Submitted:

26 October 2024

Posted:

28 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Considerations

2.2. General Description

2.3. Area of Study

2.4. Participants

2.5. Focus Groups

2.6. Data Analysis

2.7. Positionality and Reflexivity Statement

2.8. Data Presentation

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

| Characteristic | n (%) | Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Level of education | ||

| Male | 14 (58.3) | No education | 4 (16.7) |

| Female | 10 (41.7) | Primary | 10 (41.7) |

| Secondary | 4 (16.6) | ||

| Higher education | 6 (25.0) | ||

| Age | Years of experience | ||

| 28 - 38 | 6 (25.0) | 20 - 30 | 6 (25.0) |

| 39 - 49 | 9 (37.5) | 31 - 41 | 8 (33.3) |

| 50 - 60 | 4 (16.7) | 42 - 52 | 5 (20.8) |

| 61 - 71 | 5 (20.8) | 53 - 71 | 5 (20.8) |

3.2. Key themes Identified

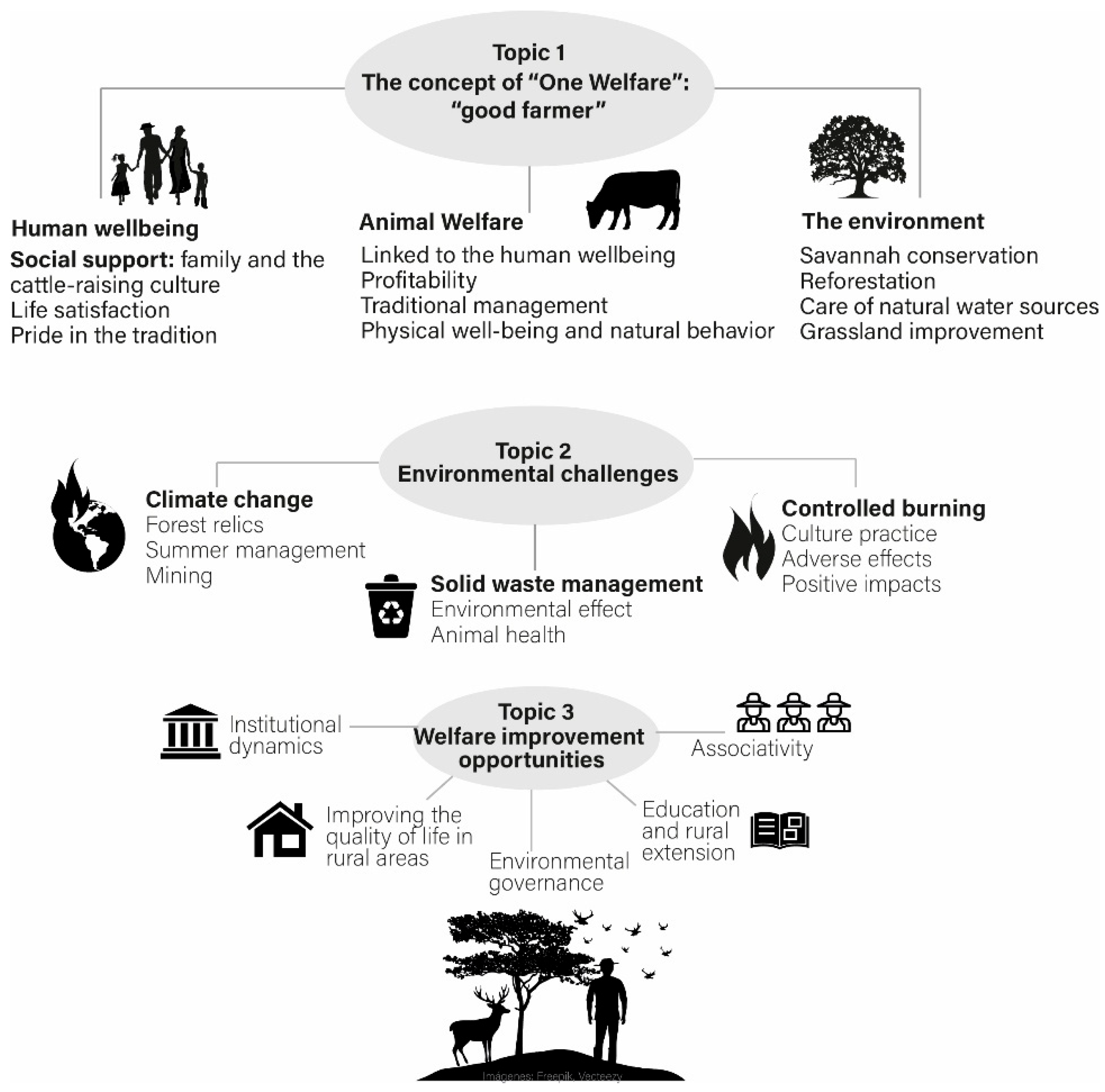

3.2.1. Theme 1: Socio-Cultural Factors Defining Human, Animal and Environmental Welfare “One Welfare”

Human Wellbeing

- a.

- The family is the centre of social unity in cattle-raising activities

- b.

- Life satisfaction

- c.

- Pride in tradition the “good farmer”

Animal Welfare

- a.

- Link with human welfare and the profitability of livestock farming

- b.

- Traditional management

- c.

- Physical well-being and natural behavior

Environment

- a.

- Savannah conservation

3.2.2. Theme 2: Environmental Challenges Affecting Human and Animal Welfare

- a.

- Climate change

- b.

- Solid waste management and disposal

- c.

- Controlled burning

3.2.3. Theme 3: Welfare Improvement Opportunities with a “One Welfare” Vision

- a.

- Institutional dynamics

- b.

- Associativity

- c.

- Improving the quality of life in rural areas.

- c.

- Environmental governance of the territory

- d.

- Education

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grace, J.; José, J.S.; Meir, P.; Miranda, H.S.; Montes, R.A. Productivity and Carbon Fluxes of Tropical Savannas. J Biogeogr 2006, 33, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdinan; Tjahjono, R.E.P.; Infrawan, D.Y.D.; Armanto, A.N.; Pratiwi, S.D.; Putra, E.I.; Yonvitner; Oktaviani, S.; Lestari, K.G.; Adi, R.F.; et al. Management Strategies of Tropical Savanna Ecosystem for Multiple Benefits of Community Livelihoods in Semiarid Region of Indonesia. World Development Sustainability 2024, 4, 100137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñuela, L.; Fernández, A. La Ganadería Ligada a Procesos de Conservación En La Sabana Inundable de La Orinoquia Livestock Activity Linked to Conservation Processes in the Orinoquia ’ s Flood Plains. Orinoquia 2010, 14, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, C. Estudio General de La Vegetación Nativa de Puerto Carreño (Vichada, Colombia). Caldasia 2006, 28, 165–177. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Restrepo, C.A.; Vera-Infanzón, R.R.; Rao, I.M. Predicting Methane Emissions, Animal-Environmental Metrics and Carbon Footprint from Brahman (Bos Indicus) Breeding Herd Systems Based on Long-Term Research on Grazing of Neotropical Savanna and Brachiaria Decumbens Pastures. Agric Syst 2020, 184, 102892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO LA FAO y Los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible- Cumplir La Agenda 2030 Mediante El Empoderamiento de Las Comunidades Locales; FAO: Roma, Italia ;, 2022; ISBN 978-92-5-137355-2.

- Campo, M. Del; Manteca, X.; de Lima, J.M.S.; Brito, G.; Hernández, P.; Sañudo, C.; Montossi, F. Effect of Different Finishing Strategies and Steer Temperament on Animal Welfare and Instrumental Meat Tenderness. Animals 2021, 11, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinillos, R.G.; Appleby, M.C.; Manteca, X.; Scott-Park, F.; Smith, C.; Velarde, A. One Welfare - A Platform for Improving Human and Animal Welfare. Veterinary Record 2016, 179, 412–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naylor, R.; Hamilton-Webb, A.; Little, R.; Maye, D. The ‘Good Farmer’: Farmer Identities and the Control of Exotic Livestock Disease in England. Sociol Ruralis 2018, 58, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, L.-A.; Calo, A. Assemblage and the ‘Good Farmer’: New Entrants to Crofting in Scotland. J Rural Stud 2020, 80, 532–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreasen, S.; Sandøe, P.; Waiblinger, S.; Forkman, B. Negative Attitudes of Danish Dairy Farmers to Their Livestock Correlates Negatively with Animal Welfare. Animal Welfare 2020, 29, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku Mensah, S.; Akanpabadai, T.A.; Diko, S.K.; Okyere, S.A.; Benamba, C. Prioritization of Climate Change Adaptation Strategies by Smallholder Farmers in Semi-Arid Savannah Agro-Ecological Zones: Insights from the Talensi District, Ghana. Journal of Social and Economic Development 2023, 25, 232–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, K.; Batung, E.; Kansanga, M.; Nyantakyi-Frimpong, H.; Luginaah, I. Livelihood Diversification Strategies and Resilience to Climate Change in Semi-Arid Northern Ghana. Clim Change 2021, 164, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi-Agyei, P.; Abalo, E.M.; Dougill, A.J.; Baffour-Ata, F. Motivations, Enablers and Barriers to the Adoption of Climate-Smart Agricultural Practices by Smallholder Farmers: Evidence from the Transitional and Savannah Agroecological Zones of Ghana. Regional Sustainability 2021, 2, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.J.; Levis, C.; Chaves, L.; Clement, C.R.; Soldati, G.T. Indigenous and Traditional Management Creates and Maintains the Diversity of Ecosystems of South American Tropical Savannas. Front Environ Sci 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, L. Two Good Interview Questions: Mobilizing the ‘Good Farmer’ and the ‘Good Day’ Concepts to Enable More-than-representational Research. Sociol Ruralis 2021, 61, 681–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICA Censos Pecuarios Nacional. Available online: https://www.ica.gov.co/areas/pecuaria/servicios/epidemiologia-veterinaria/censos-2016/censo-2018 (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Pitard, J. A Journey to the Centre of Self: Positioning the Researcher in Autoethnography. Qualitative Social Research 2017, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, L.A. From Human Wellbeing to Animal Welfare. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2021, 131, 941–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logstein, B.; Bjørkhaug, H. Good Animal Welfare in Norwegian Farmers’ Context. Can Both Industrial and Natural Conventions Be Achieved in the Social License to Farm? J Rural Stud 2023, 99, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirsky, S.; Tkach, C.; DiMatteo, M.R. What Are the Differences between Happiness and Self-Esteem. Soc Indic Res 2006, 78, 363–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Singer, B.H. Know Thyself and Become What You Are: A Eudaimonic Approach to Psychological Well-Being. J Happiness Stud 2008, 9, 13–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigors, B.; Wemelsfelder, F.; Lawrence, A.B. What Symbolises a “Good Farmer” When It Comes to Farm Animal Welfare? J Rural Stud 2023, 98, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, M.H.; Barrero-Melendro, J.; Sanchez, J.A. Study of the Feasibility of Proposed Measures to Assess Animal Welfare for Zebu Beef Farms within Pasture-Based Systems under Tropical Conditions. Animals 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, A.; Donoso, E.; Hernández, R.O.; Sanchez, J.A.; Romero, M.H. Assessment of Animal Welfare in Fattening Pig Farms Certified in Good Livestock Practices. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science 2024, 27, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vigors, B.; Lawrence, A. What Are the Positives? Exploring Positive Welfare Indicators in a Qualitative Interview Study with Livestock Farmers. Animals 2019, 9, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rault, J.-L.; Hintze, S.; Camerlink, I.; Yee, J.R. Positive Welfare and the Like: Distinct Views and a Proposed Framework. Front Vet Sci 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koç, G.; Uzmay, A. Determinants of Dairy Farmers’ Likelihood of Climate Change Adaptation in the Thrace Region of Turkey. Environ Dev Sustain 2022, 24, 9907–9928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardone, A.; Ronchi, B.; Lacetera, N.; Ranieri, M.S.; Bernabucci, U. Effects of Climate Changes on Animal Production and Sustainability of Livestock Systems. Livest Sci 2010, 130, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, C.J.C. Farm Animal Welfare—From the Farmers’ Perspective. Animals 2024, 14, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Downing, M.M.; Nejadhashemi, A.P.; Harrigan, T.; Woznicki, S.A. Climate Change and Livestock: Impacts, Adaptation, and Mitigation. Clim Risk Manag 2017, 16, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, P.; Boz, I.; ul Haq, S. Adaptation Options for Small Livestock Farmers Having Large Ruminants (Cattle and Buffalo) against Climate Change in Central Punjab Pakistan. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2020, 27, 17935–17948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.W. (Ray); Enticott, G. Good Methods for Good Farmers? Mapping the Language of Good Farming with “Diligent Farmers” in Hong Kong. J Rural Stud 2023, 100, 103005. [CrossRef]

- Vanegas-Cubillos, M.; Sylvester, J.; Villarino, E.; Pérez-Marulanda, L.; Ganzenmüller, R.; Löhr, K.; Bonatti, M.; Castro-Nunez, A. Forest Cover Changes and Public Policy: A Literature Review for Post-Conflict Colombia. Land use policy 2022, 114, 105981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptiste, B.; Pinedo-Vasquez, M.; Gutierrez-Velez, V.H.; Andrade, G.I.; Vieira, P.; Estupiñán-Suárez, L.M.; Londoño, M.C.; Laurance, W.; Lee, T.M. Greening Peace in Colombia. Nat Ecol Evol 2017, 1, 0102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, B.; Gil Posse, C.; Sergeeva, M.; Salas, M.F.; Wojczynski, S.; Hartinger, S.; Yglesias-González, M. Climate Change and Public Health in South America: A Scoping Review of Governance and Public Engagement Research. The Lancet Regional Health - Americas 2023, 26, 100603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richerzhagen, C.; Rodríguez de Francisco, J.; Weinsheimer, F.; Döhnert, A.; Kleiner, L.; Mayer, M.; Morawietz, J.; Philipp, E. Ecosystem-Based Adaptation Projects, More than Just Adaptation: Analysis of Social Benefits and Costs in Colombia. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019, 16, 4248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda-Alzate, Y.M.; García-Benau, M.A.; Gómez-Villegas, M. Materiality Assessment: The Case of Latin American Listed Companies. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 2022, 13, 88–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; Lamble, R.E.; Fensham, R.J.; Siddique, I. Effect of Woody Vegetation Clearing on Nutrient and Carbon Relations of Semi-Arid Dystrophic Savanna. Plant Soil 2010, 331, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durigan, G.; Pilon, N.A.L.; Abreu, R.C.R.; Hoffmann, W.A.; Martins, M.; Fiorillo, B.F.; Antunes, A.Z.; Carmignotto, A.P.; Maravalhas, J.B.; Vieira, J.; et al. No Net Loss of Species Diversity After Prescribed Fires in the Brazilian Savanna. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change 2020, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Haddad, T.; A. G. Viani, R.; G. B. Cava, M.; Durigan, G.; W. Veldman, J. Savannas after Afforestation: Assessment of Herbaceous Community Responses to Wildfire versus Native Tree Planting. Biotropica 2020, 52, 1206–1216. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Restrepo, C.A.; Vera, R.R.; Rao, I.M. Dynamics of Animal Performance, and Estimation of Carbon Footprint of Two Breeding Herds Grazing Native Neotropical Savannas in Eastern Colombia. Agric Ecosyst Environ 2019, 281, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aniah, P.; Kaunza-Nu-Dem, M.K.; Ayembilla, J.A. Smallholder Farmers’ Livelihood Adaptation to Climate Variability and Ecological Changes in the Savanna Agro Ecological Zone of Ghana. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maake, M.M.S.; Antwi, M.A. Farmer’s Perceptions of Effectiveness of Public Agricultural Extension Services in South Africa: An Exploratory Analysis of Associated Factors. Agric Food Secur 2022, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, E.; Pagella, T.; Mollee, E.; van Noordwijk, M. Relational Values in Locally Adaptive Farmer-to-Farmer Extension: How Important? Curr Opin Environ Sustain 2023, 65, 101363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizikova, L.; Nkonya, E.; Minah, M.; Hanisch, M.; Turaga, R.M.R.; Speranza, C.I.; Karthikeyan, M.; Tang, L.; Ghezzi-Kopel, K.; Kelly, J.; et al. A Scoping Review of the Contributions of Farmers’ Organizations to Smallholder Agriculture. Nat Food 2020, 1, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassem, H.S.; Alotaibi, B.A.; Muddassir, M.; Herab, A. Factors Influencing Farmers’ Satisfaction with the Quality of Agricultural Extension Services. Eval Program Plann 2021, 85, 101912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cash, D.W.; Belloy, P.G. Salience, Credibility and Legitimacy in a Rapidly Shifting World of Knowledge and Action. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaRue, K.; Daum, T.; Mausch, K.; Harris, D. Who Wants to Farm? Answers Depend on How You Ask: A Case Study on Youth Aspirations in Kenya. Eur J Dev Res 2021, 33, 885–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourne, M.; de Bruyn, L.L.; Prior, J. Participatory versus Traditional Agricultural Advisory Models for Training Farmers in Conservation Agriculture: A Comparative Analysis from Kenya. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 2021, 27, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junquera, V.; Rubenstein, D.I.; Grêt-Regamey, A.; Knaus, F. Structural Change in Agriculture and Farmers’ Social Contacts: Insights from a Swiss Mountain Region. Agric Syst 2022, 200, 103435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albizua, A.; Bennett, E.; Pascual, U.; Larocque, G. The Role of the Social Network Structure on the Spread of Intensive Agriculture: An Example from Navarre, Spain. Reg Environ Change 2020, 20, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, R.J.F. Seeing Through the ‘Good Farmer’s’ Eyes: Towards Developing an Understanding of the Social Symbolic Value of ‘Productivist’ Behaviour. Sociol Ruralis 2004, 44, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, P. V.; Forney, J.; Emery, S.B.; Wittman, H. Neoliberal Natures on the Farm: Farmer Autonomy and Cooperation in Comparative Perspective. J Rural Stud 2014, 36, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynne-Jones, S. Understanding Farmer Co-Operation: Exploring Practices of Social Relatedness and Emergent Affects. J Rural Stud 2017, 53, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohmwirth, C.; Hanisch, M. Women’s Active Participation and Gender Homogeneity: Evidence from the South Indian Dairy Cooperative Sector. J Rural Stud 2019, 72, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forney, J.; Häberli, I. Co-Operative Values beyond Hybridity: The Case of Farmers’ Organisations in the Swiss Dairy Sector. J Rural Stud 2017, 53, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICA Resolución 1634 de 2010. Available online: https://icbf.gov.co/cargues/avance/docs/resolucion_ica_1634_2010.htm (accessed on 4 August 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).