Submitted:

05 November 2024

Posted:

05 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

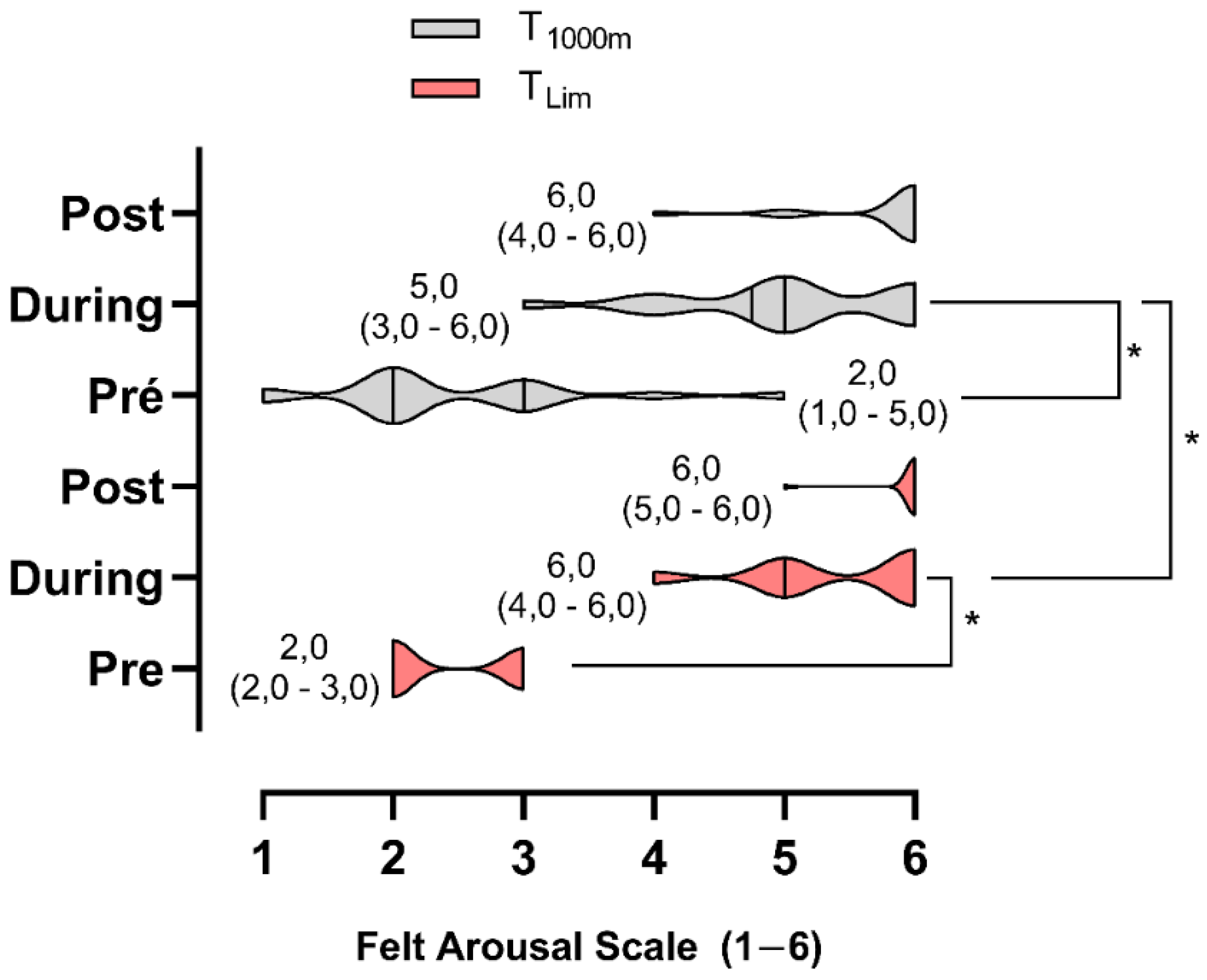

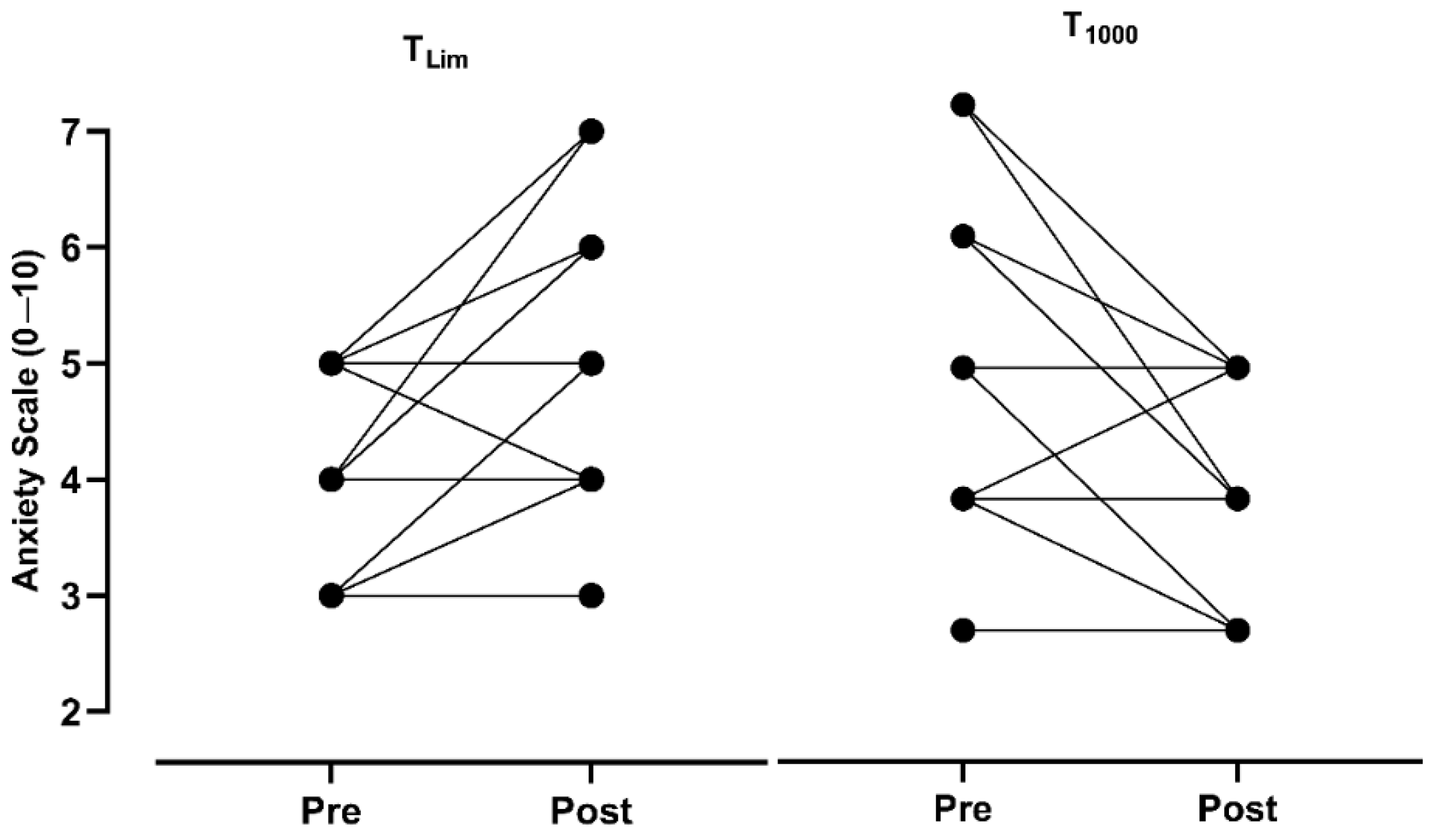

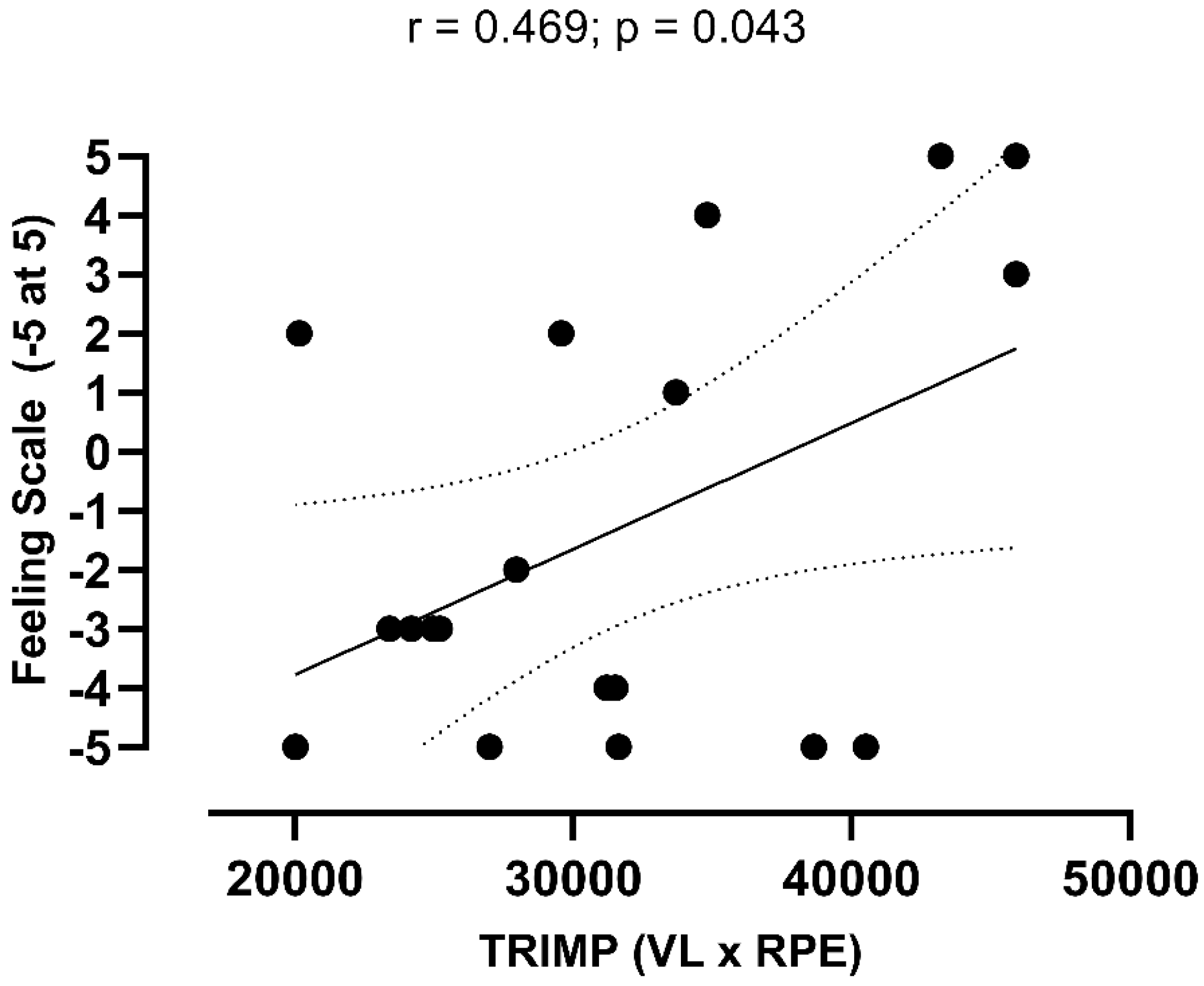

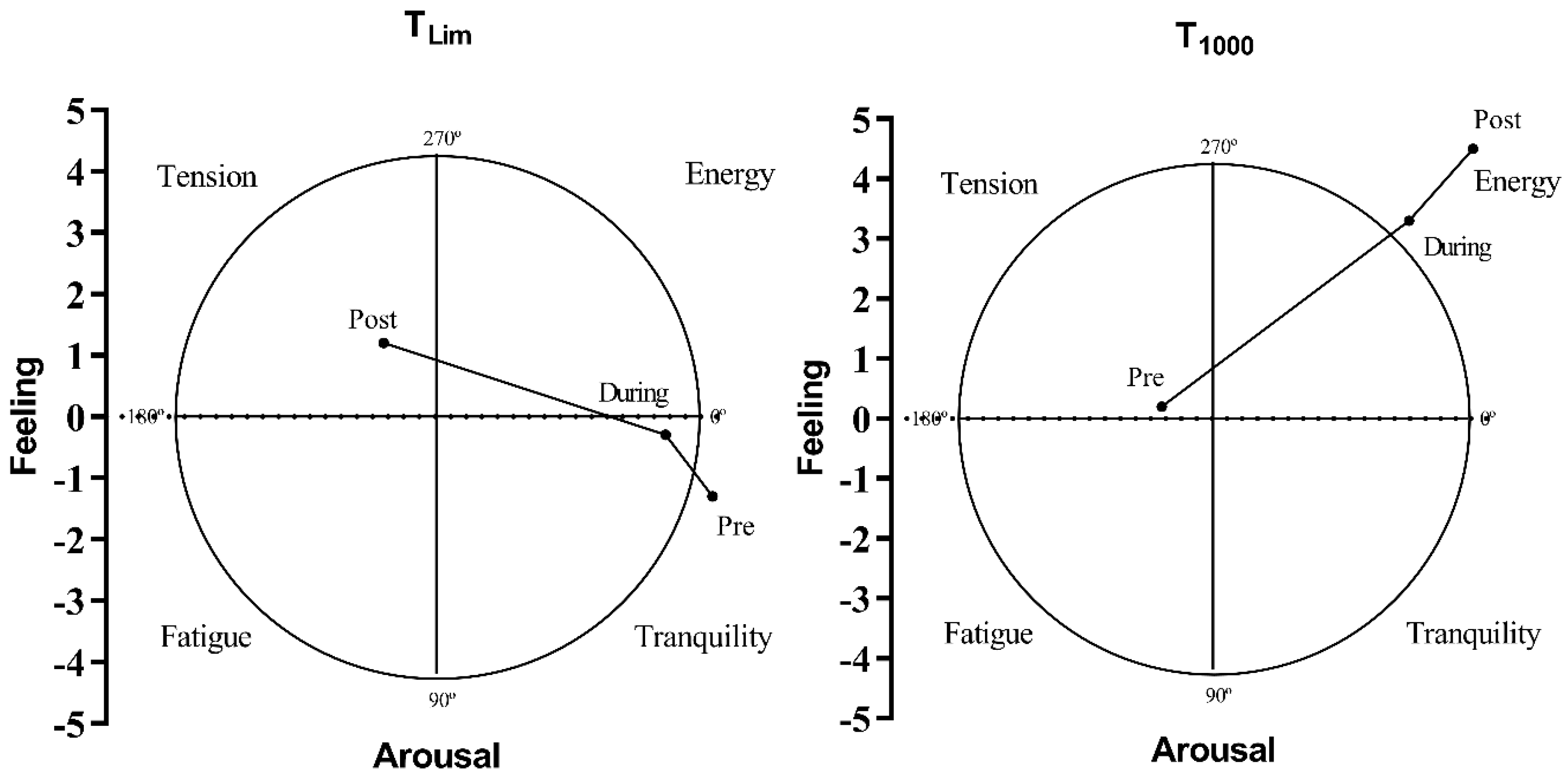

Objective: To evaluate the affective responses to running with imposed velocity or self-selected time trials in runners, as well as the effects on volume load (VL) and training impulse (TRIMP). Anxiety was also determined. We establish the level of association between the dependent variables. Methods: Three visits were carried out. 1st visit consisted of a maximum running effort test (VO2Max). 2nd and 3rd visits, participants were divided between the time limit (TLim) or time trial 1000m running at self-selected intensity (T1000). Participant responded to felt arousal, feeling and anxiety SUDS scale, before, during and after TLim and T1000. Results: TLim vs. T1000 (p<0.001), VPeak x V1000 (p=0.013), showed differences, but did not influence VLTLim vs. VL1000 (3181.34 ± 872.22 vs. 3570.60 ± 323.3; p=0.062). TRIMP showed no differences (p=0.068). Arousal did not differ between the pre-exercise (p=0.772) and post-exercise (p=0.083) groups, but was different during (p=0.035). There were differences between groups in the pre-exercise (p=0.012), during (p<0.001) and post-exercise (p<0.001) for feeling and anxiety scores. The correlation between TRIMP and affective scores showed association for TLim (r=0.46; p=0.043). Conclusion: The self-selected exercise generated positive affective responses, but the same did not occur for the imposed TLim. VL and TRIMP presented equality. There was association TRIMP and TLim feeling scale. TLim significantly increased anxiety scores.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Experimental Approach

Sample

Procedures

Body Morphology

Progressive Maximal Exercise Test

| Board 1. VO2Max estimation equation. |

| VO2Max = (0,2 x velocity x slope) + 3,5 |

| Where: VO2Max - maximum oxygen consumption in mL·kg1·min1; Velocity – m·min-1 Slope – centesimal unit |

Time to Exhaustion Protocol (TLim)

1000m Time Trial Protocol (T1000)

Subjective Measurement Instruments

Calculation of Volume Load and Training Impulse (TRIMP)

Randomization Process

Data Analysis and Processing

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Primary Outcomes

3.2. Secondary Outcome

3.3. Tertiary Outcome

3.4. Unintended Harm

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Atakan MM, Li Y, Kosar SN, Turnagol HH, Yan X. Evidence-Based Effects of High-Intensity Interval Training on Exercise Capacity and Health: A Review with Historical Perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(13). [CrossRef]

- Gibala MJ, Little JP, Macdonald MJ, Hawley JA. Physiological adaptations to low-volume, high-intensity interval training in health and disease. J Physiol. 2012;590(5):1077-1084. [CrossRef]

- Ito S. High-intensity interval training for health benefits and care of cardiac diseases - The key to an efficient exercise protocol. World J Cardiol. 2019;11(7):171-188. [CrossRef]

- Weston KS, Wisloff U, Coombes JS. High-intensity interval training in patients with lifestyle-induced cardiometabolic disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(16):1227-1234. [CrossRef]

- Salmon J, Owen N, Crawford D, Bauman A, Sallis JF. Physical activity and sedentary behavior: a population-based study of barriers, enjoyment, and preference. Health Psychol. 2003;22(2):178-188. [CrossRef]

- Buchheit M, Laursen PB. High-intensity interval training, solutions to the programming puzzle: Part I: cardiopulmonary emphasis. Sports Med. 2013;43(5):313-338. [CrossRef]

- Buchheit M, Laursen PB. High-intensity interval training, solutions to the programming puzzle. Part II: anaerobic energy, neuromuscular load and practical applications. Sports Med. 2013;43(10):927-954. [CrossRef]

- Kellogg E, Cantacessi C, McNamer O et al. Comparison of Psychological and Physiological Responses to Imposed vs. Self-selected High-Intensity Interval Training. J Strength Cond Res. 2019;33(11):2945-2952. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira BRR, Santos TM, Kilpatrick M, Pires FO, Deslandes AC. Affective and enjoyment responses in high intensity interval training and continuous training: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0197124. [CrossRef]

- Foster C, Farland CV, Guidotti F et al. The Effects of High Intensity Interval Training vs Steady State Training on Aerobic and Anaerobic Capacity. J Sports Sci Med. 2015;14(4):747-755.

- Oliveira BR, Slama FA, Deslandes AC, Furtado ES, Santos TM. Continuous and high-intensity interval training: which promotes higher pleasure? PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e79965. [CrossRef]

- Batista DR, Meneghel V, Ornelas F, Moreno MA, Lopes CR, Braz TV. Respostas fisiológicas e afetivas agudas em mulheres na pós menopausa durante exercício aeróbio prescrito e auto-selecionado. Cuadernos de Psicología del Deporte. 2019;19(1):28-38.

- Ekkekakis P. Let them roam free? Physiological and psychological evidence for the potential of self-selected exercise intensity in public health. Sports Med. 2009;39(10):857-888. [CrossRef]

- Ekkekakis P, Lind E, Vazou S. Affective responses to increasing levels of exercise intensity in normal-weight, overweight, and obese middle-aged women. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2010;18(1):79-85. [CrossRef]

- Rose EA, Parfitt G. Exercise experience influences affective and motivational outcomes of prescribed and self-selected intensity exercise. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2012;22(2):265-277. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira BR, Deslandes AC, Santos TM. Differences in exercise intensity seems to influence the affective responses in self-selected and imposed exercise: a meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2015;61105. [CrossRef]

- Rutter LA, Ten Thij M, Lorenzo-Luaces L, Valdez D, Bollen J. Negative affect variability differs between anxiety and depression on social media. PLoS One. 2024;19(2):e0272107. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira GTA, Costa EC, Santos TM et al. Effect of High-Intensity Interval, Moderate-Intensity Continuous, and Self-Selected Intensity Training on Health and Affective Responses. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2024;95(1):31-46. [CrossRef]

- Haile L, Goss FL, Andreacci JL, Nagle EF, Robertson RJ. Affective and metabolic responses to self-selected intensity cycle exercise in young men. Physiol Behav. 2019;2059-14. [CrossRef]

- Collins D, Hale B, Loomis J. Differences in Emotional Responsivity and Anger in Athletes and Nonathletes: Startle Reflex Modulation and Attributional Response. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2017;17(2):171-184. [CrossRef]

- Dias MR, Simao R, Machado GH et al. Relationship of different perceived exertion scales in walking or running with self-selected and imposed intensity. J Hum Kinet. 2014;43149-157. [CrossRef]

- Wardwell K, Focht C, Courtney Devries A, O’connell A, Buckworth J. Affective responses to self-selected and imposed walking in inactive women with high stress: a pilot study. J Sports Med Physical Fitness 2013;53(6):701-712.

- Parfitt G, Rose EA, Burgess WM. The psychological and physiological responses of sedentary individuals to prescribed and preferred intensity exercise. Br J Health Psychol. 2006;11(Pt 1):39-53. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira A, Costa C, Santos T et al. Effect of High-Intensity Interval, Moderate-Intensity Continuous, and Self-Selected Intensity Training on Health and Affective Responses. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2024;95(1):31-46. [CrossRef]

- Ekkekakis P, Lind E. Exercise does not feel the same when you are overweight: the impact of self-selected and imposed intensity on affect and exertion. Int J Obes (Lond). 2006;30(4):652-660. [CrossRef]

- Matsudo S, Araújo T, Matsudo V et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire (lPAQ): Study of Validaty and Reliability in Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Atividade Física & Saúde. 2001;6(2):1-14.

- Foster C, Florhaug JA, Franklin J et al. A new approach to monitoring exercise training. J Strength Cond Res. 2001;15(1):109-115.

- Banister EW, Carter JB, Zarkadas PC. Training theory and taper: validation in triathlon athletes. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1999;79(2):182-191. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, Deslandes AC, Nakamura FY, Viana BF, Santos TM. Self-selected or imposed exercise? A different approach for affective comparisons. J Sports Sci. 2015;33(8):777-785. [CrossRef]

- Billat V, Renoux JC, Pinoteau J, Petit B, Koralsztein JP. Reproducibility of running time to exhaustion at VO2max in subelite runners. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1994;26(2):254-257. [CrossRef]

- Acevedo E, Ekkekakis P. Psychobiology of Physical Activity (Human Kinetics Publishers, 2006).

- MacInnis MJ, Gibala MJ. Physiological adaptations to interval training and the role of exercise intensity. J Physiol. 2017;595(9):2915-2930. [CrossRef]

- Hill DW, Poole DC, Smith JC. The relationship between power and the time to achieve .VO(2max). Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34(4):709-714. [CrossRef]

- Billat V, Renoux JC, Pinoteau J, Petit B, Koralsztein JP. Times to exhaustion at 90, 100 and 105% of velocity at VO2 max (maximal aerobic speed) and critical speed in elite long-distance runners. Arch Physiol Biochem. 1995;103(2):129-135. [CrossRef]

- Verame A, Santana W, da Silva CA, Barbosa E, Figueira Júnior A. Physiological and Psychoaffective Responses of Adults Trained in Acute HIIT Protocols. Rev Bras Med Esporte. 2024;30(1):1-5.

- Ganasarajah S, Sundstrom Poromaa I, Thu WP et al. Objective measures of physical performance associated with depression and/or anxiety in midlife Singaporean women. Menopause. 2019;26(9):1045-1051. [CrossRef]

- Mochcovitch MD, Deslandes AC, Freire RC, Garcia RF, Nardi AE. The effects of regular physical activity on anxiety symptoms in healthy older adults: a systematic review. Braz J Psychiatry. 2016;38(3):255-261. [CrossRef]

- Machado S, Telles G, Magalhaes F et al. Can regular physical exercise be a treatment for panic disorder? A systematic review. Expert Rev Neurother. 2022;22(1):53-64. [CrossRef]

- O'Connor PJ, Petruzzello SJ, Kubitz KA, Robinson TL. Anxiety responses to maximal exercise testing. Br J Sports Med. 1995;29(2):97-102. [CrossRef]

| Sample characteristics | Experimental group (Mean ± SD) |

| Age (years) | 43.3 ± 4.2 |

| Body mass (kg) | 68.3 ± 9.5 |

| Stature (cm) | 170.5 ± 8.3 |

| Training experience (years) | 5.4 ± 4.3 |

| Imposed | Self Selected | ||||||

| VO2Max | TLim | VPeak | T1000 | V1000 | |||

| (mL·kg-1·min-1) | (seg) | (km·h-1) | (%) | (seg) | (km·h-1) | (%) | |

| Mean | 51.1 | 220.7 | 14.3 | 100.0 | 284.8 | 12.9 | 90.0 |

| SD | 5.7 | 43.8 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 35.1 | 1.7 | 6.4 |

| TLim | T1000 | |||||||

| Pre | Post | Dif | ∆ % | Pre | Post | Dif | ∆ % | |

| Mean | 3.9 | 4.8 | 0.9 | 23% | 4.3 | 2.7 | 1.6 | -37% |

| SD | 0.9 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.4 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).