1. Introduction

The Santa Faz Pilgrimage stands as a testament to Alicante’s rich intangible cultural heritage, encapsulating not only regional devotion but also unique historical narratives integral to Spanish cultural identity. Recognized as one of Spain's oldest pilgrimages, its historical and religious roots contribute to Alicante's distinct identity, fostering a living connection to the past within the present framework of sustainable tourism practices.

The Santa Faz Pilgrimage stands as a crucial element within Alicante’s intangible cultural heritage, embodying traditions that have been preserved for over six centuries. This pilgrimage not only reinforces local identity but also aligns with broader cultural tourism strategies that emphasize experiential and sustainable tourism practices. In this way, the pilgrimage can be viewed as part of a shift toward ‘slow tourism’ or ‘sustainable pilgrimage routes’ in Europe, where engagement with place, community, and nature is emphasized over traditional forms of mass tourism.

1.1. The Natural Environment

The landscape of the Campo de Alicante region is defined by a dynamic interaction between internal tectonic forces and external erosion, resulting in a varied topography. Predominantly flat, this region also features a series of smaller elevations and mountain ranges, especially to the north. This topographic variation arises from a complex structural compartmentalization of the terrain. Formations such as the crests of Calvario and Monte del Pino de Alberola, as well as the Lomas de Orgegia, shape the landscape. Additionally, prominent features like Benacantil, Molinet, Serra Grossa, and Tossal, connected by the hills of Creu de Fusta and Vistahermosa, contribute significant geomorphological diversity [

1] (

Figure 1).

In the Campo de Alicante region, the geological composition of the landscape is mainly characterized by Pliocene sandstones and Upper Cretaceous marl and limestone formations. The flat areas, predominantly composed of detrital sediments, are the result of fluvial transport processes and represent the most suitable zones for agricultural practices [

2]. Additionally, there are humid areas, such as Albufereta and Marjal, whose agricultural development required drainage processes for effective use [

3,

4].

Favorable agricultural conditions in the Campo de Alicante region include gentle slopes and the morphology of alluvial fans, which facilitate land cultivation. Furthermore, the Seco, Montnegre, or Verd River supplies water to the area, with a Mediterranean-pluvial regime characterized by peak flows in spring and autumn, low flows in summer, and potential flooding in autumn [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7].

1.2. Space and Its Organization

The Huerta de Alicante has long been inhabited and cultivated due to its ecological value and the traditional organization of its space. The plains south of the Seco River benefit from irrigation, enhancing productivity and crop diversification [

7,

8,

9,

10].

The modern irrigation system dates back to the period following the Christian occupation in the late Middle Ages, with the construction of the Tibi Dam in the 16th century (the first in Europe) to regulate water flow. Improvements to irrigation infrastructure included the construction of weirs, reservoirs, and storage tanks [

10,

11] (

Figure 2).

The network of primary and secondary canals distributes water throughout the Huerta, using the Acequia Mayor as its main artery. Despite the irrigation systems in place, the Huerta has consistently faced water scarcity, often referred to as an “enhanced dryland” [

7,

11].

Settlement in the Huerta has developed hierarchically, with Alicante as the main center. Smaller population centers include San Juan, Mutxamel, Benimagrell, Santa Faz, Tángel, Villafranqueza, and Lloixa. The network of roads and canals has been fundamental in shaping the territory.

In the study area, agricultural practices have evolved significantly over the centuries. Before the 16th century, predominant crops included wheat, barley, olives, figs, carob, almonds, barrilla, esparto grass, and wine, with vines becoming the primary crop in the 16th century, though they later declined. While olive cultivation was reintroduced, it remains sparse. Currently, citrus fruits are the only stable crops. Almond and fig production grew notably in the 18th century, but mulberry trees disappeared [

7,

12].

In general, crops in the Huerta were limited and mainly for subsistence. Tomatoes and winter beans thrived, though today tomato cultivation is mainly outside the traditional Huerta, which itself faces near-total abandonment [

1,

7].

Analysis of the Huerta de Alicante’s territory reveals three categories of traces left by traditional land use: ancient routes, irrigation systems, and remnants of traditional crops.

The historical routes served as access corridors to the Huerta towers. These paths follow a hierarchical territorial structure extending from the national highway 332 to the sea. However, progressive alterations to these routes are evident as they approach the coastline [

1].

The road network in the study area originated from the ancestral Camino de la Santa Faz or Camino de Valencia, now converted into a national highway, and presents variously modified routes:

Camino de la Cruz de Piedra or Camí Vell de l’Ametler, a main axis, retains accessibility and functionality, allowing passage to adjacent properties and land. Despite being an unpaved road, it is in good condition. However, the original connection between Cruz de Piedra and San Juan is now materially unfeasible.

Camino de Benimagrell or Camí de Reixes, connecting Cruz de Piedra with Benimagrell, still maintains operational access, flanked by various historical towers along its route.

Camino de la Huerta lacks continuity, especially at its eastern end, where emerging urbanization obstructs its potential link with Camino de la Playa de San Juan, with Torre Conde situated along its midpoint.

Camino de la Playa de San Juan or Camino del Ciprés has been fragmented due to new infrastructure developments that disregard its original route and is increasingly absorbed by the area’s urbanization. Initially, it linked several historic towers.

The southernmost Camino de la Albufereta has been completely eliminated due to urban expansion; it formerly connected Torre Castillo with Torre Ferrer.

Finally, Camino de la Cadena, the only transversal route in this sector, faces connectivity challenges after intersecting Camino de Benimagrell, with several towers located along its length.

Additionally, a network of secondary roads has been documented, exhibiting a transverse arrangement relative to the primary routes, reflecting historical territorial organization and providing access to homes or land interspersed among the main routes. Noteworthy features of these paths include rows of trees and remnants of dry-stone walls (

Figure 3).

The irrigation system in the Huerta of Alicante is another crucial element of traditional spatial organization. It consists of a main water distribution network, along with branches and complementary components [

6,

7].

Regarding crops, there is a general abandonment of agricultural activity in the analyzed area, except for a few plots with citrus trees [

1] (

Figure 4).

1.3. Housing, Defense, and Water in the Huerta of Alicante

The Huerta of Alicante, due to its unique characteristics, has been an ideal location for human settlement since prehistoric times. The availability of water supported rich vegetation and abundant wildlife, both highly valued as food sources. Additionally, the extreme living conditions of a marshland were balanced by the protection it offered to any settlement in the area. Lastly, its broad Mediterranean frontage facilitated the arrival of foreign cultures, as well as potential invaders, smugglers, and quick raids in the region [

9,

13,

14].

Between the late 15th and early 17th centuries, the Mediterranean coast experienced significant instability. This was primarily due to two factors: the power of the Ottoman Turkish Empire in Europe and the rise of North African states influenced by the activities of Berber pirates. As a response, substantial fortification efforts were undertaken along the coast in the 16th century, aimed at both defending the region and monitoring the Morisco population and potential enemies [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

The 16th century, as noted, saw an intensification of these incursions along the coast of the Kingdom of Valencia [

22]. During the Monzón Courts of 1528, presided over by Charles I, the three estates petitioned the monarch to take measures for the "protection of the current kingdom," considering the economic damage caused by continuous corsair attacks on coastal communities [

3,

15,

17,

18].

The Monzón Courts of 1552 again reflected the Valencians' concerns, establishing a “land-based guard, not by sea” to ensure “greater fulfillment of the said coast and maritime land fortification and defense.” This guard, typically made up of local knights—the only ones with horses and arms—were known as “companyies de cavalls.” These landowners were obliged not only to warn local farmers of possible raids but also to defend and shelter them in fortified houses, known as Casas-torre, built for this purpose [

16].

In 1553, Alicante was visited by Don Jerónimo Arrufat, a judge of the Royal Audience and Royal Commissioner. From his visit, we know that the instability in the Huerta area was such that the construction of numerous Casas-torre had begun—and he urgently ordered their completion. Towers such as Bendicho, Gaspar Roig, and Joan Sena, all located in the “orta de Alacant,” were mentioned [

16,

17].

Indeed, during the 16th century, the construction of towers, watchtowers, and castles along the Alicante coast was carried out under orders from Philip II to fortify the coastline. These constructions were overseen by Juan Bautista Antonelli during the term of Viceroy Vespasiano Gonzaga. The towers provided refuge and security for local workers (inland towers) and served as lookout points for detecting foreign ships—often Berber pirates—in the coastal towers [

15,

16,

18,

21,

23] (

Figure 5).

This issue, however, must have persisted well into the 17th century, as evidenced by graffiti found a few years ago in the Casa Capiscol, dated to that period and fortunately preserved by the Archaeology Services of the Alicante City Council [

24,

25] (

Figure 6).

In the geographical area of the province of Alicante, the network of coastal and Huerta watchtowers is distinguished by unique features that make it a singular example within the Spanish Mediterranean context. The housing typology with towers is found in the highest density around the Huerta of Alicante, particularly in the area known as "La Condomina." These homes were designed to combine residential functions with agricultural characteristics, as well as defensive and refuge aspects for their inhabitants [

21,

26].

According to Lamperez, these tower houses, inherited from the Early and Late Middle Ages, varied in form depending on the economic power of the landowner, yet all included a defensive tower as an essential element. This tower served as the final bastion where inhabitants could seek refuge in case of attack [

27].

Various authors identify similar typological roots in different types of rural residences across Spain. For instance, Alvarez Gallego notes that the quadrangular mansion of Roman architectural civilization is essentially similar to the structure of the Galician pazo and highlights that the towers attached to pazos echo their origins as feudal mansions [

28]. Seijó Alonso suggests that the residences were attached later, during the period when Berber pirates ravaged villages, necessitating the establishment of settlers on properties due to intensive land cultivation [

26,

29]. Varela mentions the reuse of Huerta houses over time, considering them as an evolution of the Roman type and emphasizing their primary agricultural use [

30]. Lamperez considers the Roman agricultural house type significant due to its enduring presence over centuries, from the villa and Visigoth vicus to the Late Medieval tower, the 16th-century manor house, and the modern Andalusian cortijo [

27].

Thus, the casa-torre (tower house) can be specifically defined as a residence that, while adhering to the general typology mentioned, includes a refuge tower in response to the historical and social conditions prevailing from the latter half of the 16th century until the early 18th century. The form of these residences derives from the medieval interpretation of the Roman house, particularly in its agricultural use.

As for the location of these towers, authors differ. Some report a total of 24 towers within the municipalities of Alicante, San Juan, Campello, and Mutxamel, while others cite 23 in this area. According to Varela, up to 28 towers were recorded in 1979, although two of these (Rizo and Tres Olivos) have recently disappeared. This study identifies the presence of 30 towers, including those whose known remains suggest their past existence, either through their scale or documented references. The distribution of these towers is as follows: 22 in the municipality of Alicante (La Condomina), 6 in the municipality of San Juan de Alicante, and 2 in the municipality of Mutxamel [

15,

21,

26,

29,

30] (

Figure 7).

The existence of irrigation canals in the area is crucial for understanding the settlement patterns. According to Crespo Giner, the construction of the Gualeró canal was contemporaneous with the San Juan weir in 1656, indicating a time gap between the construction of the towers and the residences [

31]. However, Sala and Sanchis suggest that the landowners in La Condomina might have restored an old canal with the intent of building a dam on the river [

31,

32,

33] (

Figure 8).

Throughout the 18th century, and especially in the 19th century, these structures ceased to be directly related to agricultural use and became almost exclusively estates and recreational villas. In recent years, property owners have increasingly abandoned these structures in favor of other types of buildings and leisure sites, leading to a process of degradation and deterioration affecting the entire area. Additionally, land subdivisions and urban developments have altered the original structure and functional balance of the region, erasing certain pathways, remnants of the irrigation system, and the visual relationships that were integral to its purpose.

Completing this picture of the Huerta of Alicante is the construction of the Tibi Dam in the 16th century—the oldest in Europe, excluding Roman structures in Mérida—which addressed another of the Huerta’s persistent issues, alongside Berber raids: the lack of water for irrigation. This issue, despite the dam’s construction, led to the Huerta of Alicante being largely dedicated to dryland farming, except along riverbanks and adjacent areas. The region became renowned for its production of raisins, fresh and dried figs, and especially Fondillón wine [

11].

The recent transformation of this area from an urban planning perspective, with little consideration for structures, paths, livestock trails, canals, etc., threatens to turn this legacy into history—unless preventive action is taken.

1.4. The Relic and Miracles of the Santa Faz

The Santa Faz Pilgrimage stands as a profound reflection of Alicante's enduring cultural identity, blending religious devotion with local heritage. As one of the region’s most significant intangible heritage practices, the pilgrimage reflects centuries-old community values, embodying Alicante’s unique position within Spain’s broader cultural and historical landscape.

Comparable to other European pilgrimage routes, the Santa Faz Pilgrimage aligns with the European tradition of religious journeys that integrate spiritual, communal, and environmental dimensions. Unlike routes such as the Camino de Santiago, the Santa Faz journey intertwines historical and socio-cultural elements specific to the Mediterranean region, drawing on centuries of localized customs, beliefs, and community participation.

The pilgrimage reflects current perspectives in sustainable cultural tourism by promoting a slow tourism approach, an increasingly recognized method in European pilgrimage sites. Studies in cultural heritage underscore the value of community-led initiatives in preserving intangible heritage, positioning the Santa Faz Pilgrimage as a vital component of Alicante’s identity and as a model for sustainable tourism development.

From a material perspective, the Santa Faz relic is regarded by Christian tradition as one of the three cloths used by Veronica to wipe Jesus’ face during his Passion. The relic arrived in Alicante in the 15th century, brought by Mosén Pedro Mena, a priest from San Juan, who received it from a cardinal in Rome [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39] (

Figure 9).

After repeatedly appearing from the bottom of the chest where the priest safeguarded it, the relic was placed on a wooden panel and displayed in his parish, marking the beginning of its public veneration [

36,

38]

The origin of this tradition dates back to 1489, when three miracles attributed to the Santa Faz relic were historically recorded: the miracle of the tear, the miracle of the three holy faces, and the preaching of Friar Benito of Valencia [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]. According to Viciana, as narrated in the third part of his 16th-century chronicle, the first Santa Faz pilgrimage took place on March 17, 1489, as a prayer procession for rain [

37,

39]. The route followed the Lloixa ravine in San Juan, within the Alicante huerta area, where the Miracle of the Tear occurred. It was at this location that the Council of the city of Alicante later founded and built the Monastery of the Santa Faz in commemoration of this event [

38,

40,

41] (

Figure 10).

Days later, on March 25, with no rain yet, the relic was called upon once more. During its transport, the second miracle, known as the "miracle of the three faces," occurred under the 'Holy Pine' near the Franciscan Convent of Los Ángeles. On this occasion, according to popular tradition, the prayers were answered, and rain finally fell [

35,

36,

42] (

Figure 11).

The relic was kept in the Church of Los Ángeles until 1490, when it was moved to the newly constructed Monastery of the Santa Faz that same year. The sanctuary would later be rebuilt in the 18th century [

35,

36,

41].

Additionally, the Camarín de la Santa Faz, which houses the relic and was built in the 17th century, holds a fascinating history involving artists who played a significant role in its construction and were associated with the Alumbrados sect. The painter of the impressive interior paintings, Conchillos, was even imprisoned by the Inquisition [

41,

43].

1.5. The Santa Faz Pilgrimage

The Santa Faz pilgrimage, popularly known as La Peregrina, is a traditional festivity in the city of Alicante that reflects its culture and popular religiosity. This festival embodies various historical, cultural, ethnological, and ritual meanings [

44]. On one hand, the pilgrimage commemorates a historical event and the popular devotion of the people of Alicante, who journey to the site of the Miracle of the Tear, where a sanctuary was later built to house the relic and provide a place for public worship. On the other hand, the pilgrimage is also a ritual of collective affirmation for the Alicante community, giving the celebration identity meanings as a symbol of brotherhood and belonging to the cit [

40,

42,

45] (

Figure 12).

The Santa Faz pilgrimage is celebrated annually on the second Thursday after Holy Thursday, although it was originally held on March 17. The date change was established in 1663 by the Third Diocesan Synod, which determined that the celebration should be moved to the Thursday following the 'Dominica in Albis' (the second Sunday of Easter) to avoid overlapping with Lent. However, this change was not implemented until 1752 [

34,

35,

36].

This pilgrimage embodies the fervor and devotion of the entire Alicante community, a tradition preserved over half a millennium within local families [

45]. The pilgrimage commemorates the miracles attributed to the sacred relic and has served, over the centuries, as an occasion for pilgrims and the city of Alicante to pray for health, peace, and rain [

36,

38,

46,

47,

48,

49] (

Figure 13).

1.6. The Paths of the Santa Faz

The devotion of Alicante to the relic was so profound that, according to records by Huerta and Melis, several historical routes for the transfers and prayers of the Santa Faz can be traced [

42]. These routes include:

The route from San Juan to Santa Faz and Los Ángeles.

The route connecting Los Ángeles, VistaHermosa, and Santa Faz.

The route starting from San Vicente, passing through Villafranqueza, and ending in Santa Faz.

The route from the city of Alicante following the historic path to Santa Faz, leading to the sanctuary.

Given the patrimonial and historical importance of this last route, we will focus exclusively on it, as it is the path that has traditionally defined the annual pilgrimage of La Peregrina, which concerns us here. It follows the National Highway 332-340, which was once the old route to Valencia and Santa Faz. This highway is closed to traffic on the day of the pilgrimage to facilitate the movement of pilgrims [

40]. The route begins in Alicante and proceeds to the Santa Faz sanctuary, located approximately 8 kilometers away [

37].

The pilgrims accompany the official entourage, composed of the municipal council and religious representatives of the Collegiate Chapter, who carry a replica of the relic to the Monastery [

40,

45,

48] (

Figure 14).

The route passes through the urban center, Lomas de Garbinet, and the Cruz de Fusta. This cross marks the location where the “enemies” encountered each other—two emissaries riding to deliver news of the Miracle of the Tear, who reconciled upon meeting on the path. The cross symbolizes fraternity and forgiveness along the pilgrimage route and served for years as a reference point between Alicante and San Juan [

42,

45,

48] (

Figure 15).

1.7. Official Participation

The pilgrimage is an event open to the public, welcoming both believers and non-believers, as well as the City Council and religious representatives. However, the latter—specifically, the municipal corporation and the religious representatives of the Collegiate Chapter—play a prominent role in the pilgrimage, as the relic is subject to a strict protocol currently overseen by the City Council’s Secretary, rooted in the 1636 Decree that governs the ceremonial procedure [

34,

40,

50].

This 17th-century protocol specifies the procedure for opening the reliquary tabernacle. Four keys are required, two held by the city council and the other two by the ecclesiastical chapter. During this ritual act, the mayor and the Chapter are accompanied by the municipal syndic, the two knight custodians, and the general secretary, who reads the council’s resolution authorizing the opening of the reliquary [

34,

35,

50].

The role of civil authorities is particularly highlighted by the fact that it is the City Council that appoints the individual responsible for opening the relic’s tabernacle once La Peregrina reaches the Monastery. Since the beginning of the festivity, this leading role in the pilgrimage has been held by a civic, not a religious, figure known as the "Syndic Councillor." Historically, the Chief Justice and city jurors presided over the ceremony [

34,

40,

50] (

Figure 16).

Additionally, the City Council also appoints two "Knight Custodians," who symbolize the Huerta of Alicante and guard the relic from the time it leaves its tabernacle until it returns. This tradition dates back centuries and demonstrates the close connection between the Huerta of Alicante and the devotion to the Santa Faz [

34,

40,

50] (

Figure 17).

1.8. The Pilgrimage as Intangible Heritage

It is important to note that a pilgrimage is not merely a procession; it represents a ritual journey that begins in the heart of the city and extends into the countryside. Along the route, stops are made, and religious, devotional, festive, and communal aspects, such as eating and singing, are intertwined. The physical and the spiritual merge, just as the religious and the cultural do [

40,

45,

48,

49]. Therefore, the pilgrimage connects with cultural, landscape, urban, rural, social, and community aspects [

42,

45,

49].

La Peregrina, analyzed as an intangible heritage element, combines various components and variables of significant ethnological interest in understanding and defining popular devotion and religiosity. The pilgrimage reflects the cultural representations of the city of Alicante and its people, as well as connections to ritual and festive manifestations associated with traditional society, where the rural world played a crucial role [

37,

44]. Over the centuries, La Peregrina has evolved into a festivity that, in addition to its ritual and religious significance and popular devotion to the relic, has developed a sociocultural communal value, where cohesion and identity take on their full meaning [

42] (

Figure 18).

During the pilgrimage, religious songs such as

gozos and litanies are sung. The

gozos are hymns of praise and gratitude to the Santa Faz, while litanies are prayers in the form of supplications. These songs are typically sung in Spanish, though versions in Valencian or even Latin can also be found [

35].

In addition to music, the ringing of bells is a prominent feature throughout the pilgrimage. Bells are rung along the route, creating a festive and religious atmosphere. The "toc de campanes" (bell ringing) tradition involves the ringing of church bells during the procession. Traditional music from

tabal and

dolçaina, typical instruments of the Valencian Community, is also heard. Additionally,

gegants i nanos (giants and big-headed figures) parade during the festivities. Firecrackers and fireworks are also part of the pilgrimage [

35,

45,

48].

The pilgrimage also includes the tradition of sharing food in groups. Pilgrims bring food with them, pausing along the way to rest and enjoy typical Easter foods from Alicante, such as rabbit with tomato, beans,

mona (a type of cake with a hard-boiled egg), and local wine from the huerta [

35,

45,

48].

On the day of the pilgrimage, a fair is held in the Santa Faz village. This fair, sustained over centuries, offers pilgrims various goods and objects. Today, it features the sale of artisanal and traditional products, such as wooden walking sticks, farming tools, pottery, and traditional regional foods. Devotional Christian items like rosaries and medallions are also available [

35,

45,

49].

The annual La Peregrina pilgrimage is remarkable for its age and continuity, as well as for its distinctive elements and symbolic significance. The devotion of the people of Alicante over five centuries, the symbolism of the journey and ritual, the religious songs and prayers, popular music (

tabal and

dolçaina), food, and pilgrim attire (smock, scarf, and rosemary-crowned cane) collectively embody socio-religious and identity aspects [

44,

45,

48] (

Figure 19).

The La Peregrina pilgrimage is a clear example of traditional religiosity and popular devotion in Alicante and is considered one of the most emblematic cultural and religious-festive expressions of the community. Passed down through generations, its oral history and the feelings of belonging and identity it generates make it a unique and representative cultural element for the people of Alicante. This cultural expression encompasses other traditional aspects such as music, art, gastronomy, and leisure, and has primarily been transmitted orally. The pilgrimage marks the beginning of spring and is celebrated on the second Thursday after Holy Week, considered an extension of Easter traditions, with group outings to the countryside and picnics as characteristic elements [

44].

For these reasons, the Alicante City Council and the Generalitat Valenciana have decided to declare the pilgrimage an Intangible Cultural Heritage Asset, with the approval process for this designation expected to be completed this year.

Within the field of cultural tourism, routes like the Santa Faz Pilgrimage serve as models for preserving heritage while enhancing local tourism. By analyzing intangible cultural elements through tourism frameworks, the Santa Faz offers valuable insights into sustainable tourism’s role in reinforcing community identity and fostering cultural appreciation beyond religious devotion.

To examine the multidimensional impact of the Santa Faz pilgrimage, this study integrates qualitative and participatory methodologies particularly suited for intangible heritage analysis. Such an approach aligns with frameworks in sustainable tourism and heritage management, as these methodologies prioritize stakeholder engagement and community-based perspectives essential for preserving intangible heritage. This study applies qualitative surveys and in-depth interviews, allowing for a nuanced understanding of how the Santa Faz pilgrimage reflects both cultural values and sustainable development principles within the community.

1.9. Objectives and Significance of Study

The primary objective of this study is to propose the revitalization of the Santa Faz pilgrimage routes as an initiative to preserve Alicante’s cultural heritage and foster sustainable tourism practices. By reestablishing these historical routes, the study aims to align the pilgrimage experience with principles of environmental stewardship, thus contributing to broader conversations in cultural heritage management. Moreover, this initiative proposes a sustainable development model for pilgrimage tourism by integrating reforestation, cultural landmarks, and accessible transit routes. This multidisciplinary approach promises new insights for similar heritage sites, illustrating how traditional cultural practices can coexist with contemporary urban landscapes while offering economic benefits to local communities.

Community engagement forms a cornerstone of this study, emphasizing the active role of local stakeholders in preserving the cultural and socio-economic value of the Santa Faz Pilgrimage. Aligning with sustainable cultural tourism principles, this approach not only strengthens the identity and heritage of Alicante but also recognizes the community as integral to maintaining and revitalizing the pilgrimage routes. Such involvement encourages community-led conservation and establishes the pilgrimage as both a cultural and socio-economic asset to the region. This focus on community reinforces a sustainable framework in which the local population becomes an essential participant in the preservation and promotion of their intangible heritage.

2. Revitalizing the Identity of the Traditional Santa Faz Pilgrimage through Interventions in Alicante's Built Heritage and Natural Landscape

Intangible heritage relies on the preservation of traditions, which are orally passed down through generations. However, additional elements shape the collective imagination surrounding these traditions, with visual heritage being one of the most significant, in which landscape plays a crucial role. While today’s landscape is predominantly urban, it was largely rural in the past.

The Santa Faz Pilgrimage, a centuries-old tradition, is nearing designation as an Intangible Cultural Heritage Asset, underscoring the need to strengthen its legacy by restoring its historical landscape. This landscape has suffered considerable degradation due to modernization and urbanization in the area. Despite the protection granted by its age, uncontrolled urban expansion and poor planning have restricted traditional access routes from Alicante (particularly from San Nicolás-Town hall) and from the Los Ángeles neighborhood, leading to significant landscape degradation associated with this tradition.

The recent renovation of Avenida de Denia did not adequately consider the importance of the pilgrimage, merely relocating the calvary crosses without preserving the ceremonial context. Similarly, urban development around the Los Ángeles neighborhood and towards the Santa Faz district has disrupted traditional routes that once connected the former Monastery of Los Ángeles with the Monastery of Santa Faz, and remnants of the old Convent and Hermitage of Los Ángeles were not preserved.

With urban development progressing as per the General Urban Development Plan (PGOU), the Santa Faz district could soon become unfit for pilgrims to spend the day. Land next to the monastery, along the main road, had been zoned as open housing (EA, for bungalows) in the currently halted PGOU project, showing little regard for the 16th-century monastery and its defensive tower, a declared Cultural Heritage Asset. If these residences are built, the current makeshift park would be replaced with bungalows, limiting or even preventing pilgrims from remaining in the area.

On the other side of the road, behind car sales premises, further development was proposed (UFO-1, Torres de la Huerta Partial Plan). Although green spaces are planned, the pilgrimage tradition should take precedence over urban development, rather than the reverse.

2.2. Objectives

This study aims to propose revitalization of the historical Santa Faz paths, integrating cultural tourism, environmental sustainability, and socioeconomic benefits for the community.

The Santa Faz Pilgrimage is the oldest popular festival in Alicante and is in the process of being declared an Intangible Cultural Heritage Asset.

2.3. Method

An essential objective of this research is to foster meaningful community engagement throughout the project lifecycle. Participatory approaches in the study design facilitate direct community involvement in route planning and heritage conservation. This engagement ensures that the community's voice is integral to preserving the cultural and spiritual dimensions of the pilgrimage, while also supporting socio-economic development. This aligns with best practices in cultural heritage management that emphasize sustainable and community-focused tourism initiatives.

The study adopts a multidisciplinary approach, incorporating historical, urban, environmental, and social analysis to assess the pilgrimage’s impact on Alicante's cultural landscape. Additionally, several alternative routes are proposed, including a "green route" that follows an ancient livestock path as well as the "Water Paths" of Alicante’s historic huerta. This proposal also emphasizes reforestation with native species and the development of sustainable, tourism-oriented infrastructure, including rest areas for pilgrims, aiming to support both environmental and cultural conservation.

2.4. Expected Outcomes and Intervention Fronts

One of the core advantages of revitalizing the Santa Faz Pilgrimage routes is the potential for sustained economic benefits for Alicante’s local businesses and job market. By positioning the pilgrimage as a cornerstone of cultural and heritage tourism, the project is projected to stimulate the local economy through increased visitor numbers and enhanced tourism services. Moreover, the project seeks to prioritize community engagement through direct employment opportunities in areas such as path restoration, maintenance of pilgrimage infrastructure, and development of eco-friendly facilities. These efforts aim to elevate Alicante’s status within the cultural tourism sector while fostering economic resilience for local businesses and entrepreneurs linked to the tourism industry.

The restoration of the Santa Faz pilgrimage routes will contribute to the preservation of cultural heritage, promote sustainable tourism, and create employment opportunities in the region. The challenges and opportunities associated with integrating these routes into the "Cultural Routes of the Council of Europe" have been identified.

Two main intervention fronts emerge: restoring the old paths (Cruz de Piedra, Benimagrell, Costa, Villafranqueza, Los Ángeles, and the Serra Grossa trail), which remain intact yet are currently underutilized, and creating a permanent leisure area for pilgrims around the Santa Faz district, serving as a gathering space between the Juncaret ravine channel and the Cruz de Piedra path.

The introduction of these revitalized paths not only preserves the cultural and historical significance of the pilgrimage but also serves as a catalyst for economic growth by drawing tourists year-round. The project is expected to lead to new opportunities for local artisans, gastronomic businesses, and tourism-focused enterprises, encouraging sustainable development that benefits the community

2.5. Proposed Routes

Three alternative routes are proposed. The first, a "green route," follows the current path behind the quarry (an old livestock and quarry cart path), recovering part of the now-unused train track after the quarry tunnel became operational. From there, the route will follow the northern edge of the Serra Grossa, continuing along the Cruz de Piedra and Benimagrell paths. The second route starts from Villafranqueza, following the Orgegia road to Santa Faz. The third route follows the traditional path from the Monastery/Hermitage of Los Ángeles to the Santa Faz Monastery (

Figure 20).

Future reforestation efforts along the pilgrimage paths are anticipated to positively impact local biodiversity and habitat quality. By introducing native flora such as carob, olive, and almond trees, the project aims to improve soil stability and create enhanced habitats for local fauna. These restoration activities are expected to support ecological resilience while enriching the sensory experience for pilgrims, fostering an environment that reflects the region's historical landscape.

Each restoration route will involve three essential elements:

Intensive landscape recovery through reforestation with traditional and native species (carob, olive, almond, etc.).

Provision of supply points at strategic locations, utilizing temporary architecture installations that can be dismantled as needed.

A large arrival and gathering space near Santa Faz for pilgrims.

The paths would be established as year-round routes, offering a journey that evokes the traditional landscape of the Alicante huerta. The goal is to encourage pilgrims to travel on foot rather than by vehicle, immersing themselves in an environment that preserves remnants of the historical pilgrimage landscape. This route aims to revive and enhance the huerta paths, providing an alternative to the modern urban landscape.

To achieve this, it will be necessary to restore these paths and ensure they are passable along their entire length (for example, the Cruz de Piedra path is currently interrupted by the Orgegia ravine channel). Informational panels or QR codes would be installed to minimize invasive physical elements, offering information about the Pilgrimage, Santa Faz, huerta watchtowers, and historical irrigation systems. Recreational and rest areas will also be created to enhance the visitor experience.

2.6. Creating a Pilgrimage Leisure Zone around the Santa Faz District

The creation of a permanent, year-round leisure area for pilgrims around the Santa Faz district (a gathering space) between the Juncaret ravine channel and the Cruz de Piedra path is essential. The gathering space would be an open, expansive area appropriate for a human gathering on the scale of the pilgrimage. It would be accompanied by a restructuring of the Santa Faz urban layout, integrating both the areas behind the Monastery (toward National Highway 332) and the space on the opposite side, connected by a large elevated passageway with landscape-integrated design.

In general, the project seeks to enhance the tributary spaces of the pilgrimage through a recovery of the landscape’s memory. The project’s fundamental aim is the restoration of ancient paths and the development of alternative routes for the annual Santa Faz pilgrimage, allowing for year-round use and gradually reducing reliance on National Highway 332 as the sole event route.

Moreover, this project should aim to revalue Alicante’s culture and heritage (including huerta watchtowers, irrigation systems, etc.), promoting tourism, economic growth, and, consequently, local employment.

There should be a focus on promoting local culture and architecture, regional gastronomy, the “water routes,” and more. This would logically require changes to the urban planning of affected areas to ensure leisure spaces and transit routes. Similarly, a public Employment Promotion Project would be necessary to refurbish all old paths, landscaping, outdoor furniture, signage, and more.

The ultimate goal is to include the “paths of the Santa Faz” within the "Cultural Routes of the Council of Europe" program (

Figure 21).

A revitalized Santa Faz Pilgrimage pathway would significantly benefit the local economy by fostering opportunities for local businesses, artisans, and service providers connected to the pilgrimage. Small businesses, including regional food vendors, artisans, and accommodations, would see increased demand, aligning with sustainable tourism models. Additionally, the route’s enhancement promotes job creation in heritage preservation, sustainable tourism management, and event logistics, contributing to regional employment and economic stability.

2.7. The Santa Faz Pilgrimage Project and the SDGs

The proposed project for the Santa Faz Pilgrimage aligns with several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Nations 2030 Agenda.

Table 1 lists the relevant SDGs and the specific measures within those goals that the project addresses.

The proposed study to revitalize and enhance the historical paths of the Santa Faz pilgrimage aligns with several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), addressing specific measures related to sustainable cities, responsible production and consumption, climate action, life on land, peace, justice, and strong institutions, as well as partnerships for the goals.

2.8. Perceptions of Tour Guides and Adult Citizens on the Santa Faz Pilgrimage: A Qualitative Analysis of Its Cultural, Educational, and Sustainable Value

To explore the role of the Santa Faz Pilgrimage in promoting cultural heritage and its potential as a sustainable tourism resource, a qualitative survey was conducted, beginning with a group of local tour guides who attended a seminar we organized on the Santa Faz pilgrimage and its history at the Center for Tourism Development in Alicante, sponsored by the Generalitat Valenciana, in 2023. Twelve individuals completed the survey.

The open-ended questionnaire with multiple-choice questions was designed to capture the guides’ perspectives on topics such as the relic’s authenticity and historical significance, narratives surrounding the associated miracles, the role of historical figures like the Franciscans and the Borgias, and the management of controversies related to the relic’s authenticity. Additionally, questions assessed the guides’ interest in establishing permanent routes to support the educational, cultural, and sustainable development of Alicante (

Table 2).

The analysis of responses reveals several key themes, highlighting the guides’ appreciation of the Santa Faz as a cultural and tourism resource. First, most respondents emphasize the relic’s importance in distinguishing Alicante from other tourist destinations, underscoring its value beyond religion as a symbol of local identity. For many guides, the Santa Faz’s history and symbolism enhance visitors' interest, adding an emotional connection that enriches the tourist experience.

Another recurring theme is the neutral and respectful approach guides adopt in narrating the miracles associated with the Santa Faz. Respondents indicated that they maintain an impartial stance, presenting the miracles as part of Alicante’s culture and allowing visitors to interpret the events from their own beliefs. This inclusive approach is seen as an effective strategy to engage a diverse audience and to strengthen the relationship between cultural tourism and respect for diverse beliefs.

Guides also highlight the influence of historical figures like the Franciscans and the Borgias, noting that these characters add a "historical mystique" that piques tourists’ interest. Respondents suggest that connections with renowned figures, especially the Borgias, add value to tours and contextualize the Santa Faz’s local historical significance.

The mystery of the Santa Faz Camarín, as well as theories comparable to the Da Vinci Code, are viewed by guides as tools to captivate visitors. Respondents note that the Camarín’s associated mystery adds special appeal for those seeking unique cultural experiences, allowing guides to enrich their narratives without straying from historical facts.

Finally, and of particular interest in this study, the guides express support for creating permanent Santa Faz routes as a resource to foster Alicante’s sustainable development. Most respondents believe that a well-organized route with information points and rest areas would enable Alicante to diversify its tourism offerings beyond the summer months, contributing to the conservation and appreciation of its cultural heritage and educating both local and visiting populations (

Table 3).

In conclusion, the perceptions of tour guides indicate a strong recognition of the Santa Faz Pilgrimage’s educational and cultural value, which, when properly managed, could play a crucial role in promoting sustainable tourism in the region.

In this regard, and relevant to this publication, this analysis provides a comprehensive view of how local actors perceive and value this festivity, reinforcing the proposal to incorporate the Santa Faz as a key tool for preserving Alicante’s heritage and identity.

The same seminar was held for adults at the University of Alicante’s University Headquarters a few months later. Twenty-five attendees completed the online survey, answering the same questions as those presented to the tour guides (

Figure 22).

The qualitative analysis of responses from adult seminar participants on the Santa Faz reveals several themes that highlight perceptions of the relic’s cultural and historical value. First, participants emphasize the importance of the relic as an emblem of Alicante's cultural identity, noting that its journey to the city represents the role of faith and culture in local history. Many feel this distinctive element allows a deep connection with the region's tradition and historical heritage.

Another significant theme is the neutral and respectful approach to interpreting the miracles associated with the Santa Faz. Some participants appreciate how these stories contribute to community cohesion, while others reflect a skepticism that allows them to interpret the miracles as part of a historical context without compromising their own beliefs. This diverse approach strengthens the relationship between cultural tourism and respect for diverse beliefs.

Furthermore, historical figures such as the Franciscans and the Borgias are perceived as elements that add context and depth to the Santa Faz narrative. Participants observe that these historical characters contribute a “historical mystique” that enriches the appreciation of the site and offers a unique perspective on the Santa Faz Monastery.

Stories of mystery surrounding the Camarín also captivate participants, encouraging them to explore and uncover the secrets of this space. This inclination toward mystery underscores the Camarín’s ability to spark curiosity and interest in unique cultural experiences.

Finally, regarding controversies surrounding the authenticity of the Santa Faz, responses reflect an appreciation for its cultural symbolism beyond historical accuracy. For some, the controversy heightens their interest in learning more about this symbol, emphasizing its role as a significant resource in the education and preservation of Alicante's cultural heritage (

Table 4).

Both qualitative analyses, of the tour guides and the adult seminar participants on the Santa Faz, underscore the relic’s importance as a key cultural symbol for Alicante. Both groups view the Santa Faz as an element that goes beyond religion, contributing to local identity and connecting visitors with the region’s historical heritage. However, while the tour guides emphasize its potential as a distinctive resource that sets Alicante apart from other destinations, the seminar participants focus on its role in local faith and tradition, attributing a spiritual dimension that enriches understanding of the city’s history.

Both groups also agree on the importance of maintaining a neutral and respectful approach in interpreting the miracles associated with the Santa Faz. This inclusive approach allows listeners to interpret the stories from their own beliefs, fostering respect for diverse perspectives. Although there is this agreement, the tour guides adopt a strictly impartial stance to appeal to a diverse audience, while the seminar participants show divided opinions; some value these stories as community cohesion elements, while others take a skeptical view, seeing the miracles primarily as historical elements.

The influence of historical figures such as the Franciscans and the Borgia family is another prominent theme in both analyses. For both groups, these figures add a “mysticism” that enriches the Santa Faz narrative and provides cultural depth. However, while the guides see these figures as a tool to draw tourists’ attention through renowned historical references, the participants appreciate their contribution in terms of historical context, valuing the uniqueness these figures bring to the Santa Faz Monastery.

Regarding the mystery surrounding the Camarín of the Santa Faz, both guides and participants consider this aspect to add a unique appeal to the site. The guides use it as a narrative tool to maintain visitors’ interest, while the participants experience a personal curiosity, expressing a desire to explore this space and uncover its secrets.

Concerning the authenticity controversy, both groups acknowledge that its value as a cultural symbol does not depend on its historical accuracy. The guides approach authenticity from an objective perspective, allowing visitors to form their own opinions, while participants see the controversy as a feature that increases their interest in learning more about this symbol, considering it a characteristic that enhances its value as an educational and heritage resource.

In summary, both the tour guides and seminar participants share a deep appreciation of the Santa Faz as a cultural resource. Due to their professional and formative involvement, the guides highlight its role in tourism promotion and its ability to capture visitors’ interest, while the adult participants show a more personal connection, oriented towards its educational and cultural preservation value. This comparison highlights the multifunctional nature of the Santa Faz, which can be used for both tourism and the promotion of heritage education and conservation in Alicante.

In the following heatmap (Figure ___), the strengths of the relationship between key ideas about the Santa Faz and the two groups—Tour Guides and Seminar Participants—are represented. The intensity of each cell’s color indicates the level of connection, with both groups showing a strong alignment on most topics, though there is slight variation in the interpretation of miracles and the handling of authenticity (

Figure 23).

3. Discussion

In the field of cultural tourism, slow routes, particularly pedestrian and cycling paths, are considered valuable resources for sustainable, social, and economic development of territories [

51]. Cultural routes, as defined by the Council of Europe, broaden the concept of cultural heritage conservation and enhancement to a more extensive territorial perspective that integrates tangible and intangible heritage, natural and built heritage, into a cohesive whole. Within this framework, cultural routes, primarily used to rediscover the territory through the slow travel experience, require documentation and classification as a system of dispersed cultural heritage across the territory, utilizing innovative and effective tools.

In this regard, the SQISR method (Spatial Quality Index of Slow Routes) has been proposed as an approach that, at a territorial level, enables the analysis of spatial characteristics of slow routes through GIS-based mapping techniques, while also allowing for the comparison of alternative routes based on a set of heterogeneous indicators [

51]. This tool would be fundamental to the implementation of the proposed project.

Regarding significant examples exploring different aspects of pilgrimage routes and sacred sites, their sustainable management, and local community involvement, we can consider ethno-visual tourism, which utilizes visual media to explore the cultural heritage of a destination, generating economic benefits and promoting investment in cultural heritage conservation projects and infrastructure [

52], as exemplified in a case study in Adjara, Georgia. This approach emphasizes the importance of community involvement and responsible tourism practices for environmental sustainability. Another notable example is the Inanda Heritage Route in Durban, South Africa, developed for the 2010 FIFA World Cup [

53]. It examines tourist experiences, predominantly from international football fans, and assesses tourism sustainability with a focus on community participation and cultural heritage management, arguing that sustainable success in alternative tourism requires greater community involvement.

From another perspective, the interdependence between sustainable urban tourism and energy-efficient architecture is examined [

54], highlighting the importance of stakeholder engagement, regional cooperation, sustainable urban mobility, and social and environmental innovation for successful sustainable urban tourism, including environmentally acceptable waste management and natural habitat preservation.

Focusing on the management and conservation of pilgrimage routes and sacred sites, heritage management and conservation activities, local communities, and tourism development have been examined in the Kii World Heritage Site (WHS) following its designation [

55]. Findings indicate that WHS designation has strengthened local identity, increased local pride in culture and place of residence, and triggered a revitalization of local culture. Additionally, despite increased visitor numbers since the UNESCO inscription, negative tourism impacts appear minimal.

Furthermore, the concept of stakeholder participation has been explored in the management and conservation of Ireland’s sacred Croagh Patrick mountain [

56], examining the factors that facilitate and hinder the effectiveness of this new partnership in promoting sustainable management of this natural sacred site, which simultaneously serves as a pilgrimage and tourism location.

Studies have also examined the development of pilgrimage paths and faith-based tourism practitioners in more than ten countries [

57], analyzing circular pilgrimages in the Netherlands, "anti-pilgrimages" in the United Kingdom, and the revitalization of ancient trails like the Old Way to Canterbury, the Kumano Kodo in Japan, and new routes such as the Sufi Trail in Turkey.

As cultural heritage sites face increasing threats from urban expansion and modernization, sustainable approaches to tourism provide a pathway for preserving not only physical heritage but the intangible elements that imbue spaces with significance. This study positions the Santa Faz Pilgrimage within this global conversation, proposing a model of heritage tourism that both conserves Alicante’s cultural identity and aligns with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

This project draws upon frameworks within intangible cultural heritage preservation and sustainable tourism, particularly those which integrate environmental stewardship with the cultural enrichment of participants. In light of this, slow tourism models have proven especially relevant for pilgrimage paths, given their focus on low-impact travel and deeper cultural engagement. The Council of Europe’s Cultural Routes initiative exemplifies this approach by promoting routes that blend cultural appreciation with environmental sustainability and local economic support .

Recent literature highlights a number of successful sustainable pilgrimage models across Europe, such as the Kumano Kodo in Japan and the Inanda Heritage Route in South Africa, where sustainable tourism frameworks are employed to balance cultural preservation with visitor management. These models emphasize environmental sustainability, community involvement, and heritage conservation, which are essential components of the Santa Faz project. Integrating similar practices can not only protect but also enhance the pilgrimage’s cultural and educational value, ensuring its relevance and accessibility for future generations.

Comparative studies on European pilgrimage routes, such as Spain’s Camino de Santiago, the Kumano Kodo in Japan, and Ireland’s Croagh Patrick, highlight the diverse approaches in managing culturally significant paths. Each route presents unique practices and challenges in integrating sustainable tourism models with traditional pilgrimage experiences. Similar to these, the Santa Faz pilgrimage pathway exemplifies Alicante’s heritage through a sustainable, community-centered framework, fostering both ecological and socio-cultural resilience. Unlike the Camino de Santiago’s expansive infrastructure, which accommodates international pilgrims year-round, the Santa Faz pilgrimage remains more localized, preserving an intimate community connection. This project’s comparative approach could contribute valuable insights into how smaller-scale pilgrimages like Santa Faz could be promoted within the European network of cultural routes while retaining their local identity and traditions. Aligning these practices with sustainable tourism, as well as European cultural heritage frameworks, reinforces the pilgrimage's role not just as a religious journey but as a catalyst for economic growth and cultural preservation within Alicante’s community.

Given the findings, this study presents essential implications for regional tourism policies aimed at integrating sustainable practices within heritage tourism. By prioritizing environmental resilience and community involvement, local and regional authorities can draw from the Santa Faz Pilgrimage framework to enhance not only the conservation of culturally significant paths but also the socioeconomic welfare of host communities. Such policies might include zoning modifications for historical routes, incentives for heritage-friendly businesses, and broader adoption of sustainable infrastructure within tourism development zones. In doing so, Alicante can serve as a model for other municipalities seeking to balance cultural preservation with sustainable growth.

To deepen the understanding of the Santa Faz Pilgrimage’s influence, future research could focus on longitudinal studies examining the socio-economic impact of the pilgrimage on Alicante’s local economy, assessing how job creation, community pride, and small business support evolve over time. Additionally, it would be beneficial to conduct environmental impact assessments on the reforestation and sustainability efforts associated with the pilgrimage paths, documenting changes in biodiversity, habitat quality, and visitor satisfaction. Expanding this work to include comparisons with other European pilgrimages, like those managed under sustainable tourism frameworks, would provide insights into best practices for balancing visitor engagement with ecological preservation.

4. Conclusion

This study offers a multidimensional approach to cultural heritage management by focusing on the revitalization of intangible heritage in Alicante through the preservation and enhancement of the Santa Faz pilgrimage routes. By proposing a sustainable model that integrates reforestation, community involvement, and socio-economic benefits, the study demonstrates how traditional pilgrimage practices can align with modern principles of sustainable tourism and environmental stewardship. These initiatives not only contribute to local cultural identity but also support Alicante's broader socio-economic goals, fostering economic growth through tourism, creating employment opportunities, and strengthening community pride and cohesion.

This study presents a multifaceted contribution to the field of cultural heritage management by emphasizing the Santa Faz pilgrimage as a unique intangible heritage. Through the proposed interventions—such as reforesting historical routes and creating environmentally sustainable infrastructures—the study illustrates a balanced model for heritage preservation that simultaneously supports local socio-economic goals. These strategies provide practical insights into how pilgrimage sites can be conserved and developed in harmony with community needs and environmental goals, addressing broader questions of sustainability in heritage tourism.

The restoration of the Santa Faz pilgrimage paths is essential both for the conservation of Alicante’s cultural heritage and for promoting sustainable territorial development. Modifying the current urban plan emerges as a priority recommendation, alongside fostering employment projects focused on heritage and tourism management in the region. This approach enables the revitalization of the pilgrimage paths to be carried out in a comprehensive manner, addressing the cultural, environmental, and socioeconomic components essential for effective and sustainable management of these sacred spaces.

Furthermore, community involvement is a crucial element in the development of such projects, especially given the spiritual and religious dimensions that characterize the pilgrimage. Qualitative studies, such as the one conducted in this research, provide valuable insights to guide participatory processes that ensure a community-centered implementation. These efforts should be aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the 2030 Agenda, ensuring that interventions adhere to principles of environmental and social sustainability, thereby providing a solid foundation for the long-term conservation and enhancement of this cultural heritage.

This study underscores the alignment of the Santa Faz pilgrimage revitalization project with global Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) and SDG 15 (Life on Land). By advocating for reforestation and the development of sustainable tourism infrastructure along the pilgrimage routes, the project supports the conservation of natural ecosystems while enhancing urban-rural connectivity. These efforts not only aim to preserve Alicante’s intangible cultural heritage but also strengthen the community's commitment to sustainable development, fostering both environmental stewardship and cultural resilience.

Future initiatives aimed at sustaining the Santa Faz pilgrimage must continue to prioritize community engagement, ensuring that local residents are active participants in both planning and implementation. Establishing frameworks that invite community input into tourism projects related to the pilgrimage will not only reinforce cultural pride but also enhance the sustainability of these initiatives. This approach underscores the importance of community-centered cultural tourism, where local voices and traditions are central to preserving Alicante’s intangible heritage for generations to come.

Figure 1.

Physical framework through which the Santa Faz Pilgrimage (Alicante) takes place, with the monastery located near Monte del Pino de Alberola.

Figure 1.

Physical framework through which the Santa Faz Pilgrimage (Alicante) takes place, with the monastery located near Monte del Pino de Alberola.

Figure 2.

Ancient weir of Mutxamel, possibly of Muslim origin but significantly transformed in the 16th century. Source: Private collection.

Figure 2.

Ancient weir of Mutxamel, possibly of Muslim origin but significantly transformed in the 16th century. Source: Private collection.

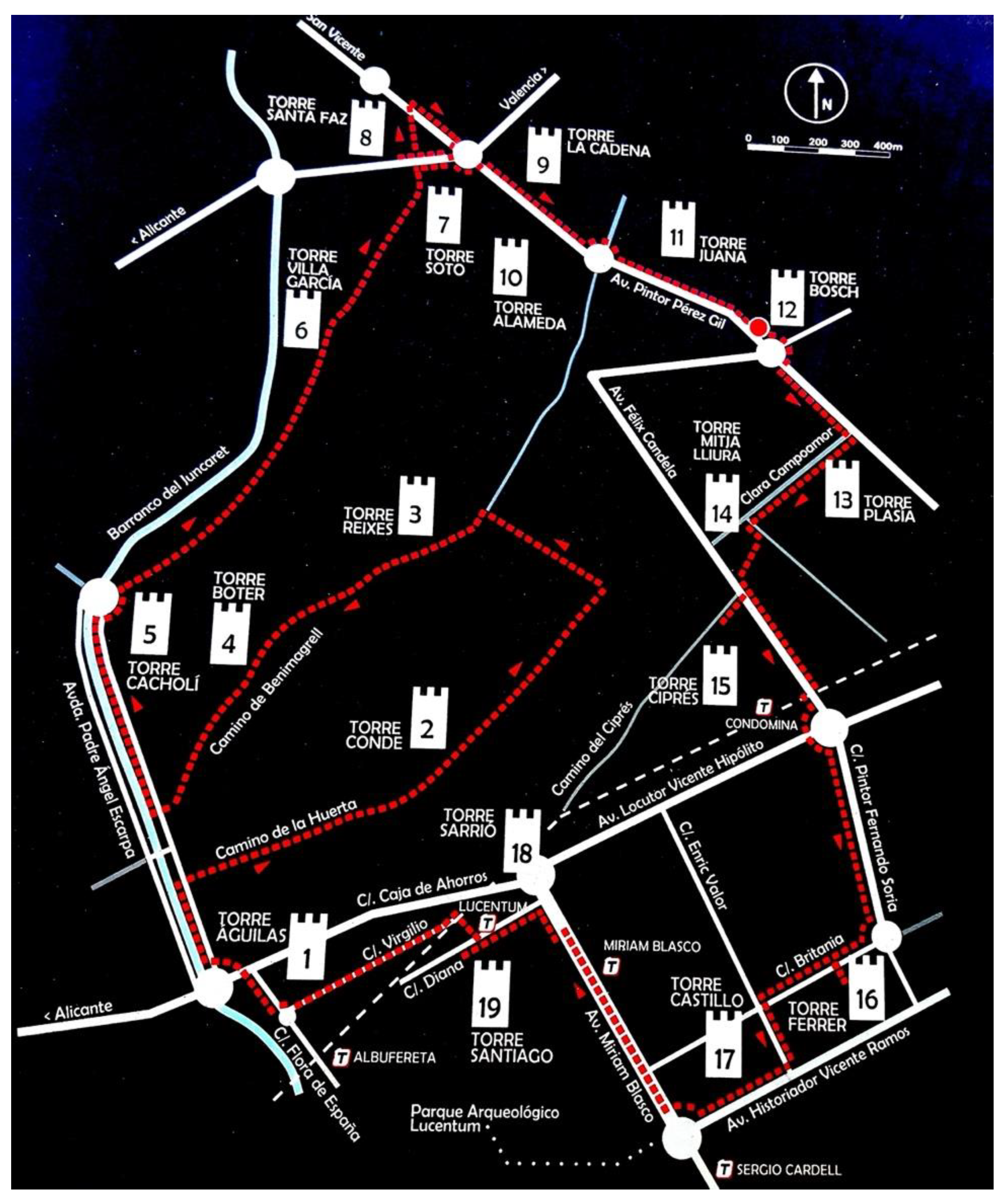

Figure 3.

Santa Faz road network in the Huerta de Alicante. Road Network: 1. Villafranqueza Path. 2. Tángel Path. 3. Old Valencia Path. 4. Villafranqueza to the Sea Path. 5. Santa Faz Path. 6. Mutxamel Path. 7. Stone Cross Path. 8. Benimagrell Path. 9. Huerta Path. 10. San Juan Beach Path. 11. Albufereta Path. 12. Los Ángeles to Creu de Fusta Path. Sources: VARELA (1984). Official Cartography scale 1:10,000.

Figure 3.

Santa Faz road network in the Huerta de Alicante. Road Network: 1. Villafranqueza Path. 2. Tángel Path. 3. Old Valencia Path. 4. Villafranqueza to the Sea Path. 5. Santa Faz Path. 6. Mutxamel Path. 7. Stone Cross Path. 8. Benimagrell Path. 9. Huerta Path. 10. San Juan Beach Path. 11. Albufereta Path. 12. Los Ángeles to Creu de Fusta Path. Sources: VARELA (1984). Official Cartography scale 1:10,000.

Figure 4.

Irrigation map of the Alicante Reservoir (19th century). Source: Private collection.

Figure 4.

Irrigation map of the Alicante Reservoir (19th century). Source: Private collection.

Figure 5.

Photograph of the Torre del Ciprés and adjacent Hermitage, built during the 16th-17th centuries. Source: Private collection.

Figure 5.

Photograph of the Torre del Ciprés and adjacent Hermitage, built during the 16th-17th centuries. Source: Private collection.

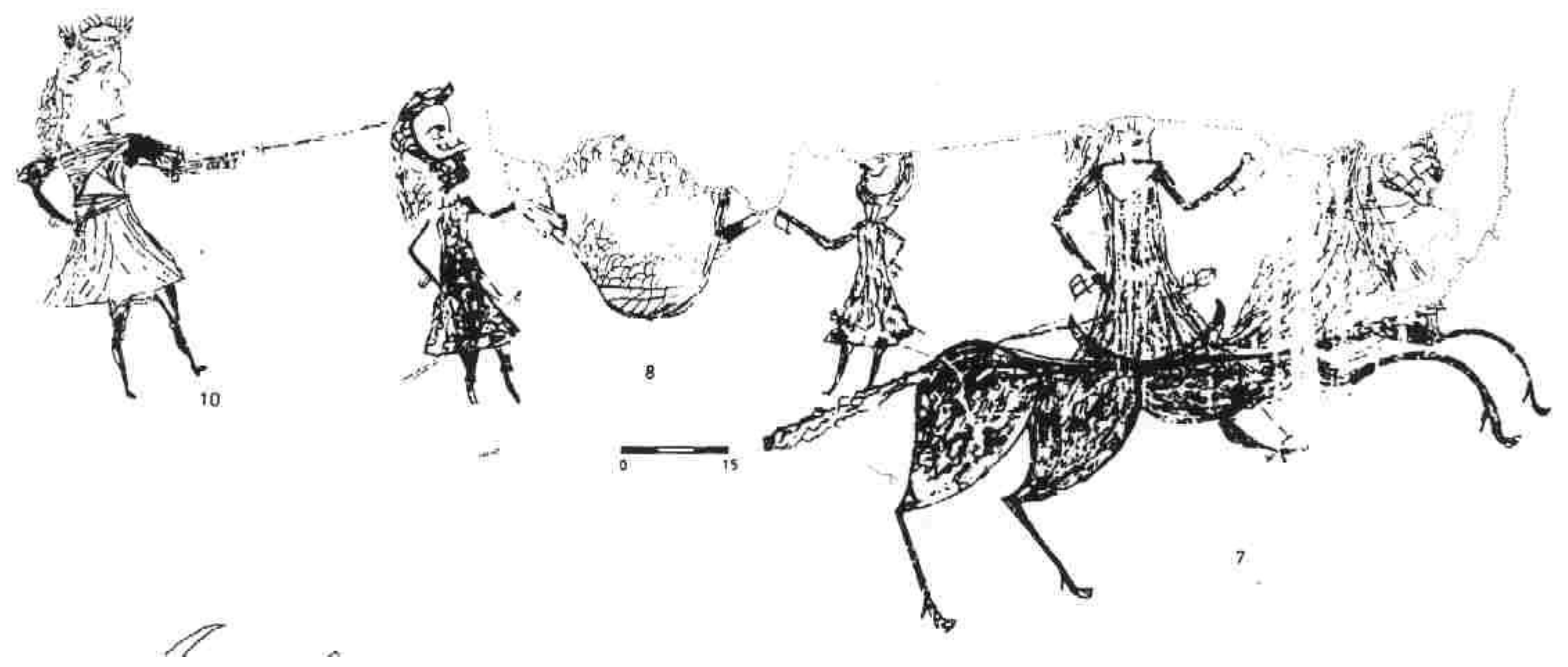

Figure 6.

17th-century graffiti preserved in the Casa Capiscol in the Huerta of Alicante, depicting members of a Company of Knights recovering loot captured by a group of Berbers.

Figure 6.

17th-century graffiti preserved in the Casa Capiscol in the Huerta of Alicante, depicting members of a Company of Knights recovering loot captured by a group of Berbers.

Figure 7.

Map showing the location of towers in the Huerta of Alicante. Source: Private collection.

Figure 7.

Map showing the location of towers in the Huerta of Alicante. Source: Private collection.

Figure 8.

Photograph of paths, dry stone walls, vegetation, etc., in the Huerta of Alicante. Source: Plinthus Collection.

Figure 8.

Photograph of paths, dry stone walls, vegetation, etc., in the Huerta of Alicante. Source: Plinthus Collection.

Figure 9.

The Holy Face, held by two angels, painted by Juan Sánchez Cotán (1620–1625), from the Monastery of La Cartuja in Granada.

Figure 9.

The Holy Face, held by two angels, painted by Juan Sánchez Cotán (1620–1625), from the Monastery of La Cartuja in Granada.

Figure 10.

Wooden panel from the old altarpiece of the Church of the Santa Faz in the Monastery of the same name (15th century), depicting this first miracle. Source: Photograph by the authors.

Figure 10.

Wooden panel from the old altarpiece of the Church of the Santa Faz in the Monastery of the same name (15th century), depicting this first miracle. Source: Photograph by the authors.

Figure 11.

Detail of one of the canvases by the painter Conchillos in the Camarín de la Santa Faz (17th century), depicting the second miracle. Source: Photograph by the authors.

Figure 11.

Detail of one of the canvases by the painter Conchillos in the Camarín de la Santa Faz (17th century), depicting the second miracle. Source: Photograph by the authors.

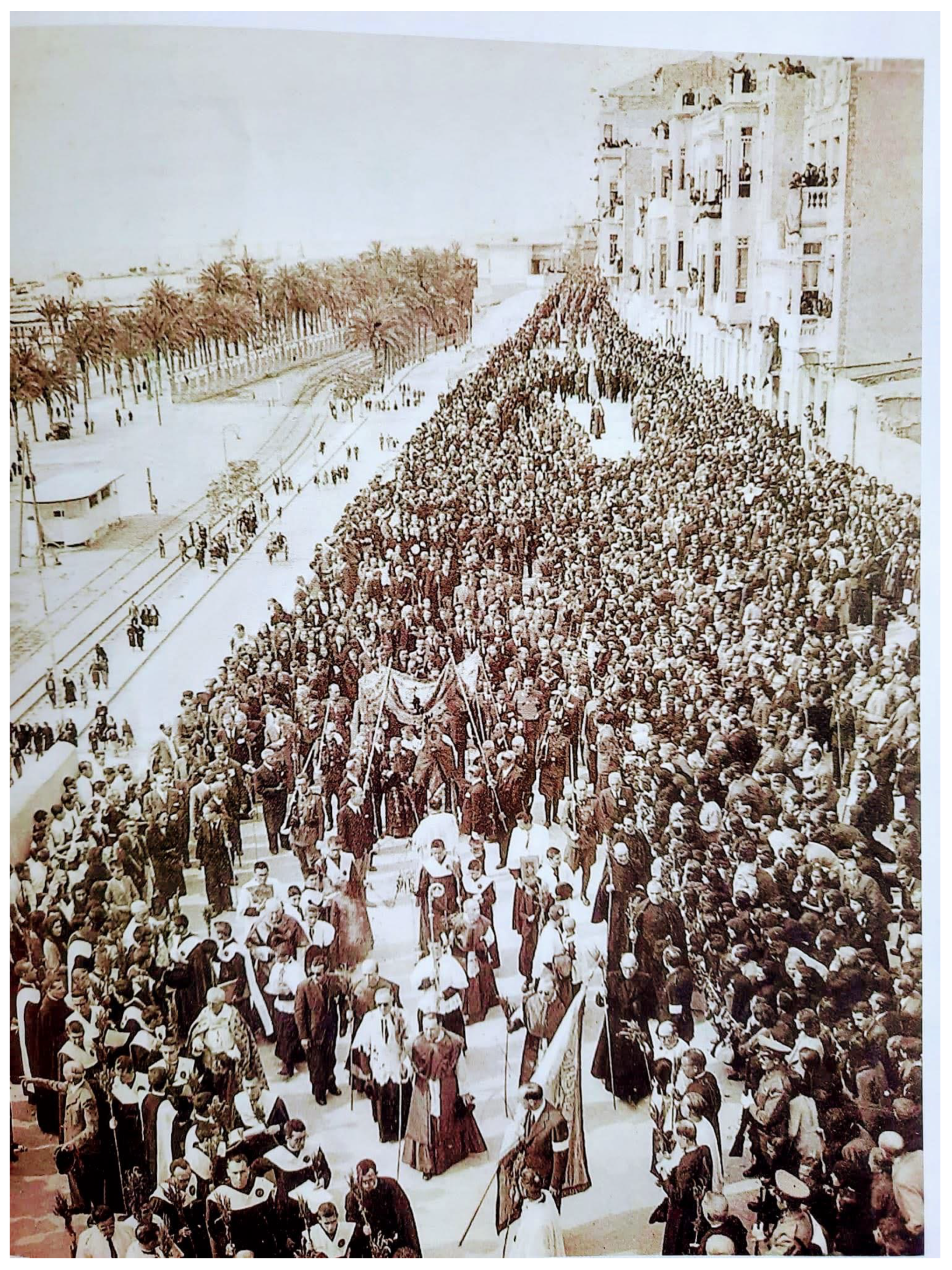

Figure 12.

Photograph of the Pilgrimage passing through the current Avenida de Denia (19th century). Source: Seguí Collection. Department of Memory of Alicante, Alicante City Council.

Figure 12.

Photograph of the Pilgrimage passing through the current Avenida de Denia (19th century). Source: Seguí Collection. Department of Memory of Alicante, Alicante City Council.

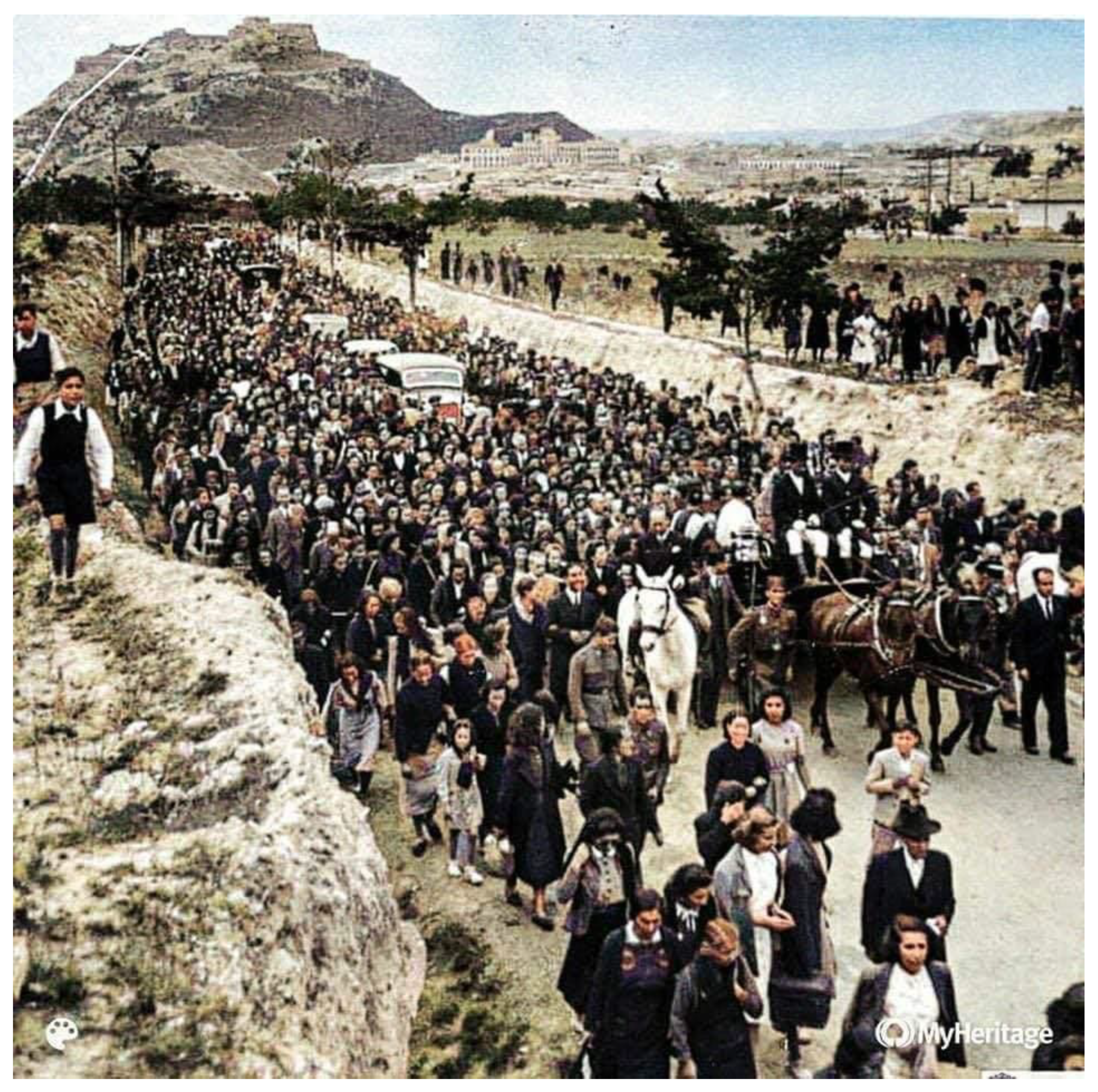

Figure 13.

Photograph of the Pilgrimage passing through the current Avenida de Denia (19th century). Source: MyHeritage.

Figure 13.

Photograph of the Pilgrimage passing through the current Avenida de Denia (19th century). Source: MyHeritage.

Figure 14.

Photograph of the Pilgrimage passing through Raval Roig (1840s). Source: Alicante Municipal Archive.

Figure 14.

Photograph of the Pilgrimage passing through Raval Roig (1840s). Source: Alicante Municipal Archive.

Figure 15.

Photograph of the Cruz de Fusta on the current Avenida de Denia (1840s). Source: Alicante Municipal Archive.

Figure 15.

Photograph of the Cruz de Fusta on the current Avenida de Denia (1840s). Source: Alicante Municipal Archive.

Figure 16.

Photograph of the Pilgrimage passing through the current Jovellanos Street (19th century). Source: Seguí Collection. Department of Memory of Alicante, Alicante City Council.

Figure 16.

Photograph of the Pilgrimage passing through the current Jovellanos Street (19th century). Source: Seguí Collection. Department of Memory of Alicante, Alicante City Council.

Figure 17.

Photograph of the Pilgrimage passing through the current Avenida de Denia, showing the Knight Custodians on horseback (19th century). Source: Seguí Collection. Department of Memory of Alicante, Alicante City Council.

Figure 17.

Photograph of the Pilgrimage passing through the current Avenida de Denia, showing the Knight Custodians on horseback (19th century). Source: Seguí Collection. Department of Memory of Alicante, Alicante City Council.

Figure 18.

Photograph of the sale of water jugs, pitchers, and other ceramic items in the plaza of the Monastery of the Santa Faz (1840s). Source: Alicante Municipal Archive.

Figure 18.

Photograph of the sale of water jugs, pitchers, and other ceramic items in the plaza of the Monastery of the Santa Faz (1840s). Source: Alicante Municipal Archive.

Figure 19.

Recreation of the Santa Faz Pilgrimage based on photographs. Source: authors.

Figure 19.

Recreation of the Santa Faz Pilgrimage based on photographs. Source: authors.

Figure 20.

Centuries-Old Paths of the Santa Faz. Source: Belén Alejandro, Designer.

Figure 20.

Centuries-Old Paths of the Santa Faz. Source: Belén Alejandro, Designer.

Figure 21.

Project: The Paths of the Holy Face.

Figure 21.

Project: The Paths of the Holy Face.

Figure 22.

Audience attending our seminar on the Santa Faz. Source: authors.

Figure 22.

Audience attending our seminar on the Santa Faz. Source: authors.

Figure 23.

Heatmap showing the strengths of the relationship between key ideas about the Santa Faz and the two surveyed groups. Own elaboration.

Figure 23.

Heatmap showing the strengths of the relationship between key ideas about the Santa Faz and the two surveyed groups. Own elaboration.

Table 1.

SDGs related to the proposal and proposed measures.

Table 1.

SDGs related to the proposal and proposed measures.

| SDG |

Proposed Measure |

| SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities |

The study examines the impact of urban development on traditional pilgrimage routes and proposes modifications to the current urban plan to revitalize the historical paths of the Santa Faz. |

| SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production |

The study proposes the creation of sustainable tourism infrastructure along alternative pilgrimage routes, as well as reforestation with local species to promote more sustainable tourism. |

| SDG 13: Climate Action |

The study recommends reforesting the pilgrimage routes with native species as part of a strategy for climate change adaptation and mitigation. |

| SDG 15: Life on Land |

The study proposes reforesting the pilgrimage routes with local species to contribute to the conservation of terrestrial ecosystems and biodiversity. |

| SDG 16: Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions |

The study emphasizes the importance of ongoing research and interdisciplinary collaboration to ensure the long-term preservation and enhancement of pilgrimage spaces and sacred sites. |

| SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals |

The study highlights the need for collaboration and cooperation among different stakeholders, including local institutions, the community, and experts, to promote cultural heritage conservation and sustainable development in Alicante. |

Table 2.

Questionnaire Questions for the Qualitative Analysis on the Santa Faz and Its Pilgrimage.

Table 2.

Questionnaire Questions for the Qualitative Analysis on the Santa Faz and Its Pilgrimage.

| |

Survey Questions |

| 1 |

How do you believe the history and cultural significance of the Santa Faz relic influence the visitor experience at the Santa Faz Monastery in Alicante? |

| 2 |

From your perspective as a tour guide, how would you approach narrating the "miracles" associated with the Santa Faz to engage a diverse audience while respecting everyone’s beliefs? |

| 3 |

Considering the role of the Franciscans and their connection to the Borgias, how do you think these historical elements add value to the narrative of the Santa Faz Monastery for visitors? |

| 4 |

When explaining the history of the Santa Faz Camarín, how would you use the mystery and controversy surrounding the "new Da Vinci Code" (the affiliation of several 17th-century artists with the Alumbrados sect) to capture tourists’ attention without deviating from historical facts? |

| 5 |

Given doubts about the authenticity of the Santa Faz and historical crises, how would you handle tourist inquiries about these controversies to provide an informative and balanced experience? |

| 6 |

To what extent has your knowledge of the Santa Faz deepened your appreciation for Alicante’s history? |

| 7 |

Would you support the idea of permanently establishing the Santa Faz Paths throughout the year, with routes, information points, and rest areas as an educational, cultural, and tourist resource? |

Table 3.

Highlights from Tour Guide Responses.

Table 3.

Highlights from Tour Guide Responses.

| Concept or Key Idea |

Description |

| Cultural and historical importance of the relic |

Guides view the relic as adding distinctive value to Alicante, both religiously and culturally, promoting local identity. |

| Neutrality and respect in interpreting miracles |

A respectful approach is emphasized, maintaining a neutral stance on the miracles and allowing tourists a personal interpretation. |

| Impact of the Franciscans and the Borgias in the narrative |

The Franciscans and Borgias add a "historical mystique" that heightens visitor interest and enriches the Santa Faz story. |

| Leveraging the Camarín mystery |

The Camarín mystery is strategically used to capture tourists’ attention without deviating from historical facts. |

| Professional handling of authenticity controversies |

Guides prefer addressing questions about the Santa Faz’s authenticity from an objective, informative perspective, avoiding conflict. |

| Support for permanent routes for sustainable tourism |

There is consensus on the need for permanent routes that, beyond education, contribute to Alicante’s sustainable tourism. |

Table 4.

Key Questions and Representative Responses from the Santa Faz Seminar.

Table 4.

Key Questions and Representative Responses from the Santa Faz Seminar.

| Key Question |

Representative Response |

| How does the story of the Santa Faz relic make you feel, and how do you think its journey to Alicante reflects the importance of faith and culture in the city’s history? |

The relic represents a fundamental component of Alicante’s cultural identity, reflecting the importance of faith and culture in local history. |

| When learning about the "miracles" associated with the Santa Faz, what thoughts or emotions arise regarding how these ancient stories continue to influence modern communities? |

The miracles and legends contribute to community cohesion; some participants believe these beliefs remain significant in today’s society. |

| How do you think the influence of the Franciscans and the connection with the Borgias have shaped the history and perception of the Santa Faz Monastery among visitors and locals? |

The influence of the Franciscans and the Borgias adds context and depth, enhancing the historical and cultural value of the Santa Faz. |

| With the mystery surrounding the Camarín of the Santa Faz, do you feel more intrigued to visit and discover the secrets it might hold? |

The mysteries surrounding the Camarín spark curiosity, encouraging participants to explore and discover its secrets. |

| Knowing that the Santa Faz has been the subject of controversy and scrutiny, how does this affect your interest in learning more about this religious and cultural symbol? |