Studying stressors and traumas phenomena across various disciplines, such as sociology, psychology, biology, and psychiatry, has led to a deeper understanding of their dynamics in each field. However, the division of these phenomena across different disciplines has prevented the development of an interdisciplinary conceptualization of the big picture and the identification of real-life, real-time traumatization dynamics. Stressors and traumas phenomena include chronic stressors such as chronic pain, and chronic discrimination which can fluctuate in severity and consist of a sequence of non-acute and acute personal, interpersonal, or collective stressors that may continue to accumulate and proliferate to other stressors and intersect.

New paradigms have emerged to fill the gaps that exist between different disciplines in the study of traumatic stress. Some of these paradigms have arisen from critiques of the psychiatric Criterion "A" of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Criterion "A" has been criticized on several grounds, including the fact that it is not based on a comprehensive taxonomy of traumatic stressors (Kira, 2001; Kira, 2022). It is essential to have a comprehensive taxonomy of stressors and traumatic events to measure their cumulative impact on health and mental health effectively. Critiques have pointed out that the current framework does not include certain events that can trigger symptoms of PTSD, such as extramarital affairs, unamicable divorce (e.g., Gold et al., 2005; Larsen & Pacella, 2016), or intergroup traumas such as torture, oppression, discrimination, racism and genocide (e.g., Carter et al., 2004; Holmes et al., 2016; Kira et al., 2021a; Williams et al., 2021).

We, along with others, argue that criterion "A" of (PTSD) which requires experiencing a traumatic event in the past for PTSD diagnosis, created unnecessary confusion based on the separation between chronic and acute stressors, and between what happened in the past and what is still going on or anticipated. We argue that both acute and chronic stressors can drive, under certain conditions, the subjective state of traumatization. The model we plan to test in the current study aims to clarify and examine the dynamics of stressors and trauma experienced by individuals and groups in real-life situations. For instance, in discrimination and racism, hate crimes can cause acute primary stressors (traumas) to the victims, but they can also lead to secondary traumas for the targeted group members. Moreover, these acute stressors often coexist with chronic stressors, such as microaggressions, which can fluctuate between acute and non-acute states. In addition, these chronic stressors can accumulate over time and interact with other life stressors, ultimately leading to a threshold-based effect.

Further, there is a conceptual overlap between the constructs of daily hassles (micro stressors) and chronic stressors (Hahn& Smith, 1999). Chronic stressors and daily hassles are particular stressors with unique contributions to psychological distress. One study supported that chronic stressors moderate the relationship between daily hassles and psychological distress (Serido et al., 2004). One of the critical direct determinants of mood was the concurrent daily stressors. Acute life events and chronic stressors indirectly affect mood through concurrent daily hassles (Eckenrode, 1984). A longitudinal study found that the impact of episodic stressors (acute stressors) is accentuated amid chronic stressors and diminished in their absence (Marin et al., 2007). Another study found that daily exposure to stressors has a negative impact on daily health. This is mediated or moderated by cumulative stress across multiple life domains and over time (Haight et al., 2023).Most studies on the effects of hassles and chronic stressors were focused on their effects on health and the biological dynamics of stress response. There is an early attempt to bridge this divide between the trauma-focused approach and the psychosocial daily stressors frameworks (e.g., Miller & Rasmussen, 2010).

Research has suggested that chronic stressors, including both acute and non-acute, can be just as stressful, or even more so, than single acute stressors. (e.g., Gold et al., 2005; Katz et al., 1981). The recurrence of chronic stressors can have a “cumulative” impact. The prolonged sequence of repeated acute (and non-acute) stressors can potentially yield more complex post-trauma (or complex peri-trauma) symptoms(c.f., e.g., Herman, 1992, see also: Briere et al., 2016; Cloitre et al., 2009, Courtois, 2008; Courtois & Ford, 2012). It is crucial to recognize that events that may cause traumatization can be either chronic or acute and can occur due to an accumulation and proliferation of stressors. In real life, these events are often continuous and interrelated and can be personal, interpersonal, or intergroup.

The continuous traumatic stressors (CTS) paradigm has emerged in various fields of study, such as psychosocial studies of community and intergroup violence (Eagle & Kaminer, 2013; Kira et al., 2008, 2013) and bio-psychological studies of severe burns continuous traumatic impact (Gilboa et al., 1994). This paradigm presents a challenge to the current focus on single past stressors by highlighting the impact of continuous stressors. There is a need to integrate these various fields of CTS studies with chronic stressors and to emphasize that continuous and chronic stressors may lead to continuous stress, which requires further clarification.

Further. research emphasized that the earliest continuous stressors (chronic and acute), such as childhood adversities and discrimination, can proliferate to other subsequent adult traumas through various mechanisms and follow various trajectories across the developmental life stages (Kira et al., 2018; Kira, 2021a; Kira et al., 2021c; Pearlin et al., 2005). Research on adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) has generated a rich knowledge about the ACE's significant contribution to the etiology of disorders and diseases and factors leading to early death (e.g., Bellis et al., 2014; Fletti et al., 2019).

The recent COVID-19 pandemic, with its multiple individual and collective stressors that continued for over two years, further questioned such psychiatric assumptions about stressors and traumas (Horesh & Brown, 2020; Kira et al., 2021f). We learned firsthand from COVID-19 how trauma can be continuous, multi-dimensional (fear of deadly infection, loss of job, lockdown, and loss of loved ones due to COVID), and have a prolonged time scale (two or three years). We learned how discrimination and intersected discrimination as a sequence of life-long chronic and intersected acute stressors kill minorities and victims of discrimination (e.g., Kira et al., 2021d; Tai et al., 2021). The realities of COVID-19 underscored the social determinants of physical, mental, and cognitive health. As the sociological and psycho-behavioral theories emphasize, the social structure and its dynamics are significant drivers of health and related biological, neurological, genetic, epigenetic, emotional, and cognitive processes (e.g., Landecker & Panofsky, 2013). Intersected discrimination ( and cumulative and proliferation dynamics) has been found to impact mental health and executive functions negatively (Kira et al., 2020b; Kira et al., 2021b; Kira et al., 2022a; Kira et al., 2022c) and IQ (Kira et al., 2012 ) in addition to killing people by increased vulnerabilities and suicide(e.g., LeBouthillier et al., 2015).

Two factors may lead to feelings of traumatization in the chronic stress model. The first factor is related to the characteristics and dynamics of the stressor, while the second factor is related to the person's internal dynamics. We suggest that at least three dynamic factors may increase the intensity (acuteness) of trauma/stressors and the potential for traumatization. Firstly, the longer the cascading stressors last, the more severe the potential subjective traumatization may be. Secondly, the more stress generation (e.g., Liu et al., 2024; Rnic et al., 2023 ) and trauma proliferation (e.g., Arpawong et al., 2022; Kira et al., 2018 ) occur, the more severe the potential subjective traumatization may be. Thirdly, the denser the stressors network with different concurrent dimensions of various acute and chronic stressors, the more severe the potential subjective traumatization may be. Examples of trauma network density are intersectionality () and poly-victimization ().

The factors related to the person's internal dynamics contributing to potentially increased subjective traumatization are based internally on at least two contributing factors. First, how much the stressor has an actual or perceived existential threat to the individual's personal, social, status, and physical identities as the person consciously or unconsciously perceives and processes (.e.g., Sullivan et al., 2012). That means what makes an event or a sequence of events traumatic is the subjective experience (the perception and appraisal of its potential existential threats to one or more of the person's nested identities), regardless of whether these events are chronic or acute or a combination of both (c.f., Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). The second significant internal traumatization dynamic is the individual's stress tolerance and sensitivity threshold (which may be translated to resilience), which may erode with the intensity of repeated exposure. Exposure to continuous stressors may erode the person's resources, bridging to the break-up point, reducing the threshold stress tolerance, and causing severe traumatization eruption with adverse consequences (e.g., Monroe & Simons, 1991; Kira et al., 2020a). Finally, we argue that the severity of a stressor (chronic or acute) is measured by its objective impact on cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and social functioning that can be empirically validated. To empirically test stressors' differential severity in the current study, we pay attention to their impact on complex PTSD (CPTSD) and executive functions. We have to differentiate between the stressors (chronic or acute) and the reactions to them. Rape, COVID-19, torture, discriminations are traumatic regardless of whether symptoms develop.

The conceptualization of chronic stressors is intimately related to continuous traumatic stressors (CTS), complex trauma (Courtois & Ford, 2012), and type III trauma paradigms which are parts of the development-based framework (DBTF) (Kira, 2001; Kira et al. 2008; Kira, 2022; Kira, 2021). The CTS paradigm studied different forms of community violence, intergroup conflict, discrimination, and burn impact without an overarching framework. Type III trauma (in DBTF, the most severe type compared to types one and II) with its five sub-types, provided an earlier plausible framework that organizes these kinds of CTS. The Type III trauma model received initial empirical evidence (Kira et al., 2013; Kira, 2021b; Kira et al., 2022b). The model includes different types of continuous traumatic stressors. Table 1 summarizes the model structure.

Table 1.

Trauma types according to severity gradients and their sources in the literature.

Table 1.

Trauma types according to severity gradients and their sources in the literature.

Type I trauma

Single acute past stressor |

Type II Trauma

Sequence of related past acute stressors |

Type III trauma: Continuous and ongoing stressors/ traumas may have a prolonged time scale and high density with potentially more severe impact (Kira, 2001; Kira et al., 2013a; Kira, 2021a, b; Terr, 1995). Type III traumas can potentially proliferate into other traumas (e.g., Kira et al., 2018). They have five subtypes or variants with different prolonged time scales, medium to high trauma network density, and varying severity: They may intersect and amplify each other's total impact. Type III traumas intersect and may lead to each other or other trauma types. For example, intergroup conflict can lead to discrimination and vice versa. Prolonged childhood adversities and discrimination can proliferate into other traumas through different mechanisms (e.g., Green et al., 2010; Kira et al., 2018; Kira et al., 2021c |

|

Type III trauma-A: includes various discriminations that may intersect (making their network density high). Discrimination may continue through the life- course and thus have the most protracted time scale (e.g., Carter et al., 2004; Kira et al., 2013a; Kira et al., 2015b; Potluri & Patel, 2021). |

|

Type III trauma-B: includes exposure to prolonged childhood adversities, such as children's experience in foster care. Childhood poly-victimization indicates a high density of such trauma (e.g., Finkelhor et al., 2011; Ford & Delker, 2020; Hailes et al., 2019; Landers et al., 2021). |

|

Type III trauma-C: includes ongoing intergroup conflicts like the Palestinian-Israeli conflict and prolonged civil wars like the Syrian civil war. (e.g., Green et al.,2018; Pat-Horenczyk et al., 2013; Pat-Horenczyk & Schiff, 2019; Stein et al., 2018). |

|

Type III trauma-D: includes exposure to chronic community violence (e.g., Straker, 1987). |

|

Type III trauma-E: type includes chronic, life-threatening medical conditions such as HIV (Quinn et al.,2020) and COVID-19 (e.g., Alpay et al., 2021a; Kira et al., 2021g; Kira, 2021a; Kira, 2021b; Kira et al., 2021f; Lahav, 2020; severe burns, Gilboa et al., 1994) |

All subtypes of Type III traumas are potentially severe with different intensities and time scales. The differential severity of Type III trauma five variants needs to be empirically determined.

Extensive psychological research has been conducted on Western cultures that have distinct, mainly individualistic, trauma profiles. It is imperative to validate the Type III trauma model on non-Western cultures that are more collectivistic and may have different trauma profiles. The model of Type III trauma and its five subtypes have been empirically tested and found to be valid in highly traumatized populations of Syrian internally displaced and tortured survivors (Kira, 2021b; Kira et al., 2022b). There is a need to test the model in less traumatized populations. Kuwaiti citizens are generally one of the affluent populations’ non-westerns (e.g., Alzarban, 2018). Furthermore, including chronic stressors in the model has never been tested.

The current study aims to test the model of the differential impact of chronic and acute stressors, the validity of the assumptions of trauma types I, II, and III, and the relative impact of the five variants of Type III trauma (continuous traumatic stressors): Discrimination, early childhood adversities, intergroup conflict, community violence, chronic life-threatening conditions. This model testing may help clarify, validate, expand, or modify the DBTF and CTS assumptions. It also may help devise future more effective chronic and acute stressors-focused or Type III trauma-focused interventions.

Hypotheses

Hypothesis 1 : Chronic stressors have a higher impact on mental health and cognitive functions than single acute stressors.

Hypothesis 2: Type III trauma (the continuous traumatic stressors) had a higher impact on mental health and cognitive function than trauma types I and II.

Hypothesis 3 : Type III-a (intersected discrimination) and Type III-b (childhood adversities) had a higher proliferation potential and higher impact on mental health and cognitive functions than Type III-c (intergroup conflict), Type III-d traumas (community violence), and type III-e trauma (chronic life-threatening conditions).

Methods

Participants included 490 Kuwaiti citizens. Their ages ranged from 18 to 60 (Mean=24.97, SD=9.10), and 66.3% were females and 33.7% were males. For marital status, 24.1% were married, 72.4% were single, 2.7% were divorced, and 0.8 were widows. For socioeconomic status (SES), 2.9% indicated that they belong to low SES, 80% to middle SES, and 17.1% reported belonging to high SES. For religion, 99.6% were Muslims, and 0.4% reported other religions. For education, 1.2% has good reading and writing abilities, 9.2% have an intermediate level of education, 83.5% have a college or university education, and 6.41% have graduate degrees.

Procedures: The data collection for the study continued from October 2021 to January 2022. The participants were recruited from various online sources and word of mouth. The survey used a web-based self-report survey (Google Forms®). The research team of four graduate students under the supervision of the primary research leader used the snowball recruiting method through social media (e.g., Facebook) and e-mail lists in Kuwait. The initial 150 participants were asked to complete a set of measures in the survey and send the link after done to all their adult friends and relatives and ask them to do the same after done. Before filling out the survey, information was given about the study's purpose. The participant had to sign the online informed consent to participate. Each person took between 25 -30 minutes to complete the questionnaire.

Measures

Cumulative stressors and traumas scale (CTS-S-36 items; Kira et al., 2008): It is constructed to measure the stressors and traumas that were identified by the development-based trauma framework (DBTF) (e.g., Kira, 2001; Kira, 2019; Kira, 2021a; Kira, 2021b). The scale measures six kinds of traumas and includes three items that measure chronic stressors and hassles. An example of the items that measure chronic stressors is "I experienced seemingly small but recurrent or unremitting hassles or chronic stressors that put me on the edge of losing control." The six trauma types include attachment traumas (e.g., abandonment by parents), personal identity trauma (e.g., early childhood traumas such as child neglect and abuse), collective identity traumas (e.g., discrimination and oppression), achievement trauma (e.g., failed business, fired, and drop out of school) and survival trauma (e.g., getting involved in combat, car accidents, and natural disasters). They also include secondary trauma (i.e., traumas suffered by significant others and those who identified with them). Further, the measure includes three sub-scales that represent degrees of trauma intensity: Type 1 traumas (6 items that represent single events, least intensity), type II traumas (9 items that represent a sequence of events that continued in the past for a relatively short time and stopped, moderate intensity), and Type III traumas (9 items, high intensity) that represent events that were or are continuous or have prolonged or indefinite time scale). Type III trauma, in this framework, has five subtypes (detailed earlier). There is empirical evidence of the severity continuum of the three trauma types (Kira, 2021b). Participants were asked if they experienced the event on a 5-point Likert-type scale (0 = never; 4 = many times). In the current data, the type I, II, and III trauma subscales had an alpha of .85,.91, and .93. CTS occurrence's alpha was .93.

International Trauma Questionnaire ITQ (Cloitre et al., 2018).The ITQ was developed to assess and diagnose PTSD and complex PTSD (CPTSD). ITQ includes 18 items that measure re-experiencing, avoidance, sense of current threat, and disturbances in the Self-Organization (DSO) cluster. DSOs that characterize CPTSD include (1) affective dysregulation, (2) negative self-concept, and (3) disturbances in relationships and level of functioning. The measure includes two items that ask the participant to identify the referred trauama/s. ITQ uses diagnostic algorithms to reach the probable diagnosis of either PTSD or CPTSD. Additionally, it provides dimensional scoring for PTSD and CPTSD symptom severity. In current Data, PTSD has an α of .75, and CPTD has an α of .85.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., 2006). It is a 7-item scale that measures generalized anxiety. The measure has a cut-off point of 15, translating to severe anxiety. The measure has a specificity of 82% and a sensitivity of 89%. High scores on the scale were found to be highly correlated with functional impairment in multiple domains (Spitzer et al., 2006). Its Arabic version was found to have robust psychometrics (Sawaya et al., 2016). The scale has an alpha of .75 in current data.

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., 2001) The scale consists of 9 items that measure depression severity. The cut-off score spans from 15-19 meaning moderate to severe depression, while a score of 20 and above means severe depression. A study found that the Arabic version of the scale was robust (Sawaya et al., 2016). In the current study, the scale had an Alpha of .77.

The Adult Executive Functioning Inventory (ADEXI; Holst & Thorell, 2018). The scale had been used to assess executive functioning deficits in adults. It is a 14-item that assesses working memory (9 items), and inhibition deficits (5 items). The measure was found to adequately discriminate between adults with ADHD and controls (Holst & Thorell, 2018). The measure was found to have adequate psychometric properties in Arabic populations (Kira et al., 2020b). In the present study, it had an alpha of .85 for the total scale.80 for the working memory deficits, and .77 for the inhibition deficits.

Statistical analysis: To determine the sample size required to detect a medium effect size at power = .80 for α = .05 for the number of variables in the study design, we used Cohen's (1992, p.158) criteria. We conducted data analysis using IBM-SPSS and AMOS 27. There were no missing data. The survey was designed to give the participant the option to answer the question or not proceed to the next question and opt out of the study. We measured the correlation between trauma I, II, and III, trauma type III five variants, chronic stressors, and mental health and executive function. We followed Cohn's recommendations for evaluating effect sizes in correlational research. According to Cohn, 1988, an effect size of .10 (or less) can be considered small; an effect size of .30 can be considered medium size, while an effect size of .50 or more can be considered large.

Further, we tested two SEM models. In the first model, trauma types I, II, and III and the chronic stressors were independent variables, with two latent variables as the outcome: mental health latent variable predicted by CPTSD, PTSD, depression, and anxiety variables, and executive function latent variable as predicted by working memory and inhibition deficits. In the second model, the five variants of type III traumas were the independent variables and the same two latent variables: mental health and executive function as in the first model. We measured direct, indirect, and total effects as standardized regression coefficients. The criteria for good model fit were a comparative fit index (CFI) values > 0.90, and root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) values < 0.08 (Byrne, 2012). We performed bootstrap with 10,000 bootstrap samples to measure the significance of direct, indirect, and total effects and 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (95% CI) for variables.

Results

Descriptive results: Many of the participants in the study identified COVID-19 as their central trauma. The study found that the cumulative trauma occurrences were moderate, with an average of 5.95 and a standard deviation of 5.41, based on 36 trauma and stressor events. The frequency of these events was also moderate, with an average of 11.46 and a standard deviation of 12.99. 6.3% of the participants reported no traumas, while 63.3% reported experiencing four or more traumas.30.4% of the participants reported that they had been infected with COVID-19, and 16.3% scored above the mid-point level of COVID-19 stressors. The study found that 6.3% of the participants met the criteria for probable Complex PTSD (using ICD-11 criteria), while 10% met the criteria for probable PTSD diagnosis. The study also found that 8.2% of the participants scored at the highest level of anxiety, with a score at the cut-off of 15+. For depression, 14.3% of them scored on or above the cut-off score for moderate to severe depression, while 5.1% of them scored on the cut-off score for acute depression.

Correlations results: Trauma types III, III-a, and III-b have a small to medium correlation with working memory deficits (WMD), while trauma types one and II have only a small correlation with WMD. The highest correlation for WMD is found between chronic stressors. Type III, III-a, III-b, type III-c, and type II traumas have small to medium correlations with inhibition deficits (ID). The highest correlation for ID is with chronic stressors. Table 1-S in the supplemental materials provides detailed results.

Type III traumas had a medium to large association size with CPTSD (.45, p=<. 001), PTSD (.38, p=<. 001), and depression (.32, p=<. 001), and small to medium association size with anxiety (.28, p=<. 001), WMD (.18, p=<. 001), and ID (.20, p=<. 001). Type II trauma had a medium correlation with CPTSD (.35, p=<. 001), small to medium size correlation with PTSD (.29, p=<. 001), depression (.29, p=<. 001), and anxiety(.26, p=<. 001) and ID (.15), p=<. 001. It has a small size correlation with WMD (.09, p=<. 05). Type I trauma had a small to medium size correlation with CPTSD (.23, p=<. 001), PTSD (.24, p=<. 001), depression (.16, p=<. 001 ) and anxiety (.16, p=<. 001), and small size association with WHD (.09, p=<. 05) and ID (.13, p=<. 001). Chronic stressors had their highest association with type III trauma (.60, p=<.001). Their associations with CPTSD and PTSD were comparable in their effect sizes to their association with type III trauma. However, chronic stressors had a higher association with depression (.42, p=<. 001), anxiety (.39, p=<. 001), WMD (.23, p=<. 001), and ID (.27, p=<. 001), than all trauma types. Table (2-S) details these results.

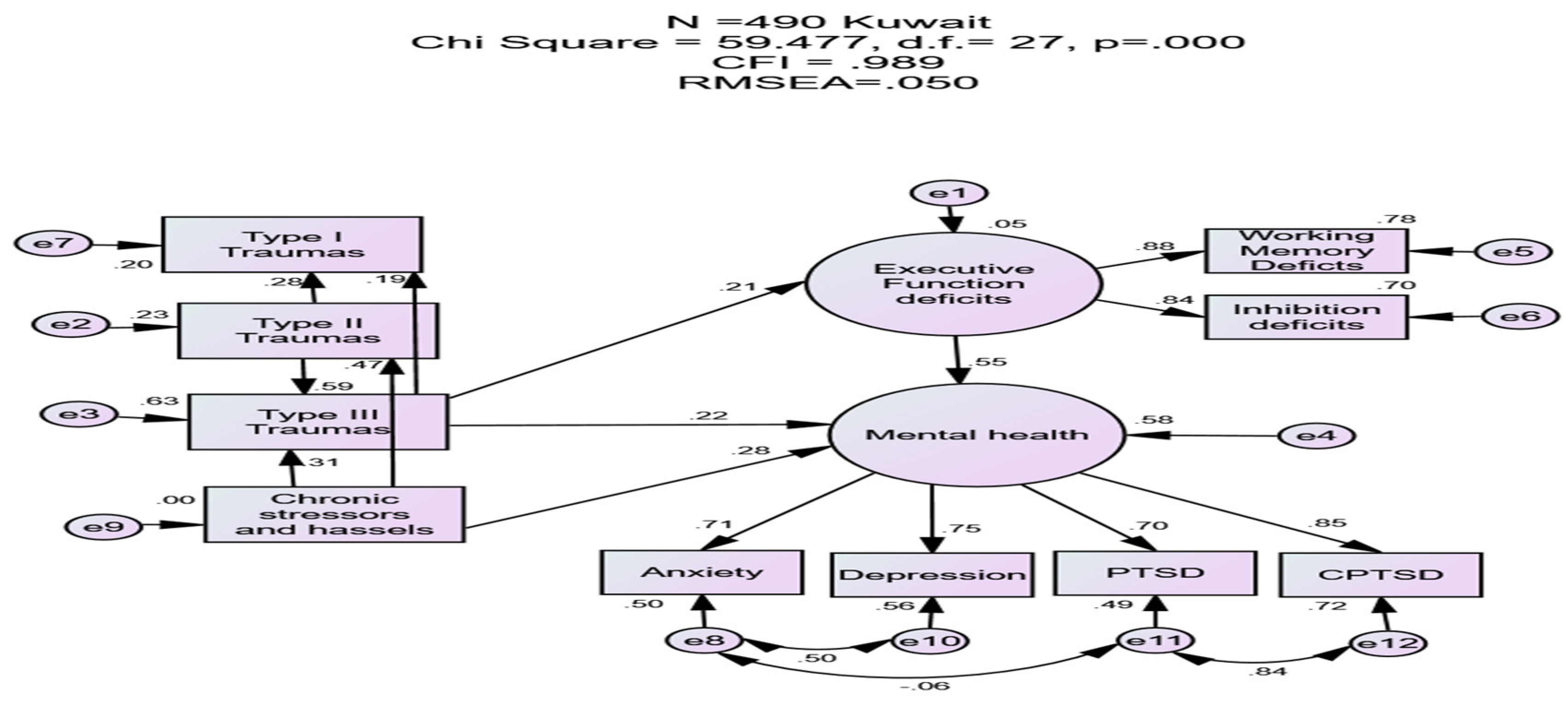

SEM results: The first model fit well with the data (Chi Square=.59.477, d.f.=27, p=.000, CFI=.989, RMSEA=.050). WMD accounted for the highest variance in the model (R=.779), followed by CPTSD (R=.720). In the model, chronic stressors had a direct moderate to high effect size (.48, p<.01) on type II trauma. It directly and indirectly affected type III trauma and mental health. Its total effects on mental health were moderate to high (.48, p<.01). It had a large total effect on type III trauma (.60, p<.01). Its direct effects on type III trauma accounted for 53% of its total effects. Its direct effects on mental health accounted for 58% of its total effects. It had an indirect low to medium effect size on type I trauma (single events) (.25, p<.01) and medium to high effect size on CPTSD (40, p<.02), depression (.35, p<.01), anxiety (.33, p<.01), and PTSD (.33, p<.03). It had small but significant indirect effects on WMD and ID.

Type II trauma (e.g., sexual and physical abuse) had large direct effects on type III trauma (.60, p<.01). It had direct and indirect effects on type I trauma (single event). Its total effects on type I trauma were medium to high (.41, p<.01). Its direct effects on type I trauma accounted for 71% of its total effects. It had small to medium-sized indirect effects on CPTSD, depression, anxiety, PTSD, WMD, and ID.

Type III trauma (continuous traumatic stressors) had small to medium direct effects on executive function (.22, p<.01), and type I trauma (single event trauma,.19, p<.02). It had direct and indirect effects on mental health. Its total effects on mental health were medium (.34, p<.01). Its direct effects accounted for 65% of its total effects. It had small to medium size effects on CPTSD (.28, p<.01), depression (.25, p<.01), anxiety (.24, p<.001), PTSD (.23, p<.01), WMD (.19, p<.01), and ID (.18, p<.01).

Executive function deficits had a large direct effect size on mental health (.55, p<.01). It had a medium to large indirect effect size on CPTSD (.45, p<.01), depression (.41, p<.01), anxiety (.39, p<.01), and PTSD (.38, p<.01). All mental health and executive function variables loaded significantly on their respective latent variables. Executive function deficits seem to have the most considerable effects on mental health compared to trauma variables. Table (2) details the direct, indirect, and total effects and their 95% confidence interval in the model. Figure (1) depicts the variables' standardized direct effects.

Table 2.

The standardized direct, indirect, and total effects and their 95% confidence intervals of the impact of chronic stressors and trauma types II and III on other traumas (proliferation) and mental health and executive functions.

Figure 1.

SEM diagram for the standardized direct effects of trauma types I, II, and III, and chronic non-acute stressors on each other (proliferation and stress generation), and on mental health and executive functions.

Figure 1.

SEM diagram for the standardized direct effects of trauma types I, II, and III, and chronic non-acute stressors on each other (proliferation and stress generation), and on mental health and executive functions.

The second model fit well with the data (Chi Square=.51.513, d.f.=33, p=.021, CFI=.993, RMSEA=.034). In the model, CPTSD accounted for the highest variable in the model (R=.776), followed by WMD (R=.766). In the model, type II-B trauma (childhood adversities) had medium to large size direct effects on type III-A trauma (intersected discrimination) (.44, p<.01) and type III-C trauma (intergroup conflict) (.33, p<.01). It had a direct and indirect effect on executive function deficits. Its total effects on executive function deficits were small to medium(.20, p<.01). Its direct effects on executive function accounted for 55% of its total effects. It had direct and indirect effects on mental health. Its total effects on mental health were medium to high (.36, p<.01). Its direct effects accounted for 31% of its total effects. It had medium to high indirect effects on CPTSD (.32, p<.01) and small to medium indirect effects on type III-D (community violence), anxiety, depression, PTSD, WMD, and ID. It had small, significant indirect effects on type III-E trauma (chronic, life-threatening conditions).

Type III-A trauma (intersected discriminations) had small to medium direct effects on executive function (.13, p<.03), type III-D trauma (community violence, .25, p<.03), and type III-E trauma (chronic, life-threatening condition, .12, p<.02). It had direct and indirect effects on mental health/ Its total effects on mental health were medium to large (.39, p<.01). It had an indirect medium to high effect size on CPTSD (.35, p<.01). It had a small to medium effect size on depression, PTSD, and anxiety.

Type III-C trauma (intergroup conflict) had small direct effects on executive function deficits (.10, p<.03). It had small to medium size effects on type II-D trauma (community violence, .26, p<.01), and type III-E trauma (chronic, life-threatening conditions, .11, p<.01). It had small indirect effects on mental health (.06, p<.03) and all mental health conditions.

Executive function deficits had a large effect size on mental health (.56, p<.02), with a large effect size on CPTSD (.50, p<.01) and a medium to high effect size on depression, PTSD, and anxiety. All mental health and executive function variables were highly loaded on their perspective latent variables. Table (3-S) in supplemental materials details the standardized direct, indirect, and total effects and their 95% confidence interval in the model. Figure (1-S) in supplemental materials depicts the direct effects.

Conclusions and Discussion

One of the strengths of the current study is validating the model of chronic and continuous traumatic stressors (type III trauma) with its variants in a non-Western less traumatized sample. Chronic stressors, type III trauma (continuous traumatic stressors including chronic stressors), Type III trauma-A (discrimination), and Type III trauma-B (childhood adversities) had higher proliferation potential than other trauma types in this non-Western sample. Type III traumas (continuous traumatic stressors), chronic stressors, and Type III trauma-A (discrimination) seem to have larger effect sizes on negative mental health and executive function deficits than type II trauma ( and type I trauma), followed by the significant impact of Type III trauma-B (childhood adversities). The results replicated similar findings in studies conducted on more traumatized samples (e.g., Kira, 2021b, Kira et al., 2022b).

The results underscored the significant role of chronic stressors through life and its significant dynamics of proliferation to other stressors and traumas. Chronic stressors negatively affect at least equally, if not more, mental health and cognitive function, compared to single past traumas. However, chronic stressors and hassles (micro-stressors) are primarily embedded in other trauma types and are hard to split, especially in the continuous traumatic stressors of the actual life of the traumatized.

The results of the impact of chronic stressors in animal models (e.g., Conrad, 2010; Katz et al., 1981) and humans (e.g., Bowman et al., 2003; Haight et al., 2023; McGonagle & Kessler, 1990) are consistent. They found that chronic stressors are more impactful on mental health and cognition than acute intermittent stressors. Several studies found that acute stressors were less predictive of mental health than chronic stressors (e.g., McGonagle & Kessler, 1990; Van der Ploeg & Kleber, 2003). A study found that chronic but not acute stressors were correlated with the severity of suicide ideation in veterans (Bryan et al., 2015). Chronic stress, and the resulting allostatic load, can cause an imbalance of neural circuitry sub-serving cognition, decision-making, anxiety, and mood (e.g., Juster et al., 2010; Lupien et al., 2018). The role of chronic stressors and CTS on mental health and cognition did not receive enough attention in the current traumatology, clinical psychology, or psychiatry that focused on acute stressors and traumas, due, probably to the artificial counterfactual separation between stress and trauma disciplines, and the current dominant conceptualization of traumatization dynamics.

Type III trauma-B- (childhood adversities) seems to have more potential proliferation, especially compared to type III trauma-A (discrimination). That finding was expected as childhood adversities precede discrimination early in life before the rise of identity in early adolescence when intense feelings of discrimination begin to rise. These findings are consistent with recent findings that childhood adversities exacerbate the association between discrimination and mental health symptomatology (Helminen et al., 2022). However, type III trauma-A (discrimination) seems to have a higher effect size on mental health, especially on CPTSD, the most severe, which may be due to its longer time scale as it is life-long continuous trauma, compared to childhood adversities that happened during childhood. In contrast, childhood adversities (Type III trauma-B) seem to have a slightly higher impact on executive function than discrimination in this population. That may be specific to the affluent Kuwaiti population, where discrimination and oppression are relatively less expected compared to higher intersected discrimination in Syrian internally displaced persons in a previous study (Kira et al., 2022b). Childhood adversities seem to leave long-lasting effects and profoundly shape how we think and process information, creating less adaptable attachment, emotional and thinking styles, schemas, and routines. Compared to all trauma types, executive functions seem to contribute to and mediate traumatization.

Another significant strength of the DBTF model is its ability to incorporate intergroup stressors that are more common in non-Western cultures. Unlike Western cultures, which tend to focus on interpersonal stressors, the model raises questions about the cross-cultural validity of trauma definitions and PTSD that are based solely on past interpersonal trauma. It suggests that if the traumas are ongoing, such as intergroup discriminations, the resulting symptoms may not be "post"-traumatic but rather "peri"-traumatic (e.g., Nicolas et al., 2015).

The current findings have notable implications. First, the results indicated the salience of non-Criterion “A” traumas/ stressors and dynamics in terms of their adverse outcomes and the importance of the expansion of stressors and dynamics that can be considered for PTSD Criterion “A”. They emphasized the need for another revision and adaptation of Criterion “A” to be consistent with the continuous real-life chronic and continuous stressors phenomena and the dynamics that generate traumatization. Some of our arguments and findings presented in this study are not new and may be considered reassertions and replications of research discussed in the introduction. However, the study provides a novel overarching framework and emphasizes the significance of continuous and chronic stressors, including their different variants. It also highlights the importance of accumulation and proliferation dynamics in contributing to the triggering events and traumatization. Essentially, the triggering event/s (potentially Current Criterion “A” event) , can be seen as the last straw, while the expected accumulation and proliferation dynamics are the actual cause of Post and Peri-trauma and stressor disorders. The study emphasized the importance of the non-linear dynamics of accumulation. The seemingly last stressor that may trigger the symptoms of PTSD can be just the last straw in chronic-continuous stressors. The accumulation and proliferation dynamics are the real etiology of symptoms and not the last straw.

Conceptually, current findings validated some of the main assumptions proposed by DBTF concerning the integration of chronic stressors and trauma in a unified paradigm of trauma types based on trauma severity, especially the type III trauma (continuous trauma) subtypes with differential effects on mental health and cognition. This integration is essential for a precise behavior science that reflects the differential experience of real life in real-time. For example, this separation between acute and chronic stressors in shaping the phenomena of traumatization may contribute to the unexplained differential effects of acute stressors on females. Discounting the impact of chronic stressors of gender discrimination in the traumatization dynamics may “masquerade” findings of the differential vulnerability of females (e.g., Anderson et al., 2021; Turner & Avison, 2003), leading to artefactual or incomplete science.

Such integrated conceptualization of stress and trauma disciplines and mental health and cognitions have important clinical implications. Complex trauma needs a sequence of personal interpersonal and intergroup relationship-based approaches (Courtois & Ford, 2012). Trauma-focused interventions may be modified to be chronic stressors and continuous traumas-focused interventions that address their Transdiagnostic mechanisms (e.g., Kira et al., 2015). Such needed modification should address cognitions and executive functions that were affected by chronic stress and severe traumas and have a profound impact on stress and cognitive and emotional processing. Further, realizing the social determinants of health, advocacy, activism, and fighting for equality should be part of the intervention strategy to reduce chronic and acute stressors from their original source. Fighting and the will to fight and survive were found to reduce distress and optimize executive functions (Kira et al., 2021h).

The current study, while having notable strengths, has numerous limitations. First, the results are culturally and trauma profile-dependent. Different cultures and samples with different trauma profiles may yield different modified results. The study was conducted with a random from college students but a mostly convenient sample. The measures we used in the study were based on self-reports. Self-reporting is subject to under- or over-reporting due to social desirability biases. In particular, the self-report of executive function (EF) may not represent the same cognitive structures as performance measures. Previous research has found that performance and self-report measures of EF measure complementary yet distinct constructs of cognitive control (Friedman, & Gustavson,2022). Future studies may use both performance and self-report measures.

Further, the study was cross-sectional. We cannot draw causal inferences in a cross-sectional design. Future studies may utilize longitudinal design when feasible. Also, we must warn that when we mention direct and indirect effects in SEM analysis, we express it in statistical probabilistic stochastic terms that use statistical techniques terms which are different from their meaning in deterministic sciences. Regardless of these limitations, the study provided initial empirical evidence of the validity of type III continuous stressors (acute and chronic) as the most severe, with intersected discrimination (Type III-a trauma) and childhood adversities (Type III-B trauma) as the most critical, with chronic stressors as the most traumatizing compared to acute stressors (trauma types I and II).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were following the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Alpay, E. H., Kira, I. A., Shuwiekh, H. A., Ashby, J. S., Turkeli, A., & Alhuwailah, A. (2021). The effects of COVID-19 continuous traumatic stress on mental health: The case of Syrian refugees in Turkey. Traumatology. Online first. [CrossRef]

- Alzarban, F. (2018). Indicators of urban health in the youth population of Kuwait City and Jahra, Kuwait. The University of Liverpool (United Kingdom) Ph.D. dissertation.

- Anderson, L. R., Monden, C. W., & Bukodi, E. (2021). Stressful life events, differential vulnerability, and depressive symptoms: critique and new evidence. Journal of Health and Social Behavior,. [CrossRef]

- Arpawong, T. E., Mekli, K., Lee, J., Phillips, D. F., Gatz, M., & Prescott, C. A. (2022). A longitudinal study shows stress proliferation effects from early childhood adversity and recent stress on risk for depressive symptoms among older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 26(4), 870–880. [CrossRef]

- Bellis, M. A., Hughes, K., Leckenby, N., Jones, L., Baban, A., Kachaeva, M., ... & Terzic, N. (2014). Adverse childhood experiences and associations with health-harming behaviors in young adults: surveys in eight eastern European countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 92, 641-655.

- Bowman, R. E., Beck, K. D., & Luine, V. N. (2003). Chronic stress effects on memory: sex differences in performance and monoaminergic activity. Hormones and Behavior, 43(1), 48-59. [CrossRef]

- Briere, J., Agee, E., & Dietrich, A. (2016). Cumulative trauma and current posttraumatic stressdisorder status in general population and inmate samples. Psychological trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 8(4), 439.

- Bryan, C. J., Clemans, T. A., Leeson, B., & Rudd, M. D. (2015). Acute vs. chronic stressors, multiple suicide attempts, and persistent suicide ideation in US soldiers. The Journal of nervous and mental disease, 203(1), 48-53. [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B. M. (2012). Choosing structural equation modeling computer software: Snapshots of LISREL, EQS, AMOS, and Mplus. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Handbook of structural equation modeling (pp. 307–324). The Guilford Press.

- Carter, R. T., Forsyth, J. M., Mazzula, S. L., & Williams, B. (2004). Racial discrimination and race-based traumatic stress: An exploratory investigation. Handbook of racial-cultural psychology and counseling, 2, 447-476.

- Cloitre, M., Shevlin, M., Brewin, C. R., Bisson, J. I., Roberts, N. P., Maercker, A., ... & Hyland, P. (2018). The International Trauma Questionnaire: Development of a self-report measure of ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 138(6), 536-546. [CrossRef]

- Cloitre, M., Stolbach, B. C., Herman, J. L., Kolk, B. V. D., Pynoos, R., Wang, J., & Petkova, E. (2009). A developmental approach to complex PTSD: Childhood and adult cumulative trauma as predictors of symptom complexity. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 22(5), 399-408. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1992). Statistical power analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 1(3), 98-101.

- Conrad, C. D. (2010). A critical review of chronic stress effects on spatial learning and memory. Progress in neuro-psychopharmacology and biological psychiatry, 34(5), 742-755. [CrossRef]

- Courtois, C. A., & Ford, J. D. (2012). Treatment of complex trauma: A sequenced, relationship-based approach. Guilford Press.

- Eagle, G., & Kaminer, D. (2013). Continuous traumatic stress: Expanding the lexicon of traumatic stress. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 19(2), 85. [CrossRef]

- Eckenrode, J. (1984). Impact of chronic and acute stressors on daily reports of mood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(4), 907–918.

- Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (2019). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 56(6), 774–786. [CrossRef]

- Finkelhor, D., Ormrod, R. K., & Turner, H. A. (2007). Poly-victimization: A neglected component in child victimization. Child abuse & neglect, 31(1), 7-26. [CrossRef]

- Ford, J. D., & Delker, B. C. (Eds.). (2020). Polyvictimization: Adverse impacts in childhood and across the lifespan. Routledge.

- Friedman, N. P., & Gustavson, D. E. (2022). Do rating and task measures of control abilities assess the same thing? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 31(3), 262-271.

- Gilboa, D., Friedman, M., & Tsur, H. (1994). The burn as a continuous traumatic stress: implications for emotional treatment during hospitalization. The Journal of burn care & rehabilitation, 15(1), 86-94. [CrossRef]

- Gold, S. D., Marx, B. P., Soler-Baillo, J. M., & Sloan, D. M. (2005). Is life stress more traumatic than traumatic stress? Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 19(6), 687-698.

- Green, J. G., McLaughlin, K. A., Berglund, P. A., Gruber, M. J., Sampson, N. A., Zaslavsky, A. M., & Kessler, R. C. (2010). Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication I: associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(2), 113-123.

- Greene, T., Itzhaky, L., Bronstein, I., & Solomon, Z. (2018). Psychopathology, risk, and resilience under exposure to continuous traumatic stress: A systematic review of studies among adults living in southern Israel. Traumatology, 24(2), 83. [CrossRef]

- Hahn, S. E., & Smith, C. S. (1999). Daily hassles and chronic stressors: Conceptual and measurement issues. Stress Medicine, 15(2), 89-101. [CrossRef]

- Haight, B. L., Peddie, L., Crosswell, A. D., Hives, B. A., Almeida, D. M., & Puterman, E. (2023). Combined effects of cumulative stress and daily stressors on daily health. Health Psychology, 42(5), 325. [CrossRef]

- Hailes, H. P., Yu, R., Danese, A., & Fazel, S. (2019). Long-term outcomes of childhood sexual abuse: an umbrella review. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(10), 830-839. [CrossRef]

- Helminen, E. C., Scheer, J. R., Edwards, K. M., & Felver, J. C. (2022). Adverse childhood experiences exacerbate the association between day-to-day discrimination and mental health symptomatology in undergraduate students. Journal of Affective Disorders, 297, 338-347. [CrossRef]

- Herman, J. L. (1992). Complex PTSD: A syndrome in survivors of prolonged and repeated trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 5(3), 377-391.

- Holmes, S. C., Facemire, V. C., & DaFonseca, A. M. (2016). Expanding Criterion A for posttraumatic stress disorder: Considering the deleterious impact of oppression. Traumatology, 22(4), 314–321. [CrossRef]

- Holst, Y., & Thorell, L. B. (2018). Adult executive functioning inventory (ADEXI): Validity, reliability, and relations to ADHD. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 27(1), e1567.

- Horesh, D., & Brown, A. D. (2020). Traumatic stress in the age of COVID-19: A call to close critical gaps and adapt to new realities. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(4), 331. [CrossRef]

- Juster, R. P., McEwen, B. S., & Lupien, S. J. (2010). Allostatic load biomarkers of chronic stress and impact on health and cognition. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(1), 2-16. [CrossRef]

- Katz, R. J., Roth, K. A., & Carroll, B. J. (1981). Acute and chronic stress effects on open field activity in the rat: implications for a model of depression. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 5(2), 247-251. [CrossRef]

- Kira, I. A., Alpay, E. H., Ayna, Y. E., Shuwiekh, H. A., Ashby, J. S., & Turkeli, A. (2021a). The effects of COVID-19 continuous traumatic stressors on mental health and cognitive functioning: A case example from Turkey. Current Psychology, 1-12. Online first. [CrossRef]

- Kira, I. A., Alpay, E. H., Turkeli, A., Shuwiekh, H. A., Ashby, J. S., & Alhuwailah, A. (2021b). The effects of COVID-19 traumatic stress on executive functions: The case of Syrian refugees in Turkey. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 1-21. Online first. [CrossRef]

- Kira, I. A., Ashby, J. S., Lewandowski, L., Alawneh, A. W. N., Mohanesh, J., & Odenat, L. (2013a). Advances in continuous traumatic stress theory: Traumatogenic dynamics and consequences of intergroup conflict: The Palestinian adolescents' case. Psychology, 4(04), 396. [CrossRef]

- Kira, I. A., Fawzi, M., Shuwiekh, H., Lewandowski, L., Ashby, J. S., & Al Ibraheem, B. (2021c). Do adding attachment, oppression, cumulative, and proliferation trauma dynamics to PTSD criterion “A” improve its predictive validity: Toward a paradigm shift? Current Psychology, 40(6), 2665-2679.

- Kira, I. A., Lewandowski, L., Somers, C. L., Yoon, J. S., & Chiodo, L. (2012). The effects of trauma types, cumulative trauma, and PTSD on IQ in two highly traumatized adolescent groups. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 4(1), 128. [CrossRef]

- Kira, I. A., Lewandowski, L., Templin, T., Ramaswamy, V., Ozkan, B., & Mohanesh, J. (2008). Measuring cumulative trauma dose, types, and profiles using a development-based taxonomy of traumas. Traumatology, 14(2), 62-87. [CrossRef]

- Kira, I. A., Rihan Ibrahim, E. S., Shuwiekh, H. A., & Ashby, J. S. (2021d). Does intersected discrimination underlie the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 infection and its severity on minorities? An example from Jordan. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Kira, I. A., Shuweikh, H., Al-Huwailiah, A., El-Wakeel, S. A., Waheep, N. N., Ebada, E. E., & Ibrahim, E. S. R. (2020b). The direct and indirect impact of trauma types and cumulative stressors and traumas on executive functions. Applied Neuropsychology: Adult, 1-17. Online first. [CrossRef]

- Kira, I. A., Shuwiekh, H. A., Alhuwailah, A., Ashby, J. S., Sous Fahmy Sous, M., Baali, S. B. A., ... & Jamil, H. J. (2021e). The effects of COVID-19 and collective identity trauma (intersectional discrimination) on social status and well-being. Traumatology, 27(1), 29. [CrossRef]

- Kira, I. A., Shuwiekh, H., Kucharska, J., Fawzi, M., Ashby, J. S., Omidy, A. Z., ... & Lewandowski, L. (2018). Trauma proliferation and stress generation (TPSG) dynamics and their implications for clinical science. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 88(5), 582. [CrossRef]

- Kira, I., Barger, B., Shuwiekh, H., Kucharska, J., & Al-Huwailah, A. (2020a). The threshold non-linear model for the effects of cumulative stressors and traumas: A chained cusp catastrophe analysis. Psychology, 11(3), 385-403. [CrossRef]

- Kira, I.; Ayna, Y.E.; Shuwiekh & Ashby, J.S.(2021h). The association of WTELS as a master motivator with higher executive functioning and better mental health. Current Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Kira, I.A. (2001). Taxonomy of trauma and trauma assessment. Traumatology, 2, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Kira, I.A. (2019). Toward an Integrative Theory of Self-identity and Identity Stressors and Traumas and its Mental Health Dynamic. Psychology, 10, 385-410. [CrossRef]

- Kira, I. A. (2022). Taxonomy of stressors and traumas: An update of the development-based trauma framework (DBTF): A life-course perspective on stress and trauma. Traumatology, 28(1), 84–97. [CrossRef]

- Kira, I.A. (2021b). The development-based taxonomy of stressors and traumas: An initial empirical validation. Psychology, 12, 1575-1614. [CrossRef]

- Kira, I.A.; Aljakoub, J.; Al Ibraheem, B.& Shuwiekh, H. (2022b). The Effects of Type III Traumatic Stressors of the Protracted Conflict and Prolonged COVID-19 on Syrians Internally Displaced: A Validation Study of Type III Continuous Traumatic Stressors and Their Impact. International Perspectives in Psychology. Online First.

- Kira, I.A.; Aljakoub, J.; Al Ibraheem, B.; Shuwiekh, H.; Ashby, J.S.(2022a): The etiology of Complex PTSD in the COVID-19 and continuous traumatic stressors era: A test of competing and allied models. Journal of Loss and Trauma: International Perspectives on Stress & Coping. [CrossRef]

- Kira, I.A.; Al-Noor, T.H.; Al-bayaty, Y.W.; Shuwiekh, H.; Ashby, J.S.& Jamil, H. (2022c). Intersected discrimination through the lens of COVID-19: The case example of the Christian minority in Iraq. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. [CrossRef]

- Kira, I.A.; Ashby, J.S.; Omidy, A.Z. & Lewandowski, L. (2015a). Current, Continuous, and Cumulative Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavior Therapy: A new model for trauma counseling. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 37: 323-340. [CrossRef]

- Kira, I.A.; Shuwiekh, H.; Alhuwailah, A.& Balaghi, D. ( 2021g). Does COVID-19 type III continuous existential trauma deplete traditional coping, diminish health and mental health, and kindle spirituality? : An exploratory study on Arab countries. Journal of Loss and Trauma: International Perspectives on Stress & Coping. Online first.

- Kira, I.A.; Shuwiekh, H.; Ashby, J.S.; Elwakeel, S.; Alhuwailah, A.; Sous, M.; Baali, S.; Azdaou, C.; Oliemat, E. &Jamil, H. (2021f). The Impact of COVID-19 traumatic stressors on mental health: Is COVID-19 a new trauma type? International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction.Online first.

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ- 9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606-613.

- Lahav, Y. (2020). Psychological distress related to COVID-19–the contribution of continuous traumatic stress. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 129-137. [CrossRef]

- Landecker, H., & Panofsky, A. (2013). From social structure to gene regulation, and back: A critical introduction to environmental epigenetics for sociology. Annual Review of Sociology, 39, 333-357. [CrossRef]

- Landers, A. L., Danes, S. M., Campbell, A. R., & Hawk, S. W. (2021). Abuse after abuse: the recurrent maltreatment of American Indian children in foster care and adoption. Child Abuse & Neglect, 111, 104805. [CrossRef]

- Larsen, S. E., & Pacella, M. L. (2016). Comparing the effect of DSM-congruent traumas vs. [CrossRef]

-

DSM-incongruent stressors on PTSD symptoms: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 38, 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.01.001. [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company.

- LeBouthillier, D. M., McMillan, K. A., Thibodeau, M. A., & Asmundson, G. J. (2015). Types and number of traumas associated with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in PTSD: Findings from a US nationally representative sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(3), 183-190.

- Liu, R. T., Hamilton, J. L., Boyd, S. I., Dreier, M. J., Walsh, R. F. L., Sheehan, A. E., Turnamian, M. R., Workman, A. R. C., & Jorgensen, S. L. (2024). A systematic review and Bayesian meta-analysis of 30 years of stress generation research: Clinical, psychological, and sociodemographic risk and protective factors for prospective negative life events.. Psychological Bulletin. Advance online publication. https://dx.doi.org/ 10.1037/bul0000431. [CrossRef]

- Lupien, S. J., Juster, R. P., Raymond, C., & Marin, M. F. (2018). The effects of chronic stress on the human brain: From neurotoxicity to vulnerability, to opportunity. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 49, 91-105. [CrossRef]

- Marin, T. J., Martin, T. M., Blackwell, E., Stetler, C., & Miller, G. E. (2007). Differentiating the impact of episodic and chronic stressors on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis regulation in young women. Health Psychology, 26(4), 447–455. [CrossRef]

- McGonagle, K. A., & Kessler, R. C. (1990). Chronic stress, acute stress, and depressive symptoms. American Journal of Community Psychology, 18(5), 681-706.

- Miller, K. E., & Rasmussen, A. (2010). War exposure, daily stressors, and mental health in conflict and post-conflict settings: bridging the divide between trauma-focused and psychosocial frameworks. Social Science & Medicine, 70(1), 7-16. [CrossRef]

- Monroe, S. M., & Simons, A. D. (1991). Diathesis-stress theories in the context of life stress research: implications for the depressive disorders. Psychological Bulletin, 110(3), 406.

- Nicolas, G., Wheatley, A., & Guillaume, C. (2015). Does one trauma fit all? Exploring the relevance of PTSD across cultures. International Journal of Culture and Mental Health, 8(1), 34-45. [CrossRef]

- Pat-Horenczyk, R., & Schiff, M. (2019). Continuous traumatic stress and the life cycle: Exposure to repeated political violence in Israel. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21(8), 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Pat-Horenczyk, R., Ziv, Y., Asulin-Peretz, L., Achituv, M., Cohen, S., & Brom, D. (2013). Relational trauma in times of political violence: Continuous versus past traumatic stress. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 19(2), 125. [CrossRef]

- Pearlin, L. I., Schieman, S., Fazio, E. M., & Meersman, S. C. (2005). Stress, health, and the life course: Some conceptual perspectives. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 46(2), 205-219.

- Potluri, S., & R. Patel, A. (2021). Using a continuous traumatic stress framework to examine ongoing adversity among Indian women from slums: A mixed-methods exploration. Journal of Traumatic Stress. Online first.

- Quinn, K. G., Spector, A., Takahashi, L., & Voisin, D. R. (2020). Conceptualizing the effects of continuous traumatic violence on HIV continuum of care outcomes for young Black men who have sex with men in the United States. AIDS and Behavior, 1-15. Online first. [CrossRef]

- Rnic, K., Santee, A. C., Hoffmeister, J. A., Liu, H., Chang, K. K., Chen, R. X., ... & LeMoult, J. (2023). The vicious cycle of psychopathology and stressful life events: A meta-analytic review testing the stress generation model. Psychological Bulletin, 149(5-6), 330. [CrossRef]

- Rosen, G.M., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2008). Posttraumatic stress disorder: An empirical evaluation of core assumptions. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(5), 837–868. [CrossRef]

- Sawaya, H., Atoui, M., Hamadeh, A., Zeinoun, P., & Nahas, Z. (2016). Adaptation and initial validation of the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder–7 Questionnaire (GAD-7) in an Arabic-speaking Lebanese psychiatric outpatient sample. Psychiatry Research, 239, 245-252. [CrossRef]

- Serido, J., Almeida, D. M., & Wethington, E. (2004). Chronic stressors and daily hassles: Unique and interactive relationships with psychological distress. Journal of health and social behavior, 45(1), 17-33. [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, D., Landau, M. J., & Kay, A. C. (2012). Toward a comprehensive understanding of existential threat: Insights from Paul Tillich. Social Cognition, 30(6), 734-757.

- Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092-1097.

- Stein, J. Y., Levin, Y., Gelkopf, M., Tangir, G., & Solomon, Z. (2018). Traumatization or habituation? A four-wave investigation of exposure to continuous traumatic stress in Israel. International Journal of Stress Management, 25(S1), 137. [CrossRef]

- Tai, D. B. G., Shah, A., Doubeni, C. A., Sia, I. G., & Wieland, M. L. (2021). The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 72(4), 703-706. [CrossRef]

- Terr, L. C. (1995). Childhood traumas. Psychotraumatology, 301-320.

- Turner, R. J, Avison, W.R. (2003). Status Variations in Stress Exposure: Implications for the Interpretation of Research on Race, Socioeconomic Status, and Gender. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 44(4):488–505. [CrossRef]

- Williams, M. T., Haeny, A. M., & Holmes, S. C. (2021). Posttraumatic stress disorder and racial trauma. PTSD Research Quarterly, 32(1), 1–9.

- Van der Ploeg, E., & Kleber, R. J. (2003). Acute and chronic job stressors among ambulance personnel: predictors of health symptoms. Occupational and environmental medicine, 60(suppl 1), i40-i46. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).