Submitted:

06 November 2024

Posted:

06 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Principle and System

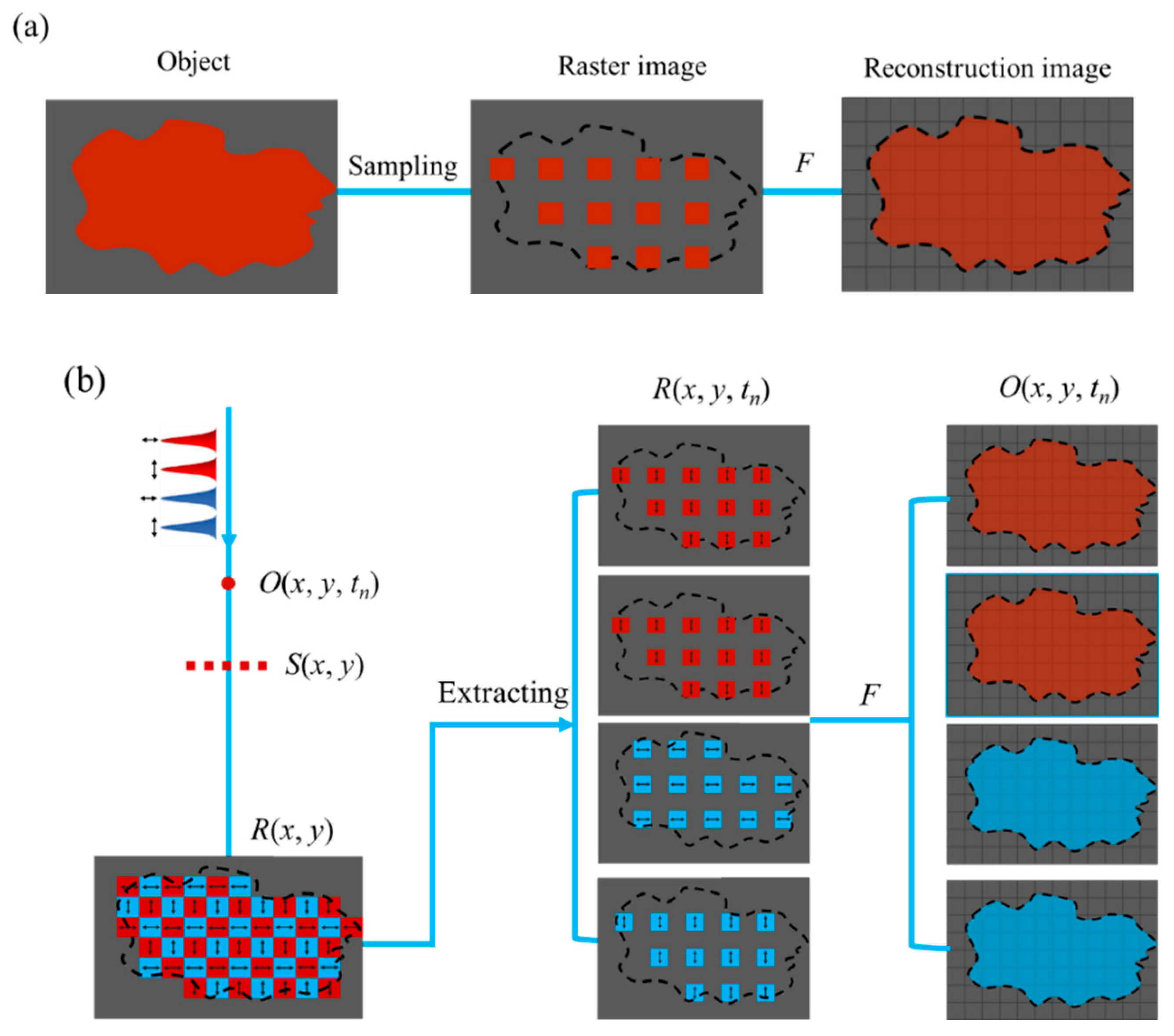

2.1. Principle of WP- URI

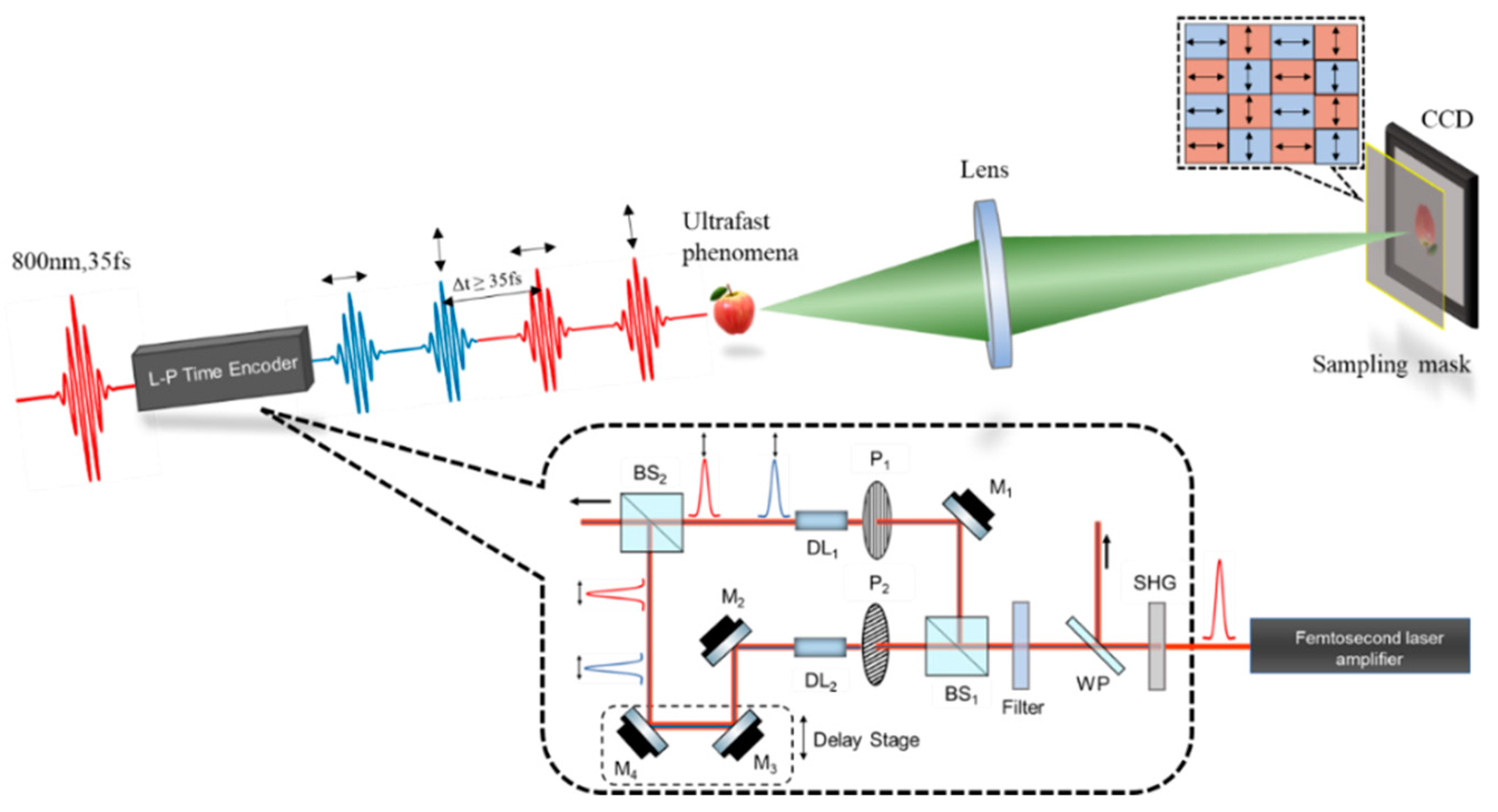

2.2. System of WP- URI

3. Results and Discussions

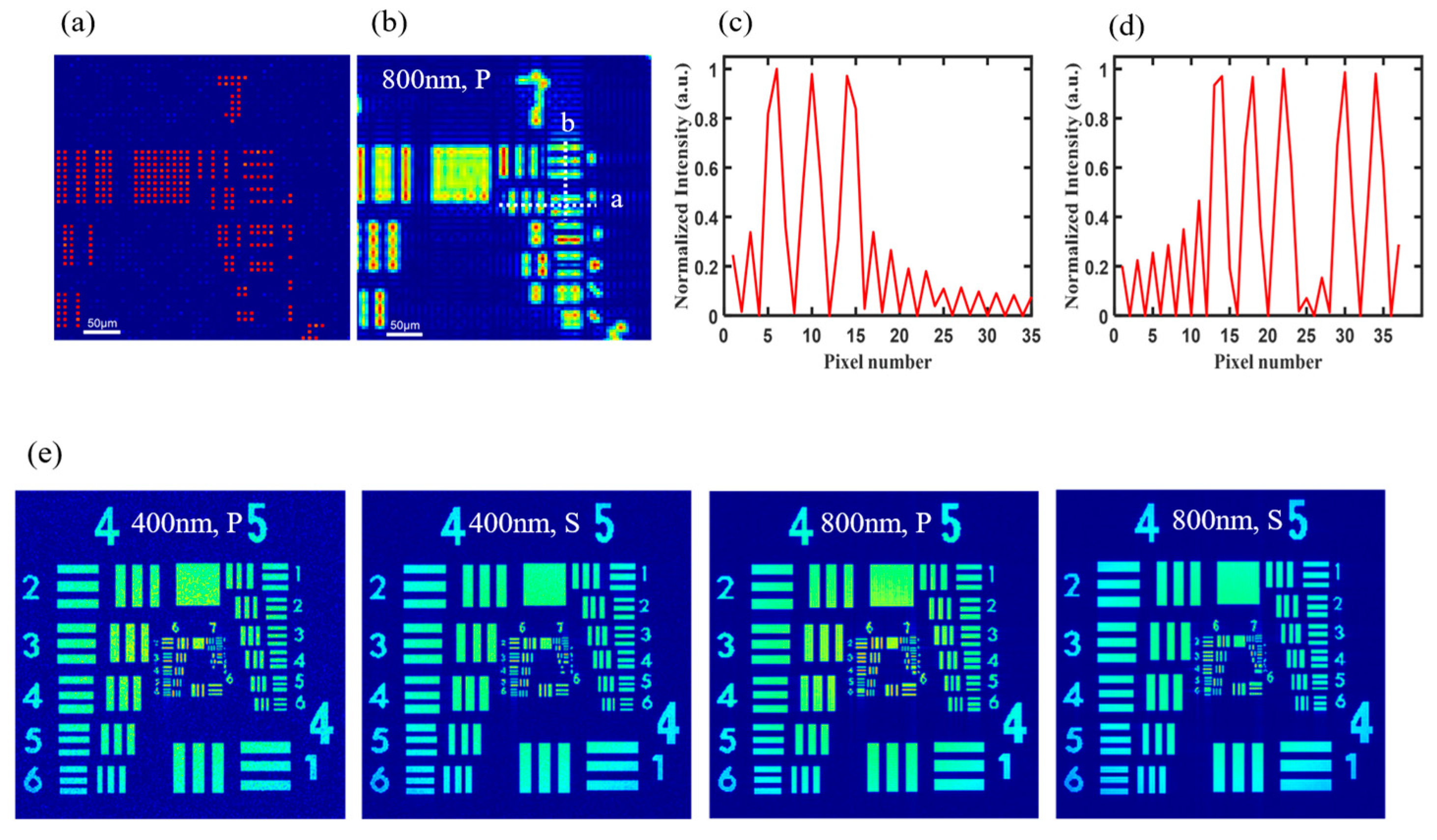

3.1. Characterization of the Spatial-Temporal Resolution

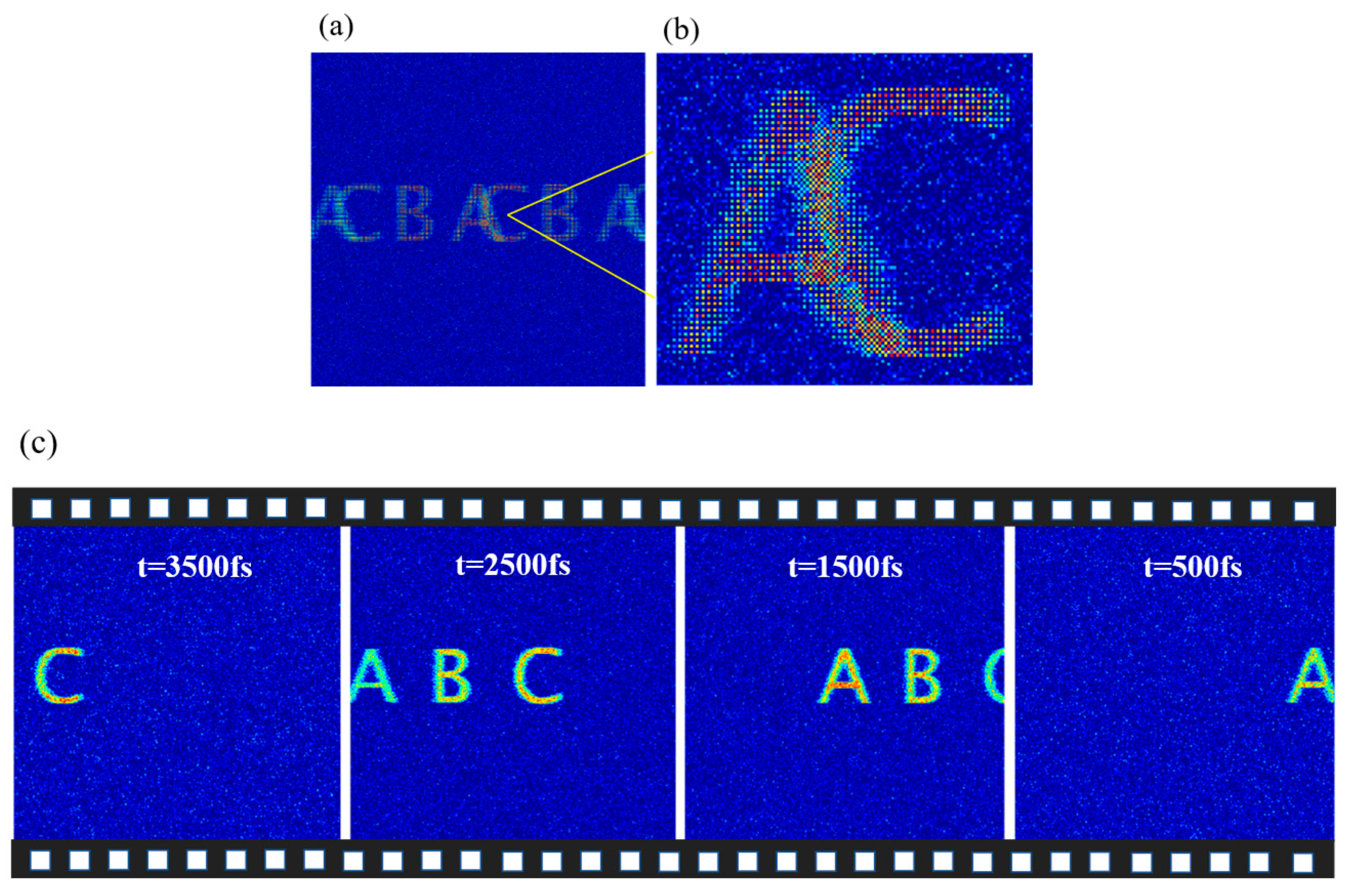

3.2. Single- Shot Imaging of an Object's Uniform Motion

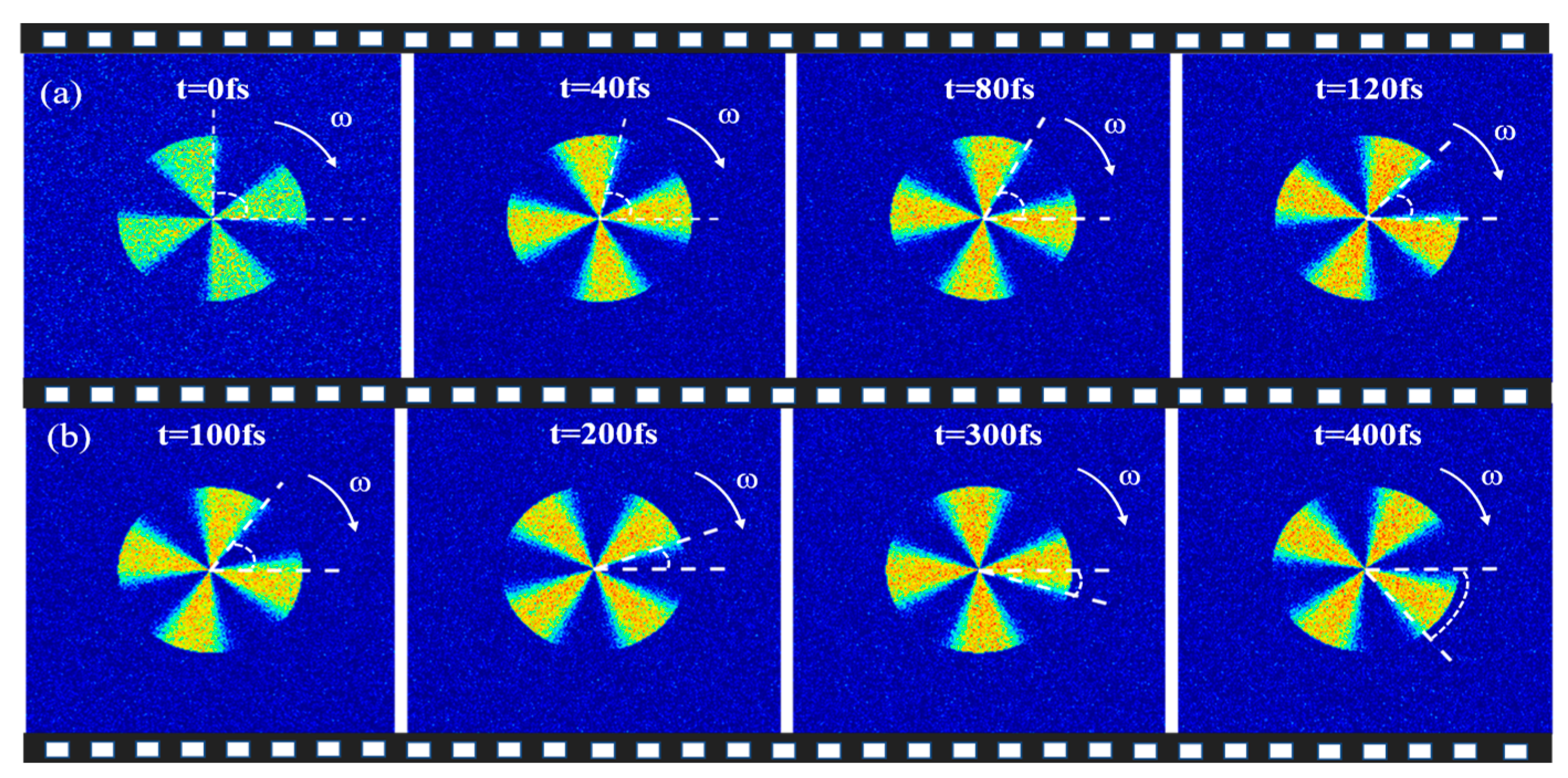

3.3. Single- Shot Imaging of the Uniform Rotation Object

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- T. Elsaesser and M. Woerner, "Ultrafast vibrational dynamics of hydrogen bonds in the condensed phase," Chem. Rev. 112(10), 4990–5009 (2012).

- M. Chergui and E. Collet, "Photoinduced structural dynamics of molecular systems mapped by time-resolved X-ray methods," Chem. Rev. 117(16), 11025–11065 (2017). [CrossRef]

- S. Wall, D. Wegkamp, L. Foglia, K. Appavoo, J. Nag, R. F. Haglund Jr., J. Stähler, and M. Wolf, "Ultrafast changes in lattice symmetry probed by coherent phonons," Nat. Commun. 3, 721 (2012). [CrossRef]

- K. E. Echternkamp, G. Herink, C. Ropers, and D. R. Solli, "Ramsey-type phase control of free-electron beams," Nat. Phys. 12(11), 1000–1004 (2016).

- M. Zhang, X. Li, R. Li, C. Ning, H. Wang, Y. Wang, M. Wang, M. Towrie, X. Yang, Z. He, and Z. Sun, "Ultrafast imaging of molecular dynamics using ultrafast low-frequency lasers, X-ray free electron lasers, and electron pulses," J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 13(7), 1668–1680 (2022).

- M. K. L. Man, A. Margiolakis, S. Deckoff-Jones, T. Harada, E. L. Wong, M. B. M. Krishna, J. Madéo, A.Winchester, S. Lei, R. Vajtai, P. M. Ajayan, and K. M. Dani, “Imaging the motion of electrons acrossemiconductor heterojunctions,” Nat. Nanotechnol. 12(1), 36–40 (2016).

- R. Huber, D. S. Chemla, A. Schmid, V. Saile, and V. Beushausen, "How many-particle interactions develop after ultrafast excitation of an electron-hole plasma," Nature 414(6860), 286–289 (2001).

- J. Herink, F. Kurtz, B. Jalali, D. R. Solli, and C. Ropers, "Real-time spectral interferometry probes the internal dynamics of femtosecond soliton molecules," Science 356(6333), 50–54 (2017). [CrossRef]

- M. Kaluza, M. Santala, J. Schreiber, G. D. Tsakiris, and K. J. Witte, "Time-sequence imaging of relativistic laser–plasma interactions using a novel two-color probe pulse," Appl. Phys. B 92(4), 475–479 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Na, J. Repp, R. Wallauer, and M. Weinelt, "Direct determination of mode-projected electron-phonon coupling in the time domain," Science 366(6470), 1231–1236 (2019).

- X. Zeng, S. Zheng, Y. Cai, X. Lin, J. Liang, X. Lu, J. Li, W. Xie, and S. Xu, "Review and prospect of single-shot ultrafast optical imaging by active detection," Ultrafast Sci. 3, 0020 (2023).

- S. Pathak, S. Bainbridge, R. Livingstone, S. Botchway, M. Towrie, A. W. Parker, I. P. Clark, and V. G. Stavros, "Tracking the ultraviolet-induced photochemistry of thiophenone during and after ultrafast ring opening," Nat. Chem. 12(9), 795–800 (2020).

- F. Krausz and M. I. Stockman, "Attosecond metrology: From electron capture to future signal processing," Nat. Photonics 8(3), 205–213 (2014). [CrossRef]

- L. Cattaneo, P. Zeller, N. Lucchini, A. Ludwig, M. Haag, M. Volkov, F. Lépine, H. J. Wörner, and U. Keller, "Attosecond coupled electron and nuclear dynamics in dissociative ionization of H₂," Nat. Phys. 14(7), 733–738 (2018).

- J. Duris, S. Li, W. Lorenzana, T. Driver, G. M. Andonian, E. G. Champenois, J. P. MacArthur, A. A. Lutman, Z. Zhang, P. Rosenberger, J. W. Aldrich, R. N. Coffee, G. Coslovich, F. J. Decker, J. M. Glownia, N. Hartmann, W. Helml, Z. Huang, J. Krzywinski, M. F. Lin, M. Nantel, A. Natan, J. T. O'Neal, N. Shivaram, P. Walter, T. Wang, T. J. A. Wolf, J. Z. Xu, M. F. Kling, P. H. Bucksbaum, M. Gühr, R. K. Li, and A. Marinelli, "Tunable isolated attosecond X-ray pulses with gigawatt peak power from a free-electron laser," Nat. Photonics 14(1), 30–36 (2020). [CrossRef]

- L. Gao, J. Liang, C. Li, and L. V. Wang, "Single-shot compressed ultrafast photography at one hundred billion frames per second," Nature 516(7529), 74–77 (2014). [CrossRef]

- J. Liang, C. Ma, L. Zhu, Y. Chen, and L. V. Wang, "Single-shot real-time video recording of a photonic Mach cone induced by a scattered light pulse," Sci. Adv. 3(1), e1601814 (2017). [CrossRef]

- J. Liang, L. Zhu, and L. V. Wang, "Single-shot real-time femtosecond imaging of temporal focusing," Light Sci. Appl. 7, 42 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Y. Lu, T. W. Wong, F. Chen, and L. V. Wang, "Compressed ultrafast spectral-temporal photography," Phys. Rev. Lett. 122(19), 193904 (2019). [CrossRef]

- D. Qi, E. B. Davis, L. Gao, J. Liang, and L. V. Wang, "Single-shot compressed ultrafast photography: a review," Adv. Photonics 2(1), 014003 (2020). [CrossRef]

- C. Yang, Y. Li, C. Ma, L. Zhu, Y. Li, Y. Liu, H. Jiang, and L. V. Wang, "Hyperspectrally compressed ultrafast photography," Phys. Rev. Lett. 124(2), 023902 (2020).

- H. Tang, T. Ma, X. Li, Y. Huang, J. Shen, Y. Zhao, P. Liu, J. Liang, M. C. Downer, and Z. Li, "Single-shot compressed optical field topography," Light Sci. Appl. 11, 244 (2022).

- P. Wang, J. Liang, and L. V. Wang, "Single-shot ultrafast imaging attaining 70 trillion frames per second," Nat. Commun. 11, 2091 (2020). [CrossRef]

- P. Wang and L. V. Wang, "Single-shot reconfigurable femtosecond imaging of ultrafast optical dynamics," Adv. Sci. 10(1), e2207222 (2023). [CrossRef]

- M. Tamamitsu, K. Nakagawa, R. Horisaki, A. Iwasaki, Y. Oishi, A. Tsukamoto, F. Kannari, I. Sakuma, and K. Goda, "Design for sequentially timed all-optical mapping photography with optimum temporal performance," Opt. Lett. 40(4), 633–636 (2015). [CrossRef]

- T. Suzuki, R. Hida, Y. Yamaguchi, K. Nakagawa, T. Saiki, and F. Kannari, "Single-shot 25-frame burst imaging of ultrafast phase transition of Ge₂Sb₂Te₅ with a sub-picosecond resolution," Appl. Phys. Express 10(9), 092502 (2017).

- T. Saiki, T. Hosobata, Y. Kono, M. Takeda, A. Ishijima, M. Tamamitsu, Y. Kitagawa, K. Goda, S. Y. Morita, S. Ozaki, K. Sakamoto, and F. Kannari, "Sequentially timed all-optical mapping photography boosted by a branched 4f system with a slicing mirror," Opt. Express 28(21), 31914–31922 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhu, X. Zeng, Y. Cai, X. Lu, Q. Zhu, L. Zeng, T. He, J. Li, Y. Yang, M. Zheng, G. Wang, and L. Xu, "All-optical high spatial-temporal resolution photography with raster principle at 2 trillion frames per second," Opt. Express 29(17), 27298–27308 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhu, X. Zeng, W. Ling, L. Zeng, Y. Zhao, J. Yang, and J. Li, "Design for ultrafast raster photography with a large amount of spatio-temporal information," Photonics 11(1), 24 (2023). [CrossRef]

- X. Yuan, Z. Li, J. Zhou, S. Liu, D. Wang, and C. Lei, "Hybrid-plane spectrum slicing for sequentially timed all-optical mapping photography," Opt. Lett. 47(18), 4822–4825 (2022). [CrossRef]

- H. Nemoto, T. Suzuki, and F. Kannari, "Extension of time window into nanoseconds in single-shot ultrafast burst imaging by spectrally sweeping pulses," Appl. Opt. 59(17), 5210–5215 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Ehn, J. Bood, Z. Li, E. Berrocal, M. Aldén, and E. Kristensson, "FRAME: Femtosecond videography for atomic and molecular dynamics," Light Sci. Appl. 6(4), e17045 (2017). [CrossRef]

- J. Moon, S. Yoon, Y.-S. Lim, and W. Choi, "Single-shot imaging of microscopic dynamic scenes at 5 THz frame rates by time and spatial frequency multiplexing," Opt. Express 28(4), 4463–4474 (2020). [CrossRef]

- X. K. Zeng, Y. Cai, X. W. Lu, Q. Zhu, L. Zeng, T. He, J. Li, Y. Yang, M. Zheng, and L. Xu, "High gain and high spatial resolution optical parametric amplification imaging under continuous-wave laser irradiation," Laser Phys. 24(11), 116002 (2014).

- X. K. Zeng, S. Q. Zheng, Y. Cai, Q. Lin, J. Liang, X. W. Lu, J. Li, W. Q. Xie, and S. Xu, "Generation and imaging of a tunable ultrafast intensity-rotating optical field with a cycle down to femtosecond region," High Power Laser Sci. Eng. 8, e3 (2020). [CrossRef]

- X. Zeng, S. Zheng, Y. Cai, Q. Lin, J. Liang, X. Lu, J. Li, W. Xie, and S. Xu, "High-spatial-resolution ultrafast framing imaging at 15 trillion frames per second by optical parametric amplification," Adv. Photonics 2(5), 056002 (2020). [CrossRef]

- J. Li, X. Zeng, Y. Cai, X. Lu, J. Liang, Y. Yang, L. Zeng, and Q. Zhu, "Advances in atomic time scale imaging with a fine intrinsic spatial resolution," Ultrafast Sci. 4, 0046 (2024). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).