Submitted:

06 November 2024

Posted:

07 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Loss to follow-up; This is the most significant barrier to successful treatment. Homeless PWID are more likely to be lost to follow-up compared to other groups, resulting in uncertain clinical outcomes.[26]

- Lower clinical cure rates; Including patients lost to follow-up, homeless PWID exhibit significantly lower cure rates (47.2%) compared to housed non-PWID (73.1%).[26]

- Higher readmission rates; Homeless PWID have the highest 30-day readmission rates related to outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) (26.4%) among all groups studied.[26]

- Line tampering; Secondary bacteremia and line tampering are more common among homeless PWID, indicating challenges with maintaining the integrity of intravenous access.[26]

- Engagement in care; While cure rates are similar across groups for patients who remain engaged in care, maintaining this engagement is particularly challenging for homeless PWID.[26]

- Psychosocial factors; Studies suggest that addiction and associated mental health disorders often require additional treatment, complicating adherence to OPAT.[26]

- Lack of a suitable environment’ Many homeless patients lack a home environment suitable for the provision of OPAT, making treatment logistics more difficult.[26]

2. Results

2.1. Scenario Analyses

2.1.1. Scenario 1: Sub-Population: Patients with Kidney Dysfunction

2.1.2. Scenario 2: Sub-Population: PWID and the Homeless Population

2.1.3. Scenario 3: No Hospitalization for Dalbavancin and 100% Hospitalization for Comparators

2.1.4. Scenario 4: Comparator Days of Treatment: 12 Days

3. Discussion

3.1. Limitations

3.1.1. Healthcare-Acquired Bacterial and Viral Infections

3.1.2. Impact of Dalbavancin on Hospitalization

3.1.3. Efficacy and Adverse Events

4. Materials and Methods

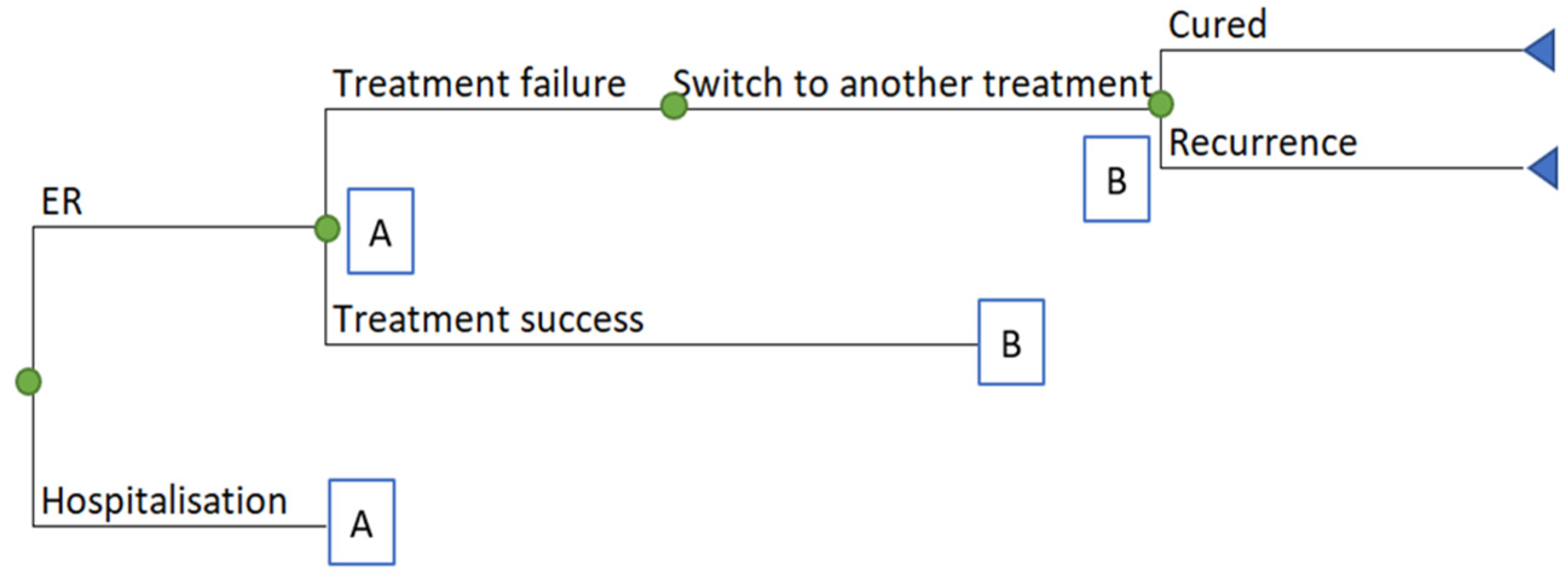

4.1. Model Design

4.2. Additional Model Assumptions

4.3. Treatment Efficacy Parameters

| Parameter | Base Case | SD | Distribution | Source/Assumptions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion with kidney dysfunction | 16.0% | 1.2% | Beta | Lipsky et al, 2012 [53] |

| Rate of clinical failure for patients without kidney dysfunction | 8.6% | 0.8% | Beta | Boucher et al, 2014[46] |

| Rate of clinical failure for patients with kidney dysfunction | 16.8% | 1.7% | Beta | Clinical expert opinion |

| Dalbavancin hospitalization rate | 17.6% | 3.1% | Beta | Talan et al, 2021[63] |

| Other IV hospitalization rate | 37.5% | 3.8% | Beta | Talan et al, 2021[63] |

| Rate of recurrence with IV antibiotics | 16.3% | 0.1% | Beta | May et al. 2017 [19] |

| Increase in recurrence when using oral antibiotics | 24.6% | 2.5% | Beta | Eells et al, 2016[23] |

| Proportion of patients switching to oral antibiotics | 62.0% | 6.2% | Beta | Clinical expert opinion |

| Proportion of patients switching to a q.d. IV | 7.0% | 0.7% | Beta | Clinical expert opinion |

| Dalbavancin treatment cost (1,500 mg) | $2,871.50 | Not varied | Paladin data on file | |

| Vancomycin daily cost without kidney dysfunction (2,000 mg daily) | $37.56 | Not varied | Vancomycin PM [59] and RAMQ « liste des médicaments » [64] | |

| Vancomycin daily cost with kidney dysfunction (850 mg daily) | $15.96 | Not varied | Assumption | |

| Linezolid IV daily cost (1,200 mg daily) | $177.48 | Not varied | Linezolid PM[65] and ODBF[66] | |

| Daptomycin IV cost without kidney dysfunction (456 mg daily, 6 mg/kg or a 76 kg patient) | $148.06 | Not varied | Dose: expert opinion; cost: ODBF[66] | |

| Daptomycin IV cost with kidney dysfunction (456 mg every other day, 6 mg/kg or a 76 kg patient) | $74.03 | Not varied | Assumption: same dosage as without kidney dysfunction but provided every other day instead of daily | |

| Linezolid PO daily cost (1,200 mg daily) | $38.61 | Not varied | Linezolid PM[65] and ODBF[66] | |

| Trimethoprim/salfamethoxazole PO / Trimethoprim PO daily cost (2,400 mg daily) | $0.63 | Not varied | Sulfamethoxazole PM[67] and ODBF[66] | |

| Amoxicillin clavulanic acid PO daily cost (1,750 mg daily) | $1.10 | Not varied | Amoxicillin clavulanic acid PM[68] and ODBF[66] | |

| Clindamycin PO daily cost (1,500 mg daily) | $48.26 | Not varied | Clindamycin PM[69] and ODBF[66] | |

| Cephalexin PO daily cost (2,000 mg daily) | $0.69 | Not varied | Cephalexin PM[70] and ODBF[66] | |

| Cloxacillin PO daily cost (1,500 mg daily) | $1.28 | Not varied | Cloxacillin PM[71] and ODBF[66] | |

| Ertapenem IV daily cost (1,000 mg daily) | $52.27 | Not varied | Ertapenem PM[72] and ODBF[66] | |

| Length of treatment (days) | 14 | 1.4 | Normal | Assumption |

| Hospital cost: 3 days | $7,671.79 | 767.18 | Gamma | CIHI Patient Cost Estimator (2021-2022)[73] |

| Doctor office cost (per visit) | $75.39 | 7.54 | Gamma | RAMQ Manuel Rénumération à l’acte. Médecin spécialiste[64] |

| Catheter (62% utilisation, cost: $36.49) or PICC-line (38% utilisation; cost: $392.99) cost | $171.96 | 17.20 | Gamma | PICC cost: CADTH HTIS[74], catheter cost: RAMQ, Manuel Rémunération à l’acte[64]; distribution: expert opinion |

| Infusion cost (nurse hourly rate) | $42.99 | 4.30 | Gamma | CANSIM 282-0152[75] |

| Infusion times (hours per day) | ||||

| Dalbavancin | 0.50 | Not varied | Dalbavancin PM [45] | |

| Vancomycin IV | 3.33 | Not varied | Vancomycin PM [58] | |

| Linezolid IV | 2.50 | Not varied | Linezolid PM [65] | |

| Daptomycin IV | 0.50 | Not varied | Daptomycin PM [76] | |

| Ertapenem IV | 0.50 | Not varied | Ertapenem PM [72] | |

| Productivity loss cost | ||||

| Employment rate | 61% | Statistics Canada[77] | ||

| Average hourly earnings | $35.35 | Statistics Canada[78] | ||

| Hours lost per days of hospitalisation (8 hours per day 5/7 days) | 5.71 | Assumption | ||

| Utility admitted patients | 0.600 | 0.060 | Gamma | Lipsky 2012[53] |

| Utility discharged patients | 0.800 | 0.080 | Gamma | Lipsky 2012[53] |

| Utility cured | 0.832 | 0.083 | Gamma | Health Quality Council of Alberta 2016[79] |

4.4. Resource Utilisation

4.5. Costs

4.6. Sub-Population and Scenario Analyses

- Patients with kidney dysfunction: The base case includes 16% of patients with kidney dysfunction requiring dose adjustments for vancomycin IV and daptomycin IV. This scenario focuses on this subpopulation.

- PWID, the homeless population, and patients in remote locations: Approximately 893,000 Canadians (2.2% of the total population) are homeless, PWID (many of whom also suffer from psychiatric illness), or both [81,82,83]. This group faces a significantly higher risk of developing ABSSSI, accounting for 30.4% of ABSSSI patients [24,25]. Analysis explored treatment pathways for these three sub-populations, comparing the use of dalbavancin, with discharge probabilities and hospital admission rates maintained the same as in the base case, versus other IV antibiotics, necessitating full-course hospitalization.

- No hospitalization for dalbavancin, 100% hospitalization for comparators (non-severe): Because of its convenient administration as a single-dose treatment, dalbavancin has the potential to reduce the hospital admission rates; however, the exact impact is associated with uncertainty. The other treatments considered in the model are administered daily (e.g., vancomycin IV typically is administered twice (or three times) daily using a 100-minute infusion for a period of treatment of 3 to 14 days, or more). A Canadian clinical expert that was consulted explained that there are situations where an ABSSSI patient requires IV antibiotics but may not need to be hospitalized for additional intervention or observation. If this situation occurs and the patient is being administered dalbavancin, the patient can return home. If the patient is administered any other IV treatment and ambulatory care is not available, hospitalization is required until ambulatory care can be organised, and patients may remain in the emergency room or a corridor because no beds are available. This scenario analyzes the impact of discharging non-severe ABSSSI patients treated with dalbavancin directly from the ED versus hospitalizing those treated with comparators.

- 12-Day comparator treatment: Dalbavancin administered as a single 1500 mg dose was considered equivalent to 14 days of IV vancomycin followed by a possible switch to oral antibiotics based on clinical trials [46,84]. The base case relies on these efficacy data and considered that patients using one of the comparators would be treated for 14 days. This scenario explored a shorter length of antibiotic administration: 12 days.

4.6. HRQoL

5. Conclusions

- Reduced hospitalization time; Dalbavancin’s long half-life allows for a single-dose regimen, significantly reducing hospital stays compared to standard treatments that require multiply daily infusions administered for multiple days. Shorter hospital stays can lead to lower hospitalization costs.

- Lower administration costs; Traditional antibiotics like vancomycin IV require multiple daily infusions administered for multiple days. Dalbavancin’s shorter dosing schedule reduces the need for frequent professional involvement, thereby decreasing labor costs.

- Optimized patient compliance; Dalbavancin’s shorter dosing regimen optimizes patient adherence to the treatment plan, leading to better outcomes and potentially reducing the need for additional treatments or hospital readmissions.

- Cost savings through resource optimization; By decreasing the need for repeated infusions and extended hospital stays, cost savings occur, and healthcare resources can be optimized and reallocated to other critical areas.

- Minimized risk of nosocomial infections; With fewer hospital visits and reduced patient interaction with healthcare environments, the risk of HAIs may be lower. This reduction in HAIs can lead to cost savings associated with treating such infections.

- Quarantine and staffing considerations; Minimizing patient-HCP interactions reduces the risk of virus transmission. This reduction can help maintain a stable workforce by decreasing the number of healthcare workers needing to quarantine, thus avoiding staffing shortages and the associated costs of hiring temporary staff.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- US Department of Health and Human Services; Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Guidance for Industry: Acute Bacterial Skin and Skin Structure Infections: Developing Drugs for treatment. 2013.

- Esposito, S.; Leone, S.; Petta, E.; Noviello, S.; Ianniello, F. Treatment options for skin and soft tissue infections caused by meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: oral vs.parenteral; home vs. hospital. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2009, 34 Suppl 1, S30-35. [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Cejudo, A.; Guzman-Gutierrez, M.; Jalife-Montano, A.; Ortiz-Covarrubias, A.; Martinez-Ordaz, J.L.; Noyola-Villalobos, H.F.; Hurtado-Lopez, L.M. Management of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections with a focus on patients at high risk of treatment failure. Ther Adv Infect Dis 2017, 4, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baibergenova, A.; Drucker, A.M.; Shear, N.H. Hospitalizations for cellulitis in Canada: A database study. J Cutan Med Surg 2014, 18, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soriano, A.; Rossolini, G.M.; Pea, F. The role of dalbavancin in the treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSIs). Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2020, 18, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Concia, E.; Cristini, F.; De Rosa, F.G.; Esposito, S.; Menichetti, F.; Petrosillo, N.; Tumbarello, M.; Venditti, M.; Viale, P.; et al. Current and future trends in antibiotic therapy of acute bacterial skin and skin-structure infections. Clin Microbiol Infect 2016, 22 Suppl 2, S27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuthner, K.D.; Buechler, K.A.; Kogan, D.; Saguros, A.; Lee, H.S. Clinical efficacy of dalbavancin for the treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI). Ther Clin Risk Manag 2016, 12, 931–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potashman, M.H.; Stokes, M.; Liu, J.; Lawrence, R.; Harris, L. Examination of hospital length of stay in Canada among patients with acute bacterial skin and skin structure infection caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Drug Resist 2016, 9, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, D.; Nguyen, H.N.T.; Tyndall, M.; Schreiber, Y.S. Antibiotic use among twelve Canadian First Nations communities: A retrospective chart review of skin and soft tissue infections. BMC Infect Dis 2020, 20, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgundvaag, B.; Ng, W.; Rowe, B.; Katz, K. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in skin and soft tissue infections in patients presenting to Canadian emergency departments. CJEM 2013, 15, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institut national d’excellence en santé et services sociaux. ZYVOXAMMC – Infections à staphylocoques résistants à la méthicilline - Février 2013. 1–6.

- Stevens, D.L.; Bisno, A.L.; Chambers, H.F.; Dellinger, E.P.; Goldstein, E.J.; Gorbach, S.L.; Hirschmann, J.V.; Kaplan, S.L.; Montoya, J.G.; Wade, J.C.; et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2014, 59, e10–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, L.J. Dalbavancin: a review in acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections. Drugs 2015, 75, 1281–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrock, J.W.; Laskey, S.; Cydulka, R.K. Predicting observation unit treatment failures in patients with skin and soft tissue infections. Int J Emerg Med 2008, 1, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, T.L.; Chan, L.; Konopka, C.I.; Burkitt, M.J.; Moffa, M.A.; Bremmer, D.N.; Murillo, M.A.; Watson, C.; Chan-Tompkins, N.H. Appropriateness of antibiotic management of uncomplicated skin and soft tissue infections in hospitalized adult patients. BMC Infect Dis 2016, 16, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, A.; Oster, G.; Edelsberg, J.; Huang, X.; Weber, D.J. Initial treatment failure in patients with complicated skin and skin structure infections. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2013, 14, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nathwani, D.; Dryden, M.; Garau, J. Early clinical assessment of response to treatment of skin and soft-tissue infections: how can it help clinicians? Perspectives from Europe. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2016, 48, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crum-Cianflone, N.; Weekes, J.; Bavaro, M. Recurrent community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections among HIV-infected persons: incidence and risk factors. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2009, 23, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, L.; Klein, E.Y.; Martinez, E.M.; Mojica, N.; Miller, L.G. Incidence and factors associated with emergency department visits for recurrent skin and soft tissue infections in patients in California, 2005-2011. Epidemiol Infect 2017, 145, 746–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, L.S.; Zocchi, M.; Zatorski, C.; Jordan, J.A.; Rothman, R.E.; Ware, C.E.; Eells, S.; Miller, L. Treatment failure outcomes for emergency department patients with skin and soft tissue infections. West J Emerg Med 2015, 16, 642–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.G.; Eells, S.J.; David, M.Z.; Ortiz, N.; Taylor, A.R.; Kumar, N.; Cruz, D.; Boyle-Vavra, S.; Daum, R.S. Staphylococcus aureus skin infection recurrences among household members: an examination of host, behavioral, and pathogen-level predictors. Clin Infect Dis 2015, 60, 753–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreeramoju, P.; Porbandarwalla, N.S.; Arango, J.; Latham, K.; Dent, D.L.; Stewart, R.M.; Patterson, J.E. Recurrent skin and soft tissue infections due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus requiring operative debridement. Am J Surg 2011, 201, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eells, S.J.; Nguyen, M.; Jung, J.; Macias-Gil, R.; May, L.; Miller, L.G. Relationship between adherence to oral antibiotics and postdischarge clinical outcomes among patients hospitalized with staphylococcus aureus skin infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016, 60, 2941–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, G.J.; De Anda, C.; Das, A.F.; Green, S.; Mehra, P.; Prokocimer, P. Efficacy and safety of tedizolid and linezolid for the treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections in injection drug users: Analysis of two clinical trials. Infect Dis Ther 2018, 7, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bork, J.T.; Heil, E.L.; Berry, S.; Lopes, E.; Dave, R.; Gilliam, B.L.; Amoroso, A. Dalbavancin use in vulnerable patients receiving outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy for invasive Gram-positive infections. Infect Dis Ther 2019, 8, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beieler, A.; Magaret, A.; Zhou, Y.; Schleyer, A.; Wald, A.; Dhanireddy, S. Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy in vulnerable populations-- People who inject drugs and the momeless. J Hosp Med 2019, 14, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterveer, T.M.; Young, T.K. Primary health care accessibility challenges in remote indigenous communities in Canada’s North. Int J Circumpolar Health 2015, 74, 29576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Collaborating Centre for Indigineous Health. Social Determinants of Health: ACCESS TO HEALTH SERVICES AS A SOCIAL DETERMINANT OF FIRST NATIONS, INUIT AND MÉTIS HEALTH; 2019.

- Gonzalez, P.L.; Rappo, U.; Mas Casullo, V.; Akinapelli, K.; McGregor, J.S.; Nelson, J.; Nowak, M.; Puttagunta, S.; Dunne, M.W. Safety of dalbavancin in the treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI): Nephrotoxicity rates compared with vancomycin: A post hoc analysis of three clinical trials. Infect Dis Ther 2021, 10, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivagnanam, S.; Deleu, D. Red man syndrome. Crit Care 2003, 7, 119–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martel, T.; Jamil, R.; King, K. Vancomycin Flushing Syndrome. StatPearls [Internet] 2024.

- Martin, J.H.; Norris, R.; Barras, M.; Roberts, J.; Morris, R.; Doogue, M.; Jones, G.R. Therapeutic monitoring of vancomycin in adult patients: A consensus review of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, and the Society Of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Clin Biochem Rev 2010, 31, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Rybak, M.J.; Le, J.; Lodise, T.P.; Levine, D.P.; Bradley, J.S.; Liu, C.; Mueller, B.A.; Pai, M.P.; Wong-Beringer, A.; Rotschafer, J.C.; et al. Therapeutic monitoring of vancomycin for serious methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections: A revised consensus guideline and review by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2020, 77, 835–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Mao, Z.; Yang, M.; Kang, H.; Liu, H.; Pan, L.; Hu, J.; Luo, J.; Zhou, F. Efficacy and safety of daptomycin for skin and soft tissue infections: A systematic review with trial sequential analysis. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2016, 12, 1455–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargese, S.S.; Dev, S.S.; Soman, A.S.; Kurian, N.; Varghese, V.A.; Mathew, E. Exposure risk and COVID-19 infection among frontline health-care workers: A single tertiary care centre experience. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health 2022, 13, 100933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, W.J.; Johnson, E.S.; Fahoury, G.; Monterosa, P. Dalbavancin during the COVID-19 pandemic. Surg Technol Int 2022, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.H.; Drew, D.A.; Joshi, A.D.; Guo, C.G.; Ma, W.; Mehta, R.S.; Sikavi, D.R.; Lo, C.H.; Kwon, S.; Song, M.; et al. Risk of COVID-19 among frontline healthcare workers and the general community: A prospective cohort study. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, K.S.; Patel, D.A.; Stephens, J.M.; Khachatryan, A.; Patel, A.; Johnson, K. Rising United States hospital admissions for acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections: recent trends and economic impact. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0143276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.Y.; Singh, A.; David, M.Z.; Bartsch, S.M.; Slayton, R.B.; Huang, S.S.; Zimmer, S.M.; Potter, M.A.; Macal, C.M.; Lauderdale, D.S.; et al. The economic burden of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA). Clin Microbiol Infect 2013, 19, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostermann, H.; Blasi, F.; Medina, J.; Pascual, E.; McBride, K.; Garau, J. Resource use in patients hospitalized with complicated skin and soft tissue infections in Europe and analysis of vulnerable groups: the REACH study. J Med Econ 2014, 17, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelsberg, J.; Taneja, C.; Zervos, M.; Haque, N.; Moore, C.; Reyes, K.; Spalding, J.; Jiang, J.; Oster, G. Trends in US hospital admissions for skin and soft tissue infections. Emerg Infect Dis 2009, 15, 1516–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsky, B.A.; Weigelt, J.A.; Gupta, V.; Killian, A.; Peng, M.M. Skin, soft tissue, bone, and joint infections in hospitalized patients: epidemiology and microbiological, clinical, and economic outcomes. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2007, 28, 1290–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suaya, J.A.; Mera, R.M.; Cassidy, A.; O’Hara, P.; Amrine-Madsen, H.; Burstin, S.; Miller, L.G. Incidence and cost of hospitalizations associated with Staphylococcus aureus skin and soft tissue infections in the United States from 2001 through 2009. BMC Infect Dis 2014, 14, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itani, K.M.; Merchant, S.; Lin, S.J.; Akhras, K.; Alandete, J.C.; Hatoum, H.T. Outcomes and management costs in patients hospitalized for skin and skin-structure infections. Am J Infect Control 2011, 39, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- XYDALBA® (dalbavancin for injection) Product Monograph. 2021, 1–33.

- Boucher, H.W.; Wilcox, M.; Talbot, G.H.; Puttagunta, S.; Das, A.F.; Dunne, M.W. Once-weekly dalbavancin versus daily conventional therapy for skin infection. N Engl J Med 2014, 370, 2169–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, M.W.; Puttagunta, S.; Giordano, P.; Krievins, D.; Zelasky, M.; Baldassarre, J. A randomized clinical trial of single-dose versus weekly dalbavancin for treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infection. Clin Infect Dis 2016, 62, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhanel, G.; Silverman, M.; Malhotra, J.; Baxter, M.; Rahimi, R.; Irfan, N.; Girouard, G.; Dhami, R.; Kucey, M.; Stankus, V.; et al. Real-life experience with IV dalbavancin in Canada; results from the CLEAR (Canadian LEadership on Antimicrobial Real-life usage) registry. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2024, 38, 154–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Gennaro, F. Prescriptive appropriateness of dalbavancin in acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections in adults: An integrated approach between clinical profile, patient- and health system-related factors and focus on environmental impact. Front Antibiot 2024, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, J.F.; Esteban, J.; Manganelli, A.G.; Novelli, A.; Rizzardini, G.; Serra, M. Comparative efficacy and safety of antibiotics used to treat acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections: Results of a network meta-analysis. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0187792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcellusi, A.; Viti, R.; Sciattella, P.; Sarmati, L.; Streinu-Cercel, A.; Pana, A.; Espin, J.; Horcajada, J.P.; Favato, G.; Andretta, D.; et al. Economic evaluation of the treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSIs) from the national payer perspective: introduction of a new treatment to the patient journey. A simulation of three European countries. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2019, 19, 581–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- All Wales Medicines Strategy Group. Secretariat Assessment Report Dalbavancin (XYDALBA®) 500 mg powder for concentrate for solution for infusion. 1–20.

- Lipsky, B.A.; Moran, G.J.; Napolitano, L.M.; Vo, L.; Nicholson, S.; Kim, M. A prospective, multicenter, observational study of complicated skin and soft tissue infections in hospitalized patients: Clinical characteristics, medical treatment, and outcomes. BMC Infect Dis 2012, 12, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streifel, A.C.; Sikka, M.K.; Bowen, C.D.; Lewis, J.S., 2nd. Dalbavancin use in an academic medical centre and associated cost savings. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2019, 54, 652–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falconer, S. Two years’ experience treating acute bacterial skin and skin-structure infections with dalbavancin in a real-world OPAT setting. P2296 Abstract presented at the 29th ECCMID; Amsterdam, Netherlands; 13–16 April 2019.

- Wilke, M.; Worf, K.; Preisendörfer, B.; Heinlein, W.; Kast, T.; Bodmann, K.F. Potential savings through single-dose intravenous dalbavancin in long-term MRSA infection treatment - a health economic analysis using German DRG data. GMS Infect Dis 2019, 7, Doc03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardakas, K.Z.; Mavros, M.N.; Roussos, N.; Falagas, M.E. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of vancomycin for the treatment of patients with gram-positive infections: Focus on the study design. Mayo Clin Proc 2012, 87, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancomycin hydrochloride for injection USP for intravenous use: Prescribing Information. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/209481s000lbl.pdf (accessed on October 27, 2024).

- Vancomycin hydrochloride for injection USP. (Vancomycin Hydrochloride) 500 mg, 1 g, 5 g and 10 g of vancomycin (as vancomycin hydrochloride) per vial. Sterile lyophilized powder for solution. Product Monograph. 2021, 1–29.

- Coresh, J.; Selvin, E.; Stevens, L.A.; Manzi, J.; Kusek, J.W.; Eggers, P.; Van Lente, F.; Levey, A.S. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA 2007, 298, 2038–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzke, G.R.; Zhanel, G.G.; Guay, D.R. Clinical pharmacokinetics of vancomycin. Clin Pharmacokinet 1986, 11, 257–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhanel, G.; Loeb, M. Consultation on treatment success rates for patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) with reduced dose vacomycin. and 22, 2021. 3 June.

- Talan, D.A.; Mower, W.R.; Lovecchio, F.A.; Rothman, R.E.; Steele, M.T.; Keyloun, K.; Gillard, P.; Copp, R.; Moran, G.J. Pathway with single-dose long-acting intravenous antibiotic reduces emergency department hospitalizations of patients with skin infections. Acad Emerg Med 2021. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Régie de l’assurance maladie du Québec. Manuels et guides de facturation. Available online: https://www.ramq.gouv.qc.ca/fr/professionnels/medecins-specialistes/manuels/Pages/remuneration-acte.aspx (accessed on July 7, 2024).

- Linezolid Injection Product Monograph. 2018.

- Government of Ontario. Ontario Drug Benefit Formulary/Comparative Drug Index. Available online: https://www.formulary.health.gov.on.ca/formulary/ (accessed on Jan 21, 2024).

- Sulfamethoxazole and Trimethoprim Product Monograph. 2018.

- Clavulin Product Monograph. 2020.

- Clindamycin Product Monograph. 2015, 1–28.

- Cephalexin Tablets and Oral Suspensions Product Monograph. 2018.

- Cloxacillin capsules Product Monograph. 2018, 1–13.

- Ertapenem for Injection Product Monograph. 2019.

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Patient Cost Estimator. Available online: https://www.cihi.ca/en/patient-cost-estimator (accessed on July 18, 2024).

- Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; Health Technology Inquiry Service. Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter (PICC) Stabilization Devices: Clinical and Cost-Effectiveness and Guidelines for Use. Available online: https://www.cadth.ca/media/pdf/htis/Peripherally%20Inserted%20Central%20Catheter%20(PICC)%20Stabilization%20Devices%20Clinical%20and%20Cost-Effectiveness.pdf (accessed on day month year).

- Statistics Canada. Employee wages by occupation, annual, inactive. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1410030701&pickMembers%5B0%5D=1.9&pickMembers%5B1%5D=2.2&pickMembers%5B2%5D=3.1&pickMembers%5B3%5D=5.1&pickMembers%5B4%5D=6.1&cubeTimeFrame.startYear=2014&cubeTimeFrame.endYear=2018&referencePeriods=20140101%2C20180101 (accessed on July 7, 2024).

- Cubist, Pharmaceuticals; Inc., S.P.C. Cubist Pharmaceuticals; Inc., S.P.C. Daptomycin for Injection Product Monograph. 2020.

- Statistics Canada. Table 14-10-0287-03 Labour force characteristics by province, monthly, seasonally, adjusted (Ontario) Available online:. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1410028703&pickMembers%5B0%5D=3.1&pickMembers%5B1%5D=4.6&cubeTimeFrame.startMonth=05&cubeTimeFrame.startYear=2021&referencePeriods=20210501%2C20210501 (accessed on July 7, 2024).

- Statistics Canada. Statistics Canada: Average hourly earnings for employees paid by the hour, by industry, annual (Ontario) adjusted to 2021 using the annual growth rate from 2016 to 2020. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1410020601&pickMembers%5B0%5D=1.7&pickMembers%5B1%5D=2.1&cubeTimeFrame.startYear=2016&cubeTimeFrame.endYear=2020&referencePeriods=20160101%2C20200101 (accessed on November 2, 2023).

- Health Quality Council of Alberta. EQ-5D-5L index norms for Alberta population. 2016, 1–8.

- Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) stabilization devices: clinical and cost-effectiveness and guidelines for use. 2008, 1–9.

- The Homelessness Partnering Secretariat (HPS) Canada 2019. Available online: https://www.homelesshub.ca/about-homelessness/homelessness-101/how-many-people-are-homeless-canada (accessed on October 28, 2024).

- Grinman, M.N.; Chiu, S.; Redelmeier, D.A.; Levinson, W.; Kiss, A.; Tolomiczenko, G.; Cowan, L.; Hwang, S.W. Drug problems among homeless individuals in Toronto, Canada: Prevalence, drugs of choice, and relation to health status. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health Canada. Canadian Alcohol and Drug Use Monitoring Survey, 2012. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-concerns/drug-prevention-treatment/drug-alcohol-use-statistics/canadian-alcohol-drug-use-monitoring-survey-summary-results-tables-2012.html (accessed on January 10, 2024).

- Ramdeen, S.; Boucher, H.W. Dalbavancin for the treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2015, 16, 2073–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Dalbavancin | Vancomycin | Linezolid IV | Daptomycin IV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days of hospital saved | ||||

|

Number of days of hospital |

1.7 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 2.5 |

| Costs ($) | ||||

|

Total cost healthcare perspective (without productivity loss) |

7,668 | 7,968 | 8,208 | 8,041 |

|

Total cost societal perspective (with productivity loss) |

7,955 | 8,685 | 8,842 | 8,545 |

| Drug | 2,872 | 284 | 1,164 | 957 |

| Subsequent treatment | 214 | 246 | 247 | 246 |

| Hospitalization | 4,436 | 6,429 | 5,969 | 6,429 |

|

Drug administration (infusion) |

15 | 894 | 722 | 293 |

| Other medical resources | 131 | 115 | 116 | 115 |

| Productivity | 288 | 717 | 634 | 504 |

| QALYs | 0.4467 | 0.4462 | 0.4463 | 0.4462 |

| Comparison | Δ QALY | Δ Costs | Cost/QALY |

|---|---|---|---|

| dalbavancin vs. vancomycin IV | 0.0010 | –2,775 | Dominant |

| dalbavancin vs. linezolid IV | 0.0003 | –541 | Dominant |

| dalbavancin vs daptomycin IV | 0.0010 | –2,551 | Dominant |

| Comparison | Δ QALY | Δ Costs | Cost/QALY |

|---|---|---|---|

| dalbavancin vs. vancomycin IV | 0.0069 | –29,598 | Dominant |

| dalbavancin vs. linezolid IV | 0.0069 | –30,377 | Dominant |

| dalbavancin vs daptomycin IV | 0.0069 | –30,271 | Dominant |

| Comparison | Δ QALY | Δ Costs | Cost/QALY |

|---|---|---|---|

| dalbavancin vs. vancomycin IV | 0.0017 | –6,120 | Dominant |

| dalbavancin vs. linezolid IV | 0.0016 | –6,427 | Dominant |

| dalbavancin vs daptomycin IV | 0.0017 | –6,421 | Dominant |

| Comparison | Δ QALY | Δ Costs | Cost/QALY |

|---|---|---|---|

| dalbavancin vs. vancomycin IV | 0.0004 | –113 | Dominant |

| dalbavancin vs. linezolid IV | 0.0003 | –393 | Dominant |

| dalbavancin vs daptomycin IV | 0.0004 | –187 | Dominant |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).