Submitted:

07 November 2024

Posted:

08 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

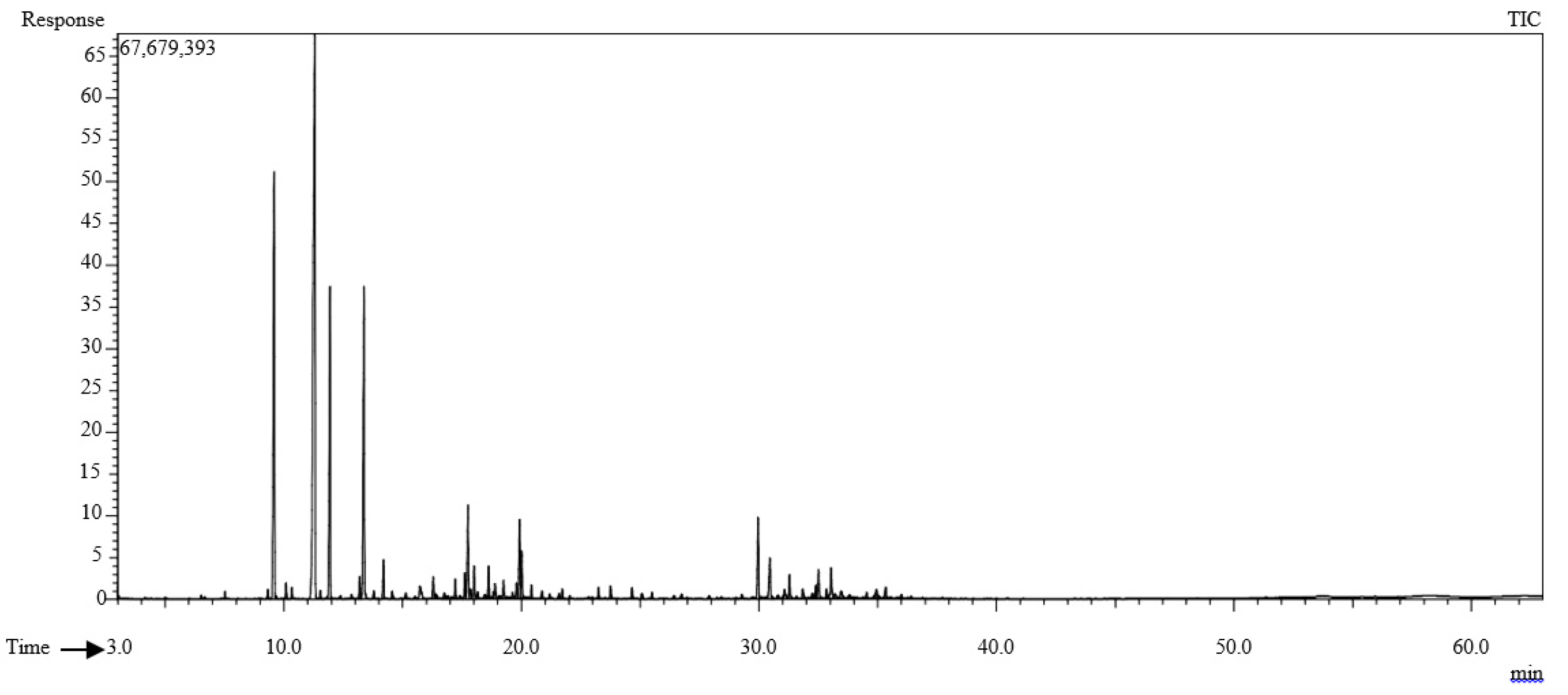

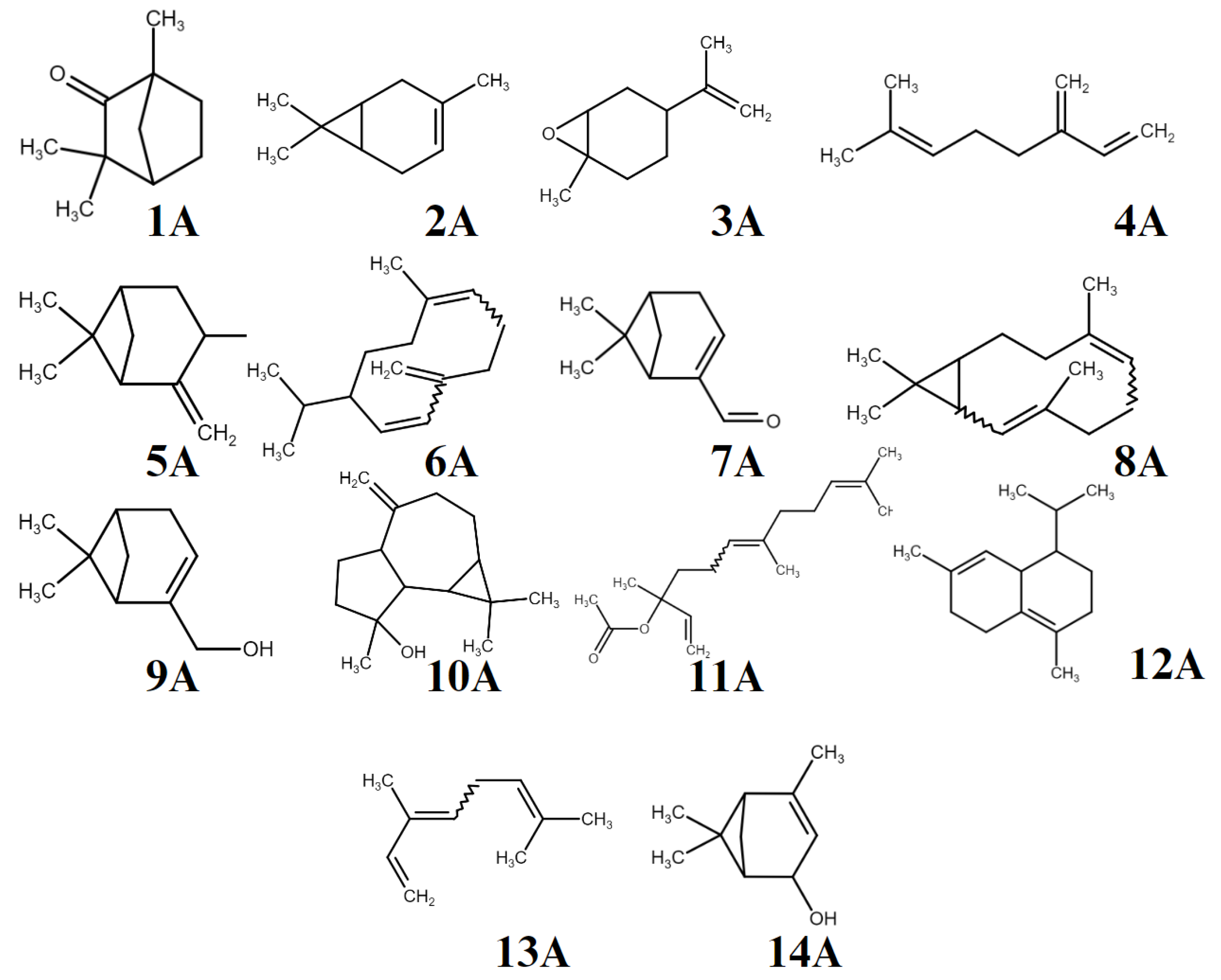

2.1. Characterization of T. polium Essential Oil

2.2. Predictions of Physicochemical, Pharmacokinetic, and Toxicity Aspects

2.3. Predictions of Potential Molecular Targets of Compounds in T. polium Essential Oil

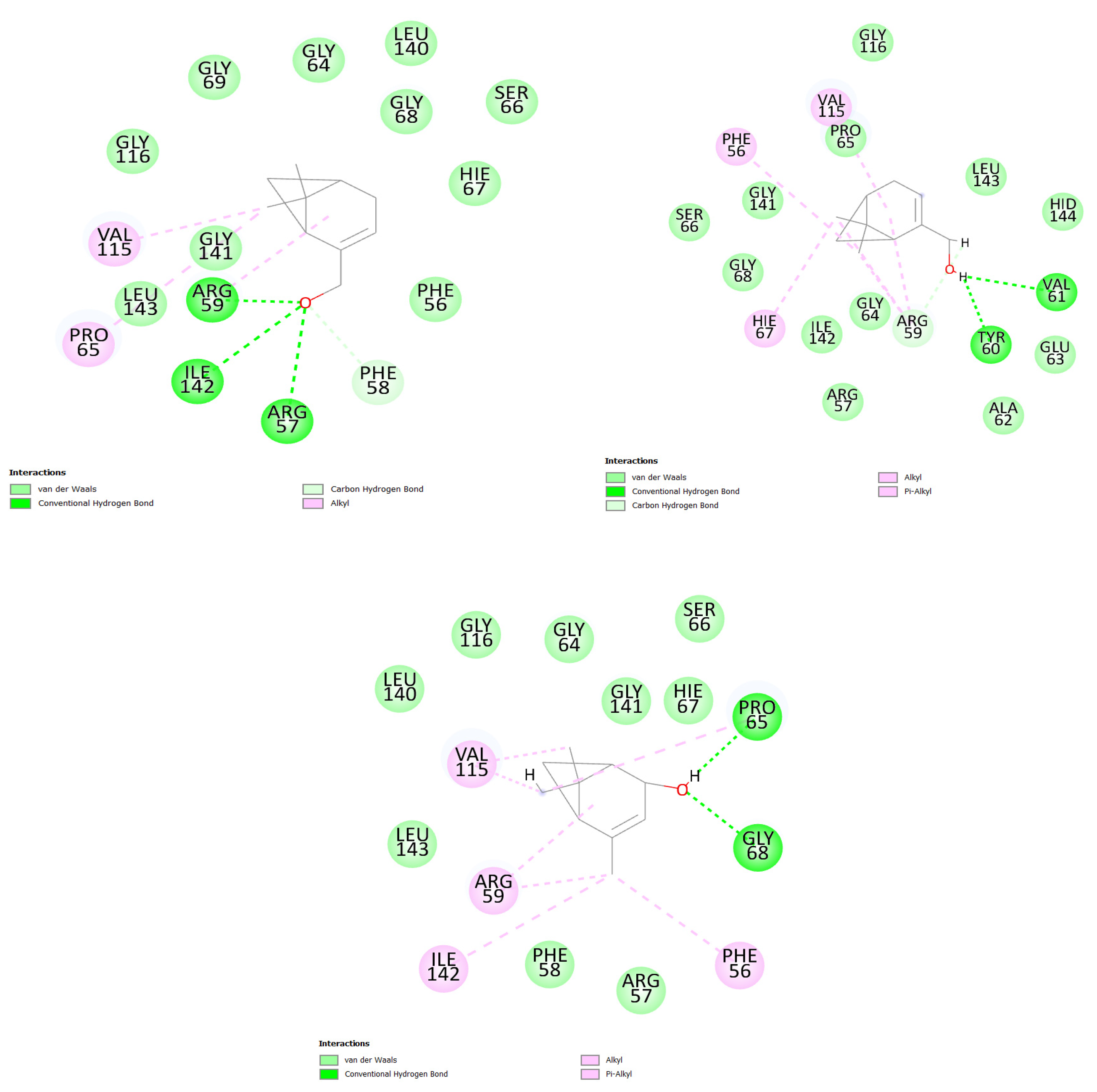

2.3. Docking Molecular Simulation

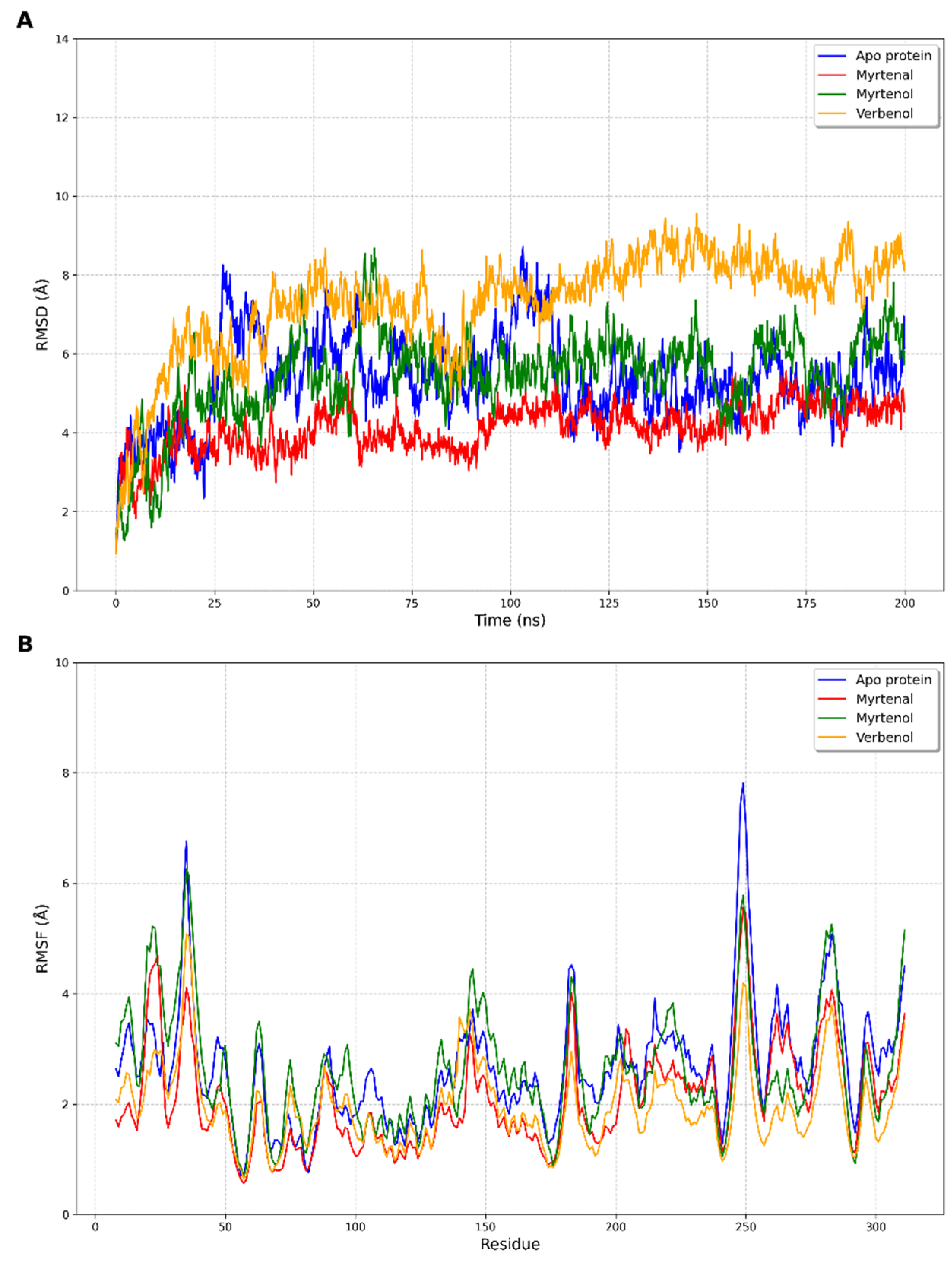

2.4. Molecular Dynamics

2.5. MM-GBSA Binding Energies

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemical Studies

4.1.1. Plant Material, and Extraction of the Essential Oil

4.1.2. Chromatographic Analysis

4.2. In Silico Evaluation

4.3. Molecular Target and Docking

4.4. Molecular Dynamics

4.5. MM-GBSA Binding Free Energy Calculation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdollahi, M.; Karimpour, H.; Monsef-Esfehani, H.R. Antinociceptive Effects of Teucrium Polium L. Total Extract and Essential Oil in Mouse Writhing Test. Pharmacol Res 2003, 48, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahramikia, S.; Yazdanparast, R. Phytochemistry and Medicinal Properties of Teucrium Polium L. (Lamiaceae). Phytotherapy Research 2012, 26, 1581–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahramikia, S.; Hemmati Hassan Gavyar, P.; Yazdanparast, R. Teucrium Polium L: An Updated Review of Phytochemicals and Biological Activities. Avicenna J Phytomed 2022, 12, 224–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vokou, D.; B, Jean-M. Volatile Constituents of Teucrium Polium. J Nat Prod 1985, 48, 498–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezić, N.; Vuko, E.; Dunkić, V.; Ruščić, M.; Blažević, I.; Burčul, F. Antiphytoviral Activity of Sesquiterpene-Rich Essential Oils from Four Croatian Teucrium Species. Molecules 2011, 16, 8119–8129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essid, R.; Rahali, F.Z.; Msaada, K.; Sghair, I.; Hammami, M.; Bouratbine, A.; Aoun, K.; Limam, F. Antileishmanial and Cytotoxic Potential of Essential Oils from Medicinal Plants in Northern Tunisia. Ind Crops Prod 2015, 77, 795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyad, R.; Farahmandfar, R. Influence of Teucrium Polium L. Essential Oil on the Oxidative Stability of Canola Oil during Storage. J Food Sci Technol 2017, 54, 3073–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoudi, S. Volatile Constituents from Different Parts of Three Lamiacea Herbs from Iran. Iran J Pharm Res 2018, 17, 365. [Google Scholar]

- Vahdani, M.; Faridi, P.; Zarshenas, M.M.; Javadpour, S.; Abolhassanzadeh, Z.; Moradi, N.; Bakzadeh, Z.; Karmostaji, A.; Mohagheghzadeh, A.; Ghasemi, Y. Major Compounds and Antimicrobial Activity of Essential Oils from Five Iranian Endemic Medicinal Plants. Pharmacognosy Journal 2011, 3, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djabou, N.; Lorenzi, V.; Guinoiseau, E.; Andreani, S.; Giuliani, M.C.; Desjobert, J.M.; Bolla, J.M.; Costa, J.; Berti, L.; Luciani, A.; et al. Phytochemical Composition of Corsican Teucrium Essential Oils and Antibacterial Activity against Foodborne or Toxi-Infectious Pathogens. Food Control 2013, 30, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, J.; Rehman, N.U.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Ali, L.; Khan, A.L.; Albroumi, M.A. Essential Oil Composition and Nutrient Analysis of Selected Medicinal Plants in Sultanate of Oman. Asian Pac J Trop Dis 2013, 3, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Atki, Y.; Aouam, I.; El kamari, F.; Taroq, A.; Lyoussi, B.; Taleb, M.; Abdellaoui, A. Total Phenolic and Flavonoid Contents and Antioxidant Activities of Extracts from Teucrium Polium Growing Wild in Morocco. Mater Today Proc 2019, 13, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitsiou, E.; Pappa, A. Anticancer Activity of Essential Oils and Other Extracts from Aromatic Plants Grown in Greece. Antioxidants 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebadollahi, A.; Taghinezhad, E. Modeling and Optimization of the Insecticidal Effects of Teucrium Polium L. Essential Oil against Red Flour Beetle (Tribolium Castaneum Herbst) Using Response Surface Methodology. Information Processing in Agriculture 2020, 7, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassel, G.M.; Ahmed, S.S. On the Essential Oil of Teucrium Polium L. 1974.

- Ghiglione, C.; Lemordant, D.; Gast, M. The Chemical Composition of Teucrium Polium Ssp. Cylindricum. Characterization of Alkanes and of Beta-Eudesmol. 1976.

- Cozzani, S.; Muselli, A.; Desjobert, J.-M.; Bernardini, A.-F.; Tomi, F.; Casanova, J. Chemical Composition of Essential Oil of Teucrium Polium Subsp. Capitatum (L.) from Corsica. Flavour Fragr J 2005, 20, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghtader, M.; Salari, H.; Farahmand, A. Anti-Bacterial Effects of the Essential Oil of Teucrium Polium L. on Human Pathogenic Bacteria. on Human Pathogenic Bacteria. Iranian Journal of Medical Microbiology 2013, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Zabihi, N.A.; Mousavi, S.M.; Mahmoudabady, M.; Soukhtanloo, M.; Sohrabi, F.; Niazmand, S. Teucrium Polium L. Improves Blood Glucose and Lipids and Ameliorates Oxidative Stress in Heart and Aorta of Diabetic Rats. Int J Prev Med 2018, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Shaker, B.; Ahmad, S.; Lee, J.; Jung, C.; Na, D. In Silico Methods and Tools for Drug Discovery. Comput Biol Med 2021, 137, 104851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khani, A.; Heydarian, M. Fumigant and Repellent Properties of Sesquiterpene-Rich Essential Oil from Teucrium Polium Subsp. Capitatum (L.). Asian Pac J Trop Med 2014, 7, 956–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Othman, M.; Bel Hadj Salah-Fatnassi, K.; Ncibi, S.; Elaissi, A.; Zourgui, L. Antimicrobial Activity of Essential Oil and Aqueous and Ethanol Extracts of Teucrium Polium L. Subsp. Gabesianum (L.H.) from Tunisia. Physiology and Molecular Biology of Plants 2017, 23, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutchan, T.M. Ecological Arsenal and Developmental Dispatcher. The Paradigm of Secondary Metabolism PLANTS PRODUCE A LARGE NUMBER OF CHEMICALS OF DIVERSE STRUCTURE AND CLASS; 2001; Vol. 125;

- Cakir, A.; Duru, M.E.; Harmandar, M.; Ciriminna, R.; Passannanti, S. Volatile Constituents of Teucrium Polium L. from Turkey. Journal of essential oil Research 1998, 10, 113–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maizi, Y.; Meddah, B.; Tir Touil Meddah, A.; Gabaldon Hernandez, J.A. Seasonal Variation in Essential Oil Content, Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Teucrium Polium L. Growing in Mascara (North West of Algeria). Journal of Applied Biotechnology Reports 2019, 6, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reaisi, Z.; Yadegari, M.; Shirmardia, H.A. Effects of Phenological Stage and Elevation on Phytochemical Characteristics of Essential Oil of Teucrium Polium L. and Teucrium Orientale L. Int J Hortic Sci Technol 2019, 6, 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Sabzeghabaie, A.; Asgarpanah, J. Essential Oil Composition of Teucrium Polium L. Fruits. Journal of EssEntial oil rEsEarch 2016, 28, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulila, A.; Béjaoui, A.; Messaoud, C.; Boussaid, M. Variation of Volatiles in Tunisian Populations of Teucrium Polium L.(Lamiaceae). Chem Biodivers 2008, 5, 1389–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, H.; Jamalpoor, S.; Shirzadi, M.H. Variability in Essential Oil of Teucrium Polium L. of Different Latitudinal Populations. Ind Crops Prod 2014, 54, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belmekki, N.; Bendimerad, N.; Bekhechi, C.; Fernandez, X. Chemical Analysis and Antimicrobial Activity of Teucrium Polium L. Essential Oil from Western Algeria. J Med Plants Res 2013, 7, 897–902. [Google Scholar]

- Gülsoy Toplan, G.; Göger, F.; Taşkin, T.; Ecevit-Genç, G.; Civaş, A.; Işcan, G.; Kürkçüoğlu, M.; Mat, A.; Başer, K.H.C. Phytochemical Composition and Pharmacological Activities of Teucrium Polium L. Collected from Eastern Turkey. Turk J Chem 2022, 46, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavam, M.; Markabi, F.S. Evaluation of Yield, Chemical Profile, and Antimicrobial Activity of Teucrium Polium L. Essential Oil Used in Iranian Folk Medicine. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2024, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donmez, I.E. Volatile Oil Composition of Teucrium Species of Natural and Cultivated Origin in the Lake District of Turkey. 2022.

- Aburjai, T.; Hudaib, M.; Cavrini, V. Composition of the Essential Oil from Jordanian Germander (Teucrium Polium L.). Journal of Essential Oil Research 2006, 18, 97–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lograda, T.; Messaoud, R.; Chalard, P. Chemical Analysis and Antimicrobial Activity of Teucrium Polium L. Essential Oil from Eastern Algeria. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Catinella, G.; Badalamenti, N.; Ilardi, V.; Rosselli, S.; De Martino, L.; Bruno, M. The Essential Oil Compositions of Three Teucrium Taxa Growing Wild in Sicily: HCA and PCA Analyses. Molecules 2021, 26, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, C.A. Lead-and Drug-like Compounds: The Rule-of-Five Revolution. Drug Discov Today Technol 2004, 1, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolabela, M.F.; Silva, A.R.P. da; Ohashi, L.H.; Bastos, M.L.C.; Silva, M.C.M. da; Vale, V.V. Estudo in Silico Das Atividades de Triterpenos e Iridoides Isolados de Himatanthus Articulatus (Vahl) Woodson. 2018.

- de Barros, R.C.; Araujo da Costa, R.; Farias, S.D.P.; de Albuquerque, K.C.O.; Marinho, A.M.R.; Campos, M.B.; Marinho, P.S.B.; Dolabela, M.F. In Silico Studies on Leishmanicide Activity of Limonoids and Fatty Acids from Carapa Guianensis Aubl. Front Chem 2024, 12, 1394126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathinam, A.; Pari, L. Myrtenal Ameliorates Hyperglycemia by Enhancing GLUT2 through Akt in the Skeletal Muscle and Liver of Diabetic Rats. Chem Biol Interact 2016, 256, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sintim, H.O. Dialkylamino-2, 4-dihydroxybenzoic Acids as Easily Synthesized Analogues of Platensimycin and Platencin with Comparable Antibacterial Properties. Chemistry–A European Journal 2011, 12, 3352–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V Suslov, E.; Yu Ponomarev, K.; D Rogachev, A.; A Pokrovsky, M.; G Pokrovsky, A.; B Pykhtina, M.; B Beklemishev, A.; V Korchagina, D.; P Volcho, K.; F Salakhutdinov, N. Compounds Combining Aminoadamantane and Monoterpene Moieties: Cytotoxicity and Mutagenic Effects. Med Chem (Los Angeles) 2015, 11, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luzina, O.; Filimonov, A.; Zakharenko, A.; Chepanova, A.; Zakharova, O.; Ilina, E.; Dyrkheeva, N.; Likhatskaya, G.; Salakhutdinov, N.; Lavrik, O. Usnic Acid Conjugates with Monoterpenoids as Potent Tyrosyl-DNA Phosphodiesterase 1 Inhibitors. J Nat Prod 2020, 83, 2320–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapitsa, I.G.; Suslov, E. V.; Teplov, G. V.; Korchagina, D. V.; Komarova, N.I.; Volcho, K.P.; Voronina, T.A.; Shevela, A.I.; Salakhutdinov, N.F. Synthesis and Anxiolytic Activity of 2-Aminoadamantane Derivatives Containing Monoterpene Fragments. Pharm Chem J 2012, 46, 263–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li-Zhulanov, N.S.; Zaikova, N.P.; Sari, S.; Gülmez, D.; Sabuncuoğlu, S.; Ozadali-Sari, K.; Arikan-Akdagli, S.; Nefedov, A.A.; Rybalova, T. V.; Volcho, K.P. Rational Design of New Monoterpene-Containing Azoles and Their Antifungal Activity. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomarev, K.; Morozova, E.; Pavlova, A.; Suslov, E.; Korchagina, D.; Nefedov, A.; Tolstikova, T.; Volcho, K.; Salakhutdinov, N. Synthesis and Analgesic Activity of Amines Combining Diazaadamantane and Monoterpene Fragments. Med Chem (Los Angeles) 2017, 13, 773–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liu, B.; Li, L.; He, M.-X.; Zhou, X.-D.; Li, Q. Myrtenol Inhibits Biofilm Formation and Virulence in the Drug-Resistant Acinetobacter Baumannii: Insights into the Molecular Mechanisms. Infect Drug Resist 2022, 5137–5148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Britto, R.M.; da Silva-Neto, J.A.; Mesquita, T.R.R.; de Vasconcelos, C.M.L.; de Almeida, G.K.M.; de Jesus, I.C.G.; Dos Santos, P.H.; Souza, D.S.; Miguel-dos-Santos, R.; de Sá, L.A. Myrtenol Protects against Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury through Antioxidant and Anti-Apoptotic Dependent Mechanisms. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2018, 111, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, I.-Y.; Lim, J.H.; Hwang, S.; Lee, J.-C.; Cho, G.-S.; Kim, W.-K. Anti-Ischemic and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of (S)-Cis-Verbenol. Free Radic Res 2010, 44, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oeckinghaus, A.; Ghosh, S. The NF-ΚB Family of Transcription Factors and Its Regulation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2009, 1, a000034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betzler, A.C.; Theodoraki, M.N.; Schuler, P.J.; Döscher, J.; Laban, S.; Hoffmann, T.K.; Brunner, C. NF-ΚB and Its Role in Checkpoint Control. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, P.; Wang, B.; Zhou, J.; Yang, J. Inhibition of Nuclear Factor Kappa B as a Therapeutic Target for Lung Cancer. Altern Ther Health Med 2022, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Ersoy, E.; Süvari, G.; Ercan, S.; Eroğlu Özkan, E.; Karahan, S.; Aygün Tuncay, E.; Yeşil Cantürk, Y.; Mataracı Kara, E.; Zengin, G.; Boğa, M. Towards a Better Understanding of Commonly Used Medicinal Plants from Turkiye: Detailed Phytochemical Screening and Biological Activity Studies of Two Teucrium L. Species with in Vitro and in Silico Approach. J Ethnopharmacol 2023, 312, 116482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabane, S.; Boudjelal, A.; Napoli, E.; Benkhaled, A.; Ruberto, G. Phytochemical Composition, Antioxidant and Wound Healing Activities of Teucrium Polium Subsp. Capitatum (L.) Briq. Essential Oil. Journal of Essential Oil Research 2021, 33, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Naemi, H.A.; Alasmar, R.M.; Al-Ghanim, K. Alcoholic Extracts of Teucrium Polium Exhibit Remarkable Anti-Inflammatory Activity: In Vivo Study. Biomolecules and Biomedicine 2024, 24, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Yang, X.; Gao, Y.; Li, M.; Yang, H.; Liu, T.; Tang, H. Chronic Inflammation, Cancer Development and Immunotherapy. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, T.; Myo Zaw, S.Y.; Sueyama, Y.; Katsube, K. ichi; Kaneko, R.; Nör, J.E.; Okiji, T. Inhibition of Nuclear Factor Kappa B Prevents the Development of Experimental Periapical Lesions. J Endod 2019, 45, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, K.S.; Fuloria, N.K.; Fuloria, S.; Rahman, S.B.; Al-Malki, W.H.; Javed Shaikh, M.A.; Thangavelu, L.; Singh, S.K.; Rama Raju Allam, V.S.; Jha, N.K.; et al. Nuclear Factor-Kappa B and Its Role in Inflammatory Lung Disease. Chem Biol Interact 2021, 345, 109568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLafferty, F.W.; Stauffer, D.B.; Stenhagen, E.; Heller, S.R. The Wiley/NBS Registry of Mass Spectral Data. (No Title), 1989. [Google Scholar]

- PJ, L. NIST Standard Reference Database Number 69. NIST Chemistry WebBook 2003.

- Dong, J.; Wang, N.-N.; Yao, Z.-J.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, Y.; Ouyang, D.; Lu, A.-P.; Cao, D.-S. ADMETlab: A Platform for Systematic ADMET Evaluation Based on a Comprehensively Collected ADMET Database. J Cheminform 2018, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.R.; Olivi, P.; Botta, C.M.R.; Espindola, E.L.G. A Toxicidade Em Ambientes Aquáticos: Discussão e Métodos de Avaliação. Quim Nova 2008, 31, 1820–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilhermino, L.; Diamantino, T.; Carolina Silva, M.; Soares, A.M.V.M. Acute Toxicity Test with Daphnia Magna: An Alternative to Mammals in the Prescreening of Chemical Toxicity? Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2000, 46, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucker, E. Hazard Evaluation Division Standard Evaluation Procedure: Acute Toxicity Test for Freshwater Fish; US Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Pesticide Programs, 1985.

- Ames, B.N.; McCann, J.; Yamasaki, E. Methods for Detecting Carcinogens and Mutagens with the Salmonella/Mammalian-Microsome Mutagenicity Test. Mutat. Res.;(Netherlands) 1975, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drwal, M.N.; Banerjee, P.; Dunkel, M.; Wettig, M.R.; Preissner, R. ProTox: A Web Server for the in Silico Prediction of Rodent Oral Toxicity. Nucleic Acids Res 2014, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickel, J.; Gohlke, B.-O.; Erehman, J.; Banerjee, P.; Rong, W.W.; Goede, A.; Dunkel, M.; Preissner, R. SuperPred: Update on Drug Classification and Target Prediction. Nucleic Acids Res 2014, 42, W26–W31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C.W.; Rey, F.A.; Sodeoka, M.; Verdine, G.L.; Harrison, S.C. Structure of the NF-ΚB P50 Homodimer Bound to DNA. Nature 1995, 373, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruch, P.; Teodoro, D.; Consortium, U. Uniprot; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, P.; Sudandiradoss, C. Andrographolide-Based Potential Anti-Inflammatory Transcription Inhibitors against Nuclear Factor NF-Kappa-B P50 Subunit (NF-ΚB P50): An Integrated Molecular and Quantum Mechanical Approach. 3 Biotech 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitencourt-Ferreira, G.; de Azevedo, W.F. Molegro Virtual Docker for Docking. In Docking screens for drug discovery; 2019; pp. 149–167. [Google Scholar]

- Case, D.A.; Aktulga, H.M.; Belfon, K.; Ben-Shalom, I.; Brozell, S.R.; Cerutti, D.S.; Cheatham III, T.E.; Cruzeiro, V.W.D.; Darden, T.A.; Duke, R.E. Amber 2021; University of California: San Francisco, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Frisch, M.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G.A. Gaussian 09, Gaussian. Inc., Wallingford CT 2009, 121, 150–166. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wolf, R.M.; Caldwell, J.W.; Kollman, P.A.; Case, D.A. Development and Testing of a General Amber Force Field. J Comput Chem 2004, 25, 1157–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, J.A.; Martinez, C.; Kasavajhala, K.; Wickstrom, L.; Hauser, K.E.; Simmerling, C. Ff14SB: Improving the Accuracy of Protein Side Chain and Backbone Parameters from Ff99SB. J Chem Theory Comput 2015, 11, 3696–3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolinsky, T.J.; Czodrowski, P.; Li, H.; Nielsen, J.E.; Jensen, J.H.; Klebe, G.; Baker, N.A. PDB2PQR: Expanding and Upgrading Automated Preparation of Biomolecular Structures for Molecular Simulations. Nucleic Acids Res 2007, 35, W522–W525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, W.L.; Chandrasekhar, J.; Madura, J.D.; Impey, R.W.; Klein, M.L. Comparison of Simple Potential Functions for Simulating Liquid Water. J Chem Phys 1983, 79, 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darden, T.; York, D.; Pedersen, L. Particle Mesh Ewald: An N⋅ Log (N) Method for Ewald Sums in Large Systems. J Chem Phys 1993, 98, 10089–10092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, D.A.; Aktulga, H.M.; Belfon, K.; Cerutti, D.S.; Cisneros, G.A.; Cruzeiro, V.W.D.; Forouzesh, N.; Giese, T.J.; Götz, A.W.; Gohlke, H. AmberTools. J Chem Inf Model 2023, 63, 6183–6191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genheden, S.; Ryde, U. The MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA Methods to Estimate Ligand-Binding Affinities. Expert Opin Drug Discov 2015, 10, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, R.A.; da Rocha, J.A.P.; Pinheiro, A.S.; Da Costa, A. do S.S.; da Rocha, E.C.M.; Josino, L.P.C.; da Silva Gonçalves, A.; e Lima, A.H.L.; Brasil, D.S.B. In Silico Identification of Novel Allosteric Inhibitors of Dengue Virus NS2B/NS3 Serine Protease. Journal of the Serbian Chemical Society 2022, 87, 693–706. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, Robert P. 2017. “Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry. 5 Online Ed.” Gruver, TX USA: Texensis Publishing.

- Babushok, V.I.; Linstrom, P.J.; Zenkevich, I.G. Retention Indices for Frequently Reported Compounds of Plant Essential Oils. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data 2011, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| RRI | Referencesa,b | Compounds | RA (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 946 | 939-957 | Camphene | 0.40 |

| 2 | 953 | 937-953 | Verbenene | 0.26 |

| 3 | 1008 | 997-1027 | 3-Carene | 15.77 |

| 4 | 1009 | 990-1009 | α-Phellandrene | 0.75 |

| 5 | 1055 | 1059-1087 | Fenchone | 31.25 |

| 6 | 1064 | 1027-1050 | β-Ocimene, (E)- | 1.02 |

| 7 | 1089 | 1089 | p-Cymene | 0.65 |

| 8 | 1122 | 1106-1134 | α-Campholenal | 0.59 |

| 9 | 1132 | 1122-1144 | Limonene oxide, cis- | 9.77 |

| 10 | 1140 | 1140-1175 | Myrcene | 9.15 |

| 11 | 1146 | 1146 | Verbenol | 1.02 |

| 12 | 1150 | 1110-1150 | δ-2-Carene | 0.72 |

| 13 | 1160 | 1121-1158 | Pinocarvone | 0.91 |

| 14 | 1162 | 1147-1176 | Linalool oxide | 0.64 |

| 15 | 1165 | 1134-1165 | cis-Verbenol | 0.36 |

| 16 | 1169 | 1122-1169 | 3-Carene | 0.80 |

| 17 | 1182 | 1182 | cis-Pinocarveol | 2.92 |

| 18 | 1186 | 1159-1191 | α -Terpineol | 0.46 |

| 19 | 1194 | 1169-1200 | Myrtenol | 1.47 |

| 20 | 1195 | 1171-1206 | Myrtenal | 2.31 |

| 21 | 1204 | 1190-1224 | Verbenone | 0.38 |

| 22 | 1235 | 1206-1235 | Carvone | 0.28 |

| 23 | 1254 | 1259-1284 | Bornyl acetate | 0.31 |

| 24 | 1270 | 1270-1302 | Terpinen-4-ol acetate | 0.54 |

| 25 | 1290 | 1290-1316 | Myrtenyl acetate | 0.70 |

| 26 | 1484 | 1458-1491 | Germacrene D | 2.56 |

| 27 | 1500 | 1474-1501 | Bicyclogermacrene | 1.56 |

| 28 | 1521 | 1508-1539 | δ-Cadinene | 1.18 |

| 29 | 1577 | 1562-1590 | Spathulenol | 1.47 |

| 30 | 1640 | 1610-1650 | α-Muurolol, epi- | 0.43 |

| 31 | 1649 | 1649-1686 | α-Bisabolol | 0.34 |

| 32 | 1654 | 1619-1662 | α-Cadinol | 0.35 |

| 33 | 1677 | 1676 | (Z)-Nerolidyl acetate | 1.30 |

| Grouped compounds (%) | ||||

| Monoterpene hydrocarbons | 43,15 | |||

| Oxygenated monoterpenes | 43,74 | |||

| Sesquiterpenes hydrocarbons | 5.73 | |||

| Total identified compounds (%) | 92.62 | |||

| Molecules | MM | LogP | TPSA | nHBA | nHBD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 152.237 | 2.402 | 17.07 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 136.238 | 2.999 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 152.237 | 2.520 | 12.53 | 1 | 0 |

| 4 | 136.238 | 3.475 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 152.237 | 1.970 | 20.23 | 1 | 1 |

| 6 | 204.357 | 4.891 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 150.221 | 2.178 | 17.07 | 1 | 0 |

| 8 | 204.357 | 4.725 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | 152.237 | 1.971 | 20.23 | 1 | 1 |

| 10 | 220.356 | 3.386 | 20.23 | 1 | 1 |

| 11 | 264.409 | 4.967 | 26.30 | 2 | 0 |

| 12 | 204.357 | 4.725 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 |

| 13 | 136.238 | 3.475 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 |

| 14 | 152.237 | 1.970 | 20.23 | 1 | 1 |

| Absorption | Distribution | Metabolism | |||||

| Molecules | MDCK | Caco 2 | HIA | PP | BBB | CYP Inibition | CYP phase 1 |

| 1 | M | M | H | H | M | 2C9,3A4 | 3A4 |

| 2 | H | M | H | H | H | 2C9 | 3A4 |

| 3 | H | M | H | L | M | 2C9,3A4 | W 3A4 |

| 4 | H | M | H | H | H | 2C9,3A4 | 3A4 |

| 5 | M | M | H | L | H | 2C9,3A4 | W 3A4 |

| 6 | M | M | H | H | H | 2C9,2C19 | 3A4 |

| 7 | H | M | H | L | M | 2C9 | W 3A4 |

| 8 | M | M | H | H | H | 2C9 | 3A4 |

| 9 | H | M | H | L | H | 2C9 | W 3A4 |

| 10 | H | M | H | L | H | 2C9,3A4 | 3A4 |

| 11 | M | M | H | H | H | 2C19,2C9,3A4 | 3A4 |

| 12 | M | M | H | H | H | 2C19,2C9 | 3A4 |

| 13 | M | M | H | H | H | 2C19,2C9 | 3A4 |

| 14 | H | M | H | H | H | 2C9 | W 3A4 |

| Molecules | Alga | Daphnia | Medaka fish | Minnow fish | Ames | Carcino Rato/Cam* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | T | NT | VT | VT | TA1535_10RLI | N/P |

| 2 | T | NT | VT | VT | TA100_10RLI | N/P |

| 3 | T | NT | VT | VT | TA1535_10RL; 100_10RLI;1535_NA | P/P |

| 4 | T | T | VT | VT | TA1535_NA | P/N |

| 5 | T | NT | VT | VT | TA100_10RLI; 1535_NA | N/N |

| 6 | T | T | VT | VT | N | P/P |

| 7 | T | NT | VT | VT | TA1535_10RLI; 100_10RLI | N/N |

| 8 | T | T | VT | VT | N | P/P |

| 9 | T | NT | VT | VT | TA1535_10RLI; 100_10RLI | N/N |

| 10 | T | T | VT | VT | N | P/N |

| 11 | T | T | VT | VT | N | P/P |

| 12 | T | T | VT | VT | N | P/P |

| 13 | T | T | VT | VT | N | P/P |

| 14 | T | NT | VT | VT | TA1535_10RLI; TA100_10RLI | N/N |

| Molecules | LD50 (mg/kg) | Toxicity class | Side effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3087 | V | I |

| 2 | 2799 | V | I/T |

| 3 | 1447 | IV | - |

| 4 | 2561 | V | I/T |

| 5 | 1971 | IV | - |

| 6 | 1471 | IV | - |

| 7 | 2448 | V | I |

| 8 | 2766 | V | I/T/M |

| 9 | 1736 | IV | I |

| 10 | 3278 | V | I/T |

| 11 | 5923 | VI | T |

| 12 | 2090 | V | - |

| 13 | 2652 | V | - |

| 14 | 2280 | V | I |

| Molecules | Probability | Prediction accuracy | Target Name | PDB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 91.76% | 96.09% | NF-kappa-B | 1SVC |

| 9 | 96.52% | 96.09% | NF-kappa-B | 1SVC |

| 14 | 92.39% | 96.09% | NF-kappa-B | 1SVC |

| Complex | ΔEvdw | ΔEele | ΔGGB | ∆GSA | ΔGbind |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myrtenal-1SVC | − 8.92 ± 2.99 | − 98.53 ± 8.44 | 81.12 ± 5.85 | − 107.46 ± 7.33 | − 26.33 ± 3.57 |

| Myrtenol-1SVC | − 5.59 ± 2.89 | − 58.77 ± 8.62 | 40.73 ± 5.94 | − 58.37 ± 7.47 | − 17.64 ± 3.65 |

| Verbenol-1SVC | − 17.01 ± 2.59 | − 81.45 ± 8.51 | 76.32 ± 7.24 | − 98.46 ± 8.28 | − 22.14 ± 3.36 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).