Submitted:

06 November 2024

Posted:

07 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methodology

Data collection

Results and Discussion

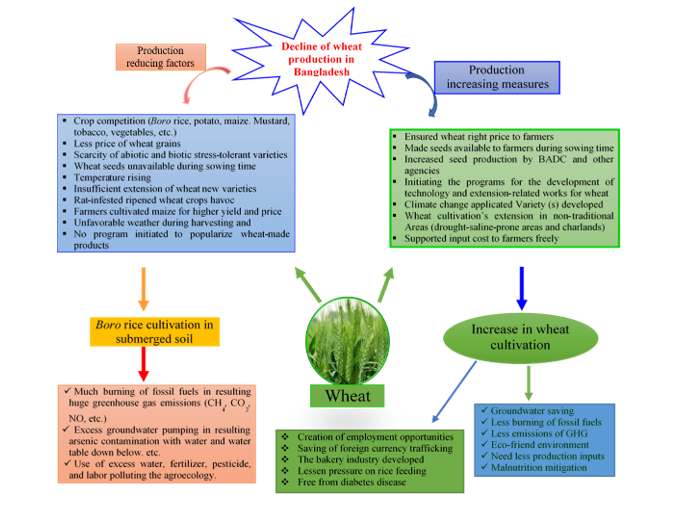

Factors affecting the decline of wheat production

High competition among crops during the wheat cultivation season

Less profitable of wheat cultivation

The revolution of Boro rice cultivation because of an unprecedented increase in irrigation facilities

Temperature rise because of global warming affecting wheat production

Lack of varieties grown for combating heat, drought, salinity, and biotic stresses

Insufficient extension of newly released wheat varieties to farmers

Recently, maize has been popularized among farmers as a high-economic crop

Unfavorable weather during the wheat harvesting period

Rat havoc during the wheat ripening period

None program initiation for popularizing wheat-made food to the people

Possible solutions to the increase in its production

Ensuring the price of produced wheat to farmers

Ensuring seeds to farmers

Increased seed production by BADC

Application of Genetic Engineering and Molecular Biology to Develop Variety (s) Adaptations to Climate Change

Extension of Wheat Cultivation in non-traditional Areas

Extension of wheat cultivation in drought-prone areas (west- and south-western regions)

Extension of wheat cultivation in charlands

Strengthening wheat cultivation in saline-prone areas mostly requires following during the Rabi season

Extension of the recently released varieties

Means of the increase of wheat production supporting farmers

Recommendations and conclusions

Authors’ contributions

Funding source

Declaration of competing interest

References

- Agrawal, N., Dasaradhi, P.V., Mohmmed, A., Malhotra, P., Bhatnagar, R.K., Mukherjee, S.K. 2003. RNA interference: biology, mechanism, and applications. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67(4), 657-85. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.A., Khan, M.H., Haque, M. 2018. Arsenic contamination in groundwater in Bangladesh: implications and challenges for healthcare policy. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy. 11:251-261. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M., Husain T., Sheikh, A.H., et al., 2006. Phytosociology and structure of Himalayan forests from different climatic zones of Pakistan. Pak. J. Bot. 38(2), 361-383.

- Akhter, M.M., Sabagh, A.E., Alam, M.N., et al., 2017. Determination of seed rate of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) varieties with varying seed size. Sci. J. Crop Sci. 6(3), 161-167. [CrossRef]

- Alam, E., Hridoy, A.E.E., Tusher, S.M.S.H., et al., 2023. Climate change in Bangladesh: Temperature and rainfall climatology of Bangladesh for 1949-2013 and its implication on rice yield. PLoS ONE. 18(10), e0292668. [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.N., Akhter M.M., Hossain, M.M., Mahbubul, S.M. 2013b. Phenological changes of different wheat genotypes (Triticum aestivum L.) in high temperature imposed by late seeding. J. Biodiv. Ental Sci. 3, 83-93.

- Alam, M.N., Akhter, M.M., Hossain, M.M., Rokonuzzaman., 2013c. Performance of different wheat genotypes (Triticum aestivum L.) in heat stress conditions. Int. J. Biosci. 3, 295-306.

- Alam, M.N., Bodruzzaman, M., Hossain, M.M., Sadekuzzaman, M. 2014. Growth performance of spring wheat under heat stress conditions. Int. J. Agron. Agric. Res. 4, 91-103.

- Alam, M.N., Wang, Y., Chan, Z. 2018b. Physiological and biochemical analyses reveal drought tolerance in cool-season tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea) turf grass with the application of melatonin. Crop Past. Sci. 69, 1041-1049. [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.N., Zhang, L., Yang, L., et al., 2018a. Transcriptomic profiling of tall fescue in response to heat stress and improved thermotolerance by melatonin and 24-epibrassinolide. BMC Genom. 19, 224. [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.Z., Carpenter-Boggs, L., Mitra, S., et al., 2017. Effect of Salinity Intrusion on Food Crops, Livestock, and Fish Species at Kalapara Coastal Belt in Bangladesh. J. Food Qual. 2017, 1-23. Article ID 2045157. [CrossRef]

- BBS (Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics). 1999. Yearbook of Agricultural Statistics 2020, Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Statistics and Informatics Division, Ministry of Planning, Agargaon, Dhaka, 1207, Bangladesh.

- BBS (Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics). 2008. Agriculture Census 2008, National Series Volume-1, Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Statistics and Informatics Division, Ministry of Planning, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, Agargaon, Dhaka, 1207, Bangladesh.

- BBS. 2019. Agriculture Census 2019, National Series Volume-1, Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Statistics and Informatics Division, Ministry of Planning, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, Agargaon, Dhaka, 1207, Bangladesh.

- BBS. 2020. Yearbook of Agricultural Statistics 2020, Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Statistics and Informatics Division, Ministry of Planning, Agargaon, Dhaka, 1207, Bangladesh.

- BBS. 2021. Statistical Yearbook Bangladesh 2021, Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Statistics and Informatics Division, Ministry of Planning, Agargaon, Dhaka, 1207, Bangladesh.

- BBS. 2022a. Foreign exchange BDT vs USD (1982-2022), Bangladesh Bank. Statistical Yearbook Bangladesh 2022, Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Statistics and Informatics Division, Ministry of Planning, Agargaon, Dhaka-1207, Bangladesh. p.374.

- BBS. 2022b. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (34th Series), Statistics and Informatics Division, Ministry of Planning, Agargaon, Dhaka-1207, Bangladesh, p. 374.

- BBS. 2023. Foreign Trade Statistics of Bangladesh 2022-23, Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Statistics and Informatics Division, Ministry of Planning, Agargaon, Dhaka, 1207, Bangladesh.

- BBS. 2024. Foreign Trade Statistics of Bangladesh 2023-24, Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Statistics and Informatics Division, Ministry of Planning, Agargaon, Dhaka, 1207, Bangladesh.

- BER (Bangladesh Economic Review). 2024. Bangladesh Economic Review, Chapter 7: Agriculture. https://mof.gov.bd/site/page/44e399b3-d378-41aa-86ff-8c4277eb0990/BangladeshEconomicReview.

- BMD (Bangladesh Meteorological Department). 2022. Government of The People's Republic of Bangladesh, Bangladesh Meteorological Department (Climate Division), Meteorological Complex, E-24 Agargaon, Dhaka-1207. Link: https://dataportal.bmd.gov.bd/ (Accessed 3 March 2024.

- BMD (Bangladesh Meteorological Department). 2024. Government of The People's Republic of Bangladesh, Bangladesh Meteorological Department (Climate Division), Meteorological Complex, E-24 Agargaon, Dhaka, 1207. https://dataportal.bmd.gov.bd/, (Accessed 3 March 2024.

- BWMRI (Bangladesh Wheat and Maize Research Institute). 2023. BWMRI Annual Research Report 2021-22, in: Sarker, M, A, Z, Ahmed, S.A., Akhter, M.M., et al. 2023 (Eds.) Nashipur, Dinajpur, October, 2022.

- BWMRI. 2023. BWMRI Annual Report 2022-23, in: Sarker, M, A, Z, Ahmed, S.A., Akhter, M.M., et al. 2023 (Eds.). Nashipur, Dinajpur, Bangladesh (Accessed 19 September 2023).

- BWMRI. 2024. Bangladesh Wheat and Maize Research Institute, Nashipur, Dinajpur, 5200. link: https://bwmri.gov.bd/ (Accessed 27 July 2024).

- Chowdhury MAB, Islam M, Rahman J, Uddin MJ, Haque MR. 2022. Diabetes among adults in Bangladesh: changes in prevalence and risk factors between two cross-sectional surveys. BMJ Open. 4;12(8):e055044. [CrossRef]

- Concern. 2024. Char development and Institutional structure at the National Parliament, 2018.

- DAE (Department of Agricultural Extension). 2023. Annual Report 2022-23, Department of Agricultural Extension, Ministry of Planning, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, Khamarbari, Farmgate, Dhaka, 1215, Bangladesh.

- DAE (Department of Agricultural Extension). 2024. Annual Report 2023-24, Department of Agricultural Extension, Ministry of Planning, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, Khamarbari, Farmgate, Dhaka, 1215, Bangladesh.

- DAM (Department of Agricultural Marketing). 2024. Annual Report 2023-24, The Ministry of Agriculture, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, Farmgate, Dhaka, 1215, Bangladesh.

- DAM (Department of Agricultural Marketing). 2024. Monthly Report, February 2024, The Ministry of Agriculture, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, Farmgate, Dhaka, 1215, Bangladesh.

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization). 2015. FAOSTAT. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Rome. Available at: http://faostat3.fao.org.

- FAO. 2023. GIEWS Country Brief: Bangladesh, Food and Agriculture Organization, 10 Nov 2023.

- IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). 2018. Summary for Policymakers. In: Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [Masson-Delmotte V.P. Zhai H.-O. et al. (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 3-24. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T., Croll, D., Gladieux, P. et al. 2016. The emergence of wheat blast in Bangladesh was caused by a South American lineage of Magnaporthe oryzae. BMC Biol, 14, 84. [CrossRef]

- Khatun, M.A., Rashid, M.B., Hygen, O.H., 2016. Climate of Bangladesh, MET report, no. 08/2016, ISSN 2387-4201, Climate, Norwegian Meteorological Institute.

- Nahar, Q., Choudhury, S., Faruque, M.O., Sultana, S.S.S., Siddiquee, M.A. 2013. Dietary Guidelines for Bangladesh (DGB). National Food Policy Capacity Strengthening Programme. BIRDEM, Dhaka, June 2013.

- Nasim, M., Shahidullah, S., Saha, A., et al. 2018. Distribution of Crops and Cropping Patterns in Bangladesh. Bangladesh Rice Journal, 21(2), 1-55. [CrossRef]

- NCA (National Char Alliance). 2024. The National Char Alliance is a macro-level advocacy platform comprising various stakeholders based in Bangladesh. National Char Alliance report. https://www.concern.net/knowledge-hub/national-char-alliance-report (Accessed 5 June 2024).

- Sarker, U.K., Monira, S., Uddin, M.R. 2012. On-farm evaluation and system productivity of wheat-jute-t. aman rice cropping pattern in the charred area of Bangladesh. Agric Sci, 2, 39-46.

- Shahid, S., Behrawan, H. 2008. Drought risk assessment in the western part of Bangladesh. Natural Hazards, 46(3), 391-413. [CrossRef]

- Shahidullah, S.M., Talukder, M.S.A., Kabir, M.S. 2006. Cropping Patterns in the South East Coastal Region of Bangladesh, J. Agric. Rural Dev. 4(1&2), 53-60. [CrossRef]

- Singh, P., K., Gahtyari, N.C., Roy, C. et al. 2021. Wheat Blast: A Disease Spreading by Intercontinental Jumps and Its Management Strategies. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 710707. [CrossRef]

- SRDI (Soil Resource Development Institute). 2010. SRMAF Project, Soil Resource Development Institute, Ministry of Agriculture. Saline Soils of Bangladesh, Khamar Bari, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

- Sun, L., Wen, J., Peng, H., et al. 2022. The genetic and molecular basis for improving heat stress tolerance in wheat. aBIOTECH, 3, 25-39. [CrossRef]

- USDA (United States Department of Agriculture). 2023. Months data (Jan-Sept) in 2023.

- USDA. 2024. Report Name: Grain and Feed Update. Report Number: BG2023-0024. August 27, 2024.

- WHO (World Health Organnizaion). 2024. Healthy Diet. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet (Accessed 31 Oct 2024).

- Worlodmeter. 2024. https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/bangladesh-population/ (Accessed 12 June 2024).

- WPR (World Population Review). 2024. Rice Consumption by Country 2024. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/rice-consumption-by-country, (Accessed 31 October 2024).

- Zaman, R., Malaker, P.K., Murad, K.F.I., Sadat, M.A. 2013. TREND analysis of changing temperature in Bangladesh due to global warming. J. Biodiver. Environ. Sci. 3(2), 32-38.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).