1. Introduction

The generation of e-waste has increased exponentially in recent years. This fact raises concerns about how to tackle this problem and, in particular, how to improve its management. Management begins with consumer awareness of the circular economy and ends with efforts to recover and recycle the raw materials previously used to manufacture these devices [

1]. However, the production of these appliances is constantly increasing (annual growth of approximately 5%) [

2] while their lifespan is decreasing, resulting in the depletion of reserves of these metals in the Earth's crust, making their conservation a matter of particular concern [

3,

4]. Environmental protection is linked to the consumption of electricity, the protection of reserves, air pollutants and the deposit of waste in the earth's crust [

5]. The circular economy and the recycling of waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE) can support these factors in two ways. Firstly, by reducing the energy and water used in the stages from natural extraction to raw material production, as recovering metals from WEEE can save up to 85-90% of the energy required to extract them from natural mines [

6,

7]. Both the energy and water consumption and the environmental footprint of their production are a function of each metal [

7], which creates more incentives for mapping critical raw materials and metals of high economic value on e-waste to achieve their targeted recycling [

8]. Secondly, by preventing the uncontrolled deposition of toxic elements in the earth's crust [

9], since the circular economy aims to minimise the amount of WEEE buried and, because of this limitation, follows a priority order of elimination, reduction, reuse and recycling, with any remaining waste disposed of in an environmentally sound and controlled manner [

10].

WEEE is therefore a valuable secondary source of specific materials and elements, such as rare earth elements (REEs) and precious metals (PMs), which can contribute to the balance between reserves and demand, especially for metals classified as critical, as the concentration of metals in WEEE is higher than that found in the Earth's crust [

11]. Rare earths and precious metals have been and continue to be widely used in electrical and electronic equipment due to their exceptional properties [

12,

13]. Rare earths are a group of 17 metallic elements in the periodic table, including the Lanthanide series (lanthanum (La) to lutetium (Lu)), scandium (Sc) and yttrium (Y). Scandium and yttrium are included in the REEs because of their similar physico-chemical properties and their tendency to occur in the same ores. Precious metals include the platinum group metals (PGMs), gold (Au) and silver (Ag) [

14,

15]. Efforts to recover and recycle metals for sustainability make the management of WEEE a crucial factor, and the pre-treatment phase is a critical stage of recycling, during which the concentrations of metals classified as critical or of high economic interest can vary significantly [

16,

17]. To increase the recovery efficiency of rare earth elements, precious metals and critical raw materials (CRMs) from e-waste, it is necessary to separate their structures [

18,

19]. It is critical to consider separation during the pre-treatment stage, as this can significantly affect the retention or loss of the aforementioned metals, especially in cases where concentrations are low [

20]. To further improve the level of recovery, it may even be helpful to remove or cut out specific parts of their individual structures that have high concentrations of specific metals. This is typical for PMs (such as electrical contacts, electrodes and electrical interconnects), but not usually for REEs, which are used in a variety of applications (such as phosphors and ceramics) with a diffuse presence in the individual structures of the device [

21]. The categorisation of WEEE varies between different regulations and directives in different countries or continents [

22]. According to the European Union Directive 2012/19/EU [

23], WEEE is divided into six categories. Each category consists of several types of equipment. Category 3 covers lamps and in particular lamp technologies: a) high intensity discharge (HID), b) fluorescent, and c) light emitting diode (LED). Each subcategory of the above technologies, covers different types of lamps, which may vary in size, application, and electrical and photometric characteristics. It is important to note that, LED lamps that have reached the end of their functional life may be classified as hazardous e-waste, especially if they are grouped with fluorescent lamps at recycling collection points, due to the risk of contamination by the mercury (Hg) contained in fluorescent lamps. Separate collection of lamps based on their operating principles is therefore required [

24].

LED lamps are solid-state energy converters. In the design and manufacturing process of LED lamps, a large number of simple or more complex raw materials are used, some of which (toxic heavy metals) can be harmful to both the environment and humans during the lamp manufacturing process. Therefore, ‘’green design’’ of electrical and electronic equipment (EEE) and ‘’design for environment’’ are excellent parameters for both EEE design and WEEE recycling [

25]. LED lamps are up to 95% recyclable, but their complex construction requires disassembly and separation of individual structures and components to be sent to separate recycling streams [

19]. LED lamps are a new type of electronic waste for which there are currently no standardised recycling processes [

26]. As the name of the technology suggests, these lamps use LEDs of different technologies and photometric parameters to generate their luminous flux. The use of LEDs to generate luminous flux offers significant advantages over the two older lighting technologies -incandescent and fluorescent-, relating to (a) the ease with which their geometric dimensions can be adapted to the challenges posed by the requirements of each lighting application [

27], (b) their reduced heat generation, (c) their improved efficiency (lm W

-1) and (d) the absence of mercury in their structure, making them more environmentally friendly both for the environment and for workers in recycling plants [

28,

29]. LEDs are classified as e-waste under European Union Directive 2012/19/EU [

23]. Surface Mount Device (SMD) LEDs are a particularly interesting e-component for targeted recycling due to the presence of rare earth elements and precious metals in their structure [

30], with the concentrations of these metals varying as a function of their correlated colour temperature [

31]. The collection, management and recovery of the stored potential of the materials used in the manufacture of lamps contributes to the implementation of the concept of “urban mining”, the protection of the environment through natural reserves by reducing mining [

32], as well as elements hazardous to humans and the environment, such as various flame retardant substrates, and elements such as lead and arsenic [

33,

34]. A balance between the content, price and criticality of these materials will determine the viability of “urban mines” and recycling plants [

35]. To achieve the above, characterisation results are needed on: (a) the total and individual masses of LED lamps, (b) the localisation of the above metals in their structure, (c) their concentrations per component type, and (d) the modulation of their concentrations at the device level.

1.1. LED Lamps

In order to achieve zero energy buildings (ZEB) or, more realistically, near-zero energy buildings (n-ZEB), it was considered necessary to reduce the electricity consumption in buildings. To this end, LED lamps were introduced in 2010 to replace incandescent and fluorescent technologies used for residential lighting, due to their significant advantages over the above technologies [

36,

37,

38]. Compared with previous lighting technologies, LED lamps convert electrical energy into visible light more efficiently and with a faster response time (on/off switching in the ms-level) [

39,

40,

41], making them a safer and more environmentally friendly technology [

42,

43,

44,

45]. Their more efficient operation is expected to reduce the share of global electricity consumption corresponding to artificial lighting [

39,

46] (18 - 21)%, of which a significant part (8%) is consumed in residential buildings [

40,

47], and thus contribute to the reduction of carbon emissions (10%) corresponding to the production of the aforementioned electricity [

28,

33,

41,

48]. The proper management of artificial lighting is not limited to the context of electricity consumption, but extends to the collection and management of this specific e-waste, setting objectives, among others, related to the management of hazardous substances contained in the lamps and the study of: (a) the re-use of their structures and components [

40,

47], and (b) the possibility of recovering elements of the periodic table, either accompanied by a high economic value or classified as CRMs.

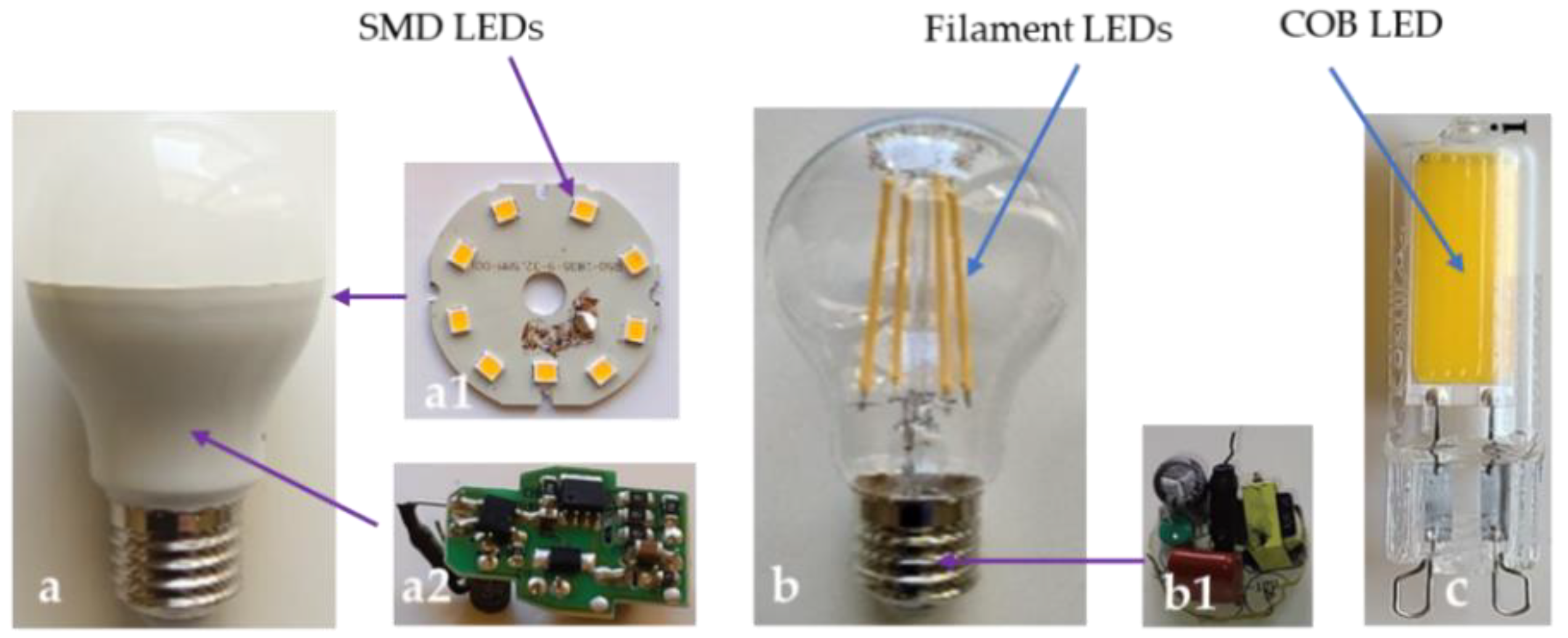

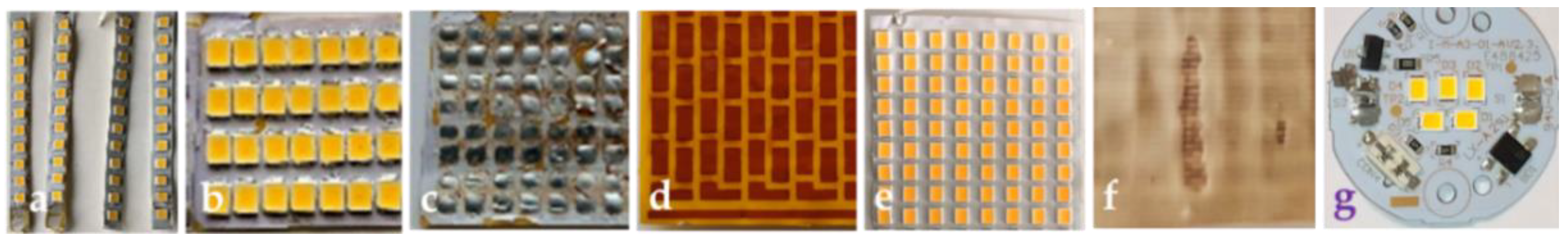

LED lamps are more complex in design than the previous lighting technologies [

49]. It is worth noting that 96 simple or more complex raw materials [

25,

50], including REEs and PMs, are used in the design and manufacturing process of LED lamps and are located in their specific structures, such as in: a) LED modules (

Figure 1a1), b) surface mount device (SMD) LEDs (

Figure 1a1), c) filament LEDs (

Figure 1b), and chip on board (COB) LEDs (

Figure 1c), as well as in the structures required for their operation (drivers) (

Figure 1a2, 1b1) depending on the LED technology used by each type of lamp [

30,

51]. The presence of these metal categories in LED lamps, the high market share of LEDs in the building lighting sector compared to other sectors such as automotive lighting, landscape lighting, display, backlighting applications, signalling and guidance, etc., and the high level of recovery of these metals, make this e-waste a significant and highly concentrated secondary source for the recovery of valuable and CRMs [

19,

21,

33,

52,

53,

54].

Where economically viable, LED lamps shall be disassembled into their individual structures and their components shall be released for more efficient management during lamp recycling, which can be achieved in several stages. In the first stage, LED lamps can be dismantled by first producing the following mass fractions or parts thereof, depending on their type and construction: (a) metals, (b) plastics, (c) glass, (d) ceramics, (e) drivers, (f) LED modules, and (g) filament LEDs. In the second stage, drivers can be separated into their electronic components and bare printed circuit board (PCB), while the LED module can be separated into its SMD LEDs and bare LED module. At this stage, any hazardous components requiring special handling, such as the driver's electrolytic capacitors, can be removed. Separation of structures and components on the basis of functionality is not applicable unless power surges cause premature damage to the lamp. Selective removal of components of high economic interest can be applied even after lamp separation. For example, in the case of LEDs, it is important to extract and create simple compositions and high concentration streams that reduce losses and improve the recovery rate of valuable and critical raw materials. This supports the sustainability of recycling facilities and helps to achieve the best possible balance between the economic benefits of recycling and the environmental impacts of recycling processes [

20,

24,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61]. As an indication, (

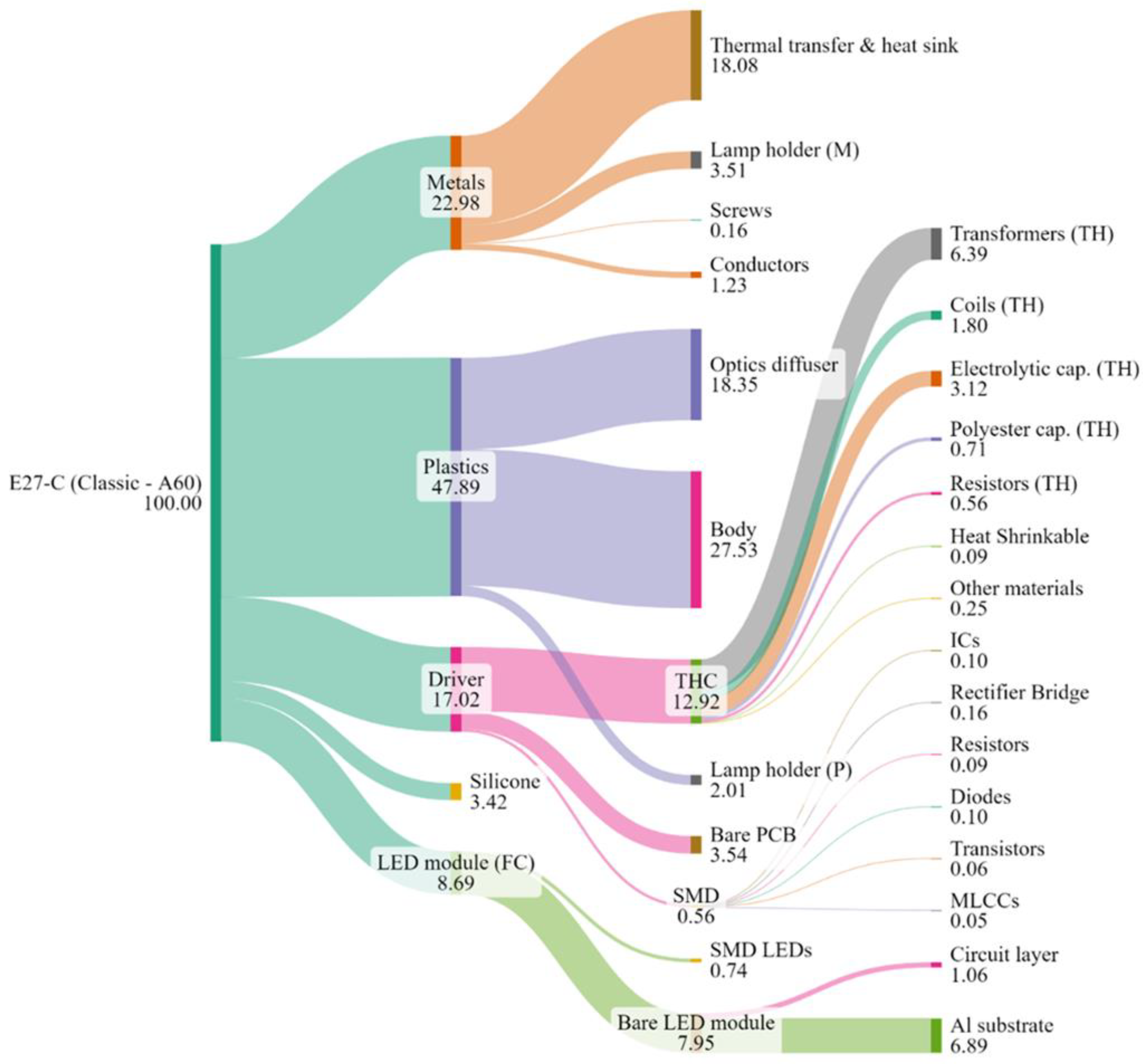

Figure A1) shows a detailed average percentage analysis of the individual components of the most common LED lamp used in residential lighting applications (E27-C Classic - A60) in relation to the total mass of the lamp.

1.1. SMD LEDs

LEDs are static electricity converters and are manufactured using microelectronic technology [

39] adapted to the specific technological challenges of their operation in terms of the radiation they emit and the management of the heat they generate [

27,

62,

63]. Unlike the heated filament of incandescent lamps and microlamps [

64], their operation is based on the spontaneous emission of radiation from the recombination of redundant holes and electrons as a result of the potential difference and the flow of electric current when they are correctly polarised [

65]. Depending on the radiation emitted, and in particular the dominant emission wavelength, LEDs can be classified as ultraviolet LEDs (UV-LEDs) < 380 nm, visible LEDs (V-LEDs) (380 - 780) nm and infrared LEDs (IR-LEDs) > 780 nm [

66]. When LEDs are used in general or specific lighting applications, their structure is designed to convert electrical energy into light radiation. LEDs began their commercial presence in the 1960s, usually as indicator lights, but their substantial presence in the lighting sector began in 2014 with the discovery of the "blue LED" [

67].

Various types of SMD white LEDs are used in lighting applications, such as general lighting lamps, display lighting and various other technological applications where the presence of luminous flux is required [

68,

69]. Their use is accompanied by their advantages such as: a) energy efficiency [

69], b) photometric characteristics and fast response [

70], c) long operating life [

69], d) absence of mercury [

69], and e) soldered in predetermined positions on printed circuit boards for various technological applications [

71] according to the desired polar distribution of the luminous flux. Their type is determined by the external dimensions of their structure. For example, the 2835 type has dimensions of 2.8mm (h) x 3.5mm (w), while type 3528 has dimensions of 3.5mm (h) x 2.8mm (w).

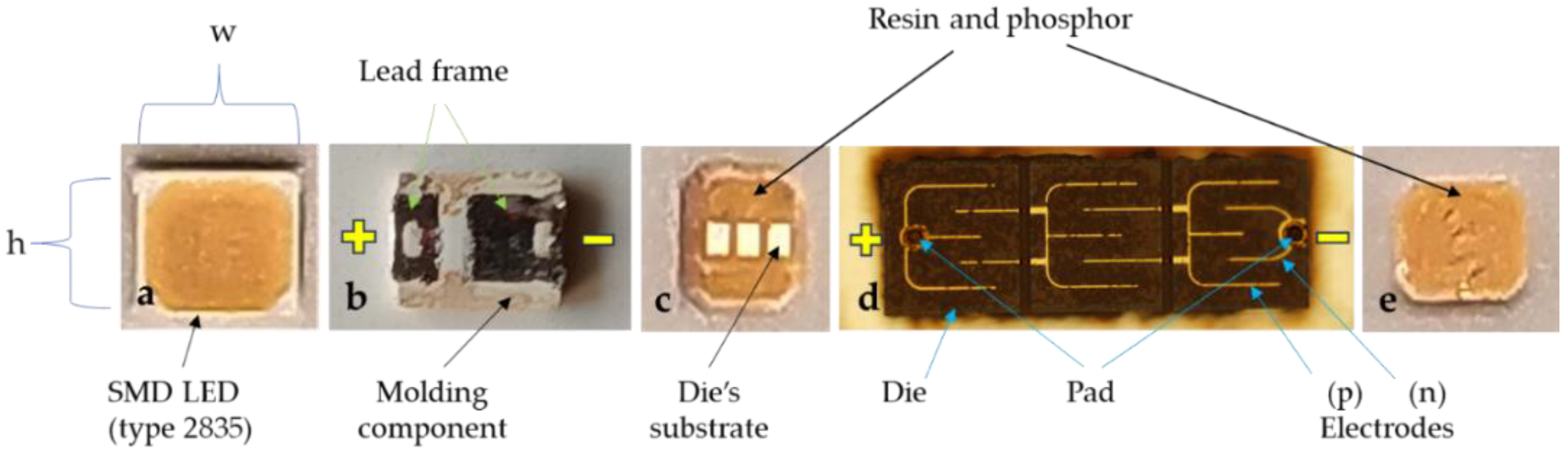

The structure of an SMD LED (

Figure 2a) consists of several individual structures, each of which can be made of different materials depending on the application [

27,

30]. From base to top, an SMD LED consists of the following individual functional structures: (a) lead frame -external power supply contacts- (

Figure 2b), (b) molding component -plastic case- (

Figure 2b), (c) die’s substrate (rear view) (

Figure 2c), (d) LED dies (top view) -structure for generating electromagnetic radiation- (

Figure 2d), and (e) silicone or epoxy resin containing phosphor (

Figure 2e) [

72,

73,

74]. According to Hamidnia et al. (2018) and Alim et al. (2021), in the production of SMD LEDs, sapphire, silicon carbide and silicon are used as substrate materials for LED chips, selected according to economic criteria for each LED application [

27,

63]. According to Marwede et al. (2012) and (Nikulski et al., 2021), the concentrations of CRMs and PMs in SMD LEDs can be expressed as a function of the surface area of the dies (mg kg

-1 per 1 mm

2) [

75,

76]. According to Marwede et al. (2012) [

75], Cenci, Dal Berto, Schneider, et al. (2020) [

77], and (Nikulski et al., 2021) [

76], there is a significant difference in the total die area per LED lighting product depending on the lighting application.

With the exception of the flip-chip structure, conductive wires are used for the electrical supply of the dies [

63]. The wire bonding process is a critical parameter of the overall LED structure and it aims to transfer the electrical energy to the die(s) by connecting their electrical contacts (pads) to the external contacts of the package (lead frame), as in the case of integrated circuits [

27,

69] using microelectronic technology (wire border) [

27,

78]. In general, microelectronic technology uses different types of conducting wires, such as: (a) single structure (solid), (b) alloys, and (c) overlay (superimposed layers) (e.g. Cu-Pd [

63,

79], Ag-Pd [

63]). In the manufacture of their various types, base and precious metals are used to address challenges [

80] related to electrical and thermal conductivity, mechanical strength, performance and manufacturing cost. To meet these challenges [

81], precious metals such as silver, palladium and gold have been used to produce, for example, "palladium-coated copper wire with a flash-gold layer" (PCA) [

82] or Pd-coated Cu wires [

80,

83] or Ni [

83]. When selecting the type and composition of the wire, the following parameters of SMD LEDs are taken into account, among others: a) the construction material of the die pads [

63,

78], the correlated colour temperature (CCT) [

63,

84], and the warranty time for good operation [

85]. To reduce the cost of manufacturing SMD LEDs, the trend is to use wires with a reduced gold content of 20-40% and an increased silver content, taking advantage of the significant difference in the commercial price of these two metals to create silver alloy (Ag alloy) wires [

84]. All three types of wire are used in LEDs, in particular: (a) solid [

85,

86] Au, Ag, Cu, (b) alloys [

85,

86], and(c) coated: Gold coated silver bonding wire [

87], Pd coated copper bonding wire [

87], Ag (96%) as base – Pd (3%) as palladium coating – and Au (1%) as gold flash [

88], Ag - Au (8–30)% - and Pd (0.01–6)% [

63,

89].

1.1.1. Wight Light Production

The production of white light for use in general or specific lighting applications can be achieved by different manufacturing combinations of the LED structure [

90]. The first combination requires the precise synthesis of phosphors of the three basic colours red (R), green (G) and blue (B) excited by radiation of a specific wavelength or region of the electromagnetic spectrum (usually near ultraviolet) [

91], most commonly produced by independent semiconductor structures of LEDs (dies) [

92,

93]. The generation of white light by the aforementioned synergy is characteristically referred to as a “colour mixing white LED” (CMW-LED) [

94]. The second and currently most common technological combination for producing white light is the combination of one or more semiconductor structures emitting in the “cold” region of the visible part of the electromagnetic spectrum (455 nm) with the presence and excitation of a yellow phosphor [

63,

90]. This optical/material synergy, characteristically called a “Phosphor-Converted White LED” (PC-WLED), contributes to its emission spectrum [

28,

63,

95,

96,

97]. The high energy efficiency of this technology makes these LED structures suitable for use in artificial lighting applications (lamps, luminaires, etc.) [

98].

White LEDs are the fourth generation of solid-state lighting (SSL) with the advantages of high luminous efficacy (lm W

-1) and long life. Combining these advantages, white LEDs are generally considered to be more environmentally friendly, helping to reduce carbon emissions and conserve natural resources [

29]. However, an important challenge in designing LEDs for optimal use is to improve some of their photometric parameters, such as the correlated colour temperature and colour rendering index (CRI) [

99]. For example, yellow phosphors, due to the absence of “warm” wavelengths, produce correlated colour temperatures ≥ 4500 K accompanied by a low colour rendering index and do not meet the photometric requirements of the room in most artificial lighting applications [

45,

46,

90,

100]. The technological shift of the CCT of the luminous flux, from “cool” to “warm” wavelengths, can be achieved by various technological combinations, while keeping the same excitation radiation of the phosphors (near UV or blue LED) per application case [

101], such as (a) the use of resins of appropriate composition and variable thickness, enriched with the appropriate phosphor impurities and concentrations for each application, and (b) resin layers with the appropriate yellow and red phosphor impurities to meet the photometric requirements specified for each artificial lighting application [

45,

65,

92,

101,

102].

1.1.1. Presence of REEs in Inorganic Phosphors

The participation of REEs in the inorganic phosphors used in the production of SMD LEDs modulates the parameters of SMD LEDs in terms of their functional stability, luminous efficiency (lm W

-1), CRI and CCT, thus meeting the requirements of each lighting application [

29,

91,

103]. In general, inorganic phosphors are composed of the “host lattice” and the “activator(s)” [

104,

105]. The presence of REEs in the chemical types of inorganic phosphors is associated either with their participation in the host lattice or with a low participation (~1 mol%) as activators [

106], while their dual presence (host lattice & activator) is not excluded [

107]. As mentioned above, the presence of REEs in inorganic phosphors modulates their emitted spectrum. In the case of LEDs for lighting applications, their emission spectrum is an optical mixture of the radiation produced by the phosphor excitation diode(s) and the radiation produced during phosphor de-excitation [

100,

108,

109,

110]. The contribution of these two visible radiations to the luminous flux of LEDs determines their important photometric parameters such as CCT and CRI [

65,

111]. For the precise synthesis of the generated radiation and the wide range of LEDs, more than one rare earth ion (up to 3) can be used as phosphor activators (dopant and co-dopant) [

99,

104], whose ratios and concentrations cooperate in the desired modulation of their luminous flux [

112], since each rare earth ion contributes differently to its modulation [

92,

109,

112].

1.1. SMD LEDs—A Special Type of E-Waste

From a recycling point of view, SMD LEDs are of particular interest due to the presence and concentration of REEs and PMs in their structure [

30]. Of particular interest, however, is the fact that this surface-mounted electrical component modulates the presence of REEs in LED lamps to a high percentage or exclusively as a function of the presence or absence of multi-layer ceramic capacitors (MLCCs) in its structure, since this type of capacitor, like LEDs, contains REEs [

20,

61,

113]. According to Sideris et al. (2023), MLCCs were not consistently present in the drivers of most of the lamp types they examined [

61]. According to Charles et al. (2020) [

20] and Xia et al. (2024) [

113], and in contrast to the above components, other electrical and electronic components contained in drivers (typical design), such as transistors, tantalum (Ta) capacitors, electrolytic capacitors, resistors, inductors, integrated circuits, diodes, piezoelectrics, crystals, resonators, sockets, pin terminals, heat sinks and bare boards, do not contain REEs in their structure. According to Cenci, Dal Berto, Schneider, et al. (2020) [

77] and Cenci, Dal Berto, Castillo, et al. (2020) [

51], the presence of REEs in the LED lamps they studied was essentially related to the presence of LEDs. In general, the structure of lamp drivers is a function of both their design technology and the electrical power of the lamps. These two parameters are of particular interest both from the recycling point of view (stored potential of REEs and PMs) and from the point of view of electrical power quality (lamp power factor) [

114]. Based on the above, it is clear that the presence of REEs in the structure of LED lamps for residential applications is essentially linked to the presence of SMD LEDs.

1.1.1. Characterisation of SMD LEDs for the Presence of REEs and PMs—Literature Review

LED lamps are a new technology for lighting buildings. LED lamps with SMD LEDs, started with an extremely low penetration rate in 2010 and the aim is to reach 100% of the market by 2025. Considering that (a) there are not many relevant studies on their recycling due to their short presence and long lifetime, (b) they are a more complex structure than the previous technologies, (c) a large number of raw materials are used in the production of LED lamps [

50] many of which are accompanied by the supply risk (SR) and economic importance (EI) indicators [

53], and (d) the recycling of their individual units, such as SMD LEDs, is directed to specialised recycling plants, it seems appropriate to divide the characterisation of the structures and their components in order to provide targeted data that will contribute to a better design of their recycling (separation) and a more efficient recovery of CRMs and valuable elements, such as REEs and PMs [

73,

77,

113,

115,

116,

117].

The following is a list of studies which are relevant to the characterisation of this specific type of e-waste. Zhan et al. (2015) presented characterisation results on the structure and dies of SMD LEDs, which are affected by the presence of PMs (Au) [

118]. DODBIBA et al. (2019) conducted a study on an E27-type LED lamp with a power of 30 W. The study provided results on the percentages of the lamp structures, including the driver and the LED module. In addition, they reported characterisation results related on the structure of SMD LEDs (type 5050) from E27 lamp due to the presence of PMs (Ag, Au) and the presence of REEs (Y) [

119]. Cenci, Dal Berto, Schneider, et al. (2020) characterised SMD LEDs from LED lamps (tube and E27) and present results for the concentrations of base metals, technology metals, REEs and PMs in relation to the driver, LED modules and SMD LEDs [

77]. Zhan et al. (2020) presented the results of the characterisation of the structure of SMD LEDs (type 3528) affected by the presence of PMs (Ag) [

120]. Cenci, Dal Berto, Castillo, et al. (2020) studied four groups of LED lamps, including L1 (T12 tube) and L2–L4 (bulbs) (E27). Each group of ten lamps was corresponded to a different manufacturer. The researchers reported the characterisation results for REEs (Y, Ce) and PMs (Ag, Au). The characterisation results include drivers, bare LED modules, and the SMD LEDs contained in the above mentioned lamps [

51]. Oliveira et al. (2020) presented the results of their study on the structural characterisation of SMD LEDs (type 2835) in the presence of REEs (Y, Ce, Gd) and PMs (Ag) [

73]. Balinski et al. (2022) conducted a study on 100 LED lamps with Edison lamp bases. The lamps separated into five basic structures, including LED modules and drivers. The authors present results from the characterisation of dies and encapsulation from SMD LEDs for the presence of REEs (Y, Eu, Gd), PMs (Pd, Ag, Au) and other elements from the periodic table [

30]. Vinhal et al. (2022) presented the results of their study on the structural characterisation of SMD LEDs (type 2835), “cool white” (CW) and “warm white” (WW), from LED tube lamps with respect to the presence of REEs (Y, Ce) and PMs (Ag, Au) [

31]. Pourhossein et al. (2022) studied end-of-life LEDs. Among other results, they present data on the presence of PMs (Ag, Au) in their structure [

26]. In their study, Mandal et al. (2023) present data on the potential of valuable metals in LEDs of different types and technologies, in particular for REEs (Y, Ce, and Gd) and PMs (Au, Ag) [

121]. Illés and Kékesi (2023) investigated four different E27-C lamps for professional lighting applications and present, among others, results for SMD LEDs regarding the presence of REEs (Ce, Eu and Y) and PMs (Ag, Au) [

122]. Zheng et al. (2024) investigated SMD LEDs (type 3528) from “strip lights”. Among other results, they present data on PMs (Ag) [

34]. The structure of the various types of SMD LEDs and the mapping of the critical, technological and valuable materials have been extensively studied and successfully presented in a number of studies, including the following: Tang et al. (2017) [

62], Zhang et al. (2018) [

123], Zhan et al. (2020) [

120], Martins, Tanabe, and Bertuol (2020) [

124], Cenci et al. (2020) [

51], Zhang, Zhan, and Xu (2021) [

125], Vinhal et al. (2022) [

31], Illés and Kékesi (2023) [

122].

Based on the above, considering that LEDs are e-waste and taking a more realistic approach from the recycling side, this study presents the following novelties: (a) the study of six different types of residential LED lamps (E27, E14, G9, R7S, GU10 and MR16) in terms of the mass content and type of SMD LEDs, (b) the characterisation of the collected SMD LEDs according to the correlated colour temperature and, in particular, for four similar cases based on 2700 K, 3000 K, 4000 K and 6500 K, with respect to the presence of REEs and PMs, (c) the conditional characterisation of the above mentioned types of LED lamps with respect to the REEs content in their structure, and (d) the conditional calculation of the stored potential of the PMs in the SMD LEDs of each of the above mentioned types of lamps.

2. Materials and Methods

A random sample and then a selectively enriched sample of LED lamps were examined. The random sample was provided by “AEGEAN RECYCLING-FOUNDRIES SA”.

The methodological approach used in this study included five stages: (1) collection and separation of LED lamps, (2) disassembly and testing, (3) sample preparation and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) analysis, and (4) calculation of the stored potential of the PMs in the SMD LEDs of the lamps and characterisation of the lamps in terms of REEs. All measurements were repeated three times under the same conditions and the results were averaged.

2.1. Collection and Separation

This stage consisted of: (a) collection, integrity check, cleaning, weighing, counting and separation of lamps by base type (E27, E14, etc.) and LED type (SMD, filament, and COB), (b) selection of unique lamps based on their electrical and photometric characteristics and brand, in order to generate innovative data on the lamps to be recycled according to users' preferences.

2.2. Disassembly and Testing

This stage involved: (a) manual disassembly of the unique lamps, (b) removal and dismantling of the LED modules, (c) weighing and counting of the individual masses and their correlation with the total and individual masses of the structures and components, and (d) recording of the number, and dimensions (type) of SMD LEDs.

The following equipment was used for the implementation of this stage: basic and special tools such as, tweezers, hot air-gun rated temperature (Brand: BOSCH; (Robert Bosch GmbH, Stuttgart, Germany) model: GHG 20-60), calibrated thickness gauge (Brand: UNIOR; (UNIOR Kovaška industrija d.d., Zreče, Slovenia) model: 271), calibrated micrometer (Brand: INSIZE; (INSIZE CO., LTD., Suzhou New District, China) model: 3210-25A), and precision balance (Brand: KERN; (KERN & SOHN GmbH, Balingen, Germany) EWJ-300-3, d = 0.001 g).

2.3. Sample Preparation and ICP-MS Analysis

The aim of this phase was to generate innovative data on SMD LEDs, and in particular on the concentrations of rare earth elements and precious metals in the collected waste SMD LEDs from household LED lamps as a function of CCT. The samples per CCT base class (2700 K, 3000 K, 4000 K and 6500 K) consisted of different types of SMD LEDs with similar CCT in order to provide a more realistic model of targeted recycling.

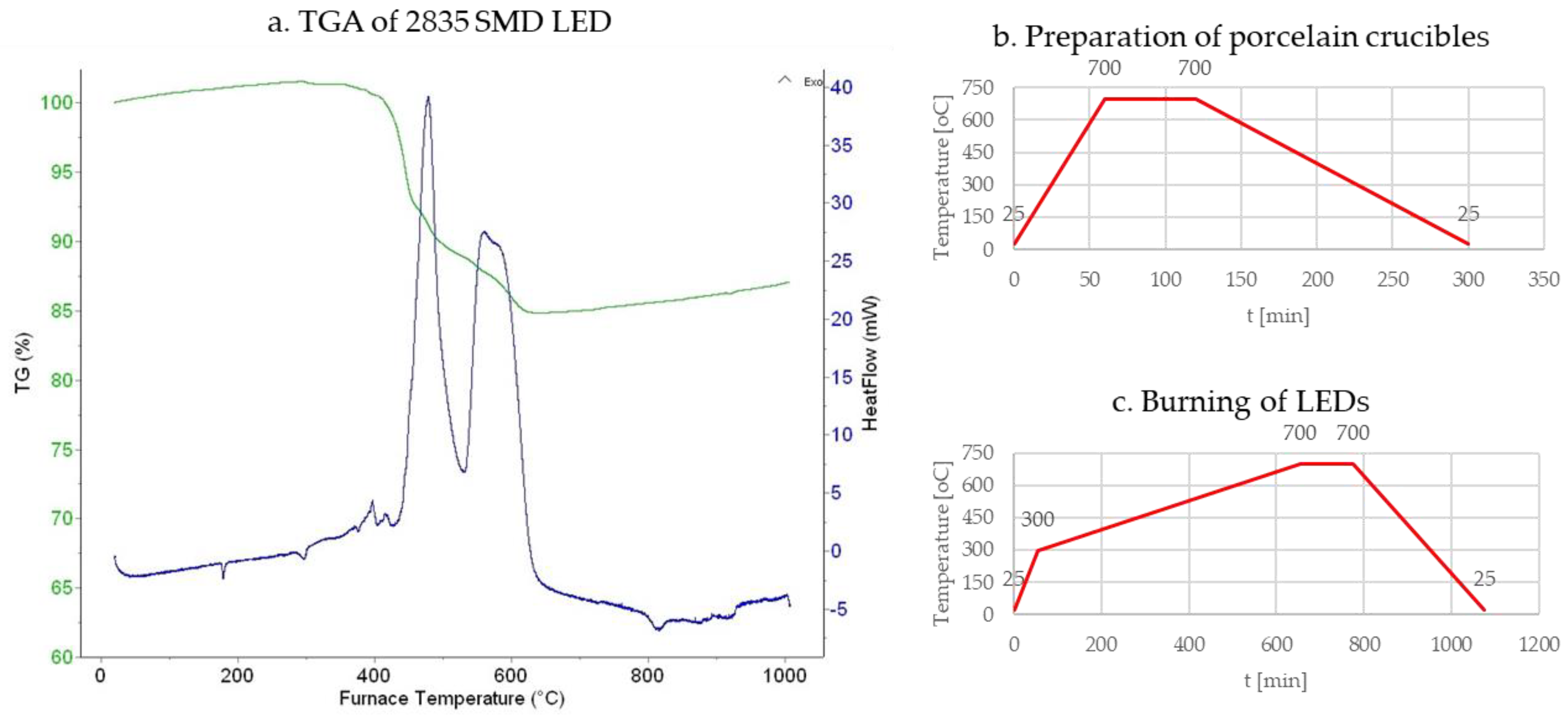

2.3.1. Burning the Samples

In order to select the combustion temperature of the organic part of the samples, a solid SMD LED was tested by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) (

Figure 3a) (Brand: SETARAM; (Setaram - Research Services, Geneva, Switzerland) Model: TG DTA DSC +1600

oC) and the temperature of 700

oC was selected, based on which the porcelain crucible (Brand: JIPO, (Jizerská porcelainka sro, Desná v Jizerských horách I, Czech Republic) shape: middle) were prepared with the heating profile (

Figure 3b) and with the combustion profile of the samples (

Figure 3c).

The following equipment was used for the preparation of the crucibles and the combustion of the samples: (a) analytical balance (Brand: KERN (KERN & SOHN GmbH, Balingen, Germany), model: ABP 200-4M), d=0.0001), (b) laboratory furnace (Brand: THERMOLYNE; (THERMOLYNE - ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) model: 30400) and desiccator.

2.3.2. Sample Pulverisation

This step involved the pulverisation of SMD LEDs to produce laboratory samples (quartering – 0.1 g per sample) and to make most effective approach to acids in the samples [

126,

127,

128], using a ball mill (Brand: FRITSCH; (FRITSCH (FRITSCH GmbH, Idar-Oberstein, Germany) model: pulverisette 6) with a zirconium oxide planetary ball mill tank (Brand: FRITSCH, volume: 80 ml) and analytical balance (Brand: Sartorius; (Sartorius Lab Instruments GmbH & Co. KG, Goettingen, Germany) model: CP124S, d=0.0001).

2.3.3. ICP-MS Analysis

For the characterisation of LEDs, a different laboratory approach is required to study the determination of PMs, REEs and TMs, depending on the structure and the elements studied, compared to other classical electronic components [

31,

34,

73,

129]. For each sample and for the determination of PMs and REEs, the solubilisation was carried out as follows: (quartering – 0.1 g per dry sample) was weighed on an analytical balance (Brand: Sartorius; (Sartorius Lab Instruments GmbH & Co. KG, Goettingen, Germany) model: CP124S, d=0.0001) and transferred to 100 ml teflon beakers. Then 15 ml of concentrated HCl solution, 5 ml of concentrated HNO

3 solution (i.e. 20 ml of aqua regia) and 5 ml of concentrated HF solution were added. The beaker was placed on a hotplate at 200 °C until the sample evaporated to dryness (1-2 h). Then, while the sample was on the hotplate, 5 ml of concentrated HCl solution was added, followed immediately by a few drops of H

2O

2 solution. The mixture foamed and was allowed to stand (for a few seconds). A few drops of H

2O

2 solution were added again, the mixture was allowed to settle and drops of H

2O

2 were added a third time. When the mixture had settled, it was left on the hotplate to dry. When all the solvent had evaporated, 5 ml of concentrated HCl was added and filled into a 100 ml volumetric flask. The flask was made up to the final volume with ultrapure water. The final solution, after filtration, was analysed by ICP-MS for the determination of PMs and RREs. For each sample and for the determination of Ag, solubilisation was carried out as follows: The same procedure was followed under the same conditions until complete evaporation of the solvent. Then 5 ml of concentrated HNO

3 was added, followed by transfer to a 100 ml volumetric flask, filtration, and determination of Ag by ICP-MS.

Samples were analysed by ICP-MS (Brand: PerkinElmer; (PerkinElmer, Beaconsfield Buckinghamshire HP9 2FX, UK) model: SCIEX ELAN 6100.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Participation and Characteristics of the LED Lamps

There are two main reasons why the date of manufacture of LED lamps is important for the recycling sector. Firstly, the concentrations of LED lamps are linked to the manufacturing technology of the time, and the concentrations of PMs and REEs have changed over time. Taking into account the parameters described in the study by Sideris et al. (2023) [

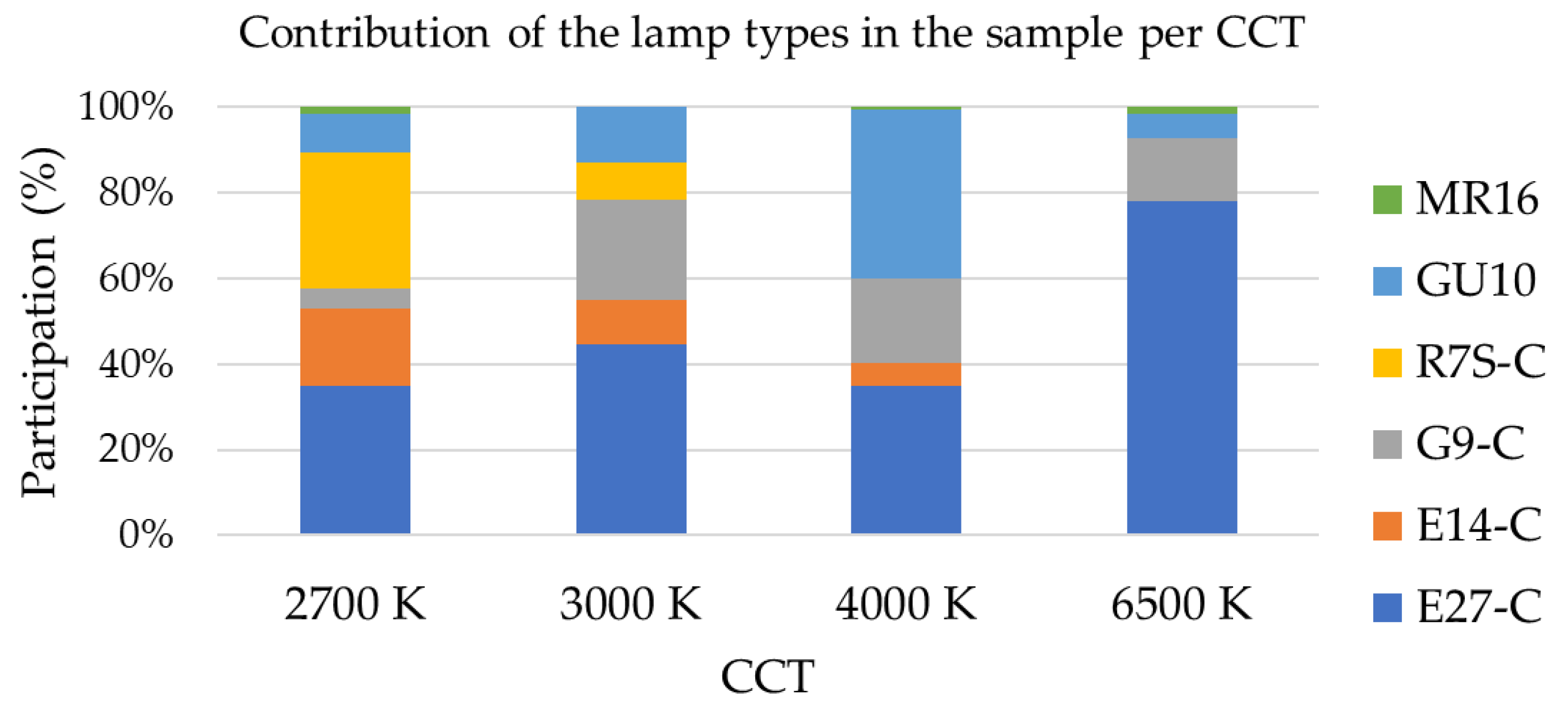

61], the date of manufacture of the lamps in this study was estimated to be between 2016 and 2021. The initial and random collection of the 10.036 kg sample consisted of 221 LED lamps and they were separated according by base type (

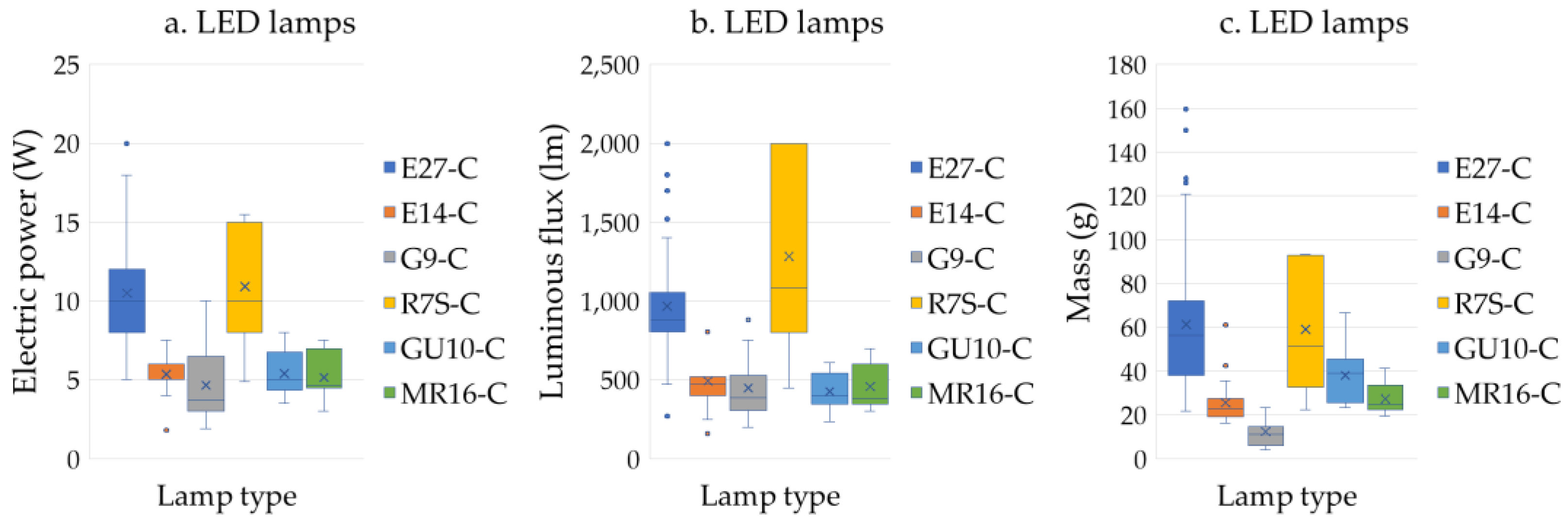

Figure 4) and the LED technology (SMD LEDs, filament, COB).

In this study, the indicator C (classic) (xxx-C) was added to the type of lamps containing SMD LEDs, while the indicator R (retro) (xxx-R) was added to the type of lamps containing filament or COB LEDs. Finally, the percentage of each lamp type in the random sample, was: (a) E27 47.9% (

E27-C 40.7% & E27-R 7.2%), (b) E14 14.5% (

E14-C 10.4% & E14-R 4.1%), c) G9 12.3% (

G9-C 11.8% & G9-R 0.5%), d) R7S 1.9% (

R7S-C 1.4% & R7S-R 0.5%), e) GU10 20.7% (

GU10-C 20.7%), and f) MR16 2.7% (

MR16-C 2.7%). According to Wehbie & Semetey (2022) [

129], the proportions of different lamp types in the samples examined in different studies can vary significantly between different countries and geographical regions, as well as between people's knowledge and culture. From the initial separation, only lamps with SMD LEDs were selected for the study. This was followed by the selection of unique lamps (121 pcs) that differed either in their electrical and photometric characteristics or in their brand name. In order to guarantee the objectivity of the sample and to study only individual lamp masses, selective enrichment was carried out, in particular for G9-C (9 pcs), R7S-C (4 pcs) and MR16-C (10 pcs). The final form of the sample studied consists of 144 unique lamps. In particular, the number of lamps and the number of (

brands) per lamp type were as follows: E27-C 59 (

28), E14-C 23 (

6), G9-C 16 (

8), R7S-C 7 (

4), GU10-C 24 (

14), and MR16-C 15 (

5).

Figure 5 shows the variation of electrical power, luminous flux, and mass as a function of each lamp type in this study. It should be noted that the results of the present study refer to “retrofit” LED lamps for use in residential applications.

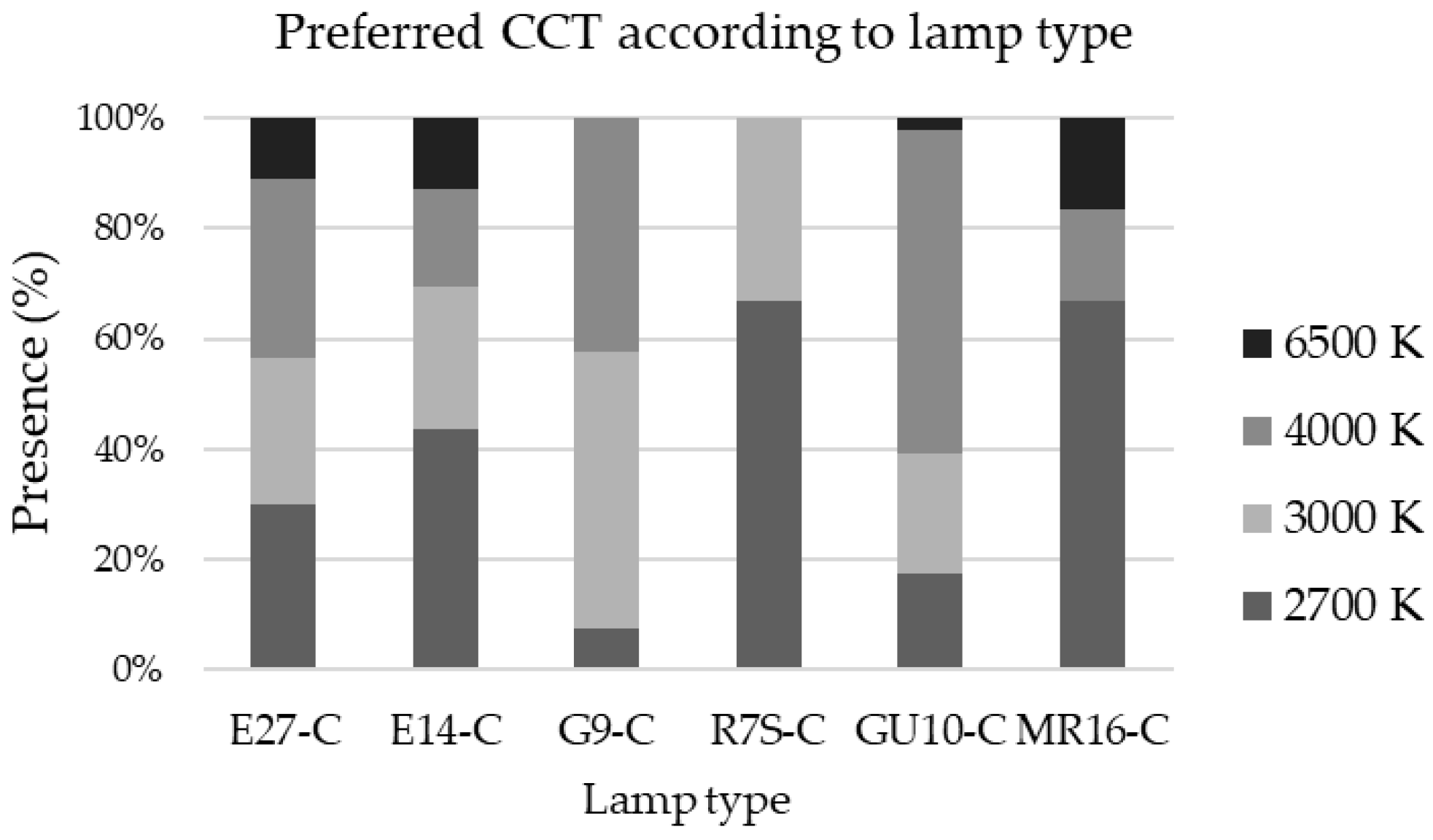

The biological effects of lighting on humans have been observed and studied since ancient times [

102]. In particular, illuminance and colour temperature are two critical photometric variables in lighting applications [

130] that affect people's mental state (Kruithof curve) [

131,

132]. Based on the random sample of lamps in this study,

Figure 6 shows people's preference for the CCT of LED lamps as a function of lamp type, and highlights the reduced psychological preference for cool white CCT lamps (≥ 6000 K) in residential lighting applications.

3.2. Individual Structures of LED Lamps with SMD LEDs

As mentioned above, the structure of an LED lamp is more complex than previous lamp technologies (incandescent & fluorescent). The percentage weight composition of the different basic lamp structures varies considerably. In general, the existing differences can be attributed, individually or in combination, to the following parameters: (a) the manufacturing technology of the respective period, (b) the manufacturing specifications of the brand, (c) the type of lamp, its electrical power and the construction material of the body and lens of the lamp (plastic or glass), which change the individual mass percentages of the structural and functional units of the lamps.

3.2.1. LED Module

The LED module (

Figure 7a) is a specific and perhaps the most important structure of the lamp, both from a functional point of view - production of luminous flux from LEDs - (

Figure 7b), and from a recycling point of view due to the presence of REEs and PMs, as well as base metals (BMs), metals of high economic value and technology metals (TMs). After desoldering and removal of the LEDs, and in the context of this study, the remaining structure is characterised as a bare LED module (

Figure 7c) and differs significantly from the LED module in terms of the presence and concentrations of the aforementioned group of metals [

77]. The bare LED module corresponds to a bare PCB (Figures 7d-e), whose substrate is usually metallic and usually made of aluminium (

Figure 7f) and is known as a metal core printed circuit board (MCPCB) [

84]. This substrate acts as a heat sink for the structure [

133], where the forced thermal equilibrium of SMD LEDs is achieved by the “heat sink and heat transfer” structure of the lamp. Depending on the design of the lamp structure, the metal substrate of the LED module can be replaced by flame retardant (FR) materials such as FR4 [

27,

51,

77,

134].

It is worth noting that there are also applications in lamps where LED modules can be: (a) split type (

R7S-C) (

Figure 8a), (b) flexible type without metal substrate and without resin (

G9-C) (Figures 8b-d), and (c) flexible type with resin material (Figures 8e-f) to be directly bonded to the metal heat transfer and heat sink or to the ceramic body of the lamp (

R7S-C). In addition, in some lamps the driver and LED module form a single structure (integrated LED system) (

Figure 8g), rather than two separate structures [

135]. These cases present a challenge for lamp characterisation due to the different components and varying concentrations, especially with respect to PMs, REEs and other CRMs [

77,

129].

The design and dimensions of the LED module, as well as the number, power, and arrangement of the LEDs on its surface, are a function of the luminous flux of the lamps and their polar distribution. To achieve these parameters, the design of LED modules can vary considerably, even for the same type of lamp [

122,

129].

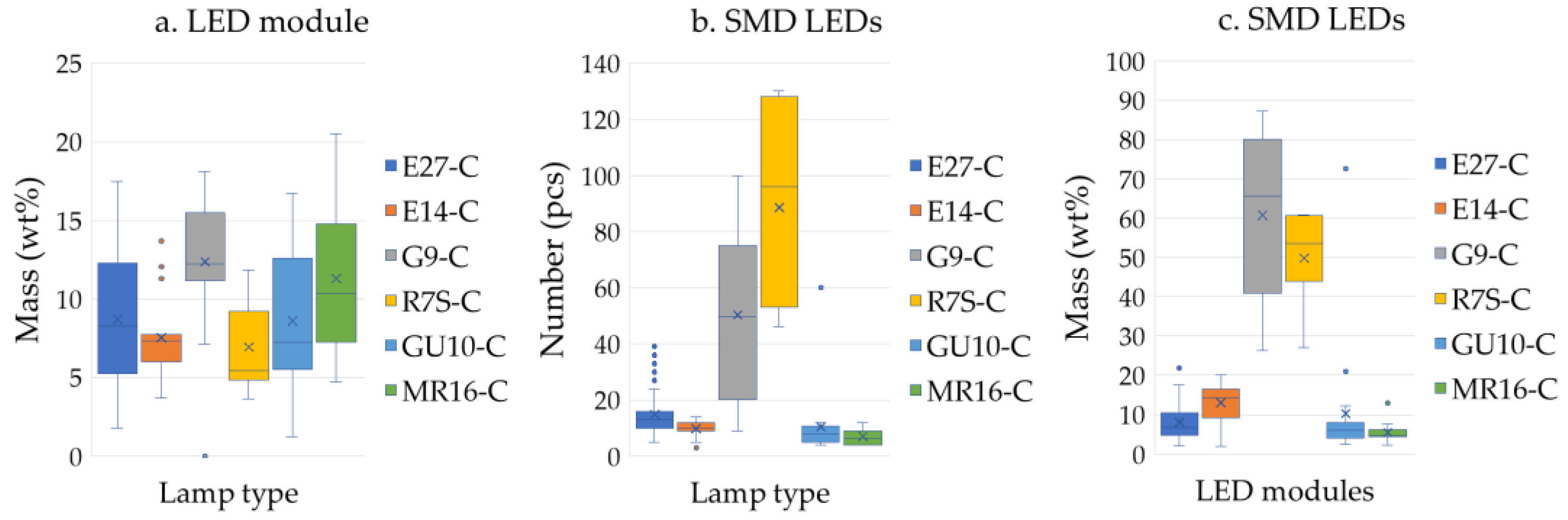

Figure 9 presents data related to the analysis of the structure of the LED modules of the lamps tested. In particular the variation of: (a) the mass of the LED module as a percentage of the mass of the lamp (

Figure 9a); (b) the number of LEDs as a function of the lamp (

Figure 9b), and (c) the total mass of the LEDs as a percentage of the mass of the LED module (

Figure 9c). The variation in the number of SMD LEDs as a function of the type of each lamp is, comparable for the four lamp types and significantly different for the G9-C and R7S-C types. This variation is due to the fact that these lamp types have a particular construction that contributes to the almost diffuse distribution of the luminous flux in the room, which requires a large number of low luminous flux SMD LEDs. The percentage of SMD LEDs in the total mass of the LED module varies depending on the number of SMD LEDs depending on the type of lamp.

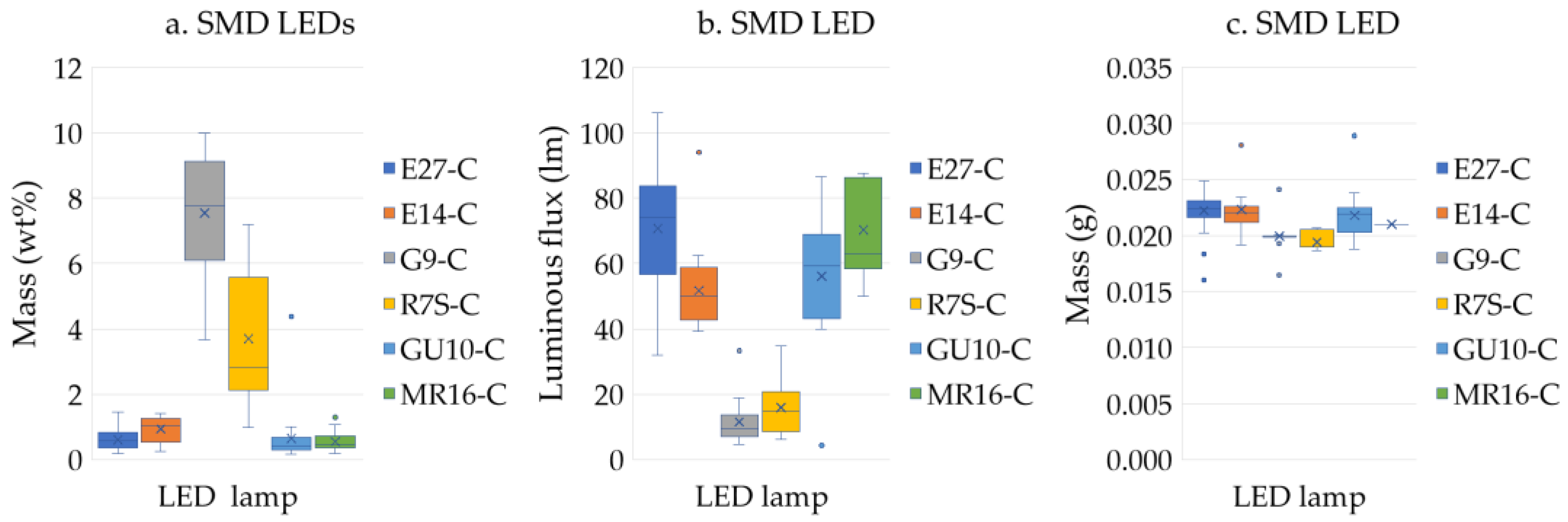

3.2.2. SMD LEDs

Of the 144 unique LED lamps tested in this study, only four lamps used COB LEDs, while the rest used SMD LEDs of various types (2835, 3030, 3035, 3528 and 5050). COB LEDs were not investigated further due to their low participation and different types. The percentage variation of the mass of waste SMD LEDs in relation to the total mass of each type of lamp studied is shown in

Figure 10a, which highlights the significant differentiation of the G9-C and R7S-C lamps compared to the other types, which vary at about the same percentage. This difference is due to the desired polar distribution of the luminous flux of these two lamp types, which is achieved with a low luminous flux per SMD LED and with an increased number of LEDs. The variation in luminous flux per SMD LED is shown in

Figure 10b and is a function of the type of lamp, its electrical power, and the polar distribution of its luminous flux. The variation in mass per waste SMD LED is shown in

Figure 10c, from which it can be seen that an average mass value of 0.022 g is acceptable from a recycling point of view.

3.3. Characterisation of SMD LEDs from LED lamps via ICP-MS Analysis

The

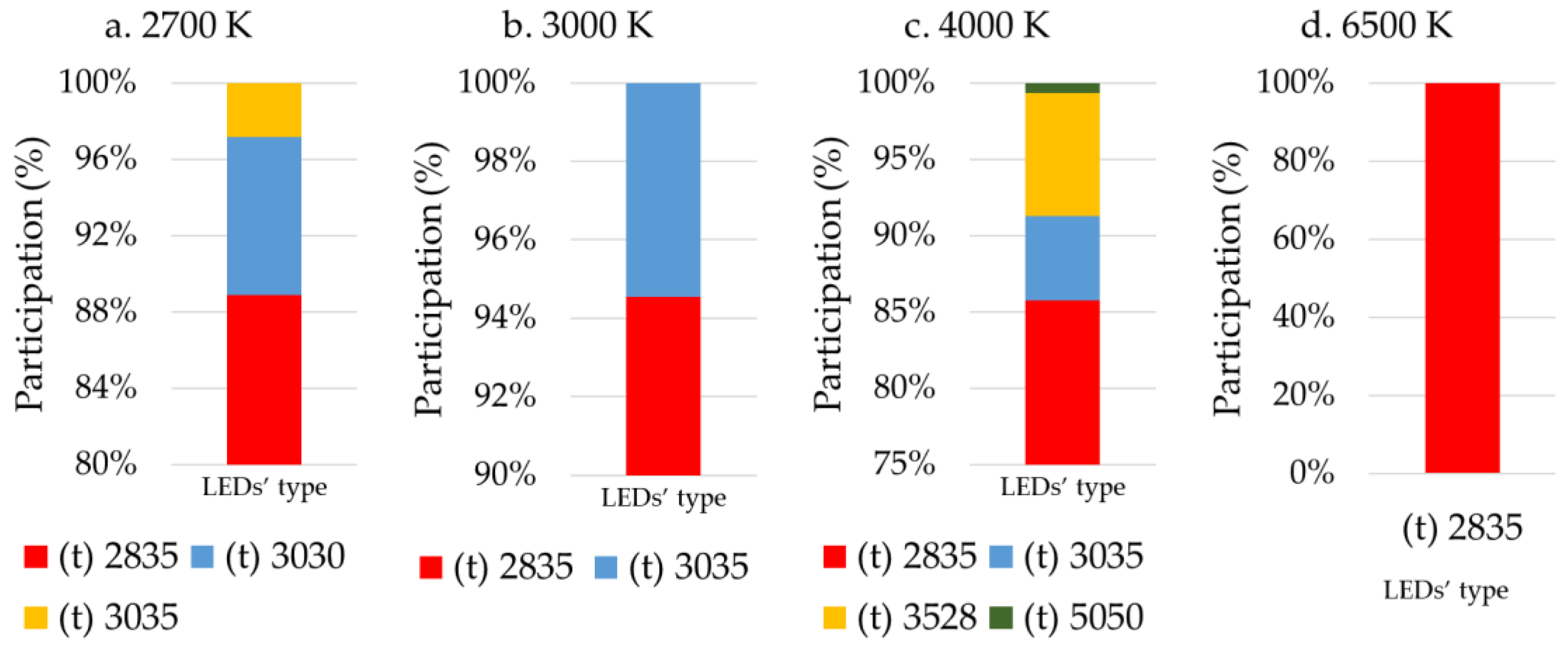

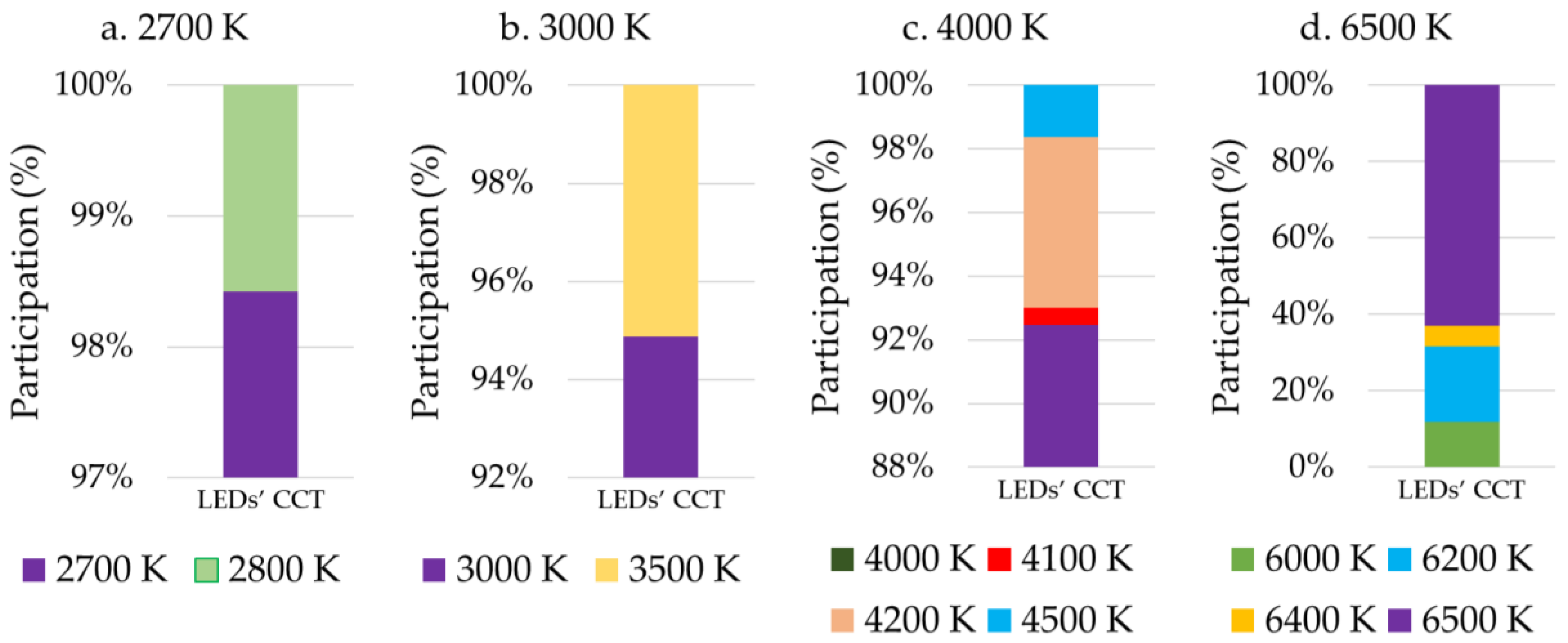

Figure A2 and

Figure A3 show in detail the composition of the samples tested. In particular: (a)

Figure A2 shows the participation rate of the different types of SMD LEDs per CCT, highlighting the high participation rate of type 2835, which ranged between (86 - 100) %, (b)

Figure A3 shows the participation rate of the similar CCTs per CCT tested, highlighting the high participation rate of the basic CCT, which ranged between (60 - 99) %, and (c)

Figure A3 shows the participation rate of the lamp types in the samples tested as a function of the CCT.

The calculated results of the concentrations (mg kg-1) of rare earth elements (La, Ce, Eu, Gd, Tb, Lu and Y) and precious metals (Ag, Au and Pd) detected during the ICP-MS analysis of the tested SMD LEDs of similar CCTs are presented in Tables 1 & 3. Their presence is supported by related studies and commercially available phosphors, Tables 1, 2, and 5 for rare earth elements and Tables 3 and 4 for precious metals.

The essential comparison between the results of this study and the literature review presents insurmountable obstacles related to the sample composition in each case study. The results of the following relevant studies, individually or in combination, support this statement. According to H.-T. Lin et al. (2014), the architectural design of the LEDs and the composition of their raw materials affect their emission spectrum and consequently their luminous flux [

95]. X. Ding et al. (2021) point out that the depth of the package cavity of SMD LEDs filled by the encapsulation varies significantly depending on their type [

136] which shapes the geometric dimensions of the encapsulation and the distribution profile of the phosphor. According to Tan et al. (2018), the luminous flux of LEDs is a function of the thickness of the resin and the concentration of phosphor in it [

108]. According to Y. H. Kim et al. (2015), the “Phosphor/Resin” ratio is significantly different as a function of CCT [

101]. According to Kim et al. (2015), the concentration of yellow phosphor in SMD LEDs affects the luminous flux (lm) of SMD LEDs as a function of the sensitivity curve of the human eye [

28]. Cenci, Dal Berto, Castillo, et al. (2020) state that the differences in their concentrations may be due to the electrotechnical characteristics of SMD LEDs, which are a function of the lamp specifications [

51]. According to Marwede et al. (2012), there is a significant difference in the total die area per LED lighting product depending on the lighting application [

75]. According to Nikulski et al. (2021), the total die area per LED lamp varies depending on the type of lamp and the application in which it is used [

76]. According to Cenci, Dal Berto, Schneider, et al. (2020) the number of die(s) per SMD LED varies depending on the type of lamp [

77]. According to Nair et al. (2020), the synergy of inorganic phosphors with the appropriate rare earth ion dopants for each lighting application is a critical component of the pc-LED structure [

109].

Considering: (a) the above parameters, (b) the results of the ICP-MS analysis, (c) the percentage of participation of each type of lamp per CCT tested, (d) the luminous flux per SMD LED and its participation in the sample, it is clarified, in line with Tunsu et al. (2015) [

32] and Balinski et al. (2022) [

30], that the presence and concentration of REEs in SMD LEDs vary depending on the origin and composition of the sample. In particular, (a) in the case where the sample originates from a specific type of lamp, the presence and concentration of REEs and PMs in SMD LEDs are a function of the electrotechnical specifications of the lamp, and (b) in the case where the sample is formed by the participation of different types of lamps (a more realistic approach from a recycling point of view), an additional factor is taken into account that relates to the percentage participation of each type of lamp in the collected SMD LEDs.

Consequently, the differences between the results of the present study and the literature review may be due, individually or in combination, to the following critical parameters: (a) the type, specifications and production date of the lamps [

30,

32]; (b) the composition, origin and integrity of the sample [

113]; (c) the type and photometric characteristics of the sample [

28]; and (d) the method of sample characterisation for each case study.

Table 1.

Concentration of rare earth elements in SMD LEDs (mg kg-1).

Table 1.

Concentration of rare earth elements in SMD LEDs (mg kg-1).

| Type of LED |

S.O. |

A.T. |

La |

Ce |

Eu |

Gd |

Tb |

Lu |

Y |

Ref |

| SMD |

E27-C |

ICP-OES |

|

90 |

|

|

|

|

6830 |

[77] |

| SMD |

Tube |

“ |

|

90 |

|

|

|

|

2900 |

[77] |

| SMD |

Tube |

“ |

|

100 |

|

|

|

|

1800 |

[51] |

| SMD |

E27-C |

“ |

|

100 |

|

|

|

|

4600 |

[51] |

| SMD |

E27-C |

“ |

|

100 |

|

|

|

|

12000 |

[51] |

| SMD |

E27-C |

“ |

|

100 |

|

|

|

|

5200 |

[51] |

| SMD |

E27 (pro) |

MP-AES |

|

120 |

89 |

|

|

|

4590 |

[122] |

| SMD |

E27 (pro) |

“ |

|

|

24 |

|

|

|

2650 |

[122] |

| SMD |

E27 (pro) |

“ |

|

270 |

120 |

|

|

|

5410 |

[122] |

| SMD |

E27 (pro) |

“ |

|

17 |

87 |

|

|

|

3180 |

[122] |

| SMD 2835 |

Tube |

ICP-OES |

|

70 |

|

70 |

|

|

4040 |

[73] |

| SMD 2835-cw |

Tube |

“ |

|

90 |

|

|

|

|

5070 |

[31] |

| SMD 2835-ww |

Tube |

“ |

|

200 |

|

|

|

|

14250 |

[31] |

| SMD 3020 |

n/a |

“ |

|

1 |

|

0.1 |

|

|

1 |

[121] |

| SMD 3810 |

n/a |

“ |

|

0.5 |

|

0.1 |

|

|

2 |

[121] |

| SMD 4014 |

n/a |

“ |

|

1 |

|

0.1 |

|

|

6 |

[121] |

| SMD 5352 |

n/a |

ICP-OES |

|

3 |

|

0.1 |

|

|

0.3 |

[121] |

| SMD 5630 |

n/a |

“ |

|

3 |

|

0.1 |

|

|

15 |

[121] |

| SMD 5630-1 |

n/a |

“ |

|

2 |

|

0.1 |

|

|

8 |

[121] |

| SMD 5853 |

n/a |

“ |

|

2 |

|

0.1 |

|

|

6 |

[121] |

| SMD 6030 |

n/a |

“ |

|

2 |

|

0.1 |

|

|

12 |

[121] |

| SMD 7020 |

n/a |

“ |

|

1 |

|

0.1 |

|

|

11 |

[121] |

| SMD 7030 |

n/a |

“ |

|

2 |

|

0.1 |

|

|

10 |

[121] |

| SMD COB |

n/a |

“ |

|

0.5 |

|

0.1 |

|

|

0.3 |

[121] |

| SMD 2700 K |

VLLs |

ICP-MS |

1840 |

284 |

69 |

3.8 |

0.4 |

6381 |

9372 |

p. study |

| SMD 3000 K |

VLLs |

“ |

1287 |

289 |

48 |

3.0 |

0.1 |

700 |

11551 |

“ |

| SMD 4000 K |

VLLs |

“ |

389 |

132 |

29 |

2.0 |

0.1 |

742 |

4804 |

“ |

| SMD 6500 K |

VLLs |

“ |

242 |

167 |

15 |

1.9 |

0.1 |

29 |

7303 |

“ |

| n/a (not available), pro (professional use), S.O. (sample’s origin), A.T. (analytical technique), VLLs (various LED lamps), ICP-OES (inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy), MP-AES (microwave plasma atomic emission spectroscopy) |

Table 2.

Concentration of rare earth elements in dies & encapsulation (D & E) of SMD LEDs (mg kg-1).

Table 2.

Concentration of rare earth elements in dies & encapsulation (D & E) of SMD LEDs (mg kg-1).

| Sample |

S.O.

|

A.T.

|

La |

Ce |

Eu |

Gd |

Tb |

Lu |

Y |

Ref |

| D & E |

SMD LEDs |

ICP-MS |

≤5 |

D |

320 |

13 |

≤5 |

<100 |

79600 |

[30] |

| “ |

“ |

“ |

≤5 |

D |

251 |

6 |

≤5 |

154700 |

100 |

[30] |

| “ |

“ |

“ |

≤5 |

D |

197 |

15 |

≤5 |

100 |

42000 |

[30] |

| “ |

“ |

“ |

≤5 |

D |

233 |

9 |

≤5 |

<100 |

48100 |

[30] |

| “ |

“ |

“ |

≤5 |

D |

308 |

10 |

≤5 |

171900 |

600 |

[30] |

| Detected (D) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 3.

Concentration of precious metals in SMD LEDs (mg kg-1).

Table 3.

Concentration of precious metals in SMD LEDs (mg kg-1).

| Type of LED |

S.O. |

A.T. |

Ag |

Au |

Pd |

Ref |

| SMD |

n/a |

ICP-MS |

|

16 |

|

[118] |

| SMD |

E27-C |

ICP-OES |

4820 |

520 |

|

[77] |

| SMD |

Tube |

“ |

7180 |

540 |

|

[77] |

| SMD |

Tube |

“ |

5900 |

700 |

|

[51] |

| SMD |

E27-C |

“ |

6200 |

700 |

|

[51] |

| SMD |

E27-C |

“ |

3100 |

200 |

|

[51] |

| SMD |

E27-C |

“ |

4400 |

500 |

|

[51] |

| SMD |

E27 (Pro) |

MP-AES |

780 |

1210 |

|

[122] |

| SMD |

E27 (Pro) |

“ |

1040 |

|

|

[122] |

| SMD |

E27 (Pro) |

“ |

1780 |

2150 |

|

[122] |

| SMD |

E27 (Pro) |

“ |

780 |

3010 |

|

[122] |

| SMD 2835 |

Tube |

ICP-OES |

1660 |

|

|

[73] |

| SMD 2835 - cw |

Tube |

“ |

1590 |

150 |

|

[31] |

| SMD 2835 - ww |

Tube |

“ |

2390 |

180 |

|

[31] |

| SMD 3020 |

n/a |

“ |

349 |

2265 |

|

[121] |

| SMD 3528 |

n/a |

“ |

800 |

|

|

[120] |

| SMD 3528 |

Strip lights |

ICP-MS |

2130 |

|

|

[34] |

| SMD 3810 |

n/a |

ICP-OES |

347 |

3687 |

|

[121] |

| SMD 4014 |

n/a |

“ |

411 |

2082 |

|

[121] |

| SMD 5352 |

n/a |

ICP-OES |

325 |

507 |

|

[121] |

| SMD 5630 |

n/a |

“ |

297 |

1237 |

|

[121] |

| SMD 5630-1 |

n/a |

“ |

320 |

742 |

|

[121] |

| SMD 5853 |

n/a |

“ |

321 |

323 |

|

[121] |

| SMD 6030 |

n/a |

“ |

333 |

1723 |

|

[121] |

| SMD 7020 |

n/a |

“ |

340 |

1171 |

|

[121] |

| SMD 7030 |

n/a |

“ |

351 |

939 |

|

[121] |

| SMD COB |

n/a |

“ |

1550 |

875 |

|

[121] |

| n/a |

n/a |

ICP-AES |

1700 |

90 |

|

[26] |

| SMD 2700 K |

VLLs |

ICP-MS |

5262 |

934 |

110 |

P. study |

| SMD 3000 K |

VLLs |

“ |

4754 |

502 |

72 |

“ |

| SMD 4000 K |

VLLs |

“ |

3129 |

677 |

32 |

“ |

| SMD 6500 K |

VLLs |

“ |

2712 |

956 |

63 |

“ |

| ICP-AES (inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy) |

Table 4.

Concentration of precious metals in dies & encapsulation (D & E) of SMD LEDs (mg kg-1).

Table 4.

Concentration of precious metals in dies & encapsulation (D & E) of SMD LEDs (mg kg-1).

| Sample |

S.O. |

A.T. |

Ag |

Au |

Pd |

Ref |

| D & E |

SMD LEDs |

ICP-MS |

1589 |

12 |

1623 |

[30] |

| “ |

“ |

“ |

18 |

6 |

4 |

[30] |

| “ |

“ |

“ |

977 |

2 |

842 |

[30] |

| “ |

“ |

“ |

621 |

4 |

942 |

[30] |

| “ |

“ |

“ |

1377 |

2 |

13 |

[30] |

| Dies |

SMD LEDs |

“ |

|

1520 |

|

[118] |

3.3.1. Presence of Rare Earths

Presence Per Element

The detection of REEs by ICP-MS analysis in our samples is related to the presence of a specific phosphor type or to the synergy of different phosphor types. In addition to the relevant studies mentioned above, their presence is also supported by commercially available inorganic phosphors used in LEDs for general lighting applications (

Table 5).

In Particular:

a)

Lanthanum (La): Lanthanum was also detected in the study of Balinski et al. (2022), where they investigated ”dies & encapsulation” of SMD LEDs, showing a low concentration ≤ 5 mg kg

-1 [

30]. In the present study, lanthanum was present as a major element (content > 0.1%) for the 2700 K & 3000 K cases and as a trace element (content < 0.1%) for the other CCTs. Its concentration ranged between (242 - 1840) mg kg

-1, showing a decreasing trend with increasing CCT, and is significantly higher compared to its concentration in the Earth's crust (39 mg kg

-1) [

143] and MLCCs from lighting equipment (20 mg kg

-1) [

61].

b)

Cerium (Ce): The combination of the above findings and the grouping of the correlated colour temperatures considered, “warm light” (2700 K & 3000 K) and “cool light” (4000 K & 6500 K), is consistent with the change in cerium concentration, both in the results of the present study and in the results of Vinhal et al. (2022), who studied “warm white” and “cool white” SMD LEDs [

31]. The presence of cerium, in both the literature review and the present study was as a trace element. The concentrations of cerium based on the literature review ranged from (0.5 - 270) mg kg

-1, while in the study by Balinski et al. (2022) its presence was described as significant. The concentration of cerium in the present study ranged from (132 - 289) mg kg

-1, with higher values in the warm CCTs. This concentration is higher than its concentration in the Earth's crust (66.5 mg kg

-1) [

143], but lower than the concentration in MLCCs from lighting equipment (530 mg kg

-1) [

61].

c)

Europium (Eu): Europium was also found in the study by Illés & Kékesi. (2023) [

122], where SMD LEDs from E27-C professional lamps were analysed, and in the study by Balinski et al. (2022) [

30]. Europium was present as a trace element in the results of the relevant studies as well as in the results of the present study. In the present study its concentration ranged between (15 - 69) mg kg

-1, whereas in the study by Illés & Kékesi. (2023) [

122] the concentration was between (24 - 120) mg kg

-1. In the study by Balinski et al. (2022) its concentration ranged between (197 - 320) mg kg

-1 [

30] and seems to be significantly higher than the above mentioned concentrations due to the specificity of their samples (naturally enriched samples). Both in the present study and in the study by Illés & Kékesi. (2023) [

122], the europium concentration in the SMD LEDs investigated are significantly higher than the concentration in the Earth's crust (2 mg kg

-1) [

143].

d)

Gadolinium (Gd): Gadolinium has also been detected in studies by Oliveira et al. (2020) [

73], Mandal et al. (2023) [

121] and Balinski et al. (2022) [

30], which documenting its presence in phosphors used in SMD LEDs for general lighting applications. According to “Eurofins” gadolinium was detected as a dopant in YAG phosphors in a study of LED phosphors [

144]. Gadolinium appears as a trace element in the results of both the literature review and the present study. Its concentration in the study by Mandal et al. (2023) [

121] was extremely low and of constant value for all the samples considered (0.1 mg kg

-1), while in the study by Oliveira et al. (2020) [

73] it presents a high value (70 mg kg

-1). Considering the “enriched samples” examined in the study by Balinski et al. (2022) [

30], the concentration of gadolinium ranged between (6 - 13) mg kg

-1 and are higher than the concentration in the present study, which ranged between (1.9 - 3.8) mg kg

-1. A comparison of the gadolinium concentration in the present study with its concentration in the Earth's crust (6.2 mg kg

-1) [

143] shows a lower concentration, while a comparison with its concentration in MLCCs from lighting equipment (150 mg kg

-1) [

61] shows significantly lower concentration.

e)

Terbium (Tb): The terbium concentration in the results of the present study ranged between (0.1 - 0.4) mg kg

-1, as well as to its low presence in the study by Balinski et al. (2022) [

30] (≤ 5 mg kg

-1). The terbium concentration in the waste SMD LEDs of the present study appears to be significantly lower than its concentration in the Earth's crust (1.2 mg kg

-1) [

143].

f)

Lutetium (Lu): The lutetium concentration in the results of the present study ranged between (29 - 6,381) mg kg

-1 and appears to be significantly higher than its concentrations in the Earth's crust (0.8 mg kg

-1) [

143]. In the present study, lutetium is present as a major concentration at 2700 K, whereas in the other CCTs it is present as a trace element.

g)

Yttrium (Y): The concentration of yttrium per CCT in the tested SMD LEDs ranged between (4,804 – 11,551) mg kg

-1 and, with the exception of the concentration of lutetium at 2700 K, are significantly higher than all the elements of the REEs detected. The concentration of yttrium in the samples of the present study compared to the concentration of yttrium: a) in the Earth's crust (33 mg kg

-1) [

143] are significantly higher, b) in MLCCs from lighting equipment (2,200 mg kg

-1) [

61] appears higher, and c) in MLCCs of a specific colour (brown) (3,000 mg kg

-1) and (8,000 mg kg

-1) [

20] are comparable.

Group Presence

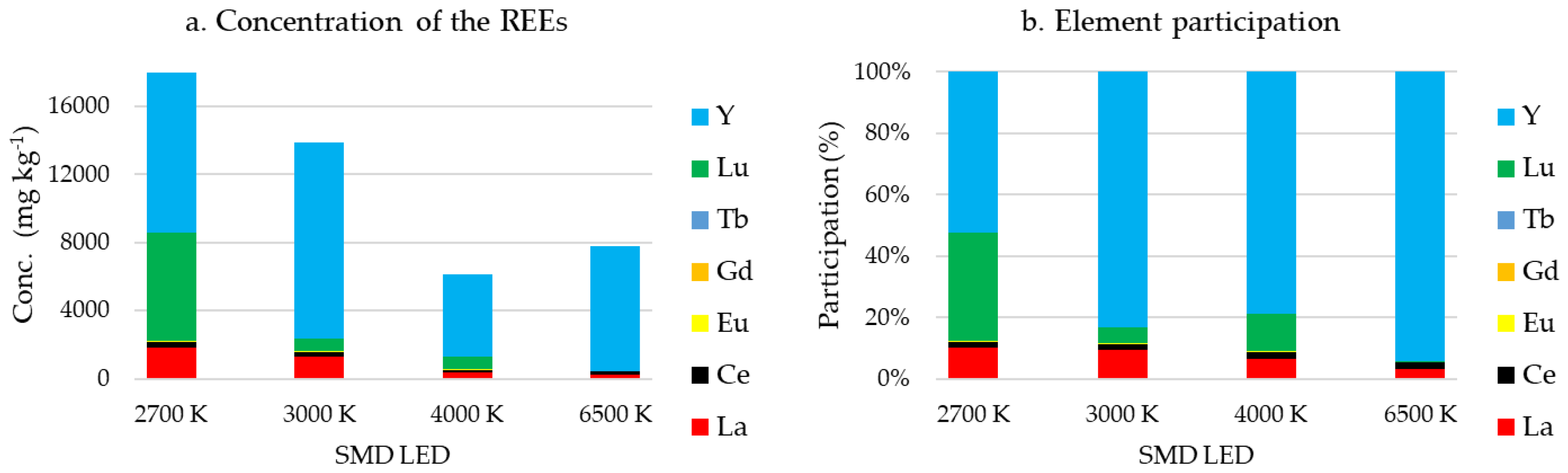

The concentration of REEs in the samples tested in this study differed significantly between CCTs (

Figure 11a) and ranged between (6,098 – 17,950) mg kg

-1 with the highest concentration at 2700 K and the lowest at 4000 K.

Figure 11b shows the percentage contribution of each element per CCT, which ranged between La (3.119 - 10.251) %, Ce (1.582 - 2.165) %, Eu (0.193 - 0.476) %, Gd (0.021 - 0.033) %, Tb (0.001 - 0.002) %, Lu (0.374 - 35.548) % and Y (52.211 - 94.135) %.

Figure 11b highlights the high participation of: (a) Y in all CCTs, (b) La in the warm CCTs (2700 K, 3000 K), and (c) Lu at 2700 K.

In general, differences in REEs concentrations are due to the composition of the sample and its specifications. In particular, and according to the relevant literature below, it is clear that both the presence of REEs and their concentrations can vary significantly depending on the type, CCT and, more generally, with the specifications of SMD LEDs. According to Balinski et al. (2022), among the five different types of SMD LEDs they investigated, the mass of “dies & encapsulation” per SMD LED differed significantly between them [

30]. According to Tan et al. (2018), increasing the thickness of the resin and the concentration of phosphor in it leads to the production of “warm light” [

108]. According to Y. H. Kim et al. (2015), in the industrial production of “blue LEDs” with CRI > 90 (high colour fidelity lighting applications), the “phosphor to resin” ratio varies as a function of CCT, showing a decreasing trend in phosphor content with increasing CCT [

101], which “matches” the trend of REEs concentrations in the present study.

The presence of REEs may be related to the presence of specific phosphors, where the modification of their chemical composition [

139] or the synergy between them [

68] contributes to the creation of the desired luminous flux composition, especially for SMD LEDs. In particular:

a) The combination of elements (Y, Gd, Lu and Ce) may be associated with the presence of the commercial phosphor (Y,Gd,Lu)

3(Al,Ga)

5O

12:Ce

3+, where according to Kwangwon Park et al. (2016), by varying its chemical composition, the desired (per application) shifting of the generated radiation within the visible region of the electromagnetic spectrum, and in particular between the green and yellow “regions”, is achieved [

139].

b) The combination of the presence of the elements La and Ce is probably associated with the presence of the commercial LED phosphor LSN (La

3Si

6N

11:Ce

3+), while the combination of the presence of the elements (La, Y and Ce) is probably associated with the presence of the commercial LED phosphor LYSN (La,Y)

3Si

6N

11:Ce

3+) [

137].

c) The combination of the presence of Y and Ce elements is probably related to the presence of the yellow LED phosphor YAG (Y

3Al

5O

12:Ce

3+) [

45,

137,

138]. This phosphor, which shows high efficiency, is used without the synergy of other phosphors to produce CCT ≥ 4500 K [

68] due to the absence of warm wavelengths [

45]. This finding is consistent with the participation of REEs at 6500 K in the present study, where there is an increase in the participation of Y (78.78 → 94.14) % and the “annihilation” of the participation of Lu (12.17 → 0.37) % compared to 4000 K, thus producing the desired “cooler” optical effect.

d) The combination of the presence of Lu and Ce elements is probably related to the presence of the commercially available green phosphor LuAG (Lu

3Al

5O1

2:Ce

3+) [

68,

137,

138] which is used in the production of white LEDs [

139]. Among other applications, this phosphor is used in combination with yellow or red phosphors [

68] to produce warm CCTs accompanied by a very high colour rendering index (≥95) and exploited in lighting applications where high colour fidelity is required or in special radiation LED applications [

65,

138]. The combination of the above probably explains the particularly increased presence of Lu (35.55%) at 2700 K compared to the other CCTs, where it ranged between (0.37 - 12.17) %.

3.3.2. Presence of Precious Metals

Presence Per Element

In addition to the relevant studies mentioned above, the presence of PMs in the ICP-MS analysis results of this study is also supported by studies of the individual structures of SMD LEDs, as well as the commercially available conductive wires, solder and die attach materials used in SMD LEDs designed for general lighting applications. In general, the presence of precious metals is associated with the raw materials of SMD LEDs and the solder residues on their external electrical contacts. In particular, their detection is linked to their possible presence in the power supply of SMD LEDs and in their internal electrical circuit.

These PMs, individually or in combination, are potentially concentrated in the following locations of discarded SMD LEDs. In particular: (a) in their external electrical contacts (lead frame) [

145] and in the solder residues on them [

57], (b) in the electrical contacts of the dies (pads) [

51] and in the electrodes of their structure [

27,

144], (c) in the electrical connection of the external electrical contacts of the SMD LEDs to the electrical contacts of the dies (wire bonding) and in the electrical connection between the dies in the case of PC-WLEDs which include more than one die in their structure [

12,

27,

28]; (d) the material of the reflector (certain types of SMD LEDs); and (e) the material for the mechanical attachment (die attachment) of the die(s) to their substrate [

27].

The raw materials of these individual structures, their structure technology (alloy, solid, plated, or flash coated) and the type of their die(s) (lateral, vertical, or flip-chip) constitute the stored potential of PMs in discarded SMD LEDs. In particular:

a)

Silver (Ag): The concentration of Ag in the present study, ranged between (2,712 – 5,262) mg kg

-1, showing a decreasing trend with increasing CCT, which is in agreement with the results of the study of Vinhal et al. (2022), who studied SMD LEDs of two main categories of CCT “warm white” and “cool white” [

31]. Based on the literature review, its concentration in individual structures of SMD LEDs ranged between (297 – 7,180) mg kg

-1, while in the study by Balinski et al. (2022) its concentration ranged between (18 – 1,589) mg kg

-1 [

30]. The concentration of Ag in the SMD LEDs used in the present study is presented as: a) extremely higher than its concentration in the Earth's crust (0.075 mg kg

-1) [

146]; b) comparable to MLCCs from both lighting equipment (4,670 mg kg

-1) and various other e-wastes (1,300 - 50,100) mg kg

-1 [

61]; c) comparable to Ta-capacitors (4,600 – 30,000) mg kg

-1; [

54,

61], integrated circuits (ICs) and diodes (up to 10,000 mg kg

-1) [

54]; d) higher than the concentrations of drivers (50 - 140) mg kg

-1 and bare LED modules (20 - 40) mg kg

-1 of LED lamps (tube, E27-C) [

77].

b)

Gold (Au): In the context of the present study, its concentration ranged between (502 - 956) mg kg

-1, with its highest value at 6500 K. Based on the relevant literature, the concentration of Au in individual structures of SMD LEDs, ranged between (150 – 3,687) mg kg

-1, while in the study of their individual structures, its concentration varied: (a) in the study by Balinski et al. (2022) between (2 - 12) mg kg

-1 [

30], and (b) in the study of Zhan et al. (2015), where only dies were examined, the concentration was found to be in the range of 1,520 mg kg

-1 [

118]. The concentration of Au in the present study compared to: (a) its concentration in the Earth's crust (0.0032 mg kg

-1) [

146] is significantly higher, (b) MLCCs from both lighting equipment (10 mg kg

-1) is significantly higher, while from various other e-waste (1 - 10,000) mg kg

-1 [

61] is comparable, (c) with ICs, transistors and diodes (up to 10,000 mg kg

-1), is lower [

54], (d) concentrations of drivers (140 - 200) mg kg

-1 and bare LED modules (280 - 300) mg kg

-1 of LED lamps (tube, E27-C) [

77] from comparable to higher.

c)

Palladium (Pd): The detection of Pd in the present study is also supported by the study of Balinski et al. (2022), who examined individual structures of SMD LEDs (dies & encapsulation) [

30], which as expected included the solder wire. In addition, its detection is also supported by commercially available solder wires used in microelectronics in general and SMD LEDs in particular [

63,

87]. The concentration of Pd in the present study ranged between (32 - 110) mg kg

-1, showing a continuous decrease in its concentration with increasing CCT from 2700 K to 4000 K, while it showed a similar concentration at 3000 K and 6500 K. The concentration of Pd as a function of CCT is shown to be significantly higher than its concentration in the Earth's crust (0.0082 mg kg

-1) [

146], while it is lower compared to MLCCs from both lighting equipment (1,050 mg kg

-1) and various other e-wastes (500 - 30,000) mg kg

-1 [

61]. Particularly high concentrations were found in the study by Balinski et al. (2022), in particular in three of the five cases of the examined samples, with a concentration between (842 – 1,623) mg kg

-1, while in the other cases the concentration was between (4 - 13) mg kg

-1, which highlights the influence of the technical specifications of the SMD LED production on the concentrations of PMs [

30]. Even more focused than the aforementioned study on the structure of SMD LEDs, Zhan et al. (2015) characterised dies (lateral structure) with gold pads, which showed a high concentration of Au (1,520 mg kg

-1), while no Ag and Pd were detected [

118]. This high concentration is probably explained by the specific characteristics of the sample (naturally enriched sample). From the synergy of the two aforementioned studies and the study by Alim et al. (2021) [

81] related to the use of solder wires containing Pd in their structure, it is clear that the possible presence of Pd in SMD LEDs is essentially related to the interconnections of their structures (solder wire).

Group Presence

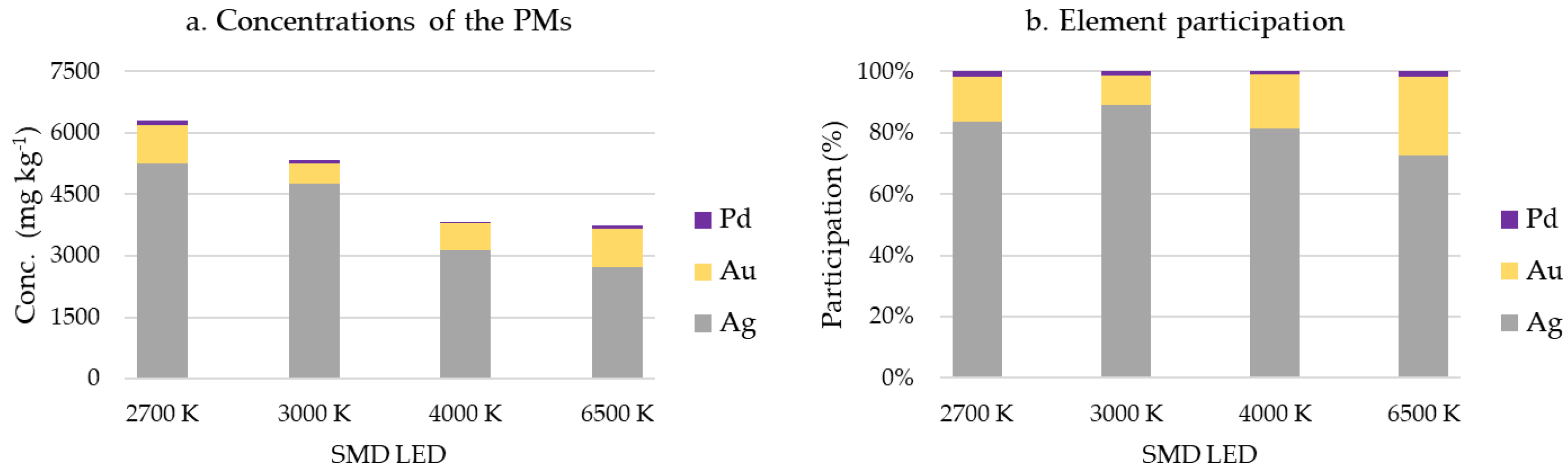

The concentration of PMs in the SMD LEDs tested in this study varied significantly per CCT (

Figure 12a), and ranging from (3,731 - 6,305) mg kg

-1, showing the highest concentration at 2700 K and the lowest at 6500 K.

Figure 12b shows the percentage contribution of each element per CCT, which varied for Ag (72.691 - 89.227) %, Au (9.418 - 25.629) %, and Pd (0.821 - 1.743) %, highlighting the high percentage contribution of Ag in all CCTs.

The differences between the concentrations are due to the composition of the sample, both in terms of the type of SMD LEDs and their manufacturing specifications [

85,

89,

147], which are chosen on the basis of techno-economic criteria [

63,

78,

79,

81,

82,

83,

84,

148] and are a function of both the scope of their application [

89] and their criticality [

78,

85].

In particular, the concentrations may vary according to the technical specifications and dimensions of the individual structures of the SMD LEDs, and in particular, according to: (a) the type of SMD LEDs used and the composition of the solder material used on the pads of the LED module; (b) the type of die, its power, its surface area and the type and composition of the materials used to attach it to the substrate; (c) the type, composition and geometric dimensions (diameter, length) of the wire, (d) the material used to manufacture the electrical contacts (pads) of the dies, (e) by the geometric dimensions of the pads and electrodes of the dies, and (f) by the wire reflection coefficient as a function of the CCT [

84]. The above, individually or in combination, influence the concentrations of precious metals in SMD LED e-waste.

3.4. Concentration of REEs and PMs in Residential LED Lamps

According to Cenci, Dal Berto, Schneider, et al. (2020) [

77] and Cenci, Dal Berto, Castillo, et al. (2020) [

51], the presence of PMs, such as Ag and Au, in LED lamps is divided into three sub-structures: (a) the driver, (b) the bare LED module, and (c) the SMD LEDs. In particular, and according to Cenci, Dal Berto, Schneider et al. (2020), in the LED lamps (tube and bulb) they studied, the distribution of the aforementioned PMs (Ag, Au) in the above lamp structures varied significantly depending on the type of lamp, while the presence of REEs (Ce, Y) was exclusively related to the SMD LED structure [

77].

As already explained, the presence of REEs in LED lamps is mainly associated with SMD LEDs and MLCCs. Unlike SMD LEDs, MLCCs do not have a constant presence in most types of lamps [

61] and their average mass is shown to be significantly lower compared to the mass of SMD LEDs in this study. This can be explained by the fact that the choice of electronic and non-electronic components of the lamp drivers is a function of both their design technology and the electrical power of the lamp [

114].

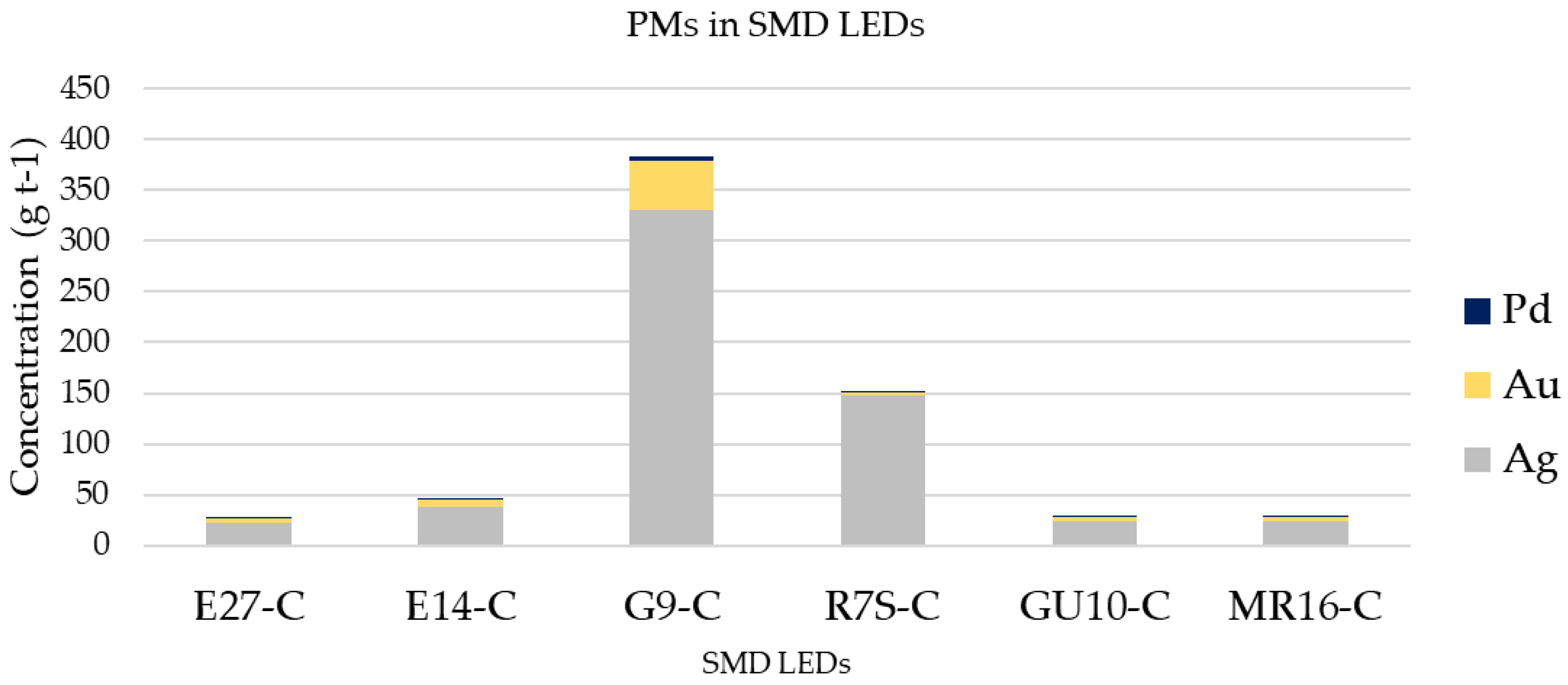

Taking into account: (a) the average mass of the LED lamp and the average mass of the SMD LEDs per lamp type (

Table A1), (b) the percentage of CCT participation per lamp type in the random sample (

Table A2), and (c) the precious metal concentrations in the SMD LEDs per CCT, the stored potential of the PMs (Ag, Au and Pd) in the SMD LEDs of the LED lamps was calculated for an assumed mass of one tonne (1 t) per lamp type (

Table A3) and is summarised in

Figure 13. This figure highlights the strong presence of the G9-C lamp, which is largely due to both the high mass of the of SMD LEDs relative to the total lamp mass (7.549 wt%), and the lamp contribution per CCT, as the concentrations vary significantly as a function of CCT.

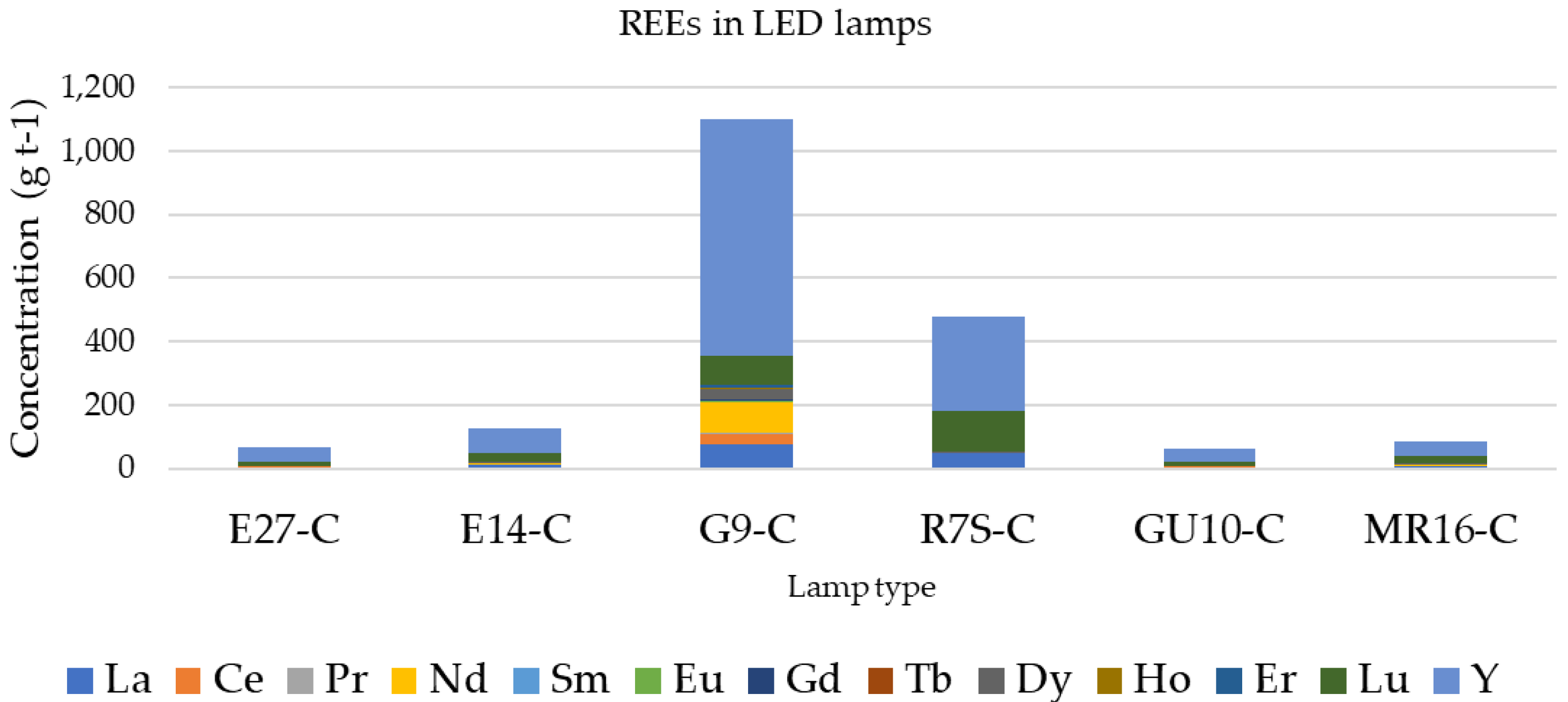

Taking into account the above parameters and in addition the presence rate and average mass of MLCCs (

Table A4) and the concentrations of REEs in MLCCs from lighting equipment (

Table A5), the concentrations of REEs in an assumed mass of one tonne (1 t) per lamp type were calculated and are detailed in

Table A6 and summarised in

Figure 14. In particular,

Table A6 shows the results for the concentrations of REEs and the contribution of SMD LEDs and MLCCs to the concentration of each element.

Figure 14 highlights the superiority of the REEs concentration in the G9-C lamp (1,099 g t

-1) compared to the other lamp types where it varied between (65 - 477) g t