Introduction

In recent years, the impact of digital communication, especially through platforms such as Facebook, has been widely studied. Numerous research studies have shown how these social networks transform political communication and encourage citizens' participation in electoral processes. As Liçenji [

1] points out, these platforms enable direct interaction between politicians and citizens, eliminating traditional intermediaries and facilitating greater political participation (p. 239). However, the current literature presents important gaps when analyzing this phenomenon in local and sectional political contexts, particularly in Latin America. In countries such as Ecuador, research has mainly focused on presidential contests, leaving aside local electoral dynamics, despite the fact that these scenarios offer valuable opportunities to understand changes in digital political communication.

This study focuses on filling that gap in the literature by exploring the impact of digital propaganda in Ecuador's sectional elections. Unlike campaigns in established democracies, where advanced resources such as artificial intelligence and sophisticated segmentation techniques are used, digital campaigns in developing countries such as Ecuador tend to be more limited. These strategies rely on simple resources, such as memes and advertising spots, and depend heavily on the frequency of publication to capture the voter's attention. Moreover, interaction between candidates and voters tends to be limited, underscoring the need to analyze these empirical campaigns to understand how electoral decisions are shaped in environments with fewer technological resources.

The choice of Ecuador as a case study responds to a theoretical interest in understanding how vulnerable and polarized democracies are particularly susceptible to the influence of digital platforms. The country's political instability, combined with low levels of trust in institutions, offers an ideal environment to analyze how social networks amplify polarization and shape public perception [

2,

3]. Ecuador presents a unique scenario to examine how these platforms influence local elections, where candidates tend to have a closer link with voters, allowing for different dynamics to be observed than in presidential campaigns. This approach not only contributes to the understanding of Ecuadorian politics, but also provides insights that can be extrapolated to other democracies in crisis in Latin America.

Facebook has been selected as the main platform for analysis due to its relevance in the Ecuadorian digital ecosystem. In 2023, more than 69% of the Ecuadorian population were active users of social networks, and Facebook remained one of the most popular, with 15.3 million users and a monthly average of 12.7 million organic visits [

4]. Although other platforms such as TikTok and Instagram have grown, Facebook remains predominant, especially among voters in key provinces such as Guayas, Pichincha and Manabí. This relevance reinforces the relevance of studying its impact on political communication, as it allows for an in-depth analysis of how propaganda messages shape citizens' perceptions.

Unlike other more segmented platforms, such as X (formerly Twitter) or TikTok, Facebook offers a more open and accessible space, where content has a longer shelf life and can reach higher levels of interaction. Facebook's structure, based on collaborative content creation and voluntary user membership, facilitates the mass dissemination of political messages and allows for direct interaction between candidates and their audiences. This combination of characteristics makes Facebook an ideal environment to analyze how digital propaganda is constructed and consumed in local electoral contexts.

Despite its popularity and relevance in political communication, there is a notable absence of studies that address how the structure of digital communication on these platforms influences voters' decisions in local elections. This study seeks to contribute to the field of digital political communication by providing a detailed analysis of the influence of social media propaganda during the 2023 sectional elections in Ecuador. The research also focuses on the use of multimodal content and simple propaganda strategies, highlighting the importance of developing digital campaigns that go beyond repetition, and that offer content of value to foster a more critical and participatory electorate.

This approach responds to the recommendations of Tella and Adah [

5], who stress the importance of researching specific contexts to better understand local dynamics in digital communication (p. 15). By studying a country with a growing reliance on social media for public opinion formation, this research offers a unique perspective on the role of Facebook in an environment marked by political instability and the urgency of institutional accountability. The objective of this study is to elucidate the influence of propagandistic content on Facebook on voting decisions and public perceptions of candidates during the 2023 sectional elections in Imbabura, Ecuador, exploring how citizens perceive this content and how these perceptions affect both electoral behavior and the candidates' public image.

In sum, this study makes a significant contribution to the understanding of digital political communication in developing countries, providing valuable insights into how electoral perceptions and decisions are shaped in a local context. By focusing on Ecuador, it not only analyses a particular case, but also generates lessons that can be extrapolated to other similar contexts in the region, where democracies face challenges of legitimacy and social cohesion.

1. Literature Review

1.1. Dynamics of Social Media in the Electoral Scene

In the digital era, informational interaction has undergone a significant evolution, aligning itself with historical technological advances and transforming traditional media into interactive platforms. Political contents are not only propagated, but also debated in real time and without geographical limits [

6]. This phenomenon is not exclusive to new media; even established institutions such as the New York Times have adapted digital personalization strategies to capture the attention of their audiences [

7].

Facebook, with 2.99 billion monthly active users as of July 2023, represents an indispensable instrument for both personal and political communication. The platform has demonstrated its efficacy in political campaigns, as evidenced by the expenditure of over

$40 million on advertisements by Donald Trump's team during the 2020 US presidential election. However, it has also encountered considerable regulatory and financial challenges, including the

$725 million paid to settle the Cambridge Analytica lawsuit [

8].

The advent of social networks has had a profound impact on the structure and function of political content, giving rise to a new paradigm in communication that challenges traditional practices and demands a more collaborative and mediated approach. This transformation has shaped how individuals perceive and interact with their environment, influencing their engagement in public spaces [

7]. It has also redefined the landscape of political communication, with platforms like Facebook assuming a dominant role in disseminating political messages and facilitating electoral engagement [

9,

10].

The digital revolution has also introduced significant challenges, such as disinformation and new forms of propaganda, which profoundly affect the quality of public debate and democratic deliberation [

11]. These phenomena are not new in history, as information manipulation has been present in politics for centuries. What distinguishes digital platforms, however, is their ability to amplify these problems through personalization and segmentation algorithms, which encourage the rapid and massive dissemination of manipulative messages, creating polarized environments known as ‘information bubbles’ [

12]. This dynamic not only fragments public debate, but also reinforces pre-existing beliefs, making it difficult to expose contradictory ideas and weakening the foundations of pluralism necessary for democratic deliberation [

13].

Despite the risks, social media still offer a strategic channel for politicians to communicate their priorities and engage directly with voters [

14]. This possibility of real-time interaction allows political leaders to establish emotional and personalized connections with their audiences, overcoming the limitations of traditional media [

15]. However, this public visibility also brings challenges, as any message can be amplified and distorted quickly, affecting public perception in unpredictable ways and potentially eroding trust in democratic institutions [

16].

Therefore, while this study acknowledges the importance of the phenomenon of disinformation, it focuses primarily on analyzing how the new digital communication paradigm transforms the relationship between politicians and citizens. This paradigm not only facilitates greater political participation, but also redefines how citizens interact with political content, becoming active agents in the creation and dissemination of messages, which poses both opportunities and risks for contemporary democracy. In this digitized context, strategic communication has been reconfigured, with personalized messages and direct, real-time interaction transforming campaign strategies and citizen engagement [

17]. Effective communication with different modes and languages can be decisive in electoral outcomes.

It is true that while digital platforms have lowered barriers to participation in the public sphere, traditional media actors and political elites have managed to maintain significant influence in digital spaces [

18]. Several recent studies underline that these actors have shifted their economic, cultural and symbolic capital to digital platforms, using their pre-existing resources to maintain a dominant position on the public agenda. Research by Gilardi et al. [

19] shows that both traditional media and politicians have adapted their strategies to the digital environment, achieving a mutual influence between their respective agendas on platforms such as Twitter and Facebook, highlighting that digital agendas do not develop completely independently from traditional ones.

Similarly, Gyekye-Jandoh and Ahmed [

20] note that while digital platforms have opened up new opportunities for public participation, an imbalance in the influence of actors persists, with political and economic elites continuing to dictate public content, even in the digital context. This trend highlights that the fragmentation of content has not eliminated privilege, but rather expanded the platforms from which these dominant actors operate.

Thus, the claim that social media have eliminated traditional media's monopoly over the public conversation can be qualified. While it is true that digital platforms have diversified voices in the public sphere, evidence shows that traditional actors and elites maintain a significant position of power in defining public agendas and content. This influence continues to condition the participation of ordinary users, who lack the same level of resources or symbolic capital to compete with these dominant actors.

The growing access to the internet and platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, TikTok in Ecuador reflects this global trend, showing an intensive use that coincides with voting ages. This underlines the importance of these platforms in political communication strategies [

21]. Digitalization has enabled the development of new ways of measuring public opinion and predicting electoral behavior through the analysis of large volumes of data, a valuable methodology in various electoral contexts [

22,

23].

Interaction on these platforms, especially on Facebook, is manifested through specific behavior’s such as "likes", "comments" and "shares", which are analyses by algorithms to personalize the user experience and influence their political perception and behavior [

24,

25]. Despite the reluctance of platforms such as Facebook and Google to intervene in political content, studying content on these networks is crucial to understanding their impact on political deliberation [

24].

The Facebook marketing strategies of European political parties vary significantly between countries, using advanced targeting tactics and paid media to boost engagement [

26]. In Europe and North America, data mining, neuroscience, and artificial intelligence are used to develop manipulation strategies, while in developing countries, the strategy is often less sophisticated. The ability to study real-time metrics generated by digital platforms offers strategists powerful decision-making tools, using methodologies such as regression to anticipate outcomes [

27].

In this context, fundamental questions arise about the relationship between digital political communication and electoral participation: How do Ecuadorians perceive the persuasive, informative or annoying nature of the propaganda content disseminated on Facebook during the 2023 sectional elections in Imbabura? How does this digital interaction influence voting decisions and public perceptions of candidates? This study is framed within the intersection between politics, technology and democracy, seeking to delve into the dynamics that emerge from this convergence.

1.2. Construction and Reception of Propaganda Content

In the dynamic scenario of digital election campaigns, the generation and dissemination of content is multimodal, involving the strategic transmission of messages to shape voters' perceptions and behavior [

28]. This digital evolution has expanded communicative tactics, allowing political actors to use media to shape the political reality perceived by the public [

29].

According to Durán-Barba et al. [

30], concepts and ideologies play complementary roles in political communication. Concepts are strategic tools to influence or control specific circumstances, while ideology’s structure feelings and emotions, giving them coherence and justification. Careful conceptualization seeks not only to modify perceptions, but also to channel the emotions of the electorate, using ideologies that legitimize those emotions in a political context.

Digital platforms have democratized certain aspects of access to political communication, allowing candidates with fewer resources to challenge more advantaged rivals through more cost-effective and far-reaching campaigns [

31]. Reduced broadcasting costs have facilitated the entry of new actors into the electoral competition, especially through networks such as Twitter and Facebook, which allow for greater direct interaction with the electorate. Petrova et al. [

32] show that these platforms can reduce barriers for emerging candidates, allowing them to gain contributions and support by accessing new audiences. Likewise, Kreiss et al. [

24] highlight that the effectiveness of campaigns in these digital spaces does not depend solely on financial resources, but on the ability to strategically leverage the opportunities of each platform to mobilize voters.

However, while these platforms expand access to the public space, the playing field is not entirely level. Studies such as those by Dommett [

33] show that parties and candidates with greater infrastructure and pre-existing resources manage to maintain a significant advantage by employing sophisticated data analytics and strategies to maximize their impact. This suggests that while social media allows for greater competition and participation, the ability to challenge traditional actors depends on more than democratization of access, as success requires well-designed communication strategies and efficient use of available digital capital. In this context, Facebook has emerged as a critical arena for political campaigns, facilitating both the propagation of ideas and disinformation, and enabling the circumvention of electoral regulations [

34].

Electoral behavior in the 2016 US primaries showed that candidates tend to attack mainly those with better results in the polls, a strategy notably used against Donald Trump [

35]. In social media, visual resources such as metaphors, metonymies and analogies are used strategically to persuade, attack or defend, either from official accounts or through covert groups such as "troll centers". Lui et al. [

36] call these types of visual content "technologies of power" because of their influence on social mechanisms.

Facebook advertising, targeted to specific audiences, has become crucial in campaigns, and its effectiveness increases as elections approach [

37]. Memes have acquired an important role in political communication, as they effectively and economically engage audiences [

17]. Moreover, their capacity for rapid virality and their strong semiotic charge allow them to influence voting decisions even when their message lacks veracity.

This underlines the importance of understanding the role of social networks in the construction and reception of political propaganda. According to Kietzmann et al. [

38], social networks can be defined by seven building blocks: identity, conversations, exchanges, presence, relationships, reputation and groups. These elements reflect the complexity of online interaction and highlight how social networks shape and disseminate political content.

1.3. Multimodal Content in Propaganda Advertising

Electoral propaganda advertising has evolved considerably in the digital age, characterized by its multimodal nature that integrates texts, images, and sounds to create persuasive messages that reinforce the image of candidates and their political agendas [

39,

40]. Not only do these resources shape political identities, but they can also negatively frame opponents, significantly impacting voting intention [

41].

The effectiveness of these messages depends crucially on their ability to convey emotions and build the image of politicians, highlighting the importance of managing facial expressions and gestures as key emotional links with the electorate [

42,

43]. Moreover, the integration of different modes of communication not only reinforces the message but also enriches the electorate's perception, reflecting the complexity of communication in modern campaigns.

This digitized environment also requires greater attention to narrative and issue framing to resonate effectively with audiences [

44,

45].

Finally, visual propaganda and multimodal resources are crucial for forging the political personality and brand of candidates, underlining the interaction between the visual and the textual in shaping public opinion [

31,

46,

47,

48]. This multimodal approach not only addresses perception, but also the pragmatic interpretation of messages to understand how political contents are structured and received in the current digital context [

49]. It shows how the combination of verbal, visual and emotional elements intertwine to influence the perception and decision of the electorate in an increasingly digitized political context.

1.4. Implications of Digital Interaction on Electoral Preferences

Social networks have revolutionized electoral behavior, functioning as catalysts for political self-expression and mobilization [

50,

51,

52]. They influence electoral decision-making through the structure of personal networks and political homophily, which reinforces the concept of "correct vote" where elections reflect personal preferences [

53,

54]. These platforms transcend mere communication and become decisive tools in the electoral campaign, the dissemination of information, and the influence on the perception of the electorate [

55,

56,

57].

Social media engagement and its effect on voting intentions demonstrate how these platforms shape political participation, especially among young people [

58,

59]. In addition, studies in political psychology have revealed that emotions, such as gratitude, encourage electoral participation and the virality of messages significantly influences electoral behavior [

55,

56]

.

This new digital paradigm not only informs, but also actively shapes policy preferences and decisions, offering unprecedented personalization and segmentation [

53,

54,

60]. However, this environment presents significant challenges, such as misinformation and perception manipulation, which requires critical analysis and informed citizenship to ensure a healthy democracy [

61]. This complex landscape manifests the importance of addressing both the opportunities and risks associated with digital propaganda in voting decisions, emphasizing the need for an informed and critical citizenry in the digital age.

Despite growing apathy and skepticism towards politicians and politics in general, social media remains a fertile ground for political propaganda, demonstrating that content that evokes strong emotions can capture the attention of even those disenchanted with traditional politics. According to Berger et al. [

62], the tendency of this content to go viral suggests that, despite general rejection, propaganda that arouses intense emotions can motivate political interaction and reflection on digital platforms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design of the Studio

This study employed a mixed approach, combining qualitative and quantitative methods to analyze the influence of digital propaganda content on voters' perceptions and voting decisions during the 2023 sectional elections in Imbabura, Ecuador. Content analysis was the main approach used in both phases of the study, complemented by a multimodal component to examine visual elements in combination with texts posted on social networks. It is clarified that content analysis was not used, as this approach involves specific theoretical and methodological frameworks that were not applied in this work.

The study design was structured in two complementary phases. The first phase consisted of a qualitative content analysis of posts made on Facebook by candidates and their political organizations. The second phase involved the application of surveys to a representative sample of the electorate, the results of which were analyzed using advanced statistical techniques. This combined methodology allowed us to explore both the perceptions of the electorate and the relationship between digital content consumption and voting preferences.

This comprehensive approach answered the research questions: How do Ecuadorians perceive the persuasive, informative or annoying nature of the propaganda content disseminated on Facebook during the 2023 sectional elections in Imbabura, and how does this digital interaction influence voting decisions and public perceptions of the candidates? The combination of qualitative and quantitative phases offered a comprehensive view of the impact of propaganda content, linking voters' perceptions with their voting decisions, and providing a detailed analysis of the role of social networks in local electoral processes.

2.2. Fase Cualitativa: Análisis de Contenido y Multimodal

Content analysis was the main approach in this phase, applied to both textual and visual elements present in the Facebook posts of the candidates and their political organizations. This methodology allowed for the identification of recurrent themes, emotions and discursive tones that influence voters' perceptions. In addition, a multimodal analysis was incorporated to explore how the combination of visual resources, such as images and videos, with complementary texts reinforces the effectiveness of the propaganda message.

The analysis covered 263 publications, using tools such as Atlas.ti 23.4, ChatGPT and Gephi to process the data and generate semantic co-occurrence matrices. These techniques enabled the identification of relationships between prevailing emotions and campaign strategies, providing a comprehensive understanding of the impact of digital content.

During the process, 673 new codes and 335 new quotes were identified in 1007 paragraphs, allowing for the construction of meaningful categories to further explore the influence of the digital propaganda narrative on the electorate's perception.

The use of the AI-based intentional analysis tool Atlas.ti 23.4 enabled the definition of an analysis context aligned with the research guidelines and the study corpus. This facilitated the formulation of three fundamental questions for the content analysis in terms of recurrence and type of emotion: Are there specific argumentative elements associated with recurrent terms of positive emotion in propaganda content? How do recurrent terms identified with positive emotion contribute to persuasive content in Ecuadorian political campaigns? What are the recurrent terms most frequently used in messages identified with positive emotion?

This approach allowed us to interpret the strategic use of emotions in propaganda and their impact on campaigns, providing a more detailed view of how digital storytelling influences voters' perceptions and decisions.

2.3. Quantitative Phase: Survey and Factor Analysis

The second phase evaluated the electorate's perception of the consumption of political propaganda during the campaign. An analysis of the reach, use and incidence of the messages consumed through the platforms studied was carried out. A representative sample of the electoral population was selected and a survey validated by experts in political marketing, research methodology and statistics, using Microsoft Forms, was conducted by trained pollsters who visited the defined territory. This study integrated a mixed approach of content analysis and perceptions assessment through surveys. Although specific content consumption was not tracked directly, a filter question was included in the survey to ensure that only participants who acknowledged having consumed election-related content on social media were included. This strategy ensures valid exposure, whether direct or incidental, to the types of messages analyzed. Representativeness was ensured through stratified probability sampling proportional to the voting population in the province of Imbabura. This approach offers a consistent interpretation of how perceptions of propaganda content correlate with electoral decisions.

While this study does not establish a direct causal relationship between specific Facebook posts and voting decisions, it focuses on identifying correlations between general perceptions of propaganda content and voting behavior. This approach captures the broader influence of digital propaganda by measuring how exposure to campaign messages affects attitudes towards candidates and voting preferences. The study analyses the patterns of perception and their potential impact through content.

The selection criteria focused on the voting population between 16 and 65 years of age in each canton of the province of Imbabura. The inclusion of 16-18 year olds is based on Ecuador's electoral regulations, which allow for their optional participation in electoral processes. This segment of the electorate represents a relevant group for the research, as their media preferences and technological skills may influence how they respond to digital propaganda. Including these voters allows us to explore how the visual and emotional narrative of campaigns adapts to the expectations of younger generations.

The sample consisted of 384 surveys, determined through stratified probability sampling, considering the age, gender, socio-economic level and geographic region of the electorate. These were stratified proportionally by canton: Antonio Ante 38, Cotacachi 38, Ibarra 154, Otavalo 116, Pimampiro 19, Urcuquí 19 to obtain true and systematic results. Variables related to function, veracity, reception and interaction that may influence the perception and understanding of the political message in social networks were analyzed. The data was analyzed using SPSS, version 25.0.

Combined with statistical tools such as SPSS 25.0 for segmented analysis, identification of factors and their significant relationships. It was possible to identify F1= level of propaganda consumption, F2= function of message use, F3= impact on voting decision and F4= role of message. It allowed the rotation of topics with the intention of interpreting and understanding the relationship between the content broadcast and the impact on voters' voting decisions. This methodology facilitates not only the reduction of the dimensionality of the data, but also the extraction and rotation of themes, allowing the synthesis of emerging common patterns in a clearer and more meaningful way.

For the interpretation and understanding of the research, through hermeneutic critical analysis and the application of techniques such as thematic analysis based on factor analysis, the role of Facebook platforms in the perceived use and consumption of the propaganda message in electoral contests was discussed, trying to understand the statistical data regarding voter perceptions, the qualitative interpretations of the propaganda content and its possible association with electoral results.

3. Results

The results of this study offer important practical implications for the design of electoral campaigns in local contexts. First, it was identified that the effectiveness of digital content lies not only in the frequency of publication, but in the emotional and contextual relevance of the message to voters. Campaigns that manage to align their narratives with the current needs and concerns of the electorate, such as employment and economic development, are more likely to generate impact. This underscores the importance of accurate audience segmentation and the need to design differentiated messages for specific demographic groups, ensuring that the issues addressed resonate with the priorities of each segment.

In a national political context characterized by low levels of acceptance of government figures and institutions, we examine how the population consumes and interacts with political information on social networks, providing important insights into the relationship between digital political communication and electoral participation in Ecuador.

Table 1 presents a marked lack of interest in political dialogue among Ecuadorian citizens, with 67.47% of respondents showing a reluctance to participate in surveys related to political issues. This reluctance is divided into three key categories. The first, Total Acceptance, includes 32.53% of respondents who expressed a willingness to participate in surveys unconditionally, demonstrating a basic level of interest in the process. The second category, acceptance conditional on rejection of current policies, corresponds to 40.22% of respondents who agreed to participate, but expressed specific dissatisfaction with the policies of the current Ecuadorian government. This group participates in political dialogue as a means of expressing their rejection of existing policies. Finally, 27.25% of respondents express a rejection of citizen participation due to distrust in the political system, which deters their participation in the process. These results highlight a context of generalized dissatisfaction with the country's political figures, in a scenario where only 9.07% approve of the National Assembly and 12.96% approve of the President. These data underline the urgent need to strengthen a responsible political culture in Ecuador.

3.1. Content Analysis of Communication

3.1.1. Factor or Theme 1: Level of Advertising Consumption

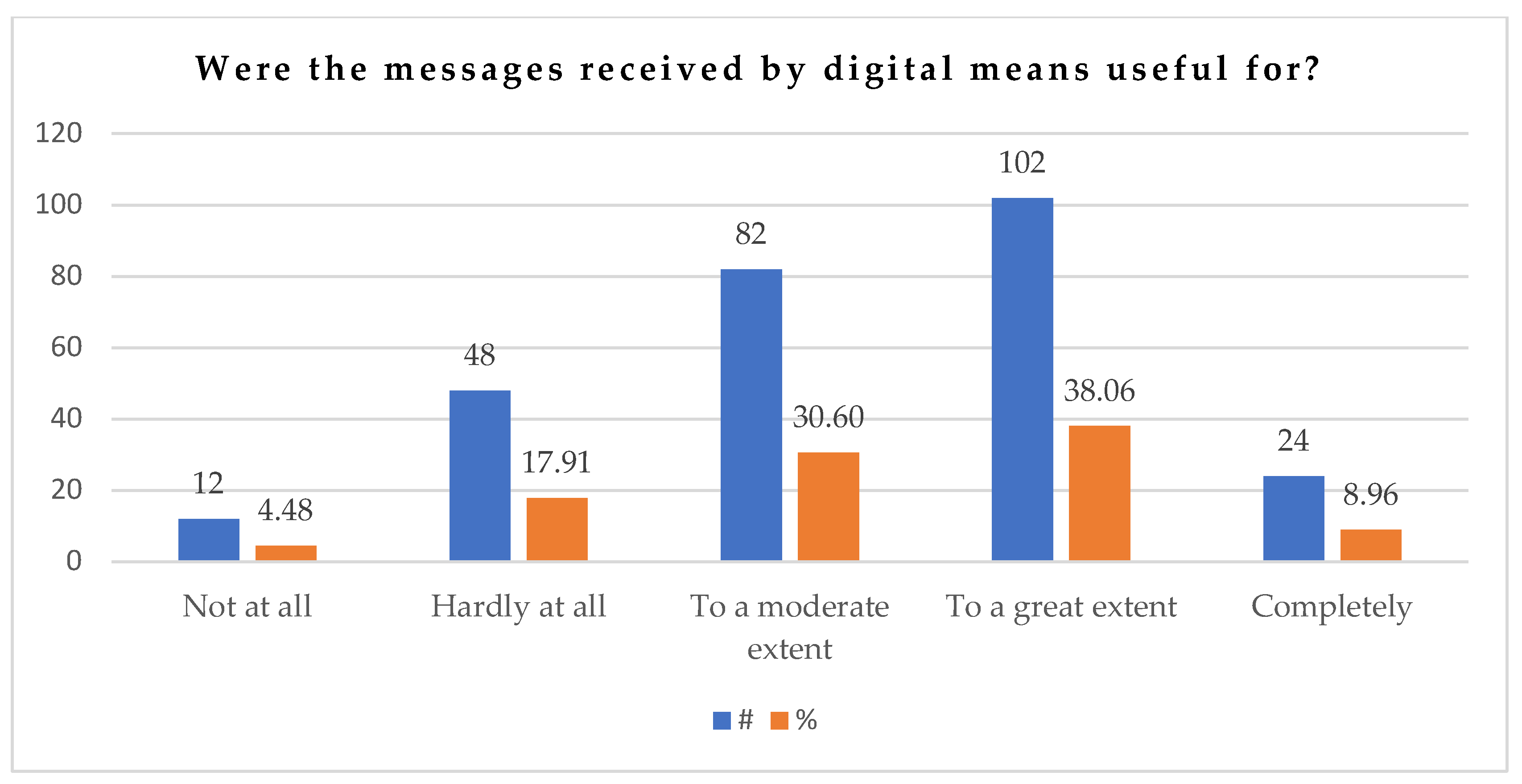

The study found that 38.06% of respondents thought that social media propaganda was particularly useful for 'finding out' about the candidates and their proposals. This result is in line with the objective of analyzing how the propaganda content on social media influences perceptions and choices in the Imbabura elections.

The study found that 38.06% of respondents found social media propaganda particularly useful for 'getting to know' candidates and their proposals. This finding is consistent with the objective of analyzing how social media propaganda discourse influences perceptions and voting decisions in the Imbabura elections. Although only 38.06% of respondents said that social network propaganda was useful for getting to know the candidates and their proposals, the analysis showed that the influence of propaganda content goes beyond the conscious perception of usefulness. Repetitive exposure, emotional resources and the integration of visual messages have a cumulative effect that contributes to the construction of the candidates' image and influences voting decisions, although voters are not always fully aware of this influence.

This finding is directly related to one of the research questions, which seeks to understand the role that these platforms play in the voting decision through the content emitted, highlighting the importance of social networks as information tools in the electoral process. Correlating these results with the metrics of interaction on the Facebook pages analyzed, the tendency of citizens to remain passive in direct political communication, preferring to use this content to inform themselves and prepare to vote, can be seen.

Were the messages received by digital means useful for?

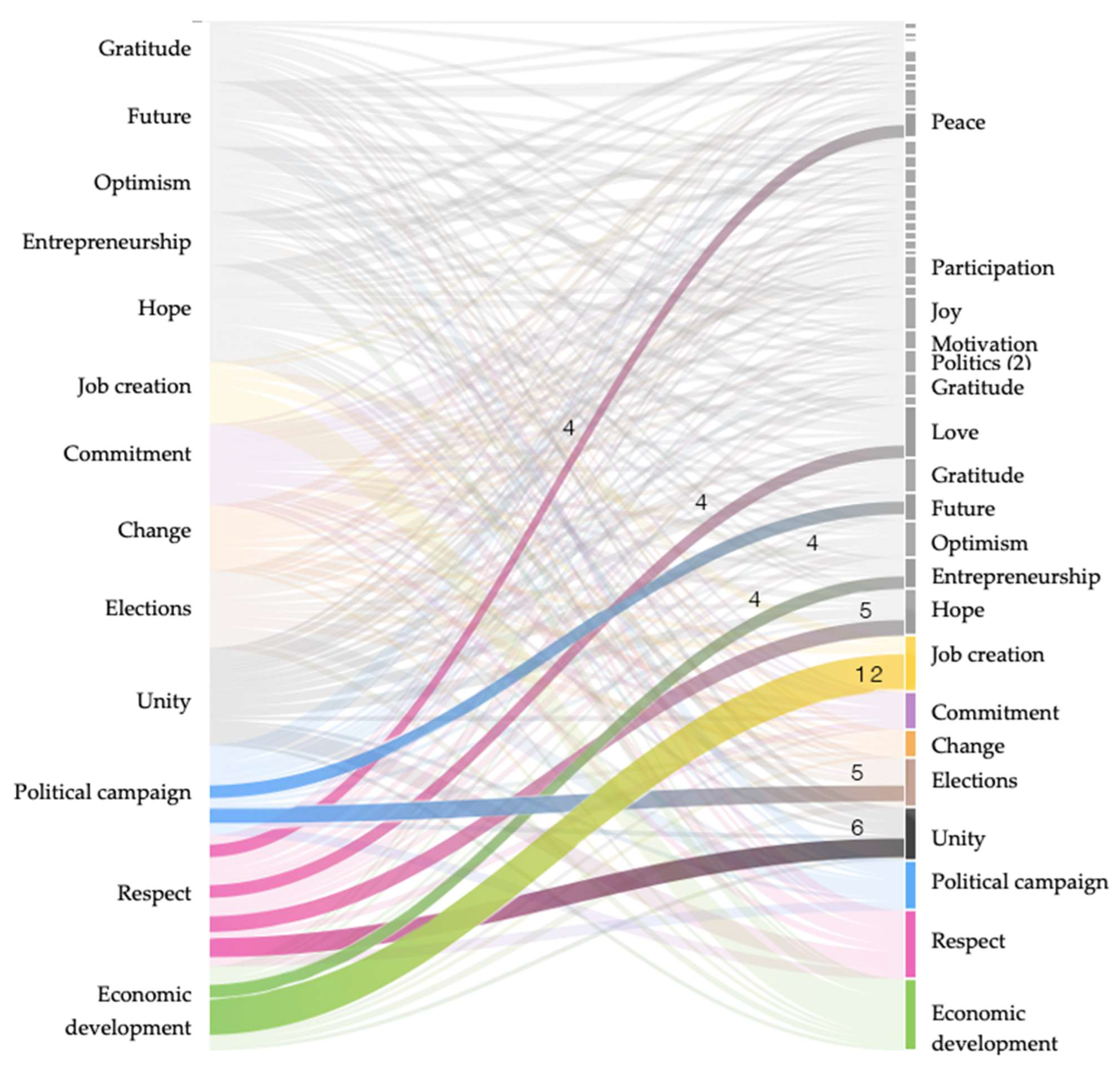

Frequency of key themes. The analysis identified eight thematic categories based on the interaction between two specific codes used within the same sentence in Facebook posts,

Figure 1. Each category is characterized by its frequency of occurrence. The frequency of occurrence of each category was measured by counting the recurring themes, emotions and formats in the 263 messages analyzed. Although frequency alone does not guarantee persuasion, previous research has shown that repeated exposure to specific messages increases familiarity and recall, increasing the likelihood of positive associations with the candidate [

63,

64]. In this study, the relationship between frequency and voting behavior was analyzed by combining content analysis with survey results, identifying correlations between repeated exposure to emotional content and voters' perceptions of candidates. This cumulative effect suggests that, even if individual publications are not engaging, repetition of key themes and emotions contributes to shaping public perception and influencing voting decisions.

Notably, the relationship between the codes "economic development" and "employment generation" was the most prevalent, registering concurrence on twelve occasions.

Furthermore, it was observed that contents based on "respect", which incorporate concepts such as: love, future, entrepreneurship, hope and above all "unity", present a high frequency of recurrence or repetition. In particular, the Avanza candidate stood out for frequently invoking the term "respect", relating it to the denunciation of gender-based violence by opponents and anonymous users.

The curved lines in

Figure 2 represent the relationship between the different variables analyzed in the study, indicating both the intensity and direction of the correlations between the factors evaluated. The thicker lines with greater curvature reflect stronger relationships, especially between economic and labor issues, underscoring the relevance of these issues in the propagandistic content disseminated in social networks. This alignment coincides with the concerns expressed by citizens, according to the survey results, where employment generation and economic development are prioritized as key aspects in the electoral content.

These findings support the research question on the impact of political propaganda on voter perceptions, demonstrating that the informational effectiveness of messages is intrinsically linked to both their relevance and their appropriate contextualization within the immediate socioeconomic realities of voters. Thus, the analysis reveals that propaganda messages not only respond to the need to persuade, but also to resonate with the priorities of the electorate, suggesting that those contents that align with the predominant concerns of citizens achieve a greater impact on public perception and voting decisions.

Moreover, the association of these issues with positive emotions and the emphasis on unity, particularly evident in Avanza's candidate speeches, illustrates how communicative strategies that evoke positive emotions and address collective concerns can significantly increase voter attention and message reception.

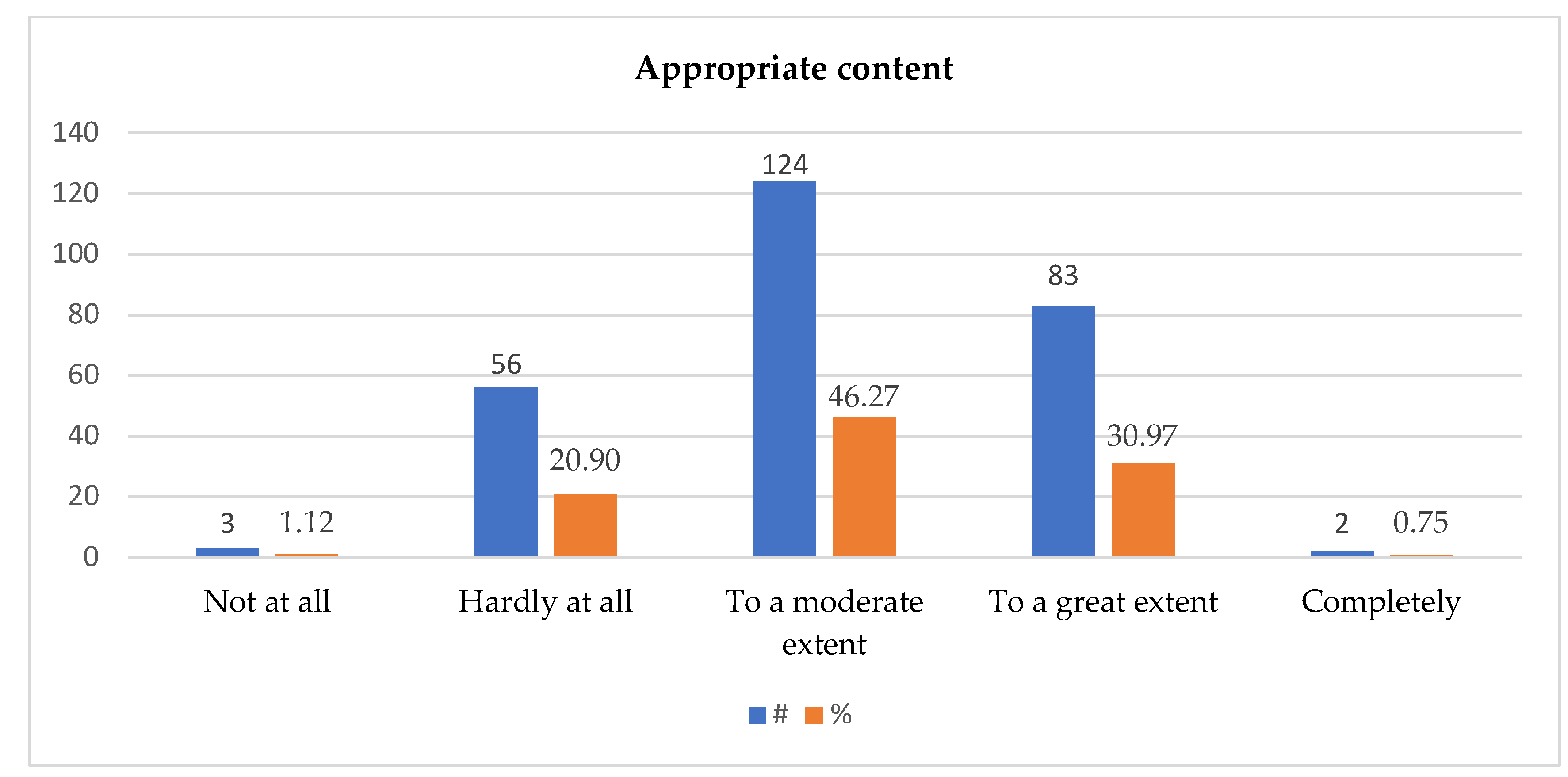

3.1.2. Factor or Theme 2: Utility Function of the Message

The analysis shows that 46.27% of respondents rated the clarity and appeal of social political propaganda messages on social networks as 'moderately' effective, while 30.97% rated them as 'very' effective. Overall, 77.24% of participants perceive these messages as clear and attractive, highlighting the importance of clarity and engagement in the reception and potential influence of these messages on voting decisions. This finding is crucial for our research question on the impact of political network communication on electoral perceptions, as illustrated in figure 3.

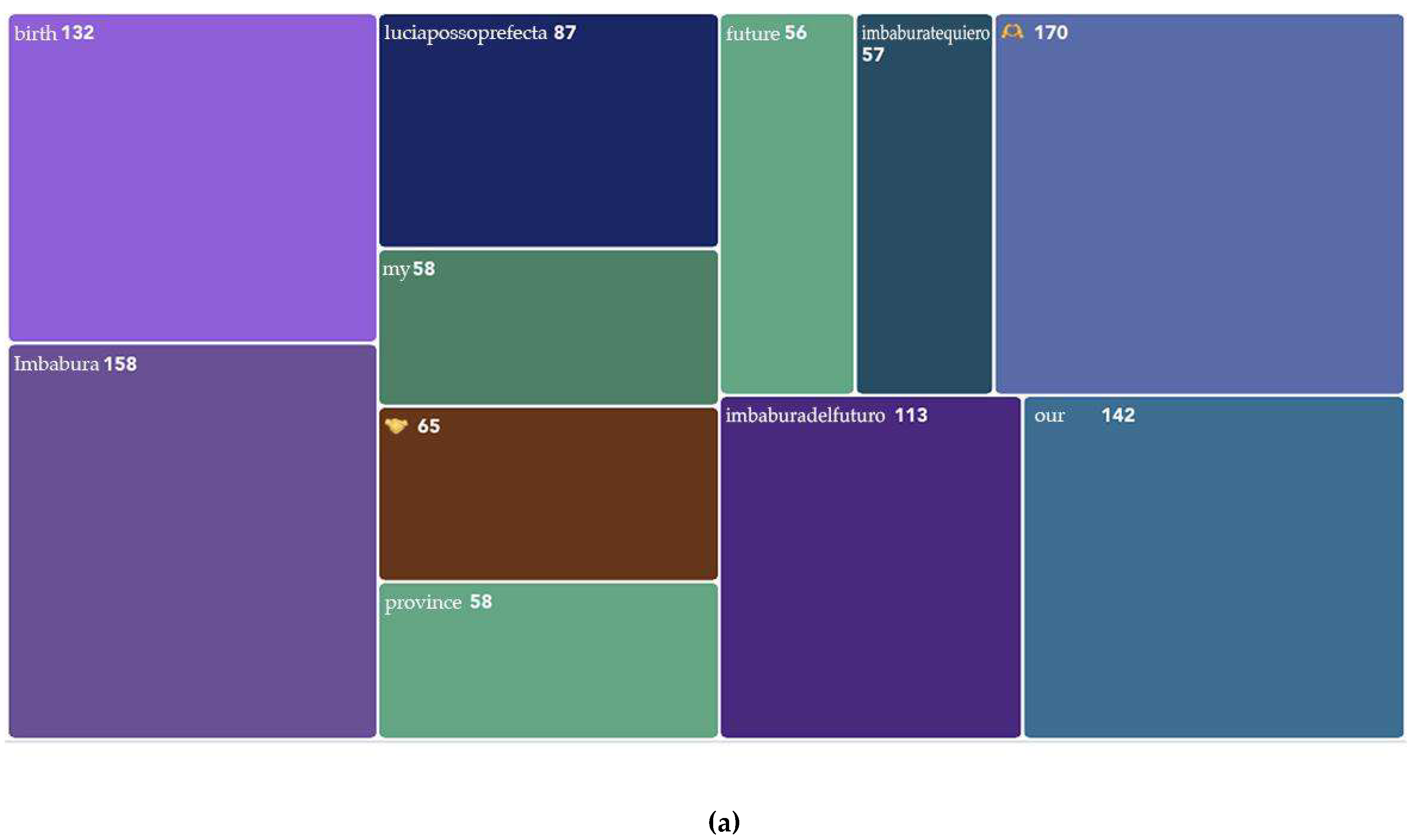

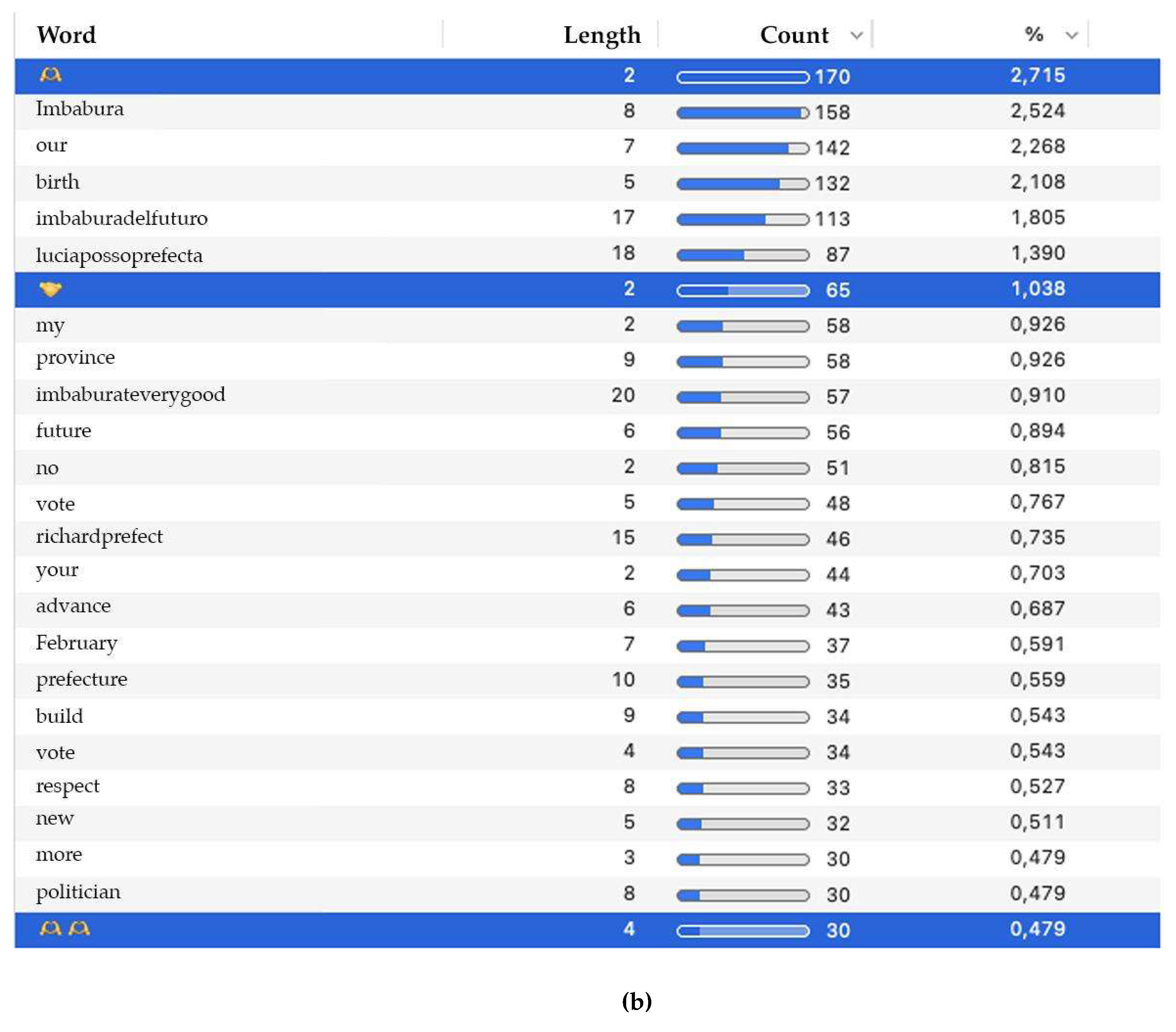

Figure 4(a) and

Figure 4(b) represent the analysis of the frequency of use of words and visual elements in digital political communication. The research reveals a remarkable transformation in the form of political communication in digital media, characterized by a simplification of language and its adaptation to digital platforms.

Figure 4(a) shows a graph of the frequency of use of words and emoticons, highlighting how candidates have integrated these visual elements to strengthen their messages. A significant finding is the predominance of the ‘heart-shaped hands’ emoticon, which appears with a frequency of 13.4% (

Figure 4(b)), surpassing even key terms such as ‘Imbabura’. On the other hand, the ‘waving hands’ emoticon registered 5.12% of use.

Figure 4(b), on the other hand, presents the amount of use of these terms and visual elements in political messages. This shift reflects not only the evolution of language in the digital age, but also a deliberate strategy to connect emotionally with the electorate. The frequent use of emoticons and visual symbols shows how candidates seek to humanize and make their messages more accessible, appealing to voters' emotions in a direct and effective way.

These figures therefore underline the central role played by simplified visual and linguistic resources in contemporary political communication.

3.2. Multimodal Analysis of Communication

The multimodal analysis highlights the coexistence of diverse communicative modes in a single process, evidencing the synergistic use of literary, graphic and iconic language in political propaganda. This multidimensional approach establishes a robust correlation between communicative functionality and message rhetoric, where clarity and interest are intimately intertwined with the content and form of communication. The strategic use of emoticons and the recurrence of keywords reinforce the message, transforming propaganda content into an effective persuasion tool.

At the strategic level, in the Avanza campaign, repetition and personalization through specific hashtags, #imbaburatequierobien or #Imbaburadelfuturo, contribute to the strengthening of its strategic narrative, favoring memorability and connection with the electorate. This communicational approach, focused on resonance and familiarity, is reflected in the electoral results, positioning Avanza in a prominent place thanks to the increase in support obtained from voters.

3.2.1. Factor or Theme 3: Impact on the Voting Decision

When assessing the impact of different elements of communication on voting decisions, the role of memes seems relevant, although complementary rather than dominant. Some 13.4% of voters indicated that memes had a significant impact on their decision. Although this percentage is relatively modest, it reflects a trend towards the use of graphic and audiovisual resources as part of a broader strategy in digital political propaganda. These results suggest that visual and interactive formats are gaining importance in digital campaigns, especially among younger voters, although they work best when integrated with other communication strategies.

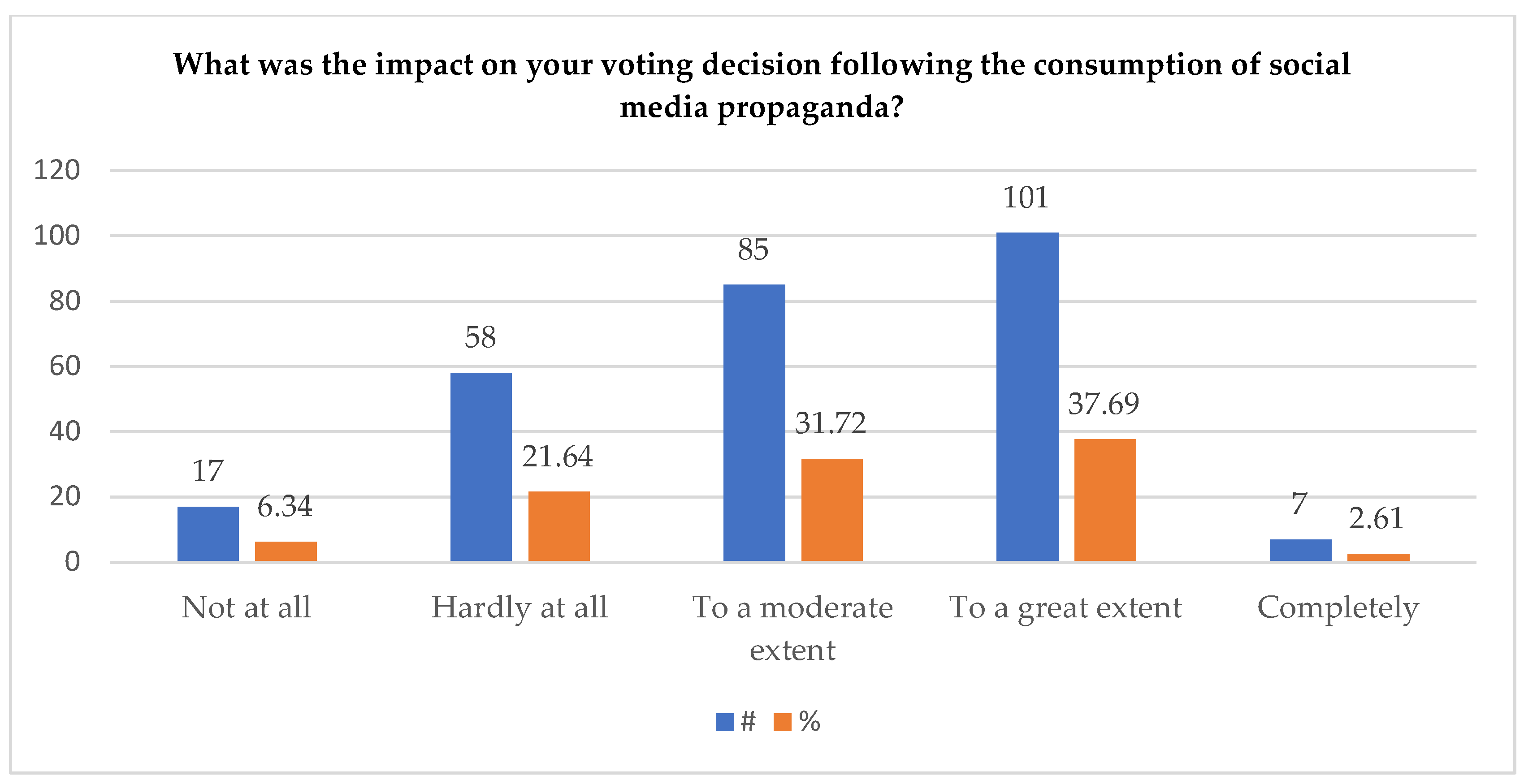

Figure 5 presents how voters perceive the overall impact of social media propaganda on their voting decisions, showing that many respondents recognize the influence of the content they consume.

Note. Evidence of the extent to which voters were influenced by the digital content they consumed during the Imbabura elections.

In addition to memes, political campaigns in digital environments rely on other complementary formats, such as news clips and interviews, which reinforce key messages. Although not specifically analyzed in this study, these tools contribute to the digital ecosystem by integrating visual resources and engaging narratives. This trend towards greater visually and emotionality on digital platforms underlines how evolving propaganda strategies can influence public opinion and electoral decisions in an increasingly digitalized environment.

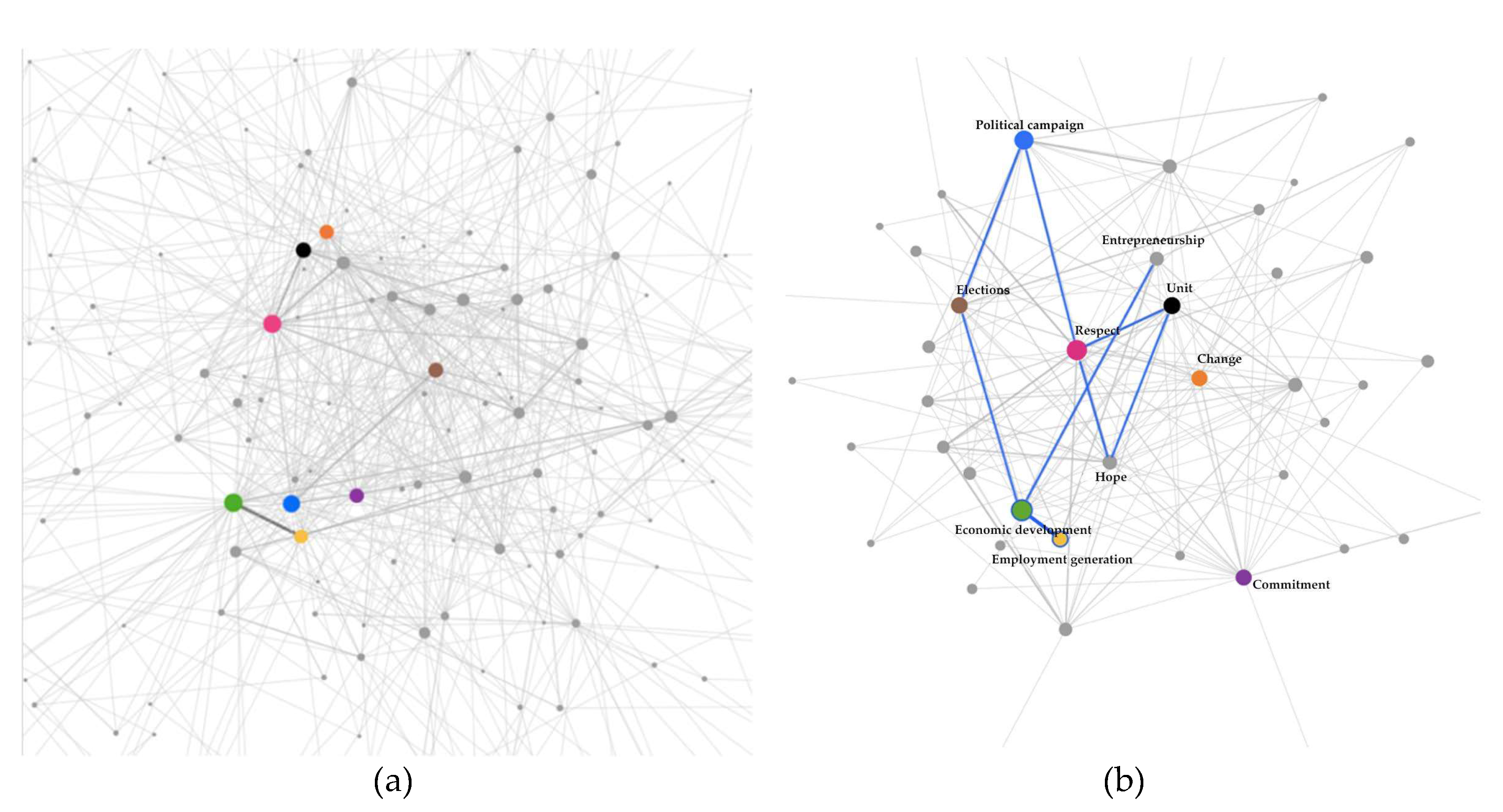

Figure 6(a) and

Figure 6(b) represent the analysis of semantic networks used in election campaign publications. This analysis reveals a diversity of discursive codes employed by the candidates to communicate their messages. However, as can be seen in

Figure 6(a), which illustrates the general semantic networks, there is a lack of effective audience segmentation and a poor definition of themes aligned with voters' expectations and needs. This suggests that better delineation of key issues and more precise segmentation could improve the effectiveness of political communication, allowing candidates to connect more effectively with their constituents.

Figure 6(b), which shows the semantic correlation between codes, highlights how certain themes are interrelated within political content. Prominent among these are terms such as ‘economic development,’ ‘job creation’ and ‘unity,’ which play a central role in the publications that resonated most with voters. These semantic correlations suggest that key issues were addressed in an interconnected manner, reinforcing the importance of thematic coherence in communication strategies.

(a) (b)

This analysis highlights that the most successful campaigns maintained remarkable consistency in their messaging, focusing on key issues such as economic development and unity, while dynamically adapting their communication strategies to influence voters' perceptions and decisions. However, the data also reveals that audience segmentation and issue definition did not fully align with voters' specific needs and expectations. This misalignment suggests an opportunity for campaigns in future elections to refine their content strategies, allowing key messages to resonate more effectively with different segments of the electorate, thereby increasing their impact among diverse groups of voters.

3.2.2. Factor or Theme 4: Role of the Message in the Decision to Vote

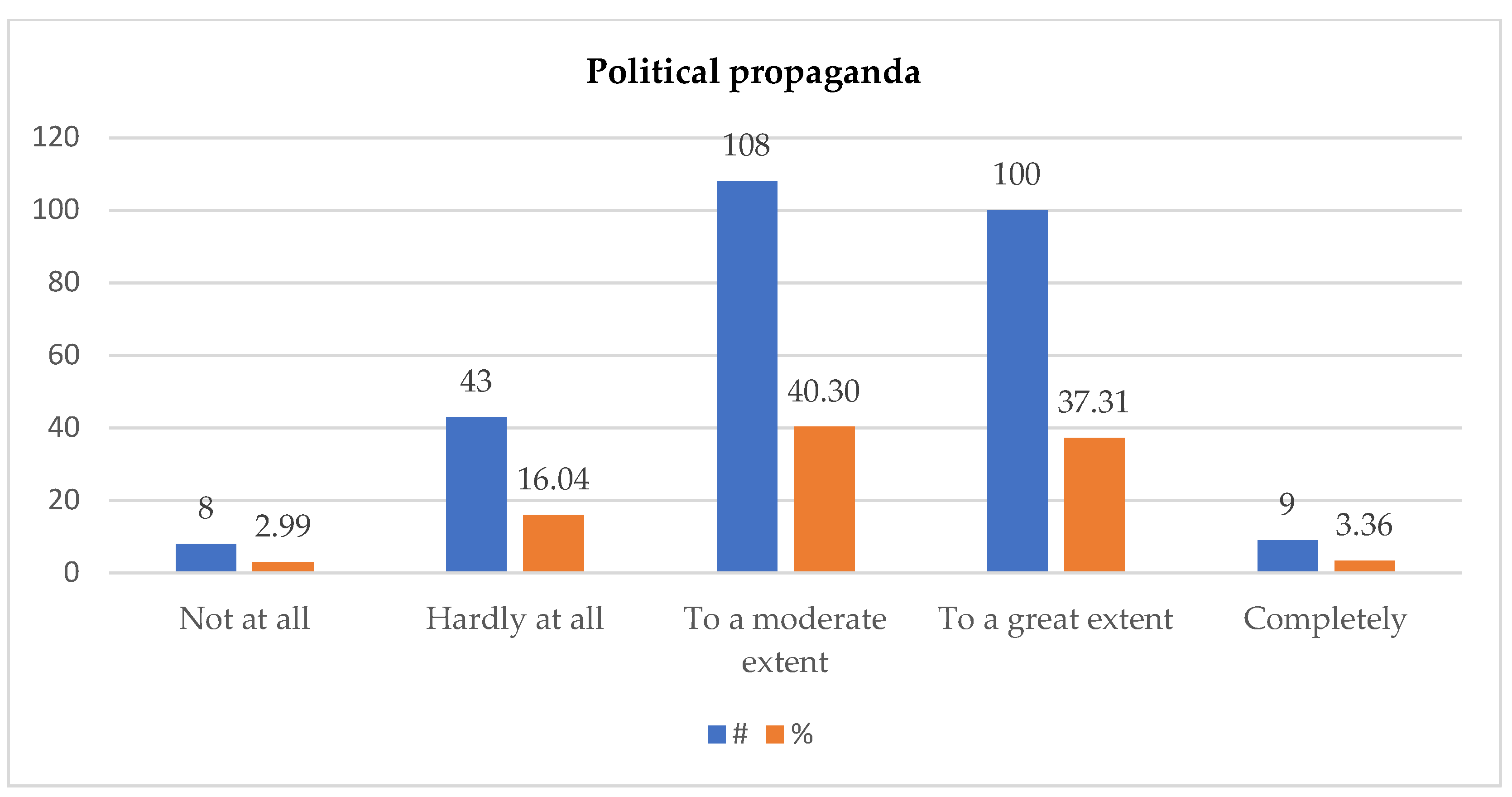

Figure 7, 40.30% of users considered the messages to be 'moderately informative' and 37.31% 'very informative', for a total of 77.61% who perceived the message as having a significant informative purpose. This data underlines the crucial role of social media as a primary channel for the dissemination of political information, particularly useful for voters who are not actively seeking detailed data on candidates and platforms. This highlights the need to assess the veracity and quality of information, which can vary considerably.

The results show marked generational differences in the reception of digital content. While Baby Boomers showed a low level of influence of digital messages on their voting behavior, 39.35% of Centennial voters said that advertising content had a strong influence on their voting decision. Similarly, 37.84% of Millennials and 39.39% of Gen Xers reported moderate to high influence. These results suggest that while over 70% of voters recognize a significant influence of advertising content, the susceptibility to such messages varies considerably between generations, with the notable exception of Baby Boomers.

Figure 8 represents a sentiment analysis of the messages, which highlights the relationship between perception and acceptance of the content as a function of the emotional character of the messages, whether positive, neutral or negative. The data presented suggest that, despite a generalized rejection of politics, messages that evoke positive emotions, such as hope and unity, tend to be more effective in influencing voters' perceptions and electoral decisions.

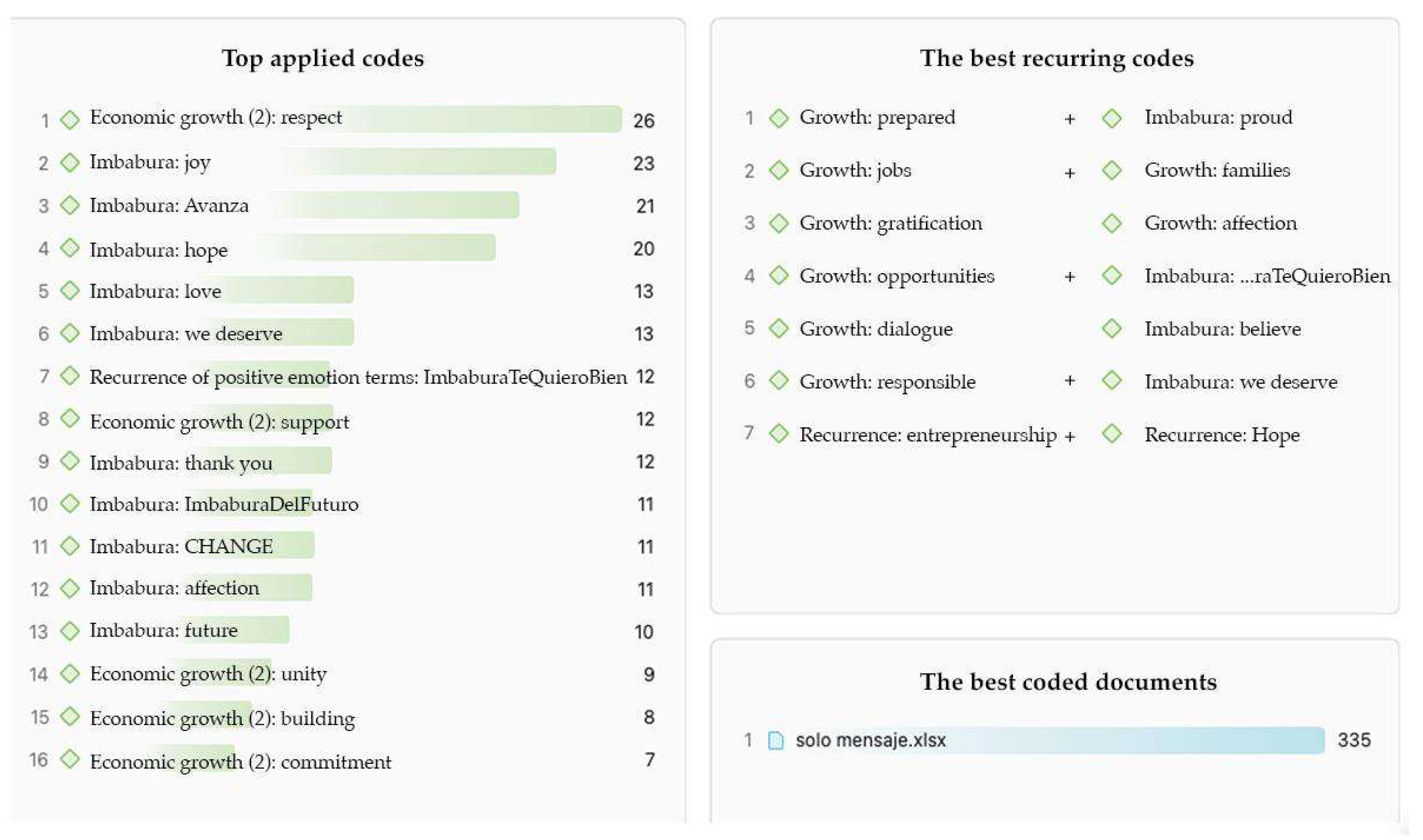

As for the label ‘economic growth (2): respect’ with 26 occurrences, this indicates that the term ‘economic growth’ has been coded with a sub-theme or dimension related to respect, meaning that on 26 occasions, economic growth was discussed or mentioned in a context where respect was a relevant theme. This label and the number of times it appears reflect how the content of the messages addresses the importance of respect in relation to economic growth, suggesting that this is a theme that resonates strongly with the audience.

Similarly, the figure also shows other key terms, such as ‘Imbabura: joy’ and ‘Imbabura: hope’, which represent important emotional and geographical themes in the communication. These terms reinforce the candidates' strategy of using messages that appeal to positive emotions to generate greater acceptance among voters.

In summary,

Figure 8 highlights how emotional connection in messages plays a key role in influencing voters, highlighting the importance of a strategic approach to content that appeals to positive sentiments to enhance perception and increase the effectiveness of political communication.

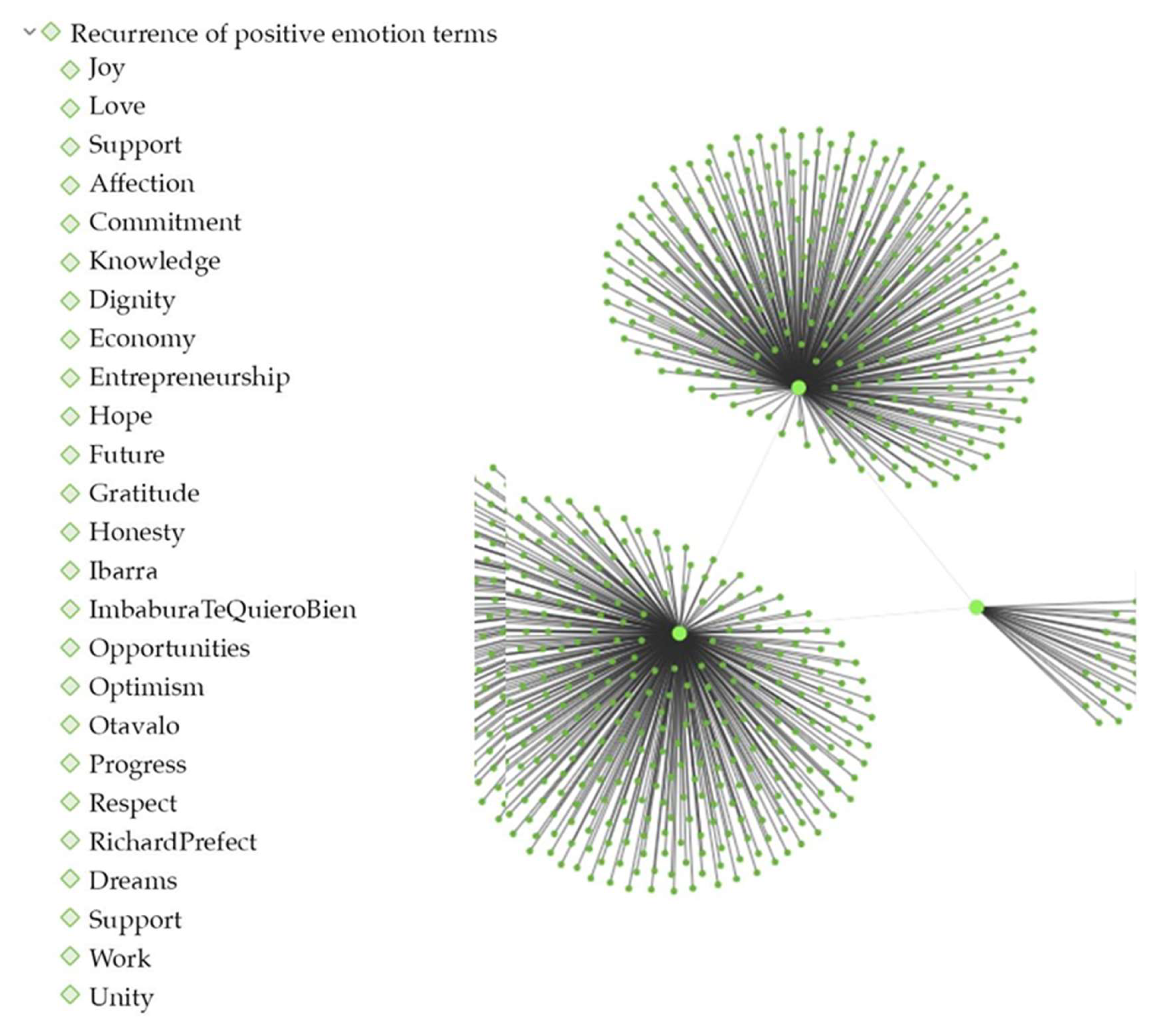

Figure 9 shows the results of the semantic network analysis that identifies the terms related to positive emotions in the messages of the most successful candidates during the election campaign. Each node in the figure represents a key term such as ‘hope’, ‘unity’, ‘optimism’ and ‘progress’, while the lines connecting these nodes reflect the frequency with which these terms co-occur in the messages. This analysis highlights how the most successful candidates managed to create a coherent content focused on issues of high relevance to the electorate, such as economic development and job creation.

The results indicate that messages appealing to these emotional concepts were strategic, as they projected an image of optimism, unification and progress. The recurrence of terms such as ‘joy’, ‘future’ and ‘opportunities’ shows how candidates used positive emotions to strengthen the emotional connection with voters. This strategy not only helped build a favorable political image, but also resonated deeply with citizens' expectations and needs, which contributed to electoral success.

In sum,

Figure 9 illustrates how the use of emotionally charged and thematically coherent messages played a key role in constructing a political content that was attractive and convincing to voters.

4. Discussion

The comprehensive analysis of the propaganda content during Ecuador's 2023 sectional elections revealed patterns, strategies and shortcomings in the communication approaches employed. Messages that incorporated elements of voters' individual and collective contexts, presented through multimodal rhetorical resources (linguistic, graphic and audiovisual), significantly influenced users' perceptions and voting decisions, in line with Bode et al. [

65] theory on the need to authentically connect with voters as a central pillar of campaigns, regardless of the evolution of tools and platforms.

While Kruschinski et al. [

66] found similarities between digital and traditional advertising strategies, this study found a lack of a dedicated strategic approach to fully leverage the benefits of digital. This contrasts with the findings of Boulianne et al. [

67] and Cheonsoo et al. [

41], who suggest that multimodal content can drive higher levels of interaction by triggering emotions and cognitions in users, a dynamic that may explain the prominence of memes and informal content despite low interaction with official accounts.

In contrast to Bandy et al. [

68] and Hidalgo et al. [

69], who highlight the role of Facebook as a fundamental space for modern political communication, this study found a dissonance between the reported influence of content and interaction metrics, calling into question the actual effectiveness of social networks in translating digital support into tangible votes.

Consistent with Calvo et al. [

70], Analysis of the data shows significant variation in message reception between generations, with higher rates among centenarians and millennials. This reflects how differences in media preferences and technological skills can influence the reception of election content, highlighting the importance of considering these variations when assessing the impact of digital content on different demographic segments. In addition, the Facebook advertising model discussed by Brito [

23] highlights how campaigns can segment and personalize messages to increase their impact, although the results raise questions about the actual effectiveness of this strategy.

In contrast to the findings of Broeck et al. [

71] on the perceived intrusiveness of propagandistic content, this study found no significant evidence of this factor, although it is acknowledged that the influence of digital media in politics may have been overestimated or that there are dynamics in digital interaction that have yet to be fully understood.

Finally, the findings of this study are consistent with Griffiths' [

72] findings that political communication in the digital age transcends the mere dissemination of content and becomes a vital medium for social connection and community building in real time or asynchronously through the mediated interaction and connectivity offered by these digital platforms.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the influence of digital propaganda content disseminated on Facebook during the 2023 Imbabura sectional elections, with the objective of understanding how this content impacts both voters' perceptions and their voting decisions. Based on an analysis of publications and voter perception, the results reveal that the effectiveness of digital propaganda cannot be explained solely by traditional demographic variables, but depends on contextual and individual factors that affect the reception and understanding of messages.

One of the main findings of the study is that the impact of digital content varies between generations. The results show that millennials and centennials respond with greater receptivity to visual and informal content, such as memes, which, although not traditional sources of political information, play a relevant role in reinforcing the campaign narrative. However, the impact of these resources is more significant when they are integrated into communication strategies that combine frequency of exposure and messages coherent with the electorate's expectations.

One of the main conclusions of the study was the importance of visual and multimodal resources, such as memes and images, especially in attracting young voters. Although only 13.4% of respondents indicated that memes had had a significant impact on their voting decision, this result reflects a complementary trend towards the use of visual and interactive formats in campaigns. The authors consider that these resources, while not determinative on their own, have a relevant role to play when integrated into broader strategies that combine information with emotional elements. This suggests that future campaigns can improve their impact by adopting a more strategic approach, where visual content reinforces core narratives rather than acting in isolation.

Content segmentation emerged as a critical aspect of the analysis. The data revealed that campaigns often failed to align their narratives with the needs and expectations of the electorate, which presents an opportunity for improvement. Future campaigns should prioritize greater personalization of messages, tailoring content to reflect the specific concerns of different voter segments to optimize their effectiveness. The thematic dispersion identified in the semantic networks suggests that campaigns could improve their impact by focusing more on voters' priorities, ensuring that key messages resonate effectively across diverse groups of the electorate.

Moreover, the study highlights that the absence of a clear communication strategy reduces the effectiveness of social platforms. Without messages of value, these platforms become passive broadcast channels, similar to broadcast television, rather than spaces for meaningful interaction. This highlights the need for social media campaigns to promote active and reflective communication, capable of engaging the electorate and encouraging more critical and conscious participation in electoral processes.

In summary, the study concludes that content strategies in digital campaigns must evolve towards more segmented and strategic approaches. Future campaigns should focus not only on the dissemination of information, but on the creation of valuable content that generates a greater emotional connection and active participation on the part of the electorate. In addition, it is suggested that future research should implement methodologies that allow for more accurate tracking of digital content consumption, to better understand its direct influence on voting decisions.

6. Limitations and Future Lines of Research

The research conducted in Imbabura, while revealing, has limitations inherent to its case study approach, which may restrict the generalizability of its findings at the national level. The political, cultural and social diversity in the different regions of Ecuador suggests that the dynamics of digital propaganda and its impact on voting decisions may vary significantly. To gain a more holistic and representative perspective of national trends, it would be beneficial to expand the study to include different urban and rural contexts across the country.

A limitation of the study is that, although general perceptions about the impact of digital content were captured, no individual tracking of the consumption of each content piece was conducted. This approach focused more on the general exposure and perception of the electorate, providing a broad perspective on the impact of digital propaganda on voting decisions. Future research would benefit from methodologies that allow more precise tracking of individual digital content consumption and its direct influence on electoral behavior.

Future research could delve deeper into the interaction between digital content and factors such as voters' media literacy and trust in social networks. It is also crucial to include informal, personal and anonymous content in the analysis, as these elements, as observed with memes, can be decisive in the voting decision and offer new insights into understanding political persuasion in the digital realm. Furthermore, continued exploration of how to use digital political propaganda effectively to foster an interactive and conscious dialogue with voters is required to improve future political campaign strategies. It is vital to strengthen a responsible political culture in Ecuador, including educational and awareness-raising initiatives.

Finally, the role of audiovisual communication in politics, along with the contributions of local graphic design in the face of foreign influence, should be further investigated to contribute to the strengthening of the disciplines and industries involved. These lines of research can improve the quality of political communication and promote more informed and engaged citizen participation.

Supplementary Materials

The supplementary material is available on Zenodo under the Creative Commons license, with the DOI.

Table 1: Result of forms surveys.pdf; Figure S1: Segmented analysis.xlsx; Figure S2: Co-occurrence of terms.xlsx; Figure S3: Segmented analysis.xlsx; Figure S4 (a and b): List of AtlasTi codes.xlsx; Figure S5: Segmented analysis.xlsx; Figure S6: Co-occurrence of terms.xlsx; Figure S7: Segmented analysis.xlsx; Figure S9: Co-occurrence of terms.xlsx.

Informed Consent Statement

Verbal informed consent: Informed consent was obtained verbally before participation. The consent was audio-recorded in the presence of an independent witness.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in ZENODO at DOI.

Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. “The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”.

References

- Liçenji, L. The Role of Social Media on Electoral Strategy: An Examination of the 2023 Municipal Elections in Tirana, Albania. Acad. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 2023, 12, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, E.; Robison, J. Like, Post, and Distrust? How Social Media Use Affects Trust in Government. Political Communication 2020, 37, 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamirano-Benítez, E.; et al. El impacto de los medios digitales en la política ecuatoriana. Rev. Lat. Comun. Soc. 2022, 74, 213–232. [Google Scholar]

- Del Alcázar, J. Estado digital Ecuador 2024. Mentinno Consultores, February 2024. https://www.mentinno.com/acceso-estado-digital-ecuador-2024/.

- Tella, A.; Adah, M. Digital political communication and voter engagement: Theoretical frameworks and practical implications. Int. J. Polit. Stud. 2023, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Badillo, J. La sociedad de la desinformación: propaganda, «fake news» y la nueva geopolítica de la información [working paper]. Real Instituto Elcano, 2019. https://www.realinstitutoelcano.

- Soria Alonso, S.; Gil-Torres, A. La burbuja de filtros en España. Una comprobación empírica en Facebook e Instagram. Observatorio (OBS) 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBC Mundo. 4 formas en que Facebook ha cambiado nuestro mundo. https://www.bbc.com/mundo/articles/cp07y918qn5o (accessed February 2, 2024).

- Cerná, M.; Borkovcová, A. Acceptance of Social Media for Study Purposes—A Longitudinal Case Study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, N.; Cohen, S.; Scarles, C. The power of social media storytelling in destination branding. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 8, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, J. En las antípodas de la democracia deliberativa: la propaganda populista en la era digital. DILEMATA 2022, 38, 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Akram, M.; Nasar, A.; Arshad-Ayaz, A. A bibliometric analysis of disinformation through social media. Online J. Commun. Media Technol. 2022, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, E.; Chang, H.; Chen, E.; Murić, G.; Patel, J. Characterizing social media manipulation in the 2020 U.S. presidential election. First Monday 2020, 25, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, M.; Megan, T.; Joshua, A.; Nagler, J. To Moderate, Or Not to Moderate: Strategic Domain Sharing by Congressional Campaigns. SSRN 2022, 10, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A. R. N.; Vaccari, C.; Chadwick, A. Russian meddling in U.S. elections: How news of disinformation’s impact can affect trust in electoral outcomes and satisfaction with democracy. Mass Commun. Soc. 2022, 25, 786–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, F. B.; Gruzd, A.; Mai, P. Falling for Russian propaganda: Understanding the factors that contribute to belief in pro-Kremlin disinformation on social media. Soc. Media Soc. 2023, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Balapal, N.; Ankem, A.; Shyamsundar, S.; Balaji, A.; Kannikal, J.; Bruno, M.; He, S.; Chong, P. Primary Perspectives in Meme Utilization as a Digital Driver for Medical Community Engagement and Education Mobilization: Pre-Post Study. JMIR Hum. Factors 2023, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magallón-Rosa, R. De las fake news a la polarización digital. Una década de hibridación de desinformación y propaganda. Rev. Más Poder Local 2022, 50, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilardi, F.; Gessler, T.; Kubli, M.; Müller, S. Social Media and Political Agenda Setting. Polit. Commun. 2021, 39, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyekye-Jandoh, M.; Ahmed, A. H. Ghana’s Democracy and the Digital Public Sphere: Some Pertinent Issues. Contemp. J. Afr. Stud. 2023, 10, 139–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Alcázar, J. Estado digital Ecuador 2023. Mentinno Consultores, June 2023. https://www.mentinno.com/aqui-esta-tu-acceso-al-informe-estado-digital-ecuador-junio-2023/.

- Brito, K.; Adeodato, P. Predicting Brazilian and U.S. Elections with Machine Learning and Social Media Data. In Int. Joint Conf. Neural Netw. (IJCNN), 2020, 1, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Brito, K.; Leitão Adeodato, P. Machine Learning for Predicting Elections in Latin America Based on Social Media Engagement and Polls. Gov. Inf. Q. 2023, 40, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreiss, D.; McGregor, S. C. The “Arbiters of What Our Voters See”: Facebook and Google’s Struggle with Policy, Process, and Enforcement around Political Advertising. Polit. Commun. 2019, 36, 499–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haenschen, K. Social Pressure on Social Media: Using Facebook Status Updates to Increase Voter Turnout. J. Commun. 2016, 66, 542–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neely, S. R. Politically Motivated Avoidance in Social Networks: A Study of Facebook and the 2020 Presidential Election. Soc. Media Soc. 2021, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guess, A.; Barberá, P.; Munzert, S.; Yang, J. The Consequences of Online Partisan Media. PNAS 2021, 118, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, K.; Pedersen, R. Campaigns Matter: How Voters Become Knowledgeable and Efficacious During Election Campaigns. Polit. Commun. 2014, 31, 303–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaqub, U.; Chun, S.; Atluri, V.; Vaidya, J. Analysis of Political Discourse on Twitter in the Context of the 2016 US Presidential Elections. Gov. Inf. Q. 2017, 34, 613–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán Barba, J.; Nieto, S. La política en el siglo XXI. Arte, mito o ciencia, 4th ed.; Debate: 2017.

- Auter, Z. J.; Fine, J. A. Negative Campaigning in the Social Media Age: Attack Advertising on Facebook. Polit. Behav. 2016, 38, 999–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, M.; Sen, A.; Yildirim, P. Social Media and Political Contributions: The Impact of New Technology on Political Competition. ERN: Technology (Topic) 2020, 1, 1–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dommett, K. Data-Driven Political Campaigns in Practice: Understanding and Regulating Diverse Data Infrastructures. Internet Policy Review 2020, 9, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsichla, E.; Lappas, G.; Triantafillidou, A.; Kleftodimos, A. Gender Differences in Politicians’ Facebook Campaigns: Campaign Practices, Campaign Issues and Voter Engagement. New Media Soc. 2021, 25, 2918–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. H.; Johnson, K. T. Twitter Taunts and Tirades: Negative Campaigning in the Age of Trump. Polit. Sci. Polit. 2016, 49, 748–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Dzyabura, D.; Mizik, N. Visual Listening In: Extracting Brand Image Portrayed on Social Media. Mark. Sci. 2020, 39, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, K.; Filho, R.; Adeodato, P. A Systematic Review of Predicting Elections Based on Social Media Data: Research Challenges and Future Directions. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2021, 8, 819–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kietzmann, J.; Hermkens, K.; McCarthy, I.; Silvestre, B. Social Media? Get Serious! Understanding the Functional Building Blocks of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 2011, 54, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold-Murray, K. Diálogo construido de forma multimodal en anuncios de campaña política. J. Pragmat. 2021, 173, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drăgan, N.; Fârte, G. The Multimodal Construction of Political Personae through the Strategic Management of Semiotic Resources of Emotion Expression. Soc. Semiot. 2022, 1, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheonsoo, K.; Sung-Un, Y. Like, Comment, and Share on Facebook: How Each Behavior Differs from the Other. Public Relat. Rev. 2017, 43, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L. Toward Multimodal Corpus Pragmatics: Rationale, Case, and Agenda. Digit. Scholarsh. Humanit. 2021, 36, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, M.; Hessler, C.; Asnani, P.; Riani, K.; Abouelenien, M. Multimodal Political Deception Detection. IEEE MultiMedia 2021, 28, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.; Ebrahim, H. Visual Propaganda on Facebook: A Comparative Analysis of Syrian Conflicts. Media, War Confl. 2016, 9, 227–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchinetti, R. News Discourse and the Dissemination of Knowledge and Perspective: From Print and Monomodal to Digital and Multisemiotic. J. Pragmat. 2021, 175, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervais, B. T.; Evans, H. K.; Russell, A. Fear and Loathing on Twitter: Exploring Negative Rhetoric in Tweets During the 2018 Midterm Election. In Foreman, S.; Godwin, M.; Wilson, W., Eds. The Roads to Congress 2018; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Grüning, D.; Schubert, T. Emotional Campaigning in Politics: Being Moved and Anger in Political Ads Motivate to Support Candidate and Party. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ope-Davies (Opeibi), T.; Shodipe, M. A Multimodal Discourse Study of Selected COVID-19 Online Public Health Campaign Texts in Nigeria. Discourse Soc. 2023, 34, 96–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schubert, C. Multimodal Cohesion in Persuasive Discourse: A Case Study of Televised Campaign Advertisements in the 2020 US Presidential Election. Discourse, Context Media 2021, 43, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, R.; Fariss, C.; Jones, J.; Kramer, A.; Marlow, C.; Settle, J.; Fowler, J. A 61-Million-Person Experiment in Social Influence and Political Mobilization. Nature 2012, 489, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M. Social Networks Influence Consistent Choice. J. Choice Model. 2015, 17, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.; Bond, R.; Bakshy, E.; Eckles, D.; Fowler, J. Social Influence and Political Mobilization: Further Evidence from a Randomized Experiment in the 2012 U.S. Presidential Election. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt-Beck, R.; Mackenrodt, C. Social Networks and Mass Media as Mobilizers and Demobilizers: A Study of Turnout at a German Local Election. Elect. Stud. 2010, 29, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J. Social Networks as a Shortcut to Correct Voting. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 2011, 55, 753–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolzern, P.; Colaneri, P.; Nicolao, G. Effect of Social Influence on a Two-Party Election: A Markovian Multiagent Model. IEEE Trans. Control Netw. Syst. 2022, 9, 1056–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravanilla, N.; Davidson, M.; Hicken, A. Voting in Clientelistic Social Networks: Evidence from the Philippines. Comp. Polit. Stud. 2022, 55, 1663–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bgharashvili, N. The Importance of Social Networks in the Pre-Election Period. Econ. 2022, 105, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh Jodha, A. Social Media Replacing the Party Manifesto as the Key Factor in Deciding Election Outcomes. Ijraset J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2022, 10, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Yu, H.; Yu, T. Literature Review on the Influence of Social Networks. SHS Web Conf. 2023, 153, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heseltine, M. Asymmetric Polarization in Online Media Engagement in the United States Congress. Int. J. Press/Polit. 2023, 1, 1-27. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. Facebook News Sharing, Hostile Perceptions of News Content, and Political Participation. Soc. Media Soc. 2021, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.; Milkman, K. L. What Makes Online Content Viral? J. Mark. Res. 2012, 49, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajonc, R. Mere Exposure: A Gateway to the Subliminal. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 2001, 10, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, S.; Simon, A. F. News Coverage of the Gulf Crisis and Public Opinion: A Study of Agenda-Setting, Priming, and Framing. Public Opinion Quarterly, 2020, 77, 641-665. [CrossRef]

- Bode, L.; Lassen, D. S.; Kim, Y. M.; Shah, D. V.; Fowler, E. F.; Ridout, T.; Franz, M. Coherent Campaigns? Campaign Broadcast and Social Messaging. Online Inf. Rev. 2016, 40, 580–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruschinski, S.; Bene, M. In Varietate Concordia?! Political Parties’ Digital Political Marketing in the 2019 European Parliament Election Campaign. Eur. Union Polit. 2021, 23, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulianne, S.; Larsson, A. O. Engagement with Candidate Posts on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook During the 2019 Election. New Media Soc. 2023, 25, 119–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandy, J.; Diakopoulos, N. Facebook’s News Feed Algorithm and the 2020 US Election. Soc. Media Soc. 2023, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo Chica, A.; Cedeño Moreira, C. Comunicación Política en Redes Sociales Durante la Segunda Vuelta Electoral de Ecuador, Año 2021: Análisis del Uso de la Red Social Facebook. ReHuSo 2022, 7, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, D.; Cano-Orón, L.; Baviera, T. Global Spaces for Local Politics: An Exploratory Analysis of Facebook Ads in Spanish Election Campaigns. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broeck, E. V. den; Poels, K.; Walrave, M. A Factorial Survey Study on the Influence of Advertising Place and the Use of Personal Data on User Acceptance of Facebook Ads. Am. Behav. Sci. 2017, 61, 653–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, L. E. Dancing Through Social Distance: Connectivity and Creativity in the Online Space. Body Space Technol. 2023, 22, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).