Submitted:

04 November 2024

Posted:

05 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology and Materials

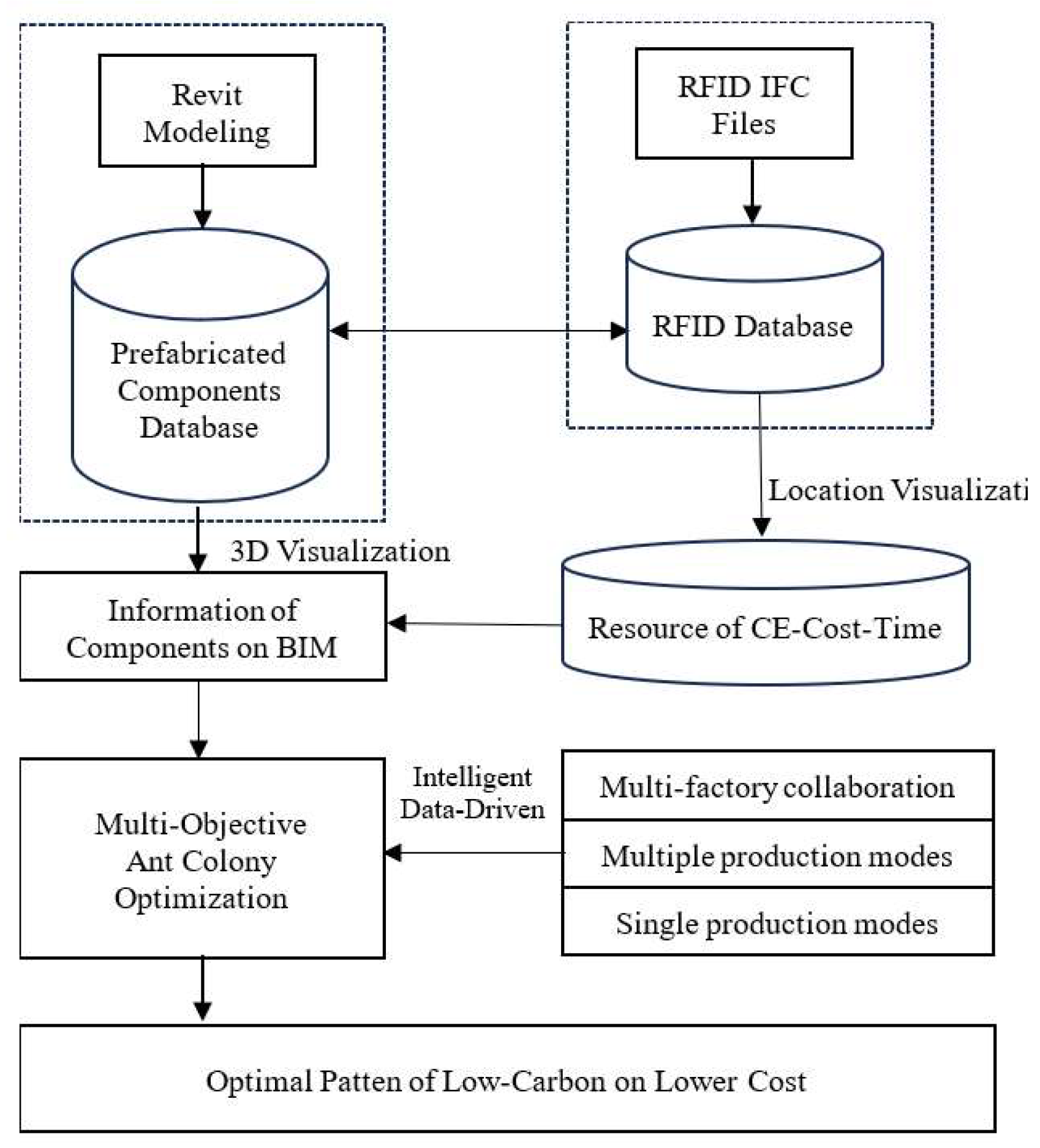

3.1. The Procedures

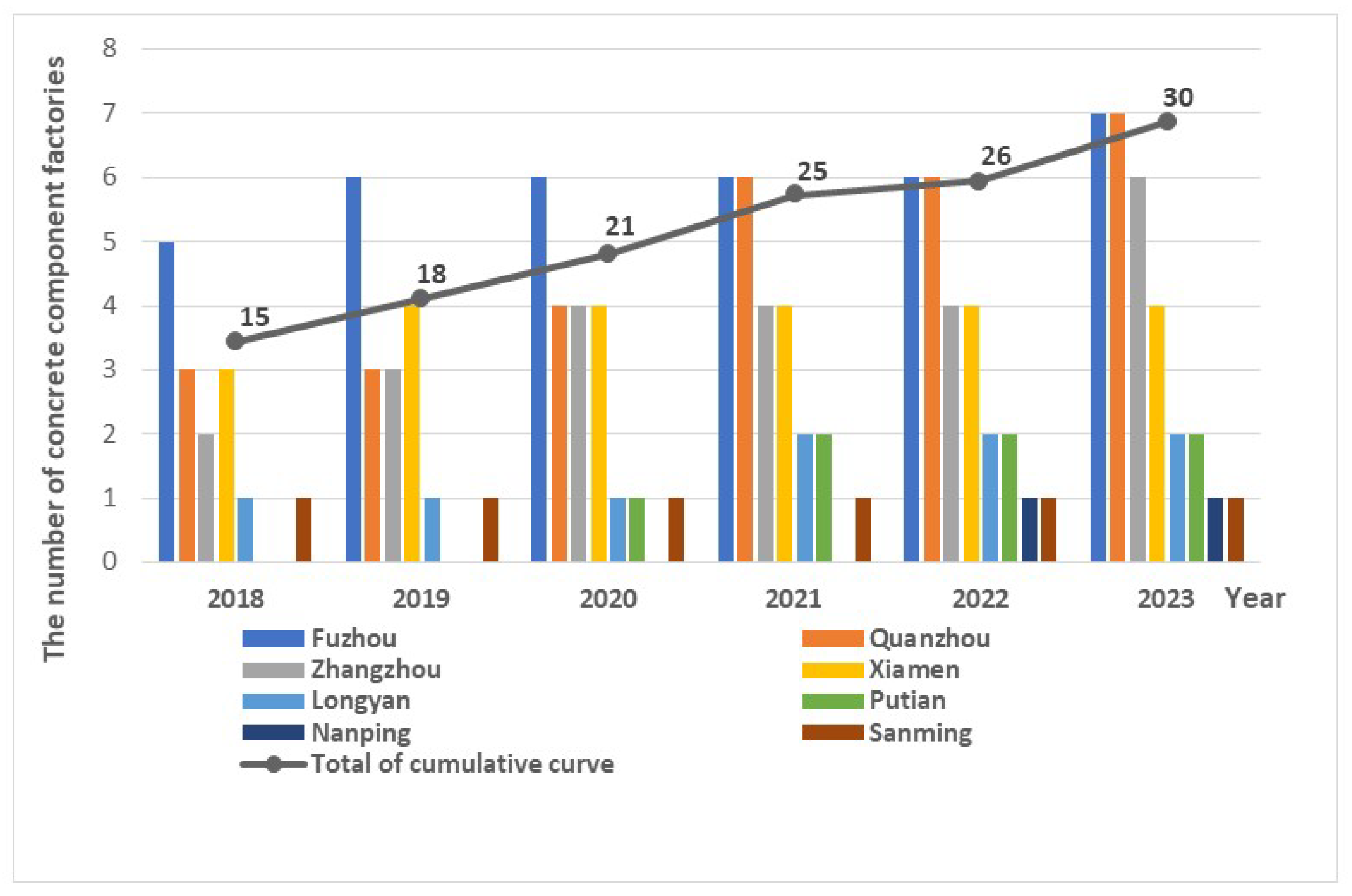

3.2. A Survey of Prefabricated Components Factories

3.3. The Design of Multi-Objective Model

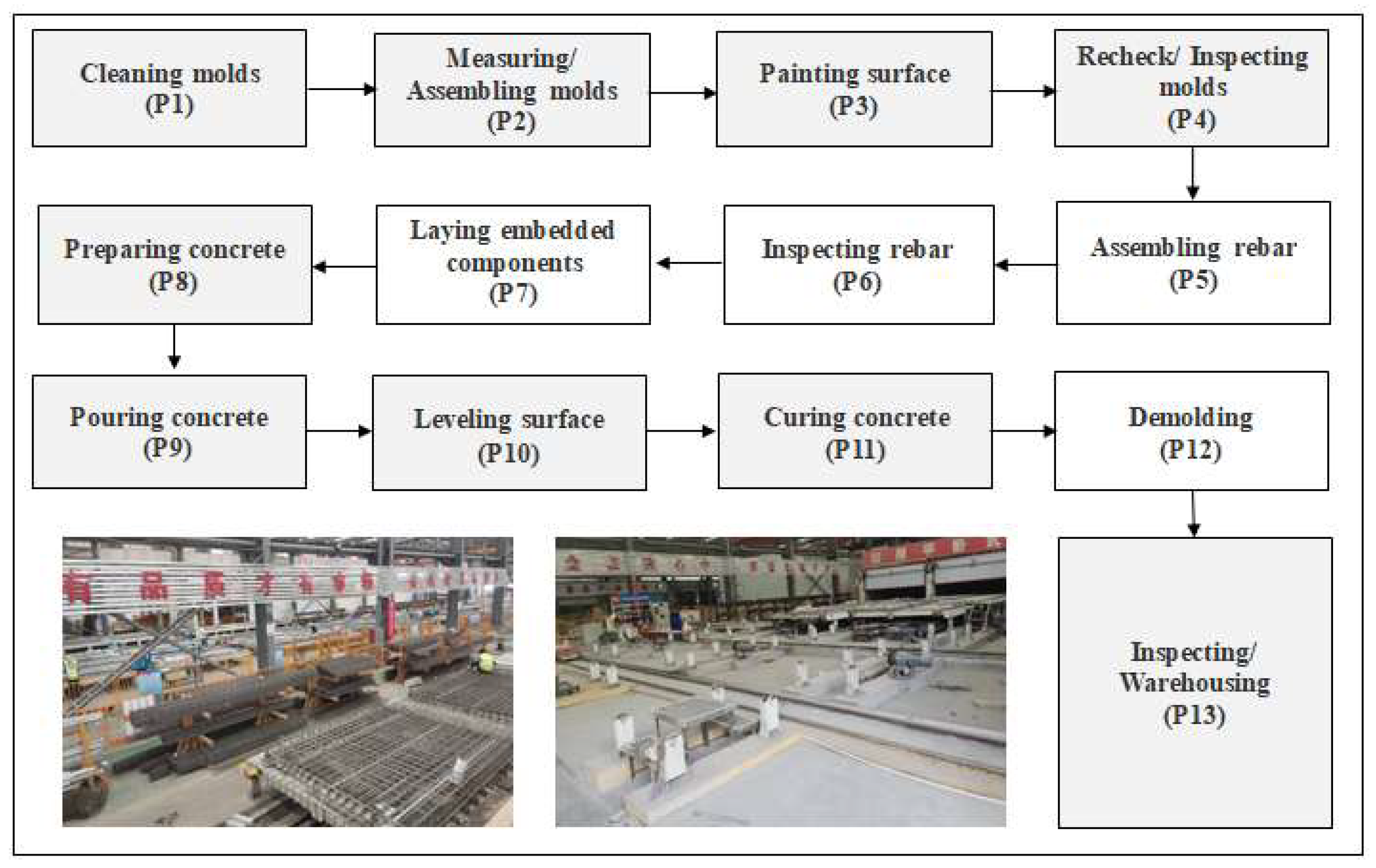

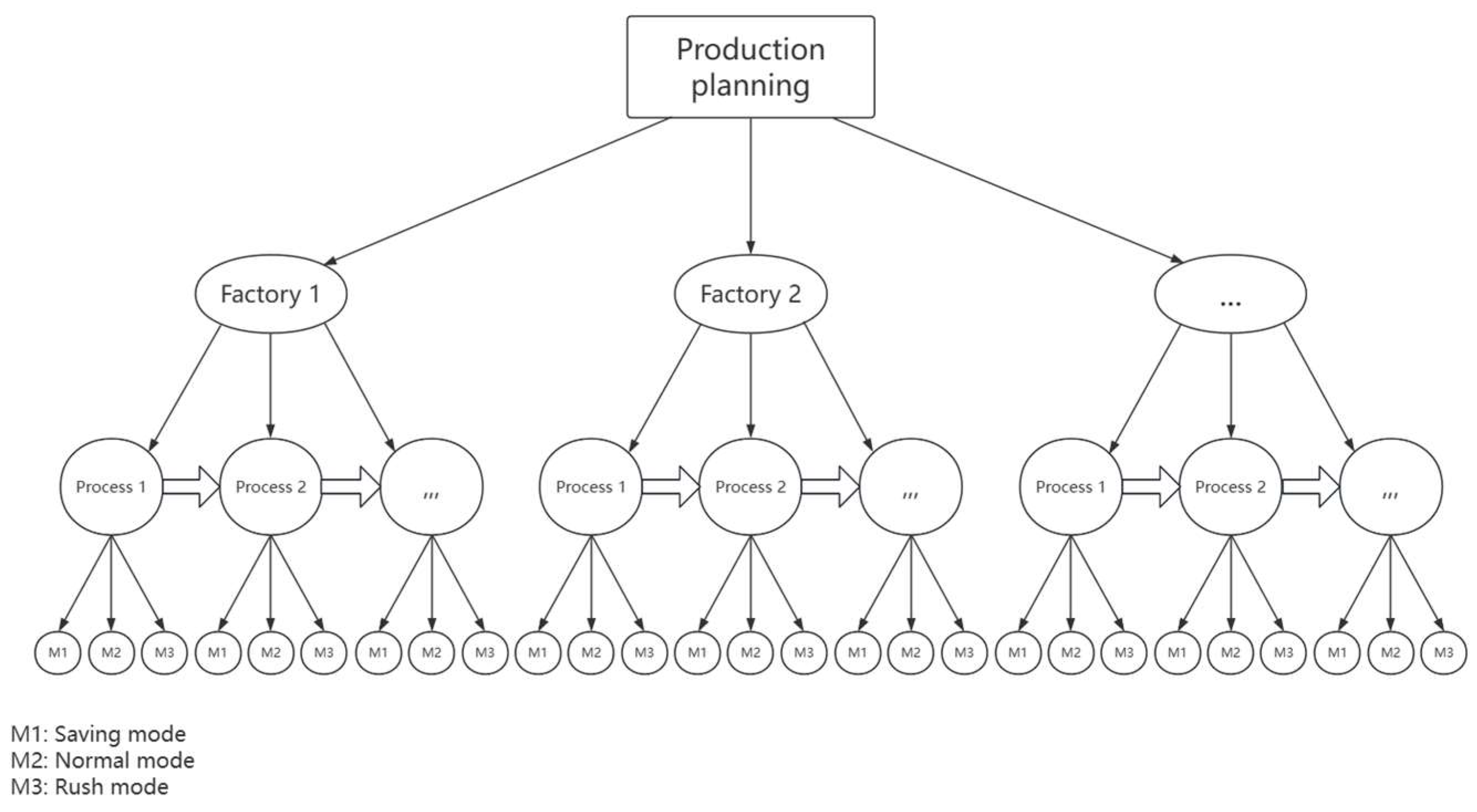

3.3.1. Problem Description

3.3.2. Design and Solution of Model

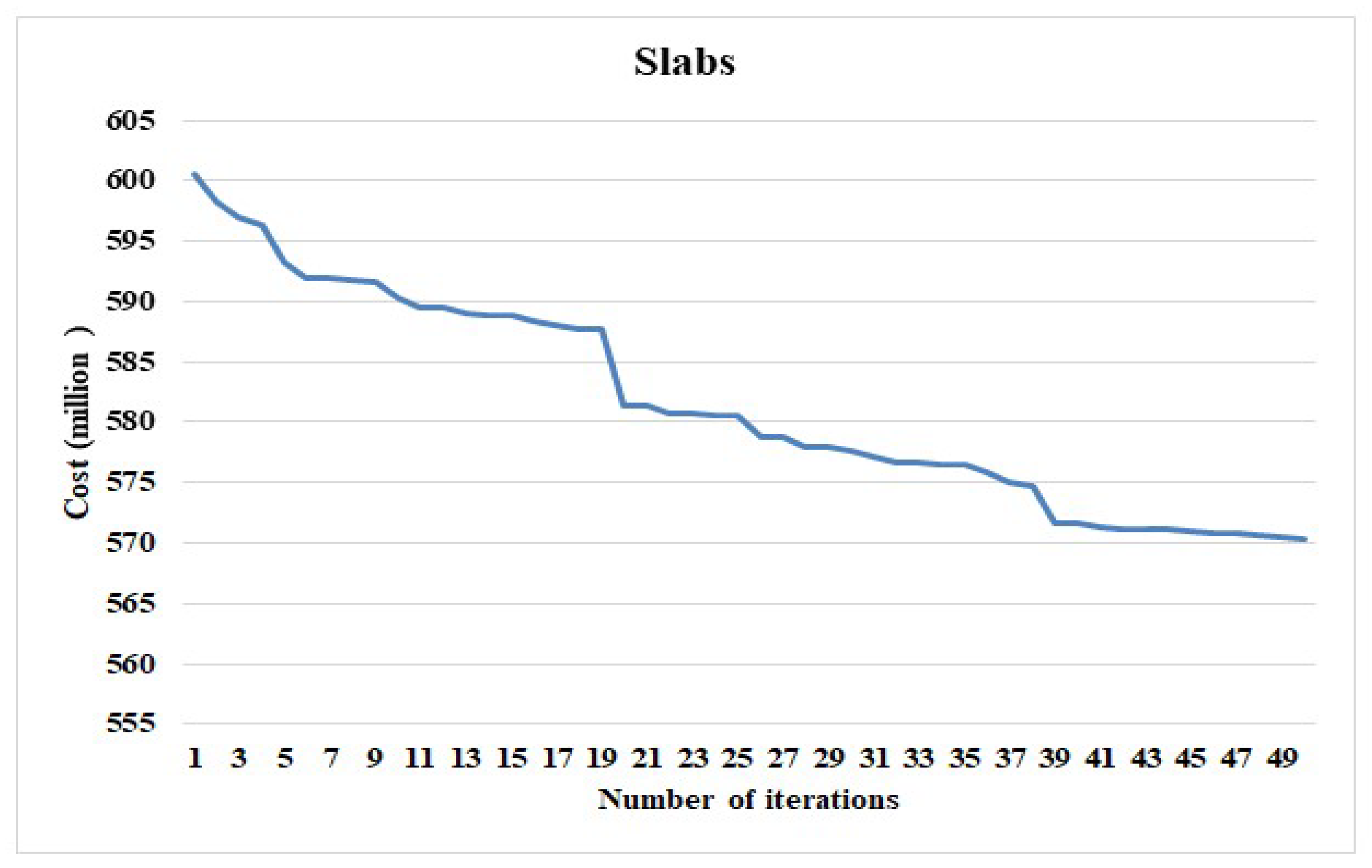

3.4. The Method of Algorithm Solving

4. Optimization of Intelligent Algorithms by Data-Driven

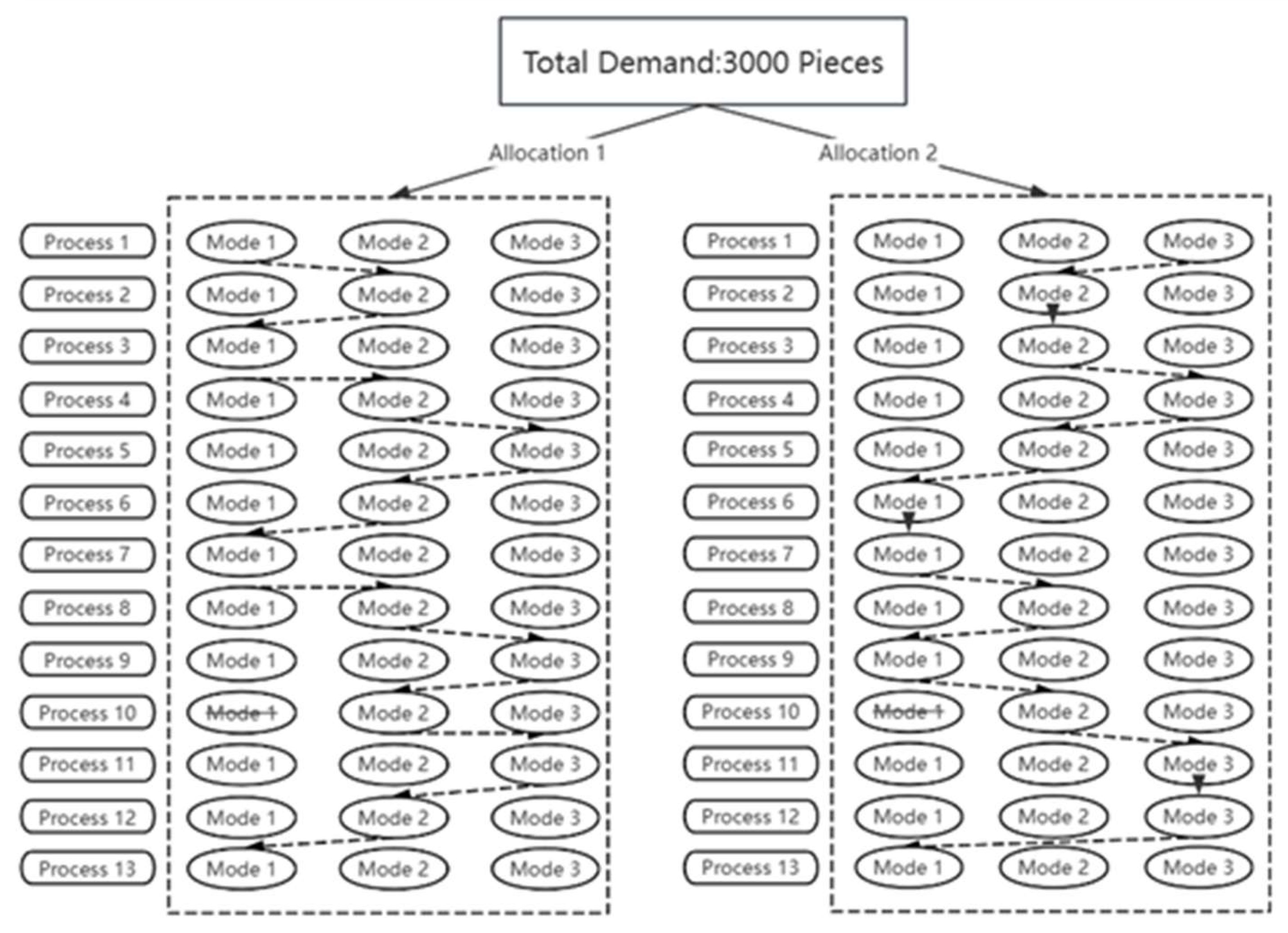

4.1. A Project with Collaborative Production in Prefabricated Factories

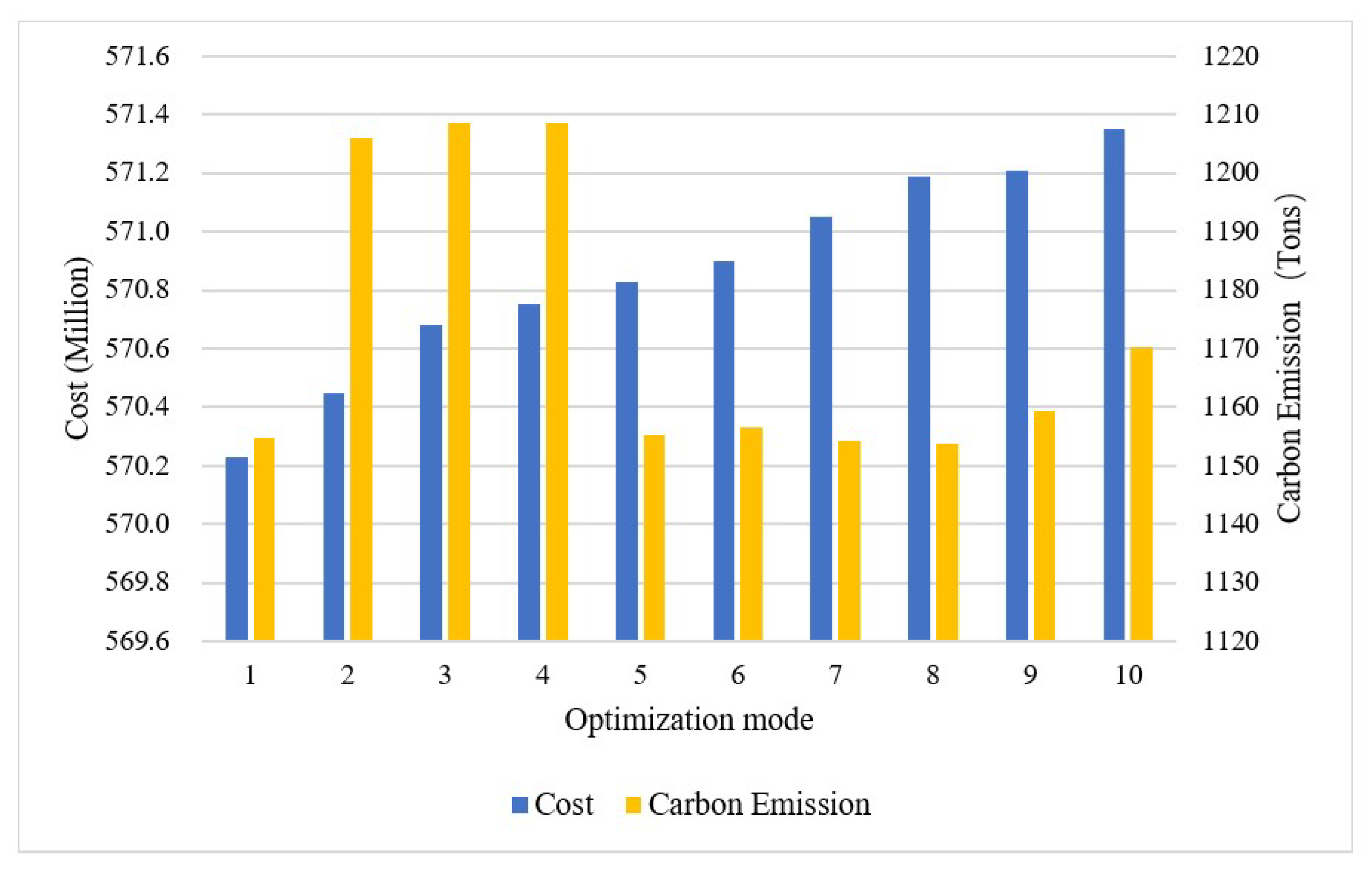

4.2. Optimization Modes of Prefabricated Components Production

4.3. Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023 Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2023, 35–115.

- Lu, H.; You, K.; Feng, W.; Zhou, N.; Fridley, D.; Price, L.; de la Rue du Can, S. Reducing China’s building material embodied emissions: Opportunities and challenges to achieve carbon neutrality in building materials. iScience 2024, 27, 109028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yu, B.; Wang, A. carbon emission analysis model for prefabricated construction based on LCA. Journal of Engineering Management 2018, 32, 30–33. [Google Scholar]

- Dahiya, D.; Laishram, B. Life cycle energy analysis of buildings: A systematic review. Building and Environment 2024, 252, 111160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, H.; Zhang, H.; Huang, B.; Gong, Y. BIM-Based Digital Construction Strategies to Evaluate Carbon Emissions in Green Prefabricated Buildings. Buildings 2024, 14, 1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, J.; Liu, C.; Zuo, C.; Hao, J.; Ma, W.; Duan, B.; Chen, C.; Liu, J. Reducing Carbon Emissions from Prefabricated Decoration: A Case Study of Residential Buildings in China. Buildings 2024, 14, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, V.; Lacerda, N.; Freire, F. Embodied energy and greenhouse gas emissions analysis of a prefabricated modular house: The “Moby” case study. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 212, 1044–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Zhang, T.; Zhou, X.; Li, Z.; Jia, Y. Life cycle environmental and cost assessment of prefabricated components manufacture. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 415, 137888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.L.; Cheng, B.; Lu, W.; Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Bu, W.; Guo, Z. Carbon emission reduction in prefabrication construction during materialization stage: A BIM-based life-cycle assessment approach. Science of the Total Environment 2018, 723, 137870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, M.; Kabirifar, K.; Fathollahi-Fard, A.M.; Mojtahedi, M. Production scheduling of off-site prefabricated construction components considering sequence dependent due dates. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Tao, X.; Mao, C.; He, W. Scheduling optimization for production of prefabricated components with parallel work of serial machines. Automation in Construction 2023, 148, 104770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, T.K.; Gwak, H.S.; Kim, B.S.; Lee, D.E. Integrated carbon emission estimation method for construction operation and project scheduling. KSCE Journal of Civil Engineering 2016, 20, 1211–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Hong, J.; Shen, G.Q.; Mao, C.; Zhang, H.; Li, Z. The exploration of the life-cycle energy saving potential for using prefabrication in residential buildings in China. Energy and Buildings 2018, 166, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebaibi, N.; Boutouil, M. Reducing energy consumption of prefabricated building elements and lowering the environmental impact of concrete. Engineering Structures 2020, 213, 110594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Wang, W.; Luo, Z.; Wang, Z.; Luo, J.; Lv, Y. Integrating BIM and machine learning to predict carbon emissions under foundation materialization stage: Case study of China's 35 public buildings. Frontiers of Architectural Research 2024, 13, 876–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, H.; Sun, J.; Zhang, X. Predictive models of embodied carbon emissions in building design phases: Machine learning approaches based on residential buildings in China. Building and Environment 2024, 258, 111595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Chen, R.; Xu, P.; Fu, Y.; Mao, C.; Hong, J. Real-time carbon emission monitoring in prefabricated construction. Automation in Construction 2020, 110, 102945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Guo, W.; Xu, X.; Deng, R.; Ding, X.; Chen, T. Analysis of carbon emission reduction paths for the production of prefabricated building components based on evolutionary game theory. Buildings 2023, 13, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Ma, K.; Mahamadu, A.; Florez-Perez, L.; Zhu, K.; Wu, H. Embodied carbon determination in the transportation stage of prefabricated constructions: A micro-level model using the bin-packing algorithm and modal analysis model. Energy and Buildings 2023, 279, 112640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Sun, Y. Evolutionary game analysis of collaborative prefabricated buildings development behavior in China under carbon emissions trading schemes. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xie, W.; Xu, L.; Li, L.; Jim, C.Y.; Wei, T. Holistic life-cycle accounting of carbon emissions of prefabricated buildings using LCA and BIM. Energy and Buildings 2022, 266, 112136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Dong, P.; Sugumaran, V. Dynamic production scheduling for prefabricated components considering the demand fluctuation. Intelligent Automation and Soft Computing 2020, 26, 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Gu, T.; Xu, P.; Hong, J.; Shrestha, A. A production line-based carbon emission assessment model for prefabricated components in China. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 209, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, C.H. An integrated framework for reducing precast fabrication inventory. Journal of Civil Engineering and Management 2010, 16, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.H.; Jaillon, L.; Chu, P.; Poon, C.S. Comparing carbon emissions of precast and cast-in-situ construction methods - A case study of high-rise private building. Construction and Building Materials 2015, 99, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Chen, Y.; Chang, R. Scheduling optimization of prefabricated construction projects by genetic algorithm. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 5531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, M.; Kabirifar, K.; Fathollahi-Fard, A.M.; Mojtahedi, M. Production scheduling of off-site prefabricated construction components considering sequence dependent due dates. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Tao, X.; Mao, C.; He, W. Scheduling optimization for production of prefabricated components with parallel work of serial machines. Automation in Construction 2023, 148, 104770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Xu, G.; Xue, F.; Zhong, R.Y.; Liu, D.; Lu, W. A physical internet-enabled Building Information Modelling system for prefabricated construction. International Journal of Computer Integrated Manufacturing 2018, 31, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calis, G.; Yuksel, O. An improved ant colony optimization algorithm for construction site layout problems. Journal of building construction and planning research 2015, 3, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoseiri, K.; Nadjari, B. An ant colony optimization algorithm for the bi-objective shortest path problem. Applied Soft Computing 2010, 10, 1237–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazır, Ö.; Haouari, M.; Erel, E. Robust scheduling and robustness measures for the discrete time/cost trade-off problem. European Journal of Operational Research 2010, 207, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, T.D.S.; Cruz, A.S.; Torres, M.; et al. Multi-objective optimization of school building envelope for two distinct geometric designs in southern Brazil. Indoor and Built Environment 2023, 32, 1778–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X. Grinding process optimization considering carbon emissions, cost and time based on an improved dung beetle algorithm. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2024, 197, 110600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daskin, M.; Benjaafar; Li Y. Carbon footprint and the management of supply chains: insights from simple models. IEEE transactions on automation science and engineering: a publication of the IEEE Robotics and Automation Society 2013, 10, 99–116. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, Y. Multi-objective optimization of construction project based on improved ant colony algorithm. Tehnički vjesnik 2020, 27, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Area | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

| Fuzhou | 97 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 121 |

| Longyan | 18 | 18 | 18 | 36 | 36 | 36 |

| Nanping | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 9 |

| Putian | 0 | 0 | 7 | 13 | 13 | 13 |

| Quanzhou | 30 | 30 | 35.5 | 50.5 | 50.5 | 60.5 |

| Sanming | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 |

| Xiamen | 80 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 110 |

| Zhangzhou | 27 | 33 | 59 | 59 | 59 | 70.4 |

| Total | 265 | 289 | 327.5 | 366.5 | 375.5 | 432.9 |

| No. | Operate process | Setup parameters |

| 1 | Initialize basic parameters |

Number of ant, I=10 Iterations, T=50 Pheromone evaporation factor, ρ=0.5 Pheromone constant, Q=10 Pheromone factor, α=4 Heuristic function factor, β=2 |

| 2 | Map Initialization |

|

| 3 | Initialize ant colony |

(3) |

| 4 | Calculate transfer probabilities and coverage Path Planning |

(4) |

| 5 | Update pheromones |

are both penalty factors. |

| 6 | Judgment cycle | Through continuous iteration, the maximum number of iterations is reached to optimal mode. |

| No. | Process | M1 | M2 | M3 | ||||||

|

Time (min.) |

Cost |

(kg.CO2) |

Time (min.) |

Cost |

(kg.CO2) |

Time (min.) |

Cost |

(kg.CO2) |

||

| 1 | P1 | 24 | 100 | 3.29 | 20 | 110 | 2.67 | 15 | 120 | 2.2 |

| 2 | P2 | 15 | 33 | 0.08 | 12 | 42 | 0.09 | 8 | 42 | 0.08 |

| 3 | P3 | 7 | 12 | 0.06 | 6 | 14 | 0.06 | 4 | 14 | 0.06 |

| 4 | P4 | 7 | 17 | 0.02 | 5 | 18 | 0.03 | 4 | 20 | 0.03 |

| 5 | P5 | 24 | 155 | 0.75 | 20 | 165 | 0.77 | 17 | 175 | 0.78 |

| 6 | P6 | 10 | 28 | 0.03 | 5 | 22 | 0.03 | 3 | 24 | 0.03 |

| 7 | P7 | 20 | 480 | 0.11 | 15 | 490 | 0.15 | 12 | 510 | 0.14 |

| 8 | P8 | 17 | 570 | 421.35 | 23 | 982 | 820.25 | 15 | 1080 | 702.65 |

| 9 | P9 | 25 | 35 | 7.25 | 20 | 42 | 5.87 | 12 | 45 | 4.06 |

| 10 | P10 | 15 | 21 | 2.26 | 10 | 25 | 2.12 | 8 | 33 | 1.75 |

| 11 | P11 | 480 | 418 | 0.02 | 420 | 375 | 0.02 | 390 | 382 | 0.02 |

| 12 | P12 | 15 | 38 | 6.85 | 10 | 42 | 4.68 | 6 | 75 | 4.22 |

| 13 | P13 | 11 | 22 | 10.74 | 12 | 25 | 11.43 | 6 | 27 | 8.67 |

| Optimization mode |

F-A Quantity |

F-A Path |

F-B Quantity |

F-B Path |

| 1 | 1245 | [0,0,0,1,0,1,0,0,1,0,2,0,1] | 1755 | [0,0,1,1,0,1,0,0,1,1,2,2,0] |

| 2 | 1673 | [0,0,0,1,0,2,0,0,1,0,1,0,0] | 1327 | [1,0,0,1,2,1,1,0,0,0,1,2,2] |

| 3 | 1688 | [1,0,2,0,0,2,0,0,0,1,1,1,0] | 1312 | [1,2,1,0,1,0,1,0,0,1,1,1,1] |

| 4 | 1688 | [0,0,0,0,0,2,0,0,0,0,2,0,2] | 1312 | [2,1,1,0,0,1,2,0,0,1,2,0,0] |

| 5 | 1253 | [0,2,1,1,0,2,0,0,1,0,2,1,0] | 1747 | [0,0,0,0,1,1,1,0,2,0,1,2,1] |

| 6 | 1260 | [2,1,1,2,0,0,0,0,0,0,1,0,1] | 1740 | [0,0,2,0,0,2,0,0,1,0,2,1,2] |

| 7 | 1260 | [0,1,0,2,1,2,0,0,1,0,2,0,0] | 1740 | [0,0,0,0,0,1,0,0,2,1,2,1,0] |

| 8 | 1223 | [0,1,0,2,0,0,0,0,0,1,1,1,1] | 1777 | [0,0,2,1,1,2,1,0,2,1,1,2,1] |

| 9 | 1260 | [0,2,0,0,0,0,0,0,1,2,1,0,2] | 1740 | [0,1,2,0,1,2,1,0,1,0,1,1,0] |

| 10 | 1283 | [0,0,2,0,0,0,1,0,0,2,2,0,0] | 1717 | [0,1,1,0,1,1,2,0,0,0,1,0,2] |

| Optimization mode | Slab | Wall | Stair | |||

|

Cost (million ) |

CE (ton) |

Cost (million ) |

CE (ton) |

Cost (million ) |

CE (ton) |

|

| 1 | 570.23 | 1154.85 | 610.58 | 1188.68 | 194.48 | 410.71 |

| 2 | 570.45 | 1206.08 | 611.03 | 1250.55 | 195.13 | 412.16 |

| 3 | 570.68 | 1208.63 | 611.09 | 1251.68 | 195.28 | 405.11 |

| 4 | 570.75 | 1208.63 | 611.42 | 1185.9 | 195.52 | 407.36 |

| 5 | 570.83 | 1155.23 | 611.48 | 1190.7 | 195.89 | 405.84 |

| 6 | 570.9 | 1156.58 | 611.78 | 1245.15 | 195.91 | 407.12 |

| 7 | 571.05 | 1154.4 | 611.93 | 1239.68 | 196.16 | 413.05 |

| 8 | 571.19 | 1153.8 | 612.15 | 1246.5 | 196.45 | 412.24 |

| 9 | 571.21 | 1159.43 | 612.31 | 1246.65 | 196.48 | 410.73 |

| 10 | 571.35 | 1170.3 | 612.38 | 1244.18 | 196.56 | 409.12 |

| Mode | M1 | M2 | M3 | ||||||

| Time limit |

Cost reduction(%) |

CE reduction (%) |

Time limit |

Cost reduction(%) |

CE reduction(%) |

Time limit |

Cost reduction(%) |

CE reduction(%) |

|

| 1 | F | 1.64 | 0.43 | T | 23.24 | 52.85 | T | 22.13 | 49.66 |

| 2 | T | 1.56 | 0.18 | T | 23.04 | 51.22 | T | 22.13 | 46.74 |

| 3 | T | 1.52 | 0.11 | T | 23.00 | 51.13 | T | 22.10 | 46.61 |

| 4 | T | 1.51 | 0.11 | T | 23.00 | 51.13 | T | 22.09 | 46.61 |

| 5 | F | 1.54 | 0.47 | T | 23.16 | 52.84 | T | 22.05 | 49.63 |

| 6 | F | 1.52 | 0.42 | T | 23.14 | 52.79 | T | 22.04 | 49.56 |

| 7 | F | 1.50 | 0.61 | T | 23.12 | 52.88 | T | 22.02 | 49.65 |

| 8 | F | 1.48 | 0.31 | T | 23.12 | 52.87 | T | 22.00 | 49.74 |

| 9 | F | 1.47 | 0.18 | T | 23.10 | 52.68 | T | 22.00 | 49.43 |

| 10 | F | 1.45 | -0.53 | T | 23.07 | 52.26 | T | 21.98 | 48.93 |

| Average | 1.52 | 0.23 | - | 23.10 | 52.27 | - | 22.05 | 48.66 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).