1. Introduction

Vitamin D plays an essential role in regulating the metabolism of calcium and phosphate. It promotes intestinal calcium absorption and skeletal mineralization, ensures bone growth, and contributes to bone remodeling [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Thus, a correct vitamin D status has a crucial role for preventing metabolic skeletal diseases such as osteomalacia and osteoporosis, and it helps preventing hypocalcemic tetany.

The primary target organ of vitamin D is the intestine, where, through the mediation of calcium-binding protein, it enhances the intestinal absorption of calcium. Moreover, vitamin D is involved in inflammatory processes, cellular growth, and the modulation of immune function [

5]. In fact, many tissues are also characterized by the presence of vitamin D receptors [

6,

7].

There are two sources that ensure physiological levels of vitamin D in the blood: sunlight exposure (promoting the production of vitamin D by the skin) and dietary intake. It is believed that cutaneous synthesis accounts for at least 80% of the requirement, while the remaining 20% is obtained through dietary intake [

8,

9,

10]. Cutaneous synthesis involves the production of pre-vitamin D3 from dehydrocholesterol; subsequently, through a temperature-dependent rearrangement of the triene structure, vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol), lumisterol, and tachysterol were synthesized [

7,

8]. Cutaneous synthesis of vitamin D3 is influenced by various factors including sunlight and UVB exposure (with a maximal effective wavelength between 290 and 310 nanometers), skin pigmentation, intensity and duration of sun exposure, and skin aging. Prolonged sun exposure does not lead to toxic levels of D3 because of the photo-conversion mechanism of pre-vitamin D3 into biologically inactive metabolites lumisterol and tachysterol. As known, sun exposure stimulates the production of melanin, representing an additional mechanism to limit excessive cholecalciferol synthesis [

10,

11]. Regarding dietary vitamin D intake, vitamin D is present in foods as both D2 (ergocalciferol) and D3 (cholecalciferol). Both forms are absorbed in the small intestine through a mechanism of passive diffusion and active transport proteins across the intestinal membrane [

12]. In general, vitamin D is found in limited amounts in foods. The main sources of vitamin D include fish such as trout, salmon, and tuna, which have the highest natural amount of vitamin D3, likely derived from the high content of vitamin D3 in planktonic micro algae at the base of the food chain [

13,

14,

15]. On the other hand, beef liver, chicken, pork, egg yolks, milk, and cheese contain small amounts of vitamin D, primarily as cholecalciferol and its metabolite 25OHD3. Foods like fruits, vegetables, rice, and pasta do not contain vitamin D [

16].

The condition of vitamin D deficiency undoubtedly represents a significant public health problem [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Numerous studies reported that vitamin D deficiency is widespread in pregnant women, obese individuals, and subjects who, for various reasons, cannot regularly expose themselves to sunlight [

24,

25,

26]. In particular, in the United States, where milk and cereals are fortified with vitamin D, the presence of vitamin D deficiency in the pediatric population is attributed to reduced milk intake; albeit the use of protective creams during sun exposure, and the increasing prevalence of obesity may also concur [

27]. In Italy food items are not mandatory fortified with vitamin D and thus the problem of vitamin D deficiency is still of major relevance, particularly in the winter season when due to the latitude, sunlight exposure does not allow to synthetize adequate amount of vitamin D.

Indeed, a high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency has also been documented in Europe [

28,

29,

30], not only in the elderly population but also in the age group between 50 and 70 years, both in males and females [

31]. A study conducted in nine European countries revealed that approximately 79.6% of women had 25OHD levels below 80 nmol/l, and 32.1% had levels below 50 nmol/l [

32]. Furthermore, another study conducted in 11 European countries demonstrated that 25OHD levels were lower in winter, with values below 30 nmol/l in at least 50% of the population [

33]. To date, data regarding vitamin D intake in the Italian population are very limited and poorly applicable to subjects at high risk of vitamin D deficiency, such as aging individuals or those with chronic debilitating disorders. Estimates on the prevalence of severe deficiency, deficiency, and insufficiency of vitamin D in Italy were also indirectly achieved by means of multiple-choice questions concerning the factors affecting the production, intake, absorption, and metabolism of vitamin D [

34]. On the other hand, developing a food questionnaire for the quantitative assessment of vitamin D-containing foods is not straightforward and requires a correct approach in choosing the investigative methodology.

Recently, we validated a Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) specifically designed to assess dietary vitamin D intake in the Italian population. In the same study, conducted with a small group of healthy subjects residing in central Italy, we also observed that, in both genders, the current dietary intake of vitamin D in our Country was significantly below the recommended daily allowance (RDA) [

35]. With these premises and in order to expand these preliminary data, we used our validated FFQ to conduct a survey on a large, representative cohort of the Italian population.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was carried out using the 14 days-FFQ data collection form recently validated and published [

35]. The FFQ included questions about the following items: personal data of subjects such as age (subdivided in decades from 40 to 80 years), sex, educational degree, occupation, region of origin, specific eating habits like vegetarian or vegan, presence of osteoporosis, cardiovascular, respiratory, kidney, gastrointestinal, endocrine, neurological and neoplastic diseases. In particular, the FFQ contained 11 different questions regarding the type and quantity of foods containing vitamin D consumed in the 14 days preceding the interview. The following foods were included in FFQ: milk (whole, reduced fat, nonfat, added with vitamin D); corn flakes added with vitamin D; yogurt (whole, reduced fat, nonfat, added with vitamin D); cheese (camembert, fontina, gruyere, mozzarella, parmesan, provolone, ricotta, pecorino); meat (beef, chicken, pork, turkey, fowl, lamb); fish, as bluefish, dogfish, flounder, hake, mackerel, pollock, salmon, salted cod, sardine, sea-bass, sea-bream, stock-fish, swordfish, trout, tuna (differentiated when necessary into fresh, frozen, dry heat, canned); egg (whole, yolk; raw, cooked); food with egg (flan, fried, omelet, mayonnaise, meatballs, pasta); cured meat (baked ham, raw ham, bresaola, mortadella, salami); desserts containing egg, milk, or yogurt (cake, ice cream, pastry, biscuits); and mushrooms. The FFQ also provided the possibility to indicate a specific food item not included in the list of foods described above in the FFQ. Concerning the frequency of food intake, the question inquired how many times that food was consumed in 14 days, from 1 to 14 times. If the daily dose of a particular food was more than the maximum value reported in the questionnaire, it was indicated to spread the amount over more than one day.

Subjects included in the present survey were community dwelling individuals recruited by Clinical Centers of GISMO (Italian Group for the Study of Bone Diseases) and GIBIS (Italian Group for the Study of Bisphosphonates) operating in different areas of northern, central and southern Italy.

All recruited subjects were properly informed about the study’s goal, and they signed an informed consent. The USDA National Nutrient Database and the CREA database (“

Consiglio per la Ricerca in agricoltura e l’analisi dell’Economia Agraria”) were utilized to calculate the vitamin D amount for each food [

36,

37]: data coming from foods fortified with vitamin D were excluded. The only exclusion criteria were ages <40 and >80 years. The survey received approval from the Regional Ethics Committee (Regione Toscana, Sezione Area Vasta Sud Est). The study was conducted from May 2023 to December 2023.

2.1. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using Statistica 10 (Statsoft, Tulsa, OK, USA) and SPSS (SPSS, version 21.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Data were summarized as means ± standard errors (SEs), and p < 0.05 was accepted as the value of significance. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate the variation in vitamin D intake and different variables including personal data of subjects (e.g., age decade, sex, possible specific eating habits as vegetarian or vegan); presence or absence of pathological conditions. Assuming a margin of error of 5% and a confidence level of 95% the recruited sample of 870 subjects was considered representative of the Italian population.

3. Results

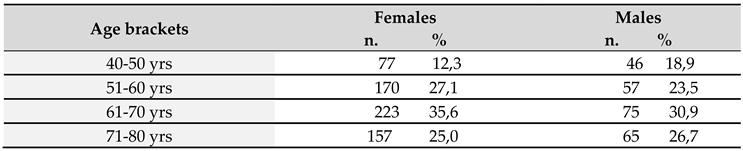

A total of 870 subjects were included, comprising 627 females and 243 males, aged 40-80 years.

Table 1 shows the population included into the study, divided into age decades; for both males and females, with the most represented decade being between 61 and 70 years. Most Italian regions were represented in the study, with the exclusion of Valle d’Aosta and Molise. The most represented were Sicily, Campania, Tuscany, and Basilicata, respectively accounting for 20.7%, 12.6%, 11.4%, and 10.6% of the total. In terms of education and employment, 39.7% of the subjects had university degree, 36% high school diploma, while 16.2% and 8.2% middle school and elementary school license, respectively; 32.5% were retired, while 24%, 13.2%, 12.8%, and 11.4%, respectively, were employees, freelancers, artisans, and housewives.

Overall, 31.6% of the studied population was apparently in good health without the presence of ongoing pathologies, while 68.4% were affected by different disorders, of which osteoporosis and cardiovascular diseases were the most represented (50,1% and 41,3%, respectively). Only 3.4% of the population included in the present survey reported specific dietary habits, of which 3.0% and 0.4% followed vegetarian and vegan habits, respectively.

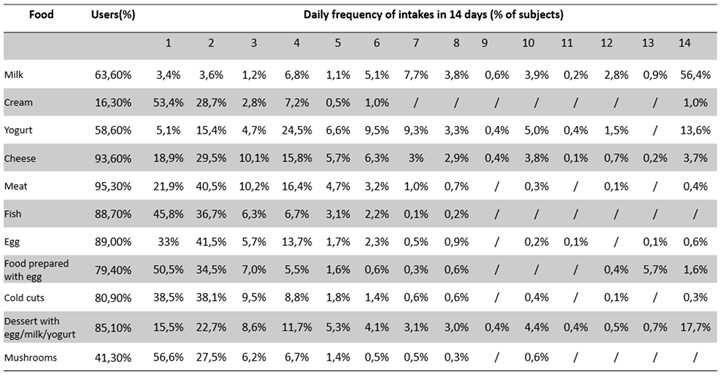

In

Table 2 are reported the percentages of user subjects for each food category along with the number of days of intake per 14 days. Milk was among the commonly consumed foods for a longer number of days (56% of cases reported a regular daily intake for all the 14 days), conversely fish, albeit consumed by a large proportion of subjects was among the less consumed foods per 14 days (1-2 days every 14 days for up to 82.5% of cases).

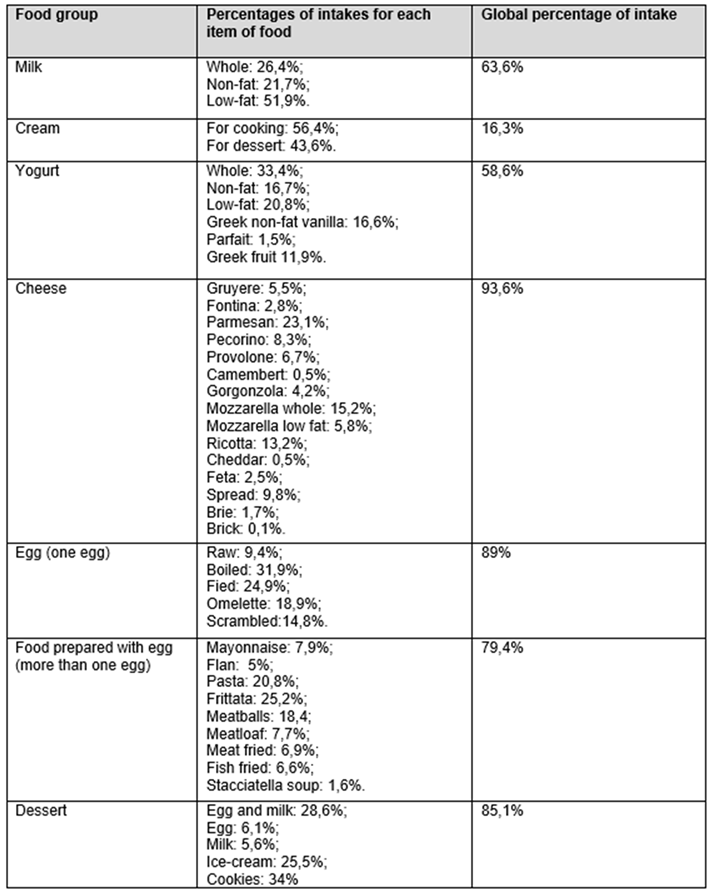

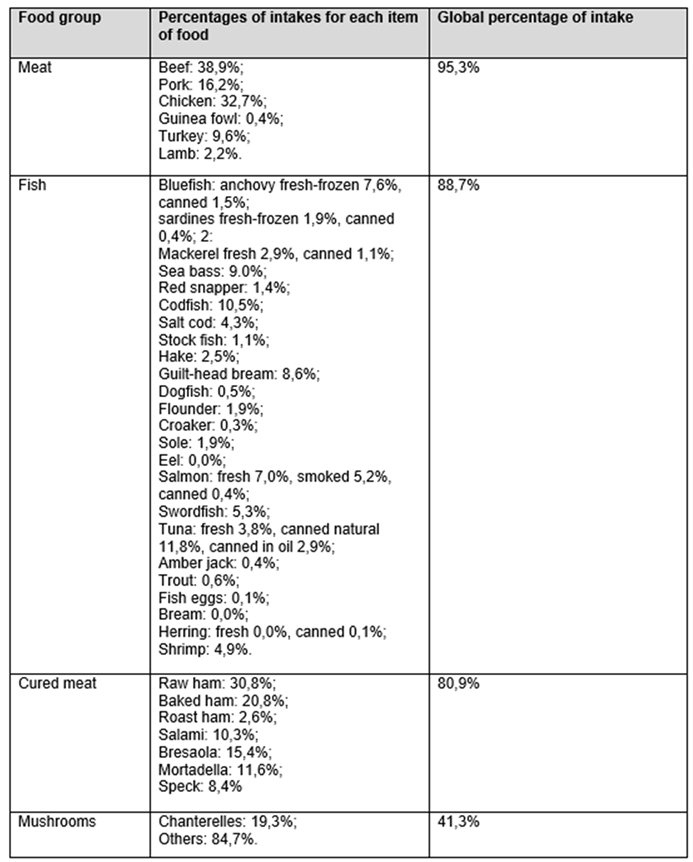

Each food category was subsequently divided according to its specific food characteristics, as shown in

Table 3A and 3B.

As regards milk, the table indicates that partially skimmed milk was consumed to a higher percentage (51.9%), followed by whole milk (26.4%); for yogurt, whole yogurt was consumed to a higher percentage (33.4%), followed by partially skimmed yogurt (20.8%); for cheese, parmesan was consumed to a higher percentage (23.1%), followed by mozzarella with whole milk (15.2%) and ricotta (13.2%); for meat, chicken was the most consumed (32.7%), followed by beef (17.9%) and pork (16.2%); for fish, canned natural tuna (11.8%), cod (10.5%), and oil-canned fish (7.4%) were that most commonly used.

By correlating the amount of each food consumed over the 14-days period with its vitamin D content per 100 mg, it was possible to calculate the amount of vitamin D ingested through foods in 2 weeks. The global amount of vitamin D intakes in 14 days were 70.8 μg

+ 1.8 (SE) [2832 IU

+ 87 (SE)] in females and 87.5 μg

+ 1.9 (SE) [3502 IU

+ 146 (SE)] in males, with a statistically significant difference between sexes (p<0.001). These data corresponded to a daily intake of 5.05 μg

+ 0.5 (SE) [202 IU

+ 6.2 (SE)] and 6.25 μg

+ 0.25 (SE) [250 IU

+ 10.4 (SE)] for females and males, respectively.

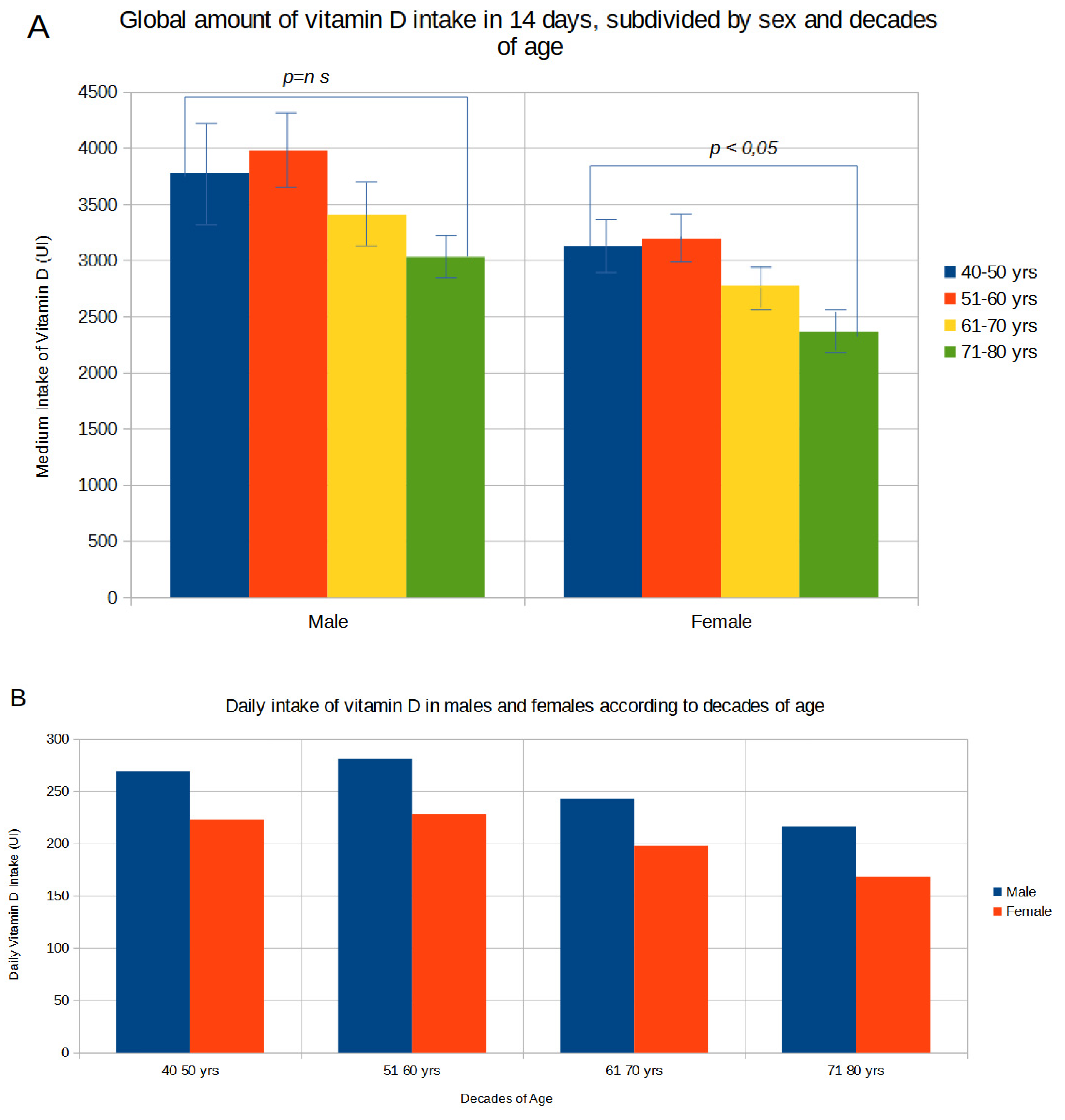

Figure 1A shows the amount of global vitamin D intakes in 14 days subdivided for sex and decades of ages. With increasing age, there was a gradual and statistically significant (p<0.01) decrease in dietary vitamin D intake in females from values of 78.2 μg

+ 5.6 (SE) [3128 IU

+ 224 (SE)] in the 40-49 age group to 59.1 μg

+ 4.1 (SE) [2362 IU

+ 162 (SE)] in the 71-80 age group; in males vitamin D intake decreased from values of 94.3μg

+ 10.7 (SE) [3774 IU

+ 428 (SE)] in the 40-49 age group to 75.7 μg

+ 4.7 (SE) [3029 IU

+ 187 (SE)] in the 71-80 age group. The mean daily amount of vitamin D subdivided by sex and decades of age is reported in

Figure 1B. In both sexes the daily vitamin D intake was very low, ranging from 6.7 μg

+ 0.7 (SE) [269 IU

+ 30 (SE)] in the 40-49 age group to 5.4 μg

+ 0.3 (SE) [216 IU

+ 13 (SE)] in the 71-80 age group in males, and from 5.6 μg

+ 0.4 (SE) [223 IU

+16 (SE)] in the 40-49 age group to 4.2 μg

+ 0.3 (SE) [168 IU

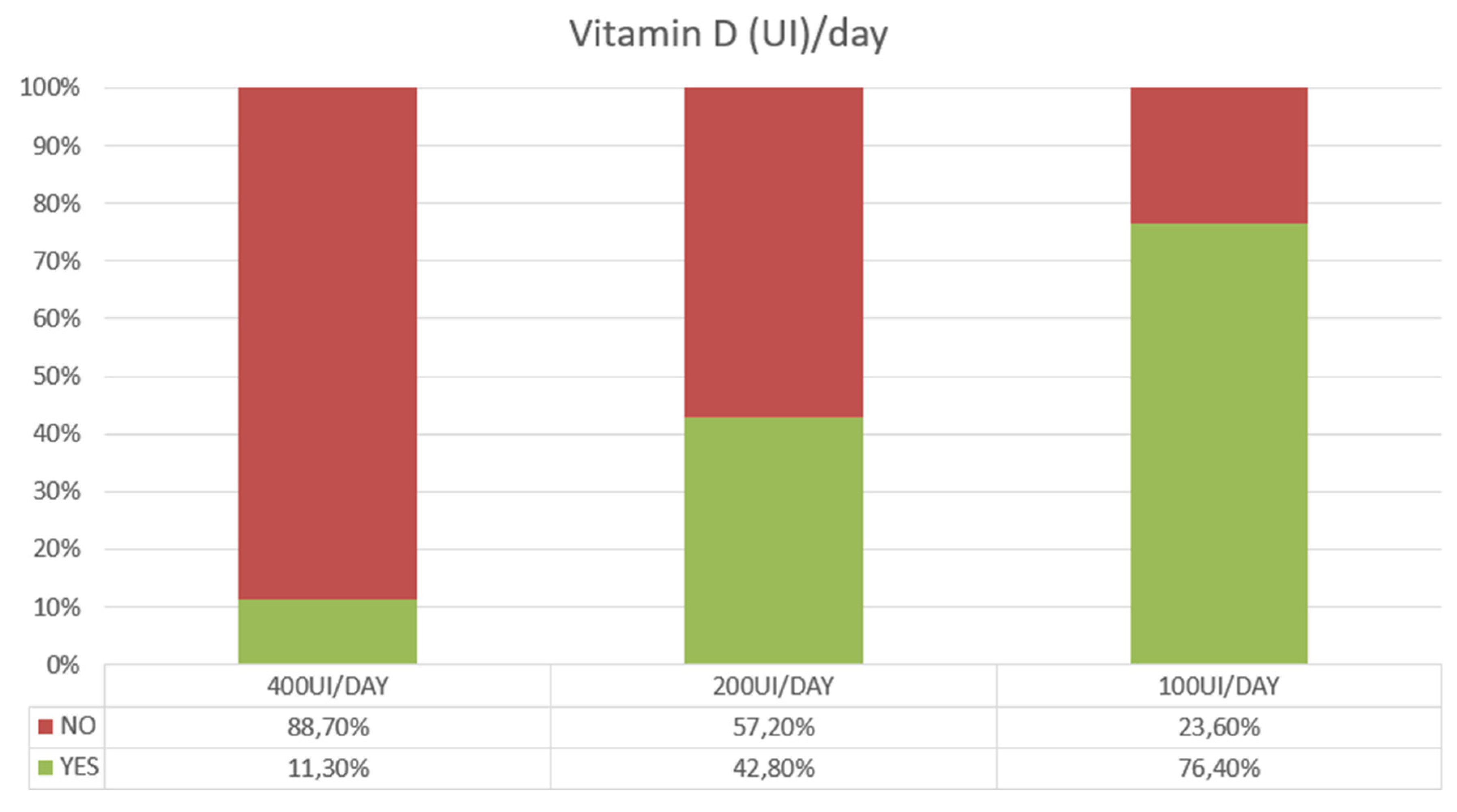

+ 11 (SE)] in the 71-80 age group in females. Based on these estimates 76,4% of subjects showed a low vitamin D intake of 100 UI/day or below, with only 11,3% reaching a daily intake of 400 UI/day or above (

Figure 2). This latter estimate dropped to 6,8% in subjects over 70 years of age.

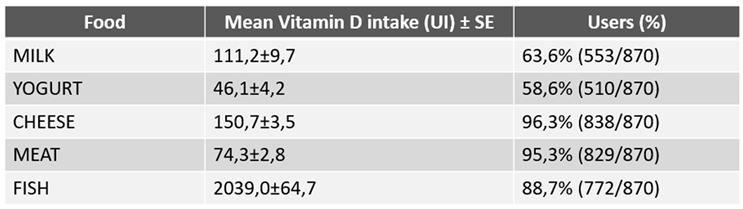

As shown in

Table 4, the greatest contribution of vitamin D intake during the 14 days of the survey was supplied by fish, resulting remarkably higher than that provided by milk, yogurt, cheese and meat, all together. The overall daily amount of vitamin D intake was lower in the 595 subjects with one or more comorbidity than in the 275 individuals apparently in good health (85.5 μg

+ 1.9 SE [3419 IU

+ 77.8 SE], and 70.8 μg

+ 1.8 SE [2832IU

+ 73.5 SE], respectively, p<0.001). The lowest intake of vitamin D occurred in patients with osteoporosis (66.6 μg

+ 1.7 SE, 2666 IU

+ 71 SE) or with oncological disorders (66.3 μg

+ 1.7 SE, 2653 IU

+ 71 SE). Moreover, as shown in

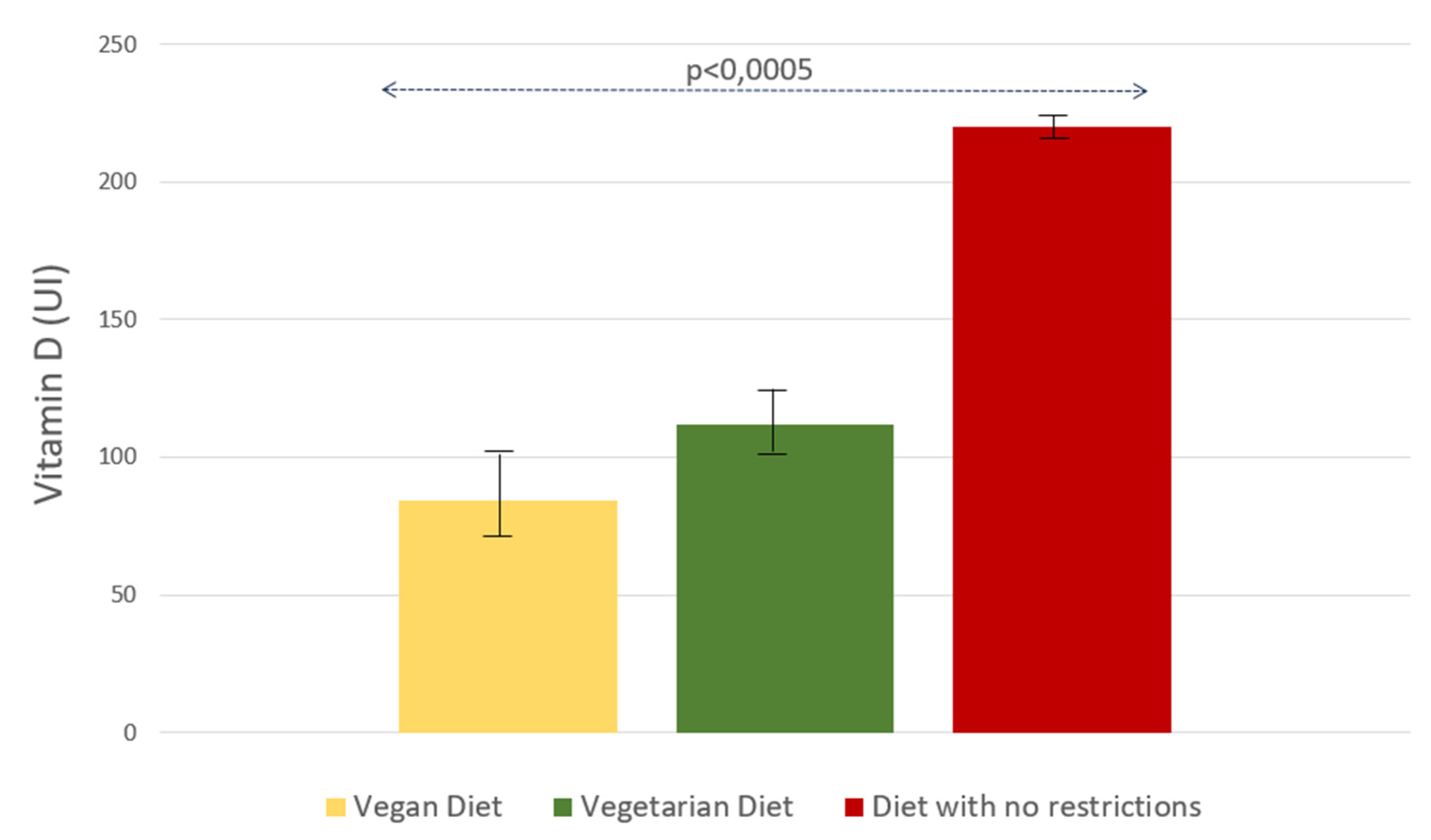

Figure 3, the mean dietary vitamin D intake was lower in vegan and vegetarian subjects than in patients without any particular dietary regimen (2.1 μg

+ 0.7 SE [84 IU

+ 31 SE] vs. 2.8 μg

+ 0.6 [112 IU

+ 23 SE] vs. 5.5 μg

+ 0,1 [220 IU

+ 5 SE, p<0.0005] respectively).

4. Discussion

The present study confirms our preliminary observation obtained from a limited number of subjects [

35] showing that in the Italian population the amount of vitamin D intake from foods is limited, with mean daily intakes in females and males of 5.1 μg [202 IU] and 6.2 μg [250 IU], respectively. These data clearly indicate that the average daily vitamin D intake in Italy is very far from the recommended values of 15 μg (600 UI) and 20 μg (800 UI) for subjects aged 51-70 years or above 70 years [

17,

38], respectively, and suggest that, at least in the winter season, sunlight exposure might not allow to achieve an adequate vitamin D status in a consistent portion of individuals. Such a low intake was a prerogative of both genders and decreased significantly (p<0.001) with aging in females. Fish was undoubtedly the most important source of vitamin D, despite during the period of 14 days it was consumed on average only 1-2 times per week.

Importantly, vitamin D intakes were reduced in subjects following vegetarian or vegan eating habits. Moreover, a statistically significant difference was found between healthy group and patients with pathological conditions, with low values of vitamin D intake in patients with osteoporosis and oncological disorders. Generally, vitamin D status is mainly ensured by adequate sunlight exposure, even if it is not always possible due to various factors as latitude, skin photo-type, regular outdoor physical activity, and habitual use of sunscreens. In Italy an adequate sunlight exposure cannot always be guaranteed, especially during the winter season, mainly due to the latitude [

39]. Moreover, darker skin subjects require a larger UV dose for the same change in 25OHD, and small, regular UV doses seem to be more efficient for vitamin D synthesis than larger sub-erythemal doses [

40].

While low dietary intake of vitamin D may seemingly play a marginal role in the development of vitamin D status in particular geographical areas, otherwise it plays a determining role in conditions where cutaneous synthesis of vitamin D is compromised or reduced, explaining consequently the widespread prevalence of hypovitaminosis D. In example, in Morocco, characterized by a dry-summer subtropical climate and theoretically optimal sunlight exposure, a high prevalence of hypovitaminosis (vitamin D levels <30 ng/mL) was described, affecting 90% of the general female population (41). This was supposed to arise as the consequence of moderate sunlight exposure (41,4% of study participants), but also of a low dietary intake, since 90.78% and 84.21% of participants had vitamin D intakes below the recommended diet allowance (RDA) [

41]. This is consistent with our results, and further highlights the difficulty of achieving adequate vitamin D status through diet and sun exposure in particular geographic areas and in certain categories of subjects.

Indeed, hypovitaminosis D is recognized as a global health problem [

17]. In this regard limited consumption of foods containing relevant quantities of vitamin D or fortified foods, scarce use of vitamin D supplements, lactose intolerance, and socioeconomic status must be considered. In Italy hypovitaminosis D is common, as confirmed by studies in the general population and patients with metabolic bone disorders [

42,

43,

44,

45]. The clinical consequences of vitamin D deficiency may involve bone and muscle health, with increased risks of secondary hyperparathyroidism, fragility fractures, osteomalacia, and an enhanced risk of falls, especially in elderly subjects [

46,

47,

48]. Moreover, potential extra-skeletal actions [

49,

50] suggest vitamin D’s roles in immunity, cancer, cardiovascular health, obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome, albeit controlled studies and metanalyses often yielded unclear and conflicting results [

47,

51,

52,

53,

54]. The present study is the first extensive survey performed in Italy on adult subjects that underscores the role of insufficient dietary vitamin D intake as a likely explanation for the high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency.

However our survey retains some limitations, mainly concerning representativeness of the study at the population level, the cross-sectional design, the use of FFQ instead of 24-h recall to achieve data about food intake, the use of different sources of food composition data even if much of the information was derived by the USDA National Nutrient Database, and the lack of information about vitamin D status of subjects included in the study.

Overall, our data align with similar observations collected in different countries where total vitamin D intake varied from 3 µg (120 IU) to 5.9 µg (236 IU) per day [

55,

56], being significantly lower than the RDA suggested by the USA Institute of Medicine [

57]. In the US population (2011–2014 and trends from 2003 to 2014), the mean intake of vitamin D from food and beverage sources was 3.5 μg (140 IU) [

58], and Canadian Health Measures Survey reports mean intakes of vitamin D of 5.1 (204 IU) and 4.2 (168 IU) µg/day for males and females, respectively [

59]; in both estimates, the contribution from foods fortified with vitamin D or dietary supplements containing vitamin D were not considered. Low dietary intakes, with mean values of 3.1 (124 IU) and 2.5 µg/d (100 IU) in adult men and women, respectively, were observed also by the UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey [

60]. In Sweden, by a web-based dietary record to assess dietary intake, most participants reported a vitamin D intake below the average requirement (AR), and only 16 % of children and 33 % of adults met the AR (7,5 μg, corresponding to 300 IU) [

29]. In European countries, mean vitamin D intakes well above 5 µg/day (200 IU) were reported mainly in Northern Europe, likely related to the use of fortified foods, while in the other European countries, especially in the Mediterranean area, the intake is often below 4 µg/day (160 IU) [

61]. This report included data from the Italian population obtained from The third Italian national food consumption survey (INRAN-SCAI 2005-2006), even though the study used a generalized 3-day food consumption record and was not specifically designed to assess dietary vitamin D intake [

62]. In that study the mean amounts of vitamin D intake from foods were even lower than observed in our study and varied between 1,8 and 2,6 µg/d in relation to age and gender. Such a lower intake might have clinical consequences, irrespective of the potential contribution of sunlight exposure on vitamin D status, as observed in two separate studies performed in populations from the Mediterranean area, showing an implication of reduced dietary vitamin D intake on cognitive impairment and cardiovascular disease [

48,

63].

The opportunity for fortification strategies is suggested in most countries as a public health policy to meet dietary vitamin D recommendations [

64], while vitamin D supplements are generally indicated as the recommended alternative when dietary intake is insufficient, in cases of reduced or insufficient UVB radiation, with recommendations for daily intake to be increased to at least 10 μg per day and 25 μg in the elderly (400 IU and 1000 IU, respectively) [

65]. Recently, the ESCEO (European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases) working group recommended 25 μg daily (1000 IU) in patients at increased risk of vitamin D deficiency [

66]. The Italian population predominantly follows a dietary regimen known as the “Mediterranean diet,” a nutritional model inspired by the traditional eating habits of countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea. Studies conducted since the 1950s have consistently emphasized its positive impact on health when combined with a healthy lifestyle. The predominant consumption of plant-based foods such as grains and derivatives, legumes, fruits, vegetables, and extra virgin olive oil has been shown to positively alter the impact of atherosclerotic diseases compared to diets high in red meats and saturated fats. However, it is evident that this dietary pattern often lacks foods with a high content of vitamin D, such as fish, milk, cheese, and eggs. In this perspective, the establishment of an educational health policy aimed at promoting a vitamin D-rich diet from early childhood to adulthood is believed to be extremely beneficial [

67]. The study suggests the implementation of educational healthcare policies, starting from childhood and continuing into adulthood, to promote a correct dietary approach rich in vitamin D [

67]. When dietary changes are not feasible, fortification of certain foods (such as milk and cheese) with vitamin D is advisable [

68,

69,

70]. In cases where these measures are insufficient, vitamin D supplementation, especially in at-risk groups like children, pregnant women, and the elderly, remains a crucial strategy to reduce the risk of hypovitaminosis D and its clinical consequences [

71,

72].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.N. and L.T.; Methodology, R.N. and L.T.; Software, L.T.; Validation, R.N.; Data curation, L.G, G.C., A.C, C.M.F, C.L., G.L.M., N.M, M.M., G.M., R.R., P.S., M.P., S.S., A.X. and F.V; Writing—original draft, R.N.; Writing—review & editing, L.G. and D.M.; Visualization, C.C., B.F. and S.G.; Supervision, L.G. and D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Regione Toscana, Sezione Area Vasta Sud Est (protocol code 21684, date of approval 21 February 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

Questionnaires have been collected also with the support of following Doctors to whom our thanks go: Ferdinado Silveri (ASUR, Ancona, Italy), Vincenzo Vinicola (IRCCS Fondazione Santa Lucia, Roma, Italy), Carmen Aresta (Auxologico San Luca, Milano, Italy), Giorgio Gandolini (Fondazione Don Gnocchi, Milano), Paola Parlatore (ASL Roma 5, Roma, Italy), Alberto Falchetti (Ospedale Niguarda, Milano), Carlo Cisari (Università del Piemonte Orientale, Novara), Maurizio Dorato (P.O. S. Maria delle Grazie, Pozzuoli, Napoli), Eleonora Lalli (Gragnano, Napoli, Italy), Alessandra Randazzo (Ospedale del Mare, Napoli, Italy), Serenella Checchi (Bagno a Ripoli, Firenze, Italy), Stefania Falcone, Università Tor Vergata, Roma, Italy), Lara Ricciardelli (Pesaro), Alessandra Canavese (ASL2, Savona, Italy), Antonio Colicchia (Varese, Italy), Lucia Cosenza (Novare, Italy), Giulia Danti (Bolzano, Italy), Lucia Marcantonio (Casale Monferrato, Italy), Emilio Martini (AOU Modena, Modena, Italy), Gabriella Radaelli (IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano, Milano, Italy), Elena Segato (Milano, Italy), Tiziana Zbant (Brescia), Santo Colosimo (Ferrara, Italy), Francesco Tripodi (Salerno, Italy), Maria Pia Carelli (L’Aquila, Italy), Alberto Marchetti (Milano), Francesco Del Forno (Bologna), Irene Abbiate (Torino), Manuel Perotti (Piacenza), Roberta Cosso (IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano, Piancavallo, VB), Cinzia Marinaro (Università di Catanzaro, Catanzaro, Italy), Gabriella Bertoletti (Cosenza, Italy).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bikle, D.D.; Adams, J.S.; Christakos, S. Vitamin D: Production, Metabolism, Action, and Clinical Requirements. In Primer on the Metabolic Bone Diseases and Disorders of Mineral Metabolism, 9th ed.; Bilezikian John, P., Ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Y.; Fleet, J.C. Intestinal vitamin D receptor is required for normal calcium and bone metabolism in mice. Gastroenterology 2009, 136, 1317–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panda, D.K.; Miao, D.; Bolivar, I.; Li, J.; Huo, R.; Hendy, G.N.; Goltzman, D. Inactivation of the 25-hydroxyvitamin D 1alpha-hydroxylase and vitamin D receptor demonstrates independent and interdependent effects of calcium and vitamin D on skeletal and mineral homeostasis. J Biol Chem 2004, 279, 16754–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raisz, L.G.; Trummel, C.L.; Holick, M.F.; DeLuca, H.F. 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol: a potent stimulator of bone resorption in tissue culture. Science 1972, 175, 768–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pludowski, P.; Holick, M.F.; Pilz, S.; Wagner, C.L.; Hollis, B.W.; Grant, W.B.; Shoenfeld, Y.; Lerchbaum, E.; Llewellyn, D.J.; Kienreich, K.; Soni, M. Vitamin D effects on musculoskeletal health, immunity, cardiovascular disease, cancer, fertility, pregnancy, dementia and mortality – a review of recent evidence. Autoimmun Rev 2013, 12, 976–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, J.; DeLuca, H.F. Where is the vitamin D receptor? Arch Biochem Biophys 2012, 523, 123–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlberg, C. Vitamin D and Its Target Genes. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F.; McLaughlin, J.A.; Clark, M.B.; Holick, S.A.; Potts, J.T. Jr; Anderson, R.R.; Blank, I.H.; Parrish, J.A.; Elias, P. Photosynthesis of previtamin D3 in human skin and the physiologic consequences. Science 1980, 210, 203–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.S.; Clemens, T.L.; Parrish, J.A.; Holick, M.F. Vitamin D synthesis and metabolism after ultraviolet irradiation of normal and vitamin D deficient subjects. N Engl J Med 1982, 306, 722–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, A.R.; Kline, L.; Holick, M.F. Influence of season and latitude on the cutaneous synthesis of vitamin D3: exposure to winter sunlight in Boston and Edmonton will not promote vitamin D3 synthesis in human skin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1988, 67, 373–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mithal, A.; Wahl, D.A.; Bonjour, J.P. Global vitamin D status and determinants of hypovitaminosis D. Osteoporos Int 2009, 20, 1807–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.C.; Furlanetto, T.W. Intestinal absorption of vitamin D: A systematic review. Nutr Rev 2018, 76, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine, Food and Nutrition Board. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2010.

- Norman, A.W.; Henry, H.H. Vitamin D. In: Erdman JW, Macdonald IA, Zeisel SH, eds. Present Knowledge in Nutrition, 10th ed. Washington DC: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

- Jones, G. Vitamin D. In: Ross AC, Caballero B, Cousins RJ, Tucker KL, Ziegler TR, eds. Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease, 11th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams &Wilkins, 2014.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Food labeling: Revision of the Nutrition and Supplement Facts labels (https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/05/27/2016- 11867/food-labeling-revision-of-the-nutrition-and-supplementfacts- labels). Federal Register 2016, 81, 33742–33999. [Google Scholar]

- Holick, M.F. The vitamin D deficiency pandemic: Approaches for diagnosis treatment and prevention. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2017, 18, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Geriatrics Society Workgroup on Vitamin D Supplementation for Older Adults. Recommendations abstracted from the American Geriatrics Society Consensus Statement on vitamin D for Prevention of Falls and Their Consequences. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014, 62, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, P.R.; Thacher, T.D.; Pettifor, J.M. Pediatric vitamin D and calcium nutrition in developing countries. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2008, 9, 181–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Schoor, N.M.; Lips, P. Worldwide vitamin D status. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011, 25, 671–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Naughton, D.P. Vitamin D in health and disease: current perspectives. Nutr J 2010, 9, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Gross, M.; Valtueña, J.; Breidenassel, C.; et al. Vitamin D status among adolescents in Europe: the healthy lifestyle in Europe by nutrition in adolescence study. Br J Nutr 2012, 107, 755–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, R.M.; Gagnon, C.; Lu, Z.X.; Magliano, D.J.; Dunstan, D.W.; Sikaris, K.A.; Zimmet, P.Z.; Ebeling, P.R.; Shaw, J.E. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and its determinants in Australian adults aged 25 years and older: a national, population-based study. Clin Endocrinol 2012, 77, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F.; Binkley, N.C.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Gordon, C.M.; Hanley, D.A.; Heaney, R.P.; Murad, M.H.; Weaver, C.M. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011, 96, 1911–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossein-nezhad, A.; Holick, M.F. Vitamin D for health: a global perspective. Mayo Clin Proc 2013, 88, 720–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nesby-O’Dell, S.; Scanlon, K.S.; Cogswell, M.E.; Gillespie, C.; Hollis, B.W.; Looker, A.C. Hypovitaminosis D prevalence and determinant among African American and white women of reproductive age: third national health and nutrition examination survey, 1988-1994. Am J Clin Nutr 2002, 76, 187–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Looker, A.C.; Johnson, C.L.; Lachner, D.A.; Pfeiffer, C.M.; Schleicher, R.L.; Sempos, C.T. Vitamin D status: United States, 2001-2006. NCHS Data Brief 2011, 56. [Google Scholar]

- van Schoor, N.M.; Lips, P. Worldwide vitamin D status. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011, 25, 671–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nälsén, C.; Becker, W.; Pearson, M.; Ridefelt, P.; Lindroos, A.K.; Kotova, N.; Mattisson, I. Vitamin D status in children and adults in Sweden: dietary intake and 25- hydroxyvitamin D concentrations in children aged 10-12 years and adults aged 18-80 years. J Nutr Sci 2020, 9, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahrni, O.; Wilhelm-Bals, A.; Posfay-Barbe, K.M; Wagner, N. Hypovitaminosis D in migrant children in Switzerland: a retrospective study. Eur J Pediatr 2021, 180, 2637–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzoli, R.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.; Dawson-Hughes, B.; Weaver, C. Nutrition and bone health in women after the menopause. Womens Health 2014, 10, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruyere, O.; Malaise, O.; Neuprez, A. , Collette, J.; Reginster, J.Y. Prevalence of vitamin D inadequacy in European postmenopausal women. Curr Med Res Opin 2007, 23, 1939–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J.; Biolo, G.; Cederholm, T.; Cesari, M.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Morley, J.E.; Phillips, S.; Sieber, C.; Stehle, P.; Teta, D.; Visvanathan, R.; Volpi, E.; Boirie, Y. Evidence-based recommendations for optimal dietary protein intake in older people: a position paper from the PROT-AGE Study Group. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2013, 14, 542–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giuseppe, R.; Tomasinelli, C.E.; Cena, H.; Braschi, V.; Giampieri, F.; Preatoni, G.; Centofanti, D.; Princis, M.P.; Bartoletti, E.; Biino, G. Development of a Short Questionnaire for the Screening for Vitamin D Deficiency in Italian Adults: The EVIDENCe-Q Project. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuti, R.; Gennari, L.; Cavati, G.; Pirrotta, F.; Gonnelli, S.; Caffarelli, C.; Tei, L.; Merlotti, D. Dietary Vitamin D Intake in Italian Subjects: Validation of a Frequency Food Questionnaire (FFQ). Nutrients 2023, 15, 2969–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA’s) FoodData Central Lists the Nutrient Content of Many Foods and Provides Comprehensive List of Foods Containing Vitamin D Arranged by Nutrient Content. Available online: https://ods.od.nih.gov/pubs/usdandb/VitaminD-Content.pdf (accessed on 27 June 2023).

- CREA. Available online: https://www.crea.gov.it/web/alimenti-e-nutrizione/banche-dati (accessed on 27 June 2023).

- IOM Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 2011.

- Wacker, M.; Holick, M.F. Sunlight and Vitamin D: A global perspective for health. Derm.-Endocrinol. 2013, 5, 51–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, A.R.; Alghamdi, R.; Kift, R.; Rhodes, L.E. Dose–response for change in 25-hydroxyvitamin D after UV exposure: outcome of a systematic review. Endocrine Connections 2021, 10, R248–R266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouine, N.; Lhilali, I.; Menouni, A.; Godderis, L.; El Midaoui, A.; El Jaafari, S.; Zegzouti Filali, Y. Development and Validation of Vitamin D- Food Frequency Questionnaire for MoroccanWomen of Reproductive Age: Use of the Sun Exposure Score and the Method of Triad’s Model. Nutrients 2023, 15, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaia, G.; Giorgino, R.; Rini, G.B.; Bevilacqua, M.; Maugeri, D.; Adami, S. Prevalence of hypovitaminosis D in elderly women in Italy: clinical consequences and risk factors. Osteoporos Int 2003, 14, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuti, R.; Martini, G.; Valenti, R.; Gambera, D.; Gennari, L.; Salvadori, S.; Avanzati, A. Vitamin D status and bone turnover in women with acute hip fracture. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004, 422, 208–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagnoli, E.; Caravella, P.; Scarnecchia, L.; Martinez, P.; Minisola, S. Hypovitaminosis D in an Italian population oh healthy subjects and hospitalized patients. Br J Nutr 1999, 81, 133–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendina, D.; De Filippo, G.; Merlotti, D.; Di Stefano, M.; Succoio, M.; Muggianu, S.M.; Bianciardi, S.; D’Elia, L.; Coppo, E.; Faraonio, R.; et al. Vitamin D Status in Paget Disease of Bone Efficacy-Safety Profile of Cholecalciferol Treatment in Pagetic Patients with Hypovitaminosis D. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2019, 10, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M. Vitamin D Deficiency. N Engl J Med 2007, 357, 266–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouillon, R.; Marcocci, C.; Carmeliet, G.; Bikle, D.; White, J.H.; Dawson-Hughes, B.; Lips, P.; Munns, C.F.; Lazaretti-Castro, M.; Giustina, A.; Bilezikian, J. Skeletal and extraskeletal actions of vitamin D: current evidence and outstanding questions. Endocr Rev 2019, 40, 1109–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, W.; Hu, P.; Zhang, R.; Dong, X.; Zhang, D. Association of Dietary Vitamin D Intake, Serum 25(OH)D3, 25(OH)D2 with Cognitive Performance in the Elderly. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewison, M.; Burke, F.; Evans, K.N.; Lammas, D.A.; Sansom, D.M.; Liu, P.; Modlin, R.L.; Adams, J.S. Extra-renal 25-hydroxyvitamin D3-1a-hydroxylase in human health and disease. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2007, 103, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.T.; Tavera-Mendoza, L.E.; Laperriere, D.; Libby, E.; MacLeod, N.B.; Nagai, Y.; Bourdeau, V.; Konstorum, A.; Lallemant, B.; Zhang, R.; Mader, S.; White, J.H. Largescale in silico and microarray-based identification of direct 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 target genes. Mol Endocrinol 2005, 19, 2685–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Wang, L.; Pittas, A.G.; Del Gobbo, L.C.; Zhang, C.; Manson, J.E.; Hu, F.B. Blood 25-hydroxy vitamin D levels and incident type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 1422–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autier, P.; Boniol, M.; Pizot, C.; Mullie, P. Vitamin D status and ill health: A systematic review. Lancet Diab Endocrinol 2014, 2, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittas, A.G.; Kawahara, T.; Jorde, R.; Dawson-Hughes, B.; Vickery, E.M.; Angellotti, E.; Nelson, J.; Trikalinos, T.A.; Balk, E.M. Vitamin D and Risk for Type 2 Diabetes in People With Prediabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Individual Participant Data From 3 Randomized Clinical Trials. Ann Intern Med 2023, 176, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillon, R.; Manousaki, D.; Rosen, C.; Trajanoska, K.; Rivadeneira, F.; Richards, J.B. The health effects of vitamin D supplementation: Evidence from human studies. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2022, 18, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowson, C.A.; Margerison, C. Vitamin D intake and vitamin D status of Australians. Med J Aust 2002, 177, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, S.A.; Ashwell, M. New vitamin D values for meat and their implication for vitamin D intake in British adults. Proc Nutr Soc 1997, 56, 116A. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, C.; Murphy, M.M.; Keast, D.R.; Holick, M.F. Vitamin D intake in the United States. J Am Diet Assoc 2004, 104, 980–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrick, K.A.; Storandt, R.J.; Afful, J.; Pfeiffer, C.M.; Schleicher, R.L.; Gahche, J.J.; Potischman, N. Vitamin D status in the United States, 2011–2014. Am J Clin Nutr 2019, 110, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Ng, A.; L’Abbe, M.R. Nutrient intakes of Canadian adults: Results from the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS)-2015 public use microdata file. Am J Clin Nutr 2021, 114, 1131–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition. Report on Vitamin D and Health. 2016. Availableonline:https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/537616/SACN_Vimin_D_and_Health_report.pdf (accessed on 27 June 2023).

- Cashman, K.D. Global differences in vitamin D status and dietary intake: A review of the data. Endocr Connect 2022, 11, e210282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sette, S.; Le Donne, C.; Piccinelli, R.; Arcella, D.; Turrini, A.; Leclercq, C. The third Italian National Food Consumption Survey, INRAN-SCAI 2005–06 – Part 1: Nutrient intakes in Italy. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2011, 21, 922–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouvari, M.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Chrysohoou, C.; Yannakoulia, M.; Georgousopoulou, E.N.; Tousoulis, D.; Pitsavos, C. ATTICA study Investigators. Dietary vitamin D intake, cardiovascular disease and cardiometabolic risk factors: A sex-based analysis from the ATTICA cohort study. J Hum Nutr Diet 2020, 33, 708–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanham-New, S.A.; Wilson, L.R. Vitamin D – has the new dawn for dietary recommendations arrived? J Hum Nutr Diet 2016, 29, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamberg-Allardt, C. Vitamin D in foods and as supplements. Biophys Mol Biol 2006, 92, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalley, T.; Brandi, M.L.; Cashman, K.D.; Cavalier, E.; Harvey, N.C.; Maggi, S.; Cooper, C.; Al-Daghri, N.; Bock, O.; Bruyère, O.; Rosa, M.M.; Cortet, B.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Cherubini, A.; Dawson-Hughes, B.; Fielding, R.; Fuggle, N.; Halbout, P.; Kanis, J.A.; Kaufman, J.M.; Lamy, O.; Laslop, A.; Yerro, M.C.P.; Radermecker, R.; Thiyagarajan, J.A.; Thomas, T.; Veronese, N.; de Wit, M.; Reginster, J.Y.; Rizzoli, R. Role of vitamin D supplementation in the management of musculoskeletal diseases: Update from an European Society of Clinical and Economical Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases (ESCEO) working group. Aging Clin Exp Res 2022, 34, 2603–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillon, R. Comparative analysis of nutritional guidelines for vitamin D. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2017, 13, 466–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itkonen, S.; Erkkola, M.; Lamberg-Allardt, C. Vitamin d fortification of fluid milk products and their contribution to vitamin D intake and vitamin D status in observational Studies: a review. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaaskelainen, T.; Itkonen, S.T.; Lundqvist, A.; Erkkola, M.; Koskela, T.; Lakkala, K.; Dowling, K.G.; Hull, G.L.; Kroger, H.; Karppinen, J.; Kyllonen, E.; Harkanen, T.; Cashman, K.D.; Mannisto, S.; Lamberg-Allardt, C. The positive impact of general vitamin D food fortification policy on vitamin D status in a representative adult Finnish population: evidence from an 11-y follow-up based on standardized 25-hydroxyvitamin D data. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 105, 1512–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilz, S.; Marz, W.; Cashman, K.D.; Kiely, M.E.; Whiting, S.J.; Holick, M.F.; Grant, W.B.; Pludowski, P.; Hiligsmann, M.; Trummer, C.; Schwetz, V.; Lerchbaum, E.; Pandis, M.; Tomaschitz, A.; Grubler, M.R.; Gaksch, M.; Verheyen, N.; Hollis, B.W.; Rejnmark, L.; Karras, S.N.; Hahn, A.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Reichrath, J.; Jorde, R.; Elmadfa, I.; Vieth, R.; Scragg, R.; Calvo, M.S.; van Schoor, N.M.; Bouillon, R.; Lips, P.; Itkonen, S.T.; Martineau, A.R.; Lamberg-Allardt, C.; Zittermann, A. Rationale and plan for vitamin d food fortification: a review and guidance paper. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018, 9, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lips, P.; Cashman, K.D.; Lamberg-Allardt, C.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Obermayer-Pietsch, B.; Bianchi, M.L.; Stepan, J.; El-Hajj Fuleihan, G.; Bouillon, R. Current vitamin D status in European and Middle East countries and strategies to prevent vitamin D deficiency: a position statement of the European Calcified Tissue Society. Eur J Endocrinol 2019, 180, 23–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouillon, R.; Antonio, L. Nutritional rickets: Historic overview and plan for worldwide eradication. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2020, 198, 105563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).