1. Introduction

In team sports, the training process can be defined as the systematic and periodized prescription of stress or fatigue and rest, with the purpose of inducing positive changes in technical and tactical skills, physical capacities (e.g., strength or endurance), and health (i.e., free-injury) of the players [

1,

2,

3]. Indeed, some researchers suggest that we should consider the training process as a dose-response binomial that produces adaptations in the player, like in other biomedical sciences such as medicine or pharmacology [

4,

5]. Therefore, an in-depth knowledge of training load, match load and post-match recovery status brings numerous benefits to players and coaches: (1) enhance comprehension of fatigue and recovery process [

2], (2) optimize the planning process to maximize performance, reduce injury risk and, consequently, increase player availability [

1], (3) prevent a permanent state of chronic fatigue, overreaching and overtraining [

6]. In addition, in handball and many other team sports, in-season load monitoring allows coaches and practitioners to better adapt and periodize weekly training loads. This approach helps to manage stress and recovery and enables the design of physical training interventions within the microcycle considering the player role in the match (starter vs. non-starter) [

7,

8].

Currently, there is a strong consensus in the scientific literature that load is composed of two elements: the external load and the internal load [

3,

9]. External load can be defined as the physical activities performed by players (i.e., the stimulus imposed), which can be measured with standard units, such as kilograms, meters, seconds, velocity/speed, and power [

2,

10,

11], whereas internal load represents the individual psycho-physiological responses to the external load, which can be measured with objective (e.g., heart rate or blood lactate) and subjective indicators (e.g., rate of perceived exertion or well-being responses) [

2,

10,

11]. However, as many researchers indicate, an identical external load could result in considerably different internal load in each player due to the combination of various intrinsic (e.g., chronological age or genetics) and extrinsic factors (e.g., previous training level) [

9,

12]. Consequently, the same training stimulus (i.e., external load) may be appropriate for one player, but inappropriate (either significantly higher or lower) for another [

11,

12]. Therefore, it is essential to combine internal load indicators, both objective and subjective, with perceived well-being to determine if the player tolerates and recovers from the external load experienced during training or competition [

9,

12].

In relation to the above mentioned, the rate of perceived exertion (RPE) has proved to be a valid and sensitive internal load monitoring tool in handball players due to its high correlation with other objective internal parameters (e.g., heart rate) and external load metrics (e.g., PlayerLoad) [

13]. Also, the RPE presents some advantages compared to other objective markers: (1) easy-to-collect; (2) less time-consuming; (3) low-cost; and (4) non-invasive [

7,

13]. Additionally, in recent years the use of different objective and subjective tools for monitoring players’ fatigue and well-being has become popular among the scientific community and sports practitioners [

14]. The most widely used tool is the Hooper Index, which includes self-analysis questionnaires about fatigue, stress, muscle soreness and sleep quality, has been used in several investigations to analyze the match-induced fatigue, the perceived well-being and the recovery time-course of players in the days following the match [

10,

15,

16]. Nevertheless, in handball the assessment of the match load during official competitions has been done mainly through the external load assessment [

17]. This is reflected in the few numbers of studies analyzing the internal load and the post-match recovery perceptions throughout the microcycle, especially in female handball. More specifically, only two studies conducted with elite male handball players reveal that RPE and well-being status fluctuate throughout the different days of the microcycle [

8,

18]. Specifically, Font et al. (2023) found that the lowest values of RPE were reported in MD-1. Likewise, Clemente et al. (2019) concluded that, in both normal and congested weeks, the highest loads occurred on MD-3 and MD-2.

Regarding player role, recent evidence from different team sports (e.g., basketball or soccer) shows that players with greater playing time experienced greater internal [

7,

19] and external load [

20,

21] during matches. Particularly in handball, starter players with more playing time exhibited higher absolute values of external load metrics (e.g., high-speed running, accelerations, decelerations and PlayerLoad) compared to non-starters [

22]. Consequently, it could be thought that handball players who accumulate more external load (i.e., starters) reported higher values of RPE, fatigue and muscle soreness, as suggested by previous studies in other team sports [

7,

18,

23]. In relation to playing positions, a new study conducted with elite male players showed that playing positions influenced the internal match-load experienced by the players [

8]. Specifically, these researchers found that pivots and right backs reported the lowest internal load compared to other positions [

8].

Nevertheless, to the authors’ knowledge, there is still limited information about how playing positions and player role impact on internal match-load and well-being status in female handball players. Therefore, the aim of this study was to analyze the effects of the playing position and player role on internal match-load and well-being status of female handball players after official matches.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Design

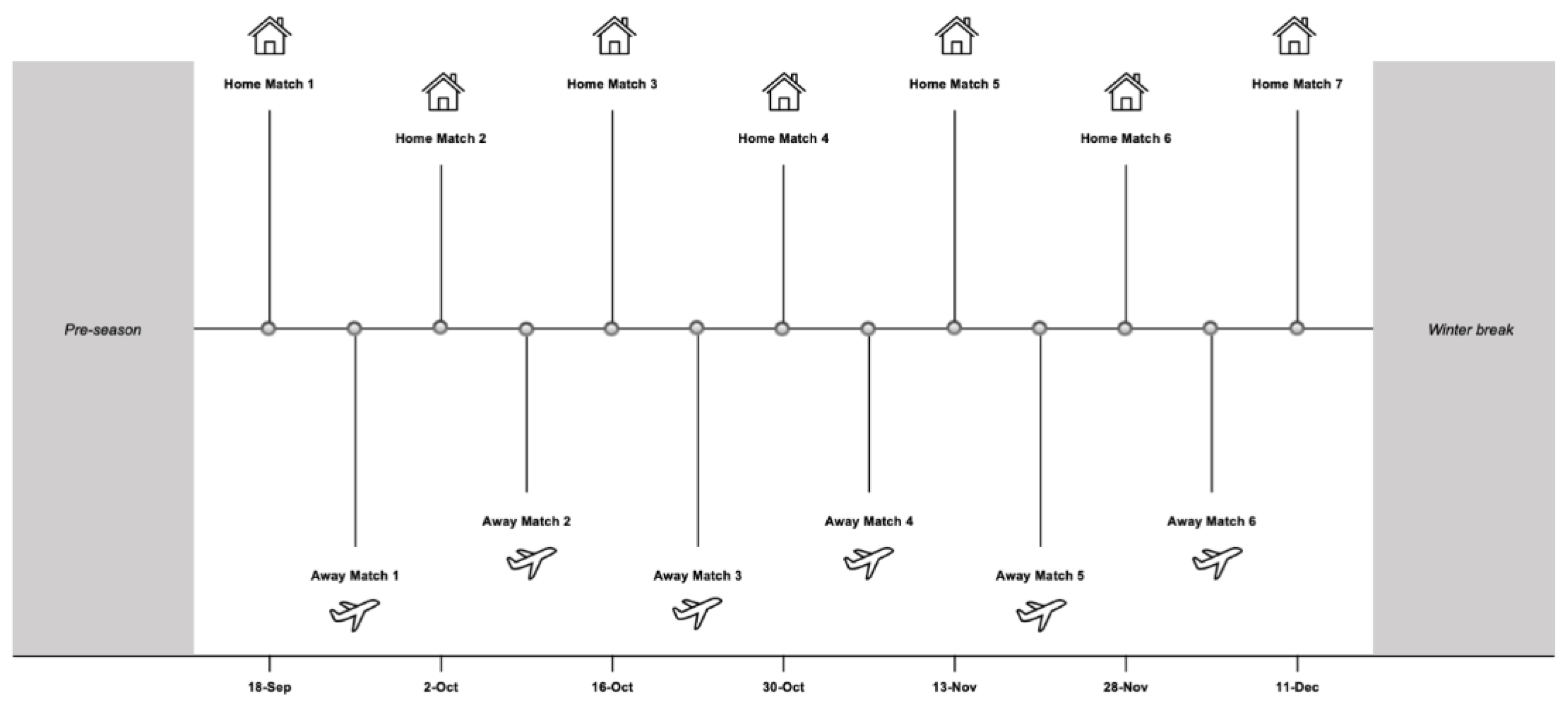

We conducted a retrospective-longitudinal design to monitor a female handball team during a half-season (

Figure 1). Internal match-load was obtained using rate of perceived exertion (match-RPE) during 13 official matches (home,

n = 7; away,

n = 6) from the Spanish 2

nd Division in the 2021–2022 season. Well-being status was collected through a modified version of the Hooper questionnaire in MD+1 (match day +1; one day after a match) and MD+2 (match day +2; two days after a match).

To analyze the effects of the playing position and player role on internal match-load and well-being status we categorized the players as follow: (1) playing positions (backs, n = 59 individual observations; pivots, n = 17 individual observations; wings, n = 26 individual observations), considering exclusively her position in offensive phase; and (2) player role (starters, n = 63 individual observations; non-starters, n = 39 individual observations), considering the field players who start the match as starters and the rest of the players as non-starters.

2.2. Participants

Fourteen semi-professional female handball players from the same team participated voluntarily in this study. Playing positions were: wings (n = 4; age: 18.8±0.5 years; height: 162.0±3.8 cm; body mass: 55.5±4.3 kg), backs (n = 8; age: 22.4±4.2 years; height: 168.6±3.6 cm; body mass: 68.0±4.3 kg) and pivots (n = 2; age: 21.5±2.1 years; height: 169.0±2.8 cm; body mass: 75.5±11.5 kg). To classify their activity level and athletic ability, all players were classified as tier 3 ‘Highly Trained or National Level’, according to the ‘Participant Classification Framework’ provided by McKay et al. (2020). During the season, players typically completed four or five handball training sessions, two or three strength training sessions and one match per week. All players were informed of the study requirements and provided written informed consent prior to the start of the study. Additionally, all the ethical procedures used in this study were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Ethics Committee of the European University of Madrid (CIPI/18/195).

2.3. Internal Match-Load Quantification

Rate of perceived exertion (match-RPE) was used to determine the internal load of each official match. The 10-point Borg scale, in which 1 means ‘very light activity’ and 10 means ‘maximal exertion’ was applied. The match-RPE values are expressed in arbitrary units (a.u.). This method has demonstrated a good level of validity for monitoring internal load in handball players [

13].

2.4. Well-Being Quantification

The players’ well-being was monitored in MD+1 and MD+2 through a modified version of the Hooper questionnaire [

18,

24] with three categories: (i) fatigue; (ii) sleep and (iii) muscle soreness. The questionnaire employed a 7-point Likert scale for the three Hooper Scale categories. For fatigue and muscle soreness a rating of 1 means ‘very, very low’ and a rating of 7 means ‘very, very high’. For sleep, 1 means ’very, very good’ and 7 ’very, very bad’. Then, the overall Hooper Index of well-being was determined by summating the three subjective ratings. The values are expressed in arbitrary units (a.u.).

2.5. Procedures

As recommended by previous studies [

18], the researchers did not interfere with the normal training and competition process. Only the standardized process of completing the RPE and well-being questionnaires using a Google Forms were implemented by the researchers. To avoid potential interferences from hearing the scores of other teammates and synchronize the timing of their answers, the players received a link on their personal smartphone to access the match-RPE questionnaire 30 minutes after the end of the match [

25]. In the same way, as with match-RPE, to obtain well-being data the researchers sent the players a link to access the questionnaire on their personal smartphone every MD+1 and MD+2 at 9:00 a.m. The daily register of match-RPE and well-being data was made in a customized Excel spreadsheet. Before the commencement of the study, during the four weeks of pre-season, all players were familiarized with match-RPE and well-being questionnaire.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented as means and standard deviations (M ± SD). The level of significance was set at

p < 0.05. Before carrying out the analyses, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was performed to confirm data distribution normality and Levene’s test for equality of variances. Differences between player role (starter and non-starter) were determined by Mann-Whitney U test. Playing positions differences were determined by Kruskal-Wallis followed by the Dwass-Steel-Critchlow-Fligner test. Furthermore,

epsilon-squared (ε²) was calculated for group effects with the following interpretation: >0.01

small, >0.06

moderate, and >0.14

large [

26]. For the post-hoc analysis, Cohen’s d (ES) was calculated and interpreted using Hopkins’ categorization criteria:

d > 0.2 as

small,

d > 0.6 as

moderate d > 1.2 as

large, and

d > 2.0 as

very large [

27]. Data analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows (Version 26, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

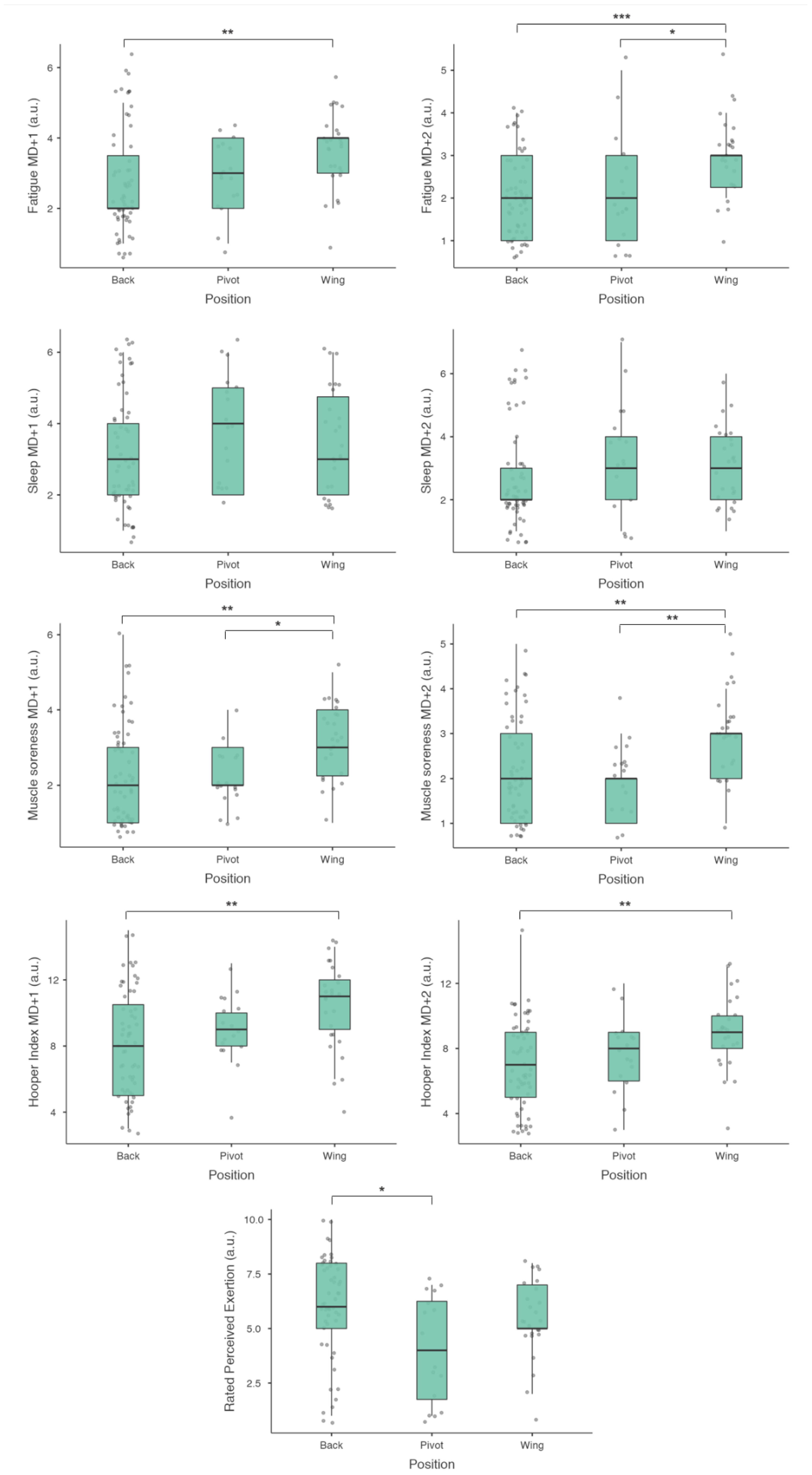

3.1. Playing Positions

There were significant differences with moderate to large effect sizes between playing positions in match-RPE (p < 0.01, ε² = 0.084), fatigue MD+1 (p < 0.01, ε² = 0.093), fatigue MD+2 (p < 0.001, ε² = 0.154), muscle soreness MD+1 (p < 0.01, ε² = 0.120), muscle soreness MD+2 (p < 0.01, ε² = 0.123), Hooper index MD+1 (p < 0.01, ε² = 0.092) and Hooper index MD+2 (p < 0.05, ε² = 0.099) (

Figure 2). More specifically, backs registered moderately more match-RPE (6.01 ± 2.34 a.u.) compared to pivots (4.12 ± 2.47 a.u.) (

p < 0.05, ES = 0.84). In relation to well-being responses, wings experienced moderately more fatigue in MD+1 (3.65 ± 1.12 a.u.) compared to backs (2.77 ± 1.45 a.u.) (

p = 0.009, ES = 0.66). Also, wings registered moderately more fatigue in MD+2 (2.96 ± 0.87 a.u.) than backs (2.03 ± 0.99 a.u.) and pivots (2.17 ± 1.13 a.u.) (

p < 0.001, ES = 0.93;

p < 0.05, ES = 0.79, respectively). Likewise, wings reported moderately more muscle soreness in MD+1 (3.15 ± 0.96 a.u.) and MD+2 (2.96 ± 0.95 a.u.) than backs (2.27 ± 1.32 a.u.,

p = 0.004, ES = 0.75; 2.15 ± 1.12 a.u.;

p = 0.004, ES = 0.77, respectively) and pivots (2.23 ± 0.83 a.u.,

p < 0.05, ES = 0.78; 2.00 ± 0.86 a.u.;

p = 0.006, ES = 0.91, respectively). Lastly, wings reported moderately more Hooper index in MD+1 (10.34 ± 2.66 a.u.) and MD+2 (9.00 ± 2.28 a.u.) than backs (8.20 ± 3.19 a.u., 7.00 ± 2.74 a.u., respectively) (

p = 0.006, ES = 0.73;

p = 0.004, ES = 0.77, respectively).

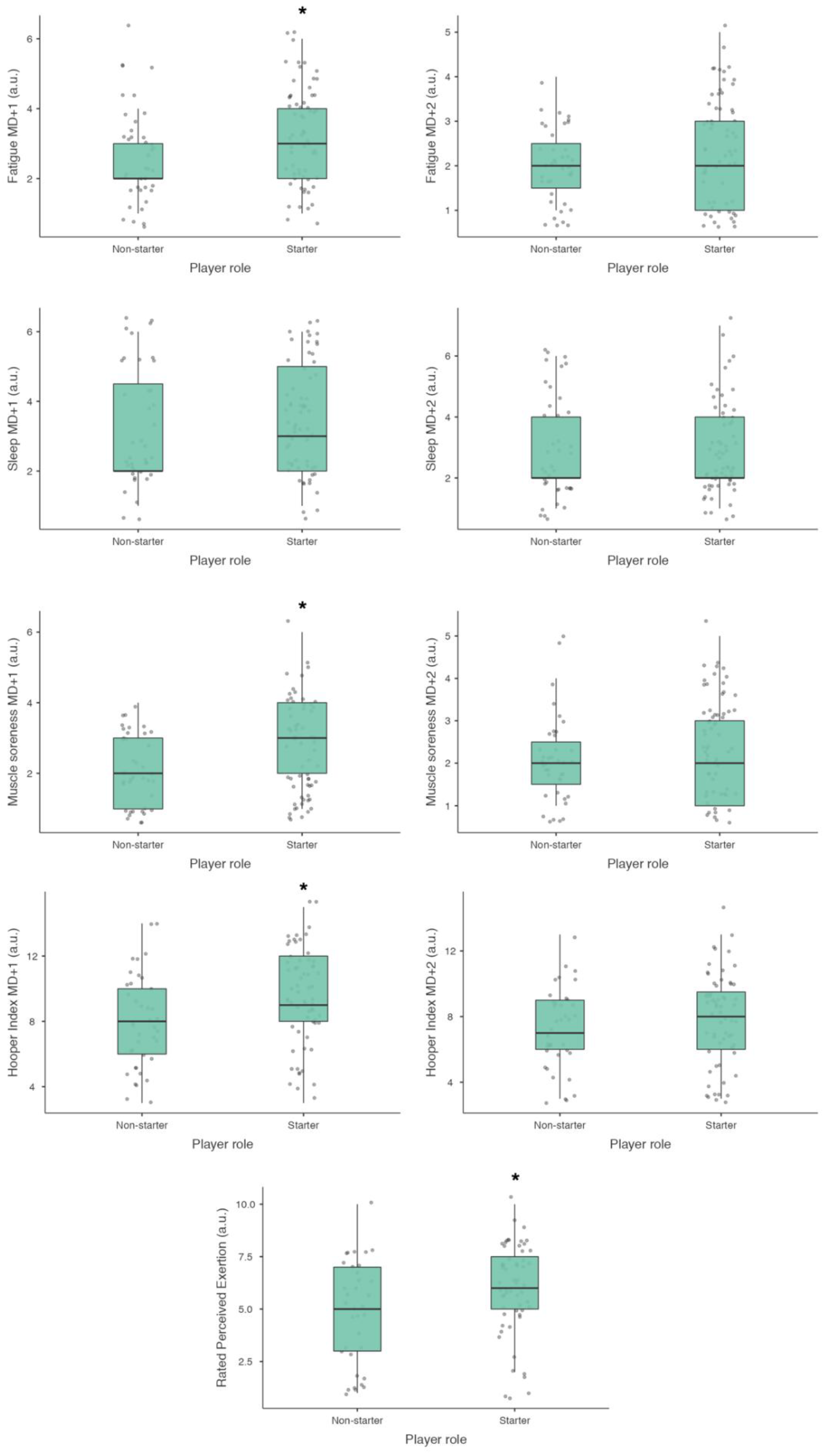

3.2. Player Role

There were significant differences between starter and non-starter players with small effect sizes in match-RPE (

p < 0.05, ES = 0.25), fatigue MD+1 (

p < 0.05, ES = 0.24), muscle soreness MD+1 (

p < 0.05, ES = 0.24) and Hooper index MD+1 (

p < 0.05, ES = 0.29) (

Figure 3). Particularly, starters evidenced a small increase in match-RPE (5.96 ± 2.07 a.u.) compared to non-starters (4.85 ± 2.55 a.u.) (

p = 0.036, ES = 0.25). In relation to well-being responses, starters reported slightly more fatigue (3.23 ± 1.36 a.u.), muscle soreness (2.71 ± 1.32 a.u.) and Hooper index (9.46 ± 2.95 a.u.) in MD+1 compared to non-starters (2.66 ± 1.28 a.u.; 2.12 ± 0.95 a.u.; 7.94 ± 2.91 a.u., respectively) (

p = 0.036, ES = 0.24;

p = 0.031, ES = 0.24;

p = 0.012, ES = 0.29, respectively). However, no differences were found in MD+2

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to analyze the effects of playing position and player role on internal match-load and well-being status of female handball players after official matches. The main findings indicated that associated with playing positions indicated that: (1) backs registered moderately more match-RPE compared to pivots; (2) wings experienced moderately more fatigue in MD+1 than backs, and in MD+2 compared to backs and pivots; (3) wings reported moderately more muscle soreness in MD+1 and MD+2 than backs and pivots; (4) wings reported moderately more Hooper index in MD+1 and MD+2 than backs. Furthermore, the results connected to player role were as follows: (1) starters exhibited higher values of match-RPE than non-starters; (2) starters experienced moderately more fatigue, muscle soreness and Hooper index in MD+1 compared to non-starters.

In relation to playing positions, backs registered moderately more match-RPE compared to pivots. Similarly, previous research has observed that found that pivots reported the lowest match-RPE (i.e., internal load) compared to the other positions [

8]. These differences between pivots and backs could be explained by two reasons: (1) the rotation strategies. In many teams, pivots are the players involved only in the offensive phase due to their limited defensive ability or to fatigue management [

8]; (2) backs have a greater acceleration-deceleration load because they have the main responsibility of building up the positional attack, which is characterized by a constant “fixation movement” [

17]. In contrast, wings experienced the highest values of fatigue and muscle soreness in MD+1 and MD+2 compared to all other playing positions. It is difficult to compare our results with previous studies because there is a lack of scientific evidence comparing well-being fluctuations according to playing positions in handball. However, a possible explanation for this difference could reside in the combination of two factors: (1) wings have a critical role in counter attacks and, consequently, covered higher total distance and high-speed running distance compared to the other positions [

17,

28]; (2) wings covered more high-intensity braking distance than the other playing positions [

28]. This fact is associated with intense eccentric contractions that produce high neuromuscular fatigue and tissue damage, especially if these high braking forces cannot be dissipated and distributed efficiently [

29,

30]. Therefore, our findings suggest that handball coaches and practitioners should design and implement different recovery strategies for backs and wings to accelerate the biological recovery process in shorter time periods and to increase player availability, especially during periods of congested travel and competition schedules: (1) prescribing the optimal load during the first training sessions of the microcycle (MD+1 and MD+2) could be the first recovery strategy [

1]; (2) ensuring and promoting the implementation of primary recovery strategies (e.g., sleep, nutrition, hydration, massage and active recovery) [

31]; (3) applying emerging protocols and methodologies (e.g., foam roller, compression garments, water immersion or cryotherapy) considering player preferences and beliefs [

1]; (4) prescribing dietary supplements (e.g., protein, creatine and polyphenols) considering individual differences and needs [

32].

Regarding player role, starters reported higher absolute values of match-RPE, fatigue, muscle soreness and Hooper index in MD+1 compared to non-starters. Similarly, a study conducted with male handball players showed that muscle soreness of knee flexor and extensor increased postgame, peaked at 24 hours, and recovered thereafter [

33]. It must be noted that in this study no differentiation was made between starters and non-starters. Also, we found similar findings in previous studies conducted with elite female soccer players, where internal load was higher in players from the starting line-ups [

7]. Our results could be explained in part by the higher playing time and, consequently, the higher number of physical contacts, inflammatory responses and external load experienced by starters compared to non-starters, as indicated by previous researches [

22,

33,

34,

35]. Therefore, as in other team sports (e.g. soccer and basketball), these results highlight the need to implement different training interventions in MD+1 according to the player role (starter vs. non-starter) [

7,

18,

36]. More precisely, starters should focus on recovering from match-induced fatigue with different strategies (e.g., sleep, nutrition, hydration, massage and active recovery) and non-starters should incorporate compensatory training interventions that recreate in training the same intensities (distance/minute) as in the match to improve or at least maintain their sport-specific fitness level (e.g., repeated sprint training or on-court transition drills that promote a substantial volume of high-speed running and sprinting) [

37]. This approach enables to balance the workload of starters and non-starters across the microcycle [

37]. Nevertheless, some research indicates that these training sessions in MD+1 may not fully compensate for the match load, and from a long-term perspective, non-starter players could potentially be under-trained, especially considering high-intensity actions [

7,

21]. Furthermore, this situation could be aggravated if non-starters remain in that role for a long period of time [

37]. To overcome this challenge, handball coaches and practitioners should consider the playing time as an effective tool to distribute the match external load between a larger number of players and, consequently, to optimize the weekly load distribution [

35]. Apart from that, it should be also pointed out that no differences in match-RPE and well-being responses were found between starters and non-starters in MD+2. These results suggest that 2 days could be enough for the starters to recover from match-fatigue, as previously mentioned by Chatzinikolaou et al. (2014). Consequently, coaches and practitioners could implement the same training stimulus in MD+2 for all players. However, we should be especially cautious with wing players, as they report more fatigue and muscle soreness in MD+2 compared to backs and pivots.

Although this study provides usefulness information for handball coaches and practitioners, some limitations should be mentioned. First, the use of a very particular sample (i.e., a Spanish 2nd Division team) and not particularly large (n = 14). Second, internal match-load and recovery status were measured only via self-reported subjective ratings. Third, the well-being status was only collected during the two days after the match. Lastly, as it being an observational study, player rotations could not be controlled or influenced by researchers. Thus, coaches and practitioners should generalize and extrapolate the results with caution. In this regard, future research should include a larger number of teams and different levels of competition (e.g., national teams or first-division clubs) to verify the conclusions. Likewise, future studies should employ objective monitoring tools to analyze the internal match-load (e.g., heart rate or lactate) and post-match recovery (e.g., heart rate variability, serum creatine kinase, or countermovement jump). In addition, future studies should examine the recovery time-course for at least three days after the match.

5. Conclusions

The present study indicates that internal match-load and well-being responses reported by semi-professional female handball players after official matches are affected by playing positions and player role. In relation to playing positions, backs registered moderately more match-RPE compared to pivots. In contrast, wings experienced higher values of fatigue and muscle soreness in MD+1 and MD+2 compared to all other playing positions. Also, wings reported moderately more Hooper index in MD+1 and MD+2 than backs. Regarding player role, starters reported higher values of match-RPE, fatigue, muscle soreness and Hooper index in MD+1 compared to non-starters. However, no differences were found in MD+2. Therefore, handball coaches and practitioners should consider the internal match-load and the well-being status of the players to implement different training stimulus (e.g., recovery or compensatory strategies) in MD+1 according to playing positions and player role to equalize the total weekly load of the players.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.G-S.; methodology, C.G-S.; R.N.A.; software, C.G-S.; validation, C.G-S..; formal analysis, C.G-S.; R.N.A.; R.M.N.; A.d.l.R.; investigation, C.G-S.; R.M.N.; A.d.l.R.; resources, C.G-S.; data curation, C.G-S.; writing—original draft preparation, C.G-S.; writing—review and editing, C.G-S. R.N.A.; visualization, C.G-S.; supervision, R.N.A.; J.L-C; R.M.N.; M.M.N.; A.d.l.R.; project administration, C.G-S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of European University of Madrid (CIPI/18/195).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

This research belongs to an International Research Project: “Factores que determinan el rendimiento deportivo en la alta competición” (Ref: 10012023-DPD-m) and to a doctoral Thesis titled “Physical demands in women´s handball: influence of playing positions and contextual factors on match performance” developed under the supervision of the Sport and Training Research Group. The authors thank the Faculty of Physical Activity and Sport Sciences (INEF) and the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (UPM) for their support. Also, the authors thank all the players and technical staff of Balonmano iKasa for their predisposition and participation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Calleja-González J, Mallo J, Cos F, Sampaio J, Jones MT, Marqués-Jiménez D, et al. A commentary of factors related to player availability and its influence on performance in elite team sports. Front Sport Act Living. 2023;4(January):1–8. [CrossRef]

- Fox JL, Stanton R, Sargent C, Wintour SA, Scanlan AT. The Association Between Training Load and Performance in Team Sports: A Systematic Review. Vol. 48, Sports Medicine. Springer International Publishing; 2018. 2743–2774 p. [CrossRef]

- McLaren SJ, Macpherson TW, Coutts AJ, Hurst C, Spears IR, Weston M. The Relationships Between Internal and External Measures of Training Load and Intensity in Team Sports: A Meta-Analysis. Sport Med. 2018;48(3):641–58. [CrossRef]

- Impellizzeri FM, Shrier I, McLaren SJ, Coutts AJ, McCall A, Slattery K, et al. Understanding Training Load as Exposure and Dose. Sport Med. 2023;53(9):1667–79. [CrossRef]

- McLaren SJ, Shushan T, Schneider C, Ward P. Comment on Passfield et al: Validity of the Training-Load Concept. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2022;17(10):1467. [CrossRef]

- Drew MK, Finch CF. The Relationship Between Training Load and Injury, Illness and Soreness: A Systematic and Literature Review. Sport Med. 2016;46(6):861–83. [CrossRef]

- Romero-Moraleda B, González-García J, Morencos E, Giráldez-Costas V, Moya JM, Ramirez-Campillo R. Internal workload in elite female football players during the whole in-season: starters vs non-starters. Biol Sport. 2023;40(4):1107–15. [CrossRef]

- Font R, Karcher C, Loscos-Fàbregas E, Altarriba-Bartés A, Peña J, Vicens-Bordas J, et al. The effect of training schedule and playing positions on training loads and game demands in professional handball players. Biol Sport. 2023;40(3):857–66. [CrossRef]

- Bourdon PC, Cardinale M, Murray A, Gastin P, Kellmann M, Varley MC, et al. Monitoring athlete training loads: Consensus statement. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2017;12:161–70. [CrossRef]

- Boullosa D, Claudino JG, Fernandez-Fernandez J, Bok D, Loturco I, Stults-Kolehmainen M, et al. The Fine-Tuning Approach for Training Monitoring. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2023;18(12):1374–9. [CrossRef]

- Soligard T, Schwellnus M, Alonso JM, Bahr R, Clarsen B, Dijkstra HP, et al. How much is too much? (Part 1) International Olympic Committee consensus statement on load in sport and risk of injury. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(17):1030–41. [CrossRef]

- Gabbett TJ. The training—injury prevention paradox: should athletes be training smarter and harder? Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(5):273–80.

- Pedersen A, Randers MB, Luteberget LS, Møller M. Validity of Session Rating of Perceived Exertion for Measuring Training Load in Youth Team Handball Players. J Strength Cond Res. 2023;37(1):174–80. [CrossRef]

- Akenhead R, Nassis GP. Training load and player monitoring in high-level football: Current practice and perceptions. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2016;11(5):587–93. [CrossRef]

- Nobari H, Fani M, Pardos-Mainer E, Pérez-Gómez J. Fluctuations in well-being based on position in elite young soccer players during a full season. Healthc. 2021;9(5):1–12. [CrossRef]

- Rabbani A, Clemente FM, Kargarfard M, Chamari K. Match fatigue time-course assessment over four days: Usefulness of the hooper index and heart rate variability in professional soccer players. Front Physiol. 2019;10(FEB):1–8. [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez C, Navarro RM, Karcher C, de la Rubia A. Physical Demands during Official Competitions in Elite Handball: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(4). [CrossRef]

- Clemente F, Olivera H, Vaz T, Carriço S, Calvete F, Mendes B. Variations of perceived load and well-being between normal and congested weeks in elite case study handball team. Res s. 2019;27(3):412–23. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Chao A, Lorenzo A, Ribas C, Portes R, Leicht AS, Gómez-Ruano MA. Influence of analysis focus and playing time on internal average and peak physical demands of professional male basketball players during competition. Rev intenacional ciencias Deport. 2022;18(69). [CrossRef]

- Casamichana D, Martín-García A, Díaz AG, Bradley PS, Castellano J. Accumulative weekly load in a professional football team: With special reference to match playing time and game position. Biol Sport. 2021;39(1):115–24. [CrossRef]

- Varjan M, Hank M, Kalata M, Chmura P, Mala L, Zahalka F. Weekly Training Load Differences between Starting and Non-Starting Soccer Players. J Hum Kinet . 2024;90(2016):125–35. [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez C, Karcher C, Navarro RM, Nieto-Acevedo R, Cañadas-García E, de la Rubia A. Same Training for Everyone? Effects of Playing Positions on Physical Demands During Official Matches in Women’s Handball. Montenegrin J Sport Sci Med. 2024;20(1):11–8. [CrossRef]

- Los Arcos A, Mendez-Villanueva A, Martínez-Santos R. In-season training periodization of professional soccer players. Biol Sport. 2017;34(2):149–55. [CrossRef]

- Hooper SL, Mackinnon LT. Monitoring Overtraining in Athletes: Recommendations. Sport Med. 1995;20(5):321–7.

- Foster C, Florhaug JA, Franklin J, Gottschall L, Hrovatin LA, Parker S, et al. A New Approach to Monitoring Exercise Training. Bioorganic Med Chem. 2001;15(1):109–15.

- Hopkins WG, Batterham AM. Spreadsheets for Analysis of Validity and Reliability. In 2015.

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Stat Power Anal Behav Sci. 2013;

- García-Sánchez C, Navarro RM, Mon-López D, Nieto-Acevedo R, Cañadas-García E, de la Rubia A. Do all matches require the same effort? Influence of contextual factors on physical demands during official female handball competitions. Biol Sport. 2024;145–54. [CrossRef]

- Harper DJ, Carling C, Kiely J. High-Intensity Acceleration and Deceleration Demands in Elite Team Sports Competitive Match Play: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Sport Med. 2019;49(12):1923–47. [CrossRef]

- Harper DJ, McBurnie AJ, Santos TD, Eriksrud O, Evans M, Cohen DD, et al. Biomechanical and Neuromuscular Performance Requirements of Horizontal Deceleration: A Review with Implications for Random Intermittent Multi-Directional Sports. Vol. 52, Sports Medicine. Springer International Publishing; 2022. 2321–2354 p. [CrossRef]

- Dupuy O, Douzi W, Theurot D, Bosquet L, Dugué B. An evidence-based approach for choosing post-exercise recovery techniques to reduce markers of muscle damage, Soreness, fatigue, and inflammation: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Front Physiol. 2018;9(APR):1–15. [CrossRef]

- Markus I, Constantini K, Hoffman JR, Bartolomei S, Gepner Y. Exercise-induced muscle damage: mechanism, assessment and nutritional factors to accelerate recovery. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2021;121(4):969–92.

- Chatzinikolaou A, Christoforidis C, Avloniti A, Draganidis D, Jamurtas AZ, Stampoulis T, et al. Amicrocycle of inflammation following a team handball game. 2014;28(7).

- Dello Iacono A, Eliakim A, Padulo J, Laver L, Ben-Zaken S, Meckel Y. Neuromuscular and inflammatory responses to handball small-sided games: the effects of physical contact. Scand J Med Sci Sport. 2017;27(10):1122–9. [CrossRef]

- Garca-Sánchez C, Navarro RM, Nieto-Acevedo R, De La Rubia A. Is Match Playing Time a Potential Tool for Managing Load in Women’s Handball? J Strength Cond Res. 2024;

- Oliveira R, Canário-Lemos R, Morgans R, Rafael-Moreira T, Vilaça-Alves J, Brito JP. Are non-starters accumulating enough load compared with starters? Examining load, wellness, and training/match ratios of a European professional soccer team. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil. 2023;15(1):1–11. [CrossRef]

- Clemente F, Pillitteri G, Palucci Vieira LH, Rabbani A, Zmijewski P, Beato M. Balancing the load: A narrative review with methodological implications of compensatory training strategies for non-starting soccer players. Biol Sport. 2024;173–85. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).