Submitted:

29 October 2024

Posted:

30 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Mathematical Model

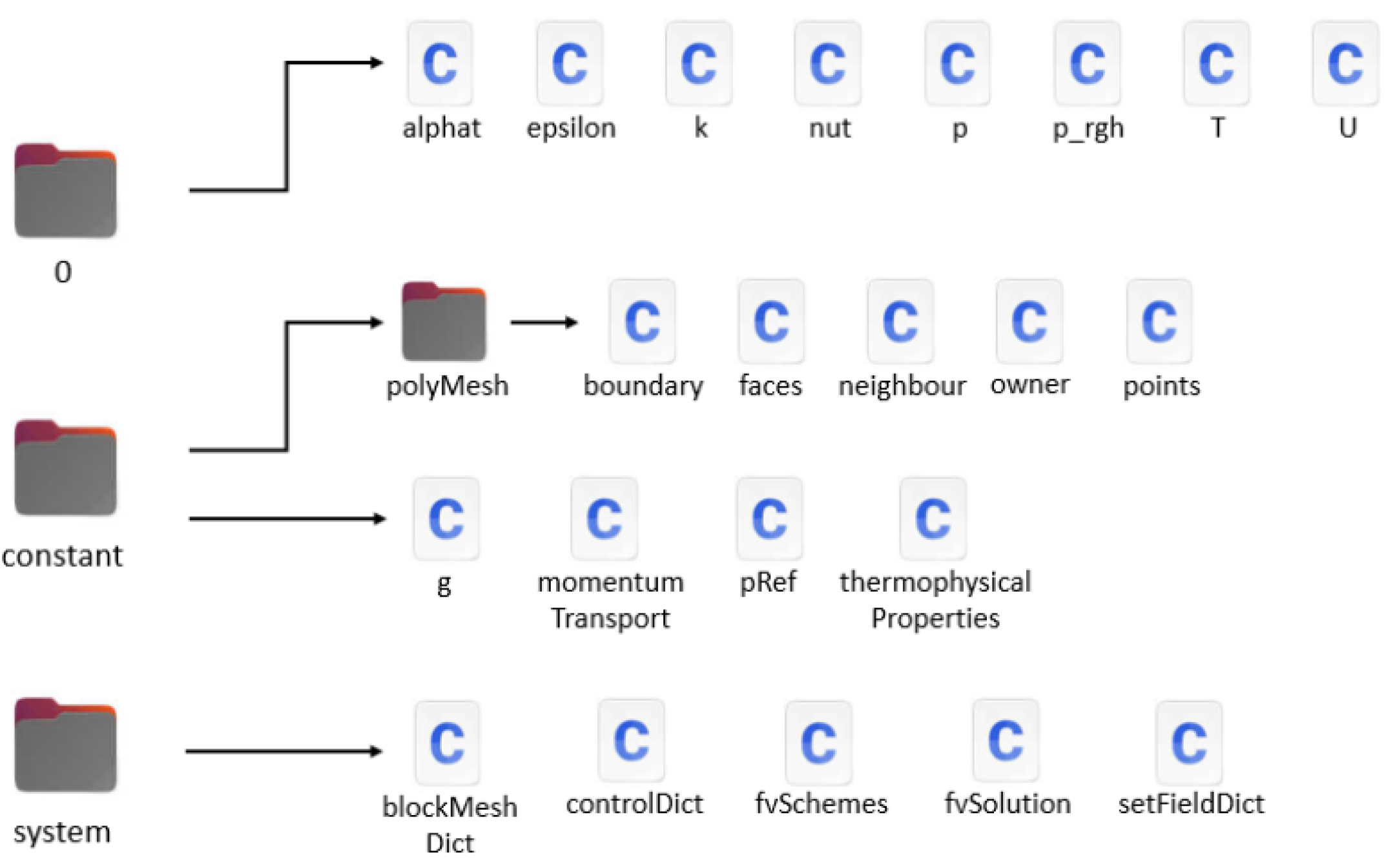

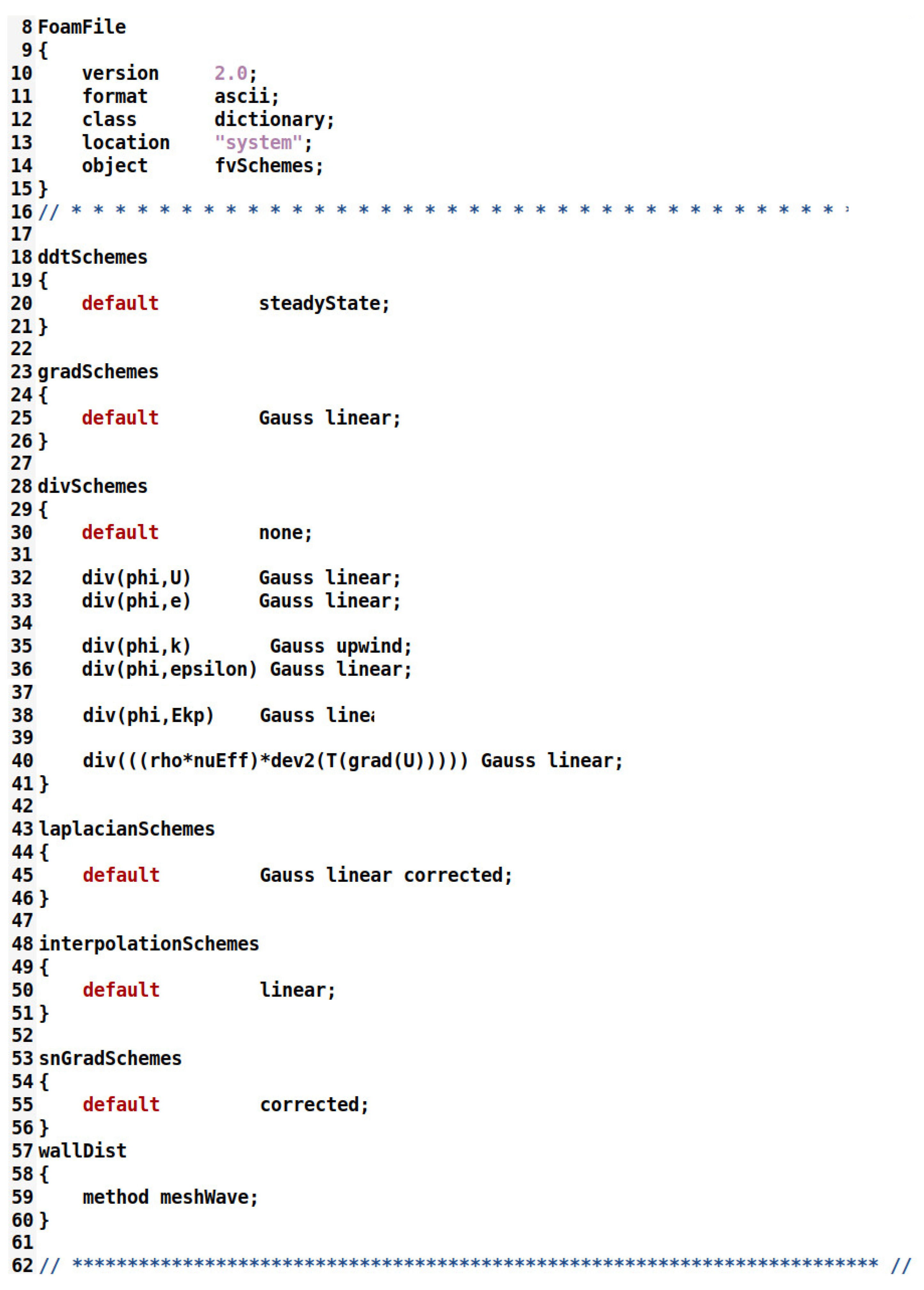

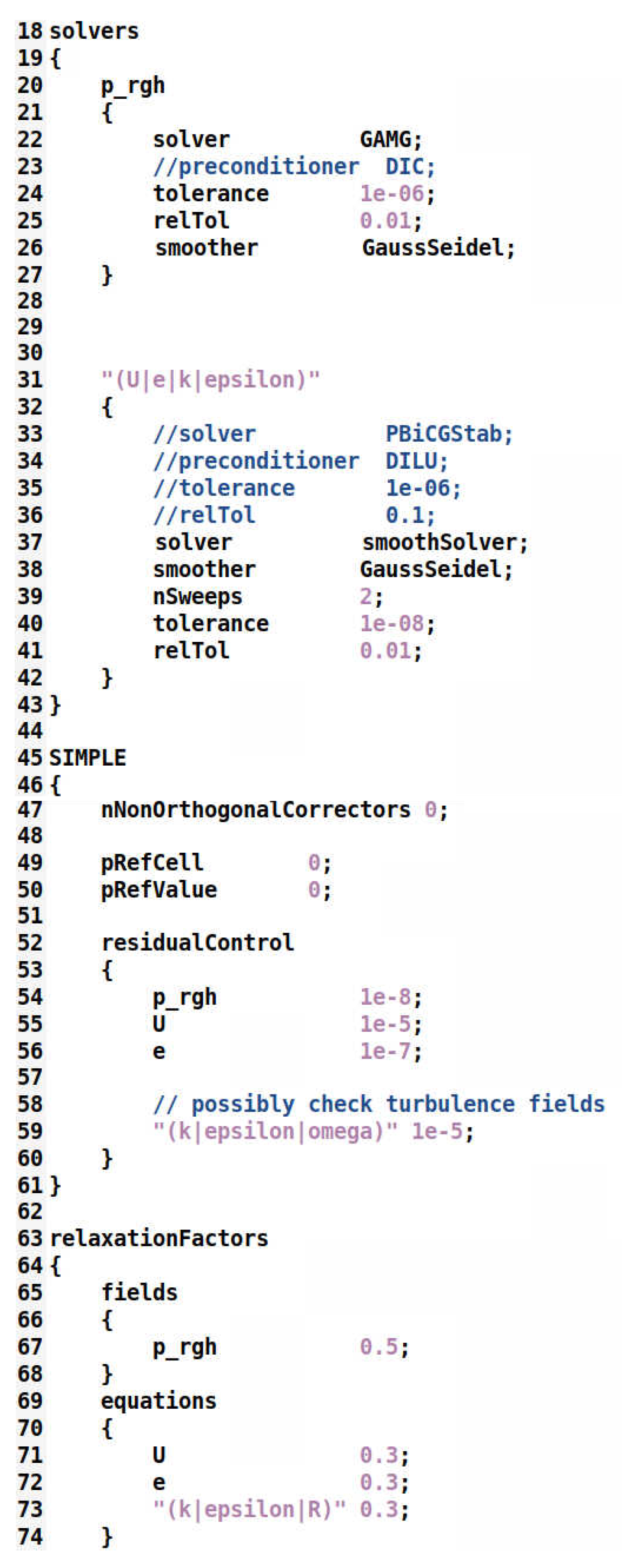

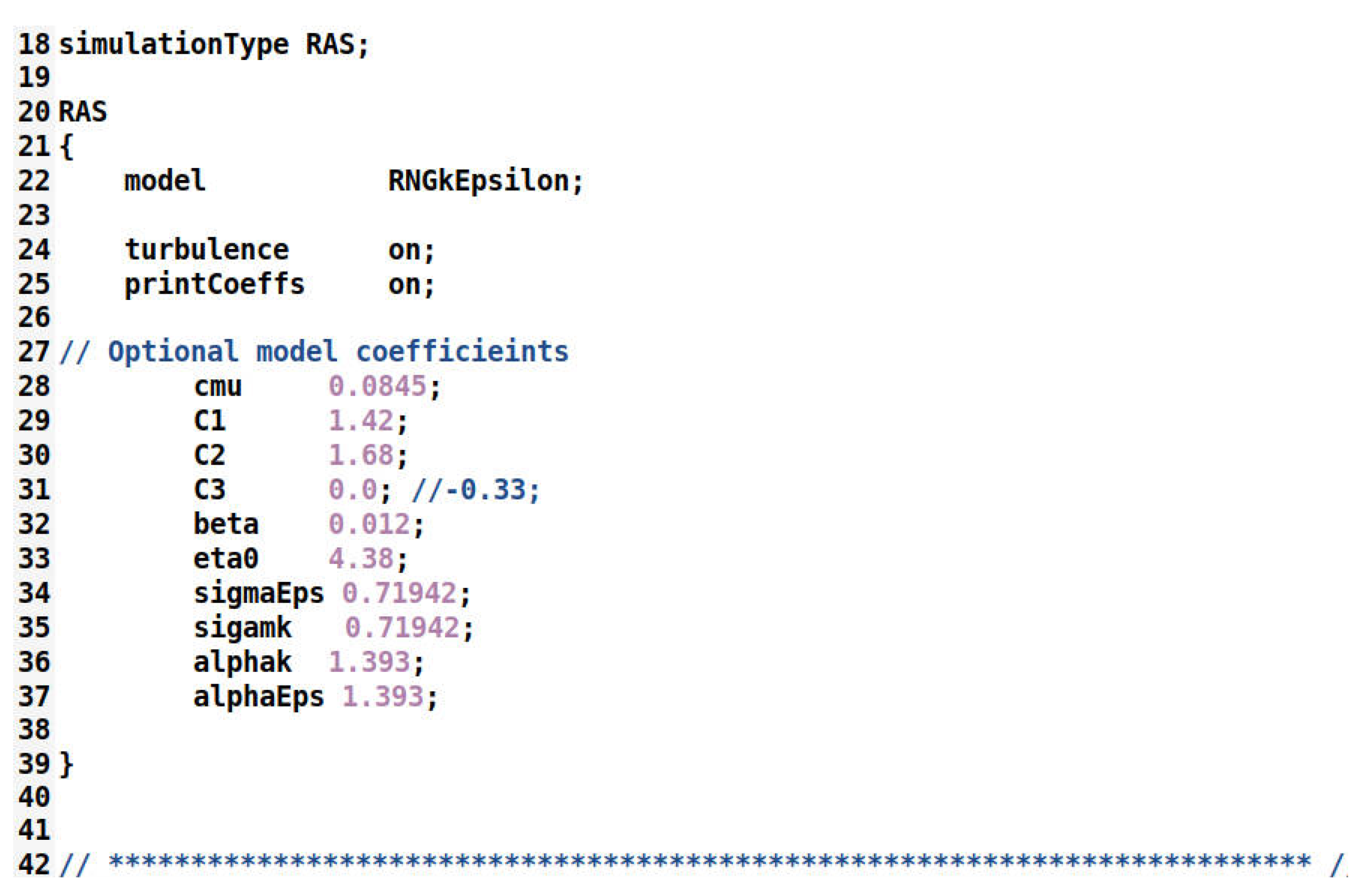

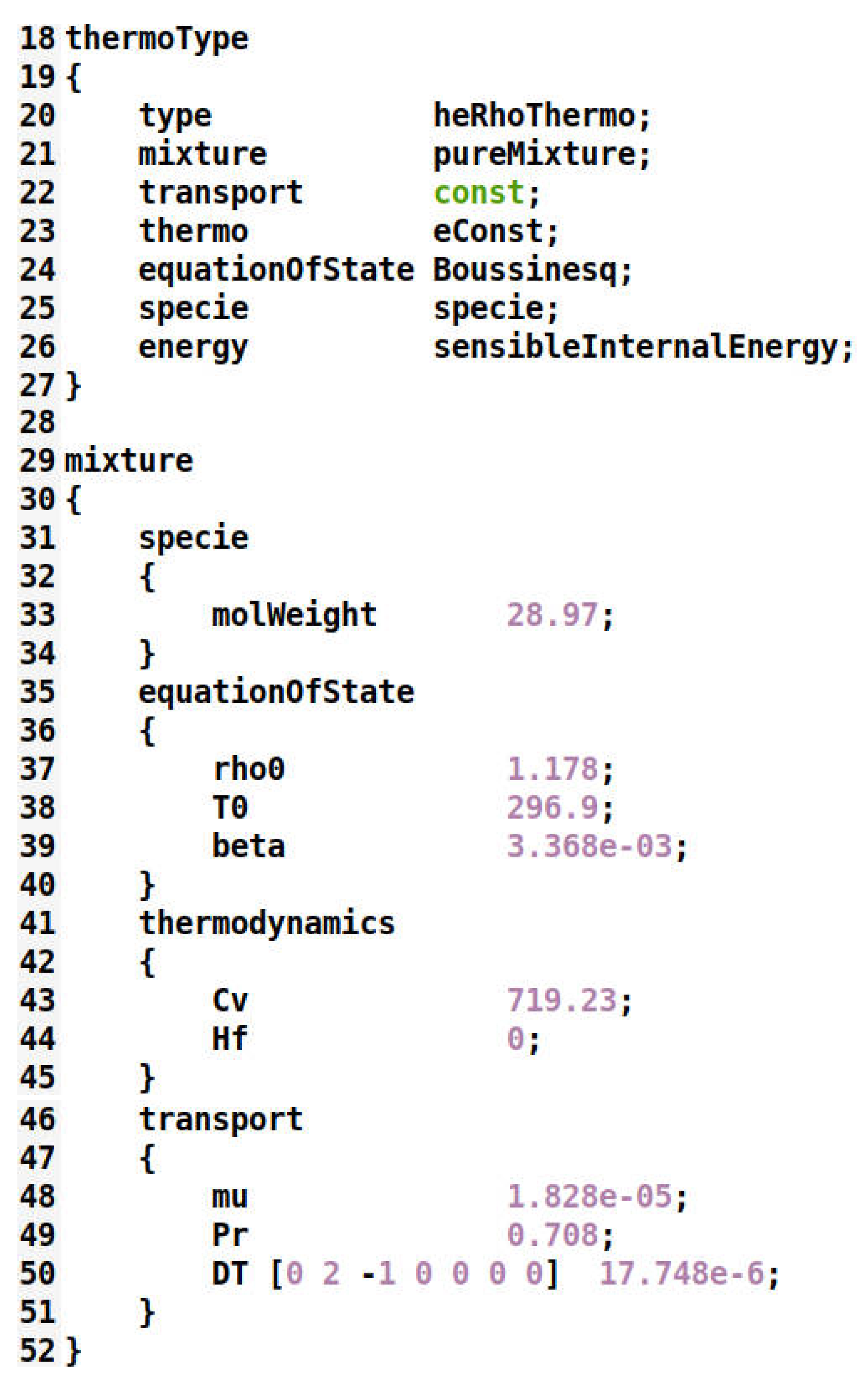

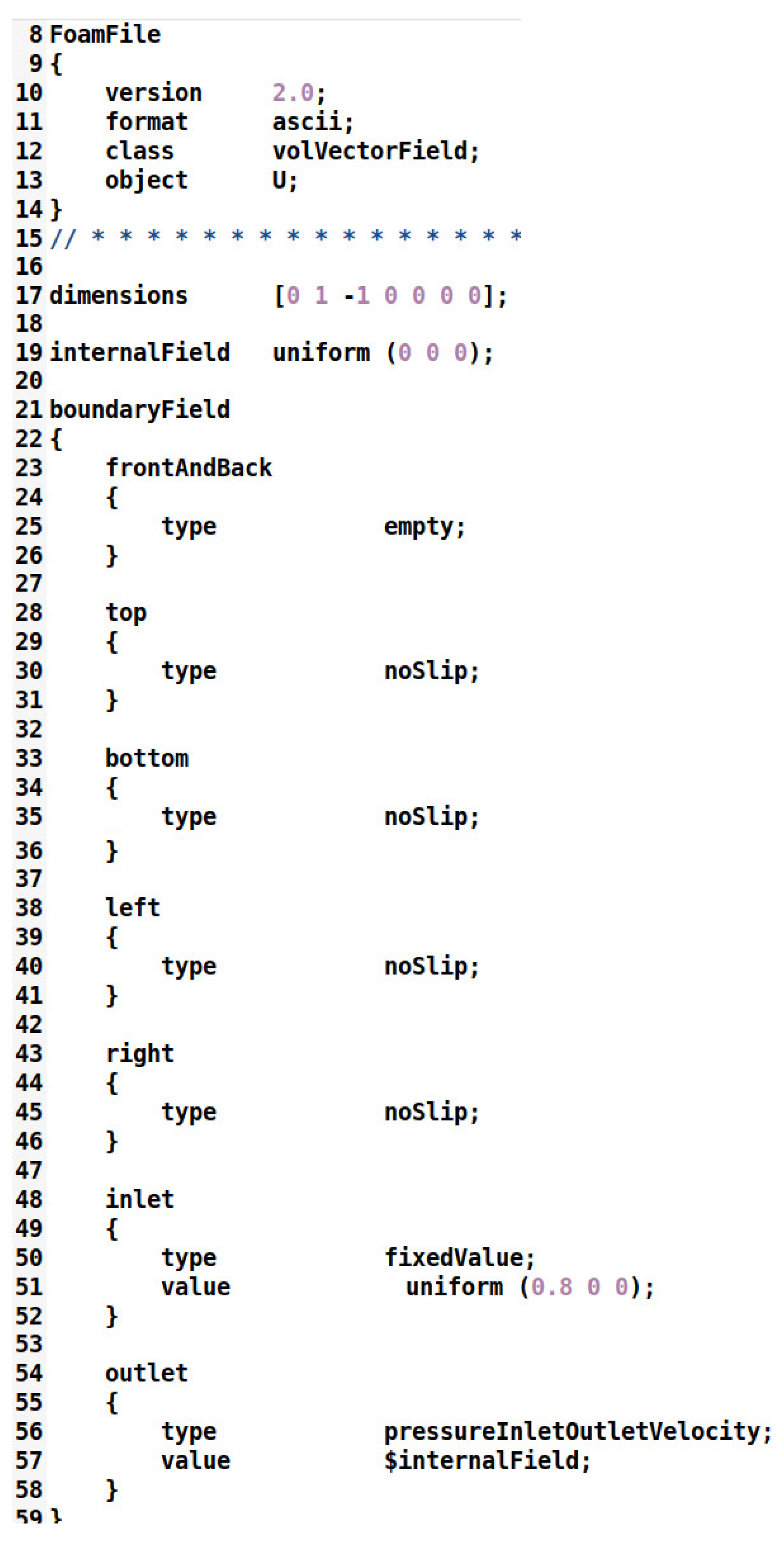

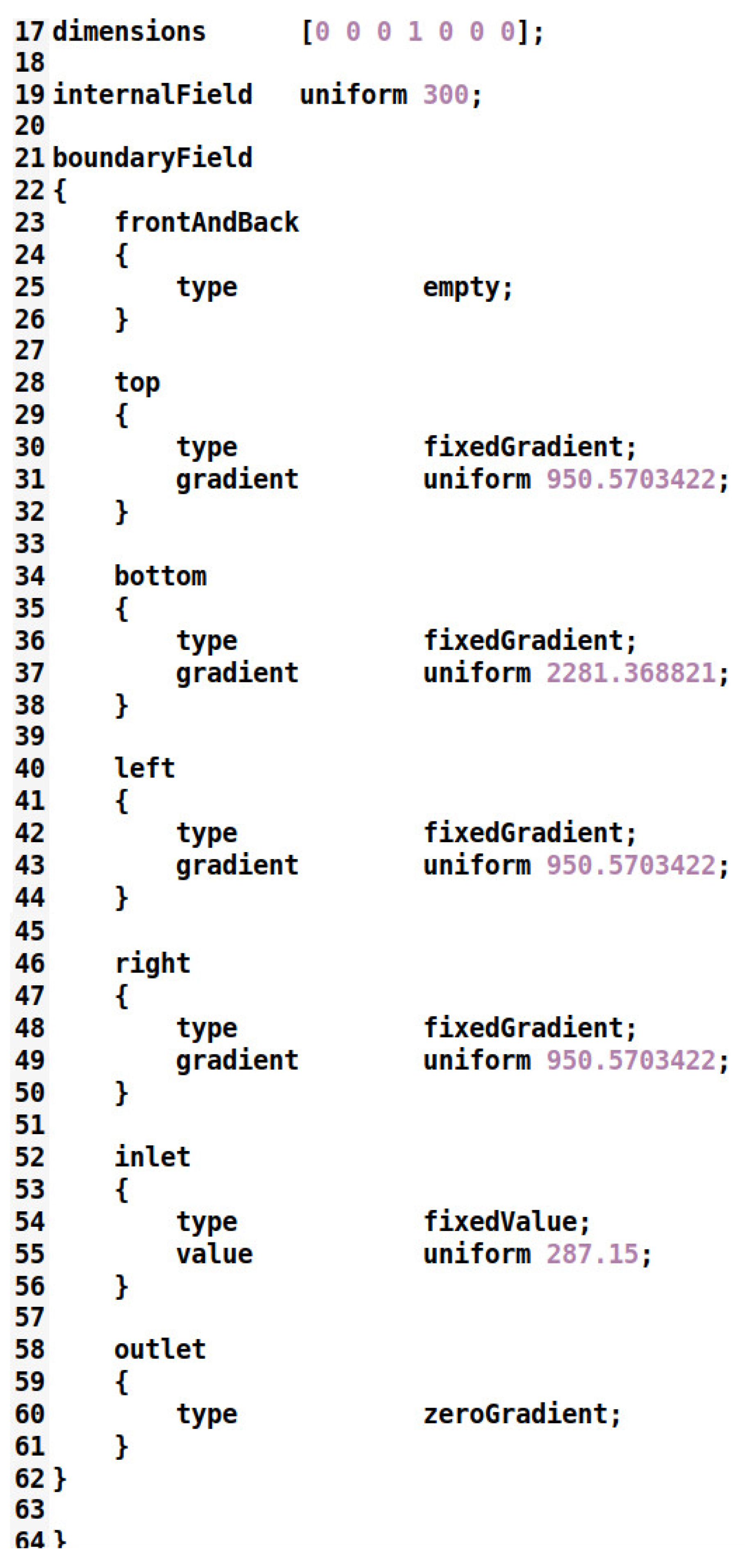

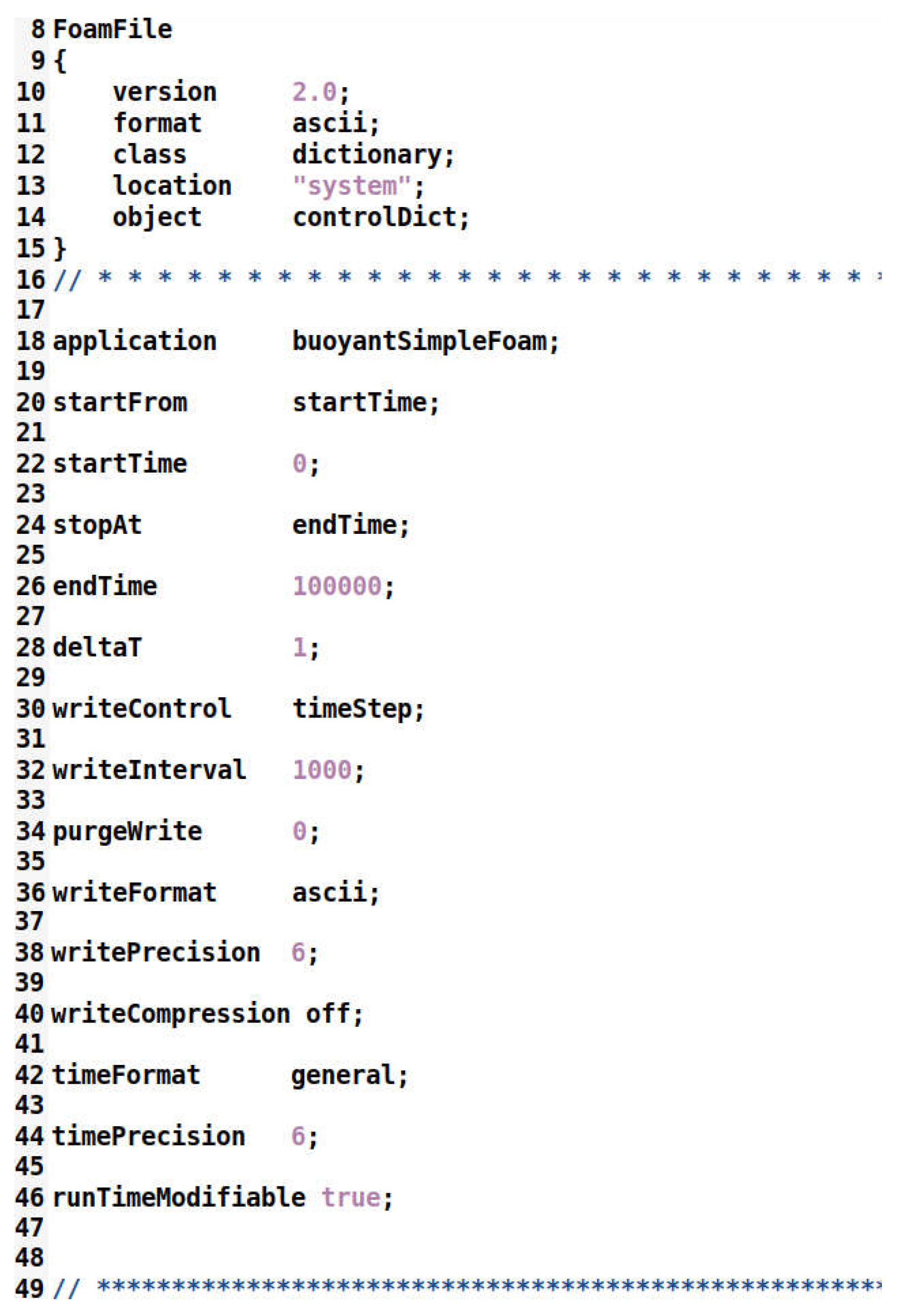

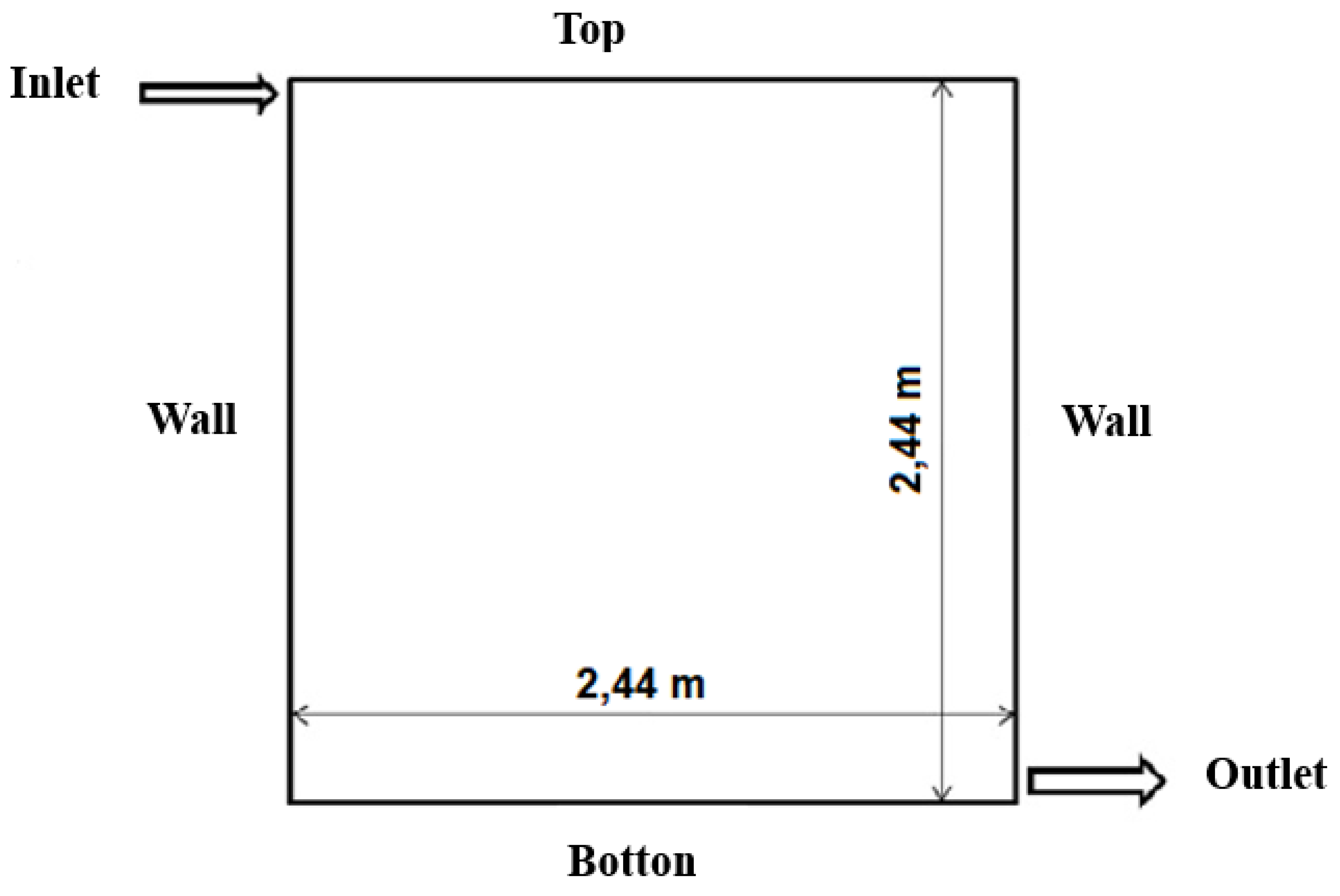

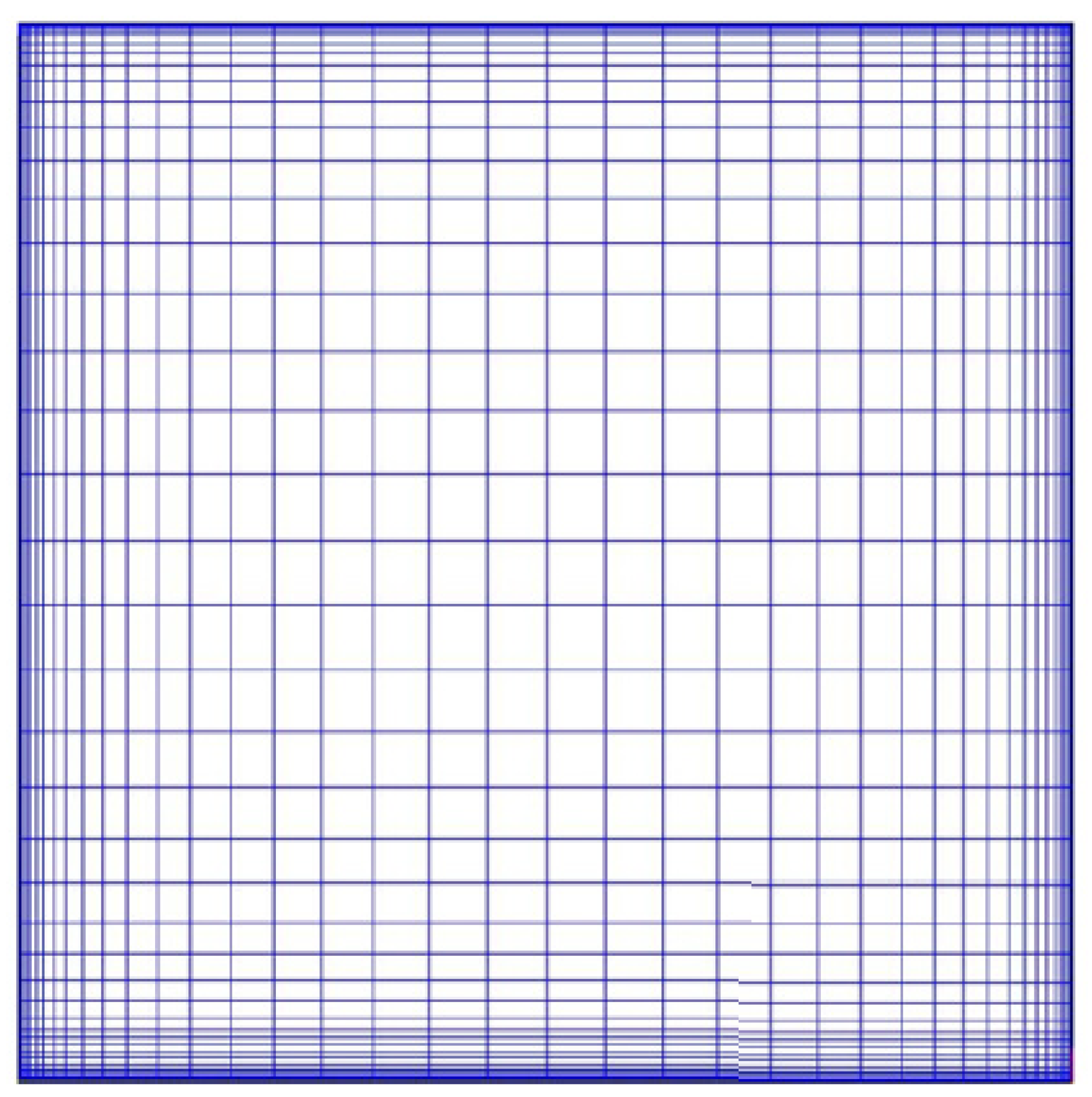

2.1. OpenFOAM Setup

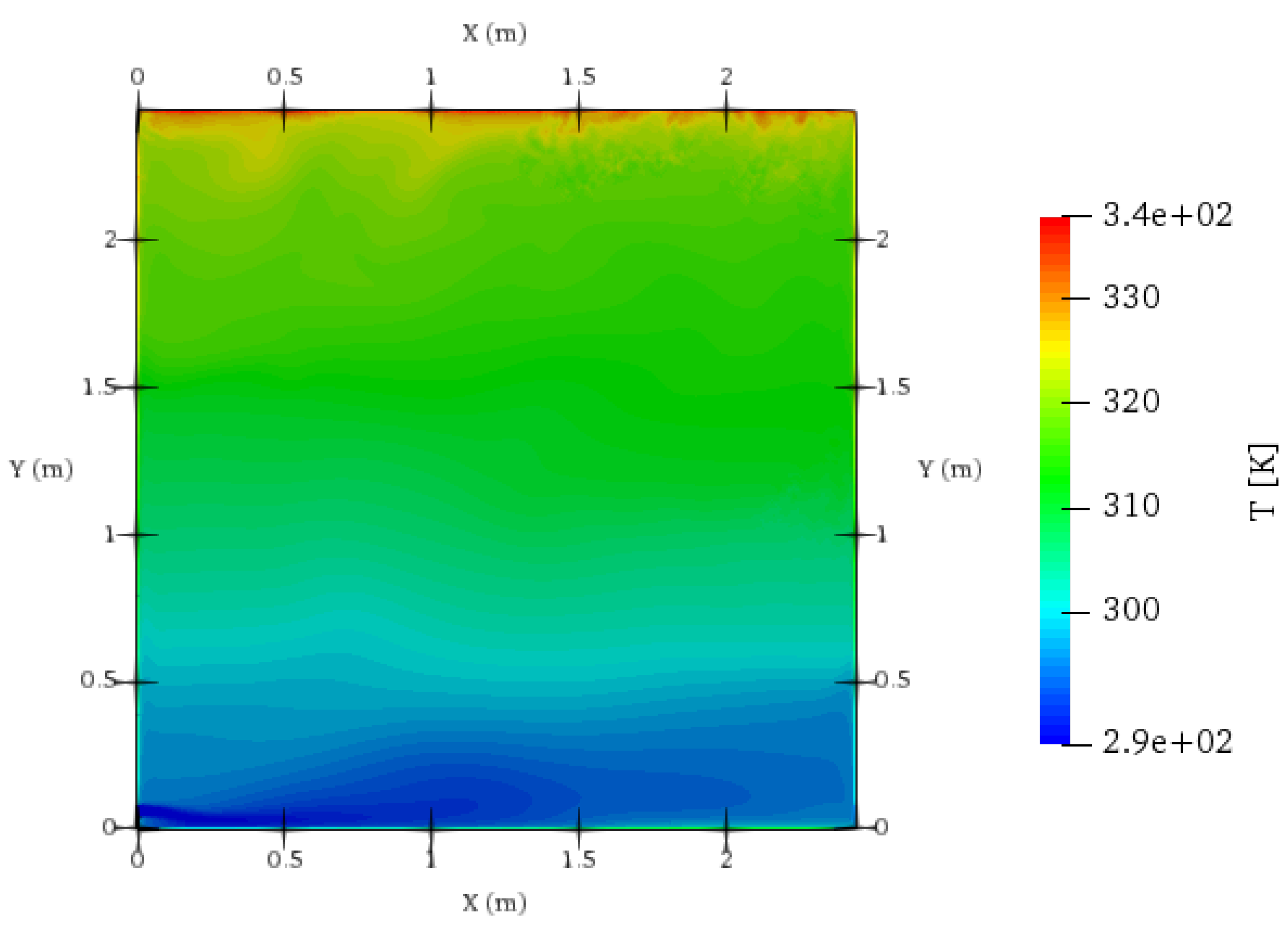

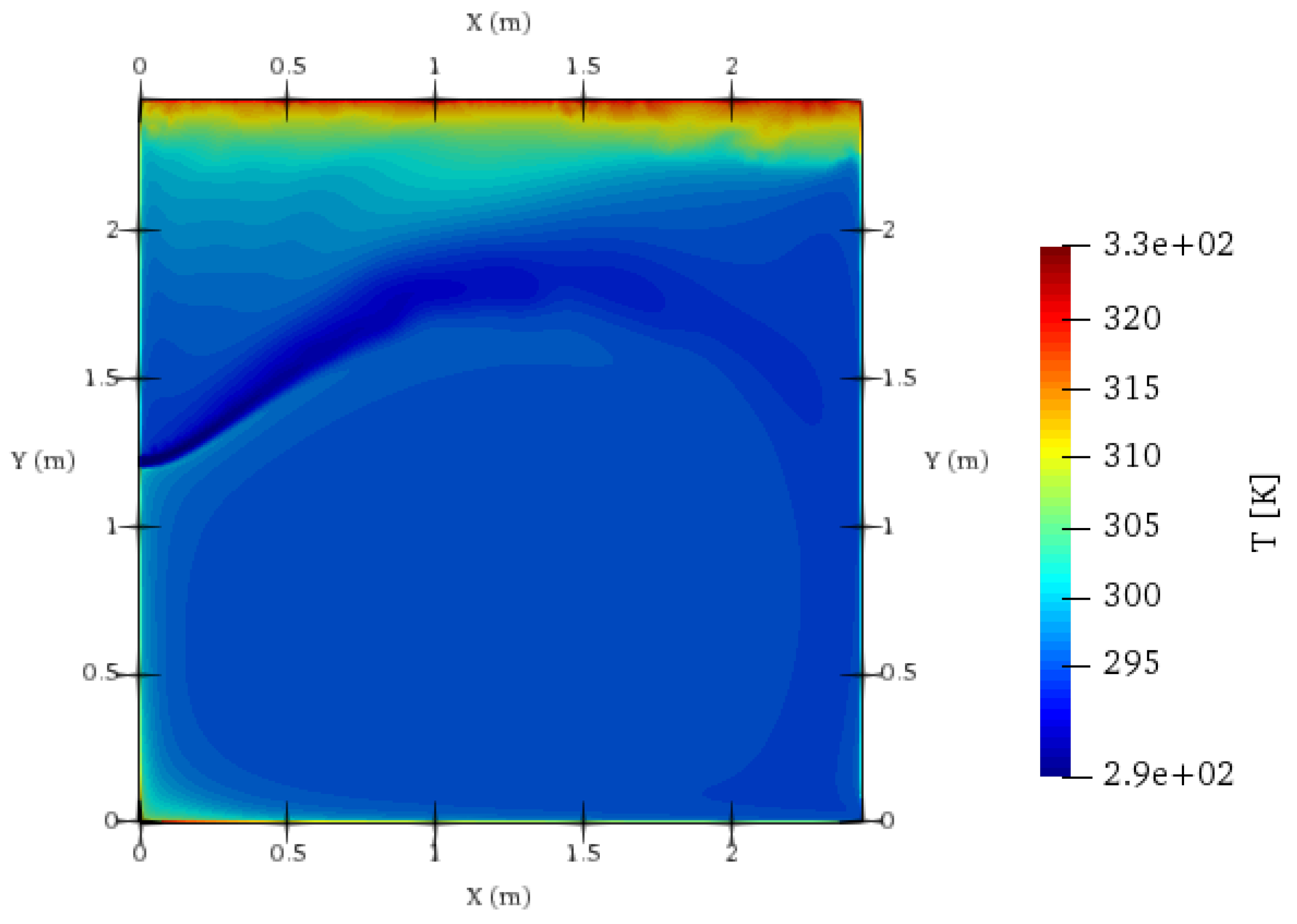

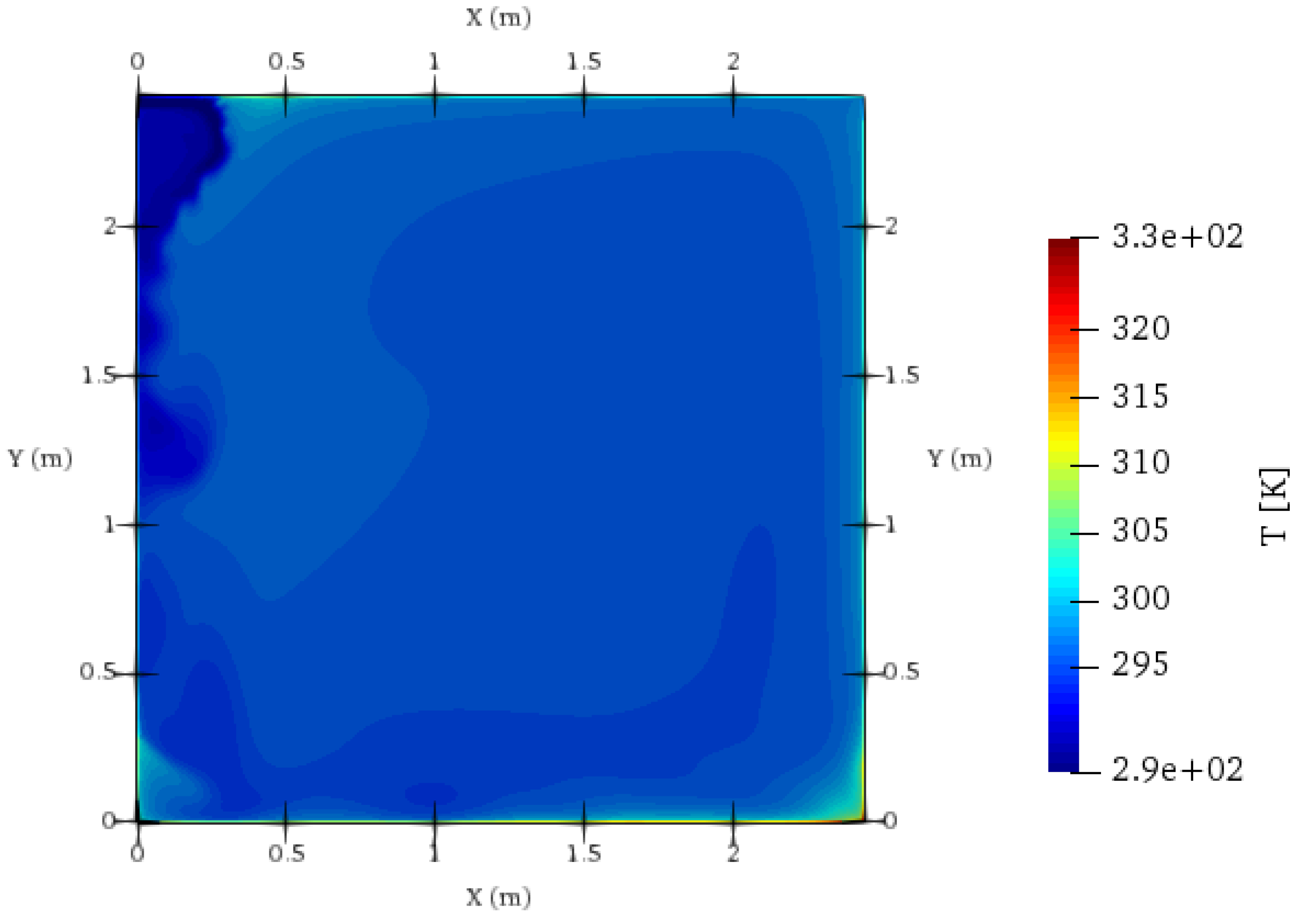

3. Results and Discussion

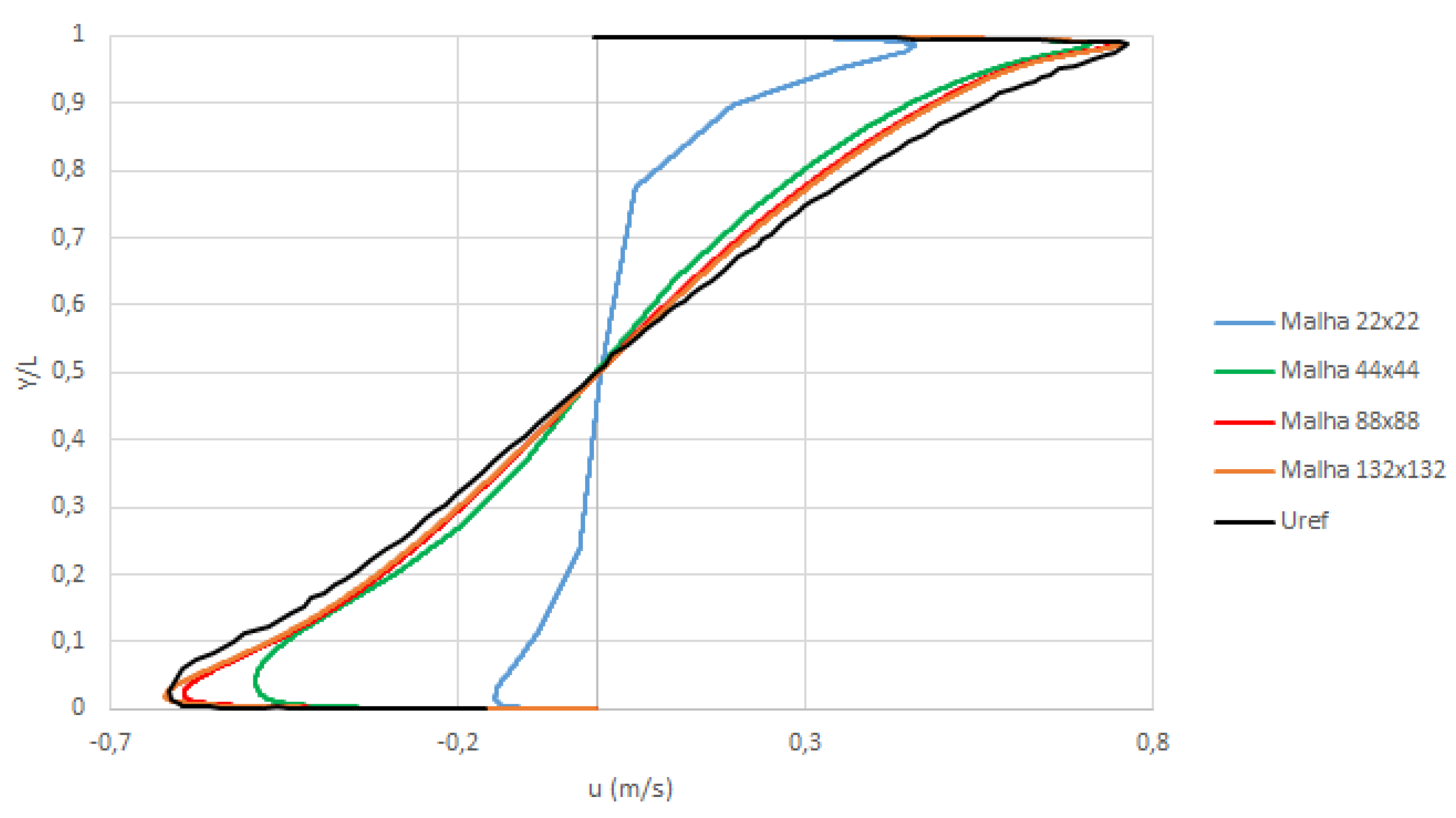

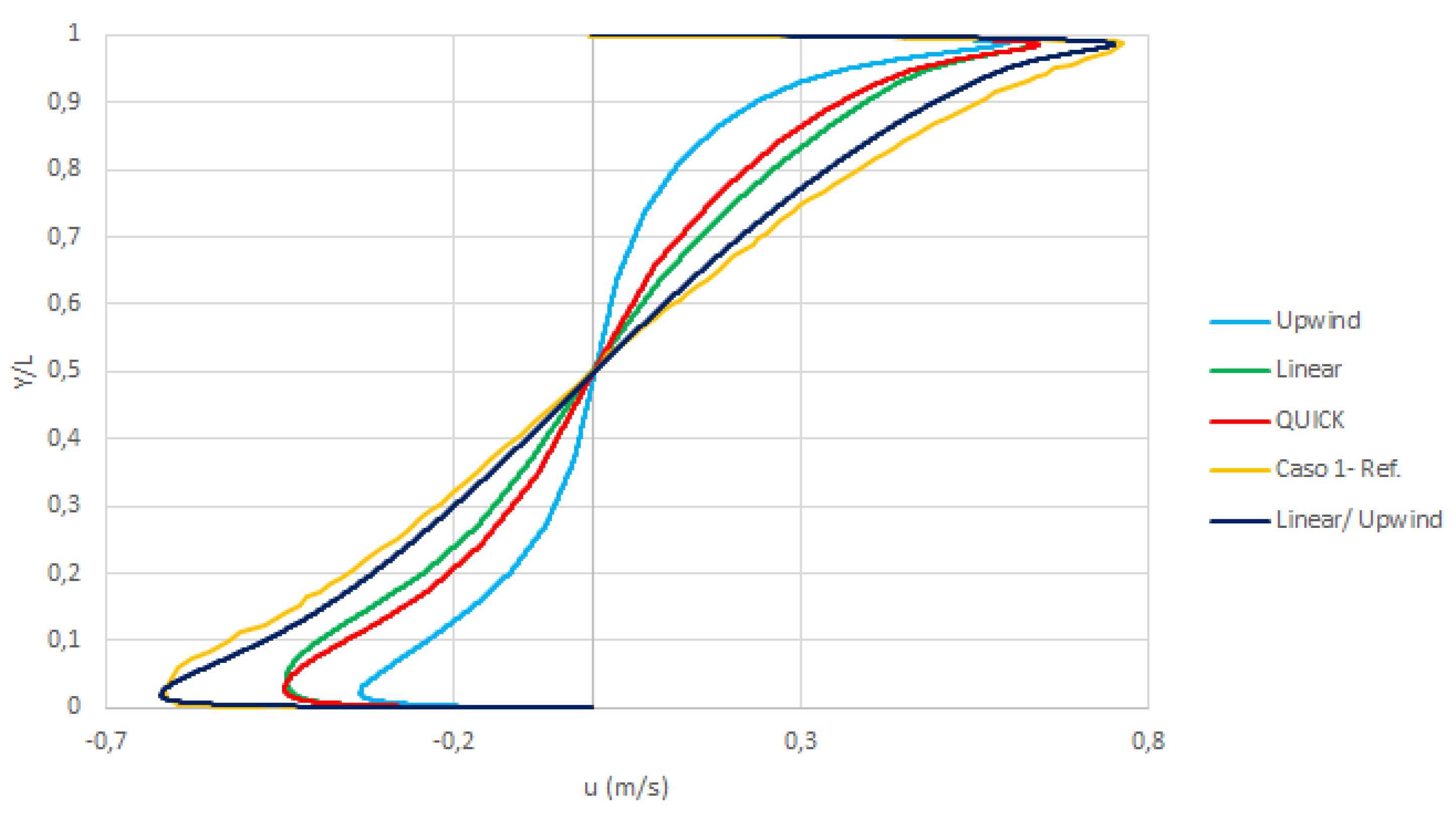

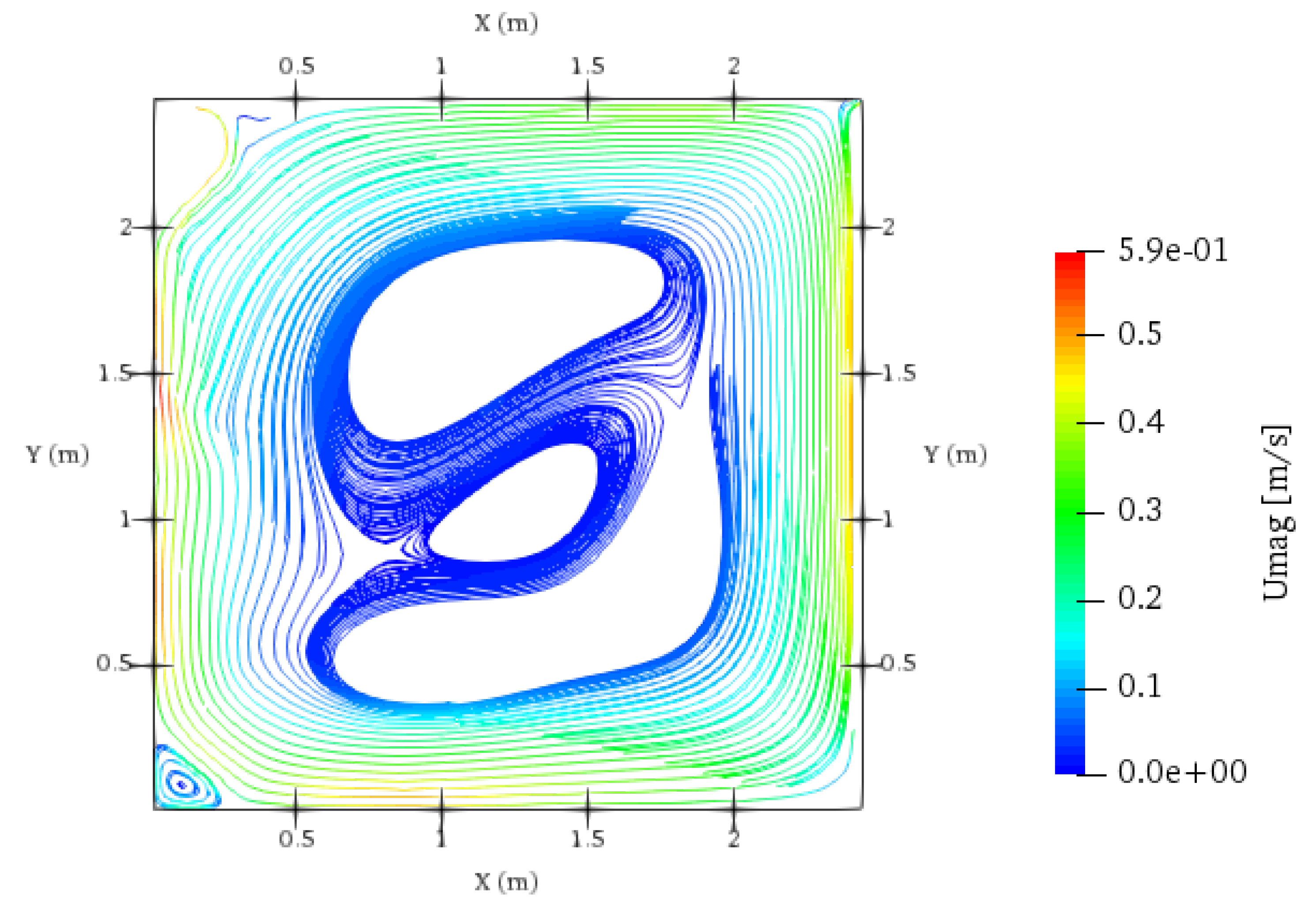

3.1. Validation of the Computational Parameters to Be Used in OpenFOAM.

3.2. Analysis of the Systems of Ventilation Using Factorial Design

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADPI | Air Diffusion Performance Index |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| DV | Displacement Ventilation |

| EDT | Effective Draft Temperature |

| HVAC | Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning |

| MV | Mixing Ventilation |

| OpenFOAM | Open Field Operation And Manipulation |

| RANS | Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes |

| RNG | Renormalization Group Theory |

| SIMPLE | Semi-Implicit Method for Pressure-Linked Equations |

| SV | Stratified Ventilation |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

References

- Mehrdad, R.; Habtamu Bayera, M.; Natasa, N. Building Retrofitting through Coupling of Building Energy Simulation-Optimization Tool with CFD and Daylight Programs. Energies 2021, 2180, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Matthew, B.; Daniel, M.; Simon Paul, B. Humidity Distribution in High-Occupancy Indoor Micro-Climates. Energies 2021, 681, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Stoecker, W.F.; Jones, J.W. Refrigeração e ar condicionado; McGraw-Hill do Brasil, 1985.

- Daehyun, K.; Hyunmuk, L.; Jongmin, M.; Jinsoo, P.; Gwanghoon, R. Heating Performances of a Large-Scale Factory Evaluated through Thermal Comfort and Building Energy Consumption. Energies 2021, 5617, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.; Lin, Z. Experimental study of airflow characteristics of stratum ventilation in a multi–occupant room with comparison to mixing ventilation and displacement ventilation. Indoor Air 2015, 25, 662–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Che, W.W.; Tso, C.Y.; Sun, L.; Ip, D.Y.; Lee, H.; Chao, C.Y.; Lau, A.K. Energy consumption, indoor thermal comfort and air quality in a commercial office with retrofitted heat, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) system. Energy and Buildings 2019, 201, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE. ASHRAE STANDARD 55. Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy, 2013.

- Limane, A.; Fellouah, H.; Galanis, N. Three-dimensional OpenFOAM simulation to evaluate the thermal comfort of occupants, indoor air quality and heat losses inside an indoor swimming pool. Energy and Buildings 2018, 167, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SIMSCALE. Tutorial: Thermal Comfort Parameters for HVAC Simulations, 2016.

- Liu, S.; Clark, J.; Novoselac, A. Air diffusion performance index (ADPI) of overhead-air-distribution at low cooling loads. Energy and Buildings 2017, 134, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samiuddin, S.; Budaiwi, I.M. Assessment of thermal comfort in high-occupancy spaces with relevance to air distribution schemes: A case study of mosques. Building Services Engineering Research and Technology 2018, 39, 572–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.; Kadirgama, K.; Ng, E. Response surface models for CFD predictions of air diffusion performance index in a displacement ventilated office. Energy and Buildings 2008, 40, 774–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, A.A.; Mina, E.M.; ElBaz, A.R.; AbdelMessih, R.N. Studying comfort in a room with cold air system using computational fluid dynamics. Ain Shams Engineering Journal 2018, 9, 1753–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdova-Suárez, M.; Tene-Salazar, O. .; Tigre-Ortega, F..; Carrillo-Ríos, S..; Córdova-Suárez, D..; TapiaVasco, L..; Quesada-Revelo, D. An OpenFOAM simulation of the natural ventilation system in a university chemical laboratory. E3S Web Conf. 2020, 167, 04003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE. ASHRAE STANDARD 55. Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy, 2013.

- Launder, B.; Spalding, D. The numerical computation of turbulent flows. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering 1974, 3, 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, H.; Piotr, C.; Zbigniew, P. Eddy–Viscosity Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes Modeling of Air Distribution in a Sidewall Jet Supplied into a Room. Energies 2024, 1261, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- da Silveira Neto, A. Escoamentos Turbulentos Análise Física e Modelagem Teórica; Composer Arte e Editora, 2020.

- OpenFOAM. About OpenFOAM, 2021.

- Versteeg, H.; Malalasekera, W. An Introduction to Computational Fluid Dynamics: The Finite Volume Method; Pearson Education, 2007.

- Patankar, S. Numerical Heat Transfer and Fluid Flow; CRC Press, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Maliska, C.R. Transferência de Calor e Mecânica dos Fluidos Computacional; LTC, 1995.

| Condition | U | T | |||||

| initial | (0.0,0.0,0.0) | 0.0 | 300 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| inlet | (0.8,0.0,0.0) | 287.15 | 0.0 | 4.0e-6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| outlet | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.0e-6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| left, right, top | (0.0,0.0,0.0) | 0.0 | 4.0e-6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| botton | (0.0,0.0,0.0) | 0.0 | 4.0e-6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| front, back | empty | empty | empty | empty | empty | empty | empty |

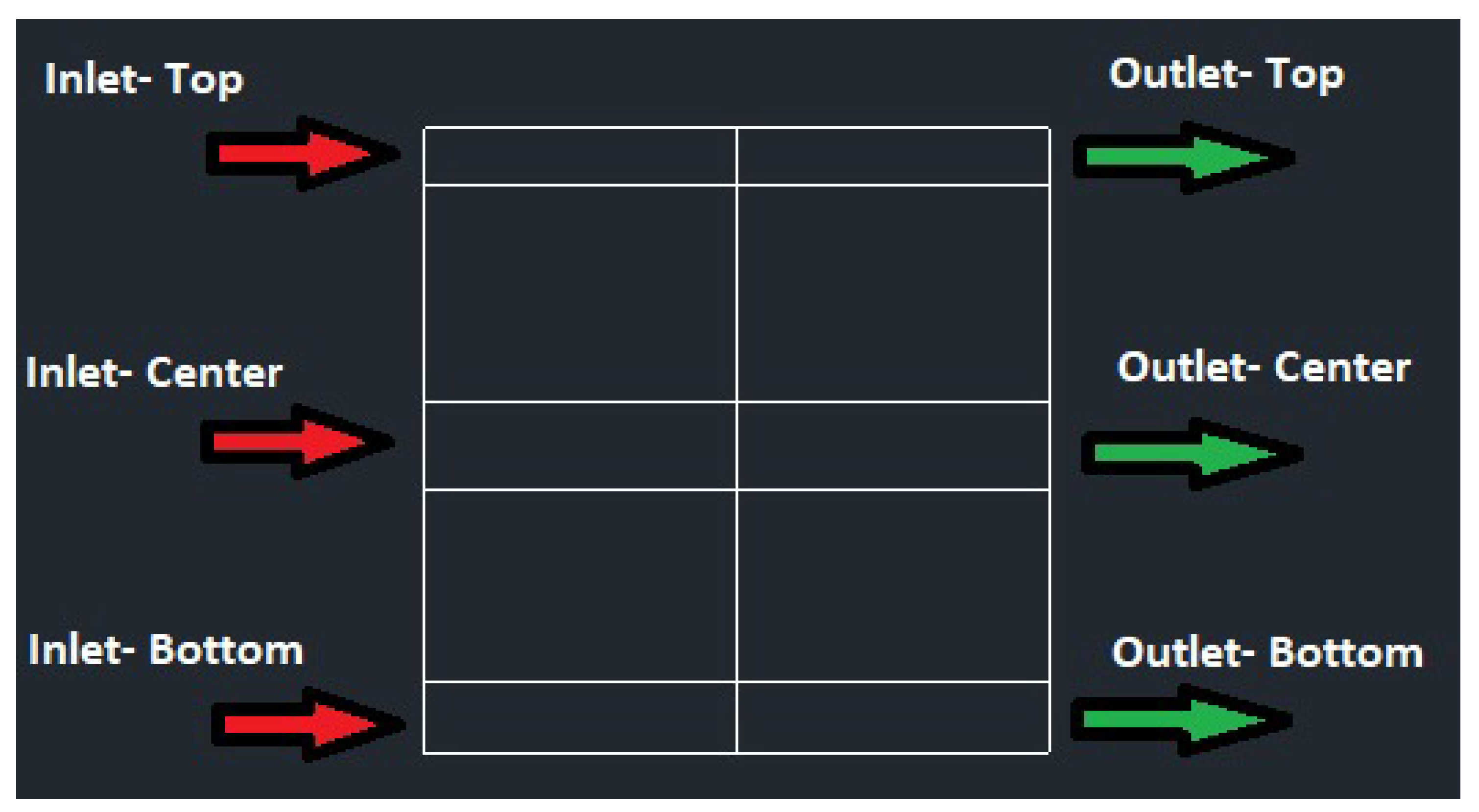

| Inlet position | Outlet position | Air supply velocity (m/s) |

|---|---|---|

| Bottom | Bottom | 0.5 |

| Center | Center | 0.8 |

| Top | Top | 1.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).