Literature Review

University technology transfer is a psycho-sociological phenomenon with economic implications. The effective study of this phenomenon requires a multidisciplinary approach applying knowledge from several disciplines. However, a review of the technology transfer literature reveals a heavy emphasis on economics-based theory that is often applied in a manner that attributes material reality to abstract analytic concepts.

Researchers have used various frameworks and approaches to examine the underlying determinants of success in university technology transfer. Bozeman (2000) noted that technology transfer studies at the time were heavily focused on evaluation research. While the focus of evaluation research is determining what outcomes a policy or program produces, theory development is often a by-product. Evaluation studies supported the development of theories to explain technology transfer as a phenomenon because evaluation research typically requires empirical analysis (Bozeman). However, evaluation research has an inherent counterweight that limits its usefulness as a means of advancing technology transfer theory. As Bozeman observed, evaluation research usually focuses on the interests of the institutions sponsoring the research, which can push aside theoretical considerations.

The three major theories used to explain university technology transfer are transaction cost economic theory, the resource-based view, and the knowledge-based view (Anatan, 2015). Transaction cost economics conceptualizes the firm as a governance structure, which is an organizational construct (Williamson, 1998). However, the theory reifies the constructs of organization and governance structure. The objective of governance is to impose order on potential conflicts that could undermine opportunities to realize gain (Williamson). Such conflicts pose the danger of raising transaction costs and deteriorating the profitability of opportunities. Transaction cost economics assumes that profit maximization is the motivation and goal of private sector commercial firms (Williamson). The literature demonstrates that this assumption is problematic (Cyert & March, 1963). University technology transfer can and does occur in the absence of a profit motive. Transaction cost economics generally can be applied to any question about organizations that can be reformulated as a contracting problem (Williamson).

In many respects, technology transfer is a contracting exercise. However, transaction costs economics essentially answers the question of why economic institutions are structured as they are and not otherwise (Williamson, 1998). As such, it can be applied to understand why demand side organizations choose to obtain technology from universities rather than create it internally or why university technology transfer functions are organized as they are. From a broader perspective, firms and markets are alternative modes of governance (Williamson). Transaction cost economics can help understanding why and under what circumstances a private sector organization will rely on internal activity rather than markets to fulfill a technological need or assimilate a given technology once it has been acquired. However, the theory does not explain everything about behavior attributed to organizations (Williamson).

The resource-based view (RBV) is a managerial framework that aims to explain how profit-seeking commercial enterprises (firms) achieve sustainable competitive advantage. Barney (1991) is often cited as the foundational work for the resource-based view. RBV answers questions about what kind of strategies firms pursue. It asserts that firms derive sustained competitive advantage from internal resources that are valuable, rare, imperfectly imitable, and non-substitutable (Barney). However, RBV does not explain why private sector organizations pursue, obtain, and assimilate a technology that was created at a university, which is an external resource. Furthermore, universities are not driven by the need for competitive advantage to the same degree as private sector firms. Therefore, RBV seems lacking as a framework for explaining why universities pursue particular strategies to transfer technologies to the private sector.

The knowledge-based view of the firm is considered a recent extension of the resource-based view and aims to explain differences in the performance of firms (Curado & Bontis, 2006). It is also particularly applicable to learning within organizations and the role of intellectual capital (Curado & Bontis). Knowledge (in the lay meaning of the term) is a resource that can provide sustained competitive advantage because it is difficult to imitate and often takes a tacit form that is difficult to articulate and document (Anatan, 2015; Curado & Bontis). However, like the resource-based view, the knowledge-based view is concerned with knowledge as an internal resource of an organization and does not explain why an organization acts to obtain and assimilate external knowledge. Like RBV, the knowledge-based view also seems insufficient to explain why universities organize technology transfer functions as they do and pursue particular strategies to effectuate the transfer of technologies to the private sector because it makes certain assumptions about competitive advantage that are not necessarily relevant to universities.

Resource dependence theory (RDT) also aims to explain behavior attributed to organizations at the macro level. According to Nienhüser (2008), the questions to which RDT can successfully be applied should roughly correspond to that of transaction cost economics theory. RDT is an explanation of how managers of firms ensure the survival of their organizations (Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978). It is particularly useful in explaining how different organizational structures emerge (Nienhüser). A basic premise of RDT is that organization members have far less influence over organizational outcomes than the environment in which the organization operates (Hillman et al., 2009; Pfeffer & Salancik). RDT assumes that the primary motivation for organizational behavior is survival, which depends on the organization’s ability to control critical resources found in the environment (Hillman et al.; Nienhüser; Pfeffer & Salancik). This dependence on the environment is a primary source of uncertainty because the environment is not dependable in providing critical resources (Pfeffer & Salancik). Thus, members of an organization will act to reduce either dependence on uncertain environmental resources or any uncertainty associated with critical resources upon which the organization depends for survival. However, this framework does not adequately capture the nature of university technology transfer. A university’s or a private sector organization’s survival is not constantly in jeopardy. The degree to which an organization’s existence is in jeopardy waxes and wanes over time. Therefore, not all organizational behavior is driven by survival. Members of a private sector organization may decide to obtain and assimilate a technology created at university for reasons that are not directly related to the immediate survival of the organization. Likewise, university technology transfer functions may organize and pursue given strategies for reasons that are not driven by concerns for the immediate survival of the university or the technology transfer office.

Institutional theory has also been proposed as an alternative framework for explaining factors that affect university technology transfer. For example, Anatan (2015) argued that external environmental forces pressure organizations to form alliances to enable university-to-industry knowledge transfer. However, the way institutional theory is generally applied reifies the organization construct.

While all these theories have been successfully applied to the study of university technology transfer, they tend to reify the construct of organization. This imposes a limitation on their application and usefulness in examining university technology transfer. Additionally, in applying these various theories, studies of university technology transfer seem to have mostly focused on factors exogeneous to the technology and technology transfer process. Moreover, many university technology transfer studies employ multiple regression analysis which can only establish correlations but cannot make reliable claims regarding causation. This also has significant epistemological implications.

Analysis and Results

Most university technology transfer transactions occur in an organizational context. In testimony to a hearing held by the U.S. House of Representatives, the U.S. Department of Commerce Undersecretary for Technology at the time, Robert M. White, pointed out that technology transfer is fundamentally a business decision on the demand side of the process (Barriers to Domestic Technology Transfer, 1992, p. 142). The participants in university technology transfer are the universities on the supply side that create the technologies and organizations on the demand side, which seek to obtain and assimilate the technologies. These organizations can include both for-profit and non-profit organizations as well as aspiring entrepreneurs (i.e., individuals or small teams of a few people) who generally must create or sustain organizations to make use of the technology. The objective of these demand side participants is to successfully obtain and assimilate technologies to achieve various ends. Therefore, it is only prudent that scholars also examine technology transfer from the perspective of demand-side actors. However, the current theories and concepts that researchers employ are deficient to varying degrees and in different ways as applied to the study of university technology transfer.

Ontological and Epistemological Issues

There are several ontological and epistemological issues that impact how one examines the phenomenon of technology transfer. The discourse reveals two diametrically opposed schools of thought about the nature of organizations and the appropriate approach to studying macro level organizational phenomena (see Du Gay & Vikkelsø, 2017; Hatch, 1997, 2018; Miller & Fox, 2015).

The classical school of thought treats an organization as a concrete phenomenon. Formal organization is considered the appropriate focus of study (Du Gay & Vikkelsø, 2017). Research in this school of thought emanates from within the organization, is focused on pragmatic objectives, such as better coordination of task performance, and is unconcerned with creating a grand theory of organizing (Du Gay & Vikkelsø). The construct of organization is reified to the point that the human element is lost in the analysis. Scholars in this school of thought essentially take the position expressed by Milton Friedman who argued the goal of theory is not to accurately represent or reproduce phenomena (e.g., social or economic phenomena) but to develop propositions that can be analyzed and theory that has predictive power (Cyert & March, 1963). This seems a bit shortsighted and limiting.

Theory that does not accurately represent a phenomenon can only provide an inaccurate and incomplete (and quite possibly misguided) understanding of the phenomenon. Thus, its usefulness will always be limited to an unknown degree. For example, the Ptolemaic model of the solar system had significant predictive power in accounting for the motion of the planets despite being an Earth-centered model that did not accurately represent the solar system (Benson, 2012). If the scientists and philosophers of an earlier era had not discarded the Ptolemaic model in favor of a model that more accurately represented the solar system, it is unlikely that civilization could have made many of the advancements that have improved humanity’s situation. One can argue that in the long run theories and models that do not accurately represent the phenomena they aim to explain will be less useful than those that do.

The alternative school of thought takes what Du Gay and Vikkelsø (2017) call a metaphysical stance and essentially treats the organization as a fiction. “People (i.e., individuals) have goals; collectivities of people do not” (Cyert & March, 1963, p. 26). This metaphysical stance is exemplified in the postmodern approach to organization studies in which organizations are viewed as “sets of recursive practices sustained by resource appropriation and rules” (Miller & Fox, 2015, p. 90). An organization is nothing more than a human construct defined by the norms and expectations of its members who must continually negotiate and affirm those norms and expectations. It is simply a way that a group of people have settled on interacting to achieve their respective ends. One can trace the roots of this metaphysical stance to an earlier period of modern sociology. Weber (1921-1922/2019) argued that scientific examination of social phenomena seeks to understand the “contextual meaning of action” and requires explanations of the behavior of individuals because individuals are the “sole understandable agents of meaningfully oriented action” (p. 90-91).

Simon (1945/1997) noted as far back as the late 1940s that organizations can be conceptualized as patterns of group behavior in a very broad sense. Simon argued that the term organization simply referred to the relations among a group of people. Moreover, Simon maintained that decisions associated with carrying out the physical tasks of achieving the agreed upon objectives of an organization are not made by the organization per se but by people acting as members of the organization. In this sense, the term organization connotes both a type of group and the malleable repeated patterns of social interactions employed by the members of a group. As such, a decision to obtain and assimilate a technology is made by one or more members of an organization (e.g., a for-profit commercial enterprise) acting in accordance with the agreed upon norms that govern their behavior regarding such matters.

The debate between the two schools of thought in organization studies is essentially about whether the phenomenon we call organization exists. It is a bit like asking whether human thought exists. Although one cannot touch a human thought, most would agree there exists such a thing. It manifests itself through human activity. Much can be learned about the nature of human thought by studying the human activity that results from it. Likewise, if what we call an organization exists, it too manifests itself through human activity. Examining the human activity associated with organizations seems a prudent approach to understanding the nature of organizations. As such, the goal in applying theory to the examination of macro level organizational phenomena is to neither reify the organization nor disappear the organization entirely. Although it might be more convenient to speak of an organization taking some action or pursuing some goal, it is important to recognize that it is actually the members of the organization that establish the goals and take the requisite actions in the name of the organization.

Models of University Technology Transfer

Scholars have applied the major economics-based theories to develop various frameworks and models of university technology transfer (see e.g., Bamford et al., 2024; Calcagnini & Favaretto, 2016; Dahlborg et al., 2017; Galan-Muros & Davey, 2019; Heinzl et al., 2013; Landry et al., 2007; O’Shea et al., 2008). In many cases, these frameworks and models are not comprehensive. Instead, they are highly specialized and intended to provide insights into only a small facet of technology transfer.

Although various models of technology transfer have been applied to provide different insights into the phenomenon of university technology transfer, they all have their shortcomings. Generally, they all suffer from at least one of several limitations. First, most tend to emphasize the perspective of supply-side actors (e.g., universities) even in the cases where demand-side actors are explicitly factored into the model. Second, most facilitate either descriptive or correlational research. Consequently, the results of such research cannot establish causal relationships but instead can only present causal postulations. Finally, they all seem to reify their elements or the organization construct. Thus, they risk minimizing or eliminating the human element which ignores the sociological nature of technology transfer. Such minimization has the potential to detrimentally distort our understanding of university technology transfer.

A Human-CenteredFramework

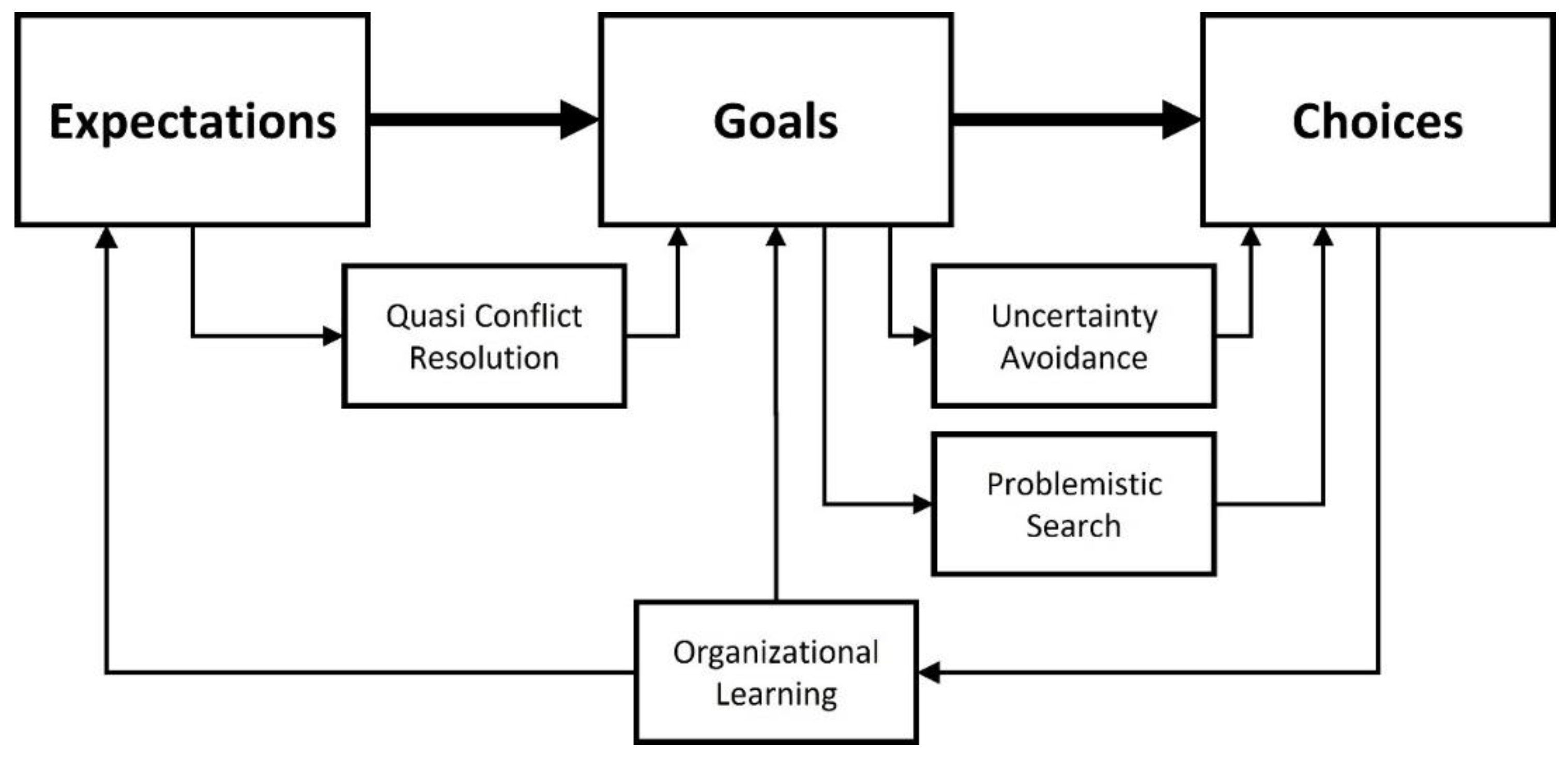

The theoretical basis for the human-centered framework is primarily founded on the behavioral theory of the firm (Cyert & March, 1963) and the administrative theory that Simon (1945/1997) proposed. With the behavioral theory of the firm, Cyert and March sought to explain the economic decision making of businesses in a way that connected economic research and organization research. The theory as presented is a process-oriented verbal theory comprised of three variable categories and four relational concepts.

Figure 1 presents the theory diagrammatically to facilitate a better understanding.

The administrative theory that Simon (1945/1997) proposed sought to better deepen our understanding of phenomena attributed to organizations. To do so, the theory focused on the decision processes that organization members employ. The organization as a construct is conceptualized as a pattern of communications and human relations formed to carry out two primary functions – making decisions and taking actions. Deciding and acting are inextricably linked, somewhat analogous to entangled quantum particles in physics. As such, understanding organizational decision making can provide insights into organizational actions.

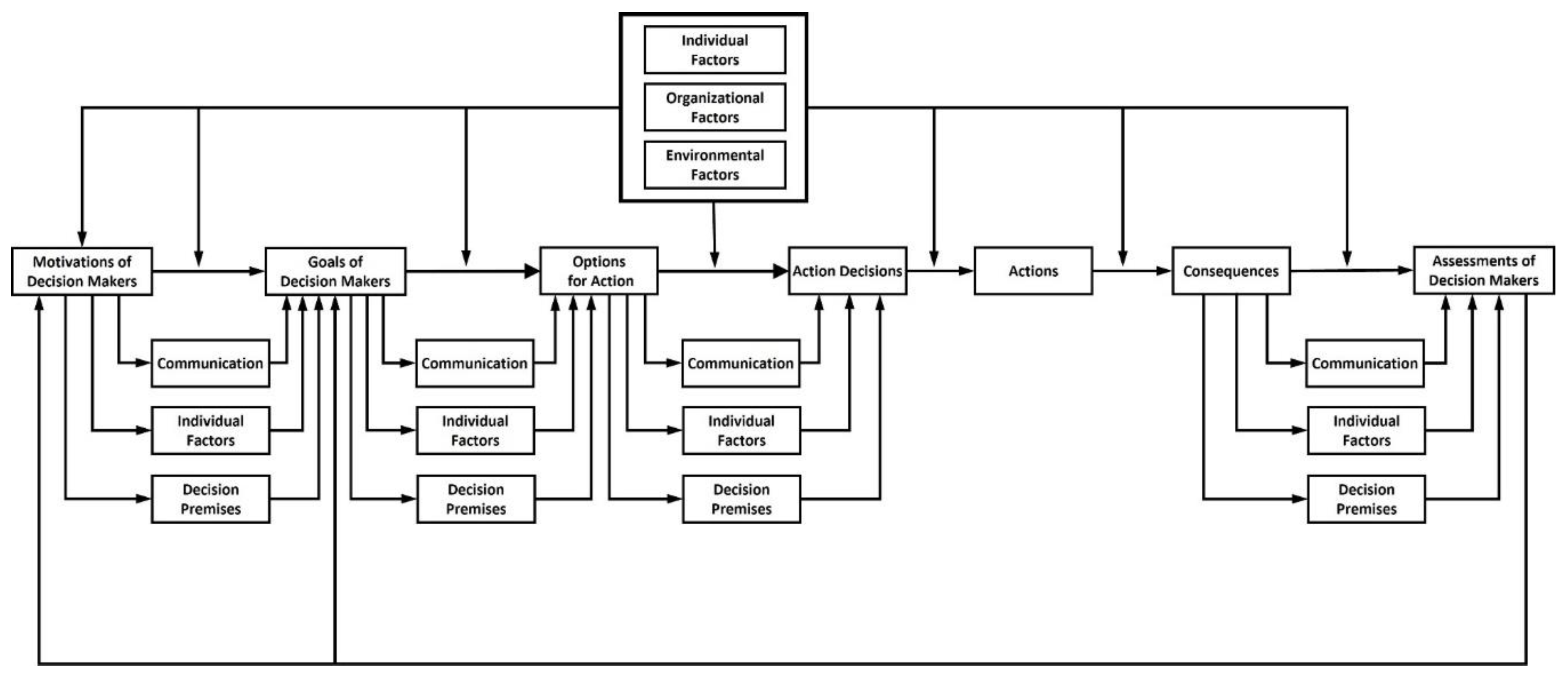

The proposed human-centered framework seeks to integrate Cyert and March’s behavioral theory of the firm and Simon’s administrative theory into a framework suitable for examining macro level organizational phenomena (

Figure 2). This integration aims to recognize the human element of organization without disappearing the construct of organization and to understand macro level organization phenomena without reifying the organization construct and disregarding the human element.

There are two basic premises of the human-centered framework. The first premise is that all organizational activity manifests itself through the activities of the members of the organization. The second premise is that humans create organizations to perform coordinated actions that impact the physical and social world in such a way as to produce an actual future reality that resembles a desired future reality as closely as possible.

The key variable categories in this human-centered framework are motivations, goal decisions, options for actions, action decisions, actions, consequences, and assessments. Each key variable category feeds into the next. Decision premises, individual factors, and communication mediate the relationship between motivations and goal decisions, between goal decisions and options for action, between options for action and action decisions, and between consequences and assessments.

Decision premises express the beliefs of members of the organization and take one of two forms. Etiological decision premises, what Simon (1945/1997) called factual decision premises, are assertions or propositions about existence and the nature of cause-and-effect relationships among events and phenomena of the physical and social world in which the individual employing the assertion or proposition has a propositional attitude of belief that the assertion or proposition corresponds with reality. However, etiological decision premises may or may not be true. In contrast, values decision premises denote beliefs about the way things "ought" to be. They are normative in nature. Values decision premises are often the decisions of individuals in the upper levels of the organization hierarchy, by which other organization members lower in the hierarchy agree to abide because of the established norms and patterns of behavior of the organization.

Factors associated with individual organization members, the organization as a collectivity, and the environment in which the organization operates act as moderators of the relationships between the key variable categories. These factors also directly influence the motivations that drive actions taken in the name of the organization (i.e., organizational action). Assessments of the consequences of these actions produce modifications of the motivations for action taken on behalf of the organization and goal decisions ascribed to the organization, which form a part of the learning mechanism for the organization. Note that individual factors can function as either mediators or moderators in the human-centered framework.

Motivation is not an explicit component of either the behavioral theory of the firm or administrative theory. However, if one accepts that all organization activity manifests itself through human activity and all human activity is driven by human behavior, which is often determined by human motivations compelled by human needs (Maslow, 1943), then organization activity is largely determined by the motivations of its members. Motives are one of several factors than can cause an individual to pursue a course of action (Simon, 1945/1997). While all human behavior is determined, not all human behavior is motivated (Maslow). In the current state of civilization and under normal conditions, the most predominant basic human needs (physiological, safety, and love as categorized and defined by Maslow) tend to be significantly satisfied and therefore can usually be considered non-existent when trying to understand what truly motivates human behavior (Maslow). As such, esteem and self-actualization needs are the primary motivators of human behaviors (Maslow) and thus are likely the primary motivators of activity ascribed to organizations. However, this is not always the case. Safety and love needs can present themselves quite forcefully as motivators for actions taken under the aegis of an organization.

In large part, motivations drive the goal decisions of an organization. Organizational goals are one of the three variable categories of the behavioral theory of the firm (Cyert & March, 1963). In administrative theory, goals are an element in establishing the equilibrium of the organization (Simon, 1945/1997). The challenge is to specify the goals of an organization without “postulating an ‘organizational mind’” (Cyert & March, 1963, p. 26) which reifies the organization construct. The influence of those for whom the success of the organization provides some utility, which includes both members and non-members of the organization (e.g., customers of a for-profit commercial enterprise), drives the goals of an organization (Simon). One can argue that any goal established by an organization member who legally and legitimately commits organization resources to achieve it is a goal of the organization.

For many private sector organizations, economic profit is an important goal, if not the primary goal. Even if the motivations that drive goal decisions of organizations are rooted in the esteem and self-actualization needs of organization members, the goals associated with fulfilling those needs seem to get translated or transmuted into targets for economic profit and wealth accumulation at least in part. Even in the case of non-profit organizations, generating economic profit or at the very least achieving resource equilibrium is a necessary consideration.

In the proposed human-centered framework, decision premises, individual factors, and communication are the means through which organization members transform motivations into goals for the organization. Decision premises are foundational elements of administrative theory. Organization members can use decision premises to formulate and arrive at goal decisions or the justify goal decisions after they are made. Individual factors, such as psychological processes and personality characteristics, also influence how organization members transform motivations into goals for the organization. Communication is necessary where various members control the resources required to achieve goals, which may also necessitate that the organization members form a consensus about a goal decision related to a potentiality (i.e., an instance in which an individual or collectivity must choose between two or more alternative courses of action, including the option not to act at all).

Once the goals of the organization are established, the issue becomes what course of action needs to be taken to achieve those goals. Applying the principle of equifinality (Gresov & Drazin, 1997; von Bertalanffy, 1969), one can surmise that many, if not most, organization goals can be attained by multiple possible means. These multiple possible means constitute the options for action available to the members of the organization for attaining the goals. Some options for action will be readily apparent to organization members. Others will present themselves only through an active search for alternatives. However, the principle of bounded rationality suggests that the options for action considered will not be comprehensive because various factors will constrain the number of options that organization members can and will consider (Simon, 1955; Simon, 1957; Simon, 1972; Simon, 1982). Many, if not most, of these constraints likely manifest as decision premises. Additionally, individual factors will influence how organization members interpret and respond to organization goals.

Goal decisions lead to a perceived set of options for achieving them through the mediating influence of decision premises, individual factors, and communication. Decision premises provide guiderails for determining which options are acceptable. Factors such as individual cognitive processes will shape how organization decision makers perceive various alternatives for achieving the goals of the organization. In the organizational context, communication plays a large role in how organization decision makers obtain, perceive, and interpret the data and information that goes into formulating and assessing the options for actions.

Organization members make decisions about what actions to take to achieve the goals of the organization based on the set of alternatives they generate. This is analogous to the choice variable category in the behavioral theory of the firm. Decision premises, individual factors, and communication are the means through which options for action are translated into action decisions the same as with the transformation of motivations into goals and goals into options for action. Organizational expectations are another variable category in the behavioral theory of the firm. Like other various theories of business decision making, the behavioral theory of the firm assumes that estimates of investment and return, resource use, desired and undesired outcomes, and adverse effects (or more generally the relationship between actions and consequences) heavily influence the behavior of organization members (Cyert & March, 1963). In the human-centered theory, these expectations are captured in etiological decision premises that mediate the relationship between options for actions and action decisions.

Once the relevant organization members decide on a course of action to attain the goals ascribed to the organization, various members perform tasks necessary to implement the action. The action either produces consequences, some of which may be unanticipated and contrary to the goals of the organization, or they have no effect at all in bringing about the desired future state that the organization members sought. Thus, organization members make assessments about the results of the action taken. Once again, decision premises, individual factors, and communication surface as the means for transitioning from one variable category to another – in this case results are translated into assessments of the appropriateness and usefulness of the action taken. These assessments also feed back into the motivations and goals of the organization as part of the learning and planning mechanism. Finally, factors about the individual organization members, the organization, and the environment in which the organization operates moderate the relationships between the primary variable categories.

In the behavioral theory of the firm, four major relational concepts connect the three variable categories of organization goals, organization expectations, and organization choice. These relational concepts are quasi-resolution of conflict, uncertainty avoidance, problemistic search, and organizational learning (Cyert & March, 1963). The human-centered framework accommodates each of these relational concepts.

Cyert and March (1963) argued that most organizations exist and function with significant amounts of underlying goal conflicts and without internal consensus regarding goals. This differs from most reifications of the organization construct. As Cyert and March noted, organizations do not eliminate conflicts by reducing all goals to a common facet or making all goals consistent with one another. Instead, organizations pursue quasi-resolution of conflict through two primary means. One option is to use acceptable-level (rather than optimal-level) criteria that underexploit opportunities to leave excess resources to absorb potential inconsistencies in goals and decisions (Cyert & March). This would suggest that optimization is often not the objective. The other option for quasi-resolution of goal conflicts is to tackle goals sequentially thus creating a time buffer between conflicting goals and allowing them to be addressed in an asynchronous manner (Cyert & March). In the proposed human-centered framework, quasi-resolution of conflict is captured in the goals of decision makers which are mediated by communication.

Empirical research provides strong evidence that organizations avoid uncertainty rather than try to account for uncertainty in decision making through normative approaches such as uncertainty equivalents and game theory (Cyert & March, 1963). This tendency can be represented in the human-centered framework as a moderating organization factor as well as with decision premises or individual factors which act as mediating mechanisms.

In the behavioral theory of the firm, organizations are stimulated to search for solutions to problems (i.e., problemistic search) that help them attain their goals (Cyert & March, 1963). Problemistic search is captured by the goal decisions and options for actions elements of the proposed human-centered framework. It is essentially a description of the nature of the relationship between goal decisions and options for actions.

Organizational learning, the fourth relational concept in the behavioral theory of the firm, is concerned with the adaptation of organization goals, attention rules, and search rules (Cyert & March, 1963). It is incorporated into the human-centered framework in the assessment of the consequences attributed to organization actions, which directly influence motivations and goal decisions, whose relationship in turn is partially mediated by various decision premises. Additionally, organizational learning itself is an action that is dependent on action decisions which are driven by motivations and goal decisions.

Case Study: Original Analysis

Aksoy and Beaudry (2021) examined the question of whether license compensation scheme is associated with licensee organization size. The study was from the perspective of the university. Aksoy and Beaudry tested the following three groups of hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1. The number of licenses that a university grants to startup companies is:

-

(1)

negatively associated with the number of licenses generating royalties,

-

(2)

negatively associated with the amount of royalty income generated,

-

(3)

negatively associated with the amount of upfront fixed fees,

-

(4)

positively associated with the number of licenses with equity compensation for the university, and

-

(5)

positively associated with the amount of license income the university obtains from sales of equity.

Hypothesis 2. The number of licenses that a university grants to large companies is:

-

(a)

negatively associated the number of licenses generating royalties,

-

(b)

negatively associated with the amount of royalty income generated, and

-

(c)

positively associated with the amount of upfront fixed fees.

Hypothesis 3. The number of licenses that a university grants to small companies is:

-

(a)

positively associated with the number of licenses generating royalties,

-

(b)

positively associated with the amount of royalty income generated, and

-

(c)

negatively associated with the amount of upfront fixed fees.

Aksoy and Beaudry (2021) analyzed the data using an ordinary least square (OLS) methodology and hierarchical regression. They applied a transformation to the data for several of the predictor variables because the variables exhibited skewness values exceeding 1.5 or were outside the range of 1.5 to 4.5 for kurtosis values. The model used in the analysis was as follows:

where the subscript

i indicates the university,

indicates the predictor variables,

indicates the dummy variables, and

is an error term.

Based on the results of their analysis, Aksoy and Beaudry (2021) concluded that there was a statistically significant association between the type of compensation employed in a license for university-owned technology and the size of the licensing organization. But this analysis is only correlation and does not explain causality – that is, why does the type of compensation used in technology transfer licenses correlate with the size of the licensing organization? One could argue that this is the more interesting question. Moreover, the authors’ research design does not reflect the fact that many, if not most, technology transfer licenses that university technology transfer staff execute incorporate multiple types of compensation.

In addition to the above limitations, Aksoy and Beaudry (2021) make generalizations that are not supported by their analysis. They assert that upfront fixed fee compensation (which they state the literature suggests is the optimal compensation scheme for both supply side and demand side participants in a university technology transfer transaction) is not always feasible or desirable for either party because of perceived risks and rewards, absorptive capacity, and financial slack. This conclusion goes well beyond the data and what was examined in their study and is not directly supported by their findings. Additionally, these conclusions reify the organization construct. The authors commit an error of attribution by ascribing decisions and actions to an abstract construct. At best, they can only conclude that their empirical results demonstrate a correlation between the choice of compensation structure employed in licenses to facilitate the transfer of university-owned technology and the size of the licensing organization, which is at odds with the optimal compensation structure suggested in the literature. Even more, the results of the study do not support the authors’ call for public policy to “level the playing field” (Aksoy & Beaudry, 2021, p. 2051) in hopes of increasing the incidence of university-industry technology transfer.

Case Study: Applying the Human-Centered Framework

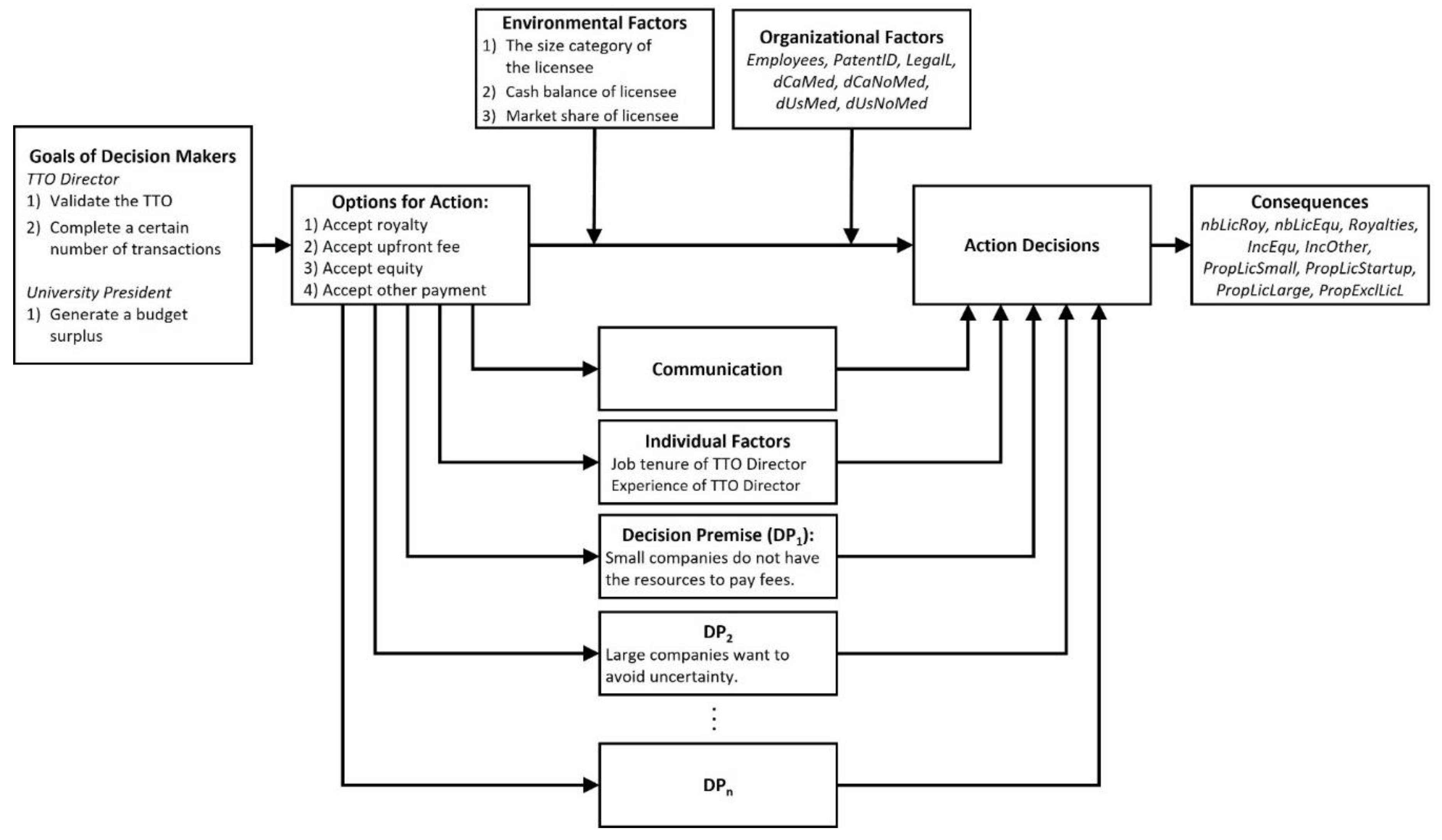

Applying the human-centered framework, one can model university technology transfer from either the supply side or the demand side. To begin, the variables used in Aksoy and Beaudry (2021) were translated into a supply side model of university technology transfer derived from the human-centered framework (

Figure 3).

This translation highlights the two categories of variables used in the analysis. Predictor variables predominantly comprise organizational factors. It is logical that the response variables used in the analysis reflect the consequences of action decisions. However, it is notable that several of the predictor variables used in the analysis are better characterized as falling under the consequences component of the model. Although these variables appear to describe the licensing organization in their use as predictor variables, they actually describe the aggregate consequences of organizational actions.

Application of the human-centered framework also makes plain the non-causal nature of the correlational analysis. Organizational factors such as those used in the study are more likely to be moderators that influence the ultimate decision of which compensation scheme a university employs in a technology transfer license.

To reveal options for other types of analysis that one could perform to investigate the research question, the initial translation of the variables to the supply side model is extended by expounding the other elements of the model (

Figure 4). Potential variables for environmental factors are postulated in addition to variables and conditions for goal decisions, individual factors, and decision premises.

Applying the human-centered framework helps to identify other potential causal factors to consider. To begin, attributes of the company that is in-licensing the technology can be directly considered. From the perspective of the university, these are environmental factors. Various possible decision premises become more evident as potential causal factors that lead university technology transfer professionals to stray from the optimal compensation structures posited in the literature. Also, individual factors could be theoretically plausible causal contributors to help explain why university technology transfer professionals often accept compensation arrangements in technology licenses that are different than the optimal compensation strategies discussed in the literature. For example, it could be that technology transfer professionals move along a learning curve that eventually leads them to recognize the benefits of compensation arrangements that are closer to the optimal compensation forms discussed in the literature. The total years of technology transfer experience of the director of the university’s technology transfer office could be used as a proxy to operationalize this concept.

It is important to note that university technology transfer staff do not unilaterally decide the compensation structure employed in a technology license. This is determined through an interplay between the agents of the supply side organization and the demand side organization. In effect, the compensation structure employed in a technology license is determined by social interaction – that is, it is determined through sociological processes. This is not captured in the original examination of Aksoy and Beaudry (2021), which ignores the demand side perspective completely, which is likely a consequence of reifying the organization construct and other concepts used in the analysis.

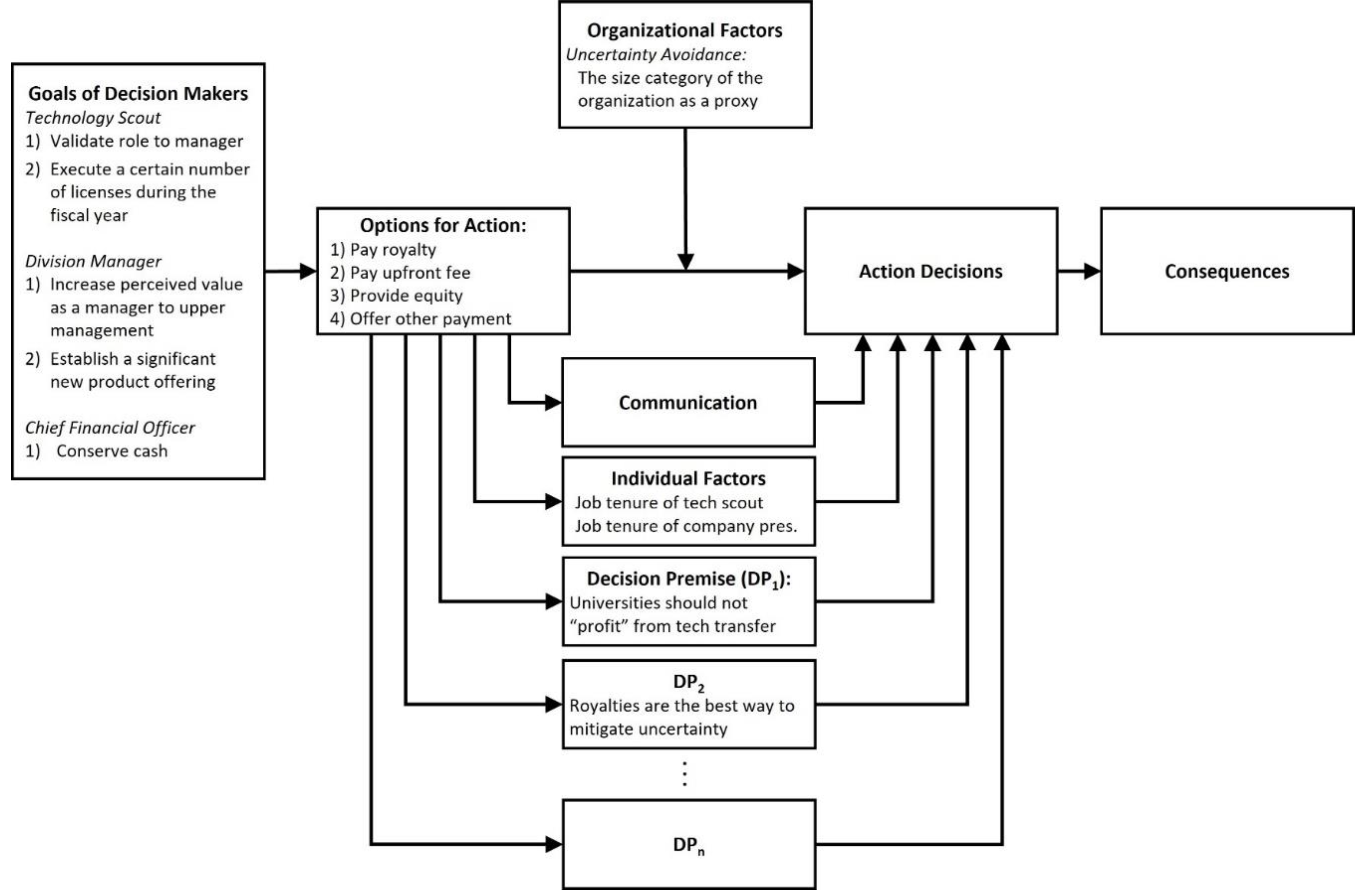

To wit, a demand side model of university technology transfer can also be derived from the human-centered framework and applied to examine the research question studied in Aksoy and Beaudry (2021) from the perspective of the company licensing the technology (

Figure 5). Although the components of the model are the same as the supply side perspective, different factors could be driving the licensee’s choice of compensation structure.

In the demand-side model of university technology transfer, the primary option for action that is of interest is again which compensation structure to agree to use in the license agreement. Doing so has some probability of successfully helping to achieve one or more organizational goals that are derived from the motivations of the organization members charged with making the decision. However, the probability distribution for successfully assimilating a given technology is typically unknown and very likely unknowable. This makes the technology transfer opportunity subject to Knightian uncertainty. This brings to bear the notion of uncertainty avoidance, which is an organizational factor from the perspective of the licensing organization. It could be operationalized using the size category of the licensing organization. Bahcall (2019) argued that firms tend to shift from pursuing what he called “loonshot” projects to franchise projects as the size of the firm increased above 250 employees. It seems plausible that such a shift is due to uncertainty avoidance, at least in part.

Cyert and March (1963) described uncertainty avoidance as a characteristic of organizational decision making. However, uncertainty avoidance is not limited to only organizational contexts. Moreover, if one accepts the premise that all organization activity manifests itself through the activities of the members of an organization, then uncertainty avoidance could also be thought of as an individual factor. However, for the purposes of this examination it is considered an organizational factor.

The relationship between the option for action and the action decision is mediated by communication among relevant organization members involved in making the decision on behalf of the organization and individual factors associated with organization members involved in making the decision. Communication and individual factors act in concert with various decision premises that the organization members use in selecting a preferred course of action and advocating for it. These decisions premises are likely causal factors that influence a licensing organization to employ compensation arrangements in technology licensing agreements that differ from the optimal compensation form suggested in the literature.