1. Introduction

Soil microbes are crucial for nutrient cycling, organic matter decomposition, and overall soil health, which are vital for the sustainability of terrestrial ecosystems. The role of soil microbial communities in regulating biogeochemical cycles and maintaining ecosystem functions is well-recognized [1-4]. Notably, microbial communities are more sensitive to environmental fluctuations compared to plants and animals [5, 6]. Variations in factors such as climatic conditions, vegetation patterns, and soil characteristics, especially in environments with altitude gradients, can profoundly alter microbial community structures and functions [7, 8]. Despite the importance of soil microbes, comprehensive understanding regarding the underlying drivers that shape microbial diversity and community composition are not fully explored, particularly in regions where environmental gradients such as altitude create highly variable conditions. Further exploration of these factors is essential for gaining a deeper insight into the intricate interplay between soil microbial communities and their environment, ultimately contributing to the conservation and restoration of soil health and the sustainability of terrestrial ecosystems.

Altitude is known to be a major determinant of soil microbial diversity, yet its interaction with plant species in shaping these communities is not sufficiently addressed. Numerous studies have highlighted that changes in altitude induce significant shifts in air temperature, moisture, soil nutrient availability and biodiversity, which in turn affect the structure and function of microbial community [9, 10]. Nevertheless, while altitude is often treated as the primary influencing factor, the pivotal role of plant species-through mechanisms like root exudation and litter deposition-remains underexplored in these considerations [

11]. Deciphering how plant species interact with altitude to influence soil microbes is critical for attaining a holistic comprehension of ecosystem dynamics.

The functional diversity of microbial communities is as important as their taxonomic diversity. Microorganisms facilitate the recycling of organic matter through metabolic activities, thereby enhancing soil structure and fertility [

12]. They also enhance stress resistance and promote plant growth and development through processes such as rhizosphere nitrogen fixation and phosphorus solubilization [13-15]. Furthermore, microorganisms play a pivotal role in soil remediation and ecological function restoration by degrading pollutants in soil and participating in biochemical processes like carbon and nitrogen cycling [16, 17]. However, the relationship between microbial functional diversity and influence factors, such as altitude and plant species, is not well understood, impeding our ability to accurately predict how these communities might respond to environmental changes. This knowledge gap highlights the need for research that integrates both taxonomic and functional perspectives, which is crucial for advancing our understanding of plant-microbe interactions. Moreover, it is also essential for developing effective conservation and management strategies in ecosystems vulnerable to environmental changes.

The Qinling Mountains, serving as a vital ecological security barrier in China, are also a transitional and sensitive zone between subtropical and warm temperate climates. They hold a wide range of altitude gradients and abundant biodiversity, yet are also vulnerable to the spread and expansion of invasive plant species. In an earlier risk assessment of 131 exotic plant species recorded in the Qinling Mountains, four were identified as extremely high risks, including

Galinsoga quadriradiata [

18]. Our study focused on the soil microbial communities associated with the invasive

G. quadriradiata and the native

Artemisia lavandulifolia across various altitudinal regions within the Qinling Mountains. By analyzing soil bacterial α-diversity, community composition, relationships with environmental factors and plant nutrients, and predicting soil bacterial functional traits, we aim to fill critical gaps concerning the environmental and biotic crivers on microbial community structure and function. Specifically, the objectives were to: (1) compare the composition and diversity of soil bacterial communities along the altitude gradients; (2) determine the differences in environmental and plant nutrient factors that influence the soil bacterial communities; (3) clarify the functional characteristics of soil bacterial communities between the two species.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Sample Collection

This study was conducted at Huanghualing (108°52′56.9″ N and 33°47′44.6″ E, 2328 m a.s.l), located in the Niubeiliang National Nature Reserve of eastern Zhashui County, Shaanxi Province. The area is situated 31 kilometers uphill from the Qinling River basin, with mean annual precipitation (MAP) and annual mean temperature (AMT) are 2-10 °C and 850-950 mm, respectively. The frost-free period lasts for approximately 130 days.

Two plant species were selected for this study: Galinsoga quadriradiata, an invasive species known for its adaptability to diverse environmental conditions, and Artemisia lavandulaefolia, a native species commonly found in study region. These species were chosen to investigate the effects of different plant traits and ecological strategies on soil microbial communities across an altitudinal gradient.

Soils and plant organs were sampled across 6 altitudes (896, 1056, 1202, 1413, 1713, and 1889 m) with distributing of the two species. At each altitude, three randomly individuals for each species were selected in August 2022 to capture peak microbial activity, resulting in a total of 36 individuals (18 per species). After removing apoplastic material from the soil surface, we dug up all the selected individual plants. And the rhizosphere soil, tightly adhered to the root surface, was then used a sterile soft-bristled paintbrush to strip away the rhizosphere soil. The collected soil samples were divided into two parts: One was passed through a 2-mm sieve to remove roots and debris, and air-dried indoors to determine soil physicochemical properties; The remaining part was stored in an ice box and taken to the laboratory, and then stored at -80 °C for DNA extraction. The plant was divided into three parts: roots, stems, and leaves, with each part be intact and in a healthy state, and then stored in a portable ice box for transportation to laboratory. These were oven-dried at 65 ℃ to a constant weight, then milled and sifted through a 0.1 mm screen. The obtained powder was used to measure plant physiochemical parameters.

2.2. Determination of Soil and Plant Physiochemical Properties

Soil physiochemical properties included soil organic carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and soil pH. Soil organic carbon was determined by the K

2Cr

2O

7 oxidation; Total nitrogen content was analyzed based on Kjeldahl method; Total phosphorus was measured by alkali fusion–Mo-Sb anti spectrophotometric method; Total potassium was quantified by flame photometry; Potentiometric method was used to determine soil pH [

19].

Plant physiochemical properties covered organic carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus of root, stem and leaf, and were determined by the K

2Cr

2O

7 oxidation, Kjeldahl method, molybdenum antimony spectrophotometric method, respectively [

19].

2.3. Soil Bacterial Analysis

Soil DNA was extracted from 0.5 g of each soil sample using the E.Z.N.A.® Soil DNA Kit (Omega Bio-Tek, Norcross, GA, U.S.). The quality and quantity of extracted DNA were assessed using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA) and agarose gel electrophoresis. The V3–V4 hypervariable region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified using primers 338F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCA-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′). Sequencing was performed on an Illumina PE300 platform (Illumina, San Diego, USA) at Shanghai Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology Co., Ltd. The raw sequencing data were uploaded to the NCBI Sequence Rad Archive (SRA) database (Accession number: PRJNA1152501). Software UPARSE 7.1 was applied to generate operational taxonomic units (OTUs) of optimized sequences with a similarity of 97%. To minimize the impact of sequencing depth on soil bacterial diversity analysis, all sample sequences were rarefied, which could still reach an average Good’s coverage of 99.09%. All sequencing data can be found at the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI, Bethesda, MD, USA) under BioProject number PRJNA1152501 (

https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA1152501 (accessed on 17 September 2024)).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Significant differences in soil bacterial α-diversity, soil and plant physiochemical properties across different altitudes were checked using variance analysis (ANOVA). While t-test was applied to investigate the significant differences of these parameters between the two species. The program SPSS 16.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for ANOVA and t-test.

Further soil bacterial analysis was carried out using the Majorbio Cloud platform (

https://cloud.majorbio.com). The similarity of soil bacterial community structures from different samples were visualized by principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) using permutational multivariate analysis of variance (Adonis) function of the Vegan v2.5-3 package based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity. The linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe) was conducted to identify significant taxonomic differences from the phylum level between the two species (LDA score > 3, P < 0.05). To determine effects of soil and plants physiochemical properties on soil bacterial community, redundancy analysis (RDA) was performed using Vegan v2.5-3 package. Functional annotation of prokaryotic taxa (FAPROTAX) was selected to predict soil bacterial function of the two species.

3. Results

3.1. Soil Bacterial Alpha Diversity at Different Altitudes

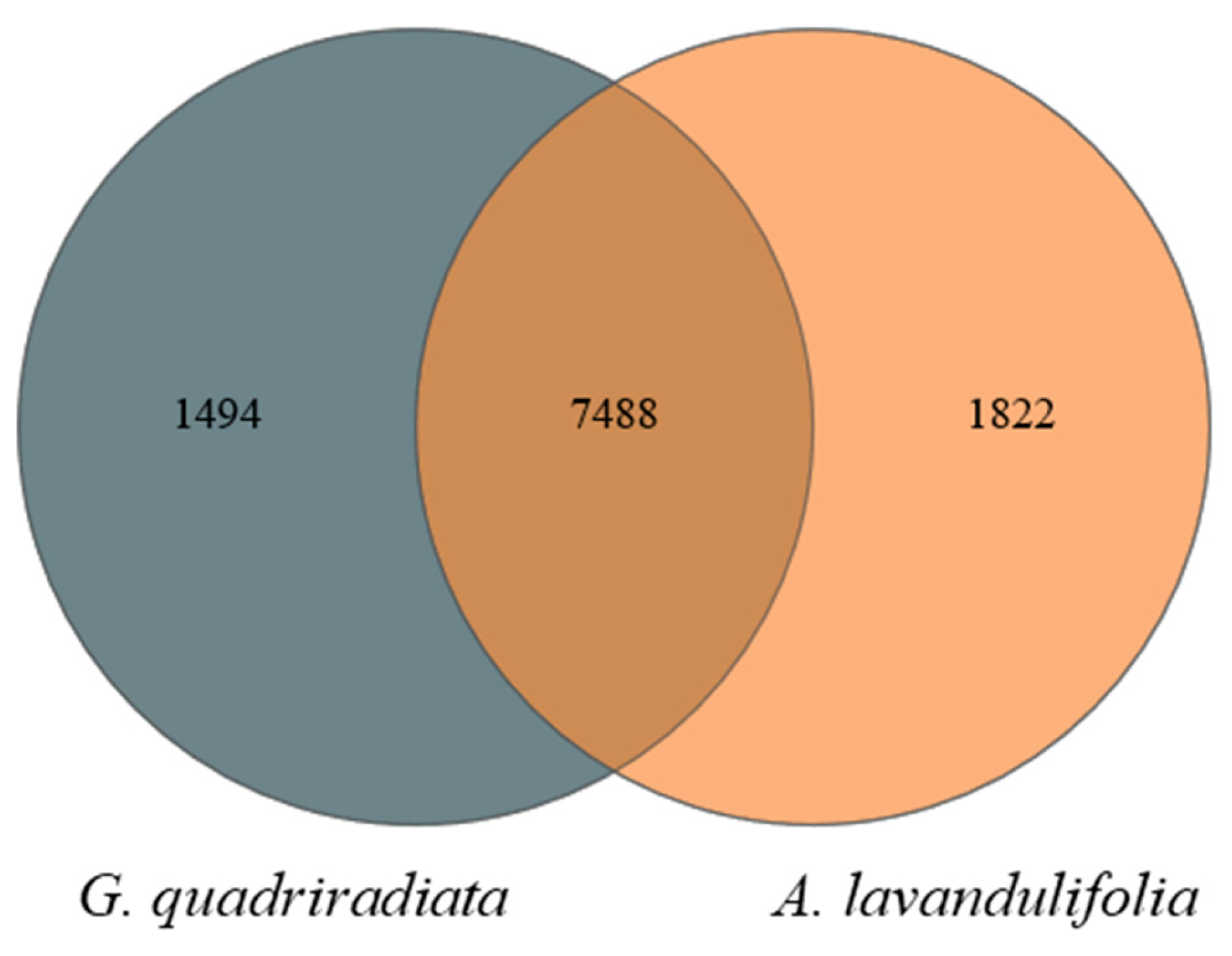

A total of 2,094,818 high-quality soil bacterial sequences were identified from all soil samples, which were clustered into 10,804 bacterial OTUs based on similarity. The Venn diagram indicated that there were 1,494 and 1,822 unique bacterial OTUs for

G. quadriradiata and

A. lavandulifolia, respectively, with 7,488 common bacterial OTUs shared between the two species (

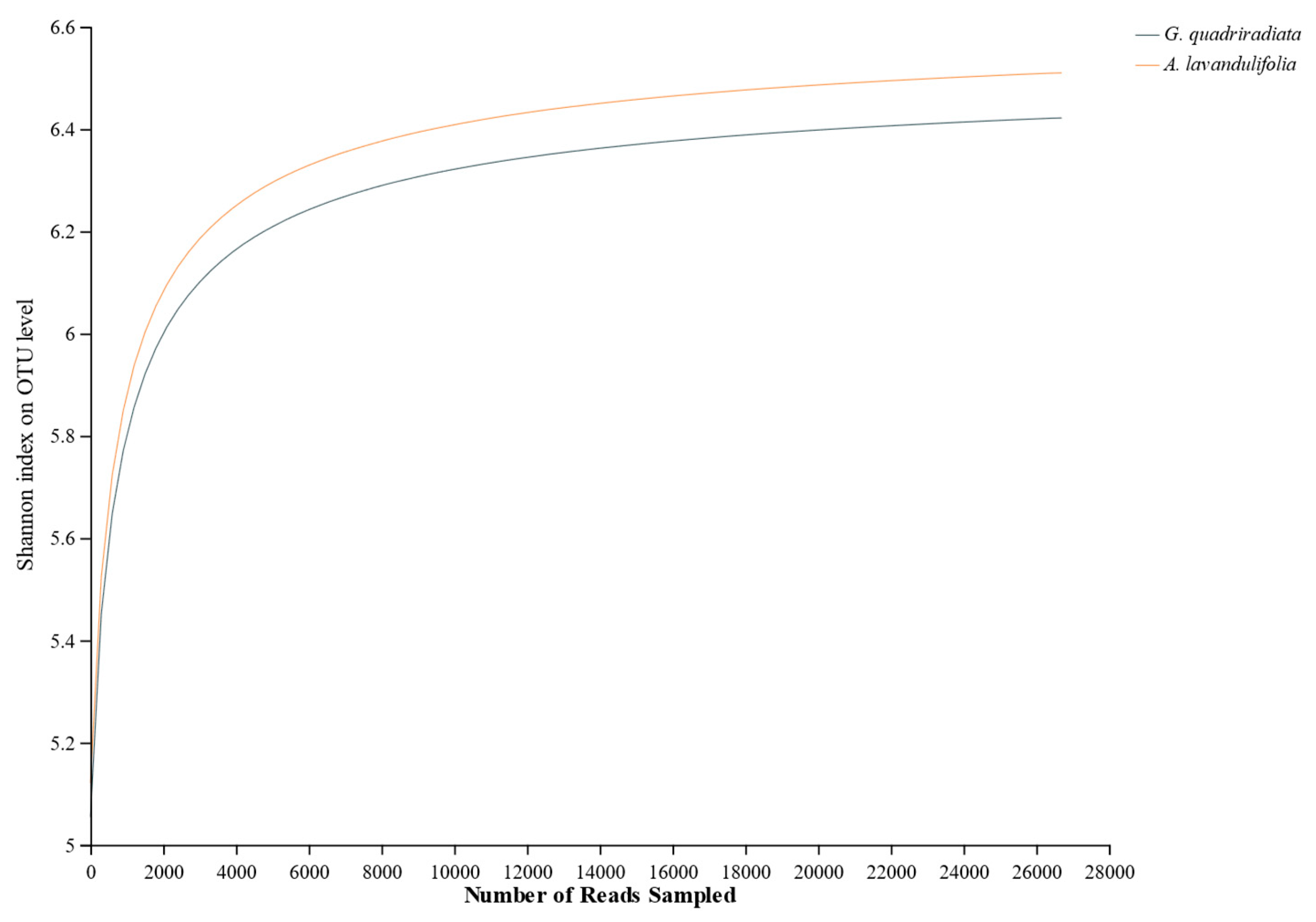

Figure 1). As the sequencing data increased, the sparsity curves of soil bacteria in both species basically flattened out (

Figure 2). This indicating that the sequencing information was sufficient, and the OTU coverage of the samples could basically reflect the structural composition of soil microbial communities of

G. quadriradiata and

A. lavandulifolia at different altitudes in Qinling Mountains. The Chao diversity and Shannon diversity of

G. quadriradiata and

A. lavandulifolia showed significant differences among different altitudes, but not between the two species (Table.1). Only at the altitude of 1,413 m, the Chao diversity index of

A. lavandulifolia was significantly higher than that of

G. quadriradiata.

Table 1.

Differences in bacterial alpha diversity among the altitudes in G. quadriradiata and A. lavandulifolia.

Table 1.

Differences in bacterial alpha diversity among the altitudes in G. quadriradiata and A. lavandulifolia.

3.2. Composition of Soil bacterial Community Differed with PLANT species

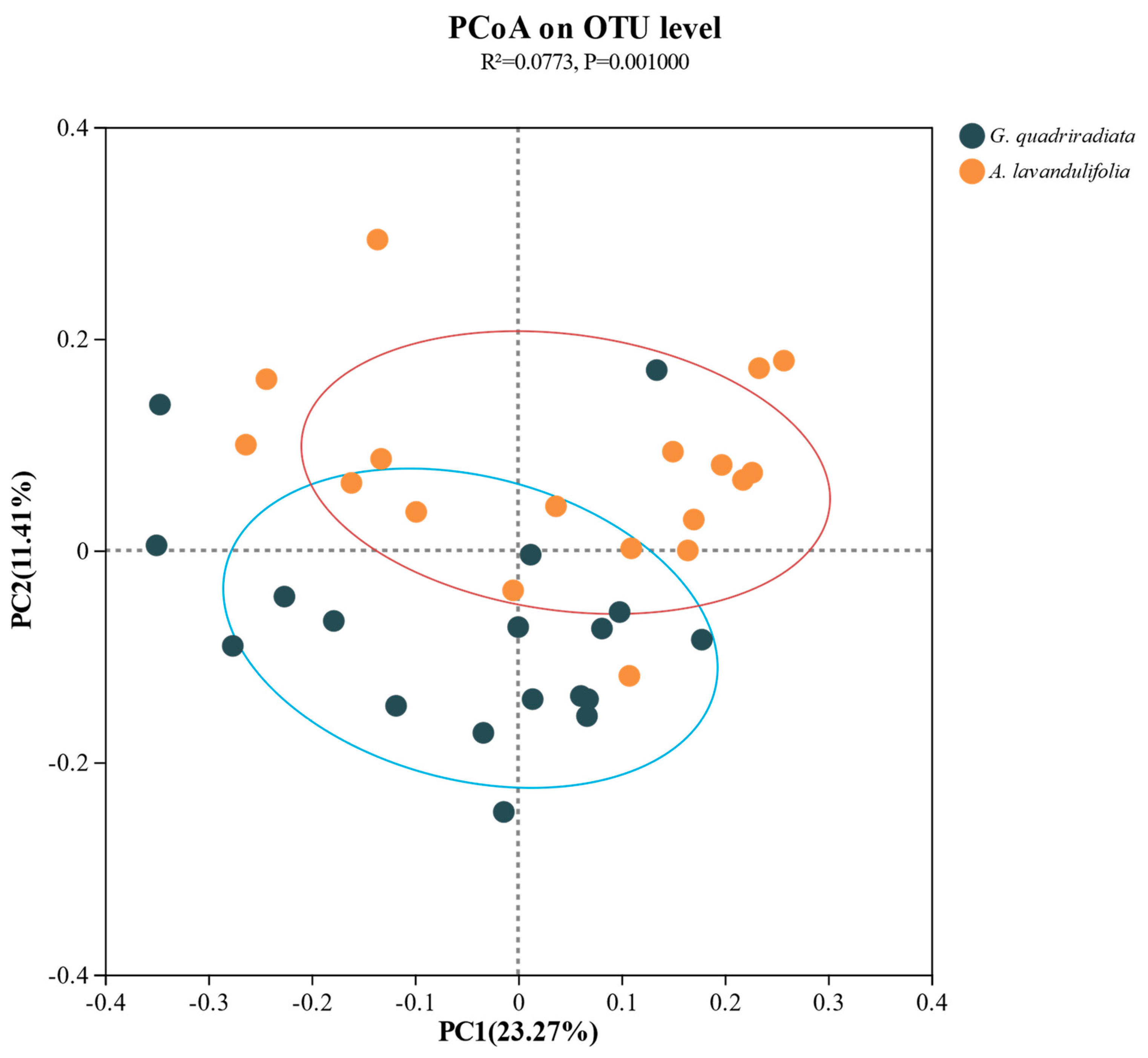

The Bray-Curtis distance algorithm was used to construct an OTU abundance table for PCoA analysis, to further analyze differences in soil bacterial communities between

G. quadriradiata and

A. lavandulifolia. The results showed that there were significant differences (P<0.01) in soil bacterial communities (at the OTU level) between the two species (

Figure 3).

40 and 39 bacterial phyla were detected in the soils of

G. quadriradiata and

A. lavandulifolia, respectively, totaling 43 bacterial phyla for the two species (

Figure 4). The top 10 dominant bacterial phyla were mainly Actinobacteriota, Proteobacteria, Acidobacteriota, Chloroflexi, Bacteroidota, Myxococcota, Gemmatimonadota, Firmicutes, Patescibacteria, Cyanobacteria. Among them, Actinobacteriota (33.11% and 30.17%), Proteobacteria (31.81% and 30.65%), and Acidobacteriota (10.37% and 14.25%) accounted for relatively high proportions. Other bacterial phyla, such as Chloroflexi and Bacteroidota, accounted for a minor fraction.

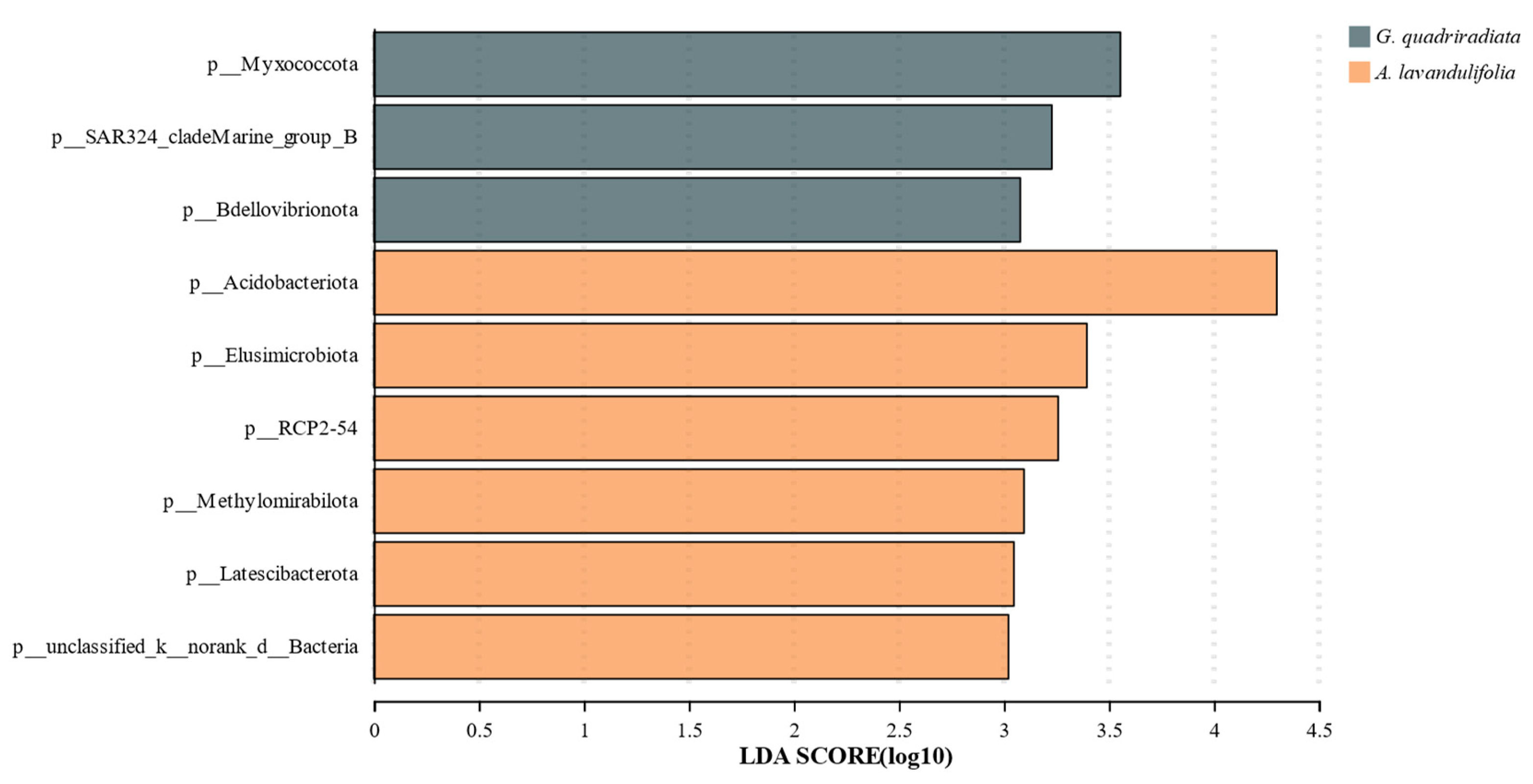

Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LefSe) (LDA score > 3) was employed to investigate the differences in soil bacterial communities between G. quadriradiata and A. lavandulifolia. The results showed that Myxococcota SAR324-cladeMarine-group-B and Bdellovibrionota were significantly enriched in G. quadriradiata, while Acidobacteriota, Elusimicrobiota, RCP2-54, Methylomirabilota, Latescibacterota, and unclassified-k-norank-d-Bacteria were significantly enriched in A. lavandulifolia. These findings indicated that most of the dominant bacterial phyla in the soil microbial communities of the two species were consistent with the LEfSe analysis results, and could serve as bacterial indicators most closely related to the microbial communities of G. quadriradiata and A. lavandulifolia.

3.3. Associations of Soil Bacterial COMMUNITY with environmental and plant factors

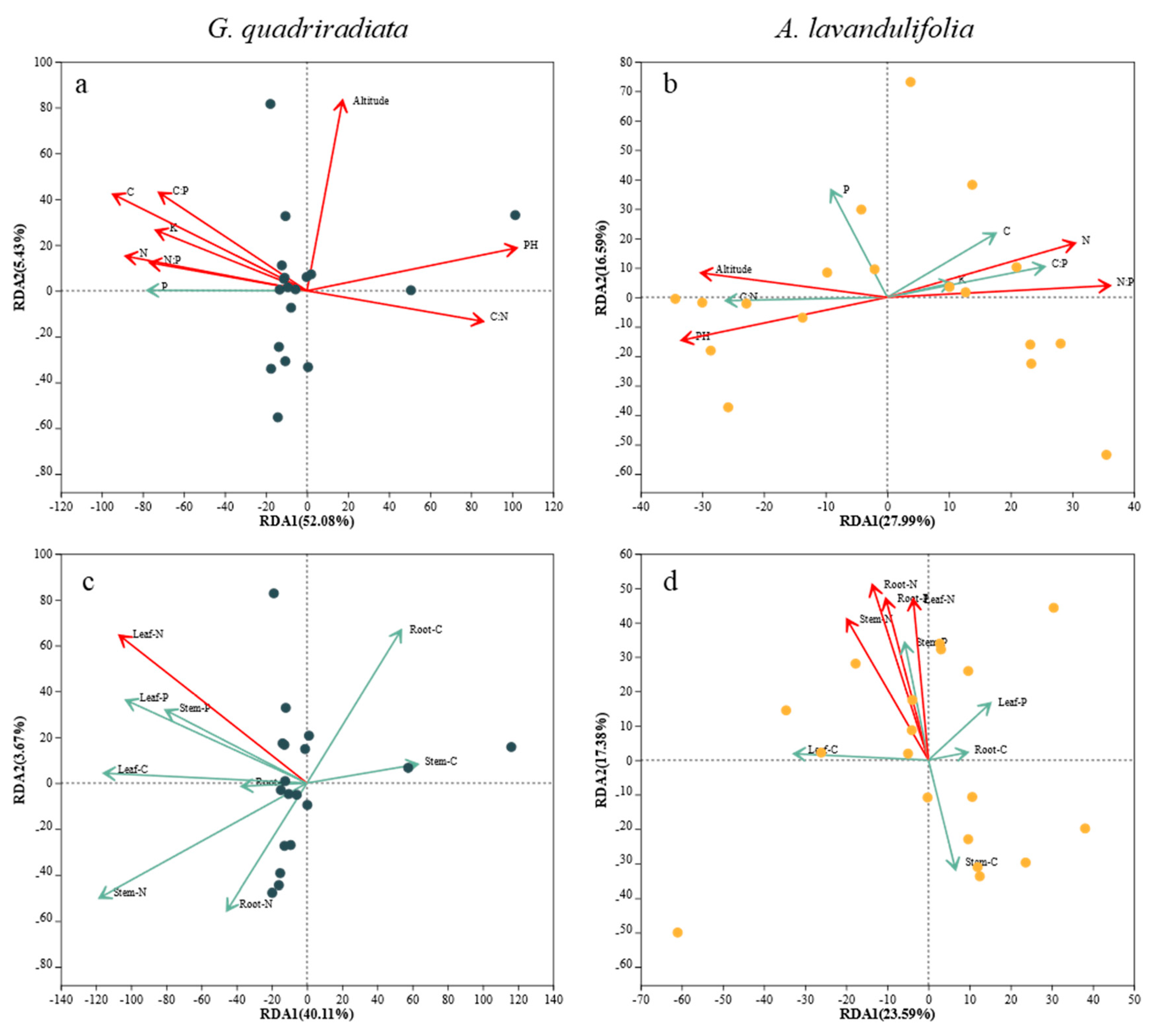

Relationships between environmental factors (including soil factors and altitude) (

Table S1) and plant factors (including roots, stems, and leaves) (

Table S2) with bacterial abundance were explored using RDA analysis. For environmental factors, the first and second axes of RDA explained 57.51% and 44.58% of the variation in bacterial abundance in

G. quadriradiata and

A. lavandulifolia, respectively. For plant factors, the first and second axes of RDA respectively explained 43.78% and 40.97%. Compared to plant indicators, environmental factors had a greater impact on plant soil bacterial abundance. Correlation analysis indicated that for

G. quadriradiata, soil pH, C, N, K, C:N, N:P, C:P, altitude and leaf N significantly affected bacterial community structures. For

A. lavandulifolia, the significant factors were soil pH, N, N:P, altitude, root N, P, stem N, and leaf N.

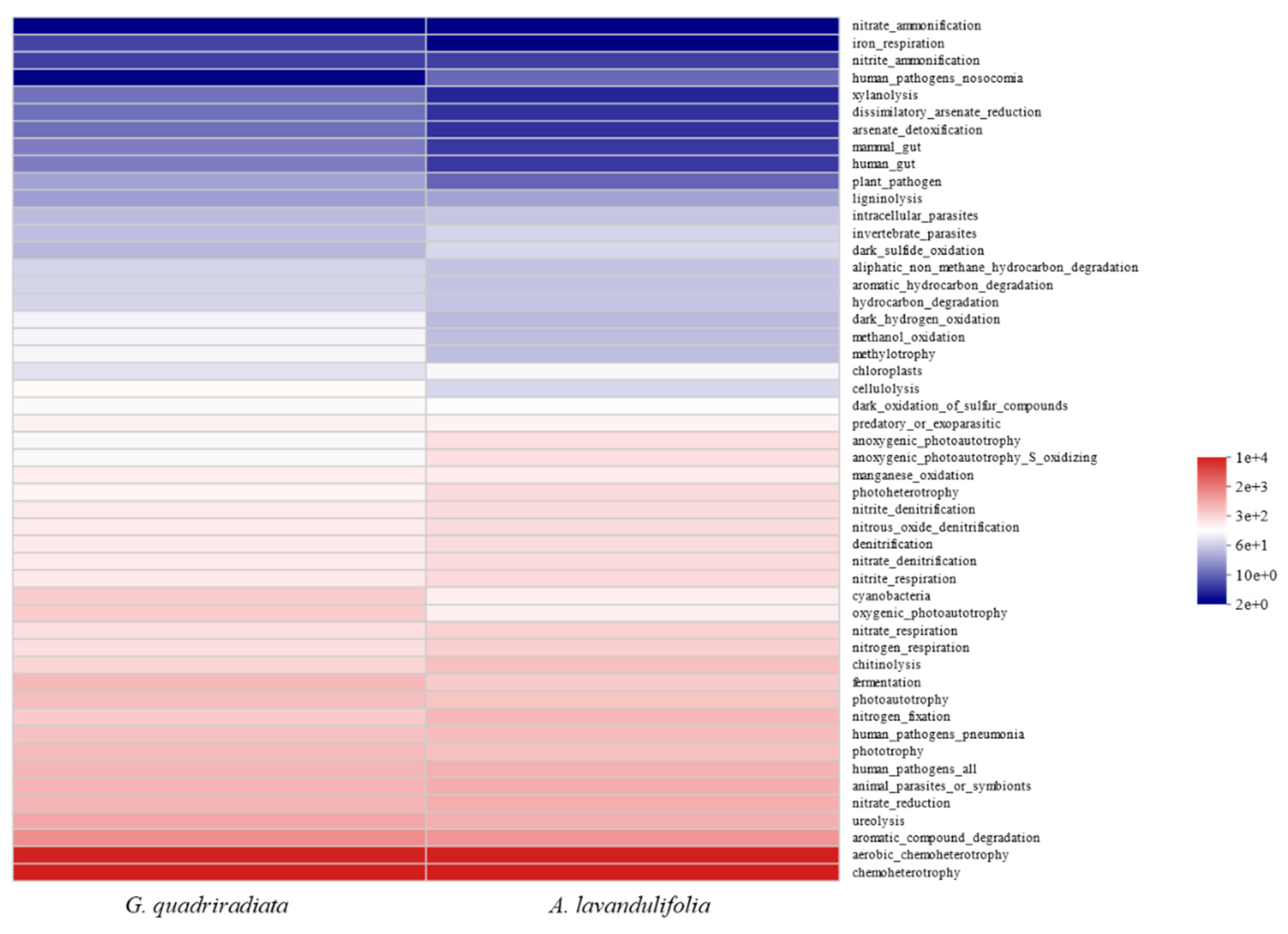

3.4. Functional Analyses of Soil Bacteria

The FAPROTAX database was utilized to predict the functions of soil bacterial communities, resulting in the identification of 61 functional groups. The relative abundances of the top 15 functional groups accounted for 89.62% and 88.88% of the total relative abundances in G. quadriradiata and A. lavandulifolia, respectively. Chemoheterotrophy and aerobic-chemoheterotrophy were the primary metabolic functional groups of soil bacteria in the two species soils. In the soil of G. quadriradiata, the relative abundances of metabolic functional groups such as dark_hydrogen_oxidation, methanol_oxidation, methylotrophy, cellulolysis, cyanobacteria, oxygenic_photoautotrophy, and fermentation were higher than those in A. lavandulifolia. Conversely, in the soil of A. lavandulifolia, the relative abundances of various metabolic functional groups (such as anoxygenic_photoautotrophy, anoxygenic_photoautotrophy_S_oxidizing, dark_sulfide_oxidation, photoheterotrophy, chitinolysis, invertebrate_parasites, nitrogen_fixation, chloroplasts, denitrification, nitrate_denitrification) were higher, with most of them closely related to nitrogen fixation, nitrification, and denitrification processes.

4. Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of soil bacterial diversity and community composition in relation to plant species and altitude in the Qinling Mountains. By comparing an invasive species, G. quadriradiata with a native species, A. lavandulifolia, across an altitudinal gradient, we discovered that both plant species and altitude significantly influence the structure and function of soil microbial communities. These findings not only enrich our understanding of plant-microbe interactions in mountainous ecosystems, but also offer insights into how these interactions may be influenced by environmental gradients, with implications for ecosystem management and conservation efforts.

4.1. Soil Bacterial Diversity and Composition in Relation to Plant Species and Altitude

This study revealed pronounced differences in soil bacterial diversity and community composition between

G. quadriradiata and

A. lavandulifolia. Notably, the shared OTUs between the two species indicated that, while the overall microbial pool exhibits similarities, specific environmental conditions and plant traits drove distinct microbial community structures (

Figure 1). These findings concurred with previous studies, which reported altitude as a key factor modulating soil microbial diversity, attributed to variations in temperature, moisture, and nutrient availability [20-22]. However, the statistically difference in Chao diversity between the two species was only observed at 1,413 meters, potentially due to the plant's physiological adaptations or specific interactions with the soil microbiome (

Table 1).

The PCoA analysis showed distinct microbial community structures between the two species (

Figure 3), supporting the opinion that plant species could significantly shape soil microbial communities through root exudates, litter inputs, and nutrient cycling processes [23, 24]. This coincides with the concept that plants influenced microbial communities in ways that could affect plant health and ecosystem functions [12, 25-27]. However, the current study deeply analyzed the specific bacterial phyla, such as Myxococcota and Acidobacteriota, which exhibited differential enrichment patterns in the soils of

G. quadriradiata and

A. lavandulifolia, respectively (

Figure 4). This observation might reflect functional specialization of these microbial communities, with potential implications for nutrient cycling and overall soil health. The enrichment of Myxococcota in

G. quadriradiata soils might enhance organic matter decomposition (

Figure 5) [28, 29]. Whereas the higher abundance of Acidobacteriota in

A. lavandulifolia soils could be associated with more acidic conditions, fostering nutrient cycles like nitrogen fixation (

Figure 5) [30, 31]. The results demonstrated that the two species might contribute uniquely to soil ecosystem functions, which could affect plant succession patterns and competition dynamics within the Qinling Mountains ecosystem.

4.2. Environmental and Plant Factors Driving Microbial Communities

RDA analysis revealed the significant role of altitude in shaping soil microbial communities, which further emphasized the importance of abiotic factors in structuring microbial populations (

Figure 6). Among the environmental variables, soil pH and nutrient content emerged as major determinants of microbial community composition. This is in line with previous research that pinpointed soil pH as a primary driver of bacterial community structure owing to its profound influence on microbial metabolism and nutrient availability [32, 33].

Notably, our study also highlighted the significant influence of plant traits, particularly leaf nitrogen content, on microbial community structure. The correlation between nitrogen content in plant tissues and the abundance of nitrogen-cycling bacteria implied that plants could actively modulate microbial functions to meet their nutritional requirements. This interplay between plant traits and microbial communities underscores the complexity of plant-soil interactions and indicates that managing plant nutrient status could be a key strategy for influencing soil microbial health [34, 35].

4.3. Functional Implications of Soil Microbial Communities

Interactions between bacteria and plants are ubiquitous in nature. The rhizosphere, one of the most complex ecosystems on Earth, is a narrow zone rich in bacteria surrounding plant roots [

36]. All substances absorbed and released from the soil by plants must traverse the rhizosphere, where their flow, transport and reaction are also influenced by this specific region [

37]. Consequently, the composition and function of rhizosphere bacteria exhibits a close relation [

38]. Andreote & Pereira E Silva emphasized that plants are highly dependent on the bacteria surrounding the root system, which can promote plant growth and protect plants under stress conditions [

39], It can be considered that the changes in the bacteria community and composition around plant roots have a stronger influence in plant health.

In the current study, the functional predictions from the FAPROTAX database revealed that soil bacterial communities were primarily involved in chemoheterotrophy and aerobic chemoheterotrophy for both species (

Figure 7), which were crucial for organic matter decomposition and carbon cycling [

40]. The relative abundances of bacterial functional groups including dark_hydrogen_oxidation, methanol_oxidation, methylotrophy, cellulolysis, cyanobacteria, oxygenic_photoautotrophy, and fermentation were significantly higher in the rhizosphere of

G. quadriradiata, mainly contributing to energy acquisition, carbon and nitrogen transformation, and serving as primary producers by synthesizing organic matter to provide the foundation for the food chain [

41]. In contrast, the bacterial functional groups in the soil of

A. lavandulifolia like anoxygenic_photoautotrophy, dark_sulfide_oxidation, photoheterotrophy, nitrite/nitrate respiration/ denitrification, showed key roles as a carbon source and energy supply in anoxic or hypoxic environments, as well as nitrogen fixation and denitrification [42, 43]. The enhanced nitrogen cycling potential in

A. lavandulifolia soils could improve nitrogen availability, which might influence interspecific competition and succession, especially in nitrogen-limited environments [44, 45]. Furthermore, the higher rates of organic matter decomposition in

G. quadriradiata soils might accelerate carbon turnover, affecting soil organic matter content and long-term soil fertility [46, 47].

4.4. Implications of Species-Specific Diversity and Function Patterns of Soil Microbial Communities

The distinct microbial communities associated with G. quadriradiata and A. lavandulifolia demonstrated that these species could differentially influence soil health and ecosystem functions, with potential implications for plant community dynamics in the Qinling Mountains. Moreover, altitude, as a crucial environmental factor, can lead to significant changes in climate, vegetation, and soil properties over relatively short distances, impacting soil microbial growth and resource acquisition. The interactions among microorganisms may become more complex and intense, potentially triggering a chain reaction that influences plant health and ecosystem resilience. Understanding these interactions is crucial for controlling invasive species and preserving biodiversity in this region [48-51].

Our study only examined the distribution patterns of soil bacteria community, lacking an analysis of archaea, fungi, and protists, as well as their interactions. Furthermore, research on plants, particularly exotic species, predominantly focus on a single species. Future attention should be directed towards the impact of community diversity on the spread of single or multiple invasive species, and further reveal the correlation between specific functional microorganisms and invasion mechanisms.

5. Conclusions

Our study revealed the distribution patterns and driving factors of soil bacterial communities of an invasive species G. quadriradiata and a native species A. lavandulifolia at different altitudes. The findings showed differences in soil bacterial α-diversity among different altitudes were significant, but insignificant between invasive and native species. However, at the OTU level, there were obvious differences in soil bacterial communities between the two species. Soil bacterial abundance of both species was influenced by altitude, soil physicochemical properties (e.g., soil pH, N, N:P), and species-specific factors (e.g., leaf N content). Functional analysis indicated that chemoheterotrophy and aerobic-chemoheterotrophy were the primary metabolic functional groups of soil bacteria in both G. quadriradiata and A. lavandulifolia. The abundance of metabolic functional groups closely related to nitrogen fixation, nitrification, and denitrification in the soil of A. lavandulifolia was higher than that in G. quadriradiata. While soil bacteria in G. quadriradiata contributed more to organic matter decomposition. The structure and function of bacterial communities played crucial roles in the productivity and health of soil ecosystems. These findings demonstrated that plant species and altitude were key properties of soil bacterial community structure and function. Future research could integrate aboveground vegetation communities and litter with underground microbial communities to deeply understand the soil-microbe-plant interactions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Table S1: Soil characteristics along the altitude gradient in

G. quadriradiata and

A. lavandulifolia; Table S2: Plant characteristics along the altitude gradient in

G. quadriradiata and

A. lavandulifolia.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W., J.L., M.Y.; data collection and curation, W.X., X.W.; results analysis and interpretation, J.L., Y.L., Y.W.; writing-original draft, J.L.; writing-review and editing, Y.W., M.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Science and Technology Program of the Shaanxi Academy of Sciences (2023k-24, 2024p-13, 2023k-02); Natural Science Basic Research Program of Shaanxi Province (2023-JC-QN-0230); Key Research and Development Program of Shaanxi Province (2020ZDLSF06-01); Project of the First Investigation of Wild Plants Resources in Xi'an (K6-2207039); Xi'an Science and Technology Project (2024JH-NYYB-0065).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bardgett, R.D.; Van der Putten, W.H. Belowground biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Nature, 2014, 515(7528): 505-511. [CrossRef]

- Bender, S.F.; Wagg, C.; van der Heijden, M.G.A. An underground revolution: Biodiversity and soil ecological engineering for agricultural sustainability. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 2016, 31(6): 440-452. [CrossRef]

- Wagg, C.; Schlaeppi, K.; Banerjee, S. ; E.Kuramae E.; van der Heijden M.G.A. Fungal-bacterial diversity and microbiome complexity predict ecosystem functioning. Nature Communications, 2019, 10(1): 4841. [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Reich, P.B.; Trivedi, C. , et al. Multiple elements of soil biodiversity drive ecosystem functions across biomes. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2020, 4(2): 210-220. [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.C.; Ni, Y.Y.; Liang, W.J.; Wang, J.J.; Chu, H.Y. 2015. Distinct soil bacterial communities along a small-scale elevational gradient in alpine tundra. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2015, 6: 582. [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.X.; Bing, H.J.; Fang, L.C.; Wu, Y.H.; Yu, J.L.; Shen, G.T.; Jiang, M.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.C. Diversity patterns of the rhizosphere and bulk soil microbial communities along an altitudinal gradient in an alpine ecosystem of the eastern Tibetan Plateau. Geoderma, 2019, 338: 118-127. [CrossRef]

- Lladó, S.; López-Mondéjar, R.; Baldrian, P. Forest soil bacteria: diversity, involvement in ecosystem processes, and response to global change. Microbiology and molecular biology reviews, 2017, 81(2). [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y.; Yang, T.; Zhang, K.; Shen, C.; Chu, H. Fungal communities along a small-scale elevational gradient in an alpine tundra are determined by soil carbon nitrogen ratios. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2018, 9: 1815. [CrossRef]

- Kui, L.; Sun, H.; Lei, Q.; Gao, W.; Bao, L.J.; Chen, Y.X.; Jia, Z.J. Soil microbial community assemblage and its seasonal variability in alpine treeline ecotone on the eastern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Soil Ecology Letters, 2019, 1, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.W.; Li, J.R.; L, S.F.; Chen, W.S.; Ding, H.H.; Xiao, S.Y.; Li, Y.Y. Elevational distribution patterns and drivers of soil microbial diversity in the Sygera Mountains, southeastern Tibet, China. 2023, 221:106738. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Li, B.; Wu, J.H.; Hu, S.J. Invasive plants differentially affect soil biota through litter and rhizosphere pathways: a meta-analysis. Ecology letters, 2019, 22: 200-210. [CrossRef]

- Bardgett, R.D.; van der Putten, W.H. Belowground biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Nature, 2014, 515:505-511. [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, A.; Zheng, W.; Rillig, M.C. Soil biota contributions to soil aggregation[J]. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2017, 1(12): 1828-1835. [CrossRef]

- Saha, I.; Datta, S.; Biswas, D. Exploring the role of bacterial extracellular polymeric substances for sustainable development in agriculture. Current Microbiology, 2020, 77(11): 3224-3239. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Huang, C.H.; Li, W.; Wu, W.X.; Tang, Z.R.; Tian, Y. Xi B.D. Ammonia assimilation is key for the preservation of nitrogen during industrial-scale composting of chicken manure. Waste Management, 2023, 170:50-61. [CrossRef]

- Hilmers, T.; Friess, N.; Bässler, C.; Heurich, M.; Brandl, R.; Pretzsch, H.; Seidl, R.; Müller, J. Biodiversity along temperate forest succession. Journal of Applied Ecology, 2018, 55: 2756-2766. [CrossRef]

- Coban, O.; De Deyn, G.B.; van der Ploeg, M. Soil microbiota as game-changers in restoration of degraded lands. Science, 2022, 375: eabe0725. [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J.L.; Yue, M.; Mao, Z.X.; Wang, Y.C. Study on invasion status and risk assessment of alien plants in Qinling Mountains. Ecology and Environmental Sciences, 2023, 32(9): 1585-1594. (in Chinese). [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.D. Soil and agricultural chemistry analysis; Chinese Agriculture Press: Beijing, PRC, 2000; pp. 14–109. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.T.; Cao, P.; Hu, H.W.; Li, J.; Han, L.L.; Zhang, L.M.; Zheng, Y.M.; He, J.Z. Altitudinal distribution patterns of soil bacterial and archaeal communities along Mt. Shegyla on the Tibetan Plateau. Microbial Ecology, 2015, 69(1): 135-145. [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.W.; Guo, Q.Q.; Li, H.E.; Luo, S.Q.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Yao, S.; Fan, X.; Sun, X.G.; Qi, Y.J. Dynamics of soil nutrients, microbial community structure, enzymatic activity, and their relationships along a chronosequence of Pinus massoniana plantations. Forests, 2021, 12(3): 376. [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.X.; Kong, W.D.; Liu, J.B.; Zhao, J.X.; Du, H.D.; Zhang, X.Z.; Xia, P.H. Diversity and distribution of autotrophic microbial community along environmental gradients in grassland soils on the Tibetan Plateau. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2015, 99(20): 8765-8776. [CrossRef]

- Beare, M.H.; Neely, C.L.; Coleman, D.C.; Hargrove, W.L. Characterization of a substrate-induced respiration method for measuring fungal, bacterial and total microbial biomass on plant residues. Agriculture Ecosystems and Environment, 1991, 34(1-4): 65-73. [CrossRef]

- Strecker, T.; Barnard, R.L.; Niklaus, P.A.; Scherer-Lorenzen, M.; Weigelt, A.; Scheu, S.; Eisenhauer, N. Effects of plant diversity, functional group composition, and fertilization on soil microbial properties in experimental grassland. PLoS One, 2015, 10(5): e0125678. [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, M.; Frey, B.; Mayer, J.; Mäder, P.; Widmer, F. Distinct soil microbial diversity under long-term organic and conventional farming. The ISME Journal, 2015, 9(5): 1177-1194. [CrossRef]

- Duffy, J.E.; Godwin, C.M.; Cardinale, B.J. Biodiversity effects in the wild are common and as strong as key drivers of productivity. Nature, 2017, 549: 261-264. [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Reich, P.B.; Trivedi, C.; et al. Multiple elements of soil biodiversity drive ecosystem functions across biomes. Nature Ecology Evolution, 2020, 4: 210-220. [CrossRef]

- Canarini, A.; Kiær, L.P.; Dijkstra, F.A. Soil carbon loss regulated by drought intensity and available substrate: A meta-analysis. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2017, 112: 90-99. [CrossRef]

- Waite, D.W.; Chuvochina, M.; Pelikan, C.; et al. Proposal to reclassify the proteobacterial classes Deltaproteobacteria and Oligoflexia, and the phylum Thermodesulfobacteria into four phyla reflecting major functional capabilities [J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2020, 70: 5972-6016. [CrossRef]

- Hemp, J.; Lücker, S.; Schott, J.; Pace, L.A.; Johnson, J.E.; Schink, B.; Daims, H.; Fischer, W.W. Genomics of a phototrophic nitrite oxidizer: insights into the evolution of photosynthesis and nitrification. The ISME Journal, 2016, 10: 2669-2678. [CrossRef]

- Conradie, T.A.; Jacobs, K. Distribution patterns of acidobacteriota in different fynbos soils. Plos One, 2021, 16(3): e0248913. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.J.; Hu, A.; Meng, F.F.; Zhao, W.Q.; Yang, Y.F.; Soininen, J.; Shen, J.; Zhou, J.Z. Embracing mountain microbiome and ecosystem functions under global change. New Phytologist, 2022, 234(6): 1987-2002. [CrossRef]

- He, J.H.; Tan, X.P.; Nie, Y.X.; Ma, L.; Liu, J.X.; Mo, J.M.; Leloup, J.L.; Nunan, N.; Ye, Q.; Shen, W.J. Distinct responses of abundant and rare soil bacteria to nitrogen addition in tropical forest soils. Microbiology Spectrum, 2023, 11(1): e0300322. [CrossRef]

- Bardgett, R.D.; Manning, P.; Morriën, E.; de Vries, F.T. Hierarchical responses of plant-soil interactions to climate change: Consequences for the global carbon cycle. Journal of Ecology,2013,101:334-343. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.M.; Wang, Y.; He, N.P.; Ye, Z.Q.; Chen, C.; Zang, R.G.; Feng, Y.M.; Lu, Q.; Li, J.W. Plant functional traits regulate soil bacterial diversity across temperate deserts. Science of the Total Environment, 2020, 715: 136976. [CrossRef]

- Vetterlein, D.; Carminati, A.; Kögel-Knabner, I.; Bienert, G.P.; Smalla, K.; Oburger, E.; Schnepf, A.; Banitz, T.; Tarkka, M.T.; Schlüter, S. Rhizosphere spatiotemporal organization-A key to rhizosphere functions. Frontiers in Agronomy, 2020,2: 8. [CrossRef]

- York, L.M.; Carminati, A.; Mooney, S.J.; Ritz, K.; Bennett, M.J. The holistic rhizosphere, integrating zones, processes, and semantics in the soil influenced by roots. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2016, 67(12): 3629-3643. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.B.; Peng, S.C.; Li, Z.Q.; Zhang, D.J.; Zhu, Y.T.; Li, X.Q.; Hong, M.Y.; Li, W.C.; Lu, P.L. Characterization of microbial communities and functions in shale gas wastewaters and sludge: implications for pretreatment. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2022, 424(Part D), 127649. [CrossRef]

- Andreote, F.D.; Pereira E Silva, M.C. Microbial communities associated with plants: learning from nature to apply it in agriculture. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 2017, 37, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivett, D.W.; Bell, T. Abundance determines the functional role of bacterial phylotypes in complex communities. Nature Microbiology, 2018, 3(7): 767-772. [CrossRef]

- Virk, A.L.; Lin, B.J.; Kan, Z.R.; Qi, J.Y.; Dang, Y.P.; Lal, R.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, H.L. Chapter two - simultaneous effects of legume cultivation on carbon and nitrogen accumulation in soil. Advances in Agronomy, 2022, 171, 75–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Yang, S.; Wang, Z.R.; Feng, X.; Liu, H.Y.; Jiang, Y. Variations in soil bacterial taxonomic profiles and putative functions in response to straw incorporation combined with N fertilization during the maize growing season. Agriculture Ecosystems & Environment, 2019, 283: 106578. [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Wang, H.; Feng, M.; Cheng, H.; Yang, Q.; Yan, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, M. The coupling response between different bacterial metabolic functions in water and sediment improve the ability to mitigate climate change. Water, 2022, 14(8): 1203. [CrossRef]

- Sinsabaugh, R.L.; Hill, B.H.; Follstad Shah, J.J. Ecoenzymatic stoichiometry of microbial organic nutrient acquisition in soil and sediment. Nature, 2009, 462, 795–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinsabaugh, R.L. , Shah, J.J.F., Findlay, S.G., Kuehn, K.A., Moorhead, D.L., 2015. Scaling microbial biomass, metabolism and resource supply. Biogeochemistry, 122(2), 175-190.

- Liang, C.; Schimel, J.P. , Jastrow, J.D. The importance of anabolism in microbial control over soil carbon storage. Nature Microbiology, 2017, 2(8): 17105. [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.X.; Fang, L.C.; Guo, X.B.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.Q.; Li, P.F.; Zhang, Y.J.; Zhang, X.C. Responses of soil microbial communities to nutrient limitation in the desert-grassland ecological transition zone. Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 642: 45-55. [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.X.; Kong, W.D.; Liu, J.B.; Zhao, J.X.; Du, H.D.; Zhang, X.Z.; Xia, P.H. Diversity and distribution of autotrophic microbial community along environmental gradients in grassland soils on the Tibetan Plateau. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2015, 99(20): 8765-8776. [CrossRef]

- Bahram, M.; Hildebrand, F.; Forslund, S.K.; et al. Structure and function of the global topsoil microbiome. Nature, 2018, 560(7717): 233-237. [CrossRef]

- Bhople, P.; Keiblinger, K.; Djukic, I.; Liu, D.; Zehetner, F.; Zechmeister-Boltenstern, S.; Georg Joergensen, R.; Murugan, R. Microbial necromass formation, enzyme activities and community structure in two alpine elevation gradients with different bedrock types. Geoderma, 2021, 386: 114922. [CrossRef]

- Mou, Z.J.; Kuang, L.H.; He, L.F.; et al. Climatic and edaphic controls over the elevational pattern of microbial necromass in subtropical forests. Catena, 2021, 207: 105707. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).