1. Introduction

The adhesion of biological cells and vesicles plays an important role in nature [

1]. The adhesion may result from attraction of the bilayer to other bilayer [

2,

3], to biomolecular condensates [

4,

5], or to various substrates [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. It takes place during endo- and exocytosis when cells communicate with their environment. It plays a crucial role in tissue morphogenesis, migration, self-recognition, the immune response, synapse formation and embryogenesis. The adhesion may be important in drug delivery by liposomes when they attach to the plasma membrane to release their content into the target sites. Here, we focus on the rearrangement of components in a lipid membrane due to the adhesion to a flat rigid substrate. We investigate the process in which the lateral distribution of membrane components is coupled to the shape of the membrane. During the adhesion the shape of cells or vesicles is changed and it may lead to the lateral segregation of membrane components. Such segregation is induced due to the coupling the spontaneous curvature of the membrane constituents with the local mean curvature of the membrane. Such segregation is induced due to the coupling of the local spontaneous curvature with the local mean curvature in the Helfrich energy.

Mathematical Model

It is assumed in the mathematical model that the membrane is composed of two components which are characterized by different spontaneous curvatures

where the index

denotes the type of the component:

A or

B. For simplicity the bending rigidities of both components are assumed to be equal

. We investigate the system with fixed topology, constant surface area

S, and volume

V and fixed total concentration of the component

A (

), defined as the fraction of the total surface area of the vesicle membrane occupied by the component A. Such a physical situation is well described by the functional [

15] given by:

where

and

are the principal curvatures,

is the local spontaneous curvature and the integral (

1) is taken over the surface of a closed vesicle.

is the function describing the local relative concentration of the component A. We assume a linear dependence of the membrane spontaneous curvature,

on the concentration

:

where

. No topology change is considered, therefore the integral over the Gaussian curvature contributes a constant value and is omitted in Equation (

1). In order to mimic the most common experimental conditions, the constraints of constant surface area

S and volume

V are imposed.

The vesicle shapes can be well approximated in numerical calculations by surfaces which have rotational symmetry. Therefore, the vesicles can be studied by parameterizing their shape with the angle between the line perpendicular to the rotation axis and the line tangent to the shape profile,

, as a function of the arclength s. The radius

and the height

of the shape profile are calculated from

according to:

In order to parameterize an adhered vesicle shape, the following constraints must be satisfied:

where

is the length of the free part of shape profile. The Eqs (

5) and (

6) guarantee that the profile is smooth at the ends and Equation (

7) determines the radius of adhesion

, defined as a distance from the axis of rotation to the place where the surface of the vesicle deflects from the flat substrate.

The functional (

1) with the shape profile parametrized by

is given by:

The functional (

8) is minimized numerically. The function describing the shape profile

is composed of two parts. The surface of the vesicle which is not attached to a substrate (

) is approximated by the Fourier series,

where

N is the number of Fourier modes, and

are the Fourier amplitudes. Large number of the amplitudes, of the order of one hundred, is required in order to accurately parameterize complex shapes.

is the angle tangent to the shape profile at the point where the membrane deflects from the substrate,

. We can define this angle as the contact angle and assume that it is

in order to keep the profile of the vesicle smooth at all points. In the range

the function

which means that the shape profile is a horizontal line extending from

to

. The value

is used to define the contact area,

A, given by

. Thus, we can define

as an adhesion radius. The functional variation is replaced by the minimization of the function of many variables [

16]. The local concentration of the component A is approximated by the function:

The function (

8) is minimized with respect to the amplitudes

and the length of the shape profile

, and the parameters

,

,

,

under the constraint of constant surface area

S and volume

V, and adhesion radius

R where

The volume (

) and the radius (

) of the sphere having the same surface area (

S) as the investigated vesicle are :

The reduced volume [

7,

17] is defined as

, the reduced spontaneous curvatures

, the reduced free energy

, and the reduced adhesion radius

.

2. Results and Discussion

The stability of vesicles and the lateral distribution of components

due to the change of the adhesion radius

is investigated. The components are characterized by the spontaneous curvatures

and

. Such large difference in the spontaneous curvature facilitates the curvature induced segregation of the components. The total concentration of the curved component

A was chosen as

and the reduced volume

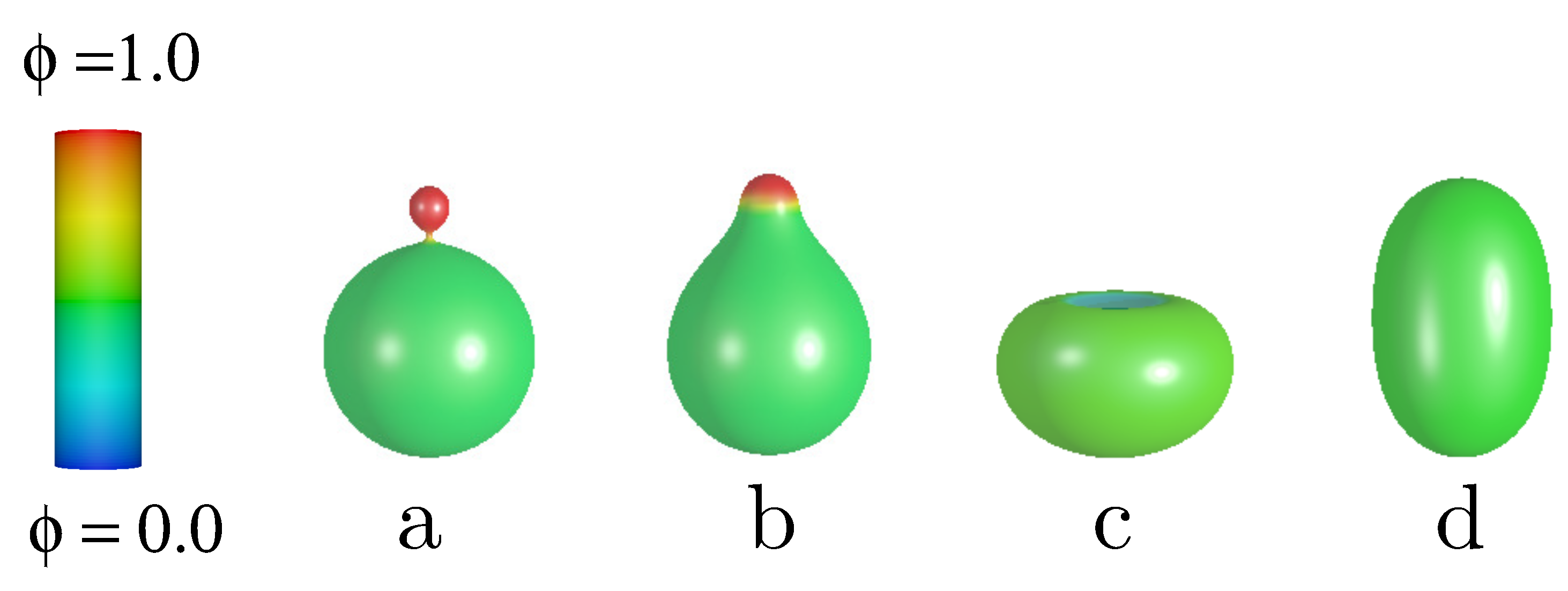

. We have decided to investigate vesicles with relatively large reduced volume because for such vesicles the number of different classes of shapes is relatively small and the system is still interesting to investigate. In

Figure 1 different classes of free vesicle shapes are presented. In the first two shapes in

Figure 1, the component with larger spontaneous curvature is accumulated at the north pole of the vesicle, forming a caplet or a spherical bud. The lowest energy shape in

Figure 1 for the reduced volume

is the one with a spherical bud,

Figure 1a. The configuration with a caplet (

Figure 1b) has the lowest energy for higher values of the reduced volume

[

15]. We have also obtained the lateral distribution with completely mixed components and a very interesting solution with the region at the north pole occupied mainly by the component with the lower spontaneous curvature. Such a distribution of the components results in an concave region at the north pole of the invaginated vesicle, resembling a stomatocyte (

Figure 1c).

The membrane components are segregated because the equilibrium vesicle shapes have the regions of different mean curvature. Thus, the components with larger and smaller spontaneous curvature are accumulated in the high and low mean curvature regions, respectively. It should be noted that in the case of free vesicles the regions with high and low mean curvatures are formed spontaneously in the process where the shape of the vesicle and the lateral distribution of components are driven by minimization of the bending energy. The role of the mixing entropy is neglected in the current study due to simplicity. The role of direct interactions between the membrane components is also neglected [

18,

19,

20].

During adhesion to a flat substrate the shape of a vesicle changes in such a way that near the substrate both low and high mean curvature regions are formed. The membrane part that is attached to a flat substrate has zero mean curvature. The bilayer at the rim of the adhered region has non-zero mean curvature. The value of the mean curvature of the membrane at the rim is related to the size of the the adhered region. In general the larger the size of the adhered membrane the higher the mean curvature at the rim is generated. By varying the size of the adhered bilayer surface area, the ratio of the surface areas of the regions with low and high mean curvature is varied. Moreover, the mean curvature of the membrane in the rim region gets larger with the increasing surface area of the adhered part of the membrane.

Figure 1.

The calculated shapes of free vesicles for the reduced volume and the total concentration of the A component, .

Figure 1.

The calculated shapes of free vesicles for the reduced volume and the total concentration of the A component, .

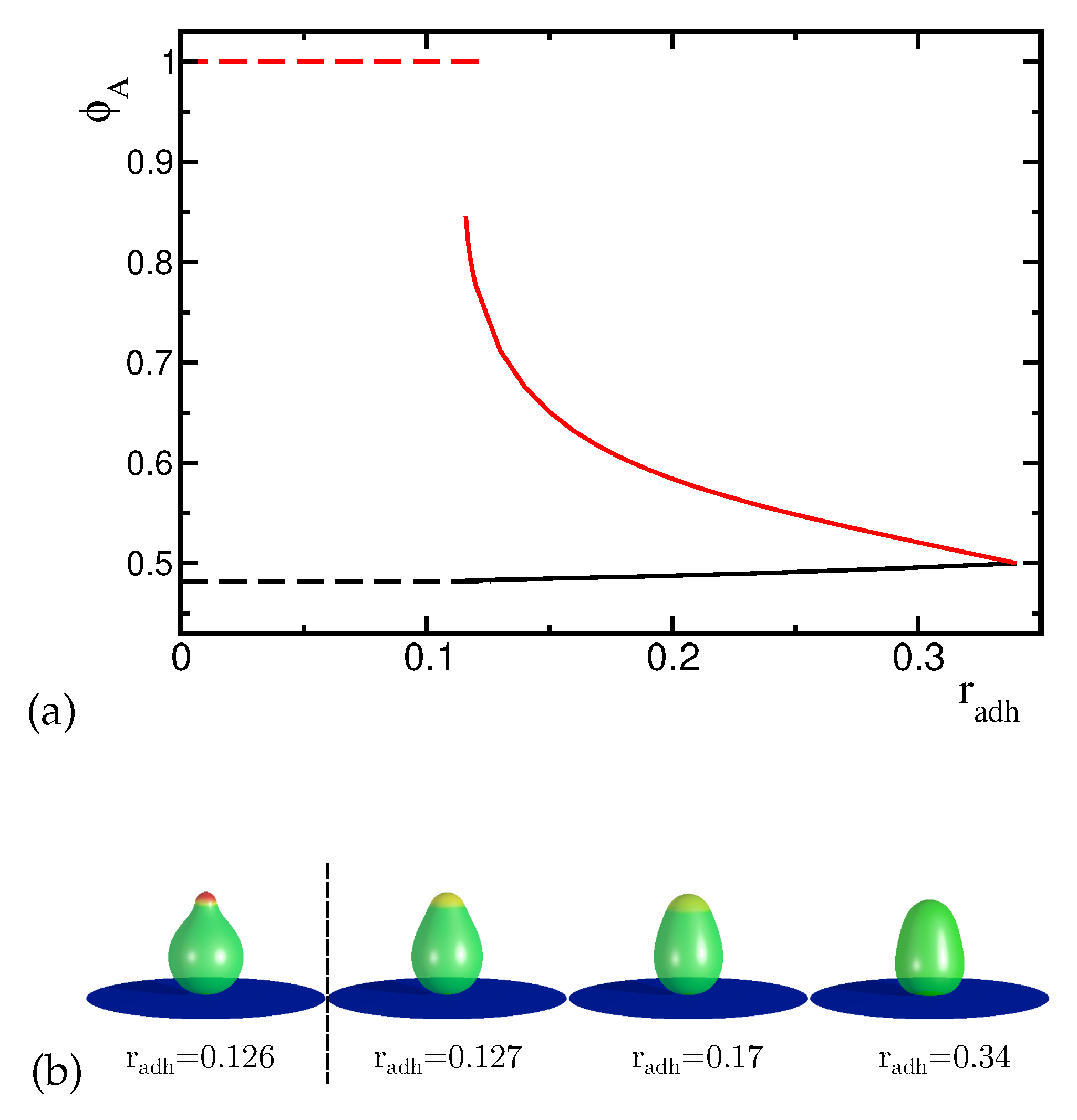

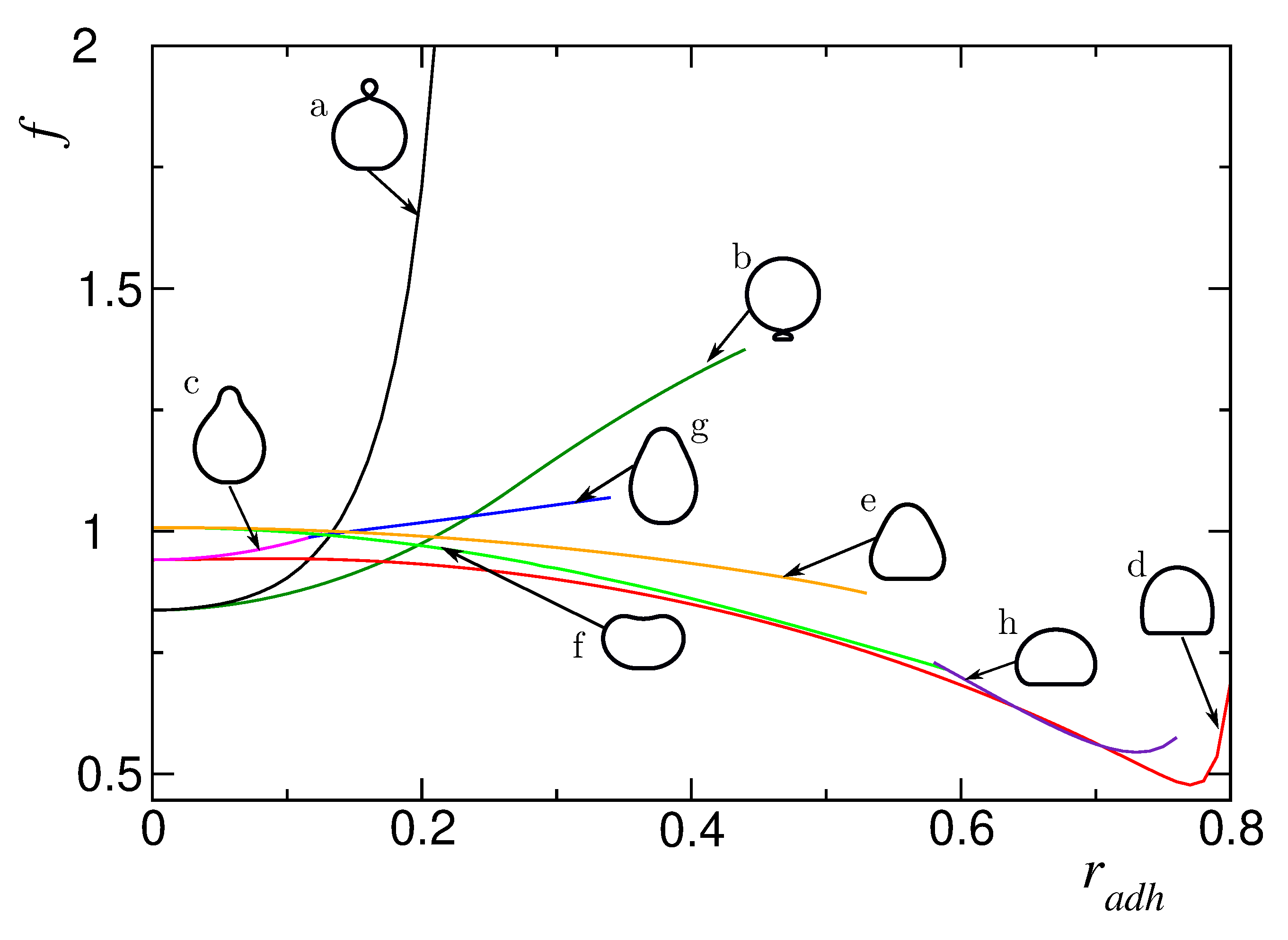

We have discovered 8 classes of adhered vesicle shapes. They are distinguished by different lines in the plot of the energy as a function of the adhesion radius as presented in

Figure 2. Six types of the calculated shapes of adsorbed vesicles originate from the classes of shapes of the free vesicles presented in

Figure 1. The seventh and eighth class (see

Figure 2g,h ) are oblate and pear-like shapes that exist only at larger values of the adhesion radius. They are characterized by different lateral distribution of the membrane components.

Different types of the calculated adhered vesicle shapes exist for different ranges of the adhesion radius

, as shown in

Figure 2. The adhered vesicles that originated from the pear down configuration have the largest range of stability. It should be noted that their shape is transformed continuously from pear like at small

to oblate like at large

(see

Figure 2).

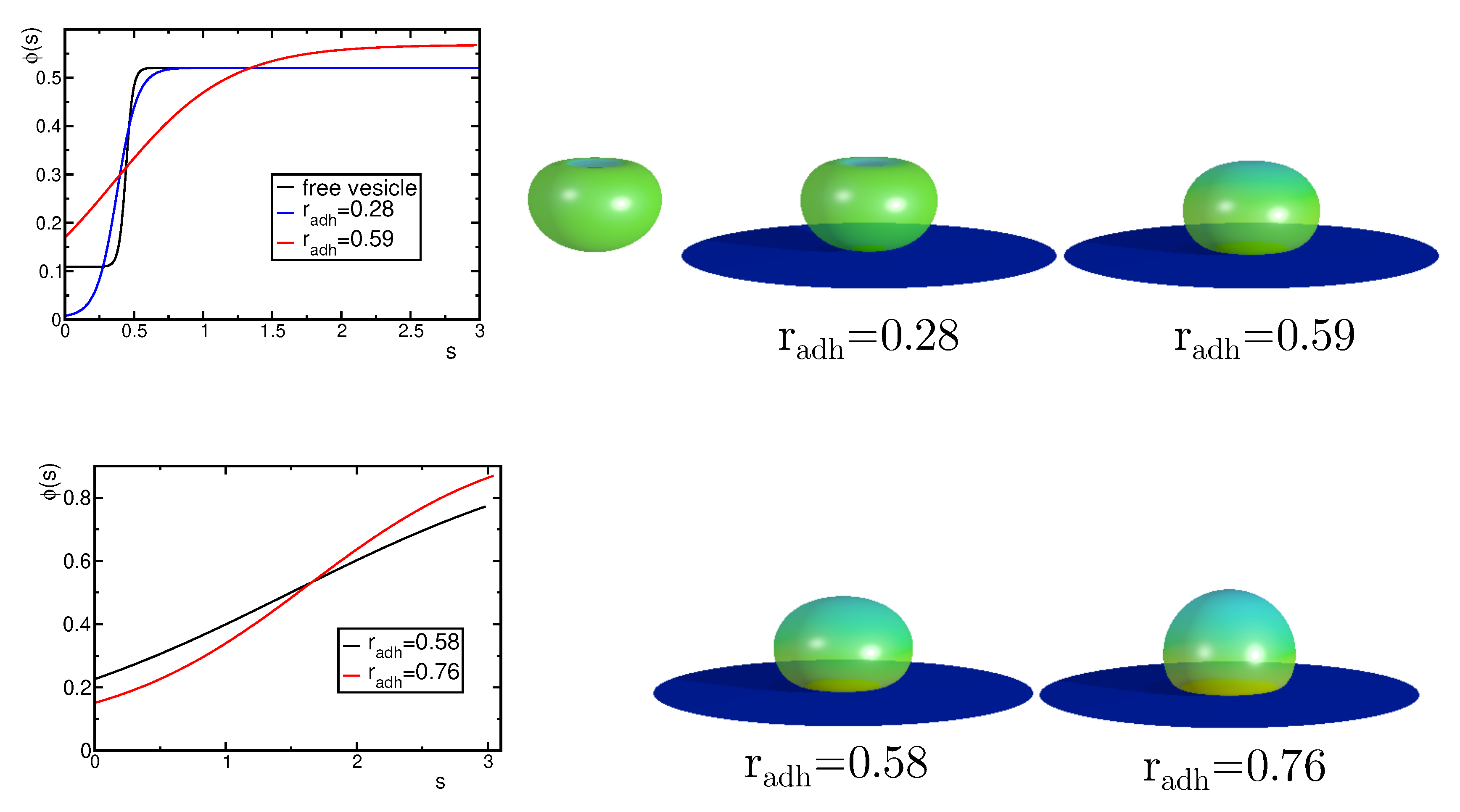

2.1. Oblate Vesicles

Free oblate vesicles are not expected to be stable when the concentration of the component with high spontaneous curvature is large in the membrane, usually prolate vesicles are the stable ones. However, they are expected to be stable when the surface area of adsorption is getting larger and larger. We have found two types of stable adsorbed oblate vesicles. The first one originates from the solution for the free vesicle (

) and extends from the radius of adhesion

to

. The second type of oblate adhered vesicles extends from

to

. These two types have different distribution of components. In the first type, the well defined domains with different concentrations are clearly distinguished for the small values of the adhesion radius. At the north pole of the vesicle the spherical domain with higher lateral relative concentration of the component with the smaller spontaneous curvature is formed. The components are distributed uniformly in each domains. The boundary region between the domains is very narrow. The width of the boundary regions is increasing with the increase of the adhesion radius

, as shown in

Figure 3. For larger adhesion radii, the local concentration of both components changes gradually and the domains of constant concentration cannot be distinguished. The interplay between the vesicle’s shape and the lateral distribution of both components is clearly illustrated in this case. The change of the concentration at the north pole of the vesicle is correlated with the variation of the vesicle’s shape induced by the adhesion.

The second type of oblate vesicle is characterized by almost constant gradient of the local concentration from the north to the south pole of the vesicle with larger concentration of the component with high spontaneous curvature at the substrate, as shown in

Figure 3. Such vesicles exist only at large adhesion radii. It should be noted that there is a range of the adhesion radius where the solution for two classes of oblate-shaped vesicles can be obtained. These two classes of vesicles’ shapes are pictured in

Figure 3 in the first and second row of the presented shapes. Moreover, for one value of the adhesion radius

the adhered oblate vesicles of both types have the same energy. This implies the possibility of very interesting physical phenomenon. In our model the lateral distribution of the membrane components influences the shape of the vesicle and vice versa. Thus, we can speculate that small changes of the shape of the vesicle may result in the change of the lateral distribution of the components that is equivalent to the transition from one type of the adhered oblate vesicles to the other, as shown in

Figure 3 for

and

.

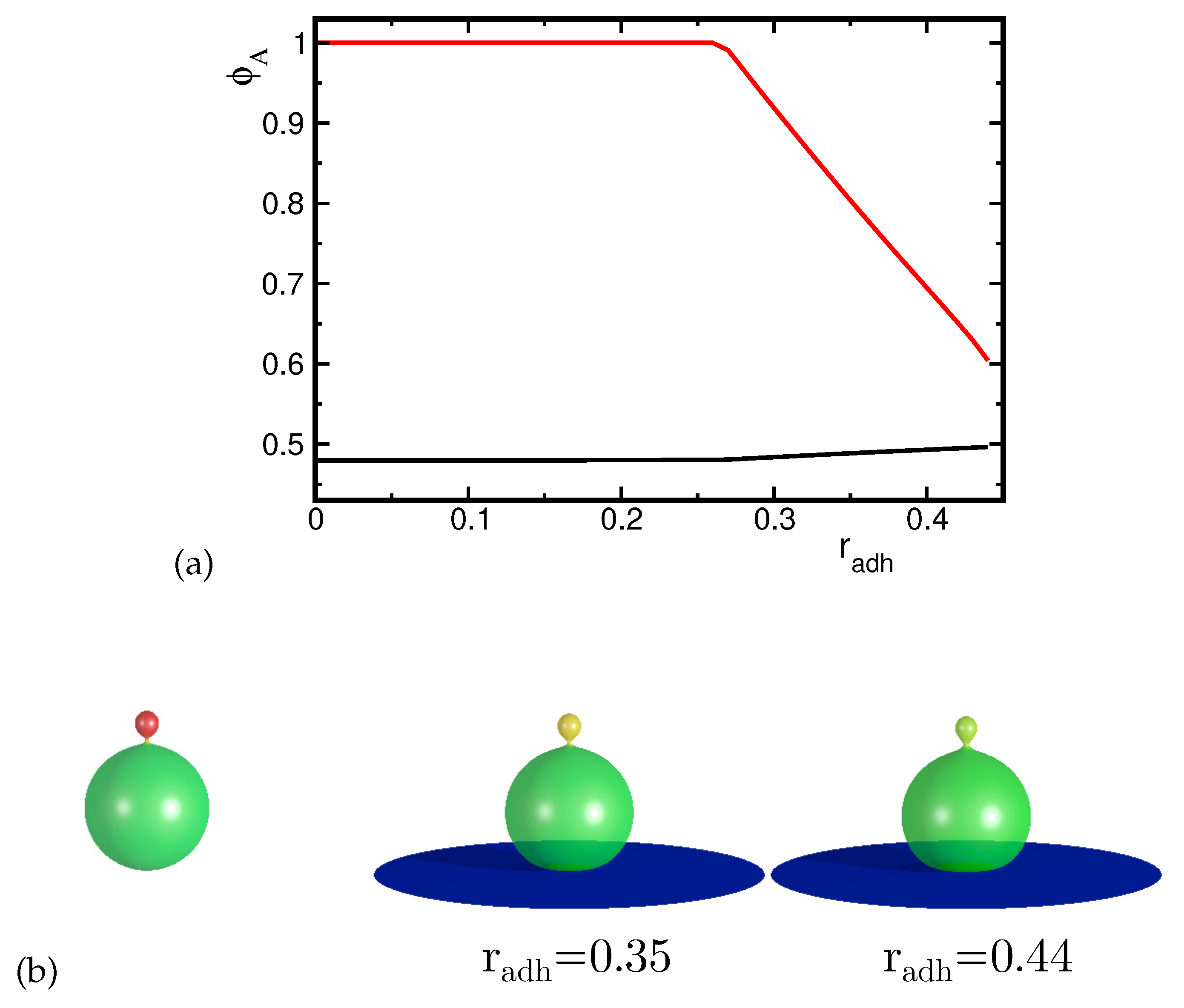

2.2. Pear-Like Vesicles

It can be expected that for sufficiently large adhesion radius, the adhered vesicles have oblate shapes. However, it is not obvious how the evolution of the vesicle shape and the corresponding lateral distribution of both components with increasing adhesion radius will look like if we start from a non-oblate vesicle shape. In the case of pear-like vesicle shapes (

Figure 1a,b) there are two possible ways to attach a vesicle to the substrate since they do not have up-down symmetry. Thus, two different classes of adsorbed vesicles’ shapes can be formed by attaching them to the substrate at the north or at the south pole. For the case of the pear-like configuration attached to the substrate at the narrower end where the component with high spontaneous curvature forms a circular domain (see

Figure 4), the transformation is smooth. The local concentration of the high curvature components in the domains is uniform and the domains are separated by a well defined narrow boundary. It is interesting to note that the concentration of the high spontaneous curvature component is always larger in the region of the vesicle attached to the substrate (both in the rim and in the adhered part of the vesicle) than in the remaining part of the vesicle even for a large adhesion radius. The domain of the high spontaneous curvature component becomes larger with the increase of the adhesion radius. We also see the accumulation of this component on the substrate and at the rim of the adhered part of the vesicle. The mean curvature at the rim becomes higher for larger adhesion radius and the area of the vesicles with high mean curvature increases. Thus, it is natural that the high spontaneous curvature component is accumulated near the substrate. For the adhered vesicles with large reduced volume, the change of the distribution of components in the membrane is induced mainly by the change of the vesicles’ shape with respect to the adhesion radius. It should be noted that by increasing the adhesion radius, the vesicle is smoothly transformed from pear-like shape to prolate and finally to oblate shape, as shown in

Figure 4.

The vesicle shapes close to the stability limit are almost equal to sections of a sphere as it can be expected for the limiting shape composed of spherical, tubular and toroidal sections [

8,

21]. From our calculations, it follows that this is the stable configuration for the largest adhesion radius. Similar configurations are obtained for one component vesicles where the spontaneous curvature is distributed uniformly over the vesicle’s surface. It should be noted that the increase of the spontaneous curvature enhances adhesion of one component vesicles to flat substrates [

22].

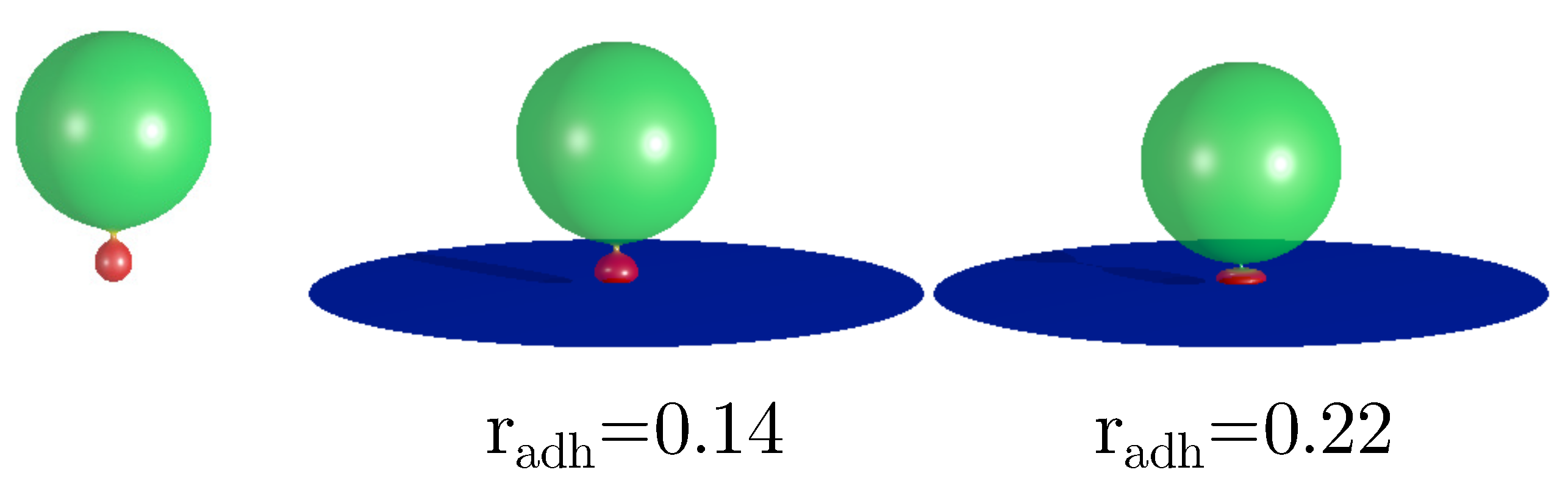

When the wider end of the pear-like vesicle is attached to the substrate (see

Figure 5b) the concentration profile changes with the increase of the adhesion radius in a different way than in the previous case. The components are distributed between two domains with higher and lower concentration. The distribution of the components in the domains is uniform and boundary region between the domains is narrow. The distribution of the components remains uniform for all the values of the adhesion radius, as shown in

Figure 5. Moreover, for small values of the adhesion radius the concentration profile remains very similar despite the adhesion of the larger pieces of the vesicle to the substrate. Such behavior is observed for

.

Figure 4.

(a) The change of the maximal concentration of the A component (i.e. highly curved component) in the upper and lower part of the vesicles induced by the increase of the adhesion radius . The red and black curves describe the concentration dependence in the lower and upper part of the vesicles respectively. (b) The calculated shapes of the adhered vesicles for the reduced volume and the concentration of the A component for different adhesion radius .

Figure 4.

(a) The change of the maximal concentration of the A component (i.e. highly curved component) in the upper and lower part of the vesicles induced by the increase of the adhesion radius . The red and black curves describe the concentration dependence in the lower and upper part of the vesicles respectively. (b) The calculated shapes of the adhered vesicles for the reduced volume and the concentration of the A component for different adhesion radius .

Figure 5.

(a) The change of the maximal concentration of the A component in the upper and lower part of the vesicles induced by the increase of the adhesion radius . The dashed lines denote the maximal concentration of the component with higher spontaneous curvature for the concave shapes and the solid lines denote the maximal concentration for the convex shapes. (b) The presented shapes of the adhered vesicles were calculated for the reduced volume and the concentration of the A component .

Figure 5.

(a) The change of the maximal concentration of the A component in the upper and lower part of the vesicles induced by the increase of the adhesion radius . The dashed lines denote the maximal concentration of the component with higher spontaneous curvature for the concave shapes and the solid lines denote the maximal concentration for the convex shapes. (b) The presented shapes of the adhered vesicles were calculated for the reduced volume and the concentration of the A component .

At

there is a discontinuous transition to a new configuration which is characterized by slightly wider upper end of the vesicle and different distribution of components with smaller concentration of the high spontaneous curvature component in the circular domain, as shown in

Figure 5. When the adhesion radius increases the shape and the lateral distribution of components are significantly altered. The concentration of the high curvature component decreases in the circular domain at the top of the vesicle. The boundary between the domains (i.e. between the top domain and the rest of the membrane) is still narrow and well defined despite smaller and smaller difference in the concentration in the two neighboring domains (see

Figure 5). At the end (i.e. for larger

values) the concentration is uniform over the whole vesicle. The limiting configuration at

is unique in a sense that the components are distributed uniformly over the whole vesicle, despite the shape asymmetry induced by the substrate (see

Figure 5, last shape in the (b) panel). When the adhesion radius decreases, the components become non-uniformly distributed. Similar phenomenon has been discovered when the shape of two components vesicles was altered by decreasing the reduced volume [

15].

These two types of configurations (convex and concave shapes) described above (see

Fig 5b) exist for two ranges of the adhesion radius. We can distinguish two curves in an energy plot representing the vesicles in these two types of configurations. In the first range from

to

the concentration of the high curvature component remains high and the shape does not change much. In the second range from

to

the concentration of the high curvature component is lower than before and it is decreasing with the increasing radius of adhesion. There is a small region where two solutions with different shapes and concentration profiles can be obtained. The energy curves intersect at

indicating that the transition between these two types of solutions is discontinuous.

2.3. Pear-Like Vesicles with a Narrow Neck

The vesicle composed of two approximately spherical parts of different sizes connected by a narrow neck is the configuration with the lowest energy for the parameter set we investigate. The component with the high curvature is preferentially accumulated in the smaller spherical part of the vesicle. In both parts the components are uniformly distributed. The boundary between high and low concentration region is placed at the neck. Such vesicles can be attached to the substrate from the side of the smaller or larger sphere. The adhesion process strongly depends on how the vesicle is attached.

First, we consider the case where the vesicle is attached to the substrate at the larger sphere. By varying the adhesion radius, we can change the shape of the vesicle and the distribution of the components. We observe only small changes of the neck radius when the adhesion radius gets longer. It is interesting to note that the concentration of components remains uniform in two parts of the vesicle separated by a narrow neck and the boundary between high and low concentration regions is always located on the neck. Initially, in the range of the adhesion radius

there is almost no change of the concentration profile. However, when the change of the shape due to adhesion becomes more pronounced for

the concentration of the high curvature component in the smaller sphere decreases. We also notice that the size of the smaller sphere decreases due to adhesion of larger and larger parts of the vesicles to the substrate. At the rim of the adhered vesicle’s surface, the region with high mean curvature is formed. The formation of this high mean curvature region causes redistribution of the components, as shown ig

Figure 6. Thus, the high spontaneous curvature components are moved from the small spherical part towards the rim of the adhered part of the vesicle. With increasing adhesion radius, the high mean curvature region is increasing and attracts the high curvature components.

When the smaller spherical part adheres to the substrate, the shape of a vesicle changes mainly in this part, see

Figure 7. The large upper spherical part separated by the narrow neck remains almost unchanged and the neck gets narrower when the radius of adhesion increases. Such transformations result in an increase of the energy because due to the deformations, the elastic energy is increasing and its growth is not compensated by the adhesion energy, since the size of the adhesion radius is limited by the size of the smaller sphere attached to the substrate. It may be expected that in the end, it will lead to the fission of the vesicle. The distribution of the components remains almost unchanged despite significant deformations of the small spherical part attached to the substrate. The concentration of the high curvature component at the substrate remains high for all values of the adhesion radius. These deformations cause the increase of the mean curvature at the rim of the adhered part of the vesicle and are restricted to a very small part of it. Thus, there is not sufficient driving force to induce the redistribution of the components due to adhesion.

When the vesicle is attached to the substrate with a smaller sphere, the shape deformations due to adhesion result in a rapid increase of the bending energy. In the case of the shape deformations when the larger sphere is attached, the energy increase is comparatively smaller. It is also interesting to observe that the neck connecting the spheres can be widened or narrowed, depending on side of the vesicle attached to the substrate.

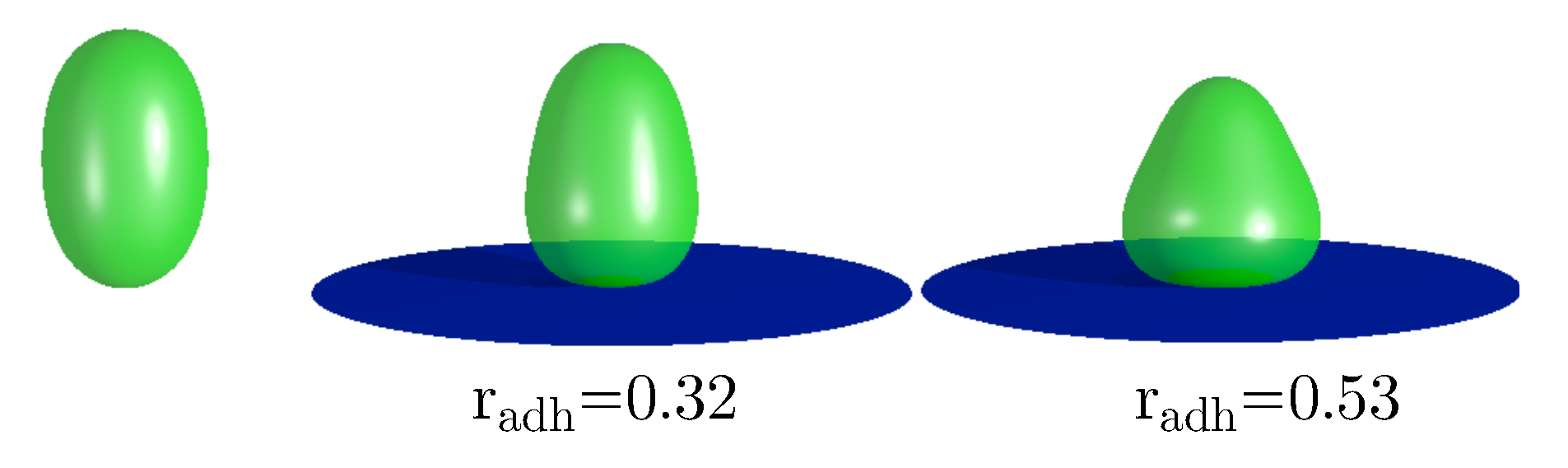

2.4. Prolate Vesicles

It is interesting to consider the stability of the vesicle with completely mixed components. We have found that such vesicles are stable in the range of the adhesion radii from r=0.0 to r=0.53, as shown in

Figure 8. Outside this range only the vesicles with the segregated components are stable. It can be expected that the shape deformations caused by adhesion induce the separation of components. For small adhesion radius the configurations with completely mixed components can still be metastable. However, when the deformations induce larger and larger differences in the local mean curvatures on the surface of the vesicles, the tendency to separate the components should increase. The region of high local mean curvature is formed at the rim of the adhered vesicle. The size of this region depends on the adhesion radius. Moreover, the value of the local mean curvature at the rim of the adhered vesicle also depends on the adhesion radius. From the studied mathematical model we can calculate that the radius r=0.53 is in the region where the configurations with completely mixed components become unstable. Thus, we may speculate that the adhesion process can be used to segregate the membrane components in the biological cells. Such curvature based sorting can be also induced when the shape deformations of a vesicle are induced by a microtubule or by the change of osmotic pressure [

15].

3. Summary and Conclusions

The adhesion of two-component vesicles to a flat substrate has been investigated. The coupling of the vesicle’s shape with the lateral distribution of the membrane components has been examined. The predicted segregation of the membrane components induced by the curvature of the membrane has been studied for a few types of vesicles’ shape classes (prolate, oblate, pear-like). It has been shown that during the adhesion the membrane components can be mixed or demixed. The degree of the segregation of the membrane components depends on the size of the surface area of the membrane attached to the substrate. The adhesion of cells may induce novel and very interesting phenomena in large collection of cells in biological tissue or in artificial cell cultures. The results of our calculations may be thus useful in explanation of the behavior of cell cultures confined and grown on a flat substrate [

23].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.G. and A.I.; methodology, W.G. and A.I.; software, J.R. and W.G.; validation, J.R., B.L., A.I. and W.G.; formal analysis, J.R., A.I, B.L. and W.G.; investigation, J.R., A.I., B.L. and W.G.; resources, W.G.; data curation, J.R., W.G.; writing—original draft preparation, J.R.,W.G.; writing—review and editing, J.R.,A.I.,W.G.,B.L.; visualization, J.R.,W.G.; supervision, W.G.,A.I.; project administration, W.G.,A.I.,B.L.; funding acquisition, W.G.,A.I,B.L.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

WG was supported by NCN grant No 2018/30/Q/ST3/00434. AI was supported by the Slovenian Research Agency (ARIS) through Grants Nos. J3-3066, J2-4447 and P2-0232

Data Availability Statement

The data is available upon a request from the authors (J.R., W.G.).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gordon, V.D.; O’Halloran, T.J.; Shindell, O. Membrane adhesion and the formation of heterogeneities: biology, biophysics, and biotechnology. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 15522–15533. [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, A.; Anderson, T.H.; Leal, L.G.; Israelachvili, J.N. Adhesive Interactions between Vesicles in the Strong Adhesion Limit. Langmuir 2011, 27, 59–73. [CrossRef]

- Mareš, T.; Daniel, M.; Iglič, A.; Kralj-Iglič, V.; Fošnarič, M. Determination of the Strength of Adhesion between Lipid Vesicles. The Scientific World Journal 2012, 2012, 146804. [CrossRef]

- Satarifard, V.; Lipowsky, R. Mutual remodeling of interacting nanodroplets and vesicles. Communications Physics 2023, 6, 6. [CrossRef]

- Lipowsky, R. Remodeling of Biomembranes and Vesicles by Adhesion of Condensate Droplets. Membranes 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Evans, E. Analysis of adhesion of large vesicles to surfaces. Biophysical Journal 1980, 31, 425–431. [CrossRef]

- Seifert, U.; Lipowsky, R. Adhesion of vesicles. Phys. Rev. A 1990, 42, 4768–4771. [CrossRef]

- Seifert, U. Adhesion of vesicles in two dimensions. Phys. Rev. A 1991, 43, 6803–6814. [CrossRef]

- Raval, J.; Góźdź, W.T. Shape Transformations of Vesicles Induced by Their Adhesion to Flat Surfaces. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 16099–16105. [CrossRef]

- Bibissidis, N.; Betlem, K.; Cordoyiannis, G.; von Bonhorst, F.P.; Goole, J.; Raval, J.; Daniel, M.; Góźdź, W.; Iglič, A.; Losada-Pérez, P. Correlation between adhesion strength and phase behaviour in solid-supported lipid membranes. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2020, 320, 114492. [CrossRef]

- Weissenfeld, F.; Wesenberg, L.; Nakahata, M.; Müller, M.; Tanaka, M. Modulation of wetting of stimulus responsive polymer brushes by lipid vesicles: experiments and simulations. Soft Matter 2023, 19, 2491–2504.

[CrossRef]

- Wesenberg, L.; Müller, M. Role of Interaction Range and Buoyancy on the Adhesion of Vesicles. Langmuir 2024, 40, 3376–3390. [CrossRef]

- Stotsky, J.A.; Othmer, H.G. The effects of internal forces and membrane heterogeneity on three-dimensional cell shapes. Journal of Mathematical Biology 2023, 86, 1. [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Lv, C.; Feng, X.Q. Curvature-dependent adhesion of vesicles. Phys. Rev. E 2023, 107, 024405. [CrossRef]

- Góźdź, W.T.; Bobrovska, N.; Ciach, A. Separation of components in lipid membranes induced by shape transformation. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2012, 137, 015101. [CrossRef]

- Góźdź, W.T. Spontaneous Curvature Induced Shape Transformations of Tubular Polymersomes. Langmuir 2004, 20, 7385–7391. [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Fourcade, B.; Rao, M.; Wortis, M.; Zia, R.K.P. Equilibrium budding and vesiculation in the curvature model of fluid lipid vesicles. Phys. Rev. A 1991, 43, 6843–6856. [CrossRef]

- Markin, V. Lateral organization of membranes and cell shapes. Biophysical journal 1981, 36, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Kralj-Iglič, V.; Babnik, B.; Gauger, D.R.; May, S.; Iglič, A. Quadrupolar ordering of phospholipid molecules in narrow necks of phospholipid vesicles. Journal of statistical physics 2006, 125, 727–752. [CrossRef]

- Saha, T.; Heuer, A.; Galic, M. Systematic analysis of curvature-dependent lipid dynamics in a stochastic 3D membrane model. Soft Matter 2023, 19, 1330–1341. [CrossRef]

- Kralj-Iglič, V.; Pocsfalvi, G.; Mesarec, L.; Šuštar, V.; Hägerstrand, H.; Iglič, A. Minimizing isotropic and deviatoric membrane energy–An unifying formation mechanism of different cellular membrane nanovesicle types. PloS one 2020, 15, e0244796. [CrossRef]

- Raval, J.; Iglič, A.; Góźdź, W. Investigation of Shape Transformations of Vesicles, Induced by Their Adhesion to Flat Substrates Characterized by Different Adhesion Strength. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22. [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.Q.; Chen, P.C.; Góźdź, W.T.; Li, B. Mechanical adaptions of collective cells nearby free tissue boundaries. Journal of Biomechanics 2020, 104, 109763. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).