Submitted:

06 November 2024

Posted:

06 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

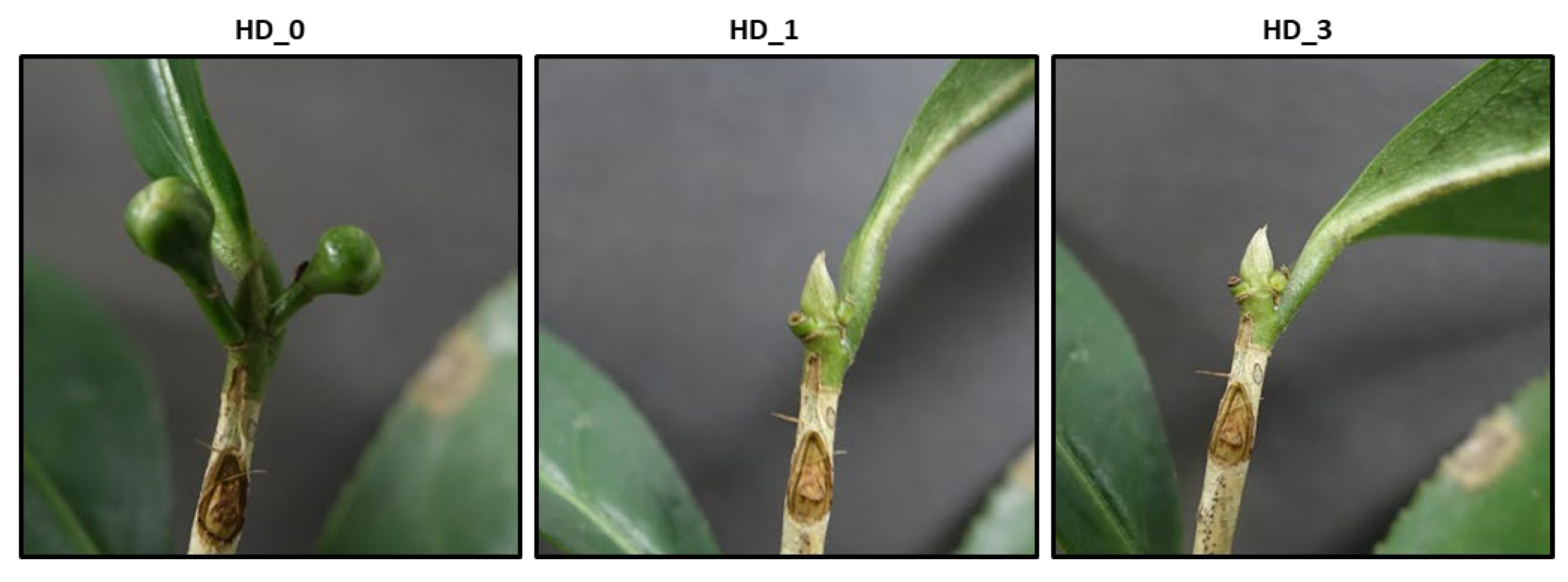

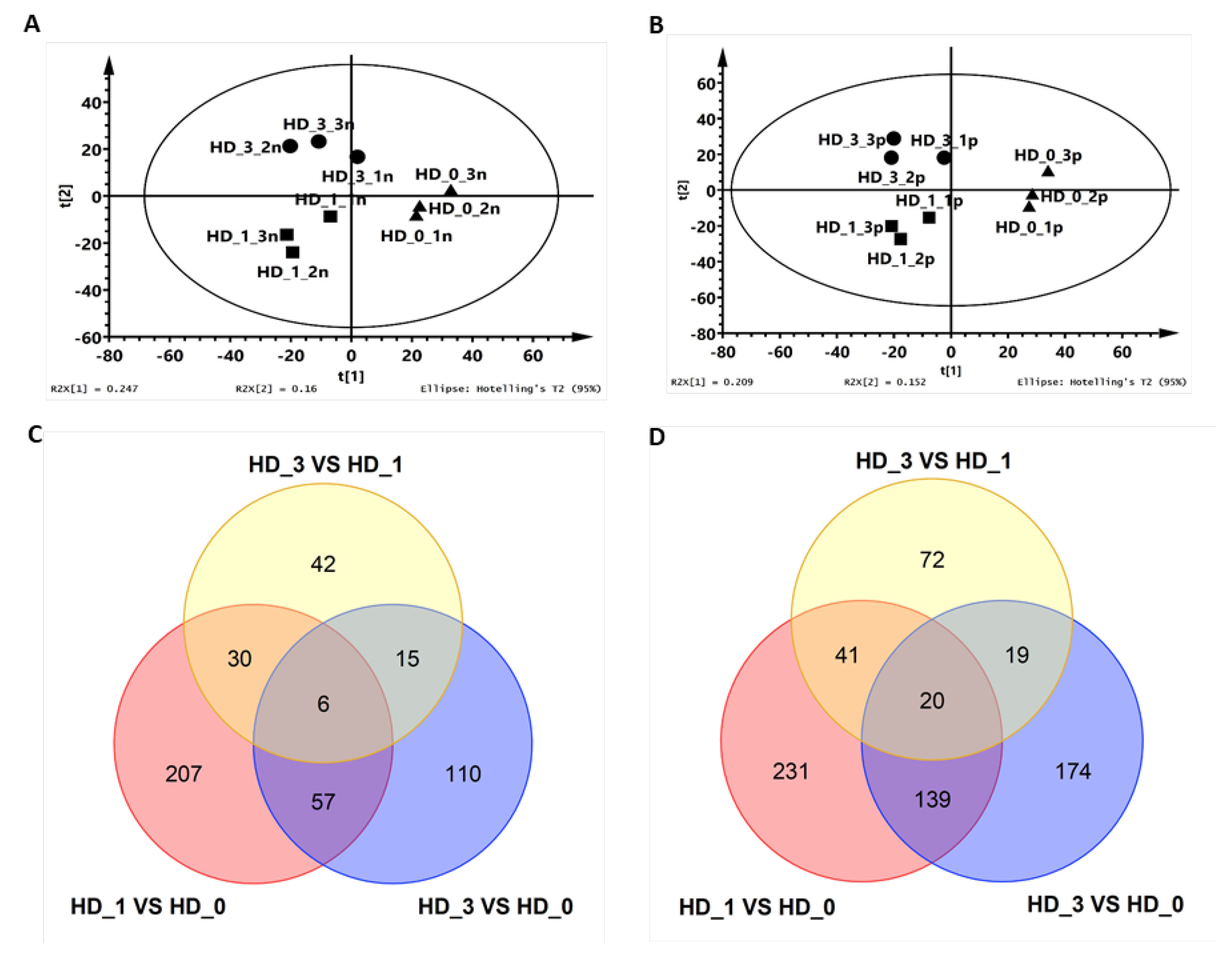

2.1. The Axillary Shoot Bud Metabolome Was Altered One Day After Local Floral Bud Removal

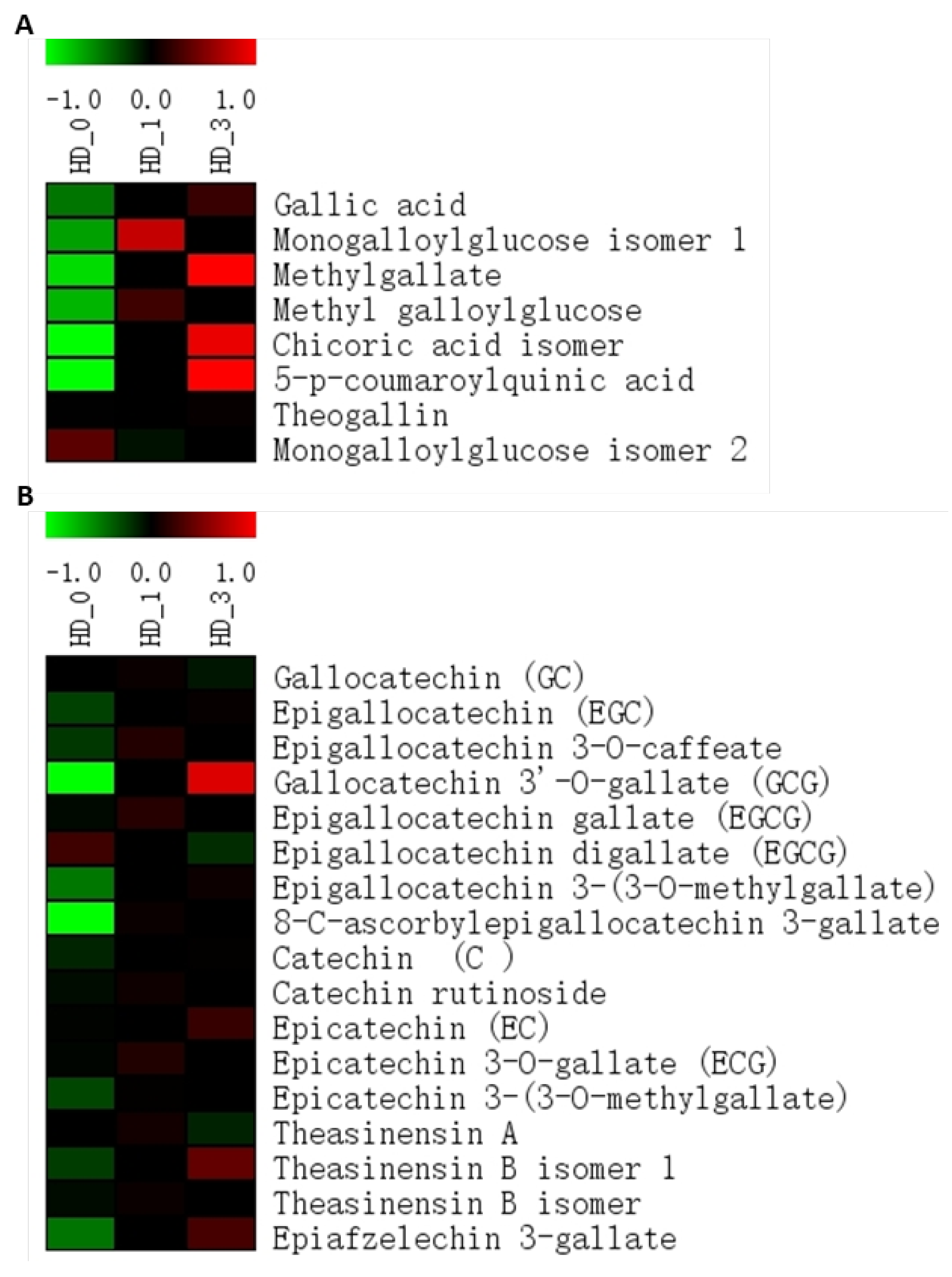

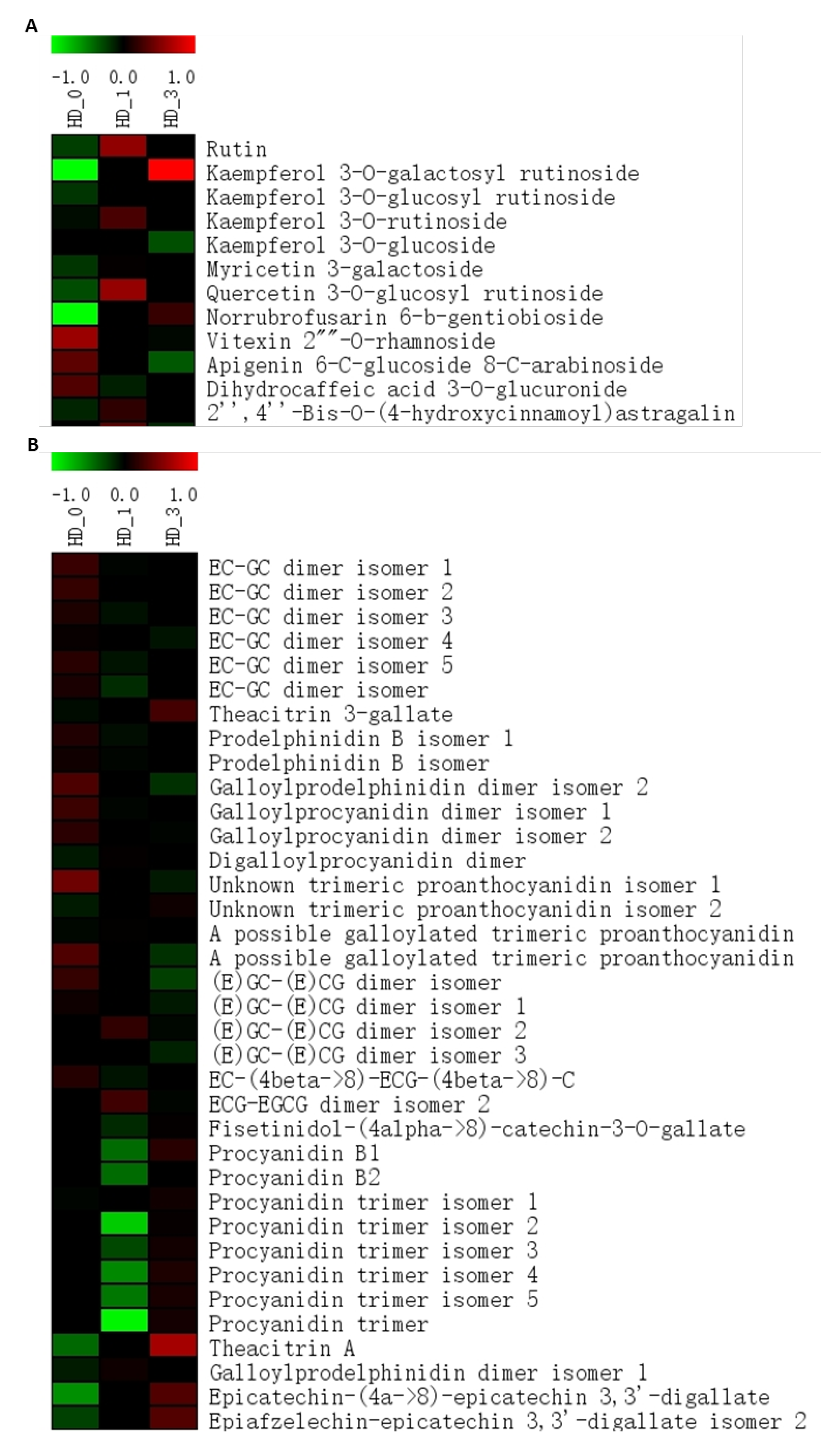

2.2. Flavonoids and Alkaloids

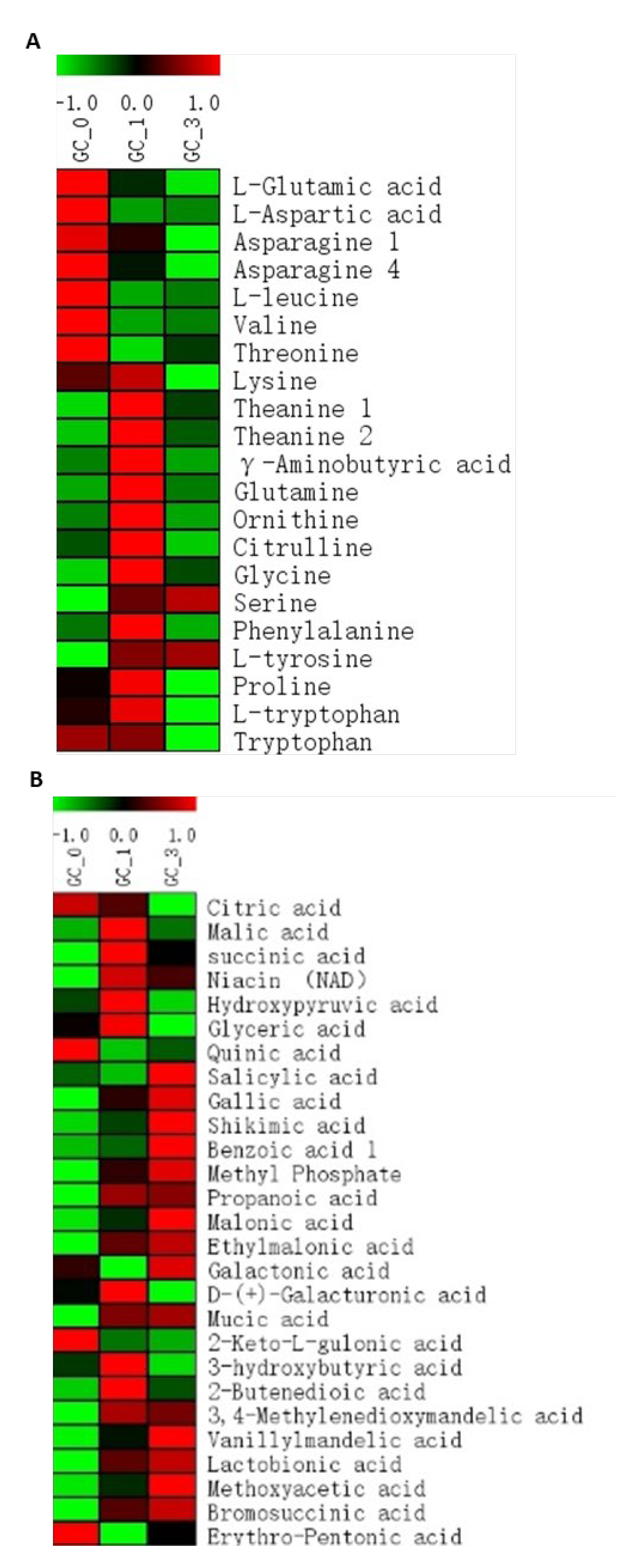

2.3. Amino Acids

2.4. Organic Acids

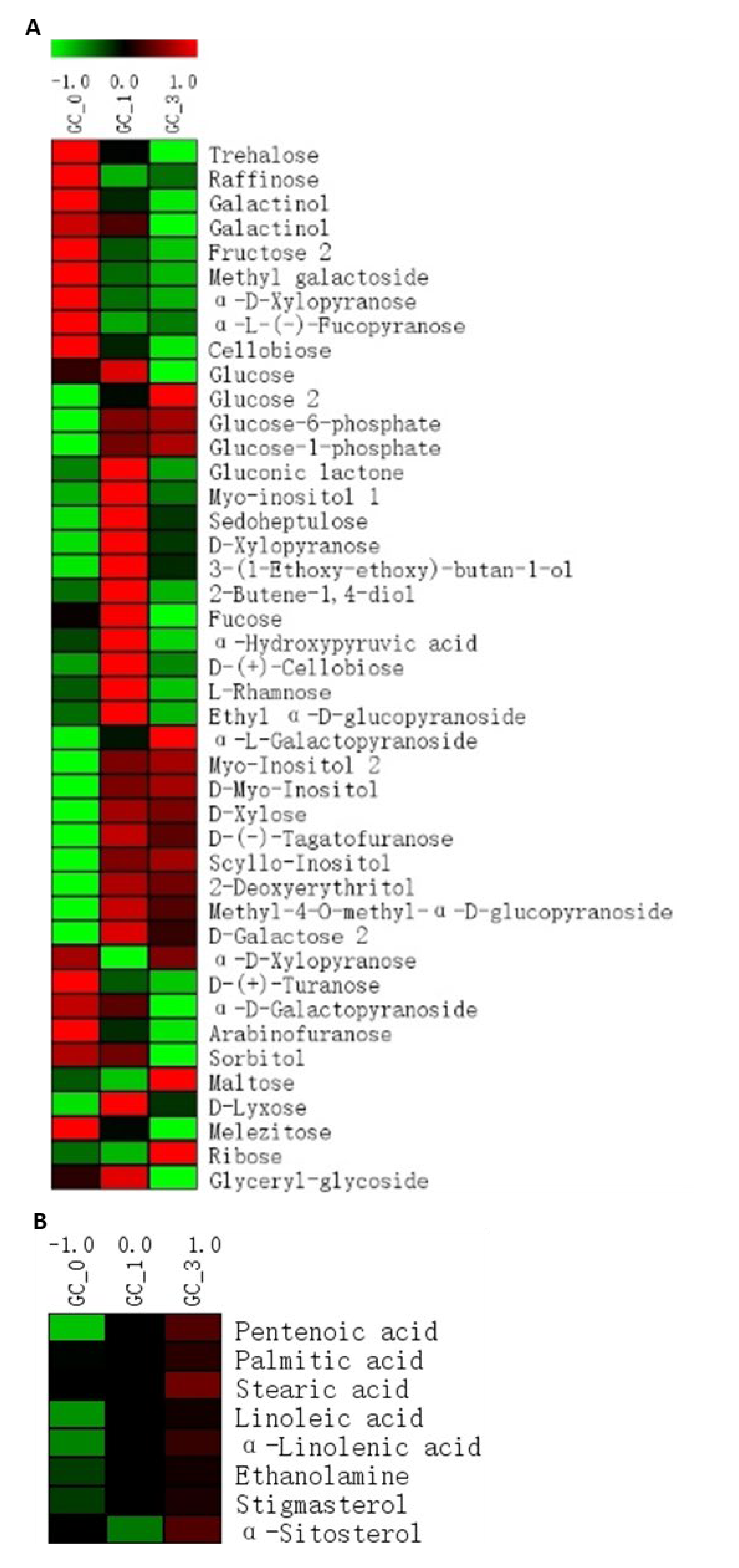

2.5. Sugars and Sugar Alcohols

2.6. Free Fatty Acids and Sterols

3. Discussion

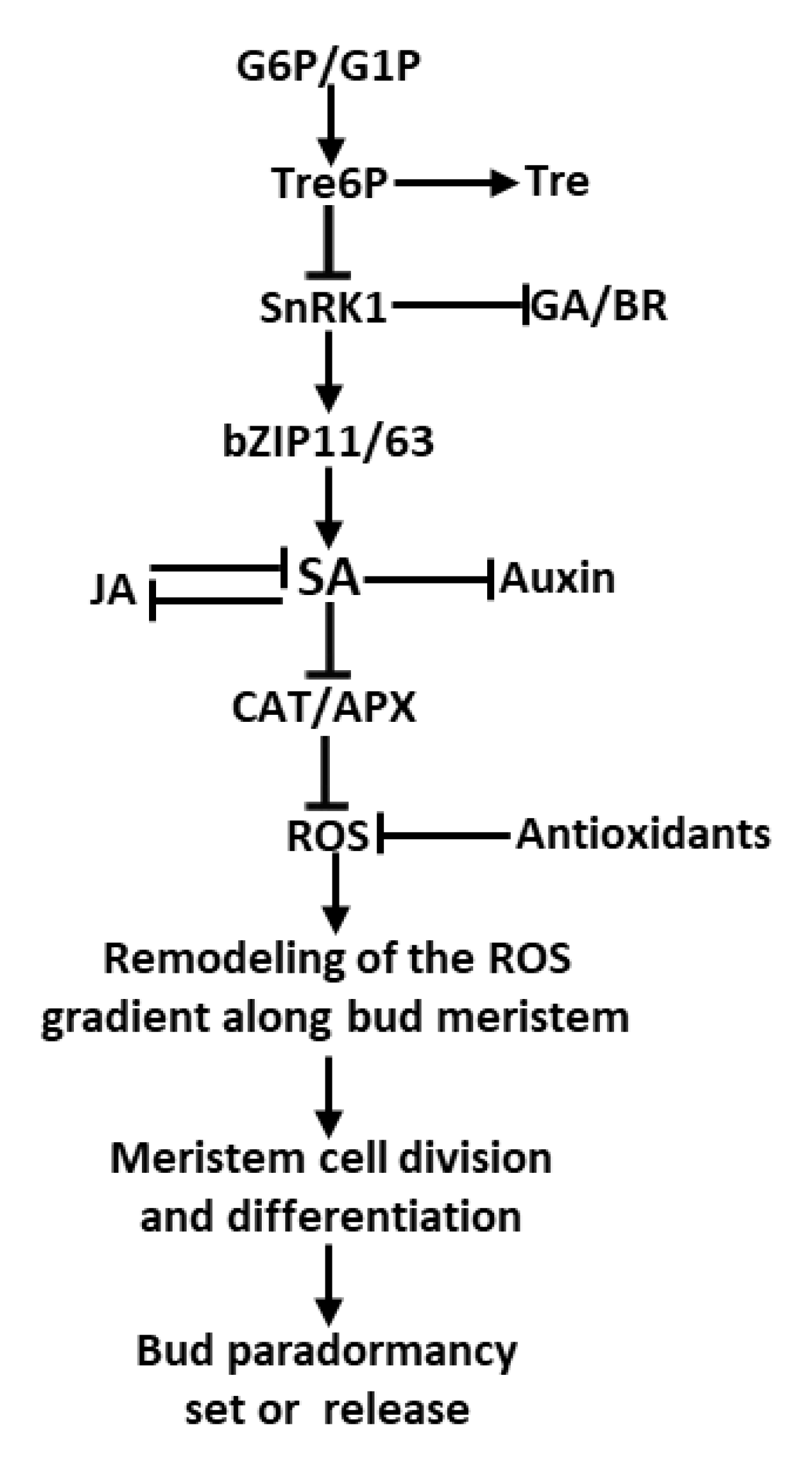

3.1. Tre6P-SA Signaling May Participate Carbon Starvation-Induced Paradormancy in Tea Axillary Shoot Buds

3.2. C and N Coordination in the Axillary Shoot Buds

3.3. The Potential Roles of 3-HB for Phenylpropanoid Reconfiguration During Paradormancy-to- Growth Transition in the Axillary Shoot Buds

3.4. The Non-Enzymatic Antioxidants Remodeling Could Regulate Meristematic Cell Activity and the Paradormancy-to-Growth Transition in the Axillary Shoot Buds

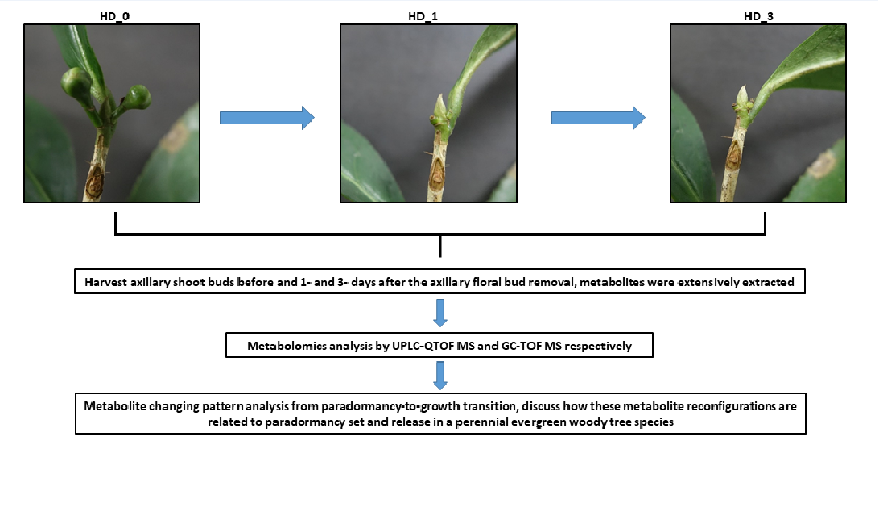

4. Materials and Methods

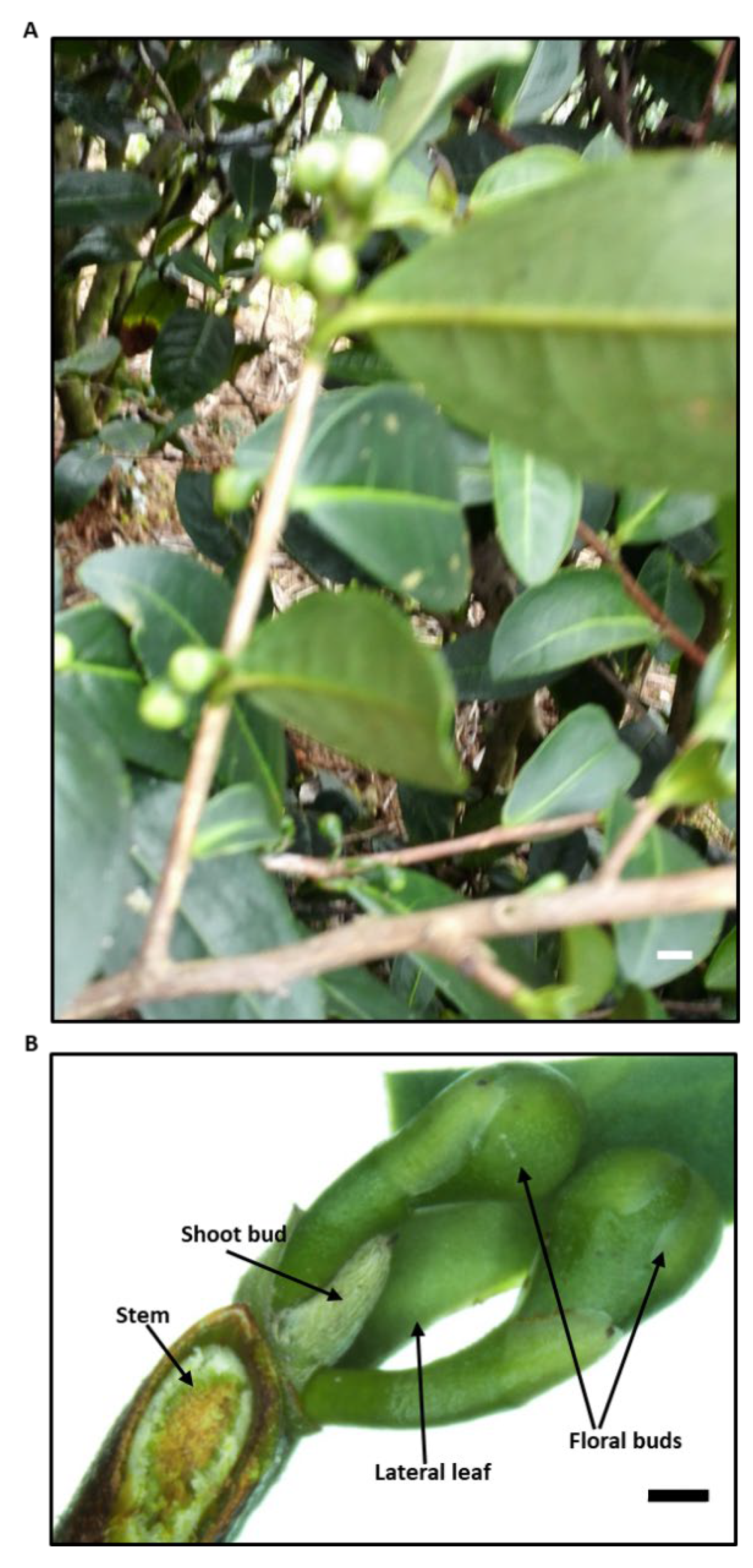

4.1. Plant Material

4.2. Metabolite Extraction

4.3. GC-TOF MS Analysis

4.4. UPLC-QTOF MS Analysis

4.5. Data Processing

4.6. PLS-DA and Heat-Map Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Garrison, R. Studies in the development of axillary buds. Am. J. Bot. 1955, 42, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, D.N. Seasonal Dormancy in Tea (Camellia sinensis L.). Nature 1969, 224, 514–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, J.E.K.; Eriksson, M.E.; Junttila, O. The dynamic nature of bud dormancy in trees: environmental control and molecular mechanisms. Plant, Cell Environ. 2012, 35, 1707–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, D.P. , Anderson, J. V., Chao, W.S., Foley, M.E. Knowing when to grow: signals regulating bud dormancy. Trends Plant Sci. 2003, 8, 534–540. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, A.; Kumar, S. Responses to winter dormancy, temperature, and plant hormones share gene networks. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2011, 11, 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, G.A.; Early, J.D.; Martin, G.C.; Darnell, R.L. Endo-, Para-, and Ecodormancy: Physiological Terminology and Classification for Dormancy Research. HortScience 1987, 22, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.V.; Gesch, R.W.; Jia, Y.; Chao, W.S.; Horvath, D.P. Seasonal shifts in dormancy status, carbohydrate metabolism, and related gene expression in crown buds of leafy spurge. Plant, Cell Environ. 2005, 28, 1567–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, A.; Yu, J.; E Staton, M.; Audergon, J.-M.; Roch, G.; Decroocq, V.; Knagge, K.; Chen, H.; Zhebentyayeva, T.; Liu, Z.; et al. Association of the phenylpropanoid pathway with dormancy and adaptive trait variation in apricot (Prunus armeniaca). Tree Physiol. 2019, 39, 1136–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Cueto, J.; Ionescu, I.A.; Pičmanová, M.; Gericke, O.; Motawia, M.S.; Olsen, C.E.; Campoy, J.A.; Dicenta, F.; Møller, B.L.; Sánchez-Pérez, R. Cyanogenic Glucosides and Derivatives in Almond and Sweet Cherry Flower Buds from Dormancy to Flowering. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Tang, H.; Wang, Y.; He, Y.; Ou, Y.; Sun, X.; Wang, S.; Yao, Y. Tomato SlAN11 regulates flavonoid biosynthesis and seed dormancy by interaction with bHLH proteins but not with MYB proteins. Hortic. Res. 2018, 5, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillamón, J.G.; Prudencio. S.; Yuste, J.E.; Dicenta, F.; Sánchez-Pérez, R. Ascorbic acid and prunasin, two candidate biomarkers for endodormancy release in almond flower buds identified by a nontargeted metabolomic study. Hortic. Res. 2020, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, H.; Blanke, M. Changes in carbohydrate levels and relative water content (RWC) to distinguish dormancy phases in sweet cherry. J. Plant Physiol. 2017, 218, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruttink, T.; Arend, M.; Morreel, K.; Storme, V.; Rombauts, S.; Fromm, J.; Bhalerao, R.P.; Boerjan, W.; Rohde, A. A Molecular Timetable for Apical Bud Formation and Dormancy Induction in Poplar. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 2370–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinne, P.L.; Paul, L.K.; Vahala, J.; Kangasjärvi, J.; van der Schoot, C. Axillary buds are dwarfed shoots that tightly regulate GA pathway and GA-inducible 1,3-β-glucanase genes during branching in hybrid aspen. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 5975–5991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Yang, Q.; Ni, J.; Gao, Y.; Tang, Y.; Bai, S.; Teng, Y. Early defoliation induces auxin redistribution, promoting paradormancy release in pear buds. Plant Physiol. 2022, 190, 2739–2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, C.; Kozarewa, I.; Johansson, M.; Ögren, E.; Rohde, A.; Eriksson, M.E. Circadian Clock Components Regulate Entry and Affect Exit of Seasonal Dormancy as Well as Winter Hardiness in Populus Trees. Plant Physiol. 2010, 153, 1823–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, H.; Sugiura, T.; Ito, D. Changes in Hydrogen Peroxide Content in Flower Buds of Japanese Pear(Pyrus pyrifolia Nakai) in Relation to Breaking of Endodormancy. J. Jpn. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2002, 71, 610–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzitelli, L.; Hancock, R.D.; Haupt, S.; Walker, P.G.; Pont, S.D.A.; McNicol, J.; Cardle, L.; Morris, J.; Viola, R.; Brennan, R.; et al. Co-ordinated gene expression during phases of dormancy release in raspberry (Rubus idaeus L.) buds. J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 1035–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, F.J.; Vergara, R.; Rubio, S. H2O2 is involved in the dormancy-breaking effect of hydrogen cyanamide in grapevine buds. Plant Growth Regul. 2008, 55, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreekantan, L.; Mathiason, K.; Grimplet, J.; Schlauch, K.; Dickerson, J.A.; Fennell, A.Y. Differential floral development and gene expression in grapevines during long and short photoperiods suggests a role for floral genes in dormancy transitioning. Plant Mol. Biol. 2010, 73, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.-M.; Walton, E.F.; Richardson, A.C.; Wood, M.; Hellens, R.P.; Varkonyi-Gasic, E. Conservation and divergence of four kiwifruit SVP-like MADS-box genes suggest distinct roles in kiwifruit bud dormancy and flowering. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 63, 797–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, W.; Shi, T.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J. Differential expression of proteins associated with seasonal bud dormancy at four critical stages in Japanese apricot. Plant Biol. 2012, 15, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Q. ROS: Important factor in plant stem cell fate regulation. J. Plant Physiol. 2023, 289, 154082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, J.; Dong, Z.; Wu, H.; Tian, Z.; Zhao, Z. Redox regulation of plant stem cell fate. EMBO J. 2017, 36, 2844–2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, D.P.; Chao, W.S.; Suttle, J.C.; Thimmapuram, J.; Anderson, J.V. Transcriptome analysis identifies novel responses and potential regulatory genes involved in seasonal dormancy transitions of leafy spurge (Euphorbia esula L.). BMC Genom. 2008, 9, 536–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leida, C.; Terol, J.; Martí, G.; Agustí, M.; Llácer, G.; Badenes, M.L.; Ríos, G. Identification of genes associated with bud dormancy release in Prunus persica by suppression subtractive hybridization. Tree Physiol. 2010, 30, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Gao, Z.; Zhuang, W.; Shi, T.; Zhang, Z.; Ni, Z. Genome-wide expression profiles of seasonal bud dormancy at four critical stages in Japanese apricot. Plant Mol. Biol. 2013, 83, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanton, T.W. The Banjhi (Dormancy) Cycle in Tea (camellia sinensis). Exp. Agric. 1981, 17, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arana, M.V.; la Rosa, N.M.-D.; Maloof, J.N.; Blázquez, M.A.; Alabadí, D. Circadian oscillation of gibberellin signaling in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2011, 108, 9292–9297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Yang, Y.; Yue, C.; Wang, L.; Horvath, D.P.; Wang, X. Comprehensive Transcriptome Analyses Reveal Differential Gene Expression Profiles of Camellia sinensis Axillary Buds at Para-, Endo-, Ecodormancy, and Bud Flush Stages. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagar, P.K.; Kumar, A. Changes in endogenous gibberellin activity during winter dormancy in tea (Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze). Acta Physiol. Plant. 2000, 22, 439–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagar, P.K. Changes in endogenous abscisic acid and phenols during winter dormancy in tea [Camellia sinensis L. (O) Kuntze]. Acta Physiol. Plant. 1996, 18, 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Nagar, P.K.; Sood, S. Changes in endogenous auxins during winter dormancy in tea (Camellia sinensis L.) O. Kuntze. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2006, 28, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, S.K. , Palni, L.M.S. Shoot growth and winter dormancy in tea. In: NAIR, M. K (ed.): PLACROSYM X. 1992. J. Plant Crops 1993, 21 (Suppl.), 328–332.

- Wang, X.-C.; Zhao, Q.-Y.; Ma, C.-L.; Zhang, Z.-H.; Cao, H.-L.; Kong, Y.-M.; Yue, C.; Hao, X.-Y.; Chen, L.; Ma, J.-Q.; et al. Global transcriptome profiles of Camellia sinensis during cold acclimation. BMC Genom. 2013, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Hao, X.; Ma, C.; Cao, H.; Yue, C.; Wang, L.; Zeng, J.; Yang, Y. Identification of differential gene expression profiles between winter dormant and sprouting axillary buds in tea plant (Camellia sinensis) by suppression subtractive hybridization. Tree Genet. Genomes 2014, 10, 1149–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, W.S.; Serpe, M.D. Changes in the expression of carbohydrate metabolism genes during three phases of bud dormancy in leafy spurge. Plant Mol. Biol. 2009, 73, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, D.P. Role of mature leaves in inhibition of root bud growth inEuphorbia esulaL. Weed Sci. 1999, 47, 544–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarancón, C.; González-Grandío, E.; Oliveros, J.C.; Nicolas, M.; Cubas, P. A Conserved Carbon Starvation Response Underlies Bud Dormancy in Woody and Herbaceous Species. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.-N.; Qian, W.-J.; Wang, L.; Cao, H.-L.; Hao, X.-Y.; Yang, Y.-J.; Wang, X.-C. Isolation and expression features of hexose kinase genes under various abiotic stresses in the tea plant ( Camellia sinensis ). J. Plant Physiol. 2017, 209, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, W.; Yue, C.; Wang, Y.; Cao, H.; Li, N.; Wang, L.; Hao, X.; Wang, X.; Xiao, B.; Yang, Y. Identification of the invertase gene family (INVs) in tea plant and their expression analysis under abiotic stress. Plant Cell Rep. 2016, 35, 2269–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, C.; Cao, H.-L.; Wang, L.; Zhou, Y.-H.; Huang, Y.-T.; Hao, X.-Y.; Wang, Y.-C.; Wang, B.; Yang, Y.-J.; Wang, X.-C. Effects of cold acclimation on sugar metabolism and sugar-related gene expression in tea plant during the winter season. Plant Mol. Biol. 2015, 88, 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunn, J.E.; Delorge, I.; Figueroa, C.M.; Van Dijck, P.; Stitt, M. Trehalose metabolism in plants. Plant J. 2014, 79, 544–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, M.J.; Primavesi, L.F.; Jhurreea, D.; Zhang, Y. Trehalose Metabolism and Signaling. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008, 59, 417–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena-González, E.; Lunn, J.E. SnRK1 and trehalose 6-phosphate – two ancient pathways converge to regulate plant metabolism and growth. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2020, 55, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Zeng, L.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Liao, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Fu, X.; Yang, Z. Metabolism of Gallic Acid and Its Distributions in Tea (Camellia sinensis) Plants at the Tissue and Subcellular Levels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gao, L.; Liu, L.; Yang, Q.; Lu, Z.; Nie, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xia, T. Purification and Characterization of a Novel Galloyltransferase Involved in Catechin Galloylation in the Tea Plant (Camellia sinensis). J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 44406–44417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemetz, R.; Gross, G.G. Enzymology of gallotannin and ellagitannin biosynthesis. Phytochemistry 2005, 66, 2001–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Kong, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhou, H.; Fang, D.; Yue, W.; Chen, C. Metabolomic Profiling in Combination with Data Association Analysis Provide Insights about Potential Metabolic Regulation Networks among Non-Volatile and Volatile Metabolites in Camellia sinensis cv Baijiguan. Plants 2022, 11, 2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; Gil, M.I.; Castañer, M.; Artés, F.; Saltveit, M.E. Effect of Selected Browning Inhibitors on Phenolic Metabolism in Stem Tissue of Harvested Lettuce. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1997, 45, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlernitzauer, A.; Oiry, C.; Hamad, R.; Galas, S.; Cortade, F.; Chabi, B.; Casas, F.; Pessemesse, L.; Fouret, G.; Feillet-Coudray, C.; et al. Chicoric Acid Is an Antioxidant Molecule That Stimulates AMP Kinase Pathway in L6 Myotubes and Extends Lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e78788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Yoo, G.; Randy, A.; Kim, H.S.; Nho, C.W. Chicoric acid attenuate a nonalcoholic steatohepatitis by inhibiting key regulators of lipid metabolism, fibrosis, oxidation, and inflammation in mice with methionine and choline deficiency. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipchock, J.M.; Hendrickson, H.P.; Douglas, B.B.; Bird, K.E.; Ginther, P.S.; Rivalta, I.; Ten, N.S.; Batista, V.S.; Loria, J.P. Characterization of Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase 1B Inhibition by Chlorogenic Acid and Cichoric Acid. Biochemistry 2016, 56, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, R.A.; Sarnala, S. Proanthocyanidin Biosynthesis—a Matter of Protection. Plant Physiol. 2020, 184, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohanpuria, P.; Kumar, V.; Ahuja, P.S.; Yadav, S.K. Agrobacterium-Mediated Silencing of Caffeine Synthesis through Root Transformation in Camellia sinensis L. Mol. Biotechnol. 2010, 48, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, E.-H.; Zhang, H.-B.; Sheng, J.; Li, K.; Zhang, Q.-J.; Kim, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, T.; Li, W.; et al. The Tea Tree Genome Provides Insights into Tea Flavor and Independent Evolution of Caffeine Biosynthesis. Mol. Plant 2017, 10, 866–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Rao, R.S.P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhong, C.; Thelen, J.J. Metabolite variation in hybrid corn grain from a large-scale multisite study. Crop. J. 2016, 4, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Yang, F.; Hou, W.; Jiang, S.; Yang, R.; Zhang, W.; Chen, M.; Yan, Y.; Tian, Y.; Yuan, H. Dynamic Variation of Amino Acid Contents and Identification of Sterols in Xinyang Mao Jian Green Tea. Molecules 2022, 27, 3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C. , Yang, H., Wang, S., Zhao, J., Liu, C., Gao, L., Xia, E., Lu, Y., Tai, Y., She, G., et al., 2018. Draft genome sequence of Camellia sinensis var. sinensis provides insights into the evolution of the tea genome and tea quality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 115, E4145–E4158.

- Chellamuthu, V.-R.; Ermilova, E.; Lapina, T.; Lüddecke, J.; Minaeva, E.; Herrmann, C.; Hartmann, M.D.; Forchhammer, K. A Widespread Glutamine-Sensing Mechanism in the Plant Kingdom. Cell 2014, 159, 1188–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fait, A.; Nesi, A.N.; Angelovici, R.; Lehmann, M.; Pham, P.A.; Song, L.; Haslam, R.P.; Napier, J.A.; Galili, G.; Fernie, A.R. Targeted Enhancement of Glutamate-to-γ-Aminobutyrate Conversion in Arabidopsis Seeds Affects Carbon-Nitrogen Balance and Storage Reserves in a Development-Dependent Manner. Plant Physiol. 2011, 157, 1026–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanamori, T. , Matsumoto, H. Glutamine synthase from rice plant roots. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1972, 152, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. , Lee, C. B., Kim, S.G., Kwon, Y.M. Purification carbamoyltransferase and characterization of ornithine from the chloroplasts of Canavalia lineata leaves. Plant Science 1997, 122, 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, A.; Last, R.L. A Regulatory Hierarchy of the Arabidopsis Branched-Chain Amino Acid Metabolic Network. Plant Cell 2017, 29, 1480–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, V.; Laubengayer, K.M.; Schauer, N.; Fernie, A.R.; Jander, G. Two Arabidopsis Threonine Aldolases Are Nonredundant and Compete with Threonine Deaminase for a Common Substrate Pool. Plant Cell 2006, 18, 3564–3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Mohamed, H.; Vadel, A.M.; Geuns, J.M.; Khemira, H. Biochemical changes in dormant grapevine shoot tissues in response to chilling: Possible role in dormancy release. Sci. Hortic. 2010, 124, 440–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auslender, E.L.; Dorion, S.; Dumont, S.; Rivoal, J. Expression, purification and characterization of Solanum tuberosum recombinant cytosolic pyruvate kinase. Protein Expr. Purif. 2015, 110, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, R.C.; Steinfath, M.; Lisec, J.; Becher, M.; Witucka-Wall, H.; Törjék, O.; Fiehn, O.; Eckardt. ; Willmitzer, L.; Selbig, J.; et al. The metabolic signature related to high plant growth rate in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2007, 104, 4759–4764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, K.B.; Boldingh, H.L.; Shilton, R.S.; Laing, W.A. Changes in quinic acid metabolism during fruit development in three kiwifruit species. Funct. Plant Biol. 2009, 36, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, C.M.; Escamilla-Trevino, L.; Yarce, J.C.S.; Kim, H.; Ralph, J.; Chen, F.; Dixon, R.A. An essential role of caffeoyl shikimate esterase in monolignol biosynthesis in Medicago truncatula. Plant J. 2016, 86, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, L.; Maury, S.; Martz, F.; Geoffroy, P.; Legrand, M. Purification, Cloning, and Properties of an Acyltransferase Controlling Shikimate and Quinate Ester Intermediates in Phenylpropanoid Metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaña, A.A.; Kamimura, N.; Soumyanath, A.; Stevens, J.F.; Maier, C.S. Caffeoylquinic acids: chemistry, biosynthesis, occurrence, analytical challenges, and bioactivity. Plant J. 2021, 107, 1299–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlot, A.C.; Dempsey, D.M.A.; Klessig, D.F. Salicylic acid, a multifaceted hormone to combat disease. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2009, 47, 177–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hildebrandt, T.M.; Nesi, A.N.; Araújo, W.L.; Braun, H.-P. Amino Acid Catabolism in Plants. Mol. Plant 2015, 8, 1563–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isherwood, F.A.; Chen, Y.T.; Mapson, L.W. Synthesis of l-ascorbic acid in plants and animals. Biochem. J. 1954, 56, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, H.; Wang, J.; Liu, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Ouyang, J. [Production of mucic acid from pectin-derived D-galacturonic acid: a review]. . 2022, 38, 666–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Z.; Xia, Y.; Kai, G.; Chen, W.; Tang, K. Metabolic Engineering of Plant L-Ascorbic Acid Biosynthesis: Recent Trends and Applications. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2007, 27, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahatma, M.K.; Thawait, L.K.; Jadon, K.S.; Thirumalaisamy, P.P.; Bishi, S.K.; Rathod, K.J.; Verma, A.; Kumar, N.; Golakiya, B.A. Metabolic profiling for dissection of late leaf spot disease resistance mechanism in groundnut. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2021, 27, 1027–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierziak, J.; Wojtasik, W.; Kulma, A.; Dziadas, M.; Kostyn, K.; Dymińska, L.; Hanuza, J.; Żuk, M.; Szopa, J. 3-Hydroxybutyrate Is Active Compound in Flax that Upregulates Genes Involved in DNA Methylation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Morales, P.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J.; Tapia, E. Ketone bodies, stress response, and redox homeostasis. Redox Biol. 2019, 29, 101395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Zhang, D.; Chung, D.; Tang, Z.; Huang, H.; Dai, L.; Qi, S.; Li, J.; Colak, G.; Chen, Y.; et al. Metabolic Regulation of Gene Expression by Histone Lysine β-Hydroxybutyrylation. Mol. Cell 2016, 62, 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X. , Van den Ende, W. , Van Laere, A., Cheng, S., Bennett, J. Structure, evolution and expression of the two invertase families of rice. J. Mol. Evol. 2005, 60, 615–634. [Google Scholar]

- Salvi, P.; Varshney, V.; Majee, M. Raffinose family oligosaccharides (RFOs): role in seed vigor and longevity. Biosci. Rep. 2022, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, F. , Pharr, D.M., 1996. “Metabolism of carbohydrates in sinks and sources: galactosyl-sucrose oligosaccharides,” in Photoassimilate Distribution in Plants and Crops: Source–Sink Relationships, eds E. Zamski and A. A. Schaffer (New York: Marcel Dekker), 157–183.

- dos Santos, R.; Vergauwen, R.; Pacolet, P.; Lescrinier, E.; Ende, W.V.D. Manninotriose is a major carbohydrate in red deadnettle (Lamium purpureum, Lamiaceae). Ann. Bot. 2012, 111, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Hao, G.; Han, Q.; Dirk, L.M.A.; Downie, A.B.; Ruan, Y.-L.; Wang, J.; et al. Raffinose synthase enhances drought tolerance through raffinose synthesis or galactinol hydrolysis in maize and Arabidopsis plants. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 8064–8077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, M.J. Trehalose 6-phosphate. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 2007, 10, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.M.; Villalobos, E.; Araújo, S.S.; Leyman, B.; Van Dijck, P.; Alfaro-Cardoso, L.; Fevereiro, P.S.; Torné, J.M.; Santos, D.M. Transformation of tobacco with an Arabidopsis thaliana gene involved in trehalose biosynthesis increases tolerance to several abiotic stresses. Euphytica 2005, 146, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishizawa, A.; Yabuta, Y.; Shigeoka, S. Galactinol and Raffinose Constitute a Novel Function to Protect Plants from Oxidative Damage. Plant Physiol. 2008, 147, 1251–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Ende, W. Multifunctional fructans and raffinose family oligosaccharides. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Wan, S.; He, J.; Yu, Y. Accumulation of Galactinol and ABA Is Involved in Exogenous EBR-Induced Drought Tolerance in Tea Plants. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 13391–13403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, K.D.; McKersie, B.D. Peroxidation reactions in plant membranes: Effects of free fatty acids. Lipids 1994, 29, 877–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brendel, K.; Corredor, C.F.; Bressler, R. The effect of 4-pentenoic acid on fatty acid oxidation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1969, 34, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, H. Inhibitors of fatty acid oxidation. Life Sci. 1987, 40, 1443–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mudd, S.H.; Datko, A.H. Synthesis of Ethanolamine and Its Regulation in Lemna paucicostata. Plant Physiol. 1989, 91, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbier, F.; Péron, T.; Lecerf, M.; Perez-Garcia, M.-D.; Barrière, Q.; Rolčík, J.; Boutet-Mercey, S.; Citerne, S.; Lemoine, R.; Porcheron, B.; et al. Sucrose is an early modulator of the key hormonal mechanisms controlling bud outgrowth in Rosa hybrida. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 2569–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, M.G.; Ross, J.J.; Babst, B.A.; Wienclaw, B.N.; Beveridge, C.A. Sugar demand, not auxin, is the initial regulator of apical dominance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 6092–6097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirma, M.; Araújo, W.L.; Fernie, A.R.; Galili, G. The multifaceted role of aspartate-family amino acids in plant metabolism. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 4995–5001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, L.D. , Baud, S. , Gilday, A., Li, Y., Graham, I. Delayed embryo development in the Arabidopsis trehalose 6-phosphate synthase 1 mutant is associated with altered cell wall structure, decreased cell division and starch accumulation. Plant J. 2006, 46, 69–84. [Google Scholar]

- Schluepmann, H.; Pellny, T.; van Dijken, A.; Smeekens, S.; Paul, M. Trehalose 6-phosphate is indispensable for carbohydrate utilization and growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2003, 100, 6849–6854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghdam, M.S.; Asghari, M.; Khorsandi, O.; Mohayeji, M. Alleviation of postharvest chilling injury of tomato fruit by salicylic acid treatment. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 51, 2815–2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapenna, D.; Ciofani, G.; Pierdomenico, S.D.; Neri, M.; Cuccurullo, C.; Giamberardino, M.A.; Cuccurullo, F. Inhibitory activity of salicylic acid on lipoxygenase-dependent lipid peroxidation. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Gen. Subj. 2009, 1790, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Rong, D.; Chen, D.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, R.; Wu, S.; Yamamuro, C. Salicylic acid promotes quiescent center cell division through ROS accumulation and down-regulation of PLT1, PLT2, and WOX5. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2020, 63, 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heil, M.; Ton, J. Long-distance signalling in plant defence. Trends Plant Sci. 2008, 13, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, J. Plants under attack: Systemic signals in defense. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2009, 12, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caarls, L.; Pieterse, C.M.J.; Van Wees, S.C.M. How salicylic acid takes transcriptional control over jasmonic acid signaling. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 170–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thaler, J.S.; Humphrey, P.T.; Whiteman, N.K. Evolution of jasmonate and salicylate signal crosstalk. Trends Plant Sci. 2012, 17, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, W.S.; Doğramaci, M.; Horvath, D.P.; Anderson, J.V.; Foley, M.E. Phytohormone balance and stress-related cellular responses are involved in the transition from bud to shoot growth in leafy spurge. BMC Plant Biol. 2016, 16, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, G.T.; Horvath, D.P.; Dharmawardhana, P.; Priest, H.D.; Mockler, T.C.; Strauss, S.H. Extensive Transcriptome Changes During Natural Onset and Release of Vegetative Bud Dormancy in Populus. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 989–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C. , Schluepmann, H. , Delatte, T.L., Wingler, A., Silva, A.B., Fevereio, P.S., Jansen, M., Fiorani, F., Wiese-Klinkenberg, A., Paul, M. Regulation of growth by the trehalose pathway: Relationship to temperature and sucrose. Plant Signal. Behav. 2013, 8, 12. [Google Scholar]

- O’hara, L.E.; Paul, M.J.; Wingler, A. How Do Sugars Regulate Plant Growth and Development? New Insight into the Role of Trehalose-6-Phosphate. Mol. Plant 2013, 6, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeekens, S.; Ma, J.; Hanson, J.; Rolland, F. Sugar signals and molecular networks controlling plant growth. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2010, 13, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Primavesi, L.F.; Jhurreea, D.; Andralojc, P.J.; Mitchell, R.A.; Powers, S.J.; Schluepmann, H.; Delatte, T.; Wingler, A.; Paul, M.J. Inhibition of SNF1-Related Protein Kinase1 Activity and Regulation of Metabolic Pathways by Trehalose-6-Phosphate. Plant Physiol. 2009, 149, 1860–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena-González, E.; Rolland, F.; Thevelein, J.M.; Sheen, J. A central integrator of transcription networks in plant stress and energy signalling. Nature 2007, 448, 938–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radchuk, R.; Radchuk, V.; Weschke, W.; Borisjuk, L.; Weber, H. Repressing the Expression of the SUCROSE NONFERMENTING-1-RELATED PROTEIN KINASE Gene in Pea Embryo Causes Pleiotropic Defects of Maturation Similar to an Abscisic Acid-Insensitive Phenotype. Plant Physiol. 2005, 140, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filipe, O.; De Vleesschauwer, D.; Haeck, A.; Demeestere, K.; Höfte, M. The energy sensor OsSnRK1a confers broad-spectrum disease resistance in rice. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, R.; De Vleesschauwer, D.; Sharma, M.K.; Ronald, P.C. Recent Advances in Dissecting Stress-Regulatory Crosstalk in Rice. Mol. Plant 2013, 6, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janda, T.; Szalai, G.; Pál, M. Salicylic Acid Signalling in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kianersi, F.; Abdollahi, M.R.; Mirzaie-Asl, A.; Dastan, D.; Rasheed, F. Identification and tissue-specific expression of rutin biosynthetic pathway genes in Capparis spinosa elicited with salicylic acid and methyl jasmonate. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Sun, L.; Ma, C.; Li, L.; Li, G.; Hao, L. Reducing basal salicylic acid enhances Arabidopsis tolerance to lead or cadmium. Plant Soil 2013, 372, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jander, G.; Joshi, V. Aspartate-Derived Amino Acid Biosynthesis inArabidopsis thaliana. Arab. Book 2009, 7, e0121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, V. , Jander, G. Arabidopsis methionine g-lyase is regulated according to isoleucine biosynthesis needs but plays a subordinate role to threonine deaminase. Plant Physiology 2009, 151, 367–378. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, B.M. , Ghassemian, M. Comprehensive post-genomic data analysis approaches integrating biochemical pathwaymaps. Phytochemistry 2005, 66, 413–451. [Google Scholar]

- Arcadi, A.; Morlacci, V.; Palombi, L. Synthesis of Nitrogen-Containing Heterocyclic Scaffolds through Sequential Reactions of Aminoalkynes with Carbonyls. Molecules 2023, 28, 4725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, S.S.; Tuteja, N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 909–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waszczak, C.; Carmody, M.; Kangasjärvi, J. Reactive Oxygen Species in Plant Signaling. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2018, 69, 209–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apel, K. , Hirt, H., 2004. Reactive oxygen species: metabolism, oxidative stress, and signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 55, 373–399.

- Chapman, J.M.; Muhlemann, J.K.; Gayomba, S.R.; Muday, G.K. RBOH-Dependent ROS Synthesis and ROS Scavenging by Plant Specialized Metabolites To Modulate Plant Development and Stress Responses. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2019, 32, 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, I.; Chacón, O.; Rodriguez, R.; Portieles, R.; López, Y.; Pujol, M.; Borrás-Hidalgo, O. Black shank resistant tobacco by silencing of glutathione S-transferase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 387, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandaswami, C. , Middleton, E., 1994. Free radical scavenging and antiocidant activity of plant flavonoids. Free Radicals in Diagnostic Medicine, Edited by D. Annstrong, Plenum Press, New York.

- Løvdal, T.; Olsen, K.M.; Slimestad, R.; Verheul, M.; Lillo, C. Synergetic effects of nitrogen depletion, temperature, and light on the content of phenolic compounds and gene expression in leaves of tomato. Phytochemistry 2010, 71, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukagoshi, H. Control of root growth and development by reactive oxygen species. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2016, 29, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Yu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, Y.; Wan, S.; Kong, X.; Ding, Z. ROS: The Fine-Tuner of Plant Stem Cell Fate. Trends Plant Sci. 2018, 23, 850–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panche, A.N.; Diwan, A.D.; Chandra, S.R. Flavonoids: An overview. J. Nutr. Sci. 2016, 5, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csepregi, K.; Hideg, É. Phenolic Compound Diversity Explored in the Context of Photo-Oxidative Stress Protection. Phytochem. Anal. 2017, 29, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietta, P.G. Flavonoids as antioxidants. J. Nat. Prod. 2000, 63, 1035–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saslowsky, D.E.; Warek, U.; Winkel, B.S. Nuclear Localization of Flavonoid Enzymes in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 23735–23740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watkins, J.M.; Hechler, P.J.; Muday, G.K. Ethylene-Induced Flavonol Accumulation in Guard Cells Suppresses Reactive Oxygen Species and Moderates Stomatal Aperture. Plant Physiol. 2014, 164, 1707–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, N.; Dupuis, J.H.; Yada, R.Y.; Kitts, D.D. Chlorogenic acid isomers directly interact with Keap 1-Nrf2 signaling in Caco-2 cells. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 457, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, R.A. , Xie, D. -Y., Sharma, S.B. Proanthocyanidins—a final frontier in flavonoid research? New Phytologist 2005, 165, 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, S.; Andrabi, S.M.H.; Riaz, A.; Durrani, A.Z.; Ahmad, N. Trehalose improves semen antioxidant enzymes activity, post-thaw quality, and fertility in Nili Ravi buffaloes ( Bubalus bubalis ). Theriogenology 2016, 85, 954–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnoff, N.; Cumbes, Q.J. Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of compatible solutes. Phytochemistry 1989, 28, 1057–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, L.; Lima, E.; Motta, M.; Marcone, M.; Baptista, J. Variability of antioxidant properties, catechins, caffeine, L-theanine and other amino acids in different plant parts of Azorean Camellia sinensis. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2020, 3, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Dickman, M.B. From The Cover: Proline suppresses apoptosis in the fungal pathogen Colletotrichum trifolii. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 3459–3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, S.; Hadi, N.; Khan, N.U.; Hadi, S.M. Antioxidant and prooxidant properties of caffeine, theobromine and xanthine. Med. Sci. Monit. 2003, 9, 325–330. [Google Scholar]

- Tsukagoshi, H.; Busch, W.; Benfey, P.N. Transcriptional Regulation of ROS Controls Transition from Proliferation to Differentiation in the Root. Cell 2010, 143, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Thelen, J.J. Plastid Uridine Salvage Activity Is Required for Photoassimilate Allocation and Partitioning in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 2991–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, W.; Sun, W.; Rao, R.S.P.; Ye, N.; Yang, Z.; Chen, M. Non-targeted metabolomics reveals distinct chemical compositions among different grades of Bai Mudan white tea. Food Chem. 2019, 277, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tautenhahn, R.; Cho, K.; Uritboonthai, W.; Zhu, Z.; Patti, G.J.; Siuzdak, G. An accelerated workflow for untargeted metabolomics using the METLIN database. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 826–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horai, H.; Arita, M.; Kanaya, S.; Nihei, Y.; Ikeda, T.; Suwa, K.; Ojima, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Tanaka, S.; Aoshima, K.; et al. MassBank: a public repository for sharing mass spectral data for life sciences. J. Mass Spectrom. 2010, 45, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishart, D.S. , Jewison, T. , Guo, A.C., Wilson, M., Knox, C., Liu, Y., Djoumbou, Y., Mandal, R., Aziat, F., Dong, E., Bouatra, S., Sinelnikov, I., Arndt, D., Xia, J., Liu, P., Yallou, F., Bjorndahl, T., Perez-Pineiro, R., Eisner, R., Allen, F., Neveu, V., Greiner, R., Scalbert, A. HMDB 3.0–the human metabolome database in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D801–D807. [Google Scholar]

- Afendi, F.M.; Okada, T.; Yamazaki, M.; Hirai-Morita, A.; Nakamura, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Ikeda, S.; Takahashi, H.; Amin, A.U.; Darusman, L.K.; et al. KNApSAcK Family Databases: Integrated Metabolite–Plant Species Databases for Multifaceted Plant Research. Plant Cell Physiol. 2011, 53, e1–e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, Y.; Nakabayashi, R.; Yamada, Y.; Suzuki, M.; Sato, M.; Sakata, A.; Akiyama, K.; Sakurai, T.; Matsuda, F.; Aoki, T.; et al. RIKEN tandem mass spectral database (ReSpect) for phytochemicals: A plant-specific MS/MS-based data resource and database. Phytochemistry 2012, 82, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).