Submitted:

06 November 2024

Posted:

06 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

Preparation of Live Microbial Inocula for Infection

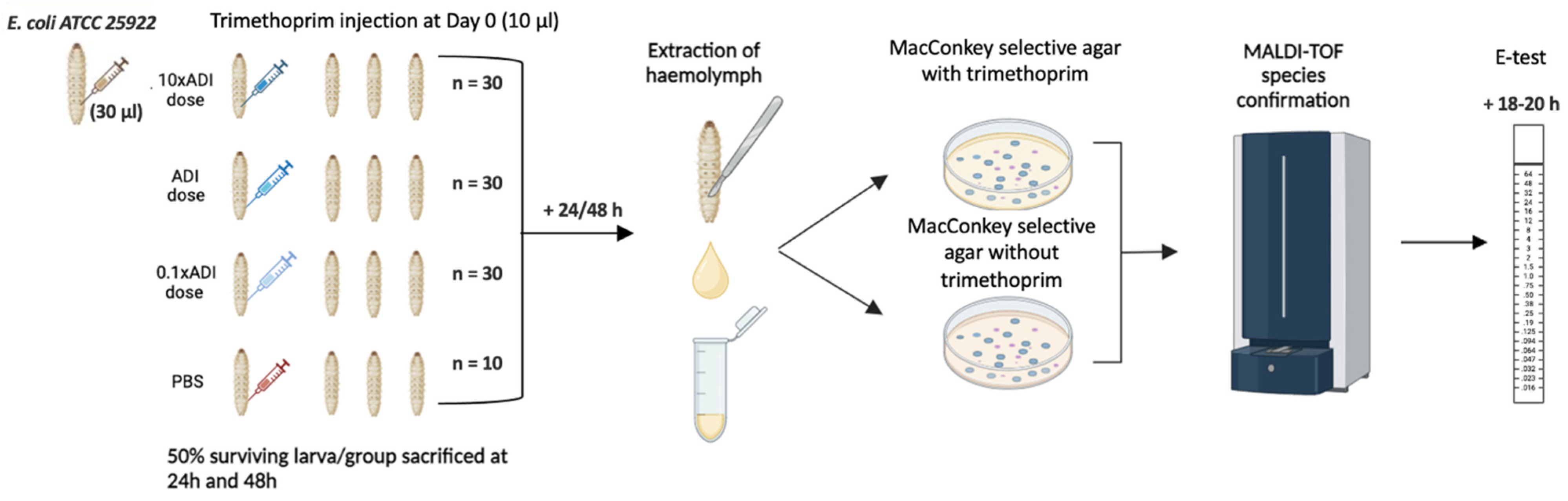

Injection of G. mellonella Larvae

Concentration of Trimethoprim Injected

Retrieval of E. coli from G. mellonella

MALDI-TOF MS Species Identification

Results

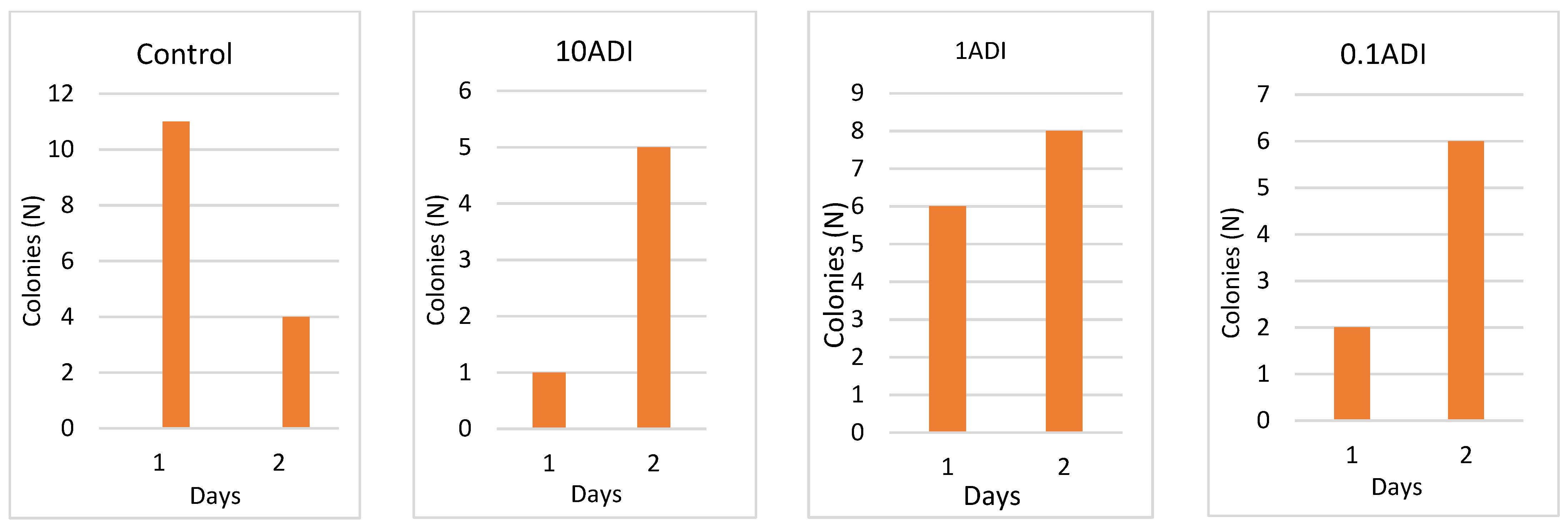

Colonization

Colony Emergence and Identification

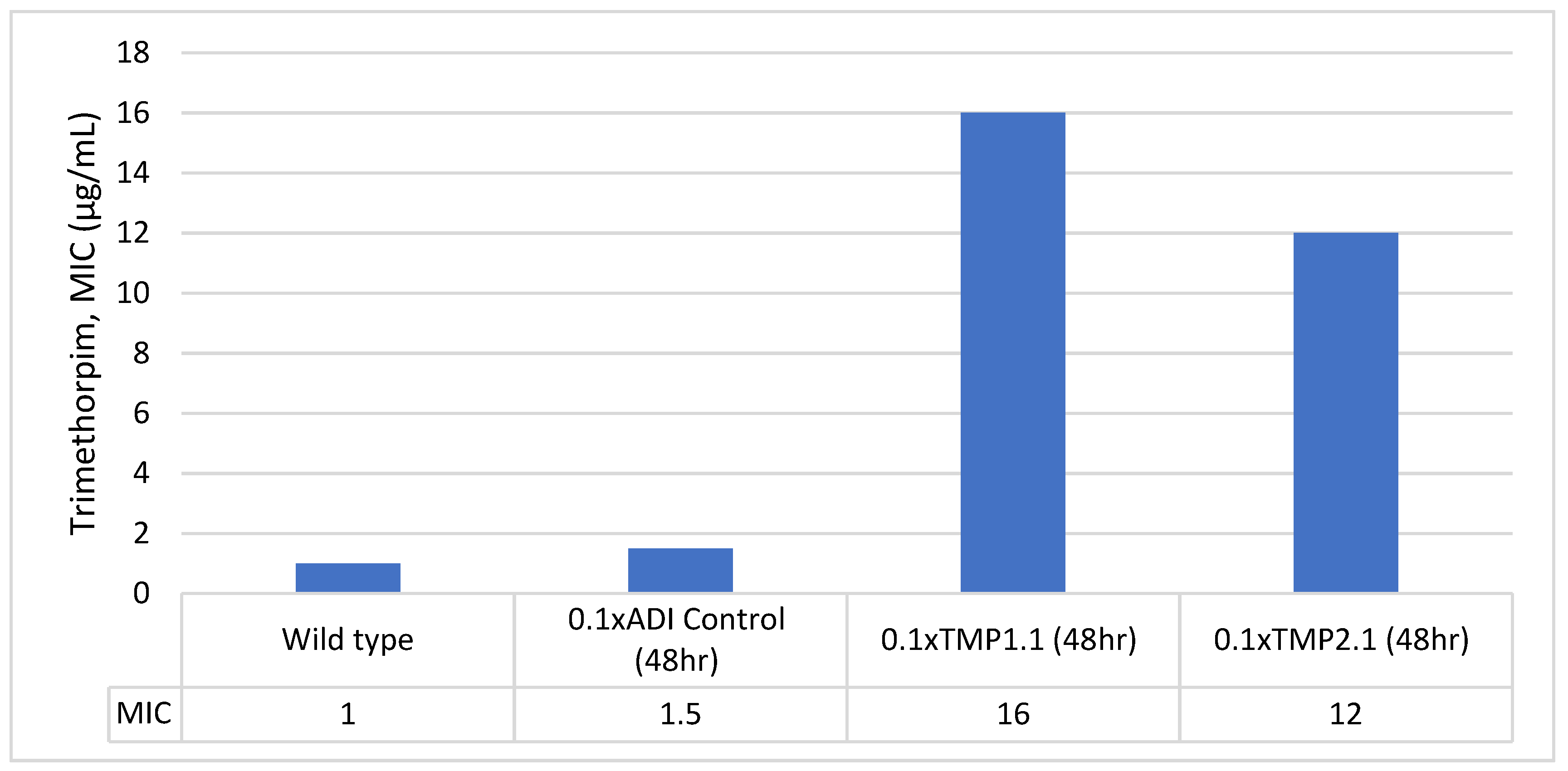

Stability of Trimethoprim-Resistant Isolates

Discussion

Authors’ contributions:

Competing interests

References

- Gullberg, E., et al., Selection of a multidrug resistance plasmid by sublethal levels of antibiotics and heavy metals. mBio, 2014. 5(5): p. e01918-14. [CrossRef]

- Hjort, K., et al., Antibiotic Minimal Selective Concentrations and Fitness Costs during Biofilm and Planktonic Growth. mBio, 2022. 13(3): p. e0144722. [CrossRef]

- Gestels, Z., et al., Ciprofloxacin Concentrations 100-Fold Lower than the MIC Can Select for Ciprofloxacin Resistance in Neisseria subflava: An In Vitro Study. Antibiotics, 2024. 13(6): p. 560.

- Gullberg, E., et al., Selection of Resistant Bacteria at Very Low Antibiotic Concentrations. PLOS Pathogens, 2011. 7(7): p. e1002158. [CrossRef]

- González, N., et al., Ciprofloxacin Concentrations 1/1000th the MIC Can Select for Antimicrobial Resistance in N. gonorrhoeae-Important Implications for Maximum Residue Limits in Food. Antibiotics (Basel), 2022. 11(10). [CrossRef]

- Kraupner, N., et al., Selective concentrations for trimethoprim resistance in aquatic environments. Environment International, 2020. 144: p. 106083. [CrossRef]

- Stanton, I.C., et al., Evolution of antibiotic resistance at low antibiotic concentrations including selection below the minimal selective concentration. Communications Biology, 2020. 3(1): p. 467. [CrossRef]

- Baranchyk, Y., et al., Effect of erythromycin residuals in food on the development of resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae: an in vivo study in Galleria mellonella. PeerJ, 2024. 12: p. e17463. [CrossRef]

- Wu-Wu, J.W.F., et al., Antibiotic resistance and food safety: perspectives on new technologies and molecules for microbial control in the food industry. Antibiotics, 2023. 12(3): p. 550.

- FAO/WHO, Codex Alimentarius: Guidelines for the simple evaluation of dietary exposure to food additives. CAC/GL 3-1989 Adopted 1989. Revision 2014. 2014.

- Gestels, Z., et al., Could traces of fluoroquinolones in food induce ciprofloxacin resistance in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae? An in vivo study in Galleria mellonella with important implications for maximum residue limits in food. Microbiology Spectrum, 2024: p. e03595-23.

- Van Boeckel, T.P., et al., Global antibiotic consumption 2000 to 2010: an analysis of national pharmaceutical sales data. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 2014. 14(8): p. 742-750. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faleye, A.C., et al., Concentration and reduction of antibiotic residues in selected wastewater treatment plants and receiving waterbodies in Durban, South Africa. Science of The Total Environment, 2019. 678: p. 10-20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flach, C.-F., et al., A Comprehensive Screening of Escherichia coli Isolates from Scandinavia’s Largest Sewage Treatment Plant Indicates No Selection for Antibiotic Resistance. Environmental Science & Technology, 2018. 52(19): p. 11419-11428. [CrossRef]

- Khan, G.A., et al., Occurrence and Abundance of Antibiotics and Resistance Genes in Rivers, Canal and near Drug Formulation Facilities – A Study in Pakistan. PLOS ONE, 2013. 8(6): p. e62712. [CrossRef]

- Seo, J., et al. Antibiotic Residues in UK Foods: Exploring the Exposure Pathways and Associated Health Risks. Toxics, 2024. 12, DOI: 10.3390/toxics12030174.

- The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products, COMMITTEE FOR VETERINARY MEDICINAL PRODUCTS: ENROFLOXACIN SUMMARY REPORT (5). 2002.

- Murray, A.K., et al., Dawning of a new ERA: Environmental Risk Assessment of antibiotics and their potential to select for antimicrobial resistance. Water Res, 2021. 200: p. 117233. [CrossRef]

- FAO/WHO. Codex Alimentarius Commission (CAC): Maximum Residue Limits. Available from: http://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/codex-texts/maximum-residue-limits/en/.

- Elder, H., et al., Human studies to measure the effect of antibiotic residues. Veterinary and human toxicology, 1993. 35: p. 31-36.

- European Food Safety Authority, The European Union Summary Report on Antimicrobial Resistance in zoonotic and indicator bacteria from humans, animals and food in 2018/2019. EFSA Journal, 2021. 19(4).

- Mitchell, J., et al., Antimicrobial drug residues in milk and meat: causes, concerns, prevalence, regulations, tests, and test performance. Journal of food protection, 1998. 61(6): p. 742-756. [CrossRef]

- ATCC. Escherichia coli (Migula) Castellani and Chalmers 25922 ™. FDA strain Seattle 1946 [DSM 1103, NCIB 12210]]. Available from: https://www.atcc.org/products/25922#detailed-product-information.

- Gu, B., et al., Comparison of the prevalence and changing resistance to nalidixic acid and ciprofloxacin of Shigella between Europe–America and Asia–Africa from 1998 to 2009. International journal of antimicrobial agents, 2012. 40(1): p. 9-17. [CrossRef]

- Agency, T.E.M., The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products. COMMITTEE FOR VETERINARY MEDICINAL PRODUCTS: TRIMETHOPRIM SUMMARY REPORT (2).

- Gleckman, R., N. Blagg, and D.W. Joubert, Trimethoprim: Mechanisms of Action, Antimicrobial Activity, Bacterial Resistance, Pharmacokinetics, Adverse Reactions, and Therapeutic Indications. Pharmacotherapy: The Journal of Human Pharmacology and Drug Therapy, 1981. 1(1): p. 14-19. [CrossRef]

- Papich, M.G., Saunders Handbook of Veterinary Drugs. Fourth Edition ed. 2016.

- Poirel, L., et al., Antimicrobial Resistance in Escherichia coli. Microbiology Spectrum, 2018. 6(4): p. 10.1128/microbiolspec.arba-0026-2017. [CrossRef]

- Minogue, T.D., et al., Complete Genome Assembly of Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, a Serotype O6 Reference Strain. Genome Announc, 2014. 2(5). [CrossRef]

- ATCC. Escherichia coli (Migula) Castellani and Chalmers 25922 ™. FDA strain Seattle 1946 [DSM 1103, NCIB 12210]]. Available from: https://www.atcc.org/products/25922#detailed-product-information. [CrossRef]

- Calarga, A.P., et al., Antimicrobial resistance and genetic background of non-typhoidal Salmonella enterica strains isolated from human infections in São Paulo, Brazil (2000–2019). Brazilian Journal of Microbiology, 2022. 53(3): p. 1249-1262. [CrossRef]

- Sivertsen, A., et al., Escherichia marmotae-a Human Pathogen Easily Misidentified as Escherichia coli. Microbiol Spectr, 2022. 10(2): p. e0203521. [CrossRef]

- Manna, M.S., et al., A trimethoprim derivative impedes antibiotic resistance evolution. Nature Communications, 2021. 12(1): p. 2949. [CrossRef]

- Brolund, A., et al., Molecular Characterisation of Trimethoprim Resistance in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae during a Two Year Intervention on Trimethoprim Use. PLOS ONE, 2010. 5(2): p. e9233. [CrossRef]

- Baba, T., et al., Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol Syst Biol, 2006. 2: p. 2006.0008. [CrossRef]

- Shi, H., et al., MgrB Inactivation Confers Trimethoprim Resistance in Escherichia coli. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2021. 12. [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.R. and J.M. Calvo, Nucleotide sequence of dihydrofolate reductase genes from trimethoprim-resistant mutants of Escherichia coli. Evidence that dihydrofolate reductase interacts with another essential gene product. Mol Gen Genet, 1982. 187(1): p. 72-8. [CrossRef]

- Flensburg, J. and O. Sköld, Regulatory changes in the formation of chromosomal dihydrofolate reductase causing resistance to trimethoprim. J Bacteriol, 1984. 159(1): p. 184-90. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flensburg, J. and O. Sköld, Massive overproduction of dihydrofolate reductase in bacteria as a response to the use of trimethoprim. Eur J Biochem, 1987. 162(3): p. 473-6. [CrossRef]

- Sangurdekar, D.P., Z. Zhang, and A.B. Khodursky, The association of DNA damage response and nucleotide level modulation with the antibacterial mechanism of the anti-folate drug trimethoprim. BMC Genomics, 2011. 12: p. 583. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitosch, K., G. Rieckh, and T. Bollenbach, Noisy Response to Antibiotic Stress Predicts Subsequent Single-Cell Survival in an Acidic Environment. Cell Syst, 2017. 4(4): p. 393-403.e5. [CrossRef]

- Bhosle, A., et al., A Strategic Target Rescues Trimethoprim Sensitivity in Escherichia coli. iScience, 2020. 23(4): p. 100986. [CrossRef]

- Drlica, K., The mutant selection window and antimicrobial resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2003. 52(1): p. 11-7. [CrossRef]

- Andersson, D.I. and D. Hughes, Antibiotic resistance and its cost: is it possible to reverse resistance? Nat Rev Microbiol, 2010. 8(4): p. 260-71. [CrossRef]

- Kowalska-Krochmal, B. and R. Dudek-Wicher, The Minimum Inhibitory Concentration of Antibiotics: Methods, Interpretation, Clinical Relevance. Pathogens, 2021. 10(2). [CrossRef]

- Laumen, J.G.E., et al., Antimicrobial susceptibility of commensal Neisseria in a general population and men who have sex with men in Belgium. Sci Rep, 2022. 12(1): p. 9.

- Gaulke, C.A., et al., Ecophylogenetics Clarifies the Evolutionary Association between Mammals and Their Gut Microbiota. mBio, 2018. 9(5).

- Seiler, C. and T.U. Berendonk, Heavy metal driven co-selection of antibiotic resistance in soil and water bodies impacted by agriculture and aquaculture. Front Microbiol, 2012. 3: p. 399.

- Kenyon, C., et al., Doxycycline PEP can induce doxycycline resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Galleria mellonella model of PEP. Front Microbiol, 2023. 14: p. 1208014.

| Sample ID (MacConkey) | Phenotype | Detected species | MALDI-TOF Confidence Score | MIC (µg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10x-24hr-TMP4.1 | Pink | Escherichia coli | 2.46 | 8 |

| 1x-24hr-TMP1.1 | Pink | Escherichia coli | 2.07 | 1.5 |

| 1x-24hr-TMP2.1 | Pink | Escherichia coli | 2.01 | 1 |

| 1x-24hr-TMP3.1 | Pink | Escherichia coli | 2.2 | 1.5 |

| 0.1x-24hr-TMP1.1 | Pink | Escherichia coli | 2.01 | 1.5 |

| 10x-48hr-TMP1.1 | Pink | Escherichia marmotae | 1.71 | 1.5 |

| 10x-48hr-TMP1.2 | Pink | Escherichia coli | 1.8 | 1.5 |

| 10x-48hr-TMP2.1 | Pink | Escherichia coli | 2.21 | 1.5 |

| 1x-48hr-TMP1.1 | Pink | Escherichia coli | 1.8 | 1.5 |

| 1x-48hr-TMP2.1 | Pink | Escherichia coli | 2.02 | 1.5 |

| 0.1x-48hr-TMP1.1 | Pink | Escherichia coli | 1.92 | 16 |

| 0.1x-48hr-TMP1.2 | Pink | Escherichia coli | 1.91 | 1 |

| 0.1x-48hr-TMP1.3 | Pink | Escherichia coli | 2.09 | 1.5 |

| 0.1x-48hr-TMP2.1 | Pink | Escherichia coli | 1.92 | 12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).