1. Introduction

CLBP is one of the most globally prevalent musculoskeletal conditions that is defined as low back pain that persists for more than three months and beyond a recovery time that is typically expected [

1,

2]. The prevalence of CLBP has risen steadily since the 1990s and it is predicted to continue an upward trajectory over the coming decades, having a significant impact on not only the individual but also society [

3]. Current management strategies for CLBP recommend a combination of physical and psychological approaches; although these strategies so far have been associated with, at best, moderate effectiveness from largely low-quality evidence [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

For most individuals with CLBP, it is not possible to identify a specific structural cause for their symptoms, which subsequently has a significant physical and psychological impact on their lives [

10]. Existing qualitative literature has shown that people with CLBP frequently feel uncertain about issues such as their diagnosis and the cause of their symptoms, their ability to manage fluctuating symptoms that are prone to reoccurrence and the overall impact that the condition will have on the maintenance of their self-identity, challenging their perception and understanding of the future [

3,

10,

11,

12]. Further research exploring common challenges that are caused by uncertainty is essential, in order to assist Health Care Professionals (HCPs) to navigate these issues during CLBP consultations and provide a tailored management approach. Uncertainty can subsequently influence emotions and emotional regulation which is essential for their health and well-being [

13]. A lot of controversy still exists about what exactly defines an emotion, but common agreements are that it is a time-limited physiological state, which includes the individual's personal experience and how the emotion is appraised and subsequently expressed through their behaviour and peripheral physiological responses [

13,

14]. Equally, emotional regulation has been a relatively new focus within chronic pain literature [

2]. It refers to an individual’s ability to compare and adapt their current emotional state with one that is desired, which includes how it is expressed through the utilisation of ERS [

15]. Therefore, uncertainty, which is based on the principle of not knowing, is strongly associated with CLBP due to the complexity of the condition and can severely challenge hope [

16]. Therefore, if HCPs can successfully navigate these concepts during CLBP consultations, the outcome can potentially be therapeutic, but if they are managed poorly, it can be central to the destruction of hope resulting in major psychological consequences such as severe depression or even suicide [

17].

Hope can be considered as an essential emotion or feeling for all human beings, based on a meaningful and positive outlook [

18]. Other components found in models of hope include an individual’s ability to meet the demands faced and the ability to achieve goals [

19]. Hope is deemed to play an essential therapeutic role within healthcare because goals enable HCPs to understand what is most important to the individual, but they also provide a vital part of their coping mechanism by giving them a focus [

17]. The definition of hope by Snyder et al [

20] (p. 287) is widely accepted, which states that hope is firstly based on the degree of motivation an individual has to achieve a goal (also known as ‘goal-directed energy’) and secondly, it is also influenced by the individual’s ability to plan how they will achieve their goal. However, hope can change depending on factors such as time and context [

11]. Moreover, meaningful hopes and positive emotions of people with CLBP are severely influenced by what is deemed as possible or uncertain [

19]. For this reason, Snyder et al [

21] classified hope into two types; the first is ‘trait-hope’ whereby the individual effectively copes and uses efficient pathways to achieve their goals. Whereas ‘state-hope’, refers to the individual’s ability to cope and achieve goals, but it is very much dependent on the time and situation. Therefore, individuals with high levels of trait-hope are motivated and can effectively plan how they will achieve their goal via the most efficient pathway, regardless of the context [

22]. Additionally, they would view any barriers to achieving their goals as challenges that they can overcome by altering the originally planned pathway [

23].

Uncertainty in illness was first defined by Mishel [

24] (p. 225) as: “

the inability to determine the meaning of illness-related events”. It is a cognitive state which occurs when an individual encounters ‘

an unknown’, referred to as ‘

a perceived absence of information’ [

14] (p. 71). This typically means that the individual is unable to process information to predict outcomes, which in turn reduces their control, often due to inconsistent symptoms, unfamiliar events and lastly, when there is a mismatch between what is expected and what is experienced [

25]. The presence of uncertainty has a central influence on the ability to hope and access meaningful hopes and is associated with the expression of emotions and emotional regulation [

19]. Even though uncertainty is associated with nearly all healthcare encounters, it is a growing problem for HCPs and its service users due to rapidly advancing clinical research resulting in new technologies and procedures, an increase in public awareness of the limitations of medial knowledge through media coverage and lastly an overall heightened anxiety over health and risk of illness amid society [

26].

To date, research on hope has been undertaken predominantly within non-chronic pain populations, such as cancer, but also aging and other chronic illnesses such as heart disease and multiple sclerosis, widely establishing that higher levels of hope correlate with a higher pain tolerance, better physical health and psychological well-being [

27,

28]. Very little research on hope exists within chronic pain populations, or more specifically chronic musculoskeletal conditions, and the same literature gaps apply for uncertainty [

3,

28]. Moreover, as yet, the link between hope, uncertainty and emotional regulation has also not been well considered [

19]. The ability to address this gap would require research that can generate a substantive theory, one way of achieving this within CLBP populations could be through a theory generating review. Social constructivist meta-ethnography is a recent methodology with a purpose of developing a substantive theory by following iterative phases of theory development [

29]. To the best of the authors knowledge, no past theory generating review have been undertaken to develop an understanding of how these concepts could be managed by developing a substantive theory and research is also needed which can provide a worked example of a social constructivist meta-ethnography. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to explore the concepts of hope, uncertainty and how they both influence emotion regulation, specifically within a population of people with CLBP and to generate a substantive theory using social constructivist meta-ethnography to demonstrate how it is influenced.

3. Results

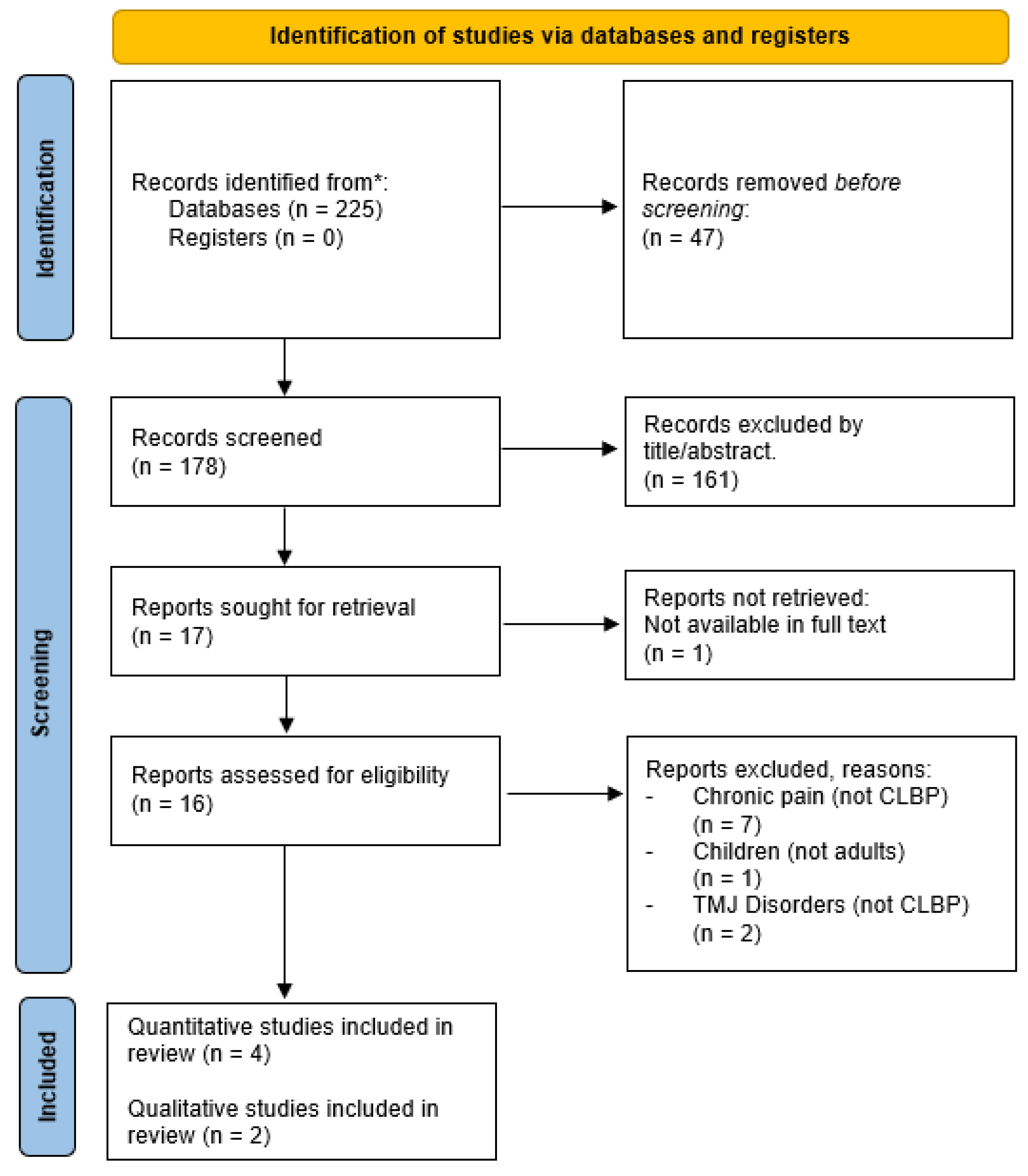

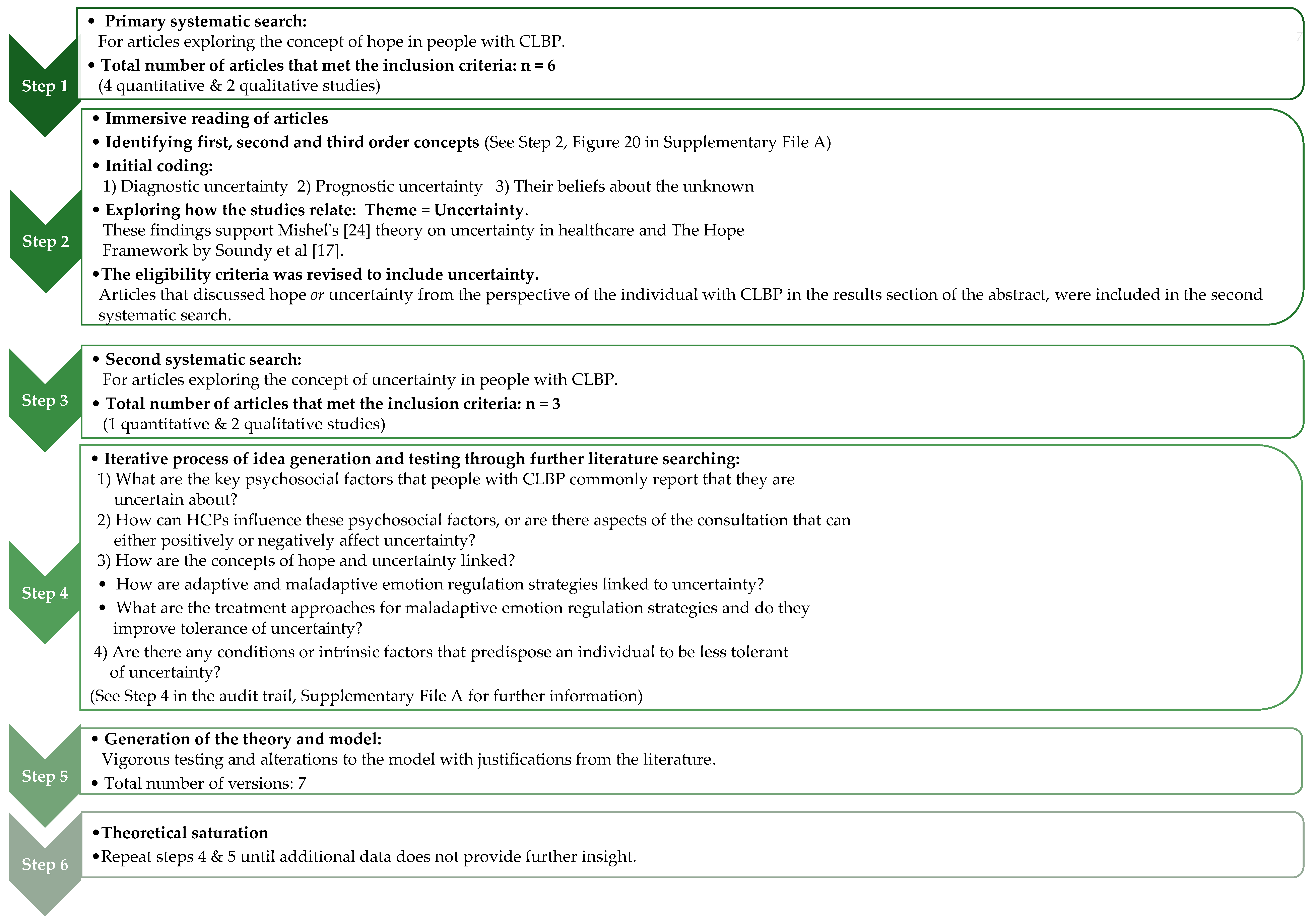

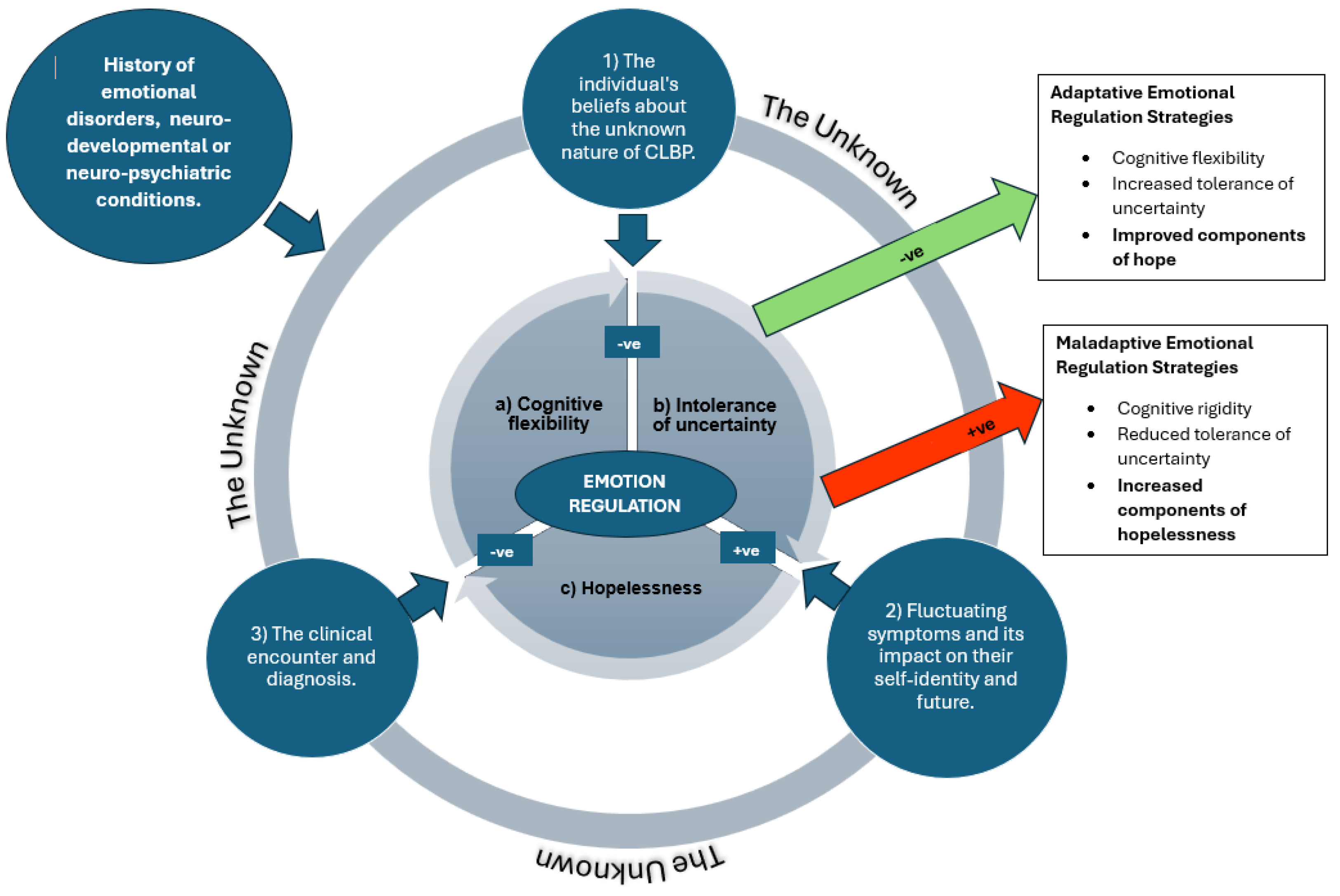

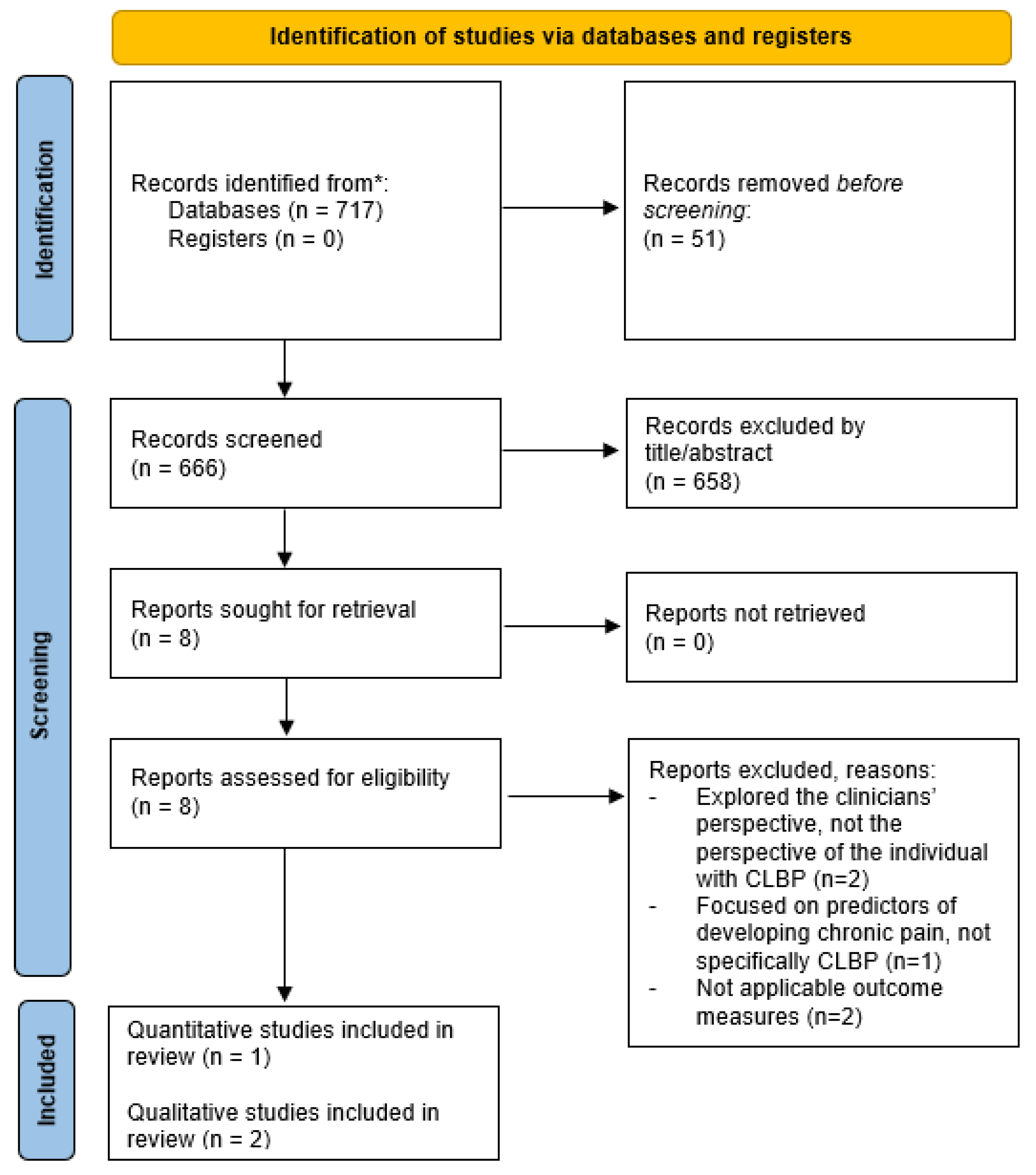

The aim of this study was to gain a valuable insight into this unique area by exploring the concepts of hope, uncertainty and how they both affect emotion regulation in people with CLBP. A substantive theory was generated which demonstrates how these concepts are linked and influenced (see

Figure 4), to provide guidance for HCPs and ultimately improve health outcomes for people with CLBP.

The heart of this theoretical model focuses on how an individual with CLBP regulates their emotions. The inner core of the model is initially associated with three central and related factors: (a) cognitive flexibility, (b) intolerance of uncertainty and (c) hopelessness. ERS are divided into two types; the first is ‘adaptive’ ERS, whereby individuals can regulate their emotions effectively using strategies such as acceptance, reappraisal and problem solving, although there is generally less research exploring this approach. Whereas in contrast, more extensive research has been undertaken on ‘maladaptive’ ERS which involve behaviours such as suppression, rumination, avoidance or reassurance seeking which are typically ineffective and trigger psychopathology [

39]. It is widely established that individuals who have a history of emotional disorders such as anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, obsessive compulsive disorder, agoraphobia and perceived stress, but also some neurodevelopmental conditions such as autism, have difficulty regulating their emotions and tend to utilise maladaptive ERS [

14,

36,

37,

39]. However, in comparison to the general population, individuals who have chronic pain are three times more likely to be diagnosed with anxiety and depression [

15]. Therefore, an emotional disorder could also arise as a result of living with chronic pain, as opposed to them having a pre-existing condition which makes them more susceptible to employing inadequate ERS. Either way, people with chronic pain have a difficulty with emotional regulation due to the association with negative emotions, causing a biased perception that the outcome of an uncertain situation will be negative [

2]. There are four variables that contribute to the emotion dysregulation model (ERM): heightened intensity of emotions, poor understanding of emotions, negative response to emotions and the utilisation of maladaptive ERS [

37]. Overall, how an individual regulates their emotions will affect how they deal with uncertainty. A meta-analysis of 91 articles explored the strength of the association between IU and ERS, demonstrating that there is a moderate positive correlation between maladaptive ERS and IU and a moderate negative correlation between adaptive ERS and IU [

39]. Thus, individuals who are IU tend to utilise maladaptive ERS increasing psychological distress, and vice versa for adaptive ERS. These relationships are represented as feeding out of the inner core of the model. Another important finding from the study by Sahib et al [

39] was that the maladaptive ERS with the largest effect size was cognitive avoidance which involves individuals diverging their negative thoughts about situations, whereas mindfulness was the most effective adaptive ERS providing superficial support for treatment interventions such as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT). However, it is established that this is not always an effective treatment intervention for this population raising questions about other important influential factors.

Prior research has established that a predisposing factor for depression is hopelessness [

18]. Hopelessness has three components: firstly,

‘dismal expectations’ and a belief that future outcomes will be negative, secondly

‘blocked goal-directed processing’ and the perception that ones ability to achieve a goal is consistently thwarted, and lastly

‘helplessness’, feeling unable to change ones situation or influence outcomes [

40]. Together, these components are crucial in understanding the dynamics of hopelessness and its impact on individuals mental health and well-being [

19]. People who have emotional disorders are dependent on cognitive skills, such as cognitive flexibility, which involves an individual being able to shift their attention and thoughts between different stimuli simultaneously, to view situations and possible outcomes from different perspectives enabling them to cope with internal and external stressors [

41]. This maybe the crucial factor for allowing people with CLBP to re-appraise and shift from maladaptive to adaptive ERS [

18]. A study by Demirtas and Yildiz [

41] was the first to explore how hopelessness, intolerance of uncertainty, cognitive flexibility and perceived stress are interlinked through mediation analysis. Convenience sampling was used to recruit 302 students at a University in Turkey. The results showed that there is a negative correlation between hopelessness and cognitive flexibility in keeping with previous research, which means these individuals are less resistant to stressful situations and are unable to think of alternative solutions or pathways to achieve their goals, also known as cognitive rigidity. Additionally, hopelessness is positively correlated with IU and perceived stress, meaning they perceive uncertain situations to be stressful and threatening. Lastly, cognitive flexibility is negatively correlated with IU and perceived stress which often leads to negative mood states as they are unable to deal with or reduce uncertainty and stress. All correlations were statistically significant and are outlined within the inner core of the model providing evidence for relationships between these concepts, but due to the cross-sectional methodology the underlying cause cannot be established. Expanding on this research, Ouellet et al [

37] were the first to explore the possibility of merging the individually well-established IUM and the ERM, by examining the relationship between the IUM and tendency to worry, using limited access to ERS as the mediator between the two. They sent a series of self-report questionnaires to 204 non-clinical participants and concluded IU contributes to worry through being strongly associated with two components of the ERM, negative emotional orientation

and negative problem orientation. Therefore, in the face of uncertainty, individuals with low IU may have negative emotions, but they also doubt that they are able to change their emotional state becoming overwhelmed and exploiting maladaptive ERS, such as avoidance. As a result, this has an unfavourable impact on problem solving and their perception of their ability to achieve their goal. These results contradict the component of ‘positive beliefs about worry’ within the IUM because it suggests people find the mechanism of worrying useful to prepare for negative scenarios, but this study has demonstrated the opposite. As a result, the study proposes it should instead be referred to as ‘mistaken beliefs about worry’ and highlights an important area for future research. This also coincides with one of the three common psychosocial factors (‘their beliefs about the unknown’) that people with CLBP commonly report that they feel uncertain about when living this condition which is represented in the central outer rim of the model and are individually discussed in further detail below.

-

1.

The individual’s beliefs about the unknown nature of CLBP

Emotion regulation is also influenced by factors such as their beliefs and degree of self-efficacy [

37]. Research has suggested that uncertainty can be mapped as an emotion, which has signal value and is based upon the continual cognitive appraisal between what is known and not known, resulting in either a positive or negative affective response [

16]. Other emotions such as fear, defined as ‘a protective response to a current and identifiable threat’ are thought to influence uncertainty [

35]. The term ‘fear of the unknown’ broadly covers a range of physiological changes and intensities of an emotional response to an unknown, which similarly to the concept of hope, is influenced by several factors such as previous experiences, degree of importance, time and context offering important distinctions [

14]. Thus, ‘trait-fear of the unknown’ is predominantly influenced by previous experiences, whereas ‘state-fear of the unknown’ is influenced by both trait-fear and situational factors. Furthermore, the study by Carleton [

14] explored how fear of the unknown relates to other constructs including IU, emotions, attachment and neuroticism. Firstly, he presents increasing evidence that individuals who have emotional disorders have higher levels of ‘fear of the unknown’. This is supported by Hong and Cheung [

42] who undertook a meta-analytic review of 73 articles to explore how six commonly reported cognitive vulnerabilities (pessimistic inferential style, dysfunctional attitudes, ruminative style, anxiety sensitivity, intolerance of uncertainty, and fear of negative evaluation) are associated with anxiety and depression, finding a moderate to strong correlation for all variables, but IU was the most significant suggesting that fear of the unknown could be a central component for people with psychological disorders. Secondly, Carleton [

14] has identified how fear of the unknown and IU is linked with the ability to predict and control events to avoid negative outcomes which is an important part of Bandura’s [

43] self-efficacy theory and is deemed to have an essential role in an individual’s coping mechanism when encountering an unknown, to minimise its threat and enable effective self-management [

44]. Lastly, the continual appraisal between what is known and not known will also affect the emotional experience and response. When faced with a potential threat of an unknown situation, it causes increased autonomic arousal and activates a neurobiological mechanism known as the behavioural inhibition system which helps to appraise information, but it is typically biased towards negative outcomes and if this outlook is reinforced, it will exacerbate fear. Only when the appraisal between what is known and unknown becomes equal, will the individual be less evasive towards the potential threat [

14]. Conversely, others advocate IU is a form of distress intolerance meaning it can potentially be tolerated. Freeston and Komes [

16] proposed the somatic error theory of IU which is based on interpreting uncertainty as an internal feeling that is cognitively appraised through a process within the nervous system called interoception which plays an essential role in survival. Interoception processes are dynamic and influenced by sensorimotor and proprioceptive inputs in the brain with most occurring subconsciously, but some are attended to consciously. We have previously recognised how people with anxiety have a mismatch between actual and anticipated outcomes of an uncertain situation, and to a certain extent a small discrepancy is normal and is required to enable future estimates of probabilistic relationships or first order uncertainty. However, in people with psychological disorders, their interoceptive processes are already disregulated, so when they attempt to reduce the discrepancy, their negative emotions are often amplified and the sense of not knowing is appraised negatively. This theory provides a framework to outline how we respond to uncertainty and offers optimism that uncertainty can potentially be tolerated, but a lot more research is required, as carefully outlined in their study.

In order to address disregulated beliefs about the unknown, it is important to identify and understand the perceived threat [

16]. In relation to CLBP, a common theme that people with CLBP report that they are fearful of is losing their self-identity and the impact that this has on themselves, their relationships, employment and future prospect [

11]. Maintaining a positive self-identity was also a significant factor for the success of those enrolled on a pain management programme, as well as overcoming fears of movements or activities that tend to trigger or aggravate their symptoms [

10]. Afterall, it is well established that fear avoidance is a central mechanism for persistent pain and the most prevalent maladaptive ERS [

39]. Therefore, treatment interventions should initially focus on deconstructing fears through identifying the driving elements that are unknown or by addressing concerns. These findings were supported by Carroll et al [

45] who also found that across wider musculoskeletal disorders, addressing fears and focusing on realistic goals was essential in cases where a definitive diagnosis or structural cause were not possible. Another strategy is Physiotherapy care and supervised exercise to facilitate individuals to return to activities or movements that they are fearful of through graded exposure. Furthermore, there can also be additional benefits from undertaking supervised exercise as part of a group, because this provides a community and empowers individuals through witnessing others who are in similar situations doing movements that they fear [

10]. These findings were supported more broadly by Spink, Wagner and Orrock [

46] who undertook a systematic review to explore the barriers and facilitators for self-management in adults with chronic musculoskeletal conditions, concluding group participation made them accountable to attend, giving patients a sense of belonging and an opportunity to learn from others, although arguable this treatment approach does not suit everyone. Lastly, another common treatment approach for deconstructing negative emotions is CBT. A quasi-experimental study showed that CBT is effective at improving hope in people with CLBP, but it does not change their pain perception [

23]. These results were supported by Razavi et al [

47], who also found that those who had participated in a CBT programme were also better at self-managing their symptoms. However, what we still do not know is whether these suggested interventions are reducing disregulated beliefs about the unknown or whether they improve tolerance of uncertainty [

14].

-

2.

Fluctuating symptoms and its impact on their self-identity and future:

Hope not only influences how an individual copes with pain, but it can also affect their perception of their pain experience. A cross-sectional study by Wojtyna, Palt and Popiolek [

22] found that the level of state-hope depends on their previous experiences of pain and the presence of pain at that moment when they complete an outcome measure of hope. If people with CLBP had no pain at the time of completing the outcome measure, they had higher levels of state-hope, whereas those who were experiencing pain during the investigation had lower levels of state-hope, but this was only noted in individuals who had previously experienced severe pain. Another finding was related to previous pain experiences, showing that those who had previously experienced low pain intensities showed an increase in state-hope when pain reoccurs, demonstrating a complex relationship between hope and pain perception.

When living with chronic pain, people tend to focus on their symptoms, which often leads to negative emotions and psychological stress [

28]. A common theme across several qualitative studies validates that people with CLBP have self-doubt in their ability to cope with a condition that is ultimately poorly understood, and to also deal with the daily challenges that they face when their symptoms are variable and prone to reoccurrence, which in turn effects self-efficacy [

3,

11,

44]. Self-efficacy refers to an individuals perceived ability to complete a task which can be influenced by four key factors: their own previous experiences, by witnessing the actions of others, social persuasion and the individuals emotional and psychological well-being [

43]. More widely across chronic musculoskeletal pain, hope has been found to be negatively correlated with self-efficacy; meaning when people believe that they can control their symptoms, they feel more confident that they can self-manage the condition and therefore pursue their planned pathway to achieve their goals [

28].

One component that has been identified to improve hope in people with CLBP is through constructing an acceptable explanatory model for their pain [

10]. The biopsychosocial model incorporates the biological components alongside psychological and social influences [

23]. Whereas people who remain focused on the biomedical model often disregard a psychological component and remain focused on finding a structural cause, which is often not applicable for CLBP [

10]. The term ‘self-management’ is a component of the biopsychosocial approach that refers to a process in which the individual learns to effectively control the physical and psychological components of their symptoms, but this can take time and is often an element of ‘trial and error’ [

44,

46]. Bourke et al [

44] interviewed nine participants on their experiences of self-managing CLBP, concluding it is predominantly dependent on their pain perception and degree of self-efficacy. The most prevalent theme across all participants was self-doubt which was affected by fluctuating symptoms. During periods of self-doubt, it is essential to address the underlying areas of concerns or uncertainty, otherwise self-management strategies are not utilised and as a result, maladaptive ERS such as avoidance are typically utilised. However, when participants were supported to take part in activities and fulfil roles despite pain; it empowered them, challenging their pain beliefs and improving the likelihood of them achieving their goals supporting Bandura’s self-efficacy theory. Lastly, the least consistent theme was ‘living with pain differently’ which was only discussed positively by participants who no longer viewed their pain as a threat and had accepted a biopsychosocial explanation for their symptoms. In essence, making adaptations to an individual’s lifestyle threatens their self-identity. Thus, it is essential that clinicians explore what is meaningful to the individual in order to create relevant goals [

17]. Additionally, patients need to accept a biopsychosocial approach before they are likely to comply and succeed with self-management strategies [

44]. This is because periods of self-doubt will continue to prevail, reducing self-efficacy and their ability to uphold their self-identity causing a reduction in their perception of hope for the future [

46]. Clinical recommendations include active listening and the use of risk stratification tools to establish where people with CLBP are in the continuum between self-doubt and the utilisation of effective self-management strategies to implement an appropriate action plan [

7,

44]. Another suggested strategy is to improve their ability to be cognitively flexible. As previously discussed, cognitive flexibility is an important component of emotion regulation because it allows the individual to achieve long term goals despite pain and other stressors [

48]. Individuals who are cognitively flexible would replace self-doubt with resilience and have more confidence to self-manage their fluctuating symptoms by reducing its threat [

49]. A study by Gentili et al [

48] highlighted the importance of psychological flexibility as a resilience factor in people with chronic pain finding the concept had a significant indirect relationship with symptoms and function. Cognitive rigidity is often displayed through avoidance which needs to be addressed through exposure-based interventions, but also engaging in value-based behaviours which influences the individual’s values and beliefs. However, extensive research is still required to explore effective interventions for improving cognitive flexibility, such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, before it is then compared against current treatment interventions such as Physiotherapy care.

-

3.

The clinical encounter and diagnosis.

Scarry (1985] famously reported that “pain is simultaneously the most privately certain and publicly doubted phenomena” [

50] (p. 34). Given that pain is not a visible disability, individuals strive “to be heard” and not “fobbed off”, thus active listening during CLBP consultations is essential [

3,

10]. This issue is highly prevalent in CLBP because their symptoms do not fit with the biomedical model, meaning individuals with CLBP often feel that they are not believed [

10,

50]. As a result, people who are uncertain about their condition typically attempt to legitimise their symptoms by seeking further input such as an expert opinion, or diagnostic investigations [

51]. In terms of information sources, above all, it is the opinions, and the information provided by HCPs that people value the most and there is strong evidence that their beliefs are correlated with those of their clinician [

52]. However, unfortunately not all CLBP consultations result in positive outcomes because the clinical encounter can pose as either a threat, or an opportunity [

45]. The individual’s perception of the clinician’s willingness or ability to help them has been identified as a theme that can affect their ability to manage uncertainty [

12]. Fundamentally, it is important to remember that how and what we say, can also have a significant and lasting influence on the individual’s future. For example, in circumstances where people with CLBP have been advocated to rest or avoid aggravating activities, it can trigger fear avoidant behaviour. Whereas in contrast, others who reported that they received adequate reassurance, support and explanations from their clinician were instead empowered and were more prepared to make appropriate lifestyle adaptations to self-manage the condition [

52]. To a lesser extent, the individual’s wider social network can also have similar positive or negative influences on their expectations, attitudes and overall prognosis [

45].

The concept of trust is paramount within healthcare services to uphold an effective therapeutic relationship, which is also based on openness and honesty [

50]. Even though all medical encounters are hinged on uncertainty, it remains a difficult issue to embrace and navigate from both a patient and clinicians’ perspective [

53]. This is because uncertainty within clinical encounters has two dimensions which are interlinked, the first is ‘medical uncertainty’ which refers to limitations of biomedical knowledge which will affect how HCPs explain the diagnosis and prognostic outlook, and the other is ‘existential uncertainty’ which relates to the individual’s awareness of how their future is undetermined [

54]. Costa et al [

53] interviewed 22 clinicians from a range of professions who treat individuals with CLBP including, Allied Health Professionals, Chiropractors and Consultants, concluding uncertainty resonated with them all, commonly based around navigating the individual’s emotions and mental health status, making therapeutic decisions in relation to the individuals lifestyle, but also how to communicate the concept because it is often influenced by their own biases and previous experiences. Other studies have found that Physiotherapists in particular, have difficulty managing diagnostic uncertainty when treating people with CLBP because they feel they do not have sufficient knowledge and skills, nor time and resources to manage the complexity of the condition effectively [

54]. As a compensatory strategy, HCPs may avoid or minimise discussions around uncertainty to uphold the perception that they are an expert, or to avoid the risk of compromising their authority [

54]. However, this lack of acknowledgement or openness can be detrimental to trust and can result in epistemic injustice [

3]. Epistemic injustice refers to when an HCP utilises their authority to influence their patient’s decisions so that they align, but it can also refer to the discreditation of the individual’s reporting’s [

50]. Instead, we should promote the principle of epistemic humility by recognising the limits of clinical expertise and scientific research, embracing uncertainty through acknowledging value in information from a range of sources and upholding credibility to the testimonies of our patients and their experiences in conjunction with our professional worldview [

53] Additionally, instilling epistemic humility within clinical practice could also help to reduce the power asymmetry within therapeutic relationships [

50]. However, one of the issues that we face when addressing uncertainty is its complexity. Despite several attempts there is still no agreed framework, consequently different professional groups continue to manage uncertainty in different ways [

53,

55]. Mol [

56] outlines two contrasting approaches for managing uncertainty: ‘the logic of care’ and ‘the logic of choice’. Often HCPs (particularly in the Western world) focus on offering the individual choice through outlining facts. However, this approach requires the individual to have high levels of self-efficacy; to feel competent and confident with their role in contributing to decisions, and that they are generally able to self-manage their condition. In contrast, people with CLBP typically have low self-efficacy and do not always respond positively to choice because they have difficulty navigating one uncertain pathway against another. Therefore, in these circumstances, Mol [

56] would propose the application of ‘the logic of care’ which promotes a patient centred approach, focusing on relevant and achievable goals and enabling them to make acceptable lifestyle adaptations to ultimately learn how to self-manage their condition [

44]. Another issue is highlighted by Mackintosh and Armstrong [

26] is that offering choice with regards to tests, treatments or procedures can result in over diagnosis or treatment.

Lastly, another contributing factor linked to the clinical encounter is essentially the diagnosis, which also includes how this is communicated to the individual. Typically, across musculoskeletal care, clinical practice focuses on ruling out serious pathology, as opposed to ruling in a definitive diagnosis [

45]. However, within society, there is a strong perception and expectation that a thorough examination, sometimes involving accompanying diagnostic investigations such as blood tests or imaging, will lead to a legitimate diagnosis, which in turn enables effective treatment interventions and hope for the resolution of their symptoms [

3,

10,

57,

58]. Despite our understanding of patient expectations, national guidelines do not recommend imaging for low back pain with or without radicular pain in the absence of red flags or a neurological deficit [

7]. This is because in most cases (90-95%), there is not an identifiable structural cause in people with CLBP, meaning pathological findings from imaging frequently do not correlate with the individual’s symptoms [

3]. It is well established that in cases where there is not a clear diagnosis or explanation for their symptoms, it has a negative impact on their social, cognitive and emotional functioning [

51]. Additionally, when a structural cause is not identified through imaging, it can result in a contradictory outcome because it still does not lead to a clear diagnosis and at times incidental findings can occur, which fosters further anxiety, fear or causes the individual to question their pain experience, also failing to result in improved outcomes [

10,

12]. Therefore, this mismatch between patient expectation and evidence-based practice guidelines can cause further detrimental psychological affects to individuals with CLBP, as well as having a negative impact on the therapeutic relationship if it is not appropriately or effectively communicated [

3].