1. Introduction

Astroglial cells (astrocytes) are the most numerous cell type in the central nervous system (CNS). They are characterized by expression of the cytoskeletal protein glial fibrillary-associated protein (GFAP) and express estrogen receptors. (Herbison et al., 1995; Chowen and Garcia-Segura, 2021)

Astrocytes have traditionally been viewed as support cells or scavengers of metabolic waste and excess neurotransmitter; however, recent developments indicate glial roles in synaptic plasticity as well as other attributes. (Naftolin et al., 2007; Vasile et al, 2017; Gamage et al, 2020; Fields & Stevens-Graham, 2002; Giaume et al, 2010; Vasile et al, 2017 ; Abotalebi et al, 2021; Torres, et al, JCI, 2024)

We and others have shown that Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs, including 17β-estradiol [estradiol]) induce changes in glial process spreading in rodent and primate (monkeys) brains that may account for changes in astroglial investment of neurons and their processes that regulate synaptic plasticity (Naftolin et al., 2007), and that estradiol inhibits hyperphosphorylation of the microtubule associate protein Tau (Alvarez-de-la-Rosa, et al, 2005), implying a role for SERMs in normal astroglial microtubule and cytoskeletal dynamics in degenerative brain diseases. (Rodrı´guez, et al., 2009; Shi, et al., 2024)

There is considerable debate around the effect of estrogens on astrocytic morphology. Estradiol, a naturally occurring selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM), has been shown to regulate the morphology of neurons and glia in the hypothalamus and hippocampus of rodents and monkeys. (Woolley et al., 1997; Lâm and Leranth, 2003; Naftolin et al, 2007; Vierk et al, 2015) In these cases, the spreading of glial processes is accompanied by decreased numbers of synapses. The obverse has also been reported. (Silva et al., 1999; Lâm and Leranth, 2003; Hung et al. 2003; Vasile et al, 2017) We proposed that glial spreading and retraction are the mechanism for estrogen-induced synaptic plasticity and that this may be related to the cytoskeleton-linking protein ezrin. (Naftolin et al., 2007) Recently, a similar relationship to synaptologic changes has been shown for the effect of the neurotransmitter kisspeptin. (Torres, et al., 2024)

Astroglial spreading can be determined by studying the facilitators of astroglial shape and branching. The intermediate fiber glial fibrillary protein (GFAP) is a prime determinant of astroglial process shape. (Middeldorp and Hol, 2011) Ezrin belongs to ERM (ezrin, radixin, moesin) family of proteins that link the plasma membrane and the actin cytoskeleton and are involved in cell adhesion and membrane ruffling. (Tsukita and Yonemura, 2002; Ornek et al., 2008) Ezrin is expressed by astrocytes and our preliminary data suggest that it is involved in estrogen’s induction of astroglial morphologic changes (Naftolin, unpublished). We have shown that estrogen induces ezrin expression. (Song et al., 2004) In this project, we immunolabeled GFAP and ezrin to determine the state of astroglial spreading.

Estradiol is the primary ovarian steroid that regulates hypothalamic synaptology during the ovarian cycle. This is particularly important in the regulation of the preovulatory LH surge. (Naftolin, et al, 1990; Naftolin, et al. 2007) While we have shown estradiol-induced synaptic plasticity in monkeys (Naftolin, et al. 2007), practical considerations have made the effect of estrogen on human central nervous system astroglia difficult to study. (Lee, et al. 2020) Fortunately, the dissection of the brain during surgery to remove tissue involved in seizures (epileptic foci) offers the opportunity to obtain normal neocortical tissue from the dissection of the human temporal lobe. In these preliminary studies we used brain slice methodology and immunohistochemistry to test for short-term in vitro effects of three SERMs, estradiol, tamoxifen and raloxifene, on human astroglial process thinning and branching. This methodology also allowed the confirmation of the expression of ezrin in human astroglia.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Temporal Lobe Tissue Collection and Culture

Neocortical temporal lobe tissue samples were acquired from five patients undergoing partial temporal lobectomy for treatment of intractable epilepsy through the Yale Epilepsy Surgery program. Participants provided informed consent for the use of surgically derived brain tissue for research purposes, and the study protocol was approved by the Yale University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board and Human Investigations Committees (IRB Protocol ID: 0011012081; Submission ID: CR00014498). The criteria for the selection of patients for surgery and the surgical method for en bloc resection are described elsewhere. (Spencer et al., 1984)

Tissue containing normal temporal lobe neocortex was obtained from five surgical procedures. Collected tissue was immediately placed in cold artificial CSF (aCSF) at 4°C. Specimens were oriented to expose the neocortex and then sectioned into 400 µm slices with a vibratome, as previously described. (Williamson et al, 2005)

Each incubation was performed in triplicate. Tissue slices were transferred and maintained in artificial cerebral-spinal fluid (aCSF). For study, individual temporal lobe slices were randomly selected from the total cache of slices. The slices were individually incubated in aCSF for 4 hrs., then exposed to 17β-estradiol (10 nM), raloxifene (1.0 µM), tamoxifen (1.0 µM), or aCSF (control) for 60 min. They were then prepared for immunostaining.

2.2. Immunohistochemistry

In order to maximally assess the effects of the three SERMs on glial processes, simultaneous double staining was performed. Individual 400 µm tissue slices were mounted in an orientation to expose the neocortex, fixed and stained as previously described. (de Lanerolle et al., 1989) Briefly, tissues were fixed in a solution of 2% picric acid and 2% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at pH 7.4 overnight, and then treated with 30% sucrose in PBS for 4 hours and cut into 50 μm sections with a cryostat. (Leica Cryocut, CM1950) Slices were double-immunostained with anti-ezrin (Sigma, E8897) and anti-GFAP (Sigma, SAB5500113). Anti-ezrin was marked by nickel diaminobenzidine (DAB), yielding dark blue-black staining while anti-GFAP was marked by horseradish DAB, yielding a brown color.

2.3. Image Analysis

The cache of immunostained sections was shuffled to randomize the study of each condition. Quantitative image analysis of astrocyte morphology was conducted using Neurolucida® (MBF Bioscience, Williston, VT). The images were photographed under 40X original magnification and additional computer magnification was used to perform the Neurolucida tracing. Slice images were divided into 50 areas, then 10 areas were randomly selected for analysis of branches using the following descriptors: primary processes – unbranched major processes emanating from the astrocyte soma, secondary processes – branched structures that emanate from primary processes, tertiary processes – branched, thinner regions of astrocyte staining associated with the individual astrocyte and often surrounding neural cells, identified as large cells with nuclei identified by negative staining. Astrocytic images were individually labeled and manually traced using the Neurolucida®. The software returned the calculation of area, volume, and number of each class of processes associated with each cell,

Table 1.

Immunostaining was evaluated by three observers blind to treatment. The findings are reported here as a consensus narrative since there was no testing of observer variance.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed with SPSS 13.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Prior to analyses, measures were examined for normality using Shapiro-Wilk testing. We used multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) to examine the effect of hormone treatments on astrocytic density and astrocyte process volume (dependent variables). P-values < 0.05 were considered numerically statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative Light Microscopic Observations

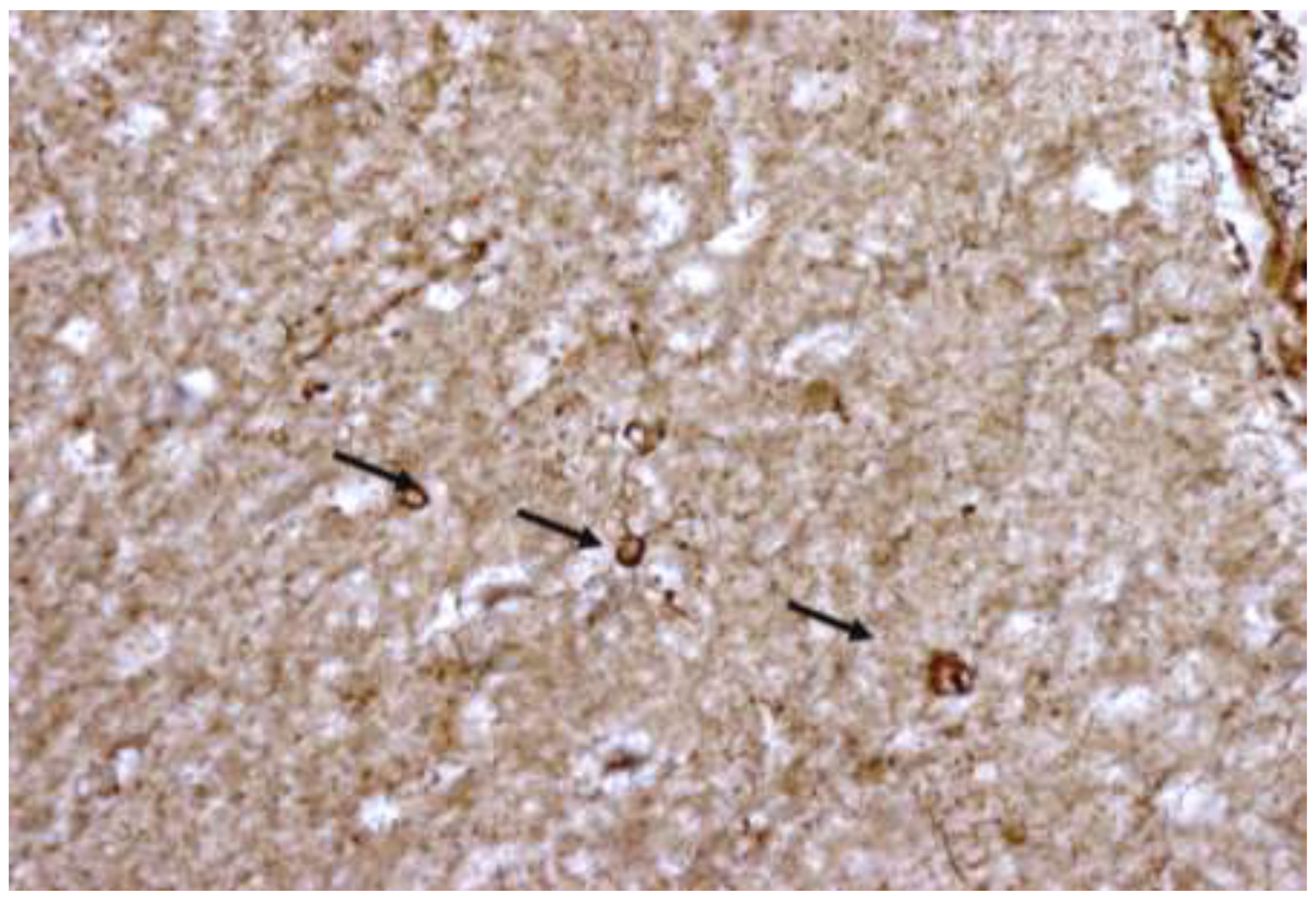

All tissues stained positively for GFAP and ezrin. The staining was confined to structures with typical star-like astroglial morphology and their processes. The GFAP (brown) staining was homogenous while the ezrin (blue-black) was generally nodular. The levels of background staining were sufficiently low to easily distinguish astrocyte profiles from the neuropil. Neurons could be seen as negative staining round silhouettes, often outlined by glial processes (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). Often several astroglia contributed to the mesh of fibers surrounding the neurons. The thin tertiary processes could be seen bordering the neurons. Because they passed out of the plane of cutting, it was not possible to fully follow an individual process around most of the neurons; however, spaces which could have been synapses were seen between adjacent GFP processes,

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5.

Nodular ezrin immunostaining (dense blue-black) was observed in all GFP-stained profiles. While the definition at the light microscopic level did not allow consistent determination, compared to the 60-minute incubated controls there was observer consensus that the staining for ezrin was qualitatively heavier in all treatment groups (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

Upon overview at 40X the highest astrocytic fiber density corresponded to the control group (

Figure 1). The raloxifene, tamoxifen and estradiol-treated tissues stained more densely for ezrin/GFAP than the controls,

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5. The number of GFAP-positive cells/area was similar for all groups, data not shown.

3.2. Quantitative Analysis

Neurolucida software together with light microscopy at 40-100X magnification was used for analysis of GFAP/ezrin staining of astrocyte profiles using the above-described pattern and protocol for designating branches. Each astrocyte and its associated processes was traced with the computer mouse, allowing the program to calculate the area, volume, and numbers and type of processes of each cell.

Cell soma -There were no differences in astrocyte nuclear (negative staining) or cytoplasmatic volumes after control, estradiol, raloxifene and tamoxifen 60-minute treatments,

Table 1.

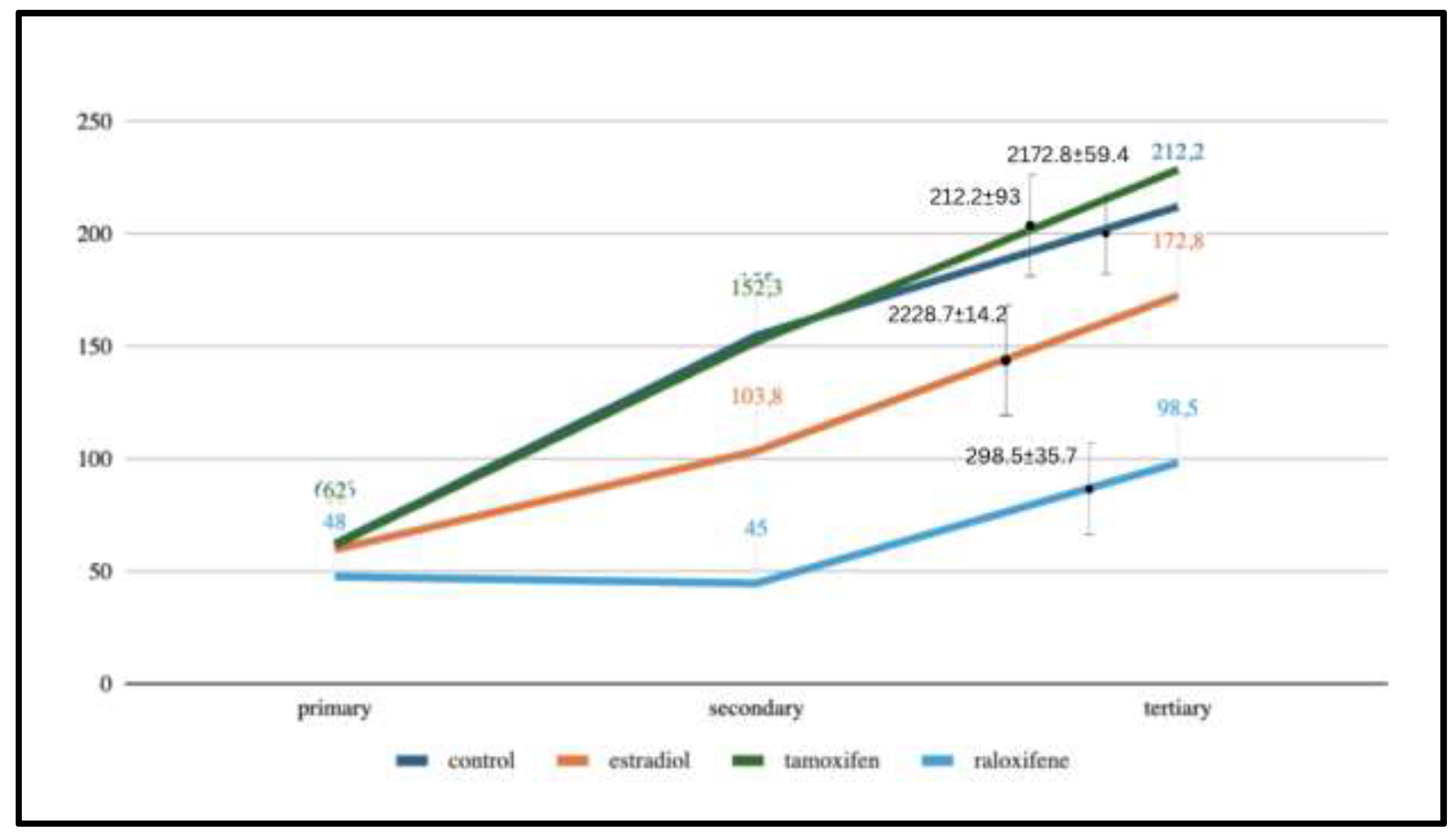

Processes – Observations included branchings (primary, secondary and tertiary processes) reported in

Table 1 and

Figure 6.

After 60 minutes of culture the profile of the results of each treatment could be characterized. All

ex vivo astroglial processes extended and thinned over the incubation period. Starting with equal numbers of primary (thick) branches in all treatment groups, the control and tamoxifen groups had developed greater numbers of both secondary and tertiary processes while the estradiol and raloxifene-treated astroglial spreading lagged behind them,

Figure 6.

After 60 minutes, branching lagged the most in the raloxifene group, with about half the number of tertiary branches compared to the controls. (primary 10.9, p=0.013); secondary (12.2, p=0.01), tertiary (5.23, p=0.05). The estradiol-treated slices showed an intermediate number of secondary and tertiary branches, that was not numerically statistically distinct from the controls the p<0.05 level,

Figure 6.

4. Discussion

Attention has long been focused on the hormonal steroids such as estradiol, since they were first discovered and amenable to direct assays. (Corker, Naftolin and Exley, 1969) Estrogen signaling in the developing brain has been shown to be critical in the sexual differentiation of embryonic and post-natal brains. (Naftolin, et al, 1975; McCarthy et al., 2002) In the hypothalamus of females, circulating estrogen-mediated remodeling of hypothalamic synaptic architecture is the driver of the estrogen-induced gonadotropin surge (“LH surge”) prior to ovulation. (Naftolin et al., 1996, 2007) In the hippocampus, high circulating estradiol levels have been shown to induce increased density of dendritic spines and synapses (Woolley et al., 1997), a relationship likely mediated at least in part by astroglial action. (Lâm and Leranth, 2003)

Since estradiol induces synaptic plasticity in monkeys (Naftolin, et al, 2007), and primate astroglia express estrogen receptors (Herbison et al., 1995), we performed short-term culture of human temporal lobe cortex slices to assess the action of three SERMs, estradiol, tamoxifen and raloxifene on human astroglial cytoskeletal components and the morphology of astroglial processes. There were differences between the actions of the three SERMs on the branching of human temporal lobe astrocyte processes; estradiol and raloxifene showed appreciable effects on astroglial morphology while tamoxifen-treated astrocytes did not differ from control tissues. At the doses used in the 60-minute culture, raloxifene-laced cultures showed a clear and numerically statistically significant reduction of secondary and tertiary astrocytic processes on quantitative image analysis. Estradiol had similar effects, but they failed to reach numerical statistical significance.

The main effectors of steroid action are the nuclear receptors, for which steroids are ligands. (Stanisic et al.,2010) In the case of estrogen action these ligands include the ovarian steroid estrogens, plant SERMs and synthetic ligands such as raloxifene and tamoxifen. The latter have drawn attention and clinical utility because of their antagonistic effects when bound to estrogen receptors. (Motlani et al.,2023) SERMs have both agonistic and agonistic effects, depending on several tissue and cell-specific factors. Selective estrogen receptor modulators are a broad and diverse group of compounds that include natural steroids and a large group of diverse compounds that bind to estrogen receptors. Some that are in general use could have unexplored agonist-antagonist actions, including effects on glial spreading and brain function. For example, the widely used anti-epilepsy medication phenytoin (Dilantin©) is a SERM whose mechanism of action could involve effects on astroglial spreading, etc. (Fadiel et al.,2015)

Knowledge of the importance and function of astrocytes has expanded dramatically in recent years. More than support cells, astrocytes are now known to be active participants in the development, survival, maintenance and function of neurons and synapses. While it is known that exposure to gonadal steroids, especially estradiol, during both neonatal and postnatal periods can modulate astroglia morphology, these effects are complex, difficult to study, and have high regional specificity. (McCarthy et al., 2002; Mong and Blutstein, 2006)

More tractable and of particular interest is the role of estrogen-regulated glial morphologic changes and synaptic complement during hypothalamic sexual differentiation of the brain (Levy et al. 1996; Garcia-Segura and McCarthy, 2004) and estrogen-induced synaptic plasticity. (Naftolin, 2007). Regarding the former, we used in vitro organ culture to show the concordance between synaptology and astroglial disposition during brain sexual differentiation (Levy et al, 1996). More recently, using a similar in vitro rodent hypothalamus model we have succeeded in using estradiol to induce the synaptic changes that occur in vivo during the pre-ovulatory LH surge. (Levy, et al., in preparation). The present report shows that in vitro methods can furnish further access to the role of astroglia in human brain synaptic plasticity.

The present results add to the growing body of literature on estrogen signaling in the brain and the emerging role of astrocytes in mediating neuronal and synaptic changes. (Levy, et al,1996; Garcia-Segura et al., 1999; McCarthy et al., 2002; Naftolin, et al., 2007; Garcia-Segura, et al , 2009; Micevych et al., 2010; Hansberg-Pastor et al., 2015; De Pittà et al., 2016; Torres, et al., 2024) Other mechanisms include neurotransmitter-induced changes in astrocyte metabolism (Torres, et al., 2024) and secretion of local factors (“gliotransmitters”) that modulate neuronal activity via paracrine effects. (Durkee and Araque, 2019; Garcia-Segura and McCarthy, 2004) All of these findings carry important implications for SERM action in blood-brain barrier integrity (Bechmann, et al., 2005) and the immune responses involved in degenerative brain diseases. Mor, et al., 1999) The brain effects of systemic estrogen treatment in menopausal women and anti-estrogen treatment during cancer therapy certainly involve effects on astroglia and have important clinical implications.

The morphologic astrocyte process changes correlated with increases in ezrin staining, implying that SERM-activated ezrin plays a role in mediating the extension and retraction of astrocytic processes. Ezrin is a ubiquitous protein belonging to the ezrin-radixin-moesin (ERM) family. Upon ligation of plasma membrane receptors, e.g. Insulin, cytokines, ezrin is activated and links the intracellular domain of the plasma membrane proteins to the actin cytoskeleton. In this way, ezrin is linked to morphological changes in cells and membrane-associated signal transduction events. (Saka et al., 2014; Tsukita & Yonemura, 1997) In the case of astrocytes, ERM proteins have been shown to organize the astrocytic plasma membrane into functional domains and to mediate both the structural and functional plasticity of peripheral astrocytic processes. (Derouiche et al., 2012; Lavialle et al., 2011) Ezrin expression is induced by estradiol (Song, et al. 2005), but short-term activation by SERMs has not previously been reported.

Finally, this preliminary study offers proof of principle that opens the door to improved understanding of effects of SERMs on other aspects of human brain function, such as the spreading of the glial podocytes of the blood-brain barrier. (Bechmann, et al. 2005)

This study has limitations. It studied only a single area of the limbic system, had limited numbers of samples, did not include multiple doses of test SERMs, and relied on light microscopic methods. However, it serves as the first reported evidence that in human brain tissues, SERMs differentially regulate the glial properties involved in synaptology and that these actions must be considered in health and disease.

In summary, this study supports the ex vivo use of human brain tissues to study the effects of SERMs and other biologicals on neuron-glia architecture. We show that during 60 minutes in culture estradiol, raloxifene, and tamoxifen exposure results in differential branching of astrocytic processes. These changes were associated with relative increases in immunoreactive GFAP and ezrin levels.

The role of estrogenic signaling on astrocyte structure and function is fundamental to both neurodevelopment and adult neural physiology, as well as a variety of neurologic diseases. We and others have proposed that astroglial spreading and retraction regulate the number and size of synapses on neurons and their processes. Since SERMs and estrogen receptors are fundamental to every living creature, further delineation of the functional consequences of SERM-induced astrocyte remodeling is an important topic for further study.

Contributions to the project

I.S. developed the project, performed the laboratory work and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. FN conceived the project, participated in the laboratory studies and in the preparation of the manuscript. A.W. oversaw and performed laboratory studies A.F. performed laboratory studies and participated in evaluation and manuscript preparation. D.S. obtained and oversaw the preparation of tissues and contributed to the manuscript. H.J.L. performed evaluation of the results and contributed to the manuscript.

Conflicts

None of the authors have conflicts.

Acknowledgments

This project was carried out in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT. and supported by NIH AG 154057 to F.N. The assistance of Marya Shanabrough is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- Alvarez-de-la-Rosa M, Silva I, Nilsen J, Perez MM, Garcia-Segura LM, Avila J, Naftolin F. Estradiol prevents neural tau hyperphosphorylation characteristic of Alzheimer's disease. (2005) Ann N Y Acad Sci 1052:210-24.

- Bechmann, I, Goldmann, J, Kovac, AD, Kwidzinski, E, Simburger, E, Naftolin, F, Dirnagl, U, Nitsch, R., Priller, J. Circulating monocytic cells infiltrate layers of anterograde axonal degeneration where they transform into microglia (2005) FASEB j. 19(6):647-649.

- Chowen, J.A.; Garcia-Segura, L.M. Role of glial cells in the generation of sex differences in neurodegenerative diseases and brain aging. (2021) Mech. Ageing Dev. 196, 111473.

- Corker CS, Naftolin F, Exley D. Interrelationship between plasma luteinizing hormone and oestradiol in the human menstrual cycle. (1969) Nature 222(198):1063.

- de Lanerolle, N. C., Kim, J. H., Robbins, R. J., Spencer, D. D. Hippocampal interneuron loss and plasticity in human temporal lobe epilepsy. (1989) Brain Research, 495(2), 387–395. [CrossRef]

- De Pittà, M., Brunel, N., Volterra, A. Astrocytes: Orchestrating synaptic plasticity? (2016) Neuroscience, 323, 43–61. [CrossRef]

- Derouiche, A., Pannicke, T., Haseleu, J., Blaess, S., Grosche, J., Reichenbach, A. Beyond polarity: Functional membrane domains in astrocytes and Müller cells. (2012) Neurochemical Research, 37(11), 2513–2523. [CrossRef]

- Durkee, C. A., Araque, A. Diversity and Specificity of Astrocyte-neuron Communication. (2019) Neuroscience, 396, 73–78. [CrossRef]

- Fadiel, A.; Song, J.; Tivon, D.; Hamza, A.; Cardozo, T.; Naftolin, F. Phenytoin is an estrogen receptor α-selective modulator that interacts with helix 12. (2015) Reprod Sci;22(2):146-55. Epub 2014 Sep 25. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Segura, L. M., McCarthy, M. M. Minireview: Role of glia in neuroendocrine function. (2004) Endocrinology, 145:1082–1086. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Segura, L. M., Naftolin, F., Hutchison, J. B., Azcoitia, I., Chowen, J. A. Role of astroglia in estrogen regulation of synaptic plasticity and brain repair. (1999) Journal of Neurobiology, 40:574–584.

- Hansberg-Pastor, V., González-Arenas, A., Piña-Medina, A. G., Camacho-Arroyo, I. Sex Hormones Regulate Cytoskeletal Proteins Involved in Brain Plasticity. (2015) Frontiers in Psychiatry, 6, 165. [CrossRef]

- Herbison A.E.; Horvath, T.L.; Leranth, C. Distribution of estrogen receptor-immunoreactive cells in monkey hypothalamus: relationship to neurons containing luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone and tyrosine hydroxylase. (1995) Neuroendocrinology;61(1):1-10. [CrossRef]

- Lâm, T. T., Leranth, C. Gonadal hormones act extrinsic to the hippocampus to influence the density of hippocampal astroglial processes. (2003) Neuroscience, 116:491–498. [CrossRef]

- Lavialle, M., Aumann, G., Anlauf, E., Pröls, F., Arpin, M., Derouiche, A. Structural plasticity of perisynaptic astrocyte processes involves ezrin and metabotropic glutamate receptors. (2011) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108:12915–12919. [CrossRef]

- Lee K, Park TI, Heppner P, Schweder P, Mee EW, Dragunow M, Montgomery JM. Human in vitro systems for examining synaptic function and plasticity in the brain. (2020).J Neurophysiol 123: 945–965.

- Levy, A.; Garcia-Segura, M.; Nevo, Z.; David, Y.; Shahar, A.; Naftolin. F. Action of steroid hormones on growth and differentiation of CNS and spinal cord organotypic cultures. (1996) Cell Mol Neurobiol.; 16(3):445-50.

- McCarthy, M. M., Amateau, S. K., Mong, J. A. Steroid modulation of astrocytes in the neonatal brain: Implications for adult reproductive function. (2002) Biology of Reproduction, 67: 691–698. [CrossRef]

- Micevych, P., Bondar, G., Kuo, J. Estrogen actions on neuroendocrine glia. (2010) Neuroendocrinology, 91:211–222. [CrossRef]

- Middeldorp, J., Hol, E.M. GFAP in health and disease (2011) Progress In Neurobiology 93:421-443.

- Mong, J. A., Blutstein, T. Estradiol modulation of astrocytic form and function: Implications for hormonal control of synaptic communication. (2006) Neuroscience, 138:967–975. [CrossRef]

- Mor G, Nilsen J, Horvath T, Bechmann I, Garcia-Segura LM, Naftolin F. Estrogen and microglia: A regulatory system that affects the brain. (1999) J Neurobiol 40(4):484-96.

- Motlani, G.; Motlani, V.; Acharya, N.; Dave, A.; Pammani, S.; Somyani, D.; Agrawal, S. Novel Advances in the Role of Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators in Hormonal Replacement therapy: A Paradign Shift. (2023) Cereus;19;15(11):e49079. eCollection 2023. [CrossRef]

- Naftolin F, Ryan KJ, Davies IJ, Reddy VV, Flores F, Petro Z, Kuhn M, White RJ, Takaoka Y, Wolin L. The formation of estrogens by central neuroendocrine tissues. (1975) Recent Prog Horm Res 31:295-319.

- Naftolin, F., Garcia-Segura, L. M., Horvath, T. L., Zsarnovszky, A., Demir, N., Fadiel, A., Leranth, C., Vondracek-Klepper, S., Lewis, C., Chang, A., Parducz, A. Estrogen-induced hypothalamic synaptic plasticity and pituitary sensitization in the control of the estrogen-induced gonadotrophin surge. (2007 Reproductive Sciences (Thousand Oaks, Calif.), 14:101–116. [CrossRef]

- Naftolin, F.; Garcia-Segura, L.M.; Keefe, D.; Leranth, C.; Maclusky, N. J.; Brawer, J.R. Estrogen effects on the synaptology and neural membranes of the rat hypothalamic arcuate nucleus. (1990). Biol Reprod;42(1):21-8. [CrossRef]

- Naftolin, F., Mor, G., Horvath, T. L., Luquin, S., Fajer, A. B., Kohen, F., Garcia-Segura, L. M. Synaptic remodeling in the arcuate nucleus during the estrous cycle is induced by estrogen and precedes the preovulatory gonadotropin surge. (1996) Endocrinology, 137:5576–5580. [CrossRef]

- Rodrı´guez, J.J., Olabarria, M., Chvatal, A., Verkhratsky, A. Astroglia in dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. (2009) Cell Death and Differentiation 16:378–385.

- Saka, S. K., Honigmann, A., Eggeling, C., Hell, S. W., Lang, T., Rizzoli, S. O. Multi-protein assemblies underlie the mesoscale organization of the plasma membrane. (2014) Nature Communications, 5, 4509. [CrossRef]

- Shi, H., Mirzaei, N., Koronyo, Y. et al. Identification of retinal oligomeric, citrullinated, and other tau isoforms in early and advanced AD and relations to disease status. (2024) Acta Neuropathol 148, 3. [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Fadiel, A.; Edusa, V.; Chen, Z.; So, J.; Sakamoto, H.; Fishman, D.A., Naftolin, F. Estradiol-induced ezrin overexpression in ovarian cancer: a new signaling domain for estrogen. (2005) Cancer Lett;220(1):557-65. [CrossRef]

- Spencer, D. D., Spencer, S. S., Mattson, R. H., Williamson, P. D., Novelly, R. A. Access to the posterior medial temporal lobe structures in the surgical treatment of temporal lobe epilepsy. (1984) Neurosurgery, 15:667–671. [CrossRef]

- Stanisic, V.; Lonard, D.M., O'Malley, B.W. Modulation of steroid hormone receptor activity. (2010) Prog Brain Res; 181:153-76.doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)81009-6.

- Torres, E.; Pellegrino, G.; Granados-Rodríguez, M.; Fuentes-Fayos, A. C.; Velasco, I.; Coutteau-Robles, A.; Legrand, A.; Shanabrough, M.; Perdices-Lopez, C.; Leon, S.; Yeo, S. H.; Manchishi, S.M.; Sánchez-Tapia, M.J.; Navarro, V.M.;Pineda, R.; Roa, J.; Naftolin, F.; Argente, J.; Luque, R.M.; Chowen, J.A.; Horvath, T.L.; Prevot, V.; Sharif, A.; Colledge, W.H.; Tena-Sempere, M.; Romero-Ruiz, A. Kisspeptin signaling in astrocytes modulates the reproductive axis. (2024) J Clin Invest. Aug 1; 134(15): e172908. PMCID:PMC11291270. [CrossRef]

- Tsukita, S., & Yonemura, S. ERM (ezrin/radixin/moesin) family: From cytoskeleton to signal transduction. (1997) Current Opinion in Cell Biology, 9:70–75. [CrossRef]

- Wiktorowicz, J. E., Sadygov, R. G., Zivadinovic, D., Paulucci-Holthauzen, A. A., Vergara, L., Nesic, O. The cancer drug tamoxifen: A potential therapeutic treatment for spinal cord injury. (2014) Journal of Neurotrauma, 31:268–283. [CrossRef]

- Williamson, A., Patrylo, P.R., Pan J., Spencer, D.D., HetheringtonI, H. Correlations between granule cell physiology and bioenergetics in human temporal lobe epilepsy (2005) Brain 128:1199-208. [CrossRef]

- Woolley, C. S., Weiland, N. G., McEwen, B. S., Schwartzkroin, P. A. Estradiol increases the sensitivity of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells to NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic input: Correlation with dendritic spine density. (1997) J. Neuroscience 17:1848–1859.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).