Submitted:

02 November 2024

Posted:

04 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample Selection and Research Tools

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Results

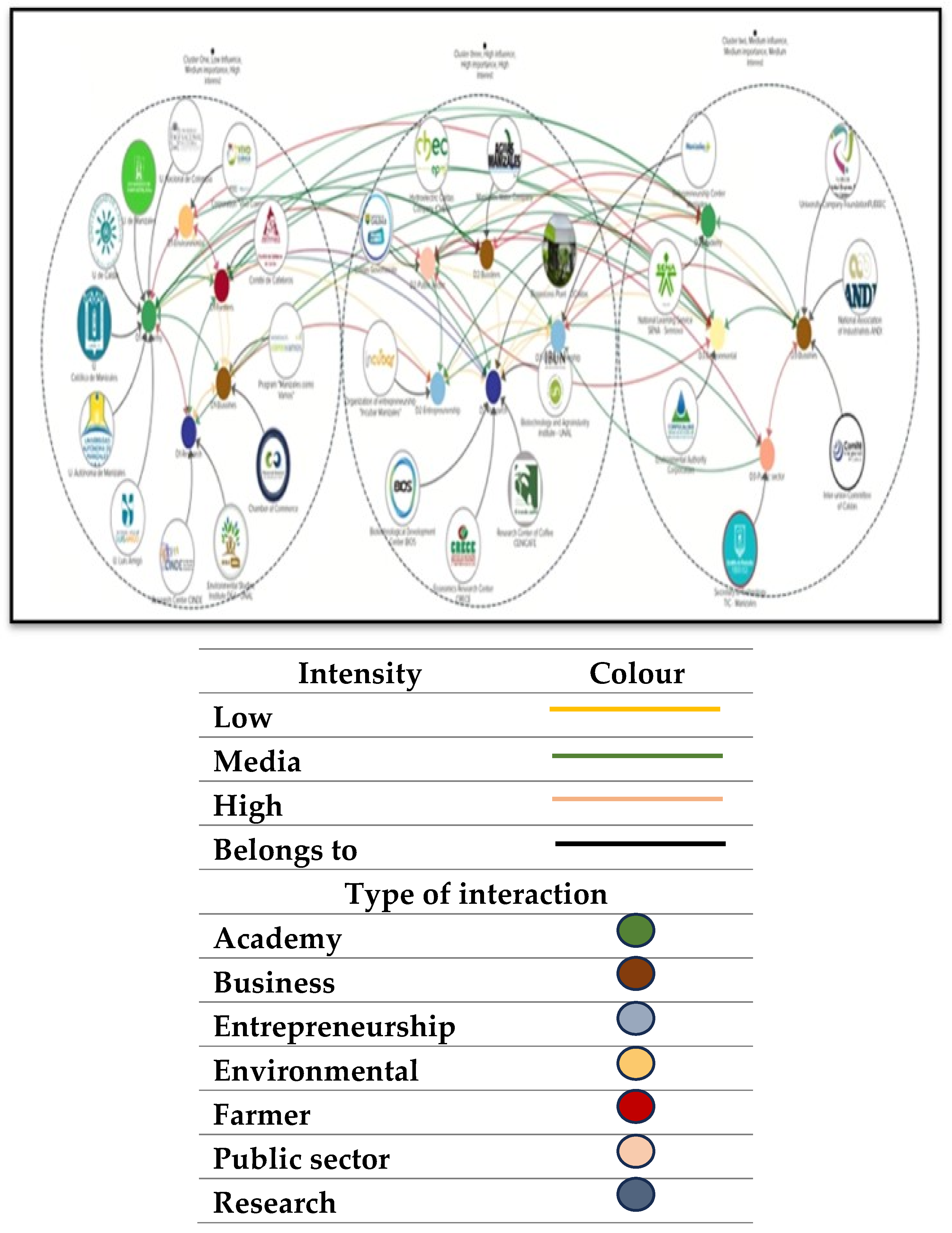

4.1. Networks of Research

4.2. The Formal and Informal Institutional Infrastructure

4.3. Forging Strategic Alliances

4.4. Risk in Innovation and Development Blocks

5. Discussion

5.1. Integration of Stakeholders and Their Importance, Influence and Interest in TIS

5.2. Implications for TIS for Transitioning to Bioeconomy

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commission. Innovating for Sustainable Growth. A Bioeconomy for Europe. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/1f0d8515-8dc0-4435-ba53-9570e47dbd51 (2012).

- European Commission. A Sustainable Bioeconomy for Europe: Strengthening the Connection between Economy, Society and the Environment Updated Bioeconomy Strategy. http://europa.eu (2018). [CrossRef]

- Sołtysik, M.; Urbaniec, M.; Wojnarowska, M. Innovation for Sustainable Entrepreneurship: Empirical Evidence from the Bioeconomy Sector in Poland. Adm. Sci. 2019, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawel, E.; Pannicke, N.; Hagemann, N. A Path Transition Towards a Bioeconomy—The Crucial Role of Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsche, U.; et al. Future Transitions for the Bioeconomy towards Sustainable Development and a Climate-Neutral Economy Knowledge Synthesis Final Report. https://ec.europa.eu/jrc (2020). [CrossRef]

- Robert, N.; Giuntoli, J.; Araujo, R.; Avraamides, M.; Balzi, E.; Barredo, J.I.; Baruth, B.; Becker, W.; Borzacchiello, M.T.; Bulgheroni, C.; et al. Development of a bioeconomy monitoring framework for the European Union: An integrative and collaborative approach. New Biotechnol. 2020, 59, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giampietro, M. On the Circular Bioeconomy and Decoupling: Implications for Sustainable Growth. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 162, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottinger, A.; Ladu, L.; Quitzow, R. Studying the Transition towards a Circular Bioeconomy—A Systematic Literature Review on Transition Studies and Existing Barriers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Börner, J.; Förster, J.J.; Von Braun, J. Governance of the Bioeconomy: A Global Comparative Study of National Bioeconomy Strategies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, K. & Tyfield, D. Theorizing the Bioeconomy: Biovalue, Biocapital, Bioeconomics or... What? Sci Technol Human Values 38, 299–327 (2013).

- Guzmán, A.B.; Centeno, J.P.; Rojas, C.M.P.; Jiménez, H.H.R. Is bioeconomic potential shared? An assessment of policy expectations at the regional level in Colombia. Innov. Dev. 2021, 13, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wydra, S. Value Chains for Industrial Biotechnology in the Bioeconomy-Innovation System Analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisvold, G.B.; Moss, S.M.; Hodgson, A.; Maxon, M.E. Understanding the U.S. Bioeconomy: A New Definition and Landscape. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, S.; Kumar, A.N.; Shanthi Sravan, J.; Chatterjee, S.; Sarkar, O.; Mohan, S.V. Food waste biorefinery: Sustainable strategy for circular bioeconomy. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 248, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlgemuth, R.; Twardowski, T.; Aguilar, A. Bioeconomy moving forward step by step – A global journey. New Biotechnol. 2021, 61, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loorbach, D.; Rotmans, J. The practice of transition management: Examples and lessons from four distinct cases. Futures 2010, 42, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamborg, C.; Anker, H.T.; Sandøe, P. Ethical and legal challenges in bioenergy governance: Coping with value disagreement and regulatory complexity. Energy Policy 2014, 69, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frow, E.; Ingram, D.; Powell, W.; Steer, D.; Vogel, J.; Yearley, S. The politics of plants. Food Secur. 2009, 1, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levidow, L.; Birch, K.; Papaioannou, T. EU agri-innovation policy: two contending visions of the bio-economy. Crit. Policy Stud. 2012, 6, 40–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, F.; Smith, A. Restructuring energy systems for sustainability? Energy transition policy in the Netherlands. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 4093–4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosman, R.; Loorbach, D.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Pistorius, T. Discursive regime dynamics in the Dutch energy transition. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transitions 2014, 13, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosman, R.; Rotmans, J. Transition Governance towards a Bioeconomy: A Comparison of Finland and The Netherlands. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, J.; Giurca, A.; Brockhaus, M.; Toppinen, A. Actors and Politics in Finland’s Forest-Based Bioeconomy Network. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, F.; Hansen, T.; Hellsmark, H. Innovation in the bioeconomy – dynamics of biorefinery innovation networks. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2018, 30, 935–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellsmark, H.; Mossberg, J.; Söderholm, P.; Frishammar, J. Innovation system strengths and weaknesses in progressing sustainable technology: the case of Swedish biorefinery development. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 131, 702–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, K.J.; Klerkx, L.; Poortvliet, P.M.; Godek, W. Exploring barriers to the agroecological transition in Nicaragua: A Technological Innovation Systems Approach. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 44, 88–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, F.X.; Canales, N.; Fielding, M.; Gladkykh, G.; Aung, M.T.; Bailis, R.; Ogeya, M.; Olsson, O. A comparative analysis of bioeconomy visions and pathways based on stakeholder dialogues in Colombia, Rwanda, Sweden, and Thailand. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2022, 24, 680–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, V.L.; Schanz, H. Agency in actor networks: Who is governing transitions towards a bioeconomy? The case of Colombia. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 225, 728–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergek, A.; Jacobsson, S.; Carlsson, B.; Lindmark, S.; Rickne, A. Analyzing the functional dynamics of technological innovation systems: A scheme of analysis. Res. Policy 2008, 37, 407–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, B.; Stankiewicz, R. On the nature, function and composition of technological systems. J. Evol. Econ. 1991, 1, 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F. W. Technological Transitions and System Innovations: A Co-Evolutionary and Socio-Technical Analysis. (Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, 2005).

- Devaney, L.; Henchion, M. Consensus, caveats and conditions: International learnings for bioeconomy development. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 1400–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekkert, M.; Suurs, R.; Negro, S.; Kuhlmann, S.; Smits, R. Functions of innovation systems: A new approach for analysing technological change. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2007, 74, 413–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenen, L.; López, F.J.D. Comparing systems approaches to innovation and technological change for sustainable and competitive economies: an explorative study into conceptual commonalities, differences and complementarities. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, K.; Hermans, F. Innovation in the bioeconomy: Perspectives of entrepreneurs on relevant framework conditions. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 314, 127979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilden, R.; Gudergan, S.P. The impact of dynamic capabilities on operational marketing and technological capabilities: investigating the role of environmental turbulence. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundvall, B. National Systems of Innovation: Towards a Theorem of Innovation and Interactive Learning. (Pinter, London, 1992).

- Carlsson, B. Technological System and Economic Performance: A Case of Factory Automation. (Kluwer Academic, Dordrecht, 1995).

- Edquist, C. Systems of Innovation: Technologies, Institutions and Organizations. 1997.

- Cunningham, J.A.; O’reilly, P. Macro, meso and micro perspectives of technology transfer. J. Technol. Transf. 2018, 43, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Barth, T.D.; Campbell, D.F. The Quintuple Helix innovation model: global warming as a challenge and driver for innovation. J. Innov. Entrep. 2012, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, E.; Williams, M.D.; Davies, G.H. Recipes for success: Conditions for knowledge transfer across open innovation ecosystems. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 49, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-C.; Chen, M.-H. Comparing approaches to systems of innovation: the knowledge perspective. Technol. Soc. 2004, 26, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploum, L.; Blok, V.; Lans, T.; Omta, O. Exploring the relation between individual moral antecedents and entrepreneurial opportunity recognition for sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 1582–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-García, C.; González-Moreno, A.; Sáez-Martíínez, F.J. Eco-innovation: insights from a literature review. Innovation 2015, 17, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, V. , Rosenbusch, N. & Bausch, A. Success Patterns of Exploratory and Exploitative Innovation: A Meta-Analysis of the Influence of Institutional Factors. J Manage 39, 1606–1636 (2013).

- Yitshaki, R.; Kropp, F. Motivations and Opportunity Recognition of Social Entrepreneurs. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 54, 546–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iddris, F. Innovation Capability: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. Interdiscip. J. Information, Knowledge, Manag. 2016, 11, 235–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mision de Sabios por Caldas. MISIÓN DE SABIOS POR CALDAS: Equitativa, Productiva y Sostenible. Conocimiento Para El Desarrollo. (2020).

- Biotechnology Cluster. Tema: Primera plenaria Cluster del Conocimiento en biotecnología. (2019).

- Arksey, H and Knight, P. Why interviews? Interviewing for social scientists:an introductory resource with examples 32–42 (1999).

- Smith, J. & Frith, J. Qualitative Data Analysis : the framework approach. Nurse Res 18, 52–63 (2011).

- Maggs-Rapport, F. ‘Best research practice’: In pursuit of methodological rigour. J Adv Nurs 35, 373–383 (2001).

- Grillitsch, M. & Trippl, M. Innovation Policies and New Regional Growth Paths. in Innovation Systems, Policy and Management (ed. Niosi, J.) 329–358 (Cambridge University Press, New York, 2018). [CrossRef]

- Lühmann, M. Whose European bioeconomy? Relations of forces in the shaping of an updated EU bioeconomy strategy. Environ. Dev. 2020, 35, 100547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezama, A.; Ingrao, C.; O’keeffe, S.; Thrän, D. Resources, Collaborators, and Neighbors: The Three-Pronged Challenge in the Implementation of Bioeconomy Regions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaksen, A.; Jakobsen, S.-E.; Njøs, R.; Normann, R. Regional industrial restructuring resulting from individual and system agency. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2018, 32, 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labory, S.; Bianchi, P. Regional industrial policy in times of big disruption: building dynamic capabilities in regions. Reg. Stud. 2021, 55, 1829–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkart, S.; Díaz, M.; Enciso, K.; Charry, A.; Triana, N.; Mena, M.; Urrea-Benítez, J.L.; Caro, I.G.; Van der Hoek, R. The impact of COVID-19 on the sustainable intensification of forage-based beef and dairy value chains in Colombia: a blessing and a curse. Trop. Grasslands - Forrajes Trop. 2022, 10, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J. & Vredenburg, H. The challenges of innovating for sustainable development. Sloan Manage Rev 45, 61–68 (2003).

- nbsp; Bastos Lima, M. G. Corporate Power in the Bioeconomy Transition: The Policies and Politics of Conservative Ecological Modernization in Brazil. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschma, R. Relatedness as driver of regional diversification: a research agenda. Reg. Stud. 2017, 51, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tani, M.; Papaluca, O.; Sasso, P. The System Thinking Perspective in the Open-Innovation Research: A Systematic Review. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2018, 4, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchaut, B.; de Vriend, H.; Asveld, L. Uncertainties and uncertain risks of emerging biotechnology applications: A social learning workshop for stakeholder communication. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 946526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purkus, A.; Lüdtke, J. A systemic evaluation framework for a multi-actor, forest-based bioeconomy governance process: The German Charter for Wood 2.0 as a case study. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 113, 102113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, S.R. Innovation Perspectives for the Bioeconomy of Non-Timber Forest Products in Brazil. Forests 2022, 13, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kröger, M. Inter-sectoral determinants of forest policy: the power of deforesting actors in post-2012 Brazil. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 77, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackfort, S. Unlocking sustainability? The power of corporate lock-ins and how they shape digital agriculture in Germany. J. Rural. Stud. 2023, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thazin Aung, M. , Nguyen, H. & Denduang, B. Power and Influence in the Development of Thailand’s Bioeconomy. A Critical Stakeholder Analysis. Stockholm Environment Institute (2020).

- Backhouse, M.; Lehmann, R. New ‘renewable’ frontiers: contested palm oil plantations and wind energy projects in Brazil and Mexico. J. Land Use Sci. 2020, 15, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larner, W. & Walters, W. Global Governmentality. Governing International Spaces. (Routledge, London, New York, 2004).

| Sector | Division Name | Percentage % |

|---|---|---|

| Public | Departmental Government of Caldas | 8 |

| Secretary of Technology TIC's | ||

| Academy | University of Manizales | 25 |

| University of Caldas | ||

| Autonomous University of Manizales | ||

| National University of Colombia | ||

| Catholic University of Manizales | ||

| Luis Amigo University | ||

| National Learning Service SENA - SENNOVA | ||

| Research | Research Center CINDE | 25 |

| Environmental Studies Institute | ||

| Biotechnological Development Center "BIOS" | ||

| Economies Research Center "CRECE" | ||

| Research Center of Coffee "Cenicafé" | ||

| Biotechnology and Agroindustry Institute - UNAL | ||

| Bioprocess Plant of Caldas University | ||

| Business Chambers | Chamber of commerce | 25 |

| Program "Manizales como vamos" | ||

| Hydroelectric Caldas Company | ||

| Manizales Water Company | ||

| National Association of Industries "ANDI" | ||

| University - Company - State Foundation FUEEC | ||

| Inter Union Committee of Caldas | ||

| Agribusiness | Comité de Cafeteros de Caldas | 3 |

| Environment | "Vivo Cuenca" Corporation" | 7 |

| Environmental Authority Corpocaldas | ||

| Entrepreneurship | Organization of entrepreunership "Incubar" | 7 |

| Entrepeunership Center "Manizales +" |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).