4.1. RQ1. How Has Farahzad Developed in Recent Decades and What Types of Urban Fabric Now Prevail?

The Farahzad neighbourhood was largely untouched by urban expansion until the late 1960s. Aerial photographs from the 1970s and earlier show that residential buildings were limited to the Farahzad villages and hamlets, and most of the lands were dedicated to agriculture and orchards. It was not until the late 1960s that construction in the southern parts of the area began to encroach on the village lands. In the mid-1970s, following the passing of a new law facilitating the building of residential complexes and townships, haphazard house construction progressed, leading to numerous environmental problems and the destruction of natural spaces.

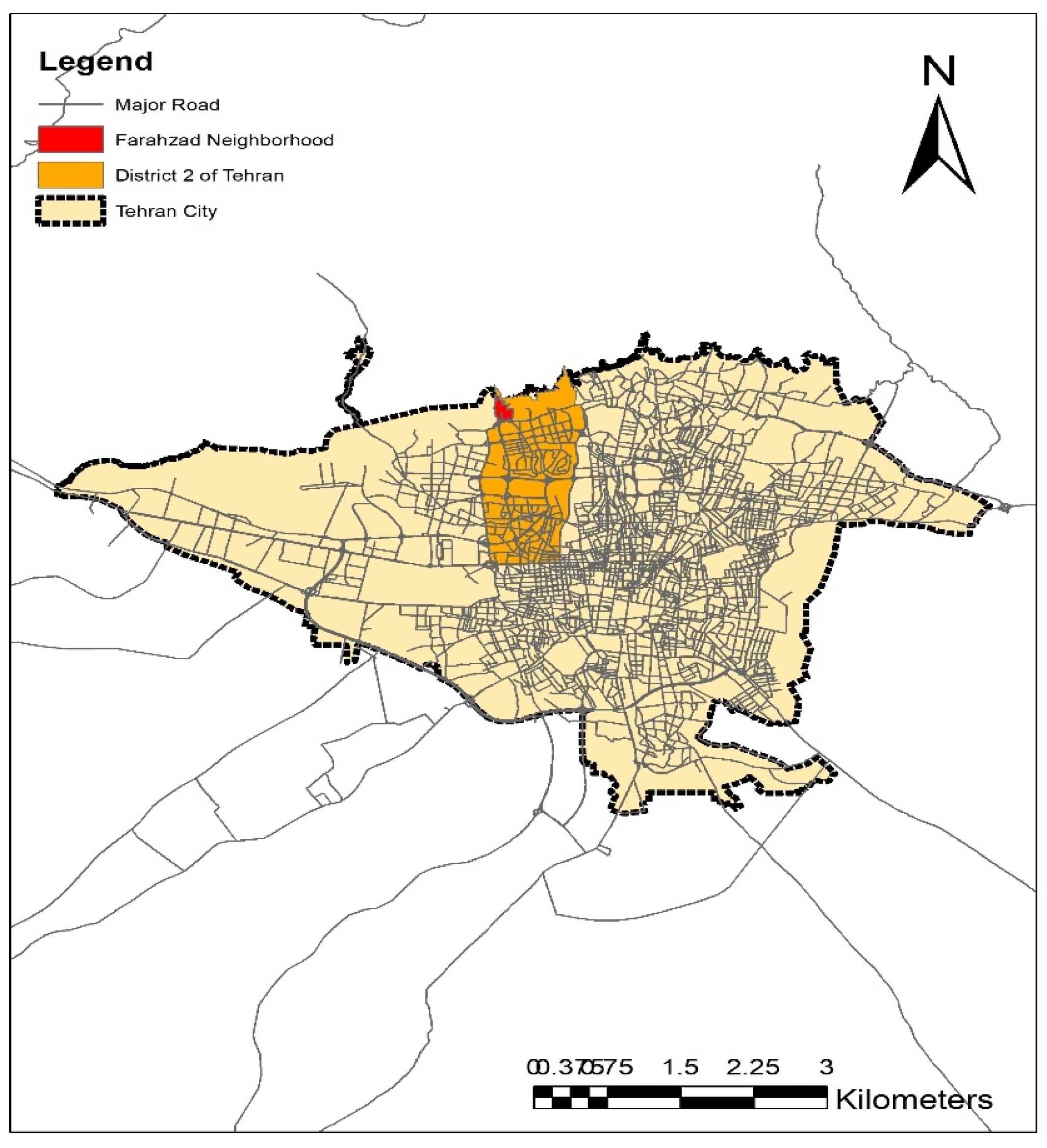

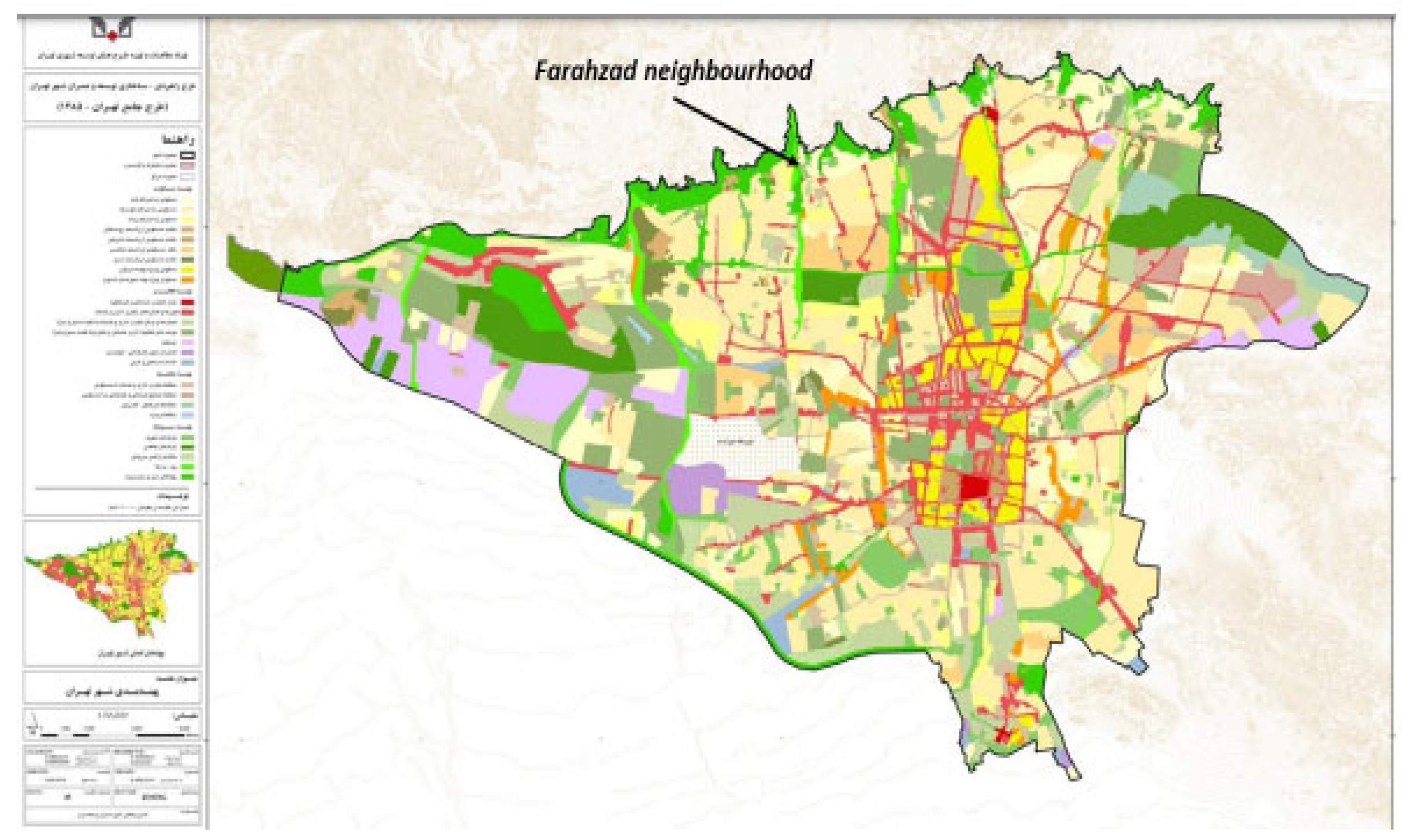

The detailed plan for District 2 indicates a mix of land zone classifications for the Farahzad neighbourhood (

Figure 4 and

Table 2). As regards residential zoning, the neighbourhood includes zones of differing densities and environments (R112, R122, R212, and R241), with zone R112 (low-density residential) covering the largest area in terms of allocated space. The village areas and a significant portion of old Farahzad are classified as R212 and R241 (valuable rural or green residential zonings). The activity zones (S222 and S332) are to the south and south-east, and include some lands currently vacant and unoccupied, plus a multi-story car park under construction. However, the main band of commercial/business zoning (S222) encompasses the lower section of Emamzadeh Davood street, stretching from the lower boundary of the Yadegar-e Emam Expressway into the Farahzad neighbourhood. To the north of this commercial central strip is a mixed zone of business and residential uses, including commercial and office units, within residential areas, between Farahzad Square and Pachenar. Finally, the protection zones include the river valley to the west, the northern limits in the foothills of the mountains and two parks within the neighbourhood at Golepaad and Khordad.

This land zoning to a large extent reflects the current situation on the ground, although much of the informal dwelling construction has been contrary to some of these zonings.

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 provide an indication of how Farahzad has expanded in the period 2000 - 2023. As open land was developed for mass housing projects, cooperatives, and infrastructure in other parts of the city, so more people re-located into the Farahzad neighbourhood, which remained relatively undeveloped, in search of more traditional housing or informal dwellings. This resulted in the division and conversion of gardens into separate plots for construction, occupation of the protected riverside areas, and construction in the foothills of the surrounding mountainous areas. Development has spread around the main north-south axis (Emamzadeh Davood street, zoned for mixed and activity uses in

Figure 4), which was once the route of passage for pilgrimage caravans, and around the tangential roads and pathways.

Today, Farahzad exhibits a number of contrasts in land use and the nature of the landscape. Its pleasant climate has given rise to a number of tourism related businesses, but this has also attracted low-income individuals seeking employment in these tourist establishments. The lack of adequate housing for these migrants has led, as noted above, to the growth of shanty, informal developments, characterised by a lack of adequate services, poverty, insecurity and a resultant low quality of life. The majority of the inhabitants currently living in these shanty areas initially lived in tents, which were destroyed by the municipal authorities. Because of such actions, a lack of trust in the public authorities has increased. This is a recurring theme in the informal settlements literature. Atkinson [

8], for example, in his comprehensive study of this literature, concluded “programs may not work because there is a lack of trust in the government and its efforts”, and that “symbolic efforts are not enough” (para. 62). In Farahzad, however, the shanty dwellers constructed new dwellings, mainly of clay and straw, especially along the Farahzad River. Allahyari et al. [

29] have emphasized the significance of river valleys in influencing land use and development patterns, and here, the availability of common land and amenable water supply have encouraged shanty developments in these riverside locations.

In contrast, the urban environment in the eastern part of Farahzad is of a higher quality, with better access to the city center, and newer and better-quality housing with relatively affluent inhabitants [

30]. This is adjacent to the main area of business and commercial activity which has grown up around Emamzadeh Davood street and the Yadegar-e Emam Expressway, which curves around the southern border of the neighbourhood, leading eastwards. The residential areas cover most of the central part of the neighbourhood with green zones in the periphery to the north and west.

As a result of this significant growth process, the most common land use in Farahzad is residential, accounting for approximately 45% of the land area (

Table 3). Vacant land makes up 32% of the neighbourhood, much of this land remaining fallow due to a lack of clear ownership and official documents. The challenging morphology of the area, with its mountains and hills to the north and river valley to the west, further complicates construction efforts. Agricultural land has been reduced to less than 5% of the land area, mainly used for cultivating diverse produce such as stone fruits, grapes, walnuts, and various vegetables. These agricultural plots, which serve as a food source for Tehran, are mainly located in the northeast part of the neighborhood.

Figure 7 provides a detailed picture of land use in 2023. The primary commercial land uses in the area include shops, real estate agencies, car galleries, car repair shops, and restaurants, which are located in the south and central areas around Farahzadi street. Urban facilities are integrated into these commercial areas, and additionally, there are several shrines, including Abu Taleb and Saleh, as well as important mosques that play a significant role at both local and supra-local levels. Two notable urban facilities include the health services center located in the north and a parking area situated in the west. The administrative area in the southeast is designated for the Farahzad sports complex.

In summary, the main changes in land use over the period 2020 -23, are: firstly, the significant growth of informal settlements in the Farahzad river valley on the western margin; secondly, the significant infilling – comprising both residential and business developments - around the main north to south and east west axes (Farahzadi/Tabarok streets; and Emamzadeh Davood street); thirdly, the expansion of modern apartment blocks on the eastern side of the neighbourhood; fourthly, the provision of new service infrastructure, including the sports complex, new parks and green spaces. The neighbourhood has thus changed significantly in this period, accommodating a growing population as Tehran continues to expand, experiencing environmental challenges, notably in the Farahzad valley area, with demographic shifts and some conservation initiatives.

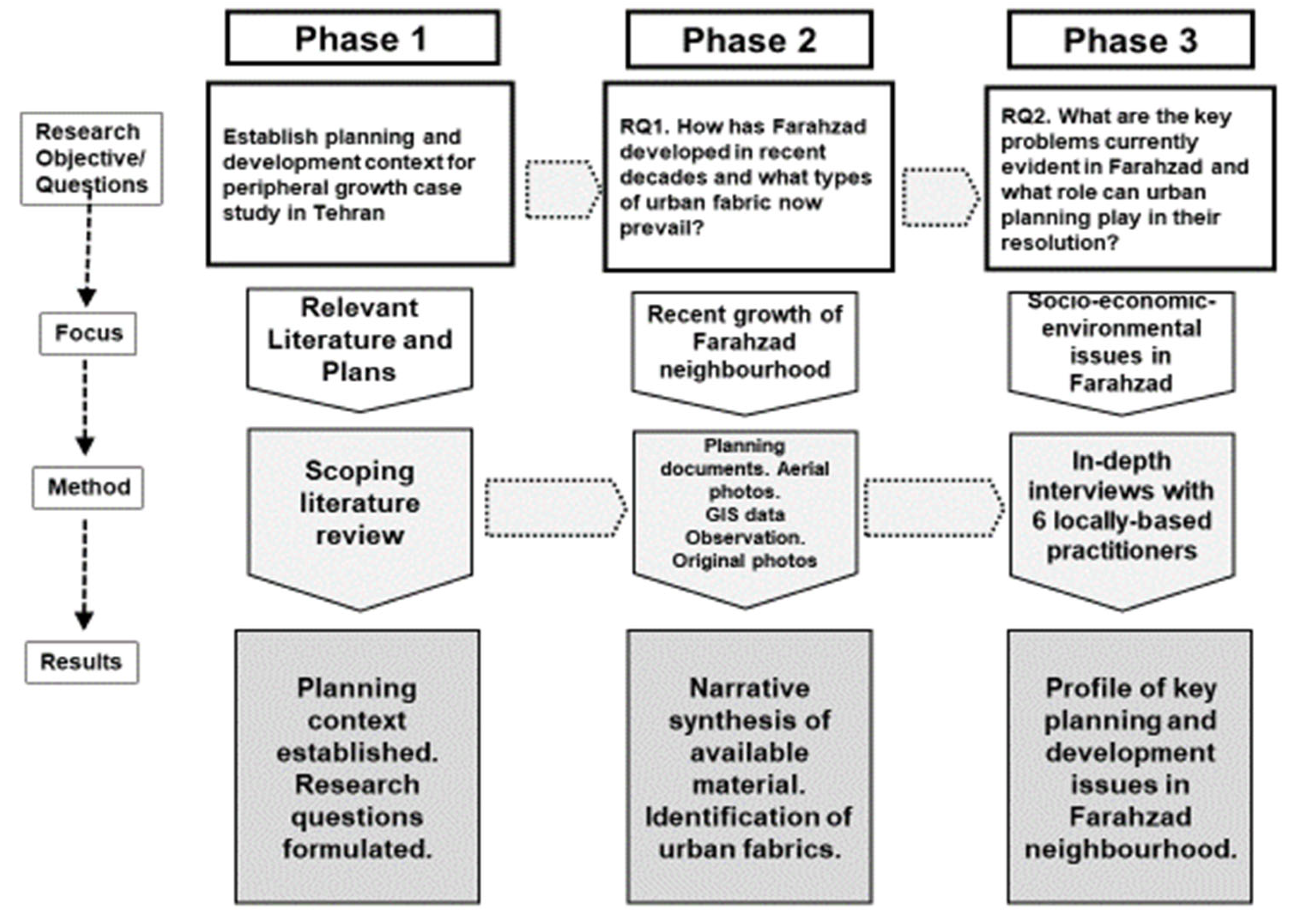

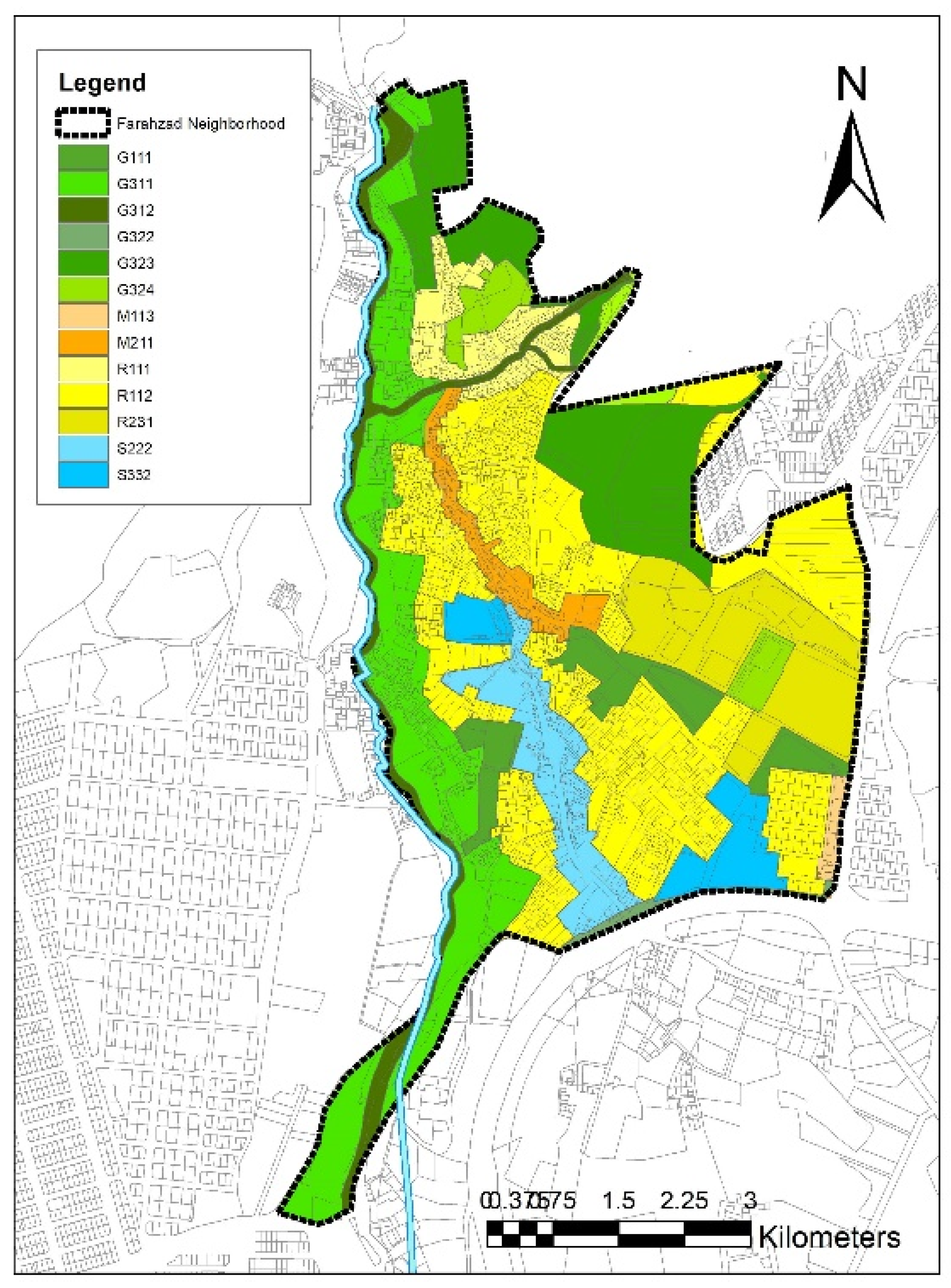

Within this changed urban landscape – and building upon existing concepts in the existing literature - different urban fabrics (or patterns) can be defined and identified as an alternative to simple land use zoning. Population density, migration statistics, population ethnicity, dwelling typology, infrastructure quality and green zoning were all considered in conjunction with general land use assessment to define five urban fabrics evident in the neighbourhood.

The original core of the Farahzad neighborhood, along with its gardens, have over time been impacted by land division to create an organic fabric with a local identity. Around this old core, four other urban fabrics have evolved to create today’s urban landscape. Large areas of worn-out urban fabric are in evidence to the north, and to the west, on the banks of the Farahzad river, which include many of the informal settlements which have caused many problems and are rapidly penetrating into the surrounding fabrics, notably the areas of green space with which they are now interweaved. To the east of the neighbourhood, a modern urban fabric dominates, where – in general - there are better living conditions in newly constructed buildings where better economic conditions prevail. To the south, a small linear band of tourism fabric has evolved around the main routeway and commercial centre. These five urban fabrics (

Figure 8) are detailed more precisely below.

The old (Organic) urban fabric includes the old village settlement of Farahzad, which has been shaped by its natural features, local economy, and rural culture (

Figure 9). It contains Emamzadeh Davood street, the most important access road to Farahzad from Tehran, and the narrow, winding alleys and passages branching off from it. It is characterized by indigenous architecture with a variety of occupation patterns and climatic orientation, and some remaining old trees alongside the traffic routes. The nature of this fabric reflects the initial methods of dividing gardens and the topography of the area, with north-south accesses being used for internal communications and east-west alleys for access to the gardens. In the north and western parts of this fabric area, plots tend to be smaller and construction more unstable. This has led, particularly in the northern section, to a degraded dwelling stock, with residents vacating the area to be replaced by non-locals, including Afghans. Nevertheless, social cohesion and local participation are significant features of this old fabric. This is visible during events like Ashura (a day of commemoration in Islam), where residents demonstrate their unity with black mourning flags.

The modern urban fabric is located in the eastern side of the neighbourhood and includes modern house construction built in accordance with the detailed plan of Tehran. New construction has generally followed the approved building regulations, with plots measuring around 100 to 200 square meters in which newer developments have been constructed, making up about 20% of the neighbourhood as a whole. The fabric features modern, multi-story buildings with enhanced amenities and designs, and higher standard urban infrastructure, such as water, electricity, gas networks, and public transportation. Population density here has significantly increased due to the rise in buildings and residential units. Commercial areas, such as shopping centers, restaurants, and offices, have also been developed. Good access roads and sufficient passage width are typical in this fabric, and proximity to major roads like Kouhsar and the Yadegar-e Emam Expressway ensures good connectivity to other parts of the city (

Figure 10).

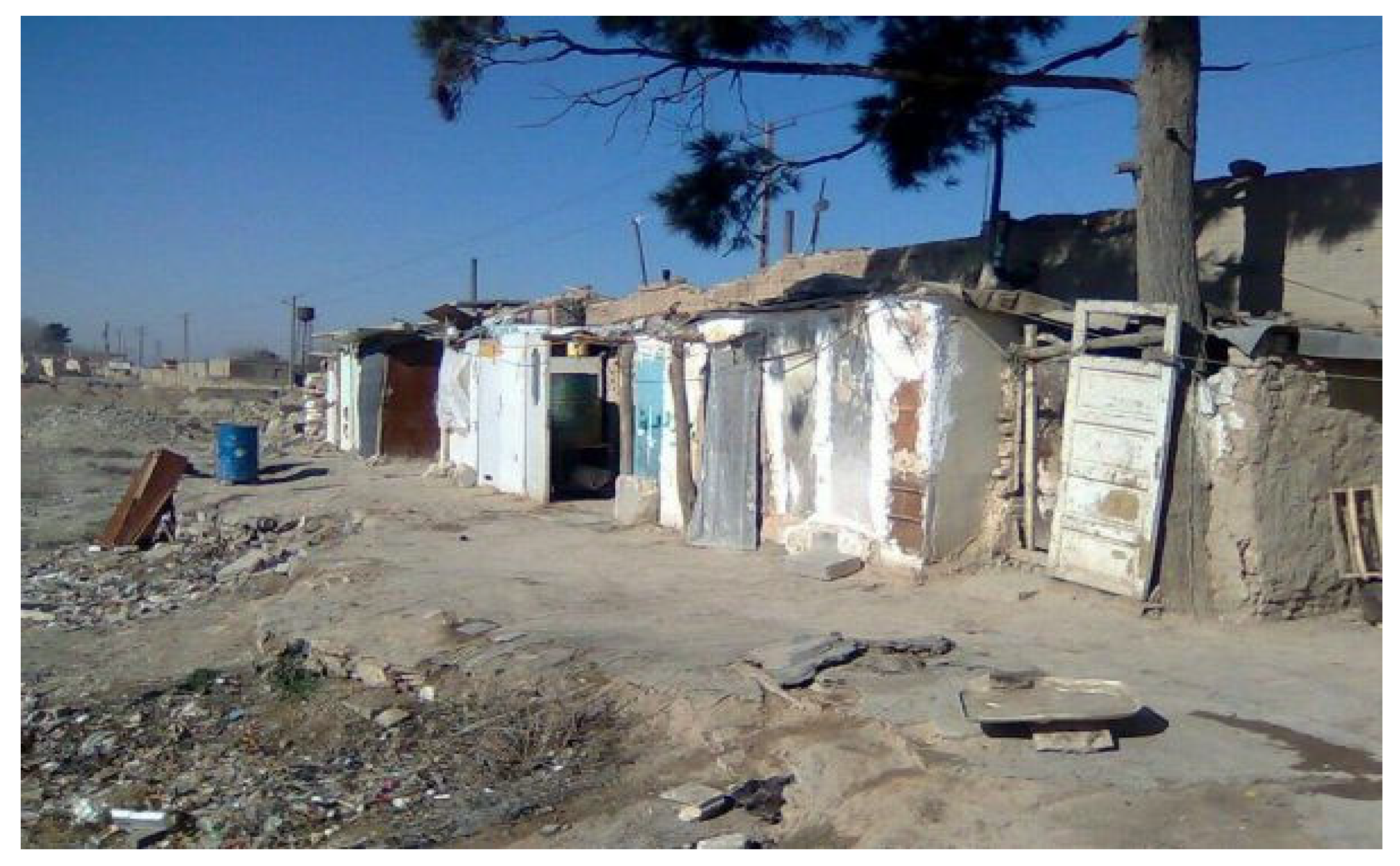

The worn-out urban fabric is typified by illegal or informal development (

Figure 11), socio-economic problems, poor environmental quality, architectural vulnerability, and a severe shortage of urban public services. This fabric is mainly in evidence in the northern and western parts of Farahzad, on the outskirts of the old town and near the Farahzad river, and requires new rehabilitation and management policies. Many dwellings are in irregular shapes with primitive architecture and there is thus no one dwelling design that typifies the worn-out urban fabric.

The tourism urban fabric is found within the organic urban fabric and retains some of the same features. Most of the main structure of this area is part of the old fabric of Farahzad village, but it now predominantly performs non-residential functions. Economic activities in Farahzad have shifted from traditional agriculture and livestock to leisure activities and tourism. Many gardens have been converted into garden-restaurants, lining the main street with restaurants and teahouses, which are primary attractions and revenue sources. This rapid development, while economically beneficial, has caused spatial disorder and potential social and cultural issues. The Yadegar-e Emam Expressway has facilitated access to Farahzad, boosting the popularity of these leisure facilities. In part to cater for the tourist trade, businesses such as car washes, repair shops, and other workshops have increased in recent years, interspersed with these recreational activities [

31].

The natural and green urban fabric comprises gardens and orchards in which a variety of fruits are grown, using traditional farming methods for higher quality. Beyond crop production, these orchards provide crucial employment and help preserve rural culture. This fabric is found alongside the river valley in the west (

Figure 12) and is interwoven with areas of worn-out urban fabric and shanty developments in some places.

4.2. RQ2. What Are the Key Problems Currently Evident in Farahzad and What Role Can Urban Planning Play in Their Resolution?

This section draws upon evidence from 6 in-depth interviews with local government officials and individuals working in development agencies (private and NGOs), as shown in

Table 1 above.

Farahzad clearly suffers from a range of interconnected social, economic and environmental problems that impact the future planning and development of the neighbourhood, as attested to by several of the interviewees. P2, a Neighbourhood Development Officer observed that “the people of Farahzad neighborhood have obvious poverty - most of them are marginalized”. P4 works for the Mehr o Mah Institute (a local charitable agency), “with the aim of empowering children and women, which is organized according to the needs of the people in the educational and literacy classes in the institute”. P4 observed that “most of the residents who live in the Farahzad area are immigrants who have a low level of literacy and their income is low, so the living conditions in this area are very low”. P4 identified “Tabarok Street towards Farahzad River” as the main problem area in the neighbourhood, where there was an “accumulation of sleeping bags”, and other issues included “the lack of training centers, treatment centers, addiction and security centers [and] the old texture and the existence of stairwells that greatly reduced security”. Women were aided in earning a living by “training classes in the field of skill building, and selling handicrafts through virtual networks or holding public exhibitions”. P6, who works for a non-governmental charity (Rooyesh-e Nahal Institute), which provides a range of services for social, supportive, educational, and prevention purposes, added that the biggest problems were the sale and consumption of drugs, homeless people, working children and fugitive women and girls.

P6 also highlighted that “there were many ethnic prejudices and ethnic fights in Farahzad … we try to teach the concept that today's necessity is to live together”. P2 noted that religious conflict existed: “There is a hidden ethnic conflict in the neighborhood. Afghans, Torkamans and Kurds are Sunni; the Lors and the Khalkhalis are Shiite, and for this reason there is a hidden conflict between them, but it is not so much that they cannot live together, but there is a distance between them, so that the Sunnis have a mosque for themselves and the Shiites one for themselves”.

There are also problems with the physical infrastructure of the area. P2 stated that “the problem of garbage inside the neighborhood is very important because the garbage trucks cannot move inside the narrow alleys, and because of this, garbage is left by people in the place”. P2 also pointed out that “the neighbourhood does not have a sewer network and the sewage is flowing in the streets and a part of it flows into the river valley, which has caused pollution and health problems”….“some houses do not have a bathroom and they heat and bathe in a pit of water, which creates difficult conditions in winter”. P2 emphasised that communications improvements are needed: “the most important traffic plans that we proposed and want to implement are the connection of Yadegar-e Emam to Farahzad neighborhood, which is now cut off, and the other is to reach the public transportation network, because Farahzad does not have a metro station, bus, taxi, or even minibus”.

Several of the interviewees highlighted the need for a local plan to provide the necessary planning and regulatory framework for addressing the urban problems in the neighbourhood. P1, for example, emphasised that “Farahzad's biggest problem is the lack of a subordinate [local] plan that can be cited for urban development and urban design, and obtaining permits, etc.”. He emphasized the need for a local plan “to carry out an urban design for this area and get an approval from the Article 5 Commission”. He stressed the significance of the lack of a regulatory framework. Without the local plan approval “if someone wants to do something there: issuance of a permit, reconstruction, etc., there is no document on hand as a criterion for action for the municipality”. P1 talked of the content of a local plan drawn up with consultants and awaiting approval. It includes the “stabilisation of residences”, “ecologically correct reconstruction”, and “the organization of the restaurants”. P3 opined that as regards getting a local plan approved, “the municipality does not perform its main duty”. This lack of a clear framework for development has made attracting private investment into the neighbourhood more difficult. F2 reported the problems of attaining investment: “one of the capital owners, who is of Farahzadi origin, refused to invest in Farahzad and invested in the Opal business complex instead”. F2 suggested that “development incentives should be done first to encourage investors”.

The lack of ownership documentation is also a major hurdle in progressing future development. P1 observed “in my opinion, preserving the traditional texture and organizing it, and expanding the uses that attract the population, such as native and student residences, can be effective, but all this takes time and requires a lot of infrastructure, and this lack of infrastructure puts off investors…. the traditional fabric must be restored and secured. …. the problem is that we do not have ownership documents”. P3, a local council member, reinforced these points: “our priority has been the local plan for Farahzad. The main problem of Farahzad is the residents' ownership documents. Construction permits are not given, people build without permits, which the municipality demolishes, and the ruins are a place for drug addicts”.

P2 also highlighted this issue, asserting that “the most important problem that the people of the neighbourhood are facing is the problem of ownership, and they are not the owners of the houses they live in, because these lands belong to big owners, and at the beginning of the Revolution [1979], these people either ran away or bequeathed these lands to their children and their children either endow or abandon these lands”. P2 concluded that “for this reason, many residents of the neighbourhood (even those who have lived in the neighborhood for nearly fifty years) do not have ownership documents, and this has caused Farahzad to become an informal settlement”.

The potential of tourism and restaurant development was highlighted by several interviewees. P2 observed “it [the neighbourhood] has summer weather and in the past people came to Farahzad for recreation, climbing and the pilgrimage to Emamzadeh Davood, and the neighborhood was very prosperous and has a very favorable climate both in the past and now”. P1 noted that the neighbourhood’s restaurants “have definitely been effective in Farahzad's economy, but they must be organized and controlled, in terms of environmental measures and protection of traditional gardens”. P2 saw the growth of restaurants as “definitely positive. … in general, the presence of activity there creates employment and establishes the cycle of the economy. Like Hossein's restaurant, where all the employees are drug addicts who have quit and are working there. For this reason, we see the performance of these restaurants and canteens as quite positive and think that they are useful in terms of tourism”.

In summary, the neighbourhood faces a range of interrelated social-economic problems, exacerbated by the lack of an effective planning framework for development, lack of investment, and poor physical infrastructure. This has created a downward spiral of poverty and deprivation in much of the neighbourhood, alleviated only by limited municipal initiatives and charitable foundations. It has suffered from the rapid and haphazard urban expansion of Tehran into a rural suburb. As P3, a local council member, observed “Farahzad neighborhood was originally a village that was forced into the city due to the development of urbanisation, but its economy, culture, way of life and even its problems are reflective of its former rural life. Farahzad is neither a village nor a city”. This is has resulted in a situation in which, as P2 notes “lack of trust is normal”.

The work of voluntary organisations has been, and will continue to be, needed in Farahzad. The range of problems they face is illustrated by P5, who works as a volunteer for the Emam Ali Community Institute. P5 outlined the broad scope of their work: the charity focuses on “cultural aspects as well as economic activities; education of children left out of school; tutorial classes; training classes for income-generating professions such as sewing and needlework; literacy movement; financial facilities in the form of loans and non-financial support to start a business; recreational camps; support in the field of mental health promotion; supporting products and helping to sell them”.

The approval of a local plan and associated regulations to provide a framework for future development and land ownership ratification is urgently required, but the neighbourhood’s challenges go far beyond mere planning. The downward spiral of poverty and economic struggle is likely to continue until there is a significant change in the wider political system. Until then, the Farahzad neighbourhood is likely to remain as an in-between settlement in the urban periphery of one of the world’s major conurbations.