Children's tracheotomy is a procedure of great complexity due to the huge number of questions and emerging problems related to it, starting from indications and contraindications assessment for its performance in each child, going through the choice of an exact surgical method for its implementation and reaching the care of the tracheotomized child in all their complexity, comprehensiveness and incessantness.

From a physiological point of view, the tracheostomy is a pathological opening of the neck, allowing air to enter the trachea, bronchi and lungs without passing through the upper respiratory tract, where it is warmed and moistened [

2]. Therefore, the air inhaled through the cannula must be warmed and moist. This helps to avoid discomfort, thickening of secretions and formation of a mucus plug [

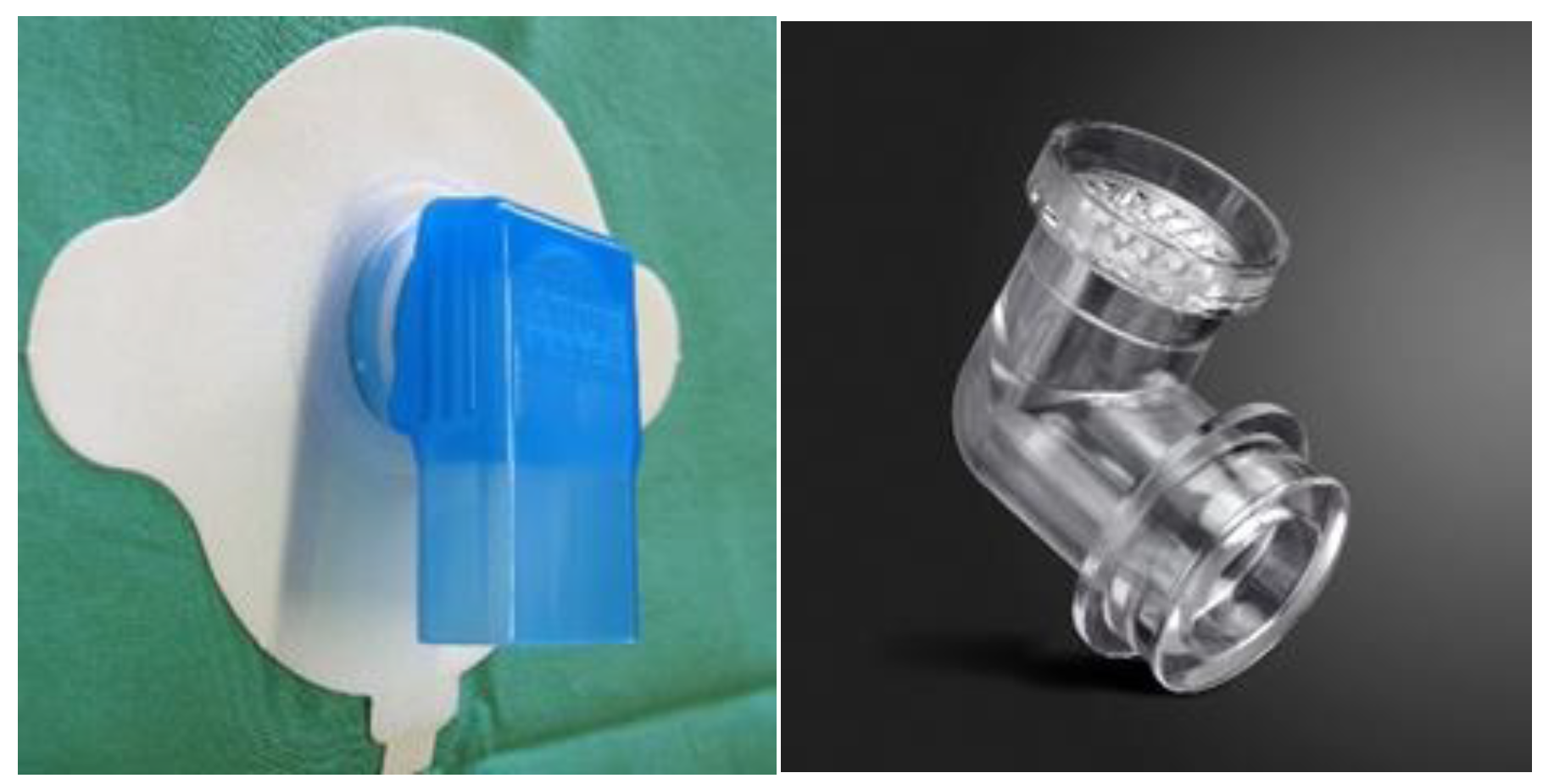

1]. To humidify the inhaled air, a passive humidifier (artificial nose’) [

2,

4] can be used, which captures the water vapor and temperature exhaled by the child and transmits part of them to the inhaled air. The effect of using humidifiers in children is good, and their tolerance by the child in most cases is problem-free.

Since the cough reflex is usually absent in tracheotomized children, the collected secretions must be aspirated regularly, and atraumatically/care is taken not to injure the inner surface of the trachea/. The aspiration frequency is strictly individual and relies on the "as needed" principle. In the first days after tracheotomy, the child needs more frequent aspiration of secretions, and gradually the aspiration decreases, but not less than twice a day [

4,

5]. The aspiration pressure is usually between 80 and 150 mm Hg. Its measurement is essential for the effectiveness and safety of tracheal aspiration. For routine suction, a catheter with outer diameter approximately 50% of the tube’s lumen is used, and if rapid removal of secretions is needed, catheter with outer diameter of approximately 75% of the lumen is used [

4].

There is a greater tendency for respiratory tract infection and foreign body aspiration after tracheostomy. Therefore, aspiration catheters should be changed frequently (single use only if possible) and the rules of aseptic should be observed during aspiration to prevent possible infection. Care should be taken to prevent foreign bodies falling into the tracheostomy opening.

1.1. Care at Hospital

It is desirable to create a team of nurses, doctors and respiratory therapists in order to manage all situations (from harmless to high-risk) related to the tracheostomy even before the surgery is carried out. This team discusses all tracheostomy related issues - humidification and aspiration (frequency and depth), behavior algorithm in case of accidental decannulation (switching to endotracheal intubation or reinsertion of the cannula and its fixation to the skin with several stitches) and others.

The first change of the cannula is usually done a week after its placement in order to give the tracheostomy time to "mature" [

2,

3]. This first change is usually done by the surgical team that performed the tracheostomy, and the team that will take care of it usually(as a rule) observes the procedure. The team must be ready for possible intubation if the airway is lost during the shift due to inability to reinsert the cannula. The ties and gauze pad should be replaced with new ones every daiy or more often if necessary. The frequency of changing the cannula varies widely, depending directly on care taken - aspiration and humidification.

Children can be fed soon after the surgery – as soon as they fully wake up from anesthesia. Some of them may lose certain reflexes and feeding may be difficult - this necessitates the placement of a feeding tube for a certain period of time.

Tracheotomized children lose ability to communicate through speech. The older ones use signs or writing. If its condition is stable, the child can phonate if the cannula (cannula without balloon) does not exceed 2/3 of the diameter of the trachea. In some patients, the ability to vocalize is observed when the cannula is occluded (cannula without balloon). Another way to preserve phonation is the use of fenestrated cannulas, which are not recommended in the early postoperative period.

Both the team performed the tracheotomy and the care team perform daily assessment of the tracheostomy condition, watching for signs of an emerging complication - bleeding, inflammation, etc.

Simultaneously with the care of the child, the training of the parents (the people who will nurse the child outside the hospital) begins [

3], and in many cases they themselves need psychological support. Education is started preferably before elective tracheotomy [

4].

Children should not be discharged from the hospital until their parents or caregivers have been trained in all routine care procedures and in providing emergency care in life-threatening situation[4,6].

1.2. Care at Home

The care of a child with a tracheostomy at home is usually taken over by his parents/guardians, and for children raised in orphanages or other social facilities by the staff of the respective institution. Despite the preliminary training, the commitments related to the care of the small patient have severe physical and especially psychological influence on them, especially in the first days and weeks after discharge. Happily gradually solving the problems surrounding raising a child with a tracheostomy is becoming a routine and the pressure decreases. In a number of countries, home care is provided by nurses by law.

When a child with a tracheostomy is discharged from hospital, the medical team is required to provide a list of the necessary items for the care of the tracheostomy and cannula [

7]. The most basic consumables are spare cannulas, gauzes, canula bandages, plasters, syringes, tweezers, scissors, aspiration catheters, sterile and non-sterile gloves, saline solution and local antiseptics. The necessary equipment includes a mobile aspiration pump, air humidifier, oxygen source, saturation monitor and, in a few cases respiratory device may also be necessary.

How often the cannula must be changed is an important question. In children, it is generally accepted that the change is carried out once a week [

2], although the need for this is strictly individual - in some patients it is necessary to change more often, in others much less often. This mostly depends on the material of the tube and the presence of infection and/or secretions [

4].

The life of modern tracheostomy tubes is usually 4-6 months, after that they have to be thrown away and replaced with new ones. When children with a tracheostomy are raised at home, their parents should always have spare tracheostoma tubes available for emergency situations: first identical to the one currently in use, and second – with diameter one size smaller.

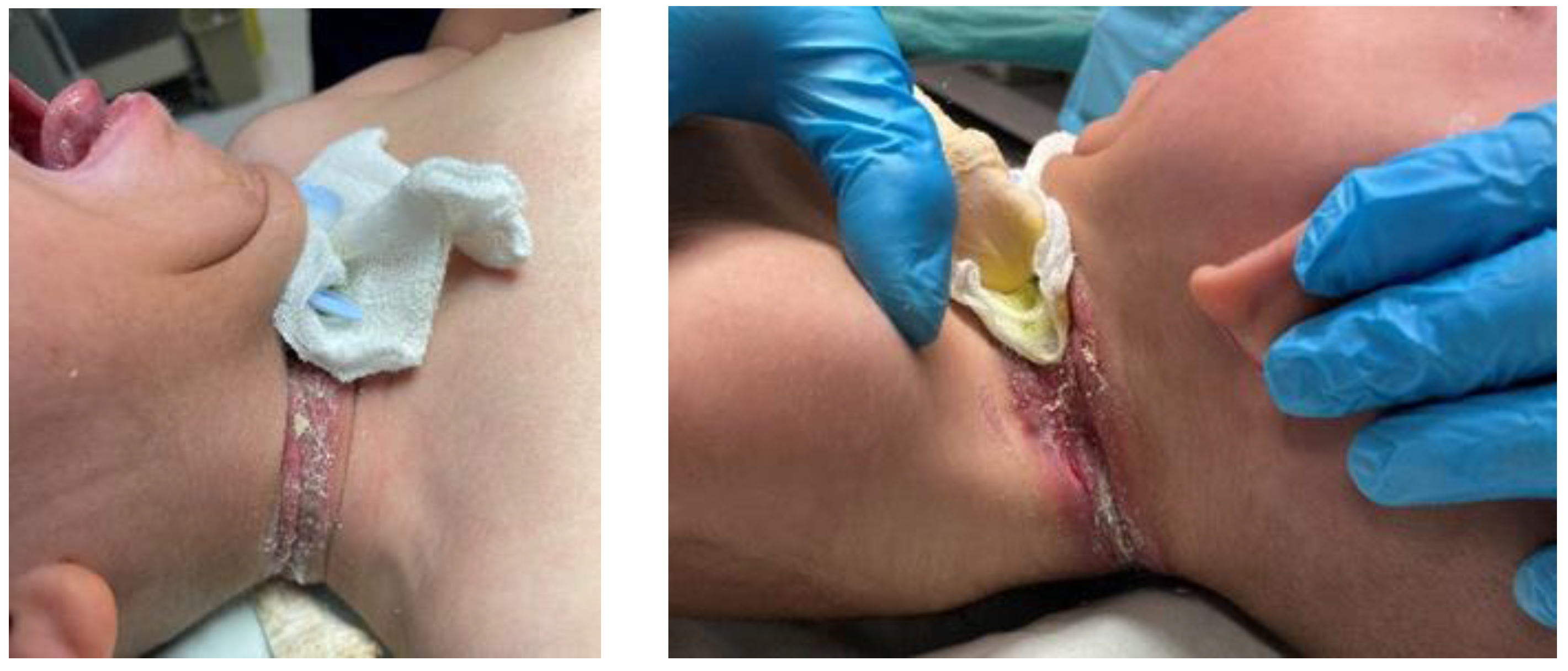

The tracheostoma tube ties have to be changed daily and immediately after contamination or wetting. After tying the new ties, it should be possible for the attendant to slip a finger under them without difficulty [

4]. Over-tightening the tracheostoma tube ties over the child's neck quickly and easily leads to complications (

Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Proper care of the tracheostomy is essential. The skin around the stoma opening should be cleaned with damp, but not wet, clean cloth. Dried crusts under the tracheostoma tube plate are removed using saline-soaked swab.

Normal speech and language development require vocal exploration and social interaction, both of which are limited when a tracheostomy tube is in place, especially in an infant. The best way for dealing with that problem is the use of speaking valves [

2,

7].

The pad (usually gauze) that is placed under the cannula to prevent tracheostomy opening trauma (

Figure 3) is changed daily or when it gets wet or soiled.

Many of the daily activities associated with raising a child are additionally complicated by the presence of a tracheostomy, including feeding. The main problem in most cases is the possibility of food particles getting in the vicinity of the tracheostomy opening and their aspiration. Water and other liquids (milk) intake should also be done carefully, otherwise a large amount of liquid may be aspired with subsequent respiratory problems. That is why it is

absolutely contraindicated to let these children eat and drink liquids without adult supervision [

4].

Bathing is one of the most enjoyable activities for parents and children. In cases with a tracheostomy, however, a number of problems arise again, related to water splashes entering the trachea and bronchi through the tracheostomy opening. It is generally recommended tracheostomized children to take bathe not shower, where it is much easier water drops to enter the cannula opening. To minimize this rick, collar waterproof protectors is recommended to be used [

4]

Figure 4.

Older tracheotomized children can take shower, as the placement of protective devices over the cannula opening is mandatory. Specially designed shower protectors are used, which are attached directly to the opening of the cannula and provide a high degree of protection against splashes of water entering its opening Figure №5.

Getting out of the house is also a challenge for a child with a tracheostomy. There he faces many problems and challenges not typical of the non-tracheotomized individual. Garden sprinklers, fountains, swimming pools, sandboxes should be avoided. Playing with furry animals as well as birds is also not a good idea due to the risk of particles getting into the cannula opening. Dust on the streets and buildings, polluted air, smoke, fog and pollens are irritants for him that should not be underestimated. Adequate protection from environmental factors can be achieved by using tracheostomy protectors. They are made of high quality breathable materials and are available in different sizes, shapes and colors

Figure 6.

When the child is outside the environment in which it is raised, a set of tools and supplies necessary for tracheostomy care and emergency situations need to accompany it. It is recommended that this 'travel' service kit to be different from the kit used at the child's home to avoid the risk of forgetting or misplacing apparatus, instrument or consumable that may prove vital in an emergency situation.

Following the tracheostomized child taking care rulesin the hospital, at home, and outside helps minimize the risks associated with the tracheostomy and cannula, but does not eliminate them completely.