1. Introduction

A solid with micropores are called porous media, and these micropores are often interconnected and usually filled with fluid. Porous media encompasses natural substances, such as biological tissues, wood, zeolites, soils, and rocks. Due to its numerous fundamental and industrial applications, double diffusive convection (DDC) in porous media is a phenomenon that occurs in a variety of systems and has attracted a lot of attention in recent decades. These applications include producing high-quality crystals, storing liquid gases, migrating moisture in fiber insulation, transporting contaminants in saturated soils, solidifying molten alloys, and heating lakes and magmas through geothermal processes. Ingham and Pop [

1], Nield and Bejan [

2], and Vafai [

3] have provided comprehensive reviews on this subject.

The stability or instability of fluid flow is a crucial aspect of fluid mechanics in porous media. Research on how buoyancy and shearing forces affect fluid flow stability in a vertical layer of porous media has received significant attention. Gill [

4] performed an initial analysis of the stability of natural convection in a vertical porous layer whose boundary is impermeable at different temperatures, using Darcy's law as a framework. He concluded that the system always maintains linear stability. Subsequently, Rees [

5] added a temporal derivative of the velocity to the momentum equation and determined that the flow remains linearly stable, which is the same as Gill's conclusion. For porous media with high porosity, Lundgren [

6] experimentally confirmed that the extension of Darcy's law by Brinkman is more valid. Shankar

et al. [

7] investigated the effect of inertial terms on the stability of natural convection in a vertical layer of a porous medium at different temperatures using the Brinkman model. Using the classical linear stability theory, they discovered that instability is caused by the inertia effect.

Viscoelastic fluids naturally exhibit convection when flowing through porous media, which has important implications for reservoir engineering, bioengineering and geophysics. Gözüm and Arpaci [

8] initially investigated the stability of natural convection in a vertical layer at various temperatures for a viscoelastic Maxwell fluid. Takashima [

9] investigated the same problem with Oldroyd-B fluid. Khuzhayorov

et al. [

10] proposed a revised Darcy's law for analyzing the viscoelastic properties of saturated porous materials. Using the homogenization method, they discovered a general filtration law that describes the flow of a linear viscoelastic fluid in a porous material. Kim

et al. [

11] used a modified Darcy model to analyze thermal instability in a horizontal porous layer with saturated Oldroyd-B fluid. The conventional linear stability theory provided the critical conditions for the initiation of convective motion. Using a modified Darcy-Brinkman-Oldroyd model, Zhang

et al. [

12] investigated the convection of saturated Oldroyd-B fluid in a horizontal porous layer heated from below. They calculated the critical number of stationary and oscillating convection. Sun

et al. [

13] studied the lower horizontal plate that was heated in a time-periodic pattern. The system changed from a steady convection to a periodic or chaotic state. Barletta and Alves [

14] investigated the Gill stability problem for power-law fluids and discovered that Gill's findings are also applicable to the power-law fluid. The Gill problem for Oldroyd-B fluid was addressed by Shankar and Shivakumara [

15]. In contrast to the results for Newtonian and power-law fluids, the flow of Oldroyd-B fluid is unstable.

Besides, they [

16] considered the situation of local thermal non-equilibrium (LTNE) and instability that existed as well. Then, Shanker and Shivakumara [

17] considered the case of a porous layer containing an internal heat source. He established that internal heating and relaxation parameters contribute to system instability. Newtonian fluids flow steady, while Oldroyd-B fluids flow unstable. For double-diffusive convection instead of thermal convection, Wang and Tan [

18] used a modified Darcy model to study the stability of Maxwell fluids in porous media with two parallel planes.

Malashetty and Biradar [

19] investigated the cross-diffusion effect on DDC. They conducted linear and weakly nonlinear stability analyses using a modified Darcy model with a time derivative term as the momentum equation and found the critical Rayleigh number. Malashetty

et al. [

20,

21] then studied the stability of the Oldroyd-B fluid and the formation of DDC saturated isotropic and anisotropic horizontal porous layers, respectively. As a result, the thermal anisotropy parameter has a dual role in the stability of the flow. Kumar and Bhadauria [

22] explored the situation of LTNE, adding a time derivative term to the momentum equation. They discovered that when the interphase heat transfer coefficient was big or small, the system behaved similarly to the local thermal equilibrium (LTE) model. Subsequently, Malashetty

et al. [

23] investigated the situation of an anisotropic rotating porous layer with LTE and found that the thermal anisotropy parameter has the opposite effect on the onset of convection compared with the no-rotation condition. The onset of DDC in a horizontal porous layer was recently studied by Swamy

et al. [

24] based on the Darcy-Brinkman-Oldroyd model.

Due to numerous applications in geothermal systems, energy storage devices, thermal insulation, drying technologies, catalytic reactors, and nuclear waste repositories, theoretical and experimental research has focused on heat and mass transmission in porous systems. Density gradients in fluid-saturated media can cause heat and mass transmission to be coupled because of heat and mass inhomogeneities when examining heat and mass transfer processes in porous media channels. The cross-diffusion effect is simultaneously brought on by mass and heat fluxes. The Soret effect transfers mass via a temperature gradient, while the Dufour effect transfers heat via a concentration gradient. The Dufour coefficient has a negligible energy flux in liquids and is an order of magnitude smaller than the Soret coefficient (see Straughan and Hutter [

25]). Therefore, while discussing liquid flow, we can ignore the Dufour term. The majority of recent research on DDC in porous layers that takes the Soret effect into account has concentrated on horizontal porous layers. With the Darcy model, Bahloul

et al. [

26] examined the beginning of natural convection in a horizontal porous layer. They calculated the critical values of finite amplitude, oscillatory, and monotonic convective instability for DDC and Soret convection using linear stability analysis. Subsequently, the case of anisotropic horizontal porous layer based on the previous paper was studied by Gaikwad

et al. [

27] Using linear and nonlinear stability analysis, they analyzed the critical Rayleigh number, wave number, and oscillation frequency of steady and oscillatory modes. Utilizing linear and weakly nonlinear stability studies, Gaikwad and Dhanraj [

28] initially used the Darcy-Brinkman model to study the DDC with the Soret effect in a binary viscoelastic fluid-saturated horizontally porous layer. They discovered that whereas a positive Soret value accelerates the onset of DDC in stationary mode and has the opposite impact in oscillatory and finite amplitude modes, a negative Soret parameter increases system stability. Bouachir

et al. [

29] investigated DDC flow in a vertical porous chamber filled with a binary mixture exhibiting Soret and Dufour effects. The Darcy-Brinkman model and the Oberbeck-Boussinesq approximation are used to study the impact of the Soret and Dufour effects on convective stability. Overall, the thresholds of oscillatory, overstable, and stationary convection were greatly impacted by the Soret and Dufour effects.

Due to the significant differences in molecular diffusivity, DDC leads to complex flow structures and, consequently, the transport of heat and solute concentrations with different time and length scales. The majority of prior investigations used pure DDC for natural convection in a vertical porous material influenced by horizontal heat and solute concentration differences. Therefore, the Soret effect is introduced in this paper to describe the mass flux induced by the temperature gradient. Until now, there has been no study on the instability of the Soret effect on DDC in a saturated vertical porous layer of Oldroyd-B fluid. Therefore, the present work aims to investigate the linear stability of DDC of Oldroyd-B fluid in a vertical porous layer with the Soret effect. The manuscript is structured as follows.

Section 2 presents the mathematical model that outlines the governing equations. The linear stability analysis and numerical procedures are given in

Section 3 and

Section 4, respectively. In

Section 5, we present the results and discussion, while the last section contains the conclusions that we have drawn.

5. Results and Discussion

With the use of the Chebyshev collocation method, the linear stability of the Soret impact on DDC in a vertical layer of Darcy-Brinkman porous media is numerically explored. The Darcy-Rayleigh number RaT, the solute Darcy-Rayleigh number RaS, the Lewis number Le, the relaxation parameter λ1, the retardation parameter λ2, the Soret parameter Sr, the Darcy-Prandtl number PrD, the Darcy number Da, and the normalized porosity of the porous medium η are some of the significant non-dimensional parameters that control the flow.

Firstly, the parameter ranges are discussed based on the works by Shanker

et al. [

7] and Swamy

et al. [

24] The value of

λ1 must be greater than that of

λ2 (Bird

et al. [

32]; Hirata

et al. [

33]). The range of values for the Soret parameter is −1 <

Sr < 1 (Bouachir

et al. [

29]). In fact, the Darcy-Prandtl number

PrD can be expressed by Prandtl number, Darcy number, porosity, and specific heat ratio, i.e.,

PrD=

γεPr/Da.

PrD depends on the properties of the fluid and the porous matrix. For a sparse porous media,

Da ranges from 0.001 to 1,

γ changes from 0 to 1,

ε is around 0.5, and the typical Prandtl number for viscoelastic fluids is 10. Therefore,

PrD varies from 5 to 5000.

Table 1 provides a convergence analysis for numerical calculations by altering the order of the Chebyshev polynomials. Employing 30 to 45 configuration points in Eq. (50), it is found that the value of

aci is independent of the polynomial order

N between 35 and 45 and achieves 4-digit point precision. Therefore, all numerical results given subsequently are obtained by taking

N = 40 in the Chebyshev expansion.

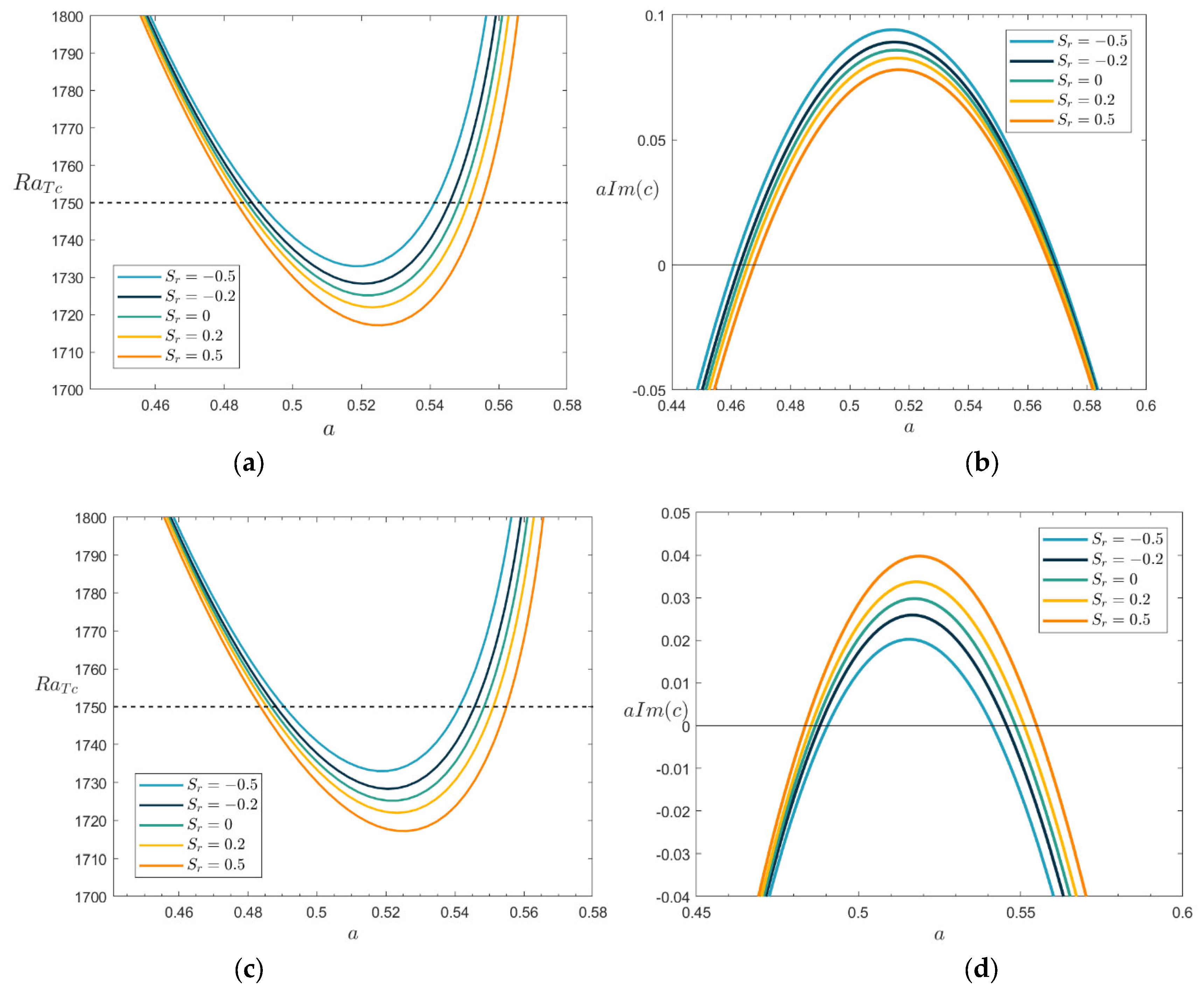

Figure 3(a)–3(d) show the growth rate for the Soret parameter as well as the neutral stability curves. In the neutral stability plot, it is stable outside of the tongue-shaped region and unstable within it. The minimum value of the neutral stability curve indicates the critical condition for the flow changing from a stable to an unstable state. In this paper, the corner symbol

c represents the critical value, and the value of

RaTc is the critical value of the flow between stable and unstable; when

RaT>

RaTc, it means that the flow is unstable, and when

RaT <

RaTc, it means that the flow is stable.

Figure 3(a) depicts the effect of different Soret parameters

Sr on the neutral stability curve when

Le = 1. When

Sr increases, the minimum value of

RaTc moves towards the large value of wave number

a, indicating that

Sr reduces the width of the cell. In addition,

Sr =0 denotes the neutral stability curve without the Soret effect. For

Sr <0, we find that the minimum value of

RaTc decreases with the increase of the negative Soret parameter, which indicates that it weakens the stability of the system. For

Sr >0, the minimum value of

RaTc increases with the increase of the positive Soret parameter, which indicates that it enhances flow instability. It shows that positive

Sr results in a more stable flow, and negative

Sr has the opposite effect.

Figure 3(b) shows the growth rate curve for

RaT = 1750, i.e., the growth rate case at the dotted line in

Figure 3(a). In

Figure 3(b), the growth rate is plotted using the same parameters. The larger the positive

Sr is, the smaller the growth rate is, indicating that the positive

Sr increases the stability of the system; the more significant the negative

Sr is, the larger the growth rate is, indicating that the negative

Sr weakens the stability of the system, and the same conclusion as

Figure 3(a) is obtained.

Figure 3(c) shows the neutral stability curve when

Le=2.

We find that for

Sr<0, the minimum value of

RaTc increases with the increase of the negative Soret parameter, which indicates that it improves stability. For

Sr >0, the minimum value of

RaTc decreases with the rise of the positive Soret parameter, which suggests that it reduces stability. It shows that the positive

Sr parameter has an unstable effect, and the negative

Sr parameter has a stabilizing effect. It is opposite to the conclusion for

Le =1.

Figure 3(d) shows the growth rate curve when

RaT=1750 and

Le=2. The larger the positive

Sr is, the bigger the growth rate is; the larger the negative

Sr is, the smaller the growth rate is, indicating that the negative

Sr enhances the stability, and the same conclusion as that of

Figure 3(c) is obtained. In summary, we find that the positive and negative values of

Sr have different effects on the instability, and the size of

Le affects the impact of

Sr on the instability of the flow.

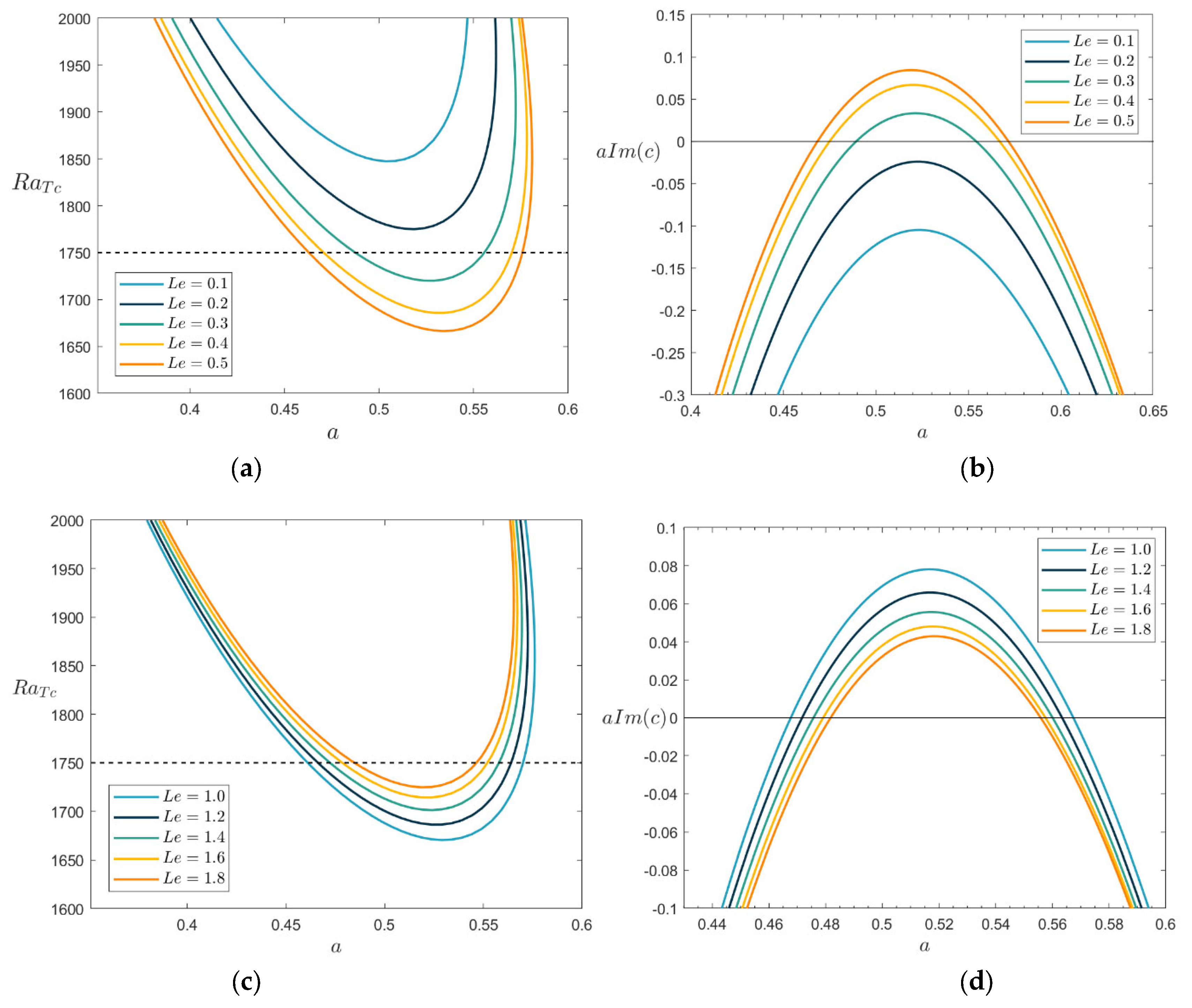

Figure 4(a)-(d) illustrate the neutral stability curves and growth rate curves for different Lewis numbers

Le.

Figure 4(a) depicts that the minimum value of

RaTc decreases with increasing

Le for

Le <0.5, indicating that

Le promotes flow instability at this point.

Figure 4(b) shows the growth rate curve when

RaT = 1750 under the parameters of

Figure 4(a). We find that the larger

Le is, the larger the growth rate is and the more unstable the flow is. It indicates that

Le plays a weakening effect on the stability of the flow when

Le <0.5.

Figure 4(c) suggests that

Le promotes the stability of the flow when

Le > 1. Under this parameter,

Figure 4(d) depicts the growth rate when

RaT = 1750, i.e., the growth rate corresponding to the neutral stabilization point intersecting the dashed line in

Figure 4(c), and the growth rate is found to decrease with increasing

Le. In summary, we find that

Le has a dual effect on the instability of the flow.

Table 2 shows the values of

Lec1 for different

Sr. According to the table,

Lec1 decreases with increasing

Sr and remains around 0.7. Therefore,

Le enhances the flow instability when

Le < 0.7 and inhibits the flow instability when

Le > 0.7.

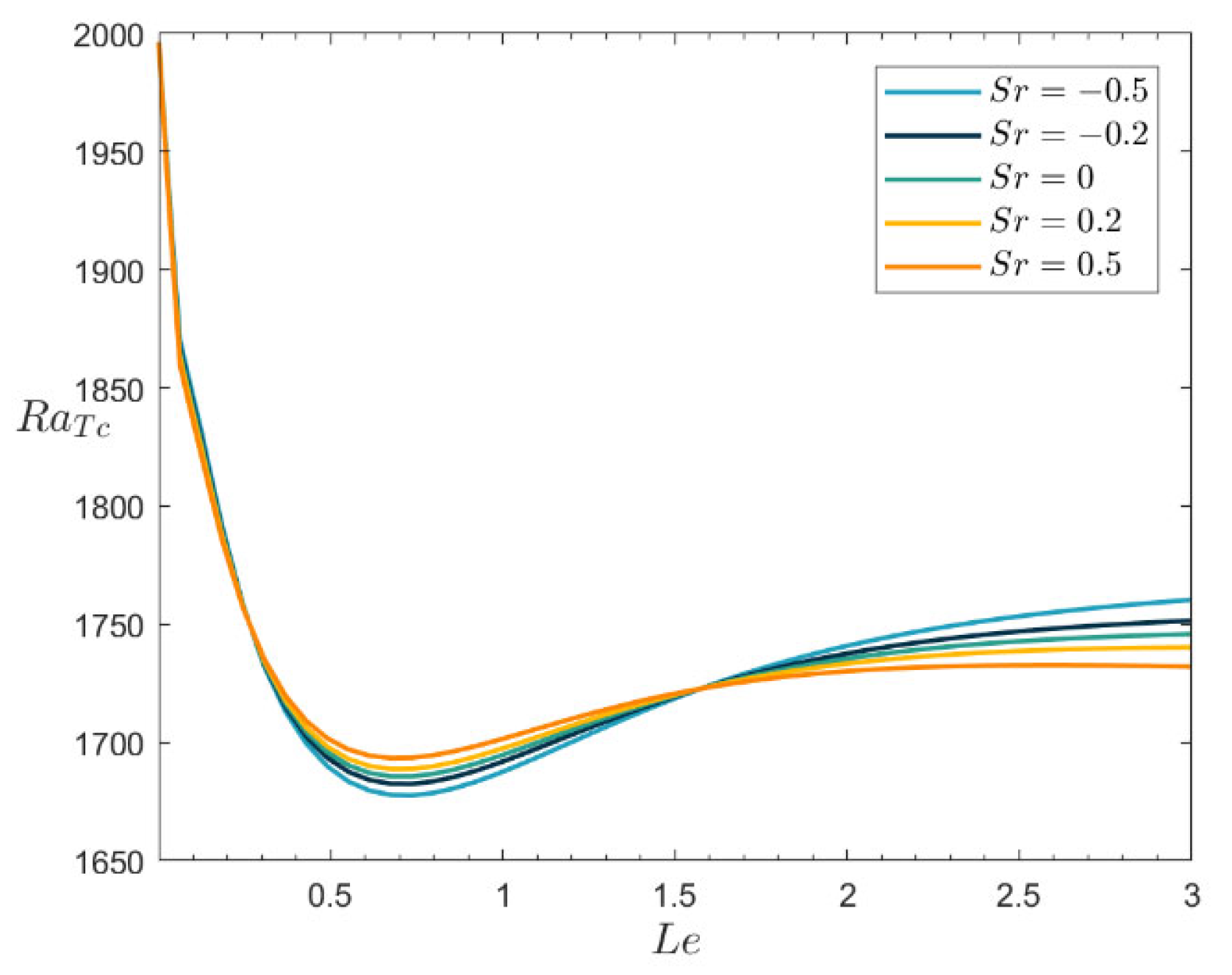

Figure 5 illustrates the neutral stability curves of

RaTc as

Le varies for different Soret parameters

Sr. As

Le increases from zero, the value of

RaTc first decreases and then increases. This suggests that there is a critical value

Lec1. This indicates that

Le has both promoting and inhibiting effects on the instability of the flow. The minimum value of

RaTc corresponds to a critical

Le value

Lec1, which promotes the instability of the flow when

Le <

Lec1 and inhibits the instability of the flow when

Le >

Lec1. According to the graph, it is found that there is also a critical value of

Le,

Lec2=1.5735, when

Le <

Lec2,

Sr contributes to the instability of the flow, and when

Le >

Lec2,

Sr inhibits the instability of the flow. Thus, we find that

Le and

Sr have a dual role in the stability of the flow and that the magnitude of

Le influences the role of

Sr.

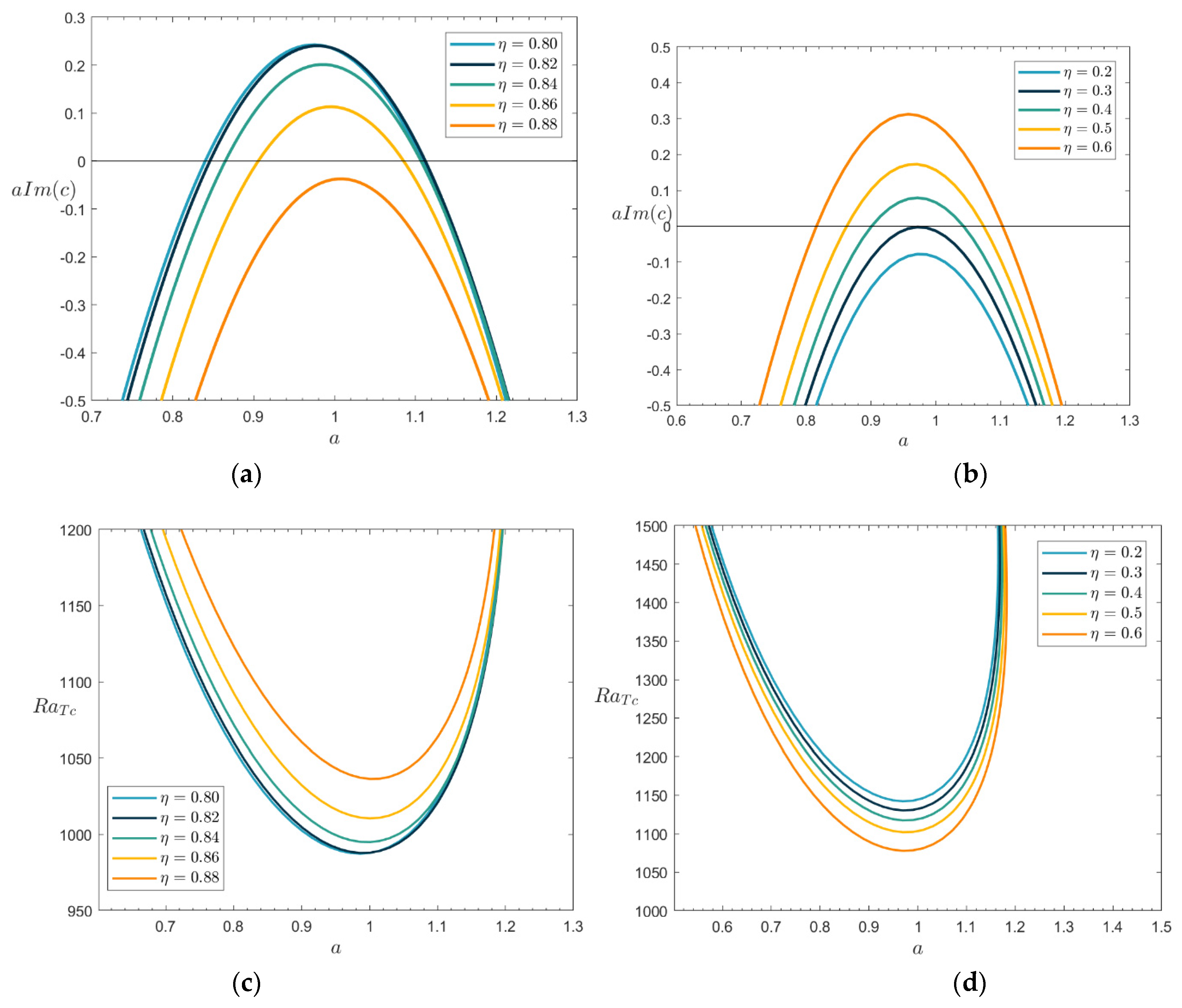

Figure 6(a)-(d) illustrate the neutral stability curves and growth rate curves for different normalized porosity

η.

Figure 6(a) shows that

η promotes flow instability at this point.

Figure 6(b) shows the growth rate profile when

RaT = 1130 under the parameters of

Figure 6(a). We find that the larger

η is, the larger the growth rate is and the more unstable the flow is. It indicates that

η plays a weakening effect on the stability of the flow when 0.2<

η < 0.6.

Figure 6(c) depicts that the minimum value of

RaTc increases with

η when 0.8<

η < 0.88, indicating that

η promotes the stability of the flow. In

Figure 6(d), the growth rate decreases with increasing

η. In summary,

η acts differently on the instability of the flow at different values.

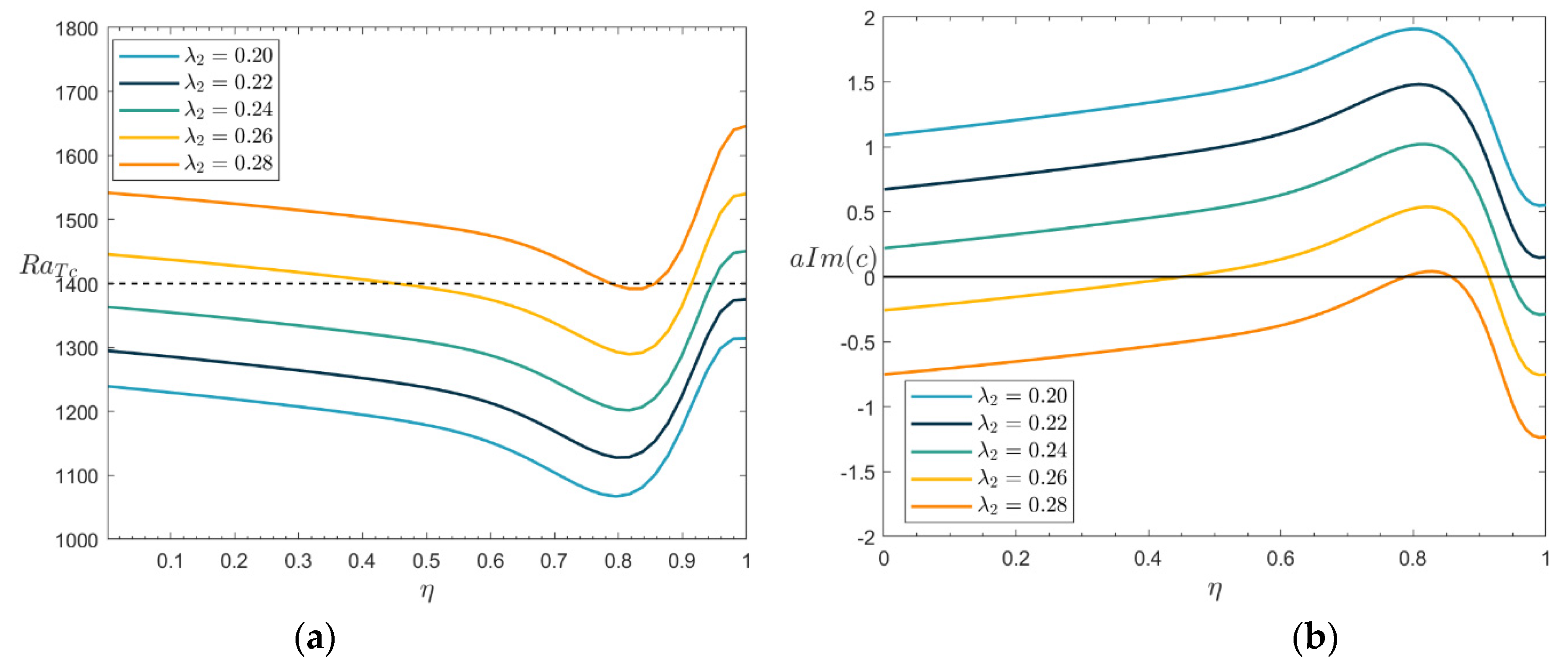

Figure 7(a) demonstrates the neutral stability curve of

RaTc as

η varies for different relaxation parameters

λ2. As

η increases from zero, the value of

RaTc decreases and then increases. This suggests that

η has a dual effect on the instability. The minimum value of

RaTc corresponds to a critical value

ηc, which enhances the instability when

η <

ηc and inhibits the instability when

η >

ηc. In addition, the minimum value of

RaTc increases with

λ2, indicating that

λ2 promotes flow stability.

Figure 7(b) shows the growth rate when

RaT = 1400 for the parameters of

Figure 7(a). It shows that when

λ2 increases, the growth rate is smaller, and the flow is more stable.

According to

Table 3,

ηc increases with increasing

λ2 and stays around 0.8. Thus, we conclude that

η enhances the instability of the flow when

η<0.8 and suppresses the instability of the flow when

η>0.8.

The neutral stability curves for various parameters

λ1 when

PrD = 50 are shown in

Figure 8(a). When

λ1 is larger, the minimum value of

RaTc is smaller, showing that the flow is more stable. In

Figure 8(b), for

PrD =200, it is found that the minimum value of

RaTc increases for larger

λ1, indicating a more unstable flow. When

PrD =600,

λ1 promotes the stability of the flow in

Figure 8(c). In order to explore the effect of

PrD on the role of

λ1, the neutral stability curve of (

PrD,

RaTc) is plotted, i.e.,

Figure 8(d). As

PrD increases, the value of

RaTc decreases, then increases and decreases continuously. This indicates that

PrD has a dual effect on the stability of the flow. According to the images, we can find the critical values of PrD, PrDc1 and PrDc2. When PrD < PrDc1 or PrD > PrDc2, PrD has an inhibiting effect on the instability, and when PrDc1 < PrD < PrDc2, PrD has a facilitating effect on the instability. According to

Figure 8(d), when λ1 = 0.65, the specific critical values PrDc1 is 50.2 and PrDc2 is 398.8. Moreover, the magnitude of PrD affects the stability of λ1. When PrD < 110.8 or PrD > PrDc2, the larger λ1 is, the smaller RaTc is, indicating that λ1 inhibits the stability. Interestingly, when 110.8 < PrD < PrDc2, λ1 suppresses the flow instability. This suggests that λ1 also has a dual effect on the flow stability and is influenced by the size of PrD.

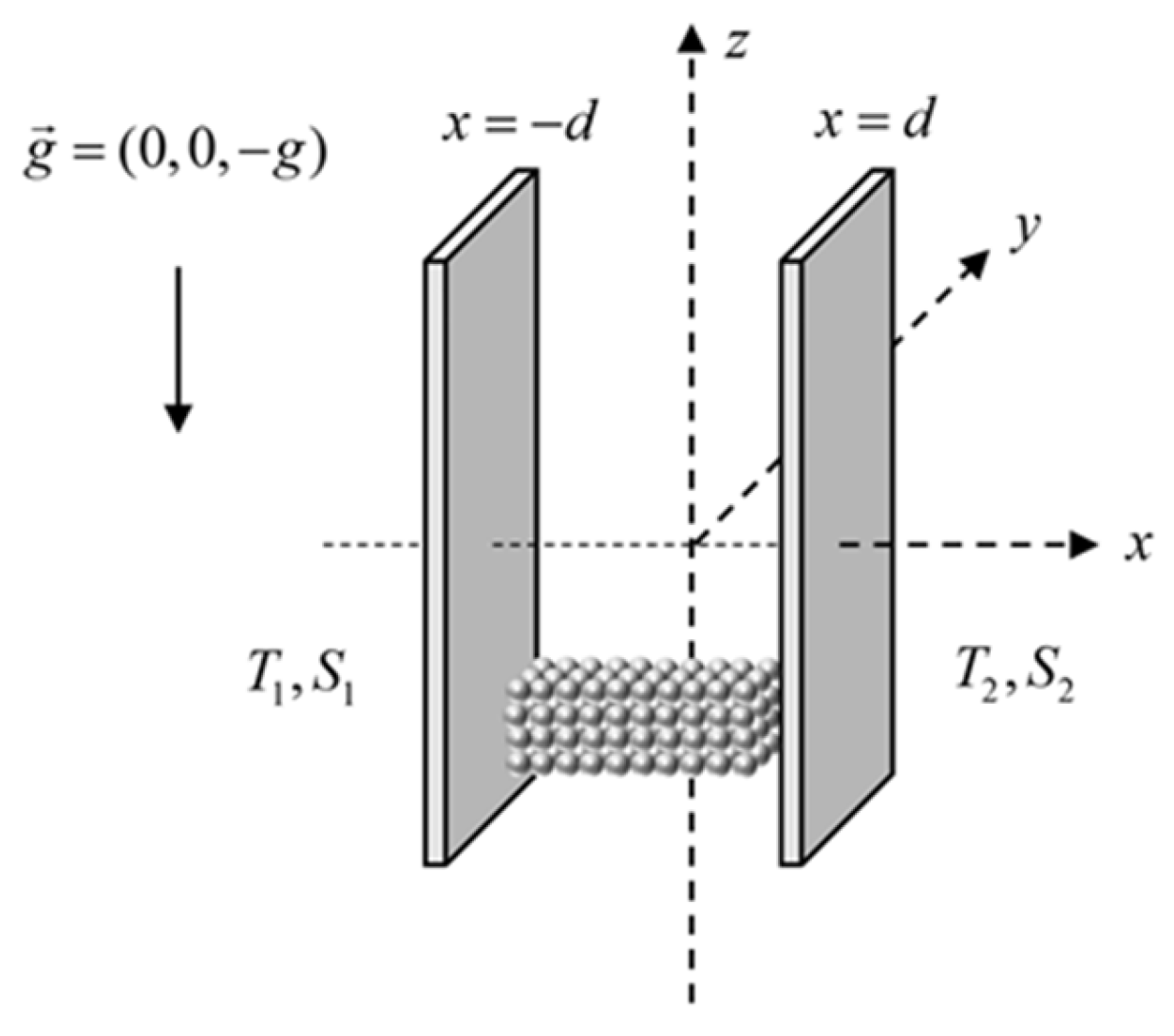

Figure 1.

Graphic of the Physical Issue.

Figure 1.

Graphic of the Physical Issue.

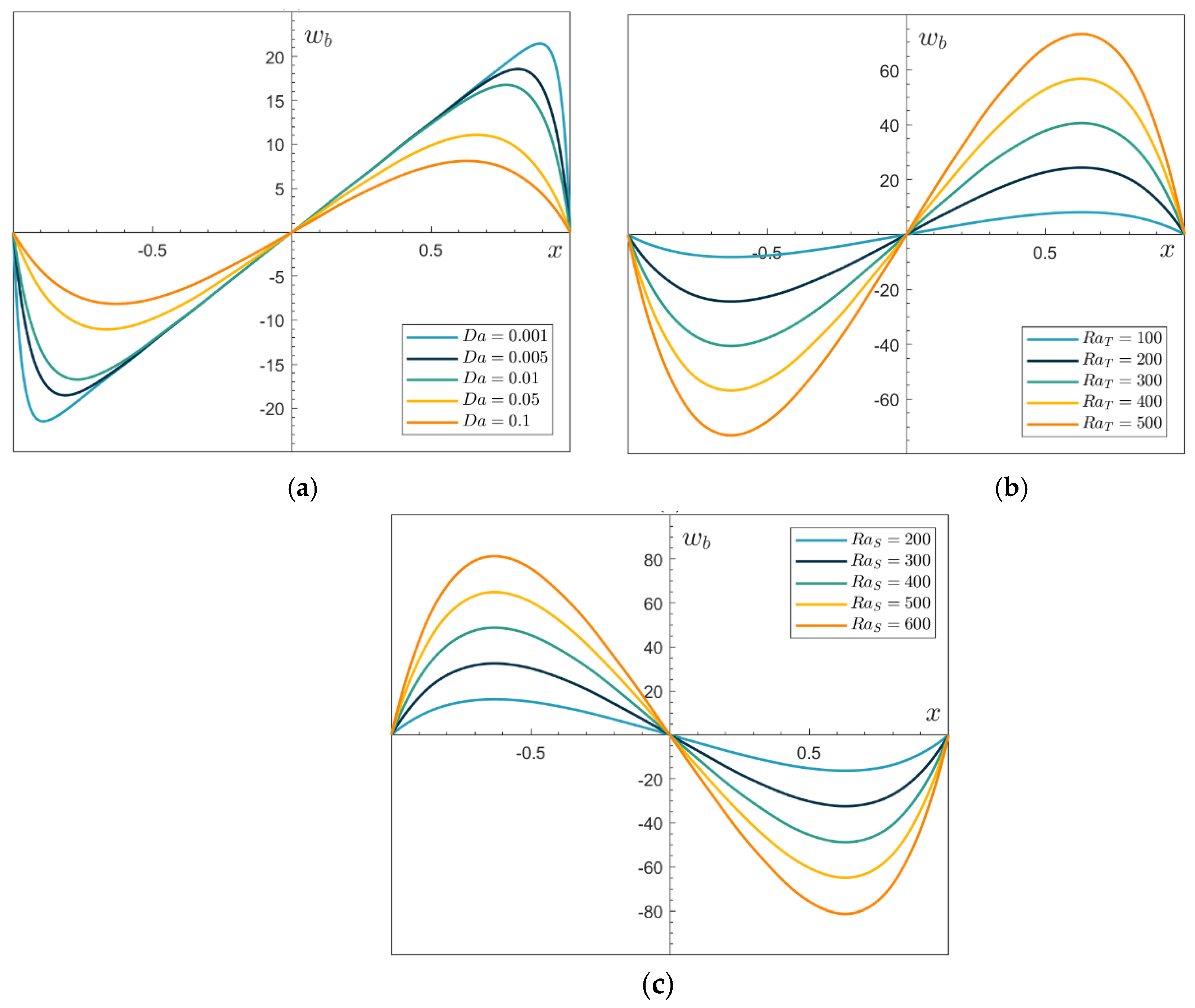

Figure 2.

Basic velocity profiles for different values of (a)RaT=100, RaS=50, (b)Da=0.1, RaS=50, (c) Da=0.1.

Figure 2.

Basic velocity profiles for different values of (a)RaT=100, RaS=50, (b)Da=0.1, RaS=50, (c) Da=0.1.

Figure 3.

Plots of the neutral stability curves and the growth rate for various values of (a)Le=1, (b)Le=1, RaT=1750, (c)Le=2, (d)Le=2, RaT =1750, when Da=0.1, PrD=50, λ1=0.4, λ2=0.2, Le=2, RaS=50, η=0.5.

Figure 3.

Plots of the neutral stability curves and the growth rate for various values of (a)Le=1, (b)Le=1, RaT=1750, (c)Le=2, (d)Le=2, RaT =1750, when Da=0.1, PrD=50, λ1=0.4, λ2=0.2, Le=2, RaS=50, η=0.5.

Figure 4.

Plots of the neutral stability curves and the growth rate when Da=0.1, PrD=50, λ1=0.4, λ2=0.2, Sr=-0.5, RaS=50, RaT=1750, η=0.5.

Figure 4.

Plots of the neutral stability curves and the growth rate when Da=0.1, PrD=50, λ1=0.4, λ2=0.2, Sr=-0.5, RaS=50, RaT=1750, η=0.5.

Figure 5.

Plots of the neutral stability curves when Da=0.1, PrD=50, λ1=0.4, λ2=0.2, RaS=50, η=0.5, a=0.5.

Figure 5.

Plots of the neutral stability curves when Da=0.1, PrD=50, λ1=0.4, λ2=0.2, RaS=50, η=0.5, a=0.5.

Figure 6.

Plots of the neutral stability curves and the growth rate when Da=0.1, PrD=100, λ1=0.4, λ2=0.2, RaS=50, η=0.5, Le=2, (b) RaT=1130, (d) RaT=1030.

Figure 6.

Plots of the neutral stability curves and the growth rate when Da=0.1, PrD=100, λ1=0.4, λ2=0.2, RaS=50, η=0.5, Le=2, (b) RaT=1130, (d) RaT=1030.

Figure 7.

Plots of the neutral stability curves and the growth rate. (a) Da=0.1, PrD=100, λ1=0.4, λ2=0.2, RaS=50, Le=2, Sr=0.5, a=π/4, (b) Da=0.1, PrD=100, λ1=0.4, λ2=0.2, RaS=50, Le=2, Sr=0.5, a=π/4, RaT=1400.

Figure 7.

Plots of the neutral stability curves and the growth rate. (a) Da=0.1, PrD=100, λ1=0.4, λ2=0.2, RaS=50, Le=2, Sr=0.5, a=π/4, (b) Da=0.1, PrD=100, λ1=0.4, λ2=0.2, RaS=50, Le=2, Sr=0.5, a=π/4, RaT=1400.

Figure 8.

Plots of the neutral stability curves and the growth rate for different values of (a) PrD=50, (b) PrD=200, (c) PrD=600, (d)a=π/10, when Da=0.1, Le=2, λ2=0.2, RaS=50, η=0.5, Sr=0.5.

Figure 8.

Plots of the neutral stability curves and the growth rate for different values of (a) PrD=50, (b) PrD=200, (c) PrD=600, (d)a=π/10, when Da=0.1, Le=2, λ2=0.2, RaS=50, η=0.5, Sr=0.5.

Table 1.

The Chebyshev collocation method's convergence process when Da=0.1, λ1=0.4 λ2=0.2, Le=2, PrD=100, RaT=1800, RaS=50, η=0.5, Sr=0.5.

Table 1.

The Chebyshev collocation method's convergence process when Da=0.1, λ1=0.4 λ2=0.2, Le=2, PrD=100, RaT=1800, RaS=50, η=0.5, Sr=0.5.

| |

The growth rateaci

|

| N |

a=0.5 |

a=1 |

a=1.5 |

| 30 |

1.371890 |

2.653114 |

-3.712508 |

| 35 |

1.371895 |

2.653438 |

-3.712476 |

| 40 |

1.371895 |

2.653448 |

-3.712474 |

| 45 |

1.371895 |

2.653448 |

-3.712474 |

Table 2.

Critical values of Lewis number Lec when Da=0.1, PrD=50, λ1=0.4, λ2=0.2, RaS=50, RaT=1750, η=0.5.

Table 2.

Critical values of Lewis number Lec when Da=0.1, PrD=50, λ1=0.4, λ2=0.2, RaS=50, RaT=1750, η=0.5.

| Sr |

Critical values of Lewis number Lec1 |

|

a=0.4 |

a=0.5 |

| -0.5 |

0.7578 |

0.7147 |

| -0.2 |

0.7525 |

0.7106 |

| 0 |

0.7485 |

0.7066 |

| 0.2 |

0.7431 |

0.7025 |

| 0.5 |

0.7357 |

0.6944 |

Table 3.

Critical values of normalized porosity ηc when Da=0.1, PrD=100, λ1=0.4, λ2=0.2, RaS=50, η=0.5, Le=2, Sr=0.5.

Table 3.

Critical values of normalized porosity ηc when Da=0.1, PrD=100, λ1=0.4, λ2=0.2, RaS=50, η=0.5, Le=2, Sr=0.5.

| |

Critical values of normalized porosity ηc |

|

λ2

|

a=π/6 |

a=π/5 |

a=π/4 |

| 0.2 |

0.7895 |

0.7908 |

0.7966 |

| 0.22 |

0.7969 |

0.7990 |

0.8057 |

| 0.24 |

0.8051 |

0.8071 |

0.8118 |

| 0.26 |

0.8112 |

0.8153 |

0.8209 |

| 0.28 |

0.8194 |

0.8215 |

0.8270 |