Submitted:

05 November 2024

Posted:

07 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Preliminaries

Methods

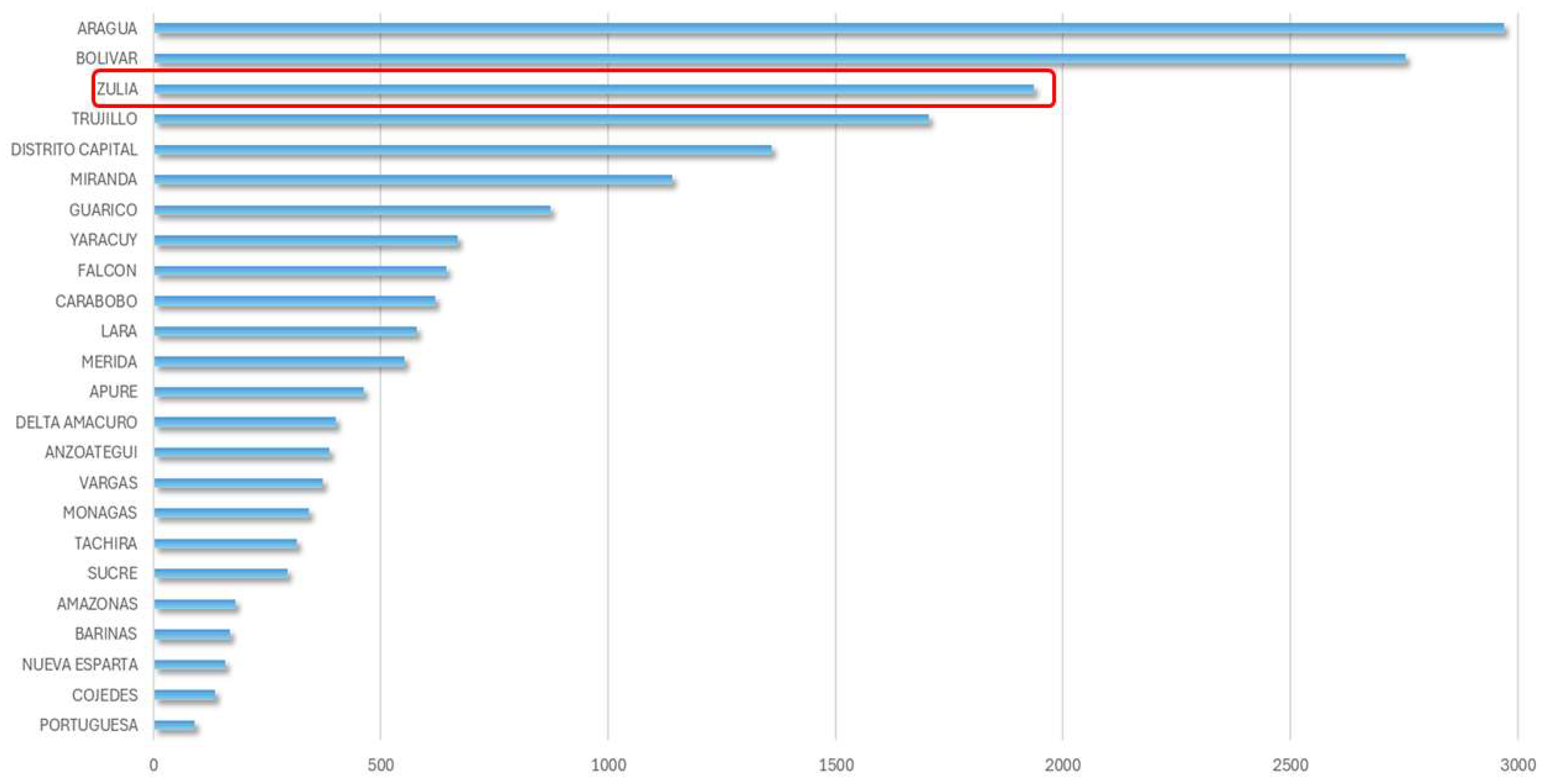

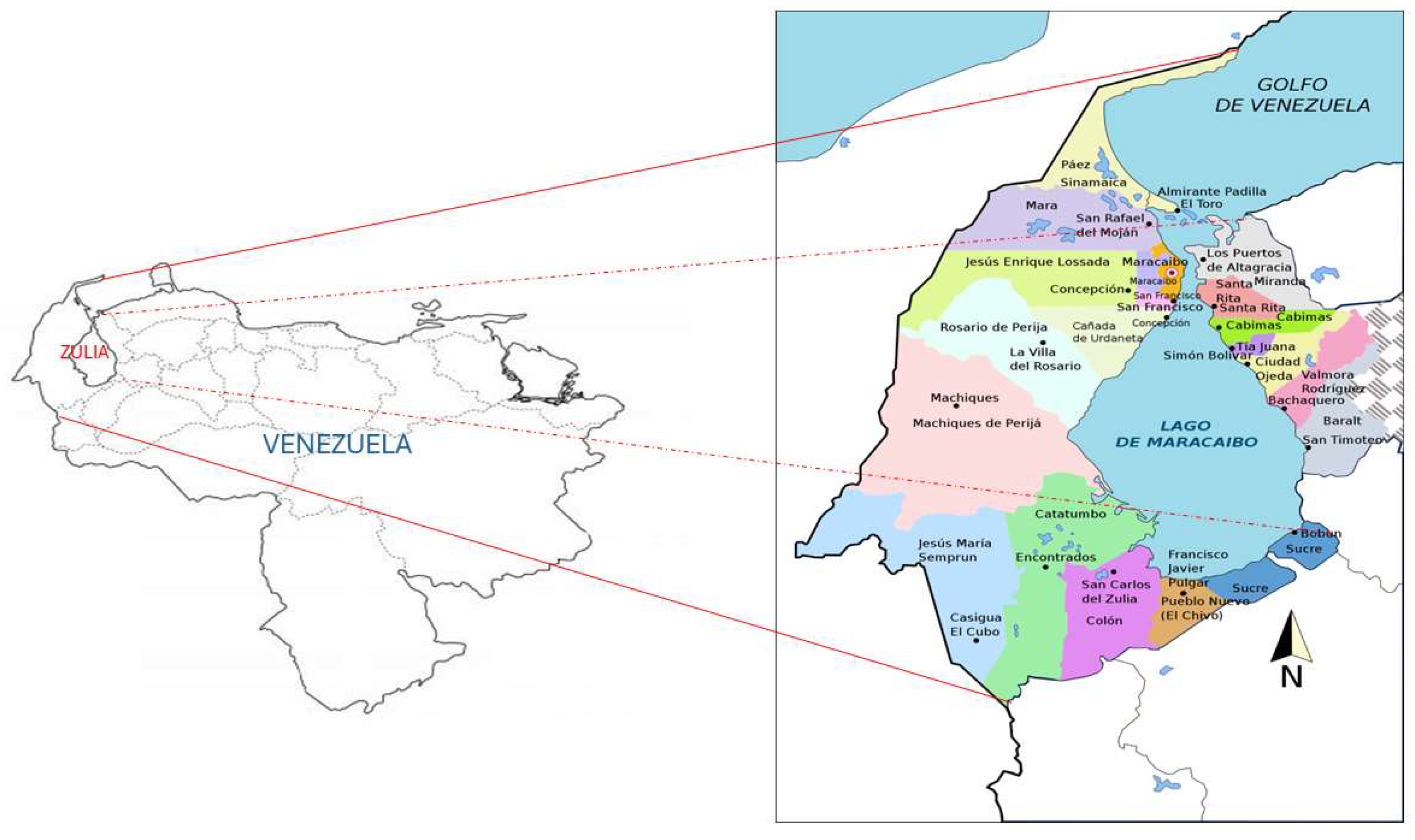

Study Area

Data Integration

Epidemiological Data

Climate and Weather Data

- Temperature at 2 Meters Maximum (°C)

- Temperature at 2 Meters Minimum (°C)

- Specific Humidity at 2 Meters (g/kg)

- Relative Humidity at 2 Meters (%)

- Precipitation Corrected (mm/day)

- Wind Speed at 2 Meters (m/s)

- Wind Speed at 2 Meters Maximum (m/s)

Socio-Economic and Demographic data

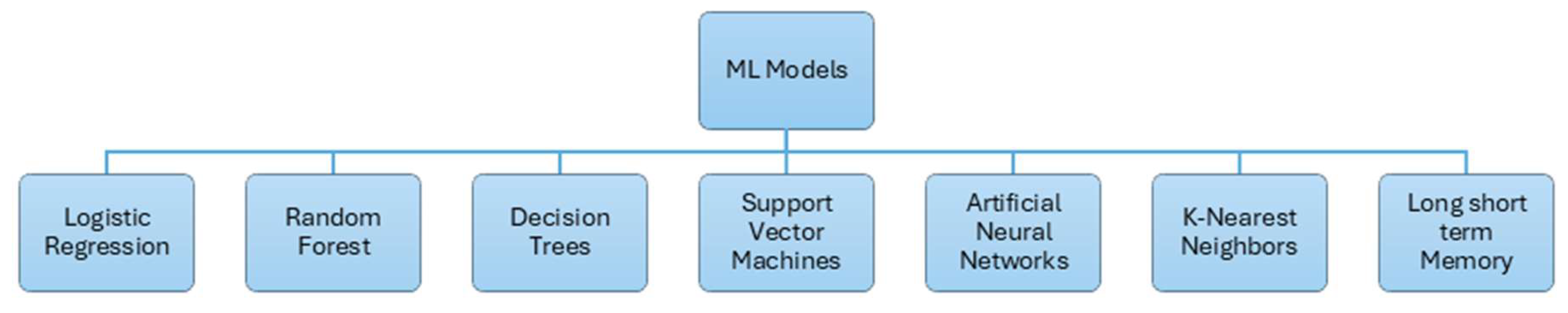

Machine Learning Algorithms

Support Vector Machine (SVM):

Gaussian Process Regression

- ○

- ,

- ○

- : are a set of basis functions that transform the original feature vector into a new feature vector .

- ○

- : is a p-by-1 vector of basis function coefficients.

- Weekly epidemiological data of dengue cases in Zulia state were aggregated at the municipal level in conjunction with a set of climatic and non-climatic covariants. In this context it was necessary to integrate the existing data because of the different sources of information (as proposed Cabrera M & Taylor G. [6]). The present study also utilised remote satellite climatic data obtained from NASA as described previously.

- Epidemiological data was missing for Guajira municipality between 2013 to 2016, which resulted in this municipality being excluded from the study.

- Some demographic data, such as 2008 and 2016, had 53 weeks due to the day the new year started, whilst the climatic data was always divided into 52 weeks. This was dealt with straightforwardly by repeating the previous week´s climatic data for the 53rd week where this occurred. The Niño 3.4 index was aggregated at a weekly level to be consistent with the other data.

- According to some authors [15], the data can be sensitive to extreme values. Therefore, in some cases, it is convenient to normalize or standardize the data. In this study, raw, standardized, and normalized data were used for each model to be trained. In this way, choose the best model obtained. In Standardization: the software centers and scales each column of the predictor data according to the mean and standard deviation of the column. In Normalization: it scales each column of the predictor data between -1 and 1.

- ○

- Covariance function parameterized in terms of kernel parameters in vector θ

- ○

- Noise variance

- ○

- Coefficient vector of fixed-basis functions β

- ○

- The regularization parameter C and

- ○

- The error sensitivity parameter ϵ.

Results

GPR outcomes

SVR outcomes

Discussion

Conclusions

Author Contributions

- Maritza Cabrera.: Conceptualization, investigation, methodology, Writing – review & editing, supervision, Data curation, Formal analysis.

- José Naranjo-Torres.: investigation, methodology, Writing – review & editing, supervision, Software, Formal analysis.

- Ángel Cabrera: Formal analysis.

- Lysien Zambrano: Writing – review & editing, supervision, Software, Formal analysis.

- Alfonso J. Rodríguez-Morales: Writing – review & editing, supervision, Software, Formal analysis.

Funding

References

- Messina, J.P.; Brady, O.J.; Golding, N.; Kraemer, M.U.G.; Wint, G.R.W.; Ray, S.E.; Pigott, D.M.; Shearer, F.M.; Johnson, K.; Earl, L.; et al. The Current and Future Global Distribution and Population at Risk of Dengue. Nat Microbiol 2019, 4, 1508–1515. [CrossRef]

- Allan, R.; Budge, S.; Sauskojus, H. What Sounds like Aedes, Acts like Aedes, but Is Not Aedes? Lessons from Dengue Virus Control for the Management of Invasive Anopheles. The Lancet Global Health 2023, 11, e165–e169. [CrossRef]

- Raviglione, M.; Maher, D. Ending Infectious Diseases in the Era of the Sustainable Development Goals. Porto Biomedical Journal 2017, 2, 140–142. [CrossRef]

- Vincenti-Gonzalez, M.F.; Tami, A.; Lizarazo, E.F.; Grillet, M.E. ENSO-Driven Climate Variability Promotes Periodic Major Outbreaks of Dengue in Venezuela. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 5727. [CrossRef]

- Grillet, M.E.; Hernández-Villena, J.V.; Llewellyn, M.S.; Paniz-Mondolfi, A.E.; Tami, A.; Vincenti-Gonzalez, M.F.; Marquez, M.; Mogollon-Mendoza, A.C.; Hernandez-Pereira, C.E.; Plaza-Morr, J.D.; et al. Venezuela’s Humanitarian Crisis, Resurgence of Vector-Borne Diseases, and Implications for Spillover in the Region. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2019, 19, e149–e161. [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, M.; Taylor, G. Modelling Spatio-Temporal Data of Dengue Fever Using Generalized Additive Mixed Models. Spatial and Spatio-temporal Epidemiology 2019, 28, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, L.A. PAHO/WHO Data - Venezuela - Dengue Cases | PAHO/WHO Available online: https://www3.paho.org/data/index.php/en/mnu-topics/indicadores-dengue-en/dengue-subnacional-en/576-ven-dengue-casos-en.html (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Kakarla, S.G.; Kondeti, P.K.; Vavilala, H.P.; Boddeda, G.S.B.; Mopuri, R.; Kumaraswamy, S.; Kadiri, M.R.; Mutheneni, S.R. Weather Integrated Multiple Machine Learning Models for Prediction of Dengue Prevalence in India. Int J Biometeorol 2023, 67, 285–297. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Global Strategy for Dengue Prevention and Control 2012-2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2012; ISBN 978-92-4-150403-4.

- Cabrera, M.; Leake, J.; Naranjo-Torres, J.; Valero, N.; Cabrera, J.C.; Rodríguez-Morales, A.J. Dengue Prediction in Latin America Using Machine Learning and the One Health Perspective: A Literature Review. TropicalMed 2022, 7, 322. [CrossRef]

- Barboza, L.A.; Chou-Chen, S.-W.; Vásquez, P.; García, Y.E.; Calvo, J.G.; Hidalgo, H.G.; Sanchez, F. Assessing Dengue Fever Risk in Costa Rica by Using Climate Variables and Machine Learning Techniques. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2023, 17, e0011047. [CrossRef]

- Nalini., C.; R, Shanthakumari.; R, V.Prasanna.; A, Nikilesh.; S.M., N.P. Prediction of Dengue Infection Using Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Computer Communication and Informatics (ICCCI); IEEE: Coimbatore, India, January 25 2022; pp. 1–5.

- Sanchez-Gendriz, I.; Souza, G.F. de; Andrade, I.G.M. de; Neto, A.D.D.; Tavares, A. de M.; Barros, D.M.S.; Morais, A.H.F. de; Galvão-Lima, L.J.; Valentim, R.A. de M. Data-Driven Computational Intelligence Applied to Dengue Outbreak Forecasting: A Case Study at the Scale of the City of Natal, RN-Brazil. Scientific Reports 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Souza, C.; Maia, P.; Stolerman, L.M.; Rolla, V.; Velho, L. Predicting Dengue Outbreaks in Brazil with Manifold Learning on Climate Data. Expert Systems with Applications 2022, 192, 116324. [CrossRef]

- Kesorn, K.; Ongruk, P.; Chompoosri, J.; Phumee, A.; Thavara, U.; Tawatsin, A.; Siriyasatien, P. Morbidity Rate Prediction of Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever (DHF) Using the Support Vector Machine and the Aedes Aegypti Infection Rate in Similar Climates and Geographical Areas. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125049. [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Ye, S. Data Prediction Based on Support Vector Machine (SVM)—Taking Soil Quality Improvement Test Soil Organic Matter as an Example. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 295, 012021. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.; Osborne, M.; Ebden, M.; Reece, S.; Gibson, N.; Aigrain, S. Gaussian Processes for Time-Series Modelling. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A. 2013, 371, 20110550. [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, C.E. Gaussian Processes in Machine Learning. In Advanced Lectures on Machine Learning; Bousquet, O., Von Luxburg, U., Rätsch, G., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2004; Vol. 3176, pp. 63–71 ISBN 978-3-540-23122-6.

- Baker, Q.B.; Faraj, D.; Alguzo, A. Forecasting Dengue Fever Using Machine Learning Regression Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2021 12th International Conference on Information and Communication Systems (ICICS); IEEE, May 2021.

- Guo, P.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, L.; Xiao, J.; Zhang, Q.; Luo, G.; Li, Z.; He, J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Developing a Dengue Forecast Model Using Machine Learning: A Case Study in China. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017, 11, e0005973. [CrossRef]

- Hoyos, W.; Aguilar, J.; Toro, M. Dengue Models Based on Machine Learning Techniques: A Systematic Literature Review. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine 2021, 119, 102157. [CrossRef]

- NASA, E.S. NASA POWER | Prediction Of Worldwide Energy Resources Available online: https://power.larc.nasa.gov/ (accessed on 9 December 2023).

- NOAA, N. Climate Prediction Center - Monitoring & Data: Current Monthly Atmospheric and Sea Surface Temperatures Index Values Available online: https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/data/indices/ (accessed on 9 December 2023).

- Albinati, J.; Meira, W.; Pappa, G.L. An Accurate Gaussian Process-Based Early Warning System for Dengue Fever. In Proceedings of the 2016 5th Brazilian Conference on Intelligent Systems (BRACIS); IEEE: Recife, Brazil, October 2016; pp. 43–48.

- Manogaran, G.; Lopez, D. A Gaussian Process Based Big Data Processing Framework in Cluster Computing Environment. Cluster Comput 2018, 21, 189–204. [CrossRef]

- Arias Velásquez, R.M.; Mejía Lara, J.V. Forecast and Evaluation of COVID-19 Spreading in USA with Reduced-Space Gaussian Process Regression. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 2020, 136, 109924. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.-F.; Dumitrascu, B.; Darnell, G.; Chivers, C.; Draugelis, M.; Li, K.; Engelhardt, B.E. Sparse Multi-Output Gaussian Processes for Online Medical Time Series Prediction. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2020, 20, 152. [CrossRef]

- Ketu, S.; Mishra, P.K. Enhanced Gaussian Process Regression-Based Forecasting Model for COVID-19 Outbreak and Significance of IoT for Its Detection. Appl Intell 2021, 51, 1492–1512. [CrossRef]

- Popa, C.L.; Dobrescu, T.G.; Silvestru, C.-I.; Firulescu, A.-C.; Popescu, C.A.; Cotet, C.E. Pollution and Weather Reports: Using Machine Learning for Combating Pollution in Big Cities. Sensors 2021, 21, 7329. [CrossRef]

- Bassman Oftelie, L.; Rajak, P.; Kalia, R.K.; Nakano, A.; Sha, F.; Sun, J.; Singh, D.J.; Aykol, M.; Huck, P.; Persson, K.; et al. Active Learning for Accelerated Design of Layered Materials. npj Comput Mater 2018, 4, 74. [CrossRef]

- Neal, R.M. Bayesian Learning for Neural Networks; Lecture Notes in Statistics; Springer New York: New York, NY, 1996; Vol. 118; ISBN 978-0-387-94724-2.

- Lubbe, F.; Maritz, J.; Harms, T. Evaluating the Potential of Gaussian Process Regression for Solar Radiation Forecasting: A Case Study. Energies 2020, 13, 5509. [CrossRef]

- Statistics and Machine Learning Toolbox Documentation Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/help/stats/index.html?s_tid=CRUX_lftnav (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Appice, A.; Gel, Y.R.; Iliev, I.; Lyubchich, V.; Malerba, D. A Multi-Stage Machine Learning Approach to Predict Dengue Incidence: A Case Study in Mexico. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 52713–52725. [CrossRef]

- Roa, A.C. Sistema de Salud En Venezuela: ¿un Paciente Sin Remedio? Cad. Saúde Pública 2018, 34. [CrossRef]

| Kernel | Mathematical Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Linear | (Kesorn, K. et al. 2015) | |

| Polynomial | (Kesorn, K. et al. 2015; Mello-Roman, J., et al. 2019) | |

| Radial basis function (RBF) | (Kesorn, K. et al. 2015; Nordin, N. I. et al., 2020). |

| MUNICIPALITY | Lags | RMSE |

|---|---|---|

| Baralt | 2 | 2.94 |

| Cabimas | 3 | 7.13 |

| Colon | 3 | 6.26 |

| Lossada | 2 | 15.35 |

| Mara | 2 | 5.84 |

| Maracaibo | 2 | 35.36 |

| Miranda | 2 | 8.09 |

| Rosario | 2 | 7.80 |

| San Francisco | 3 | 16.20 |

| MUNICIPALITY | Lags | RMSE |

|---|---|---|

| Baralt | 2 | 2.57 |

| Cabimas | 2 | 8.14 |

| Colon | 3 | 9.43 |

| Lagunillas | 2 | 2.38 |

| Mara | 2 | 7.005 |

| Lossada | 3 | 16.12 |

| Miranda | 3 | 4.43 |

| Padilla | 2 | 2.16 |

| Rosario | 2 | 7.23 |

| San Francisco | 2 | 15.85 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).