Submitted:

01 November 2024

Posted:

05 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

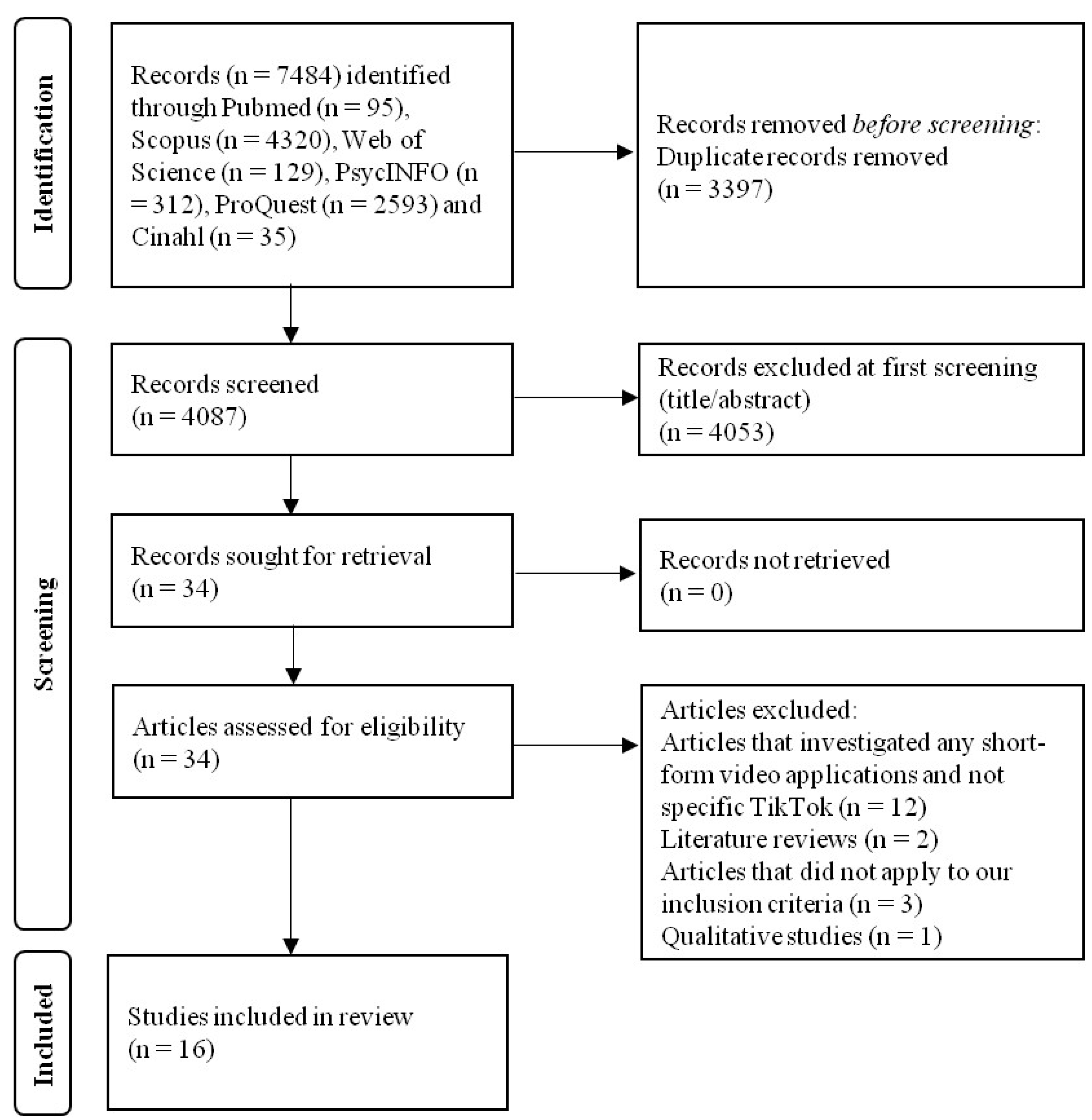

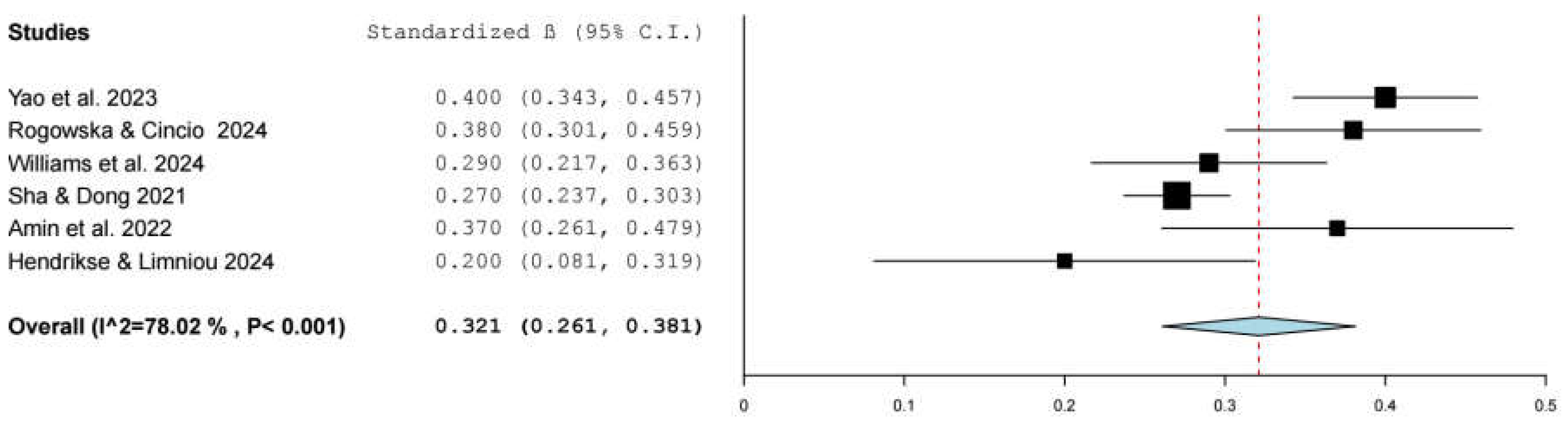

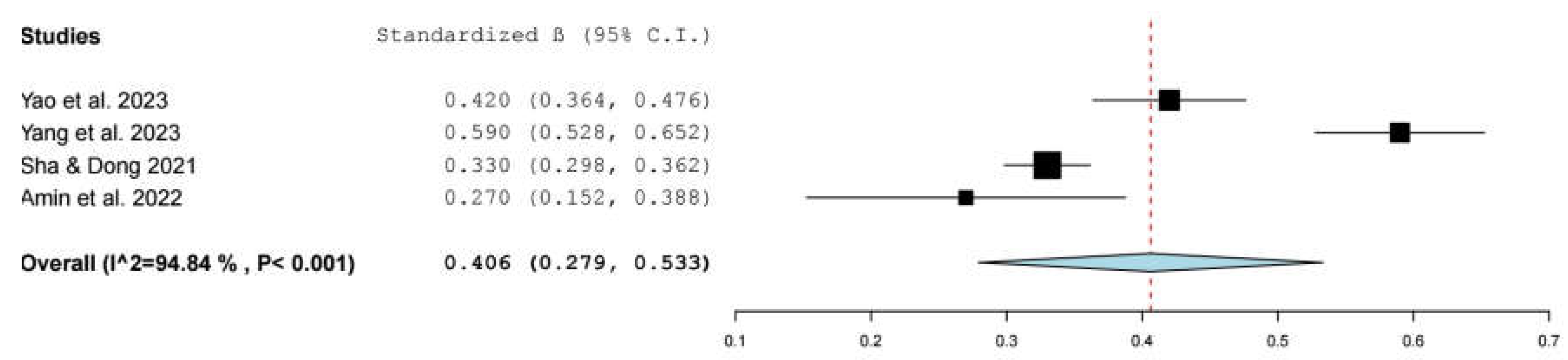

TikTok has rapidly become one of the most popular social media platforms, and, thus, scholars should pay attention to its association with users’ mental health. Our aim was to synthesize and evaluate the association between problematic TikTok use and mental health. We applied the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis guidelines in our review. The review protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42024582054). We searched PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, PsycINFO, ProQuest, and CINAHL until September 02, 2024. We identified 16 studies with 15,821 individuals. All studies were cross-sectional and were conducted after 2019. Our meta-analysis showed a statistically significant positive association between TikTok use and depression (β = 0.321, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.261 to 0.381, p < 0.001), and anxiety (β = 0.406, 95% CI: 0.279 to 0.533, p < 0.001). Also, we found a positive association between TikTok use and body image issues, poor sleep, anger, distress intolerance, narcissism, and stress. Our findings suggest that problematic TikTok use has a negative impact on several mental health issues. Given the high levels of TikTok use especially among young adults, our findings are essential to further enhance our understanding of the impact of TikTok use on mental health. Finally, there is a need for further studies of better quality to assess the impact of problematic TikTok use on mental health in a more valid way.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Strategy

2.2. Selection and Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Appraisal

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Identification and Selection of Studies

3.2. Characteristics of the Studies

3.3. Measurement Scales for TikTok Use and Mental Health Variables

3.4. Quality Assessment

3.5. Meta-Analysis

3.5.1. Depression

3.5.2. Anxiety

3.5.3. Other Mental Health Variables

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statista. Social Media & User-Generated Content. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/278414/number-of-worldwide-social-network-users/.

- Haenlein, M.; Anadol, E.; Farnsworth, T.; Hugo, H.; Hunichen, J.; Welte, D. Navigating the New Era of Influencer Marketing: How to Be Successful on Instagram, TikTok, & Co. California Management Review 2020, 63, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrouzo, S.; Krynski, L. Hyperconnected: Children and Adolescents on Social Media. The TikTok Phenomenon. Arch Argent Pediat 2023, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montag, C.; Yang, H.; Elhai, J.D. On the Psychology of TikTok Use: A First Glimpse From Empirical Findings. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 641673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbouyi, S.; Bouazza, S.; El Kinany, S.; El Rhazi, K.; Zarrouq, B. Depression and Anxiety and Its Association with Problematic Social Media Use in the MENA Region: A Systematic Review. Egypt J Neurol Psychiatry Neurosurg 2024, 60, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, O.; Walsh, E.; Dawel, A.; Alateeq, K.; Oyarce, D.A.E.; Cherbuin, N. Social Media Use, Mental Health and Sleep: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analyses. Journal of Affective Disorders 2024, S0165032724014265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonzo, R.; Hussain, J.; Stranges, S.; Anderson, K.K. Interplay between Social Media Use, Sleep Quality, and Mental Health in Youth: A Systematic Review. Sleep Med Rev 2021, 56, 101414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.A.; Algorta, G.P. The Relationship Between Online Social Networking and Depression: A Systematic Review of Quantitative Studies. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 2016, 19, 638–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casale, S.; Banchi, V. Narcissism and Problematic Social Media Use: A Systematic Literature Review. Addictive Behaviors Reports 2020, 11, 100252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, C.; Gini, G.; Vieno, A.; Spada, M.M. The Associations between Problematic Facebook Use, Psychological Distress and Well-Being among Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders 2018, 226, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, H.; Bush, K.; Villeneuve, P.J.; Hellemans, K.G.; Guimond, S. Problematic Social Media Use in Adolescents and Young Adults: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JMIR Ment Health 2022, 9, e33450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Huang, L.; Yang, F. Social Anxiety and Problematic Social Media Use: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Addictive Behaviors 2024, 153, 107995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, S.; Iftikhar, A.; Meer, A. Intervening Effects of Academic Performance between TikTok Obsession and Psychological Wellbeing Challenges in University Students. Online Media and Society 2022, 3, 244–255. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrikse, C.; Limniou, M. The Use of Instagram and TikTok in Relation to Problematic Use and Well-Being. J. technol. behav. sci. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogowska, A.M.; Cincio, A. Procrastination Mediates the Relationship between Problematic TikTok Use and Depression among Young Adults. JCM 2024, 13, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.; Lewin, K.M.; Meshi, D. Problematic Use of Five Different Social Networking Sites Is Associated with Depressive Symptoms and Loneliness. Curr Psychol 2024, 43, 20891–20898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 Statement. Syst Rev 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, W.M. dos; Secoli, S.R.; Püschel, V.A. de A. The Joanna Briggs Institute Approach for Systematic Reviews. Rev. Latino-Am. Enfermagem 2018, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieminen, P. Application of Standardized Regression Coefficient in Meta-Analysis. BioMedInformatics 2022, 2, 434–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regression Methods in Biostatistics: Linear, Logistic, Survival, and Repeated Measures Models; Vittinghoff, E., Ed.; Statistics for biology and health; Springer: New York, 2005; ISBN 978-0-387-20275-4.

- Higgins, J. Measuring Inconsistency in Meta-Analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, B.C.; Schmid, C.H.; Lau, J.; Trikalinos, T.A. Meta-Analyst: Software for Meta-Analysis of Binary, Continuous and Diagnostic Data. BMC Med Res Methodol 2009, 9, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Garni, A.M.; Alamri, H.S.; Asiri, W.M.A.; Abudasser, A.M.; Alawashiz, A.S.; Badawi, F.A.; Alqahtani, G.A.; Ali Alnasser, S.S.; Assiri, A.M.; Alshahrani, K.T.S.; et al. Social Media Use and Sleep Quality Among Secondary School Students in Aseer Region: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Gen Med 2024, 17, 3093–3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asad, K.; Ali, F.; Awais, M. Personality Traits, Narcissism and TikTok Addiction: A Parallel Mediation Approach. International Journal of Media and Information Literacy 2022, 7, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarman, A.; Tuncay, S. The Relationship of Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, TikTok and WhatsApp/Telegram with Loneliness and Anger of Adolescents Living in Turkey: A Structural Equality Model. Journal of Pediatric Nursing 2023, 72, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, P.; Dong, X. Research on Adolescents Regarding the Indirect Effect of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress between TikTok Use Disorder and Memory Loss. IJERPH 2021, 18, 8820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Adnan, H.; Sarmiti, N. The Relationship Between Anxiety and TikTok Addiction Among University Students in China: Mediated by Escapism and Use Intensity. Int J Media Inf Lit 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, N.; Chen, J.; Huang, S.; Montag, C.; Elhai, J.D. Depression and Social Anxiety in Relation to Problematic TikTok Use Severity: The Mediating Role of Boredom Proneness and Distress Intolerance. Computers in Human Behavior 2023, 145, 107751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gil, J.F.; Chen, S.; Jiménez-López, E.; Abellán-Huerta, J.; Herrera-Gutiérrez, E.; Royo, J.M.P.; Mesas, A.E.; Tárraga-López, P.J. Are the Use and Addiction to Social Networks Associated with Disordered Eating Among Adolescents? Findings from the EHDLA Study. Int J Ment Health Addiction 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masciantonio, A.; Bourguignon, D.; Bouchat, P.; Balty, M.; Rimé, B. Don’t Put All Social Network Sites in One Basket: Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, TikTok, and Their Relations with Well-Being during the COVID-19 Pandemic. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landa-Blanco, M.; García, Y.R.; Landa-Blanco, A.L.; Cortés-Ramos, A.; Paz-Maldonado, E. Social Media Addiction Relationship with Academic Engagement in University Students: The Mediator Role of Self-Esteem, Depression, and Anxiety. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagrera, C.E.; Magner, J.; Temple, J.; Lawrence, R.; Magner, T.J.; Avila-Quintero, V.J.; McPherson, P.; Alderman, L.L.; Bhuiyan, M.A.N.; Patterson, J.C.; et al. Social Media Use and Body Image Issues among Adolescents in a Vulnerable Louisiana Community. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 1001336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, M.R.; Hogg, R.C. #ForYou? The Impact of pro-Ana TikTok Content on Body Image Dissatisfaction and Internalisation of Societal Beauty Standards. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasidi, Q.Y.; Norde, A.B.; Dahiru, J.M.; Hassan, I. Tiktok Usage, Social Comparison, and Self-Esteem Among the Youth: Moderating Role of Gender. gmd 2024, 6, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironica, A.; Popescu, C.A.; George, D.; Tegzeșiu, A.M.; Gherman, C.D. Social Media Influence on Body Image and Cosmetic Surgery Considerations: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e65626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincente-Benito, I.; Ramírez-Durán, M.D.V. Influence of Social Media Use on Body Image and Well-Being Among Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Review. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 2023, 61, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanis, P.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Moisoglou, I.; Konstantakopoulou, O. The TikTok Addiction Scale: Development and Validation 2024. [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Billieux, J.; Griffiths, M.D.; Kuss, D.J.; Demetrovics, Z.; Mazzoni, E.; Pallesen, S. The Relationship between Addictive Use of Social Media and Video Games and Symptoms of Psychiatric Disorders: A Large-Scale Cross-Sectional Study. Psychol Addict Behav 2016, 30, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.; Kim, D.-J.; Cho, H.; Yang, S. The Smartphone Addiction Scale: Development and Validation of a Short Version for Adolescents. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.-H.; Strong, C.; Lin, Y.-C.; Tsai, M.-C.; Leung, H.; Lin, C.-Y.; Pakpour, A.H.; Griffiths, M.D. Time Invariance of Three Ultra-Brief Internet-Related Instruments: Smartphone Application-Based Addiction Scale (SABAS), Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS), and the Nine-Item Internet Gaming Disorder Scale- Short Form (IGDS-SF9) (Study Part B). Addictive Behaviors 2020, 101, 105960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Qin, L.; Cheng, L.; Wang, S.; Zhu, Z.; Xu, J.; Chen, H.; Liu, Q.; Hu, M.; Tong, J.; et al. Determination the Cut-off Point for the Bergen Social Media Addiction (BSMAS): Diagnostic Contribution of the Six Criteria of the Components Model of Addiction for Social Media Disorder. JBA 2021, 10, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarate, D.; Hobson, B.A.; March, E.; Griffiths, M.D.; Stavropoulos, V. Psychometric Properties of the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale: An Analysis Using Item Response Theory. Addictive Behaviors Reports 2023, 17, 100473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servidio, R.; Griffiths, M.D.; Di Nuovo, S.; Sinatra, M.; Monacis, L. Further Exploration of the Psychometric Properties of the Revised Version of the Italian Smartphone Addiction Scale – Short Version (SAS-SV). Curr Psychol 2023, 42, 27245–27258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanis, P.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Moisoglou, I.; Konstantakopoulou, O. Determining an Optimal Cut-off Point for TikTok Addiction Using the TikTok Addiction Scale 2024. [CrossRef]

| Reference | Location | Data collection time | Sample size (n) | Age, mean (SD) | Females (%) | Population | Study design | Sampling method | Response rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [28] | China | 2022 | 822 | 27.5 (5.9) | 65.3 | Adults | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | 58.1 |

| [13] | Pakistan | 2022 | 240 | 18-25 years; 87%, 26-32; 13% | 42.0 | University students | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | NR |

| [24] | Pakistan | NR | 350 | NR | NR | University students | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | NR |

| [32] | USA | 2019 | 5070 | 15.8 (1.2) | 54.3 | School students | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | NR |

| [14] | United Kingdom | 2023 | 252 | 19.9 (4.7) | NR | University students | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | NA |

| [23] | Saudi Arabia | 2023 | 961 | 16.7 (2.1) | 59.3 | School students | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | NR |

| [30] | France | 2020 | 793 | 33.8 (14.7) | 77.3 | Adults | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | 79.0 |

| [31] | Honduras | 2022 | 412 | 22.2 (4.4) | 65.3 | University students | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | NR |

| [33] | Australia | 2023 | 273 | NR | 100 | University students | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | NA |

| [15] | Poland | 2022 | 448 | 24.5 (3.8) | 52.2 | Adults | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | NA |

| [27] | China | 2022 | 420 | 19.6 (1.0) | NR | University students | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | NR |

| [29] | Spain | 2021 | 653 | 14.0 (1.6) | 56.0 | School students | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | NR |

| [16] | USA | 2023 | 601 | 20.0 (1.6) | 65.7 | University students | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | NA |

| [26] | China | 2020 | 3036 | 16.6 (0.6) | 57.0 | School students | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | NR |

| [25] | Turkey | 2022 | 1176 | 15.6 (1.3) | 58.4 | School students | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | NR |

| [34] | Nigeria | 2023 | 314 | NR | NR | University students | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | 56.4 |

| Reference | Valid scale for the assessment of TikTok use | Assessment of TikTok use | Mental health variables | Valid scale for the assessment of mental health variables | Assessment of mental health variables |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [28] | Yes | SAS-SV (adapted version)a | Depression Social anxiety Distress intolerance |

Yes Yes Yes |

PHQ-9 SIAS DIS |

| [13] | Yes | BSMAS (adapted version)b | Depression Anxiety |

Yes No |

CES-D scale Twenty items |

| [24] | No | Six items (e.g., I feel irritated, because I feel too responsible for my TikTok-friends fun) | Narcissism |

Yes | NPI-16 |

| [32] | No | One item (Do you use TikTok?) | Body image issues | No | One item (Do you have body image issues?) |

| [14] | Yes | BSMAS (adapted version)b | Depression Loneliness |

Yes Yes |

CES-D scale UCLA Loneliness Scale |

| [23] | No | One item (Do you use TikTok?) | Poor sleep | Yes | PSQI |

| [30] | No | One item (Do you use TikTok?) | Life satisfaction | Yes | SWLS |

| [31] | No | One item (Do you use TikTok?) | Depression Anxiety |

Yes Yes |

PHQ-9 GAD-7 |

| [33] | No | One item (How often do you use TikTok?) | Disordered eating behaviour | Yes | EAT-26 |

| [15] | Yes | BSMAS (adapted version)b | Depression | Yes | PHQ-9 |

| [27] | Yes | BSMAS (adapted version)b | Anxiety | Yes | STAI |

| [29] | No | One item (How often do you use TikTok?) | Disordered eating | Yes | SCOFF |

| [16] | Yes | BSMAS (adapted version)b | Depression Loneliness |

Yes | PHQ-9 UCLA Loneliness Scale |

| [26] | Yes | SAS-SV (adapted version)a | Depression Anxiety Stress |

Yes Yes Yes |

DASS-21 DASS-21 DASS-21 |

| [25] | No | One item (Do you use TikTok?) | Loneliness Anger |

Yes Yes |

UCLA Loneliness Scale AARS |

| [34] | No | One item (How often do you use TikTok?) | Self-esteem | No | One item (How self-esteem do you feel?) |

| Reference | Mental health variables | Unstandardized regression coefficient (95% CI, p-value) | Correlation coefficient (p-value) | Other measures of effect | Level of analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [28] | Depression Social anxiety Distress intolerance |

0.40 (<0.01) 0.42 (<0.01) 0.46 (<0.01) |

Univariable | ||

| [13] | Depression Anxiety |

0.37 (NR, 0.03) 0.27 (NR, 0.01) |

Univariable | ||

| [24] | Narcissism | 0.49 (<0.01) | Univariable | ||

| [32] | Body image issues | 2.01 (1.74 to 2.31, <0.001)a | Multivariable | ||

| [14] | Depression Loneliness |

0.20 (NR, 0.001) NR (NR, 0.55) |

Multivariable | ||

| [23] | Poor sleep | 1.33 (1.01 to 1.77, 0.049)a | Multivariable | ||

| [30] | Life satisfaction | -0.04 (NR, >0.05) | Univariable | ||

| [31] | Depression Anxiety |

1.85 (<0.01)b 1.99 (<0.001)b |

Univariable | ||

| [33] | Disordered eating behaviour | 0.01 (0.31)c | Univariable | ||

| [15] | Depression | 0.26 (0.16 to 0.37, <0.001) | 0.38 (<0.001) | Multivariable | |

| [27] | Anxiety | 0.59 (NR) | Univariable | ||

| [29] | Disordered eating | 0.04 (0.19) | Univariable | ||

| [16] | Depression Loneliness |

0.28 (0.19 to 0.37, <0.001) 0.46 (0.31 to 0.60, <0.001) |

0.29 (<0.01) 0.26 (<0.01) |

Multivariable | |

| [26] | Depression Anxiety Stress |

0.27 (<0.01) 0.33 (<0.01) 0.33 (<0.01) |

Univariable | ||

| [25] | Loneliness Anger |

-0.4 (0.36)b 2.2 (0.03)b |

Univariable | ||

| [34] | Self-esteem | 0.33 (NR, <0.001) | Univariable |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).