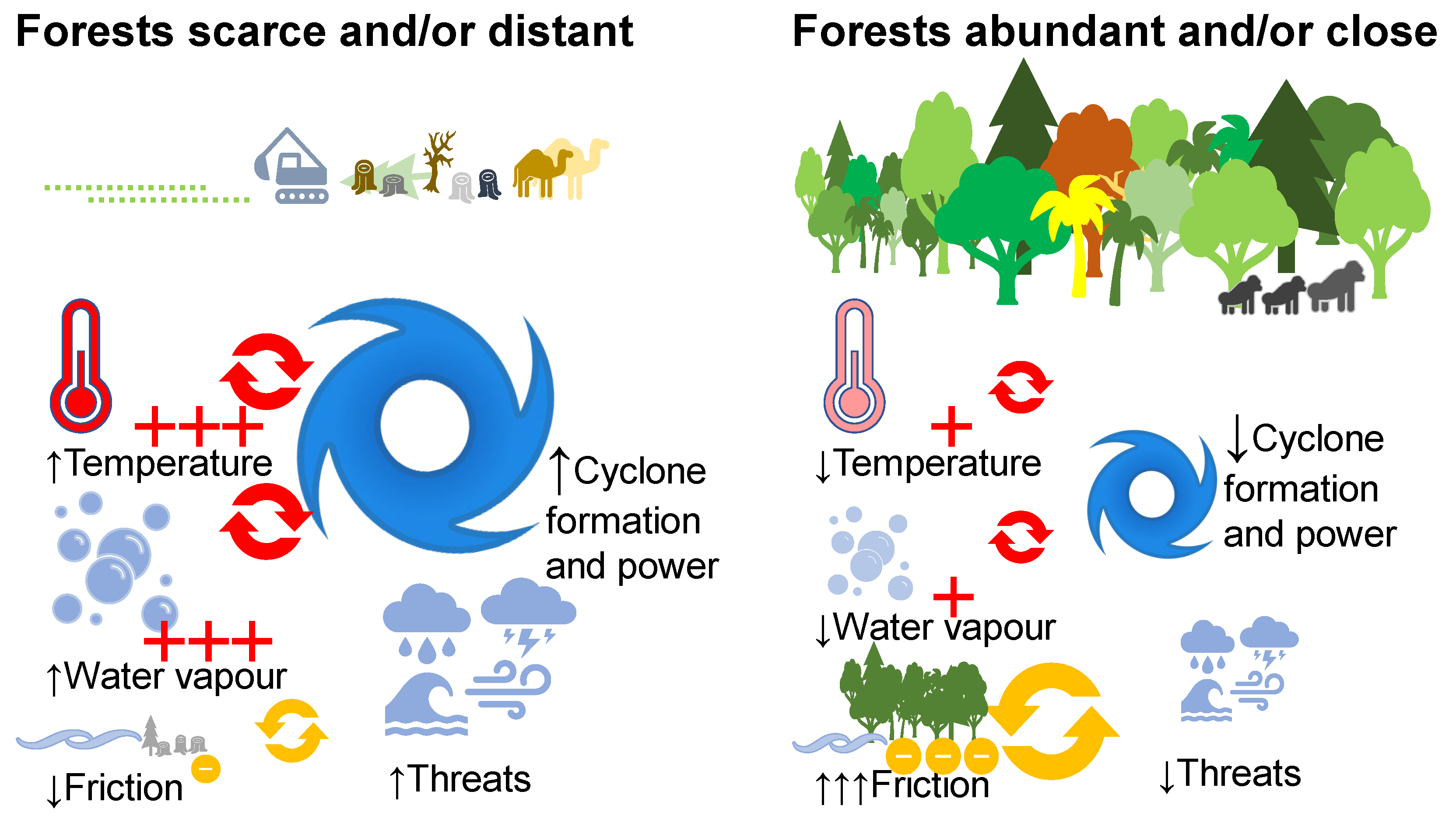

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of the formation and power gain of tropical cyclones in a context without extensive forest and with (and near to) extensive forests. Red + signs show sources of energy (heat and vapour) that available to cyclones while yellow – show losses of energy (friction). We omit aerosols as though they likely play a role their contribution is uncertain. The magnitude of the relationships remains speculative though we are confident about the sign (plus or minus): i.e., while friction plays a negative role in cyclone development, heat and moisture play positive roles.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of the formation and power gain of tropical cyclones in a context without extensive forest and with (and near to) extensive forests. Red + signs show sources of energy (heat and vapour) that available to cyclones while yellow – show losses of energy (friction). We omit aerosols as though they likely play a role their contribution is uncertain. The magnitude of the relationships remains speculative though we are confident about the sign (plus or minus): i.e., while friction plays a negative role in cyclone development, heat and moisture play positive roles.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the many colleagues who have helped inform and develop these ideas.With this draft I have had specific comments and suggestions from Dr Anastassia Makarieva, Professor Kevin Trenberth, Professor Gary Lackmann and Professor Kerry Emmanuel. This text remains a draft and corrections and suggestions are welcome.

References

- Jing, R. et al. Global population profile of tropical cyclone exposure from 2002 to 2019. Nature 626, 549-554. [CrossRef]

- Emanuel, K. Response of global tropical cyclone activity to increasing CO 2: Results from downscaling CMIP6 models. Journal of Climate 34, 57-70 (2021).

- Hallegatte, S., Vogt-Schilb, A., Rozenberg, J., Bangalore, M. & Beaudet, C. From Poverty to Disaster and Back: a Review of the Literature. Economics of Disasters and Climate Change 4, 223-247. [CrossRef]

- Kossin, J. P., Knapp, K. R., Olander, T. L. & Velden, C. S. Global increase in major tropical cyclone exceedance probability over the past four decades. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117, 11975-11980. [CrossRef]

- Li, L. & Chakraborty, P. Slower decay of landfalling hurricanes in a warming world. Nature 587, 230-234, doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2867-7 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. & Toumi, R. Recent migration of tropical cyclones toward coasts. Science 371, 514-517 (2021).

- Wang, S. & Toumi, R. More tropical cyclones are striking coasts with major intensities at landfall. Scientific reports 12, 5236 (2022).

- Young, R. & Hsiang, S. Mortality caused by tropical cyclones in the United States. Nature. [CrossRef]

- Sheil, D. & Burslem, D. F. Disturbing hypotheses in tropical forests. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 18, 18-26 (2003).

- Lin, T.-C., Hogan, J. A. & Chang, C.-T. Tropical cyclone ecology: A scale-link perspective. Trends in ecology & evolution 35, 594-604 (2020).

- Thonis, A., Stansfield, A. & Akçakaya, H. R. Unravelling the role of tropical cyclones in shaping present species distributions. Global Change Biology 30, e17232. [CrossRef]

- Trenberth, K. E. Warmer oceans, stronger hurricanes. Scientific American 297, 44-51 (2007).

- Emanuel, K. Tropical cyclones. Annual review of earth and planetary sciences 31, 75-104 (2003).

- Emanuel, K. Divine wind: the history and science of hurricanes. (Oxford university press, 2005).

- Tang, B. H. et al. Recent advances in research on tropical cyclogenesis. Tropical Cyclone Research and Review 9, 87-105 (2020).

- Emanuel, K. Tropical Cyclone Seeds, Transition Probabilities, and Genesis. Journal of Climate 35, 3557-3566. [CrossRef]

- Rajasree, V. et al. Tropical cyclogenesis: Controlling factors and physical mechanisms. Tropical Cyclone Research and Review (2023).

- Emanuel, K. 100 years of progress in tropical cyclone research. Meteorological Monographs 59, 15.11-15.68 (2018).

- Emanuel, K. A. An air-sea interaction theory for tropical cyclones. Part I: Steady-state maintenance. Journal of Atmospheric Sciences 43, 585-605 (1986).

- Sabuwala, T., Gioia, G. & Chakraborty, P. Effect of rainpower on hurricane intensity. Geophysical Research Letters 42, 3024-3029. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J. B. et al. The land–atmosphere water flux in the tropics. Global Change Biology 15, 2694-2714 (2009).

- Makarieva, A. M. & Gorshkov, V. G. The biotic pump: Condensation, atmospheric dynamics and climate. International Journal of Water 5, 365-385 (2010).

- Makarieva, A. M. & Gorshkov, V. G. Energetics of locomotion in animate and inanimate nature. Energy: Economics, Technology, Ecology 6, 46-52 (2013).

- Makarieva, A. M. et al. Fuel for cyclones: The water vapor budget of a hurricane as dependent on its movement. Atmospheric research 193, 216-230 (2017).

- Makarieva, A., Gorshkov, V., Sheil, D., Nobre, A. & Li, B.-L. Where do winds come from? A new theory on how water vapor condensation influences atmospheric pressure and dynamics. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 13, 1039-1056 (2013).

- Makarieva, A. M., Gorshkov, V. G. & Li, B.-L. Revisiting forest impact on atmospheric water vapor transport and precipitation. Theoretical and Applied Climatology 111, 79-96 (2013).

- Canadell, J. G. et al. in Climate change 2021: The physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change 673-816 (Cambridge University Press, 2023).

- Mo, L. et al. Integrated global assessment of the natural forest carbon potential. Nature 624, 92-101, doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06723-z (2023). [CrossRef]

- Ellison, D. et al. Trees, forests and water: Cool insights for a hot world. Global Environmental Change 43, 51-61, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2017.01.002 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Ellison, D., Pokorný, J. & Wild, M. Even cooler insights: On the power of forests to (water the Earth and) cool the planet. Global change biology 30, e17195 (2024).

- Jia, G. et al. in Special Report on Climate Change and Land: An IPCC Special Report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems 133-206 (IPCC, 2019).

- Lawrence, D., Coe, M., Walker, W., Verchot, L. & Vandecar, K. The unseen effects of deforestation: biophysical effects on climate. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change 5, 756115 (2022).

- Colette, A., Leith, N., Daniel, V., Bellone, E. & Nolan, D. S. Using Mesoscale Simulations to Train Statistical Models of Tropical Cyclone Intensity over Land. Monthly Weather Review 138, 2058-2073. [CrossRef]

- Wadler, J. B. et al. A review of recent research progress on the effect of external influences on tropical cyclone intensity change. Tropical Cyclone Research and Review 12, 200-215. [CrossRef]

- Weinkle, J., Maue, R. & Pielke Jr, R. Historical global tropical cyclone landfalls. Journal of Climate 25, 4729-4735 (2012).

- Hlywiak, J. & Nolan, D. S. The Response of the Near-Surface Tropical Cyclone Wind Field to Inland Surface Roughness Length and Soil Moisture Content during and after Landfall. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 78, 983-1000. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. & Chavas, D. R. The transient responses of an axisymmetric tropical cyclone to instantaneous surface roughening and drying. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 77, 2807-2834 (2020).

- Saha, K. K. & Wasimi, S. A. Statistical modelling of tropical cyclones’ longevity after landfall in Australia. Australian Meteorological and Oceanographic Journal 65, 376-386.

- Lettau, H. Note on aerodynamic roughness-parameter estimation on the basis of roughness-element description. Journal of Applied Meteorology (1962-1982) 8, 828-832 (1969).

- Jasechko, S. et al. Terrestrial water fluxes dominated by transpiration. Nature 496, 347-350 (2013).

- Schlesinger, W. H. & Jasechko, S. Transpiration in the global water cycle. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 189, 115-117 (2014).

- Sheil, D. How plants water our planet: advances and imperatives. Trends in Plant Science 19, 209-211 (2014).

- Trenberth, K. E., Davis, C. A. & Fasullo, J. Water and energy budgets of hurricanes: Case studies of Ivan and Katrina. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 112. [CrossRef]

- Lackmann, G. M. & Yablonsky, R. M. The Importance of the Precipitation Mass Sink in Tropical Cyclones and Other Heavily Precipitating Systems. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 61, 1674-1692.

- Makarieva, A. M., Gorshkov, V. G. & Nefiodov, A. V. Empirical evidence for the condensational theory of hurricanes. Physics Letters A 379, 2396-2398. [CrossRef]

- Makarieva, A. M. & Gorshkov, V. G. Biotic pump of atmospheric moisture as driver of the hydrological cycle on land. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 11, 1013-1033 (2007).

- Sheil, D. & Murdiyarso, D. How forests attract rain: an examination of a new hypothesis. Bioscience 59, 341-347 (2009).

- Pearce, F. Weather makers. Science 368, 1302-1305, doi:doi:10.1126/science.368.6497.1302 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Makarieva, A. M. et al. Why does air passage over forest yield more rain? Examining the coupling between rainfall, pressure, and atmospheric moisture content. Journal of Hydrometeorology 15, 411-426 (2014).

- Makarieva, A. M. et al. The role of ecosystem transpiration in creating alternate moisture regimes by influencing atmospheric moisture convergence. Global Change Biology 29, 2536–2556. [CrossRef]

- Baudena, M., Tuinenburg, O. A., Ferdinand, P. A. & Staal, A. Effects of land-use change in the Amazon on precipitation are likely underestimated. Global Change Biology 27, 5580-5587 (2021).

- Sheil, D. Forests, atmospheric water and an uncertain future: the new biology of the global water cycle. Forest Ecosystems 5, 1-22 (2018).

- Webb, T. J., Woodward, F. I., Hannah, L. & Gaston, K. J. Forest cover–rainfall relationships in a biodiversity hotspot: the Atlantic forest of Brazil. Ecological Applications 15, 1968-1983 (2005).

- Kossin, J. P. A global slowdown of tropical-cyclone translation speed. Nature 558, 104-107. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, T. & Shepherd, M. in Hurricanes and Climate Change: Volume 3 (eds Jennifer M. Collins & Kevin Walsh) 117-134 (Springer International Publishing, 2017.

- Lok, C. C. F., Chan, J. C. L. & Toumi, R. Tropical cyclones near landfall can induce their own intensification through feedbacks on radiative forcing. Communications Earth & Environment 2, 184. [CrossRef]

- Emanuel, K., Callaghan, J. & Otto, P. A hypothesis for the redevelopment of warm-core cyclones over northern Australia. Monthly Weather Review 136, 3863-3872 (2008).

- Rosenfeld, D., Khain, A., Lynn, B. & Woodley, W. Simulation of hurricane response to suppression of warm rain by sub-micron aerosols. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 7, 3411-3424 (2007).

- Fan, J., Zhang, R., Li, G. & Tao, W. K. Effects of aerosols and relative humidity on cumulus clouds. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 112 (2007).

- Stier, P. et al. Multifaceted aerosol effects on precipitation. Nature Geoscience 17, 719-732. [CrossRef]

- Carslaw, K. et al. A review of natural aerosol interactions and feedbacks within the Earth system. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 10, 1701-1737 (2010).

- Kreidenweis, S. M., Petters, M. & Lohmann, U. 100 years of progress in cloud physics, aerosols, and aerosol chemistry research. Meteorological Monographs 59, 11.11-11.72 (2019).

- Tao, W. K., Chen, J. P., Li, Z., Wang, C. & Zhang, C. Impact of aerosols on convective clouds and precipitation. Reviews of Geophysics 50 (2012).

- Spracklen, D. V. et al. Contribution of particle formation to global cloud condensation nuclei concentrations. Geophysical Research Letters 35 (2008).

- Artaxo, P. et al. Tropical and boreal forest–atmosphere interactions: a review. Tellus, Series B-Chemical and Physical Meteorology 24, 24-163 (2022).

- Després, V. et al. Primary biological aerosol particles in the atmosphere: a review. Tellus B: Chemical and Physical Meteorology 64, 15598 (2012).

- Phillips, V. T., Yano, J.-I. & Khain, A. Ice multiplication by breakup in ice–ice collisions. Part i: Theoretical formulation. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 74, 1705-1719 (2017).

- Sullivan, S. C., Hoose, C., Kiselev, A., Leisner, T. & Nenes, A. Initiation of secondary ice production in clouds. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics Discussions 2017, 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Hoose, C. & Möhler, O. Heterogeneous ice nucleation on atmospheric aerosols: a review of results from laboratory experiments. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 12, 9817-9854. [CrossRef]

- Testa, B. et al. Ice Nucleating Particle Connections to Regional Argentinian Land Surface Emissions and Weather During the Cloud, Aerosol, and Complex Terrain Interactions Experiment. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 126, e2021JD035186, doi:https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JD035186 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Failor, K. C., Schmale, D. G., III, Vinatzer, B. A. & Monteil, C. L. Ice nucleation active bacteria in precipitation are genetically diverse and nucleate ice by employing different mechanisms. The ISME Journal 11, 2740-2753. [CrossRef]

- Akinyoola, J. A., Oluleye, A. & Gbode, I. E. A Review of Atmospheric Aerosol Impacts on Regional Extreme Weather and Climate Events. Aerosol Science and Engineering. [CrossRef]

- Ginoux, P., Prospero, J. M., Gill, T. E., Hsu, N. C. & Zhao, M. Global-scale attribution of anthropogenic and natural dust sources and their emission rates based on MODIS Deep Blue aerosol products. Reviews of Geophysics 50 (2012).

- Sokolik, I., Soja, A., DeMott, P. & Winker, D. Progress and challenges in quantifying wildfire smoke emissions, their properties, transport, and atmospheric impacts. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 124, 13005-13025 (2019).

- Booth, B. B. B., Dunstone, N. J., Halloran, P. R., Andrews, T. & Bellouin, N. Aerosols implicated as a prime driver of twentieth-century North Atlantic climate variability. Nature 484, 228-232. [CrossRef]

- Smith, C., Baker, J. C. A. & Spracklen, D. V. Tropical deforestation causes large reductions in observed precipitation. Nature, doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05690-1 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Sayer, J. et al. in Sustainable development goals: their impacts on forest and people 482-509 (Cambridge University Press, 2019).

- Katila, P.; et al. Sustainable Development Goals: their Impacts on Forests and People. (Cambridge University Press, 2019).

- Taye, F. A. et al. The economic values of global forest ecosystem services: A meta-analysis. Ecological Economics 189, 107145 (2021).

- Nambiar, E. S. Tamm Review: Re-imagining forestry and wood business: pathways to rural development, poverty alleviation and climate change mitigation in the tropics. Forest Ecology and Management 448, 160-173 (2019).

- Ghazoul, J. & Sheil, D. Tropical Rain Forest Ecology, Diversity & Conservation. (Oxford University Press, 2010).

- Das, S. & Vincent, J. R. Mangroves protected villages and reduced death toll during Indian super cyclone. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106, 7357-7360 (2009).

- Hochard, J. P., Hamilton, S. & Barbier, E. B. Mangroves shelter coastal economic activity from cyclones. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116, 12232-12237 (2019).

- Liswanti, N., Sheil, D., Basuki, I., Padmanaba, M. & Mulcahy, G. Falling back on forests: how forest-dwelling people cope with catastrophe in a changing landscape. International Forestry Review 13, 442-455 (2011).

- Wunder, S., Börner, J., Shively, G. & Wyman, M. Safety nets, gap filling and forests: a global-comparative perspective. World development 64, S29-S42 (2014).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).