Submitted:

28 October 2024

Posted:

30 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The urinary tract, once considered sterile, is now understood to host a diverse community of microorganisms known as the urinary microbiome. This microbiome, which is made up of bacteria, fungi, and viruses, is important for preserving urological health and has been linked to the pathogenesis of a number of urinary tract disorders. In this review, we offer a consolidated overview of the urinary tract bacterial population, including its composition, diversity, and factors influencing its dynamics. We explore its involvement in urinary tract infections, interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS), urinary stone formation, and other urological diseases, highlighting the importance of understanding its correlation with disease pathology for the development of therapeutic strategies. Additionally, we explore its role in autoimmune diseases of the urinary tract and the potential of leveraging the urinary microbiome for targeted interventions in the treatment of urinary tract infections. Longitudinal studies are emphasized for their ability to elucidate microbial dynamics, establish causality, and ensure consistency and reproducibility across research endeavors. These efforts underscore the necessity for continued research and multidisciplinary collaborations in this rapidly evolving field to advance our understanding and therapeutic strategies for urinary tract disorders.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods to Study the Microbiome

2.1. Microbial Culturing

2.2. Metagenomic Sequencing

3. Variability of UT Microbiome

4. Role in Health and Disease

UTIs

Interstitial Cystitis or Bladder Pain Syndrome (IC/BPS)

Overactive Bladder Syndrome (OAB)

Urinary Incontinence (UI)

Kidney Stones

Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

Glomerulonephritis

Urinary Tract Cancer

Autoimmune Diseases

Therapeutic Implications

Future Perspective and Challenges

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tang, J. Microbiome in the urinary system—a review. AIMS Microbiology 2017, 3, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazen, J.E. The Enemy Within: An Investigation of the Intracellular Bacteria in Urinary Tract Infections. Washington University in St. Louis, 2022.

- Pratt, C. Modified reporting of positive urine cultures to reduce treatment of catheter-associated asymptomatic bacteriuria (CA-ASB) among inpatients: a randomized controlled trial. Memorial University of Newfoundland, 2021.

- Colella, M.; Topi, S.; Palmirotta, R.; D’Agostino, D.; Charitos, I.A.; Lovero, R.; Santacroce, L. An Overview of the Microbiota of the Human Urinary Tract in Health and Disease: Current Issues and Perspectives. Life 2023, 13, 1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirisinha, S. The potential impact of gut microbiota on your health: Current status and future challenges. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol 2016, 34, 249–264. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J.; Murphy, C.P.; Sleator, R.D.; Culligan, E.P. The urobiome, urinary tract infections, and the need for alternative therapeutics. Microbial Pathogenesis 2021, 161, 105295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duerkop, B.A.; Vaishnava, S.; Hooper, L.V. Immune responses to the microbiota at the intestinal mucosal surface. Immunity 2009, 31, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones-Freeman, B.; Chonwerawong, M.; Marcelino, V.R.; Deshpande, A.V.; Forster, S.C.; Starkey, M.R. The microbiome and host mucosal interactions in urinary tract diseases. Mucosal Immunology 2021, 14, 779–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowan-Nash, A.D.; Korry, B.J.; Mylonakis, E.; Belenky, P. Cross-domain and viral interactions in the microbiome. Microbiology Molecular Biology Reviews 2019, 83, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neugent, M.L.; Kumar, A.; Hulyalkar, N.V.; Lutz, K.C.; Nguyen, V.H.; Fuentes, J.L.; Zhang, C.; Nguyen, A.; Sharon, B.M.; Kuprasertkul, A.J.C.R.M. Recurrent urinary tract infection and estrogen shape the taxonomic ecology and function of the postmenopausal urogenital microbiome. 2022, 3.

- Kim, J.-M.; Park, Y.-J. Lactobacillus and urine microbiome in association with urinary tract infections and bacterial vaginosis. Urogenital Tract Infection 2018, 13, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marand, A.J.B.; Van Koeveringe, G.A.; Janssen, D.; Vahed, N.; Vögeli, T.-A.; Heesakkers, J.; Hajebrahimi, S.; Rahnama'i, M.S. Urinary microbiome and its correlation with disorders of the genitourinary system. 2021.

- Suarez Arbelaez, M.C.; Monshine, J.; Porto, J.G.; Shah, K.; Singh, P.K.; Roy, S.; Amin, K.; Marcovich, R.; Herrmann, T.R.; Shah, H.N. The emerging role of the urinary microbiome in benign noninfectious urological conditions: an up-to-date systematic review. World journal of urology 2023, 41, 2933–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.; Chennu, M.; Vennila, T.; Kosanam, S.; Ponsudha, P.; Suriyakrishnaan, K.; Alarfaj, A.A.; Hirad, A.H.; Sundaram, S.; Surendhar, P. Assessment of bacterial isolates from the urine specimens of urinary tract infected patient. BioMed Research International 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, F.; Huang, Z.; Yang, T.; Wang, G.; Li, P.; Yang, B.; Li, J. Pathogenesis of Proteus mirabilis in catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Urologia Internationalis 2021, 105, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulipati, S.; Babu, P.S.; Narasu, M.L.; Anusha, N. An overview on urinary tract infections and effective natural remedies. J. Med. Plants 2017, 5, 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Price, T.K.; Wolff, B.; Halverson, T.; Limeira, R.; Brubaker, L.; Dong, Q.; Mueller, E.R.; Wolfe, A.J. Temporal dynamics of the adult female lower urinary tract microbiota. MBio 2020, 11, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meštrović, T.; Matijašić, M.; Perić, M.; Čipčić Paljetak, H.; Barešić, A.; Verbanac, D. The role of gut, vaginal, and urinary microbiome in urinary tract infections: from bench to bedside. Diagnostics 2020, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawalec, A.; Zwolińska, D. Emerging role of microbiome in the prevention of urinary tract infections in children. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteside, S.A.; Razvi, H.; Dave, S.; Reid, G.; Burton, J.P. The microbiome of the urinary tract—a role beyond infection. Nature Reviews Urology 2015, 12, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neugent, M.L.; Hulyalkar, N.V.; Nguyen, V.H.; Zimmern, P.E.; De Nisco, N.J. Advances in understanding the human urinary microbiome and its potential role in urinary tract infection. MBio 2020, 11, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritzenwanker, M.; Imirzalioglu, C.; Chakraborty, T.; Wagenlehner, F.M. Modern diagnostic methods for urinary tract infections. Expert review of anti-infective therapy 2016, 14, 1047–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Deebel, N.; Casals, R.; Dutta, R.; Mirzazadeh, M. A new gold rush: a review of current and developing diagnostic tools for urinary tract infections. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasiorek, M.; Hsieh, M.H.; Forster, C.S. Utility of DNA next-generation sequencing and expanded quantitative urine culture in diagnosis and management of chronic or persistent lower urinary tract symptoms. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2019, 58, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilt, E.E.; McKinley, K.; Pearce, M.M.; Rosenfeld, A.B.; Zilliox, M.J.; Mueller, E.R.; Brubaker, L.; Gai, X.; Wolfe, A.J.; Schreckenberger, P.C. Urine is not sterile: use of enhanced urine culture techniques to detect resident bacterial flora in the adult female bladder. Journal of clinical microbiology 2014, 52, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deen, N.S.; Ahmed, A.; Tasnim, N.T.; Khan, N. Clinical relevance of expanded quantitative urine culture in health and disease. Frontiers in Cellular Infection Microbiology 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, T.K.; Dune, T.; Hilt, E.E.; Thomas-White, K.J.; Kliethermes, S.; Brincat, C.; Brubaker, L.; Wolfe, A.J.; Mueller, E.R.; Schreckenberger, P.C. The clinical urine culture: enhanced techniques improve detection of clinically relevant microorganisms. Journal of clinical microbiology 2016, 54, 1216–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ksiezarek, M.D. Comprehensive urogenital microbiome profiling: towards better understanding of female urinary tract in health and disease. 2022.

- Barraud, O.; Ravry, C.; François, B.; Daix, T.; Ploy, M.-C.; Vignon, P. Shotgun metagenomics for microbiome and resistome detection in septic patients with urinary tract infection. International journal of antimicrobial agents 2019, 54, 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regueira-Iglesias, A.; Balsa-Castro, C.; Blanco-Pintos, T.; Tomás, I. Critical review of 16S rRNA gene sequencing workflow in microbiome studies: From primer selection to advanced data analysis. Molecular Oral Microbiology 2023, 38, 347–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y. Emerging tools for uncovering genetic and transcriptomic heterogeneities in bacteria. Biophysical Reviews 2024, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, G.; Tarighat, M.A.; Jain, M.; Tendulkar, R.; Tendulkar, M.; Barwant, M. Revolutionizing Genomics: Exploring the Potential of Next-Generation Sequencing. In Advances in Bioinformatics; Springer: 2024; pp. 1–33.

- Kumar, B.; Lorusso, E.; Fosso, B.; Pesole, G. A comprehensive overview of microbiome data in the light of machine learning applications: categorization, accessibility, and future directions. Frontiers in Microbiology 2024, 15, 1343572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, A.; Li, W.; Singh, H.; Moncera, K.J.; Torralba, M.G.; Yu, Y.; Manuel, O.; Biggs, W.; Venter, J.C.; Nelson, K.E. Microbial metagenome of urinary tract infection. Scientific reports 2018, 8, 4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, N.; Srivastava, A.; Rao, A.; Murugkar, V.; Shroff, R.; Das, G. Microbiome Diagnostics and Interventions in Health and Disease. Microbiome in Human Health Disease 2021, 157–215. [Google Scholar]

- Guliciuc, M.; Porav-Hodade, D.; Mihailov, R.; Rebegea, L.-F.; Voidazan, S.T.; Ghirca, V.M.; Maier, A.C.; Marinescu, M.; Firescu, D. Exploring the Dynamic Role of Bacterial Etiology in Complicated Urinary Tract Infections. Medicina 2023, 59, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, H.G.; Groah, S.L.; Pérez-Losada, M.; Ljungberg, I.; Sprague, B.M.; Chandal, N.; Caldovic, L.; Hsieh, M. The urine microbiome of healthy men and women differs by urine collection method. International Neurourology Journal 2020, 24, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Alawi, S.H. Using culture independent approaches to gain insights into human urinary tract microbiome in healthy male and female individuals. 2021.

- Mueller, E.R.; Wolfe, A.J.; Brubaker, L. The female urinary microbiota. Current opinion in urology 2017, 27, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, M.; Koedooder, R.; Bos, M.P.; Poort, L.; Savelkoul, P.H.; Laven, J.S.; Morré, S.A.; Budding, A.E. The profiling of microbiota in vaginal and urine samples using 16s rRNA gene sequencing and IS-pro analysis. Bacterial interactions in the female genital tract 2018, 171. [Google Scholar]

- Tesei, D.; Jewczynko, A.; Lynch, A.M.; Urbaniak, C. Understanding the complexities and changes of the astronaut microbiome for successful long-duration space missions. Life 2022, 12, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouts, D.E.; Pieper, R.; Szpakowski, S.; Pohl, H.; Knoblach, S.; Suh, M.-J.; Huang, S.-T.; Ljungberg, I.; Sprague, B.M.; Lucas, S.K. Integrated next-generation sequencing of 16S rDNA and metaproteomics differentiate the healthy urine microbiome from asymptomatic bacteriuria in neuropathic bladder associated with spinal cord injury. Journal of translational medicine 2012, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, S.S.; Bavendam, T.G.; Bradway, C.K.; Conroy, B.; Dowling-Castronovo, A.; Epperson, C.N.; Hijaz, A.K.; Hsi, R.S.; Huss, K.; Kim, M. Noncancerous genitourinary conditions as a public health priority: conceptualizing the hidden burden. Urology 2022, 166, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnaswamy, P.H.; Basu, M. Urinary tract infection in gynaecology and obstetrics. Obstetrics, Gynaecology Reproductive Medicine 2020, 30, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

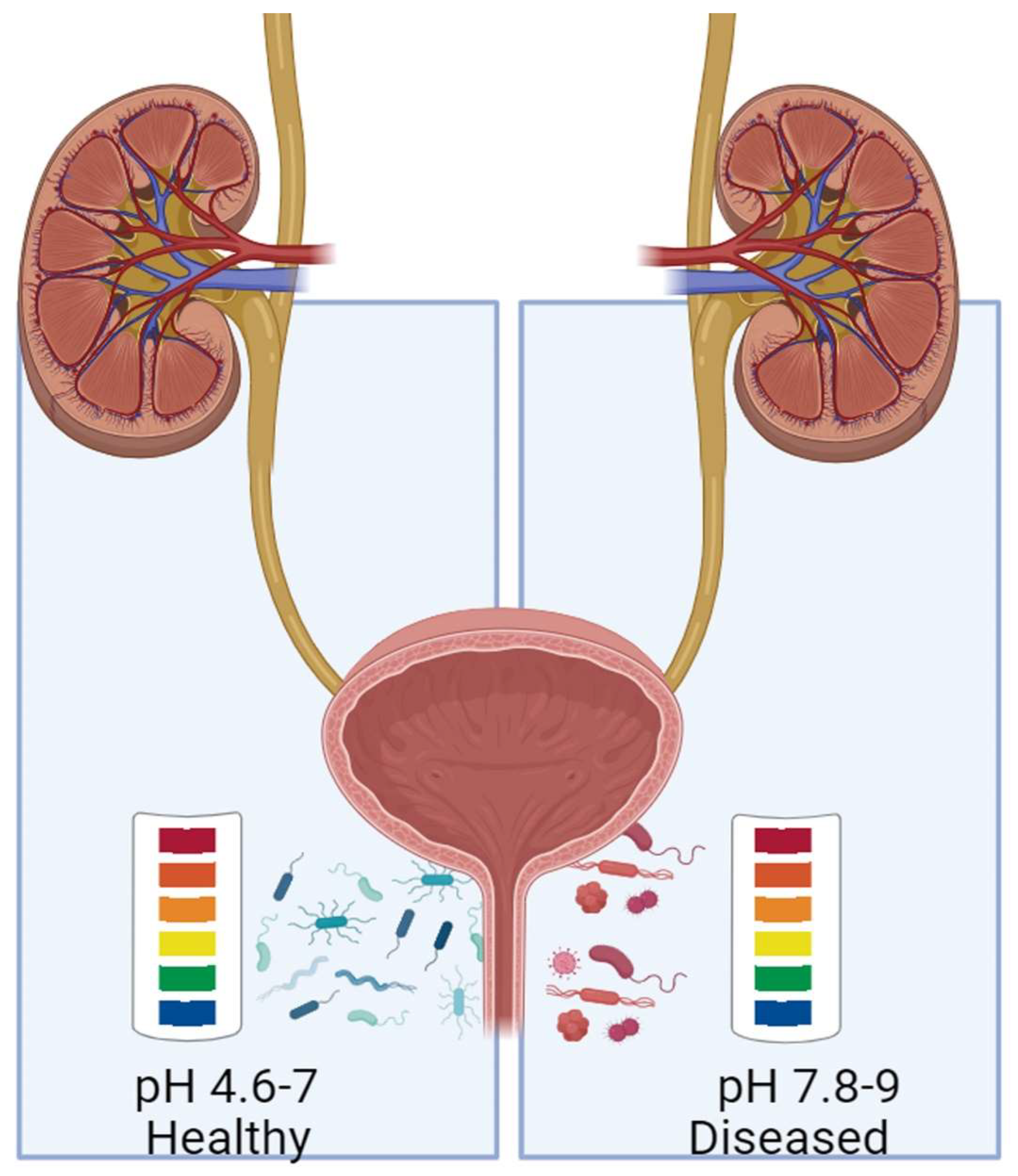

- Perez-Carrasco, V.; Soriano-Lerma, A.; Soriano, M.; Gutiérrez-Fernández, J.; Garcia-Salcedo, J.A. Urinary microbiome: yin and yang of the urinary tract. Frontiers in Cellular Infection Microbiology 2021, 11, 617002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patangia, D.V.; Anthony Ryan, C.; Dempsey, E.; Paul Ross, R.; Stanton, C. Impact of antibiotics on the human microbiome and consequences for host health. MicrobiologyOpen 2022, 11, e1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josephs-Spaulding, J.; Krogh, T.J.; Rettig, H.C.; Lyng, M.; Chkonia, M.; Waschina, S.; Graspeuntner, S.; Rupp, J.; Møller-Jensen, J.; Kaleta, C. Recurrent urinary tract infections: unraveling the complicated environment of uncomplicated rUTIs. Frontiers in Cellular Infection Microbiology 2021, 11, 562525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacerda Mariano, L.; Ingersoll, M.A. The immune response to infection in the bladder. Nature Reviews Urology 2020, 17, 439–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorić Hosman, I.; Cvitković Roić, A.; Lamot, L. A Systematic Review of the (Un) known Host Immune Response Biomarkers for Predicting Recurrence of Urinary Tract Infection. Frontiers in Medicine 2022, 9, 931717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Du, J.; Zhai, Q.; Hu, J.; Miller, A.W.; Ren, T.; Feng, Y.; Jiang, P.; Hu, L.; Sheng, J. The bladder microbiome, metabolome, cytokines, and phenotypes in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Microbiology Spectrum 2022, 10, e00212–00222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, B.O.; Flores, C.; Williams, C.; Flusberg, D.A.; Marr, E.E.; Kwiatkowska, K.M.; Charest, J.L.; Isenberg, B.C.; Rohn, J.L. Recurrent urinary tract infection: a mystery in search of better model systems. Frontiers in Cellular Infection Microbiology 2021, 11, 691210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiergeist, A.; Gessner, A. Clinical implications of the microbiome in urinary tract diseases. Current Opinion in Urology 2017, 27, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragon, I.M.; Herrera-Imbroda, B.; Queipo-Ortuño, M.I.; Castillo, E.; Del Moral, J.S.-G.; Gomez-Millan, J.; Yucel, G.; Lara, M.F. The urinary tract microbiome in health and disease. European urology focus 2018, 4, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauer-Nikonow, A.; Zimmermann, M. How the gut microbiota helps keep us vitaminized. Cell Host Microbe 2022, 30, 1063–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salazar, A.M.; Neugent, M.L.; De Nisco, N.J.; Mysorekar, I.U. Gut-bladder axis enters the stage: Implication for recurrent urinary tract infections. Cell host microbe 2022, 30, 1066–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.W.; Song, H.Y.; Kim, Y.H. The microbiome in urological diseases. Investigative Clinical Urology 2020, 61, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.W.; Chlebicki, M.P. Urinary tract infections in adults. Singapore medical journal 2016, 57, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, B.-H.; Chang, Y.-F.; Scaria, J.; Chang, C.-C.; Chou, L.-W.; Tien, N.; Wu, J.-J.; Tseng, C.-C.; Wang, M.-C.; Chang, C.-C. Identification of Escherichia coli genes associated with urinary tract infections. Journal of clinical microbiology 2012, 50, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickling, D.R.; Sun, T.T.; Wu, X.R. Anatomy and physiology of the urinary tract: relation to host defense and microbial infection. Urinary tract infections: Molecular pathogenesis clinical management.

- Yoo, J.-J.; Song, J.S.; Kim, W.B.; Yun, J.; Shin, H.B.; Jang, M.-A.; Ryu, C.B.; Kim, S.S.; Chung, J.C.; Kuk, J.C. Gardnerella vaginalis in recurrent urinary tract infection is associated with dysbiosis of the bladder microbiome. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2022, 11, 2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.W.; Lee, K.W.; Kim, Y.H. Microbiome in urological diseases: Axis crosstalk and bladder disorders. Investigative Clinical Urology 2023, 64, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guay, D.R. Contemporary management of uncomplicated urinary tract infections. Drugs 2008, 68, 1169–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, T.A.; Juthani-Mehta, M. Urinary tract infection in older adults. Aging health 2013, 9, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, N.M.; O’Brien, V.P.; Lewis, A.L. Transient microbiota exposures activate dormant Escherichia coli infection in the bladder and drive severe outcomes of recurrent disease. PLoS pathogens 2017, 13, e1006238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, V.P.; Lewis, A.L.; Gilbert, N.M. Bladder exposure to gardnerella activates host pathways necessary for Escherichia coli recurrent UTI. Frontiers in cellular infection microbiology 2021, 11, 788229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathiananthamoorthy, S. Characterisation of the urinary microbial community and its association with lower urinary tract symptoms. UCL (University College London), 2018.

- Roth, S. " Interstitial cystitis" or" bladder pain syndrome"? Aktuelle Urologie 2008, 39, 163–164. [Google Scholar]

- Abernethy, M.G.; Rosenfeld, A.; White, J.R.; Mueller, M.G.; Lewicky-Gaupp, C.; Kenton, K. Urinary microbiome and cytokine levels in women with interstitial cystitis. Obstetrics Gynecology 2017, 129, 500–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, H.; Lagesen, K.; Nederbragt, A.J.; Jeansson, S.L.; Jakobsen, K.S. Alterations of microbiota in urine from women with interstitial cystitis. BMC microbiology 2012, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abernethy, M.G.; Tsuei, A. The bladder microbiome and interstitial cystitis: is there a connection? Current Opinion in Obstetrics Gynecology 2021, 33, 469–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Tamrat, N.E.; Gao, J.; Xu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Z.; Shao, Y.; Ding, L.; Shen, B. Combined signature of the urinary microbiome and metabolome in patients with interstitial cystitis. Frontiers in Cellular Infection Microbiology 2021, 11, 711746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickel, J.C.; Stephens-Shields, A.J.; Landis, J.R.; Mullins, C.; van Bokhoven, A.; Lucia, M.S.; Henderson, J.P.; Sen, B.; Krol, J.E.; Ehrlich, G.D. A culture-independent analysis of the microbiota of female interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome participants in the MAPP research network. Journal of clinical medicine 2019, 8, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Hu, J.; Li, W.; Ma, K.; Zhang, C.; Li, K.; Yao, Y. Integrated microbiome and metabolome analysis reveals novel urinary microenvironmental signatures in interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome patients. Journal of Translational Medicine 2023, 21, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceprnja, M.; Oros, D.; Melvan, E.; Svetlicic, E.; Skrlin, J.; Barisic, K.; Starcevic, L.; Zucko, J.; Starcevic, A. Modeling of urinary microbiota associated with cystitis. Frontiers in Cellular Infection Microbiology 2021, 11, 643638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyronnet, B.; Mironska, E.; Chapple, C.; Cardozo, L.; Oelke, M.; Dmochowski, R.; Amarenco, G.; Gamé, X.; Kirby, R.; Van Der Aa, F. A comprehensive review of overactive bladder pathophysiology: on the way to tailored treatment. European urology focus 2019, 75, 988–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leron, E.; Weintraub, A.Y.; Mastrolia, S.A.; Schwarzman, P. Overactive bladder syndrome: evaluation and management. Current urology 2018, 11, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, H.; Lagesen, K.; Nederbragt, A.J.; Eri, L.M.; Jeansson, S.L.; Jakobsen, K.S. Pathogens in urine from a female patient with overactive bladder syndrome detected by culture-independent high throughput sequencing: a case report. The open microbiology journal 2014, 8, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilt, E.E.; McKinley, K.; Pearce, M.M.; Rosenfeld, A.B.; Zilliox, M.J.; Mueller, E.R.; Brubaker, L.; Gai, X.; Wolfe, A.J.; Schreckenberger, P.C. Urine is not sterile: use of enhanced urine culture techniques to detect resident bacterial flora in the adult female bladder. Journal of clinical microbiology 2014, 52, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtiss, N.; Balachandran, A.; Krska, L.; Peppiatt-Wildman, C.; Wildman, S.; Duckett, J.J. A case controlled study examining the bladder microbiome in women with Overactive Bladder (OAB) and healthy controls. European Journal of Obstetrics Gynecology Reproductive Biology 2017, 214, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Chen, C.; Zeng, J.; Wen, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhao, J.; Wu, P. Interplay between bladder microbiota and overactive bladder symptom severity: a cross-sectional study. BMC urology 2022, 22, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sze, C.; Pressler, M.; Lee, J.R.; Chughtai, B. The gut, vaginal, and urine microbiome in overactive bladder: a systematic review. International Urogynecology Journal 2022, 33, 1157–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobsen, G.E.; Amin, K. Our Knowledge of the Relationship of the Urinary Microbiome and Overactive Bladder: Past, Present, Future. Current Bladder Dysfunction Reports 2023, 18, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milsom, I.; Coyne, K.S.; Nicholson, S.; Kvasz, M.; Chen, C.-I.; Wein, A.J. Global prevalence and economic burden of urgency urinary incontinence: a systematic review. European urology focus 2014, 65, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govender, Y.; Gabriel, I.; Minassian, V.; Fichorova, R. The current evidence on the association between the urinary microbiome and urinary incontinence in women. Frontiers in cellular infection microbiology 2019, 9, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, Y.; Brown, H.W.; Brubaker, L.; Cornu, J.N.; Daly, J.O.; Cartwright, R. Urinary incontinence in women. Nature reviews Disease primers 2017, 3, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, M.M.; Hilt, E.E.; Rosenfeld, A.B.; Zilliox, M.J.; Thomas-White, K.; Fok, C.; Kliethermes, S.; Schreckenberger, P.C.; Brubaker, L.; Gai, X. The female urinary microbiome: a comparison of women with and without urgency urinary incontinence. MBio 2014, 5, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.R.; Pearle, M.S.; Robertson, W.G.; Gambaro, G.; Canales, B.K.; Doizi, S.; Traxer, O.; Tiselius, H.-G. Kidney stones. Nature reviews Disease primers 2016, 2, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çiftçioglu, N.; Björklund, M.; Kuorikoski, K.; Bergström, K.; Kajander, E.O. Nanobacteria: an infectious cause for kidney stone formation. Kidney international 1999, 56, 1893–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Deng, Q.; Liang, H. Recent advances on the mechanisms of kidney stone formation. International journal of molecular medicine 2021, 48, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryavanshi, M.V.; Bhute, S.S.; Jadhav, S.D.; Bhatia, M.S.; Gune, R.P.; Shouche, Y.S. Hyperoxaluria leads to dysbiosis and drives selective enrichment of oxalate metabolizing bacterial species in recurrent kidney stone endures. Scientific reports 2016, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bichler, K.-H.; Eipper, E.; Naber, K.; Braun, V.; Zimmermann, R.; Lahme, S. Urinary infection stones. International journal of antimicrobial agents 2002, 19, 488–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.; Huang, J.-s.; Huang, X.-j.; Peng, J.-m.; Yu, Z.; Yuan, Y.-q.; Xiao, K.-f.; Guo, J.-n. Profiling the urinary microbiome in men with calcium-based kidney stones. BMC microbiology 2020, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abratt, V.R.; Reid, S.J. Oxalate-degrading bacteria of the human gut as probiotics in the management of kidney stone disease. Advances in applied microbiology 2010, 72, 63–87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kishorebabu, A.; Sree, S.N.; Chandralekha, S.P. A Review on Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. World Journal of Current Medical Pharmaceutical Research 2019, 192–197. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.S.; Jung, S.I. The urinary tract microbiome in male genitourinary diseases: focusing on benign prostate hyperplasia and lower urinary tract symptoms. International Neurourology Journal 2021, 25, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takezawa, K.; Fujita, K.; Matsushita, M.; Motooka, D.; Hatano, K.; Banno, E.; Shimizu, N.; Takao, T.; Takada, S.; Okada, K. The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio of the human gut microbiota is associated with prostate enlargement. The Prostate 2021, 81, 1287–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, Y.; Zhou, L.; Li, C.; Liu, J.; Liu, D.; Fu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tang, J.; Zhou, L. The human microbiome and benign prostatic hyperplasia: Current understandings and clinical implications. Microbiological Research 2024, 127596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radej, S.; Szewc, M.; Maciejewski, R. Prostate infiltration by Treg and Th17 cells as an immune response to Propionibacterium acnes infection in the course of benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 8849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, K.; Takezawa, K.; Tsujimura, G.; Imanaka, T.; Kuribayashi, S.; Ueda, N.; Hatano, K.; Fukuhara, S.; Kiuchi, H.; Fujita, K. Localization and potential role of prostate microbiota. Frontiers in Cellular Infection Microbiology 2022, 12, 1048319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, P.; Malik, S.; Banerjee, A.; Datta, C.; Pal, D.K.; Ghosh, A.; Saha, A. Differential microbial signature associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer. Frontiers in Cellular Infection Microbiology 2022, 12, 894777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, S.; Samal, A.G.; Das, B.; Pradhan, B.; Sahu, N.; Mohapatra, D.; Behera, P.K.; Satpathi, P.S.; Mohanty, A.K.; Satpathi, S. Escherichia coli, a common constituent of benign prostate hyperplasia-associated microbiota induces inflammation and DNA damage in prostate epithelial cells. The Prostate 2020, 80, 1341–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajic, P.; Van Kuiken, M.E.; Burge, B.K.; Kirshenbaum, E.J.; Joyce, C.J.; Wolfe, A.J.; Branch, J.D.; Bresler, L.; Farooq, A.V. Male bladder microbiome relates to lower urinary tract symptoms. European urology focus 2020, 6, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satoskar, A.A.; Parikh, S.V.; Nadasdy, T. Epidemiology, pathogenesis, treatment and outcomes of infection-associated glomerulonephritis. Nature Reviews Nephrology 2020, 16, 32–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosquera, J.; Pedreañez, A. Acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis: analysis of the pathogenesis. International Reviews of Immunology 2021, 40, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, E.; Mansour, S.; Okafor, E.; Arrington, K.; Hong, B.-Y.; Cervantes, J. Examining the efficacy of antimicrobial therapy in preventing the development of postinfectious glomerulonephritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infectious Disease Reports 2022, 14, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, A.; Kobayashi, M.; Yamaguchi, N.; Yamagata, K.; Takano, K.; Nakajima, M.; Irie, F.; Goto, M.; Igarashi, M.; Iitsuka, T. Glomerulonephritis associated with MRSA infection: a possible role of bacterial superantigen. Kidney international 1995, 47, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casuscelli, C.; Longhitano, E.; Maressa, V.; Di Carlo, S.; Peritore, L.; Di Lorenzo, S.; Calabrese, V.; Cernaro, V.; Santoro, D. Autoimmunity and Infection in Glomerular Disease. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzvi-Behr, S.; Frishberg, Y.; Megged, O.; Weinbrand-Goichberg, J.; Becher-Cohen, R.; Terespolsky, H.; Rinat, C.; Choshen, S.; Ben-Shalom, E. Acute glomerulonephritis with concurrent suspected bacterial pneumonia–is it the tip of the iceberg? Pediatric Nephrology 2023, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrzypczyk, P.; Ofiara, A.; Zacharzewska, A.; Pańczyk-Tomaszewska, M. Acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis–immune-mediated acute kidney injury–case report and literature review. Central European Journal of Immunology 2021, 46, 516–523. [Google Scholar]

- Yacouba, A.; Alou, M.T.; Lagier, J.-C.; Dubourg, G.; Raoult, D. Urinary microbiota and bladder cancer: A systematic review and a focus on uropathogens. In Proceedings of the Seminars in Cancer Biology; 2022; pp. 875–884. [Google Scholar]

- Karam, A.; Mjaess, G.; Albisinni, S.; El Daccache, Y.; Farah, M.; Daou, S.; Kazzi, H.; Hassoun, R.; Bou Kheir, G.; Aoun, F. Uncovering the role of urinary microbiota in urological tumors: a systematic review of literature. World Journal of Urology 2022, 40, 951–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Karawi, A.S.; Abid, F.M.; Mustafa, A.; Abdulla, M. Revealing the Urinary Microbiota in Prostate Cancer: A Comprehensive Review Unveiling Insights into Pathogenesis and Clinical Application. Al-Salam Journal for Medical Science 2024, 3, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, K.-Y.; Wu, D.-C.; Wu, W.-J.; Wang, J.-W.; Juan, Y.-S.; Li, C.-C.; Liu, C.-J.; Lee, H.-Y. Exploring the association between gut and urine microbiota and prostatic disease including benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer using 16S rRNA sequencing. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Kanwar, S.S. The influence of dysbiosis on kidney stones that risk up renal cell carcinoma (RCC). In Proceedings of the Seminars in cancer biology; 2021; pp. 134–138. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, P.; Zhang, G.; Zhao, J.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Huang, W.; Zhong, J.; Zeng, J. Profiling the urinary microbiota in male patients with bladder cancer in China. Frontiers in cellular infection microbiology 2018, 8, 167. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, A.; Imtiaz, S.; Riaz, S. Study of Urinary Tract Infection in Patients Suffering from Cancer. Journal of Cancer Research Reviews Reports 2020, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidler, S.; Lusuardi, L.; Madersbacher, S.; Freibauer, C. The microbiome in benign renal tissue and in renal cell carcinoma. Urologia internationalis 2020, 104, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, H.; Tian, Y.; Song, C.; Li, J.; Liu, T.; Chen, Z.; Chen, C.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Urinary microbiota–a potential biomarker and therapeutic target for bladder cancer. Journal of medical microbiology 2019, 68, 1471–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajic, P.; Wolfe, A.J.; Gupta, G.N. The urinary microbiome: implications in bladder cancer pathogenesis and therapeutics. Urology 2019, 126, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, V.; Choi, H.W. The urinary microbiome: role in bladder cancer and treatment. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reggiani, F.; L'Imperio, V.; Calatroni, M.; Pagni, F.; Sinico, R.A. Goodpasture syndrome and anti-glomerular basement membrane disease. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2023, 41, 964–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesualdo, L.; Di Leo, V.; Coppo, R. The mucosal immune system and IgA nephropathy. Semin Immunopathol 2021, 43, 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, S.; Nakatomi, Y.; Odani, S.; Sato, H.; Gejyo, F.; Arakawa, M.J.C.; Immunology, E. Circulating IgA, IgG, and IgM class antibody against Haemophilus parainfluenzae antigens in patients with IgA nephropathy. 1996, 104, 306–311.

- Sugino, H.; Sawada, Y.; Nakamura, M.J.I.j.o.m.s. IgA vasculitis: etiology, treatment, biomarkers and epigenetic changes. 2021, 22, 7538.

- Keri, K.C.; Blumenthal, S.; Kulkarni, V.; Beck, L.; Chongkrairatanakul, T. Primary membranous nephropathy: comprehensive review and historical perspective. Postgrad Med J 2019, 95, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almaani, S.; Meara, A.; Rovin, B.H. Update on Lupus Nephritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017, 12, 825–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, S.; Higgins, R.M. Interstitial nephritis. Postgrad Med J 1997, 73, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcu, I.; Campian, E.C.; Tu, F.F. Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome. Semin Reprod Med 2018, 36, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsen, T.H.; Folseraas, T.; Thorburn, D.; Vesterhus, M. Primary sclerosing cholangitis - a comprehensive review. J Hepatol 2017, 67, 1298–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, L.A.; Ahlstedt, S.; Fasth, A.; Hagberg, M.; Kaijser, B.; Mattsby-Baltzer, I.; Svanborg-Eden, C. Immunological aspects of pyelonephritis. Contrib Nephrol 1979, 16, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifai, A.O.; Denig, K.M.; Caza, T.; Webb, S.M.; Rifai, S.; Khan, S.; Dahan, S.; Alamin, S.J.C.R.i.N. Antitubular Basement Membrane Antibody Disease Associated with Nivolumab Infusion and Concomitant Acute Pyelonephritis Leading to Acute Kidney Injury: a Case Report and Literature Review. 2023, 2023.

- Lu, J.C.; Shen, J.M.; Hu, X.C.; Peng, L.P.; Hong, Z.W.; Yao, B. Identification and preliminary study of immunogens involved in autoimmune prostatitis in human males. Prostate 2018. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyun, M.; Lee, J.Y.; Lim, K.R.; Kim, H.a. Clinical Characteristics of Uncomplicated Acute Pyelonephritis Caused by Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infectious Diseases Therapy 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirillo, E.; Palmirotta, R.; Colella, M.; Santacroce, L. A Bird’s-Eye View of the Pathophysiologic Role of the Human Urobiota in Health and Disease: Can We Modulate It? Pathophysiology 2024, 31, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, K.; Lewis, A. (UTI-0012-2012). Gram-positive uropathogens, polymicrobial urinary tract infection, and the emerging microbiota of the urinary tract. Microbiol Spectr 4: UTI-0012-2012: 2016. [CrossRef]

- Alteri, C.J.; Himpsl, S.D.; Mobley, H.L. Preferential use of central metabolism in vivo reveals a nutritional basis for polymicrobial infection. PLoS pathogens 2015, 11, e1004601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keogh, D.; Tay, W.H.; Ho, Y.Y.; Dale, J.L.; Chen, S.; Umashankar, S.; Williams, R.B.; Chen, S.L.; Dunny, G.M.; Kline, K.A.J.C.h.; et al. Enterococcal metabolite cues facilitate interspecies niche modulation and polymicrobial infection. 2016, 20, 493–503.

- Li, Q.; Lin, X.; Wu, Z.; He, L.; Wang, W.; Cao, Q.; Zhang, J.J.S.J.o.K.D. ; Transplantation. Immuno-histochemistry analysis of Helicobacter pylori antigen in renal biopsy specimens from patients with glomerulonephritis. 2013, 24, 751–758. [Google Scholar]

- Ogura, Y.; Suzuki, S.; Shirakawa, T.; Masuda, M.; Nakamura, H.; Iijima, K.; Yoshikawa, N. Haemophilus parainfluenzae antigen and antibody in children with IgA nephropathy and Henoch-Schönlein nephritis. American journal of kidney diseases 2000, 36, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masuda, M.; Nakanishi, K.; Yoshizawa, N.; Iijima, K.; Yoshikawa, N. Group A streptococcal antigen in the glomeruli of children with Henoch-Schönlein nephritis. American journal of kidney diseases 2003, 41, 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, R.; Carlsson, F.; Mörgelin, M.; Tati, R.; Lindahl, G.; Karpman, D.J.T.A.j.o.p. Tissue deposits of IgA-binding streptococcal M proteins in IgA nephropathy and Henoch-Schönlein purpura. 2010, 176, 608–618.

- Kronbichler, A.; Kerschbaum, J.; Mayer, G. The influence and role of microbial factors in autoimmune kidney diseases: a systematic review. Journal of Immunology Research 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, I.B.; Kuzmin, M.D.; Gritsenko, V.A.J.I.j.o.a. Microflora of the seminal fluid of healthy men and men suffering from chronic prostatitis syndrome. 2009, 32, 462–467.

- Nickel, J.C.; Stephens, A.; Landis, J.R.; Chen, J.; Mullins, C.; van Bokhoven, A.; Lucia, M.S.; Melton-Kreft, R.; Ehrlich, G.D.; urology, M.R.N.J.T.J.o. Search for microorganisms in men with urologic chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a culture-independent analysis in the MAPP research network. 2015, 194, 127–135.

- Shoskes, D.A.; Altemus, J.; Polackwich, A.S.; Tucky, B.; Wang, H.; Eng, C.J.U. The urinary microbiome differs significantly between patients with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome and controls as well as between patients with different clinical phenotypes. 2016, 92, 26–32.

- Mändar, R.; Punab, M.; Korrovits, P.; Türk, S.; Ausmees, K.; Lapp, E.; Preem, J.K.; Oopkaup, K.; Salumets, A.; Truu, J.J.I.J.o.U. Seminal microbiome in men with and without prostatitis. 2017, 24, 211–216.

- Miyake, M.; Tatsumi, Y.; Ohnishi, K.; Fujii, T.; Nakai, Y.; Tanaka, N.; Fujimoto, K.J.P.I. Prostate diseases and microbiome in the prostate, gut, and urine. 2022, 10, 96–107.

- Venturini, S.; Reffo, I.; Avolio, M.; Basaglia, G.; Del Fabro, G.; Callegari, A.; Tonizzo, M.; Sabena, A.; Rondinella, S.; Mancini, W. The management of recurrent urinary tract infection: non-antibiotic bundle treatment. Probiotics Antimicrobial Proteins 2023, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessoa, W.F.B.; Melgaço, A.C.C.; Almeida, M.E.; Santos, T.F.; Romano, C.C. Probiotics for urinary tract disease prevention and treatment. In Probiotics for Human Nutrition in Health and Disease; Elsevier: 2022; pp. 513–536.

- Ahmed, R.A.; Kamal, L.D.; Ahmed, H.S. The mechanisms of Lactobacillus activities: Probiotic importance of Lactobacillus species. Egyptian Academic Journal of Biological Sciences, E. Medical Entomology Parasitology 2021, 13, 45–63. [Google Scholar]

- Iannitti, T.; Palmieri, B. Therapeutical use of probiotic formulations in clinical practice. Clinical nutrition 2010, 29, 701–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stapleton, A.E.; Au-Yeung, M.; Hooton, T.M.; Fredricks, D.N.; Roberts, P.L.; Czaja, C.A.; Yarova-Yarovaya, Y.; Fiedler, T.; Cox, M.; Stamm, W.E. Randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial of a Lactobacillus crispatus probiotic given intravaginally for prevention of recurrent urinary tract infection. Clinical infectious diseases 2011, 52, 1212–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M.; Yousefifard, M.; Ataei, N.; Oraii, A.; Razaz, J.M.; Izadi, A.J. The efficacy of probiotics in prevention of urinary tract infection in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of pediatric urology 2017, 13, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New, F.J.; Theivendrampillai, S.; Juliebø-Jones, P.; Somani, B. Role of probiotics for recurrent UTIs in the twenty-first century: a systematic review of literature. Current urology reports 2022, 23, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniel, M.; Szymanik-Grzelak, H.; Turczyn, A.; Pańczyk-Tomaszewska, M. Lactobacillus rhamnosus PL1 and Lactobacillus plantarum PM1 versus placebo as a prophylaxis for recurrence urinary tract infections in children: a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMC urology 2020, 20, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meena, J.; Thomas, C.C.; Kumar, J.; Raut, S.; Hari, P. Non-antibiotic interventions for prevention of urinary tract infections in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. European Journal of Pediatrics 2021, 180, 3535–3545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Ameeruddin, S. Probiotics in common urological conditions: A narrative review. Longhua Chin. Med 2022, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazly Bazzaz, B.S.; Darvishi Fork, S.; Ahmadi, R.; Khameneh, B. Deep insights into urinary tract infections and effective natural remedies. African Journal of Urology 2021, 27, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayivi, R.D.; Gyawali, R.; Krastanov, A.; Aljaloud, S.O.; Worku, M.; Tahergorabi, R.; Silva, R.C.d.; Ibrahim, S.A. Lactic acid bacteria: Food safety and human health applications. Dairy 2020, 1, 202–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voidarou, C.; Alexopoulos, A.; Tsinas, A.; Rozos, G.; Tzora, A.; Skoufos, I.; Varzakas, T.; Bezirtzoglou, E. Effectiveness of bacteriocin-producing lactic acid bacteria and bifidobacterium isolated from honeycombs against spoilage microorganisms and pathogens isolated from fruits and vegetables. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 7309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.H.; Kim, Y.H.; Naskar, M.; Hayes, B.W.; Abraham, M.A.; Noh, J.H.; Suk, G.; Kim, M.J.; Cho, K.S.; Shin, M. Lactobacillus crispatus limits bladder uropathogenic E. coli infection by triggering a host type I interferon response. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2022, 119, e2117904119. [Google Scholar]

- Zagaglia, C.; Ammendolia, M.G.; Maurizi, L.; Nicoletti, M.; Longhi, C. Urinary tract infections caused by uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains—new strategies for an old pathogen. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, M.; Aleya, S.; Alsubih, M.; Aleya, L. Microbiome Dynamics: A Paradigm Shift in Combatting Infectious Diseases. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2024, 14, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, L.; de Dios Ruiz-Rosado, J.; Stonebrook, E.; Becknell, B.; Spencer, J.D. Uropathogen and host responses in pyelonephritis. Nature Reviews Nephrology 2023, 19, 658–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenneally, C.; Murphy, C.P.; Sleator, R.D.; Culligan, E.P. The urinary microbiome and biological therapeutics: Novel therapies for urinary tract infections. Microbiological Research 2022, 259, 127010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulsalam, A.A.; Saleh, M.K. Effect of colicin from E. coli product on some species of gram-negative bacteria isolated from Urinary Tract infections. Journal of Education Scientific Studies.

- Roy, S.M.; Riley, M.A. Evaluation of the potential of colicins to prevent extraluminal contamination of urinary catheters by Escherichia coli. International journal of antimicrobial agents 2019, 54, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, J.; Wu, N.; Zeng, Y.; Chen, L.; Li, L.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, M.; Li, L.; Li, J. Non-active antibiotic and bacteriophage synergism to successfully treat recurrent urinary tract infection caused by extensively drug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Emerging microbes infections 2020, 9, 771–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zalewska-Piątek, B.; Piątek, R. Phage therapy as a novel strategy in the treatment of urinary tract infections caused by E. coli. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González de Llano, D.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V.; Bartolomé, B. Cranberry polyphenols and prevention against urinary tract infections: relevant considerations. Molecules 2020, 25, 3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amábile-Cuevas, C.F. Ascorbate and Antibiotics, at Concentrations Attainable in Urine, Can Inhibit the Growth of Resistant Strains of Escherichia coli Cultured in Synthetic Human Urine. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

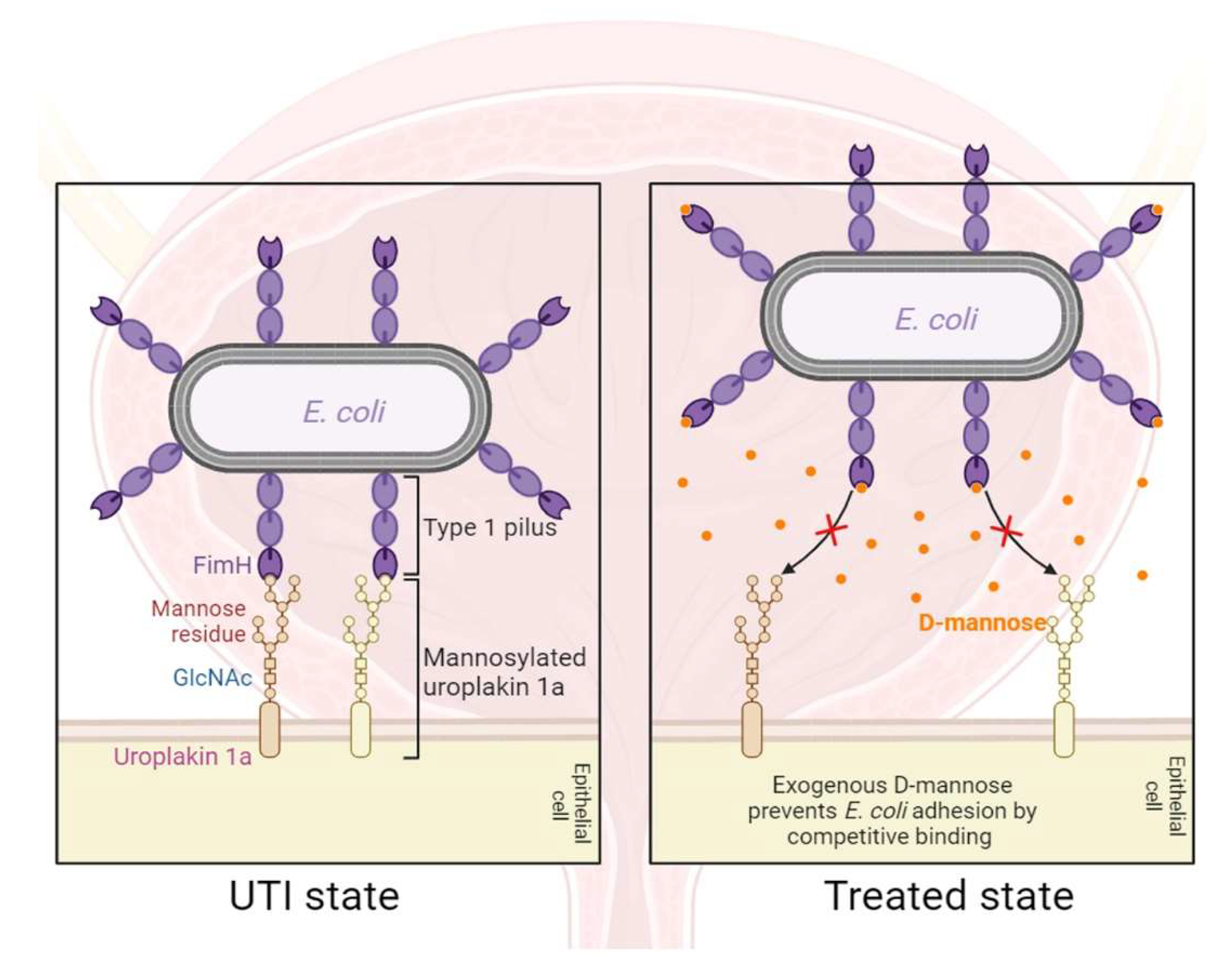

- Pani, A.; Valeria, L.; Dugnani, S.; Senatore, M.; Scaglione, F. Pharmacodynamics of D-mannose in the prevention of recurrent urinary infections. Journal of Chemotherapy 2022, 34, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ala-Jaakkola, R.; Laitila, A.; Ouwehand, A.C.; Lehtoranta, L. Role of D-mannose in urinary tract infections–a narrative review. Nutrition journal 2022, 21, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Autoimmune disease | Primary organ/body part affected | Autoantibodies | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Goodpasture syndrome | Kidneys, lungs | Anti-GBM antibodies | [121] |

| IgA nephropathy | Kidneys | IgA autoantibodies, anti-OMHP antibodies | [122,123] |

| IgA vasculitis | Kidneys, lungs | IgA1 autoantibody | [124] |

| Membranous nephropathy | Kidneys | Anti-PLA2R antibodies | [125] |

| Lupus nephritis | Kidneys | Anti-dsDNA, Anti-Sm, Anti-nuclear antibodies | [126] |

| Interstitial nephritis | Kidneys | Various autoantibodies | [127] |

| Interstitial cystitis | Bladder | Anti-urothelial and anti-nuclear antibodies | [128] |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | Bile ducts, can affect gallbladder | ANCA, Anti-mitochondrial antibodies | [129] |

| Pyelonephritis | kidney | Tamm-Horsfall protein antibodies, Tubulointerstitial nephritis antigen protein antibody | [130,131] |

| Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis | kidney | - | - |

| Prostatitis | Prostate gland | Prostate tissue immunodominant antigen (HPTIAs) protein antibodies | [132] |

| # | Name | Status | NCT ID | Phase | Drugs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lactobacillus Probiotic for Prevention of UTI | Completed | NCT03151967 | Phase 2, Phase 3 | Lactobacillus crispatus CTV-05; Placebo |

| 2 | Targeted Pathogen Replacement With Novel Probiotic Treatment for Prevention of Recurrent UTIs in Children | Completed | NCT01696227 | - | Nissle 1917 |

| 3 | Observational Study Evaluating the Number of Symptomatic Cystitis-like Episodes and Urinary Comfort of Women Consuming Cranberry, Cinnamon and Probiotic Strain Extracts | Completed | NCT04987164 | - | Cranberry, Cinnamon, Probiotics |

| 4 | Probiotic and Effects on Multi-Drug Resistant Urinary Tract Infection | Completed | NCT03644966 | - | Bifidobacterium infantis, Antibiotics |

| 5 | A Double-blinded, Randomized, Placebo-controlled, Parallel-group Study Evaluating the Effect of the Probiotic on Recurrent Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) in Adult Women Recently Treated for UTI. | Completed | NCT03366077 | - | Probiotic (name not mentioned) |

| 6 | Preventing Urinary Tract Infections in Infants and Young Children With Probiotic E. Coli Nissle: | Recruiting | NCT04608851 | Phase 4 | E. coli Nissle |

| 7 | A Novel Probiotic-antibiotic Combination to Prevent Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections | Recruiting | NCT06149676 | Early Phase 1 | Saccharomyces Boulardii 250 MG [Florastor] |

| 8 | Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Study to Evaluate the Effect of a Probiotic on the Urinary Tract Microbiota in Women With Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections (rUTI). | Recruiting | NCT05895578 | - | Probiotic (name not mentioned) and antibiotic |

| 9 | A Clinical Trial to Determine the Extent to Which Probiotic Therapy Reduces Side Effects of Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Pediatric Neurogenic Bladder Patients With a History of Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections | Unknown status | NCT02044965 | Phase 1, Phase 2 | Trimethoprim; sulfamethoxazole; L. rhamnosus GR-1 and L. reuteri RC-14 |

| 10 | Probiotics/Lactobacillus as a Prophylactic Aid in Recurrent Bacterial Cystitis in Women. A Randomized, Prospective, Double-Blinded, Placebo Controlled, Multi-Center Study. | Unknown status | NCT00781625 | - | UREX-Cap-5 (Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1, Lactobacillus reuteri RC-14) |

| 11 | Effectiveness of Prophylaxis of Urinary Tract Infections in Children With a Probiotic Containing Lactobacillus Rhamnosus PL1 and Lactobacillus Plantarum PM1, a Randomised Clinical Trial | Unknown status | NCT03462160 | - | Lactobacillus Rhamnosus PL1 and Lactobacillus Plantarum PM1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).