1. Introduction

Forests have maintained long-standing, sustainable relationships with humans, providing products and services through their cultural, social, and ecological functions [

1,

2,

3]. Forest culture (FC), which consists of products and services, provides humans with individual and social values globally—these comprise Western values such as ecological, economic, and sociocultural values [

4]; and Eastern values such as physical and mental values [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]). Identifying these values can contribute to the sustainable development of the society [

10,

11,

12]. The United Nations promotes sustainable development globally through the international agenda of the sustainable development goals (SDGs), specifically outlining sustainable consumption and production in SDG 12 [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Notably, according to the sub-targets of SDG 12, forests are closely related to sustainable tourism development, which can contribute to local economies, environmental protection, and community empowerment [

13,

17,

18].

Covering 63% of the land area of South Korea, forests have been the foundation of the spirit and culture of the country. The definition of FC provided in Article 2 of Korea’s Forest Recreation Act refers to the totality of mental and material products derived from the interaction between forests and humans, including traditions, heritage, and forest-related lifestyles, as well as all activities that utilize, view, enjoy, experience, and create forests [

19]. Despite the importance and significance of the cultural value of Korean forests, the public’s awareness of FC is low at 37.7%, whereas the interest in FC is high at 81.9% [

20]. This is because few studies have investigated how the cultural value of forests can be directly or indirectly consumed as products by individuals or communities.

Recently, Korean cultural content (e.g., K-pop, K-food) has been spreading globally, and its economic and social impact has been rapidly increasing. In addition, the importance of the cultural content industry, which is based on high technology and creativity, is gaining even more importance and is contributing significantly to the country’s status. Forests have high value for conservation and utilization, and FC also has high value for utilization as a unique content [

21]. To enhance the value expression and utilization of forest cultural resources as cultural products, identifying how FC is converted into products based on the pursued values (PVs) of Koreans in FC is necessary. While FC plays an essential role in South Korea, similar cultural ecosystems exist in other regions, making this study relevant for developing global strategies in forest-related cultural productization and sustainable policy-making.

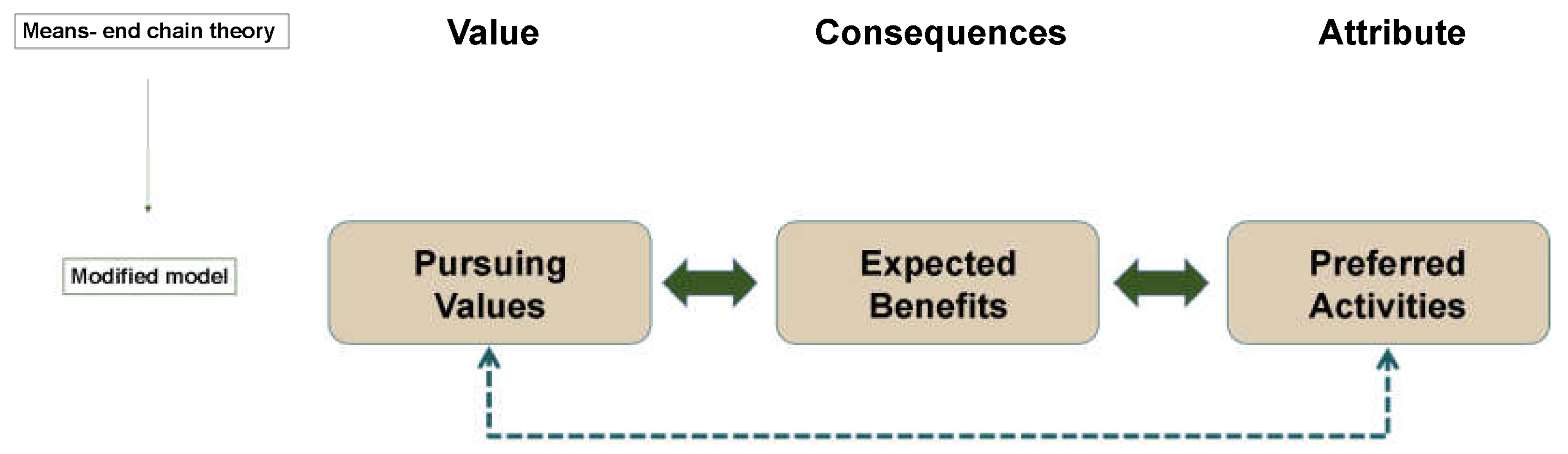

The Means-End Chain (MEC) theory by Gutman [

22] explains consumer decision-making as a cognitive process that links product attributes to personal consequences, which ultimately lead to desired values. According to this theory, consumers select products not only based on their functional attributes but because these attributes help them achieve personal goals and fulfill deeper values. Recently, MEC theory was advanced to analyze the deep values and motivations of consumers and proposed methods to incorporate them into marketing and advertising strategies [

23]. Furthermore, MEC theory has been extensively applied across various sectors, including tourism, culture, and the arts, to understand how products and experiences resonate with consumer values [

24,

25,

26]. Previous research suggests that the reverse application of MEC theory emphasizes the significance of emotional and abstract values in consumer decision-making, particularly in the context of cultural and artistic products [

24]. However, in the forestry sector, this approach remains underexplored.

Previous studies have qualitatively assessed consumer values using MEC theory. However, quantitative research on FC products and consumer values based on MEC theory are lacking. Thus, to explore how forest cultural values impact consumption behavior, we employed MEC theory, linking product attributes to personal values and outcomes. MEC theory provides a framework for analyzing how FC benefits translate into consumer preferences and activities.

The study aims were as follows: (1) To empirically investigate the perceived value, pursued benefits, and product attributes of FC and identify their respective components and (2) to investigate the impact of the perceived value of FC on pursued benefits and product attributes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Model Development

The research methods were based on a literature review in the first step, which led to the selection of 11 pursued forest values , four expected forest benefits (positive functions), and 19 FC recreational activity indicators. In the second step, an online survey was conducted with 1,700 participants nationwide to assess their perceptions on a five-point Likert scale for each variable. In the third step, we analyzed the collected data. The study methods and analysis framework are shown in

Figure 1. The study model was structured as shown in

Figure 1 to identify the subdimensions of the PV of FC, expected benefits, and preferred activities (PAs). By applying MEC theory and laddering method [

22] in reverse, their relationships and the consumption structure of FC were determined.

2.2. MEC Theory

MEC theory is based on the notion that consumers do not simply consider physical attributes when choosing a product or service, but that they value the abstract and conceptual benefits or consequential value that those attributes provide. This theory was first proposed by Gutman [

22], who claimed that consumers make purchase decisions based on the connection between the physical attributes of a product and the deeper value that those attributes provide rather than simply because of physical attributes. In other words, the theory states that consumers value the connection among the attributes of a product, the consequences resulting from those attributes, and the value that those consequences create [

22,

23]. Later, Olson and Reynolds [

24] advanced MEC theory to analyze the deep values and motivations of consumers and proposed methods to incorporate them into marketing and advertising strategies. Furthermore, they examined the applicability of MEC theory to a wide range of products and services, demonstrating its value as an academic and managerial tool.

MEC theory has been established as an important tool for understanding consumer behavior, and its value has been recognized not only in academic research but also in practical applications [

22,

23]. The theory is particularly useful in marketing, brand strategy, consumer engagement, and behavioral analysis and can contribute to understanding the deep values and motivations of consumers, leading to the development of effective marketing strategies. It also underlines the multidimensional nature of consumer behavior and can provide critical insights for future research and practice [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31].

Shin and Lee [

24] applied MEC theory and the laddering method in a reversed manner, emphasizing that cultural and artistic products, unlike other consumer goods, are highly dependent on the perception of value by consumers. They first recognized the abstract and emotional value of cultural products and then analyzed the pathway through which value leads to concrete pursued benefits and physical attributes. Their study demonstrated that when selecting cultural and artistic products, consumers prioritized emotional, abstract, and ideological attributes over physical attributes. Additionally, the same attributes could be interpreted in multiple ways, with different consumers pursuing different benefits or values. Furthermore, they emphasized that even if the core attributes of cultural and artistic products have physical traits, consumers seek the emotional, abstract, and conceptual attributes of the products, thus arguing that MEC theory should be applied in reverse.

Considering the approach of previous studies, we applied MEC theory in reverse in the current study to consider the unique characteristics of forest cultural products. Forest cultural products can never be fully explained by simple physical attributes. They create a deeper consumer experience by providing consumers with environmental, coexistence, and life values. These values are directly connected to the consequential values that consumers expect and thus serve as an important factor in determining their PAs.

We reversed the application of MEC theory to reflect the contributing characteristics of forest cultural products in the following order: contributing characteristics → values → PAs. This underscores that consumers consider the depth of value and experience provided by forest cultural products more important than their physical attributes when choosing forest cultural products. For example, the environmental value provided by forest cultural products influences consumers to choose activities such as appreciating natural scenery or exploring forests.

2.3. Selection of Indicators

To derive the subdimensions of the values, benefits, and activities of consumers regarding FC and to reveal the relationship among these three variables, indicators were identified as shown in

Table 1 based on literature and legal evidence.

PVs were selected based on the types and attributes of FC values, including the value of forests, FC, and cultural heritage (

Table 1). Values refer to the values that people pursue FC. Eleven corresponding indicators were identified, including V1 - public interest, V2 - economic, V3 - environmental, V4 - moral, V5 - historical, V6 - artistic, V7 - academic, V8 - life, V9 - coexistence, V10 - community, and V11 - emotional values.

Contributed benefits were selected by considering the contribution characteristics presented in laws and systems (

Table 1). Benefits refer to the positive functions that can be expected from FC. The following four indicators were selected: B1 - improvement of the quality of life among the public, B2 - revitalizing the local economy, B3 - relevance to real life, and B4 - accessibility of enjoyment by the public.

PAs were selected by considering the forest cultural attributes from 25 types of forest welfare activities in Korea, referencing the regulations (

Table 1). The attributes represent tangible and intangible products and services for enjoying FC. The following 19 indicators were selected: A1 - visiting a museum exhibition in the forest, A2 - attending a musical performance in the forest, A3 - participating in a literary event in the forest, A4 - participating in an artistic activity in the forest, A5 - participating in a forest-based handicraft activity, A6 - experiencing afforestation, A7 - experiencing forest product harvesting, A8 - observing and learning about plants and animals, A9 - participating in forest leisure activities, A10 - participating in valley leisure activities, A11 - participation in health promotion activities, A12 - forest exploration, A13 - exploration of natural scenic spots of forest cultural resources, A14 - appreciation of natural scenery, A15 - experiencing forest life, A16 - playing games related to forests (mountains, trees, and forests), A17 - reading books related to forests (mountains, trees, and forests), A18 - self-development and learning in forestry, and A19 - social service activities related to forests.

Table 1.

Selection of variables.

Table 1.

Selection of variables.

| Division |

Variables |

Variable names |

Previous studies |

| Values: values sought for forest culture |

Public interest value |

V1 |

[32]

[33]

[34]

[35]

[7]

[9]

Cultural Heritage Protection Act

World Heritage Convention

Cultural Heritage Conservation Principles

U.S. Forest Service |

| Economic value |

V2 |

| Environmental value |

V3 |

| Moral value |

V4 |

| Historical value |

V5 |

| Artistic value |

V6 |

| Academic value |

V7 |

| Life value |

V8 |

| Coexistential value |

V9 |

| Community value |

V10 |

| Emotional value |

V11 |

Benefits:

positive functions of forest culture |

Improvement of the quality of life among the public |

B1 |

Framework Act on Forestry, Forest Welfare Act, Forest Recreation Act, Framework Act on Culture

Purpose and definition and policies on leisure and life well-being |

| Revitalizing the local economy |

B2 |

| Relevance to real life |

B3 |

| Accessibility of enjoyment to the public |

B4 |

Activities:

products and services for enjoying the forest culture |

Visiting a museum exhibition in the forest |

A1 |

Out of 25 forest recreation activities, 19 activities related to forests’ recreational and leisure functions are designated as indicators. |

| Attending a musical performance in the forest |

A2 |

| Participating in a literary event in the forest |

A3 |

| Participating in an artistic activity in the forest |

A4 |

| Participating in a forest-based handicraft activity |

A5 |

| Experiencing afforestation |

A6 |

| Experiencing forest product harvesting |

A7 |

| Observing and learning about plants and animals |

A8 |

| Participating in forest leisure activities |

A9 |

| Participating in valley leisure activities |

A10 |

| Participation in health promotion activities |

A11 |

| Exploration of forests |

A12 |

| Exploration of natural scenic spots of forest cultural resources |

A13 |

| Appreciation of natural scenery |

A14 |

| Experiencing forest life |

A15 |

| Playing games related to forests (mountains, trees, and forests) |

A16 |

| Reading books related to forests (mountains, trees, and forests) |

A17 |

| Self-development and learning in forestry |

A18 |

| Social service activities related to forests |

A19 |

2.4. Data Collection and Sampling

2.4.1. Data Collection and Sampling

Based on the 2023 National Forest Culture Awareness, Attitude, and Enjoyment Survey, a representative population of FC product consumers was established. The sample was chosen to reflect the demographic diversity of FC consumers in Korea. Individuals aged 15–69 were selected to capture a broad range of consumer behaviors and attitudes, ensuring that the results are representative of the general population. The entire survey was conducted online and commissioned by a professional survey company. The following analyses were conducted to identify the subdimensions of the contributing characteristics, PV, and PAs of the consumers of forest cultural products. Exploratory factor and reliability analyses were conducted using SPSS 2.0. (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). To verify the validity of the factors, confirmatory factor analysis and a structural equation model were applied using AMOS 29.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Confirmatory factor analysis of PVs was conducted using a sample size of 1,639 out of 1,700 after removing outliers or missing values through data preprocessing. We removed missing values and items in this analysis that gave the same score for all items and excluded two items with low factor loadings (“observing and learning about plants and animals” and “attending performances and music concerts in the forest”), resulting in a sample size of 1,084 out of 1,700. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to analyze the relationship between the subdimensions of each variable and how contributing characteristics influence PAs via PVs.

2.4.2. Analytical Methods

To analyze the relationship between the variables, we conducted a survey focusing on quantitative data. Confirmatory factor analysis and exploratory factor analysis were conducted to analyze the validity of the variables derived from previous studies. SEM is a complex statistical technique that allows for the analysis of relationships between multiple variables. In this study, latent variables—values, benefits, and activities—were used for the analysis. These latent variables were estimated through their respective measured variables, where values reflect individual beliefs or goals, benefits denote the positive outcomes gained from participation, and activities represent the specific behaviors people prefer to engage in.

Through SEM, we examined how contributing characteristics (e.g., demographic factors) directly influence PVs (e.g., environmental conservation and health improvement) and further tested the mediation effects of these values on PAs (e.g., recreational activities in forests). Mediation effects are the pathways through which characteristics affect values, which then influence activities. This analytical approach enabled us to analyze both direct and indirect interactions between the variables.

SEM was employed to examine the relationships among the subdimensions of each variable. The structural equation model analyzed how contributing characteristics influence PAs by mediating PV. All indicators in this analysis met the criteria, with the goodness of fit index (GFI = 0.902), adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI = 0.874), and comparative fit index (CFI = 0.882) approaching or exceeding 0.9. Additionally, the RMSEA value was 0.066, which falls within the acceptable range.; therefore, the measurement model was considered adequate. In this way, we analyzed the contributing characteristics, PVs, and PAs of forest cultural product consumers and derived policy implications for the sustainable management and development of FC based on these findings.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

Frequency analysis was conducted to determine the demographic characteristics of the participants. The participants comprised 50.9% males and 49.1% females. The age distribution was as follows: 50s (21.8%), 40s (20.5%), 60 or older (18.9%), 20s (18.7%), 30s (16.7%), and 10s (3.4%). The educational level was as follows: college graduate (60.9%), high school graduate (22.1%), and postgraduate degree (6.8%). The occupations of forest cultural product consumers included office workers (29.5%), housewives (15.2%), technical workers (8.5%), and others (7.8%). The regions of residence were Gyeonggi (26.8%), Seoul (18.9%), Busan (6.4%), and Gyeongnam (6.2%;

Table 2).

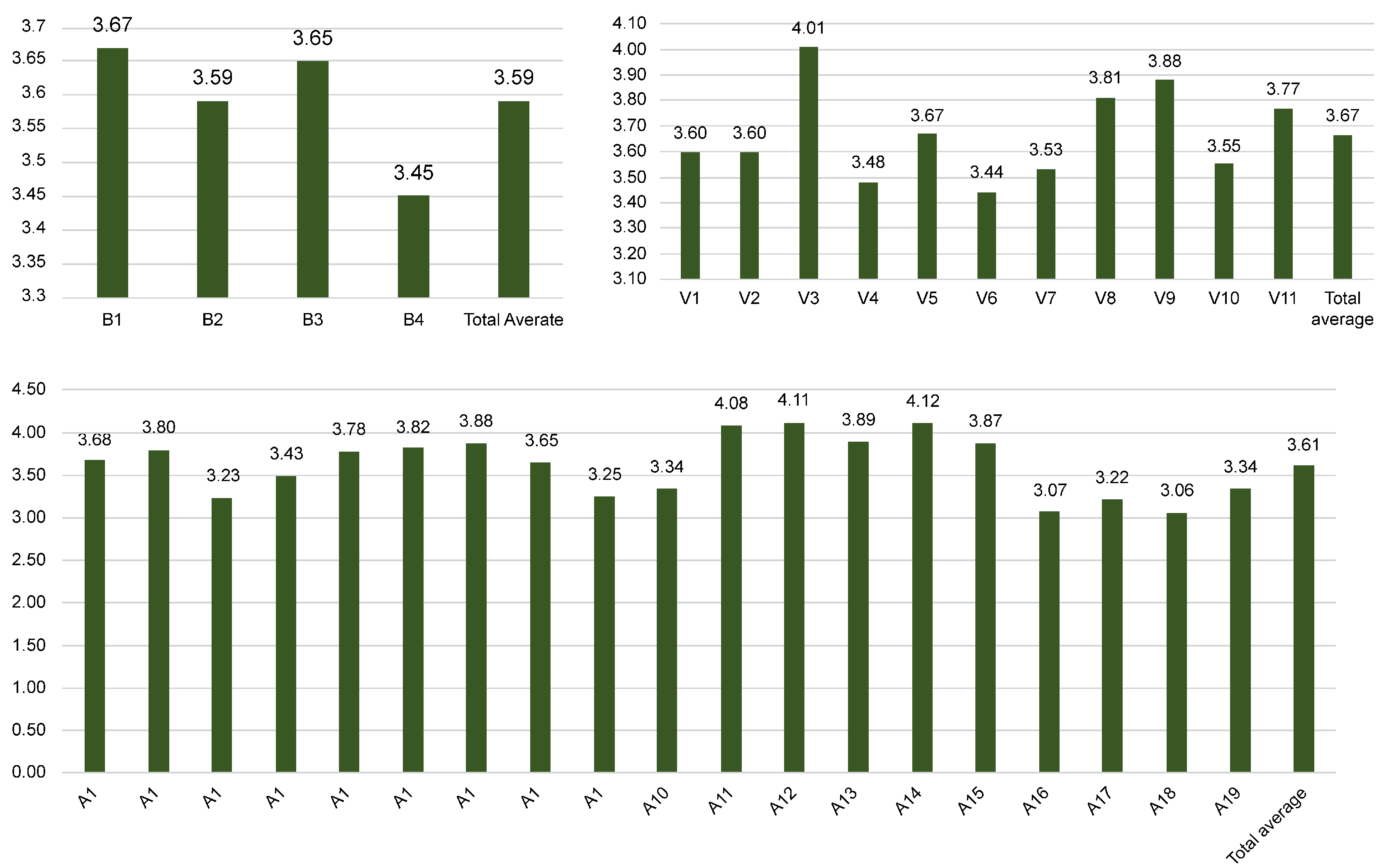

3.2. Comparative Analysis of Means of PV, PAs, and Contributing Characteristics

Based on

Table 3 and

Figure 2, the environmental value (M = 4.01) and appreciation of natural scenery (M = 4.12) emerged as the highest-ranking factors among PVs and product attributes, respectively, indicating a strong preference for ecological and scenic elements of FC. In contrast, artistic value (M = 3.44) and self-development activities (M = 3.06) had the lowest means, indicating less importance placed on cultural and personal growth within forest experiences.

When considering values above the overall mean of 3.67, coexistential value (M = 3.88) and life value (M = 3.81) stood out, showing that participants placed high value on the interconnectedness of life and coexistence within forest environments. Similarly, product attributes such as exploration of forests (M = 4.11) and participation in health promotion activities (M = 4.08) were rated above the average of 3.61, suggesting that participants were particularly drawn to engaging with nature for both exploration and health benefits.

In terms of contributing benefits, the overall mean was 3.59. The improvement of the quality of life among the public (B1, M = 3.67) had the highest score, followed by relevance to real life (B3, M = 3.65) and revitalizing the local economy (B2, M = 3.59). However, accessibility of enjoyment to the public (B4, M = 3.45) was rated the lowest, suggesting that while forests play a significant role in improving public quality of life, there is a relatively negative perception regarding the accessibility of cultural enjoyment within forest settings.

Overall, the analysis indicated a strong preference for the ecological and health-promoting aspects of FC, with lower emphasis on artistic and self-development activities, as well as concerns about accessibility to cultural experiences in forests.

3.3. Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analyses of PVs

A factor analysis of the 11 items concerning the PVs of FC revealed three factors—symbolic, social and consumption value—with an explanatory power of 59.71% of the total variance. All items fulfilled the factor loadings; therefore, no items were removed. The results of the confirmatory factor analysis were df = 41,

p = 0.000, GFI = 0.974, AGFI = 0.958, RMR = 0.024, NFI = 0.956, CFI = 0.967, and RMSEA = 0.05, indicating that all factors met the standards, and thus, the measurement model was considered valid. Since the exogenous variables of the three factors were clearly distinguishable from each other, conceptual validity was verified. The Cronbach’s alpha values were all above 0.89, indicating that each factor had internal consistency, reliability, and focus validity across all items. The results of the exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses are presented in

Table 3.

Factor 1, labeled as Symbolic Value, included community, moral, and historical values, with a total explained variance of 41.95%. Factor 2, labeled as Social Value, included environmental, coexistential, and public interest values, explaining 10.69% of the variance. Factor 3, labeled as Consumption Value, included economic, academic, and artistic values, explained 7.07% of the variance.

Table 3.

Factor analysis of pursued values.

Table 3.

Factor analysis of pursued values.

| Factor |

Items |

Factor loading |

Standard loading |

Standard error |

T value |

| Symbolic Value |

V4-Moral value |

1 |

0.612 |

|

|

| V5-Historical value |

0.955 |

0.602 |

0.063 |

15.082*** |

| V10-Community value |

0.999 |

0.632 |

0.064 |

15.595*** |

| Social Value |

V3-Environmental value |

1 |

0.692 |

|

|

| V9-Coexistential value |

1.007 |

0.734 |

0.048 |

20.825*** |

| V1-Public interest value |

0.943 |

0.675 |

0.049 |

19.405*** |

| V8-Life value |

0.973 |

0.7 |

0.049 |

20.024*** |

| V11-Emotional value |

0.917 |

0.689 |

0.046 |

19.739*** |

| Consumption Value |

V2-Economic value |

1 |

0.554 |

|

|

| V6-Artistic value |

1.052 |

0.621 |

0.073 |

14.387*** |

| V7-Academic value |

1.062 |

0.609 |

0.075 |

14.227*** |

3.4. Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analyses of PAs

To investigate the subdimensions of the PAs of FC, an exploratory factor analysis was performed on the 19 PA items, resulting in the extraction of three factors with an explanatory power of 56.56% of the total variance.

All factors were initially retained without removing any items. However, during the confirmatory factor analysis, seven items (A5, A6, A7, A8, A15, A17, A19) from the PAs category were removed due to low factor loadings, which fell below the threshold of 0.45

The analysis yielded the following results: df = 32,

p =.000, GFI = 0.948, AGFI = 0.911, RMR = 0.068, NFI = 0.928, CFI = 0.936, and RMSEA = 0.087. While RMR failed to meet the standard criteria, the other indicators did, including NFI = 0.928 and CFI = 0.936, indicating that the measurement model was valid. Conceptual validity was verified because the exogenous variables of the three factors were clearly distinguishable from each other, and Cronbach’s alpha values were all above 0.91, indicating that each factor demonstrated internal consistency, reliability, and focused validity among all items. The results of exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses are shown in

Table 4.

Factor 1, labeled as Tourism-Exploration Activity, included "exploration of forests," "participation in health promotion activities," "appreciation of natural scenery," and "exploration of natural scenic spots," explained 37.31% of the total variance. Factor 2, labeled as Cultural-Artistic Activity, included "participating in an artistic activity," "attending a musical performance," "participating in a literary event," and "visiting a museum exhibition," explained 11.99% of the variance. Factor 3, labeled as Living-Leisure Activity, included "participating in forest leisure activities," "participating in valley leisure activities," "playing games related to forests," and "self-development and learning in forestry," explained 7.27% of the variance.

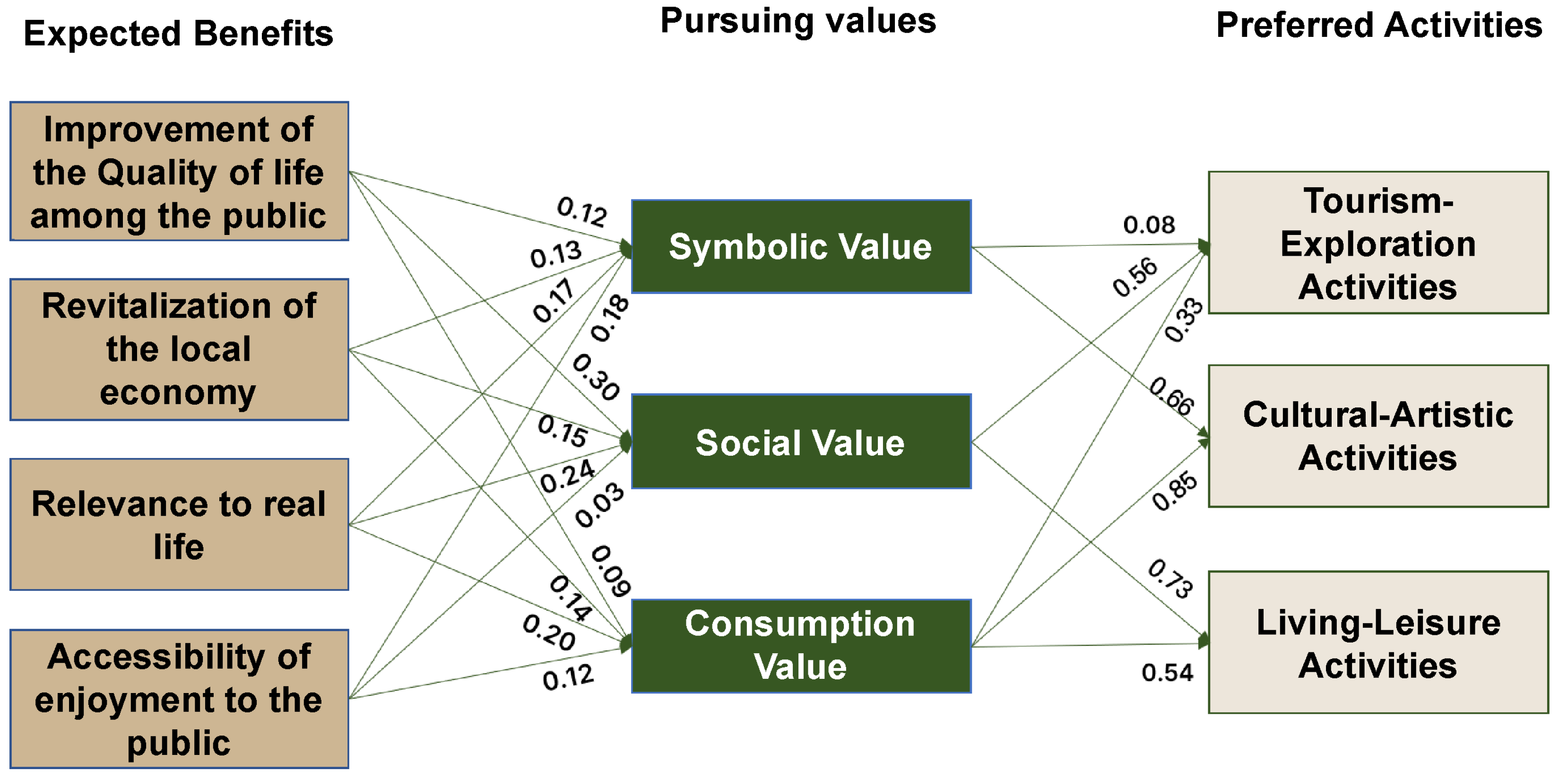

3.5. SEM of PVs, Contributing Characteristics, and PAs

SEM analysis revealed significant pathways between the subdimensions of contributing benefits, PVs, and product attributes of forest cultural products (

Figure 3). Specifically, contributing benefits significantly influenced PVs, which in turn affected product attributes. The analysis indicated that the mediating factors of Symbolic Value and Consumption Value influenced all activities, while Social Value influenced only Tourism-Exploration activities. The subdimensions B1-improvement of the quality of life among the public, B2-revitalizing the local economy, and B3-relevance to real life had the greatest effect on Tourism-Exploration activities through the mediation of Social Value, while enjoyment by the public had the largest impact on Living-Leisure activities through the mediation of Symbolic Value. Additionally, the SEM analysis yielded acceptable model fit indices: GFI = 0.902, AGFI = 0.874, CFI = 0.882, and RMSEA = 0.066. These results suggest that the model well fit the data.

4. Discussion

4.1. Classification Characteristics of the Values and Attributes of FC

Factor analysis identified three key factors for both PVs and PAs in FC. The first factor, Symbolic Value, reflects temporal characteristics such as history, morality, and community values, indicating that FC functions as a symbolic good. The second factor, Social Value, highlights collective values based on ecological characteristics, showing that FC serves as a social good. The third factor, Consumption Value, includes academic, artistic, and emotional values, aligning with Bourdieu’s [

36]concept of high-end cultural capital and characterizing FC as a consumer good. The product attributes of FC were divided into three categories. The first, tourism and exploration activities, involves appreciating nature’s beauty and understanding ecosystem diversity. The second, cultural-artistic activities, integrates the enjoyment of both nature and cultural elements of FC. The third, living-leisure activities, includes recreational and sports activities that contribute to community development. Among these, Consumption Value closely ties to Bourdieu’s[

36] theory of cultural capital, where artistic and academic activities are key components of social capital formation. FC, through events like artistic performances or academic activities, operates as a form of high cultural capital. These activities demonstrate that FC is not merely a natural resource but also a cultural asset. Eagleton [

37] further emphasized the importance of cultural capital, arguing that participation in cultural activities can enhance an individual’s social status. In the context of SDG 12, which focuses on responsible consumption and production, FC plays a crucial role in promoting sustainable consumption patterns. Specifically, SDG 12 encourages practices that reduce environmental impact and promote the efficient use of resources. FC, through its emphasis on activities such as tourism, cultural experiences, and community-based leisure, aligns with these principles by offering ways to engage with natural resources without depleting them. The factor of tourism and exploration activities highlights the value of nature-based tourism, which directly supports SDG 12.b, focusing on sustainable tourism. These activities, such as exploring natural scenic spots and participating in health-promoting forest activities, are designed to enhance environmental appreciation while ensuring the responsible use of forest resources. By promoting tourism that fosters a deeper connection to nature, FC contributes to both environmental protection and the local economy, fulfilling SDG 12’s objectives of sustainable consumption and production. Similarly, the cultural-artistic activities related to FC encourage the sustainable consumption of cultural resources. These activities—such as art performances and educational events in forests—are not only culturally enriching but also help to reinforce community empowerment by encouraging locals to engage with and take pride in their forested environments. This aligns with SDG 12’s focus on the efficient use of resources, ensuring that cultural capital is built without harming ecological systems. Finally, the factor of living-leisure activities underscores the importance of fostering recreational activities that are in harmony with environmental sustainability. Activities like forest-based sports or community-building efforts are directly connected to responsible consumption of the environment. By promoting forest leisure in a way that respects ecological balance, these activities help reduce the negative environmental impacts associated with overconsumption and contribute to SDG 12’s overarching goals of creating sustainable consumption patterns.

In summary, FC, by encouraging activities that balance ecological preservation with cultural and recreational engagement, offers a clear example of how SDG 12 can be implemented in practice. Through sustainable tourism, cultural enrichment, and responsible leisure activities, FC promotes the responsible consumption of natural and cultural resources.

4.2. Characteristics of FCin MEC Theory

Applying MEC theory to FC products, benefits are first recognized, then values are formed, and finally, attributes are selected. The laddering method in the traditional MEC model is a process in which consumers first recognize attributes when choosing a product, experience the benefits provided by those attributes, and ultimately reach a value[

38]. Furthermore, cultural and artistic products are differentiated from the traditional model in that consumers care more about the values and experiences that the attributes symbolize than the physical attributes. Essentially, consumers are drawn to deeper experiences and values, such as environmental, emotional, and social benefits, rather than the physical characteristics themselves [

39]. The benefits of forest cultural products, unlike general consumer goods, include not only individual characteristics but also shared characteristics. Forest consumer experiences reflecting collective interests, such as community features, ecological sustainability, and environmental conservation, beyond the individual level [

40] seem to have changed. We believe this logic is because the essence of forest cultural products is closely connected to value consumption, as argued by Sheth et al. [

41]. It also implies that forest cultural products are not merely consumer goods but are positioned as value-based products that offer a moral, emotional, and environmental experience. This is consistent with the service-dominant logic argued by Vargo and Lusch [

42], which states the importance of the value and experience provided by the product rather than the product itself. In conclusion, the direction of benefits→value→activities in forest cultural products reflects the values and cultural understanding of consumers, which is different from that of general consumer goods. Consumers would rather prioritize the emotional, social, and ethical benefits of the experience than the physical experience provided by forests. This demonstrates that forest cultural products are not mere consumer goods but products that should be approached from the perspective of value consumption. Furthermore, it suggests that these products function as an important medium to realize the value that consumers seek.

4.3. Proposal and Limitations

Our analysis suggests that understanding forest tourism demand and developing strategies to expand the market, while ensuring sustainable environmental development, can potentially revitalize the local economy ([

15,

18,

43]. To achieve SDG 12.b and strengthen community empowerment, it is essential to implement schemes and certifications such as Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) and Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC), which will encourage the active involvement of governments, corporations, and consumers.

Limitations of this study include the following: first, the categorization of values and PAs was limited in terms of comparative analysis of the characteristics of each type and did not identify differences between groups; second, the focus on analyzing consumer-oriented value perceptions did not fully reflect the specific economic and environmental contributions generated at each stage of the value chain. In future studies, we plan to systematically analyze the value creation and distribution process of FC by combining a value-chain model with a comparative analysis of specific data on the values and PAs of different generations and propose a sustainable consumption of FC.

5. Conclusions

Our findings are distinct from those of previous studies in that earlier MEC studies primarily focused on the general relationship between consumers’ personal values and product attributes, while this study extends the application of MEC theory by specifically analyzing how the multidimensional values of FC impact consumer behavior. Forest cultural products offer consumers a wide range of social and environmental values, which are crucial for informing both policy development and productization strategies.

We aimed to propose policies and strategies from a value consumption perspective, focusing on the expected benefits of FC. By doing so, we seek to enhance the sustainability of FC and maximize its social contributions. Our results suggest that to ensure the universal distribution of FC benefits, it is necessary to provide policy support for tourism and exploration programs within FC activities. Furthermore, expanding the market for cultural products requires active support for cultural and artistic activities, emphasizing their consumption value. This approach offers fundamental data for building an integrated marketing strategy that reflects the multidimensional values of FC and provides key insights into understanding the connections between consumers' deep values and emotions. Additionally, we found that the contributing characteristics of FC are closely tied to the values that consumers pursue, which, in turn, guide their PAs. Ultimately, this study highlights that FC is a valuable cultural resource that offers multidimensional benefits. Therefore, it is vital to formulate policies and productization strategies that reflect these values. Going forward, adopting an integrated approach that encompasses the diverse values of FC will be crucial. This will not only enhance the sustainability of FC but also maximize its social impact.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C. and S.K.; methodology, J.C.; software, N.C.; validation, J.C. and S.K.; formal analysis, J.C. and N.C.; investigation, S.K.; data curation, J.C., T.K., and N.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C. and N.C; writing—review and editing, J.C.; visualization, J.C. and N.C.; supervision, J.C. and S.K.; project administration, S.K.; funding acquisition, S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kanowski, P.; Williams, K. The Reality of Imagination: Integrating the Material and Cultural Values of Old Forests. For. Ecol. Manag 2009, 258, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoletti, M.; Piras, F.; Venturi, M.; Santoro, A. Cultural values and forest dynamics: The Italian forests in the last 150 years. Forest Ecology and Management 2022, 503, 119655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, T.; Nguyen, T.; Hương, D.; Ly, T. Forest - Related Culture and Contribution to Sustainable Development in the Northern Mountain Region in Vietnam. For. Soc. 2021, 5, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoletti, M.; Santoro, A. Cultural values and sustainable forest management: The case of Europe. Journal of Forest Research 2015, 20, 438–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim. Culture of Our Forest. Gwanglim Gong-sa. 1993.

- Jeon. Suggestions for Promoting Cultural Forestry. Society for Forests&Culture. 2003, 12, 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- Chae. Change of Pluralistic Value in Mt. Gwanak as Suburban Mountain. Interdisciplinary Doctoral Program in Landscape Architecture Major Graduate School Seoul National Uiversity. 2016, 1–208.

- Forest and Culture Association. Forest and Culture. Society for Forests&Culture, 2018.

- Kim, T.; Kim, S. Typifying cultural values through literature research on ‘Forest’ in Korea. Human contents 2023, 70, 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, T. Review of Forest Culture Research in Japan: Toward a New Paradigm of Forest Culture. In; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, 1998; ISBN 9780792352808. [Google Scholar]

- Ritter, E.; Dauksta, D. Human–Forest Relationships: Ancient Values in Modern Perspectives. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2012, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoletti, M.; Santoro, A. Cultural Values and Sustainable Forest Management: The Case of Europe. J. For. Res. 2015, 20, 438–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoletti, M.; Piras, F.; Venturi, M.; Santoro, A. Cultural values and forest dynamics: The Italian forests in the last 150 years. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 503, 119655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara, S.; Julián, I.P. Sustainable Consumption and Production: A Crucial Goal for Sustainable Development—Reflections on the Spanish SDG Implementation Report. J. Sustain. Res. 2019, 1, e190019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasper, D.; Shah, A.; Tankha, S. The Framing of Sustainable Consumption and Production in SDG 12. Glob. Policy 2019, 10, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, N.K.; Mishra, I. Responsible Consumption and Production: A Roadmap to Sustainable Development. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, M.; Alfredsson, E.; Cohen, M.; Lorek, S.; Schroeder, P. Transforming Systems of Consumption and Production for Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals: Moving beyond Efficiency. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 1533–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sgroi, F. Forest Resources and Sustainable Tourism, a Combination for the Resilience of the Landscape and Development of Mountain Areas. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 736, 139539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.K.; Kumar, A.; Singh, A.; Singhal, P. Evidence That Cultural Food Practices of Adi Women in Arunachal Pradesh, India, Improve Social-Ecological Resilience: Insights for Sustainable Development Goals. Ecol. Process. 2020, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Government Legislation of South Korea. Available online: https://moleg.go.kr.

- National Institute of Forest Science. Trends in Cultural Contents for the Use of Forest Culture. 2024, 116, 1–177.

- Kim & Chae. Forest Culture Awareness and Cultural Content Trends Changes and Implications. National Institute of Forest Science 2024, 184, 1–19.

- Gutman, J. A Means-End Chain Model Based on Consumer Categorization Processes. J. Mark. 1982, 46, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson & Reynolds. Understanding Consumer Decision Marketing:The Means-End Approach to Marketing and Advertising Stategy. Lawrence Elbaum Associates, Publishers, Mahwah 2001.

- Shin E., J.; Lee, Y. S The Effect of Consumers’ Value Perception of Cultural and Artistic Products on Benefits Seeked and Product Attributes. Asia Market. J. 2012, 14, 177–207. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, I.S.; Cho, M.H. Analysis of The Relationships among Jeju Olle Tourist Attractions, Benefits for Walking Tourists, and Perceived Value: Application of Means-End Chain Theory. J. Tourism Res. 2011, 23, 127–154. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, I.H.; Kim, Y.S.; Baek, T.H.; Choi, Y.K. An Exploratory Study on the Perception and Consumption Behavior of Korean and American Consumers Toward “Eco-Friendly Products”: Application of Means-End Chain and Topic Modeling. J. Advert. Res. 2024, 35, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgardt, E. Means-End Chain Theory: A Critical Review of Literature. 2020, 64, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillat, F.A.; d'Astous, A.; Grégoire, E.M. Leveraging Social Responsibility: The Influence of Corporate Ability and Cause Proximity on Attitudes Toward the Sponsor. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 329–336. [Google Scholar]

- Mooij, M.; Hofstede, G. Cross-Cultural Consumer Behavior: A Review of Research Findings. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2011, 23, 181–192. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, A.J.; Thyne, M.A. Understanding Tourist Behavior Using Means-End Chain Theory. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.; Thyne, M.A. Understanding the Use of Laddering as a Research Technique for a Means-End Chain Analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 104, 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, Y.W.; Tak, *!!! REPLACE !!!*. Cultural Forestry:Its Scope and the Scheme for Dissemination. Science of Forest 1997, 5–28. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon. Developmenr of Forest Culture. Society for Forests&Culture. 1996, 5, 12–26. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon. Why Should We Graft Culture on Forests? Society for Forests&Culture. 1997, 6, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lee & Kim. Urban Residents’ Cultural Recognition of Forest Resources in Korea. Journal of Forest Recreation 2000, 4, 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. The Forms of Capital. In The sociology of economic life; Routledge, 2018; pp. 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Eagleton, T. After Theory. New Left Review 2003, 2, 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Grunert, K.G.; Grunert, S.C. Measuring Subjective Meaning Structures by the Laddering Method: Theoretical Considerations and Methodological Problems. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1995, 12, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer Perceptions of Price, Quality, and Value: A Means-End Model and Synthesis of Evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S. : Kim, J.; Baek, S. Environmental Values and Collective Benefits in Forest-Related Tourism: A Multi-Value Perspective. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 46, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Sheth, J.N.; Newman, B.I.; Gross, B.L. Why We Buy What We Buy: A Theory of Consumption Values. J. Bus. Res. 1991, 22, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Evolving to a New Dominant Logic for Marketing. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Matsumoto, K. The Effect of Forest Certification on Conservation and Sustainable Forest Management. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 363, 132374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).