1. Introduction

In a small fraction of young stellar objects (YSOs) surrounded by disks, observations have discovered a low excess radiation in the near–infrared but a high excess in longer wavelengths. This has been interpreted as an evidence that these disks called transitional disks (TDs) have central holes which have practically no dust [

1]. More recently, disks showing a significant excess in the near–infrared have been discovered. Such an excess indicates the presence of an optically thick inner disk. This inner disk is separated from an outer disk which also has a high optical depth. In this way the spectral energy distribution (SED) suggests the incipient development of a gap between both disks, these disks are called pre–transitional disks (Pre–TDs) [

2]. Several physical mechanisms have been suggested to explain the gaps or holes in protoplanetary disks. The one implemented in this work is driven by forming giant planets.

A key element that produces characteristic features in the SEDs of protoplanetary disks is the outer wall of the gap or hole. To simplify SED wall models, it is often assumed that the wall is vertical and frontally irradiated by the central star [

2,

3]. But this assumption is physically wrong [

4]. For dust sublimation walls, located near from the star, it has been proposed that the wall is curved, where the dust grain growth and its fall into the mid–plane of the disk, and the gas density high–dependence on sublimation temperature are the physical mechanisms responsible for such curvature [

5].

In order to create synthetic SEDs of protoplanetary disks with gaps or holes having inner

curved walls, I have developed a computational code called

rhada

man

te. This code is based on an older code which suggests that the inner

vertical wall of the outer disk can explain the mid–infrared spectrum of the low–mass pre main–sequence star CoKu Tau/4 [

6].

To test the code, I present a model of a truncated dusty disk –a disk with an inner hole– that accounts for the Spitzer Infrared Spectrograph observations of the low-mass pre main–sequence star LkCa 15. In this model the mid–infrared spectral energy distribution (between 10 and 25µm) arises from the inner curved wall of the gap in the disk.

1.1. Dust in Protoplanetary Disks

Dust is a pretty important component of protoplanetary disks surrounding young stars. The growth of dust grains from sizes of microns to centimeters or larger grains is the first step in planet formation.

The dust grains in protoplanetary disks follow a size distribution based on a single power law

[[

7], MNR], where the maximum dust size,

, the minimum dust size,

, and the power law index,

p, are different for each grain species.

The dust composition in protoplanetary disks has been extensively studied through mid-IR observations. This dusty mixture includes silicates (mainly), carbonaceous grains, poly-cyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and sulfide-bearing grains [

8].

Silicate grains are the best understood dust component. The most abundant crystalline silicates are olivine, which is magnesium-rich (Fo90), and pyroxene. Olivine series range from forsterite, Mg2SiO4 (denoted as Fo100), to the fayalite, Fe2SiO4 (denoted as Fo0). While pyroxene series range from the enstatite, MgSiO3 (denoted En100), to the ferrosilite, FeSiO3 (denoted En0).

Modeling of the observed spectra expects amorphous silicate grains to exist in protoplanetary disks [see, e.g. [

9]; [

10]]. The composition of these grains are glass with embedded metals and sulfides, and series ranging from ferromagnesian silica to Fe–Mg-bearing aluminosilica. These grains are difficult to observe directly from infrared spectroscopy. Their spectral signature observed is a combination of grain composition, shape, size, and structure, making difficult to isolate the pure amorphous silicate signal.

Carbonaceous grains, including amorphous and graphite elemental carbon, are difficult to detect in the infrared. However, grain modeling suggests these grains are needed in order to explain the observed infrared spectra of protoplanetary disks [

9].

Nano–diamonds, from sizes of <1 nm to ∼ 10 nm, are found in protoplanetary disks. Diamond emission coming from the inner region of the disk (i.e. < 15 AU) at 3.43 and 3.53

m has been detected in disks [see, e.g. [

11]].

The presence of poly-cyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) has been detected in the surface layers of some protoplanetary disks [see, e.g. [

12]]. Disks surrounding higher-mass stars, such as Herbig stars, show more PAHs emission [

13] than disks surrounding lower-mass stars, such as T Tauri stars [

14]. Protoplanetary disks with a flaring outer surface show significantly more PAH emission [

13]. It follows that PAHs exist in all disks, but they can only be detected, as infrared emission, when ultraviolet radiation from the central star is able to excite them. The discovery of weak PAH features in T Tauri stars supports this idea [see, e.g. [

14]].

Other dusty components in protoplanetary disks are iron-nickel sulfides grains (FeS, NiS) and water ice (H

2O). Sulfide emision around 23

m has been detected in the emission spectra of protoplanetary disks [

15]. While water ice emission has been identified at 3

m [

16], 44

m [

17], 60

m [

18] and 62

m [

19].

1.2. LkCa 15

LkCa 15 is a K5-type [

20] T Tauri star located in the nearby (

) the Taurus-Auriga Star Forming Region [

21]. The mass of the central star is

[

20], it has an effective temperature of 4370K [

22] and a radius of

[

23]. Three planet candidates have been detected: LkCa 15

b (semi major axis

) [

24], LkCa 15

c (

) and LkCa 15

d (

), with masses lower than 5–10

, for the two first planets, and

for the third one [

25].

Observations of the far-ultraviolet (1100–2200Å) radiation field and the near–to mid–IR (3-13.5

m) spectral energy distribution of LkCa 15, from the

Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) indicate the existence of an inner disk gap of a few astronomical units [

26].

LkCa 15 has an inner disk, a gap and an outer disk [

27]. Using the

Spitzer data, LkCa 15 has been classified as a pre-transitional disk [

28], and it has been showed that the inner hole is not devoid of dust between 0.1 and 5 AU. The outer disk extends from 46 to 800 AU [

29].

Recent observations from Gemini NIRI suggest that a single massive planet would be capable of opening a gap as large as the one observed in the LkCa 15 disk [

22]. This assumption leads me to use a mass of ∼

for the planet candidate in the current work.

Models of the LkCa 15 disk SED show that the inner edge of the disk has a radius of ∼58 AU [

23]; this outer disk has a mass of ∼

[

30].

2. Geometry of the Wall Projected on the Sky

To find the two–dimensional geometry of a wall gap, I implement the

arte

mi

se code [

4]. Which is a computational and geometrical code that analyses a tri–dimensional simulation of the disk–planet interaction by considering the wall is located at the points

where the disk optical depth is

. Simulations are done with

fargo-3D code [

31] under some specific parameters of the young stellar object to be studied.

2.1. Inclined Walls

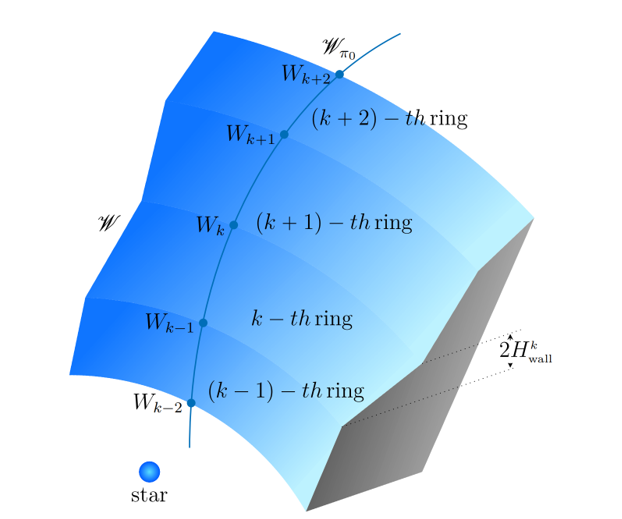

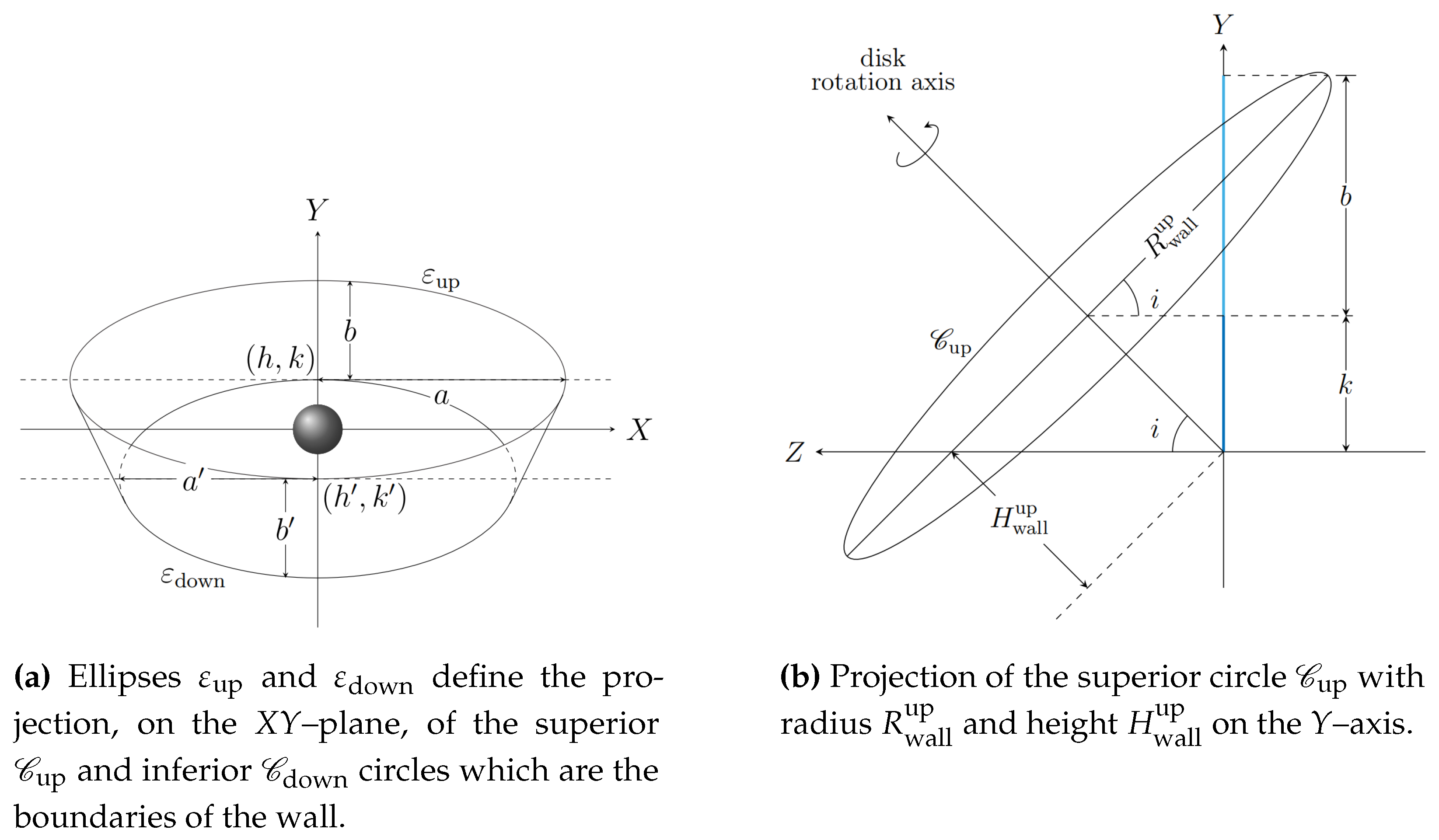

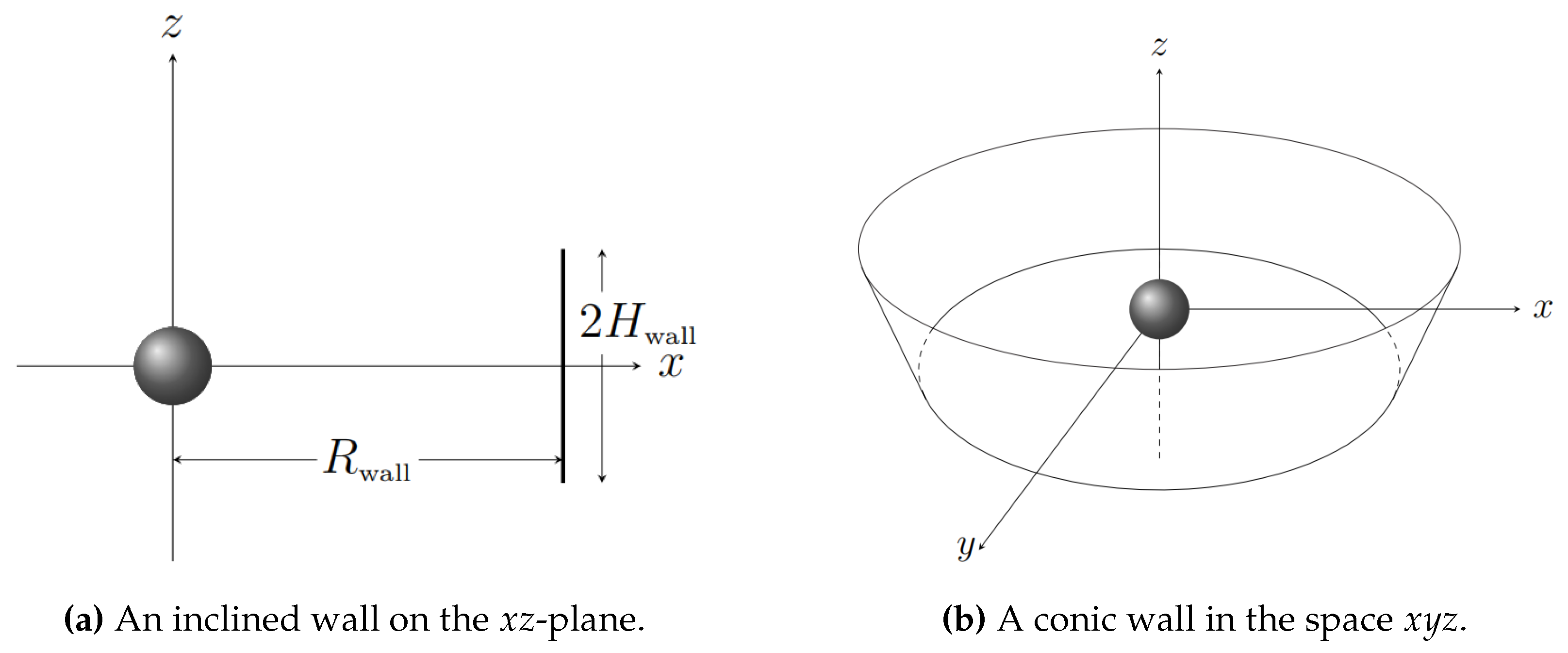

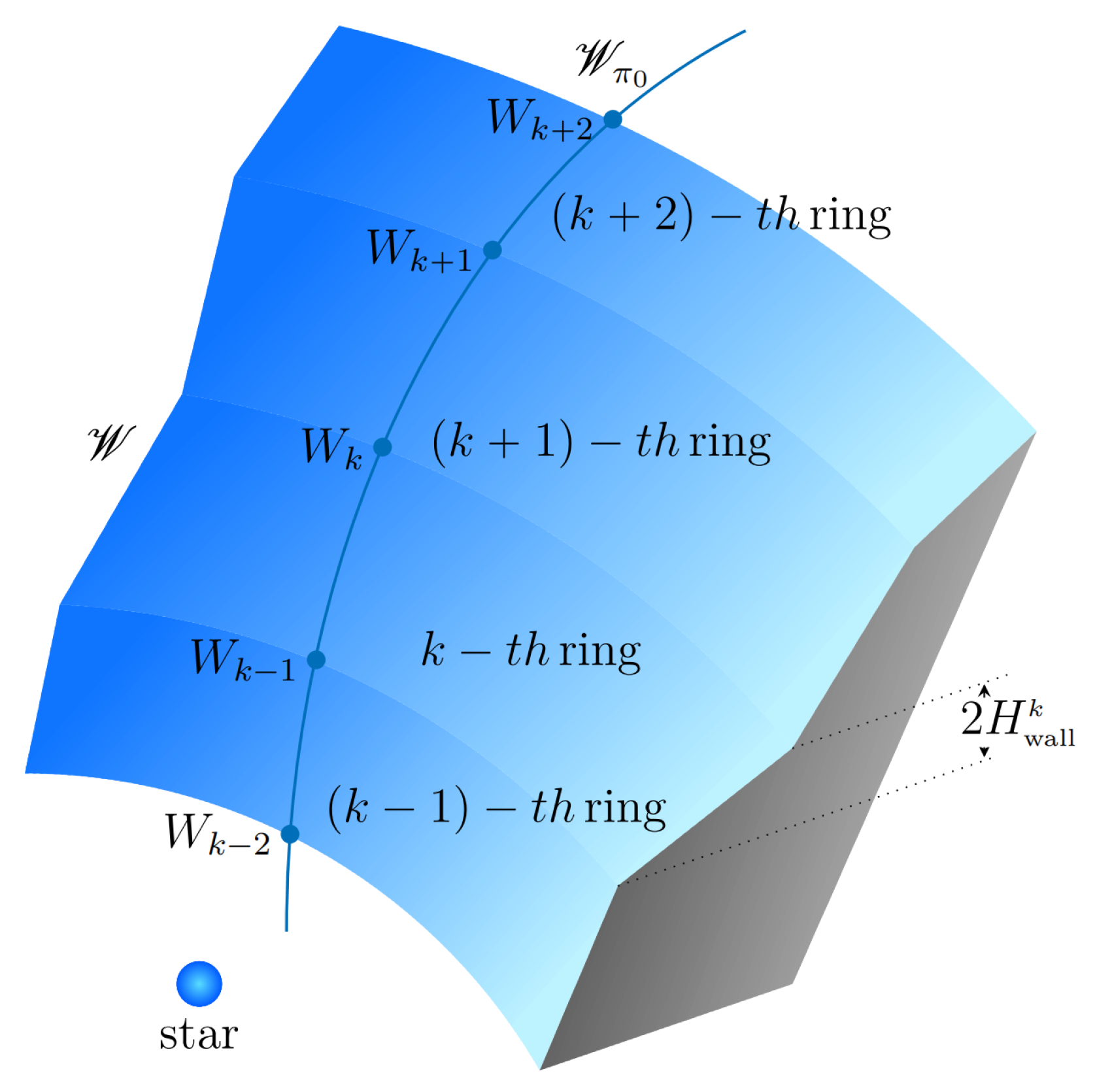

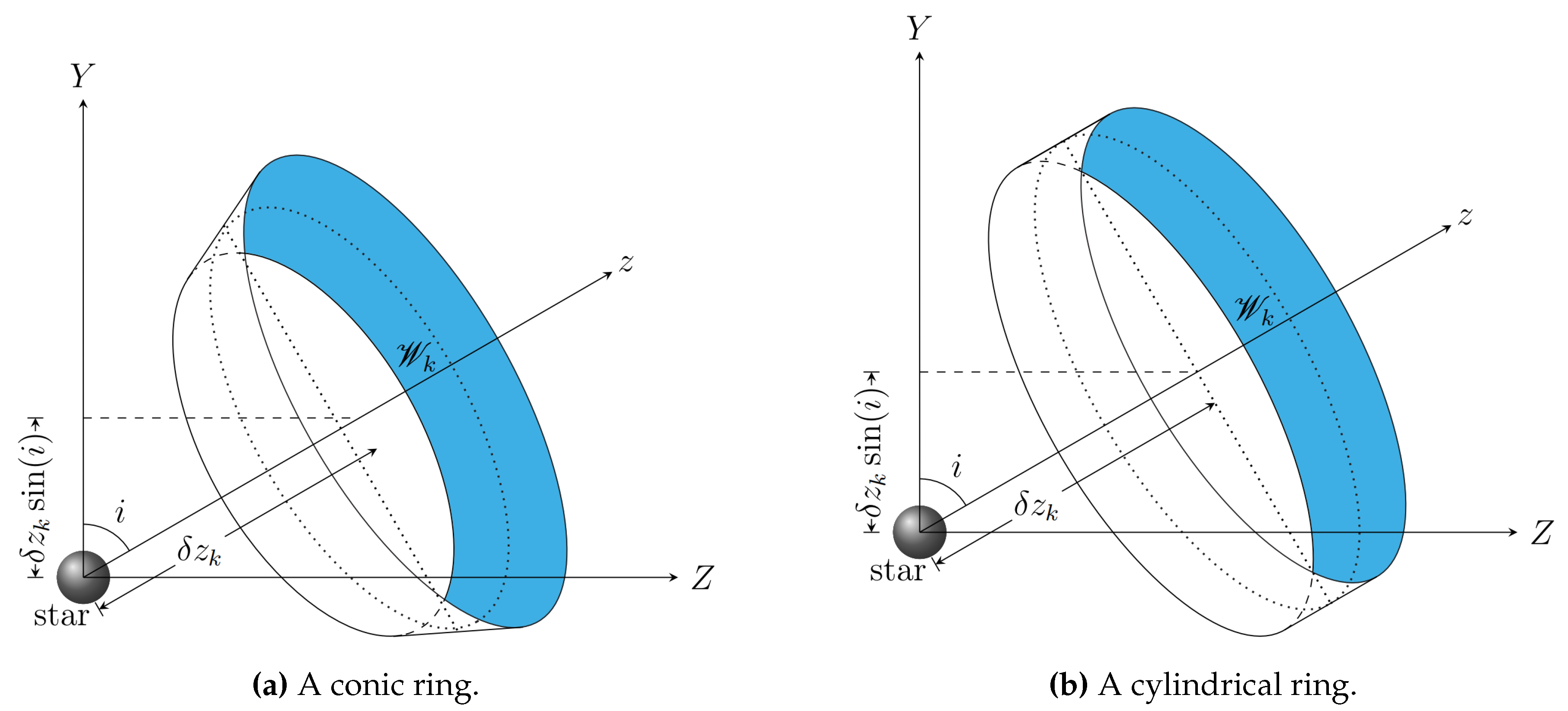

Definition 1. An inclined two–dimensional wall is a line segment with boundaries and , with and , as seen in Figure 1a. By rotating this line segment around z–axis, a conic ring lying in the Euclidean space , is obtained, as seen in Figure 1b. This ring is the tri–dimensional conic wall.

In the coordinate system

the star is centered at the origin, here

z–axis is the disk rotation axis, and the plane

is the disk mid–plane. For simplicity, I also consider the cylindrical coordinate system

, such that all points on the wall superior boundary have coordinates

z,

y

, whereas all points on the wall inferior boundary have coordinates

z,

y

. Since the protoplanetary disk is assumed to be projected on the plane of the sky

, as seen in

Figure 2, I consider a third coordinate system

also centered at the star, where the

Z–axis is the line of sight. When the disk is face–on the coordinate systems coincide. There exists a transformation between the three coordinate systems:

where

i is the disk inclination angle, that is, the angle between the

z–axis and the plane of the sky

.

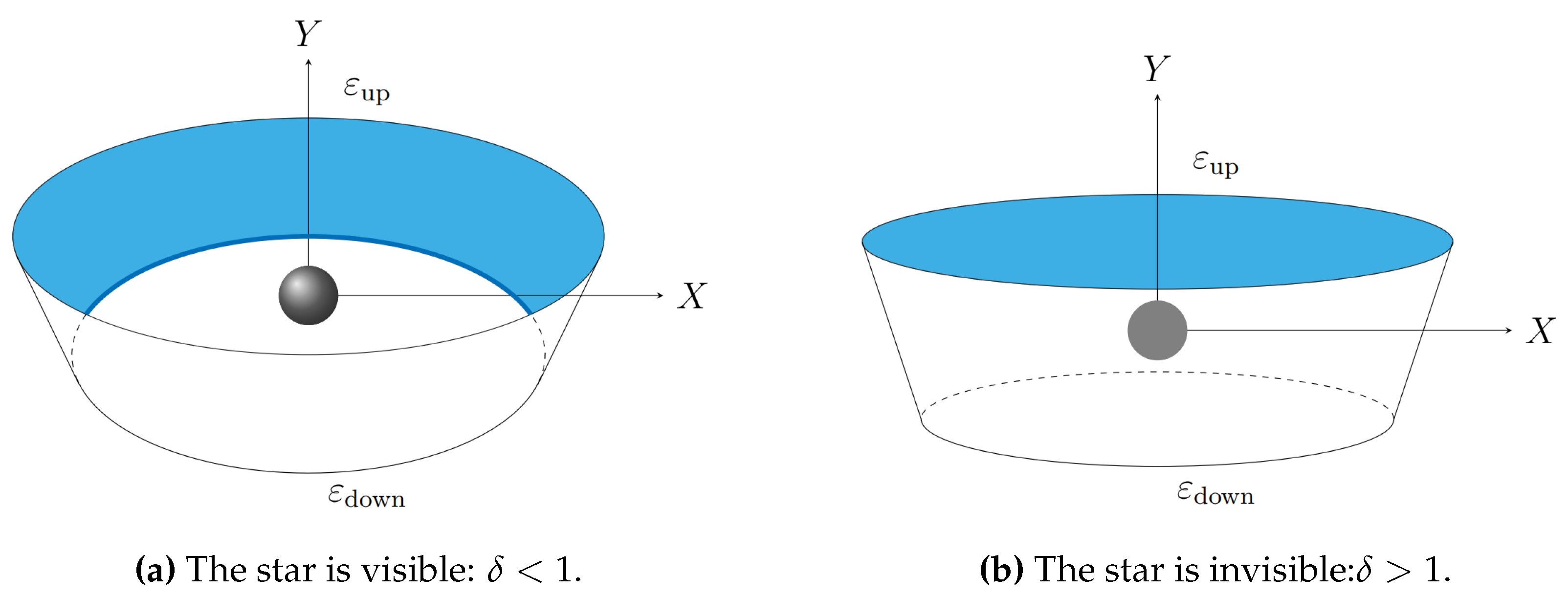

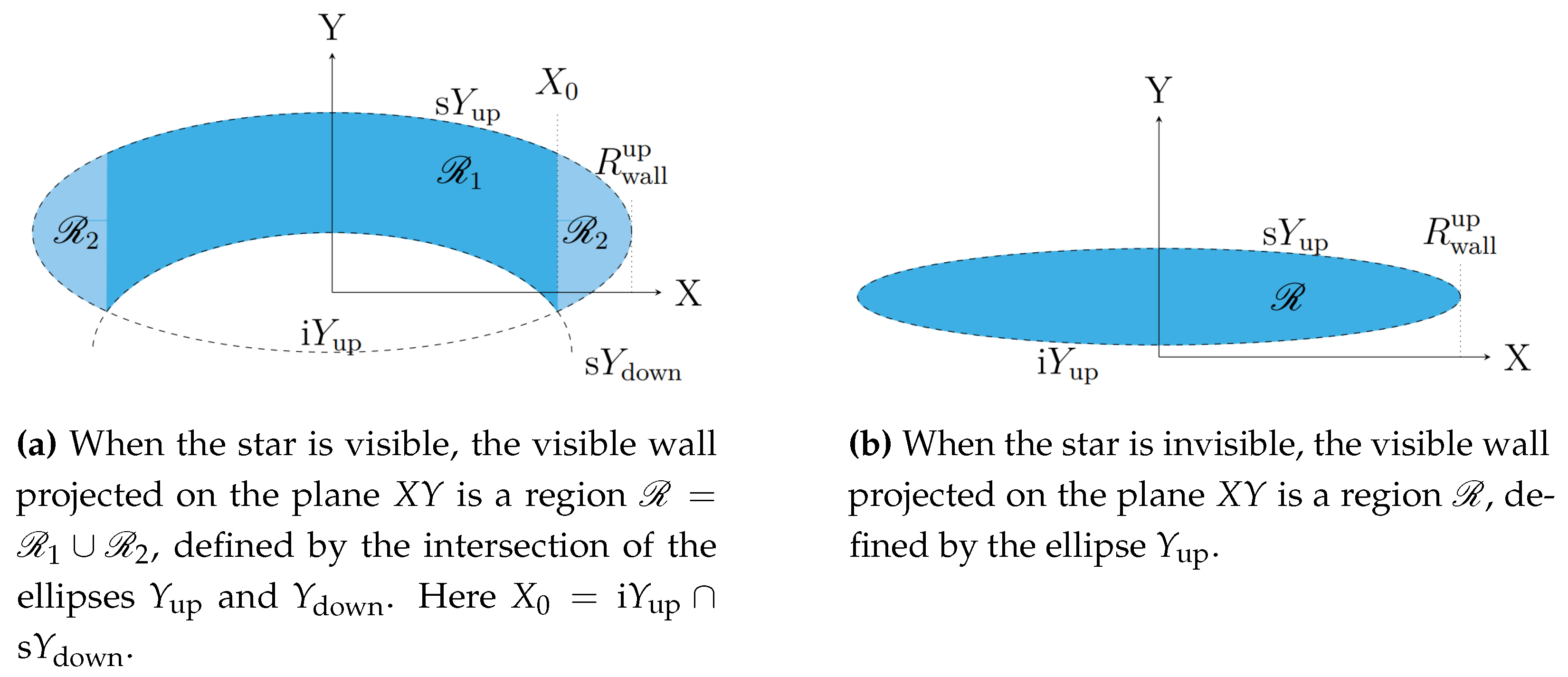

The amount of visible surface of the wall, projected on the plane of the sky, depends on the disk inclination angle, and there are two possibilities: (

i) when the star is visible (corresponding to

, see Equations (

4) and (

9) for a definition of

), and (

ii) when the star in invisible (corresponding to

, as seen in

Figure 2. A surface element of the visible area is

, with

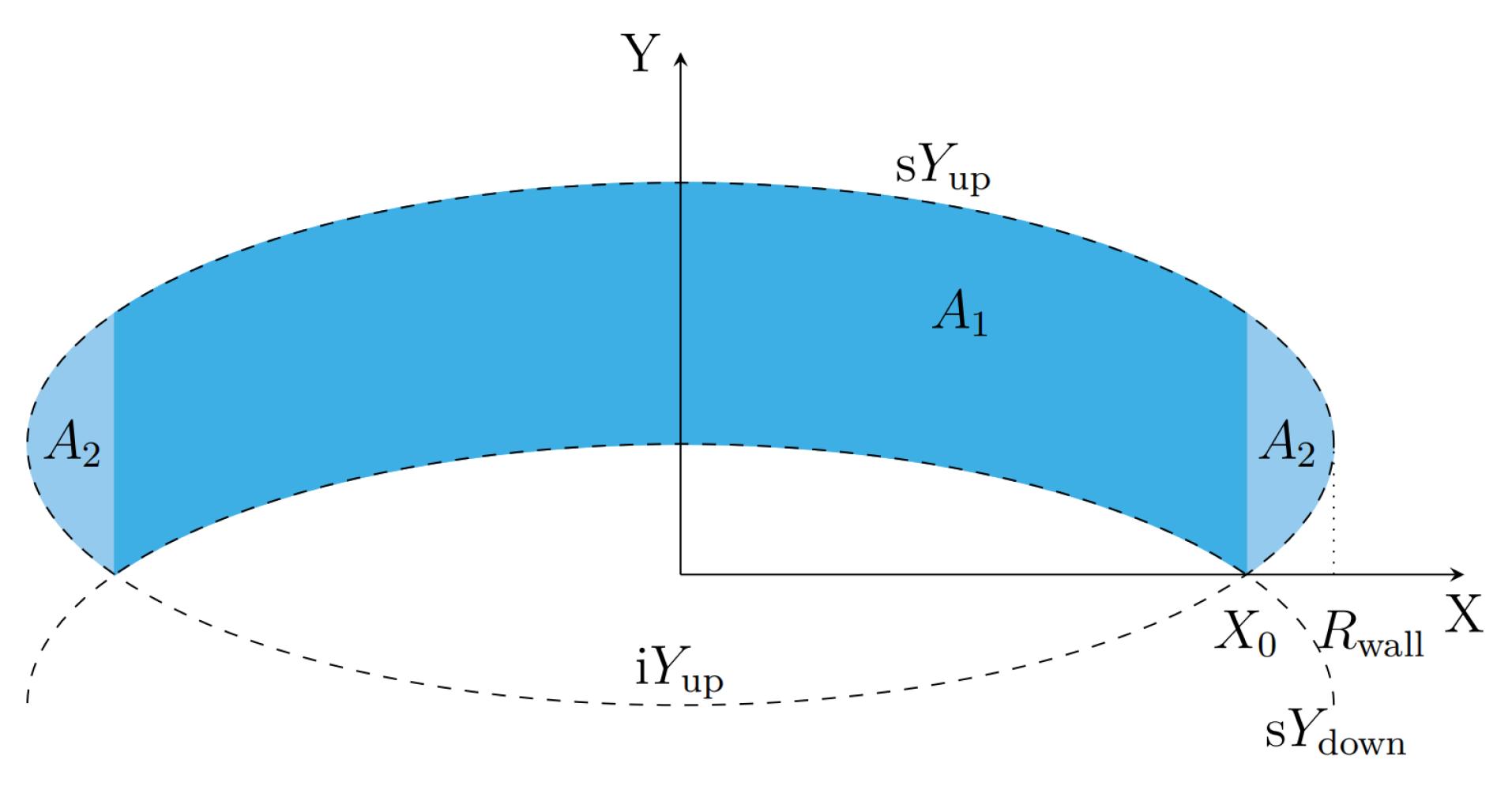

.

Let

be the visible surface of the wall projected on the plane

for both cases, as seen in

Figure 3. Then the boundary of this region is defined by two ellipses

and

(see

Appendix A.1) given by the projections of the up and down edges of the tri–dimensional conic wall. The up ellipse

is defined as

, where

and

are the superior and inferior parts of this ellipse, respectively, such that

Similarly, the down ellipse

is defined as

, where

and

are the superior and inferior parts of this ellipse, respectively, such that

Ellipses

and

intersect at critical angles

y

, where

is given by

Depending on the wall inclination angle

i, there exist two possibilities to know whether both ellipses can intersect: if

or not if

, as seen in

Figure 3.

For the case , the region is composed by two sub-regions and :

where

:

and where

:

that means

(see Appendixes

Appendix A.3 and

Appendix A.4).

For the case

, the region

is defined as follows

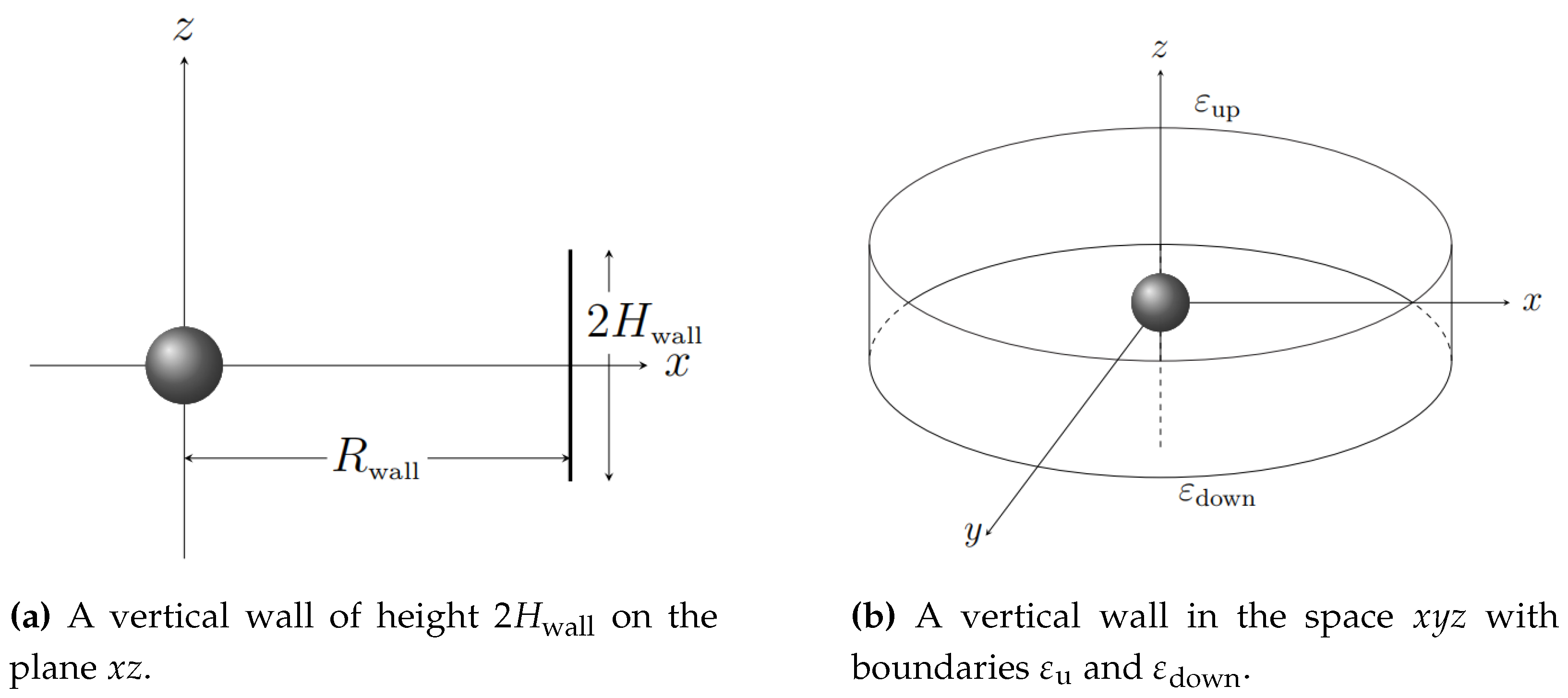

2.2. Vertical Walls

If in Definition 1 I set

, I obtain a two–dimensional vertical wall, as seen in

Figure 4a. By rotating this line segment around

z–axis, I generate a

cylindrical ring which lies in the Euclidean space

, as seen in

Figure 4b. This ring is a tri–dimensional

cylindrical wall.

Following the same mathematical procedure as in the case of an inclined wall, I obtain that

where

Both ellipses intersect at critical angles

y

, where

is given by

3. The RHADaMAnTe Code

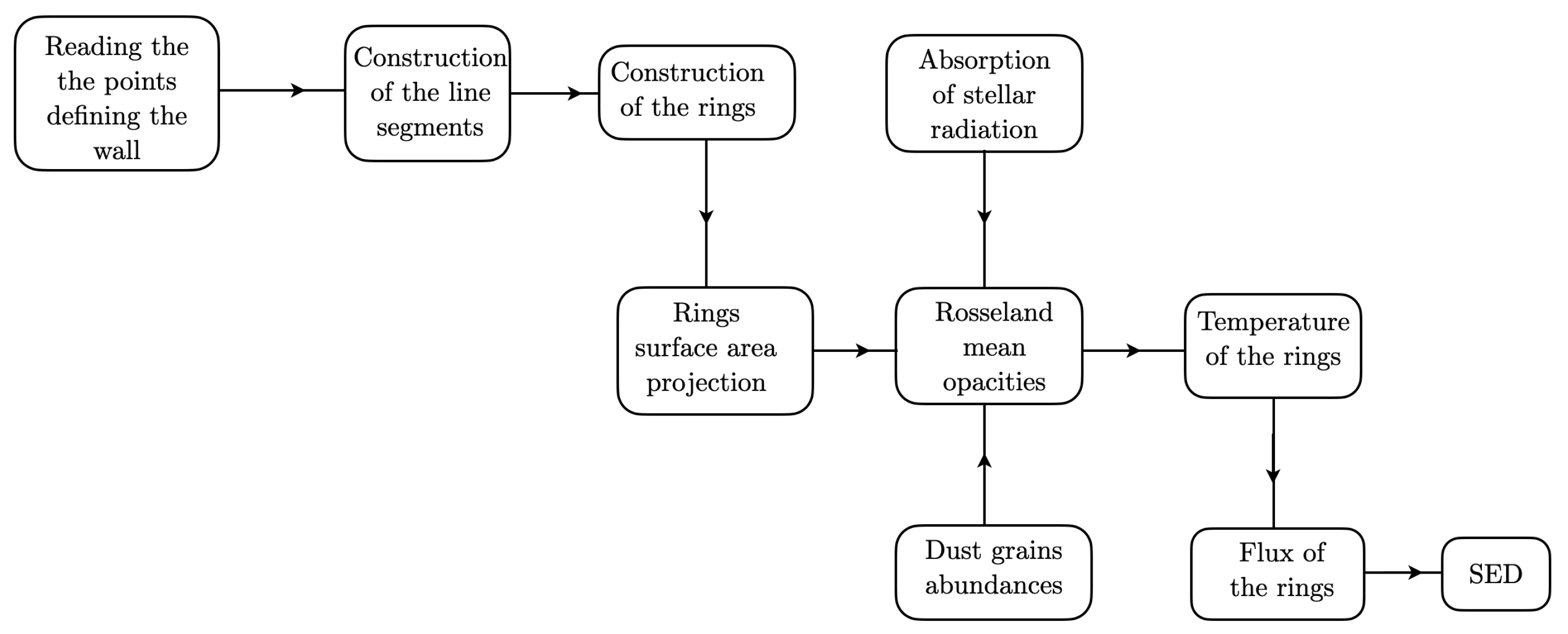

To create synthetic SEDs as arising from the inner curved wall of a gap or hole open by a planet in a protoplanetary disk, I have developed a computational code, written in the fortran 90 language, called rhadamante. This code is coupled to the artemise code because the geometry of the wall is required.

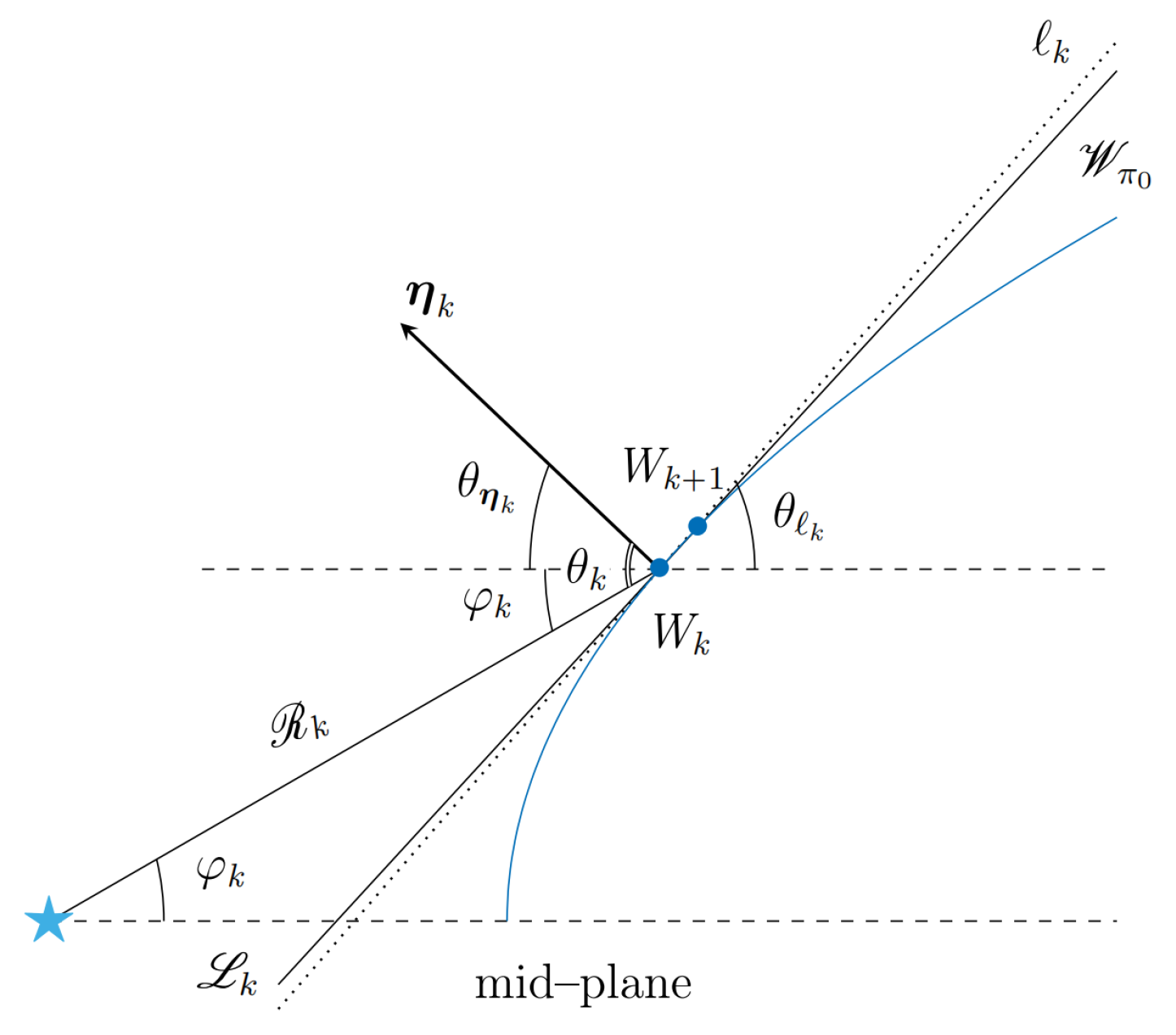

As I am interested in estimating the radiation reemitted by a tri–dimensional wall

projected on the plane of the sky, in this code, I firstly calculate the angle between the radial ray and the normal to the two–dimensional wall

for each incident radial radiation ray coming from the central star, as seen in

Figure 5, by applying an algorithm also called

RHADaMAnTe.

Then, I construct the tri–dimensional wall as the finite union of tri–dimensional conic rings obtained by rotating inclined line segments about the

z–axis at different heights. (see

Figure 6a and

Figure 7).

Next, I calculate the surface projection on the plane of the sky of these rings, and then I calculate the radiation emitted by each of them by implementing some ideas from an algorithm developed for vertical walls [

6]. Finally, I sum the contribution of the emission of all the projected rings to create a synthetic SED.

3.1. Geometry of the Radiation Reemitted by the Wall

rhada

man

te, acronym for

Radial Geom

etry Algorit

hm for C

alculati

ng the Ra

di

ation E

mitted by a W

all), it is a geometrical algorithm which at first calculates the angle between the stellar radiation along a radial ray

and the normal to the two–dimensional wall

, as seen in

Figure 5. Secondly, this algorithm discretizes the two–dimensional wall, which is not continuous, as seen in

Figure 6a.

Let

be the angle between the normal

on the point

belonging to the wall

, and the stellar radiation ray

, such that

where

is the minimal angle between the normal

and the mid–plane (

r–axis), and

is the angle between the ray

and the mid–plane, as seen in

Figure 5.

The angle is required to calculate the reemitted stellar radiation by the wall. Because of wall’s curvature and the radial geometry of the stellar radiation, each parcel of the wall does not absorb the total radiation, as it is in the case of vertical walls. In this case, each parcel absorbs only a fraction of the radiation which depends on the .

Let

be the tangent line to the wall

at the point

with a positive slope

. It follows that the inclination angle of such a line, measured from the

r–axis, is

, where

Physically, the wall

should be characterized by a mathematical continuous function. However, in this case, because of the numerical simulation, the wall is transfered, via the discretization process described in

Section 3.2, into a discrete counterpart. So, as the points

with

defining

are close enough, it is possible to find an approximation of its derivative.

Consider the points

and

in the wall

to be connected along the segment line

(as seen in

Figure 5), then the slope

of this line approximates to the derivative with respect to

r of

at the point

, that is

Hence .

Next, since the line

is almost perpendicular to the normal

, it follows

Finally, since the star is located at the origin of coordinate system, it is easily to calculate the angle between the ray

and the mid–plane

where

and

are the

r and

z coordinates of the point

.

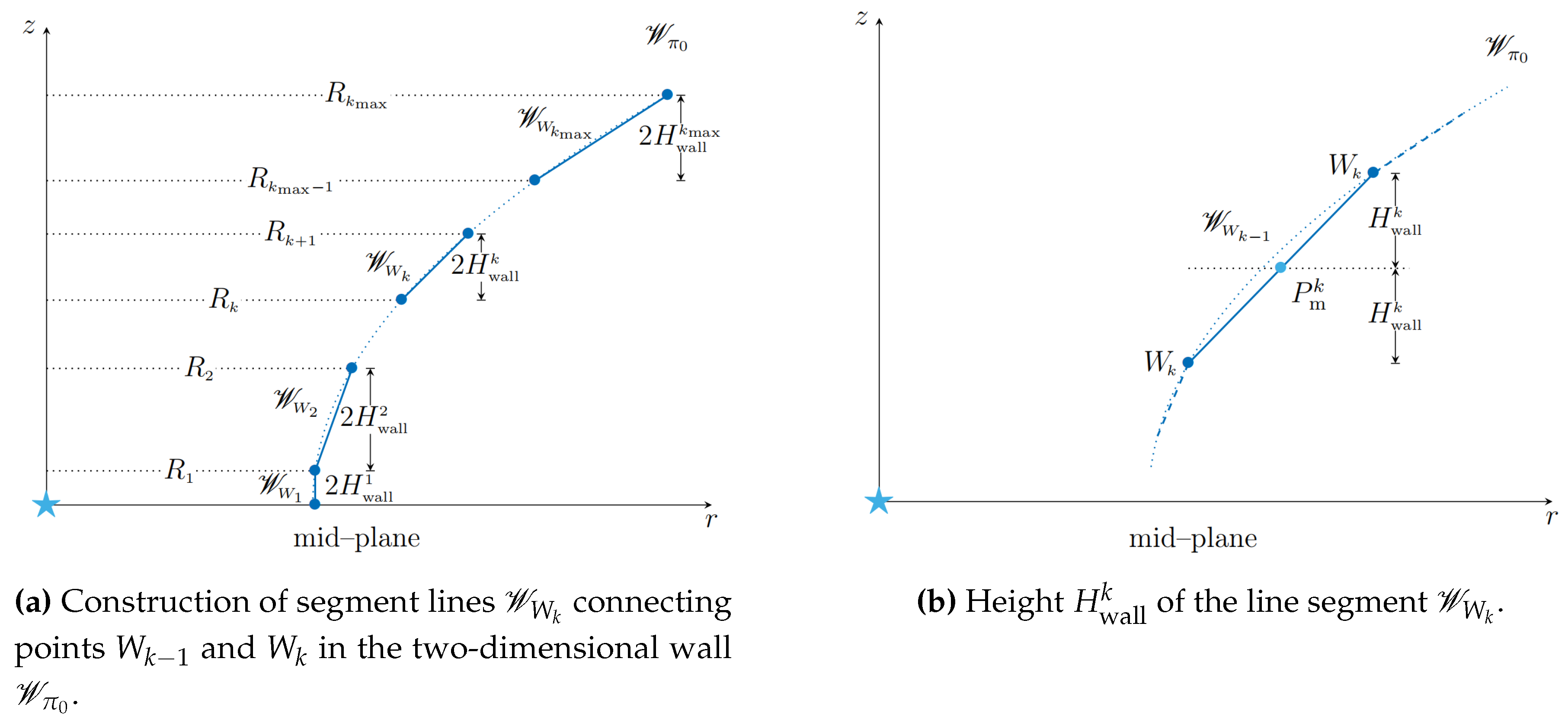

3.2. Discretization of the Two–Dimensional Wall

By applying the

ARTeMiSE algorithm, I obtain a set of points

with

, defining the two–dimensional wall

. It means that the wall is not a continuous curve. Then I discretize the wall as the finite union of infinitesimal inclined walls:

I connect each couple of points and by inclined line segments with height , as seen in Figure 6.

Consider an inclined line segment

with boundaries

and

in the wall

, and let

be the mid–point of

. As I require that the vertical height of this line segment to be

, I define

where

and

are the

z coordinates of

and the mid–point between the points

and

. See

Figure 6.

If , I construct a vertical line segment with boundaries and , and height , which conects to the mid–plane.

3.3. Curved Wall

Let be a two–dimensional wall discretized by infinitesimal inclined line segments for , and a vertical line segment .

By rotating each inclined line segment around

z–axis, one generates a conic ring

with minimum radius

, maximum radius

and total height

. Whereas, by rotating the vertical line segment, a cylindrical ring with radius

and total height

, is obtained. It follows the tri–dimensional curved wall can be defined as the finite union of a cylindrical ring and several conic rings:

. See

Figure 7.

3.3.1. Projection on the Plane of the Sky

The wall

has to be projected on the plane of the sky

to calculate the amount of visible surface. Therefore I consider the coordinate system

, where

Z is along the line of sight, such that

Since I want to apply the same algorithms of projection described in

Section 2.1 and

Section 2.2, it is required to do a geometric translation of each ring

to a secondary coordinate system

such that the translated ring

is centered at the origin. Easily I can say that there exists a translation transformation

:

where

is the displacement of the ring along

z–axis, to be centered at the origin of the system

, see

Figure 8, with

is the

z coordinate of the point

and

.

Applying this translation, it is possible to use the coordinate system

to project the ring

on the plane

:

From Equations (13), (14), and (15) it follows that there exists a translation transformation

, such that:

where

is the projection on the

Y–axis of the displacement of the ring along the

z–axis, as seen in

Figure 8.

Combining Equation (16) with Equations (2) and (3), it follows that for the

k–th conic ring

Whereas, for the cylindrical ring, by combining Equation (16) with Equation (8), it follows

3.4. Emission of the Wall

To calculate the emission or emergent flux

of the visible wall projected on the plane of the sky, I multiply the total emergent intensity

by the solid angle

of the visible surface of the wall, whose geometry has been described in detail in

Section 3.3.

For each element in the visible surface of the projected wall, the thermal emergent intensity, approximated as isotropic, is given by

[see [

6] for derivation], where

is the Planck function,

is the total mean optical depth at the disk frequency band, and

, with opacity

.

The wall temperature

is a function of the optical depth of the disk, and it is calculated as follows [see [

6] for derivation]

where

and

with

,

, and

is the mean albedo to the stellar radiation and

, where

is the stellar luminosity.

At a distance

d from the observer, the total solid angle is given by

with

for conic rings, and

with

for cylindrical rings.

3.4.1. Rosseland Mean Opacity

Equation (

19) requires the calculation of the opacity

. This dominant opacity depends on the chemical composition, pressure and temperature of the gas, as well as the frequency

of the incident light. This is a complex endeavour. The problem can be simplified by using a mean opacity averaged over all frequencies, so that only the dependence on the gas physical properties remains. In the current work, I use the Rosseland mean opacity, defined as

where

is the Planck’s function, and

T is the disk temperature [

32].

To calculate the total Rosseland mean opacity

, I consider that all the dust grains species exist and the mixture of dust grains is made of small and big grains. Using the previous assumptions I calculate the total Rosseland mean opacity as follows:

where

and

are the Rosseland mean opacities associated to the small dust grain size distribution and big dust grain size distribution, respectively. And

and

represent the abundances (dust-to-gas mass ratio) of the small and big grains, respectively:

here

represents a small fraction of the scale height of the disk, and

k is a factor which defines a smooth transition between small and big grains population [

33].

The monochromatic opacity

in Equation (

25) depends on the dust species in the mixture and their physical and chemical properties, such that it is calculated as the sum of the monochromatic opacity of each grain species:

where

and

are the sizes of the small and big grains, and

and

are the abundance and refraction index of the species. Here

q is running over the name of the species (e.g. silicates, organics, amorphous carbon, ice and troilite) in the dust composition of the disk. I calculate the monochromatic opacities using the Mie theory by implementing some modified routines of a code developed in [

6].

Summarizing, to calculate the emergent flux emitted by the curved wall, I have developed a computational code called

rhada

man

te. This code is based on the geometry of the wall calculated by the

arte

mi

se code. In

Figure 9 I show a flowchart of our code. For some tests, see

Appendix B.

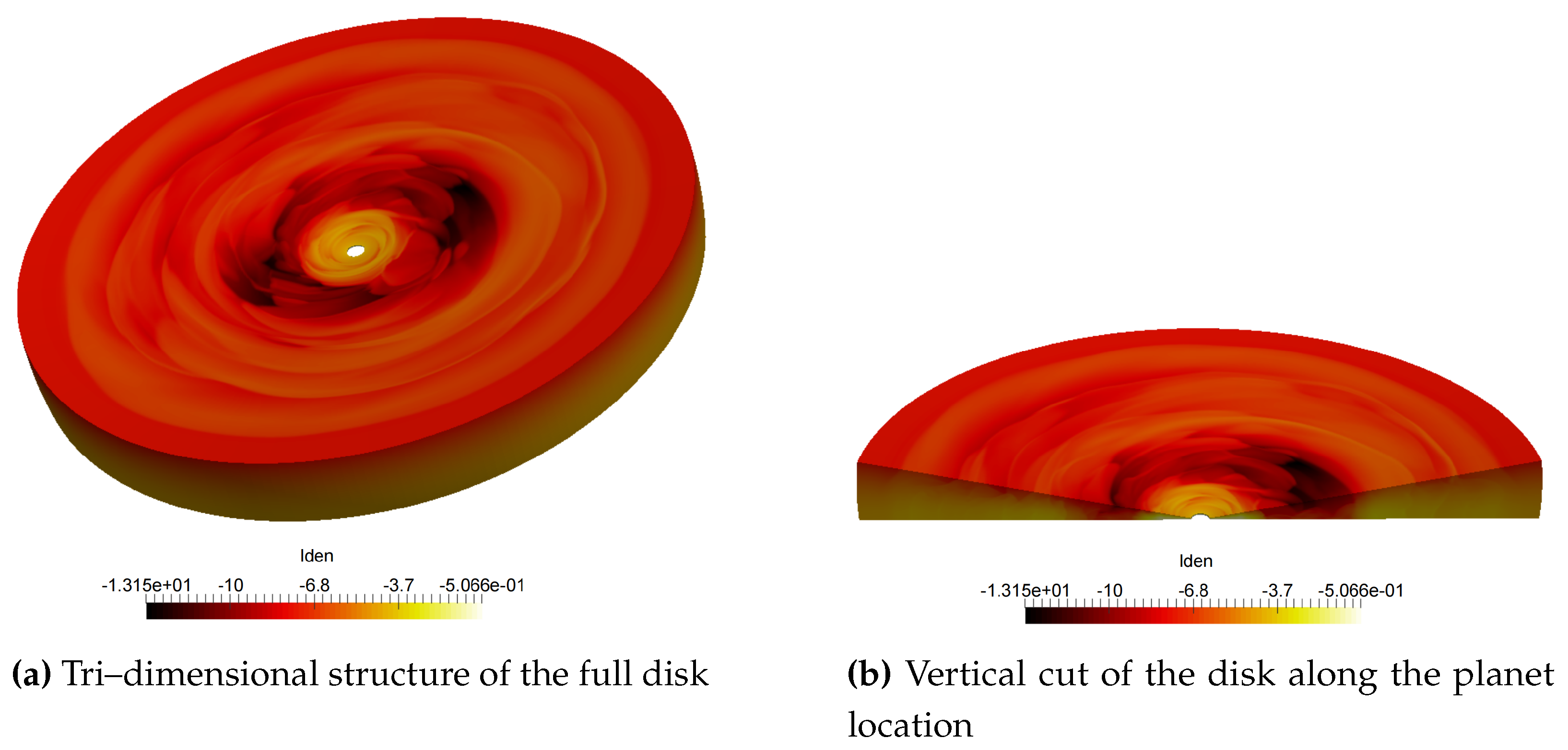

4. Results: An Implementation to the Stellar System LkCa 15

In this section, I present a model of the truncated dusty disk of the T Tauri star LkCa 15 that accounts for the Spitzer Infrared Spectrograph observations. I have modeled the mid–infrared spectral energy distribution from 5 and 40) as arising from the inner curved wall of the outer disk. In this model a mass planet is the responsible of the wall curvature. The free dust hole has a radius of ∼ along the mid-plane. The wall has a half-height of ∼ and it is illuminated at normal incidence by the central star, but it also is shadowed because of the presence of an internal optically thick disk.

4.1. Simulation: Planet–Disk Interaction

As I am interested in characterizing the geometry of the wall of the disk gap, in the LkCa 15 system, I need to analyze the vertical structure of the disk. Assuming the gap was opened by an embedded planet, I use the

fargo–3d hydro–dynamical code to launch two numerical simulations of the disk–planet interaction until the 500th. The only difference among these simulations is the size in resolution (

). The low resolution of

was used to find

quickly the orbit where the system reaches a quasi–stationary state. The medium resolution of

was used to get a better approximation of the wall. According to

fargo–3d requirements, in

Table 1 I show some parameters for simulations.

In

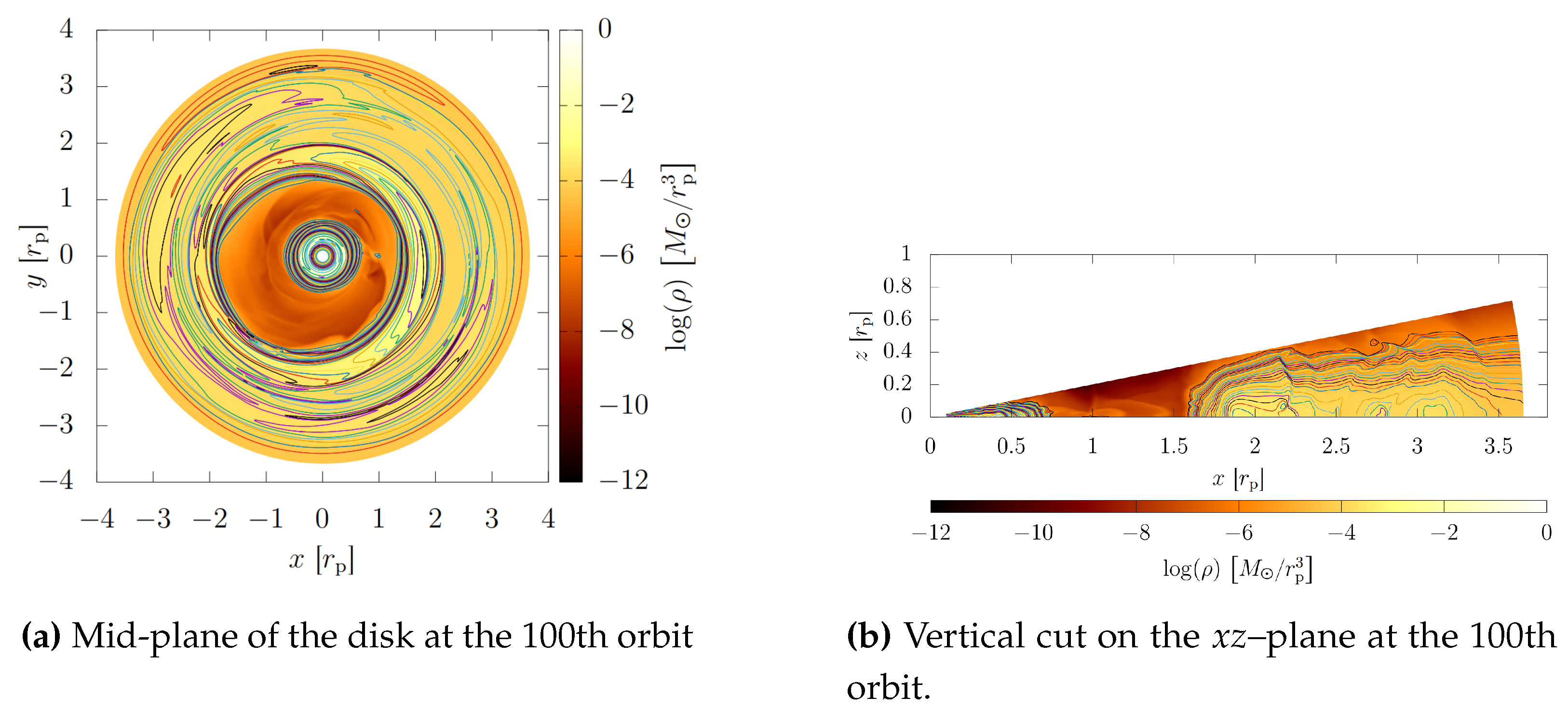

Figure 10, I present the tri–dimensional structure of the 100th orbit of the LkCa 15 disk simulation. It is here where the system reached a stationary-state.

In

Figure 11, it can be observed an optically thick inner disk and the gap completly opened. The planet is located at the point

as seen in

Figure 11.

4.2. Dust Grain

The optical depth of the disk depends on the disk material opacity, I assume that the disk is a mixture of grains composed of silicates with mass fraction

, organics with

, and troilite with

, consistent with the model proposed in [

34]. The grains are assumed to be spheres, which obey the standard MRN grain size distribution

[

7].

I consider two grain populations:

small grains between minimum radius

and maximum radius

, and

big grains between minimum radius

and maximum radius

. I consider a smooth transition between both dust populations, see Equation (27) in

Section 3.4.1, where I set

,

and

and

. I use optical constants for silicates from [

35,

36] and [

37], for the organics from [

34] and for troilite from [

34] and [

38]. I also take into account the sublimation temperature of the grain species in the mixture

,

, and

.

For the composition of the silicate dust grains, I considered several possibilities as showed in [

39]: amorphous Mg–Fe glassy olivine (

) and glassy pyroxene (

), where the subscripts to each element represents the fraction of the silicate composed of that element, with optical constants from [

36].

4.3. The Vertical Geometry of the Wall

I found that the

mass planet candidate, when is located at

from the central star, opens a gap around the young transitional disk host LkCa 15. The

arte

mi

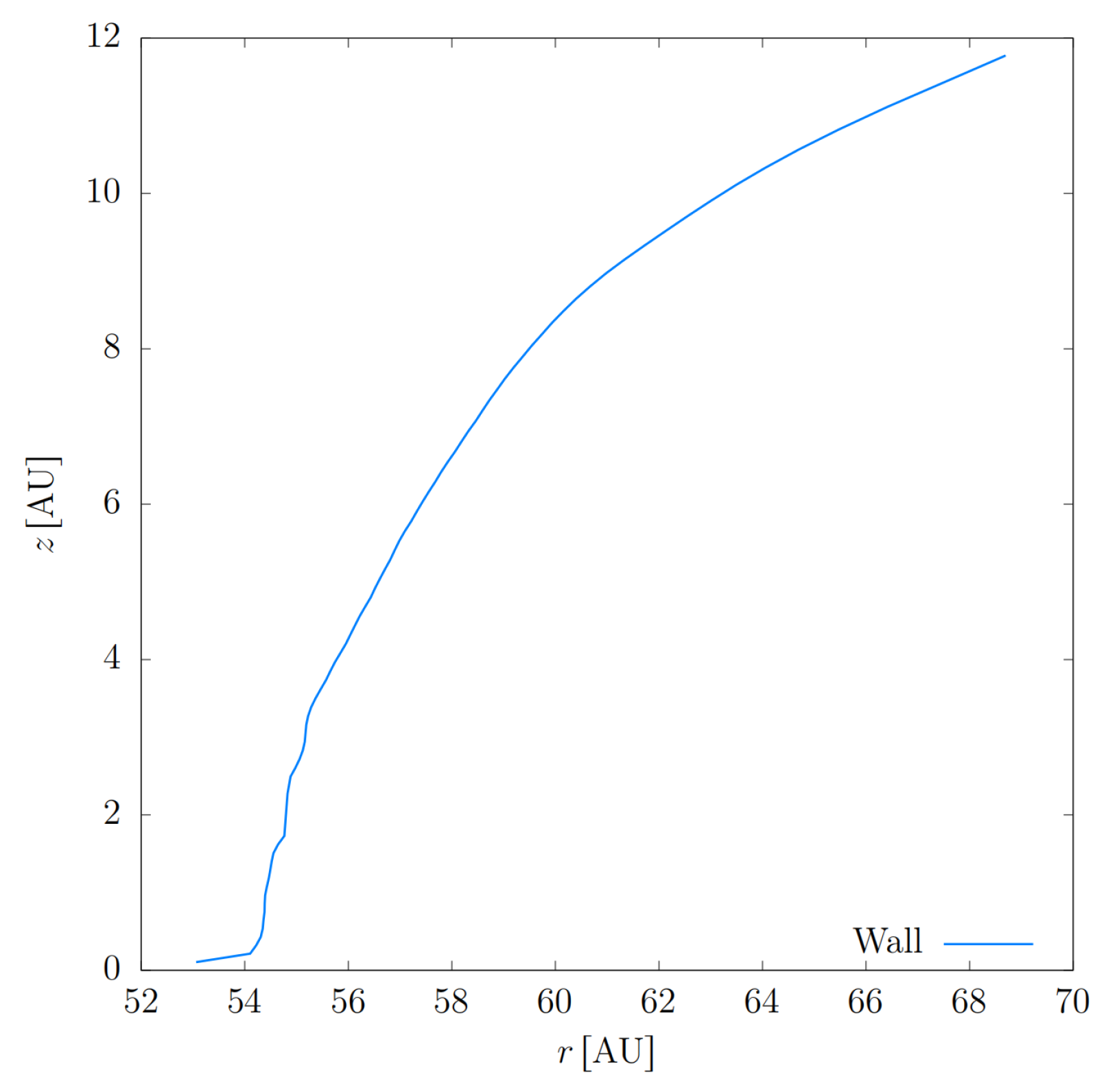

se code was implemented to analize the simulation data. The radii of the wall along the mid–plane of the disk and the heights of the wall have a deppendence on the chemical composition of the silicate grains as showed in

Table 2. In

Figure 12, I show the geometry of a wall where the dust garin disk composition has glassy olivine (silicate) with 50%Fe and 50% Mg.

The location of the planet candidate is not consistent with the observations [e.g. [

25], which suggest that the possible massive planets LkCa 15

b and LkCa 15

c are located at

and

, respectively, along the semimajor axis. However, the radii of the wall along the mid–plane

are similar to those measured in [

40,

41], ∼

, and [

22],∼

.

4.4. SED of the Wall

I model LkCa 15 as a central star with the properties described in

Section 1.2, surrounded by an optically thick inner disk (as showed in

Figure 11) and and outer disk truncated at ∼

. I consider the gap has a curved wall at differentent locations and heights according to

Table 2. In the models, I consider that LkCa 15 is at

from Earth in the Taurus-Auriga star forming region [

21] and the disk inclination is

[

25]. A representation of the model is showed in

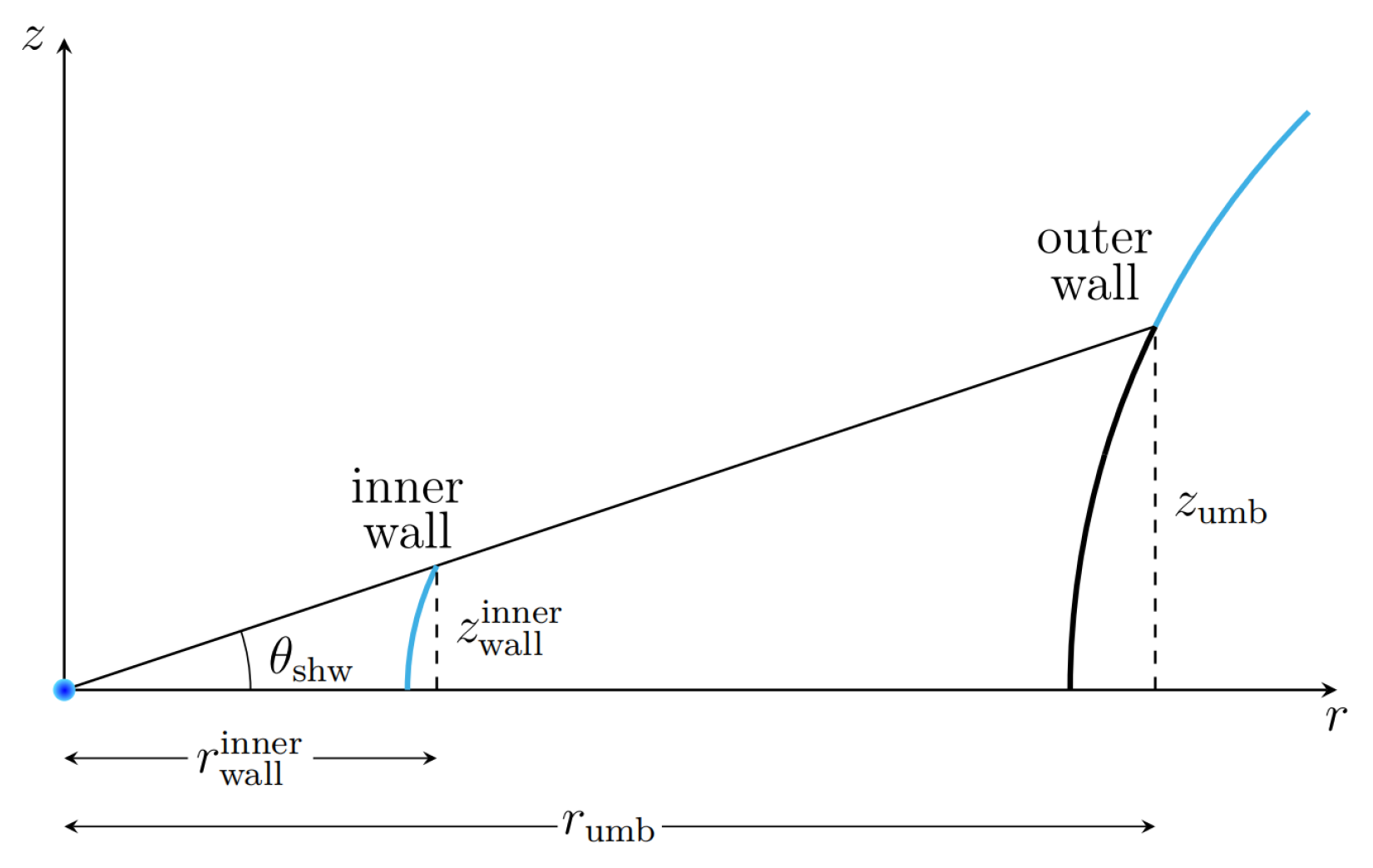

Figure 13.

As the inner disk casts an umbra over the wall of the outer disk, as seen in

Figure 13, I have to remove it from the SED of the outer disk wall. In order to find

, I implement some improved routines developed in [

42] for curved sublimation walls. This code uses opacities to calculate the shape of the wall and assumes that the stellar rays are parallel to the mid–plane. I found that the wall of the inner disk starts at ∼

, from the central star, and runs until ∼

where it reaches ∼

in height. And the temperature of the sublimation wall decreases with radius and it ranges from

to

.

In a first approximation, assuming the star as a point, the sublimation wall produces only an umbra over the wall of the outer disk (see

Figure 13). To calculate the size

of this umbra, theangle

subtended by the height

of the sublimation wall is needed. In addition, for some points

in the outer wall, I calculate the angle

until it reaches the value

.

Applying the previous algorithm to the geometry of the wall (see

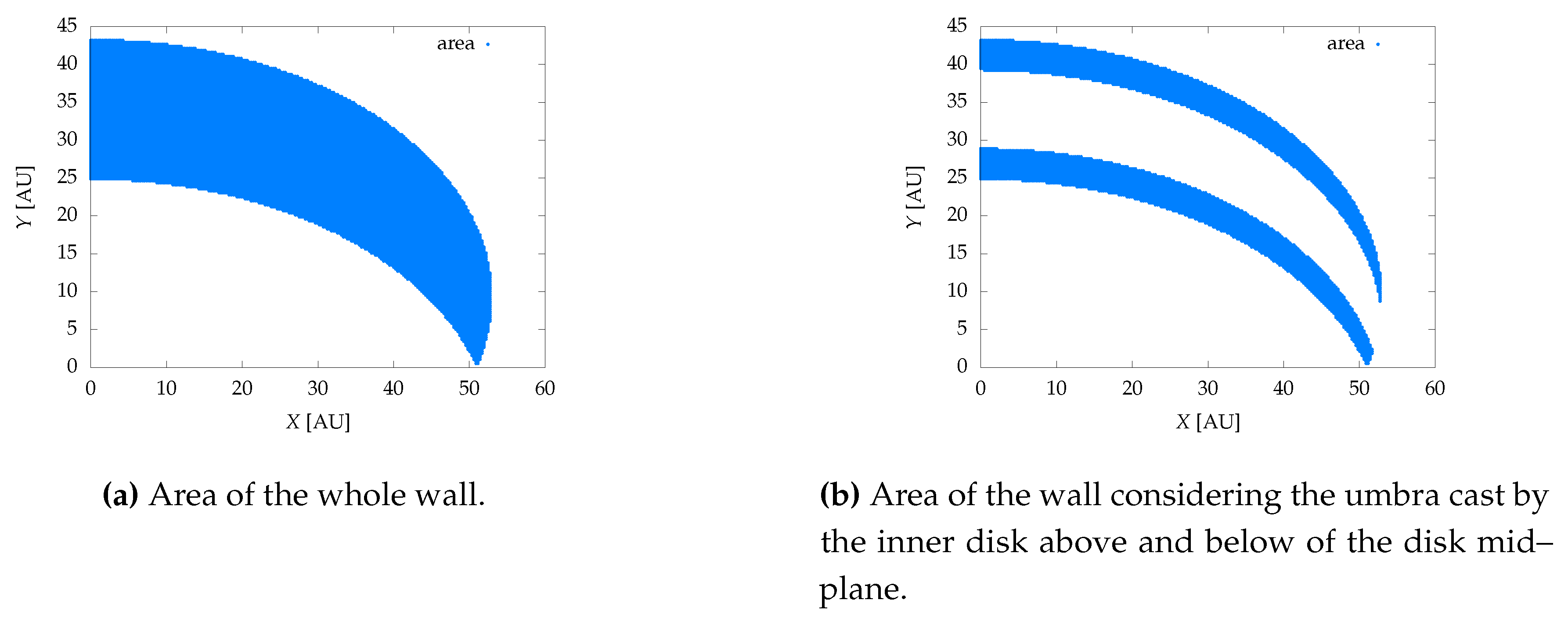

Figure 12), I found that the umbra produced by the sublimation wall of the inner disk onto the wall of the outer disk is

in height (above and below the disk mid–plane). It means the contribution to the SED of the outer wall comes from a region of the wall from ∼

to ∼

along the radial direction, and from

to

along the vertical direction. In

Figure 14a I show the surface area of the whole curved wall, and in

Figure 14b I show the surface area considered the umbra cast by the inner disk.

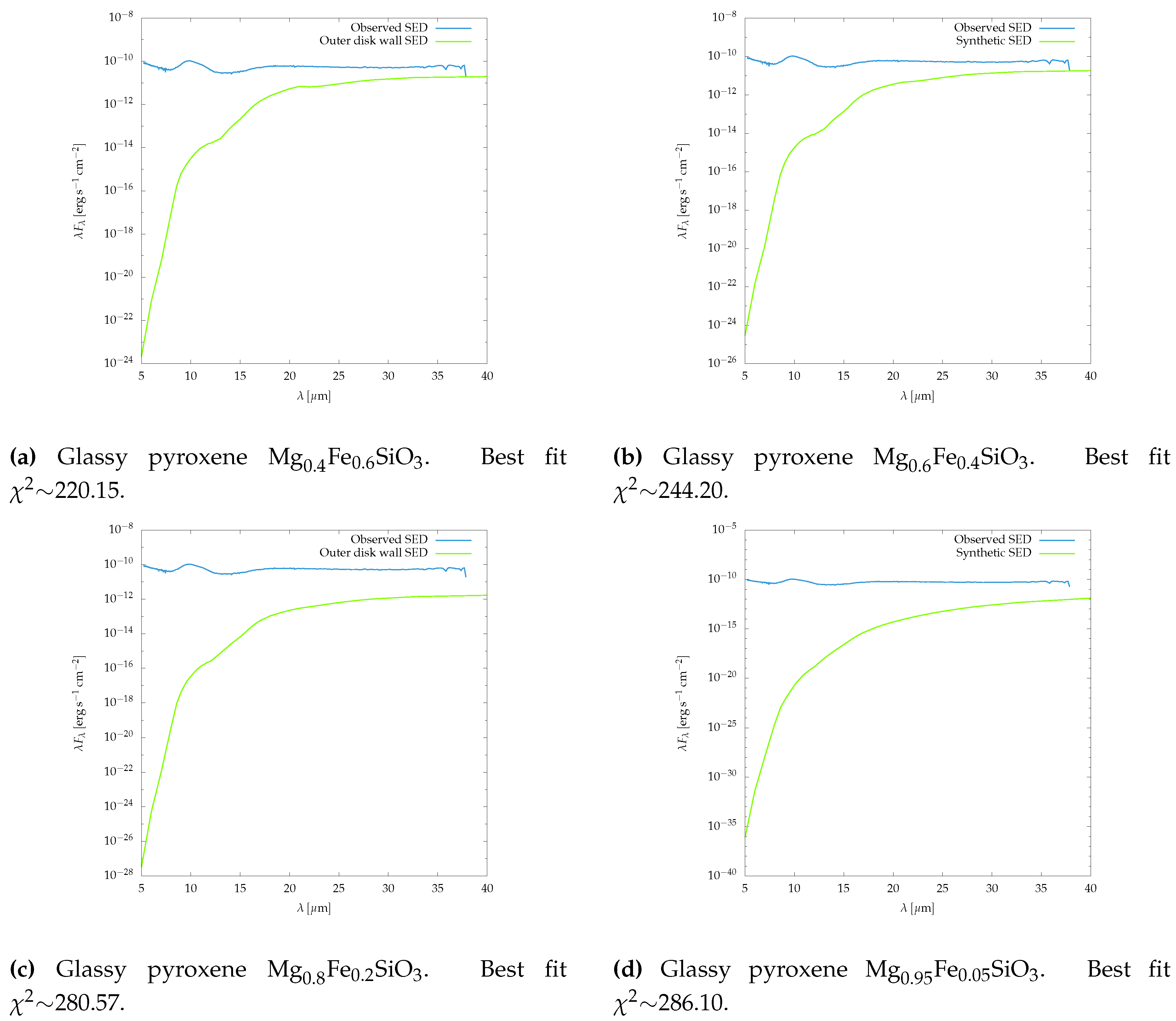

Synthetic SEDs of the wall of the outer disk, where the dust consists of grains of glassy pyroxene with different concentration of Fe and Mg are showed in

Figure 15. I performed a chi–square test for each model, to examine whether the synthetic SED fits to the

Spitzer IRS SED. I found that no model is either capable to fit the observed SED (

∼300) nor reproduce the silicate peak at ∼

. However, for glassy pyroxene with 60% Fe and 40% Mg (see

Figure 15a) it seems the silicate peaks tries to appear at ∼

, this lead us to think that a lesser concentration of Mg in the pyroxene composition would produce the silicate feature. Unfortunately, there is not available, in the literature, the optical constants needed to calculate the opacities, for such chemical concentrations.

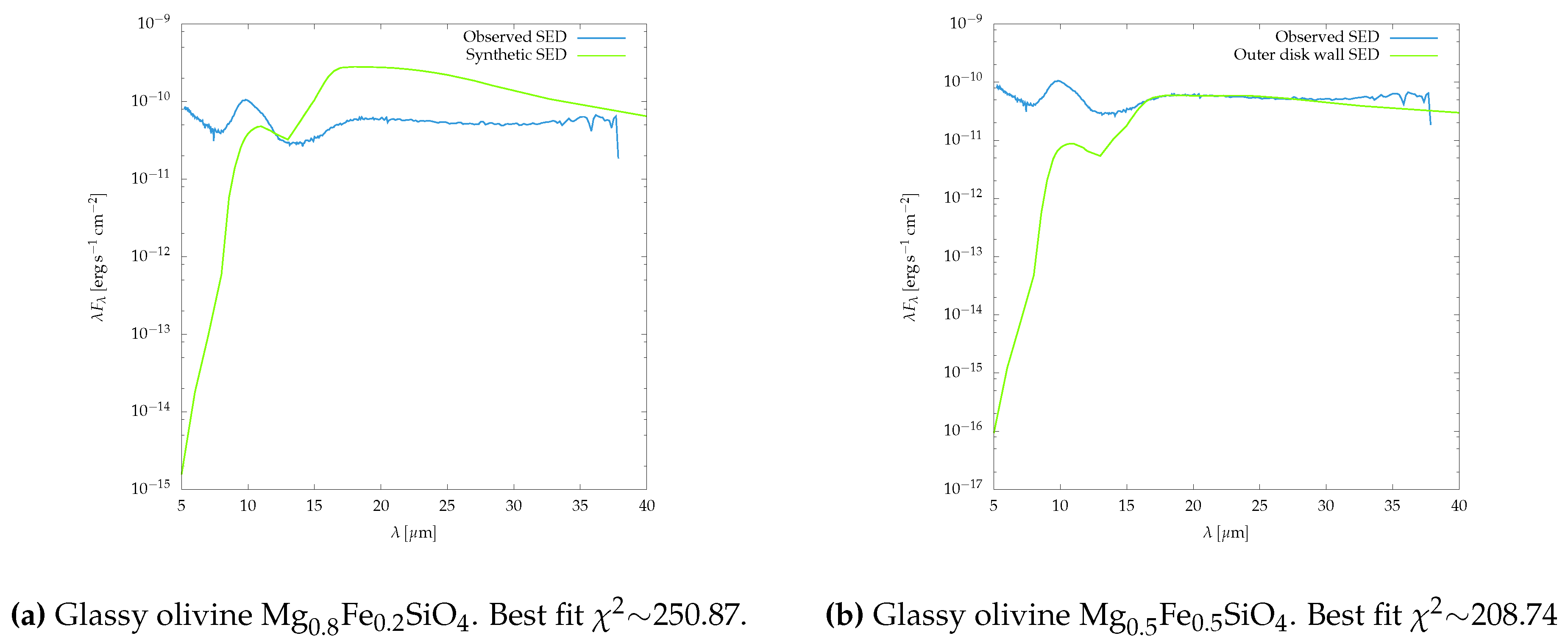

In

Figure 16, I show the synthetic SEDs of the wall of the outer disk, where the dust mixture consists of grains of glassy olivine with different concentration of Fe and Mg. I found that none of these configurations is capable to fit the observed SED (

). However, in both cases a silicate peak appears at ∼

. A concentration of 50% Fe and 50% Mg produces the best fit (see

Figure 16b).

Previous results lead us to say that the SED of LkCa 15 is not dominated by the contribution of the curved wall of the outer disk in the mid–infrared. However, when olivine grains with a concentration of 50% Fe and 50% Mg or 80% Fe and 20% Mg are in the dust mixture, a silicate feature appears at ∼.

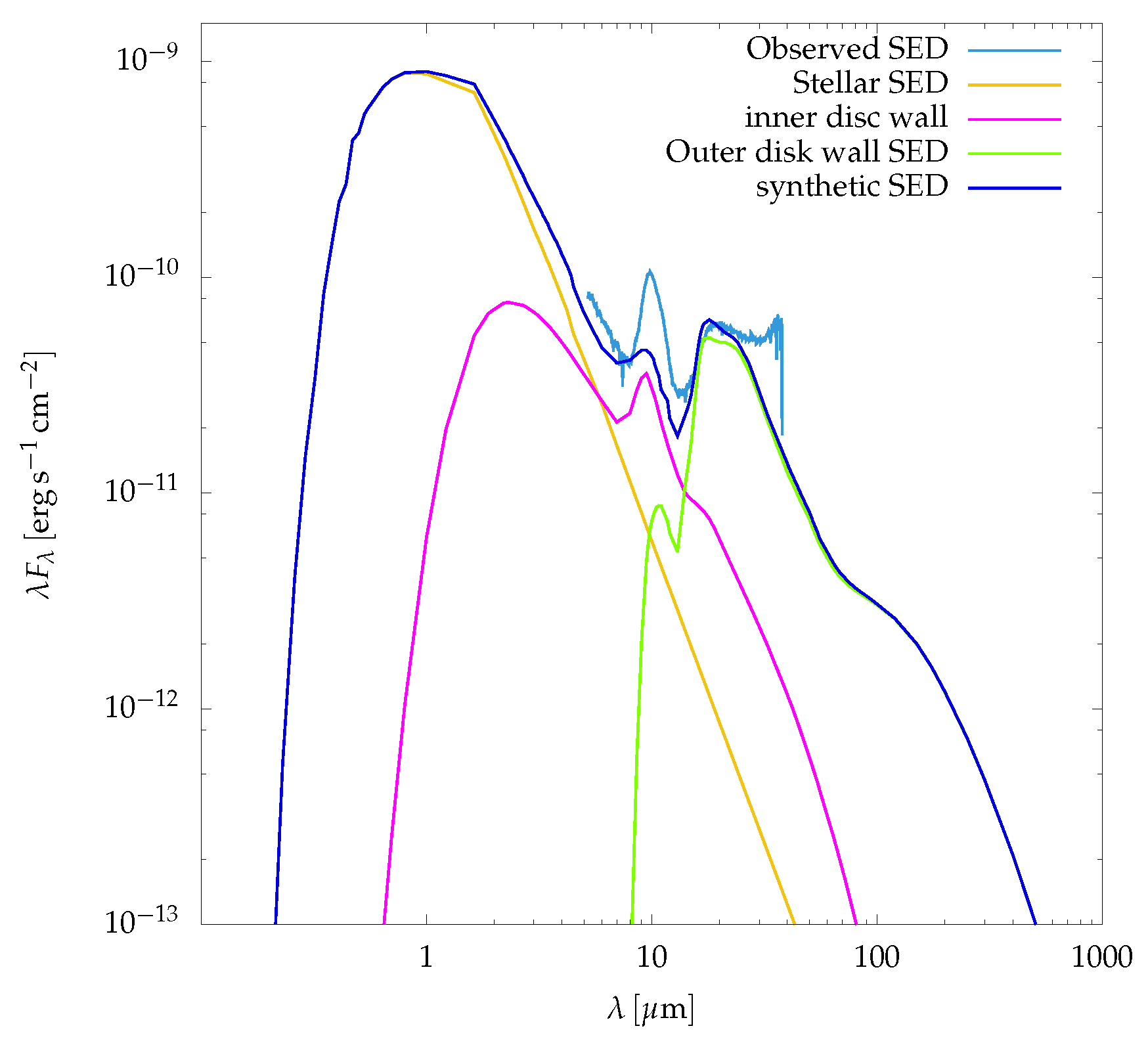

4.5. SED of the System

Considering the SED contribution of the inner sublimation wall and the star, in addition to the SED contribution of the wall of the outer disk, I present a more complete model of the stellar system LkCa 15. For the stellar SED, I have used a Kurucz atmosphere model with

and

.

Table 3 lists the parameters for this model. In

Figure 17, I show the contribution of the star, the inner sublimation wall and the wall of the outer disk to the total synthetic SED.

Only for some wavelengths in the mid–infrared, ∼

∼

, the sythetic SED fit to LkCa 15 observed SED, I estimated

∼

. For all the other wavelengths in the field of view of the

Spitzer IRS (5.217–37.86

m), the synthetic SED is below the observed SED. For wavelengths ∼

∼

the difference is not very high (

∼

); however, for wavelengths ∼

∼

(with

∼

) and ∼

∼

(with

∼

) this difference becomes significant (see

Figure 18).

I can suggests that the inner sublimation wall and the stellar photo-sphere cannot account for the significant near-infrared excess in LkCa 15. It means the SED model also requires of optically thin dust inside the gap to explain the excess and to produce the

silicate feature as showed in [

43]. Similarly, as the wall of the outer disk cannot account for the excess in the mid and long–infrared, I asumme that this SED model also requires of the contribution of the outer disk.

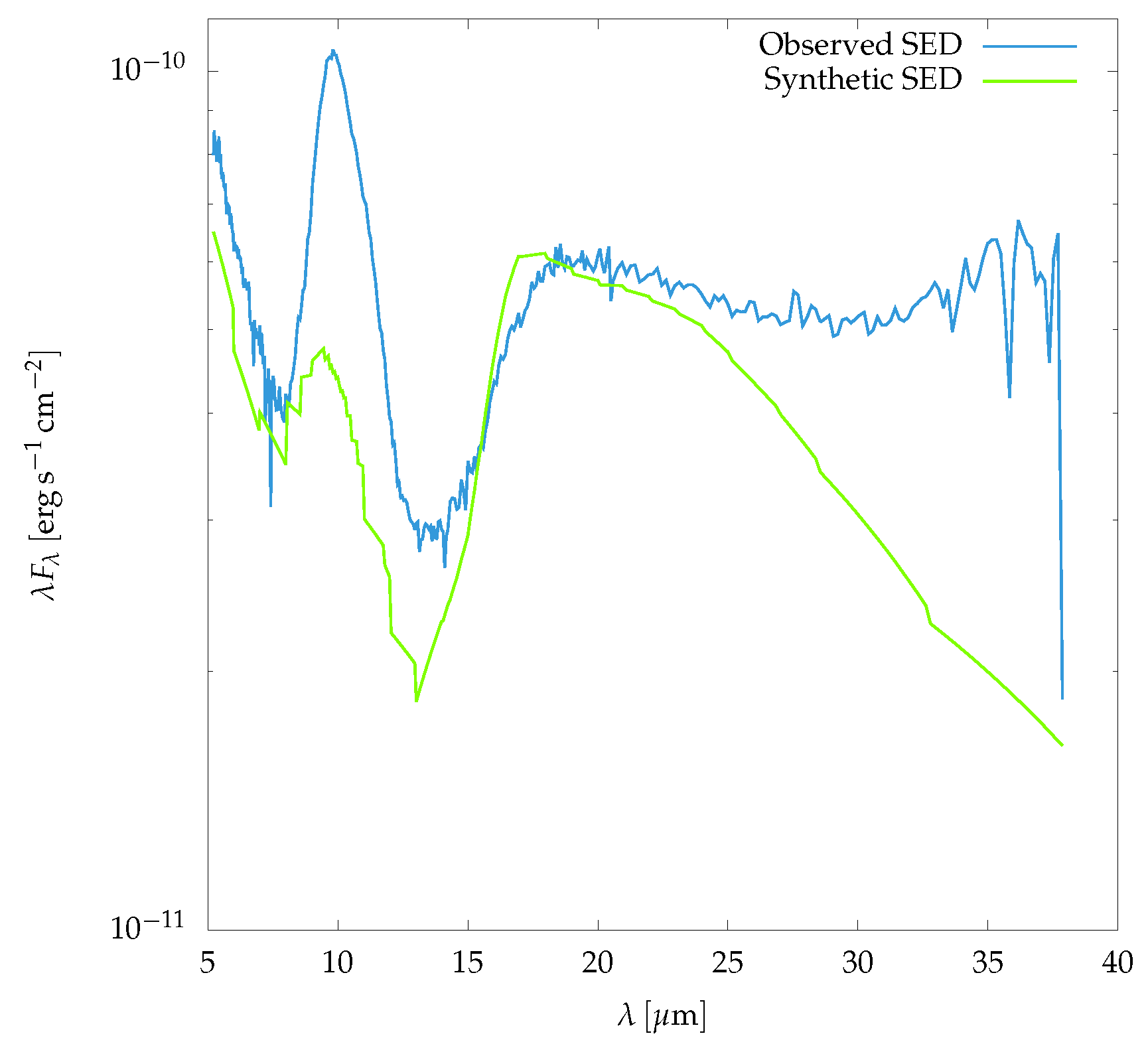

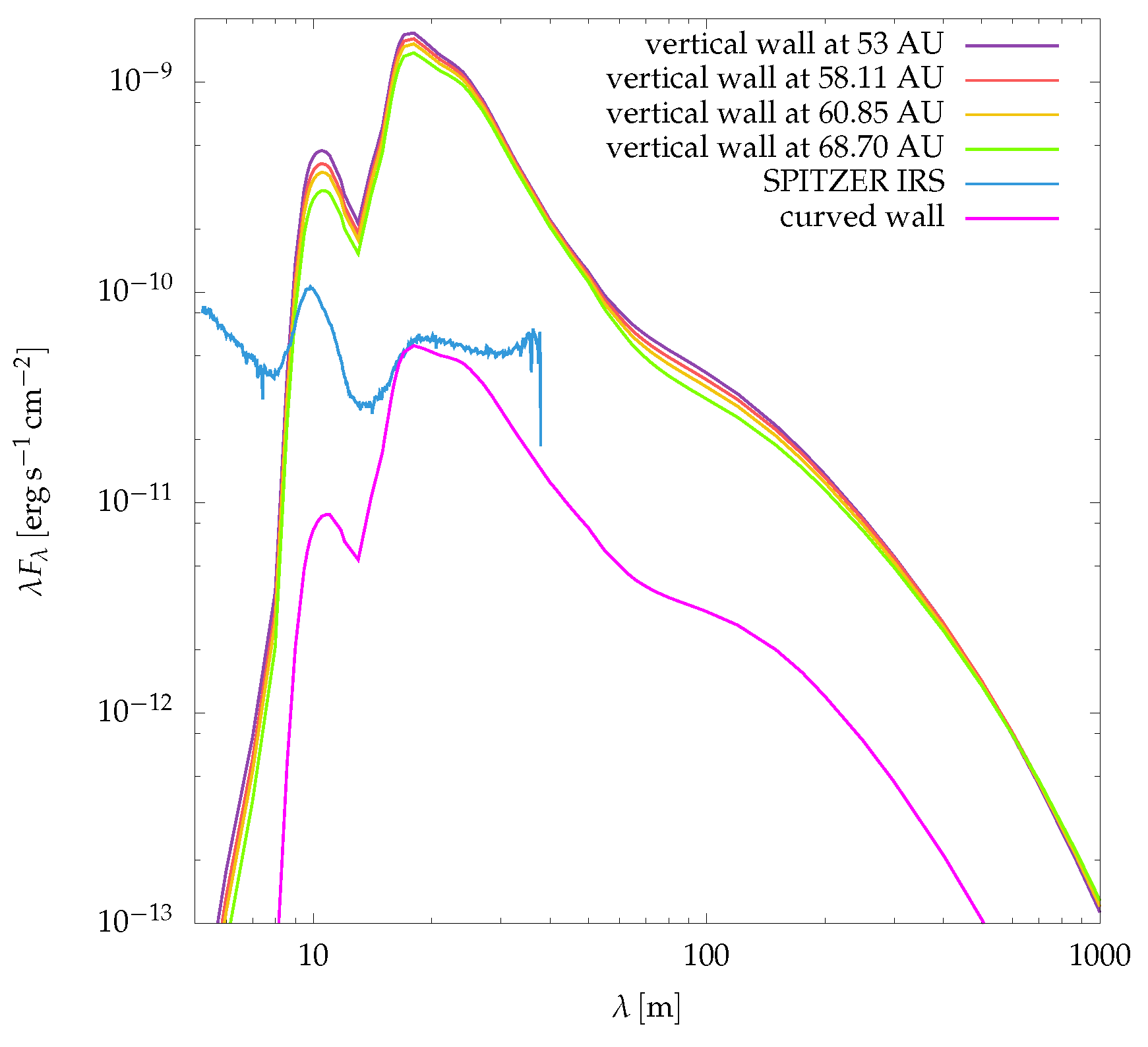

5. Discussion: Vertical Wall SED vs. Curved Wall SED

Wall SED models of LkCa 15 (and many other pre-TDs and TDs) are based on vertical walls [e.g. [

23,

43]].

rhada

man

te code is able to construct wall SEDs based on this geometry. Here I present some wall SED models of LkCa 15 considering vertical walls to compare with the best fit curved wall SED model (as seen in

Figure 19).

In these vertical wall SED models, it is also cosidered that the umbra cast by the inner disk is (measured from the disk mid–plane to up). The height of the wall is (measured from the disk mid–plane to up). The size and composition of the dust grains remain the same as described for the best fit curved wall SED model.

The vertical walls were located at 30,

,

and

.

rhada

man

te estimated the area of the visible surface projected on the plane of the sky of these vertical walls,

, and the curved wall,

. I found that

, if the umbra of the inner disk is considered. While if the emission of the whole wall is considered,

. Wall temperatures also were estimated, I found

,

,

and

, respectively. It means that the temperature of a vertical wall,

, decreases if its radius,

, increases. Furthermore, the radiation emitted by a vertical wall,

, also decreases as

increases, as seen in

Figure 19.

Finaly, I compared the radiation emitted by vertical walls,

, with the radiation emitted by the curved wall,

(see

Figure 19). I found that

for wavelengths between 5 and

. The difference between fluxes becomes significant, about one order of magnitude, for

.

This infrared excess arises, in part, from the angle,

, between the radiation ray and the normal to the wall (see

Section 3.1), because

. For vertical walls,

for all the radiation rays hitting the wall, because the normal to the wall is always parallel to the disk mid–plane. Whereas for curved walls

, because of the wall curvature. In addition, for some models, some regions of the curved wall are farther from the central star than the vertical one.

The above two facts induce a lower exposure of the curved wall to the host star radiation, which derives in much less radiative heating of the wall, and, consequently, in the significantly lower radiative infrared cooling flux. For this reason, the one order of magnitude in lower infrared emisison in the curved wall model is as significant as correct by very basic physical considerations: the height of the curved wall and the umbra cast by the inner disk onto the outer disk.

It is worth mentioning that the geometry, location and height of the curved wall arise from a physical mechanism considering the opacities and chemical composition of the disk, where the disk is the result of a three–dimensional hydro–dynamical simulation, whereas for the vertical walls there is not any physics to choice these parameters. Although the curved wall SED model is the best choice to compare with the

Spitzer IRS SED of LkCa 15, as it is showed in

Figure 19, to rise this synthetic flux to the right level, it is needed, in adittion, the contribution of the central star, the inner disk, the outer disk and a region of optically thin dust inside the gap, as discussed in

Section 4.4.

6. Conclusions

The computational code rhadamante was developed in order to calculate synthetic SEDs of protoplanetry disks. As a initial parameter, the code requires the geometry of the wall coming from hydro-dynamical three-dimensional simulations of the planet-disk interaction and dust grain properties. This code is useful to explain the observed SED of young stellar systems in transition stage. It would lead to unveil the structure of the system, such as, the inner disk, the gap, and the outer disk, even the location and mass of the embedded planet responsible of the gap opening.

From the implementation of this code to the pre-transitional disk LkCa 15, it can be concluded that:

All models of the SED consisting only of a curved wall, using different concentrations of Fe and Mg for the silicate (pyroxene and olivine) grains, suggest that LkCa 15’s Spitzer IRS SED cannot be accounted by the emission of a curved wall. Chi-square tests indicate the models are not good (∼). In addition, for models with a dust mixture containing glassy amorphous olivine grains, or , a silicate feature can be observed. However, the intensity of this silicate emission to that measured in the Spitzer IRS SED.

Including to the wall SED model, the contribution of the stellar photo-sphere and the sublimation wall of the inner disk, considering a dust mixture with amorphous glassy olivine with 50% Fe and 50% Mg and a small amount of organic and troilite grains, the observed and synthetic SEDs fit better (∼45). However, this model cannot fit the Spitzer IRS SED. Only for a small band in the mid-infrared, ∼∼, the fit is good (∼).

Several limitations exist in the current model: The contribution of the inner disk was not considered, neither the contribution of an optically thin region inside the gap [e.g. [

23,

43], nor the optically thick outer disk. The inner disk might contribute to the SED at wavelengths in the near infrared. The optically thin region might explain the silicate feature of the

Spitzer IRS SED at

. While the outer disk might contribute to the SED at wavelengths longer than

.

Vertical wall SED models, via rhadamante code, show a difference of one order of magnitude in the flux, , compared to the curved wall SED model, , for wavelengths from 8 to . This difference arises from dependency of the flux, , on the cosine of the angle, , between the stellar radiation ray and the normal to the wall. This lower exposure of the curved wall to the stellar radiation results in much less radiative heating of the wall, and, consequently, in the significantly lower radiative infrared cooling flux.

The synthetic SED of a curved wall, estimated by rhadamante code, includes physical and chemical mechanisms absent in the estimation of the SED of a vertical wall. That is, a curved wall SED is better to fit the Spitzer IRS SED of LkCa 15 or any other protoplanetaray disk.

Funding

“This research was funded by Consejo Nacional de Humanidades, Ciencia y Tecnología (CONAHCyT) grant number CF-2023-I-1221.”

Conflicts of Interest

“The author declares no conflicts of interest.”

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

|

Mass of the Sun |

|

Mass of Jupiter |

Appendix A. Mathematical Tools

Appendix A.1. Construction of a Vertical Wall

Consider an inclined segment line as showed in

Figure 1a. Circles

and

, with radii

and

and height

and

, respectively, are generated by rotating such segment line around

z–axis. These circles define the superior and inferior boundaries of a tri–dimensional wall

. The projection on the

–plane of these circles, given an inclination angle

i, generates the ellipses

and

, as seen in

Figure A1a. Ellipse

is centered at

with semi–major and semi–minor axes

a and

b, respectively. Whereas, ellipse

is centered at

with semi–major and semi–minor axes

and

, respectively.

Without lost of generality I focus on the construction of ellipse

. As the coordinate system

is centered on the star, it follows

, and the

Y coordinate of the ellipse is the projection of the height

of the circle

on the

Y-axis, as seen in

Figure A1b, that is,

. The semi–major axis is

, and the semi–minor axis is the projection of the radius of the circle

on the

Y-axis, as seen in

Figure A1b, that is,

.

Figure A1.

Geometry of ellipses and defining the projection of the tri–dimensional wall on the –plane.

Figure A1.

Geometry of ellipses and defining the projection of the tri–dimensional wall on the –plane.

So the full form of the equation of ellipse

is:

Similarly, for ellipse

,

Hence, I define

such that

Appendix A.2. Area Between Two Curves

Definition A1.

The area between the curves and and the ordinates and is given by

if and only if .

Definition A2.

Let be a continuous function defined by . An anti-derivative or primitive function of f is

such that .

Appendix A.3. Theoretical area of the projected vertical wall: The whole wall

The following analysis, on the area of a visible wall (projected on the plane of the sky), focuses on the case corresponding to (the star is visible), because of LkCa 15 inclination angle ().

The area of the projection of a whole vertical wall on the plane of the sky is

as seen in Figure (

Figure A2). Where, according to Definition A1,

and

Figure A2.

Area of the projection of the whole vertical wall on the plane of the sky , defined by the intersection of the ellipses and .

Figure A2.

Area of the projection of the whole vertical wall on the plane of the sky , defined by the intersection of the ellipses and .

Using Equation (

A6), it leads

Hence, the area of the projected vertical wall is

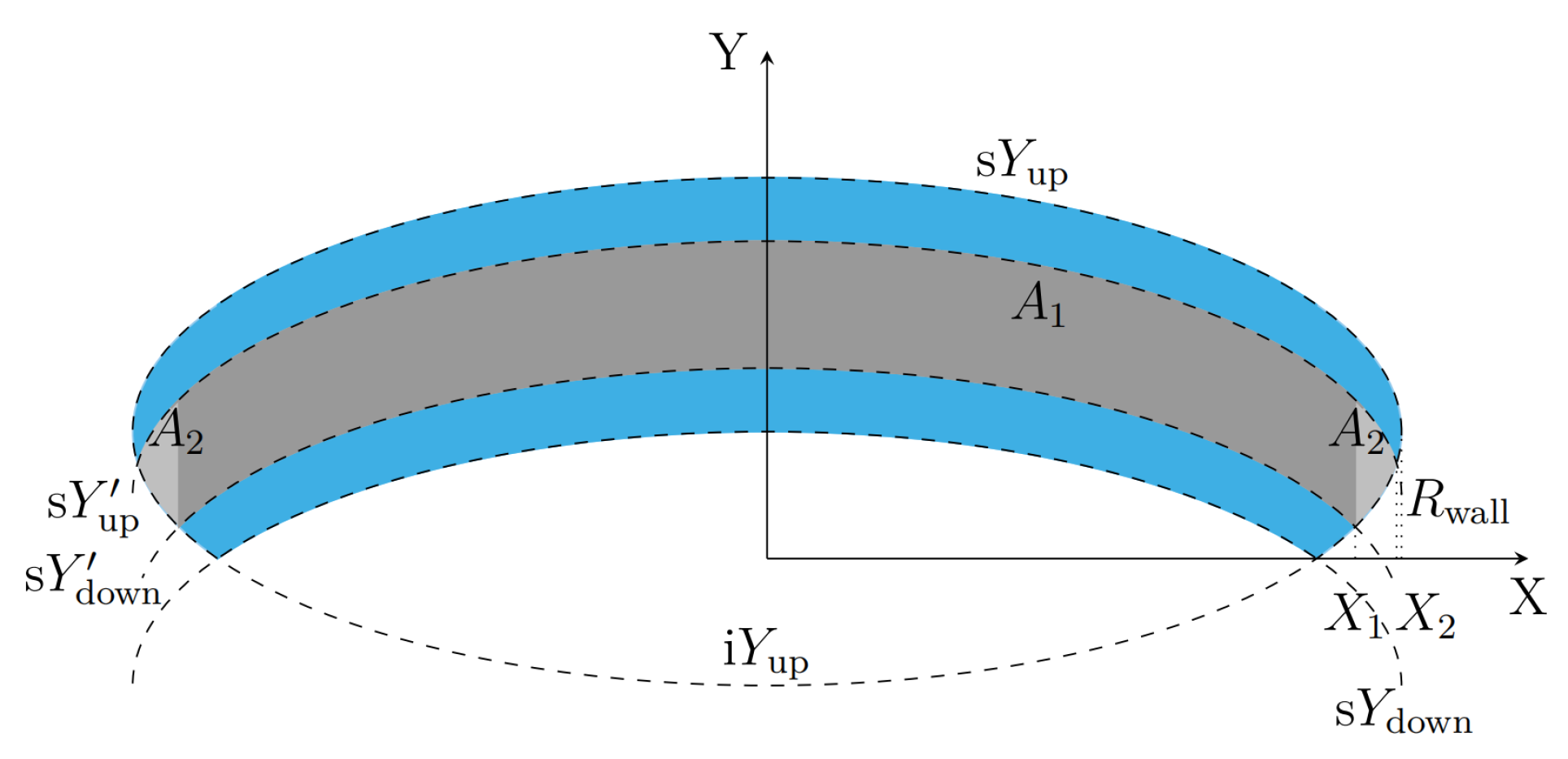

Appendix A.4. Theoretical Area of the Projected Vertical Wall: The Wall with Shadow

To calculate the area of the projection of a vertical wall considering the umbra cast by the inner disk, I subtract to the area generated by the whole wall [see Equation (A11)], the area generated by the shadow. The shadow can be assumed as a vertical wall with in height, measured from the mid–plane.

Then the area of the projection of the shadow on the plane of the sky is

as seen in

Figure A3. Where, according to Definition A1,

and

with

Figure A3.

Area of the projection of the shadow cast by the inner disk on the plane of the sky , defined by the intersection of the ellipses , and (in gray). The region in blue is the area of the visible wall.

Figure A3.

Area of the projection of the shadow cast by the inner disk on the plane of the sky , defined by the intersection of the ellipses , and (in gray). The region in blue is the area of the visible wall.

Using Equation (

A6), it leads

Hence, the area of the shadow, projected on the plane of the sky, is

Appendix B. Testing RHADaMAnTe

rhada

man

te code calculates the Spectral Energy Distribution (SED) of the curved wall of gaps in protoplanetary disk. Before doing its main task, this code has to calculate the projection of each ring on the plane of the sky, which defines the 3D-wall.

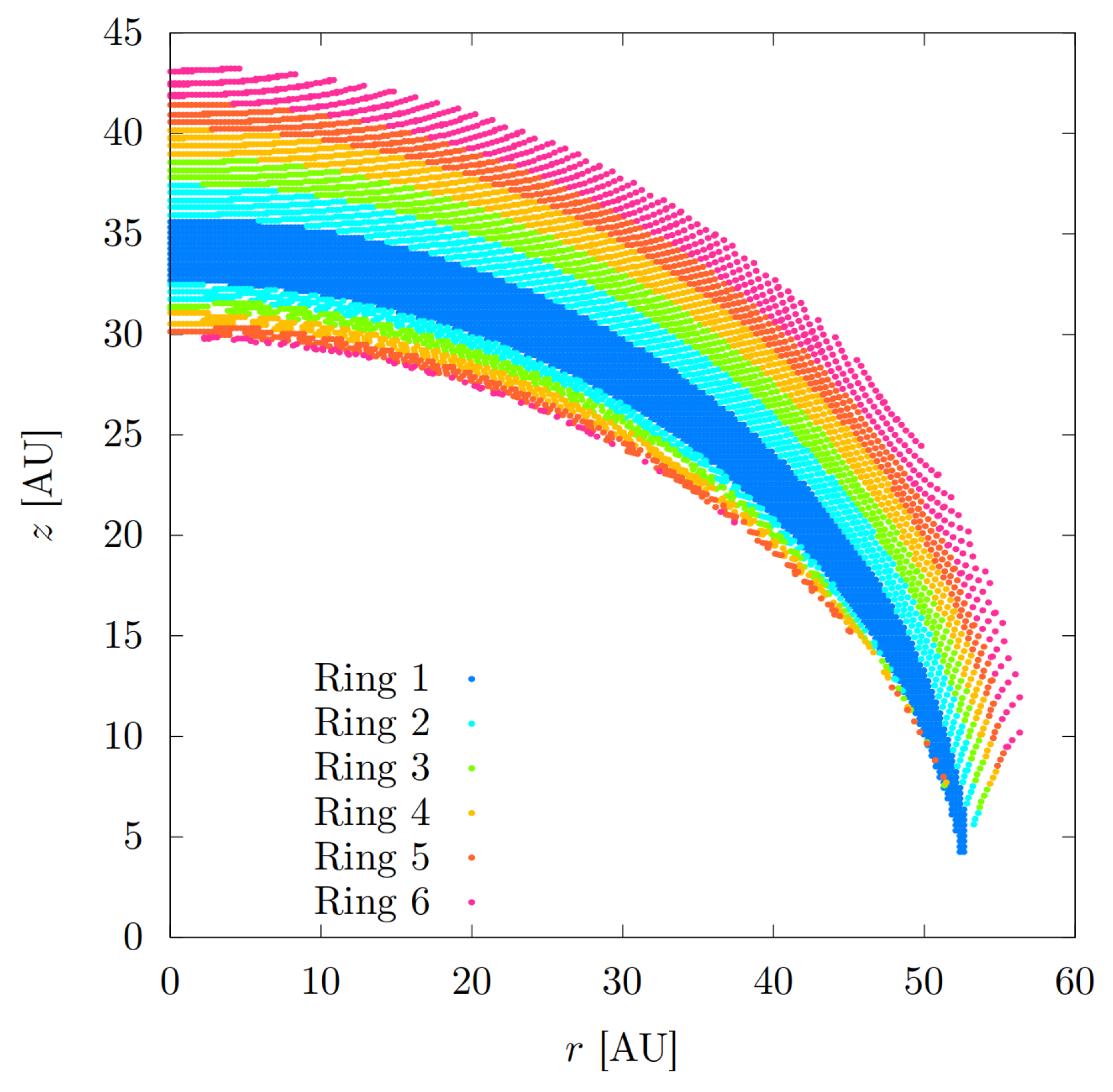

Figure A4 shows the results of a test where it is assumed that the 3D-wall is made of six rings.

Figure A4.

Wall surface projected on the plane of the sky calculated by rhadamnte.

Figure A4.

Wall surface projected on the plane of the sky calculated by rhadamnte.

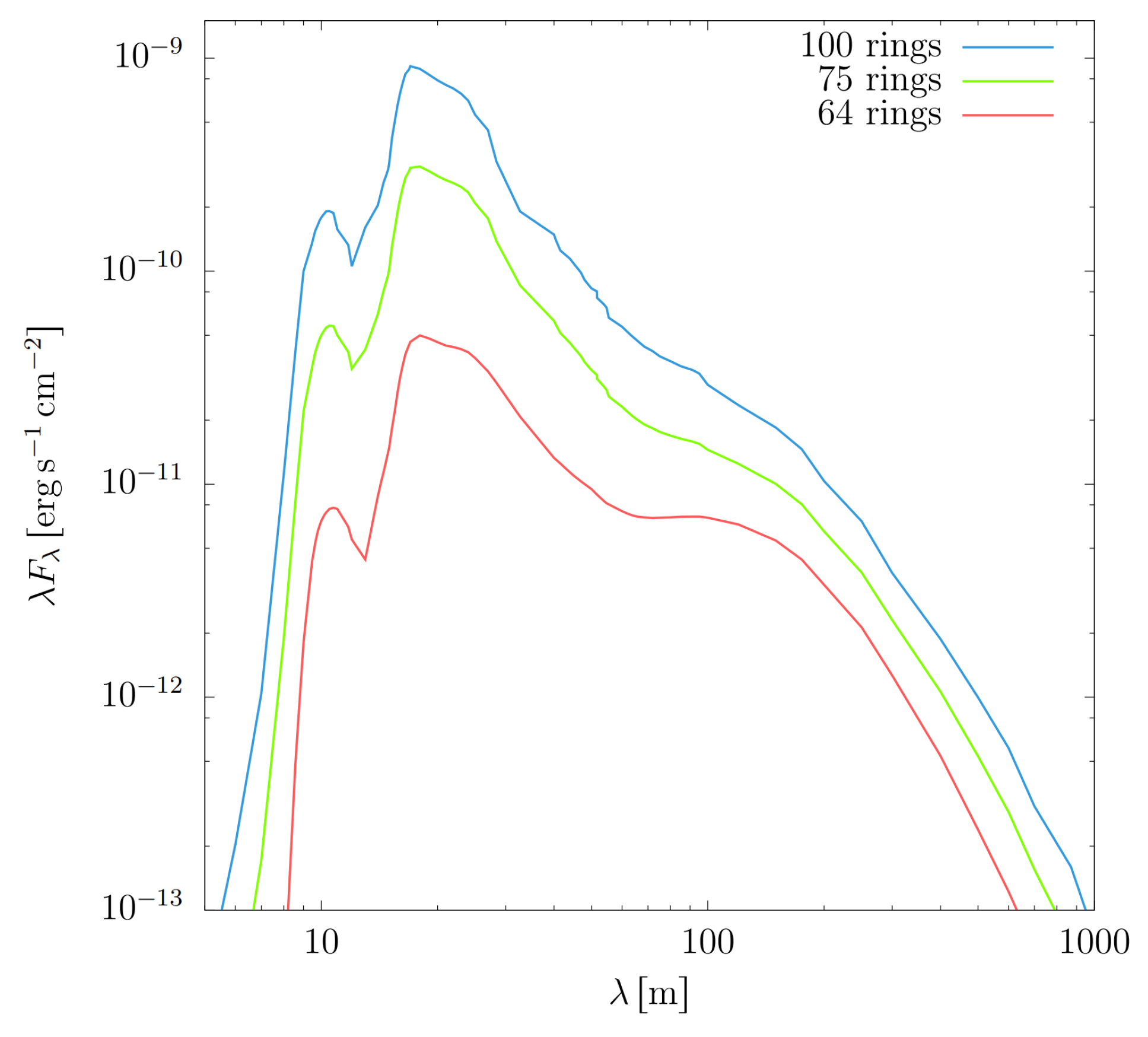

Figure A5 shows the synthetic SED of a curved wall depending on the number of rings used to estimate it. That is, as the number of the rings increases the

size of the SED also increases. In the test it was noticed that the greater contributors to the SED are those rings near the mid-plane.

Figure A5.

SEDs of a curved wall with different ring contributions calculated by rhadamante. SED in blue is calculated using all the rings, that is, the whole wall. SED in green is calculated starting from the 14th ring above the disk-mid plane, and SED in red is calculated starting from the 36th ring, that is, a shadowed wall.

Figure A5.

SEDs of a curved wall with different ring contributions calculated by rhadamante. SED in blue is calculated using all the rings, that is, the whole wall. SED in green is calculated starting from the 14th ring above the disk-mid plane, and SED in red is calculated starting from the 36th ring, that is, a shadowed wall.

References

- Calvet, N.; D’Alessio, P.; Hartmann, L.; Wilner, D.; Walsh, A.; Sitko, M. Evidence for a Developing Gap in a 10 Myr Old Protoplanetary Disk. ApJ 2002, 568, 1008–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espaillat, C.; Calvet, N.; D’Alessio, P.; Hernández, J.; Qi, C.; Hartmann, L.; Furlan, E.; Watson, D.M. On the Diversity of the Taurus Transitional Disks: UX Tauri A and LkCa 15. ApJ 2007, 670, L135–L138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espaillat, C.; Calvet, N.; D’Alessio, P.; Bergin, E.; Hartmann, L.; Watson, D.; Furlan, E.; Najita, J.; Forrest, W.; McClure, M.; Sargent, B.; Bohac, C.; Harrold, S.T. Probing the Dust and Gas in the Transitional Disk of CS Cha with Spitzer. ApJ 2007, 664, L111–L114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendón, F. Modelación de la geometría de paredes de cavidades en discos protoplanetarios mediante el código ARTeMiSE. In Modelación matemática V: Ingeniería, Ciencias Naturales y Ciencias Sociales; Reyes-Mora, S., Barragán-Mendoza, F., Eds.; Universidad Tecnológica de la Mixteca: Huajuapan de León, Oaxaca, México, 2023; pp. 57–75. [Google Scholar]

- Muzerolle, J.; Calvet, N.; Hartmann, L.; D’Alessio. Unveiling the Inner Disk Structure of T Tauri Stars. ApJ 2003, 597, L149–L152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessio, P.; Hartmann, L.; Calvet, N.; Franco-Hernández, R.; Forrest W., J.; Sargent, B.; Furlan, E.; Uchida, K.; Green, J.D.; Watson, D.M.; Chen, C.H.; Kemper, F.; Sloan, G.C.; Najita, J. The Truncated Disk of CoKu Tau/4. ApJ 2005, 621, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathis, J.S.; Rumpl, W.; Nordsieck, K.H. The size distribution of interstellar grains. ApJ 1997, 217, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, M.; Flynn, G. Dust Composition in Protoplanetary Disks. In Protoplanetary Dust: Astrophysical and Cosmochemical Perspectives; Apai, D. A.; Lauretta, D.S., Eds.; Cambridge University Press, 2010; pp. 161–190.

- Min, M.; Hovenier, J.W.; de Koter, A.; Waters, L.B.F.M.; Dominik, C. The composition and size distribution of the dust in the coma of Comet Hale Bopp. Icarus 2005, 179, 158–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisse, C.M.; VanCleve, J.; Adams, A.C.; A’Hearn, M.F.; Fernández, Y.R.; Farnham, T.L.; Armus, L.; Grillmair, C.J.; Ingalls, J.; Belton, M.J.S.; Groussin, O.; McFadden, L.A.; Meech, K.J.; Schultz, P.H.; Clark, B.C.; Feaga, L.M.; Sunshine, J.M. Spitzer Spectral Observations of the Deep Impact Ejecta. Science 2006, 313, 635–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habart, E.; Testi, L.; Natta, A.; Carbillet, M. Diamonds in HD 97048: A Closer Look. ApJ 2004, 614, L129–L132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeus, G. , Waters, L.B.F.M.; Bouwman, J.; van den Ancker, M. E.; Waelkens, C.; Malfait, K. ISO spectroscopy of circumstellar dust in 14 Herbig Ae/Be systems: Towards an understanding of dust processing. A&A 2001, 364, 476–490. [Google Scholar]

- Acke, B.; van den Ancker, M.E. ISO spectroscopy of disks around Herbig Ae/Be stars. A&A 2004, 426, 151–170. [Google Scholar]

- Geers, V.C.; Augereau, J.-C.; Pontoppidan, K.M.; Dullemond, C.P.; Visser, R.; Kessler-Silacci, J.E.; Evans, N.J., II; van Dishoeck, E.F.; Blake, G.A.; Boogert, A.C.A.; Brown, J.M.; Lahuis, F.; Merín, B. C2D Spitzer-IRS spectra of disks around T Tauri stars. II. PAH emission features. A&A 2004, 459, 545–556. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, L.P.; Messenger, S.; Flynn, G.J.; Jacobsen, C.; Wirick, S. Chemical and Petrographic Studies of Molecular Cloud Materials Preserved in Interplanetary Dust. MaPS 2000, 35, A86. [Google Scholar]

- Terada, H.; Tokunaga, A.T.; Kobayashi, N.; Takato, N.; Hayano, Y.; Takami, H. Detection of Water Ice in Edge-on Protoplanetary Disks: HK Tauri B and HV Tauri C. ApJ 2007, 667, 303–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Ancker, M.E.; Bouwman, J.; Wesselius, P.R.; Waters, L.B.F.M.; Dougherty, S.M.; van Dishoeck, E.F. ISO spectroscopy of circumstellar dust in the Herbig Ae systems AB Aur and HD 163296. A&A 2000, 357, 325–329. [Google Scholar]

- Malfait, K.; Waelkens, C.; Bouwman, J.; de Koter, A.; Waters, L.B.F.M. The ISO spectrum of the young star HD 142527. A&A 1999, 345, 181–186. [Google Scholar]

- McClure, M.K.; Manoj, P.; Calvet, N.; Adame, L.; Espaillat, C.; Watson, D.M.; Sargent, B.; Forrest, W.J.; D’Alessio, P. Probing Dynamical Processes in the Planet-forming Region with Dust Mineralogy. ApJ 2012, 759, L10–L16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M. and Dutrey, A.;Guilloteau, S. Dynamical Masses of T Tauri Stars and Calibration of Pre-Main-Sequence Evolution. ApJ 2000, 545, 1034–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenyon, S.J.; Hartmann, L. Pre-Main-Sequence Evolution in the Taurus-Auriga Molecular Cloud. ApJS 1995, 101, 117–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thalmann, C.; Mulders, G.D.; Hodapp, K.; Janson, M.; Grady, C.A.; Min, M.; de Juan Ovelar, M.; Carson, J.; Brandt, T.; Bonnefoy, M.; McElwain, M.W.; Leisenring, J.; Dominik, C.; Henning, T.; Tamura, M. The architecture of the LkCa 15 transitional disk revealed by high-contrast imaging. A&A 2014, 556, A51–A74. [Google Scholar]

- Espaillat, C. and D’Alessio, P. and Hernández, J.; Nagel, E.; Luhman, K.L.; Watson, D.M.; Calvet, N.; Muzerolle, J.; McClure, M. Unveiling the Structure of Pre-transitional Disks. ApJ 2010, 717, 441–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, A. L.; Ireland, M.J. LkCa 15: A Young Exoplanet Caught at Formation? ApJ 2012, 745, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallum, S.; Follette, K.B.; Eisner, J.A.; Close, L.M.; Hinz, P.; Kratter, K.; Males, J.; Skemer, A.; Macintosh, B.; Tuthill, P.; Bailey, V.; Defrère, D.; Morzinski, K.; Rodigas, T.; Spalding, E.; Vaz, A.; Weinberger, A.J. Accreting protoplanets in the LkCa 15 transition disk. Nature 2015, 527, 342–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergin, E.; Calvet, N.; Sitko, M.L.; Abgrall, H.; D’Alessio, P.; Herczeg, G.J.; Roueff, E.; Qi, C.; Lynch, D. K.; Russell, R.W.; Brafford, S.M.; Perry, R.B. A New Probe of the Planet-forming Region in T Tauri Disks. ApJ 2004, 614, L133–L136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najita, J.R.; Strom, S.E.; Muzerolle, J. Demographics of transition objects. MNRAS 2007, 378, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espaillat, C.; Calvet, N.; Luhman, K.L.; Muzerolle, J.; D’Alessio, P. Confirmation of a Gapped Primordial Disk around LkCa 15. APJ 2008, 682, L125–L128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piétu, V.; Dutrey, A.; Guilloteau, S.; Chapillon, E.; Pety, J. Resolving the inner dust disks surrounding LkCa 15 and MWC 480 at mm wavelengths. A&A 2006, 378, L43–L47. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, S. M.; Williams, J.P. High-Resolution Submillimeter Constraints on Circumstellar Disk Structure. APJ 2005, 659, 705–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez-Llambay, P.; Masset, F. S. FARGO3D: A New GPU-oriented MHD Code. ApJ 2016, 223, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui-Bon-Hoa, A. Stellar models with self-consistent Rosseland opacities - Consequences for stellar structure and evolution. A&A 2021, 646, L6–L10. [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessio, P.; Calvet, N.; Hartmann, L.; Franco-Hernández, R.; Servín, H. Effects of Dust Growth and Settling in T Tauri Disks. ApJ 2006, 638, 314–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, J.B.; Hollenbach, D.; Beckwith, S.; Simonelli, D. P.; Roush, T.; Fong, W. Composition and radiative properties of grains in molecular clouds and accretion disks. ApJ 1994, 421, 615–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, C.; Mutschke, H.; Begemann, B.; Dorschner, J.; Henning, T. Steps toward interstellar silicate mineralogy. 1: Laboratory results of a silicate glass of mean cosmic composition. A&A 1994, 292, 641–655. [Google Scholar]

- Dorschner, J.; Begemann, B.; Henning, T.; Jaeger, C.; Mutschke, H. Steps toward interstellar silicate mineralogy. II. Study of Mg-Fe-silicate glasses of variable composition. A&A 1995, 300, 503–520. [Google Scholar]

- Draine, B.T. Interstellar Dust Grains. ARA&A 2003, 41, 241–289. [Google Scholar]

- Begemann, B.; Dorschner, J.; Henning, T.; Mutschke, H.; Thamm, E. A laboratory approach to the interstellar sulfide dust problem. ApJ 1994, 423, L71–L74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henning, T.; Il’In, V.B.; Krivova, N.A.; Michel, B.; Voshchinnikov, N. V. WWW database of optical constants for astronomy. A&AS 1999, 136, 405–406. [Google Scholar]

- Piétu, V.; Dutrey, A.; Guilloteau, S. Probing the structure of protoplanetary disks: a comparative study of DM Tau, LkCa 15, and MWC 480. A&A 2007, 467, 163–178. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, S.M.; Rosenfeld, K.A.; Wilner, D.J.; Bremer, M. A Closer Look at the LkCa 15 Protoplanetary Disk. ApJ 2011, 745, L5–L10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, E.; D’Alessio, P.; Calvet, N.; Espaillat, C.; Trinidad, M. A. The Effect of Sublimation Temperature Dependencies on Disk Walls Around T Tauri Stars. RMXAA 2013, 49, 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Espaillat, C.; Calvet, N.; D’Alessio, P.; Hernández, J.; Qi, C.; Hartmann, L.; Furlan, E.; Watson, D.M. On the Diversity of the Taurus Transitional Disks: UX Tauri A and LkCa 15. ApJ 2007, 670, L135–L138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Construction of a tri-dimensional conic wall.

Figure 1.

Construction of a tri-dimensional conic wall.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the visible surface of the wall as seen by the observer for two inclination angles.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the visible surface of the wall as seen by the observer for two inclination angles.

Figure 3.

Geometry of the visible wall projected on the plane of the sky for two inclination angles.

Figure 3.

Geometry of the visible wall projected on the plane of the sky for two inclination angles.

Figure 4.

Construction of a tri–dimensional vertical wall.

Figure 4.

Construction of a tri–dimensional vertical wall.

Figure 5.

Geometry of the incidence of the stellar radiation along a ray on the wall .

Figure 5.

Geometry of the incidence of the stellar radiation along a ray on the wall .

Figure 6.

Discretization of a two–dimensional curved wall by inclined line segments , for , and one vertical wall with in height.

Figure 6.

Discretization of a two–dimensional curved wall by inclined line segments , for , and one vertical wall with in height.

Figure 7.

Construction of a tri–dimensional wall : Each couple of points and in the two–dimensional wall defines a ring .

Figure 7.

Construction of a tri–dimensional wall : Each couple of points and in the two–dimensional wall defines a ring .

Figure 8.

Projection of a ring on the Y-axis: When the ring is located at distance along the z-axis of the system , the projected distance on the Y-axis is .

Figure 8.

Projection of a ring on the Y-axis: When the ring is located at distance along the z-axis of the system , the projected distance on the Y-axis is .

Figure 9.

A flow chart of the rhadamante code.

Figure 9.

A flow chart of the rhadamante code.

Figure 10.

Visualization of the 3D simulation (100 orbit).

Figure 10.

Visualization of the 3D simulation (100 orbit).

Figure 11.

Density isocontours on the disk: Gap opening.

Figure 11.

Density isocontours on the disk: Gap opening.

Figure 12.

Vertical geometry of the wall of the inner edge of the outer disk (picture is not scaled proportionally): Because of the embedded planet the wall is curved. It is ∼ in width and ∼ in height. In this model, the dust consists of a mixture of small and big grains of glassy olivine (silicate) with 50%Fe and 50% Mg and with a small amount of organic and troilite grains.

Figure 12.

Vertical geometry of the wall of the inner edge of the outer disk (picture is not scaled proportionally): Because of the embedded planet the wall is curved. It is ∼ in width and ∼ in height. In this model, the dust consists of a mixture of small and big grains of glassy olivine (silicate) with 50%Fe and 50% Mg and with a small amount of organic and troilite grains.

Figure 13.

Schematic representation of the pre-transitional disk LkCa15. In this ilustration the blue point represents the central star and the curved lines are the disk walls. The wall of the inner disk is fully illuminated by the central star. For the wall of the outer disk, light blue line represents the portion of the wall that is fully illuminated by the star, and black corresponds to the part of the wall that is in the umbra of the inner disk.

Figure 13.

Schematic representation of the pre-transitional disk LkCa15. In this ilustration the blue point represents the central star and the curved lines are the disk walls. The wall of the inner disk is fully illuminated by the central star. For the wall of the outer disk, light blue line represents the portion of the wall that is fully illuminated by the star, and black corresponds to the part of the wall that is in the umbra of the inner disk.

Figure 14.

Area of the projection of a curved wall on the plane of the sky . The wall starts at along the mid-plane and ends at , with total height of , and the disk inclination angle is .

Figure 14.

Area of the projection of a curved wall on the plane of the sky . The wall starts at along the mid-plane and ends at , with total height of , and the disk inclination angle is .

Figure 15.

Examples of wall synthetic SEDs (green line) compared to the observed SED (blue line) of LkCa 15. The dust mixture consists of different chemical composition of glassy pyroxene silicate grains and with a small amount of organic and troilite grains.

Figure 15.

Examples of wall synthetic SEDs (green line) compared to the observed SED (blue line) of LkCa 15. The dust mixture consists of different chemical composition of glassy pyroxene silicate grains and with a small amount of organic and troilite grains.

Figure 16.

Examples of wall synthetic SEDs (green line) compared to the observed SED (blue line) of LkCa 15. The dust mixture consists of different chemical composition of glassy olivine silicate grains and with a small amount of organic and troilite grains.

Figure 16.

Examples of wall synthetic SEDs (green line) compared to the observed SED (blue line) of LkCa 15. The dust mixture consists of different chemical composition of glassy olivine silicate grains and with a small amount of organic and troilite grains.

Figure 17.

Pre-transitional disk model of LkCa 15. The best-fit model to LkCa 15 (dark blue line), with a ∼ gap, consists of an inner optically thick disk with a curved sublimation wall and an outer optically thick disk with a curved wall. Separate model components are the stellar photo-sphere (yellow line), the inner disk sublimation wall (magenta line) and the outer disk wall (green line). We show the Spitzer IRS SED (light blue line).

Figure 17.

Pre-transitional disk model of LkCa 15. The best-fit model to LkCa 15 (dark blue line), with a ∼ gap, consists of an inner optically thick disk with a curved sublimation wall and an outer optically thick disk with a curved wall. Separate model components are the stellar photo-sphere (yellow line), the inner disk sublimation wall (magenta line) and the outer disk wall (green line). We show the Spitzer IRS SED (light blue line).

Figure 18.

Synthetic SED (green line) that best fit the observed SED (blue line) of LkCa15. With model parameters: , , , . The dust in the inner disk consists of small grains () and big grains () of silicates and graphite, while in the outer disk, the dust consists of small ( and ) and big grains (, ) of glassy olivine with 50% Fe and 50% Mg and with a small amount of organic and troilite grains.

Figure 18.

Synthetic SED (green line) that best fit the observed SED (blue line) of LkCa15. With model parameters: , , , . The dust in the inner disk consists of small grains () and big grains () of silicates and graphite, while in the outer disk, the dust consists of small ( and ) and big grains (, ) of glassy olivine with 50% Fe and 50% Mg and with a small amount of organic and troilite grains.

Figure 19.

Comparison between synthetic SEDs of vertical walls of gaps located at different , and a curved wall starting at and finishing at , created by rhadamante code. All the walls are in height, and it is considered a shadow (umbra) on the walls of due to the inner disk. Spitzer IRS SED is showed in blue.

Figure 19.

Comparison between synthetic SEDs of vertical walls of gaps located at different , and a curved wall starting at and finishing at , created by rhadamante code. All the walls are in height, and it is considered a shadow (umbra) on the walls of due to the inner disk. Spitzer IRS SED is showed in blue.

Table 1.

Disk-planet simulation specifications.

Table 1.

Disk-planet simulation specifications.

| |

parameter |

value |

| Disk |

Aspect ratio H

|

|

| Surface density

|

|

|

–viscosity |

|

|

slope |

1.0 |

| Flaring index |

0.0 |

| Planet |

|

|

|

|

| RocheSmoothing |

0.4 |

| Acretion |

No |

| Mesh |

Units |

unitless |

| Dimension |

3D |

| Geometry |

spherical |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Timing |

Orbits |

500 |

Table 2.

Parameters of the wall for different chemical composition of silicate dust grains: pyroxene and olivine. Organic and troilite grains composition is the same for all cases.

Table 2.

Parameters of the wall for different chemical composition of silicate dust grains: pyroxene and olivine. Organic and troilite grains composition is the same for all cases.

| silicate |

[AU] |

[AU] |

| pyroxene |

|

|

56.0 |

11.5 |

|

|

49.8 |

12.3 |

|

|

51.0 |

12.0 |

|

|

50.0 |

13.2 |

| olivine |

|

|

52.5 |

10.0 |

|

|

53.0 |

12.0 |

Table 3.

Stellar and model properties: and in the case of the outer wall are measured at the location of the umbra cast by the inner disk. Olivine silicate grains composition is 50% Fe and 50% Mg.

Table 3.

Stellar and model properties: and in the case of the outer wall are measured at the location of the umbra cast by the inner disk. Olivine silicate grains composition is 50% Fe and 50% Mg.

| |

parameter |

value |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| Star |

|

4370 K |

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| Disk |

Inclination |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| Inner wall |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| Dust |

|

silicates |

| |

|

graphite |

| Outer wall |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Dust |

|

olivine |

| |

|

organics |

| |

|

troilite |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).