Submitted:

24 October 2024

Posted:

29 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

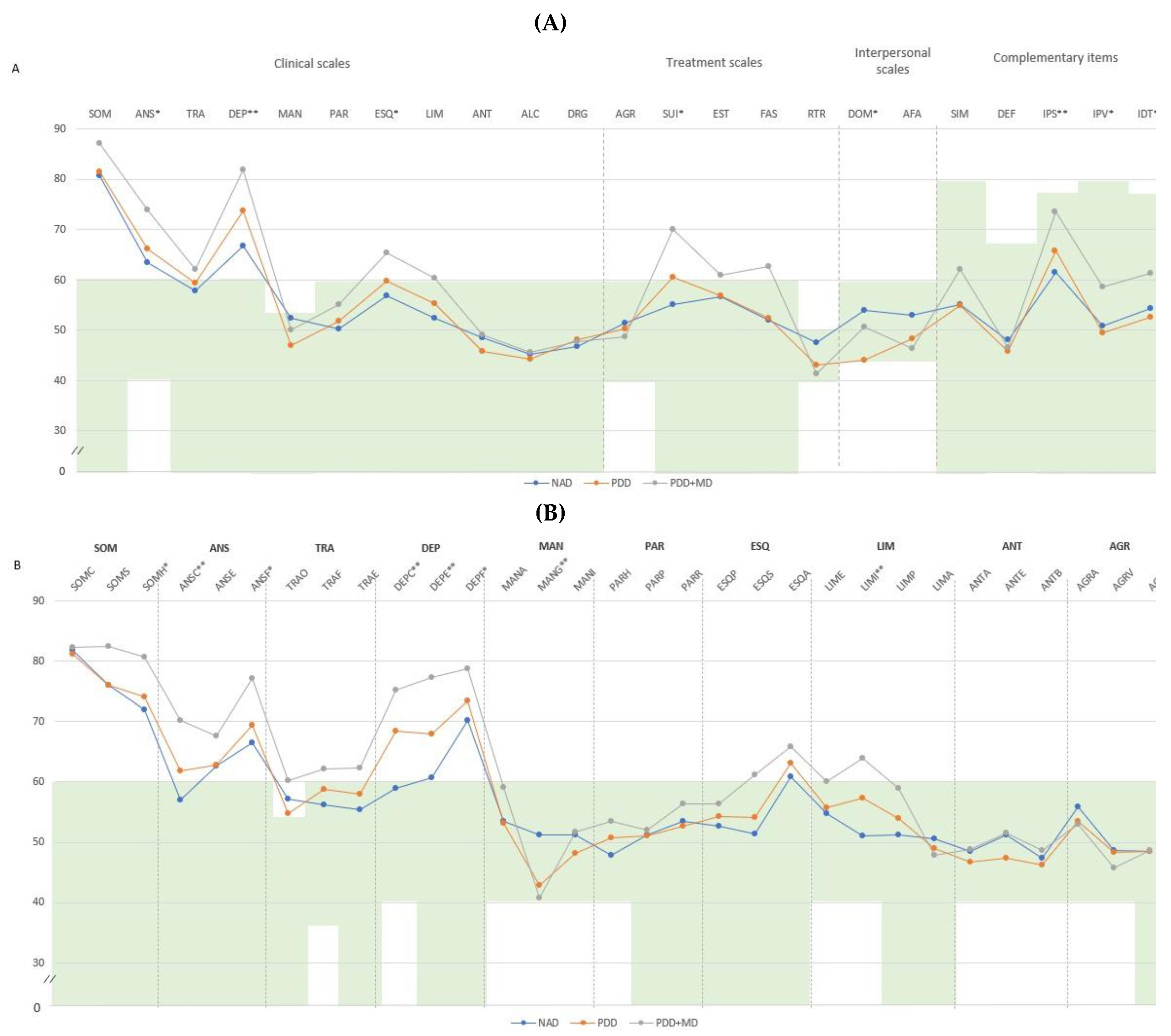

Background. Fibromyalgia (FM) is a complex condition marked by increased pain sensitivity and central sensitization. Studies often explore the link between FM and depressive-anxiety disorders, but few focus on dysthymia or persistent depressive disorder (PDD), which can be more disabling than major depression (MD). Objective. To identify clinical scales and subscales of the Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI) that effectively describe and differentiate the psychological profile of PDD, with or without comorbid MD, in FM patients with PDD previously dimensionally classified by the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory III (MCMI-III). Method. An observational, cross-sectional study was conducted with 66 women (mean age 49.18, SD=8.09) from Hospital del Mar. The PAI, the MCMI-III, and Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) were used to assess the sample. Results. The PAI showed strong discriminative ability in detecting PDD, characterized by high scores in cognitive and emotional depression, and low scores in identity alteration, dominance, and grandeur. High scores in cognitive, emotional, and physiological depression, identity alteration, cognitive anxiety, and suicidal ideation, along with low scores in dominance and grandeur, were needed to detect MD with PDD. Discriminant analysis could differentiate 69.6-73.9% of the PDD group and 84.6% of the PDD+MD group. Group comparisons showed that 72.2% of patients with an affective disorder by PAI were correctly classified in the MCMI-III affective disorder group, and 70% without affective disorder were correctly classified. Conclusions. The PAI effectively identifies PDD in FM patients and detects concurrent MD episodes, aiding in better prognostic and therapeutic guidance.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Participants

2.3. Study Design and Procedure

2.4. Instruments

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Acknowledgments

References

- Thieme K, Mathys M, Turk DC. Evidenced-Based Guidelines on the Treatment of Fibromyalgia Patients: Are They Consistent and If Not, Why Not? Have Effective Psychological Treatments Been Overlooked? J Pain. 2017;18(7):747-756. [CrossRef]

- Ablin JN, Buskila D, Van Houdenhove B, Luyten P, Atzeni F, Sarzi-Puttini P. Is fibromyalgia a discrete entity? Autoimmun Rev. 2012;11(8):585–8. [CrossRef]

- Arnold LM, Gebke KB, Choy EH. Fibromyalgia: management strategies for primary care providers. Int J Clin Pract. 2016;70(2):99–112. [CrossRef]

- López-Solà M, Woo CW, Pujol J, Deus J, Harrison BJ, Monfort J, Wager TD. Towards a neurophysiological signature for fibromyalgia. Pain. 2017;158(1):34-47. [CrossRef]

- Pujol J, Macià D, Garcia-Fontanals A, Blanco-Hinojo L, López-Solà M, Garcia-Blanco S, Poca-Dias V, Harrison BJ, Contreras-Rodríguez O, Monfort J, Garcia-Fructuoso F, Deus J. The contribution of sensory system functional connectivity reduction to clinical pain in fibromyalgia. Pain. 2014;155(8):1492-1503. [CrossRef]

- Sluka KA, Clauw DJ. Neurobiology of fibromyalgia and chronic widespread pain. Neuroscience. 2016;338:114-129. [CrossRef]

- Arnold LM, Hudson JI, Hess EV, Ware AE, Fritz DA, Auchenbach MB, et al. Family study of fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(3):944–52. [CrossRef]

- Duque L, Fricchione G. Fibromyalgia and its new lessons for neuropsychiatry. Med Sci Monit Basic Res. 2019;25:169–78. [CrossRef]

- Galvez-Sánchez CM, Duschek S, Reyes Del Paso GA. Psychological impact of fibromyalgia: current perspectives. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2019;12:117–27. [CrossRef]

- Kleykamp BA, Ferguson MC, McNicol E, Bixho I, Arnold LM, Edwards RR, et al. The prevalence of comorbid chronic pain conditions among patients with temporomandibular disorders: A systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2021;51(1):166–74. [CrossRef]

- Hirsch JK, Altier HR, Offenbächer M, Toussaint L, Kohls N, Sirois FM. Positive psychological factors and impairment in rheumatic and musculoskeletal disease: Do psychopathology and sleep quality explain the linkage? Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2021;73(1):55-64. [CrossRef]

- Martínez MP, Sánchez AI, Cáliz R, Miró E. Psychopathology as a Moderator of the Relationship Between Physical Symptoms and Impairment in Fibromyalgia Patients. Psicothema, 2021;33(2):214-221. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Fontanals A, Portell M, García-Blanco S, Poca-Dias V, García-Fructuoso F, López-Ruiz M, et al. Vulnerability to psychopathology and dimensions of personality in patients with fibromyalgia. Clin J Pain. 2017;33(11):991-997. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Valera-Calero JA, Arendt-Nielsen L, Martín-Guerrero JD, Cigarán-Méndez M, Navarro-Pardo E, et al. Clustering analysis identifies two subgroups of women with fibromyalgia with different psychological, cognitive, health-related, and physical features but similar widespread pressure pain sensitivity. Pain Med. 2023;24(7):881–9. [CrossRef]

- González B, Novo R, Ferreira AS. Fibromyalgia: heterogeneity in personality and psychopathology and its implications. Psychol Health Med. 2020;25(6):703–9. [CrossRef]

- González B, Novo R, Peres R. Personality and psychopathology heterogeneity in MMPI-2 and health-related features in fibromyalgia patients. Scand J Psychol. 2021;62(2):203–10. [CrossRef]

- González B, Novo R, Peres R, Baptista T. Fibromyalgia and rheumatoid arthritis: Personality and psychopathology differences from the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2. Pers Individ Dif. 2019;142:260–9. [CrossRef]

- López-Ruíz M, Losilla JM, Monfort J, Portell M, Gutiérrez T, Poca V, García-Fructuoso F, Llorente J, García-Fontanals A, Deus J. Central sensitization in knee osteoarthritis and fibromyalgia: beyonds depression and anxiety. PLoS One, 2019;14(12): e0225836. [CrossRef]

- Henao-Pérez M, López-Medina DC, Arboleda A, Monsalve SB, Zea JA. Patients with fibromyalgia, depression, and/or anxiety and sex differences. Am J Mens Health. 2022;16(4):15579883221110351. [CrossRef]

- Janssens KA, Zijlema WL, Joustra ML, Rosmalen JG. Mood and Anxiety Disorders in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Fibromyalgia, and Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Results From the LifeLines Cohort Study. Psychosom Med. 2015;77(4):449–57. [CrossRef]

- Brooks L, Johnson-Greeme D, Lattie E, Ference T. The relationship between performance on neuropsychological symptom validity testing and the MCMI-III in patients with fibromyalgia. Clin Neuropsychol. 2012;26(5):816–31. [CrossRef]

- Berkol TD, Balcioglu YH, Kirlioglu SS, Erensoy H, Vural M. Dissociative features of fibromyalgia syndrome. Neurosciences (Riyadh). 2017;22(3):198–204. [CrossRef]

- Gupta MA, Moldofsky H. Dysthymic disorder and rheumatic pain modulation disorder (fibrositis syndrome): a comparison of symptoms and sleep physiology. Can J Psychiatry. 1986;31(7):608–16. [CrossRef]

- Schramm E, Klein DN, Elsaesser M, Furukawa TA, Domschke K. Review of dysthymia and persistent depressive disorder: history, correlates, and clinical implications. Lance Psychiatry, 2020;7(9):801-812. [CrossRef]

- Ventriglio A, Bhugra D, Sampogna G, Luciano M, De Berardis D, Sani G, Fiorillo A. From dysthimia to treatment-resistant depression: evolution of a psychopathological construct. Int Rev Psychiatry, 2020;32(3-5):471-476. [CrossRef]

- Keller MB, Hirschfeld RM, Hanks D. Double depression: a distinctive subtype of unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 1997;45(1–2):65–73. [CrossRef]

- Ciaramella A, Silvestri S, Pozzolini V, Federici M, Carli G. A retrospective observational study comparing somatosensory amplification in fibromyalgia, chronic pain, psychiatric disorders and healthy subjects. Scand J Pain. 2020;21(2):317–29. [CrossRef]

- Howe CQ, Robinson JP, Sullivan MD. Psychiatric and psychological perspectives on chronic pain. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2015;26(2):283–300. [CrossRef]

- Løge-Hagen JS, Sæle A, Juhl C, Bech P, Stenager E, Mellentin AI. Prevalence of depressive disorder among patients with fibromyalgia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2019;245:1098–105. [CrossRef]

- Torres X, Bailles E, Valdes M, Gutierrez F, Peri JM, Arias A, et al. Personality does not distinguish people with fibromyalgia but identifies subgroups of patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(6):640-648. [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann E, Glanert S, Hüppe M, Moncada Garay AS, Tschepe S, Schweiger U, et al. Psychometric evaluation of a screening question for persistent depressive disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):119. [CrossRef]

- Keller D, de Gracia M, Cladellas R. Subtypes of patients with fibromyalgia, psychopathological characteristics and quality of life. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2011;39(5):273–9. [PubMed]

- Glazer Y, Cohen H, Buskila D, Ebstein RP, Glotser L, Neumann L. Are psychological distress symptoms different in fibromyalgia patients compared to relatives with and without fibromyalgia? Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27(5 Suppl 56).

- Salgueiro M, Aira Z, Buesa I, Bilbao J, Azkue JJ. Is psychological distress intrinsic to fibromyalgia syndrome? Cross-sectional analysis in two clinical presentations. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32(11):3463-3469. [CrossRef]

- Novo R, Gonzalez B, Peres R, & Aguiar P. A meta-analysis of studies with the Minnesota multiphasic personality inventory in fibromyalgia patients. Personality and Individual Differences, 2017;116, 96–108.

- Naylor B, Boag S, Gustin SM. New evidence for a pain personality? A critical review of the last 120 years of pain and personality. Scand J Pain, 2017;17, 58–67. [CrossRef]

- Doreste et al. unpublished.

- Rossi G, Derksen J. International Adaptations of the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory: Construct Validity and Clinical Applications. J Pers Asses, 2015;97(6), 572–590. [CrossRef]

- Teixidó-Abiol L, De Arriba-Arnau A, Seguí-Montesino J, Gil-Gallardo GH, Sánchez-López MJ, De Sanctis Briggs V. Psychopathological and personality profile in chronic nononcologic nociceptive and neuropathic pain: cross-sectional comparative study. Int J Psychol Red (Medellin), 2023(15(2):51-67. [CrossRef]

- Saulsman LM. Depression, anxiety, and the MCMI-III: construct validity and diagnostic efficiency. J Pers Assess, 2011;93(1):76-93. [CrossRef]

- Karlin BE, Creech SK, Grimes JS, Clark TS, Meagher MW, Morey L. The personality assessment inventory with chronic pain patients: psychometric properties and clinical utility. J Clin Psychol. 2005;61(12):1571–85. [CrossRef]

- Wolfe F, Anderson J, Harkness D, Bennett RM, Caro XJ, Goldenberg DL, et al. A prospective, longitudinal, multicenter study of service utilization and costs in fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(9):1560–70. [CrossRef]

- Millon T, Davis R, Millon C. Inventario Clínico Multiaxial de Millon-III (MCMI-III), 2a edición. Manual (Adaptación española: Cardenal V, Sánchez MP). Madrid: TEA Ediciones, SA; 2009.

- Cardenal V, Sánchez M. Adaptación y baremación al español del Inventario Clínico Multiaxial de Millon-III (MCMI-III). Madrid: TEA Ediciones, SA; 2007.

- Millon T. Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory-III (MCMI-III), 3rd ed. Minneapolis, MN: Pearson Assesssments; 2006.

- Ortiz-Tallo M, Cardenal V, Ferragut M, Cerezo MV (2011). Personalidad y s.ndromes cl.nicos: un estudio con el MCMI-III basado en una muestra española. Rev Psicopatol Psicol Clín, 2011;16 (1): 49. [CrossRef]

- Morey LC. Personality Assessment Inventory–Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, 1991.

- Burneo-Garcés C, Fernández-Alcántara M, Aguayo-Estremera R, Pérez-García M. Psychometric Properties of the Spanish Adaptation of the Personality Assessment Inventory in Correctional Settings: An ESEM Study. J Pers Assess. 2020;102(1):75–87. [CrossRef]

- Morey LC, & Alarcón MOT. PAI: inventario de evaluación de la personalidad. Manual de corrección, aplicación e interpretación. TEA Ediciones, 2013.

- Burckhardt CS, Clark SR, Bennett RM. The fibromyalgia impact questionnaire: development and validation. J Rheumatol. 1991;18(5):728–33. [PubMed]

- Rivera J, González T. The Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire: A validated Spanish version to assess the health status in women with fibromyalgia. Clin Exp Rheumatol,2004;22:554-560. [PubMed]

- Monterde S, Salvat I, Montull S, Fernández-Ballart J. Validation of the Spanish version of the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire. Rev Esp Reumatol, 2004;31(9):507-513. [PubMed]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988.

- Martínez MP, Sánchez AI, Prados G, Lami MJ, Villar B, Miró E. Fibromyalgia as a heterogeneous condition: subgroups of patients based on physical symptoms and cognitive-affective variables related to pain. Span J Psychol. 2021;24:e33. [CrossRef]

- Wan B, Gebauer S, Salas J, Jacobs CK, Breeden M, Scherrer JF. Gender-stratified prevalence of psychiatric and pain diagnoses in a primary care patient sample with fibromyalgia. Pain Med. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Biton L, Buskila D, Nissanholtz-Gannot R. Review of Fibromyalgia (FM) Syndrome Treatments. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(12106). [CrossRef]

- Niculescu AB 3rd, Akiskal HS. Proposed endophenotypes of dysthymia: evolutionary, clinical and pharmacogenomic considerations. Mol Psychiatry. 2001 Jul;6(4):363-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| CHARACTERISTICS | STATISTICS DESCRIPTIVES |

|---|---|

| Age (years) (mean [SD]) | 49.18 [8.09] |

| Tender points [0-18] (mean [SD]) | 17.27 [1.35] |

| Years from FM diagnostic (mean [SD]) | 6.76 [6.86] |

| Level of studies (n [%]) | |

| Primary studies | 7 [10.6] |

| Secondary studies | 8 [12.1] |

| Bachelor | 12 [18.2] |

| Professional studies | 19 [28.8] |

| University | 20 [30.3] |

| Associated symptoms*: (mean [SD]) | |

| Morning tiredness | 76.44 [20.72] |

| Unrefreshed sleep | 74.88 [19.0] |

| Fragmented sleep | 59.85 [33.07] |

| Fatigue | 77.64 [14.91] |

| Morning stiffness | 71.20 [24.71] |

| Stiffness after resting | 60.91 [26.29] |

| Subjective swelling | 50.42 [32.91] |

| Paraesthesias | 58.45 [27.40] |

| Headache | 60.15 [31.4] |

| Symptoms of irritable bowel | 42.95 [37.66] |

| Depression symptoms | 58.67 [31.51] |

| Anxiety symptoms | 59.92 [35.06] |

| Subjective difficulties of attention and concentration | 65.50 [25.86] |

| Subjective memory complains | 65.80 [24.69] |

| FIQ**: global score (mean [SD]) | 67.01 [13.09] |

| Physical dysfunction | 5.88 [2.18] |

| General discomfort | 7.86 [2.59] |

| Sick leave caused by FM | 4.45 [3.45] |

| Pain at work | 6.98 [1.94] |

| Pain | 7.20 [1.56] |

| Fatigue | 7.85 [1.36] |

| Morning tiredness | 7.48 [2.03] |

| Stiffness | 6.85 [2.33] |

| Anxiety | 6.48 [2.70] |

| Depression | 5.63 [2.85] |

| Stable medication regime (n [%]) | |

| Analgesic (NSAIDs and/or Opioids) | 43 [68.3] |

| Anti-inflammatory | 37 [58.7] |

| Antidepressant | 47 [74.6] |

| Type of antidepressant | |

| ISRS | 20 [31.7] |

| Dual | 11 [17.5] |

| Tricyclic | 17 [27] |

| Benzodiazepine | 23 [36.5] |

| Type of benzodiazepine | |

| Short life | 10 [15.9] |

| Medium life | 3 [4.8] |

| Long life | 10 [15.9] |

| CHARACTERISTICS | GROUP NAD (n=30) |

GROUP PDD (n=23) | GROUP PDD+MD (n=13) | P | Pairwise | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (mean [SD]) | 48.57 [8.67] | 50.26 [7.28] | 48.69 [8.48] | .733 | ||

| Tender points (0-18) (mean [SD]) | 17.17 [1.46] | 17.39 [.94] | 17.27 [1.84] | .780 | ||

| Years from diagnostic (mean [SD]) | 7.97 [7.47] | 5.76 [6.18] | 5.74 [6.58] | .335 | ||

| Level of studies (n [%]) | .680 | |||||

| Primary studies | 2 [6.7] | 4 [17.4] | 1 [7.7] | |||

| Secondary studies | 4 [13.3] | 1 [4.3] | 3 [23.1] | |||

| Bachelor | 5 [16.7] | 5 [21.7] | 2 [15.4] | |||

| Professional studies | 8 [26.7] | 8 [34.8] | 3 [23.1] | |||

| University | 11 [36.7] | 5 [21.7] | 4 [30.8] | |||

| Associated symptoms* (mean [SD]) | ||||||

| Morning tiredness | 73.20 [22.04] | 74.30 [21.22] | 87.69[12.35] | .062 | ||

| Unrefreshed sleep | 70.40 [22.32] | 77.61 [12.51] | 80.38 [19.19] | .176 | ||

| Fragmented sleep | 54.67 [35.01] | 63.26 [26.65] | 65.77 [39.15] | .288 | ||

| Fatigue | 75.5 [15.72] | 74.09 [13.36] | 88.85 [10.43] | .006 | c | |

| Morning stiffness | 66.8 [27.41] | 59.13 [28.55] | 79.62 [9.23] | .014 | c | |

| Stiffness after resting | 54.17 [26.26] | 53.17 [32.32] | 79.62 [9.23] | .002 | c | |

| Subjective swelling | 51.5 [30.77] | 52.00 [30.64] | 43.08 [39.87] | .862 | ||

| Paraesthesias | 58.9 [26.96] | 64.09 [30.66] | 68.85 [19.80] | .272 | ||

| Headache | 51.2 [32.29] | 64.09 [30.66] | 73.85 [25.75] | .026 | c | |

| Symptoms of irritable bowel | 34 [33.45] | 50.65 [38.56] | 50.00 [43.39] | .191 | ||

| Depression symptoms | 44.17 [34.19] | 64.65 [23.09] | 81.54 [20.35] | .001 | c | |

| Anxiety symptoms | 45.17 [38.56] | 61.52 [27.23] | 91.15 [10.03] | <.005 | c | |

| Subjective difficulties of attention and concentration | 62.83 [25.28] | 66.87 [26.24] | 69.23 [27.90] | .482 | ||

| Subjective memory complains | 65 [22.28] | 72.09 [29.69] | 56.54 [34.96] | .244 | ||

| FIQ**: global score (mean [SD]) | 62.20 [12.27] | 67.86 [12.54] | 75.23 [11.13] | .004 | b | |

| Physical dysfunction | 5.56 [1.99] | 6.14 [2.26] | 6.16 [2.49] | .322 | ||

| General discomfort | 7.74 [2.74] | 7.88 [2.93] | 8.60 [1.38] | .831 | ||

| Sick leave caused by FM | 4.49 [3.7] | 4.03 [3.00] | 5.10 [3.81] | .817 | ||

| Pain at work | 6.55 [2.01] | 7.26 [2.00] | 7.46 [1.56] | .332 | ||

| Pain | 7.03 [1.59] | 7.13 [1.66] | 7.69 [1.31] | .651 | ||

| Fatigue | 7.31 [1.44] | 8.17 [1.19] | 8.46 [1.05] | .018 | a, b | |

| Morning tiredness | 6.76 [2.06] | 7.65 [1.96] | 8.77 [1.36] | .006 | b | |

| Stiffness | 6.31 [2.48] | 6.78 [2.15] | 8.15 [1.90] | .055 | ||

| Anxiety | 5.86 [2.70] | 6.65 [2.49] | 7.54 [2.87] | .083 | ||

| Depression | 4.59 [3.01] | 5.87 [2.13] | 7.54 [2.69] | .006 | b, c | |

| Stable medication regime (n [%]) | ||||||

| Analgesic (NSAIDs and/or Opioids) | 18 [62.1] | 15 [65.2] | 10 [90.9] | .200 | ||

| Anti-inflammatory | 17 [58.6] | 13 [56.5] | 7 [63.6] | .925 | ||

| Antidepressant | 17 [58.6] | 20 [87.0] | 10 [90.9] | .000 | a | |

| Type of antidepressant | .038 | a, b | ||||

| ISRS | 10 [34.5] | 9 [39.1] | 1 [9.1] | |||

| Dual | 4 [13.8] | 3 [13.0] | 4 [36.4] | |||

| Tricyclic | 4 [13.8] | 8 [34.8] | 5 [45.5] | |||

| Benzodiazepine | 12 [41.4] | 6 [26.1] | 5 [45.5] | .416 | ||

| Type of benzodiazepine | .425 | |||||

| Short life | 5 [17.2] | 2 [8.7] | 3 [54.5] | |||

| Medium life | 3 [10.3] | 0 [0.0] | 3 [27.3] | |||

| Long life | 4 [13.8] | 4 [17.4] | 2 [18.2] |

| PAI Clinical Scale | NAD vs. PDD P (Cohen’s d) |

NAD vs. PDD+MD P (Cohen’s d) |

PDD vs. PDD+MD P (Cohen’s d) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | 1.00 (0.26) | .030 (1.03) | .190 (0.74) |

| Depression | .024 (0.90) | <.005 (1.85) | .027 (1.28) |

| Schizophrenia | .812 (0.38) | .010 (1.25) | .161 (0.61) |

| Suicidal ideation | .619 (0.33) | .018 (0.94) | .312 (0.56) |

| Dominance | .017 (0.81) | .404 (0.28) | 1.00 (0.62) |

| PAI Clinical Subscale | |||

| Illness-health concern | 1.00 (0.19) | .021 (0.85) | .203 (0.67) |

| Cognitive anxiety | .516 (0.44) | .004 (1.18) | .136 (0.78) |

| Physiological anxiety | 1.00 (0.25) | .032 (1.00) | .161 (0.61) |

| Cognitive depression | .015 (0.93) | .000 (1.64) | .084 (0.75) |

| Emotional depression | .050 (0.79) | .000 (1.59) | .132(0.96) |

| Physiological depression | .653 (0.42) | .009 (1.09) | .190 (0.71) |

| Grandeur | .052 (0.79) | .011 (0.90) | 1.00 (0.26) |

| Identity alteration | .091 (0.69) | .000 (1.51) | .168 (0.74) |

| PAI Complementary items | |||

| Potential suicide index | .489 (0.46) | .000 (1.59) | .030 (0.84) |

| Potential violence index | 1.00 (0.14) | .088 (0.65) | .060 (0.84) |

| Treatment difficulty index | .546 (0.17) | .069 (0.68) | .004 (0.78) |

| PAI Clinical Scales | PDD vs. NAD | PDD vs. PDD+MD |

|---|---|---|

| Dominance | -.266 | - |

| PAI Clinical Subscales | ||

| Cognitive depression | .303 | .107 |

| Emotional depression | .176 | .682 |

| Physiological depression | - | .545 |

| Cognitive anxiety | - | .414 |

| Grandeur | -.415 | - |

| Identity alteration | .370 | .281 |

| PAI Complementary items | ||

| Potential suicide index | - | -.204 |

| Discriminant analysis indices | ||

| Eigenvalue | .379 | .536 |

| Significance | .008 | .038 |

| Canonical correlation | .424 | .591 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).