Submitted:

29 October 2024

Posted:

29 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction and Motivation

1.1. Methods and Contributions

1.2. Paper Structure

2. Background

2.1. Protograph-Based LDPC Codes

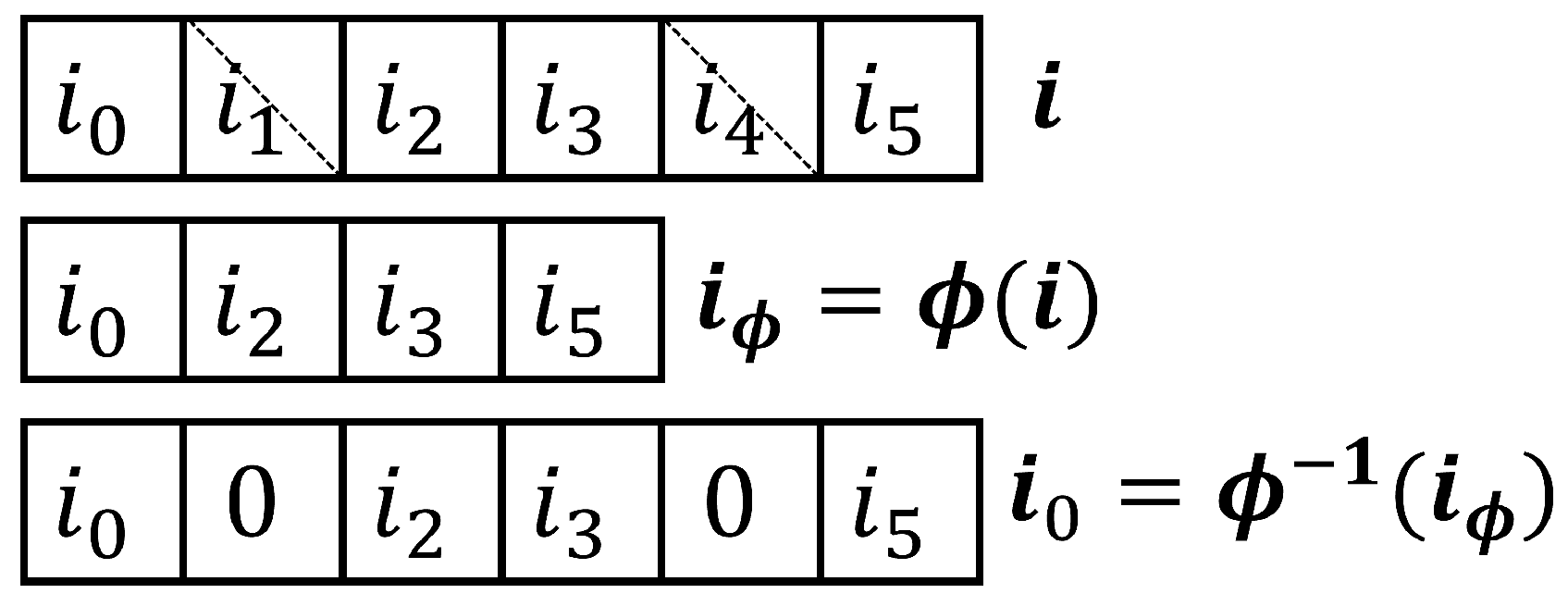

2.2. Puncturing Linear Codes

2.3. Shortening Linear Codes

3. Asymptotic Random Puncturing Analyses of ARTM0 Protographs

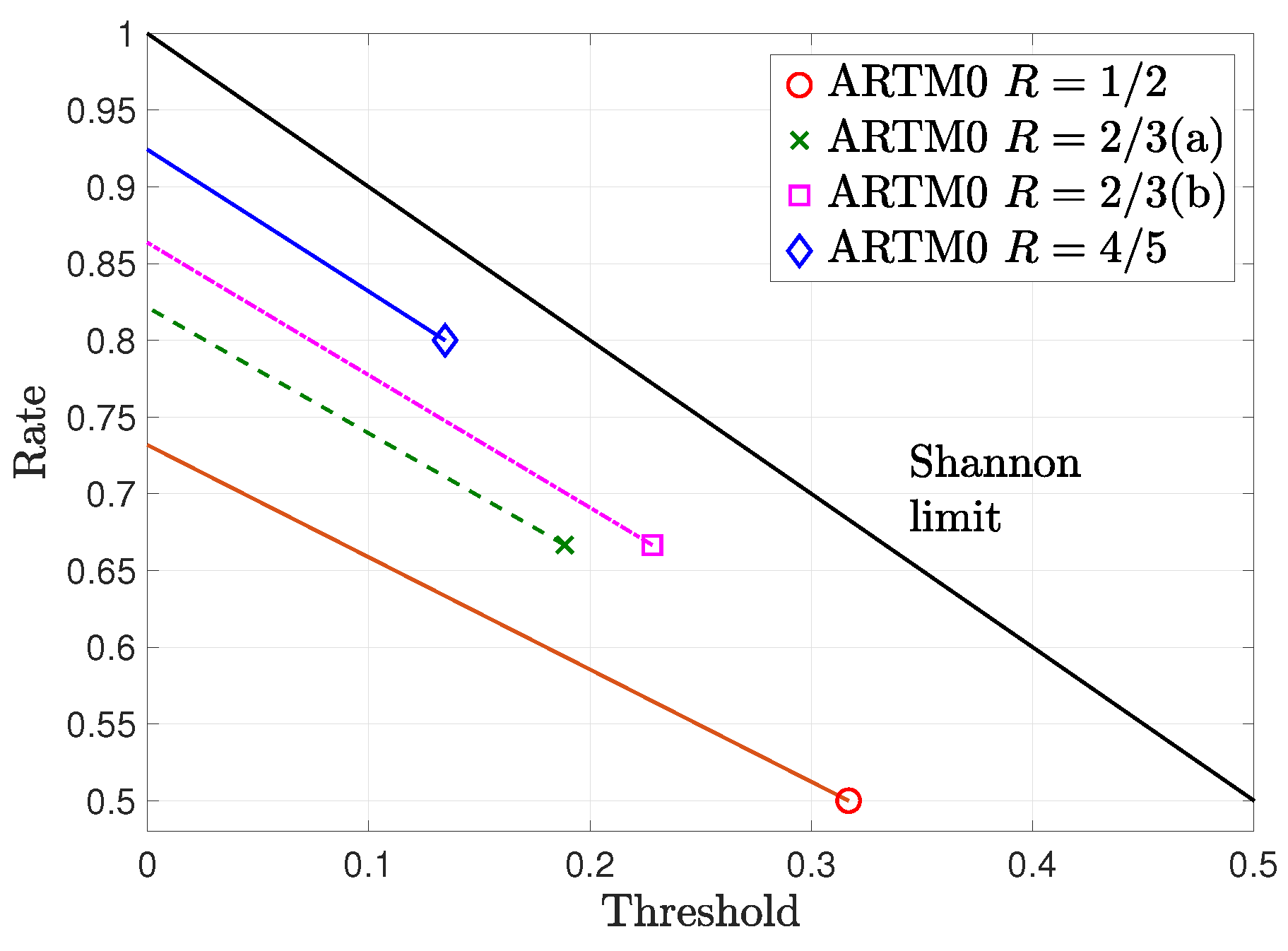

3.1. Thresholds of Randomly Punctured ARTM0 Code Ensembles on the BEC

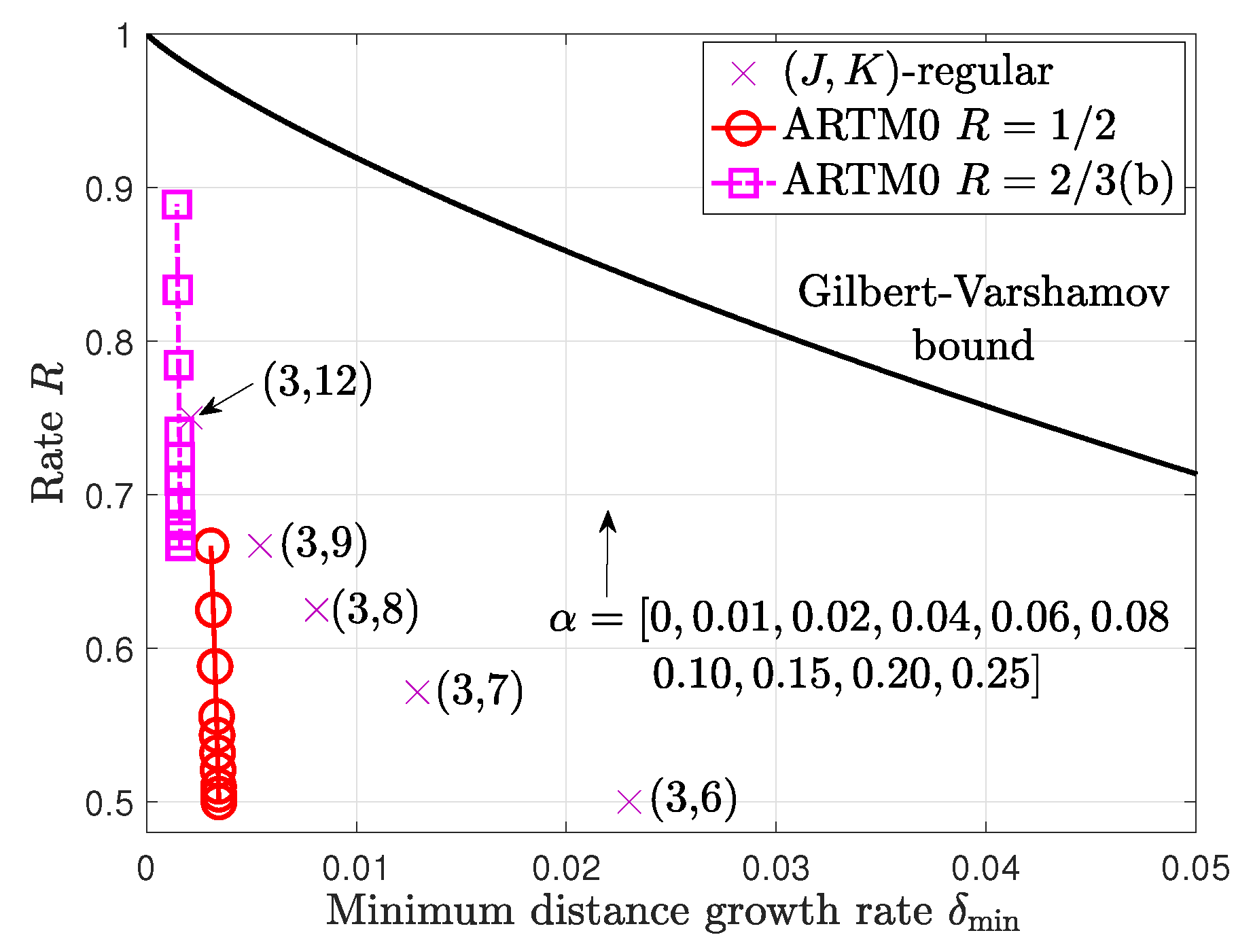

3.2. Minimum Distance Growth Rates of Randomly Punctured ARTM0 Code Ensembles

4. Random Puncturing of ARTM0 LDPC Codes

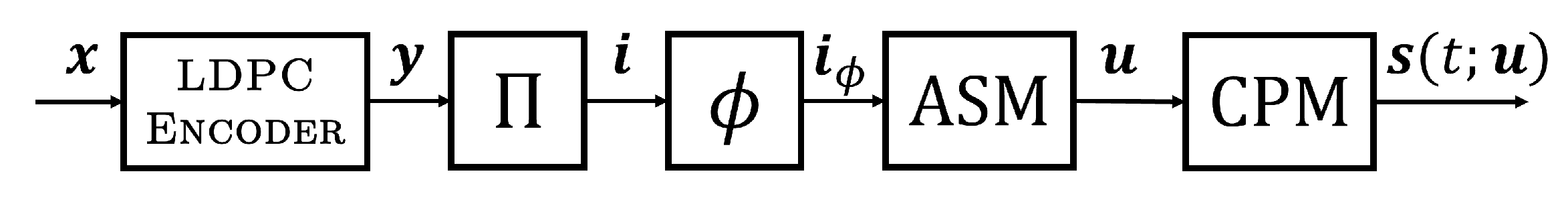

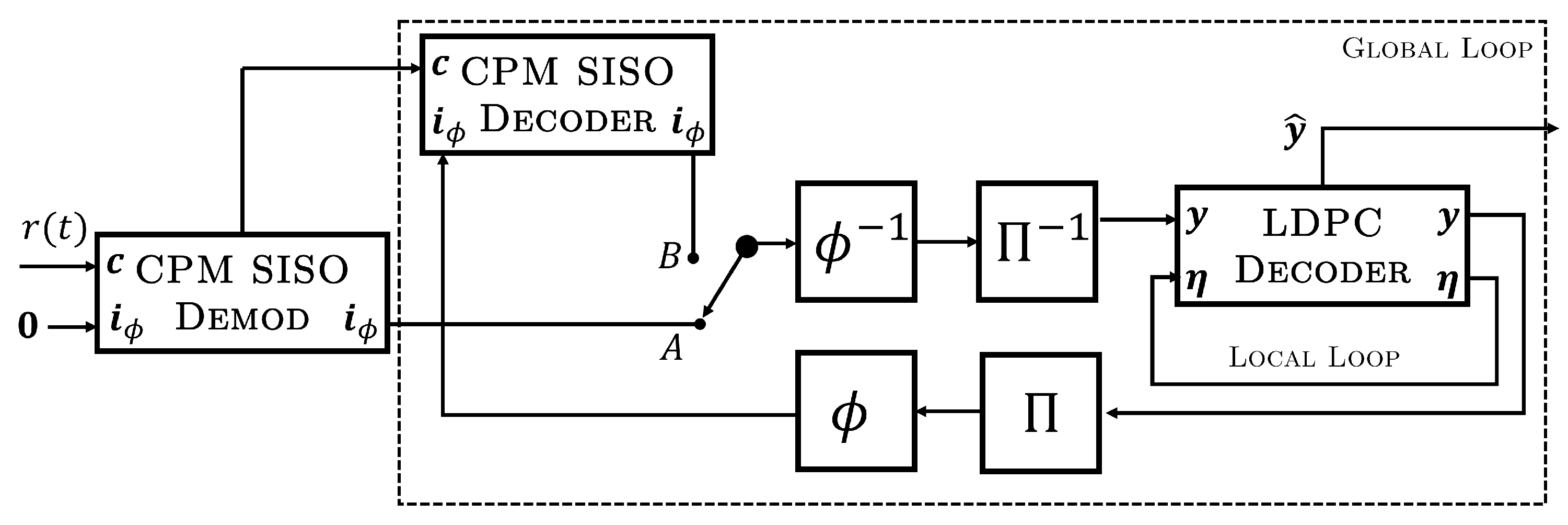

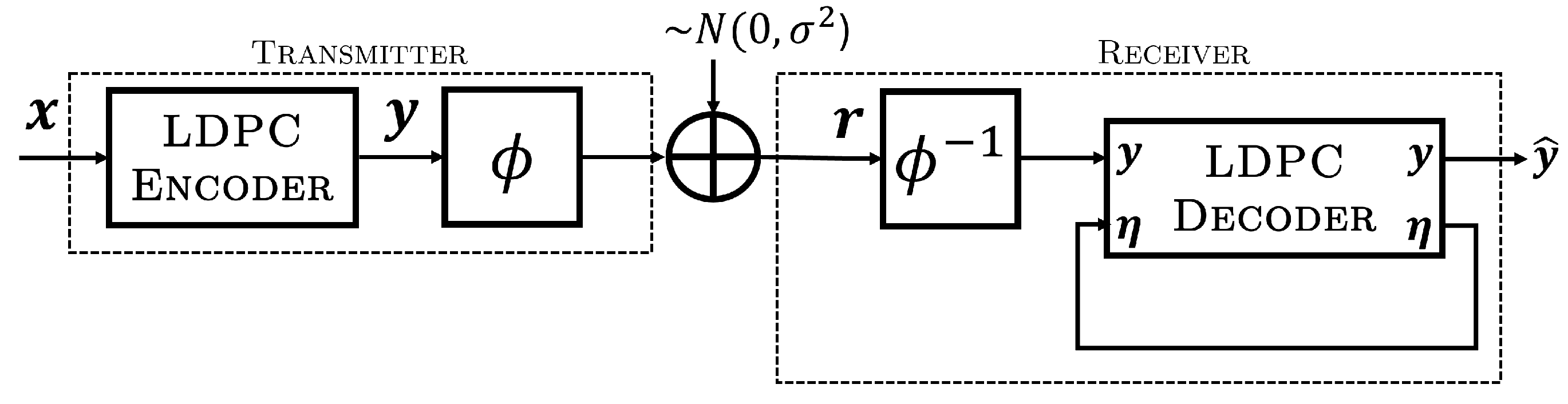

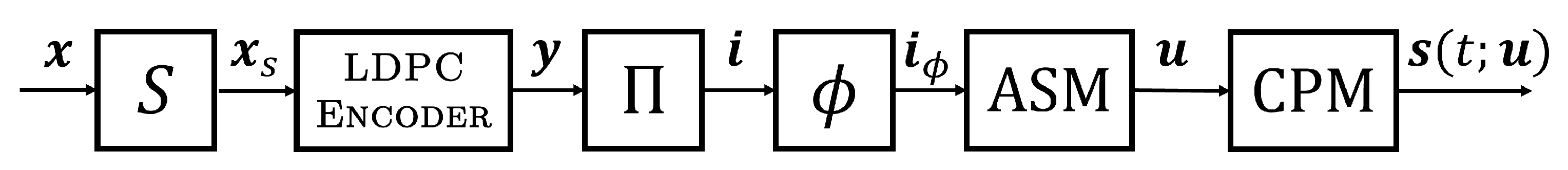

4.1. System Model

4.2. Random Puncturing Overhead

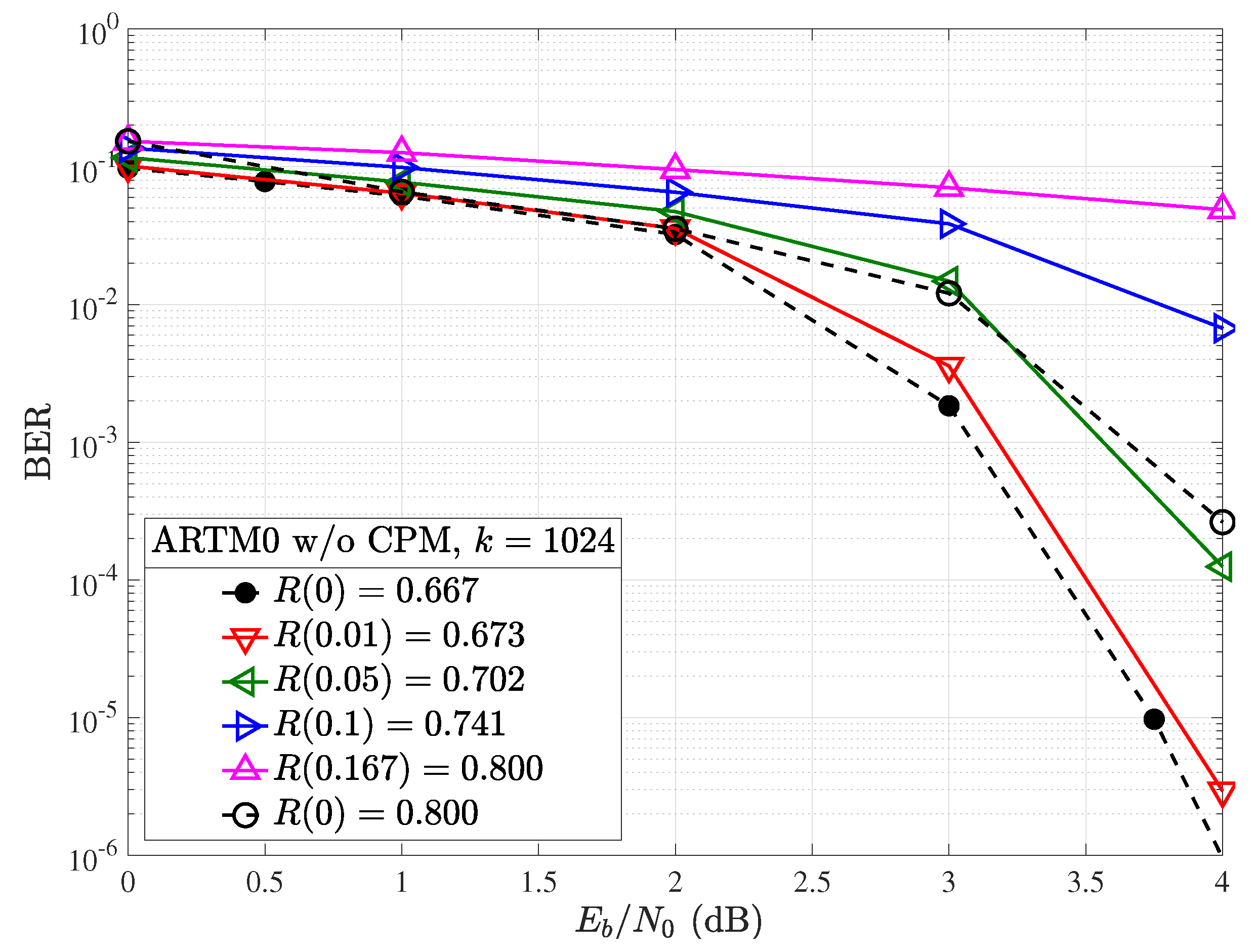

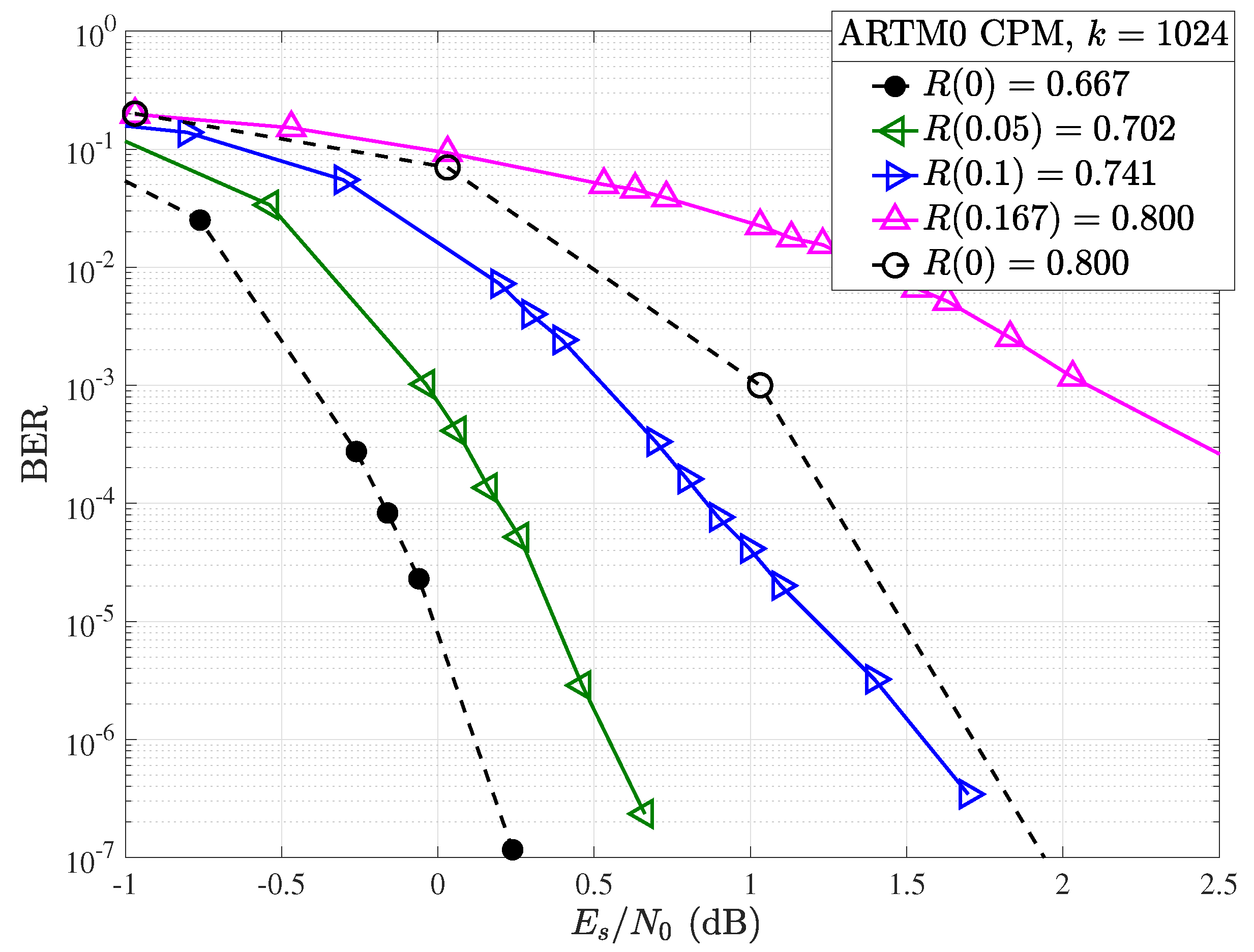

4.3. Numerical Results

4.3.1. Isolated Code, No CPM

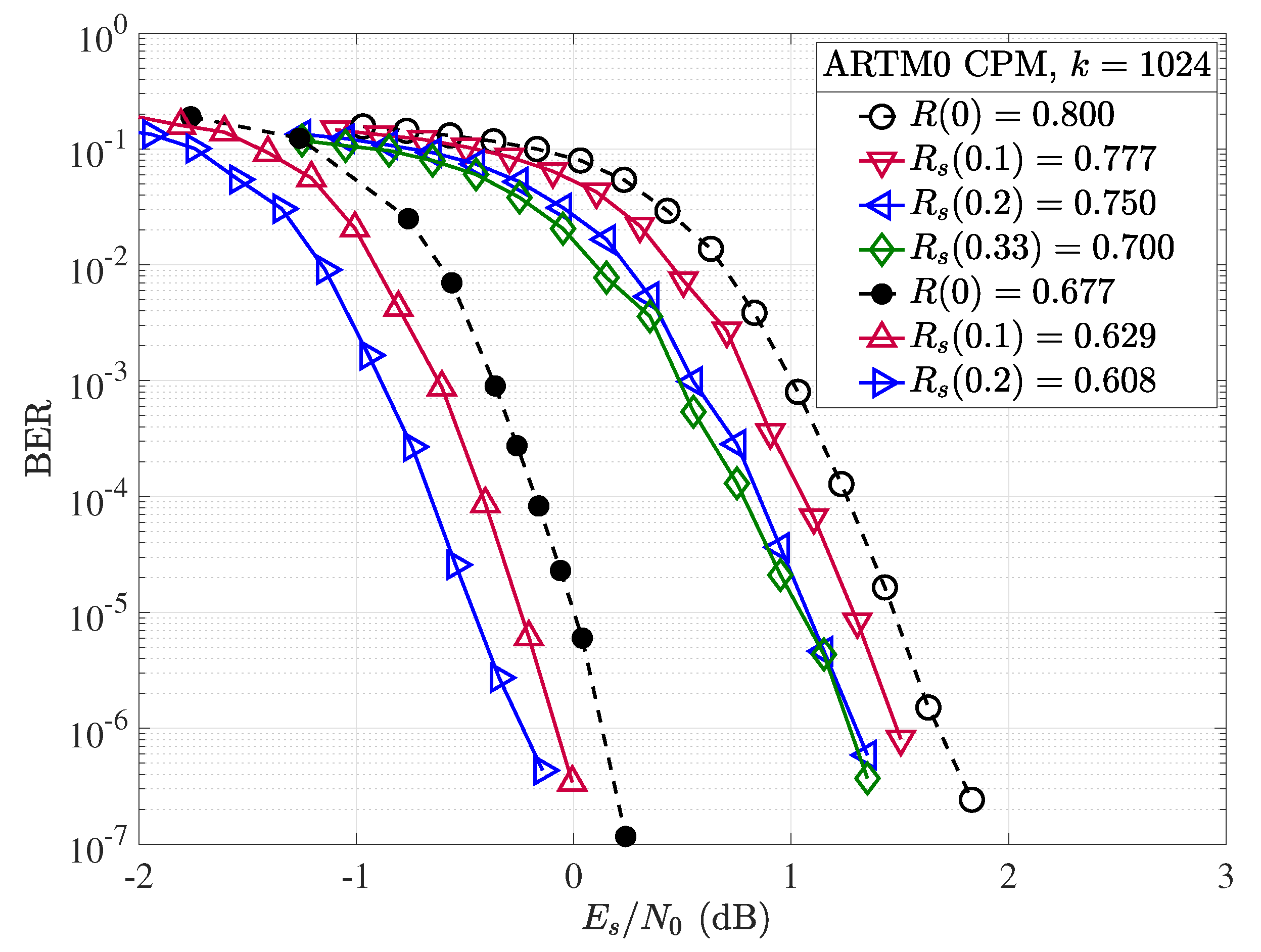

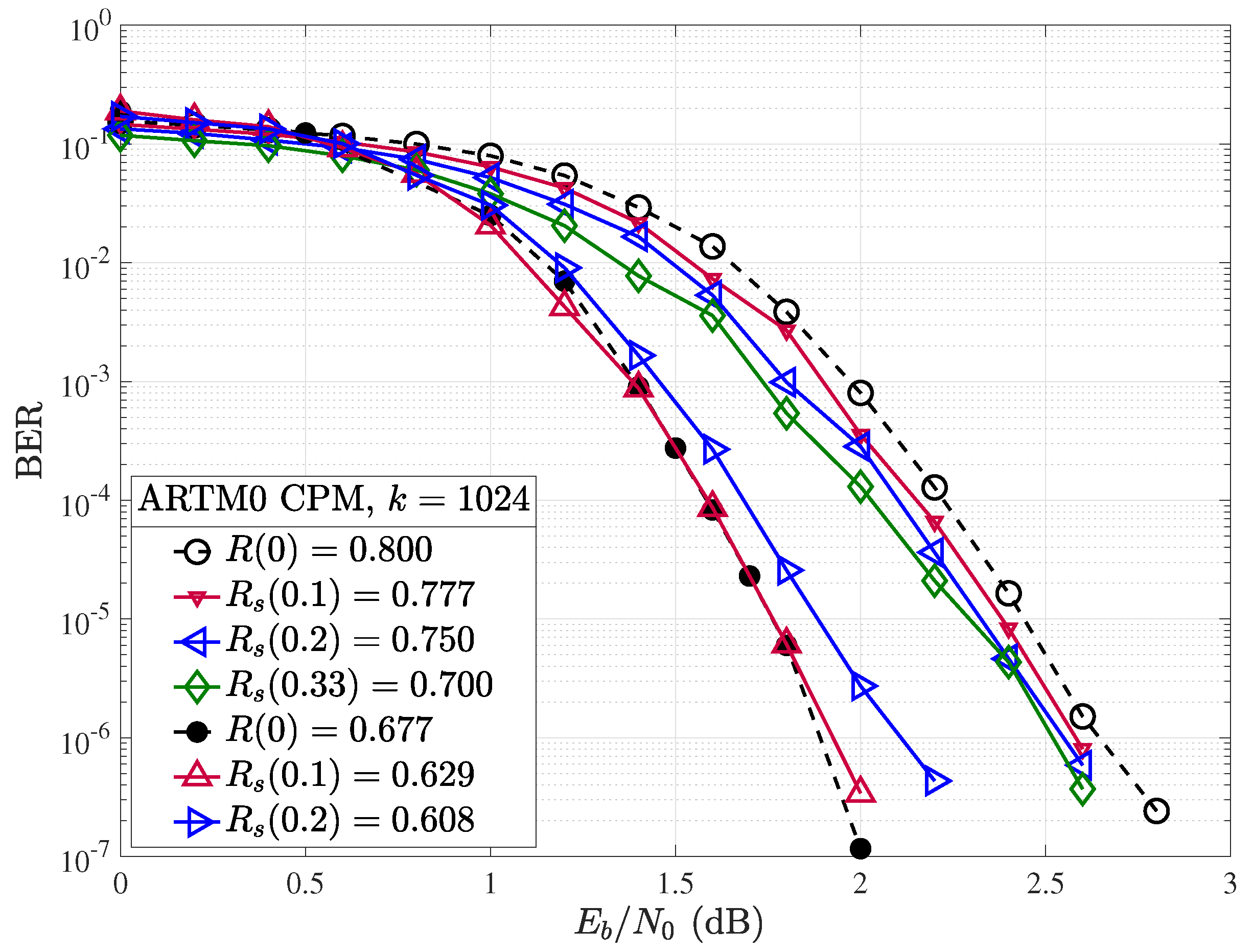

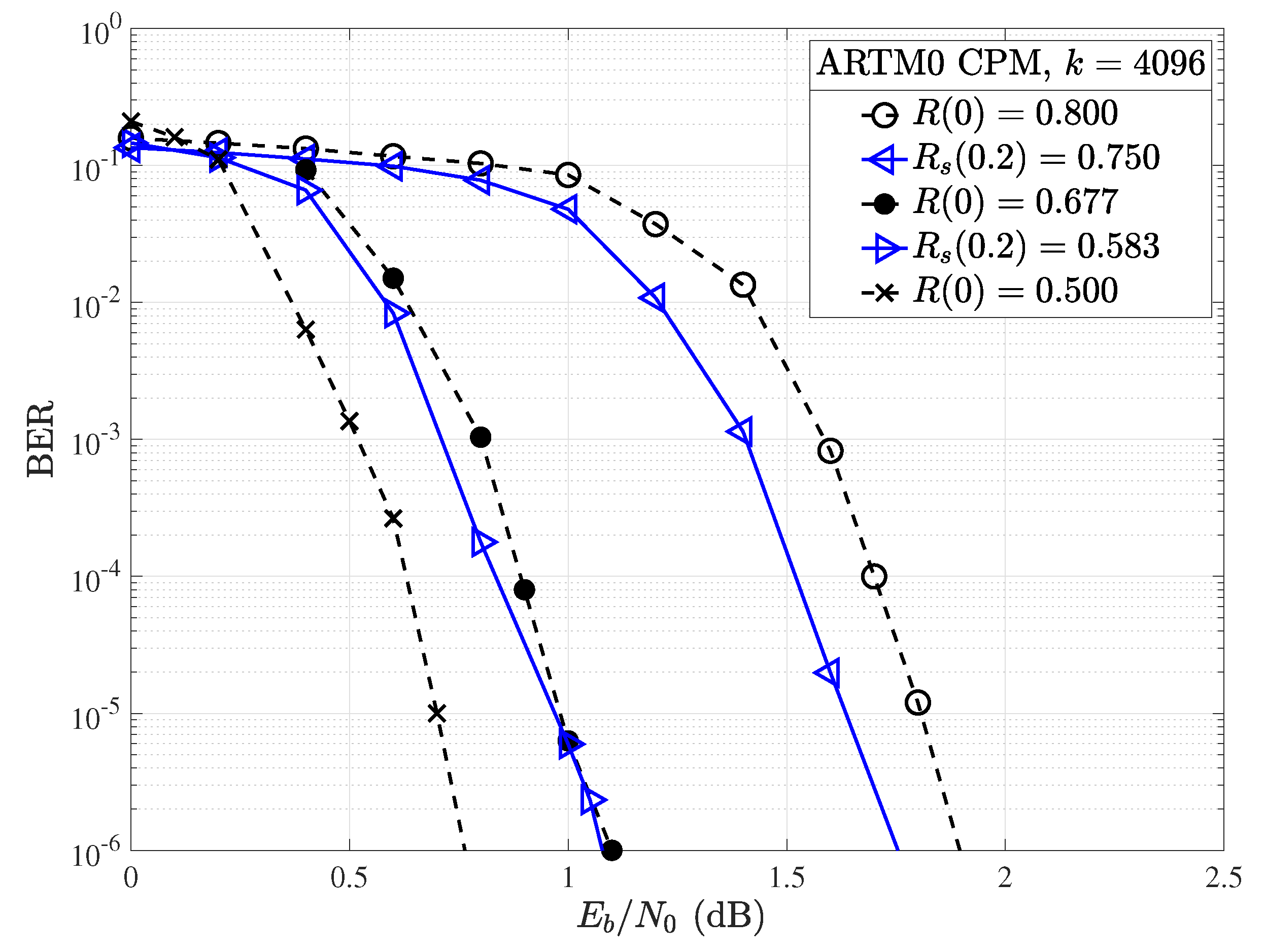

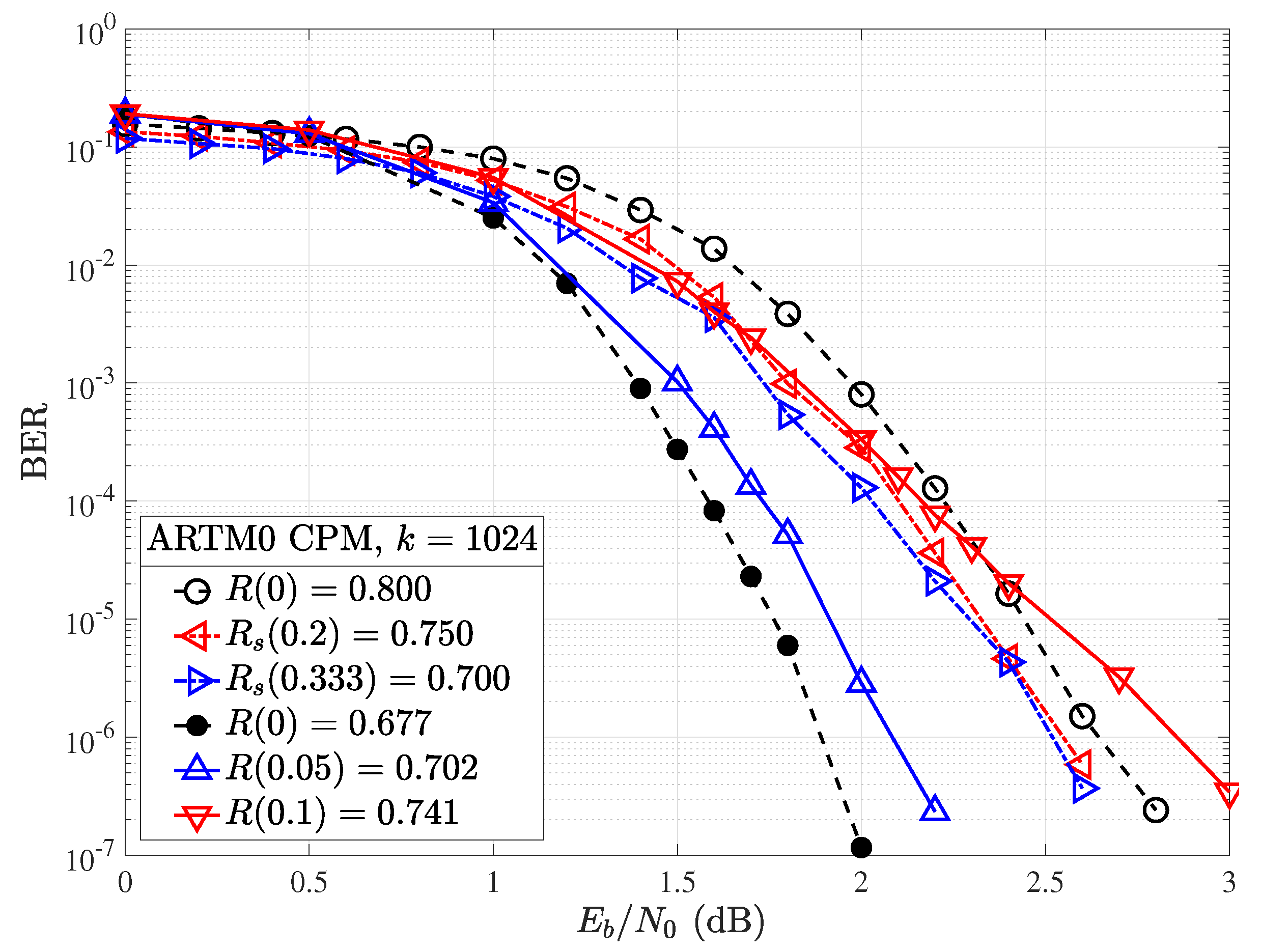

4.3.2. CPM Included

5. Random Shortening of ARTM0 LDPC Codes

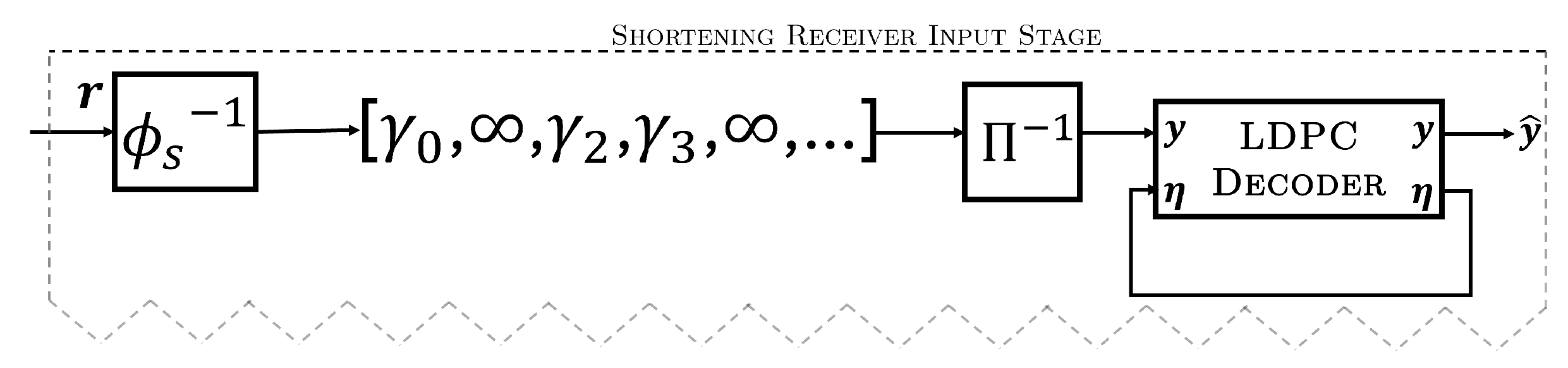

5.1. Model and Method

5.2. Numerical Results

5.3. Puncturing vs. Shortening

6. Hardware Considerations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ARTM | Advanced Range TeleMetry |

| ASM | Attached Sync Marker |

| AWGN | Additive White Gaussian Noise |

| BEC | Binary Erasure Channel |

| BER | Bit Error Rate |

| BP | Belief Propagation |

| BPSK | Binary Phase-shift Keying |

| CPM | Continuous Phase Modulation |

| FEC | Forward Error Correction |

| FM | Frequency Modulation |

| LDPC | Low-Density Parity-Check |

| LLR | Log-likelihood Ratio |

| MSA | Min-sum Algorithm |

| PCM | Pulse Code Modulation |

| QC | Quasi-cyclic |

| SISO | Soft-in, Soft-out |

| SOQPSK-TG | Telemetry Group version of Shaped-Offset Quadrature Phase Shift Keying |

| SPA | Sum-product Algorithm |

References

- Gallager, R. Low-density parity-check codes. IRE Trans. on Info. Theory 1962, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, D. J. C. Near Shannon Limit Performance of Low Density Parity Check Codes. Elect. Letters 1997, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. J. Richardson and R. L., Urbanke. The Capacity of Low-Density Parity-Check Codes Under Message-Passing Decoding. IEEE Trans. on Info. Theory 2001, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Z. Li, et al., Efficient encoding of quasi-cyclic low-density parity-check codes. IEEE Trans. on Comms. 2006; 54.

- T. Richardson and H. Jin, “LDPC encoding methods and apparatus,” U.S. Patent No. 7,346,832 (Assigned to Qualcomm Inc.), 2008.

- X-Y Hu, et al., “Efficient implementations of the sum-product algorithm for decoding LDPC codes,” Proc. IEEE Global Telecomms. Conf., vol. 2, cat. no. 01CH37270, 2001.

- C-C. Cheng. A fully parallel LDPC decoder architecture using probabilistic min-sum algorithm for high-throughput applications. IEEE Trans. on Circ. and Sys. I: Reg. Papers 2014, 61. [CrossRef]

- Range Commanders Council Telemetry Group, Range Commanders Council, “IRIG Standard 106-23,” Telemetry Standards, White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico, 2024 (irig106.org).

- E. Perrins, “LDPC codes for IRIG-106 waveforms: Part I–Code Design,” Proc. Int. Telemetering Conf., (Las Vegas, NV), Oct. 2023.

- E. Perrins, “LDPC codes for IRIG-106 waveforms: Part II–Receiver Design,” Proc. Int. Telemetering Conf., (Las Vegas, NV), Oct. 2023.

- J. Hagenauer, “Rate-compatible punctured convolutional codes (RCPC codes) and their applications,” IEEE Trans. on Comms., vol. 36 no. 4, 1988.

- J. Ha, J. Kim, and S. W. McLaughlin. Rate-compatible puncturing of low-density parity-check codes. IEEE Trans. on Info. Theory 2004, 50. [Google Scholar]

- H. Zhou, D. G. M. Mitchell, N. Goertz. Robust Rate-Compatible Punctured LDPC Convolutional Codes. IEEE Trans. on Comms. 2013, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. G. M. Mitchell, M. Lentmaier, A. Pusane, and D. J. Costello Jr., “Randomly Punctured LDPC Codes,” IEEE Journ. on Selected Areas in Comms., vol. 34 no. 2, Feb. 2016.

- A. D. Cummins, D. G. M. Mitchell, and E. Perrins, “Spectrally Efficient LDPC Codes for IRIG-106 Waveforms via Random Puncturing,” Proc. Int. Telemetering Conf., (Glendale, AZ), Oct. 2024.

- S. Lin and D. J. Costello, Jr., “Error Control Coding: Fundamentals and Applications,” Prentice Hall, 2004.

- T. Tian and C. R. Jones, “Construction of rate-compatible LDPC codes utilizing information shortening and parity puncturing,” EURASIP J. Wirel. Commun. Netw., vol. 2005, no. 5, pp. 789-795, Oct. 2005.

- S. -R. Kim and D. -J. Shin, “Lowering Error Floors of Systematic LDPC Codes Using Data Shortening,” IEEE Communications Letters, vol. 17, no. 12, pp. 2348-2351, Dec. 2013.

- A. Suls, Y. Lefevre, J. Van Hecke, M. Guenach and M. Moeneclaey, “Error Performance Prediction of Randomly Shortened and Punctured LDPC Codes,” IEEE Communications Letters, vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 560-563, April 2019.

- J. Thorpe, “Low-density parity-check (LDPC) codes constructed from protographs,” Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, CA, INP Progress Report 42-154, Aug. 2003.

- R. G. Gallager, “Low-density parity-check codes,” Ph.D. dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, 1963.

- D. Divsalar, S. Dolinar, C. Jones, and K. Andrews, “Capacity-approaching protograph codes,” IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun., vol. 27, no. 6, pp. 876–888, Aug. 2009.

- E. C. Boyle and R. J. McEliece, “Asymptotic weight enumerators of randomly punctured, expurgated and shortened code ensembles,” in Proc. Forty-Sixth Annual Allerton Conference, Monticello, IL, Sept. 2008.

- C.-H. Hsu and A. Anastasopoulos, “Capacity achieving LDPC codes through puncturing,” IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory, vol. 54, no. 10, pp. 4698–4706, Oct. 2008.

- F. Kschischang, B. J. Frey, and H. A. Loeliger. Factor graphs and the sum-product algorithm. IEEE Trans. on Info. Theory 2001, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | For the rate of the ensemble can be written as , where . Bounds on and conditions such that were given for -regular LDPC code ensembles in [24]. |

| 2 | The , , ARTM0 code is constructed from the lifted base matrix [9]. |

| 3 | In this paper, rates are rounded to three decimal places. |

| ARTM0 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).