1. Introduction

The importance of education as a catalyst for socio-economic development is universally acknowledged. However, the Indian education system has struggled to provide equitable, high-quality education for its vast and diverse population [

1]. This section introduces the historical context, including the colonial legacy, and the socio-economic structure that contributes to present-day challenges [

2]. Discuss the colonial roots of India’s educational framework, which emphasized rote learning and limited critical thinking [

3]. Additionally, consider India's socio-economic diversity and the rural-urban divide that exacerbates disparities in educational access and quality [

4]. This paper aims to review existing literature on systemic challenges, providing a holistic overview of barriers within India’s educational system while proposing actionable reforms [

5]. Education is a cornerstone for any nation's development, acting as a foundation for social mobility and economic progress [

6]. However, the Indian education system has been criticized for its inability to provide high-quality, equitable education to all. The traditional structure, rooted in colonial legacies, has undergone incremental changes over decades, yet it still struggles with challenges that have a significant impact on student learning and workforce readiness. This paper reviews the current state of education in India, focusing on primary and secondary education, and provides insights into the root causes of the system's inadequacies. India’s education system has been a subject of both domestic and international scrutiny due to its diverse challenges, including rigid curricula, economic disparities, and infrastructural deficits [

7]. Scholars and policymakers argue that reforms are essential to improve educational outcomes and bridge the urban-rural divide. This literature review explores research on critical problem areas in Indian education and examines proposed reform strategies. It also highlights insights from international education models that offer valuable lessons for India.

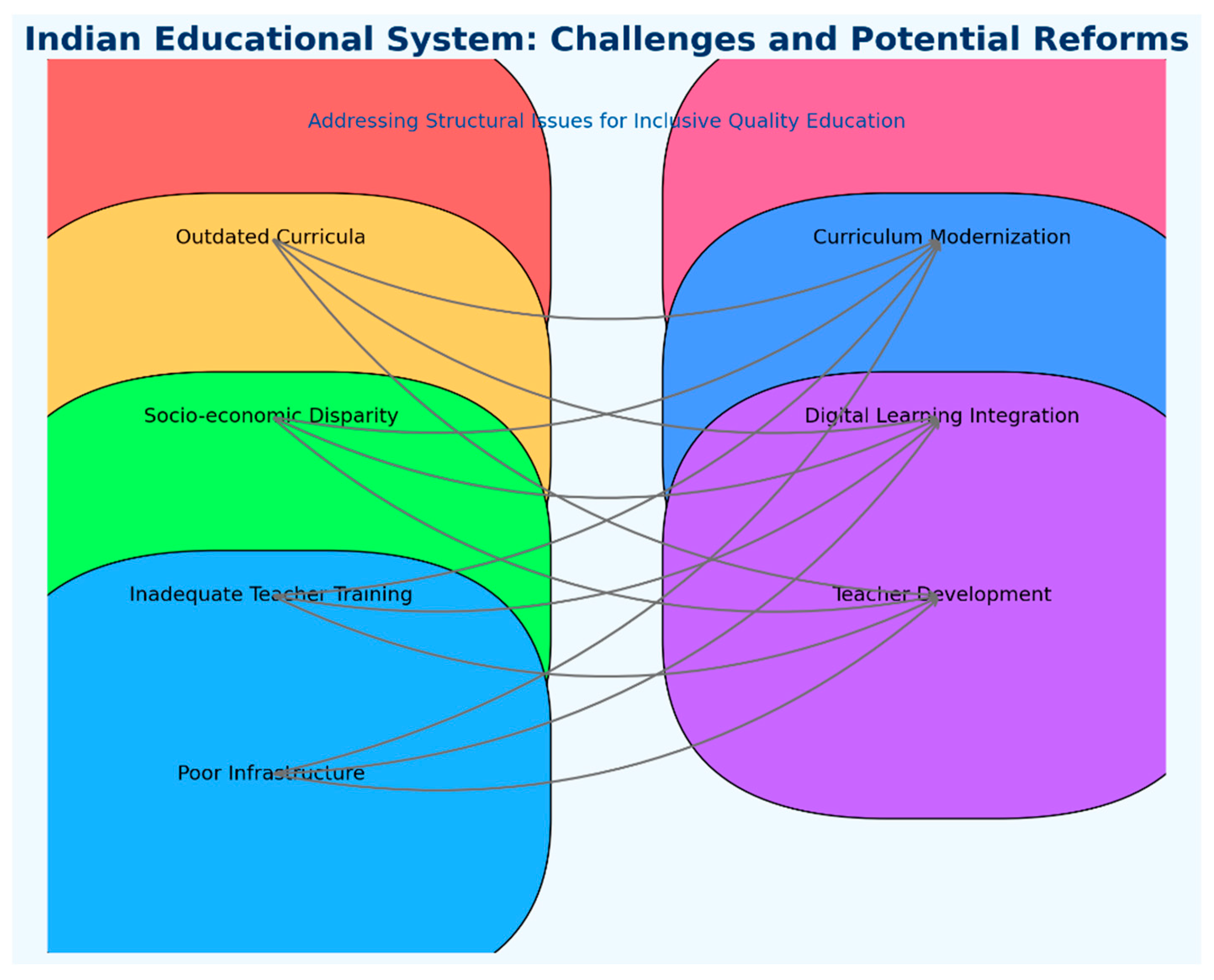

Figure 1.

Graphical abstract Challenges and Solutions.

Figure 1.

Graphical abstract Challenges and Solutions.

2. Curriculum and Pedagogical Gaps

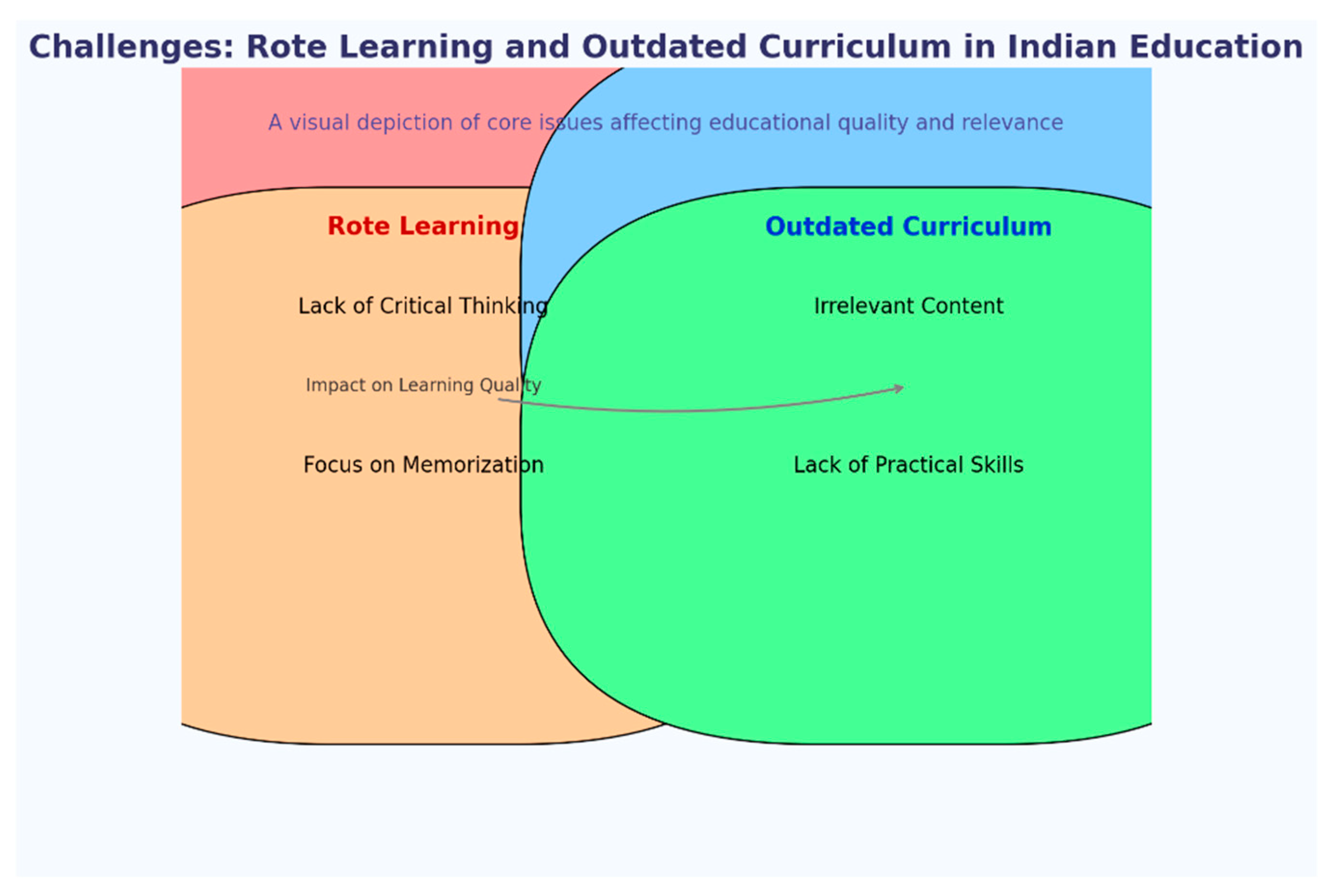

Figure 2.

Rote Learning and Outdated Curriculum.

Figure 2.

Rote Learning and Outdated Curriculum.

The Indian curriculum has often been criticized for emphasizing rote learning and theoretical knowledge, with limited focus on critical thinking and problem-solving skills [

8]. Scholars argue that this approach fails to equip students with practical knowledge applicable in real-world contexts. For instance, [

9] discuss how the heavy emphasis on memorization restricts students’ creativity and innovation. Additionally, a study by [

10] highlights that the curriculum does not align with the skill demands of the 21st-century job market, particularly in fields like technology and engineering.

Pedagogical approaches in India tend to be teacher-centered, with limited engagement from students in interactive learning. According to [11], traditional lecture-based methods limit student participation and reinforce passive learning behaviors. Alternative approaches, such as project-based and experiential learning, have shown positive impacts in other countries but remain underutilized in India.

Educational experts propose a shift toward a skills-based curriculum that incorporates critical thinking, creativity, and collaborative learning. [12] advocates for the integration of STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) and digital literacy into the core curriculum, aiming to prepare students for a knowledge-based economy.

3. Teacher Quality and Professional Development

Research consistently points to teacher quality as a significant determinant of student success. However, studies show that many Indian teachers lack formal training and access to continuous professional development []. According to [], the quality of teacher training varies widely, with rural schools being particularly disadvantaged due to limited resources and inadequate funding.

Overcrowded classrooms and high student-teacher ratios are common in Indian public schools, particularly in rural areas []. This imbalance reduces the effectiveness of teaching, as teachers cannot provide personalized attention to students. The lack of support staff also contributes to teacher burnout, which ultimately affects student learning outcomes.

To address these issues, scholars recommend increased investment in teacher training programs and initiatives to attract qualified educators to underserved areas. [] propose the establishment of digital training modules and mentorship programs to facilitate continuous learning for teachers, especially in remote locations.

4. Infrastructural Deficiencies

Infrastructure deficiencies in schools, particularly in rural areas, remain a significant barrier to education. Studies highlight that a large percentage of government schools lack basic facilities such as clean water, adequate sanitation, and functional classrooms []. According to [], these challenges are particularly severe in economically marginalized regions, where infrastructural neglect contributes to high dropout rates.

The COVID-19 pandemic emphasized the importance of digital infrastructure for continuity in education. Research by [] shows that while urban schools could transition to online learning, most rural schools lacked the necessary digital resources, deepening educational inequities. According to[], limited internet connectivity and the lack of digital devices have hindered the adoption of e-learning solutions in rural areas.

Addressing infrastructural deficiencies requires substantial government investment and public-private partnerships. [] suggests that the government could leverage corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives to support school infrastructure, particularly in rural regions. Digital inclusivity programs, such as providing low-cost devices and internet access, are also critical to bridging the urban-rural divide [].

5. Socioeconomic and Geographic Disparities

Economic and geographic disparities create a significant divide in educational access. Studies show that children from lower-income families often attend under-resourced government schools, while wealthier families opt for private institutions with better facilities and resources []. This dual system perpetuates a cycle of inequality, limiting opportunities for social mobility among marginalized groups.

India’s cultural and gender-based norms also impact educational access. Research indicates that girls and children from minority communities face additional barriers, including social stigma and economic constraints []. These factors contribute to higher dropout rates and limited academic achievement among these groups.

To promote equity, scholars propose scholarship programs, inclusive policies, and targeted outreach in marginalized communities. [] emphasizes the need for community engagement initiatives to raise awareness about the importance of education. Additionally, [] suggest the implementation of gender-sensitive policies to create supportive learning environments for girls and minority students.

6. Comparative Analysis of International Models

Finland’s education model emphasizes teacher autonomy, small class sizes, and a flexible curriculum, which have resulted in high educational outcomes []. According to [], the Finnish model encourages critical thinking and individualized learning, which could provide insights for curriculum reform in India.

South Korea has invested significantly in digital learning infrastructure and STEM education, fostering a highly skilled workforce. Research by [] highlights how digital tools in classrooms have improved student engagement and learning outcomes. This model offers valuable lessons for integrating technology into Indian education.

Singapore’s education system is known for its bilingual policy and skills-based curriculum that prepares students for the global job market []. Argue that the emphasis on language proficiency and vocational skills can enhance employability, a relevant insight for reforming India’s curriculum[].

The international models reviewed underscore the importance of flexible curricula, investment in teacher quality, and digital integration. Adaptation of these elements to India’s unique socio-economic context could drive effective reforms in the Indian educational system.

The literature consistently underscores the urgent need for systemic reforms in India’s educational landscape. Research suggests that a shift toward student-centered pedagogy, increased teacher support, and infrastructural investments are critical to enhancing educational equity and quality. Lessons from global education systems provide valuable insights for building a robust, inclusive, and adaptive educational framework in India. Future reforms must address the diversity of India’s student population, ensuring that every child has access to quality education, regardless of their socio-economic background.

References

- Agrawal, Mamta. "Curricular reform in schools: the importance of evaluation." Journal of curriculum studies 36.3 (2004): 361-379. [CrossRef]

- Bihari, Mr Saket. "REVITALIZING HIGHER EDUCATION IN INDIA: THE NEED FOR CURRICULUM REFORMS." TRANSFORMING HIGHER EDUCATION IN INDIA: PERSPECTIVES AND PATHWAYS (2022): 52.

- Banerjee, Abhijit V., et al. "Pitfalls of participatory programs: Evidence from a randomized evaluation in education in India." American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 2.1 (2010): 1-30. [CrossRef]

- Sapre, Padmakar. "Realizing the Potential of Education Management in India." Educational Management & Administration 30.1 (2002): 101-108. [CrossRef]

- Pande, Mansa, and Sonia Relia. "Educating adolescents in India: challenges and a proposed roadmap." Educating Adolescents Around the Globe: Becoming Who You Are in a World Full of Expectations. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020. 30-57.

- Yagnamurthy, Sreekanth. "Continuous and comprehensive evaluation (CCE): policy and practice at the national level." The Curriculum Journal 28.3 (2017): 421-441. [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, M. V. "Centralised evaluation practices: An ethnographic account of continuous and comprehensive evaluation in a government residential school in India." Contemporary Education Dialogue 12.1 (2015): 59-86.

- Gregory, Laura, and May Bend. "Modernizing curricula, instruction, and assessment to improve learning." Expectations and aspirations: A new framework for education in the Middle East and North Africa (2019): 161-182.

- Dalley, Karla, Lori Candela, and Jean Benzel-Lindley. "Learning to let go: the challenge of de-crowding the curriculum." Nurse Education Today 28.1 (2008): 62-69. [CrossRef]

- Collins, Allan. What's worth teaching?: Rethinking curriculum in the age of technology. Teachers College Press, 2017.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).