1. Introduction

Almost five years ago, the first Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) case, caused by the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was reported in the city of Wuhan in China from a suspected zoonotic source [

1]. Ever since, COVID-19 quickly developed into a pandemic, launching a global health crisis alert and causing more than seventy million reported infections and more than a million registered mortalities [

1,

2]. The casualties of the pandemic also extended beyond confirmed COVID-19 cases, deaths, and catastrophic economic and social impacts and reached healthcare systems [

3].

Due to the highly infective nature of COVID-19, one of the most prominent changes that were mandated in healthcare systems is the rapid integration of “telehealth” [

4]. Telehealth has been described in literature as a “technology- enhanced health care framework,” which encompasses distant monitoring of patients, virtual clinics and consultations, and personal electronic health records accessible by patients through their mobile phones [

4].

Virtual clinics –whether they were audio-only virtual visits or audio-video virtual visits- have been a cornerstone modality of telehealth in many health institutions during the COVID-19 outbreak [

5,

6]. Nonetheless, patients’ and physicians’ satisfaction with the quick transition from in-person regular clinics to virtual clinics have been noted in literature across a number of different medical and surgical specialties, including gastroenterology [

6], endocrinology [

7], urology [

8], emergency medicine [

9], rheumatology [

10], pediatrics [

11], and obstetrics and gynecology [

4,

5,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

A study conducted in urology revealed that teleconsultation was perceived to have been a good experience by 80% of the physicians and 84% of the patients. Different specialties perceived the impact and level of challenge in regard to the patient-physician relationship, delivery manner, and diagnostic process differently [

17]. Along with surgeons, obstetricians and gynecologists felt the least challenged [

17]. Telehealth found its firm footing in gynecology through its many applications such as preconception counselling, infertility workup, mental health, preventive care, family and contraception planning, teleradiology, telesurgery, cervical cancer screening and colposcopy, and -particularly- in well-woman care [

14]. Telehealth integration into gynecology was noted to not only be effective for the continuation of both injectable and oral contraception but to also increase oral contraception rates at the 6-month point [

18]. It is no surprise that telehealth integration into the field of obstetrics and gynecology was shown to be highly accepted and valued by both of the physicians and patients [

7]. In fact, compared to traditional care, patients who utilized antenatal virtual clinics were shown to report higher satisfaction rates (79% versus 94%,

p<.01), lower pregnancy-related stress, increased nursing time (108 minutes versus 171 minutes), and similar perceived quality of care and clinical outcomes [

12].

Up to the researchers’ knowledge, only one telemedicine-focused study was conducted in Saudi Arabia in which the positive experience and high satisfaction rates of health care providers and patients in diabetes virtual clinics were noted [

7]. However, no study was conducted in Saudi Arabia that focused on physicians’ and patients’ perception and satisfaction with gynecological virtual clinics. Therefore, this study aimed to examine patients’ and physicians’ perceptions of telemedicine by determining each group’s perception and satisfaction level towards the recent integration of audio-only gynecology virtual clinics in a tertiary healthcare hospital in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

2. Materials and Methods

This is a cross-sectional study in which a non-probability convenient sampling technique was followed for the quantitative data collection. After obtaining the Institutional Review Board approval and the participants’ approval, data was collected during the one-year period from March 2021 to March 2022 at a tertiary healthcare hospital in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

The study’s target population was divided into two groups: the patient group and the physician group. The patient group included all female patients who virtually visited the gynecology clinic of the tertiary hospital during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Walk-in female patients who had no gynecology virtual clinic experience and who only physically attended the obstetrics and gynecology clinic without a previous virtual clinic appointment or visit were excluded. As for the physician group, it included obstetrics and gynecology residents, specialists, fellows, and consultants of all subspecialties who have attended to the virtual clinics. Interns and rotating residents were excluded.

Two forms of the questionnaire were utilized, Version A for the patients and Version B for the physicians. Version A (patients’ questionnaire) incorporated two validated questionnaires, the Short Assessment of Patient Satisfaction (SAPS) and the Antenatal and Neonatal Guidelines, Education, and Learning Systems Patient Satisfaction with Telehealth Questionnaire (ANGELS PSTQ) [

19,

20]. Version B (physicians’ questionnaire) consisted of one validated questionnaire, the Antenatal and Neonatal Guidelines, Education, and Learning Systems Provider Satisfaction with Telehealth Questionnaire (ANGELS PrSTQ) [

20].

The patients’ version of the questionnaire (Version A) was either self-administered or interviewer-administered. Physical copies of the questionnaire were made available at the gynecology clinics and were provided by the nurses to patients who had previous virtual visits to the gynecology clinic. Moreover, patients with previous experience with gynecology virtual clinics were contacted through phone calls. A structured interview approach based on the question outline of the questionnaire was followed, and the responses were administered by the interviewer. On the other hand, the physicians’ version of the questionnaire (Version B) was self-administered. An electronic version of the questionnaire was supplied to all physicians who attended to gynecology clinics.

2.1. Statistical Analysis

Data was extracted from the physical and electronic data collection sheets and then coded and refined into two separate Microsoft Excel sheets (one sheet for the physicians’ responses and another sheet for the patients’ responses). Data was first cleaned and then exported into the Statistical Package of Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23.0 for statistical analysis. Categorical data was described by means of percentages and pie charts. As for inferential statistics, variables were compared using the Fisher’s Exact Test. A p-value (p) less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

From March 2021 to March 2022, a total number of 220 study subjects participated in the study. Physicians accounted for 24.5% of the population (n = 54), while patients accounted for 75.5% (n = 166). The demographic data of the two populations is summarized in

Table 1.

Physicians’ experiences and perceptions of audio-only virtual gynecology clinics are shown in

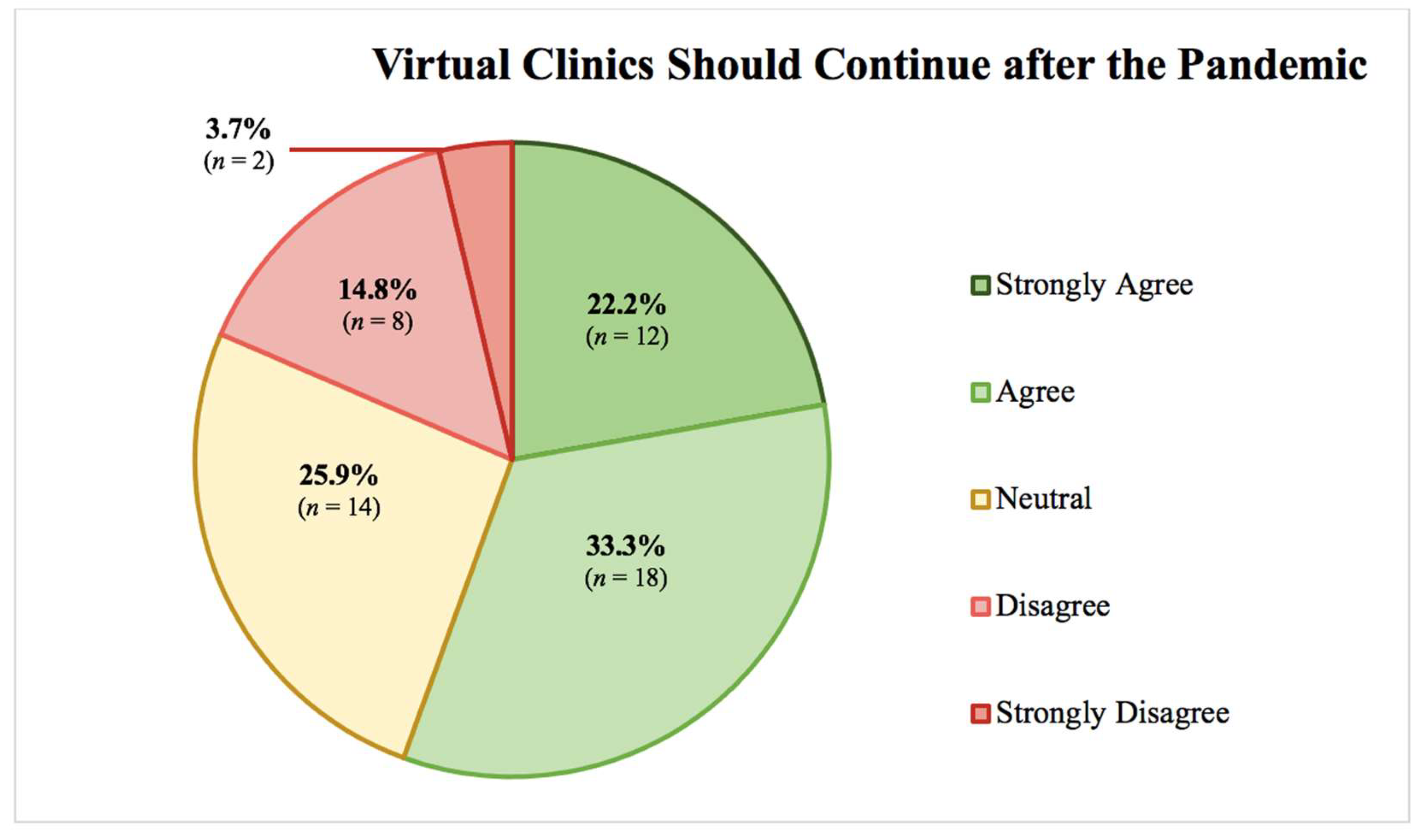

Table 2. More than half of the physicians (61.1%) reported that they were able to reach the patient from the first call about half the time only, while only 37% expressed that they were usually able to speak to the patient. Almost half of the physicians (48.1%) found that physical examination was indicated about half the time and that they have seldomly asked the patient to attend physically to the clinic. Overall, 55.5% of the physicians either agreed or strongly agreed that virtual clinics should continue after the pandemic, while only 18.5% of them either disagreed or strongly disagreed with the continuation, as shown in

Figure 1. Neither gender nor age showed a statistical significance; however, registrars and consultants were more likely to agree that virtual clinics are more convenient to see a larger number of patients in an optimal way, with a statistical significance of p = 0.029. Moreover, the association between years of experience and ability to speak directly to the patient was statistically significant (p = 0.013), with those with two to five years of experience were more likely to only be able to speak directly to the patient half of the time. Physicians who seldom found physical examination to be indicated or requested patients to attend physically to the clinic were more likely to desire continuing virtual clinics after the pandemic, with a strong statistical significance of p < 0.001. Furthermore, physicians who believed that virtual clinics improve healthcare access to patients, are an acceptable way to provide healthcare services, are a convenient method of seeing a larger number of patients in an optimal way, and are an adequate replacement when in-patient visits are difficult were all more likely to desire continuing virtual clinics after the pandemic, with a strong statistical significance of p < 0.001.

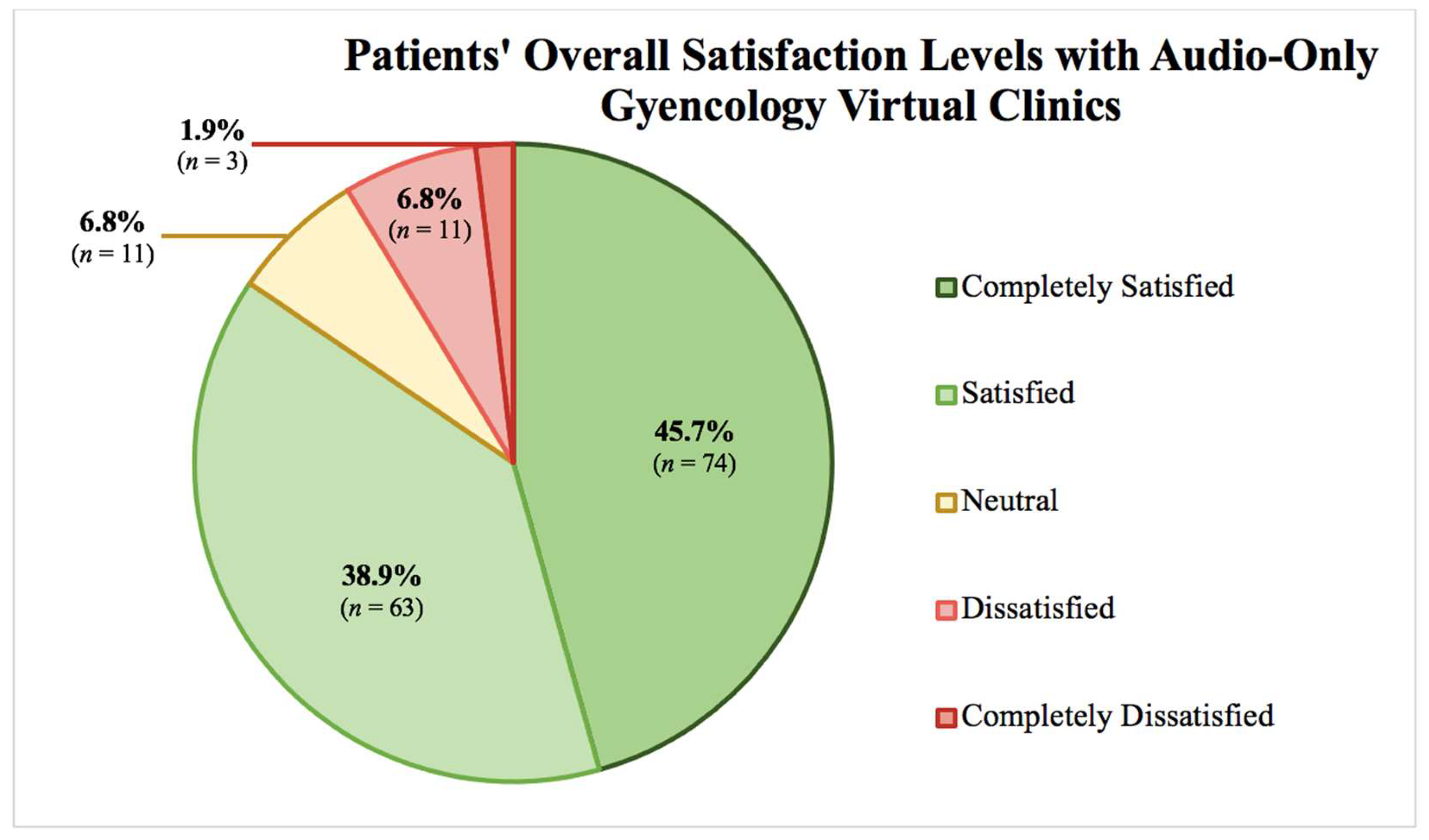

The overall percentage of patients to have reported overall complete satisfaction with the gynecology virtual clinics was 84.6%, as shown in

Figure 2. Age, educational level, residence, transportation mode, missed days of work, visit type, and number of virtual visits all failed to show any statistical significance to satisfaction level. Patients’ experiences, perceptions, and satisfaction with audio-only gynecology clinics are outlined in

Table 3. Patients who reported to have been called at the registered appointment time were more likely to report higher satisfaction, with statistical significance of p = 0.013. Beliefs that the availability of gynecology virtual clinics in the Saudi healthcare system is important and that virtual clinics are an acceptable way to receive healthcare services also showed statistically significant associations with satisfaction levels, p < 0.001. Moreover, patients who felt that they can easily talk to their physicians in virtual clinics, that physicians are keen to hear all concerns during virtual clinics, that all their questions were answered, and that physicians clearly explained all required examinations and follow-up plans during virtual clinics reported statistically significant satisfaction rates, p < 0.001. Patients who found audio-only virtual visits’ time lengths suitable and who were requested to come personally to the healthcare center for further examination also reported statistically significant satisfaction rates, p = 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively. Moreover, those who found that virtual clinics saved transportation and waiting times and made it easy to attend all appointments, who had similar levels of satisfaction when compared to in-hospital visits, who were happy to use virtual clinics again for the same complaint, and who were satisfied with physicians’ explanation of results and treatment plans, discussion of treatment options, and effect of the treatment and care provided during the virtual clinic all reported statistically significant satisfaction levels when compared to their counterparts, p < 0.001. Lastly, patients’ perception of physicians' respect during virtual clinics was shown to be statistically correlated with significant satisfaction levels, p = 0.043.

4. Discussion

Telemedicine was found to achieve the goals of improving care experience, engagement, and satisfaction, reducing costs and time spent in transportation, and providing health outcomes comparable to the traditional methods without comprising neither the quality of care nor the patient-physician relationship [

4,

6]. Overall, physicians’ desire to continue pursuing, practicing, and offering telemedicine services, such as virtual clinics, has been noted in literature [

16]. The desire to continue telemedicine after the resolution of the pandemic was perceived to be associated with higher satisfaction rates [

6,

16]. Therefore, it is no surprise that telehealth integration into the field of obstetrics and gynecology was shown to be highly accepted and valued by both of the physicians and patients [

7].

In this study, more than half of the physicians (61.1%) reported that they were able to reach the patient from the first call about half the time only, while only 37% expressed that they were usually able to speak directly to the patient. This barrier is probably due to the conservative nature of the Saudi community, in which the spouse’s phone number is in many times the number registered and contacted in many instances. The 38.9% of physicians who expressed to not be able to reach patients from first call might be explained by the unavailability of many patients in morning hours due to being asleep, despite personally reserving morning appointments. This leads to many calls of the virtual clinic to be unanswered. As for physicians, the inability to perform physical examination was the biggest telemedicine drawback reported in multiple studies [

10,

21]. The inability to access patient’s medical records or to perform laboratory tests were also some of the biggest barriers reported in other studies [

11,

21]. Compared to previous studies and unlike our study, physicians reported the inability to perform physical examination, access patient’s medical records, or to perform laboratory tests were the biggest telemedicine drawback reported in multiple studies [

10,

11,

21]. Interestingly, female physicians felt more challenged in regard to their clinical skills when compared to male physicians (71% versus 51%,

p=.002), in a previous study [

22]. However, in our current study, no statistically significant association was noted between gender and any of the other variables.

In this current study, almost half of the physicians (48.1%) found that physical examination was indicated about half the time and that they have seldomly asked the patient to attend physically to the clinic. Despite this noted drawback, these same physicians were noted to be more supportive of the continuation of virtual clinics. This might be explained by an outlook of “benefits outweigh the risks,” due to the positive beliefs the majority seemed to hold, such as that virtual clinics improve healthcare access to patients, are an acceptable way to provide healthcare services, are a convenient method of seeing a larger number of patients in an optimal way, and are an adequate replacement when in-patient visits are difficult. Such positive attitudes toward virtual clinics were previously reported in literature where physicians also believed that telemedicine increased services’ accessibility, improved healthcare quality, and enhanced ease of use for both physicians and patients [

10,

16].

However, despite the many benefits that physicians perceived in the use of telehealth in this current study, only about half of the physicians (55.5%) desired the continuation of virtual visits. This discrepancy is understandable and explainable as previously noted with patients of a previous study, as the integration of telemedicine during the pandemic aims to not fully replace in-person encounters but to simply integrate screening, monitoring, and examination into fewer in-person visits to reduce the risk of COVID-19 exposure to both the patient and physician [

13]. However, in the current study, virtual clinics replaced in-person visits as a whole, except for the cases that required in-person examination. Therefore, the high percentage of physicians who perceived virtual clinics to be beneficial compared to the lower percentage who wished them to continue might be explained by the individual was telehealth is being incorporated in the tertiary hospital of this study and the way virtual clinics are being relied on almost completely to limit from the infection risks of COVID-19. It might be hypothesized that virtual clinics can therefore be better implemented after the pandemic by the incomplete reliance on their conduction, in order to continue reaping the many benefits that physicians agreed upon and to overcome the main reason as to why only half of the physicians wish virtual clinics to continue. Modifications of the conduction of virtual clinics might increase the satisfaction rates to the ones reported in the Republic of Turkey where almost all (99%) physicians were satisfied with telemedicine applications during the pandemic.

In this current study, the overall percentage of patients to have reported overall satisfaction and complete satisfaction with the gynecology virtual clinics was 84.6%, which is comparable to a study conducted in the Republic of Turkey, a country within the Middle East, in which 87% of their patients reported satisfaction [

11]. Unlike another study conducted in Kerachi, the capital of Pakistan and a developing country like Saudi Arabia, which showed that the biggest barriers found in the integration of telemedicine were poverty and lack of education [

22], educational level failed to show any statistically significant correlation to satisfaction level in our current study. As for the difference in the level of satisfaction across age groups toward virtual clinics, a recent study revealed that older patients have become more accepting and satisfied akin to all other age groups nowadays when compared to the results of studies conducted at the start of the pandemic and early integration of telemedicine [

6]. This correlates well with our study, as all age groups showed acceptance and satisfaction.

Similar to a study conducted in the emergency department that revealed patients’ satisfaction remained similar in in-person and virtual visits, 71.8% of the patients in our study reported that the level of satisfaction with virtual clinics is similar to in-hospital visits and seeing physicians in person. Moreover, in the current study, most of the patients (90.9%) felt that their concerns were heard, and 76.0% were happy to use virtual clinics again. Similar to our study’s findings, another study reported that 80% of the patients felt that their concerns were heard and addressed by their provider and wished to continue incorporating virtual clinics into their future care [

6]. A higher percentage of almost all (99%) of the patients who participated in another study focusing on audio-only prenatal virtual clinics reported to have had their needs met [

5]. Patients in the aforementioned study were also noted to attend their prenatal virtual appointments more when compared to in-person prenatal appointments (88% versus 82%,

p<.001). This is analogous to what 85.7% of our patients reported when asked if virtual clinics made attending all appointments easier. Patients’ most significant reported virtual clinic advantages in literature were convenience, saving transportation time, and reduced costs associated with travel from remote areas, missed occupational commitment, and childcare arrangements [

6,

11]. Compared to our study, the highest agreed-upon benefit of virtual clinics is the saved time usually spent in clinics’ waiting rooms followed by the ability to attend all appointments, 86.2% and 85.7%, respectively.

As for the strengths and limitations of this study, the limitations include the study’s cross-sectional design, the relatively small patient sample size, and the possibility of recall bias. However, this study remains to be the first of its kind to investigate physicians’ and patients’ stance toward gynecology virtual clinics in Saudi Arabia. Moreover, the use of both phone calls and physical questionnaires enabled the researchers’ to reach a wider portion of patients.

5. Conclusions

Audio-only gynecology virtual clinics are accepted by both physicians and patients. However, patients’ satisfaction are higher than physicians’, with saving waiting time and the ability of attending all appointments being the biggest benefits reported. Physicians’ positive outlook on virtual clinics but significant reluctance to continue using them suggests the need to modify the conduction of virtual clinics and necessitates larger-scaled prospective studies in this topic.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the research and manuscript. Conceptualization, Asma Khalil, Shahad Alharazi and Farah Bakhamees; Data curation, Asma Khalil, Shahad Alharazi and Farah Bakhamees; Formal analysis, Asma Khalil, Shahad Alharazi and Farah Bakhamees; Investigation, Asma Khalil, Shahad Alharazi and Farah Bakhamees; Methodology, Asma Khalil, Shahad Alharazi and Farah Bakhamees; Supervision, Asma Khalil, Shahad Alharazi and Farah Bakhamees; Writing – original draft, Asma Khalil, Shahad Alharazi and Farah Bakhamees; Writing – review & editing, Asma Khalil, Shahad Alharazi and Farah Bakhamees. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of King Abdullah International Medical Research Center, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia (protocol code NRJ21J-010-01 and date of approval 11/02/2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to sincerely thank Hessa J. AlMalki, Jamilah S. Alahmary, Ebtesam B. Alyehyawi, and Rozan O. AlMdani for their remarkable assistance in the data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200430-sitrep-94-covid-19.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Worldometer. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/impact-of-covid-19-on-people's-livelihoods-their-health-and-our-food-systems (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Implementing Telehealth in Practice. Obstet Gynecol 2020, 135, e73–e79. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holcomb, D.; Faucher, M.; Bouzid, J.; Quint-Bouzid, M.; Nelson, D.; Duryea, E. Patient Perspectives on Audio-Only Virtual Prenatal Visits Amidst the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Pandemic. Obstet Gynecol 2020, 136, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobrusin, A.; Hawa, F.; Gladshteyn, M.; Corsello, P.; Harlen, K.; Walsh, C.; et al. Gastroenterologists and Patients Report High Satisfaction Rates With Telehealth Services During the Novel Coronavirus 2019 Pandemic. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020, 18, 2393–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Sofiani, M.; Alyusuf, E.; Alharthi, S.; Alguwaihes, A.; Al-Khalifah, R.; Alfadda, A. Rapid Implementation of a Diabetes Telemedicine Clinic During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Outbreak: Our Protocol, Experience, and Satisfaction Reports in Saudi Arabia. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2020, 14, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinar, U.; Anract, J.; Perrot, O.; Tabourin, T.; Chartier-Kastler, E.; Parra, J.; Vaessen, C.; de La Taille, A.; Roupret, M. Preliminary Assessment of Patient and Physician Satisfaction With the Use of Teleconsultation in Urology During the COVID-19 Pandemic. World J Urol 2020, 38, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, H.; Greenwald, P.W.; Clark, S.; Gogia, K.; Laghezza, M.R.; Hafeez, B.; Sharma, R. Telemedicine Evaluations for Low-Acuity Patients Presenting to the Emergency Department: Implications for Safety and Patient Satisfaction. Telemed J E Health 2020, 26, 1010–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, R.A.; England, B.R.; Mastarone, G.; Richards, J.S.; Chang, E.; Wood, P.R.; Barton, J.L. Rheumatology Clinicians' Perceptions of Telerheumatology Within the Veterans Health Administration: A National Survey Study. Mil Med 2020, 185, 734–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydemir, S.; Ocak, S.; Saygl, S.; Hopurcuolu, D.; Halak, F.; Kykm, E.; Aktulu Zeybek, Ç.; Celkan, T.; Demirgan, E.B.; Kasapçopur, Ö.; Çokura, H.; Kykm, A.; Canpolat, N. Telemedicine Applications in a Tertiary Pediatric Hospital in Turkey During COVID-19 Pandemic. Telemed J E Health 2020, 26, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler Tobah, Y.; LeBlanc, A.; Branda, M.; Inselman, J.; Morris, M.; Ridgeway, J.; et al. Randomized Comparison of a Reduced-Visit Prenatal Care Model Enhanced With Remote Monitoring. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019, 221, 638.e1–638.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziz, A.; Zork, N.; Aubey, J.; Baptiste, C.; D'Alton, M.; Emeruwa, U.; et al. Telehealth for High-Risk Pregnancies in the Setting of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am J Perinatol 2020, 37, 800–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Hitt, W. Clinical Applications of Telemedicine in Gynecology and Women’s Health. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2020, 47, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kern-Goldberger, A.; Srinivas, S. Telemedicine in Obstetrics. Clin Perinatol 2020, 47, 743–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miner, H.; Fatehi, A.; Ring, D.; Reichenberg, J.S. Clinician Telemedicine Perceptions During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Telemed J E Health 2020, 26, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Huidobro, D.; Rivera, S.; Valderrama Chang, S.; Bravo, P.; Capurro, D. System-Wide Accelerated Implementation of Telemedicine in Response to COVID-19: Mixed Methods Evaluation. J Med Internet Res 2020, 22, e22146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeNicola, N.; Grossman, D.; Marko, K.; Sonalkar, S.; Butler Tobah, Y.; Ganju, N.; et al. Telehealth Interventions to Improve Obstetric and Gynecologic Health Outcomes. Obstet Gynecol 2020, 135, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawthorne, G.; Sansoni, J.; Hayes, L.; Marosszeky, N.; Sansoni, E. Measuring Patient Satisfaction With Health Care Treatment Using the Short Assessment of Patient Satisfaction Measure Delivered Superior and Robust Satisfaction Estimates. J Clin Epidemiol 2014, 67, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhandari, N.; Payakachat, N.; Fletcher, D.; Sung, Y.; Eswaran, H.; Benton, T.; et al. Validation of Newly Developed Surveys to Evaluate Patients' and Providers' Satisfaction With Telehealth Obstetric Services. Telemed e-Health 2020, 26, 879–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elawady, A.; Khalil, A.; Assaf, O.; Toure, S.; Cassidy, C. Telemedicine During COVID-19: A Survey of Health Care Professionals' Perceptions. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 2020, 90, 4–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashfaq, A.; Memon, S.; Zehra, A.; Barry, S.; Jawed, H.; Akhtar, M.; et al. Knowledge and Attitude Regarding Telemedicine Among Doctors in Karachi. Cureus 2020, 12, e8345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).