Submitted:

30 October 2024

Posted:

01 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Plant Materials

2.2. DNA Extraction, Genotyping by Sequencing (GBS), and SNP Calling

2.3. Population Structure

2.4. Genetic Diversity

3. Results

3.1. Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Diversity

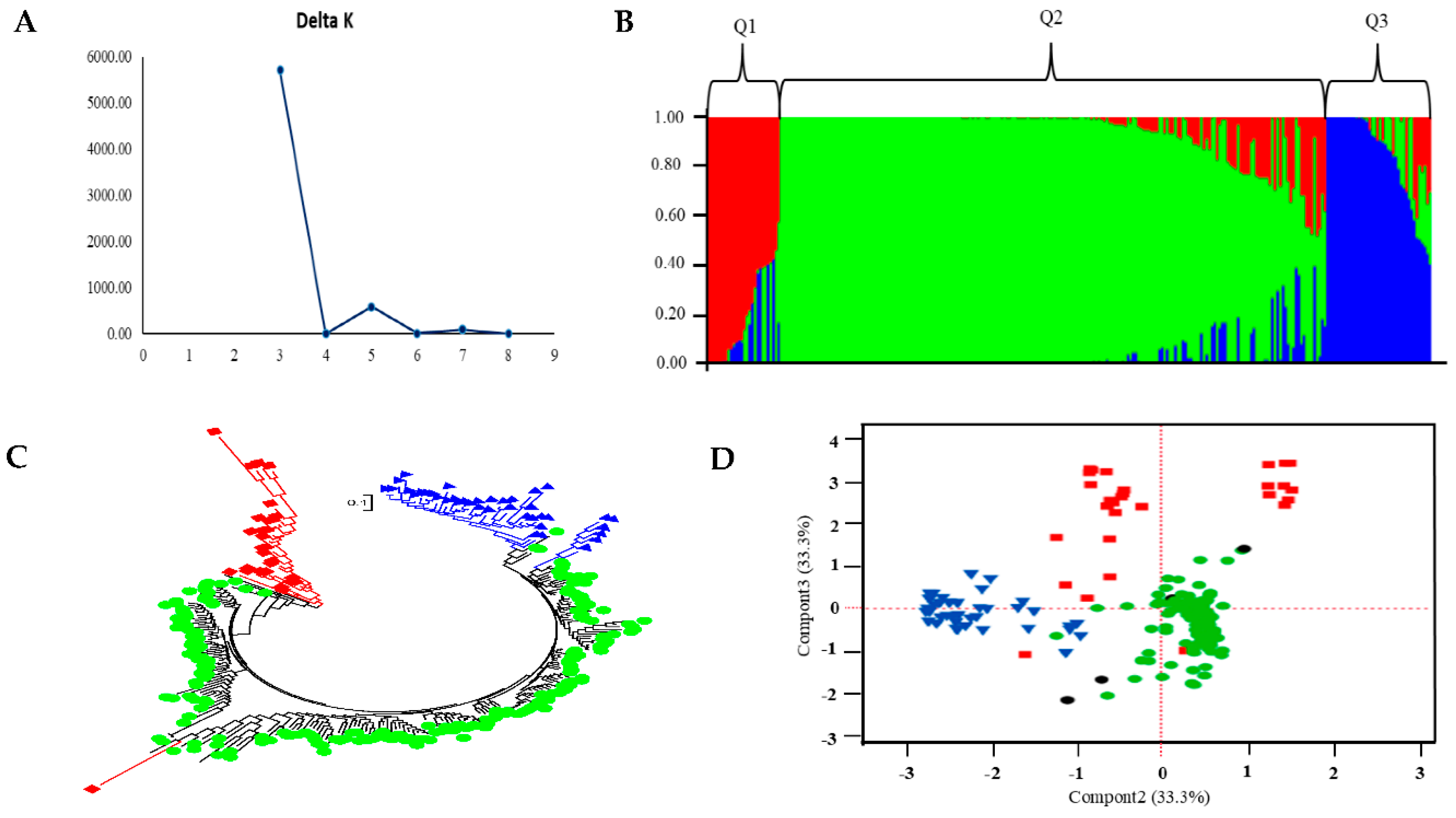

3.2. Population Structure

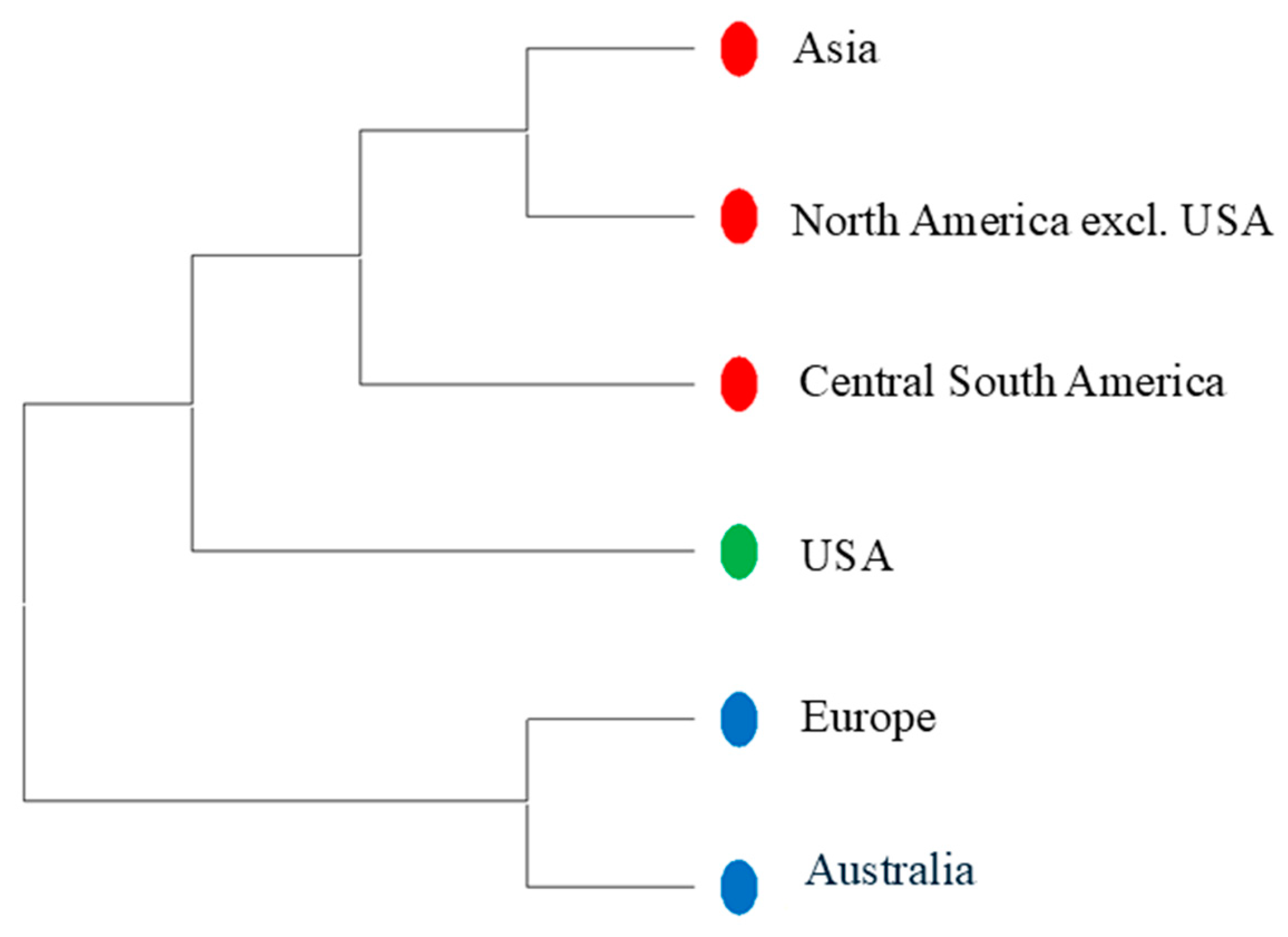

3.3. The Accessions from Different Geographic Origins

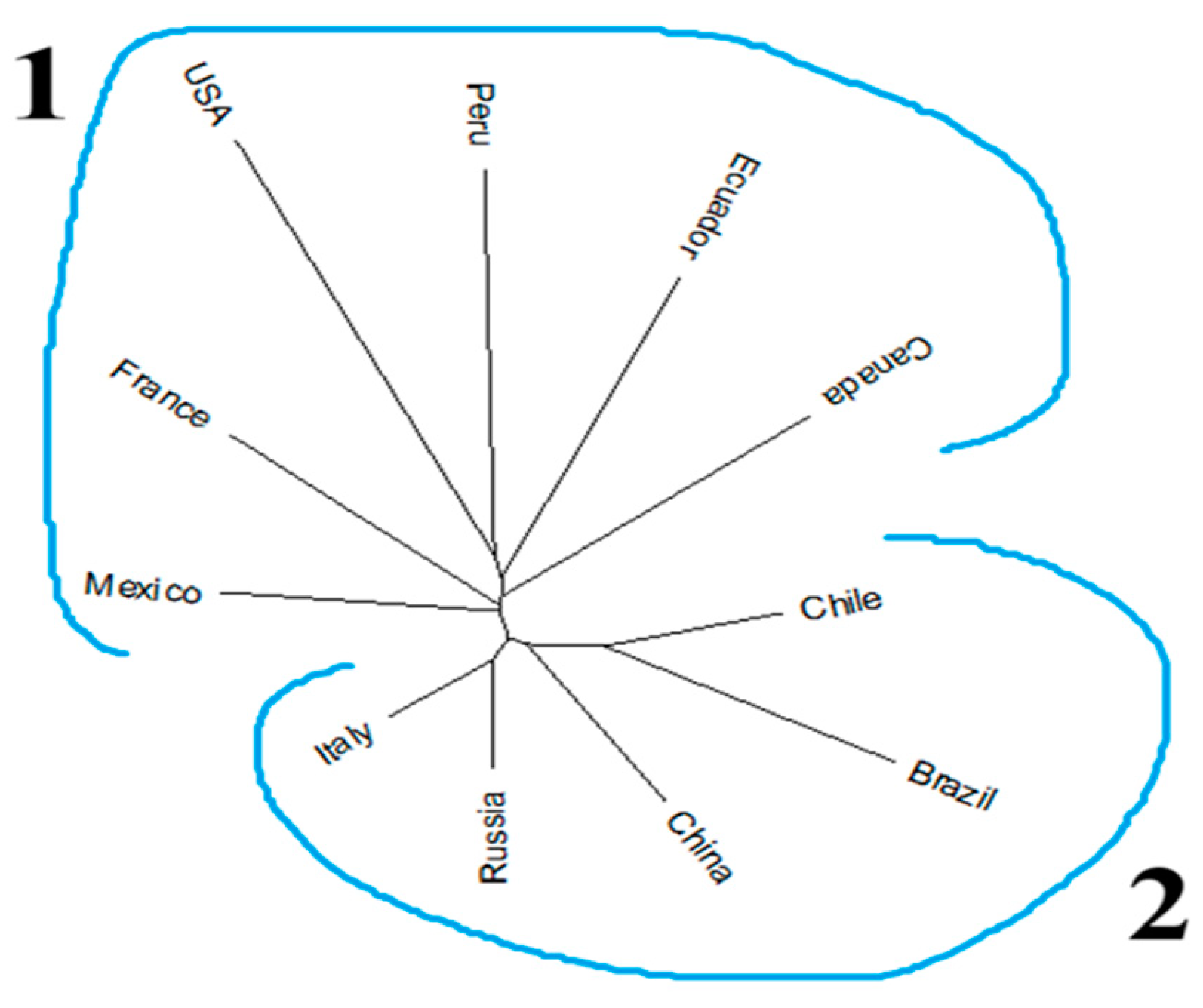

3.4. Phylogeny of the Accessions Across Diverse Countries

4. Discussion

4.1. The Profile of SNPs

4.2. Population Structure and Genetic Diversity

4.3. Geographic Influence

4.4. The Tomato Accessions from Diverse Countries

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adisa, I.O.; Rawat, S.; Pullagurala, V.L.R.; Dimkpa, C.O.; Elmer, W.H.; White, J.C.; Hernandez-Viezcas, J.A.; Peralta-Videa, J.R.; Gardea-Torresdey, J.L. Nutritional Status of Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum) Fruit Grown in Fusarium-Infested Soil: Impact of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles. J Agric Food Chem 2020, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadhilah, A.N.; Farid, M.; Ridwan, I.; Anshori, M.F.; Yassi, A. GENETIC PARAMETERS AND SELECTION INDEX OF HIGH-YIELDING TOMATO F2 POPULATIONS. SABRAO J Breed Genet 2022, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, A.B.C.; Maia, M.M.; Mendoza-Cortez, J.W.; Rodrigues, M.A.; Nowaki, R.H.D. Growing Seasons and Fractional Fertilization for Arugula. Comunicata Scientiae 2014, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Rick, C.; Chetelat, R. Utilization of Related Wild Species for Tomato Improvement. In Proceedings of the I International Symposium on Solanacea for Fresh Market 412; 1995; pp. 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Alstad, D.N.; Hotchkiss, S.C.; Corbin, K.W. Gene Flow Estimates Implicate Selection as a Cause of Scale Insect Population Structure. Evol Ecol 1991, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunyawat, U.; Stephan, W.; Städler, T. Using Multilocus Sequence Data to Assess Population Structure, Natural Selection, and Linkage Disequilibrium in Wild Tomatoes. Mol Biol Evol 2007, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradburd, G.S.; Coop, G.M.; Ralph, P.L. Inferring Continuous and Discrete Population Genetic Structure across Space. Genetics 2018, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, J.A. The Origin of the Cultivated Tomato. Econ Bot 1948, 2, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mccue, G.A. The History of the Use of the Tomato: An Annotated Bibliography. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 1952, 39, 289–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, S.C.; Robbins, M.D.; Van Deynze, A.; Michel, A.P.; Francis, D.M. Population Structure and Genetic Differentiation Associated with Breeding History and Selection in Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum L.). Heredity (Edinb) 2011, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanksley, S.D.; Mccouch, S.R. Seed Banks and Molecular Maps: Unlocking Genetic Potential from the Wild. Science (1979) 1997, 277, 1063–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulus, D. Genetic Diversity for Breeding Tomato. In Cash Crops: Genetic Diversity, Erosion, Conservation and Utilization; 2022; pp. 505–521.

- Sim, S.C.; van Deynze, A.; Stoffel, K.; Douches, D.S.; Zarka, D.; Ganal, M.W.; Chetelat, R.T.; Hutton, S.F.; Scott, J.W.; Gardner, R.G.; et al. High-Density SNP Genotyping of Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum L.) Reveals Patterns of Genetic Variation Due to Breeding. PLoS One 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labate, J.A.; Sheffer, S.M.; Balch, T.; Robertson, L.D. Diversity and Population Structure in a Geographic Sample of Tomato Accessions. Crop Sci 2011, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto Feliner, G.; Casacuberta, J.; Wendel, J.F. Genomics of Evolutionary Novelty in Hybrids and Polyploids. Front Genet 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, J.K.; Yerasu, S.R.; Rai, N.; Singh, D.P.; Singh, A.K.; Karkute, S.G.; Singh, P.M.; Behera, T.K. Progress in Marker-Assisted Selection to Genomics-Assisted Breeding in Tomato. CRC Crit Rev Plant Sci 2022, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulus, D. Genetic Resources and Selected Conservation Methods of Tomato. Journal of Applied Botany and Food Quality 2018, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Lindhout, P. Domestication and Breeding of Tomatoes: What Have We Gained and What Can We Gain in the Future? Ann Bot 2007, 100, 1085–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Zhu, G.; Zhang, J.; Xu, X.; Yu, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Lun, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, X. Genomic Analyses Provide Insights into the History of Tomato Breeding. Nat Genet 2014, 46, 1220–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshire, R.J.; Glaubitz, J.C.; Sun, Q.; Poland, J.A.; Kawamoto, K.; Buckler, E.S.; Mitchell, S.E. A Robust, Simple Genotyping-by-Sequencing (GBS) Approach for High Diversity Species. PLoS One 2011, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaubitz, J.C.; Casstevens, T.M.; Lu, F.; Harriman, J.; Elshire, R.J.; Sun, Q.; Buckler, E.S. TASSEL-GBS: A High Capacity Genotyping by Sequencing Analysis Pipeline. PLoS One 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochette, N.C.; Rivera-Colón, A.G.; Catchen, J.M. Stacks 2: Analytical Methods for Paired-End Sequencing Improve RADseq-Based Population Genomics. Mol Ecol 2019, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, J.K.; Stephens, M.; Donnelly, P. Inference of Population Structure Using Multilocus Genotype Data. Genetics 2000, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, J.; Qi, J.; Shi, Q.; Shen, D.; Zhang, S.; Shao, G.; Li, H.; Sun, Z.; Weng, Y.; Shang, Y.; et al. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Cucumber (Cucumis Sativus L.). PLoS One 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evanno, G.; Regnaut, S.; Goudet, J. Detecting the Number of Clusters of Individuals Using the Software STRUCTURE: A Simulation Study. Mol Ecol 2005, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Earl, D.A.; vonHoldt, B.M. STRUCTURE HARVESTER: A Website and Program for Visualizing STRUCTURE Output and Implementing the Evanno Method. Conserv Genet Resour 2012, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Muse, S. V. PowerMaker: An Integrated Analysis Environment for Genetic Maker Analysis. Bioinformatics 2005, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalli-Sforza, L.L.; Edwards, A.W. Phylogenetic Analysis. Models and Estimation Procedures. Am J Hum Genet 1967, 19, 233–257. [Google Scholar]

- Excoffier, L.; Lischer, H.E.L. Arlequin Suite Ver 3.5: A New Series of Programs to Perform Population Genetics Analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol Ecol Resour 2010, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitou, N.; Nei, M. The Neighbor-Joining Method: A New Method for Reconstructing Phylogenetic Trees. Mol Biol Evol 1987, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura Koichiro; Glen Stecher; Kumar Sudhir Tamura 2021. Mol Biol Evol 2021.

- Bai, Y.; Lindhout, P. Domestication and Breeding of Tomatoes: What Have We Gained and What Can We Gain in the Future? Ann Bot 2007, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Servia, J.L.; Vera-Guzmán, A.M.; Linares-Menéndez, L.R.; Carrillo-Rodríguez, J.C.; Aquino-Bolaños, E.N. Agromorphological Traits and Mineral Content in Tomato Accessions from El Salvador, Central America. Agronomy 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, J.K.; Yerasu, S.R.; Rai, N.; Singh, D.P.; Singh, A.K.; Karkute, S.G.; Singh, P.M.; Behera, T.K. Progress in Marker-Assisted Selection to Genomics-Assisted Breeding in Tomato. CRC Crit Rev Plant Sci 2022, 41, 321–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Poysa, V.; Yu, K. Development and Characterization of Simple Sequence Repeat (SSR) Markers and Their Use in Determining Relationships among Lycopersicon Esculentum Cultivars. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 2003, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanca, J.; Montero-Pau, J.; Sauvage, C.; Bauchet, G.; Illa, E.; Díez, M.J.; Francis, D.; Causse, M.; van der Knaap, E.; Cañizares, J. Genomic Variation in Tomato, from Wild Ancestors to Contemporary Breeding Accessions. BMC Genomics 2015, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrado, G.; Rao, R. Towards the Genomic Basis of Local Adaptation in Landraces. Diversity (Basel) 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahib, R.H.; Migdadi, H.M.; Al Ghamdi, A.A.; Alwahibi, M.S.; Afzal, M.; Elharty, E.H.; Alghamdi, S.S. Exploring Genetic Variability among and within Hail Tomato Landraces Based on Sequence-Related Amplified Polymorphism Markers. Diversity (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva-Gutierrez, E.E.; Johansson, E.; Prieto-Linde, M.L.; Centellas Quezada, A.; Olsson, M.E.; Geleta, M. Simple Sequence Repeat Markers Reveal Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Bolivian Wild and Cultivated Tomatoes (Solanum Lycopersicum L.). Genes (Basel) 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glogovac, S.; Takač, A.; Belović, M.; Gvozdanović-Varga, J.; Nagl, N.; Červenski, J.; Danojević, D.; Trkulja, D.; Prodanović, S.; Živanović, T. Characterization of Tomato Genetic Resources in the Function of Breeding. Ratarstvo i Povrtarstvo 2022, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoso, A.; Carrasco, B.; Araya, C.; Salazar, E. Genetic Diversity and Distinctiveness of Chilean Limachino Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum L.) Reveal an in Situ Conservation during the 20th Century. Frontiers in Conservation Science 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Stam, R.; Tellier, A.; Silva-Arias, G.A. Copy Number Variations Shape Genomic Structural Diversity Underpinning Ecological Adaptation in the Wild Tomato Solanum Chilense. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tieman, D.; Zhu, G.; Resende, M.F.R.; Lin, T.; Nguyen, C.; Bies, D.; Rambla, J.L.; Beltran, K.S.O.; Taylor, M.; Zhang, B.; et al. A Chemical Genetic Roadmap to Improved Tomato Flavor. Science 2017, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, G.R.; Muños, S.; Anderson, C.; Sim, S.C.; Michel, A.; Causse, M.; McSpadden Gardener, B.B.; Francis, D.; van der Knaap, E. Distribution of SUN, OVATE, LC, and FAS in the Tomato Germplasm and the Relationship to Fruit Shape Diversity. Plant Physiol 2011, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Region | No. Accessions |

Major Allele Frequency (%) |

No. Countries |

Gene Diversity |

Heterozygosity | PIC | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | 178 | 82 | 1 | 0.26 | 0.04 | 0.22 | USA |

| North America excl. USA |

20 | 89 | 4 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.15 | Canada, Mexico, Trinidad, Cuba |

| Central and South America |

40 | 83 | 13 | 0.28 | 0.1 | 0.24 | Salvador, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Panama, Costarica, Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Venezuela |

| Europe | 23 | 90 | 9 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.13 | Bulgaria, Czech, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Netherlands, Spain, United Kingdom |

| Asia | 14 | 86 | 7 | 0.22 | 0.04 | 0.19 | Afghanistan, China, Japan, Nepal, Russia, Turkey, Taiwan |

| Australia | 1 | 99 | 1 | 0.004 | 0.01 | 0.003 | Australia |

| Region | No. of accessions in each cluster by region |

% of accessions in each cluster by region |

Total No. of accessions in each region | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Admixture | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Admixture | ||

| USA | 25 | 112 | 32 | 9 | 14 | 62.9 | 17.9 | 5.2 | 178 |

| North America excl. USA | 0 | 19 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 95 | 5 | 0 | 20 |

| Central & South America | 1 | 36 | 1 | 2 | 2.5 | 90 | 2.5 | 5 | 40 |

| Europe | 0 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 23 |

| Asia | 1 | 11 | 2 | 0 | 7.1 | 78.6 | 14.3 | 0 | 14 |

| Australia | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 276 | |||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).