Submitted:

25 October 2024

Posted:

28 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

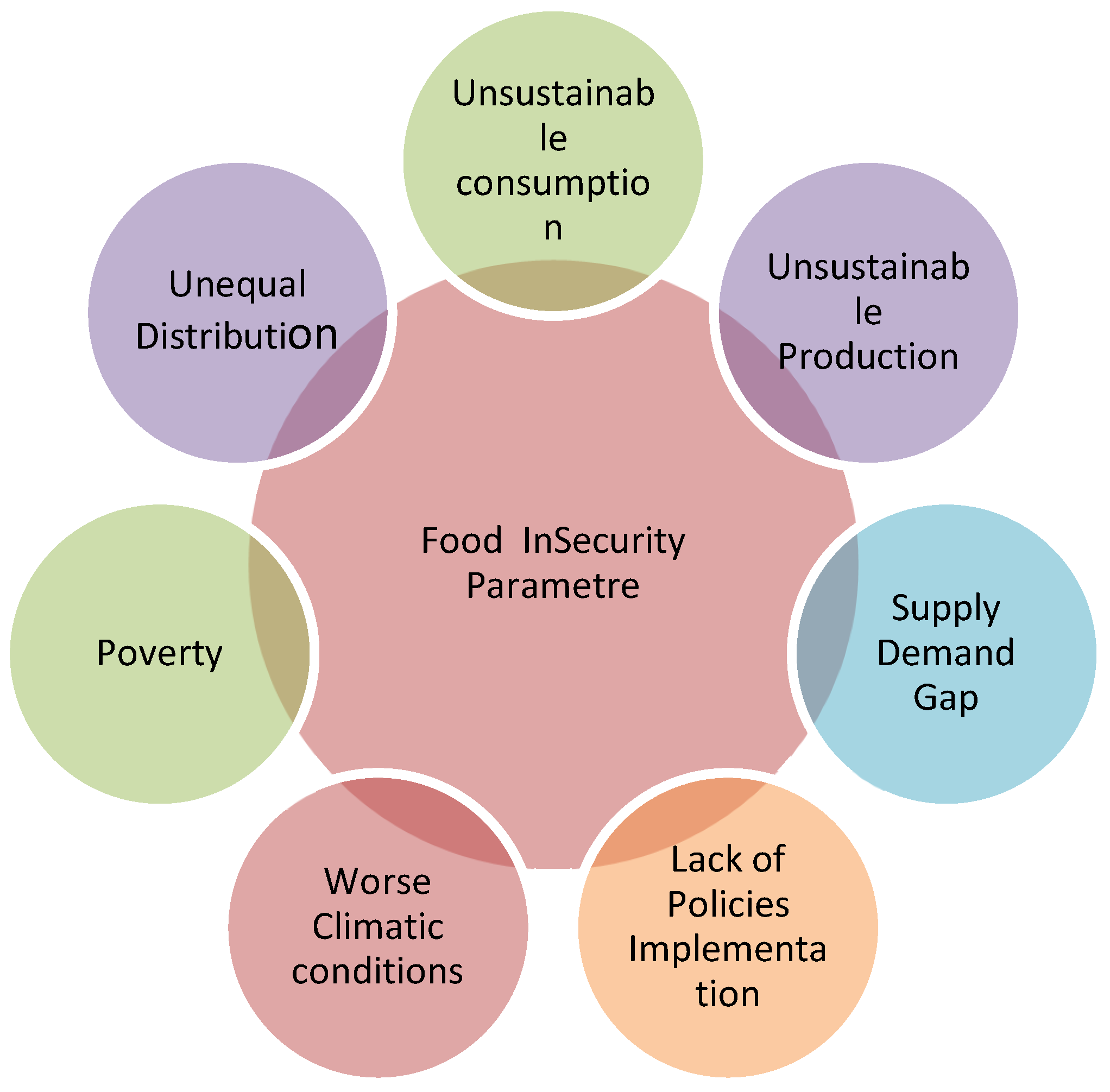

This paper examines the current state of food security in Pakistan, focusing on the factors influencing the nation's ability to ensure a stable food supply. The analysis covers food production, distribution, accessibility, and stability, while also considering socioeconomic and environmental factors. The role of government regulations and international collaborations is explored in addressing food security challenges. Despite the critical importance of agricultural governance for sustainable food production and economic development, Pakistan's agricultural sector remains under prioritized, suffering from a lack of strategic vision and inconsistent government support. This neglect undermines efforts to achieve food security and stability. The study evaluates the alignment of Pakistan's National Food Security Policy (2018) with global, national, and provincial standards for sustainable agricultural management. A framework based on principles, criteria, and indicators (PCI) was developed, utilizing both quantitative and qualitative methodologies. Forty-three indicators, eleven criteria, and one guiding principle across four dimensions were identified. Thirteen governance tools were assessed using a ratio scale (0–5), with results presented in a policy coherence matrix. The coherence index score of 2.14 indicates significant misalignment among regulatory instruments, highlighting gaps in addressing climate change, low-income food access, service management, and institutional capacity. The study reveals that many food policies in Pakistan are outdated and inconsistent, requiring revision to address local challenges and align with emerging international obligations. The findings provide a comprehensive overview of the current food security landscape in Pakistan, offering insights for more informed decision-making to build a resilient and sustainable food system.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Food Security in Pakistan: A Situational Analysis

| Crops | Production (2018–2022) | Production (22–23) | Production (23–24) | %age Change (23–24) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat | 25,707 | 26,400 | 28,000 | 9 |

| Rice | 7530 | 5500 | 9000 | 20 |

| Cotton | 5640 | 3900 | 6700 | 19 |

| Barely | 48 | 42 | 55 | 14 |

| Sunflower seeds | 121 | 148 | 135 | 12 |

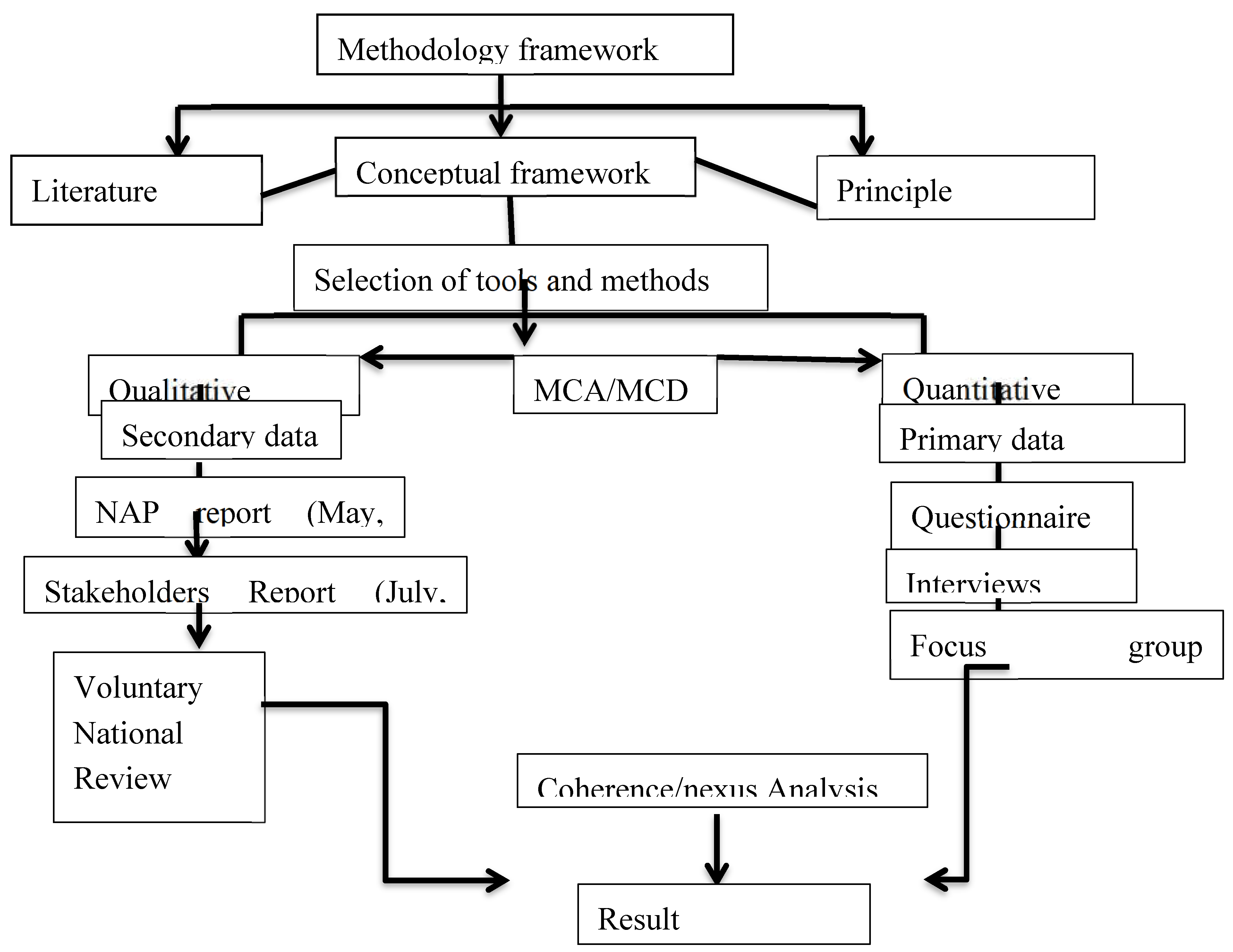

2. Methodological Framework

2.1. Study Approach

2.2. Methodological Approach

2.3. Development of PCI Based Framework

2.4. PCI Framework Coding System

- (1)

- The coherence principle is denoted by the alphanumeric designation PC-N, where “PC” signifies the Principle of Coherence, and “N” represents the number of dimensions assigned to the principle, spanning from 1 to 4.

- (2)

- Criteria selected against the Principle of Coherence with dimension one (PC-1A) are categorized as CN-EN ͤ. In this designation, C represents criteria, N denotes the serial number of the criterion, E signifies the PC-1A criteria category, and N ͤ indicates the serial number within the PC-1A criteria category.

- (3)

- Criteria selected against the Principle of Coherence with dimension 2 (PC-1B) are designated as CN-SNs. In this coding system, C represents criteria, N denotes the criterion’s serial number, S signifies the PC-1B criteria category, and Ns indicate the serial number associated with the PC-1B criteria category.

- (4)

- Criteria selected against the Principle of Coherence with dimension 3 (PC-1C) are documented as CN-GNg, where C denotes criteria, N represents the serial number of the criterion, G stands for the PC-1B criteria category, and Ng signifies the serial number within the PC-1C criteria category

- (5)

- Criteria selected against the Principle of Coherence with dimension 4 (PC-1D) are documented as CN-PSs, where C denotes criteria, N represents the serial number of the criterion, P stands for the PC-1D criteria category, and Ss’ signifies the serial number within the PC-1D criteria category

- (6)

- Indicators corresponding to criteria selected against the Principle of Coherence, dimension 1 (PC-1) are designated as CN- EN ͤY. Here, C represents criteria, N denotes the serial number of the criterion, E signifies the PC-1 criteria category, Ne stands for the serial number within the PC-1A criteria category, and Y represents the indicator’s serial number.

2.5. PC-1A’s Parameters, Indicators, and Scope

2.6. Criterion 1 of PC-1A: Physical Availability of Food: (C1-E1, C2-E2 & C3-E3)

| Code | Indicators (Environmental) | Scope-Wise Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| C1-E1.1 | Measures exist to improve arable land for cultivation of food | Improving soil quality, prime agricultural lands. |

| C1. E1.2 | Measures exist to improve agricultural yields sustainably | Better irrigation, hybrid varieties, resistant varieties, farm input. |

| C1. E1.3 | Measures to assess climate vulnerability and adaptation exist to improve food availability in extreme events | Research &development, funds, stakeholders& IPPPs. |

| C1. E1.4 | Measures to mitigate climate risk to food crops | imports, storage, food distribution |

| C1. E1.5 | Measures to incentivize farmers for food crop diversification | subsidies, improved seeds quality |

| Code | Indicators (Social) | Scope-Wise Keywords |

| C2. E2.6 | Measures to control food supply and demand imbalances due to demographic factors. | Food Stamp, Food Safety Net, income Support, Minimum Wage Programs. |

| C2. E2.7 | Measures to ensure equitable distribution of food among provinces | Sustainable transport, disaster risk measures. |

| C2. E2.8 | Measures exist to ensure availability of food for people living below poverty line | Emergency response Mechanisms. |

| C2. E2.9 | Measures exist to meet essential nutrition requirement for pregnant women and infants | Caloric provisions, incentives. |

| C2. E2.10 | Measures to control factors that imbalance food supply and demand e.g., immigration, urbanization | Consumption and production ratio, equal distribution, water availability. |

| Code | Indicators (Economic) | Scope-wise Keywords |

| C3. E3.11 | Investment in agriculture sector | Stakeholders, IPPPs, incentives. |

| C3. E3.12 | Identifying and fulfilling the needs of the small land holders to improve crop productivity | subsidies, incentives, markup free loans |

| C3. E3.13 | Measures to reduce expenditure on food imports | improved agricultural practices, machineries, on farm water management |

| C3. E3.14 | Provision of economic subsidies, incentives, technological access to farmers | improved agricultural products |

2.7. Criterion 2 of PC-1B: Economic and Physical Access to Food: (C4-S1 & C5-S2).Seven Indicators were Formulated Based on PC-1B and Two Specified Criteria for the Analysis, as Defined Within the Study’s Scope

| Code | Indicators (Physical Access) | Scope-Wise Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| C4-S1.1 | Mechanisms to provide and improve access to food markets | storage facilities, improved transportation structure, fuel prices, economical safe |

| C4. S1.2 | Mechanism is in place to ensure access to food in vulnerable situations e.g., famine, floods, droughts | Disaster management. |

| C4. S1.3 | Governance and institutional framework exist to cater seasonal variation in food diversity | climate change adaptations and mitigation measures |

| C4. S1.4 | Measures to promote subsistence farming, kitchen gardening, livestock keeping | climate resilient adaptations |

| Code | Indicators (Economic Access) | Scope-Wise Keywords |

| C5. S2.5 | Measures to improve per capita GDP (Purchasing Power) | Affordability of nutritious diet. |

| C5. S2.6 | Measures to control food inflation (cost of food)/food price index | policies, export import ratio, crop production within the border |

| C5. S2.7 | Measures to improve minimum wage/reduce proportion of people below poverty line | Policies, laws, subsidies, incentives. |

2.8. Criterion 3 of PC-1C: Food Utilization: (C6-G1 &C7-G2).Nine Indicators were Formulated Based on PC-1C and Two Specified Criteria for the Analysis, as Defined Within the Study’s Scope

| Code | Indicators (Provision of services) | Scope-Wise Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| C6-G1.1 | Provision for safe drinking water and sanitation facilities | Improved health conditions. |

| C6. G1.2 | Measures to control wasting, stunting and obesity in young children and adults | Policies, eco-labeling, eco-friendly, nutritious. |

| C6. G1.3 | Measures to improve maternal health and birth weight | policies, free follow-ups, provision of healthy food, minerals, vitamins |

| C6. G1.4 | measures to control Anemia among women of reproductive ages | Health policies, free nutritional food provision. |

| C6. G1.5 | Measures to promote exclusive breastfeeding among infants | Awareness programs, campaigns, health care of mothers. |

| Code | Indicators (Socio-cultural choices)) | Scope-Wise Keywords |

| C7-G2.6 | Measures to address lack of awareness regarding nutritional needs | awareness programs, campaigns |

| C7-G2.7 | Measures to improve cooking and food habits | appropriate nutritional food |

| C7-G2.8 | Diversification in food choices by consumers for example dairy consumption | caloric provisions, incentives |

| C7-G2.9 | Promoting indigenous food items instead of importing | improved production, variety of crops |

2.9. Criterion 4 of PC-1D: Stability: (C8-P1, C9-P2, C10-P3 & C11-P4)

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Broad-Spectrum of the Research

3.2. Results and Findings

- (1)

- The Pure Food Ordinance, 1960: The 1960 Pure Food Ordinance revises and consolidates regulations related to the production and sale of food. With minor adjustments, all provinces and specific northern territories have endorsed this legislation. Its primary goal is to safeguard the purity of market-sold food by preventing adulteration. Individuals are legally prohibited from mixing, coloring, staining, or powdering food in violation of approved regulations or if they anticipate that such actions may compromise the healthiness of the food (Ashraf et al., 2023).

- (2)

- Pakistan Pure Food Laws (PFL), 1963: The existing legal framework for food quality and safety in the country is structured around the PFL. Additionally, it incorporates milk and its derivatives. These regulations specifically cover aspects such as heavy metals, antioxidants, synthetic colors, preservatives, and raw food additives (Drew & Crase, 2023).

- (3)

- The Cantonment Pure Food Act, 1966: The Pure Food Act of 1960 and the Cantonment Pure Food Act of 1966 exhibit minimal distinctions between them, with closely aligned operational guidelines.

- (4)

- Pakistan Hotels and Restaurant Act, 1976: The Pakistan Hotels and Restaurants Act of 1976 oversee all hotels and dining establishments in the country, aiming to manage and enforce standards for service and pricing. Section 22(2) of the act prohibits the sale of contaminated food or beverages that were not prepared in a hygienic manner or served with dirty or unclean utensils.

- (5)

- The Pakistan Standards and Quality Control Authority (PSQCA) Act, 1996: This legislation prioritizes the maintenance of testing laboratories’ standards by aligning practices and equipment with updated regulations and technological progress. It also involves conducting training sessions for the public and stakeholders, monitoring the production lines of diverse food products, and ensuring compliance with industry hygiene standards (PFA, 2018) (Farrukh et al., 2022).

- (6)

- Punjab Food Pure Regulations, 2018: Deals with food quality, equal distribution pattern, no preservatives, additives should be added, packaging and food storage facilities should not be compromised.

- (7)

- Pakistan Food Security Policy, 2018: To ensure a state-of-the-art and efficient food production and distribution system that, in terms of availability, accessibility, utilization, and stability, can most effectively bolster food security and nutrition (Khalid Bashir, 2017).

3.3. Overall Coherence Index of FSA

| Criteria Code | Criteria | Coherence Index | Level of Coherence |

|---|---|---|---|

| C1-E1 | Environmental (C1-E1) | 2.20 | Partial |

| C2-E2 | Social (C2-E2) | 2.49 | Partial |

| C3-E3 | Economic (C3-E3) | 1.89 | Limited or Poor |

| Total Average | 2.19 | Partial | |

3.3.1. Principle Dimension (PC-1B)

| Criteria Code | Criteria | Coherence Index | Level of Coherence |

|---|---|---|---|

| C4-S1 | Physical Access (C4-S1) | 2.65 | Partial |

| C5-S2 | Economic Access (C5-S2) | 1.11 | Poor or limited |

| Total Average | 1.88 | Poor or limited | |

3.3.2. Principle Dimension (PC-1C)

| Criteria Code | Criteria | Coherence Index | Level of Coherence |

|---|---|---|---|

| (C6-G1) | Socio-cultural choices (C6-G1) | 2.56 | Partial |

| (C7-G2) | Provision of services (C7-G2) | 2.05 | Partial |

| Total Average | 2.30 | Partial | |

3.3.3. Principle Dimension (PC-1D)

| Criteria Code | Criteria | Coherence Index | Level of Coherence |

|---|---|---|---|

| (C8-P1) | Policies & Governance(C8-P1) | 2.04 | Partial |

| (C9-P2) | Institutional(C9-P2) | 2.25 | Partial |

| (C10-P3) | Coherence & Coordination(C10-P3) | 2.38 | Partial |

| (C11-P4) |

Implementation & Monitoring (C11-P4) |

2.32 | Partial |

| Total Average | 2.24 | Partial | |

3.4. Index of Coherence Based on Criteria

4. Conclusions

5. Recommendations

References

- Aamir Shahzad, M., Wang, L., Qin, S., & Zhou, S. (2023). COVID-19 incidence of poverty: How has disease affected the cost of purchasing food in Pakistan. Preventive Medicine Reports, 36, 102477. [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, Zhou.,D., Shah, T., Ali, S., Ahmad, W., Din, I. U., & Ilyas, A. (2019). Factors affecting household food security in rural northern hinterland of Pakistan. Journal of the Saudi Society of Agricultural Sciences, 18(2), 201–210. [CrossRef]

- Abidi, S. M. A. (2023). The Urgent Need to Address Child Malnutrition in Rural Areas of Pakistan: Lessons from the 2022 Floods. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 37(5), e11–e12. [CrossRef]

- Alfieri, F., López-Padilla, A., & Julio-Gonzalez, L. C. (2023). 1.15—Politics, Economics and Demographics of Food Sustainability and Security. In P. Ferranti (Ed.), Sustainable Food Science—A Comprehensive Approach (pp. 157–168). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Allouche, J. (2011). The sustainability and resilience of global water and food systems: Political analysis of the interplay between security, resource scarcity, political systems and global trade. Food Policy, 36, S3–S8. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, W., Rehman, A., Rabbani, M., Shaukat, W., & Wang, J.-S. (2023). Aflatoxins posing threat to food safety and security in Pakistan: Call for a one health approach. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 180, 114006. [CrossRef]

- Aslam, B., Muhammad, K., Iqbal, J., Akhtar, N., Mottaeva, A. B., Fedorovna, T. T., Barykin, S., & Khan, M. I. (2023). Coherence Analysis of National Maritime Policy of Pakistan across Shipping Sector Governance Framework in the Context of Sustainability.

- Azeem, M. M., Mugera, A. W., & Schilizzi, S. (2016). Living on the edge: Household vulnerability to food-insecurity in the Punjab, Pakistan. Food Policy, 64, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Aziz, N., Ren, Y., Rong, K., & Zhou, J. (2021). Women’s empowerment in agriculture and household food insecurity: Evidence from Azad Jammu & Kashmir (AJK), Pakistan. Land Use Policy, 102, 105249. [CrossRef]

- Babu, S. C., & Gajanan, S. N. (2022). Chapter 2—Implications of technological change, postharvest technology, and technology adoption for improved food security—application of t-statistic. In S. C. Babu & S. N. Gajanan (Eds.), Food Security, Poverty and Nutrition Policy Analysis (Third Edition) (Third Edition, pp. 27–66). Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Bahar, N. H. A., Lo, M., Sanjaya, M., Van Vianen, J., Alexander, P., Ickowitz, A., & Sunderland, T. (2020). Meeting the food security challenge for nine billion people in 2050: What impact on forests? Global Environmental Change, 62, 102056. [CrossRef]

- Bahn, R. A., Hwalla, N., & El Labban, S. (2021). Chapter 1—Leveraging nutrition for food security: the integration of nutrition in the four pillars of food security. In C. M. Galanakis (Ed.), Food Security and Nutrition (pp. 1–32). Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Britwum, K., & Demont, M. (2022). Food security and the cultural heritage missing link. Global Food Security, 35, 100660. [CrossRef]

- Datta, P., Behera, B., & Rahut, D. B. (2024). Assessing the role of agriculture-forestry-livestock nexus in improving farmers’ food security in South Asia: A systematic literature review. Agricultural Systems, 213, 103807. [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L., Grande, M., Borondo, F., & Borondo, J. (2023). Anticipating food price crises by reservoir computing. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 174, 113854. [CrossRef]

- Drew, M., & Crase, L. (2023). ‘More Crop per Drop’ and water use efficiency in the National Water Policy of Pakistan. Agricultural Water Management, 288, 108491. [CrossRef]

- Economics, S.-A. R. and P. I. of D. (2021). SDG 12 MONITORING AND REPORTING IN PAKISTAN An Analysis of National Action Plan on SCP and.

- Fanzo, J., & Miachon, L. (2023). Harnessing the connectivity of climate change, food systems and diets: Taking action to improve human and planetary health. Anthropocene, 42, 100381. [CrossRef]

- Farrukh, M. U., Bashir, M. K., Rola-Rubzen, M. F., & Ahmad, A. (2022). Dynamic effects of urbanization, governance, and worker’s remittance on multidimensional food security: An application of a broad-spectrum approach. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 84, 101400. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A., Rayeen, F., Mishra, R., Tripathi, M., & Pathak, N. (2023). Nanotechnology applications in sustainable agriculture: An emerging eco-friendly approach. Plant Nano Biology, 4, 100033. [CrossRef]

- Hao, L., Wang, P., Yu, J., & Ruan, H. (2022). An integrative analytical framework of water-energy-food security for sustainable development at the country scale: A case study of five Central Asian countries. Journal of Hydrology, 607, 127530. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, H. F., Rizk, Y., Chalak, A., Abiad, M. G., & Mattar, L. (2023). Household food waste generation during COVID-19 pandemic and unprecedented economic crisis: The case of Lebanon. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 14, 100749. [CrossRef]

- Howard, J. A. (2022). Chapter One—Facing up to our converging climate and food system catastrophes (M. J. Cohen (ed.); Vol. 7, pp. 1–34). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A., & Routray, J. (2012). Status and factors of food security in Pakistan. International Journal of Development Issues, 11, 164–185. [CrossRef]

- James, R., Lyons, K., McKay, P., Konia, R., Lionata, H., & Butt, N. (2023). When solutions to the climate and biodiversity crises ignore gender, they harm society and the planet. Biological Conservation, 287, 110308. [CrossRef]

- Kalair, A. R., Abas, N., Ul Hasan, Q., Kalair, E., Kalair, A., & Khan, N. (2019). Water, energy and food nexus of Indus Water Treaty: Water governance. Water-Energy Nexus, 2(1), 10–24. [CrossRef]

- Khalid Bashir, M. (2017). Food Security Policies in Pakistan. In Reference Module in Food Science. Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A., & Singh, M. P. (2023). A journey of social sustainability in organization during MDG & SDG period: A bibliometric analysis. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 88, 101668. [CrossRef]

- Liobikienė, G., Matiiuk, Y., & Krikštolaitis, R. (2023). The concern about main crises such as the Covid-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and climate change’s impact on energy-saving behavior. Energy Policy, 180, 113678. [CrossRef]

- Moallemi, E. A., Eker, S., Gao, L., Hadjikakou, M., Liu, Q., Kwakkel, J., Reed, P. M., Obersteiner, M., Guo, Z., & Bryan, B. A. (2022). Early systems change necessary for catalyzing long-term sustainability in a post-2030 agenda. One Earth, 5(7), 792–811. [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, M. A., Mabhaudhi, T., & Massawe, F. (2021). Building a resilient and sustainable food system in a changing world—A case for climate-smart and nutrient dense crops. Global Food Security, 28, 100477. [CrossRef]

- Ngo, J., Ortiz-Andrellucchi, A., & Serra-Majem, L. (2016). Malnutrition: Concept, Classification and Magnitude. In B. Caballero, P. M. Finglas, & F. Toldrá (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Food and Health (pp. 610–630). Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Odey, G., Adelodun, B., Lee, S., Adeyemi, K. A., & Choi, K. S. (2023). Assessing the impact of food trade centric on land, water, and food security in South Korea. Journal of Environmental Management, 332, 117319. [CrossRef]

- Polman, D. F., Selten, M. P. H., Motovska, N., Berkhout, E. D., Bergevoet, R. H. M., & Candel, J. J. L. (2023). A risk governance approach to mitigating food system risks in a crisis: Insights from the COVID-19 pandemic in five low- and middle-income countries. Global Food Security, 39, 100717. [CrossRef]

- Posel, D., & Casale, D. (2021). Moving during times of crisis: Migration, living arrangements and COVID-19 in South Africa. Scientific African, 13, e00926. [CrossRef]

- Rafique, M. M., & Rehman, S. (2017). National energy scenario of Pakistan—Current status, future alternatives, and institutional infrastructure: An overview. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 69(November 2016), 156–167. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. A., Afridi, S., Hossain, M. B., Rana, M., Al Masum, A., Rahman, M. M., & Al-Maruf, A. (2024). Nexus between heat wave, food security and human health (HFH): Developing a framework for livelihood resilience in Bangladesh. Environmental Challenges, 14, 100802. [CrossRef]

- Rizwanullah, M., Yang, A., Nasrullah, M., Zhou, X., & Rahim, A. (2023). Resilience in maize production for food security: Evaluating the role of climate-related abiotic stress in Pakistan. Heliyon, 9(11), e22140. [CrossRef]

- Sakschewski, B., von Bloh, W., Huber, V., Müller, C., & Bondeau, A. (2014). Feeding 10 billion people under climate change: How large is the production gap of current agricultural systems? Ecological Modelling, 288, 103–111. [CrossRef]

- Shah, H. J., & Khan, A. (2023). Globalization and nation states—Challenges and opportunities for Pakistan. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 8(1), 100621. [CrossRef]

- Stany, V., Judical, B., & Nachigera Mushagalusa, G. (2021). Determinants of Food Insecurity According to the Calorie Intake Approach: A Specific Case in South Kivu, DRC. International Journal of Applied Agricultural Sciences, Vol. 7, 190–202. [CrossRef]

- Tambo, E., Zhang, C.-S., Tazemda, G. B., Fankep, B., Tappa, N. T., Bkamko, C. F. B., Tsague, L. M., Tchemembe, D., Ngazoue, E. F., Korie, K. K., Djobet, M. P. N., Olalubi, O. A., & Njajou, O. N. (2023). Triple-crises-induced food insecurity: Systematic understanding and resilience building approaches in Africa. Science in One Health, 2, 100044. [CrossRef]

- Tortajada, C., & González-Gómez, F. (2022). Agricultural trade: Impacts on food security, groundwater and energy use. Current Opinion in Environmental Science & Health, 27, 100354. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, H., & Badshah, L. (2023). Nutritional and mineral analysis of the ultimate wild food plants of Lotkuh, Chitral, the Eastern Hindukush Pakistan. Heliyon, 9(3), e14449. [CrossRef]

- Uyanga, V. A., Bello, S. F., Bosco, N. J., Jimoh, S. O., Mbadianya, I. J., Kanu, U. C., Okoye, C. O., Afriyie, E., Mak-Mensah, E., Agyenim-Boateng, K. G., Ogunyemi, S. O., Nkoh, J. N., Olasupo, I. O., Karikari, B., & Ahiakpa, J. K. (2024). Status of agriculture and food security in post-COVID-19 Africa: Impacts and lessons learned. Food and Humanity, 2, 100206. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y., & Begho, T. (2022). Towards responsible production, consumption and food security in China: A review of the role of novel alternatives to meat protein. Future Foods, 6, 100186. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).