1. Introduction

Powerlifting is an Olympic and Paralympic sport that involves weightlifting in exercises such as bench press, deadlift, and free squat, using the heaviest load possible within proper technique. Consequently, training in this sport typically involves heavy loads and high training intensity. High loads tend to cause an increase in muscle micro injuries [

1,

2], which increases the athlete's recovery time between training sessions and affects the initially planned volume. This type of impairment is not desired when it comes to achieving high performance [

3]. In fact, an athlete that preserve and enhance performance while minimizing the risk of musculoskeletal injuries, it is essential for athletes to recover adequately between training sessions [

4]. This context, requires that we create after workout strategies to accelerate the recovery, aiming to keep all training planned [

2,

5].

Thus, some methods are investigated aiming accelerated the post-training recovery, including the use of drugs [

6], supplements [

7], CWI and dry needling [

2]. Among these methods, CWI stands out, although it remains a subject of controversy, particularly in Paralympic powerlifting [

2,

8,

9]. Recently, two meta-analyses showed that CWI may have a moderate effect on reducing muscle damage and pain [

10,

11], however, other meta-analyses have indicated that CWI may have a detrimental effect on the athlete [

12,

13]. Grgic [

12] recommends caution when using CWI, where exposure time and temperature must be individualized. Specifically in Paralympic powerlifting, this practice has been little tested, mainly due to the difficulty in immersing athletes in water [

2]. Given these considerations, the present study aims to assess the effects of different post-training recovery methods on muscle damage in Paralympic powerlifting athletes. In doing so, we hypothesize that CWI is likely to improve post-training muscle recovery and reduce pro-inflammatory blood immune markers while increasing anti-inflammatory ones

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

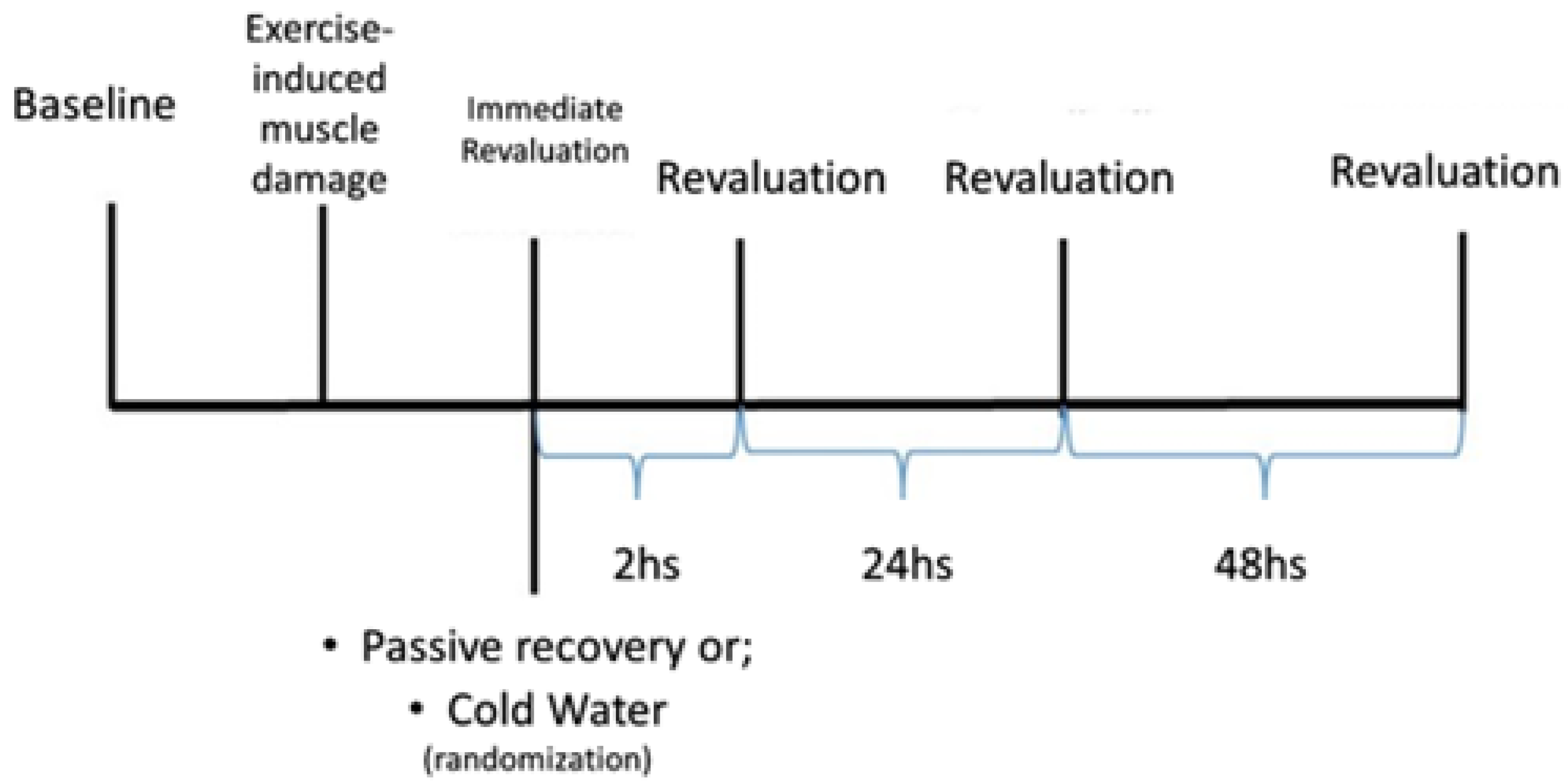

The study was conducted over three weeks, with the first week dedicated to familiarizing the subjects with the tests, and the subsequent weeks were allocated to the evaluation using different recovery methods: PR and CWI. The choice of recovery method was determined by random selection, with half of the sample assigned to each week, until all subjects had completed all the methods, as depicted in

Figure 1.

2.2. Participants

This is a cross-over study that included 11 Paralympic Powerlifting athletes (27.1±4.7 yrs.; 84.6±18.5 kg; 3.2±0.5 yrs. of experience; 150.2±27.5 kg in 1RM bench press; 1.8±0.2 1RM/BW). All subjects were national-level competitors, with some also competing at the international level (all athletes performed ≥1.4 1RM/BW; limit that classifies them as elite athletes). They were classified as eligible for their respective categories and ranked among the top ten nationally according to the criteria of the International Paralympic Committee [

1]. Among the types of disabilities, three athletes had spinal cord injuries due to trauma with lesions below the eighth thoracic vertebra, two had lower limb malformations (Arthrogryposis), two had sequelae due to poliomyelitis, three had below-knee amputations, and one had cerebral palsy. Among the athletes, there was one who achieved second place in the Americas Open and seventh place in the Paralympics, a second and a third place in the Americas Open, and a junior world 2nd place.

Inclusion criteria included being clinically stable and practicing the sport for at least 18 months, making them eligible for Paralympic Powerlifting. Another inclusion criterion was competing officially in the last six months and being ranked among the top 10 in their respective categories at the national level. Those who wished to withdraw from the study or those who had made an error during the biochemical analysis were excluded.

The athletes voluntarily participated in the study and signed informed consent forms in accordance with Resolution 466/2012 of the National Commission for Ethics in Research (CONEP) of the National Health Council (CNS), in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1964, revised in 2013) of the World Medical Association. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Sergipe (ID-CAAE: 67953622.7.0000.5546), under statement number 6.523.247, dated 22 November 2023.

2.3. Blood Biochemical Markers (Cytokines)

Plasma cytokine levels in individuals were determined using the Cytometric Bead Array (CBA) method, following the manufacturer's instructions (Cytometric Bead Array (CBA) Human TH1/TH2 Cytokine Kit II, BD Biosciences, San Diego, USA). We utilized kits for the quantification of inflammatory proteins (Cytokines Th1/Th2 - IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-α). Plasma samples were briefly incubated with capture microspheres coated with specific antibodies for the respective cytokines and chemokines, as well as the proteins in the standard curve. Subsequently, the color reagent (Phycoerythrin - PE) was added, and the samples were incubated for 3 hours. After incubation, the samples were washed with Wash buffer® and centrifuged (200 rpm, 5 minutes, room temperature). The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet containing the microspheres was resuspended with 300µL of Wash buffer. Samples were acquired using the BD FACSCanto II Flow Cytometer (Becton & Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, USA). The results were analyzed using FCAP software (BD Bioscience, USA) and are represented in pg/mL.

2.4. Isometric Force Indicators

To measure muscle strength, the Fatigue Index (FI), Peak Torque (PT), and Rate of Torque Development (RTD) were determined using a Chronojump load cell (Chronojump®, Bosco System, Madrid, Spain) secured to a flat bench with Spider HMS Simond carabiners (Chamonix, France), boasting a breaking load of 21 kN, certified for climbing by the Union International des Associations d'Alpinisme (UIAA). A steel chain with a breaking load of 2300 kg was employed to anchor the load cell to the bench. The perpendicular distance between the load cell and the center of the joint was measured and utilized to calculate joint torques and the fatigue index [

2,

14].

The isometric peak torque (PT) was measured as the maximum torque generated by the muscles of the upper limbs. PT was determined by the product of the isometric peak force, measured between the point where the load cell cable was secured and the adapted bench, adjusted to achieve an angle close to 90° at the elbow, at a distance of 15 cm from the starting point (chest to bar). This angle was verified using a device for measuring the range of motion, Model FL6010 (Sanny®, São Bernardo do Campo, Brazil). Participants were instructed to perform a single maximal movement to elbow extension (as quickly as possible) and then relax for PT assessment.

Therefore, the results in Newton-meters (Nm) were calculated using the formula Nm = (M) (C) (H), where M = body mass in kilograms, C = 9.80665 (acceleration due to gravity), and H = height of the bar relative to the load cell attachment point (0.45 m), corresponding to the height at which the equipment was fixed while maintaining a 90° angle between the forearm and the arm. The Rate of Torque Development (RTD) was determined using the Peak Torque-to-Time ratio until reaching the peak torque (RTD = DPeak Torque/DTime) within 300ms [

15].

2.5. Load Determination

For the determination of the maximum load, a One Repetition Maximum (1RM) test was conducted. Athletes selected a weight, based on their performance in previous competitions, that they could lift only once. The weight was adjusted until the maximum load that could be lifted for a single repetition was reached. If an athlete couldn't complete a single repetition, 2.4% to 2.5% of the weight used was subtracted [

16,

17]. Between attempts, a 3–5-minute rest period was employed. The 1RM assessment test was conducted at least 72 hours prior to the intervention.

2.6. Warm-Up (Exercises Pre-Test) And Training Session

Prior to the intervention (training), athletes underwent a warm-up consisting of shoulder abduction, elbow extension using a pulley, and shoulder rotation. During the warm-up, athletes performed three sets of 10 to 20 repetitions Following the warm-up, the bench press exercise was performed with 2 sets of 10 repetitions (2X10). Throughout the testing, participants were verbally encouraged to execute the movement forcefully and swiftly [

1]. The training session consisted of five sets of five repetitions (5X5) at an intensity of 80-90% of their 1RM [

16].

2.7. Force Exercise Protocol

The bench press exercise was employed, comprising five sets of 5 repetitions with a load ranging from 80% to 90% of 1RM. A 3-minute rest interval was incorporated between sets.

2.8. Recovery Intervention

Passive Recovery: A 15-minute rest period was provided without any specific protocol, during which the subjects remained seated after the intervention [

2,

15].

Cold Water Immersion (CWI): Individuals underwent recovery through immersion in a plastic ice-filled pool (11-15°C ± 0.5°C) for 15 minutes [

2]. During the CWI process, temperature was monitored using the Hikari HTH-240 Digital Thermo-Hygrometer (Hikari®, Shenzhen, China) to ensure thermal consistency throughout the procedure.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

For the descriptive analysis, measures of central tendency, mean (X) ± standard deviation (SD), were employed. The normality of the variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, taking into consideration the sample size. The data exhibited homogeneity and a normal distribution. Performance comparison between groups was conducted using a Two-way ANOVA test, with Bonferroni post hoc analysis. Statistical analysis was carried out using the computerized Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 22.0. The adopted significance level was p < 0.05. Effect size was assessed using partial eta squared (η²p), with values indicating low effect (≤0.05), moderate effect (0.05 to 0.25), high effect (0.25 to 0.50), and very high effect (> 0.50) [

18,

19].

3. Results

Table 1, you can find the results for maximum isometric strength (MIF), time to reach MIF, and Rate of Force Development (RFD) before and after the types of recovery.

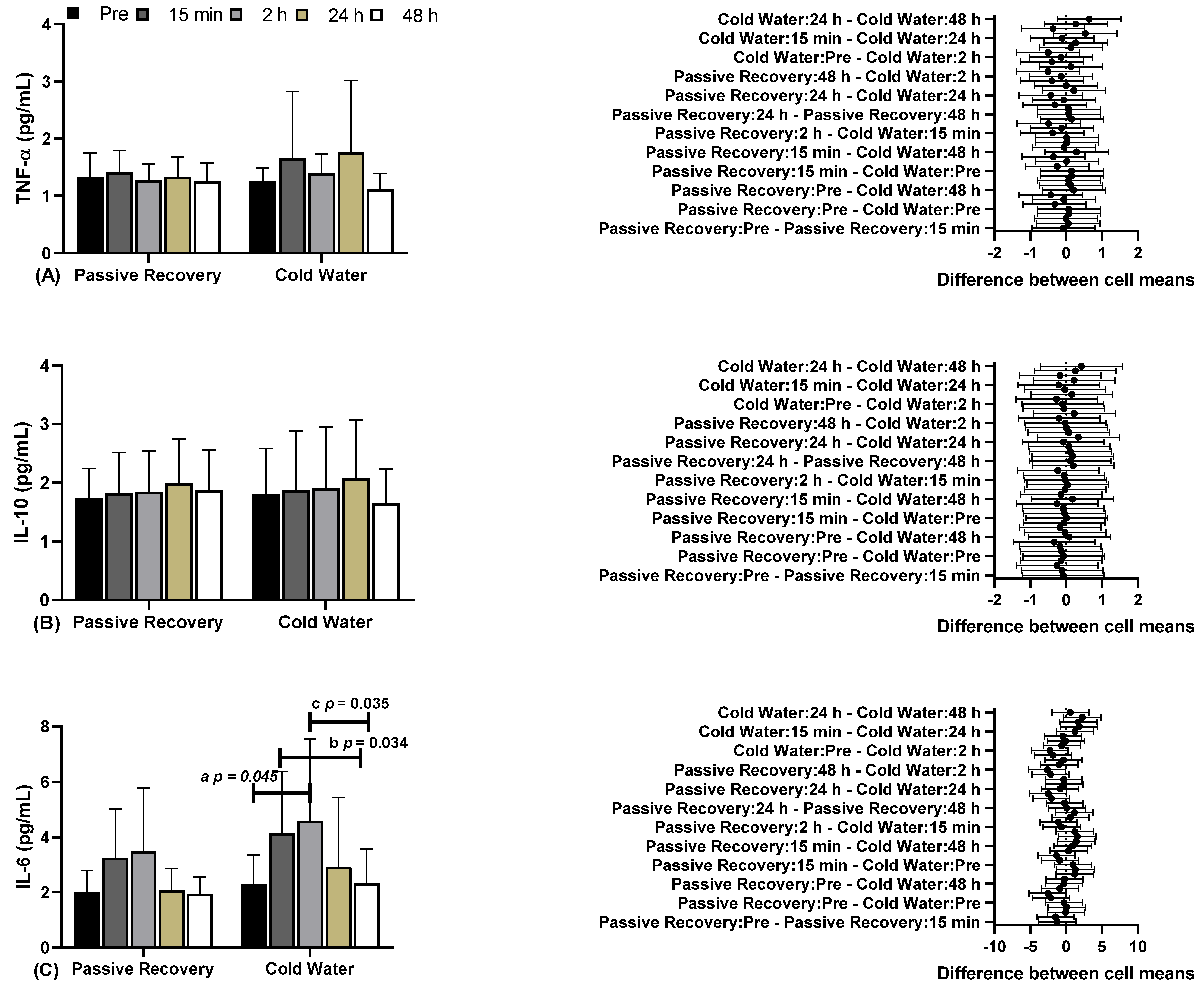

In

Figure 2, you can see the results of blood biochemical markers, including Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha (TNF-α), Interleukin 10 (IL-10), and Interleukin 6 (IL-6), under Passive and CWI Recovery conditions at various time points before and after. Regarding (A) TNF-α and (B) IL-10, there were no differences between the time points and conditions. Concerning (C) IL-6, significant differences were observed between CWI before (2.29±1.08, 95% CI 1.57-3.01) and CWI 2 hours later (2h) (4.59±2.96, 95% CI 2.60-6.57; "a" p=0.045), and between CWI 15 minutes later (15 min) (4.14±2.24, 95% CI 2.63-5.64) and CWI 48 hours later (48 h) (2.33±1.25, 95% CI 1.49-3.17; "b" p=0.034). There were differences between CWI 2h (4.14±2.24, 95% CI 2.63-5.64) and CWI 48 h (2.33±1.25, 95% CI 1.49-3.17; "c" p=0.035; F=9.202; η²p=0.479; high effect).

Regarding (A) TNF-α and (B) IL-10, there were no differences between time points and conditions. Regarding (C) IL-6, there were significant differences between CW before (2.29±1.08, 95% CI 1.57-3.01) and CW 2 hours later (2h) (4.59±2.96, 95% CI 2.60-6.57; “a” p=0.045), and between CW 15 minutes later (15 min) (4.14±2.24, 95% CI 2.63-5.64) and CW 48 hours later (48 h) (2.33±1.25, 95% CI 1.49-3.17; “b” p=0.034). There were differences between CW 2h (4.14±2.24, 95% CI 2.63-5.64) and CW 48 h (2.33±1.25, 95% CI 1.49-3.17; “c” p = 0.035; F=9.202; ɳ2p=0.479; high effect).

4. Discussion

Although meta-analyses on this topic have been conducted in general athletic populations [

10,

12], research focusing on para-athletes remains limited. This gap may be attributed, in part, to challenges associated with cold-water immersion for these athletes [

2]. Therefore, the present study sought to assess the impact of various recovery methods—specifically, passive recovery (RP) and cold-water immersion (CWI)—on muscle damage in Paralympic powerlifting athletes. To enhance clarity, we have organized the discussion into two distinct sections (Effect on maximal isometric strength and Biochemical markers of muscle damage).

4.1. Effect on Maximal Isometric Strength

CWI has been used to enhance post-training recovery [

10]. However, contrary to this, CWI recovery after training would promote specific physiological adaptations and has shown negative effects on strength training [

13]. This assertion is based on the detrimental effects of CWI on hypertrophy-related aspects, but it tends to improve indicators related to neural aspects, such as power/force development rate [

20,

21]. Therefore, the application of CWI in post-exercise recovery could have negative effects on strength training aimed at morphological aspects and positive effects on rapid force generation, which is more focused on neural aspects [

22].

Despite contradictory results in the literature regarding CWI after strength training [

22,

23,

24], our study found a positive association between CWI recovery and strength indicators, consistent with other studies linking this method to post-exercise recovery, especially in terms of rapid strength recovery [

25,

26]. Given the highly specific nature of strength [

2], strength training is subject to various interferences, including movement patterns, range and speed of motion, load intensity, among others [

1,

3]. However, it is suggested that dynamic strength measures may interfere with strength gain assessment, increasing the likelihood that impairment was caused by CWI [

23]. This was not the case in our study, likely due to the extremely specific population of Paralympic athletes evaluated.

4.2. Biochemical Markers of Muscle Damage

In this study, no differences were observed in the evaluated markers (TNF-α, IL-10), consistent with other studies [

27,

28], where CWI had no effect on plasma markers when assessed up to 72 hours post-intervention. However, when evaluating IL-6, differences were observed in the CWI method between the time points before, after 15 minutes, and after 48 hours. There were no differences between the methods, and no differences were observed in the passive recovery method.

When investigating the adaptations and consequences of training, it has been observed that exercise can induce muscle damage [

1,

3]. Muscle damage tends to trigger inflammatory responses aimed at muscle repair [

6]. During recovery, pro-inflammatory cytokines tend to be released, such as TNF-α, which play a role in muscle injury and tissue degradation signaling [

29]. Furthermore, the release of neutrophils, inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, among others), and reactive oxygen species tends to promote contractile dysfunction and increased catabolic activity, among other effects [

30]. TNF-α, in particular, has been associated with a decrease in contractile capacity following exercise-induced damage [

10]. However, our study did not show any significant difference between passive and CWI recovery methods, and there was no significant increase in TNF-α in either method.

Contrary to these findings, regarding TNF-α, CWI recovery alone did not reduce the immune response to intense exercise [

7]. Other studies have reported a slight increase or no increase in circulating TNF-α in different exercise protocols [

31,

32,

33]. However, in research involving untrained subjects, TNF-α increased after eccentric exercises [

7]. On the other hand, it has been reported that trained athletes exhibit a relatively higher TNF-α response, which was not observed in our study. Additionally, in line with our findings, it was reported that CWI recovery had no effect on TNF-α after exercise [

7,

34]. Our findings suggest that CWI recovery may not be effective regarding TNF-α.

Regarding IL-10, it is well-established that muscle contraction resulting from exercise tends to produce and release myokines like IL-6 [

35]. Furthermore, the increase in IL-6 levels after exercise tends to promote an increase in anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-10 [

36]. Another study observed the association of IL-6 with an anti-inflammatory profile, resulting in a decrease in TNF-α and an increase in IL-10 levels [

37]. Similarly, another study indicated that IL-6 has a modulating effect on exercise and has anti-inflammatory effects [

38], which is consistent with our findings. Thus, there appears to be an association between IL-6/IL-10, indicating an improvement in the inflammatory profile after high-intensity exercise [

39].

Regarding IL-6, it tends to limit movement, acting as a protector against fatigue, particularly in prolonged or intense exercises [

40]. On the other hand, IL-6 is believed to stimulate cellular apoptosis [

41], potentially amplifying the inflammatory response [

40,

41]. This tends to trigger the activation and degradation of damaged cells, including muscle cells, through inflammatory signaling pathways [

42]. Consequently, this can lead to a decrease in muscle function and strength loss [

41], which plays a role in subsequent recovery [

43].

Another important point is that inflammatory events have a reparative effect and contribute to muscle remodeling in response to training [

41]. In line with our findings, another study observed that IL-6 levels practically returned to their initial values after 24 hours, a timing consistent with our study [

44].

5. Conclusions

Muscle damage can result from metabolic, structural, and microvascular changes, leading to both systemic and local effects. In light of this, the results indicate that the interventions affect some aspects of local recovery, but systemic effects still persist. Furthermore, the results suggest that the CWI method outperformed the other methods at the 24-hour mark. In terms of static strength indicators, it was observed that MIF remained more stable in CWI when compared to PR. At 24 hours, CWI showed better performance than PR in MIF, time to MIF, and RFD compared to the post-training moment with PR, with CWI still showing better values than PR at this same moment. Moreover, CWI at 48 hours was superior, particularly in terms of time to MIF. Based on the findings, CWI can be considered an important method that could lead to better recovery compared to passive methods, especially concerning static strength indicators, at the 24 and 48-hour marks after training

Author Contributions

FJA, WYHS, SCM, ANS and CJB contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by WYHS, SCM, ELMV and EAM. The first draft of the manuscript was written by FJA and DIVP and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was performed in line with Resolution 466/2012 of the National Research Ethics Commission (CONEP) of the National Health Council and following the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (1964, revised in 2013) of the World Medical Association. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Sergipe (ID-CAAE: 67953622.7.0000.5546), under statement number 6.523.247, dated 22 November 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

All athletes voluntarily participated in this study and provided written informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support this study can be obtained at

https://www.ufs.br/ Department of Physical Education, accessed on 11 January 2024, or the data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aidar, F.J.; Brito, C.J.; de Matos, D.G.; de Oliveira, L.A.S.; de Souza, R.F.; de Almeida-Neto, P.F.; de Araújo Tinoco Cabral, B.G.; Neiva, H.P.; Neto, F.R.; Reis, V.M.; et al. Force-Velocity Relationship in Paralympic Powerlifting: Two or Multiple-Point Methods to Determine a Maximum Repetition. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 14, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, W.Y.H.D.; Aidar, F.J.; Matos, D.G. de; Van den Tillaar, R.; Marçal, A.C.; Lobo, L.F.; Marcucci-Barbosa, L.S.; Machado, S. da C.; Almeida-Neto, P.F. de; Garrido, N.D.; et al. Physiological and Biochemical Evaluation of Different Types of Recovery in National Level Paralympic Powerlifting. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidar, F.J.; Cataldi, S.; Badicu, G.; Silva, A.F.; Clemente, F.M.; Bonavolontà, V.; Greco, G.; Getirana-Mota, M.; Fischetti, F. Does the Level of Training Interfere with the Sustainability of Static and Dynamic Strength in Paralympic Powerlifting Athletes? Sustainability 2022, 14, 5049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, L. You Can’t Shoot Another Bullet until You’ve Reloaded the Gun: Coaches’ Perceptions. Pract. Exp. Deloading Strength Phys. Sports.

- Peake, J.M.; Neubauer, O.; Della Gatta, P.A.; Nosaka, K. Muscle Damage and Inflammation during Recovery from Exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. Bethesda Md 1985 2017, 122, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, G.S.; Aidar, F.J.; Matos, D.G.; Marçal, A.C.; Santos, J.L.; Souza, R.F.; Carneiro, A.L.; Vasconcelos, A.B.; Da Silva-Grigoletto, M.E.; van den Tillaar, R.; et al. Effects of Ibuprofen Intake in Muscle Damage, Body Temperature and Muscle Power in Paralympic Powerlifting Athletes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 5157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, J.R.; Fragala, M.S.; Jajtner, A.R.; Gonzalez, A.M.; Wells, A.J.; Mangine, G.T.; Robinson, E.H.; McCormack, W.P.; Beyer, K.S.; Pruna, G.J.; et al. β-Hydroxy-β-Methylbutyrate (HMB)-Free Acid Attenuates Circulating TNF-α and TNFR1 Expression Postresistance Exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. Bethesda Md 1985 2013, 115, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, T.J.; Lunt, K.M.; Stephenson, B.T.; Goosey-Tolfrey, V.L. The Effect of Pre-Cooling or per-Cooling in Athletes with a Spinal Cord Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2022, 25, 606–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griggs, K.E.; Price, M.J.; Goosey-Tolfrey, V.L. Cooling Athletes with a Spinal Cord Injury. Sports Med. Auckl. NZ 2015, 45, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Ji, Y.; Ye, Q. Effect of Cold Water Immersion Dose on the Recovery of Skeletal Muscle Fatigue Induced by Exercise: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Chin. J. Tissue Eng. Res. 2024, 28, 5732. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, F.; Kabachkova, A.V.; Jiao, L.; Zhao, H.; Kapilevich, L.V. Effects of Cold Water Immersion after Exercise on Fatigue Recovery and Exercise Performance--Meta Analysis. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1006512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grgic, J. Effects of Post-Exercise Cold-Water Immersion on Resistance Training-Induced Gains in Muscular Strength: A Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2023, 23, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malta, E.S.; Dutra, Y.M.; Broatch, J.R.; Bishop, D.J.; Zagatto, A.M. The Effects of Regular Cold-Water Immersion Use on Training-Induced Changes in Strength and Endurance Performance: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. Auckl. NZ 2021, 51, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aidar, F.J.; Fraga, G.S.; Getirana-Mota, M.; Marçal, A.C.; Santos, J.L.; de Souza, R.F.; Vieira-Souza, L.M.; Ferreira, A.R.P.; de Matos, D.G.; de Almeida-Neto, P.F.; et al. Evaluation of Ibuprofen Use on the Immune System Indicators and Force in Disabled Paralympic Powerlifters of Different Sport Levels. Healthc. Basel Switz. 2022, 10, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidar, F.J.; Clemente, F.M.; de Lima, L.F.; de Matos, D.G.; Ferreira, A.R.P.; Marçal, A.C.; Moreira, O.C.; Bulhões-Correia, A.; de Almeida-Neto, P.F.; Díaz-de-Durana, A.L.; et al. Evaluation of Training with Elastic Bands on Strength and Fatigue Indicators in Paralympic Powerlifting. Sports Basel Switz. 2021, 9, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidar, F.J.; Fraga, G.S.; Getirana-Mota, M.; Marçal, A.C.; Santos, J.L.; de Souza, R.F.; Ferreira, A.R.P.; Neves, E.B.; Zanona, A. de F.; Bulhões-Correia, A.; et al. Effects of Ibuprofen Use on Lymphocyte Count and Oxidative Stress in Elite Paralympic Powerlifting. Biology 2021, 10, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resende, M. de A.; Vasconcelos Resende, R.B.; Reis, G.C.; Barros, L. de O.; Bezerra, M.R.S.; Matos, D.G. de; Marçal, A.C.; Almeida-Neto, P.F. de; Cabral, B.G. de A.T.; Neiva, H.P.; et al. The Influence of Warm-Up on Body Temperature and Strength Performance in Brazilian National-Level Paralympic Powerlifting Athletes. Medicina (Mex.) 2020, 56, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gignac, G.E.; Szodorai, E.T. Effect Size Guidelines for Individual Differences Researchers. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 102, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1988; ISBN 978-0-203-77158-7. [Google Scholar]

- Del Vecchio, A.; Negro, F.; Holobar, A.; Casolo, A.; Folland, J.P.; Felici, F.; Farina, D. You Are as Fast as Your Motor Neurons: Speed of Recruitment and Maximal Discharge of Motor Neurons Determine the Maximal Rate of Force Development in Humans. J. Physiol. 2019, 597, 2445–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maden-Wilkinson, T.M.; Balshaw, T.G.; Massey, G.J.; Folland, J.P. Muscle Architecture and Morphology as Determinants of Explosive Strength. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2021, 121, 1099–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, A.C.; Fyfe, J.J. Post-Exercise Cold Water Immersion Effects on Physiological Adaptations to Resistance Training and the Underlying Mechanisms in Skeletal Muscle: A Narrative Review. Front. Sports Act. Living 2021, 3, 660291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamane, M.; Ohnishi, N.; Matsumoto, T. Does Regular Post-Exercise Cold Application Attenuate Trained Muscle Adaptation? Int. J. Sports Med. 2015, 36, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich, M.; Faude, O.; Klein, M.; Pieter, A.; Emrich, E.; Meyer, T. Strength Training Adaptations after Cold-Water Immersion. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2014, 28, 2628–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingram, J.; Dawson, B.; Goodman, C.; Wallman, K.; Beilby, J. Effect of Water Immersion Methods on Post-Exercise Recovery from Simulated Team Sport Exercise. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2009, 12, 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Versey, N.G.; Halson, S.L.; Dawson, B.T. Water Immersion Recovery for Athletes: Effect on Exercise Performance and Practical Recommendations. Sports Med. Auckl. NZ 2013, 43, 1101–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pointon, M.; Duffield, R.; Cannon, J.; Marino, F.E. Cold Water Immersion Recovery Following Intermittent-Sprint Exercise in the Heat. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2012, 112, 2483–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilhem, G.; Hug, F.; Couturier, A.; Regnault, S.; Bournat, L.; Filliard, J.-R.; Dorel, S. Effects of Air-Pulsed Cryotherapy on Neuromuscular Recovery Subsequent to Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage. Am. J. Sports Med. 2013, 41, 1942–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoma, A.; Lightfoot, A.P. NF-kB and Inflammatory Cytokine Signalling: Role in Skeletal Muscle Atrophy. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 1088, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadda, K.R.; Puthucheary, Z. Persistent Inflammation, Immunosuppression, and Catabolism Syndrome (PICS): A Review of Definitions, Potential Therapies, and Research Priorities. Br. J. Anaesth. 2024, 132, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkaya, E.C.; Koc, B.; Dalkiran, B.; Calis, G.; Dayi, A.; Kayatekin, B.M. High-Intensity Interval Training Ameliorates Spatial and Recognition Memory Impairments, Reduces Hippocampal TNF-Alpha Levels, and Amyloid-Beta Peptide Load in Male Hypothyroid Rats. Behav. Brain Res. 2024, 458, 114752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Qian, H.; Xin, X.; Liu, Q. Effects of Different Exercise Modalities on Inflammatory Markers in the Obese and Overweight Populations: Unraveling the Mystery of Exercise and Inflammation. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1405094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringleb, M.; Javelle, F.; Haunhorst, S.; Bloch, W.; Fennen, L.; Baumgart, S.; Drube, S.; Reuken, P.A.; Pletz, M.W.; Wagner, H.; et al. Beyond Muscles: Investigating Immunoregulatory Myokines in Acute Resistance Exercise - A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2024, 38, e23596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, C.-Y.; Lee, J.-P.; Tsai, Y.-S.; Lee, S.-D.; Kao, C.-L.; Liu, T.-C.; Lai, C.-H.; Harris, M.B.; Kuo, C.-H. Topical Cooling (Icing) Delays Recovery from Eccentric Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2013, 27, 1354–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karstoft, K.; Pedersen, B.K. Skeletal Muscle as a Gene Regulatory Endocrine Organ. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2016, 19, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal, L.G.; Lopes, M.A.; Batista, M.L. Physical Exercise-Induced Myokines and Muscle-Adipose Tissue Crosstalk: A Review of Current Knowledge and the Implications for Health and Metabolic Diseases. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steensberg, A.; Fischer, C.P.; Keller, C.; Møller, K.; Pedersen, B.K. IL-6 Enhances Plasma IL-1ra, IL-10, and Cortisol in Humans. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 285, E433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellingsgaard, H.; Hojman, P.; Pedersen, B.K. Exercise and Health—Emerging Roles of IL-6. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2019, 10, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, A.M.; Isanejad, A.; Sadighi, S.; Mardani, M.; Kalaghchi, B.; Hassan, Z.M. High-Intensity Interval Training Can Modulate the Systemic Inflammation and HSP70 in the Breast Cancer: A Randomized Control Trial. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 145, 2583–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzolini, F.; Dolcetti, E.; Bruno, A.; Rovella, V.; Centonze, D.; Buttari, F. Physical Exercise and Synaptic Protection in Human and Pre-Clinical Models of Multiple Sclerosis. Neural Regen. Res. 2024, 19, 1768–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabzevari Rad, R.; Panahzadeh, F. Muscle-to-Organ Cross-Talk Mediated by Interleukin 6 during Exercise: A Review. Sport Sci. Health 2024, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Cavalcante, M.D.; Couto, P.G.; Azevedo, R. de A.; Gáspari, A.F.; Coelho, D.B.; Lima-Silva, A.E.; Bertuzzi, R. Stretch-Shortening Cycle Exercise Produces Acute and Prolonged Impairments on Endurance Performance: Is the Peripheral Fatigue a Single Answer? Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2019, 119, 1479–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millet, G.Y.; Martin, V.; Temesi, J. The Role of the Nervous System in Neuromuscular Fatigue Induced by Ultra-Endurance Exercise. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. Physiol. Appl. Nutr. Metab. 2018, 43, 1151–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, A.R.; Pedersen, B.K. The Biological Roles of Exercise-Induced Cytokines: IL-6, IL-8, and IL-15. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. Physiol. Appl. Nutr. Metab. 2007, 32, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).