Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic caused widespread disruption, significantly impacting the routines and education of children and adolescents worldwide. One of the most notable changes was the shift to distance learning to maintain physical distancing and manage the spread of the virus (Qian & Jiang, 2022; Hume et al., 2023). In Saudi Arabia, this transition was mandated for all K–12 schools and higher education institutions starting March 8, 2020. The duration of remote learning varied between 1.5 and 2.5 academic years, depending on factors such as students’ age, vaccination status, and the educational system they were enrolled in, as documented by the Ministry of Education (MOE) in its report on efforts to combat COVID-19 (The Saudi MOE leading efforts to comb...).

In the early stages of the pandemic, numerous studies sought to assess the mental health impact of distance learning on students. For example, a survey of 612 adolescents aged 13 to 18 in the United Kingdom reported mental health symptoms in 53.3% of females and 44.0% of males. Anxiety affected 59.6% of males and 47.4% of females, while depressive symptoms were found in 21.9% of males and 19.4% of females (Viner et al., 2022). The mental health challenges associated with remote education included anxiety, depression, loneliness, and perceived stress (Scott et al.; Quintiliani et al., 2022). Similarly, in the United States, a study of first-year college students revealed that anxiety prevalence increased from 18.1% to 25.3%, and depression from 21.5% to 31.7% within the first four months of the pandemic (Fruehwirth et al., 2021). In China, a study involving 7,143 college students showed a significant correlation between anxiety symptoms and disruptions in daily life and academics (Cao et al., 2020).

Poor academic performance in the context of distance education was found to be linked with concentration challenges, shorter attention spans, exam-related stress, COVID-19 contagion anxiety, and depressive symptoms (Giusti et al., 2021; Quintiliani et al., 2022). Conversely, students with a positive perception of distance learning, family support, and resilience skills were better able to manage educational challenges (Dändliker et al., 2021; Quintiliani et al., 2022).

A survey-based study in Malaysia assessed students’ demographics, academic challenges, and perceptions of remote education while screening for mental health issues using the DASS-21. It reported that 29.4% of university students experienced depression, 51.3% anxiety, and 56.5% stress, with older students showing lower prevalence rates (Moy & Ng, 2021). Another large-scale study using the parent version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) found that remote learning most negatively affected older children, as well as those from Black, Hispanic, or low socioeconomic backgrounds (Hawrilenko et al., 2021). Similarly, a survey of Mexican parents of children aged 4 to 15 highlighted behavioral issues, sleep disturbances, and increased screen time as key challenges of distance education (Reséndiz-Aparicio, 2021). Interestingly, the perceived threat of COVID-19 among students was correlated with their parents’ perceptions, and parents’ stress levels were positively associated with students’ stress (Garrote et al., 2021).

Despite the breadth of international research, there is a gap in large, multi-city studies in Saudi Arabia that explore the psychological impact of distance learning on children and adolescents. This research aims to bridge that gap by examining how remote education during the pandemic has affected students’ mental health and educational experiences across different demographics. The findings will provide valuable insights to inform mental health advocacy and guide the future direction of education, particularly in situations where distance learning becomes necessary.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

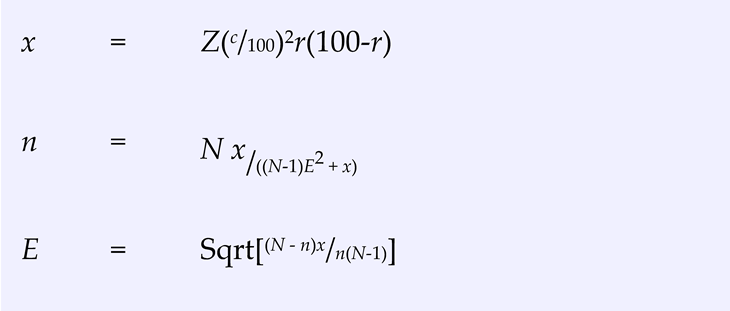

We employed a cross-sectional study design, distributing the questionnaire to parents via social media platforms, including WhatsApp. Data collection occurred between October and the end of November 2022. The sample size (n) was calculated to be 335 participants. This calculation was based on the estimated population of school-aged children in the Riyadh and Jeddah regions, which is approximately 2,000,000, according to the Saudi Ministry of Education’s statistics. The following formula was used to determine the appropriate sample size:

This formula ensures that the sample size is sufficient to represent the target population accurately, accounting for variability in the population and desired precision. Sample Size Calculator by Raosoft, Inc.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The study included parents of male and female children and adolescents aged 6 to 18 who attended governmental, national, or international schools, including both public and private institutions, within the Riyadh and Jeddah regions of Saudi Arabia.

Children and adolescents with pre-existing mental illnesses, such as anxiety or depression, before the pandemic lockdown were excluded to focus on the impact of distance learning on previously healthy individuals. Additionally, children with diagnosed neurodevelopment disorders—including Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), intellectual disability, and cerebral palsy—were excluded, as were those with chronic health conditions such as diabetes.

Validation and Data Collection

Parents with more than one child were allowed to complete the survey for each child. To identify multiple responses from the same household while maintaining anonymity, participants provided only the last four digits of their 10-digit family ID number. Data collected during the pilot phase were excluded from the final analysis. On average, it took 15 minutes for parents to complete the survey. Participants self-identified by responding to invitations sent through social media platforms.

Statistical Analysis

Data were summarized using means ± standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies with percentages for categorical variables. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Studies (SPSS) version 22 (IBM Corp., New York, NY, USA). Responses from the pilot survey were excluded from the final analysis.

Comparisons were made between children exhibiting ADHD symptoms (regardless of subtype) and those without any symptoms. The Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were used for categorical variables, while t-tests were applied for continuous variables. Multiple logistic regression was performed to evaluate the effect of significant variables on the outcomes. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The study involved 335 student participants, with a mean age of 4.9 years. Most families (72%) had three or more children, with 91.1% of parents married and 55% with both parents employed. Income varied, with 36.4% earning 10,000–20,000 SAR and 26.8% earning over 30,000 SAR. At the pandemic’s start, 48.7% of children were in early primary grades. Remote learning was prevalent, lasting one and a half years for 42.7% and two years for 41.2% of children, while 6.3% experienced schooling delays, primarily due to COVID-19 exposure concerns. Private schools were most common (40.9%), followed by government (36.7%) and international schools (22.4%). School changes affected 19.1% of students. Educational support came from family members in 28.7% of cases and domestic helpers in 9.3%. Almost all families (89.9%) had sufficient electronic devices for home education, with 52.2% rating distance learning as good. Chronic physical illnesses were reported in 4.5% of children, with ADHD and anxiety most frequently noted. A majority (93.7%) were not on medication, though 15% exhibited ADHD symptoms.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the students and their parents (N=334).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the students and their parents (N=334).

| Variable |

group |

Number |

% |

Variable |

group |

Number |

% |

The number of children in the home

N=280

|

1 |

54 |

19.3 |

What is the reason for the delay?

N=21

|

financial conditions |

1 |

4.8 |

| 2 |

78 |

27.9 |

social conditions |

1 |

4.8 |

| 3 |

71 |

25.4 |

Fear of exposure to the Corona virus, while having a health condition |

4 |

19 |

| 4 |

48 |

17.1 |

Fear of exposure to the Corona virus, and the child’s health condition is very good |

8 |

38.1 |

| 5 |

14 |

5 |

Another reason |

7 |

33.3 |

| >5 |

15 |

5.4 |

School type

|

government |

123 |

36.7 |

Parents’ marital status

N=280

|

married |

255 |

91.1 |

private |

137 |

40.9 |

| separated or divorced |

23 |

8.2 |

international |

75 |

22.4 |

| One of the parents is deceased |

2 |

0.7 |

Has the school changed due to the pandemic?

|

Yes |

64 |

19.1 |

| The age of the child at the beginning of the pandemic (Mean, SD) |

|

4.9 |

3.2 |

No |

270 |

80.6 |

Parents’ employment status

N=280

|

Mother and father are working |

154 |

55 |

Were others, such as grandfather, grandmother, or one of the siblings2, used to help the child attend the educational platform?

|

Yes |

96 |

28.7 |

| Only mother works |

16 |

5.7 |

No |

239 |

71.3 |

| Only father works |

94 |

33.6 |

2 Was a maid relied upon to help the child attend the educational platform?

|

Yes |

31 |

9.3 |

| Mother and father do not work |

16 |

5.7 |

No |

304 |

90.7 |

The total monthly income of the family

N=280

|

<10000 SR |

31 |

11.1 |

The presence of sufficient electronic devices for education at home

|

Yes |

301 |

89.9 |

| 10000-20000 SR |

102 |

36.4 |

No |

34 |

10.1 |

| 20000-30000 SR |

72 |

25.7 |

Assess the overall learning experience of distance learning for your respective child

|

very bad |

40 |

11.9 |

| >30000 SR |

75 |

26.8 |

bad |

55 |

16.4 |

The child’s classroom at the beginning of the pandemic - March 2020

N=335

|

1-3 primary |

163 |

48.7 |

acceptable |

65 |

19.4 |

| 4-6 primary |

92 |

27.5 |

good |

78 |

23.3 |

| intermediate |

57 |

17 |

very good |

55 |

16.4 |

| secondary |

23 |

6.9 |

excellent |

42 |

12.5 |

The child’s grade level when attendance or semi-attendance learning began again

N=335

|

1-3 primary |

120 |

35.8 |

Did your child suffer from chronic physical illnesses before the pandemic? |

No |

335 |

100 |

| 4-6 primary |

111 |

33.1 |

Has your child been diagnosed with chronic physical illnesses during the pandemic?

|

Yes |

15 |

4.5 |

| intermediate |

62 |

18.5 |

No |

320 |

95.5 |

| secondary |

42 |

12.5 |

What is the diagnosis?

|

ADHD |

5 |

38 |

The number of academic years the child studied remotely from March 2020 to March 2022

N=335

|

half a year |

21 |

6.3 |

Anxiety |

4 |

31 |

| one year |

33 |

9.9 |

get distracted |

2 |

15 |

| Year and a half |

143 |

42.7 |

psychosis |

1 |

8 |

| two years |

138 |

41.2 |

A combination of distractibility, hyperactivity, learning difficulties, and delay in social communication skills |

1 |

8 |

Is your child late for school because of Corona?

N=335 |

Yes |

21 |

6.3 |

Was this assessment done at a time when the child was on meds?

|

He takes medication |

10 |

3 |

| No |

314 |

93.7 |

He does not take medication |

314 |

93.7 |

If the answer is 1, how many years late?

N=21

|

half a year |

11 |

52.4 |

I’m not sure |

11 |

3.3 |

| one year |

5 |

23.8 |

|

|

|

|

| more than one year |

5 |

23.8 |

|

|

|

|

| |

No |

231 |

81.6 |

38 |

76 |

|

Were others, such as grandfather, grandmother, or one of the siblings2, used to help the child attend the educational platform?

|

Yes |

76 |

26.8 |

20 |

40 |

0.06

|

| No |

208 |

73.2 |

30 |

60 |

Was a maid relied upon to help the child attend the educational platform?

|

Yes |

22 |

7.7 |

9 |

18 |

0.032

|

| No |

262 |

92.3 |

41 |

82 |

The presence of sufficient electronic devices for education at home

|

Yes |

254 |

89.4 |

46 |

92 |

0.8

|

| No |

30 |

10.6 |

4 |

8 |

Assess the overall learning experience of distance learning for your respective child

|

very bad |

38 |

13.4 |

2 |

4 |

0.002

|

| bad |

51 |

18 |

4 |

8 |

| acceptable |

54 |

19 |

10 |

20 |

| good |

69 |

24.3 |

9 |

18 |

| very good |

44 |

15.5 |

11 |

22 |

| excellent |

28 |

9.9 |

14 |

28 |

| Has your child been diagnosed with chronic physical illnesses during the pandemic? |

Yes |

8 |

2.8 |

7 |

14 |

0.003

|

| No |

276 |

97.2 |

43 |

86 |

| Total symptom |

mean SD |

2.6 |

3.2 |

8.8 |

4.7 |

0.001 |

| Average performance |

mean SD |

0.131 |

0.211 |

0.523 |

0.291 |

0.001 |

Table 2 presents the findings from the Vanderbilt ADHD Diagnostic Rating Parent Scale. The results show that 5.4% of the children were classified as predominantly inattentive presentation, 1.8% as predominantly hyperactive/impulsive presentation, and 3.9% as combined ADHD presentation. Additionally, 7.2% of students were screened as potentially having oppositional defiant disorder, 1.5% for conduct disorder, and 6.6% for anxiety or depression.

Table 3 compares the demographic characteristics of students with and without ADHD symptoms, showing that 50 students in the sample exhibited ADHD symptoms. There were no significant differences in who completed the survey (whether father or mother), the number of children in the household, the child’s age, parents’ employment status, the length of remote learning, or school delays related to the pandemic. However, significant differences were observed in parental marital status. Specifically, 25.6% of children with ADHD symptoms came from separated or divorced families, compared to only 5.4% of children without ADHD symptoms. Furthermore, a higher proportion of children with ADHD were enrolled in grades 4–6 at the beginning of the pandemic.

Table 4 highlights the academic performance and other characteristics of students with and without ADHD symptoms. No significant differences were found regarding school type, school changes due to the pandemic, or access to electronic devices at home. However, significant differences were observed in the assistance children received for distance learning. Among children with ADHD symptoms, 40% received help from family members, such as grandparents or siblings, compared to 26.8% of children without ADHD symptoms. Additionally, 18% of children with ADHD relied on domestic helpers for assistance, compared to only 7.7% of children without ADHD (p = 0.032). Children with ADHD also reported a more positive overall distance learning experience compared to their non-ADHD peers. However, they had a higher likelihood of being diagnosed with chronic physical illnesses during the pandemic. In terms of academic outcomes, children with ADHD symptoms exhibited higher symptom scores and lower academic performance than those without ADHD symptoms.

The results of the multivariate logistic regression analysis, summarized in

Table 5, further explore factors associated with ADHD symptoms. The analysis found no significant link between age and ADHD symptoms. However, parental marital status was identified as a significant factor, with children from separated or divorced families being more likely to exhibit ADHD symptoms (Odds Ratio [OR] = 4.79, 95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 1.3–12.8, p = 0.002). Children with ADHD symptoms also reported a more positive learning experience during distance learning (OR = 5.473, 95% CI: 1.4–21.5, p < 0.05).

The analysis also examined whether a diagnosis of chronic physical illnesses or mental disorders during the pandemic was associated with ADHD symptoms. Although the odds ratio (OR = 2.182) was elevated, the association was not statistically significant (p = 0.31). No significant associations were found between ADHD symptoms and the assistance received from family members or domestic helpers with educational platforms. The analysis accounted for multiple children from the same household, identifying 69 children with one to three siblings, where parents completed multiple survey forms. However, the data did not reveal a significant association between having siblings from the same household and ADHD symptoms, and this factor was not further explored in the study.

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the behavioral and functional effects of distance learning, brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, on children and adolescents in two major Saudi Arabian cities. The findings revealed a significant correlation between parental marital status and ADHD symptoms, with children from separated or divorced families more than six times as likely to display ADHD symptoms compared to those with married parents. These results align with previous studies showing that parents of children with ADHD are more likely to experience marital discord and separation (Wymbs et al., 2008). However, it is unclear whether ADHD symptoms exacerbate marital conflict or result from it. Family stability is recognized as essential in promoting healthy child behavior and mental health (Johnston & Mash, 2001; Arfaie et al., 2013). Similarly, a study conducted in Italy found that children with married parents experienced fewer traumatic effects during the COVID-19 pandemic, emphasizing the role of family dynamics during stressful times (Spinelli et al., 2020).

The emotional challenges for parents and educators during remote learning have been widely documented. Research from Germany, for example, reported heightened levels of stress and anxiety among parents as they took on teaching responsibilities at home, with children requiring intensive supervision to remain engaged in online classes (Letzel et al., 2020). Similarly, a systematic review by Carrión-Martínez et al. (2021) found increased verbal aggression, family tension, and reduced well-being across students, parents, and teachers. The increased household stress identified in these studies aligns with our findings, suggesting that family environments significantly affect children’s ability to manage distance learning challenges.

Our study emphasizes the protective role of family support during remote education. Children who received help from siblings or relatives were less likely to exhibit ADHD symptoms than those who relied on domestic helpers. This finding aligns with prior research indicating that family involvement improves academic outcomes and reduces behavioral challenges (Sprang & Silman, 2013). A study from Canada showed that active parental engagement during distance learning improved children’s focus and emotional regulation, particularly for those with attention deficits (Shore et al., 2021). Similarly, Shahali et al. (2023) reported that children with learning difficulties performed better academically when provided with structured support and consistent family involvement during the pandemic.

Interestingly, our study found that children with ADHD reported a more positive distance learning experience compared to their non-ADHD peers. This contrasts with previous findings suggesting that students with ADHD typically struggle in remote education environments due to difficulties with attention, time management, and motivation (Tessarollo et al., 2021; He et al., 2021). However, our results align with emerging research indicating that certain children with ADHD benefit from the flexibility of remote learning (Bobo et al., 2020). The home environment may allow them to learn at their own pace, receive tailored support from parents, and avoid overstimulation common in traditional classrooms. Nevertheless, despite the reported positive experience, students with ADHD in our sample exhibited higher symptom severity and lower academic performance, consistent with other studies highlighting the academic challenges ADHD students face even in favorable environments (Tessarollo et al., 2021).

Our study also found that children with ADHD were five times more likely to be diagnosed with chronic physical illnesses during the pandemic compared to their non-ADHD peers. This aligns with research showing a higher prevalence of chronic health conditions, such as asthma, obesity, and sleep disorders, among individuals with ADHD (Pan & Bölte, 2020; Sciberras et al., 2014). These comorbid conditions may further complicate the academic and emotional challenges experienced by children with ADHD, underscoring the need for integrated healthcare and educational support.

Our findings emphasize the importance of family involvement and structured support during stressful events like the pandemic. As shown in studies from the U.S. and Europe, family cohesion and proactive engagement are critical in mitigating negative outcomes during distance learning (Thorell et al., 2021; Giusti et al., 2021). Moreover, children who receive consistent support from siblings or parents are more likely to develop resilience and emotional stability (Prime et al., 2020). Conversely, reliance on external caregivers, such as domestic helpers, may introduce inconsistencies in children’s routines, contributing to behavioral issues. This finding underscores the need for schools and mental health professionals to engage families actively in intervention strategies, especially when managing children with ADHD.

This study adds to a growing body of research showing that children with ADHD and other behavioral challenges face unique difficulties during remote learning. In particular, the positive distance learning experience reported by ADHD students in our study suggests that educational policies should explore flexible learning models that accommodate children’s individual needs. Future research could further investigate the specific features of remote learning environments—such as flexible schedules and personalized attention—that may benefit children with ADHD.

The strength of this study lies in its scope as the first large-scale, multi-city investigation in Saudi Arabia to examine the impact of distance learning on children’s mental health. By using the validated Arabic Vanderbilt ADHD Diagnostic Rating Scale, we ensure reliable measurement of behavioral and academic outcomes, contributing to a relatively under-researched area. Additionally, the study highlights the importance of family engagement in helping children manage stress during challenging times.

However, the study also has limitations. The reliance on parental reports may introduce bias, as parents of children with more severe symptoms may overestimate the negative impact (Horn effect). Moreover, the online survey format might exclude families with limited internet access, potentially skewing the sample toward higher-income households. Future studies should include teacher assessments and self-reports from older children to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the pandemic’s effects.

Despite these limitations, our findings offer valuable insights for mental health professionals and educators, emphasizing the need for family-centered interventions and flexible learning environments to support children with behavioral challenges. Further research should explore additional chronic health conditions and investigate how remote learning outcomes vary across different socioeconomic and cultural contexts.

Our study demonstrates that family stability and support are critical factors influencing children’s behavioral outcomes during distance learning. Children with ADHD benefited from increased family involvement, reporting a more positive learning experience despite higher symptom severity and academic challenges. These findings suggest that flexible learning models and family-centered interventions can improve outcomes for children with behavioral challenges. As the pandemic reshapes educational practices, mental health professionals and policymakers must collaborate to create adaptive learning environments that meet the needs of all students, particularly those with ADHD and other behavioral disorders.

Limitations and Prospective Directions

This study contributes to the limited research on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the well-being of school-aged children, but several limitations should be considered. The reliance on an online survey may have excluded families with limited technology access, potentially skewing the sample toward higher-income households. Although the survey was distributed through school platforms and snowball sampling could be attributed to technology gaps or parents being overwhelmed with caregiving responsibilities, limiting the statistical power and scope for follow-up.

While the diverse responses from families in major Saudi cities enhance the study’s generalizability, the reliance solely on parental reports introduces potential bias. This could lead to the Horn effect, where parents of children with severe symptoms might overestimate the negative impact. The absence of input from teachers or self-reports from older children further limits the study, especially since no validated self-report tools were available in the local context.

The use of predefined categories, with only a sixth “other” option, may have discouraged detailed reporting of less common conditions. To address these gaps, future research should broaden its scope to include multiple disabilities and allow for comparisons across different age groups.

Given the possibility of selection bias, the findings should be interpreted cautiously. Future studies should seek to integrate both parental and teacher perspectives, alongside self-reports from children, to gain a more holistic understanding of the pandemic’s impact. A more comprehensive approach would provide insights into the interaction between mental health, family dynamics, and educational outcomes across diverse socioeconomic contexts.

Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of King Saud University - College of Medicine under application number E-22-6867. Consent was obtained from parents at the beginning of the questionnaire, and parents were required to complete the survey to submit their responses. To ensure transparency, participants were informed about the study’s objectives on the survey’s introductory page, and consent was confirmed when participants clicked “yes” to proceed. All data were encrypted to protect participants’ confidentiality, and only the research team had access to the data for analysis.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed significantly to the study’s design, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation. They participated in drafting and revising the manuscript for critical intellectual content, approved the final version for publication, and agreed to take accountability for all aspects of the work.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the study was conducted without any commercial or financial relationships that could present a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Deanship of Scientific Research, King Saud University, for their support through the Vice Deanship of Scientific Research Chairs.

This study was funded by SABIC Psychological Health Research and Applications Chair, Department of Psychiatry, College of Medicine, Deanship of Post Graduate teaching, King Saud University.

List of Abbreviations

ADHD - Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

GAD 7 - Generalized Anxiety Disorder – 7 Items

COVID-19 - CoronaVirus Disease of 2019

DASS 21 - The Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale - 21 c

ID - Identifying Information

References

- Arfaie, A.; Mohammadi, A.; Sohrabi, R. Relationship Between Marital Conflict and Child Affective-behavioral Psychopathological Symptoms. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 84, 1776–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Fang, Z.; Hou, G.; Han, M.; Xu, X.; Dong, J.; Zheng, J. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 287, 112934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrión-Martínez, J.J.; Pinel-Martínez, C.; Pérez-Esteban, M.D.; Román-Sánchez, I.M. Family and School Relationship during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 11710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dändliker, L.; Brünecke, I.; Citterio, P.; Lochmatter, F.; Buchmann, M.; Grütter, J. Educational Concerns, Health Concerns and Mental Health During Early COVID-19 School Closures: The Role of Perceived Support by Teachers, Family, and Friends. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 733683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doom, J.R.; Deer, L.K.; Dieujuste, N.; Han, D.; Rivera, K.M.; Scott, S.R. Youth psychosocial resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2023, 53, 101656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fruehwirth, J.C.; Biswas, S.; Perreira, K.M. The Covid-19 pandemic and mental health of first-year college students: Examining the effect of Covid-19 stressors using longitudinal data. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0247999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrote, A.; Niederbacher, E.; Hofmann, J.; Rösti, I.; Neuenschwander, M.P. Teacher Expectations and Parental Stress During Emergency Distance Learning and Their Relationship to Students’ Perception. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 712447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laura, G.; Mammarella, S.; Salza, A.; Del Vecchio, S.; Ussorio, D.; Casacchia, M.; Roncone, R. Predictors of Academic Performance during the Covid-19 Outbreak: Impact of Distance Education on Mental Health, Social Cognition and Memory Abilities in an Italian University Student Sample. BMC Psychology 2021, 9, 142. [Google Scholar]

- Hawrilenko, M.; Kroshus, E.; Tandon, P.; Christakis, D. The Association Between School Closures and Child Mental Health During COVID-19. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2124092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Shuai, L.; Wang, Z.; Qiu, M.; Wilson, A.; Xia, W.; Cao, X.; Lu, L.; Zhang, J. Online Learning Performances of Children and Adolescents With Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Inq. J. Heal. Care Organ. Provision, Financing 2021, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hume, S.; Brown, S.R.; Mahtani, K.R. School closures during COVID-19: an overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Evidence-Based Med. 2023, 28, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, C.; Mash, E.J. Families of Children With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Review and Recommendations for Future Research. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 4, 183–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letzel, V.; Pozas, M.; Schneider, C. Energetic Students, Stressed Parents, and Nervous Teachers: A Comprehensive Exploration of Inclusive Homeschooling During the COVID-19 Crisis. Open Educ. Stud. 2020, 2, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moy, F.M.; Ng, Y.H. Perception towards E-learning and COVID-19 on the mental health status of university students in Malaysia. Sci. Prog. 2021, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, P.-Y.; Bölte, S. The association between ADHD and physical health: a co-twin control study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, M.; Jiang, J. COVID-19 and Social Distancing. Zeitschrift Fur Gesundheitswissenschaften = Journal of Public Health 2022, 30, 259–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livia, Q.; Sisto, A.; Vicinanza, F.; Curcio, G.; Tambone, V. Resilience and Psychological Impact on Italian University Students during COVID-19 Pandemic. Distance Learning and Health. Psychology, Health & Medicine 2022, 27, 69–80. [Google Scholar]

- Reséndiz-Aparicio, J.C. How the COVID-19 Contingency Affects Children. Boletin Medico Del Hospital Infantil de Mexico 2021, 78, 216–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahali, A.; HajHosseini, M.; Jahromi, R.G. COVID-19 and Parent-Child Interactions: Children’s Educational Opportunities and Parental Challenges During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Korean Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 34, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, M.; Lionetti, F.; Pastore, M.; Fasolo, M. Parents' Stress and Children's Psychological Problems in Families Facing the COVID-19 Outbreak in Italy. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessarollo, V.; Scarpellini, F.; Costantino, I.; Cartabia, M.; Canevini, M.P.; Bonati, M. Distance Learning in Children with and without ADHD: A Case-control Study during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Atten. Disord. 2021, 26, 902–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Saudi MOE Leading Efforts to Combat Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19).” n.d. Accessed November 20, 2023. https://planipolis.iiep.unesco.org/en/2020/saudi-moe-leading-efforts-combat-coronavirus-pandemic-covid-19-7148.

- Varnham, Jeremy. 2014. “Clinical Tools.” Saudi ADHD Society. جمعية إشراق. November 5, 2014. https://adhd.org.sa/en/adhd/resources/diagnosing-adhd/clinical-tools/.

- Viner, Russell, Simon Russell, Rosella Saulle, Helen Croker, Claire Stansfield, Jessica Packer, Dasha Nicholls, et al. 2022. “School Closures during Social Lockdown and Mental Health, Health Behaviors, and Well-Being among Children and Adolescents during the First COVID-19 Wave: A Systematic Review.” JAMA Pediatrics. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/article-abstract/2788069.

- Wolraich, M.L.; Lambert, W.; Doffing, M.A.; Bickman, L.; Simmons, T.; Worley, K. Psychometric Properties of the Vanderbilt ADHD Diagnostic Parent Rating Scale in a Referred Population. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2003, 28, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wymbs, B.T.; Pelham, W.E.; Molina, B.S.G.; Gnagy, E.M.; Wilson, T.K.; Greenhouse, J.B. Rate and predictors of divorce among parents of youths with ADHD. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 76, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Table 2.

Vanderbilt ADHD Diagnostic Rating Parent Scale NICHQ.

Table 2.

Vanderbilt ADHD Diagnostic Rating Parent Scale NICHQ.

| |

Number |

% |

| Predominantly Inattentive subtype |

18 |

5.4 |

| Predominantly Hyperactive/Impulsive subtype |

6 |

1.8 |

| ADHD Combined Inattention/Hyperactivity |

13 |

3.9 |

| Oppositional-Defiant Disorder Screen |

24 |

7.2 |

| Conduct Disorder Screen |

5 |

1.5 |

| Anxiety/Depression Screen |

22 |

6.6 |

Table 3.

Comparison between students with any ADHD symptom and without and other demographic characteristics.

Table 3.

Comparison between students with any ADHD symptom and without and other demographic characteristics.

| |

|

Is there any ADHA symptoms |

P value* |

| |

|

No N=284 |

Yes N=50 |

|

| |

|

Number |

% |

Number |

% |

|

The number of children in the home

|

1 |

45 |

18.8 |

9 |

23.1 |

0.81

|

| 2 |

68 |

28.3 |

9 |

23.1 |

| 3 |

60 |

25 |

11 |

28.2 |

| 4 |

40 |

16.7 |

8 |

20.5 |

| 5 |

13 |

5.4 |

1 |

2.6 |

| >5 |

14 |

5.8 |

1 |

2.6 |

| Age |

mean SD |

4.9 |

3.2 |

4.5 |

3 |

0.353 |

Parents’ marital status

|

married |

225 |

93.8 |

29 |

74.4 |

0.001

|

| separated or divorced |

13 |

5.4 |

10 |

25.6 |

| One of the parents is deceased |

2 |

0.8 |

0 |

0 |

What is the reason for the delay?

|

financial conditions |

1 |

5.6 |

0 |

0 |

0.701

|

| social conditions |

1 |

5.6 |

0 |

0 |

| Fear of exposure to the Coronavirus, while having a health condition that makes it vulnerable to complications |

4 |

22.2 |

0 |

0 |

| Fear of exposure to the Coronavirus, and the child’s health condition is very good |

7 |

38.9 |

1 |

33.3 |

| Another reason |

5 |

27.8 |

2 |

66.7 |

Table 4.

ADHD Combined Inattention/Hyperactivity of the student by their characteristics.

Table 4.

ADHD Combined Inattention/Hyperactivity of the student by their characteristics.

| |

|

Is there any ADHD symptoms |

P value* |

| |

|

No N=284 |

Yes N=50 |

|

| |

|

Number |

% |

Number |

% |

|

School type

|

government |

102 |

35.9 |

21 |

42 |

0.7

|

| private |

117 |

41.2 |

19 |

38 |

| international |

65 |

22.9 |

10 |

20 |

Has the school changed due to the pandemic?

|

Yes |

52 |

18.4 |

12 |

24 |

0.337

|

| No |

231 |

81.6 |

38 |

76 |

Were others, such as grandfather, grandmother, or one of the siblings2, used to help the child attend the educational platform?

|

Yes |

76 |

26.8 |

20 |

40 |

0.06

|

| No |

208 |

73.2 |

30 |

60 |

Was a maid relied upon to help the child attend the educational platform?

|

Yes |

22 |

7.7 |

9 |

18 |

0.032

|

| No |

262 |

92.3 |

41 |

82 |

The presence of sufficient electronic devices for education at home

|

Yes |

254 |

89.4 |

46 |

92 |

0.8

|

| No |

30 |

10.6 |

4 |

8 |

Assess the overall learning experience of distance learning for your respective child

|

very bad |

38 |

13.4 |

2 |

4 |

0.002

|

| bad |

51 |

18 |

4 |

8 |

| acceptable |

54 |

19 |

10 |

20 |

| good |

69 |

24.3 |

9 |

18 |

| very good |

44 |

15.5 |

11 |

22 |

| excellent |

28 |

9.9 |

14 |

28 |

| Has your child been diagnosed with chronic physical illnesses during the pandemic? |

Yes |

8 |

2.8 |

7 |

14 |

0.003

|

| No |

276 |

97.2 |

43 |

86 |

| Total symptom |

mean SD |

2.6 |

3.2 |

8.8 |

4.7 |

0.001 |

| Average performance |

mean SD |

0.131 |

0.211 |

0.523 |

0.291 |

0.001 |

Table 5.

Multiple logistic regression for the associated factors with ADHD Symptoms.

Table 5.

Multiple logistic regression for the associated factors with ADHD Symptoms.

| |

|

Odds ratio |

95% C.I.for OR |

P value |

| |

|

|

Lower |

Upper |

|

| Age |

|

1.008 |

0.895 |

1.137 |

0.89 |

Parents’ marital status

|

married** |

1 |

|

|

|

| separated or divorced |

4.79 |

1.787 |

12.836 |

0.002* |

Were others, such as grandfather, grandmother, or one of the siblings2, used to help the child attend the educational platform?

|

No** |

1 |

|

|

|

| Yes |

1.556 |

0.708 |

3.421 |

0.271 |

Was a maid relied upon to help the child attend the educational platform?

|

No** |

1 |

|

|

|

| Yes |

1.032 |

0.322 |

3.309 |

0.957 |

Has your child been diagnosed with chronic physical illnesses such as diabetes, mental disorders such as anxiety or depression, developmental disorders such as autism or ADHD or mental retardation during the pandemic?

|

No** |

1 |

|

|

|

| Yes |

2.182 |

0.479 |

9.937 |

0.313 |

Assess the overall learning experience of distance learning for your respective child

|

very bad/bad** |

1 |

|

|

|

| acceptable |

5.473 |

1.392 |

21.514 |

0.015* |

| good |

3.211 |

0.781 |

13.206 |

0.106 |

| very good/excellent |

6.902 |

1.831 |

26.012 |

0.004* |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).