1. Introduction

Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile), a Gram-positive, anaerobic, spore-forming bacillus, is recognized as an opportunistic pathogen present in the intestinal tracts of both humans and animals, as well as in the environment [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Recent reports highlight its emergence as a predominant pathogen responsible for healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) [

1,

2,

3]. Moreover,

C. difficile has become the primary etiological agent of infective diarrhea in developed nations [

4,

6]. Notably, it stands as a major contributor to escalating healthcare costs, with an estimated excess of USD 11,285 per case reported in the United States alone [

7]. In the United Kingdom,

C. difficile infection

(CDI) stands as the predominant hospital-acquired infection, and it is still increasing. In 2004, about 44,107 instances of

C. difficile were documented among individuals 65 years of age or older, according to statistics supplied by the Department of Health for England and Wales. The following year saw an increase in cases to 51,690, highlighting the alarming rising trend in CDIs [

8].

Because drugs alter the composition of the gut microbiota and reduce colonization resistance, there is a strong correlation between antibiotic exposure and the frequency of CDI [

9,

10,

11]. By interfering with the synthesis of secondary bile acids, this mutation promotes the colonization of

C. difficile and contributes to the pathophysiology of active infection [

12]. In particular, the capacity of the host to convert primary bile acids into secondary bile acids is weakened by antibiotic use, leading to the germination of

C. difficile spores [

12]. These factors combine to promote the development of active infection in colonized individuals, and the primary bile acid taurocholate assists in this process [

12].

Antibiotic usage and the prevalence of CDI are substantially correlated, with penicillin, cephalosporins, clindamycin, and fluoroquinolones presenting the highest risks [

13,

14]. Elderly people, especially those over 65 years of age, are 10 times more vulnerable than younger patients [

15,

16]. Hospitalization, gastrointestinal surgery, immunosuppressive conditions, organ transplantation, chemotherapy, inflammatory bowel illness, chronic renal disease, exposure to environmental contaminants, contact with a known carrier of

C. difficile, and a history of CDI are additional risk factors for infection [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Although its potential to increase infection risk by changing the gut microbiota and making people more vulnerable to

C. difficile colonization and infection is being investigated, the function of stomach acid suppression in CDI remains debatable [

22].

In fact, several studies found that the patients’ rates of

C. difficile colonization increased from 2 to 20%, with longer hospital stays, longer antibiotic usage, close contact with sick or colonized people, and nursing home living being associated with increased risk [

23,

24,

25]. All previous reasons for

C. difficile colonization originated from the highly resistant spores of

C. difficile. Viable

C. difficile spores are commonly detected in healthcare environments and can be discovered on stethoscopes, bedside furniture, the hands of healthcare personnel, cellphones, and other medical equipment [

23,

26]. This highlights the importance of nurses and other healthcare workers following strict hand hygiene and infection prevention and control protocols [

23,

27,

28]. Using disposable gloves and gowns, hand washing with soap and water, solitary patient isolation, daily cleaning of high-touch surfaces, and comprehensive room decontamination upon patient discharge are effective ways of lowering the risk of CDI [

26,

29]. The adoption of these infection control measures, which greatly lower the prevalence of CDI in healthcare settings, is contingent upon the involvement of nurses and other healthcare workers. As active members of antimicrobial stewardship teams, nurses collaborate with other healthcare professionals to monitor patients with CDI and teach them and their families about the use of antibiotics [

26,

29]. This study investigated the awareness and understanding of CDI among nurses in Saudi Arabia, as there has been no prior research on this topic. The objective was to identify knowledge gaps to enhance future training programs for nurses and healthcare professionals on infection control procedures.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This was an observational, cross-sectional study was conducted involving nursing staff from three tertiary public hospitals in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, between July and December 2023.

2.2. Structure of Questionnaire

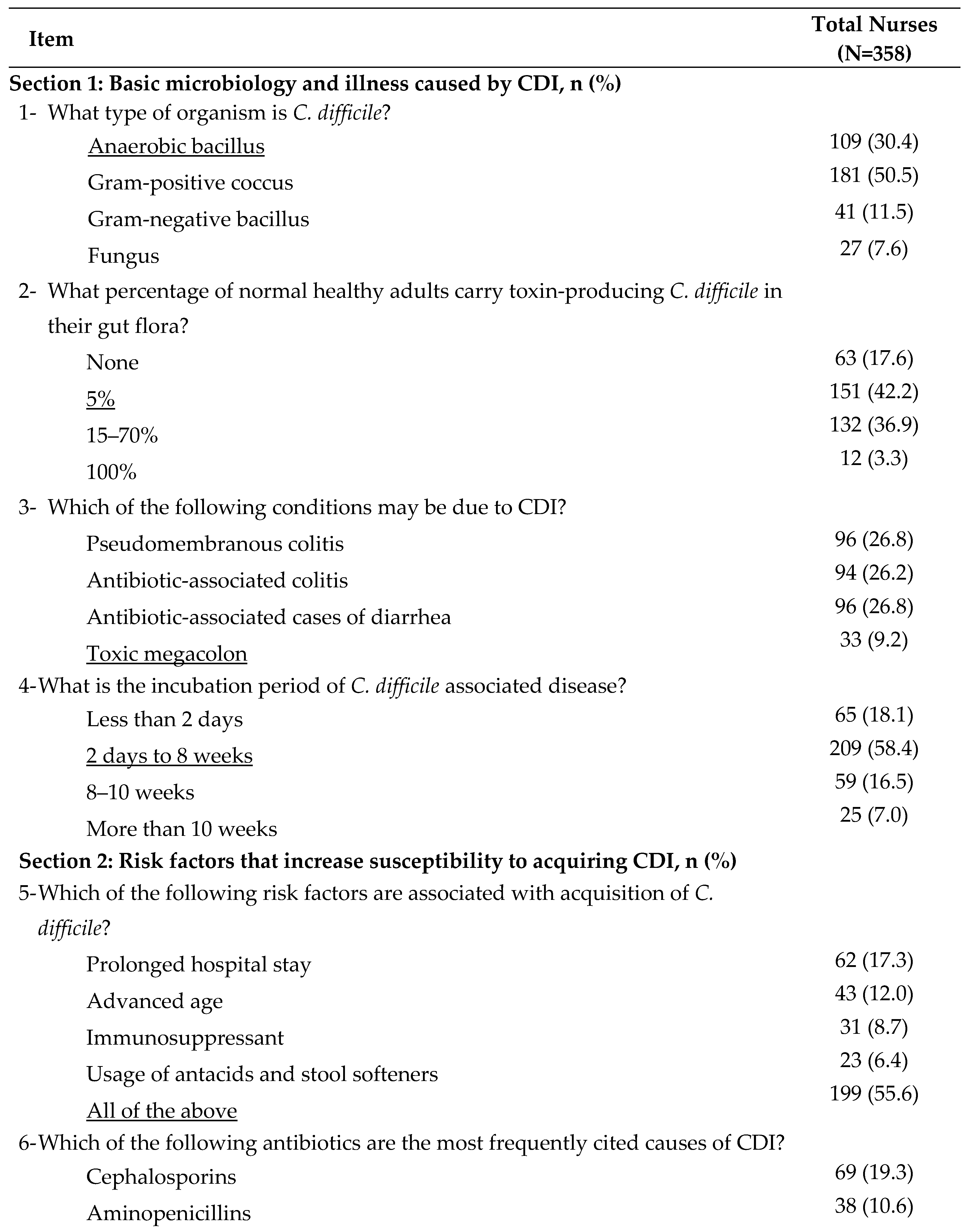

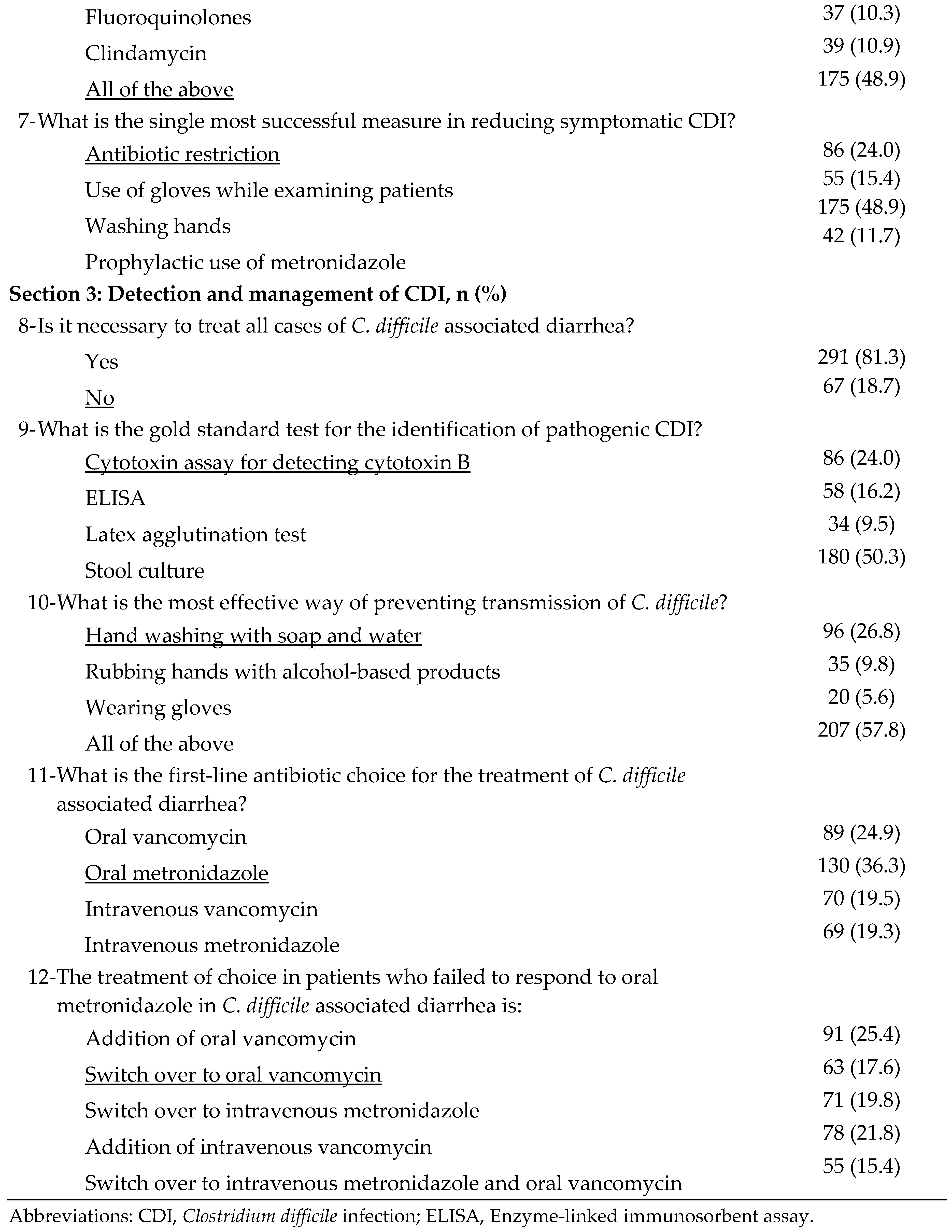

Data regarding demographic characteristics and knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding CDI were obtained using a pre-tested, semi-structured, and close-ended questionnaire. The questionnaire was structured and modified with 17 core questions, three on demographics, and two on CDI information received by nurses. Other questions focused on basic microbiology and illness caused by CDI (items 1-4), risk factors for increased susceptibility to CDI (items 5-7), and CDI detection and management (items 8-12) [

30]. All 17 core questions on knowledge, attitudes, and practices were scored on a three-point scale. The questionnaire clearly stated that the information would be used only for scientific purposes, and the participants signed a consent form. The questionnaire was in English. Instructions were included to simplify the questionnaire. Participants were also encouraged to ask any questions regarding the content of the questionnaire.

2.3. Ethical Consideration

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Majmaah University (Approval No. MUREC- Jan.l7 /COM-2023/3-4). Prior to the participants completing the online questionnaire, informed consent was obtained, and the participants were informed of the goals and advantages of the study. All information was kept private and used solely for statistical analysis.

2.4. Data Collection

The questionnaire was developed using Google Forms and mailed to all nurses. A total of 358 nurses (male and female) were included in the stratified random sampling based on their educational level (

Table 1).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data were coded and analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) program. The responses were analyzed descriptively to define the distribution of the demographic and other characteristics. Categorical variable scores were analyzed as numerical variables and expressed as numbers and percentages.

3. Results

A total of 358 nurses working at three different hospitals in Saudi Arabia responded to the questionnaire. Overall, 67% (n=240) of the respondents were female and 33% (n=118) male (

Table 1). Regarding whether they had received information about hospital protocols and policies concerning CDI, 66% (n= 236) of respondents indicated that they had received such information, whereas 34% (n=122) indicated that they had not (data not shown). Regarding knowledge of the basic microbiology and illness caused by CDI (questions 1-4;

Table 2), 30.5% (n=109) of respondents correctly identified

C. difficile as an anaerobic bacillus, and 42% (n=151) correctly determined the percentage of normal healthy adults carrying toxin-producing

C. difficile in their gut flora. However, only a small number of respondents (n= 33; 9%) knew that toxic megacolon is a condition caused by CDI. Additionally, most of the respondents (58%; n=209) were aware that the incubation for CDI ranges from 2 days to 8 weeks. Regarding risk factors for increased susceptibility to CDI (questions 5-8;

Table 2), approximately 56% of respondents (n=199) demonstrated awareness of the various predisposing factors for acquiring

CDI. Only about 49% (n=175) of respondents could correctly identify the drugs cephalosporins, aminopenicillins, fluoroquinolones, and clindamycin as the most frequently cited causes of CDI. However, 86 (24%) respondents indicated that restricting the use of antibiotics was the most effective strategy for reducing symptomatic

CDIs.

Concerning the detection and management of CDI (items 8-12;

Table 2), approximately 19% (n=67) of respondents believed that it was not necessary to treat all cases of

C. difficile associated diarrhea, whereas 81% (n=291) answered that it was necessary to treat all cases of

C. difficile associated diarrhea. When asked about the gold standard test for identifying CDI, only 24% (n=86) of respondents were able to identify cytotoxin assay for detecting cytotoxin B as the gold standard test for the identification of pathogenic CDI. Interestingly, approximately 50% (n=180) of respondents answered that the stool culture was the gold standard. Moreover, 27% (n=96) of respondents identified hand washing with soap and water as the most effective way to prevent the transmission of

C. difficile. When asked about the first-choice antibiotic for the treatment of

C. difficile associated diarrhea, 36% (n=130) of respondents were able to choose the right answer, which is oral metronidazole. However, approximately 18% (n=63) correctly identified oral vancomycin as the second option for patients who fail to respond to oral metronidazole in cases of

C. difficile-associated diarrhea.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the knowledge and practices related to CDI diagnosis and management among nurses in Saudi Arabia. Our survey of 358 nurses in Saudi Arabia revealed that 67% were female, and 66% had received information on C. difficile protocols. Only 30.5% correctly identified C. difficile as an anaerobic bacillus, whereas 42% knew its prevalence in healthy adults. Approximately 56% were aware of risk factors, and 49% identified common antibiotics that cause infection. For detection, 24% recognized the cytotoxin assay as the gold standard test. Regarding prevention, 27% endorsed hand washing, and 36% correctly chose oral metronidazole as the first-line treatment. C. difficile is a Gram-positive, anaerobic, spore-forming bacillus found in human and animal intestines and in the environment. It has emerged as a leading cause of HAIs and infectious diarrhea in developed countries, significantly increasing healthcare costs, with an estimated USD 11,285 per case in the US. In the UK, C. difficile is the most common HAI, with cases increasing from 44,107 in 2004 to 51,690 in 2005 among individuals aged 65 and older.

Similar to our research on Saudi Arabian nurses, several studies have examined nurses’ awareness and understanding of CDI. With regard to the introduction of a

C. difficile prevention bundle, Musuuza et al.

[31] examined the implementation of

C. difficile preventive measures, along with relevant facilitators and obstacles. Similar to this study, they focused on how crucial it is for nursing personnel to obtain appropriate training and knowledge. According to the findings, higher nurse staffing levels and a positive work atmosphere lower infection rate [

31], which is consistent with the present study’s focus on knowledge and procedure adherence. In an Australian study on nurses’ awareness of

C. difficile, Kelly et al.

[32] revealed that just 25% of nurses accurately recognized issues connected to

C. difficile, which is comparable to the poor awareness levels (9%) discovered in our research concerning toxic megacolon. Studies conducted in Australia and the UK have reported similar findings: only 53% and 70% of Australian and UK nurses, respectively, correctly identified the incubation period for

C. difficile, indicating widespread knowledge gaps [

30,

33]. A cross-sectional study conducted among Italian nurses highlighted similar gaps in CDI knowledge and protocol adherence. Approximately 74% of nurses used procedures and guidelines concerning CDI, but only 46.5% implemented specific CDI bundles in daily practice. Moreover, the study found a significant lack of postgraduate training on CDI among nurses [

34]

Research from the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing has emphasized the critical role of nurses in CDI management and prevention. The study outlined the importance of comprehensive education for nurses on CDI treatment protocols, emphasizing that only a subset of nurses is well-versed in these guidelines. The study also detailed the standard treatments, such as the use of oral metronidazole and vancomycin based on infection severity [

35], which is similar to what was observed in our study regarding knowledge of first-line treatment. A study examining knowledge and practices of CDI control in Canada found that 70% of nurses were aware of infection control measures, slightly higher than the 66% in our study, but still indicated significant gaps in comprehensive knowledge and practices [

31]. Another study examining Brazilian nurses’ knowledge of infection control reported that 60% of nurses had formal training in

C. difficile, which is similar to the 66% in our study. Both findings emphasize the need for continuing education and training [

32]. Our study found that 56% of nurses were aware of the proper incubation time for

C. difficile, which is significantly higher than the 35% reported in a UK-based study [

31]. Nurses have shown a greater general level of CDI management expertise in several US settings. According to previous studies, most nurses are aware of the clinical recommendations for CDI. A sizable percentage of them—more than 90%—knew the significance of particular infection control procedures and the role hand hygiene plays in preventing CDI transmission [

30,

34,36,37].

Regarding the effect of training programs, according to research in the United States, in-depth training programs dramatically increase nurses’ understanding of CDI [

31]. This corroborates our finding that 66% of nurses who received information knew more about hospital protocol. Another study noted significant variability in CDI knowledge among nurses depending on their education level and specific training received. For instance, nurses with advanced education or specific CDI training exhibited much higher awareness of and adherence to CDI management protocols than those without such training [

34]. A study examining nurses’ awareness of antibiotic stewardship in Germany found that only 30% of nurses were aware of the role of antibiotics in CDIs [

32], which is significantly lower than the 49% in the present study, suggesting a higher level of knowledge among Saudi nurses. In terms of infection control methods, a Japanese study revealed that 50% of nurses could name the appropriate CDI control strategies [

31], which is comparable to the present study’s finding—27% of respondents indicated that hand washing with soap and water was the best way to avoid infections. Furthermore, our study found that 36% of nurses recognized oral metronidazole as the first-line treatment for C. difficile, which is consistent to an Indian study where 40% of nurses were aware of the correct treatment methods. This highlights a significant level of awareness among nursing professionals regarding appropriate treatment options for this infection [

31].

The following are the study’s limitations. First, the sample size may not fully represent the national nursing population, but still provides valuable insights. Furthermore, the results may not be generalizable to all nurses due to the demographic distribution, with 67% being female participants. Second, this study relied on self-reported data from nurses, which may introduce bias. It is possible that participants might have inaccurately assessed their knowledge and behavior regarding CDI, potentially affecting the accuracy of the results. This study provides valuable insights into the skills and procedures of Saudi Arabian nurses but lacks a direct comparison with nurses from other countries. Such a comparison could enhance understanding of how Saudi nurses' behavior and knowledge align with or differ from international standards.

5. Conclusions

In summary, this study highlights the global challenge of ensuring that nursing staff members are adequately knowledgeable about C. difficile. The need for ongoing education and training to enhance the comprehension and management of CDI is a concept that unites all areas. The diverse levels of knowledge suggest that the efficacy of existing educational initiatives varies by location, even as common findings underscore this pervasive problem.

Studies have highlighted the vital significance of focused educational initiatives and continual training to improve nursing staff’s understanding and implementation of CDI management procedures. Offering clear and accessible guidelines, along with improving training programs, can help reduce the occurrence of CDI in healthcare settings and improve patient outcomes. CDI management faces global information gaps that persist across different regions, as evidenced by findings from a study in Saudi Arabia and other locations. Improving education and training programs are key to address the gaps, standardize CDI standards and enhance global management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A. and S.B.; methodology, A.A.; software, S.B..; validation, A.A. and S.B.; formal analysis, A.A..; investigation, A.A.; resources, S.B.; data curation, S.B.; writing—original draft preparation, S.B.; writing—review and editing, A.A.; visualization, S.B.; supervision, A.A. and S.B.

Funding

This research was supported by grant from the Deanship of Postgraduate Studies and Scientific Research at Majmaah University grant number.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Majmaah University under ethical approval No. MUREC- Jan.l7 /COM-2023/3-4) on 17-01-2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant from the Deanship of Postgraduate Studies and Scientific Research at Majmaah University grant number

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Barbut, F.; Petit, J.C. Epidemiology of Clostridium difficile-associated infections. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2001, 7, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, C.P.; LaMont, J.T. More difficult than ever. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 1932–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lessa, F.C.; Mu, Y.; Bamberg, W.M.; Beldavs, Z.G.; Dumyati, G.K.; Dunn, J.R.; Farley, M.M.; Holzbauer, S.M.; Meek, J.I.; Phipps, E.C.; et al. Burden of Clostridium difficile infection in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 825–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupnik, M.; Wilcox, M.H.; Gerding, D.N. Clostridium difficile infection: new developments in epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 7, 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zahrani, I.A. Clostridioides (Clostridium) difficile: A silent nosocomial pathogen. Saudi Med. J. 2023, 44, 825–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leffler, D.A.; Lamont, J.T. Clostridium difficile infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 1539–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubberke, E.R.; Olsen, M.A. Burden of Clostridium difficile on the healthcare system. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 55, S88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health. , D.O. Clostridium difficile infections: how many cases are reported and how many are estimated to be true cases?. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, R.; Donskey, C.J.; Munoz-Price, L.S. The intersection between colonization resistance, antimicrobial stewardship, and Clostridium difficile. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2018, 20, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, B.; Stricklin, M.; Wang, S. Gut microbiota-gut metabolites and Clostridioides difficile infection: Approaching sustainable solutions for therapy. Metabolites 2024, 14, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, C.; Taminiau, B.; Van Broeck, J.; Delmee, M.; Daube, G. Clostridium difficile infection and intestinal microbiota interactions. Microb. Pathog. 2015, 89, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorg, J.A.; Sonenshein, A.L. Bile salts and glycine as cogerminants for Clostridium difficile spores. J Bacteriol. 2008, 190, 2505–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, L.M.; Allegretti, J.R. The epidemiology and management of Clostridioides difficile infection-A clinical update. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 59, 1335–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullish, B.H.; Williams, H.R. Clostridium difficile infection and antibiotic-associated diarrhoea. Clin. Med. (Lond). 2018, 18, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessa, F.C.; Gould, C.V.; McDonald, L.C. Current status of Clostridium difficile infection epidemiology. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 55, S65–S70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, F.; Forrester, M.; Advinha, A.M.; Coutinho, A.; Landeira, N.; Pereira, M. Clostridioides difficile infection in hospitalized patients—a retrospective epidemiological study. In Proceedings of the Healthcare; 2023; p. 76. [Google Scholar]

- Nitzan, O.; Elias, M.; Chazan, B.; Raz, R.; Saliba, W. Clostridium difficile and inflammatory bowel disease: Role in pathogenesis and implications in treatment. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 7577–7585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, M.; Wang, C.; Xia, Y.; Tang, J.; Wang, J.; Shen, L. Clostridioides difficile infection in inflammatory bowel disease: A clinical review. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2024, 22, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, M.; Guo, H.; Zheng, X.Y. Inflammatory bowel disease and Clostridium difficile infection: Clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management. Therap. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2023, 16, 17562848231207280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.C.; Seo, M.Y.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, K.T.; Cho, E.; Kim, M.G.; Jo, S.K.; Cho, W.Y.; Kim, H.K. Advanced chronic kidney disease: A strong risk factor for Clostridium difficile infection. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2016, 31, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubberke, E.R.; Reske, K.A.; Noble-Wang, J.; Thompson, A.; Killgore, G.; Mayfield, J.; Camins, B.; Woeltje, K.; McDonald, J.R.; McDonald, L.C.; et al. Prevalence of Clostridium difficile environmental contamination and strain variability in multiple health care facilities. Am. J. Infect. Control 2007, 35, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leffler, D.A.; Lamont, J.T. Clostridium difficile infection. N. Engl. J Med. 2015, 372, 1539–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roghmann, M.C.; Andronescu, L.R.; Stucke, E.M.; Johnson, J.K. Clostridium difficile colonization of nursing home residents. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2017, 38, 1267–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furuya-Kanamori, L.; Marquess, J.; Yakob, L.; Riley, T.V.; Paterson, D.L.; Foster, N.F.; Huber, C.A.; Clements, A.C. Asymptomatic Clostridium difficile colonization: Epidemiology and clinical implications. BMC Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jump, R.L.; Donskey, C.J. Clostridium difficile in the long-term care facility: prevention and management. Curr. Geriatr. Rep. 2015, 4, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kociolek, L.K.; Gerding, D.N.; Carrico, R.; Carling, P.; Donskey, C.J.; Dumyati, G.; Kuhar, D.T.; Loo, V.G.; Maragakis, L.L.; Pogorzelska-Maziarz, M.; et al. Strategies to prevent Clostridioides difficile infections in acute-care hospitals: 2022 Update. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2023, 44, 527–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.; Gerding, D.N.; Olson, M.M.; Weiler, M.D.; Hughes, R.A.; Clabots, C.R.; Peterson, L.R. Prospective, controlled study of vinyl glove use to interrupt Clostridium difficile nosocomial transmission. Am. J. Med. 1990, 88, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.C.; Knight, D.R.; Riley, T.V. Clostridium difficile and One Health. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 857–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, E.J.; Greendyke, W.G.; Furuya, E.Y.; Srinivasan, A.; Shelley, A.N.; Bothra, A.; Saiman, L.; Larson, E.L. Exploring the nurses' role in antibiotic stewardship: A multisite qualitative study of nurses and infection preventionists. Am. J. Infect. Control 2018, 46, 492–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aroori, S.; Blencowe, N.; Pye, G.; West, R. Clostridium difficile: How much do hospital staff know about it? Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2009, 91, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musuuza, J.S.; Hundt, A.S.; Carayon, P.; Christensen, K.; Ngam, C.; Haun, N.; Safdar, N. Implementation of a Clostridioides difficile prevention bundle: Understanding common, unique, and conflicting work system barriers and facilitators for subprocess design. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2019, 40, 880–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.R.; Fischer, M.; Allegretti, J.R.; LaPlante, K.; Stewart, D.B.; Limketkai, B.N.; Stollman, N.H. ACG Clinical guidelines: Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of Clostridioides difficile infections. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 116, 1124–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finnimore, K.; Smyth, W.; Carrucan, J.; Nagle, C. Nurses' knowledge, practices and perceptions regarding Clostridioides difficile: Survey results. Infect. Dis. Health 2023, 28, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comparcini, D.; Simonetti, V.; Segala, F.V.; Di Gennaro, F.; Bavaro, D.F.; Pompeo, M.A.; Saracino, A.; Cicolini, G. Nurses' Knowledge, attitudes and practices on the management of Clostridioides difficile infection: A cross-sectional study. Antibiotics (Basel) 2023, 12, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph Brodine, A.K. Clostridium difficile infection: What nurses need to know. Available online: https://nursing.jhu.edu/magazine/articles/2011/12/clostridium-difficile-infection-what-nurses-need-to-know/ (accessed on.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the samples (N=358).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the samples (N=358).

| Characteristics |

Total Nurses (N=358) |

| Sex at birth, n (%) |

|

| Male |

118 (33.0) |

| Female |

240 (67.0) |

| Educational level, n (%) |

|

| Diploma in nursing |

42 (11.7) |

| Bachelor`s Degree |

236 (65.9) |

| Master`s Degree |

74 (20.7) |

| Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) |

6 (1.7) |

Table 2.

Answer distribution to questions on various aspects of CDI (N=358). Correct answers are underlined.

Table 2.

Answer distribution to questions on various aspects of CDI (N=358). Correct answers are underlined.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).