Submitted:

03 November 2024

Posted:

05 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

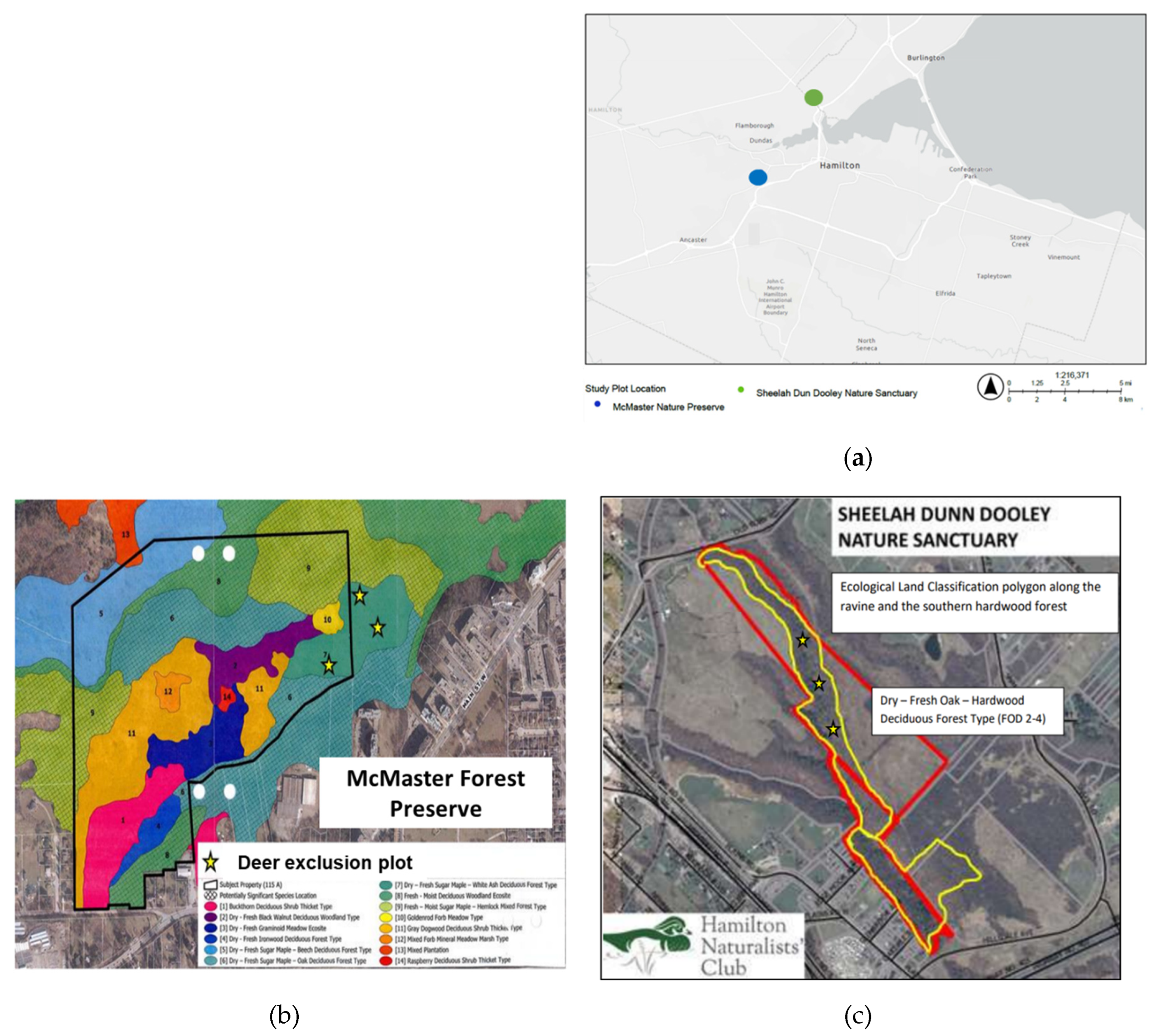

2.1. Project Site Description

2.2. Experimental Design & Data Collection

2.2.1. Deer Exclusion Study

2.2.2. Tip-up Mound Study

2.3. Determination of Soil Organic Matter

2.4. Soil Nitrate and Phosphate Determination

2.5. Vegetation Data

2.6. Statistical Analysis and Modelling

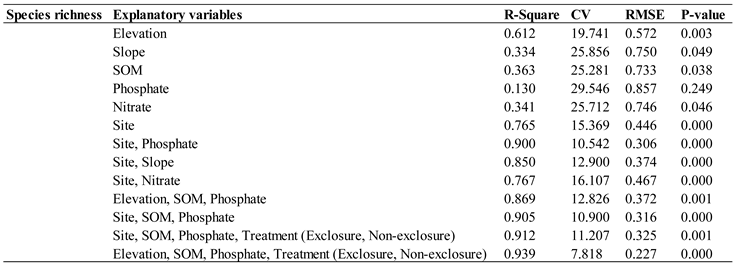

3. Results

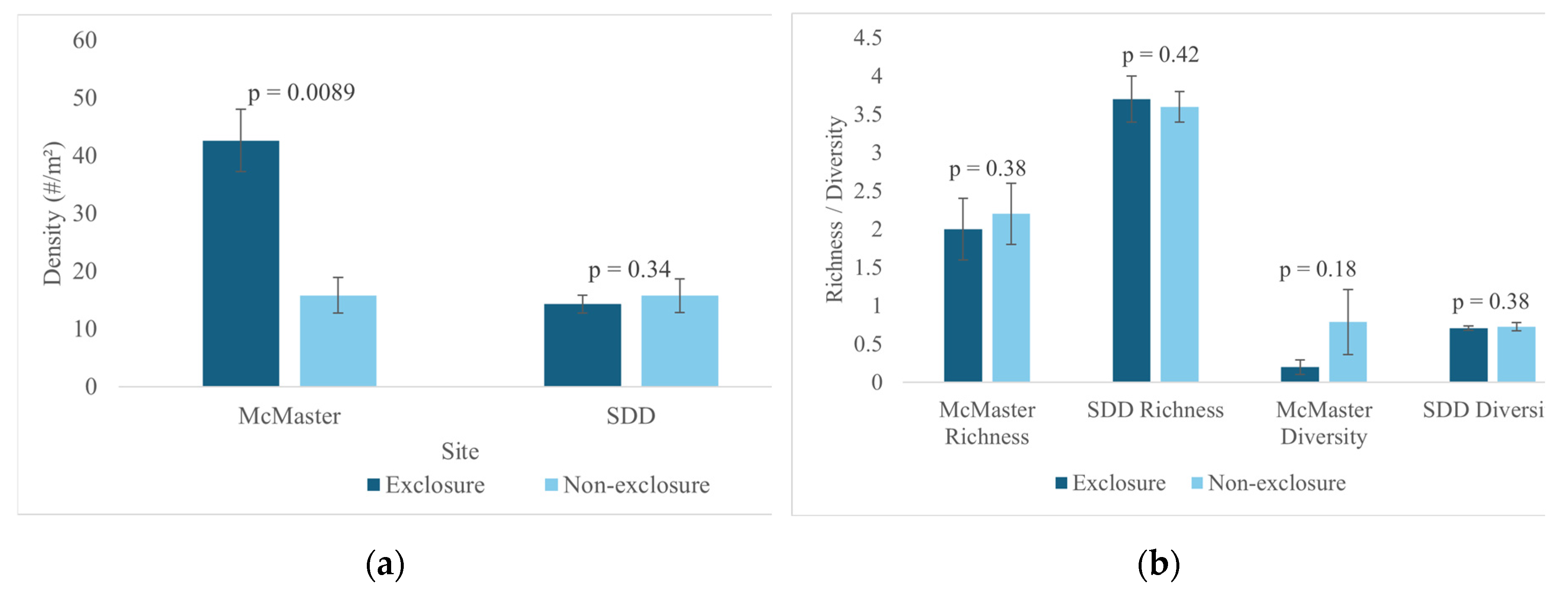

3.1. Impact of Deer Browsing on Abundance and Diversity

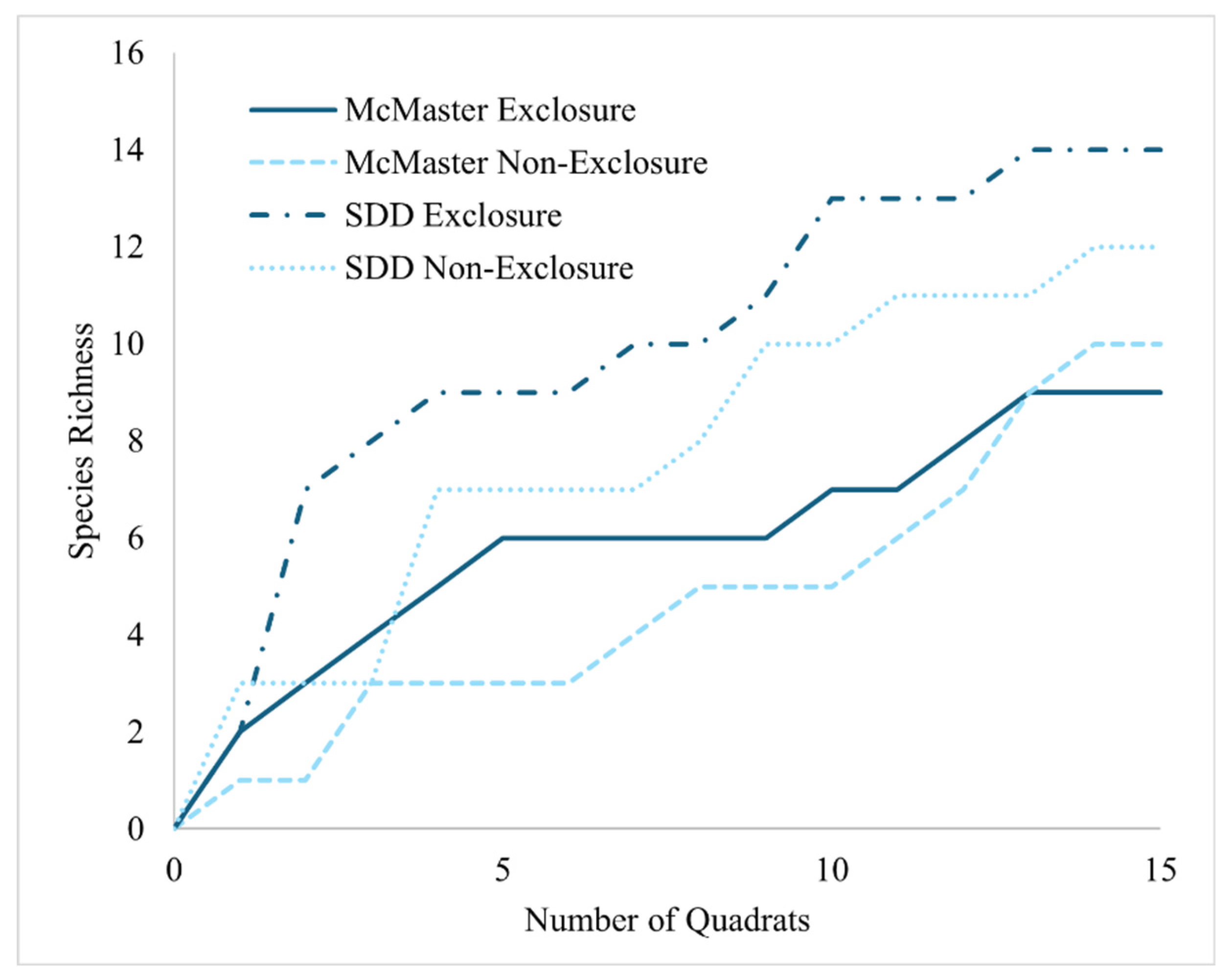

3.1.1. Seedling Density, Species Richness and Diversity

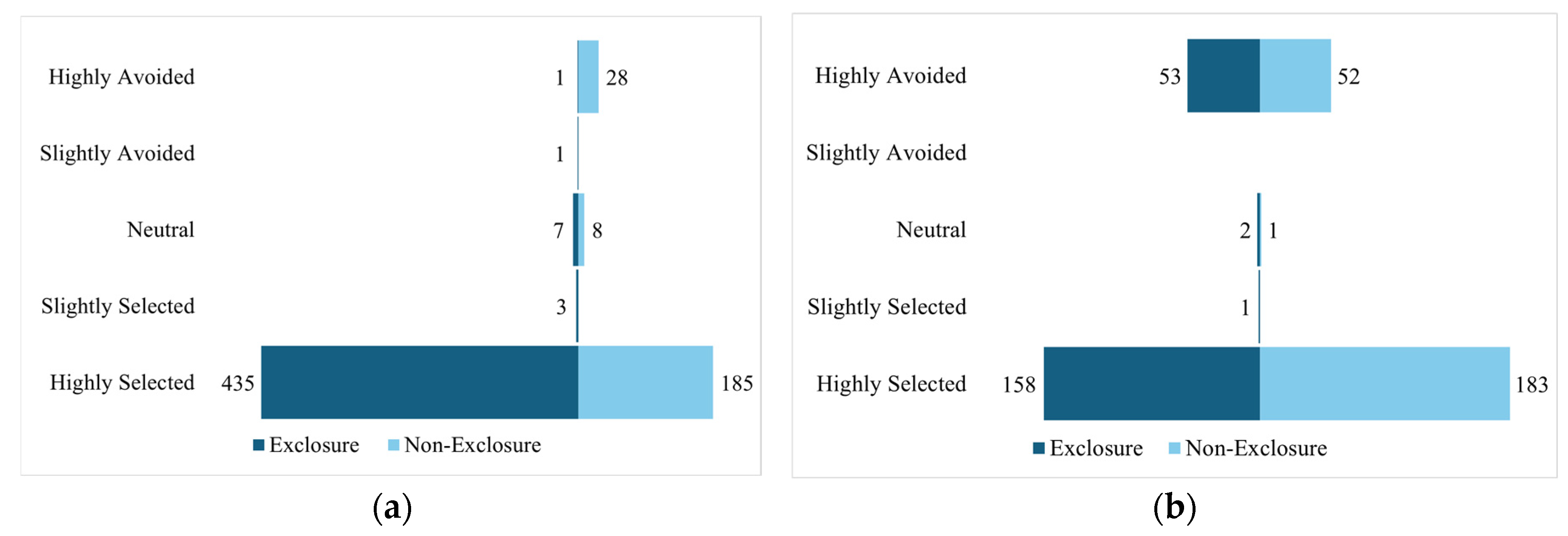

3.1.2. Abundance of Deer-Preferred Species

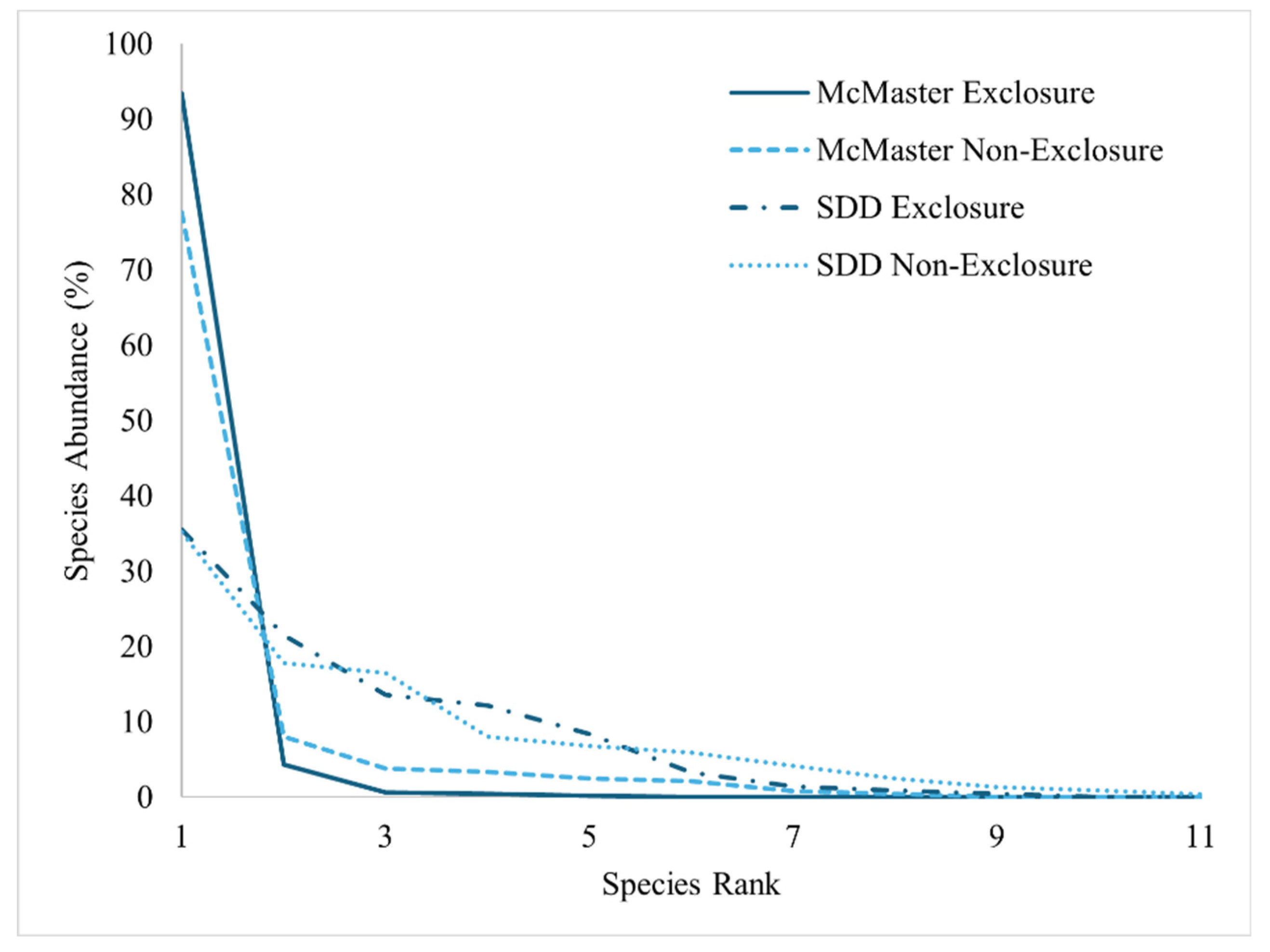

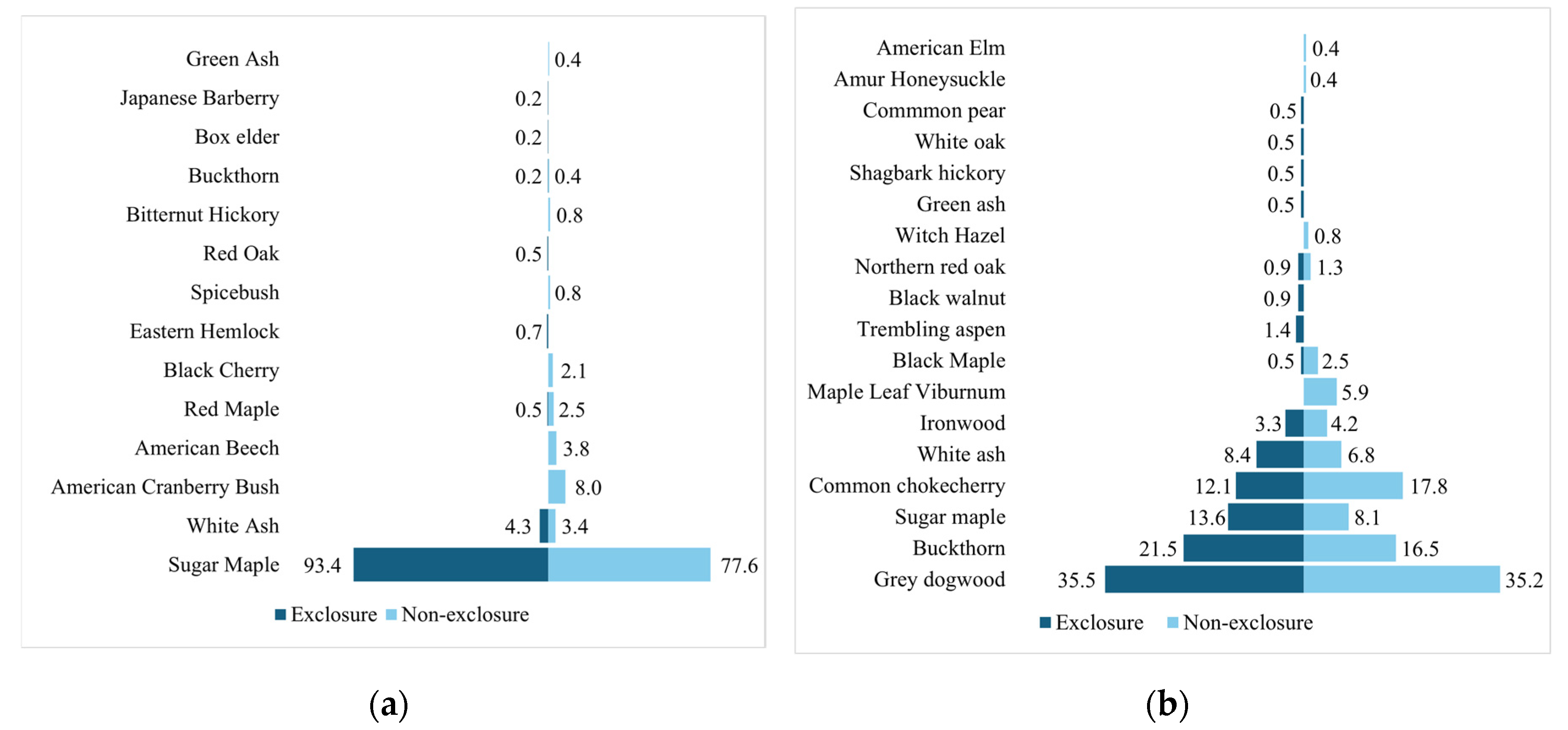

3.1.3. Species Dominance

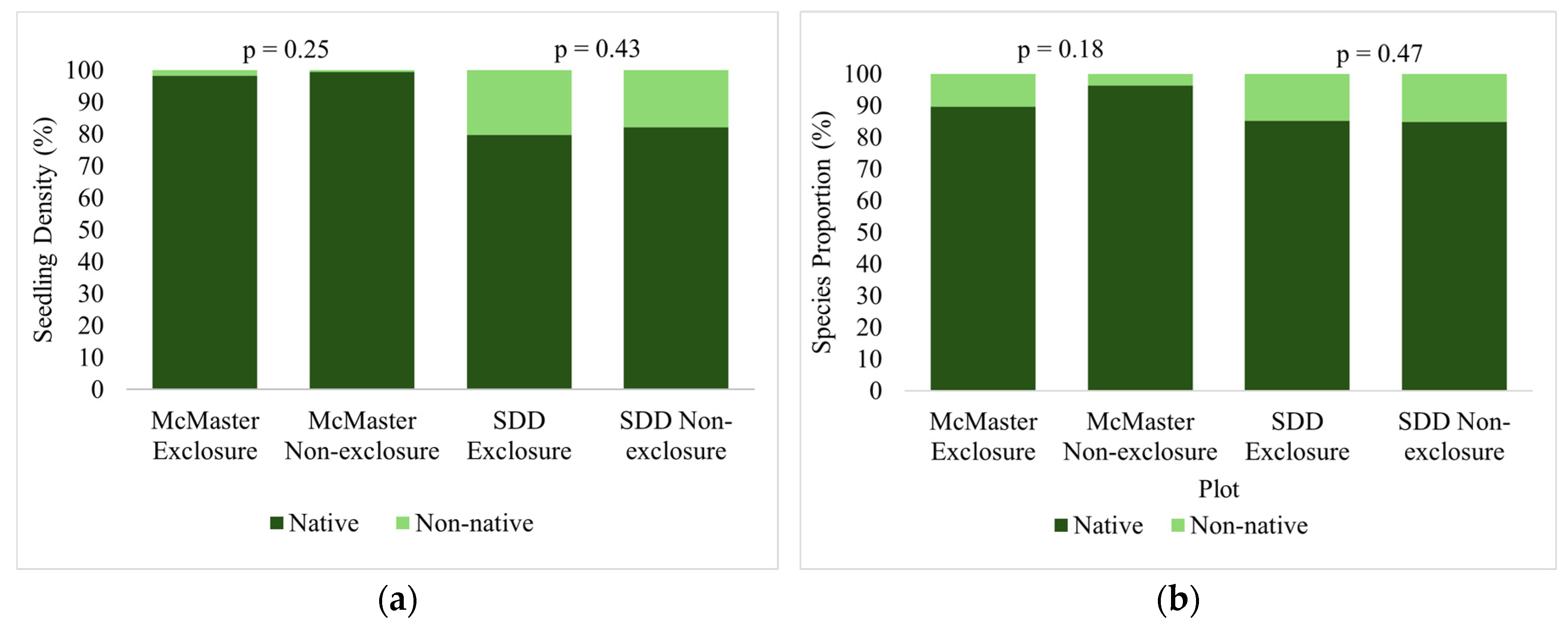

3.2. Impact of Deer Browsing on Species Invasion

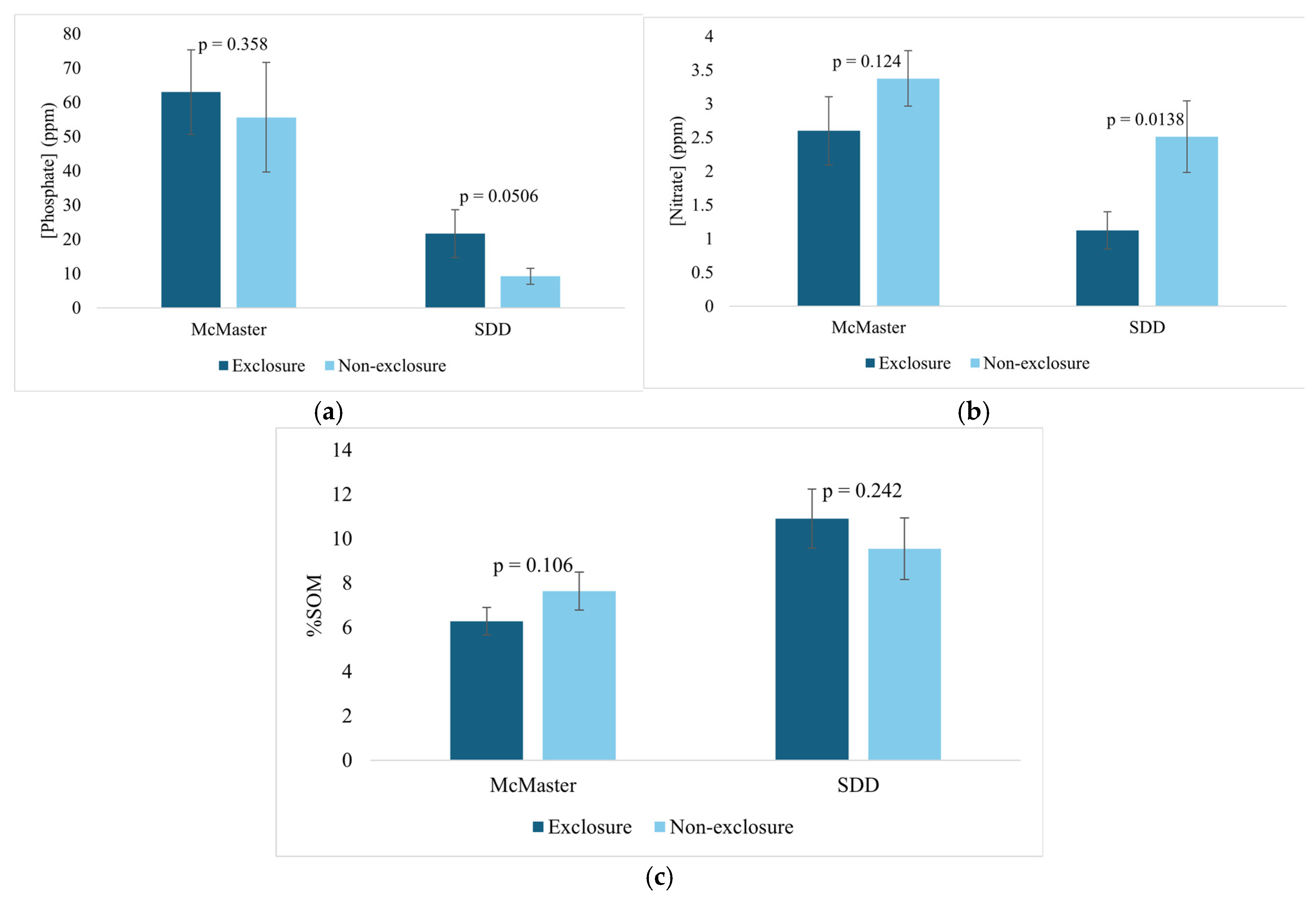

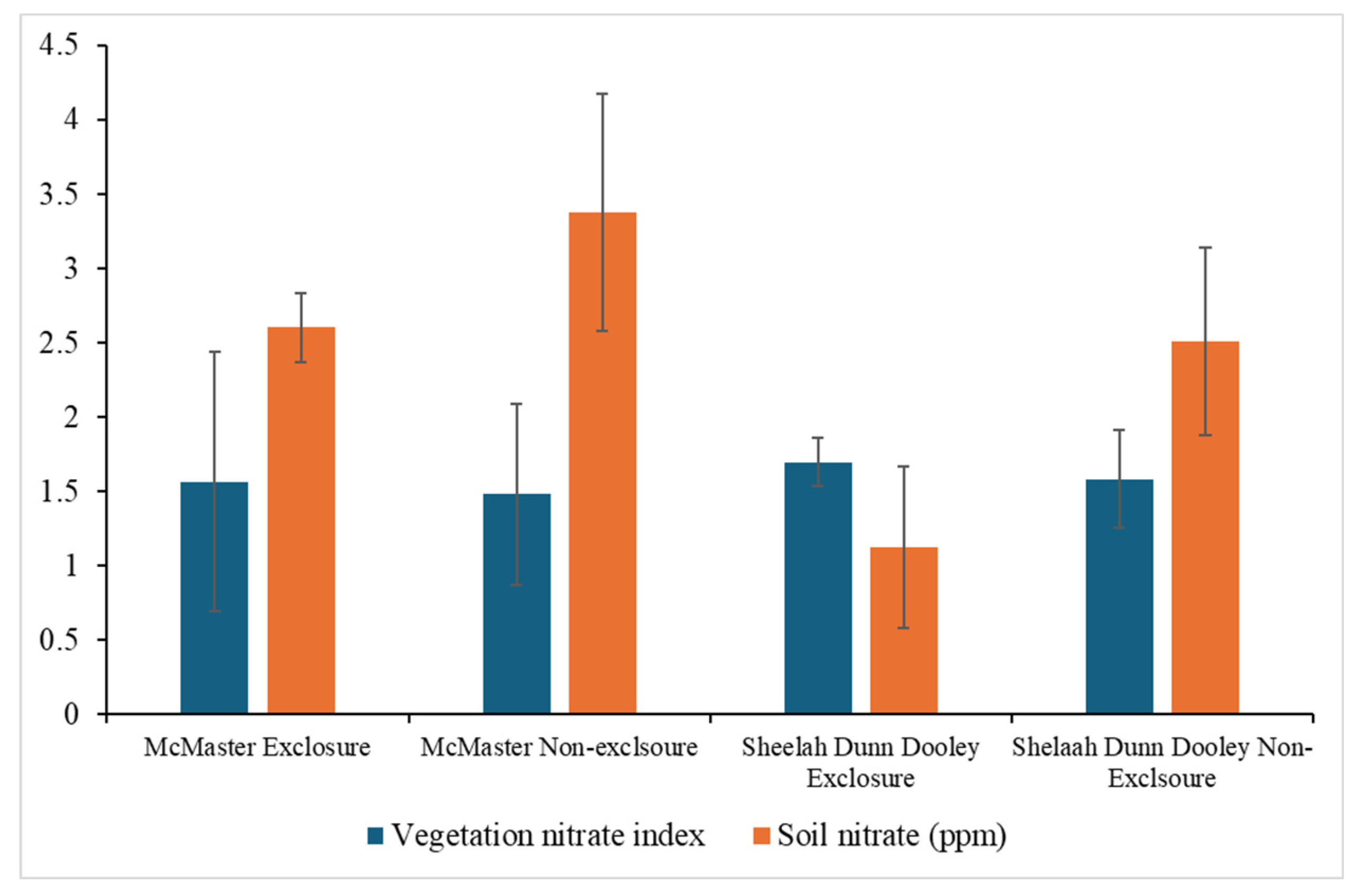

3.3. Impact of Deer Browsing on Nutrient Cycling

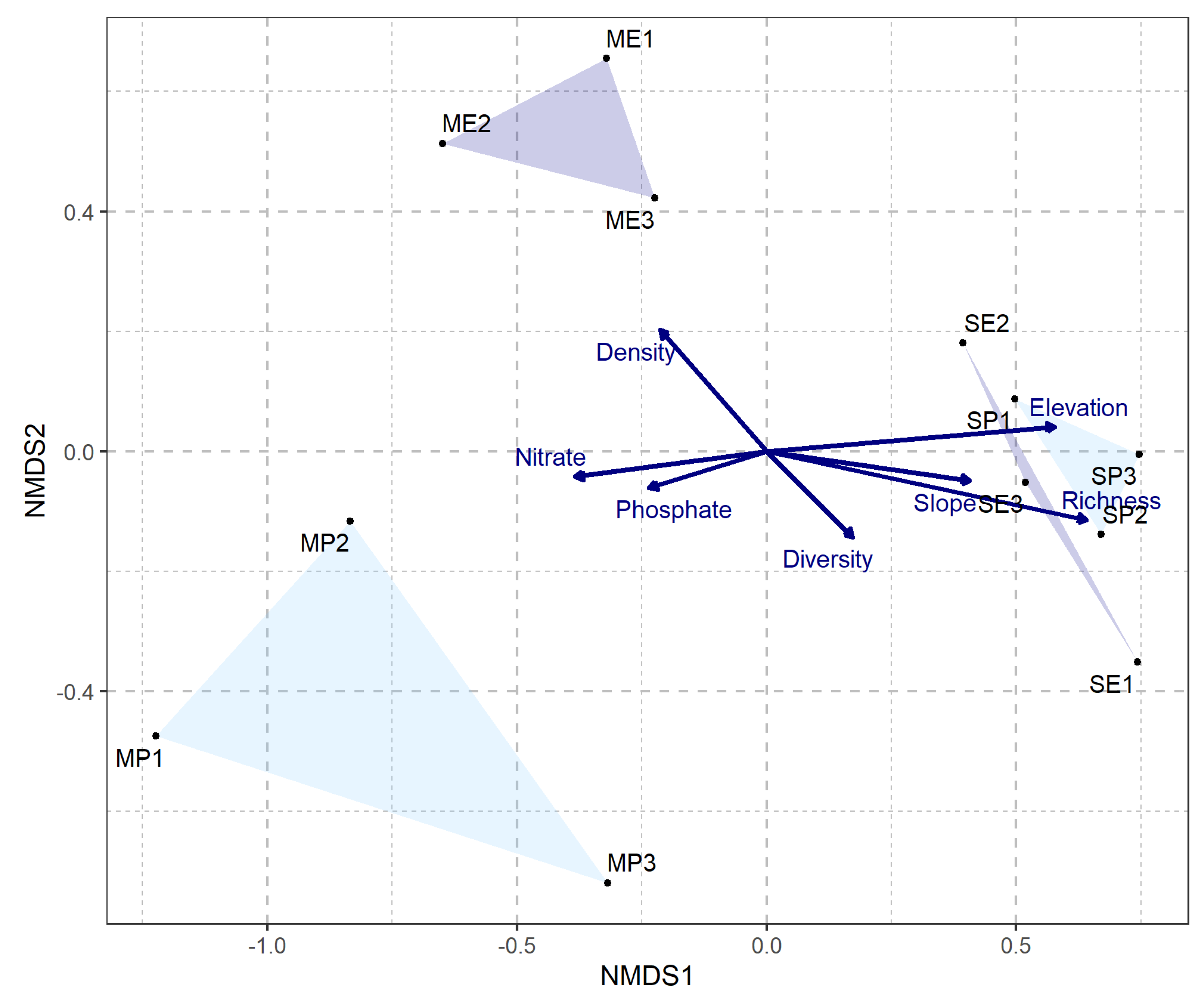

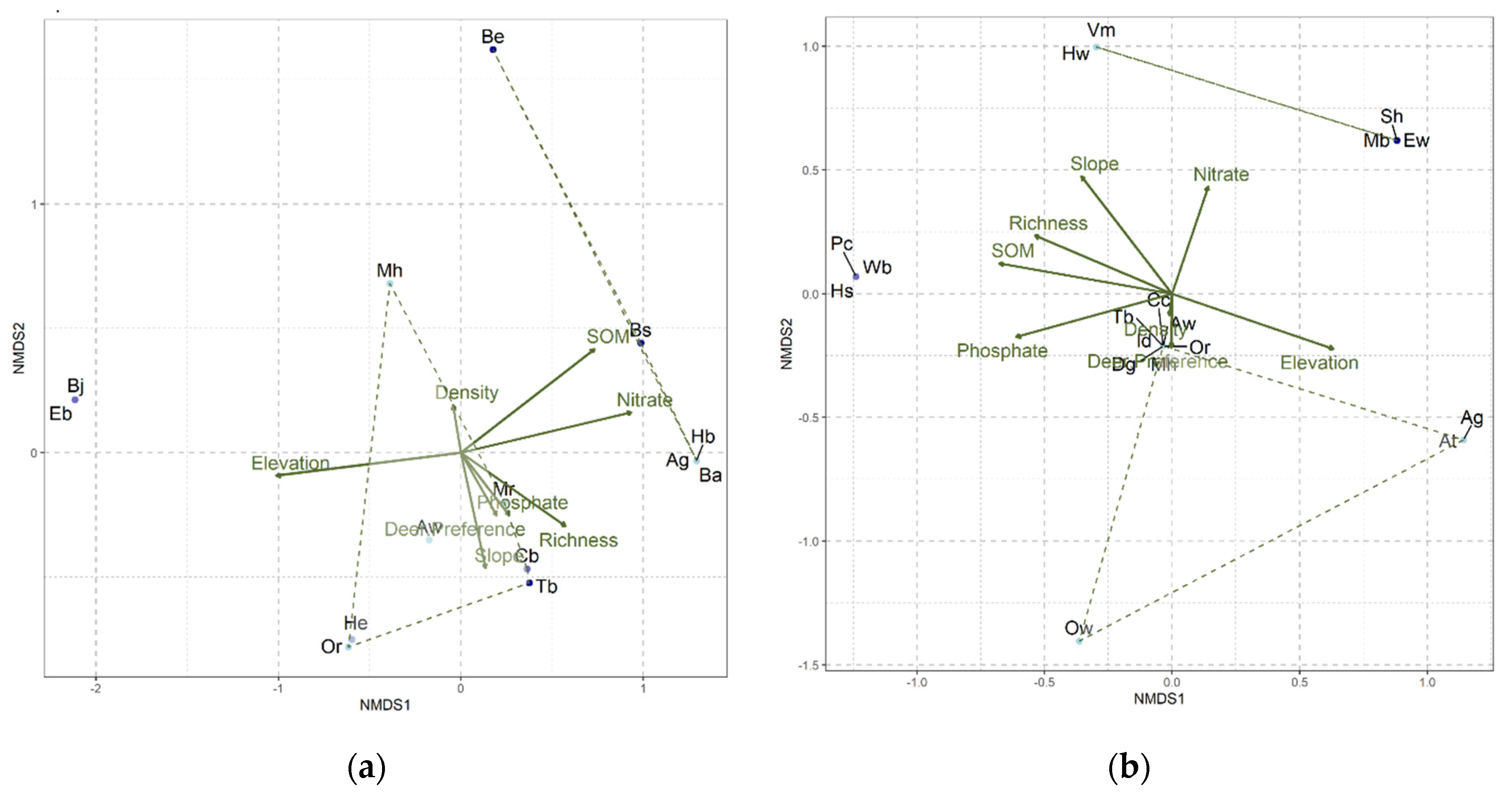

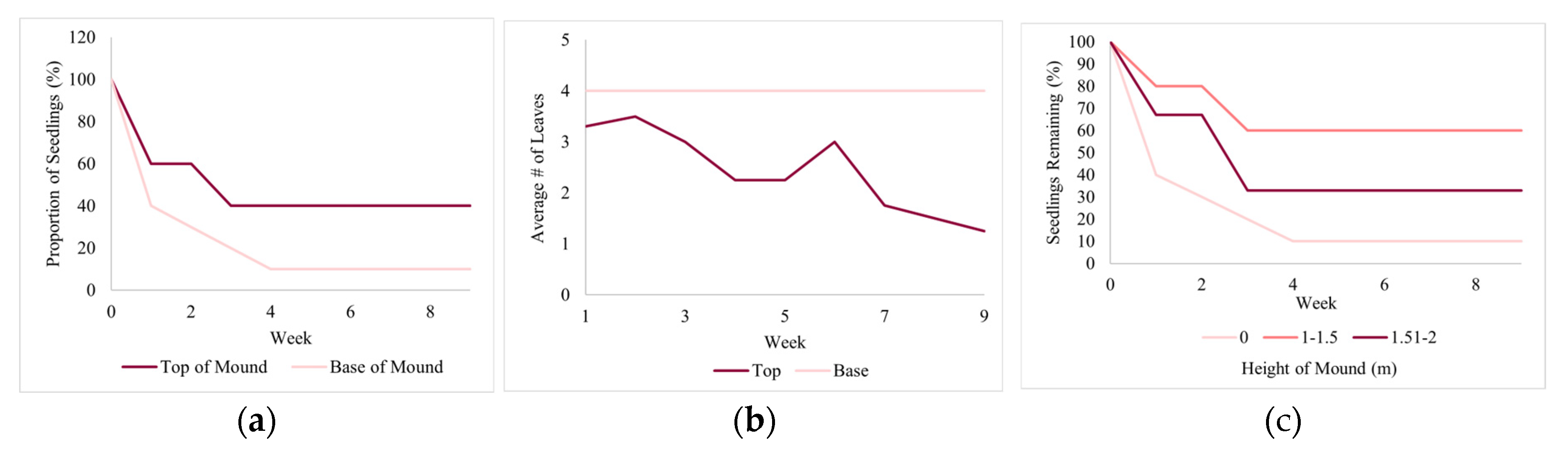

3.4. Impact of Tip-Up Mounds on Deer Browsing Activity

4. Discussion

4.1. Inter-Site Differences in Regeneration Dynamics and Nutrient Cycling

4.2. Impact of Deer Browsing on Seedlings

4.3. Impact of Deer Browsing on Nutrient Cycling

4.4. Impact of Tip-Up Mounds on Deer Browsing Activity

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Perry, D. A., Oren, R., & Hart, S. C. (2008). Forest Ecosystems (2nd ed.). JHU Press.

- Johnson, D. W., & Turner, J. (2019). Tamm Review: Nutrient cycling in forests: A historical look and newer developments. Forest Ecology and Management, 444, 344–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2019.04.052. [CrossRef]

- Kraus, D., & Krumm, F. (2013). Integrative approaches as an opportunity for the conservation of forest biodiversity. European Forest Institute. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263580500_Integrative_Approaches_as_an_Opportunity_for_the_Conservation_of_Forest_Biodiversity.

- Ampoorter, E., Barbaro, L., Jactel, H., Baeten, L., Boberg, J., Carnol, M., Castagneyrol, B., Charbonnier, Y., Dawud, S. M., Deconchat, M., Smedt, P. D., Wandeler, H. D., Guyot, V., Hättenschwiler, S., Joly, F.-X., Koricheva, J., Milligan, H., Muys, B., Nguyen, D., Allan, E. (2020). Tree diversity is key for promoting the diversity and abundance of forest-associated taxa in Europe. Oikos, 129(2), 133–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/oik.06290. [CrossRef]

- Jactel, H., Bauhus, J., Boberg, J., Bonal, D., Castagneyrol, B., Gardiner, B., Gonzalez-Olabarria, J. R., Koricheva, J., Meurisse, N., & Brockerhoff, E. G. (2017). Tree diversity drives forest stand resistance to natural disturbances. Current Forestry Reports, 3(3), 223–243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40725-017-0064-1. [CrossRef]

- Kozlowski, T. T. (2002). Physiological ecology of natural regeneration of harvested and disturbed forest stands: Implications for forest management. Forest Ecology and Management, 158(1), 195–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1127(00)00712-X. [CrossRef]

- Harmer, R. (2001). The effect of plant competition and simulated summer browsing by deer on tree regeneration. Journal of Applied Ecology, 38(5), 1094–1103. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2664.2001.00664.x. [CrossRef]

- Laurent, L., Mårell, A., Balandier, P., Holveck, H., & Saïd, S. (2017). Understory vegetation dynamics and tree regeneration as affected by deer herbivory in temperate hardwood forests. iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, 10(5), 837. https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor2186-010. [CrossRef]

- De Lombaerde, E., Verheyen, K., Van Calster, H., & Baeten, L. (2019). Tree regeneration responds more to shade casting by the overstorey and competition in the understorey than to abundance per se. Forest Ecology and Management, 450, 117492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2019.117492. [CrossRef]

- Patton, S. R., Russell, M. B., Windmuller-Campione, M. A., & Frelich, L. E. (2021). White-tailed deer herbivory impacts on tree seedling and sapling abundance in the Lake States Region of the USA. Annals of Forest Science, 78(4), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-021-01108-6.

- Krueger, L. M., Peterson, C. J., Royo, A., & Carson, W. P. (2009). Evaluating relationships among tree growth rate, shade tolerance, and browse tolerance following disturbance in an eastern deciduous forest. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 39(12), 2460–2469. https://doi.org/10.1139/X09-155. [CrossRef]

- Nuttle, T., Royo, A. A., Adams, M. B., & Carson, W. P. (2013). Historic disturbance regimes promote tree diversity only under low browsing regimes in eastern deciduous forest. Ecological Monographs, 83(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1890/11-2263.1. [CrossRef]

- Nuttle, T., Ristau, T. E., & Royo, A. A. (2014). Long-term biological legacies of herbivore density in a landscape-scale experiment: Forest understoreys reflect past deer density treatments for at least 20 years. Journal of Ecology, 102(1), 221–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.12175. [CrossRef]

- Waller, D. M., & Maas, L. I. (2013). Do white-tailed deer and the exotic plant garlic mustard interact to affect the growth and persistence of native forest plants? Forest Ecology and Management, 304, 296–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2013.05.011. [CrossRef]

- Belovsky, G. E., & Slade, J. B. (2000). Insect herbivory accelerates nutrient cycling and increases plant production. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 97(26), 14412–14417. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.250483797. [CrossRef]

- Woods, M. J., Roberson, E., Cipollini, D., & Rúa, M. A. (2019). White-tailed deer and an invasive shrub facilitate faster carbon cycling in a forest ecosystem. Forest Ecology and Management, 448, 104–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2019.05.068. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, K. A., & Bardgett, R. D. (2004). Browsing by red deer negatively impacts on soil nitrogen availability in regenerating native forest. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 36(1), 115–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2003.08.022. [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, B. E., Rodgers, V. L., Stinson, K. A., & Pringle, A. (2008). The invasive plant Alliaria petiolata (garlic mustard) inhibits ectomycorrhizal fungi in its introduced range. Journal of Ecology, 96(4), 777–783. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2745.2008.01389.x. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, I. C., & Cairney, J. W. G. (2007). Ectomycorrhizal fungi: exploring the mycelial frontier. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 31(4), 388–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00073.x. [CrossRef]

- Fagan, M. E., & Peart, D. R. (2004). Impact of the invasive shrub glossy buckthorn (Rhamnus frangula L.) on juvenile recruitment by canopy trees. Forest Ecology and Management, 194(1), 95–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2004.02.015. [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.L., Decker, D.J., Riley, S.J., Enck, J.W., Lauber, T.B., Curtis, P.D. and Mattfeld, G.F., 2000. The future of hunting as a mechanism to control white-tailed deer populations. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 28(4), pp.797-807.

- Ballard, W., Lutz, D., Keegan, T., Carpenter, L., & deVos, J. (2001). Deer-predator relationships: A review of recent North American studies with emphasis on mule and black-tailed deer. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 29(1). Deer-predator relationships: A review of recent North American studies with emphasis on mule and black-tailed deer | Request PDF (researchgate.net).

- Long, Z. T., Carson, W. P., & Peterson, C. J. (1998). Can disturbance create refugia from herbivores: An example with hemlock regeneration on treefall mounds. Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society, 125, 165–168. https://doi.org/10.2307/2997303. [CrossRef]

- Titus, J. H. (1990). Microtopography and woody plant regeneration in a hardwood floodplain swamp in Florida. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club, 117(4), 429–437. https://doi.org/10.2307/2996840. [CrossRef]

- Bartlick, C. I., Burton, J. I., Webster, C. R., Froese, R. E., Hupperts, S. F., & Dickinson, Y. L. (2023). Artificial tip-up mounds influence tree seedling composition in a managed northern hardwood forest. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 53(11), 893–904. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjfr-2022-0252. [CrossRef]

- Tidman, D., & Hsiang, T. (2021). Restoring forest cover and enhancing biodiversity of the Carolinian forest in Ontario affected by Ash tree decline from the Emerald Ash Borer. https://hdl.handle.net/10214/24139.

- DeYoung, B., & Troughton, M. (2005). Sharp pencils, fat crayons and fuzzy boundaries: How to depict the Carolinian in Canada. Protected Areas and Species and Ecosystems at Risk: Research and Planning Challenged. Proceedings of the Parks Reserach Forum of Ontario (PFRO) Annual General Meeting. https://longpointbiosphere.com/download/Environment/PRFO-2005-Proceedings-p413-422-DeYoung-and-Troughton.pdf.

- Public Safety Canada 2020. Canadian Disaster Database. https://cdd.publicsafety.gc.ca/prnt-eng.aspx?cultureCode=en-Ca&provinces=9&eventTypes=%27EP%27%2C%27IN%27%2C%27PA%27%2C%27AV%27%2C%27CE%27%2C%27DR%27%2C%27FL%27%2C%27GS%27%2C%27HE%27%2C%27HU%27%2C%27SO%27%2C%27SS%27%2C%27ST%27%2C%27TO%27%2C%27WF%27%2C%27SW%27%2C%27EQ%27%2C%27LS%27%2C%27TS%27%2C%27VO%27&normalizedCostYear=1&dynamic=false. Last accessed on July 28, 2024.

- Hamilton Naturalist’s Club (2024). Sheelah Dunn Dooley Nature Sanctuary Stewardship Plan. https://mail.google.com/mail/u/0?ui=2&ik=0cb42d64be&attid=0.2&permmsgid=msg-f:1797325289225623768&th=18f161d3f21e98d8&view=att&disp=inline&realattid=f_lvfga0nh2.

- HCA (Hamilton Conservation Authority) 2013. White-tailed Deer Annual Report, 2013. https://conservationhamilton.ca/images/PDFs/Board%20of%20Directors/Appendix_A_-_2013_Deer_Report.pdf.

- Barker, J., 2018. Effects of white-tailed deer and invasive garlic mustard on native tree seedlings in an urban forest. MSc dissertation. https://macsphere.mcmaster.ca/handle/11375/24171.

- Stephan, J. G., Pourazari, F., Tattersdill, K., Kobayashi, T., Nishizawa, K., & De Long, J. R. (2017). Long-term deer exclosure alters soil properties, plant traits, understory plant community and insect herbivory, but not the functional relationships among them. Oecologia, 184(3), 685–699. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-017-3895-3. [CrossRef]

- Kershaw, L. 2001. Trees of Ontario. Lone Pine Publishing. 240 pages.

- Anyomi, K., 2023. How consistent are citizen science data sources, an exploratory study using free automated image recognition apps for woody plant identification. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 54(3), pp.357-365.

- Hoogsteen, M., Lantinga, E., Bakker, E.-J., Groot, J., & Tittonell, P. A. (2015). Estimating soil organic carbon through loss on ignition: Effects of ignition conditions and structural water loss. European Journal of Soil Science, 66. https://doi.org/10.4141/S05-070. [CrossRef]

- Pellerin, A., Parent, L.-É., Fortin, J., Tremblay, C., Khiari, L., & Giroux, M. (2006). Environmental Mehlich-III soil phosphorus saturation indices for Quebec acid to near neutral mineral soils varying in texture and genesis. Canadian Journal of Soil Science, 86(4), 711–723. https://doi.org/10.4141/S05-070. [CrossRef]

- Berkelaar, E. (2023). ENV 222: Environmental Science II: Pollution and Climate Change Unpublished laboratory manual.

- OMNR (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources) 2024. The tree atlas: Southwest region. https://www.ontario.ca/page/tree-atlas/ontario-southwest. Last accessed July 3rd 2024.

- Muma, W. 2014. Ontario trees and shrubs. https://ontariotrees.com/main/index.php. Last accessed on June 28, 2024.

- USDA (United States Department of Agriculture) 2014. USDA Plants Database. https://plants.usda.gov/home. Last accessed June 28, 2024.

- Sample, R. D., Delisle, Z. J., Pierce, J. M., Swihart, R. K., Caudell, J. N., & Jenkins, M. A. (2023). Selection rankings of woody species for white-tailed deer vary with browse intensity and landscape context within the Central Hardwood Forest Region. Forest Ecology and Management, 537, 120969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2023.120969. [CrossRef]

- Ward, J. S., Williams, S. C., & Linske, M. A. (2018). Influence of invasive shrubs and deer browsing on regeneration in temperate deciduous forests. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 48(1), 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjfr-2017-0208. [CrossRef]

- Catling, P. M., & Mitrow, G. (2008). Distribution and History of Naturalized Common Pear, ‘Pyrus communis’, in Ontario. The Canadian Field-Naturalist, 122(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.22621/cfn.v122i1.544. [CrossRef]

- Nature’s Mace (2024). Do Deer Eat Walnut Trees? Nature’s Mace. https://naturesmace.com/blogs/blog/do-deer-eat-black-walnuts#:~:text=Black%20walnuts%20also%20make%20a,once%20the%20plants%20before%20woody. Last accessed July 3rd 2024.

- Scottish Forestry, n.d. Relative palatability and resilience of native trees. https://www.forestry.gov.scot/woodland-grazing-toolbox/grazing-management/foraging/palatability-and-resilience-of-native-trees. Last accessed on July 3, 2024.

- GardenTabs 2021. Are Dogwood Trees Deer Resistant? GardenTabs. https://gardentabs.com/are-dogwood-trees-deer-resistant/. Last accessed on July 22, 2024.

- Midwest Gardening 2017. Black Maple Trees. Midwest Gardening. https://www.midwestgardentips.com/trees-index-1/2017/12/8/black-maple-trees. Last accessed on July 22, 2024.

- Alverson, W.S., Lea, M.V. and Waller, D.M., 2019. A 20-year experiment on the effects of deer and hare on eastern hemlock regeneration. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 49(11), pp.1329-1338.

- NCSU (North Carolina State University) 2024. The North Carolina extension gardener plant toolbox. https://plants.ces.ncsu.edu/. Last accessed July 3rd 2024.

- The Spruce (n.d.). How to Grow and Care for Japanese Barberry. The Spruce. https://www.thespruce.com/japanese-barberry-shrubs-2132250. Last accessed on July 22, 2024.

- Nolan, J., & Expert, G. (2022). Boxelder trees: Types, leaves, bark, fruit (with pictures) - Identification guide. Leafy Place. https://leafyplace.com/boxelder-trees/.

- The Plant Native (2023). A guide to planting spicebush. The Plant Native. https://theplantnative.com/plant/spicebush/. Last accessed on July 22, 2024.

- Whitlock, M. & Schluter, D., 2015. The analysis of biological data (Vol. 768). Greenwood Village, Colorado: Roberts Publisher.

- Dexter, E., Rollwagen-Bollens, G., & Bollens, S. M. (2018). The trouble with stress: A flexible method for the evaluation of nonmetric multidimensional scaling. Limnology and Oceanography: Methods, 16(7), 434–443. https://doi.org/10.1002/lom3.10257. [CrossRef]

- Magee, L., Wolf, A., Howe, R., Schubbe, J., Hagenow, K., & Turner, B. (2021). Density dependence and habitat heterogeneity regulate seedling survival in a North American temperate forest. Forest Ecology and Management, 480, 118722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2020.118722. [CrossRef]

- Munoz, S. (2016). Forest diversity across space and environmental gradients. McMaster University, 111. https://dsp.lib.mcmaster.ca/bitstream/11375/19437/2/Munoz_Sophia_L_201605_MSc.pdf.

- Stegman, N., 2023. Temporal and Landscape Influences on the Bee Community Assemblage of the McMaster Research and Conservation Corridor. MSc dissertation. https://macsphere.mcmaster.ca/handle/11375/28274.

- Deforest, J. L., Smemo, K. A., Burke, D. J., Elliott, H. L., & Becker, J. C. (2012). Soil microbial responses to elevated phosphorus and pH in acidic temperate deciduous forests. Biogeochemistry, 109(1–3), 189–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-011-9619-6. [CrossRef]

- Geng, X., Zuo, J., Meng, Y., Zhuge, Y., Zhu, P., Wu, N., Bai, X., Ni, G., & Hou, Y. (2023). Changes in nitrogen and phosphorus availability driven by secondary succession in temperate forests shape soil fungal communities and function. Ecology and Evolution, 13(10), e10593. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.10593. [CrossRef]

- TFI (The Fertilizer Institute) 2021. Soil Test Levels in North America, 2020 Summary Update. The Fertilizer Institute, Arlinton, VA 22203, USA.

- Alewell, C., Ringeval, B., Ballabio, C., Robinson, D. A., Panagos, P., & Borrelli, P. (2020). Global phosphorus shortage will be aggravated by soil erosion. Nature Communications, 11(1), 4546. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18326-7. [CrossRef]

- Li, S., Li, Y., Huang, X., Hu, F., Liu, X., & Li, H. (2018). Phosphate fertilizer enhancing soil erosion: Effects and mechanisms in a variably charged soil. Journal of Soils and Sediments, 18(3), 863–873. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-017-1794-1. [CrossRef]

- He, X., Zheng, Z., Li, T. and He, S., 2020. Effect of slope gradient on phosphorus loss from a sloping land of purple soil under simulated rainfall. Polish Journal of Environmental Studies, 29(2), pp.1637-1647.

- Wilsey, B., & Stirling, G. (2007). Species richness and evenness respond in a different manner to propagule density in developing prairie microcosm communities. Plant Ecology, 190(2), 259–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11258-006-9206-4. [CrossRef]

- Tanentzap, A. J., Burrows, L. E., Lee, W. G., Nugent, G., Maxwell, J. M., & Coomes, D. A. (2009). Landscape-level vegetation recovery from herbivory: Progress after four decades of invasive red deer control. Journal of Applied Ecology, 46(5), 1064–1072. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2009.01683.x. [CrossRef]

- Shen, X., Bourg, N. A., McShea, W. J., & Turner, B. L. (2016). Long-term effects of white-tailed deer exclusion on the invasion of exotic plants: A case study in a mid-atlantic temperate forest. PLOS ONE, 11(3), e0151825. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0151825. [CrossRef]

- Maillard, M., Martin, J.-L., Chollet, S., Catomeris, C., Simon, L., & Grayston, S. J. (2021). Belowground effects of deer in a temperate forest are time-dependent. Forest Ecology and Management, 493, 119228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2021.119228. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J., Wang, H., Li, G., Ma, W., Wu, J., Gong, Y., & Xu, G. (2020). Vegetation degradation impacts soil nutrients and enzyme activities in wet meadow on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 21271. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-78182-9. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).