1. Introduction

Synchronization phenomena are abundant in nature ranging from brain science [

1] to power grids [

2]. Describing them via toy models has a long history, for recent reviews see [

3,

4]. One of the simplest and well known is introduced by Kuramoto [

5]. In its original form it is a fully coupled system defined on a full graph. The synchronization transitions of the locally coupled versions were studied on finite dimensional lattices [

6]. In homogeneous systems the Kuramoto model exhibits

, that means real phase transition can happen above

and it is mean-field type. Entrainment transition of frequency variables can be non-mean-field like for

.

On heterogeneous, random graphs the phase transition remains mean-field like [

7] according to the annealed heterogeneous mean-field approximation, however care must be taken even in dense-network systems, particularly in the disordered phase [

8]. By studying the dynamical scaling of Kuramoto on Erdős Rényi graphs non-monotonic corrections to scaling hindered to see clearly mean-field criticality even on very large systems [

9]. Note the disorder here is different from other ‘disordered’ Kuramoto models studied in the literature, where the disorder arises from independent random positive and negative couplings, which add frustration to the system and can lead to glassy dynamics [

10].

In lower dimensional, simplicial complex model of manifolds complexes [

11] and on hierarchical modular networks [

12,

13] a so-called frustrated synchronization transition was reported for spectral dimension

. Ref [

14] showed that synchronized phase can only be thermodynamically stable for spectral dimensions above four and that phase entrainment of the oscillators can only be found for spectral dimensions greater than two. Very recently Ref. [

15] studied one-dimensional long-range random ring networks, where any two nodes on the network are connected with a probability proportional to a power law of the distance between the nodes and confirmed the results of [

14] for the Kuramoto model.

On a large, weighted human connectome network, containing 804 092 nodes, the topological dimension is

, a real synchronization phase transition is not possible in the thermodynamic limit, still a transition between partially synchronized and desynchronized states could be found, with non-universal coupling dependent dynamical scaling [

16]. On the other hand on the infinite dimensional “2dll” random long link model of lateral size

Kuramoto calculations, starting from states with oscillators of fully random phases the growth exponent at the synchronization transition point was found to be

, away from the mean-field expectations by scaling relations:

[

17]. It was suspected that finite size scaling and corrections hid the true mean-field behavior numerically in [

16] as well as in [

17]. Here we provide a more extended numerical study with the aim of clarifying this .

2. Materials and Methods

The model introduced by Kuramoto [

5] is one of the most studied for oscillatory systems. Besides the original global coupled system one can define a locally coupled version on graphs [

3], in which phases

, located at the

N nodes of a network, follow the dynamical equation

The global coupling

K is the control parameter, by which one can tune the system between asynchronous and synchronous states. The summation is performed over the nearest neighboring nodes, with connections described by the adjacency matrix

and

denotes the quenched self frequency of the

i-th oscillator, chosen from a Gaussian distribution, with zero mean and unit variance. When

describes a full graph, the dynamical behavior is mean-field type [

18]. The critical dynamical behavior has been explored on various random graphs [

16,

17]. In regular lattices synchronization phase transition can happen only above the lower critical dimension

[

6]. In lower dimensions, a true, singular phase transition in the

limit is not possible, but partial synchronization emerges with a smooth crossover if the oscillators are coupled strongly.

To investigate the relaxation to the steady state, we measured

where

gauges the overall coherence and

is the average phase at discrete sampling times

, which was chosen to follow an exponential growth:

to spare memory space.

The sets of equations (

1) were solved numerically for

independent initial conditions, initialized by different

-s and random initial phases

were used. Then sample averages for the phases and the frequencies give rise to the Kuramoto order parameter

which is non-zero above the critical coupling strength

, tends to zero for

as

, or exhibits a growth at

as

in case of an incoherent initial state, with the dynamical exponents

and

. We also measured the variance of the frequencies

which is expected to exhibit an asymptotic decay law

in the ordered phase, by linear approximation [

17], and is also confirmed numerically in the nonlinear regime [

17,

19].

The Kuramoto differential equation system (

1) was solved using the adaptive Bulirsch–Stoer stepper [

20] implemented with support for CUDA GPUs boost::odeint [

21] via the VexCL library [

22]. Node and edge information of sparse random graphs were stored using a memory layout optimized for the efficient parallel evaluation of the Kuramoto computation of interaction term. This implementation allowed the numerical treatment of large systems with

nodes and containing up to

edges, while sampling thousands of realizations per graph type on a small GPU cluster.

2.1. The power-Law Decaying Long Range Graph (ll)

Graphs with variable topological and spectral dimension can be generated by the addition of long-range connections with probability decaying with the distance

l algebraically as

parametrized by the exponent

s, see for example [

23]. We used this method by the addition of links to two dimensional lattices, with periodic boundary conditions and linear sizes

. For

, infinite graph dimensions are obtained. The probability of long-range links decreases as

s increases and for

, any long-range links are suppressed to simply give the original underlying two-dimensional lattice. This construction provides the possibility to generate systems with their dimensionalities vary from 2 to

∞ at

by tuning

. As for the spectral dimension the situation is different as we will show it in

Sect. 3.1

2.2. Spectral Analysis

The spectrum of the Laplacian matrix of a complex network encapsulate vital information about the network’s structural properties, such as its connectedness and connectivity, its ability to synchronize or conduct diffusion processes, and its resilience to structural perturbations, etc [

24]. In particular it is related to the linearized Kuramoto equation, which describes a random walk. Such spectra were also shown to encode the dimensionality information of a network [

25]. Following Refs. [

11,

14], we adopt the normalized Laplacian

L with elements

for unweighted networks, where

denotes the degree of node

i. The normalized Laplacian has real eigenvalues

that form a spectrum, the density of which is characterized by the following scaling behavior [

11,

25]

for

, where

is the spectral dimension. The cumulative density is then given by

Note, that the smallest nonzero eigenvalue

or the Fiedler value quantifies the connectivity of the network. In connected networks with finite spectral dimensions, the dimension

is an overall measure for the local connectivity, while as the system size

N increases, the resulting larger network will also have more room for disconnection, giving rise to a smaller

. Therefore,

depends on both

and

N. By imposing

(the cumulative density of this smallest nonzero eigenvalue over

N eigenvalues),

then scales with the network size according to the following power law [

14].

More generally, in order for the spectrum to display the power-law behavior (

8) and (

9), each eigenvalue should follow the similar leading-order scaling [

26]

3. Results

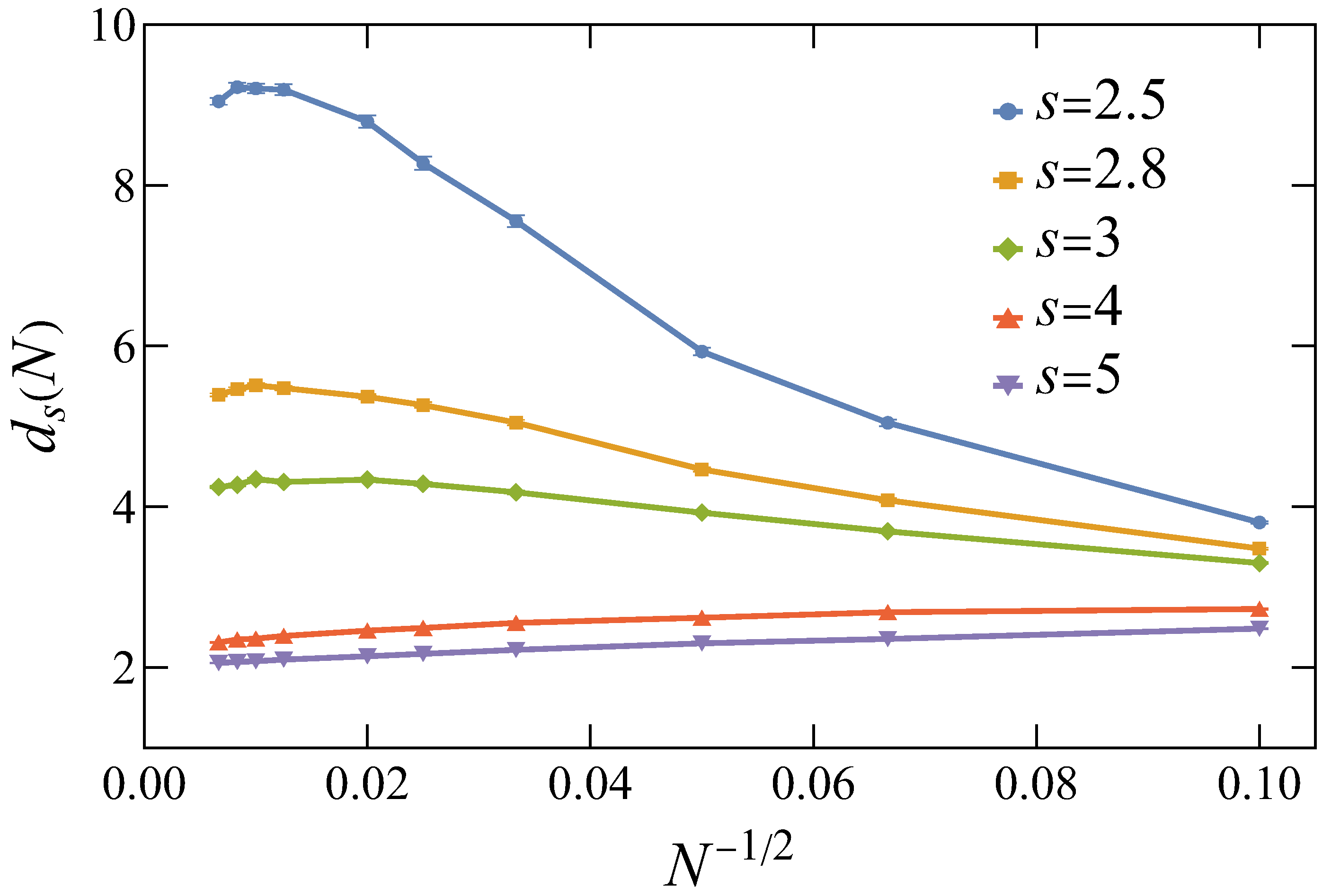

3.1. Spectral Analysis Results

Equations (

8)-(

11) all suffice for the estimation of the spectral dimension. However, since

values obtained from Equations (

8) and (

9) may depend on how many low-lying eigenvalues are chosen, these two scaling relations are not very reliable. In practice, it is more apt to utilize the finite-size scaling relations (

10) and (

11) to obtain

by observing how the scaling exponents converge as

. In

Figure 1, we applied Equation (

10) to estimate the dependence of

on

N for different

s values, which shows that the scaling form Equation (

10) only gives a consistent, reliable

value by extrapolating to the thermodynamic limit

. It also shows that the intended upper critical dimension

for this study corresponds to choosing

.

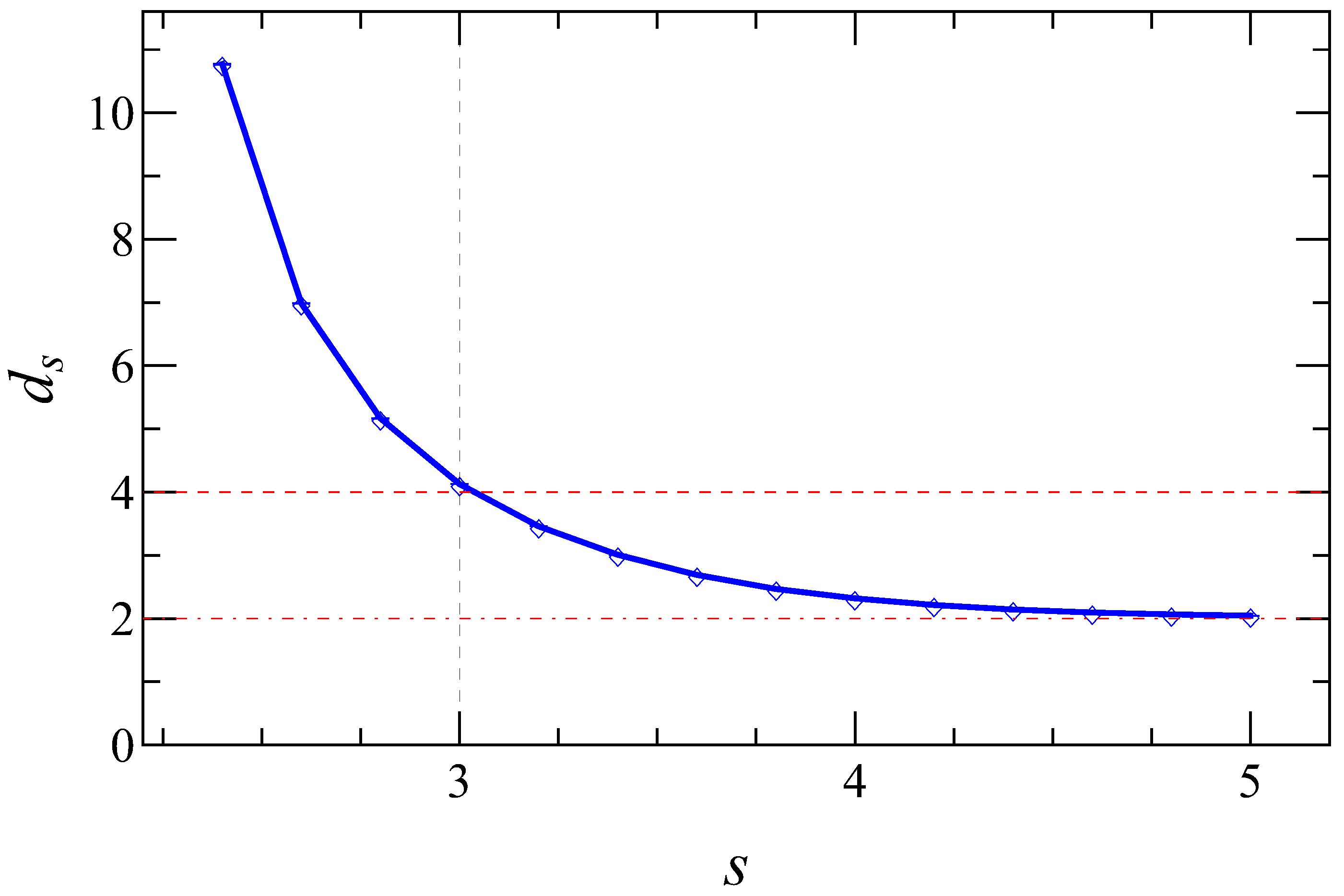

To more systematically determine how

varies with

s in the thermodynamic limit, we may estimate

according to Equation (

11) with respect to several eigenvalues for large enough system sizes. From the results of

Figure 1, taking

, and

should give reasonable estimations, while pushing the lateral size

L to even larger values will be rather computing resource demanding for eigenvalue calculations. The resulting

Figure 2 (see the caption for the calculation details) shows that

decreases monotonously with respect to

s and tends to the dimensionality of the underlying two-dimensional lattice for large

s, as expected according to

Section 2.1. This figure further justifies that

for

and

for

in agreement with the relevancy of the long links. In

Section 3.3, we shall take

as we intend to study synchronization dynamics on networks with

.

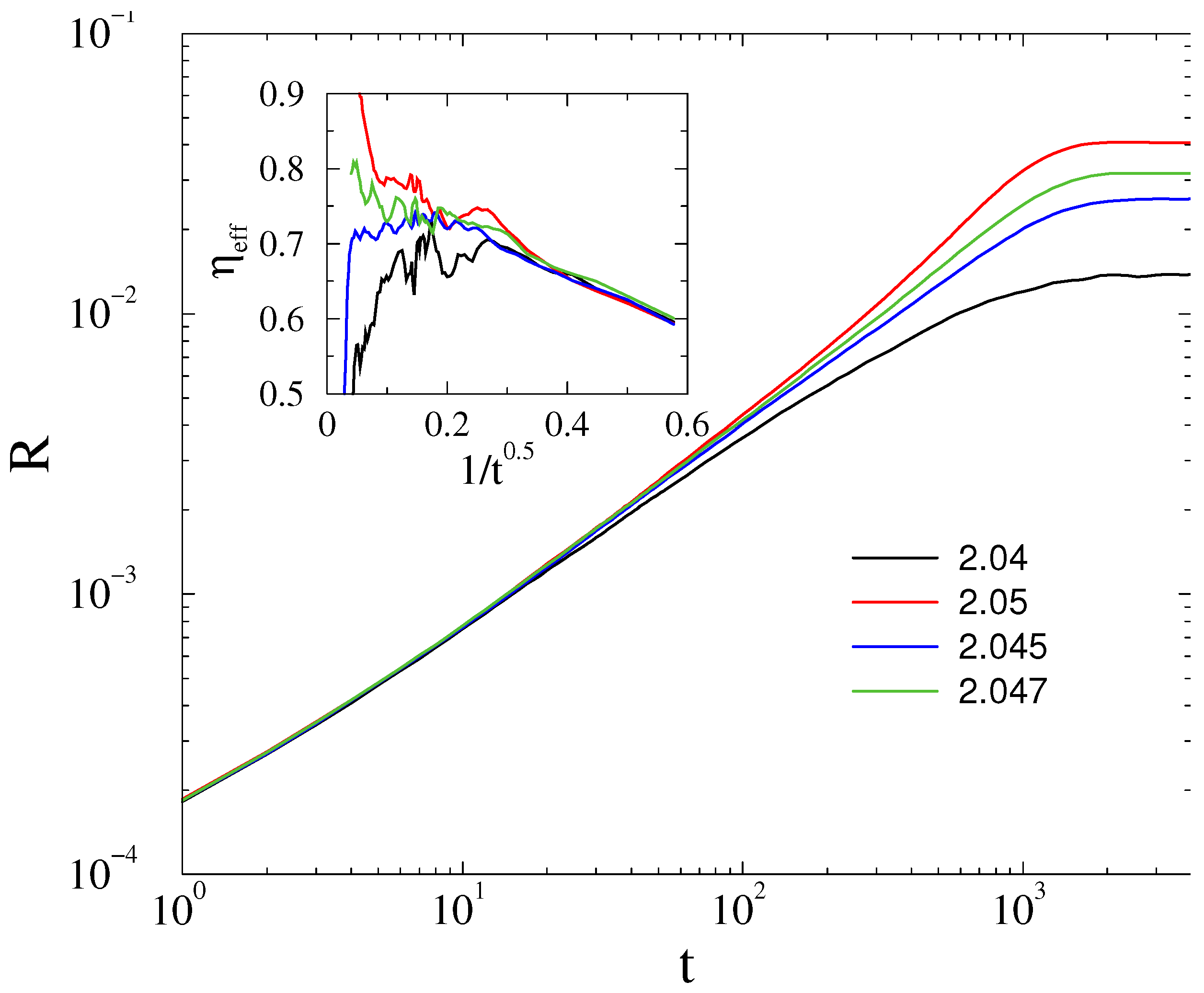

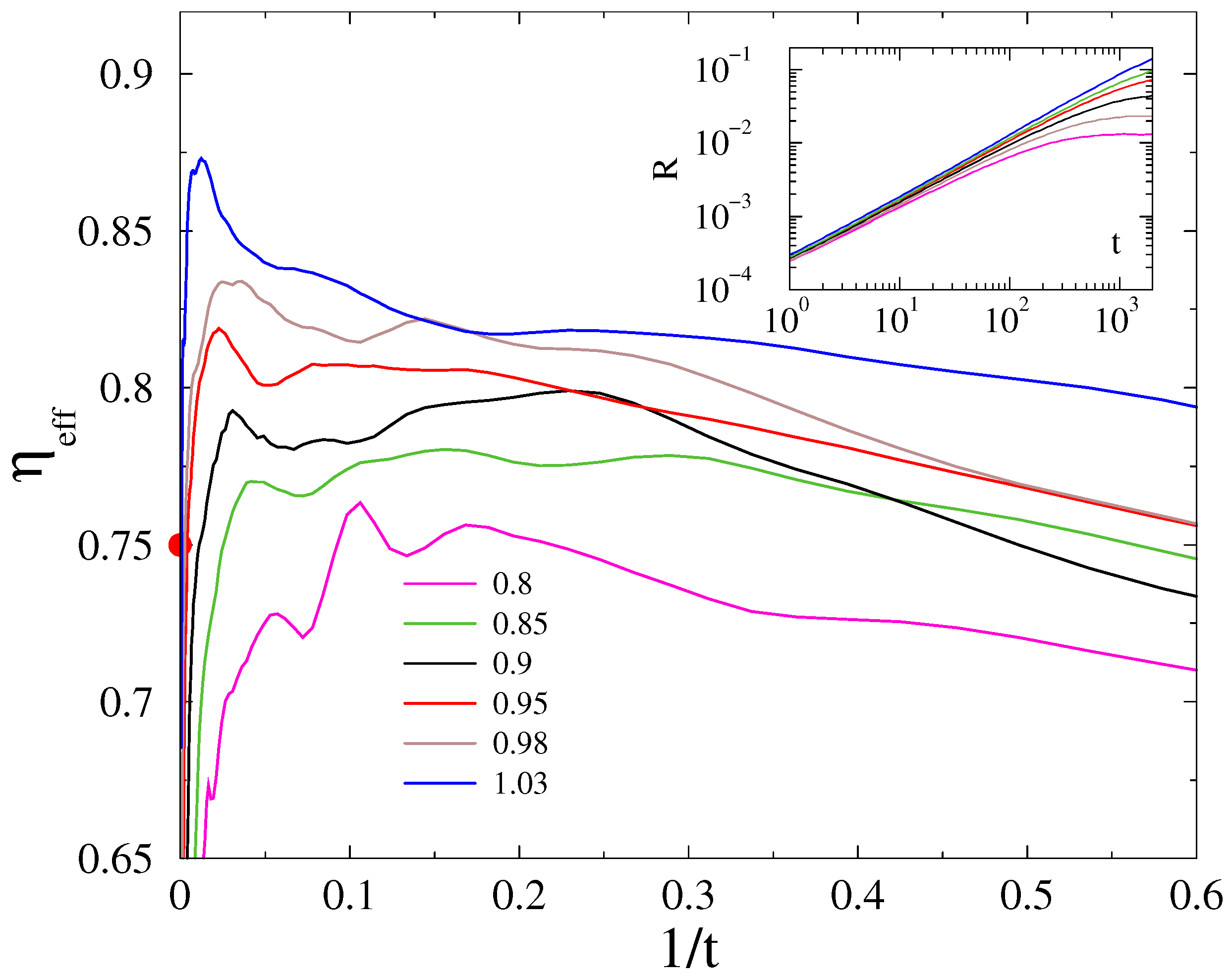

3.2. Regular Lattice Kuramoto Order Parameter Behavior

First we solved Equation (

1) in case of 5 dimensional lattices, where the mean-field type of behavior is expected. We initialized the solver by random initial phases and followed the evolution of

up to

time steps. We performed these calculations for

linear sizes, for thousands of independent random initial conditions. Here we show the results of

on

Figure 3, because for

the cutoff happens at earlier times. Using a local slope analysis, defined by the logarithmic derivatives of the growth Equation (

4) at the discrete time-steps

, near the transition point

we estimated

as well as the exponent

. After selecting a proper rescaling of the horizontal axis, we can observe a linear infelxion curve at

, separating the up and down veering curves, corresponding to super and sub-critical cases and we can extrapolate to

in the

limit. The initial growth

behavior, similar as in [

17], leads to a strong corrections to scaling. Note, that simple power-law fit on the

would provide a smaller growth exponent. Our results is the first one to show clearly the expected asymptotic mean-field scaling, because analyses on smaller sizes hindered to see it due to the corrections and early time cutoff.

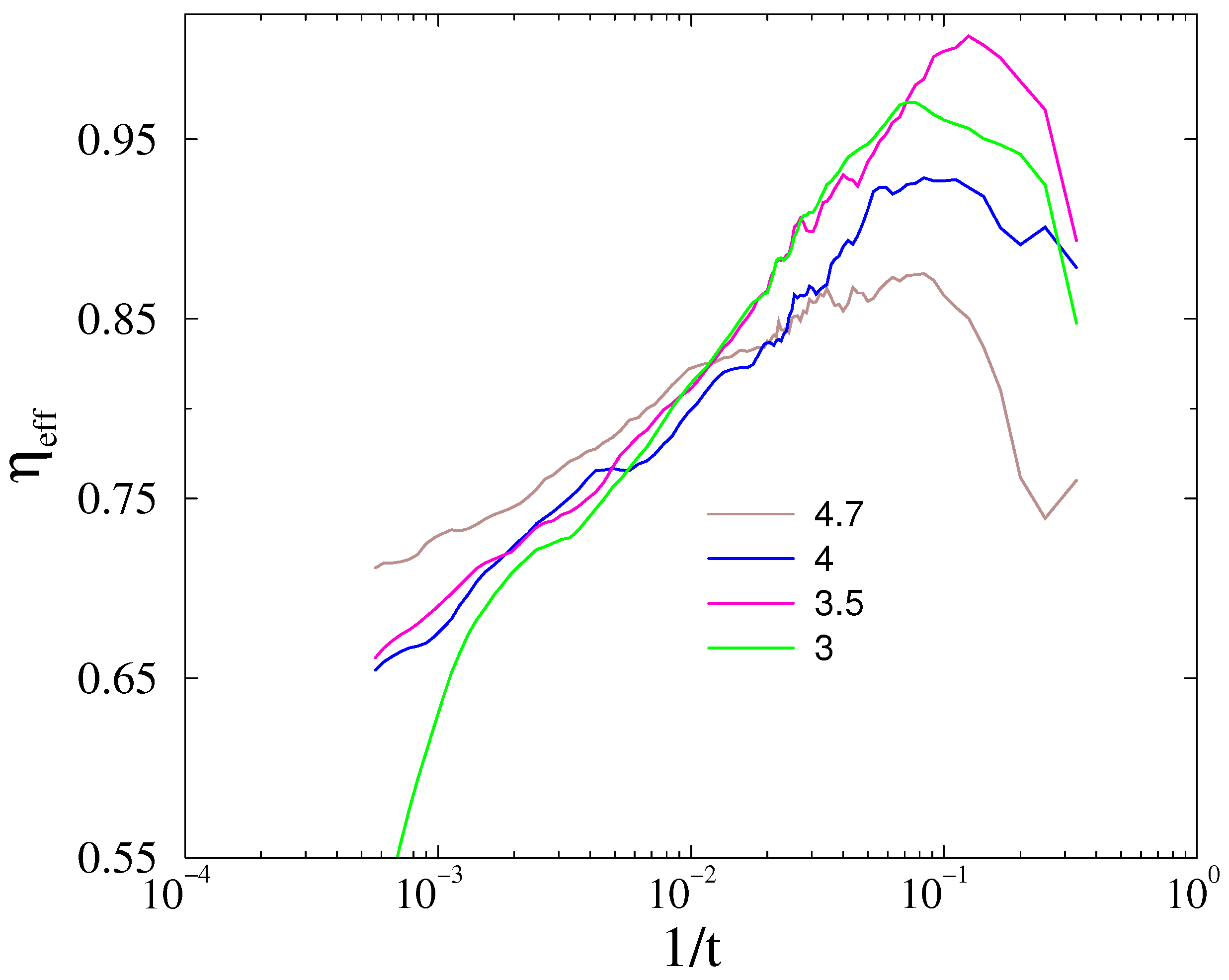

We repeated this analysis for

, but here the expected logarithmic corrections at

make the scaling even more complex. We show only the effective exponents for the calculations of

lattices on

Figure 4, again after a sample average of 1000-5000 independent initial conditions. By rescaling the horizontal axis on the logarithmic scale we can see an inflexion curve at

that may indicate the expected behavior at

, but care must be taken due to unknown finite size cutoff. Thus we just claim that our numerical results canconfirm the mean-field behavior, with logarithmic corrections.

3.3. The ll Graph Order Parameter Results

Now we show our results for the ll graph, where we used large two dimensional base lattices, with maximum linear sizes

and added PL decaying random long links with exponent

, corresponding to

, according to the spectral analysis shown in

Section 3.1. Thus, one would expect to see a simple mean-field behavior, instead as

Figure 5 shows, we find a smeared transition, without any clear separatrix extrapolating to the mean-field value

in the infinite time limit. Unlike in the regular lattice cases the local slope curves seem to saturate in the region

and

before the finite time cutoff. But the curves also exhibit wavy modulations, which persist even after averaging over 2000 independent samples, and which prohibits to extend the calculations further.

Such wavy modulations, non-monotonic corrections in the local exponents were also present in case of Kuramoto on random Erdős-Rényi graphs [

9], where the authors could not clearly justify relevant deviations from the mean-field behavior, which is present here. Solving Kuramoto on ll graphs with smaller

s values runs into rapidly increasing computational difficulties, as it requires larger memory and the communication via long links becomes slow.

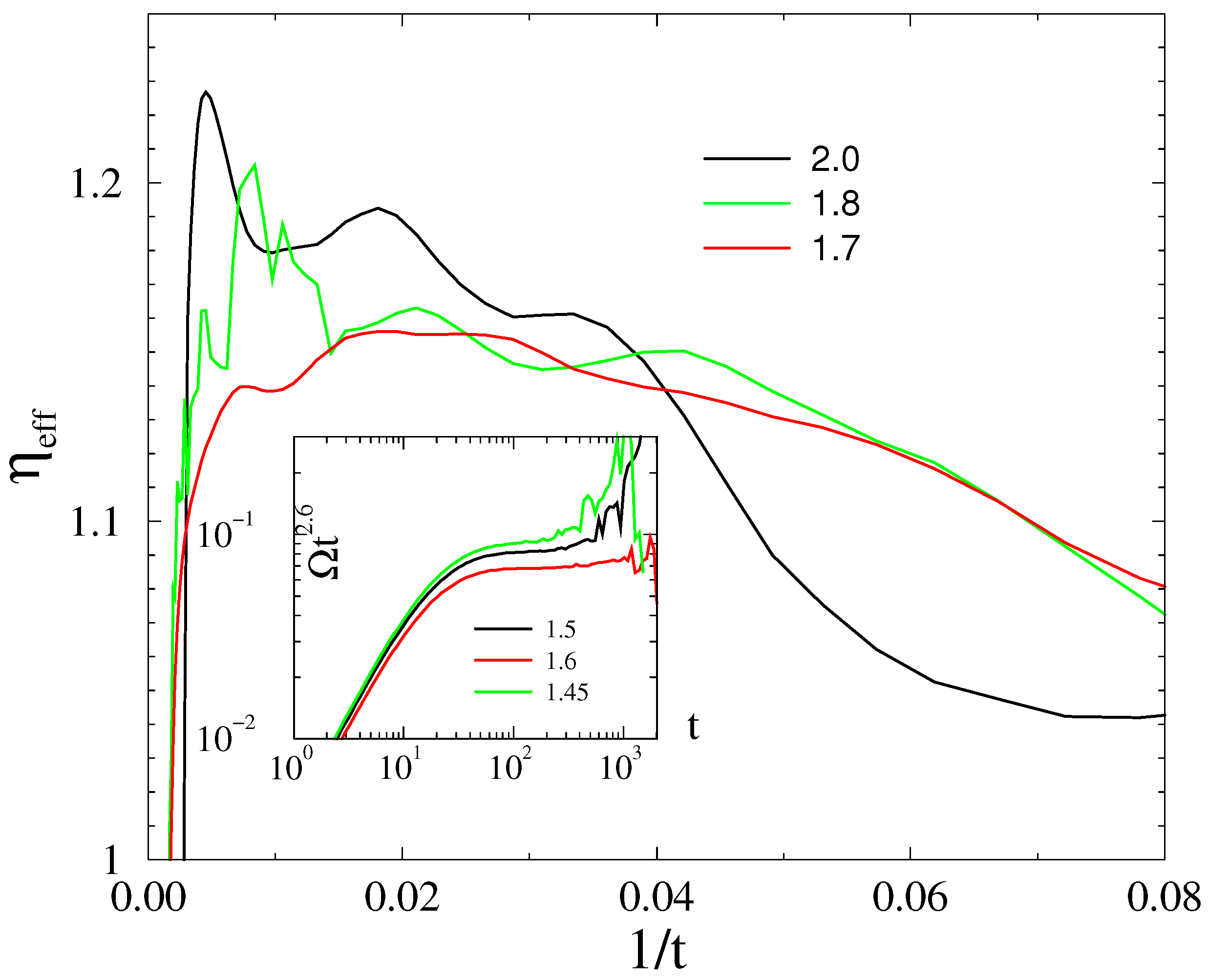

We have also obtained results for

resulting in a higher spectral dimension, where the deviations from the mean-field are even more obvious as shown on

Figure 6.

Although we have results for a limited number of couplings, and the corrections are wavy, the results suggest a critical point at , with the corresponding exponent , far away from the mean-field value . This resolution of data does not allow us to see a stretched (smeared) dynamical critical region as in case of .

For

the scaling region of

is even more narrow, instead of that we show in the inset of

Figure 6 the evolution of the frequency spread, multiplied by

in system with with

, for which PL decay can be found in case of

. The linear approximation predicts

for Euclidean lattices, below

[

17], and the observed behavior agrees well with the spectral dimension

, in case of

and contradicts with the mean-field behavior

again.

4. Discussion

In conclusion we have compared the synchronization transition of the Kuramoto model at and above the upper critical dimension and found numerical evidence that the quenched topological disorder is relevant and a smeared, frustrated phase transition seems to emerge instead of the mean-field behavior. This appears even more clearly on lattices of the

spectral dimensions. Note, however that an oscillating correction to scaling is also present in the effective exponents, which makes it more difficult to analyze data even if we consider very large sizes and averages over thousands of independent initial conditions. Previously such oscillations were also shown in earlier numerical results of the dynamical Kuramoto [

17] model on lattices, as well as on random graphs [

9]. To show the dimensional equivalence we determined the spectral dimension on ll graphs, but note that topological and graph dimensions are expected to be equal on regular graphs. The graph dimension of the

ll graphs considered here is infinite. The existence of such frustrated phase transition at high dimension is crucial for understanding models of the brain and warrants further investigations in this direction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.Ó.; methodology, G.Ó. and S.D.; software, J.K.; validation, G.Ó., S.D.; investigation, G.Ó. and S.D.; resources, G.Ó.; data curation, J.K.; writing—original draft preparation, G.Ó.; writing—review and editing, G.Ó, S.D. and J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was founded by the National Research, Development and Innovation Office NKFIH under Grant No. K146736 and was partially supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of China under Grant No. GK202406016.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data is available from the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Róbert Juhász for helpful discussions and KIFÜ for the usage of the Hungarian supercomputer Komondor.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Deco, G.; Jirsa, V.K. Ongoing Cortical Activity at Rest: Criticality, Multistability, and Ghost Attractors. Journal of Neuroscience 2012, 32, 3366–3375. Available online: https://www.jneurosci.org/content/32/10/3366.full.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arenas, A.; Díaz-Guilera, A.; Kurths, J.; Moreno, Y.; Zhou, C. Synchronization in complex networks. Phys. Rep. 2008, 469, 93–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acebrón, J.; Bonilla, L.; Vicente, C.; Ritort, F.; Spigler, R. The Kuramoto model: A simple paradigm for synchronization phenomena. Reviews of Modern Physics 2005, 77, 137–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikovsky, A.; Kurths, J.; Rosenblum, M.; Kurths, J. Synchronization: A Universal Concept in Nonlinear Sciences; Cambridge Nonlinear Science Series, Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Kuramoto, Y. Chemical Oscillations, Waves, and Turbulence; Springer Series in Synergetics, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2012.

- Hong, H.; Park, H.; Choi, M. Collective synchronization in spatially extended systems of coupled oscillators with random frequencies. Physical Review E - Statistical, Nonlinear, and Soft Matter Physics 2005, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Um, J.; Hong, H.; Park, H. Nature of synchronization transitions in random networks of coupled oscillators. Phys. Rev. E 2014, 89, 012810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Um, J.; Hong, H.; Park, H. Validity of annealed approximation in a high-dimensional system. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 6816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juhász, R.; Kelling, J.; Ódor, G. Critical dynamics of the Kuramoto model on sparse random networks. Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment 2019, 2019, 053403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daido, H. Superslow relaxation in identical phase oscillators with random and frustrated interactions. Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science 2018, 28, 045102. Available online: https://pubs.aip.org/aip/cha/article-pdf/doi/10.1063/1.5009685/14617267/045102_1_online.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millán, A.P.; Torres, J.J.; Bianconi, G. Complex network geometry and frustrated synchronization. Scientific reports 2018, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villegas, P.; Moretti, P.; Muñoz, M. Frustrated hierarchical synchronization and emergent complexity in the human connectome network. Scientific Reports 2014, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millán, A.; Torres, J.; Bianconi, G. Complex Network Geometry and Frustrated Synchronization. Scientific Reports 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millán, A.P.; Torres, J.J.; Bianconi, G. Synchronization in network geometries with finite spectral dimension. Physical Review E 2019, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, M.; Enss, T.; Defenu, N. Universality of critical dynamics on a complex network. Phys. Rev. B 2024, 110, 014208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ódor, G.; Kelling, J. Critical synchronization dynamics of the Kuramoto model on connectome and small world graphs. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 19621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, C.; Ha, M.; Kahng, B. Extended finite-size scaling of synchronized coupled oscillators. Physical Review E - Statistical, Nonlinear, and Soft Matter Physics 2013, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, H.; Chaté, H.; Park, H.; Tang, L.H. Entrainment transition in populations of random frequency oscillators. Physical Review Letters 2007, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, S.; Ódor, G. Chimera-like states in neural networks and power systems. Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science 2024, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- P., D. Order and stepsize control in extrapolation methods. Numerische Mathematik 1983, 41, 399–422.

- Ahnert, K.; Mulansky, M. Boost::odeint.

- Demidov, D. VexCL.

- Juhász, R. Competition between quenched disorder and long-range connections: A numerical study of diffusion. Physical Review E 2012, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, F.R. Spectral graph theory; Vol. 92, American Mathematical Soc., 1997.

- Burioni, R.; Cassi, D. Universal properties of spectral dimension. Physical review letters 1996, 76, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millán, A.P.; Gori, G.; Battiston, F.; Enss, T.; Defenu, N. Complex networks with tuneable spectral dimension as a universality playground. Physical Review Research 2021, 3, 023015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).