1. Background

Coronaviruses belong to the Coronaviridae family. They are RNA viruses with an enveloped structure and a positive single-stranded genome. This genome contains over 29,891 nucleotides, which encode for 9,890 amino acids. It also contains numerous open-reading frames (ORFs) that code for both structural (SP) and non-structural (NSP) proteins. These proteins play crucial roles in the viral life cycle and pathogenic processes [

1]. The structural proteins consist of S (spike protein), E (envelope protein), M (membrane protein), and N (nucleocapsid protein). Furthermore, there are sixteen non-structural proteins (nsp1–16) that assist in viral metabolism and interaction with the host immune system [

2]. The SARS-CoV-2 gene's role in diagnostic tool development is multifaceted, encompassing rapid assay development, enhanced detection sensitivity, variant identification, and informing public health responses [

3,

4]. Its significance underscores the critical intersection of genetics, diagnostics, and public health in managing infectious disease threats effectively [

4]

.

In cases of epidemics like COVID-19, it is crucial to detect the pathogen early in order to effectively manage and control potential pandemics [

5]. It is believed that as many as 40% of individuals with SARS-CoV-2 infection may not show any symptoms (asymptomatic) or show symptoms at a later stage (pre-symptomatic), yet still have the potential to spread the virus to others [

6]. Therefore, a dependable laboratory diagnosis is a key tool in promoting, preventing, and controlling infectious [

7].

The diagnostic methods for COVID-19 can be divided into two main categories: immunological and molecular tests. Immunological tests involve serological tests that detect antibodies in blood or viral antigens in respiratory secretions. These tests can be performed using point-of-care platforms. Serological tests are particularly important in diagnosing patients with mild to moderate disease when molecular diagnostics are not available [

8]. On the other hand, molecular tests detect SARS-CoV-2 RNA, in various specimens primarily in nasopharyngeal samples. These tests typically require proper laboratory infrastructure. Unlike serological tests, most molecular tests require specialized laboratories with advanced equipment and highly trained staff, which limits their use [

9]. In addition to the aforementioned tests, other laboratory parameters have been utilized to assist in monitoring patients with COVID-19 [

10,

11,

12].

SARS-CoV-2 can be detected in various specimens, including swabs (nasopharyngeal, oropharyngeal, and anal), saliva, and sputum. The virus can also be found in other bodily fluids like blood, urine, and faeces [

13]. This technique is the most widely used with a sensitivity that reaches 98 % [

14]. Nasopharyngeal is considered the standard method to collect SARS-CoV-2 samples safely and conveniently as there is no direct contact between the health practitioner and the specimen [

15].

The "gold standard" assay for diagnosing both symptomatic and asymptomatic cases is real-time reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) [

16]. The first protocol, recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO), was published (2020) by the Charité Institute at Berlin University in Germany [

4]. This protocol utilizes TaqMan technology and specific primers and probes to detect the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), envelope protein (E), and nucleocapsid protein (N) genes. Additionally, the WHO has reported several in-house methods which are currently being validated in partner laboratories [

4] listed in

Table 1.

Typically, three steps need to be completed before conducting quantitative PCR. These steps involve 1) purifying total RNA from the sample, 2) eluting and potentially concentrating the material, and 3) synthesizing complementary DNA (cDNA) from the template RNA [

17]

. However, it is important to note that RNA extraction can be a labour-intensive, infectious, costly, and time-consuming process that requires manual handling, which may introduce experimental errors [

17,

18]

.

To begin, the viral RNA is isolated from the collected specimen using commercially available RNA extraction kits. This step is crucial to ensure accurate results by proper sample handling and preventing contamination. Next, complementary DNA (cDNA) is synthesized using a master mix that contains the reverse transcriptase enzyme. The mixture is incubated in a thermal cycler to initiate the reaction. After that, the cDNA, primers, distilled water, and either a DNA probe or SYBR green are pipetted into a 96-well plate. The plate is then placed in the RT-qPCR instrument, and the appropriate thermal cycles are set. To confirm the absence of contaminants and avoid false-positive results when diagnosing COVID-19 patients, a negative control should be used. Additionally, a positive control should be included to ensure an accurate interpretation of the results [

19].

The amplification process involves three basic steps: denaturation, annealing, and extension. During denaturation, the temperature increases to separate the double-stranded DNA (dsDNA). During annealing, the temperature drops to allow the primers to bind to the targeted sequences. During extension, the temperature rises, enabling DNA polymerase to add nucleotides to the newly formed DNA strand. This process is repeated approximately 40 times, resulting in new copies of DNA after each cycle. A fluorescent signal is produced each time the probes are released or SYBR green binds to the newly formed dsDNA. Therefore, the fluorescent signal intensity increases with the number of DNA copies after each cycle. The Ct values, or cycle threshold, indicate the number of cycles required for the fluorescent signal intensity to exceed a predefined threshold. Samples with a higher viral load will have a lower Ct value, while higher Ct values indicate smaller amounts of RNA copies in a given sample [

19,

20].

Since its emergence, reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) has been the first approved standard technique for detecting SARS-CoV-2. RT-qPCR is a molecular diagnostic technique that detects the presence of nucleic acids by targeting and amplifying specific genes. This process creates millions of copies from a small number of nucleic acids, allowing for real-time monitoring [

19,

21,

22]. In this technique, primers play a crucial role as they bind to the targeted gene in the DNA strand. Well-designed primers with high specificity are essential to avoid non-specific amplification and the formation of unwanted structures, such as primer dimers, which could lead to false-positive results. Detection of the targeted gene is indicated by DNA probes or fluorescent dyes, such as SYBR green. SYBR green is an intercalating dye that binds to all double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) and produces a fluorescent signal. Probes, on the other hand, consist of a fluorescent reporter that binds to the 5′-end, and a quencher dye that binds to the 3′-end of a specific target in the DNA. When the enzyme DNA polymerase cleaves the probe, the released reporter emits a fluorescent signal, which is detected by the instrument [

19].

Results of different RT-PCR protocols have shown variation in their performance depending on the primers and probes [

23]. False-negative results can occur mainly because of inadequate extraction of nucleic acid; poor sample quality; low viral load; sample collection time; incorrect sample storage, transportation, and handling; and PCR inhibition [

24,

25]. Extraction of RNA is a specialized, time-consuming, and labour-intensive process that often creates a bottleneck in workflow. The development of new diagnostic platforms that could improve molecular methods in terms of speed, sensitivity, and accessibility in the diagnosis of COVID-19 is highly needed. However, with the global shortage of extaction kits, many countries have begun to carry out in-house RT-PCR to overcome this shortage [

23].

It is, therefore, important to identify a method for pandemic testing, that does not require advanced resources and extended time. A test that delivers a result within 2-3 hours would be a preventive approach as the patients could receive the necessary support and care immediately [

26]. Globally, various direct approaches that avoid RNA extraction have been suggested, including heat-processed methods [

27,

28]. However our method is novel that doesn’t use chelating agents, proteinaseK and other additional chemicals. We use heat and dilution and reduces the cost of the RNA extraction. This was the rationale to initiate this study project. The objective of this study was to compare the diagnostic performance of extraction-free heating and extraction-based methods for SARS-CoV-2 detection.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Sample Size Calculation

SARS-CoV-2 tested individuals during the fifth wave of the pandemic (June to August, 2020) are considered as the source population. The study involved random selection and retrieval of stored nasopharyngeal specimens. Sample size were calculated using double population propotion formula and obtained a total of 300 (190 positive and 110 Negative) samples. therefore, a total of 300 samples were retrospectively obtained from the National Virology Reference Laboratory, Ethiopian Public Health Institute, in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia which serves as the first national COVID-19 testing laboratory. These specimens were re-tested using the extraction-free dilution and heating (EFHD) technique and comparision were made against extraction based detection method. The clinical samples were handled and processed in a Biosafety Laboratory-2 (BSL-2) at the virology laboratory.

2.2. Method Validation

We intentionally choose a specimen with a Ct-value of 19 and an Internal control (IC) (with VIC dye) having Ct value of 19. This specimen was diluted 1:2 and 1:4 with RNAse-free water. The diluted specimens were then heated at temperatures of 62°C and 72°C for 10, 15, 20, and 30 minutes, as well as at 96°C for 5, 10, 15, and 20 minutes using Eppendorf thermomixer. Considering these heated and diluted specimens as an RNA eluate, we added 10µL of the eluate to 20µL of master mix and performed RT-qPCR using the ABI 7500 (Thermo-Fisher Inc.) using DAAN detection kits (Daan Gene Co., Ltd). The target genes for DAAN detection kits for SARS-CoV-2 primarily focused on the N gene and the ORF1ab gene. These genes are crucial for the detection and identification of the SARS-CoV-2 virus through PCR-based assays. The results showed that at a temperature of 72°C, the N/ORF1a/b Ct values were 24 at 15 min. and 26 at 30 min, , and the VIC (IC) values were 26 at 15 min and 27 at 30 min, respectively. Compared to the conventional extraction-based methods, a difference of five cycle thresholds (Ct-values) was observed. Therefore, a promising and comparable cycle threshold was obtained in the 1:2 diluted specimens exposed to 72°C for 15 minutes.. Following these experimental results, the following study was conducted.

2.3. Selection of Stored Specimens

A total of 300 nasopharyngeal specimens were retrospectively obtained from the repository of the national virology reference laboratory at the Ethiopian Public Health Institute. These specimens were initially collected for clinical diagnosis of COVID-19 using Viral Transport Media (VTM). We randomly choose 190 SARS-CoV-2 positive and 110 negative specimens from the repository of the national reference laboratory, using the unique numbers assigned to each specimen in the laboratory register.

2.4. Extraction Based Protocol (Reference Method)

Extraction was performed manually using the QIAamp Viral RNA Kit (QIAGEN)[

29] following the standard protocol. Samples were lysed under highly denaturing conditions to inactivate RNases and to ensure the isolation of intact viral RNA. Buffering conditions were then adjusted to bind RNA to the membrane of the QIAamp plates. Contaminants were efficiently removed using 2 wash buffers and a final wash with ethanol. High-quality RNA was eluted in a special RNase-free buffer, ready for direct use or safe storage. The purified RNA was free of proteins, nucleases, and other contaminants or inhibitors. The special QIAamp membrane guarantees the extremely high recovery of pure, intact RNA without the use of phenol/chloroform extraction or alcohol precipitation.

2.5. PCR Reagent Preparation (Master Mix Preparation)

The PCR reaction solutions A and B (NC/ORF1ab/N) were thawed at room temperature and thoroughly mixed. The solution was then centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for a few seconds. N, which represents the total number of specimens to be tested along with the number of NC (ORF1ab/N) negative controls and positive controls, were added to the PCR reaction tubes. After ensuring thorough mixing of the components, the tubes were briefly centrifuged to ensure all the liquid settled at the bottom of the tube. Finally, 20 µL of the amplification system was aliquoted into each PCR tube. 5 μL of the negative control material, RNA from the specimens to be tested, and positive control material were added to the PCR reaction tubes. After securely covering the tubes, they were transferred to the amplification detection area following centrifugation at 8,000 rpm for brief period of time. Lastly, the reaction tubes were placed in the instrument's sample sink.

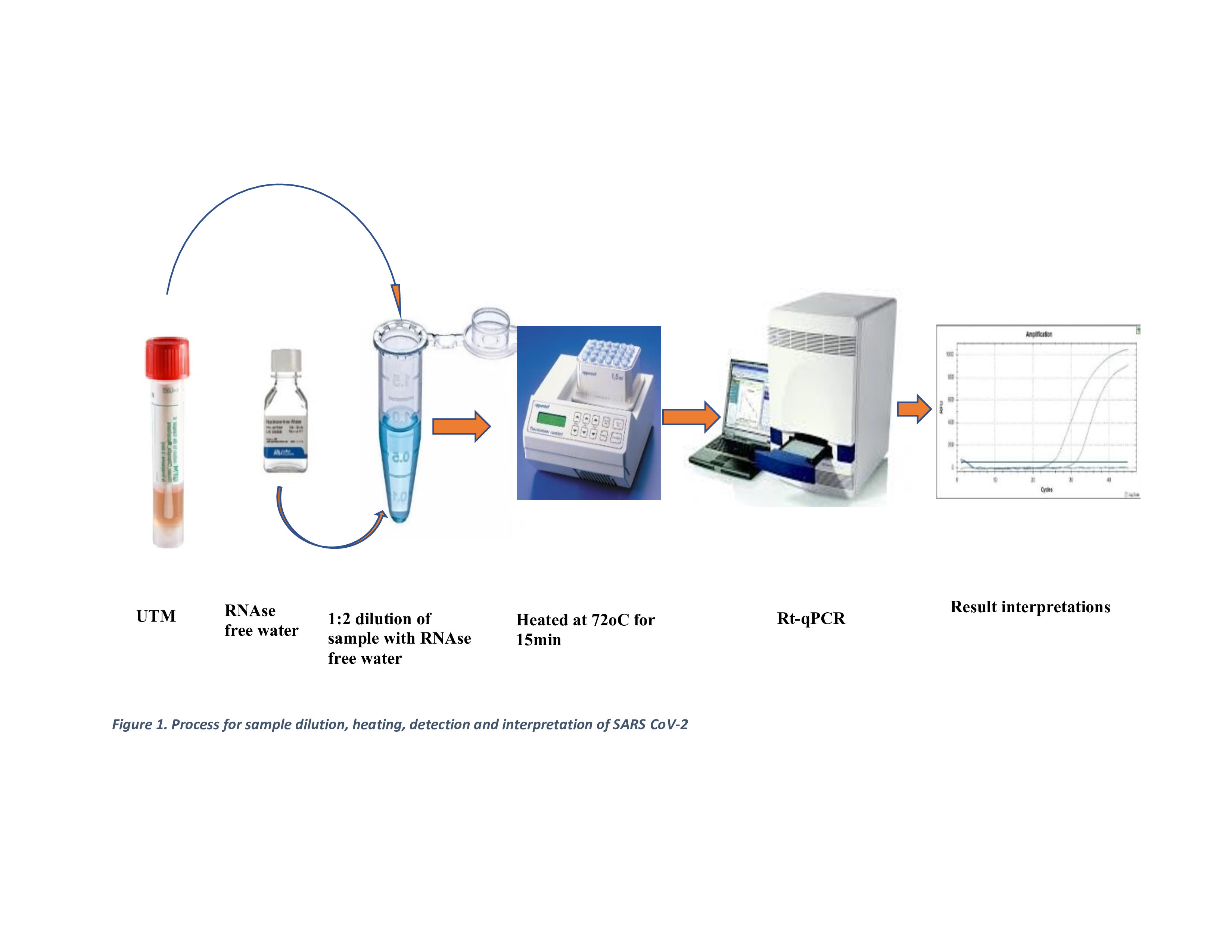

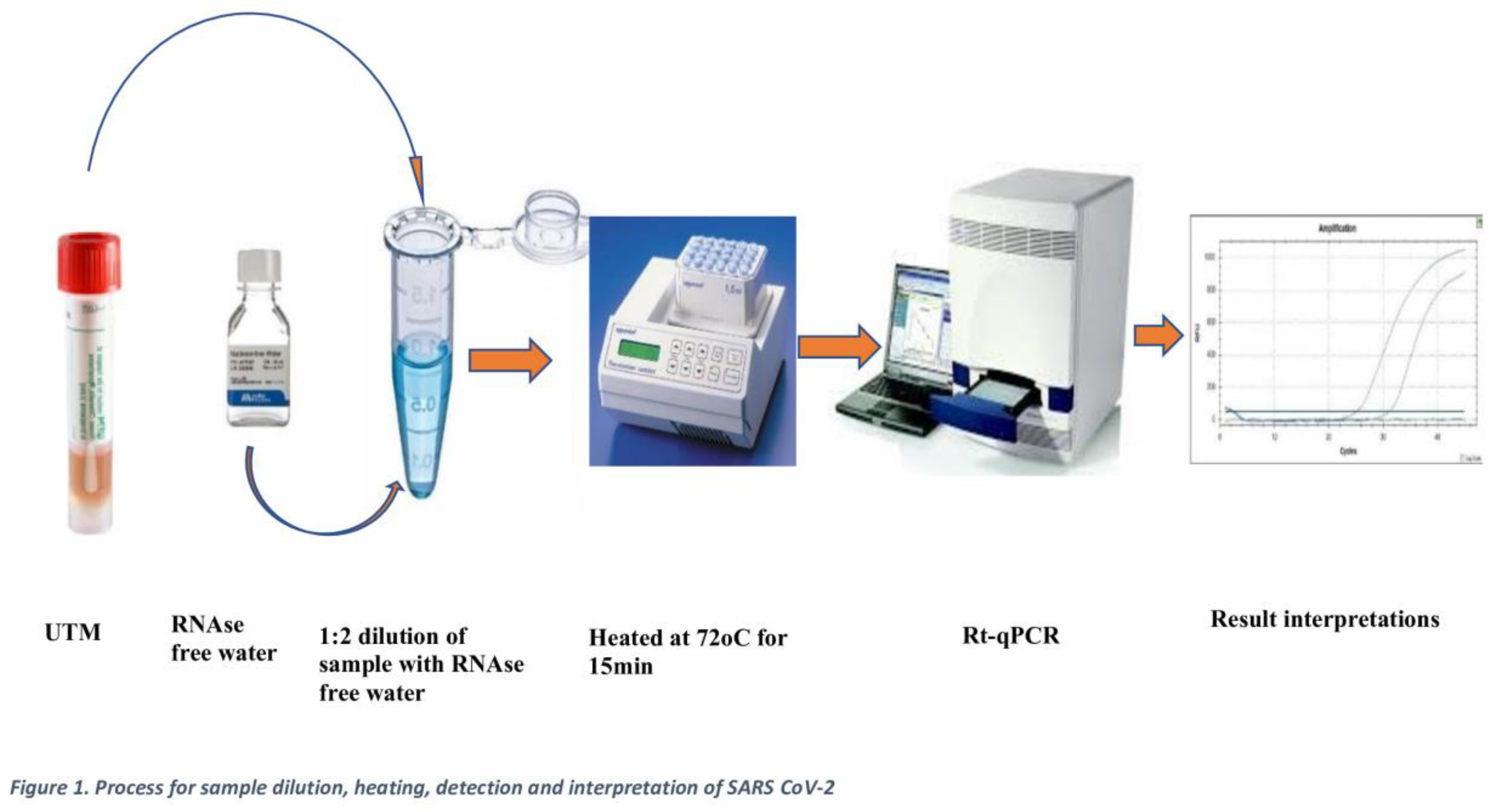

2.6. Extraction-Free (EFHD) Protocols (Index Method)

100 µL of each sample was transferred to a heat-resistant 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube and heated at 72°C for 15 minutes using an Eppendorf Thermomixer. The eluates were then stored at -20°C for up to 4 hours while waiting for other clinical samples to be processed in batches. Afterwards, 10 µL of the eluate was mixed with 20 µL of the master mix, following a similar procedure to the extraction-based eluted samples. Worksheets were prepared with other clinical samples, and detection was conducted using the Applied Biosystems ABI7500 machine, following the laboratory protocol as shown in

Figure 1.

2.7. SARS-CoV-2 Detection (RT-qPCR)

The detection (RT-qPCR) was carried out using the ABI 7500 Fast instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific), along with the DAan kits (Daan Gene Co., Ltd). The protocol consisted of a single cycle of reverse transcription at 50°C for 15 minutes, followed by a single cycle of polymerase activation at 95°C for 2 minutes. This was followed by 40 amplification cycles, each consisting of 15 seconds at 95°C and 60 seconds at 60°C. The purpose of this assay was to detect the presence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus using primers and probes that correspond to the N/ORF1a/b gene. For comparison, the standard extraction-based (EB) technique was used as a reference method, alongside the Extraction-free heated (EFHD) method. The laboratory protocol was used to interpret the results. A Ct value greater than 40, along with the absence of an amplification curve in both the FAM and VIC channels, indicated the absence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the sample. On the other hand, a clear amplification curve in both the FAM and VIC channels, with a Ct value of 40 or less, indicated a positive result for SARS-CoV-2 RNA. If the Ct value was 40 or less and an amplification curve was detected in only one channel (either FAM or VIC), while the other channel showed no amplification curve, the results were re-tested. The repeated result was considered the final result.

At each step of both methods, strict quality control measures were taken. In addition to positive and negative control provided in the kit for the extraction method, we used extraction control were also used. All measuring devices in the laboratory were within calibration date, including the thermal cycler.

2.8. Ethics Statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Aklilu Lemma Institute of Pathobiology (ALIPB), Addis Ababa University (AAU) in Ethiopia, with protocol number ALIPB IRB/52/2013/21. Permission letter was obtained from EPHI with reference number of WG12/19 on April 21, 2021. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

The data were summarized as mean ± Standard Error of the Mean (SEM) and R² (coefficient of determination). The D'Agostino & Pearson test with a 95% confidence interval was used to test for normality. Confidence intervals (CI) for sensitivity, specificity, positive/negative predictive values, and accuracy were calculated using R-studio v.3.6.0. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare the two groups. The correlation between the Ct-values of the two techniques was determined using the two-tailed Pearson's correlation coefficient using STATA v17(stata Corp LP, college Station, TX, USA). A p-value of less than 0.05 indicated statistical significance. The Ct values were grouped based on viral load (Ct <20, 20-35, and >35), and performance characteristics in each group were compared.

4. Discussion

In this study we tested the EFHD method in comparision with the standard extraction based SARS-CoV-2 detection method. It was found that the EFHD method has showed high sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values specially when the viral load of SARS-CoV-2 are higher. In addition, the new method has better agreement and correlation with the reference method. However, the mean cycle threshold values for the new method were skightly higher but generally comparable to the gold standard method. The findings suggested that the EFHD method is particularly reliable for detecting SARS-CoV-2 in case with a higher varal load. Despite some limitations in samples with low viral loads or higher Ct values, the new method demonstrated overall high accuracy and closely aligned with the results of the extraction based method, indicating a strong performance and reliability.

In this study, the performance of the new diagnostic methods showed comparable diagnostic capability with the standard method. It had good sensitivity and specificity. This finding align with a study conducted in India, which reported an over all sensitivity of 79% (95% CI: 71%-86%) and specificity of 99% (95% CI: 98%-100% [

30]. Another study on extraction-free, multiplexed amplification of SARS-CoV-2 demonstrated a sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 100% [

31]. Similarly, a study conducted at the Karolinska University Hospital in Stockholm, Sweden in 2020, using a heating technique at 95°C for 5 minutes, reported a sensitivity of 96.0% and specificity of 99.8% [

17]. In contrast, a study conducted in India and Italy reported lower overall sensitivity, specifically 78.9% (95% CI 71–86%) and 57.3% (95% CI 47.3–66.8%), respectively. However, both studies reported comparable specificity, specifically 99.9% (95% CI 98–99.6%) and 100% (95% CI 94.4%–100%) [

32].

This study also found that a heightened positive and negative predictive value. Which indicated excellent specificity in identifying true positives, thus enhancing the reliability of the method for confirming the presence of the diseases. However, the findings also highlighted the need for improvement in reducing false negative. This will enhance the method utility in ruling out the diseases. Similar findings were reported in a study conducted in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in 2021. It showed a positive predictive value of 92% and a negative predictive of 91% [

33]. The finding also similar with study done in India in 2021, with a PPV and NPV of 92% amd 97% respectively [

30].

In this study, the overall agreement between extraction-based and EFHD methods was found to be 95%, with a kappa value of 0.89 (p value=0.000). This indicates a high level of reliability in detecting SARS-CoV-2 infections. Similar findings were reported in a study conducted in India, where the agreement was 96.8% (k = 0.83, S.E. = 0.03) [

30]. Additionally, a study conducted in Sweden showed an accuracy of 98.8% (95% confidence interval, CI95: 97.5–99.5%) [

17], while a study in the UAE reported an overall agreement (kappa coefficient) of 0.797 (p < 0:001) [

33]. However, different findings were reported from a study conducted at the clinical laboratory of the Institute Pasteur of M'sila, Algeria, where the overall agreement between extracted and heat-inactivated (65oC for 30 min) samples was only 45%, with a 95% confidence interval of 37 to 52% [

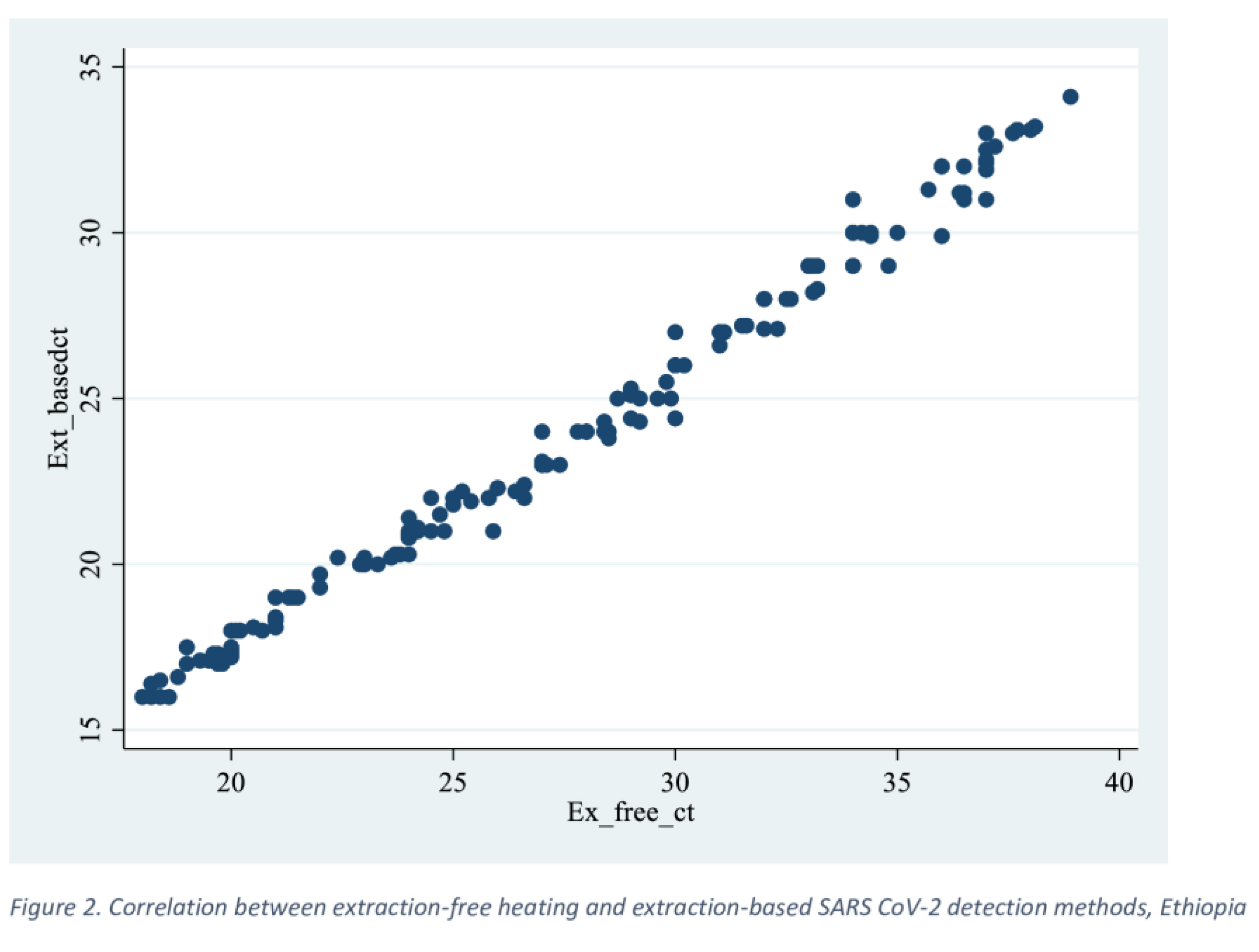

34]. In this study, a near-perfect correlation (R2 = 0.99, p=0.001) was found between extraction-based and extraction-free heating (EFHD) methods, supporting the consistency and reliability of the EFHD method in detecting SARS-CoV-2. These findings are further supported by a study conducted in Singapore (2020), which showed a correlation coefficient (R2) of 0.9986 for the detection of SARS CoV-2 without extraction. Similar results were reported from the Karolinska University Hospital in Stockholm, Sweden, with a correlation coefficient of 0.987 [

17].

The consistent findings from various studies utilizing extraction-free method for SARS-CoV-2 detection can be attributed to the method's simplicity, the inherent properties of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, and its validation against established standards. These factors contribute to the method's robustness and reliability in detecting SARS-CoV-2, making it a valuable tool in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic [

35]. Despite the challenges, the overall high performance of the technique supports its continued use in surveillance and outbreak control efforts. However, the potential for false negatives emphasizes the importance of comprehensive testing strategies, including targeted testing of high-risk populations and asymptomatic individuals [

36]. This method's advantages in terms of speed and simplicity, combined with its high sensitivity and specificity, make it a compelling alternative for SARS-CoV-2 detection, especially in resource-limited settings or during rapid response scenarios [

37].

These findings highlight the strengths and limitations of the extraction-based method in detecting SARS-CoV-2 across different viral load statuses. Notably, the method exhibits high sensitivity and specificity in lower Ct values (< 35). However, its performance decreases in the detection of low viral loads, as evidenced by an increased rate of false negatives. A study conducted in Austria to evaluate extraction-free RT-qPCR methods for SARS-CoV-2 diagnostics showed an 8.2% false negative rate for the EFHD method in samples with a Ct value >30 [

38]. Another finding from Algeria on the detection of SARS-CoV-2 using heat inactivation at 65

oC at 30 min correctly identified 100% of clinical samples with a high viral load (Ct value

< 30) [

34]. Accurate detection of SARS-CoV-2, even at high viral loads, is crucial for early case identification, contact tracing, and isolation measures.

Author Contributions

GH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, writing original draft, Writing review & editing. MB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing review & editing. GM: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing review & editing. AT, NY, AG, AA, AK: Investigation, Methodology, Writing review & editing. SA: Analysis, Writing review & editing. ML: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, writing original draft, Writing review & editing.