1. Introduction

With over 70% of the households in the developing world relying on non-sewered sanitation systems, faecal sludge (FS) treatment assumes a pivotal step in containing the land and water degradation. Faecal sludge management is therefore a primary measure to treat this biohazard and pave a way to reuse the significant nutrients and organics beneficially [

1]. FS is fundamentally challenging because of its variability and unpredictability, and it is scientifically poorly understood. The mechanical, physicochemical and bio-chemical properties of FS are varied and complex, and it is difficult to summarise its characterization. The association of moisture in the sludge makes it more complex, and hence, one of the important stages of treatment of FS is solid-liquid separation. This stage of treatment helps in substantial volume reduction, wherein both the solid and liquid fractions can be treated separately with better effectiveness and efficiency [

2].

With moisture associated with to the solid particles of the sludge as unbound moisture and bound moisture, the separation of moisture from the solids in the sludge is not simple. Besides factors like the type of on-site sanitation system used and the quantity of water used in the toilets, different properties of the sludge influence solid-liquid separation. With a mix of microorganisms, colloids and particles of different origins, the extreme variability of FS adds another difficult dimension of complexity. [

3]. Analysis of these properties of sludge helps to understand the complex moisture retention behaviour of the sludge. Further, the design of solid-liquid separation technologies requires the characteristics of sludge for efficient operations.

The initial stage of this research distinguished the four categories of moisture associated with sludge solids (unbound moisture, interstitial moisture, vicinal moisture and intracellular moisture) and their proportions by different instrumentation methods. The focus of this paper is to provide the fundamental characteristic data and relatively comprehensive analysis of the mechanical properties of faecal sludge in the context of its moisture retention behaviour [

4]. This is important in the context of the circular economy where the reuse of treated faecal sludge in land applications is gaining momentum. The determination of the mechanical properties will help in understanding the moisture and nutrient retention, the compactibility in the natural environment and its use as a substitute for soil in land reclamation and bioremediation. A complete database of the engineering behaviour of FS is therefore necessary, and the minimum properties needed include the bulk and true densities, porosity, particle size distribution and zeta-potential, extracellular polymeric substances, rheology and dilatancy, microstructure analysis and compactibility [

5].

Comprehensive information on the mechanical behaviour of FS is scarce in the literature. Information does exist for sewage sludge and other industrial sludges. This study, henceforth, examined the mechanical properties of FS sludges and thus adds to the next layer of circularity, addressing the need to investigate the properties that influence or/and are influenced by solid-liquid separability of FS [

6].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Source of Samples

Faecal sludge for the research originated from different on-site sanitation systems as prevalent in different regions and countries across Africa and Asia. The samples were collected from the peri-urban areas of eThekwini municipality, Durban, South Africa and Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. The three types of faecal sludge were:

Faecal sludge from ventilated pit latrines (VIPs)

Faecal sludge from urine diversion dehydrating toilets (UDDTs)

-

Faecal sludge from septic tanks (ST) (also referred as septage)

- a.

With grey water (ST-wGW)

- b.

With only black water (ST-BW)

The VIP samples were collected from two latrines not desludged for at least 5 years. The UDDT samples were taken from the dehydrating vault of the UDDT, with an estimated sludge storage of 15-18 months. The septic tank (ST) samples were collected from desludging vacuum tanker trucks, and composite samples were taken from septic tanks which are connected only to the toilets (ST-BW) and the ones connected to all the wastewater flow (ST-wGW). The two ST samples represent both the African and South Asian types STs. The desludging interval of STs is usually less than a year for ST-wGW and 4-6 years for ST-BW.

VIP, UDDT and ST-wGW samples were collected from eThekwini municipality, Durban, and ST-BW sample from Pietermaritzburg. All the samples were collected in lined plastic containers with air-tight lids and screened for trash and debris and stored in the cold room at the laboratory at 4°C to avoid microbial degradation, and to minimize any loss in moisture. All the samples were analyzed for total solids (TS), volatile solids (VS), pH and electrical conductivity (EC) at the time of sampling, and these parameters were monitored for any change during the experimental period. Variation in the parameters was found to be in the acceptable range of <2%.

2.2. Experimental Methods

2.2.1. Density

The true density was determined using an Ultrapyc foam gas pycnometer (Anton Paar, Warszawa, Poland). Samples were kept dried in a ventilated oven for 12 hours at 51oC and kept in a desiccator before performing the analysis. The measurement settings applied were as follows: gas - helium; target pressure - 18.0 psi; flow direction - sample first; target temperature - 20°C; flow mode - monolith; cell size - medium, 45 cm3.

Porosity of the sludges was determined by the equation:

Where P is the porosity as a percentage, ρ

b and ρ

t are the bulk density and true density in g/cm3 respectively. The bulk density of the samples was determined by Archimedes’ principle, by measuring the volume of water displaced by a known mass of the sample [

7].

2.2.2. Particle Size Distribution and Zeta Potential Measurements

The PSD and ZP were determined using a Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments Corp, United Kingdom). The measurement of the angular variation of scattered light when a laser beam is passed through the dispersed particulate matter gives the PSD of the sample. The angular scattering intensity data is analyzed to calculate the particle size [

8]. All the samples were diluted using distilled water to generate suitable scattering intensity and 1 ml of the sample was transferred using a micropipette into the 10 mm diameter 40 µl disposable polystyrene cuvettes. Higher concentrations might not allow proper values of laser light obscuration, and lower concentrations might result in scattering from each particle resulting in multiple reflection. The refractive index of the dispersant (water) and the sludge particles were 1.330 and 1.520 respectively. The DLS approach yielded the hydrodynamic diameter and the polydispersity index (PI) as a measure of PSD. The mean diameter was obtained by calculating the average of three measurements. All the experiments were conducted at 25

oC [

9].

The Zetasizer uses Laser Doppler Velocimetry to determine the electrophoretic mobility. The experiments were conducted at 25oC in 40 µl polystyrene cuvettes with a path length of 10 mm using water as a dispersant. Measurements were performed in triplicates and by diluting the samples in 10 ml of distilled water.

2.2.3. Measurement of EPS and Total Organic Carbon (TOC)

EPS is composed of many organic substances mainly proteins, polysaccharides, humic acids, and little fractions of lipids, nucleic acids, and amino acids, etc. EPS which exists outside the cells is further divided into loosely bound EPS (LB-EPS) and tightly bound EPS(TB-EPS) and can be generally separated by centrifugation [

10,

11].

Extraction of EPS

There is no standard method for the extraction of EPS and its fractions - LB-EPS and TB-EPS and can be extracted by different physical and chemical methods. In this research, the EPS and its fractions were extracted from the FS samples by adopting a two-step heat extraction (mild step and harsh step) method [

12,

13,

14]. The method involved centrifuging the sample in a 50 ml centrifugal tube at 4000 rpm for 5 min, discarding the supernatant and resuspending the sludge pellet in 0.05% NaCl (w/v) warm solution at 50

oC and sheared using a vortex mixer for 1 min. The suspension was then centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min, and the organic matter in the supernatant was regarded as LB-EPS. For TB-EPS, the sludge pellet was resuspended again in 0.05% NaCl solution and this suspension is heated in a water bath for 30 min at 60

oC. Post heating, the suspension was centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 15 min, and the supernatant liquid was regarded as TB-EPS. The cell lysis was said to be of no significance after such extraction process [

15].

EPS – protein and carbohydrate determination

Since proteins and carbohydrates form the major components of EPS, measurement of proteins and carbohydrates of the extracted fractions was carried out. For the measurement of proteins, measuring amino acids gives an accurate approximation of the proteins present. However, due to cost and time considerations, the use of total nitrogen for determining crude protein is widely used [

16]. In this research, the nitrogen was determined by the nitrogen combustion method, and the protein content was calculated as a ratio of protein to nitrogen.

Elemental analysis of nitrogen, along with carbon and sulphur, was quantified in the multi-element combustion CNS analyzer Leco CNS 2000 (Leco Corporation, St. Joseph, MI). Fitted with an auto-sampler, the CNS analyzer heated up to 1450oC in a pure oxygen environment, with 1 – 2 g of sample placed in the oven in a ceramic boat.

Crude Protein Percent (CP%) [

17] was given by

where F is 6.25 (from 6.25 g proteins per g N)

The total carbohydrates, including mono-, di-, oligo-, and polysaccharides, was analyzed by the phenol-sulphuric acid method [

16]. All experiments were carried out in triplicate.

The total organic carbon (TOC) was determined by the standard operating procedure, involving chemical oxidation of the sludge samples using sulphuric acid, potassium dichromate and mercuric sulphate. The reduced chromium was measured at 590 nm in the spectroquant [

18].

2.2.4. Penetrometer Test

Penetration tests and texture profile analysis (TPA) were conducted using a LS1-302 penetrometer universal traction machine (Ametek Lloyd instruments, England) equipped with a 10 N probe and a 30 mm diameter spherical geometry probe. FS samples weighing 60g were placed in an aluminum capsule and penetrated to a depth of 15 mm at a constant speed of 1 mm/s, and included the load phase (compression) and a discharge phase (relaxation) [

19,

20]. This setup simulated the practical conditions FS might encounter in its handling and processing.

2.2.5. Rheology and Dilatancy

FS behaves like a viscoelastic substance, blending the attributes of solids and liquids, thereby exposing the traits of viscosity and elasticity when subjected to stress or deformation. An oscillatory experiment such as amplitude sweep can be conducted to measure these changes in rheology. The dynamic rheological measurements were carried out using Anton Paar Physica MCR 302 (Anton Paar Benelux BV, Belgium) in the chemical engineering laboratory at the University of Liege, Belgium. The instrument was a controlled stress rheometer equipment with a 50 mm parallel plate geometry. The gap between the fixed plate and the oscillating plate was fixed at 2 mm. The samples were homogenized before adding onto the plate on the rheometer, at a temperature of 20oC.

The samples were submitted to a frequency sweep, from 0.1 to 100 rad/s, at a constant shear strain in the linear viscoelastic region, and the strain sweep experiments were conducted from 0.01% to 10%. Each measurement was performed in triplicate. The elastic modulus or storage modulus, G', characterized the energy stored in elastic form and was retrievable by the sample (elastic component); the viscous modulus or loss modulus, G'', characterized the energy lost by friction (viscous component), and are given by:

Where the complex viscoelastic modulus G* is defined as the ratio of the amplitudes stress and strain. The G’ and G” were presented in the results, which were the function of the frequency [

21].

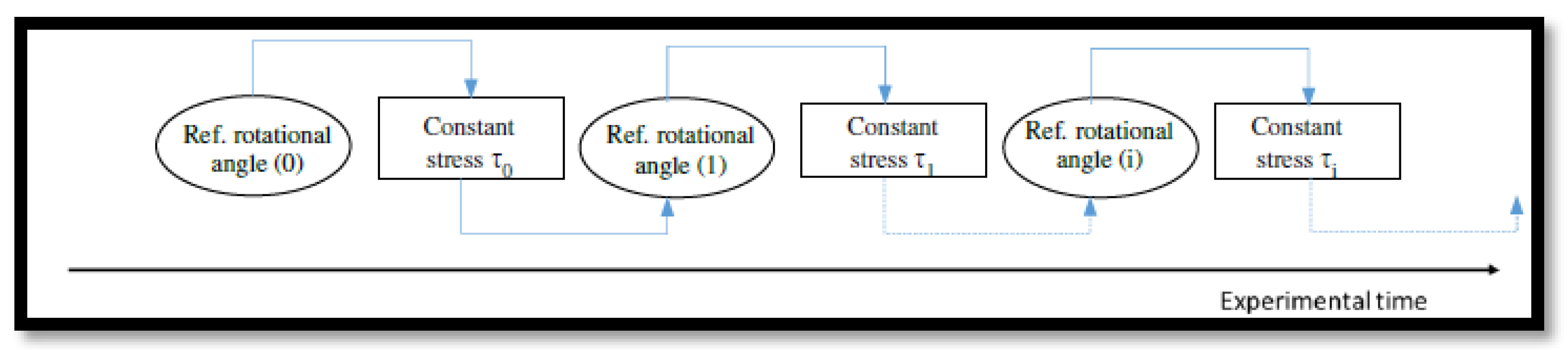

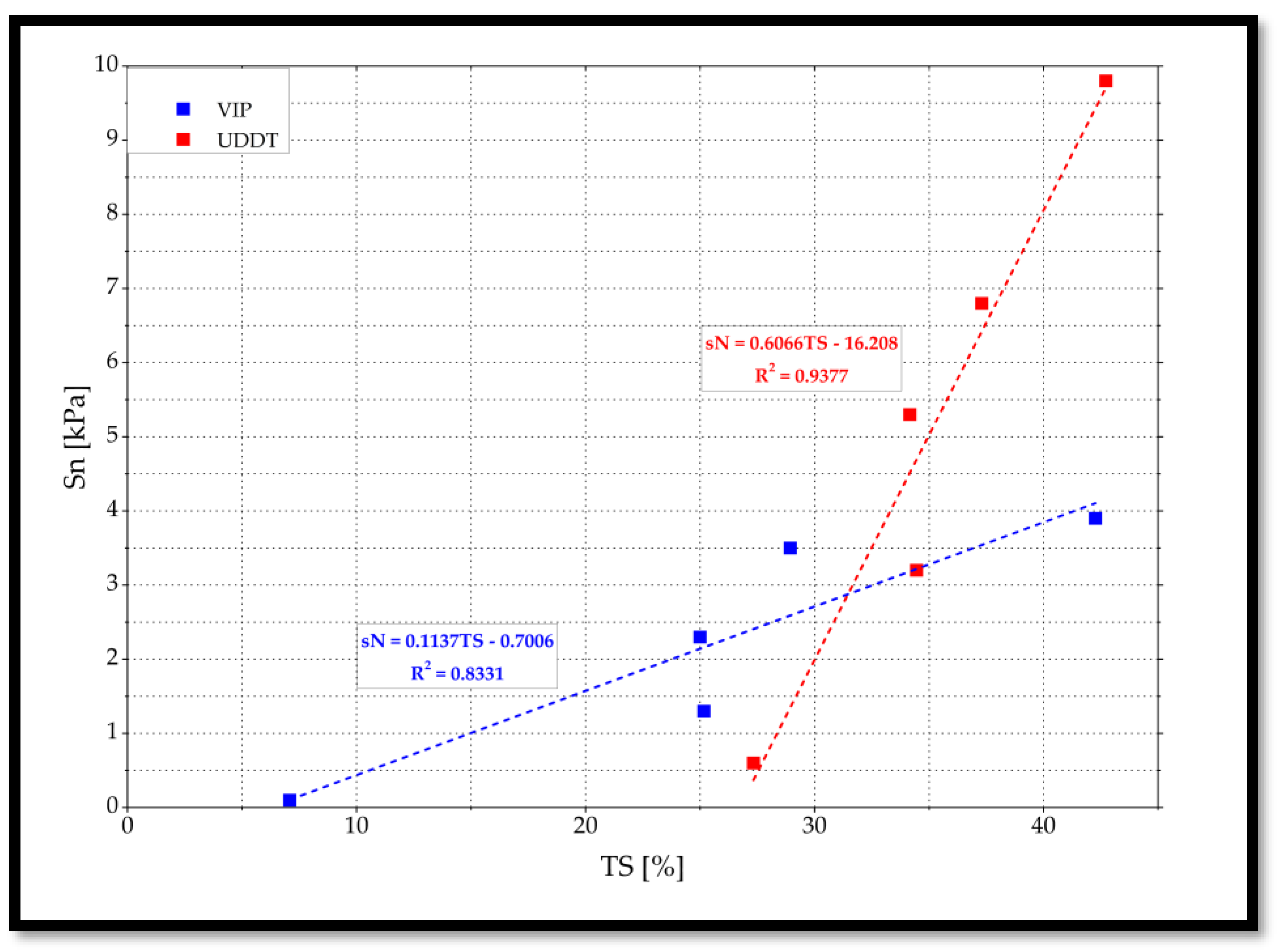

Mouzaoui et al., (2018) developed a specific procedure to determine dilatancy by considering the edge effects and measuring the normal force simultaneously with the tangential shear stress using a rotational rheometer. Samples with different TS of VIP and UDDT sludge ranging from 10% to 43% were prepared with dilution (low TS) and centrifugation (high TS). The rheological investigations were carried out at IMT-Mines, Albi, France with a stress-controlled RS600 instrument HAAKE Rheostress 600 (Thermo Scientific, Germany), and the data analysis was assisted by the RheoWin software. Serrated parallel plates of 35 mm diameter were used with a gap of 2 mm. For different TS concentrations, a stress sweep was applied to the sample which consisted of successive steps of constant dynamic stress of increasing intensity, as shown in

Figure 1. A pause was marked between each step as a reference to allow for the correction of edge effects (fractures and cracks). Thus, by applying a constant dynamic rotational angle, the edge effects reduced in accordance with the corresponding stress. Tests were conducted in triplicate to evaluate reproducibility, and normal force was recorded along with the tangential shear stress.

2.2.6. Filtration-Compression Test

A lab filtration device at the Environmental Engineering laboratory, Cranfield University, United Kingdom, designed to carry out permeability and compressibility tests, was adapted to carry out the compactibility experimental work. Experiments were carried out for two of the four FS samples – VIP and ST-BW, thus representing both the high TS sample and the low TS sample. The device consisted of a compressive piston moving in a 40 mm diameter cylinder of depth 120 mm. At the bottom of the chamber, a filter paper (Fisherbrand of porosity 0.6 µm) was placed on a perforated disk. A stepped pressure was applied to the piston, controlled by a program based regulating system. The pressure steps were at 0.2 bar, 0.5 bar, 1.2 bar and 3 bar.

The raw FS samples of approximately 50g±3g were added into the cylindrical vessel without any change in its initial characteristics. The piston was firmly placed in the cylinder to avoid any air gaps. The pressure system was started, and the filtrate was collected in a tray. The loss of moisture was measured continuously by data logging software connected to the device. The test duration extended up to 3-7 days depending on the type of FS sample. After the completion of the test, the moisture content of the sample cakes was measured as per standard methods [

23]. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was carried out for all the samples, before and after the compaction tests. The analysis was carried out using pure N

2 as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 10mL/min, with 35 - 40 mg of samples and cell temperature from ambient (27

oC) to 90

oC at the rate of 10

oC/min, and maintained at 90

oC in isothermal condition for 45 mins using a TGA8000 (Perkin Elmer, USA) [

24,

25].

2.2.7. Microscopic Observations

Observations were conducted with the environmental scanning electron microscope (ESEM) to explore the surface morphology of the FS at the University of Liege, Belgium. The ESEM-FEG XL30(Philips, USA) is capable of imaging any sample including wet samples, which is the pre-requisite for imaging raw FS samples. No changes were made to the samples. The samples were analysed at an acceleration voltage of 10kV and magnification of up to 12.8 kX.

3. Results and Discussion

3.2. Densities and Porosity

The ratio of the mass of the sample to its bulk or macroscopic volume including the pore spaces is the bulk density of the sludge. Usually expressed in grams per cubic centimetre, bulk density conforms the accepted physical terminology. True density was determined by the gas pycnometer and porosity was calculated as per equation 1.

Table 1 contains the results for bulk and true densities, and porosity. The bulk density of UDDT sample was significantly higher than the other FS samples due to less initial moisture content.

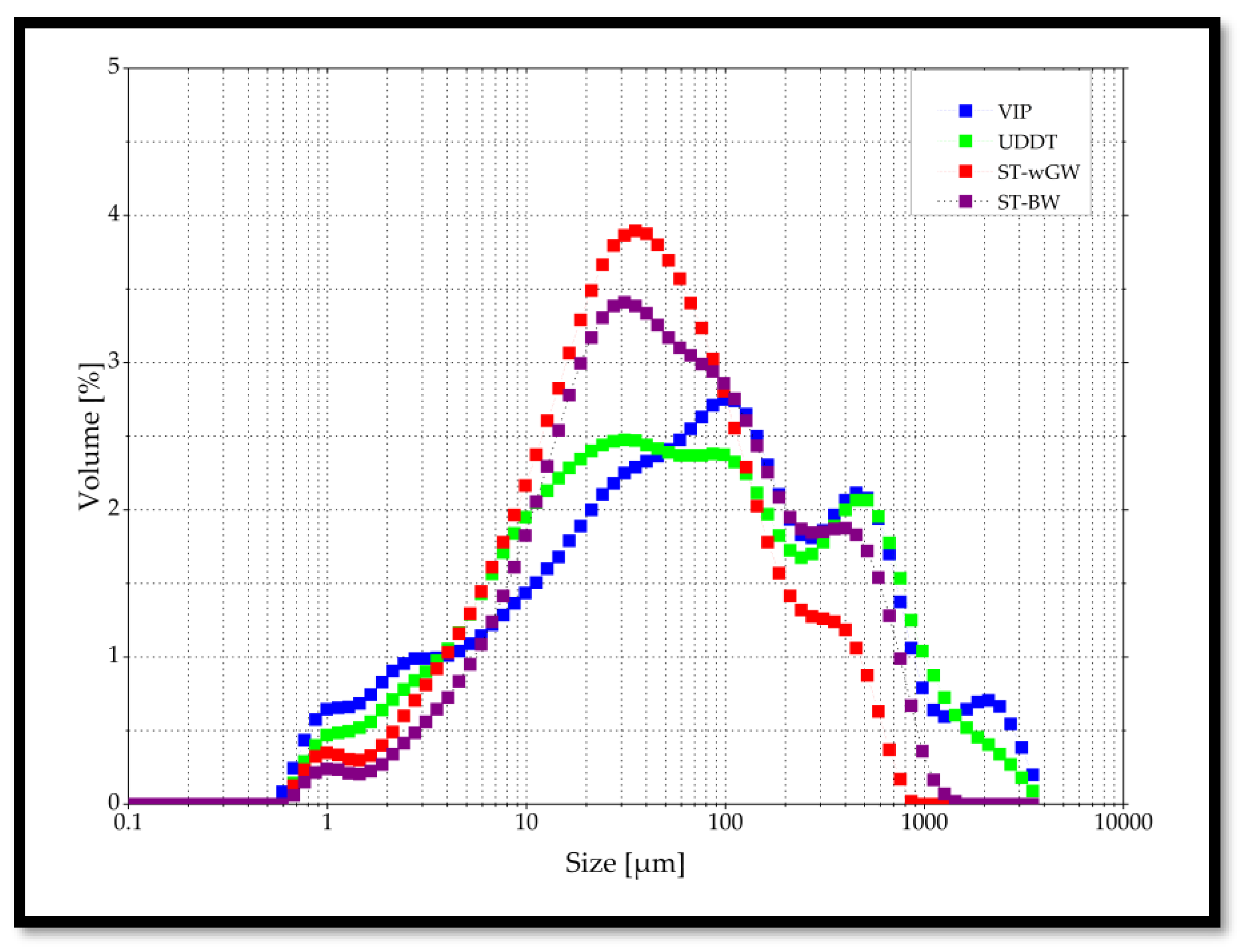

3.2. Particle Size Distribution (PSD)

Colloidal and supra-colloidal particles affect the settleability of sludge particles, and hence knowing the amounts of particles present in the sludge according to its size is important. Different particle sizes of the sludge particles influence its moisture retention characteristics. The smaller the particle size, the harder is the solid-liquid separability because of its higher specific surface which binds more moisture per volume fraction. The lower the particle size, the lower its settling velocity and higher its adhered moisture [

26]. PSD characterization of aerobic sewage sludges is typically unimodal, and its maximum is towards the larger particles. The particle sizes of sewage sludge from aerobic treatment facilities varied from 0.3 µm to 310 µm, with the largest fraction of over 60% in the range 50-60 µm and the lowest range from 0.40 µm to 2.59 µm. Approximately, 90% of the particles did not exceed 140 µm in sewage sludge. The presence of some colloidal particles of size <1 µm influenced the solid-liquid separability [

9,

27].

On the contrary, the primary PSDs of the FS samples were mainly distributed in the range 10-1000 µm with 20% of the particles <10 µm, 40-60% in the range 10-100 µm, 21-34% in the range 100-1000 µm, and <5% > 1000 µm (

Figure 2). The high TS samples of VIP and UDDT had similar distribution, while both the ST samples were similar to each other indicating the possible role of greywater and other contaminants. All the samples had a relatively uneven but similar distributions. Further, literature says that the flocs are fragmented under anaerobic conditions and hence, the FS which are primarily anaerobic sludges, have reduced particle size was fragmented. Over 95% of the particle were less than 1000 µm for UDDT and VIP sludges, and for ST sludges, the particles <1000 µm make up to 99% of the sample. This reduced particle size result in low settleability which was evident in the batch settling tests carried out for the same samples [

28] (under review). However, the presence of increased specific surface area can influence solid-liquid separability positively with the addition of an appropriate coagulant [

29].

3.3. Zeta Potential

The surface charge of the sludge particles provides its agglomeration behaviour, i.e. its ability to coagulate and release moisture. The value of ZP indicates the dispersion behaviour of the sludge. ZP is used to characterize the positive and negative charges on the surface of materials and the electrostatic repulsion which prevents them from accumulating and thereby gaining mass to sediment. The ZP of all the samples was negative, indicating that all FS are negatively charged. While the high TS samples had higher values of ZP, the lower TS samples were similar to that of sewage sludges. Particles with the ZP between minus 30mV to plus 30mV tend to release the vicinal moisture on the surface of the sludge particles upon addition of a coagulant. The closer the ZP value to its isoelectric point when ZP equals zero mV, the easier it is to coagulate [

30].

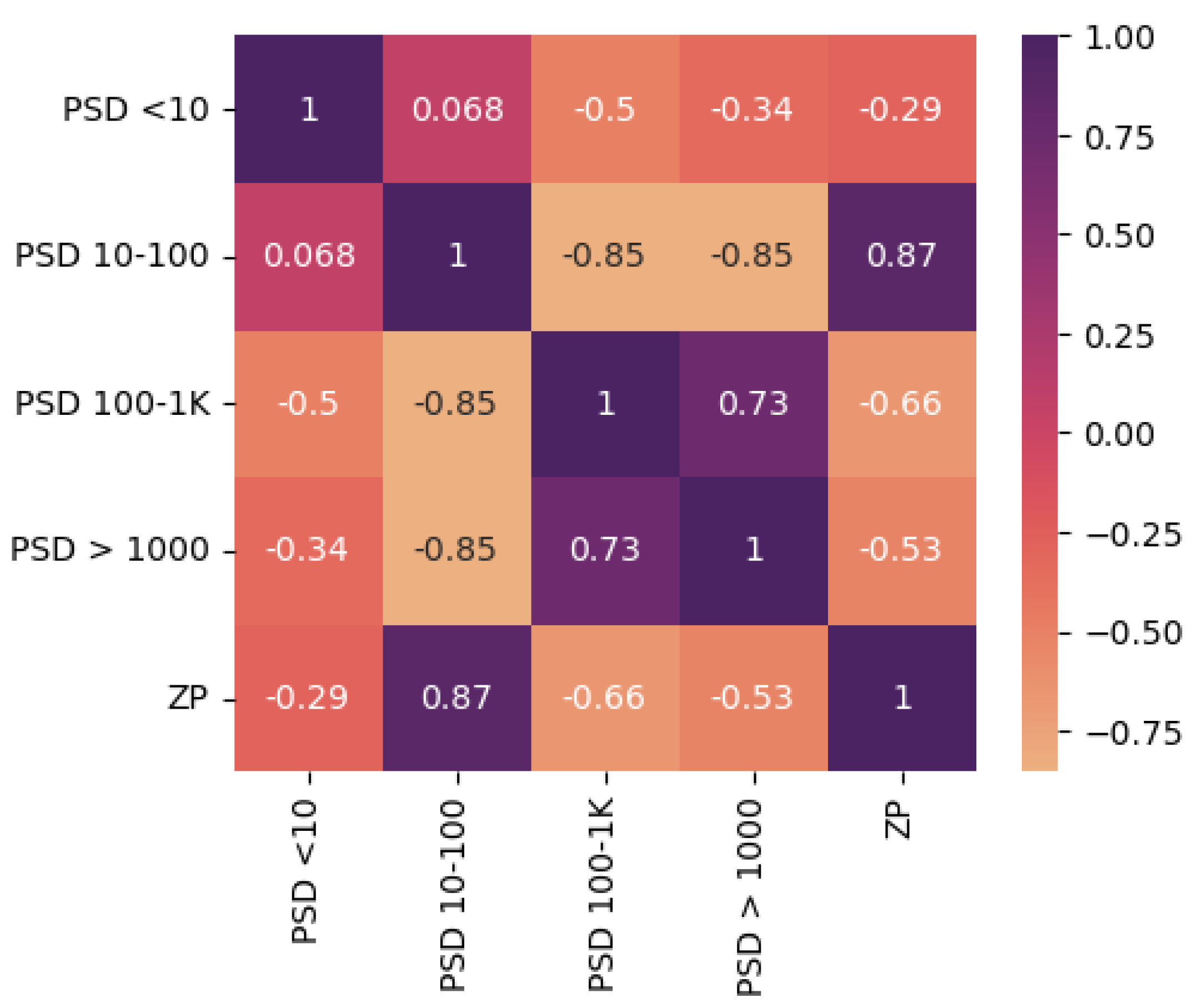

The heat map of the PSD and ZP (

Figure 3) provided the correlatability between fractions of the PSD and ZP. Analyzing the correlation between PSD and ZP using Python, ZP was positively correlated with the percentage of particles between 10-100 μm. A correlation value of 0.87 indicated strong positive correlation. The higher the lower diameter particles, higher and negative the ZP.

ZP was negatively correlated with the percentage of particles <10 μm, between 100-1000 μm and >1000 μm. The relationship between PSD size ranges (in μm) and ZP (mV) can be given by equation 3:

3.4. Extracellular Polymeric Substances

Though by definition, interstitial moisture is simply the moisture trapped between sludge particles, it is evident that there are some weak forces acting on the interstitial moisture. A significant fraction of moisture is held by a polymer-like network with the presence of large concentrations of counter-ions. Extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) are secreted by bacteria primarily to protect the solid biomass in the sludge from the external environment. Though their exact role is not completely understood, EPS is characterized by high moisture and makes it difficult to unpack the solid aggregates, thereby leading to a hydrated state of moisture retention. EPS forms a significant fraction of this sludge mass. EPS is such a critical property of FS because it influences the physicochemical behaviour of the sludge and thus affects its moisture retention by providing electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonds. EPS is one of the most influential substance in terms of the moisture retention characteristics of the sludge because of its cross-linking polymeric network like structure [

31]. It is composed of many organic substances mainly proteins, polysaccharides, humic acids, and little fractions of lipids, nucleic acids, and amino acids, etc., with the proteins and polysaccharides as the major fractions [

11]. Because of its complexity and importance, EPS is extensively researched, specifically in solid-liquid separability of sludges. This is because EPS forms a complex three-dimensional sludge matrix like structure [

32]. EPS in the sludge matrix is usually with a double layer structure, consisting of loosely bound EPS (LB-EPS) and tightly bound EPS (TB-EPS). The LB-EPS is said to be diffused from the TB-EPS, and functions as surface for cell attachment. This classification of EPS is based on the extraction methodology [

13]. The role of proteins and carbohydrates part of EPS is also significant in the solid-liquid separability. The ratio of EPS

carb to EPS

prot is a good indicator to the moisture retention properties [

29].

Further, most of the on-site sanitation systems such as septic tanks and pit latrines in non-sewered sanitation are anaerobic. Anaerobic atmospheres affect EPS and was reported to have significant impact on the biosolids’ structure. This study analyzed the dynamics of EPS and the various sludge characteristics from the different type of on-site sanitation systems. This helped determine the effect of the extent of anaerobicity on EPS. Within EPS, the EPScarb to EPSprot ratio was analyzed to investigate its effect on moisture retention.

The results of the measurement of the EPS are shown in

Table 2. TB-EPS has a significant impact on the stability of the sludge, and UDDT and ST-wGW sludges have the highest stability, also indicated by their VS/TS value. The high TB-EPS in ST-wGW can also be attributed to the other substances such as soaps and oils present. Further, the carbohydrate to protein ratio is high in the ST samples, and lowest with the UDDT sludge. Further, the carbohydrate content was significantly higher than that of the proteins attributed to the anaerobicity of the sludges [

33], whereas in sewage sludges, the proteins are higher than the carbohydrates. It is also argued that anaerobically digested sludges have increased EPS, and hence have higher moisture retention [

34]. More research is necessary, specifically with anaerobic sludges from OSS to correlate the anaerobic transformations with the binding strength and the roles of shifting particle sizes and changing EPS.

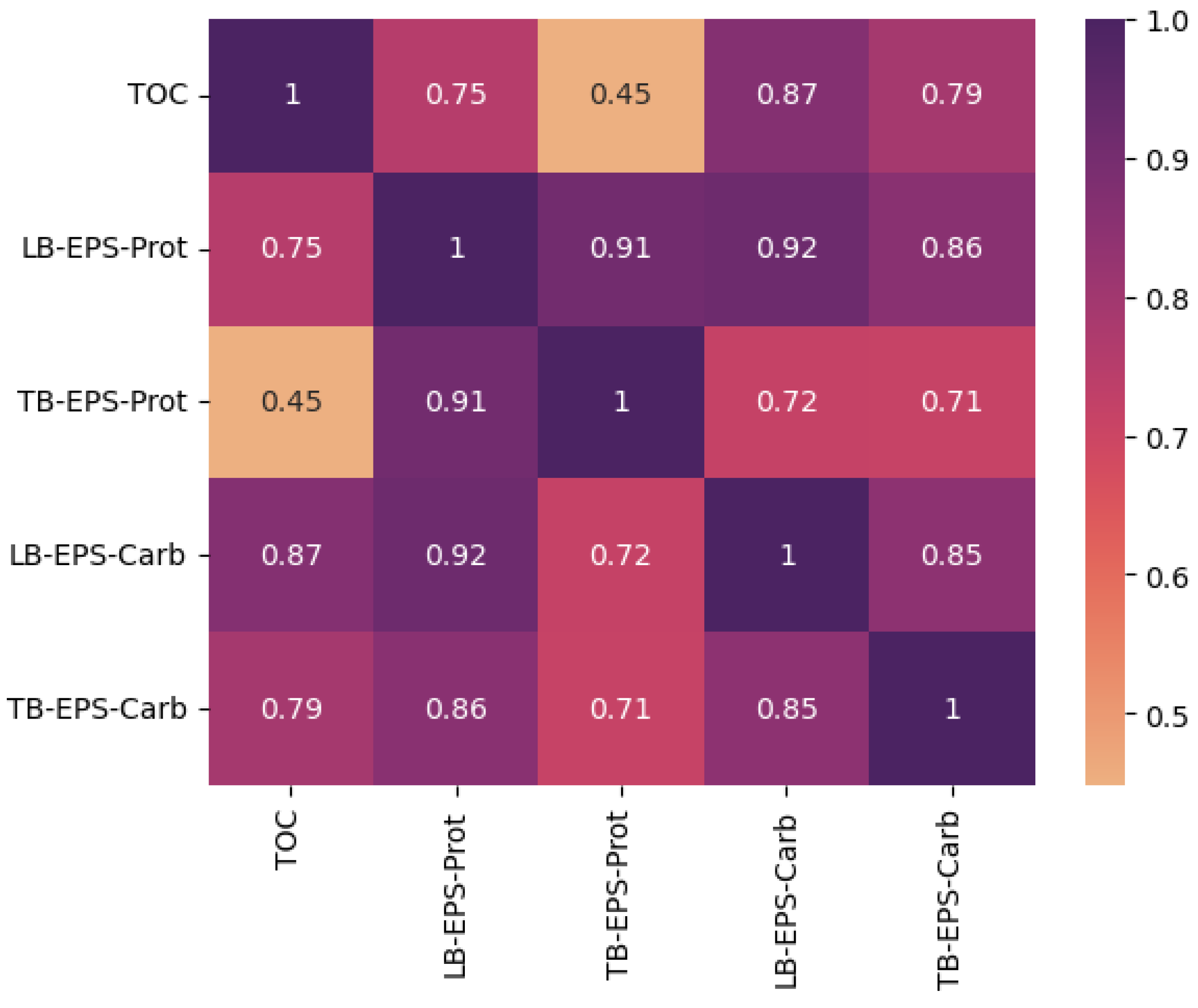

From the correlational analysis between TOC and EPS (

Figure 4), TOC was positively correlated to proteins and carbohydrates, both loosely bound and tightly bound, with the correlation with LB-EPS

carb at the highest at 0.87. TB-EPS

prot is strongly correlated to LB-EPS

prot, but least correlated to TOC. Both LB-EPS

carb and TB-EPS

carb show strong positive correlation with LB-EPS

prot.

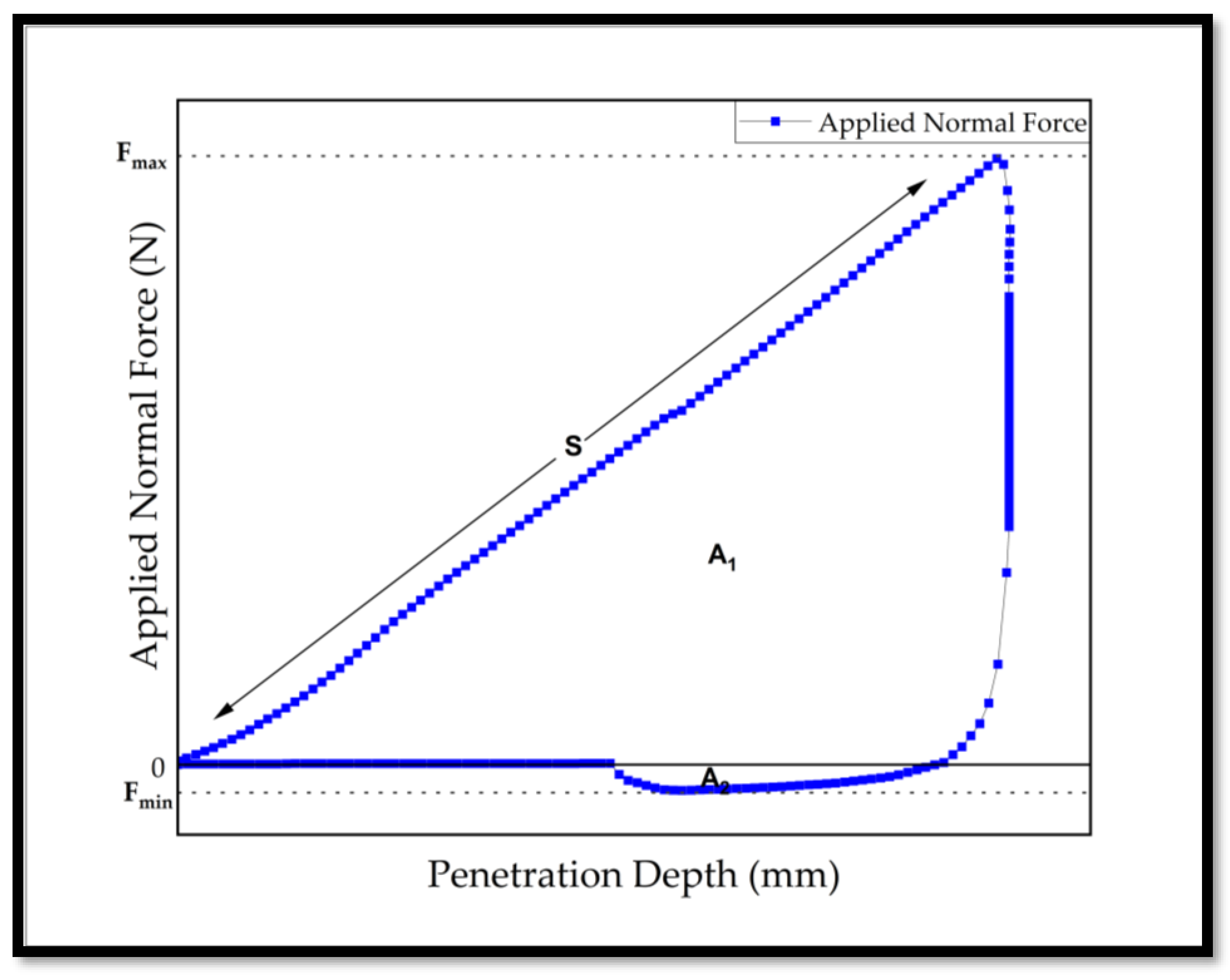

3.5. Penetration Curve

The application of a ball penetrometer was carried out to investigate the cohesiveness and adhesiveness of the FS samples. During the penetration of the ball in the sample, the surrounding sample undergoes shear strains and softens, and a certain extent of the softening is measured in the resistance [

35]. In

Figure 5, the schematic penetration curve for faecal sludge (FS) was presented. In this graph, the maximum positive peak (Fmax in N) represent the force required for the probe to penetrate the sample to its maximum depth. Fmax is commonly associated with the firmness or hardness of the sample. The positive area under the curve up to Fmax (A+ in mJ/Nmm) reflects the work performed by the probe during the compression test on the sample [

36]. For high TS sludges, adhesion and cohesion strengths were no longer the same due to lower moisture content. The shearing stress of adhesion reached a maximum whereas the shearing stress of cohesion continued to rise, which indicated the resistance between the sludge and the probe was smaller than the internal resistance of the solid-solid and solid-liquid particles. This explains the increase in stickiness of sludge as moisture was removed [

37].

The minimum negative peak (Fmin in N) corresponds to the force needed to detach the sample from the probe and is defined as the adhesive force of the sample. A more negative Fmin value indicates higher adhesion. The negative area under the curve (A

1, in mJ/Nmm) represents the work required to separate the probe from the sample, acting as an indicator of adhesiveness, stickiness, or tackiness (i.e., the energy needed to remove the sample from surfaces) [

38,

39].

The initial slope of the positive part of the penetration curve (S in N/mm) was related to the stiffness of the sludge sample [

40]. Finally, the cohesive load of the sample was obtained from the maximum load recorded (in kPa) when the probe penetrates the sample [

19,

41]. The mean values of the textural properties for FS, calculated from three measurements, are provided in

Table 3.

Although the mean values for the textural properties of FS are not widely reported in the literature, the results of this study on FS samples do not compare to the same magnitude as those reported for sewage sludge samples before its hydration nor align with those reported for poorly flocculated sewage sludge samples [

42,

43]. The cohesiveness of the FS samples analysed in this study lay between 10 and 100 times lower than that reported for flocculated and dehydrated sewage sludge processed by filtration under optimal conditions. The adhesiveness of FS samples were 5 to 10 times greater compared to sewage sludge[

19];. This suggest that while FS could be directly applied in agricultural settings and for land bioremediation, it lacks the structural stability needed for storage in piles and tend to adhere easily to tools and machinery, thereby complicating its handling. This issue can be mitigated operationally by incorporating a texturizing agent—such as sawdust, dry sludge, etc. — which can absorb moisture (unbound and interstitial), and provide structural support to facilitate material handling[

44,

45,

46,

47].

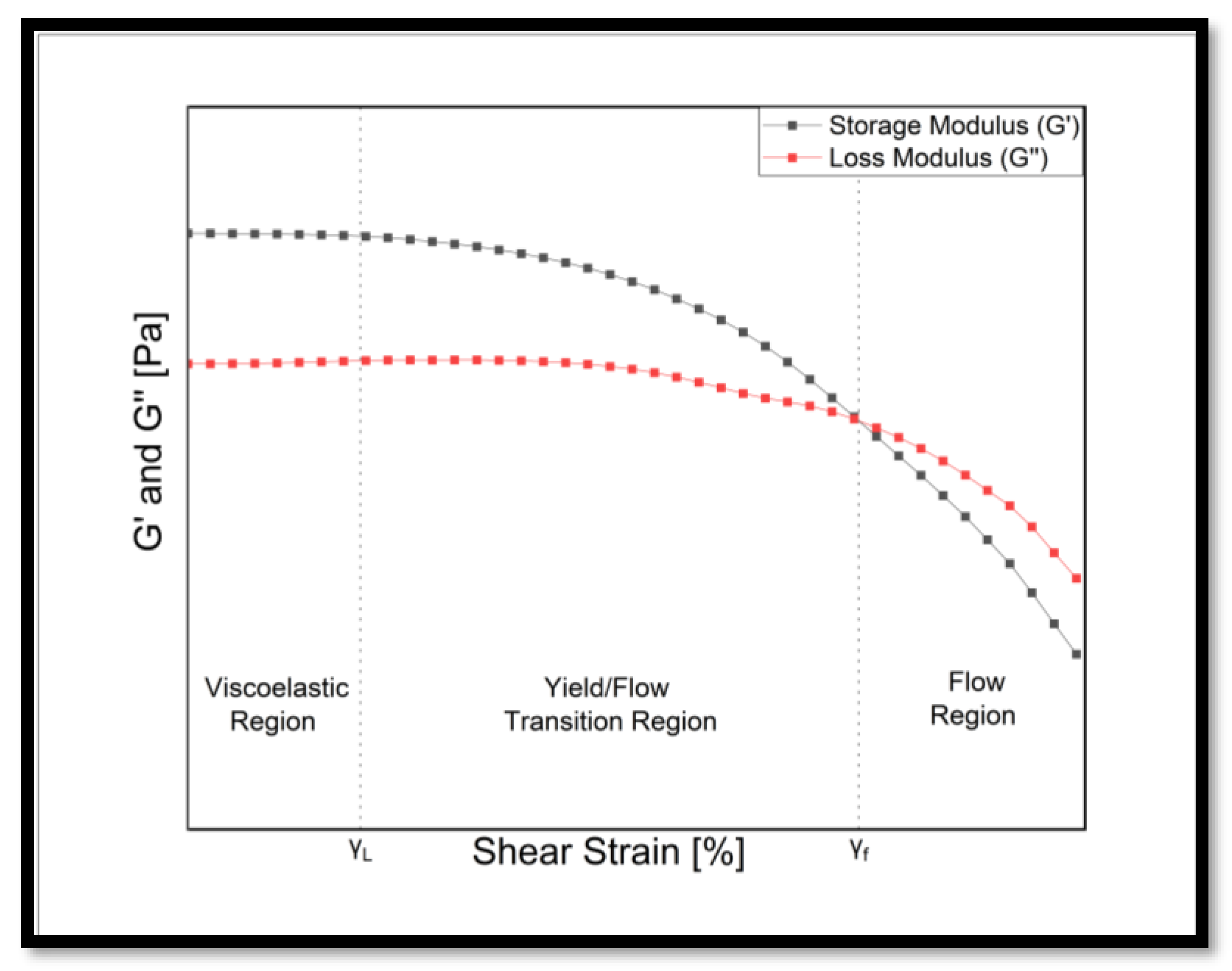

3.6. Rheology and Dilatancy

The rheological characterization of FS provides valuable quantitative parameters that describe its complex, flexible structure, which arises from the interaction of its three main components—solid particles, moisture, and air. The forces between these components define the molecular structure and the solid-moisture framework. FS behaves as a soft, viscoelastic, non-Newtonian fluid with non-constant viscosity; this gel-like material does not transition into a liquid state and exhibits significant resistance to flow, which varies with its moisture content [

48]. Specifically, the non-Newtonian properties of sludge intensify as unbound moisture decreases and bound moisture increases. Understanding the rheological behaviour of FS, influenced by both its initial and bound moisture content, is essential for predicting its solid-liquid separability [

49]. To characterize the viscoelasticity of FS, two fundamental parameters of dynamic rheology were applied – the elastic modulus or storage modulus (G'), and the viscous modulus or loss modulus (G'').

Most studies on the rheological behaviour of FS have focused on its unbound moisture phase, specifically at low to moderate total solids (TS) concentrations between 1% and 5%. The Herschel-Bulkley model has commonly been applied to describe the yield stress and flow curve behaviour in these low-TS sludges [

36].

However, in sludges with higher TS content, FS exhibited a solid-like behaviour at rest that deformed under applied force and retained this deformed state after the force was removed. This behaviour resulted from the interactions between the sludge's components, which form microstructures that, while initially were resistant to deformation, but eventually break up and flow under applied force [

50].

For more concentrated FS samples, classical oscillatory rheology has been used effectively to study its behaviour, yielding consistent and reproducible results by managing crack and fracture formation [

22]. The method used to measure the rheological properties in this study is particularly useful for samples with TS content between 20% and 45%, representing the interface between unbound and bound moisture zones. As TS content increases, the sludge transitions from an elastic to a plastic regime, allowing for the assessment of dilatancy.

Dilatancy, a phenomenon first described by Reynolds in 1885, is defined as the tendency for densely packed hard particles to expand perpendicularly to the shear plane when subjected to shear. In simpler terms, as particles tightly packed together exert force on neighbouring particles during motion, a normal force arises simultaneously with tangential shear stress, initiating movement in adjacent particles [

22].

Figure 6 presents a schematic of the results from amplitude sweeps, or rheogram, showing three distinct regions: viscoelastic, transition, and flow. Each of these regions is defined by specific shear strain limits. In all the samples studied, G’ and G” remained nearly constant at low strain levels, thus displayed a linear viscoelastic, gel-like behavior. As strain increased and the FS reached its viscoelastic limit or yield stress (γ

L), G’ began to decrease significantly, while G” continued rising to a peak before starting to decline. According to the literature on sewage sludges, higher TS content expands in the linear viscoelastic (LVE) region in sludge. However, with FS, the LVE region contracted to about 1% strain. This could be attributed to due to the anaerobic nature of FS, the reduced TB-EPS content and the absence of coagulation or flocculation treatments. This is a significant reduction compared to the nearly 20% strain observed in other high-TS aerobic sludges, which also increased the sludge’s sensitivity to shear [

51,

52].

At the intersection point of G’ and G”, defined as the dynamic yield stress (γF) or flow point. The microstructure of the high TS VIP and UDDT sludges were strong enough to overcome any instable occurrence such as sedimentation. Further, the higher G” values indicated good elastic behaviour and spatial network structures. The increase in G” may be due to the disruption of the EPS network structure by anaerobic conditioning, and release of interstitial moisture at higher strain amplitudes. This was also observed by [

51] for sludges treated by acidification and anaerobic mesophilic digestion.

Since G′ > G ′′ for all samples, they were classified as viscoelastic gels, meaning they behaved as viscoelastic solids under the measurement conditions used in the test. The mean values of G’, LVE and flow point for all the studied samples were shown in

Table 4.

Sludge, at lower TS, can be described as a diluted suspension and a classical rotational rheometer can be adapted. There is enough moisture to fill the voids between the sludge particles, and the moisture acts as a lubricating effect on the motion of the solid particles. As the TS exceeded the plastic limit, the sludge could no longer be considered continuous and was more granular in nature. Thus, at higher TS, cracks and fractures were highlighted, and this was captured during the shearing tests. This indicated the frictional interactions of solid-solid particles, influenced by solid-liquid interactions. The sludge started to dilate leading the solid-solid particle interactions exhibiting larger shear stresses. These frictional interactions cause dilatancy, wherein the yield stress was no longer associated with the viscous forces but with the frictional contacts of solid-solid particle interactions. This has been observed in pasty materials such as concrete, fresh cement, clay, etc. [

39,

53]. The results obtained for dilatancy are shown in

Figure 7.

3.7. Filtration-Compression Cell Test

The moisture-solid particle interaction in sludges is due to the complex bio-polymeric network of mainly bacteria, resulting in a porous fractal-like structure. For highly compressible sludges, a significant quantity of moisture can be removed by filtration, especially the free moisture and some moisture occupied in the voids between the solid particles, called interstitial moisture. The characterization of moisture distribution within the sludge provides good indicators to predict the solid-moisture interactions [

54].

Among the dewaterability indices, both capillary suction time (CST) and specific resistance to filtration (SRF) do not provide the maximum moisture removal nor the type of moisture removed. Both centrifugation and a stepped pressure filtration technique can help evaluate the determination of the maximum moisture removal [

55], and together with the thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), the type of moisture removed can further be assessed. This approach of determining the relative contents of unbound and bound moisture fractions, and corresponding moisture-solid binding energy can help evaluate the sludge dewaterability [

56].

The application of stepped pressure filtration technique is adopted in the filtration-compression cell test (FCC) to help understand the moisture-solid particle interactions in FS, and the results could possibly be correlated to various other membrane separation technologies available for solid-liquid separability. In the FCC, a compressive piston squeezes the sludge in the direction of the filter media, and correspondingly, the filtrate is separated from the solid particles leaving behind a sludge cake [

57].

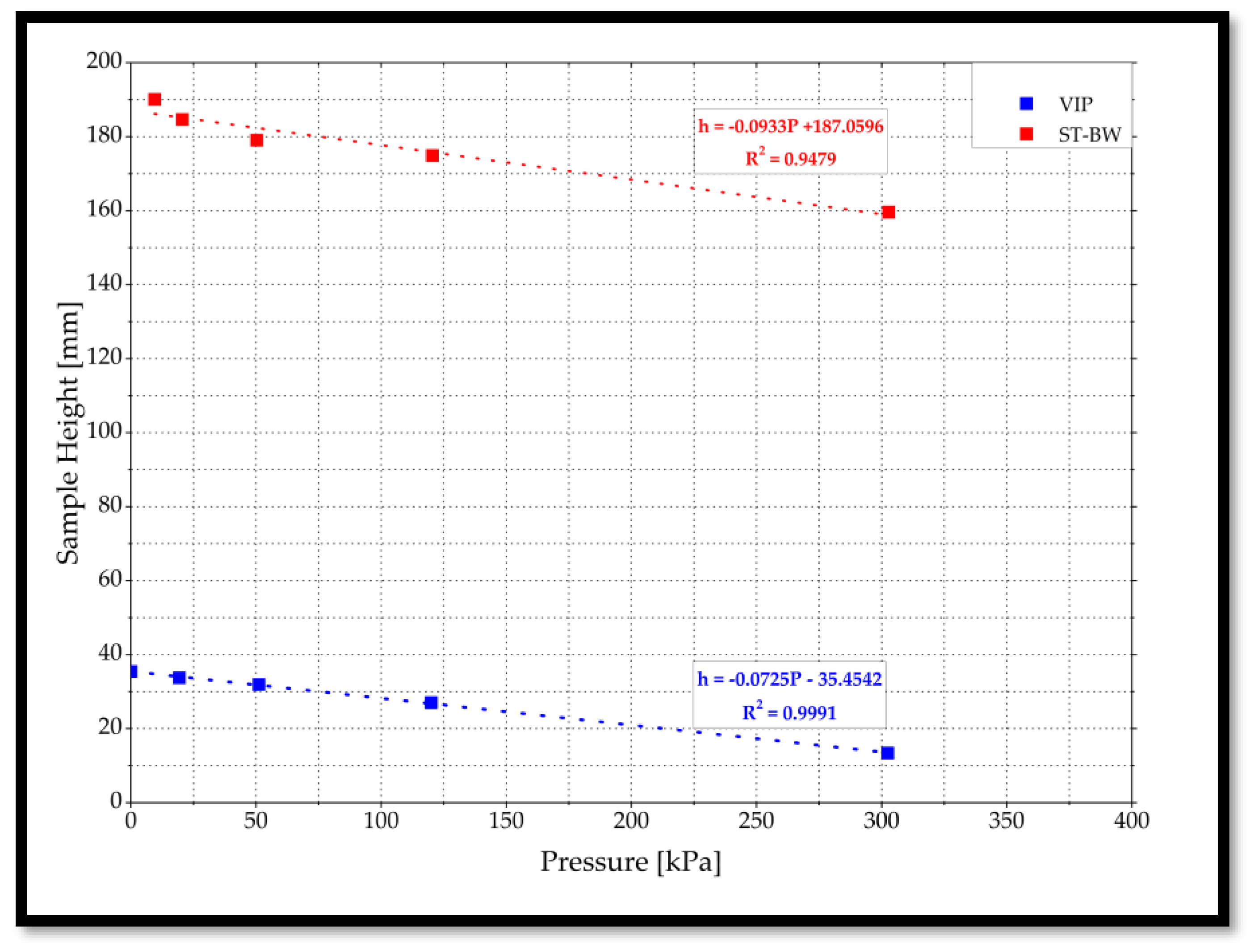

The sample height vs pressure plot as show in

Figure 8, provide the filtration phase as well as the expression phase. The filtration phase was linear, which was quite evident in the ST-BW sample which had a higher initial moisture content and hence a longer filtration phase. It was during this phase that the cake formation occurred, followed by a compression turn-up, where the cake formation ended. During the expression phase, there was movement of the solid particles within the cake structure, leading to shear stress, which became higher than it was when the sample was in suspension. This led to breakdown of weak flocs and seemed to characterize the non-traditional filtration behaviour of some sludge samples, as in FS. This was in accordance to the linearized filtration theory prediction of the classic “two-stage” behaviour of sludges [

55], and represented the removal of moisture by cake squeezing. Several researchers have made this observation, but the results are still varied. The influence of the applied pressure on the initial sample and the final cake was not clear. The results were in good agreement with the findings by [

58] and this phenomenon could be attributed to the moisture boundness of the sample which significantly decreases with increasing pressure at the filtration phase with the release of interstitial bound moisture into unbound moisture occurred. The transition of the filtration phase to the expression phase was smooth and hence it was not possible to accurately ascertain the interface.

The difference in the time scale to reach the completion of the filtration phase was dramatically different, with highly extended time for VIP as compared to the ST-BW. Given that the initial TS of VIP sludge was higher than that of the ST-BW sludge, the time to reach the end of filtration should have been shorter but it was almost an order of magnitude greater for the VIP sludge. This suggested that the VIP sludge was more compactable but had low permeability.

3.8. Thermogravimetric Analysis

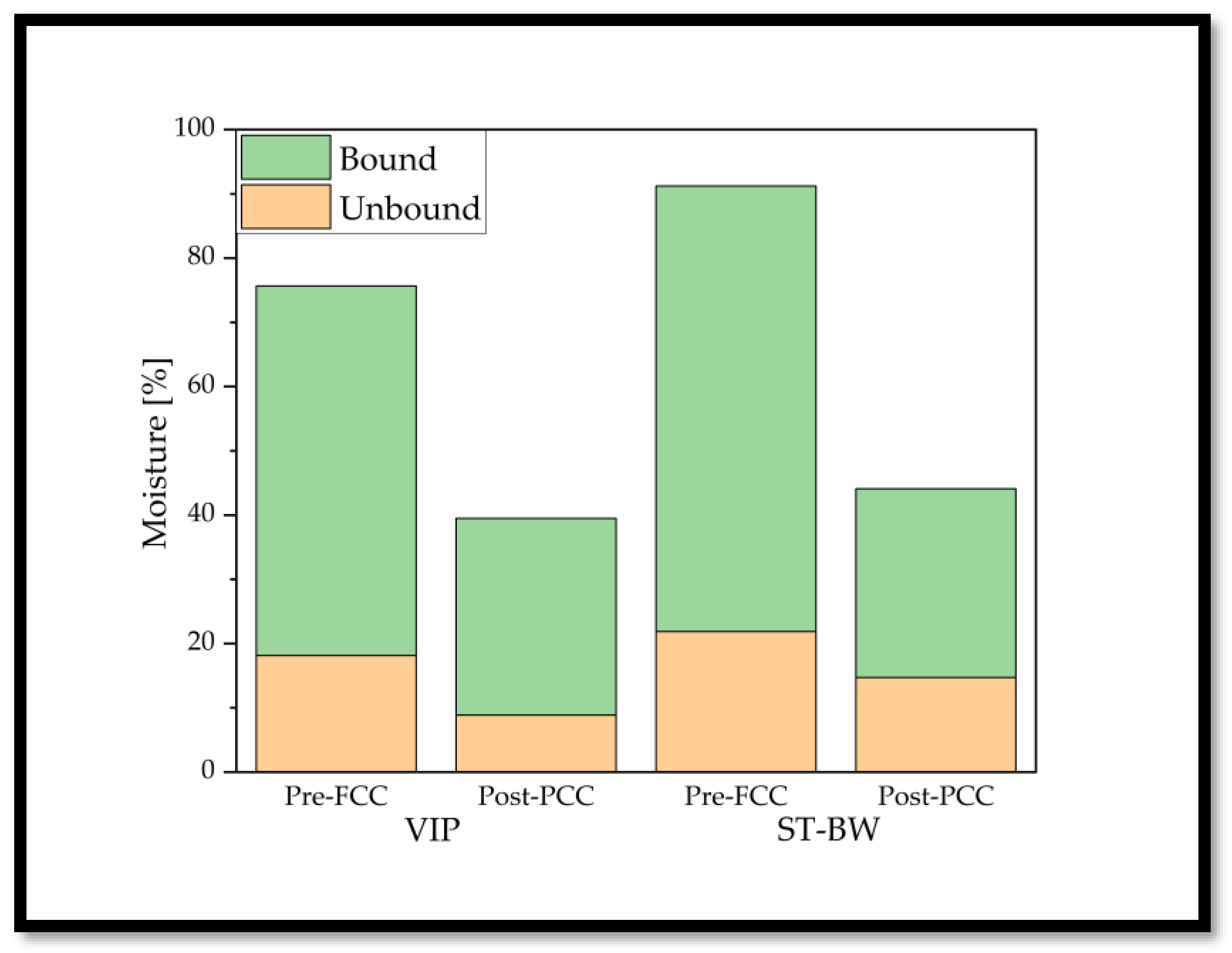

The thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of the raw sample and the compressed sample presented the moisture removal data (

Figure 9). The slope of the TGA results provide the derivative thermogravimetric analysis (DTG) curve, which represents the rate of change of weight of the sample as a function of time [

24]. From the DTG curves of VIP and ST-BW, the rate of change of weight peaks at around the same time (7.5 min) for both the sludges, and for both pre-FCC and post-FCC samples. After the peak rate change, the remaining moisture in the sludge was bound moisture. Thus, the corresponding loss of weight of the moisture at the peak of the rate change gives the unbound moisture content (before the peak) and the remaining moisture was bound moisture content (after the peak). It was interesting to note that post compaction, there was still unbound moisture present.

There was significant removal of moisture in the FCC, 36.15% of moisture removed in the VIP sludge and 47.11% of moisture removed from the ST-BW sludge. Surprisingly, major part of this moisture was from the bound moisture, and it was mostly the interstitial moisture (

Figure 10). The unbound moisture reduction was by 7.16-9.27% whereas the bound moisture removal was 26.88-39.96%. This corresponded to the interstitial moisture content of the samples which was 22.29% for VIP and 39.36% for the ST-BW samples. The interstitial moisture from the bound moisture fraction was “pushed” out from the capillaries by the compressive force. If the compression approach of moisture removal can help remove most of the interstitial moisture, the challenges of the sticky phase of the sludge in other solid-liquid separation approaches can perhaps be overcome or reduced to a larger extent.

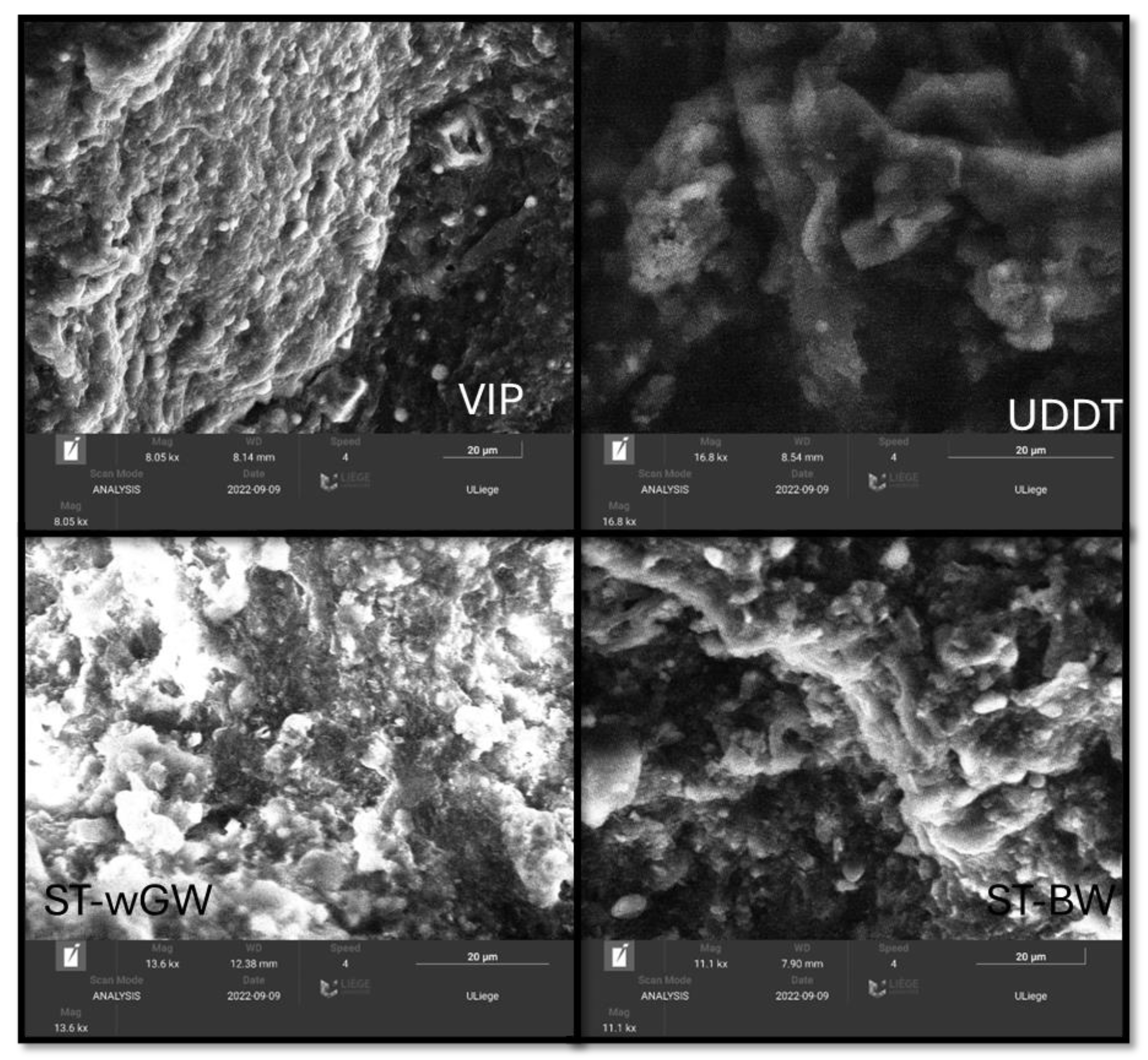

3.9. Environmental Scanning Electron Microscopy

The environmental scanning electron microscope (ESEM) imagery at 20 µm provided details of the micro-surface of the sludge particles (

Figure 11). The micro-structure of raw FS samples was heterogeneous in nature with some degree of compactness with some degree of porosity. The unattached particles seem to be adhesive to the surface, demonstrating the presence of a structured EPS. The cohesive strength of the sludge was evident from the high number of active sites which aided in moisture retention and binding small grain particles. The micrograph from ESEM can be used as a reference for inevitable structural disruptions encountered in SEM methods. The sludge surface was rough with the presence of dent-like formations. This could also be due to the release of internal forces from the sludge surface exposed to the electron beam. This is a limitation of the ESEM approach, though not critical with the sludge sample analysis. A more detailed microstructural investigation is recommended since it plays a major role in determining the deformational response of the sludges to external stresses, the solid-solid particle interactions and the resistance of the sludge to shearing force [

59].

4. Conclusions

The mechanical properties of FS and its relation to the moisture retention characteristics is significantly important to efficient sludge handling systems in the context of its treatability and land application. FS are largely anaerobic digested sludge with almost stable state without any marked biological digestion taking place. The porosity of the sludges varied between 48% to 63% for the FS samples. The true density of FS was lower compared with soils but was in line with the range of specific gravity of solid values of other anaerobic sludges. The zeta-potential was negative, below 10mV with over 95% of the particles <1000 µm. The TB-EPS influenced the stability of the sludge, the highest being in the septic tank with greywater sample. More proteins than carbohydrates also ascertained the anaerobic conditioning of the sludge. The results of the textural properties using a penetrometer showed similar behaviour as that reported for sewage sludges.

The dynamic oscillatory measurements exhibited a firm but smaller linear viscoelastic behaviour of the sludges due to the change in EPS because of anaerobicity. The synchronized behaviour of G’ and G” suggest a structural evolution from a solid characteristic to a liquid property at around the 1% strain level, fitting well with the Herschel-Bulkley model. Compaction under a filtration-compression test results in the removal of both unbound and bound moisture from the sludges reducing the moisture content of the sludge from 91.20%-75.64% to 44.09%-39.49% respectively for ST-BW and VIP sludges. The moisture removed corresponds to the interstitial moisture content of the samples. If the compression approach of moisture removal can help remove most of the interstitial moisture, the challenges of the sticky phase of the sludge can perhaps be overcome or reduced to a larger extent. The microstructural investigation revealed presence of active sites which aided moisture retention.

The moisture retention behaviour of FS was evidently dependent on its mechanical properties. Influencing these mechanical properties can alter this retention behaviour. While compaction can result in the release of interstitial moisture, addition of a suitable coagulant would release vicinal moisture. Intra-cellular moisture, as observed by other researchers, can be removed only by application of heat. It is noteworthy to observe that the moisture retention behaviour of FS can be changed by altering the mechanical properties by pre-treating the FS by different methods. The mechanical properties of FS changed with its initial TS concentration, and the extent of anaerobic biological conditioning. While all the samples were anaerobic, the ST-wGW had very low TS and thus exhibited slightly different characteristics while the samples from VIP and UDDT were similar, followed by ST-BW almost falling in the same range.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, AR. and SS.; methodology, AR, JP and SS.; software, AR.; validation, AR. JP and SS.; formal analysis, AR and SP.; investigation, AR and SP.; resources, AR.; data curation, AR and SP.; writing—original draft preparation, AR and SP.; writing—review and editing, AL, JP and SS.; visualization, AR and SP.; supervision, JP and SS.; project administration, JP and SS.; funding acquisition, SS All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Water Research Commission, South Africa for funding this research. We also thank Ms. Melissa Ramtahal, discipline of pharmaceutical sciences, School of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa for her kind cooperation. Special thanks for Dr. Patricia Arlabosse and Dr. Martial Sauceau, RAPSODEE UMR CNRS 5302 Center, IMT-Mines, Albi, France for their kind cooperation and sharing their knowledge and expertise. Gratitude to Dr. Yadira Bajon Fernandez, and Ms. Tracy Mupinga, Bioresources Science and Engineering, Cranfield University, UK for their assistance to conduct the experiments in the Environmental Science and Technology Soil Laboratories at their university. We wish to also thank Dr. Edwina Mercer and Ms. Tanaka Chatema for their support and encouragement. SP and AL acknowledge the FRS-FNRS (Fund for Scientific Research) for their funding through the Research Project grant “T.0159.20-PDR” Sludge Drying vs Rheology.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- S. Diener et al., “A value proposition: Resource recovery from faecal sludge - Can it be the driver for improved sanitation?,” Resour. Conserv. Recycl., vol. 88, pp. 32–38, 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Semiyaga, M. A. E. Okure, C. B. Niwagaba, P. M. Nyenje, and F. Kansiime, “Dewaterability of faecal sludge and its implications on faecal sludge management in urban slums: Faecal sludge pre-treatment by dewatering,” Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol., vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 151–164, 2017, doi: 10.1007/s13762-016-1134-9. [CrossRef]

- M. Gold et al., “Cross-country analysis of faecal sludge dewatering,” vol. 3330, 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. J. Stone, E. I. Ekwue, and R. O. Clarke, “Engineering Properties of Sewage Sludge in Trinidad.” 1998.

- B. C. O’Kelly, “Mechanical properties of dewatered sewage sludge,” Waste Manag., vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 47–52, 2005, doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2004.08.003. [CrossRef]

-

Gold et al., “Locally produced natural conditioners for dewatering of faecal sludge,” vol. 3330, 2016. [CrossRef]

- G. R. Blake, “Bulk density,” Methods Soil Anal. Part 1 Phys. Mineral. Prop. Incl. Stat. Meas. Sampl., no. 4433, pp. 374–390, 2015, doi: 10.2134/agronmonogr9.1.c30. [CrossRef]

- P. Arlabosse et al., “Sludge,” in Handbook on Characterization of Biomass, Biowaste and Related By-products, A. Nzihou, Ed. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020, pp. 939–1083.

- M. Kusnierz and P. Wiercik, “Analysis of particle size and fractal dimensions of suspensions contained in raw sewage, treated sewage and activated sludge,” Arch. Environ. Prot., vol. 42, no. 3, pp. 67–76, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y. Wu, W. Wang, J. Wang, Z. Luo, and S. Li, “Effects of acid/alkaline pretreatment and gamma-ray irradiation on extracellular polymeric substances from sewage sludge,” Radiat. Phys. Chem., vol. 97, pp. 349–353, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Q. Dai et al., “Investigation on extracellular polymeric substances, sludge flocs morphology, bound water release and dewatering performance of sewage sludge under pretreatment with modified phosphogypsum,” Water Res., vol. 142, pp. 337–346, 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2018.06.009. [CrossRef]

- M. Christine, A. Sene, K. K. Zhanga, S. Penga, and Y. Zhanga, “Sludge dewaterability : The variation of extracellular polymeric substances during sludge conditioning with two natural organic conditioners,” J. Environ. Manage., vol. 251, no. April, p. 109559, 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109559. [CrossRef]

- S. fang Yang and X. yan Li, “Influences of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) on the characteristics of activated sludge under non-steady-state conditions,” Process Biochem., vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 91–96, 2009, doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2008.09.010. [CrossRef]

- X. Y. Li and S. F. Yang, “Influence of loosely bound extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) on the flocculation, sedimentation and dewaterability of activated sludge,” Water Res., vol. 41, no. 5, pp. 1022–1030, 2007. [CrossRef]

- G. P. Sheng, H. Q. Yu, and X. Y. Li, “Extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) of microbial aggregates in biological wastewater treatment systems: A review,” Biotechnol. Adv., vol. 28, no. 6, pp. 882–894, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Suzanne N.S., Food Analysis Laboratory Manual. 2010.

- FAO, Quality assurance for animal feed analysis laboratories. FAO Animal Production and Health Manual No. 14. 2011.

- Nzihou, Handbook on characterization of biomass, biowaste and related by-products. 2020.

- Y.-B. Pambou, “Influence du conditionnement et de la déshydratation mécanique sur le séchage des boues d’épuration.” Université de Liège, Liège, Belgique, 2016.

- Y. B. Pambou, L. Fraikin, T. Salmon, M. Crine, and A. Léonard, “Sludge dewatering and drying: about the difficulty of making experiments with a non-stabilized material,” Desalin. Water Treat., vol. 57, no. 30, pp. 13841–13856, Jun. 2016, doi: 10.1080/19443994.2015.1060534. [CrossRef]

- G. Agoda-Tandjawa, E. Dieudé-Fauvel, R. Girault, and J. C. Baudez, “Using water activity measurements to evaluate rheological consistency and structure strength of sludge,” Chem. Eng. J., vol. 228, pp. 799–805, 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. Mouzaoui, J. C. Baudez, M. Sauceau, and P. Arlabosse, “Experimental rheological procedure adapted to pasty dewatered sludge up to 45 % dry matter,” Water Res., vol. 133, pp. 1–7, 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2018.01.006. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang et al., “Optimizing and understanding the pressurized vertical electro-osmotic dewatering of activated sludge,” Process Saf. Environ. Prot., vol. 140, pp. 392–402, 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.psep.2020.05.016. [CrossRef]

- W. Deng, X. Li, J. Yan, F. Wang, Y. Chi, and K. Cen, “Moisture distribution in sludges based on di ff erent testing methods,” J. Environ. Sci., vol. 23, no. 5, pp. 875–880, 2011, doi: 10.1016/S1001-0742(10)60518-9. [CrossRef]

- S. Li, C. Wang, X. Zhang, L. Zou, and Z. Dai, “Classification and characterization of bound water in marine mucky silty,” 2019.

- L. Olboter and A. Vogelpohl, “Influence of particle size distribution on the dewatering of organic sludges,” Water Sci. Technol., vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 149–157, 1993, doi: 10.2166/wst.1993.0037. [CrossRef]

- M. Karczmarek and J. Gaca, “Effect of two-stage thermal disintegration on particle size distribution in sewage sludge,” Polish J. Chem. Technol., vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 69–73, 2013, doi: 10.2478/pjct-2013-0047. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R. Suryakumar, E. Mercer, J. Pocock, and S. Septien, “Determination of Unbound-Bound Moisture Interface of Faecal Sludges from Different On-Site Sanitation Systems,” 2024.

- S. Cetin and A. Erdincler, “The role of carbohydrate and protein parts of extracellular polymeric substances on the dewaterability of biological sludges,” Water Sci. Technol., vol. 50, no. 9, pp. 49–56, 2004, doi: 10.2166/wst.2004.0532. [CrossRef]

- R. Marsalek, “Particle size and Zeta Potential of ZnO,” in ICBEE 2013: September 14-15, New Delhi, India, 2013.

- S. Comte, G. Guibaud, and M. Baudu, “Effect of extraction method on EPS from activated sludge: An HPSEC investigation,” J. Hazard. Mater., vol. 140, no. 1–2, pp. 129–137, 2007, doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2006.06.058. [CrossRef]

- 32. S. Peng, A. Hu, J. Ai, W. Zhang, and D. Wang, “Changes in molecular structure of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) with temperature in relation to sludge macro-physical properties,” Water Res., vol. 201, no. February, p. 117316, 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Peng, F. Ye, and Y. Li, “Investigation of extracellular polymer substances (EPS) and physicochemical properties of activated sludge from different municipal and industrial wastewater treatment plants,” Environ. Technol., vol. 33, no. 8, pp. 857–863, 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. I. Houghton, J. Quarmby, and T. Stephenson, “Municipal wastewater sludge dewaterability and the presence of microbial extracellular polymer,” Water Sci. Technol., vol. 44, no. 2–3, pp. 373–379, 2001, doi: 10.2166/wst.2001.0792. [CrossRef]

- Léonard, G. Blandin, and M. Crine, “Importance of Rheological Properties When Drying Sludge in a Fixed Bed,” Lab. Chem. Eng. Univ., vol. III, no. Kudra, pp. 102–150, 2014.

- Fantasse, S. Parra Angarita, A. Léonard, E. K. Lakhal, A. Idlimam, and B. El Houssayne, “Rheological Behavior and Characterization of Drinking Water Treatment Sludge from Morocco,” Clean Technol., vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 259–274, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Li, F. Wang, Y. Chi, and J. H. Yan, “Adhesion and Cohesion Characteristics of Sewage Sludge During Drying,” Dry. Technol., vol. 32, no. 13, pp. 1598–1607, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Hil, E. Judenne, and M. Remy, “The effect of lime treatment on sludge rheological properties,” Technology, no. November, pp. 1–6, 2005.

- T. Mezger, The Rheology Handbook. 2020.

- N. H. Rodríguez et al., “Re-use of drinking water treatment plant (DWTP) sludge: Characterization and technological behaviour of cement mortars with atomized sludge additions,” Cem. Concr. Res., vol. 40, no. 5, pp. 778–786, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu et al., “Utilization of drinking water treatment sludge in concrete paving blocks: Microstructural analysis, durability and leaching properties,” J. Environ. Manage., vol. 262, no. November 2019, p. 110352, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Dignac, P. Ginestet, D. Rybacki, A. Bruchet, V. U.-W. research, and undefined 2000, “Fate of wastewater organic pollution during activated sludge treatment: nature of residual organic matter,” Elsevier.

- Y. P. Ling et al., “Evaluation and reutilization of water sludge from fresh water processing plant as a green clay substituent,” Appl. Clay Sci., vol. 143, no. December 2016, pp. 300–306, 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.clay.2017.04.007. [CrossRef]

- H. Li, S. Zou, and C. Li, “Liming Pretreatment Reduces Sludge Build-Up on the Dryer Wall during Thermal Drying,” Dry. Technol., vol. 30, no. 14, pp. 1563–1569, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Léonard, S. Royer, G. Blandin, T. Salmon, L. Fraikin, and M. Crine, “IMPORTANCE OF MIXING CONDITIONS DURING SLUDGE LIMING PRIOR TO THEIR CONVECTIVE DRYING,” no. October, pp. 26–28, 2011.

- Y. Huron, T. Salmon, M. Crine, G. Blandin, and A. Léonard, “Effect of liming on the convective drying of urban residual sludges,” Asia-Pacific J. Chem. Eng., vol. 5, no. 6, pp. 909–914, Nov. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Benlalla, M. Elmoussaouiti, M. Cherkaoui, L. Ait Hsain, and M. Assafi, “Characterization and valorization of drinking water sludges applied to agricultural spreading,” J. Mater. Environ. Sci., vol. 6, no. 6, pp. 1692–1698, 2015.

- Y. Malkin, S. R. Derkach, and V. G. Kulichikhin, “Rheology of Gels and Yielding Liquids,” Gels, vol. 9, no. 9, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Ruiz and C. Wisniewski, “Correlation between dewatering and hydro-textural characteristics of sewage sludge during drying,” Sep. Purif. Technol., vol. 61, no. 2, pp. 204–210, Jul. 2008. [CrossRef]

- J. Jiang, J. Wu, S. Poncin, and H. Z. Li, “Rheological characteristics of highly concentrated anaerobic digested sludge,” Biochem. Eng. J., vol. 86, pp. 57–61, 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhang et al., “Analysis of the relationship of extracellular polymeric substances to the dewaterability and rheological properties of sludge treated by acidification and anaerobic mesophilic digestion,” J. Hazard. Mater., vol. 369, no. October 2018, pp. 31–39, 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. Feng, Z. Hu, H. Ma, T. Bai, Y. Guo, and Y. Hao, “Semi-solid rheology characterization of sludge conditioned with inorganic coagulants,” Water Sci. Technol., vol. 80, no. 11, pp. 2158–2168, 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. Sollich and P. Sollich, “Chapter 5 SOFT GLASSY RHEOLOGY,” Rheology, pp. 161–192, 2006.

- J. Vaxelaire and J. Olivier, “Conditioning for municipal sludge dewatering. From filtration compression cell tests to belt press,” Dry. Technol., vol. 24, no. 10, pp. 1225–1233, 2006. [CrossRef]

- P. J. Scales, D. R. Dixon, P. J. Harbour, and A. D. Stickland, “The fundamentals of wastewater sludge characterization and filtration,” Water Sci. Technol., vol. 49, no. 10, pp. 67–72, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Wu, X. Dai, and X. Chai, “Critical review on dewatering of sewage sludge: Influential mechanism, conditioning technologies and implications to sludge re-utilizations,” Water Res., vol. 180, p. 115912, 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.115912. [CrossRef]

- M. Raynaud, J. Vaxelaire, J. Olivier, E. Dieudé-Fauvel, and J. C. Baudez, “Compression dewatering of municipal activated sludge: Effects of salt and pH,” Water Res., vol. 46, no. 14, pp. 4448–4456, 2012. [CrossRef]

- J.-C. Raynaud, M., Vaxelaire, J., Heritier, P., & Baudez, “Activated sludge dewatering in a filtration compression cell: deviations in comparison to the classical theory,” Technology, vol. 7, no. 17, pp. 743–753, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Lin and A. B. Cerato, “Applications of SEM and ESEM in microstructural investigation of shale-weathered expansive soils along swelling-shrinkage cycles,” Eng. Geol., vol. 177, pp. 66–74, 2014. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).