Submitted:

13 November 2024

Posted:

13 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

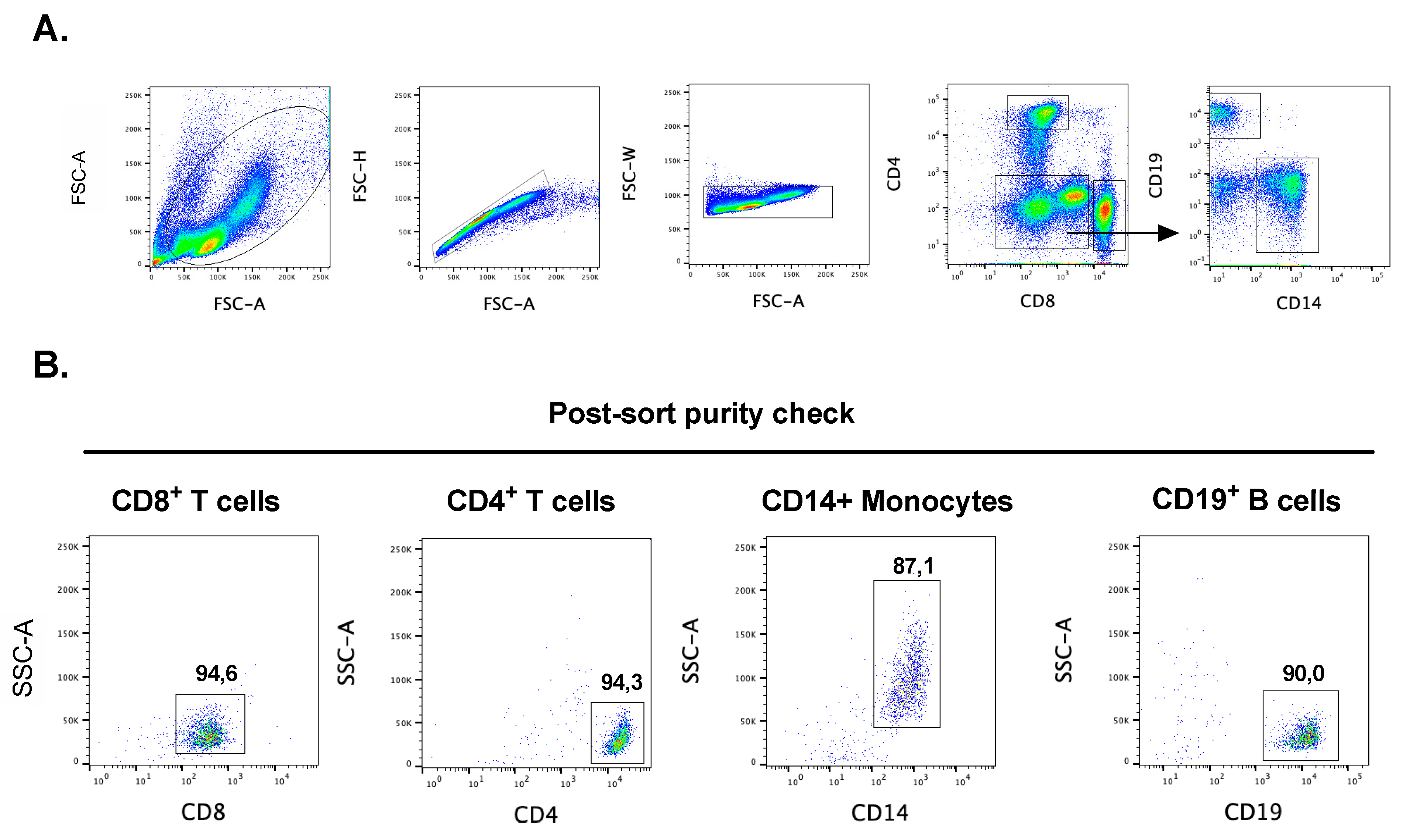

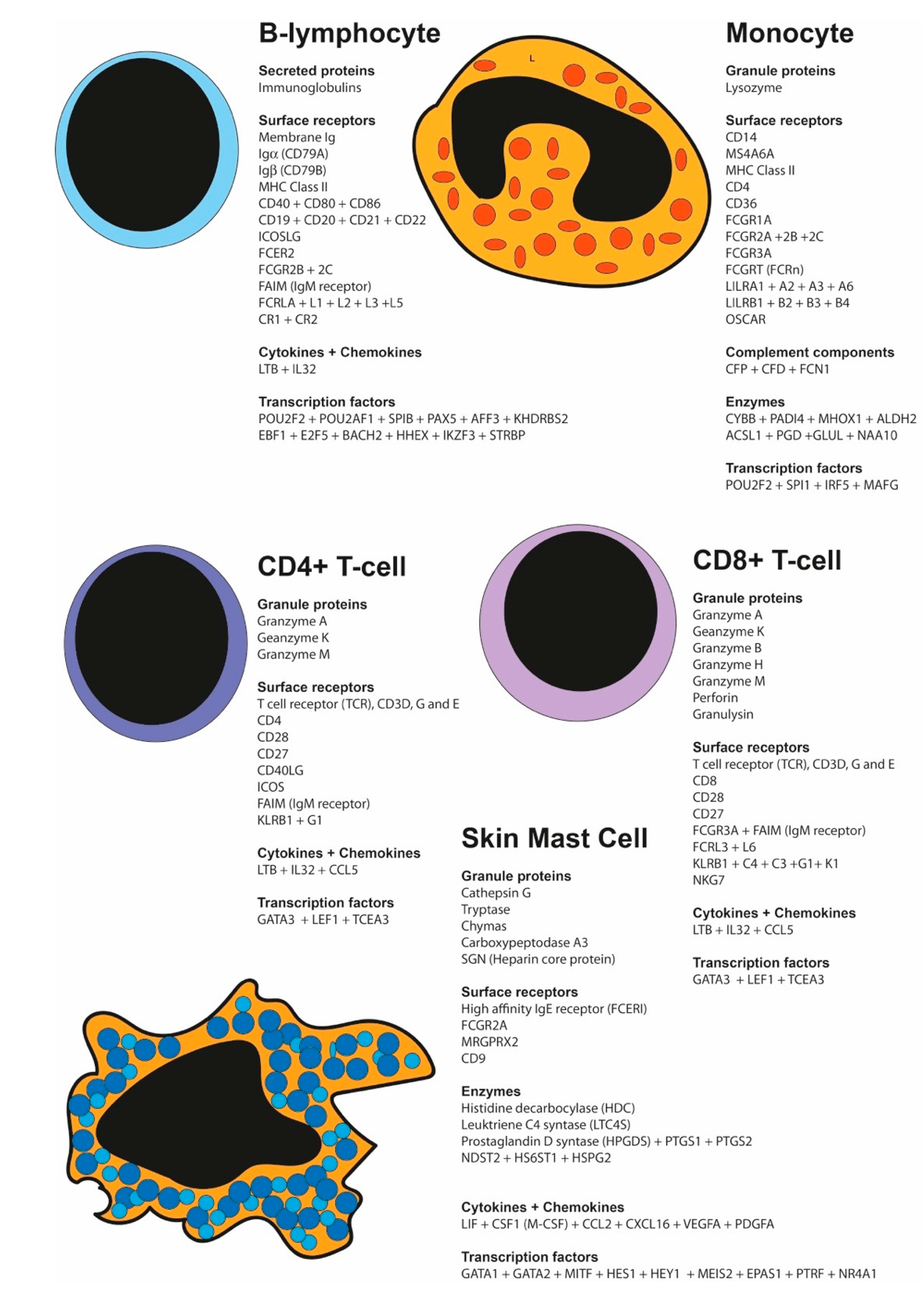

2.1. Purification of Human CD19+ B-Cells, CD14+Monocytes, CD4+ and CD8+ T Cells and Skin MCs

2.2. The Major Granule Proteases Are Mainly Expressed in MCs and T-Cells

2.3. Transcript Levels for the Lysosomal Proteases, the Matrix Proteases and a Few Other Proteases

2.4. Transcript Levels for a Panel of Protease Inhibitors

2.5. Transcript Levels for Eosinophil, Neutrophil and Macrophage Related Proteins

2.6. Transcript Levels for a Panel of Cell Surface Receptors Used as Markers of Immune Cell Populations

2.7. Transcript Levels for the Major Histocompatibility Related Genes (MHC)

2.8. Transcript Levels for Fc-Receptors

2.9. Transcript Levels for Leukocyte Immunoglobulin-like Receptors (LILRs) and Killer Cell Lectin-like Receptors (KLRs)

2.10. Transcript Levels for Complement Components and Receptors

2.11. Transcript Levels for Toll-like Receptors (TLRs) and Other Pattern Recognition Receptors

2.12. Transcript Levels for Histamine, Leukotriene and Prostaglandin Synthesis Enzymes

2.13. Transcript Levels for Proteoglycan Synthesis and Other Carbohydrate Related Proteins

2.14. Transcript Levels for Other Enzymes

2.15. Transcript Levels for Transcription Factors

2.16. Transcript Levels for SOX Members of Regulators of Tissue Development

2.17. Transcript Levels for STATs

2.18. Transcript Levels for Cytokines, Chemokines and Other Growth and Differentiation Factors

2.19. Transcript Levels for Cytokine Induced Proteins

2.20. Transcript Levels for the Major Cytokine and Chemokine Receptors

2.21. Transcript Levels for Other Receptors

2.22. Transcript Levels for Calcium, Chloride and Potassium Channels and Transporters

2.23. Transcript Levels for Angiogenesis Inhibitors and Promoters

2.24. Transcript Levels for the Sialic Acid-Binding Ig-Lectin Family Members (Siglecs)

2.25. Transcript Levels for S100 Proteins

2.26. Transcript Levels for Cell Adhesion Molecules and Other Membrane Proteins

2.27. Transcript Levels for Cell Signaling Proteins

2.28. Transcript Levels for Apoptosis-Related Proteins

2.29. Transcript Levels for Matrix Proteins

2.30. Transcript Levels for Solute Carriers

2.31. Transcript Levels for Cell Cycle and Immediate-Early Response Related Proteins

2.32. Transcript Levels for Nuclear Proteins and Splicing Factors

2.33. Transcript Levels for Cytoskeleton Related Proteins

2.34. Transcript Levels for Vesicle and Protein Transport

2.35. Transcript Levels for Endogenous Retroviruses and Oncogenes

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Purification of Human Peripheral Blood B Cells, Monocytes, and CD4+ and CD8+ T Cells by FACS Sorting

3.2. Purification of Human Skin MCs

3.3. RNA Isolation and Heparinase Treatment of Human MCs

3.4. Ampliseq Analysis of the Total Transcriptome

3.5. Quantitative Transcriptome Analysis

4. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

| MC | mast cell; CPA3, carboxypeptidase A3. |

References

- Li Z, Liu S, Xu J, Zhang X, Han D, Liu J, et al. Adult Connective Tissue-Resident Mast Cells Originate from Late Erythro-Myeloid Progenitors. Immunity. 2018;49(4):640-53 e5. [CrossRef]

- Gentek R, Ghigo C, Hoeffel G, Bulle MJ, Msallam R, Gautier G, et al. Hemogenic Endothelial Fate Mapping Reveals Dual Developmental Origin of Mast Cells. Immunity. 2018;48(6):1160-71 e5. [CrossRef]

- Babina M, Guhl S, Starke A, Kirchhof L, Zuberbier T, Henz BM. Comparative cytokine profile of human skin mast cells from two compartments--strong resemblance with monocytes at baseline but induction of IL-5 by IL-4 priming. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75(2):244-52. [CrossRef]

- Guhl S, Neou A, Artuc M, Zuberbier T, Babina M. Skin mast cells develop non-synchronized changes in typical lineage characteristics upon culture. Exp Dermatol. 2014;23(12):933-5. [CrossRef]

- Babina M, Wang Z, Franke K, Guhl S, Artuc M, Zuberbier T. Yin-Yang of IL-33 in Human Skin Mast Cells: Reduced Degranulation, but Augmented Histamine Synthesis through p38 Activation. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2019;139(7):1516-25 e3. [CrossRef]

- Akula, S.; Tripathi, S.R.; Franke, K.; Wernersson, S.; Babina, M.; Hellman, L. Cultures of Human Skin Mast Cells, an Attractive In Vitro Model for Studies of Human Mast Cell Biology. Cells 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, L.B.; Irani, A.M.; Roller, K.; Castells, M.C.; Schechter, N.M. Quantitation of histamine, tryptase, and chymase in dispersed human T and TC mast cells. J Immunol 1987, 138, 2611–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jogie-Brahim, S.; Min, H.K.; Fukuoka, Y.; Xia, H.Z.; Schwartz, L.B. Expression of alpha-tryptase and beta-tryptase by human basophils. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004, 113, 1086–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellman, L.; Thorpe, M. Granule proteases of hematopoietic cells, a family of versatile inflammatory mediators - an update on their cleavage specificity, in vivo substrates, and evolution. Biol Chem 2014, 395, 15–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poorafshar, M.; Helmby, H.; Troye-Blomberg, M.; Hellman, L. MMCP-8, the first lineage-specific differentiation marker for mouse basophils. Elevated numbers of potent IL-4-producing and MMCP-8-positive cells in spleens of malaria-infected mice. Eur J Immunol 2000, 30, 2660–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iki, M.; Tanaka, K.; Deki, H.; Fujimaki, M.; Sato, S.; Yoshikawa, S.; Yamanishi, Y.; Karasuyama, H. Basophil tryptase mMCP-11 plays a crucial role in IgE-mediated, delayed-onset allergic inflammation in mice. Blood 2016, 128, 2909–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, N.; Watford, W.T.; Ramos, H.L.; Hellman, L.; Oettgen, H.C.; Gomez, G.; Ryan, J.J.; O'Shea, J.J.; Rivera, J. Lyn kinase controls basophil GATA-3 transcription factor expression and induction of Th2 cell differentiation. Immunity 2009, 30, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugajin, T.; Kojima, T.; Mukai, K.; Obata, K.; Kawano, Y.; Minegishi, Y.; Eishi, Y.; Yokozeki, H.; Karasuyama, H. Basophils preferentially express mouse Mast Cell Protease 11 among the mast cell tryptase family in contrast to mast cells. J Leukoc Biol 2009, 86, 1417–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Thorpe, M.; Alemayehu, R.; Roy, A.; Kervinen, J.; de Garavilla, L.; Abrink, M.; Hellman, L. Highly Selective Cleavage of Cytokines and Chemokines by the Human Mast Cell Chymase and Neutrophil Cathepsin G. J Immunol 2017, 198, 1474–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Akula, S.; Thorpe, M.; Hellman, L. Highly Selective Cleavage of TH2-Promoting Cytokines by the Human and the Mouse Mast Cell Tryptases, Indicating a Potent Negative Feedback Loop on TH2 Immunity. International journal of molecular sciences 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Akula, S.; Olsson, A.K.; Kervinen, J.; Hellman, L. Mast Cells and Basophils in the Defense against Ectoparasites: Efficient Degradation of Parasite Anticoagulants by the Connective Tissue Mast Cell Chymases. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellman, L.; Akula, S.; Fu, Z.; Wernersson, S. Mast Cell and Basophil Granule Proteases - In Vivo Targets and Function. Frontiers in immunology 2022, 13, 918305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akula, S.; Fu, Z.; Wernersson, S.; Hellman, L. The Evolutionary History of the Chymase Locus -a Locus Encoding Several of the Major Hematopoietic Serine Proteases. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lara, S.; Akula, S.; Fu, Z.; Olsson, A.K.; Kleinau, S.; Hellman, L. The Human Monocyte-A Circulating Sensor of Infection and a Potent and Rapid Inducer of Inflammation. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aybay, E.; Ryu, J.; Fu, Z.; Akula, S.; Enriquez, E.M.; Hallgren, J.; Wernersson, S.; Olsson, A.K.; Hellman, L. Extended cleavage specificities of human granzymes A and K, two closely related enzymes with conserved but still poorly defined functions in T and NK cell-mediated immunity. Frontiers in immunology 2023, 14, 1211295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akula, S.; Paivandy, A.; Fu, Z.; Thorpe, M.; Pejler, G.; Hellman, L. Quantitative In-Depth Analysis of the Mouse Mast Cell Transcriptome Reveals Organ-Specific Mast Cell Heterogeneity. Cells 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnevers, C.; Smeekens, S.P.; Bromme, D. Human cathepsin W, a putative cysteine protease predominantly expressed in CD8+ T-lymphocytes. FEBS letters 1997, 405, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Grigoryeva, L.; Seyrantepe, V.; Peng, J.; Kollmann, K.; Tremblay, J.; Lavoie, J.L.; Hinek, A.; Lubke, T.; Pshezhetsky, A.V. Serine carboxypeptidase SCPEP1 and Cathepsin A play complementary roles in regulation of vasoconstriction via inactivation of endothelin-1. PLoS Genet 2014, 10, e1004146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basler, M.; Kirk, C.J.; Groettrup, M. The immunoproteasome in antigen processing and other immunological functions. Current opinion in immunology 2013, 25, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishishita, K.; Sakai, E.; Okamoto, K.; Tsukuba, T. Structural and phylogenetic comparison of napsin genes: the duplication, loss of function and human-specific pseudogenization of napsin B. Gene 2013, 517, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentlein, R. Dipeptidyl-peptidase IV (CD26)--role in the inactivation of regulatory peptides. Regul Pept 1999, 85, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esterhazy, D.; Stutzer, I.; Wang, H.; Rechsteiner, M.P.; Beauchamp, J.; Dobeli, H.; Hilpert, H.; Matile, H.; Prummer, M.; Schmidt, A.; et al. Bace2 is a beta cell-enriched protease that regulates pancreatic beta cell function and mass. Cell Metab 2011, 14, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLeo, F.R.; Quinn, M.T. Assembly of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase: molecular interaction of oxidase proteins. J Leukoc Biol 1996, 60, 677–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, M.; Hilarius-Stokman, P.M.; Hossle, J.P.; Verhoeven, A.J.; Graf, N.; Kenney, R.T.; Seger, R.; Roos, D. Autosomal recessive chronic granulomatous disease with absence of the 67-kD cytosolic NADPH oxidase component: identification of mutation and detection of carriers. Blood 1994, 83, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayly-Jones, C.; Pang, S.S.; Spicer, B.A.; Whisstock, J.C.; Dunstone, M.A. Ancient but Not Forgotten: New Insights Into MPEG1, a Macrophage Perforin-Like Immune Effector. Frontiers in immunology 2020, 11, 581906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Py, B.F.; Gonzalez, S.F.; Long, K.; Kim, M.S.; Kim, Y.A.; Zhu, H.; Yao, J.; Degauque, N.; Villet, R.; Ymele-Leki, P.; et al. Cochlin produced by follicular dendritic cells promotes antibacterial innate immunity. Immunity 2013, 38, 1063–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, R.C.; Briggs, J.A.; Ozer, J.; Sealy, L.; Dworkin, L.L.; Kingsmore, S.F.; Seldin, M.F.; Kaur, G.P.; Athwal, R.S.; Dessypris, E.N. The human myeloid cell nuclear differentiation antigen gene is one of at least two related interferon-inducible genes located on chromosome 1q that are expressed specifically in hematopoietic cells. Blood 1994, 83, 2153–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, D.O.; Holodick, N.E.; Rothstein, T.L. Human B1 cells in umbilical cord and adult peripheral blood express the novel phenotype CD20+ CD27+ CD43+ CD70. J Exp Med 2011, 208, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getu, A.A.; Tigabu, A.; Zhou, M.; Lu, J.; Fodstad, O.; Tan, M. New frontiers in immune checkpoint B7-H3 (CD276) research and drug development. Mol Cancer 2023, 22, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, T.N. Stimulating CD27 to quantitatively and qualitatively shape adaptive immunity to cancer. Current opinion in immunology 2017, 45, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchan, S.L.; Rogel, A.; Al-Shamkhani, A. The immunobiology of CD27 and OX40 and their potential as targets for cancer immunotherapy. Blood 2018, 131, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, J.C.; Wang, J.; Mandadi, S.; Tanaka, K.; Roufogalis, B.D.; Madigan, M.C.; Lai, K.; Yan, F.; Chong, B.H.; Stevens, R.L.; et al. Human and mouse mast cells use the tetraspanin CD9 as an alternate interleukin-16 receptor. Blood 2006, 107, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koberle, M.; Kaesler, S.; Kempf, W.; Wolbing, F.; Biedermann, T. Tetraspanins in mast cells. Frontiers in immunology 2012, 3, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.O.; Zhang, X.; Lee, I.Y.; Spencer, N.; Vo, P.; Choi, Y.S. CD9 is a novel marker for plasma cell precursors in human germinal centers. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2013, 431, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orinska, Z.; Hagemann, P.M.; Halova, I.; Draber, P. Tetraspanins in the regulation of mast cell function. Med Microbiol Immunol 2020, 209, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paivandy, A.; Akula, S.; Lara, S.; Fu, Z.; Olsson, A.K.; Kleinau, S.; Pejler, G.; Hellman, L. Quantitative In-Depth Transcriptome Analysis Implicates Peritoneal Macrophages as Important Players in the Complement and Coagulation Systems. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motakis, E.; Guhl, S.; Ishizu, Y.; Itoh, M.; Kawaji, H.; de Hoon, M.; Lassmann, T.; Carninci, P.; Hayashizaki, Y.; Zuberbier, T.; et al. Redefinition of the human mast cell transcriptome by deep-CAGE sequencing. Blood 2014, 123, e58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennathur, S.; Pasichnyk, K.; Bahrami, N.M.; Zeng, L.; Febbraio, M.; Yamaguchi, I.; Okamura, D.M. The macrophage phagocytic receptor CD36 promotes fibrogenic pathways on removal of apoptotic cells during chronic kidney injury. Am J Pathol 2015, 185, 2232–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, J.J.; Hellmich, C.; Moore, J.A.; Jibril, A.; Macaulay, I.; Moreno-Gonzalez, M.; Di Palma, F.; Beraza, N.; Bowles, K.M.; Rushworth, S.A. Free fatty-acid transport via CD36 drives beta-oxidation-mediated hematopoietic stem cell response to infection. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 7130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsy, D.E.; Sanyal, R.; Zaiss, A.K.; Deo, R.; Muruve, D.A.; Deans, J.P. Reduced T-dependent humoral immunity in CD20-deficient mice. J Immunol 2013, 191, 3112–3118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Kiefel, H.; LaJevic, M.D.; Macauley, M.S.; Kawashima, H.; O'Hara, E.; Pan, J.; Paulson, J.C.; Butcher, E.C. Transcriptional programs of lymphoid tissue capillary and high endothelium reveal control mechanisms for lymphocyte homing. Nat Immunol 2014, 15, 982–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parnes, J.R.; Pan, C. CD72, a negative regulator of B-cell responsiveness. Immunol Rev 2000, 176, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosnet, O.; Blanco-Betancourt, C.; Grivel, K.; Richter, K.; Schiff, C. Binding of free immunoglobulin light chains to VpreB3 inhibits their maturation and secretion in chicken B cells. J Biol Chem 2004, 279, 10228–10236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flach, H.; Rosenbaum, M.; Duchniewicz, M.; Kim, S.; Zhang, S.L.; Cahalan, M.D.; Mittler, G.; Grosschedl, R. Mzb1 protein regulates calcium homeostasis, antibody secretion, and integrin activation in innate-like B cells. Immunity 2010, 33, 723–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, D.O.; Rothstein, T.L. Human b1 cell frequency: isolation and analysis of human b1 cells. Frontiers in immunology 2012, 3, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanez-Mo, M.; Barreiro, O.; Gordon-Alonso, M.; Sala-Valdes, M.; Sanchez-Madrid, F. Tetraspanin-enriched microdomains: a functional unit in cell plasma membranes. Trends Cell Biol 2009, 19, 434–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netchiporouk, E.; Moreau, L.; Rahme, E.; Maurer, M.; Lejtenyi, D.; Ben-Shoshan, M. Positive CD63 Basophil Activation Tests Are Common in Children with Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria and Linked to High Disease Activity. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2016, 171, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, S.F.; Ramsdell, F.; Alderson, M.R. The activation antigen CD69. Stem Cells 1994, 12, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, S.F.; Ramsdell, F.; Hjerrild, K.A.; Armitage, R.J.; Grabstein, K.H.; Hennen, K.B.; Farrah, T.; Fanslow, W.C.; Shevach, E.M.; Alderson, M.R. Molecular characterization of the early activation antigen CD69: a type II membrane glycoprotein related to a family of natural killer cell activation antigens. Eur J Immunol 1993, 23, 1643–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, S.; Todd, S.C.; Maecker, H.T. CD81 (TAPA-1): a molecule involved in signal transduction and cell adhesion in the immune system. Annual review of immunology 1998, 16, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, A.; Cella, M.; Giurisato, E.; Shaw, A.S.; Colonna, M. Cutting edge: CD96 (tactile) promotes NK cell-target cell adhesion by interacting with the poliovirus receptor (CD155). J Immunol 2004, 172, 3994–3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leemans, J.C.; te Velde, A.A.; Florquin, S.; Bennink, R.J.; de Bruin, K.; van Lier, R.A.; van der Poll, T.; Hamann, J. The epidermal growth factor-seven transmembrane (EGF-TM7) receptor CD97 is required for neutrophil migration and host defense. J Immunol 2004, 172, 1125–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaer, D.J.; Schaer, C.A.; Buehler, P.W.; Boykins, R.A.; Schoedon, G.; Alayash, A.I.; Schaffner, A. CD163 is the macrophage scavenger receptor for native and chemically modified hemoglobins in the absence of haptoglobin. Blood 2006, 107, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabriek, B.O.; van Bruggen, R.; Deng, D.M.; Ligtenberg, A.J.; Nazmi, K.; Schornagel, K.; Vloet, R.P.; Dijkstra, C.D.; van den Berg, T.K. The macrophage scavenger receptor CD163 functions as an innate immune sensor for bacteria. Blood 2009, 113, 887–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.I.; Hong, M.; Wilson, I.A. An unusual dimeric structure and assembly for TLR4 regulator RP105-MD-1. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2011, 18, 1028–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egli, N.; Zajonz, A.; Burger, M.T.; Schweighoffer, T. Human CD180 Transmits Signals via the PIM-1L Kinase. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0142741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietila, M.; Lehtonen, S.; Tuovinen, E.; Lahteenmaki, K.; Laitinen, S.; Leskela, H.V.; Natynki, A.; Pesala, J.; Nordstrom, K.; Lehenkari, P. CD200 positive human mesenchymal stem cells suppress TNF-alpha secretion from CD200 receptor positive macrophage-like cells. PLoS One 2012, 7, e31671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.A.; McMurray, J.L.; Mohammed, F.; Bicknell, R. C-type lectin domain group 14 proteins in vascular biology, cancer and inflammation. FEBS J 2019, 286, 3299–3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantoni, C.; Bottino, C.; Augugliaro, R.; Morelli, L.; Marcenaro, E.; Castriconi, R.; Vitale, M.; Pende, D.; Sivori, S.; Millo, R.; et al. Molecular and functional characterization of IRp60, a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily that functions as an inhibitory receptor in human NK cells. Eur J Immunol 1999, 29, 3148–3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachelet, I.; Munitz, A.; Moretta, A.; Moretta, L.; Levi-Schaffer, F. The inhibitory receptor IRp60 (CD300a) is expressed and functional on human mast cells. J Immunol 2005, 175, 7989–7995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, O.H.; Tian, L.; Murakami, Y.; Coligan, J.E.; Krzewski, K. Emerging role of CD300 receptors in regulating myeloid cell efferocytosis. Mol Cell Oncol 2015, 2, e964625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braud, V.M.; Allan, D.S.; O'Callaghan, C.A.; Soderstrom, K.; D'Andrea, A.; Ogg, G.S.; Lazetic, S.; Young, N.T.; Bell, J.I.; Phillips, J.H.; et al. HLA-E binds to natural killer cell receptors CD94/NKG2A, B and C. Nature 1998, 391, 795–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinet, J.P. The high-affinity IgE receptor (Fc epsilon RI): from physiology to pathology. Annual review of immunology 1999, 17, 931–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akula, S.; Mohammadamin, S.; Hellman, L. Fc receptors for immunoglobulins and their appearance during vertebrate evolution. PLoS One 2014, 9, e96903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jonsson, F. Expression, Role, and Regulation of Neutrophil Fcgamma Receptors. Frontiers in immunology 2019, 10, 1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhury, C.; Mehnaz, S.; Robinson, J.M.; Hayton, W.L.; Pearl, D.K.; Roopenian, D.C.; Anderson, C.L. The major histocompatibility complex-related Fc receptor for IgG (FcRn) binds albumin and prolongs its lifespan. J Exp Med 2003, 197, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubagawa, H.; Honjo, K.; Ohkura, N.; Sakaguchi, S.; Radbruch, A.; Melchers, F.; Jani, P.K. Functional Roles of the IgM Fc Receptor in the Immune System. Frontiers in immunology 2019, 10, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akula, S.; Hellman, L. The Appearance and Diversification of Receptors for IgM During Vertebrate Evolution. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2017, 408, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.S. Roles for the FCRL6 Immunoreceptor in Tumor Immunology. Frontiers in immunology 2020, 11, 575175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamidi, M.K.; Huang, J.; Honjo, K.; Li, R.; Tabengwa, E.M.; Neeli, I.; Randall, N.L.; Ponnuchetty, M.V.; Radic, M.; Leu, C.M.; et al. FCRL1 immunoregulation in B cell development and malignancy. Frontiers in immunology 2023, 14, 1251127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, K.; Tahara-Hanaoka, S.; Morishima, Y.; Tokunaga, T.; Imoto, Y.; Noguchi, E.; Kanemaru, K.; Imai, M.; Shibayama, S.; Hizawa, N.; et al. Expression and function of Allergin-1 on human primary mast cells. PLoS One 2013, 8, e76160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherwinski, H.M.; Murphy, C.A.; Joyce, B.L.; Bigler, M.E.; Song, Y.S.; Zurawski, S.M.; Moshrefi, M.M.; Gorman, D.M.; Miller, K.L.; Zhang, S.; et al. The CD200 receptor is a novel and potent regulator of murine and human mast cell function. J Immunol 2005, 174, 1348–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Remoortel, S.; Lambeets, L.; De Winter, B.; Dong, X.; Rodriguez Ruiz, J.P.; Kumar-Singh, S.; Martinez, S.I.; Timmermans, J.P. Mrgprb2-dependent Mast Cell Activation Plays a Crucial Role in Acute Colitis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2024, 18, 101391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo-Garcia, S.; Barritt, C.; Papagregoriou, C.; Yeboah, M.; Frendeus, B.; Cragg, M.S.; Roghanian, A. Human leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptors in health and disease. Frontiers in immunology 2023, 14, 1282874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, F.; Coindre, S.; Gardet, M.; Meurisse, F.; Naji, A.; Suganuma, N.; Abi-Rached, L.; Lambotte, O.; Favier, B. Leukocyte Immunoglobulin-Like Receptors in Regulating the Immune Response in Infectious Diseases: A Window of Opportunity to Pathogen Persistence and a Sound Target in Therapeutics. Frontiers in immunology 2021, 12, 717998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirayasu, K.; Saito, F.; Suenaga, T.; Shida, K.; Arase, N.; Oikawa, K.; Yamaoka, T.; Murota, H.; Chibana, H.; Nakagawa, I.; et al. Microbially cleaved immunoglobulins are sensed by the innate immune receptor LILRA2. Nat Microbiol 2016, 1, 16054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merck, E.; Gaillard, C.; Scuiller, M.; Scapini, P.; Cassatella, M.A.; Trinchieri, G.; Bates, E.E. Ligation of the FcR gamma chain-associated human osteoclast-associated receptor enhances the proinflammatory responses of human monocytes and neutrophils. J Immunol 2006, 176, 3149–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raulet, D.H. Roles of the NKG2D immunoreceptor and its ligands. Nat Rev Immunol 2003, 3, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, D.; Mouhtouris, E.; Milland, J.; Zingoni, A.; Santoni, A.; Sandrin, M.S. Recognition of a carbohydrate xenoepitope by human NKRP1A (CD161). Xenotransplantation 2006, 13, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, B.K.; Barahmand-Pour, F.; Paulsene, W.; Medley, S.; Geraghty, D.E.; Strong, R.K. Interactions between NKG2x immunoreceptors and HLA-E ligands display overlapping affinities and thermodynamics. J Immunol 2005, 174, 2878–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Kuroki, K.; Ohki, I.; Sasaki, K.; Kajikawa, M.; Maruyama, T.; Ito, M.; Kameda, Y.; Ikura, M.; Yamamoto, K.; et al. Molecular basis for E-cadherin recognition by killer cell lectin-like receptor G1 (KLRG1). J Biol Chem 2009, 284, 27327–27335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, S.S.; De Labastida Rivera, F.; Yan, J.; Corvino, D.; Das, I.; Zhang, P.; Kuns, R.; Chauhan, S.B.; Hou, J.; Li, X.Y.; et al. The NK cell granule protein NKG7 regulates cytotoxic granule exocytosis and inflammation. Nat Immunol 2020, 21, 1205–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruse, P.H.; Matta, J.; Ugolini, S.; Vivier, E. Natural cytotoxicity receptors and their ligands. Immunol Cell Biol 2014, 92, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Memmer, S.; Weil, S.; Beyer, S.; Zoller, T.; Peters, E.; Hartmann, J.; Steinle, A.; Koch, J. The Stalk Domain of NKp30 Contributes to Ligand Binding and Signaling of a Preassembled NKp30-CD3zeta Complex. J Biol Chem 2016, 291, 25427–25438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdei, A.; Kovacs, K.G.; Nagy-Balo, Z.; Lukacsi, S.; Macsik-Valent, B.; Kurucz, I.; Bajtay, Z. New aspects in the regulation of human B cell functions by complement receptors CR1, CR2, CR3 and CR4. Immunol Lett 2021, 237, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, B.J.; Davis, B.K.; Zhang, J.; O'Connor, W., Jr.; Williams, K.L.; Ting, J.P. CATERPILLER 16.2 (CLR16.2), a novel NBD/LRR family member that negatively regulates T cell function. J Biol Chem 2005, 280, 18375–18385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisse, M.; Ly, H. Comparative Structure and Function Analysis of the RIG-I-Like Receptors: RIG-I and MDA5. Frontiers in immunology 2019, 10, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, H.; Takeuchi, O.; Mikamo-Satoh, E.; Hirai, R.; Kawai, T.; Matsushita, K.; Hiiragi, A.; Dermody, T.S.; Fujita, T.; Akira, S. Length-dependent recognition of double-stranded ribonucleic acids by retinoic acid-inducible gene-I and melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5. J Exp Med 2008, 205, 1601–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zust, R.; Cervantes-Barragan, L.; Habjan, M.; Maier, R.; Neuman, B.W.; Ziebuhr, J.; Szretter, K.J.; Baker, S.C.; Barchet, W.; Diamond, M.S.; et al. Ribose 2'-O-methylation provides a molecular signature for the distinction of self and non-self mRNA dependent on the RNA sensor Mda5. Nat Immunol 2011, 12, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kischkel, F.C.; Lawrence, D.A.; Tinel, A.; LeBlanc, H.; Virmani, A.; Schow, P.; Gazdar, A.; Blenis, J.; Arnott, D.; Ashkenazi, A. Death receptor recruitment of endogenous caspase-10 and apoptosis initiation in the absence of caspase-8. J Biol Chem 2001, 276, 46639–46646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balachandran, S.; Venkataraman, T.; Fisher, P.B.; Barber, G.N. Fas-associated death domain-containing protein-mediated antiviral innate immune signaling involves the regulation of Irf7. J Immunol 2007, 178, 2429–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, M.A.; Gil, J.; Ventoso, I.; Guerra, S.; Domingo, E.; Rivas, C.; Esteban, M. Impact of protein kinase PKR in cell biology: from antiviral to antiproliferative action. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2006, 70, 1032–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, C.; Horner, S.M. MAVS Coordination of Antiviral Innate Immunity. J Virol 2015, 89, 6974–6977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Bernuth, H.; Picard, C.; Jin, Z.; Pankla, R.; Xiao, H.; Ku, C.L.; Chrabieh, M.; Mustapha, I.B.; Ghandil, P.; Camcioglu, Y.; et al. Pyogenic bacterial infections in humans with MyD88 deficiency. Science 2008, 321, 691–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavin, A.L.; Huang, D.; Huber, C.; Martensson, A.; Tardif, V.; Skog, P.D.; Blane, T.R.; Thinnes, T.C.; Osborn, K.; Chong, H.S.; et al. PLD3 and PLD4 are single-stranded acid exonucleases that regulate endosomal nucleic-acid sensing. Nat Immunol 2018, 19, 942–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, R.A.; Brown, G.D. The role of Dectin-1 in the host defence against fungal infections. Curr Opin Microbiol 2011, 14, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtsu, H.; Tanaka, S.; Terui, T.; Hori, Y.; Makabe-Kobayashi, Y.; Pejler, G.; Tchougounova, E.; Hellman, L.; Gertsenstein, M.; Hirasawa, N.; et al. Mice lacking histidine decarboxylase exhibit abnormal mast cells. FEBS letters 2001, 502, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, D.E.; Binda, C.; Mattevi, A. Structural insights into the mechanism of amine oxidation by monoamine oxidases A and B. Arch Biochem Biophys 2007, 464, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babina, M.; Franke, K.; Bal, G. How "Neuronal" Are Human Skin Mast Cells? International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeggstrom, J.Z.; Funk, C.D. Lipoxygenase and leukotriene pathways: biochemistry, biology, and roles in disease. Chem Rev 2011, 111, 5866–5898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakonjac, M.; Fischer, L.; Provost, P.; Werz, O.; Steinhilber, D.; Samuelsson, B.; Radmark, O. Coactosin-like protein supports 5-lipoxygenase enzyme activity and up-regulates leukotriene A4 production. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103, 13150–13155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters-Golden, M.; Brock, T.G. 5-lipoxygenase and FLAP. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 2003, 69, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandy, A.; Jenatschke, S.; Hartung, B.; Milde-Langosch, K.; Bamberger, A.M.; Gellersen, B. Genomic structure and transcriptional regulation of the human NAD+-dependent 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase gene. J Mol Endocrinol 2003, 31, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaoka, Y.; Ago, H.; Inagaki, E.; Nanayama, T.; Miyano, M.; Kikuno, R.; Fujii, Y.; Eguchi, N.; Toh, H.; Urade, Y.; et al. Cloning and crystal structure of hematopoietic prostaglandin D synthase. Cell 1997, 90, 1085–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhle, Y.S. Structure of COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes and their interaction with inhibitors. Drugs Today (Barc) 1999, 35, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, E.A. Diversity of group types, regulation, and function of phospholipase A2. J Biol Chem 1994, 269, 13057–13060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.H.; Kulmacz, R.J. Thromboxane synthase: structure and function of protein and gene. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 2002, 68-69, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, W.; Alrammah, H.; Kiernan, M.; Tonks, A.J.; Jackson, S.K. Lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 2 (LPCAT2) co-localises with TLR4 and regulates macrophage inflammatory gene expression in response to LPS. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 10355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benesch, M.G.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Curtis, J.M.; McMullen, T.P.; Brindley, D.N. Regulation of autotaxin expression and secretion by lysophosphatidate and sphingosine 1-phosphate. J Lipid Res 2015, 56, 1134–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shindou, H.; Shimizu, T. Acyl-CoA:lysophospholipid acyltransferases. J Biol Chem 2009, 284, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallner, B.P.; Mattaliano, R.J.; Hession, C.; Cate, R.L.; Tizard, R.; Sinclair, L.K.; Foeller, C.; Chow, E.P.; Browing, J.L.; Ramachandran, K.L.; et al. Cloning and expression of human lipocortin, a phospholipase A2 inhibitor with potential anti-inflammatory activity. Nature 1986, 320, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angerth, T.; Huang, R.Y.; Aveskogh, M.; Pettersson, I.; Kjellen, L.; Hellman, L. Cloning and structural analysis of a gene encoding a mouse mastocytoma proteoglycan core protein; analysis of its evolutionary relation to three cross hybridizing regions in the mouse genome. Gene 1990, 93, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habuchi, H.; Kobayashi, M.; Kimata, K. Molecular characterization and expression of heparan-sulfate 6-sulfotransferase. Complete cDNA cloning in human and partial cloning in Chinese hamster ovary cells. J Biol Chem 1998, 273, 9208–9213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noonan, D.M.; Fulle, A.; Valente, P.; Cai, S.; Horigan, E.; Sasaki, M.; Yamada, Y.; Hassell, J.R. The complete sequence of perlecan, a basement membrane heparan sulfate proteoglycan, reveals extensive similarity with laminin A chain, low density lipoprotein-receptor, and the neural cell adhesion molecule. J Biol Chem 1991, 266, 22939–22947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, E.P.; Hassan, H.; Mandel, U.; Hollingsworth, M.A.; Akisawa, N.; Ikematsu, Y.; Merkx, G.; van Kessel, A.G.; Olofsson, S.; Clausen, H. Cloning and characterization of a close homologue of human UDP-N-acetyl-alpha-D-galactosamine:Polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase-T3, designated GalNAc-T6. Evidence for genetic but not functional redundancy. J Biol Chem 1999, 274, 25362–25370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, J.; Eriksson, I.; Kjellen, L. Distinct effects on heparan sulfate structure by different active site mutations in NDST-1. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 2110–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsberg, E.; Pejler, G.; Ringvall, M.; Lunderius, C.; Tomasini-Johansson, B.; Kusche-Gullberg, M.; Eriksson, I.; Ledin, J.; Hellman, L.; Kjellen, L. Abnormal mast cells in mice deficient in a heparin-synthesizing enzyme. Nature 1999, 400, 773–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissmann, B.; Chao, H.; Chow, P. A glucosamine O,N-disulfate O-sulfohydrolase with a probable role in mammalian catabolism of heparan sulfate. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1980, 97, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, S.M.; Murphree, M.I.; Mounajjed, T.; El-Youssef, M.; Zhang, L. A novel GBE1 gene variant in a child with glycogen storage disease type IV. Hum Pathol 2016, 54, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, D.J.; Evans, D.M.; Stahl, R.C.; Asundi, V.K.; Conner, K.J.; Garbes, P.; Cizmeci-Smith, G. Molecular cloning and characterization of N-syndecan, a novel transmembrane heparan sulfate proteoglycan. The Journal of cell biology 1992, 117, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpi, S.; Yamazaki, Y.; Brauer, P.M.; van Rooijen, E.; Hayashida, A.; Slavotinek, A.; Sun Kuehn, H.; Di Rocco, M.; Rivolta, C.; Bortolomai, I.; et al. EXTL3 mutations cause skeletal dysplasia, immune deficiency, and developmental delay. J Exp Med 2017, 214, 623–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCormick, C.; Leduc, Y.; Martindale, D.; Mattison, K.; Esford, L.E.; Dyer, A.P.; Tufaro, F. The putative tumour suppressor EXT1 alters the expression of cell-surface heparan sulfate. Nat Genet 1998, 19, 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, S.; Takahashi, K.; Kaneko, T.; Ogasawara, H.; Shindo, S.; Kobayashi, M. Human renin-binding protein is the enzyme N-acetyl-D-glucosamine 2-epimerase. Journal of biochemistry 1999, 125, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, A.; Lensch, M.; Andre, S.; Kaltner, H.; Wiedenmann, B.; Rosewicz, S.; Dignass, A.U.; Gabius, H.J. Human galectin-2: novel inducer of T cell apoptosis with distinct profile of caspase activation. J Immunol 2004, 173, 3825–3837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, J.; Claude-Taupin, A.; Gu, Y.; Choi, S.W.; Peters, R.; Bissa, B.; Mudd, M.H.; Allers, L.; Pallikkuth, S.; Lidke, K.A.; et al. Galectin-3 Coordinates a Cellular System for Lysosomal Repair and Removal. Dev Cell 2020, 52, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotoh, T.; Sonoki, T.; Nagasaki, A.; Terada, K.; Takiguchi, M.; Mori, M. Molecular cloning of cDNA for nonhepatic mitochondrial arginase (arginase II) and comparison of its induction with nitric oxide synthase in a murine macrophage-like cell line. FEBS letters 1996, 395, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama-Hamada, M.; Suzuki, A.; Kubota, K.; Takazawa, T.; Ohsaka, M.; Kawaida, R.; Ono, M.; Kasuya, A.; Furukawa, H.; Yamada, R.; et al. Comparison of enzymatic properties between hPADI2 and hPADI4. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005, 327, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Takeyama, N. Role of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Health and Disease Pathophysiology: Recent Insights and Advances. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Zhang, X.; Nie, L.; Sun, S.; Liu, J.; Chen, H. Heme oxygenase 1 in erythropoiesis: an important regulator beyond catalyzing heme catabolism. Annals of hematology 2023, 102, 1323–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okano, S.; Zhou, L.; Kusaka, T.; Shibata, K.; Shimizu, K.; Gao, X.; Kikuchi, Y.; Togashi, Y.; Hosoya, T.; Takahashi, S.; et al. Indispensable function for embryogenesis, expression and regulation of the nonspecific form of the 5-aminolevulinate synthase gene in mouse. Genes Cells 2010, 15, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, R.D.; Holland, P.J.; Hollis, T.; Perrino, F.W. Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome gene and HIV-1 restriction factor SAMHD1 is a dGTP-regulated deoxynucleotide triphosphohydrolase. J Biol Chem 2011, 286, 43596–43600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Lou, L.; Peng, B.; Song, X.; Reizes, O.; Almasan, A.; Gong, Z. Nudix Hydrolase NUDT16 Regulates 53BP1 Protein by Reversing 53BP1 ADP-Ribosylation. Cancer Res 2020, 80, 999–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Ferreira, J.C.; Gross, E.R.; Mochly-Rosen, D. Targeting aldehyde dehydrogenase 2: new therapeutic opportunities. Physiol Rev 2014, 94, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashek, D.G.; Bornfeldt, K.E.; Coleman, R.A.; Berger, J.; Bernlohr, D.A.; Black, P.; DiRusso, C.C.; Farber, S.A.; Guo, W.; Hashimoto, N.; et al. Revised nomenclature for the mammalian long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase gene family. J Lipid Res 2004, 45, 1958–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, Y.; Setoyama, D.; Ito, R.; Kamiya, H.; Yamagata, Y.; Sekiguchi, M. Human MTH3 (NUDT18) protein hydrolyzes oxidized forms of guanosine and deoxyguanosine diphosphates: comparison with MTH1 and MTH2. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 21541–21549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.J.; Ellis, G.H.; Gover, S.; Naylor, C.E.; Phillips, C. Crystallographic study of coenzyme, coenzyme analogue and substrate binding in 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase: implications for NADP specificity and the enzyme mechanism. Structure 1994, 2, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starheim, K.K.; Gevaert, K.; Arnesen, T. Protein N-terminal acetyltransferases: when the start matters. Trends Biochem Sci 2012, 37, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qi, X.; Liu, B.; Huang, H. The STAT5-GATA2 pathway is critical in basophil and mast cell differentiation and maintenance. J Immunol 2015, 194, 4328–4338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, J.; Wermeling, F.; Nilsson, G.; Dahlin, J.S. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene disruption determines the roles of MITF and CITED2 in human mast cell differentiation. Blood Adv 2024, 8, 3941–3945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohneda, K.; Ohmori, S.; Yamamoto, M. Mouse Tryptase Gene Expression is Coordinately Regulated by GATA1 and GATA2 in Bone Marrow-Derived Mast Cells. International journal of molecular sciences 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, L.; Tsukamoto, S.; Suzuki, M.; Yamamoto-Mukai, H.; Yamamoto, M.; Philipsen, S.; Ohneda, K. Ablation of Gata1 in adult mice results in aplastic crisis, revealing its essential role in steady-state and stress erythropoiesis. Blood 2008, 111, 4375–4385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hershey, C.L.; Fisher, D.E. Mitf and Tfe3: members of a b-HLH-ZIP transcription factor family essential for osteoclast development and function. Bone 2004, 34, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kageyama, R.; Ohtsuka, T.; Kobayashi, T. The Hes gene family: repressors and oscillators that orchestrate embryogenesis. Development 2007, 134, 1243–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leimeister, C.; Externbrink, A.; Klamt, B.; Gessler, M. Hey genes: a novel subfamily of hairy- and Enhancer of split related genes specifically expressed during mouse embryogenesis. Mech Dev 1999, 85, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujino, T.; Yamazaki, Y.; Largaespada, D.A.; Jenkins, N.A.; Copeland, N.G.; Hirokawa, K.; Nakamura, T. Inhibition of myeloid differentiation by Hoxa9, Hoxb8, and Meis homeobox genes. Exp Hematol 2001, 29, 856–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanaoka, M.; Droma, Y.; Basnyat, B.; Ito, M.; Kobayashi, N.; Katsuyama, Y.; Kubo, K.; Ota, M. Genetic variants in EPAS1 contribute to adaptation to high-altitude hypoxia in Sherpas. PLoS One 2012, 7, e50566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Pilch, P.F. PTRF/Cavin-1 promotes efficient ribosomal RNA transcription in response to metabolic challenges. Elife 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, L.; Castrillo, A.; Tontonoz, P. Regulation of macrophage inflammatory gene expression by the orphan nuclear receptor Nur77. Mol Endocrinol 2006, 20, 786–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyal, M.; Tung, J.W.; Karsunky, H.; Zeng, H.; Selleri, L.; Weissman, I.L.; Herzenberg, L.A.; Cleary, M.L. B-cell development fails in the absence of the Pbx1 proto-oncogene. Blood 2007, 109, 4191–4199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humke, E.W.; Dorn, K.V.; Milenkovic, L.; Scott, M.P.; Rohatgi, R. The output of Hedgehog signaling is controlled by the dynamic association between Suppressor of Fused and the Gli proteins. Genes Dev 2010, 24, 670–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matissek, S.J.; Elsawa, S.F. GLI3: a mediator of genetic diseases, development and cancer. Cell Commun Signal 2020, 18, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melko, M.; Douguet, D.; Bensaid, M.; Zongaro, S.; Verheggen, C.; Gecz, J.; Bardoni, B. Functional characterization of the AFF (AF4/FMR2) family of RNA-binding proteins: insights into the molecular pathology of FRAXE intellectual disability. Hum Mol Genet 2011, 20, 1873–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, T.J.; Cao, X.L.; Luan, S.; Cui, W.H.; Qiu, S.H.; Wang, Y.C.; Zhao, C.J.; Fu, P. Percentage and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in patients with hyperthyroidism. Mol Med Rep 2018, 17, 2137–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabo, S.J.; Kim, S.T.; Costa, G.L.; Zhang, X.; Fathman, C.G.; Glimcher, L.H. A novel transcription factor, T-bet, directs Th1 lineage commitment. Cell 2000, 100, 655–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, G.; Liu, X.; Ngo, K.; De Leon-Tabaldo, A.; Zhao, S.; Luna-Roman, R.; Yu, J.; Cao, T.; Kuhn, R.; Wilkinson, P.; et al. RORgammat and RORalpha signature genes in human Th17 cells. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0181868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberl, G.; Littman, D.R. The role of the nuclear hormone receptor RORgammat in the development of lymph nodes and Peyer's patches. Immunol Rev 2003, 195, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnowski, A.; Chevrier, S.; Belz, G.T.; Mount, A.; Emslie, D.; D'Costa, K.; Tarlinton, D.M.; Kallies, A.; Corcoran, L.M. B and T cells collaborate in antiviral responses via IL-6, IL-21, and transcriptional activator and coactivator, Oct2 and OBF-1. J Exp Med 2012, 209, 2049–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laidlaw, B.J.; Cyster, J.G. Transcriptional regulation of memory B cell differentiation. Nat Rev Immunol 2021, 21, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, J.; Nielsen, P.J.; Fischer, K.D.; Bujard, H.; Wirth, T. The B lymphocyte-specific coactivator BOB.1/OBF.1 is required at multiple stages of B-cell development. Mol Cell Biol 2001, 21, 1531–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Coz, C.; Nguyen, D.N.; Su, C.; Nolan, B.E.; Albrecht, A.V.; Xhani, S.; Sun, D.; Demaree, B.; Pillarisetti, P.; Khanna, C.; et al. Constrained chromatin accessibility in PU.1-mutated agammaglobulinemia patients. J Exp Med 2021, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schotte, R.; Rissoan, M.C.; Bendriss-Vermare, N.; Bridon, J.M.; Duhen, T.; Weijer, K.; Briere, F.; Spits, H. The transcription factor Spi-B is expressed in plasmacytoid DC precursors and inhibits T-, B-, and NK-cell development. Blood 2003, 101, 1015–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutt, S.L.; Heavey, B.; Rolink, A.G.; Busslinger, M. Commitment to the B-lymphoid lineage depends on the transcription factor Pax5. Nature 1999, 401, 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsukumo, S.I.; Subramani, P.G.; Seija, N.; Tabata, M.; Maekawa, Y.; Mori, Y.; Ishifune, C.; Itoh, Y.; Ota, M.; Fujio, K.; et al. AFF3, a susceptibility factor for autoimmune diseases, is a molecular facilitator of immunoglobulin class switch recombination. Sci Adv 2022, 8, eabq0008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iijima, T.; Iijima, Y.; Witte, H.; Scheiffele, P. Neuronal cell type-specific alternative splicing is regulated by the KH domain protein SLM1. The Journal of cell biology 2014, 204, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treiber, T.; Mandel, E.M.; Pott, S.; Gyory, I.; Firner, S.; Liu, E.T.; Grosschedl, R. Early B cell factor 1 regulates B cell gene networks by activation, repression, and transcription- independent poising of chromatin. Immunity 2010, 32, 714–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaubatz, S.; Lindeman, G.J.; Ishida, S.; Jakoi, L.; Nevins, J.R.; Livingston, D.M.; Rempel, R.E. E2F4 and E2F5 play an essential role in pocket protein-mediated G1 control. Mol Cell 2000, 6, 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Liu, F. Bach2: A Key Regulator in Th2-Related Immune Cells and Th2 Immune Response. J Immunol Res 2022, 2022, 2814510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piazza, R.; Magistroni, V.; Redaelli, S.; Mauri, M.; Massimino, L.; Sessa, A.; Peronaci, M.; Lalowski, M.; Soliymani, R.; Mezzatesta, C.; et al. SETBP1 induces transcription of a network of development genes by acting as an epigenetic hub. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, T.; Krishnamoorthy, V.; Yu, S.; Xue, H.H.; Kee, B.L.; Verykokakis, M. The transcription factor lymphoid enhancer factor 1 controls invariant natural killer T cell expansion and Th2-type effector differentiation. J Exp Med 2015, 212, 793–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, M.E.; Jarjour, N.N.; Lin, C.C.; Edelson, B.T. Transcription Factor Bhlhe40 in Immunity and Autoimmunity. Trends Immunol 2020, 41, 1023–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallaq, H.; Pinter, E.; Enciso, J.; McGrath, J.; Zeiss, C.; Brueckner, M.; Madri, J.; Jacobs, H.C.; Wilson, C.M.; Vasavada, H.; et al. A null mutation of Hhex results in abnormal cardiac development, defective vasculogenesis and elevated Vegfa levels. Development 2004, 131, 5197–5209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrink, M.; Aveskogh, M.; Hellman, L. Isolation of cDNA clones for 42 different Kruppel-related zinc finger proteins expressed in the human monoblast cell line U-937. DNA Cell Biol 1995, 14, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mark, C.; Abrink, M.; Hellman, L. Comparative analysis of KRAB zinc finger proteins in rodents and man: evidence for several evolutionarily distinct subfamilies of KRAB zinc finger genes. DNA Cell Biol 1999, 18, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looman, C.; Abrink, M.; Mark, C.; Hellman, L. KRAB zinc finger proteins: an analysis of the molecular mechanisms governing their increase in numbers and complexity during evolution. Molecular biology and evolution 2002, 19, 2118–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgopoulos, K.; Winandy, S.; Avitahl, N. The role of the Ikaros gene in lymphocyte development and homeostasis. Annual review of immunology 1997, 15, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papathanasiou, P.; Perkins, A.C.; Cobb, B.S.; Ferrini, R.; Sridharan, R.; Hoyne, G.F.; Nelms, K.A.; Smale, S.T.; Goodnow, C.C. Widespread failure of hematolymphoid differentiation caused by a recessive niche-filling allele of the Ikaros transcription factor. Immunity 2003, 19, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, H.; Wang, L.; Cantor, H.; Kim, H.J. New Insights Into the Biology of CD8 Regulatory T Cells. Adv Immunol 2018, 140, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, B.; Sun, L.; Avitahl, N.; Andrikopoulos, K.; Ikeda, T.; Gonzales, E.; Wu, P.; Neben, S.; Georgopoulos, K. Aiolos, a lymphoid restricted transcription factor that interacts with Ikaros to regulate lymphocyte differentiation. The EMBO journal 1997, 16, 2004–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Person, R.E.; Li, F.Q.; Duan, Z.; Benson, K.F.; Wechsler, J.; Papadaki, H.A.; Eliopoulos, G.; Kaufman, C.; Bertolone, S.J.; Nakamoto, B.; et al. Mutations in proto-oncogene GFI1 cause human neutropenia and target ELA2. Nat Genet 2003, 34, 308–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.M.; Moolten, D.; Burlein, J.; Romano, J.; Bhaerman, R.; Godillot, A.; Mellon, M.; Rauscher, F.J., 3rd; Kant, J.A. Identification of a zinc finger protein that inhibits IL-2 gene expression. Science 1991, 254, 1791–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassez, G.; Camand, O.J.; Cacheux, V.; Kobetz, A.; Dastot-Le Moal, F.; Marchant, D.; Catala, M.; Abitbol, M.; Goossens, M. Pleiotropic and diverse expression of ZFHX1B gene transcripts during mouse and human development supports the various clinical manifestations of the "Mowat-Wilson" syndrome. Neurobiol Dis 2004, 15, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Briseno, C.G.; Grajales-Reyes, G.E.; Haldar, M.; Iwata, A.; Kretzer, N.M.; Kc, W.; Tussiwand, R.; Higashi, Y.; Murphy, T.L.; et al. Transcription factor Zeb2 regulates commitment to plasmacytoid dendritic cell and monocyte fate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113, 14775–14780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Johns, D.C.; Geiman, D.E.; Marban, E.; Dang, D.T.; Hamlin, G.; Sun, R.; Yang, V.W. Kruppel-like factor 4 (gut-enriched Kruppel-like factor) inhibits cell proliferation by blocking G1/S progression of the cell cycle. J Biol Chem 2001, 276, 30423–30428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Raj, L.; Zhao, B.; Kimura, Y.; Bernstein, A.; Aaronson, S.A.; Lee, S.W. Hzf Determines cell survival upon genotoxic stress by modulating p53 transactivation. Cell 2007, 130, 624–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, K.; Kim, K.W.; Miyajima, A. A novel nuclear zinc finger protein EZI enhances nuclear retention and transactivation of STAT3. The EMBO journal 2002, 21, 6174–6184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Nakaya, N.; Chavali, V.R.; Ma, Z.; Jiao, X.; Sieving, P.A.; Riazuddin, S.; Tomarev, S.I.; Ayyagari, R.; Riazuddin, S.A.; et al. A mutation in ZNF513, a putative regulator of photoreceptor development, causes autosomal-recessive retinitis pigmentosa. American journal of human genetics 2010, 87, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubara, E.; Sakai, I.; Yamanouchi, J.; Fujiwara, H.; Yakushijin, Y.; Hato, T.; Shigemoto, K.; Yasukawa, M. The role of zinc finger protein 521/early hematopoietic zinc finger protein in erythroid cell differentiation. J Biol Chem 2009, 284, 3480–3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, M.; Choe, S.K.; Runko, A.P.; Gardner, P.D.; Sagerstrom, C.G. Nlz1/Znf703 acts as a repressor of transcription. BMC Dev Biol 2008, 8, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhu, B.; Zhou, X.; Ning, H.; Zhang, F.; Yan, B.; Chen, J.; Ma, T. ZNF787 and HDAC1 Mediate Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability in an In Vitro Model of Alzheimer's Disease Microenvironment. Neurotox Res 2024, 42, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.F.; Nelson, C.B.; Wells, J.K.; Fernando, M.; Lu, R.; Allen, J.A.M.; Malloy, L.; Lamm, N.; Murphy, V.J.; Mackay, J.P.; et al. ZNF827 is a single-stranded DNA binding protein that regulates the ATR-CHK1 DNA damage response pathway. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, H.; Chen, D.; Yuan, W.; Li, J.; Zeng, Y.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, G.; et al. Zinc finger protein 831 promotes apoptosis and enhances chemosensitivity in breast cancer by acting as a novel transcriptional repressor targeting the STAT3/Bcl2 signaling pathway. Genes Dis 2024, 11, 430–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhondalay, G.K.R.; Bunning, B.; Bauer, R.N.; Barnathan, E.S.; Maniscalco, C.; Baribaud, F.; Nadeau, K.C.; Andorf, S. Transcriptomic and methylomic features in asthmatic and nonasthmatic twins. Allergy 2020, 75, 989–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carapito, R.; Ivanova, E.L.; Morlon, A.; Meng, L.; Molitor, A.; Erdmann, E.; Kieffer, B.; Pichot, A.; Naegely, L.; Kolmer, A.; et al. ZMIZ1 Variants Cause a Syndromic Neurodevelopmental Disorder. American journal of human genetics 2019, 104, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voo, K.S.; Carlone, D.L.; Jacobsen, B.M.; Flodin, A.; Skalnik, D.G. Cloning of a mammalian transcriptional activator that binds unmethylated CpG motifs and shares a CXXC domain with DNA methyltransferase, human trithorax, and methyl-CpG binding domain protein 1. Mol Cell Biol 2000, 20, 2108–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krausgruber, T.; Blazek, K.; Smallie, T.; Alzabin, S.; Lockstone, H.; Sahgal, N.; Hussell, T.; Feldmann, M.; Udalova, I.A. IRF5 promotes inflammatory macrophage polarization and TH1-TH17 responses. Nat Immunol 2011, 12, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohlsson, E.; Schuster, M.B.; Hasemann, M.; Porse, B.T. The multifaceted functions of C/EBPalpha in normal and malignant haematopoiesis. Leukemia 2016, 30, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavit, J.A.; Motohashi, H.; Onodera, K.; Akasaka, J.; Yamamoto, M.; Engel, J.D. Impaired megakaryopoiesis and behavioral defects in mafG-null mutant mice. Genes Dev 1998, 12, 2164–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbalakshmi, A.R.; Sahoo, S.; Manjunatha, P.; Goyal, S.; Kasiviswanathan, V.A.; Mahesh, Y.; Ramu, S.; McMullen, I.; Somarelli, J.A.; Jolly, M.K. The ELF3 transcription factor is associated with an epithelial phenotype and represses epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Biol Eng 2023, 17, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Gao, H.; Bleday, R.; Zhu, Z. Homeobox transcription factor VentX regulates differentiation and maturation of human dendritic cells. J Biol Chem 2014, 289, 14633–14643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysokinski, D.; Pawlowska, E.; Blasiak, J. RUNX2: A Master Bone Growth Regulator That May Be Involved in the DNA Damage Response. DNA Cell Biol 2015, 34, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, M.; Misaka, R.; Nitta, K.; Tsuchiya, K. Transcriptional factors, Mafs and their biological roles. World J Diabetes 2015, 6, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, Z.; Hu, G.; Wei, G.; Cui, K.; Yamane, A.; Resch, W.; Wang, R.; Green, D.R.; Tessarollo, L.; Casellas, R.; et al. c-Myc is a universal amplifier of expressed genes in lymphocytes and embryonic stem cells. Cell 2012, 151, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pires-daSilva, A.; Nayernia, K.; Engel, W.; Torres, M.; Stoykova, A.; Chowdhury, K.; Gruss, P. Mice deficient for spermatid perinuclear RNA-binding protein show neurologic, spermatogenic, and sperm morphological abnormalities. Dev Biol 2001, 233, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, M.; Lin, P.S.; Dahmus, M.E.; Gill, G.N. A novel RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain phosphatase that preferentially dephosphorylates serine 5. J Biol Chem 2003, 278, 26078–26085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, L.A.; Mabin, J.W.; Gangras, P.; Singh, G. The exon junction complex: a lifelong guardian of mRNA fate. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Hochedlinger, K. The sox family of transcription factors: versatile regulators of stem and progenitor cell fate. Cell Stem Cell 2013, 12, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, K.; Akira, S. STAT family of transcription factors in cytokine-mediated biological responses. Cytokine & growth factor reviews 2000, 11, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, N.; Liongue, C.; Ward, A.C. STAT proteins: a kaleidoscope of canonical and non-canonical functions in immunity and cancer. J Hematol Oncol 2021, 14, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikomori, R.; Usui, T.; Wu, C.Y.; Morinobu, A.; O'Shea, J.J.; Strober, W. Activated STAT4 has an essential role in Th1 differentiation and proliferation that is independent of its role in the maintenance of IL-12R beta 2 chain expression and signaling. J Immunol 2002, 169, 4388–4398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, V.; Fu, Y.X. Lymphotoxin signalling in immune homeostasis and the control of microorganisms. Nat Rev Immunol 2013, 13, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicola, N.A.; Babon, J.J. Leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF). Cytokine & growth factor reviews 2015, 26, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadey, R.E.; Grebinoski, S.; Zhang, Q.; Brunazzi, E.A.; Burton, A.; Workman, C.J.; Vignali, D.A.A. Regulatory T Cell-Derived TRAIL Is Not Required for Peripheral Tolerance. Immunohorizons 2021, 5, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aass, K.R.; Kastnes, M.H.; Standal, T. Molecular interactions and functions of IL-32. J Leukoc Biol 2021, 109, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmane, S.L.; Kremlev, S.; Amini, S.; Sawaya, B.E. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1): an overview. t: Journal of interferon & cytokine research, 2009; 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinrichs, A.C.; Blokland, S.L.M.; Kruize, A.A.; Lafeber, F.P.J.; Leavis, H.L.; van Roon, J.A.G. CCL5 Release by CCR9+ CD8 T Cells: A Potential Contributor to Immunopathology of Primary Sjogren's Syndrome. Frontiers in immunology 2022, 13, 887972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmers, T.A.; Jin, X.; Hsiao, E.C.; McGrath, S.A.; Esquela, A.F.; Koniaris, L.G. Growth differentiation factor-15/macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1 induction after kidney and lung injury. Shock 2005, 23, 543–548. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Hu, G.; Betts, C.; Harmon, E.Y.; Keller, R.S.; Van De Water, L.; Zhou, J. Transforming growth factor-beta1-induced transcript 1 protein, a novel marker for smooth muscle contractile phenotype, is regulated by serum response factor/myocardin protein. J Biol Chem 2011, 286, 41589–41599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadmiel, M.; Fritz-Six, K.; Pacharne, S.; Richards, G.O.; Li, M.; Skerry, T.M.; Caron, K.M. Research resource: Haploinsufficiency of receptor activity-modifying protein-2 (RAMP2) causes reduced fertility, hyperprolactinemia, skeletal abnormalities, and endocrine dysfunction in mice. Mol Endocrinol 2011, 25, 1244–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, A.L.; Karlsson, R.; Roberts, A.R.E.; Ridley, A.J.L.; Pun, N.; Khan, B.; Lawless, C.; Luis, R.; Szpakowska, M.; Chevigne, A.; et al. Chemokine CXCL4 interactions with extracellular matrix proteoglycans mediate widespread immune cell recruitment independent of chemokine receptors. Cell Rep 2023, 42, 111930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.H.; Stacey, M.; Hamann, J.; Gordon, S.; McKnight, A.J. Human EMR2, a novel EGF-TM7 molecule on chromosome 19p13.1, is closely related to CD97. Genomics 2000, 67, 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yona, S.; Lin, H.H.; Dri, P.; Davies, J.Q.; Hayhoe, R.P.; Lewis, S.M.; Heinsbroek, S.E.; Brown, K.A.; Perretti, M.; Hamann, J.; et al. Ligation of the adhesion-GPCR EMR2 regulates human neutrophil function. FASEB J 2008, 22, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Shi, Y.; Wen, Y.; Li, W.; Feng, J.; Chen, C. The roles of TNFAIP2 in cancers and infectious diseases. J Cell Mol Med 2018, 22, 5188–5195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.G.; Boone, D.L.; Chai, S.; Libby, S.L.; Chien, M.; Lodolce, J.P.; Ma, A. Failure to regulate TNF-induced NF-kappaB and cell death responses in A20-deficient mice. Science 2000, 289, 2350–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corona, A.; Blobe, G.C. The role of the extracellular matrix protein TGFBI in cancer. Cell Signal 2021, 84, 110028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickford, D.; Frankenberg, S.; Shaw, G.; Renfree, M.B. Evolution of vertebrate interferon inducible transmembrane proteins. BMC genomics 2012, 13, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, A.I.; Wiltshire, T.; Batalov, S.; Lapp, H.; Ching, K.A.; Block, D.; Zhang, J.; Soden, R.; Hayakawa, M.; Kreiman, G.; et al. A gene atlas of the mouse and human protein-encoding transcriptomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004, 101, 6062–6067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, E.R.; Berg, K.L.; Einstein, D.B.; Lee, P.S.; Pixley, F.J.; Wang, Y.; Yeung, Y.G. Biology and action of colony--stimulating factor-1. Mol Reprod Dev 1997, 46, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Boone, T.; Delaney, J.; Hawkins, N.; Kelley, M.; Ramakrishnan, M.; McCabe, S.; Qiu, W.R.; Kornuc, M.; Xia, X.Z.; et al. APRIL and TALL-I and receptors BCMA and TACI: system for regulating humoral immunity. Nat Immunol 2000, 1, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascalho, M.; Platt, J.L. TNFRSF13B Diversification Fueled by B Cell Responses to Environmental Challenges-A Hypothesis. Frontiers in immunology 2021, 12, 634544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seshasayee, D.; Valdez, P.; Yan, M.; Dixit, V.M.; Tumas, D.; Grewal, I.S. Loss of TACI causes fatal lymphoproliferation and autoimmunity, establishing TACI as an inhibitory BLyS receptor. Immunity 2003, 18, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, M.; Tussiwand, R.; Bosco, N.; Rolink, A.G. Crucial role for BAFF-BAFF-R signaling in the survival and maintenance of mature B cells. PLoS One 2009, 4, e5456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thum, E.; Shao, Z.; Schwarz, H. CD137, implications in immunity and potential for therapy. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2009, 14, 4173–4188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wensman, H.; Kamgari, N.; Johansson, A.; Grujic, M.; Calounova, G.; Lundequist, A.; Ronnberg, E.; Pejler, G. Tumor-mast cell interactions: induction of pro-tumorigenic genes and anti-tumorigenic 4-1BB in MCs in response to Lewis Lung Carcinoma. Mol Immunol 2012, 50, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, G.; Bauer, J.H.; Haridas, V.; Wang, S.; Liu, D.; Yu, G.; Vincenz, C.; Aggarwal, B.B.; Ni, J.; Dixit, V.M. Identification and functional characterization of DR6, a novel death domain-containing TNF receptor. FEBS letters 1998, 431, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.H.; Hsieh, S.L.; Chen, M.C.; Lin, W.W. Lymphotoxin beta receptor induces interleukin 8 gene expression via NF-kappaB and AP-1 activation. Exp Cell Res 2002, 278, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.R.; Kottmann, A.H.; Kuroda, M.; Taniuchi, I.; Littman, D.R. Function of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 in haematopoiesis and in cerebellar development. Nature 1998, 393, 595–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyasaka, M.; Tanaka, T. Lymphocyte trafficking across high endothelial venules: dogmas and enigmas. Nat Rev Immunol 2004, 4, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, R.; Mattis, A.E.; Kremmer, E.; Wolf, E.; Brem, G.; Lipp, M. A putative chemokine receptor, BLR1, directs B cell migration to defined lymphoid organs and specific anatomic compartments of the spleen. Cell 1996, 87, 1037–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardtke, S.; Ohl, L.; Forster, R. Balanced expression of CXCR5 and CCR7 on follicular T helper cells determines their transient positioning to lymph node follicles and is essential for efficient B-cell help. Blood 2005, 106, 1924–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutyser, E.; Struyf, S.; Van Damme, J. The CC chemokine CCL20 and its receptor CCR6. Cytokine & growth factor reviews 2003, 14, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, T.; Yang, X.O.; Chung, Y.; Fukunaga, A.; Nurieva, R.; Pappu, B.; Martin-Orozco, N.; Kang, H.S.; Ma, L.; Panopoulos, A.D.; et al. CCR6 regulates the migration of inflammatory and regulatory T cells. J Immunol 2008, 181, 8391–8401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrumaihi, F. The Multi-Functional Roles of CCR7 in Human Immunology and as a Promising Therapeutic Target for Cancer Therapeutics. Front Mol Biosci 2022, 9, 834149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, N.; Benechet, A.P.; Lefrancois, L.; Khanna, K.M. CD8 T Cells Enter the Splenic T Cell Zones Independently of CCR7, but the Subsequent Expansion and Trafficking Patterns of Effector T Cells after Infection Are Dysregulated in the Absence of CCR7 Migratory Cues. J Immunol 2015, 195, 5227–5236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babina, M.; Wang, Z.; Franke, K.; Zuberbier, T. Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin Promotes MRGPRX2-Triggered Degranulation of Skin Mast Cells in a STAT5-Dependent Manner with Further Support from JNK. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.C.; Cheng, F.Y.; Liu, J.J.; Ye, Y.L. Expression and Regulation of Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin and Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin Receptor Heterocomplex in the Innate-Adaptive Immunity of Pediatric Asthma. International journal of molecular sciences 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juchem, K.W.; Gounder, A.P.; Gao, J.P.; Seccareccia, E.; Yeddula, N.; Huffmaster, N.J.; Cote-Martin, A.; Fogal, S.E.; Souza, D.; Wang, S.S.; et al. NFAM1 Promotes Pro-Inflammatory Cytokine Production in Mouse and Human Monocytes. Frontiers in immunology 2021, 12, 773445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Walsh, M.C.; Takegahara, N.; Middleton, S.A.; Shin, H.I.; Kim, J.; Choi, Y. The purinergic receptor P2X5 regulates inflammasome activity and hyper-multinucleation of murine osteoclasts. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.H.; Walsh, M.C.; Yu, J.; Shen, H.; Wherry, E.J.; Choi, Y. Mice Lacking the Purinergic Receptor P2X5 Exhibit Defective Inflammasome Activation and Early Susceptibility to Listeria monocytogenes. J Immunol 2020, 205, 760–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, T.; Kamon, J.; Ito, Y.; Tsuchida, A.; Yokomizo, T.; Kita, S.; Sugiyama, T.; Miyagishi, M.; Hara, K.; Tsunoda, M.; et al. Cloning of adiponectin receptors that mediate antidiabetic metabolic effects. Nature 2003, 423, 762–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Sladek, R.; Carrier, J.; Bader, J.A.; Richard, D.; Giguere, V. Reduced fat mass in mice lacking orphan nuclear receptor estrogen-related receptor alpha. Mol Cell Biol 2003, 23, 7947–7956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. Molecular mechanisms of beta(2)-adrenergic receptor function, response, and regulation. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006, 117, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebordosa, C.; Kogevinas, M.; Guerra, S.; Castro-Giner, F.; Jarvis, D.; Cazzoletti, L.; Pin, I.; Siroux, V.; Wjst, M.; Anto, J.M.; et al. ADRB2 Gly16Arg polymorphism, asthma control and lung function decline. Eur Respir J 2011, 38, 1029–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galiegue, S.; Mary, S.; Marchand, J.; Dussossoy, D.; Carriere, D.; Carayon, P.; Bouaboula, M.; Shire, D.; Le Fur, G.; Casellas, P. Expression of central and peripheral cannabinoid receptors in human immune tissues and leukocyte subpopulations. European journal of biochemistry / FEBS 1995, 232, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, P.; Chandra, V.; Rastinejad, F. Retinoic acid actions through mammalian nuclear receptors. Chem Rev 2014, 114, 233–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harman, J.L.; Sayers, J.; Chapman, C.; Pellet-Many, C. Emerging Roles for Neuropilin-2 in Cardiovascular Disease. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, G.; Geuze, H.J.; Strous, G.J.; Schwartz, A.L. 39 kDa receptor-associated protein is an ER resident protein and molecular chaperone for LDL receptor-related protein. The EMBO journal 1995, 14, 2269–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, N.; Dalli, J.; Colas, R.A.; Serhan, C.N. Identification of resolvin D2 receptor mediating resolution of infections and organ protection. J Exp Med 2015, 212, 1203–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Inoue, A.; Ikuta, T.; Xia, R.; Wang, N.; Kawakami, K.; Xu, Z.; Qian, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, A.; et al. Structural basis of lysophosphatidylserine receptor GPR174 ligand recognition and activation. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.; Zhao, X. GPR174 suppression attenuates retinopathy in angiotensin II (Ang II)-treated mice by reducing inflammation via PI3K/AKT signaling. Biomed Pharmacother 2020, 122, 109701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Lin, H.H. The role of GPR56/ADGRG1 in health and disease. Biomed J 2021, 44, 534–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredriksson, R.; Hoglund, P.J.; Gloriam, D.E.; Lagerstrom, M.C.; Schioth, H.B. Seven evolutionarily conserved human rhodopsin G protein-coupled receptors lacking close relatives. FEBS letters 2003, 554, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, L.L.; Matzuk, M.M.; Dodds, D.C.; Perin, M.S. Biochemical interactions of the neuronal pentraxins. Neuronal pentraxin (NP) receptor binds to taipoxin and taipoxin-associated calcium-binding protein 49 via NP1 and NP2. J Biol Chem 2000, 275, 17786–17792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gembardt, F.; Grajewski, S.; Vahl, M.; Schultheiss, H.P.; Walther, T. Angiotensin metabolites can stimulate receptors of the Mas-related genes family. Mol Cell Biochem 2008, 319, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santschi, E.M.; Purdy, A.K.; Valberg, S.J.; Vrotsos, P.D.; Kaese, H.; Mickelson, J.R. Endothelin receptor B polymorphism associated with lethal white foal syndrome in horses. Mamm Genome 1998, 9, 306–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Zhou, L.; Sun, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, T.; Fu, F. Dopamine, a co-regulatory component, bridges the central nervous system and the immune system. Biomed Pharmacother 2022, 145, 112458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampino, A.; Marakhovskaia, A.; Soares-Silva, T.; Torretta, S.; Veneziani, F.; Beaulieu, J.M. Antipsychotic Drug Responsiveness and Dopamine Receptor Signaling; Old Players and New Prospects. Front Psychiatry 2018, 9, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, R.D.; Ontiveros, A.E.; Moses, M.M.; Behringer, R.R. AMH and AMHR2 mutations: A spectrum of reproductive phenotypes across vertebrate species. Dev Biol 2019, 455, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miwatashi, S.; Arikawa, Y.; Matsumoto, T.; Uga, K.; Kanzaki, N.; Imai, Y.N.; Ohkawa, S. Synthesis and biological activities of 4-phenyl-5-pyridyl-1,3-thiazole derivatives as selective adenosine A3 antagonists. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 2008, 56, 1126–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevo, R.; Banerji, S.; Ni, J.; Jackson, D.G. Rapid plasma membrane-endosomal trafficking of the lymph node sinus and high endothelial venule scavenger receptor/homing receptor stabilin-1 (FEEL-1/CLEVER-1). J Biol Chem 2004, 279, 52580–52592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamata, Y.; Fujii, R.; Hosoya, M.; Harada, M.; Yoshida, H.; Miwa, M.; Fukusumi, S.; Habata, Y.; Itoh, T.; Shintani, Y.; et al. A G protein-coupled receptor responsive to bile acids. J Biol Chem 2003, 278, 9435–9440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Yamaki, F.; Koike, K.; Toro, L. New insights into the intracellular mechanisms by which PGI2 analogues elicit vascular relaxation: cyclic AMP-independent, Gs-protein mediated-activation of MaxiK channel. Curr Med Chem Cardiovasc Hematol Agents 2004, 2, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Actis Dato, V.; Chiabrando, G.A. The Role of Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor-Related Protein 1 in Lipid Metabolism, Glucose Homeostasis and Inflammation. International journal of molecular sciences 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etique, N.; Verzeaux, L.; Dedieu, S.; Emonard, H. LRP-1: a checkpoint for the extracellular matrix proteolysis. Biomed Res Int 2013, 2013, 152163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lillis, A.P.; Mikhailenko, I.; Strickland, D.K. Beyond endocytosis: LRP function in cell migration, proliferation and vascular permeability. J Thromb Haemost 2005, 3, 1884–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, M.L.; Ramprasad, M.P.; Umeda, P.K.; Tanaka, A.; Kobayashi, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Shimoyamada, H.; Kuo, W.L.; Li, R.; Song, R.; et al. A macrophage receptor for apolipoprotein B48: cloning, expression, and atherosclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000, 97, 7488–7493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D.D.; Kato, S.; Xie, W.; Mangelsdorf, D.J.; Schmidt, D.R.; Xiao, R.; Kliewer, S.A. International Union of Pharmacology. LXII. The NR1H and NR1I receptors: constitutive androstane receptor, pregnene X receptor, farnesoid X receptor alpha, farnesoid X receptor beta, liver X receptor alpha, liver X receptor beta, and vitamin D receptor. Pharmacol Rev 2006, 58, 742–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleet, J.C.; Schoch, R.D. Molecular mechanisms for regulation of intestinal calcium absorption by vitamin D and other factors. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 2010, 47, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Ortiz, Z.G.; Pendergraft, W.F., 3rd; Prasad, A.; Byrne, M.H.; Iram, T.; Blanchette, C.J.; Luster, A.D.; Hacohen, N.; El Khoury, J.; Means, T.K. The scavenger receptor SCARF1 mediates the clearance of apoptotic cells and prevents autoimmunity. Nat Immunol 2013, 14, 917–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachibana, I.; Bodorova, J.; Berditchevski, F.; Zutter, M.M.; Hemler, M.E. NAG-2, a novel transmembrane-4 superfamily (TM4SF) protein that complexes with integrins and other TM4SF proteins. J Biol Chem 1997, 272, 29181–29189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharan, R.; Huang, Y.; Cheppali, S.K.; Goren, S.; Shendrik, P.; Wang, W.; Qiao, J.; Kozlov, M.M.; Yu, L.; Sorkin, R. Tetraspanin 4 stabilizes membrane swellings and facilitates their maturation into migrasomes. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.P.; Cheng, X.; Mills, E.; Delling, M.; Wang, F.; Kurz, T.; Xu, H. The type IV mucolipidosis-associated protein TRPML1 is an endolysosomal iron release channel. Nature 2008, 455, 992–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Paola, S.; Scotto-Rosato, A.; Medina, D.L. TRPML1: The Ca((2+))retaker of the lysosome. Cell Calcium 2018, 69, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junqueira Alves, C.; Dariolli, R.; Haydak, J.; Kang, S.; Hannah, T.; Wiener, R.J.; DeFronzo, S.; Tejero, R.; Gusella, G.L.; Ramakrishnan, A.; et al. Plexin-B2 orchestrates collective stem cell dynamics via actomyosin contractility, cytoskeletal tension and adhesion. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 6019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Z.; Zhai, Y.; Liang, S.; Mori, Y.; Han, R.; Sutterwala, F.S.; Qiao, L. TRPM2 links oxidative stress to NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nat Commun 2013, 4, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, S.; Shimizu, S.; Kiyonaka, S.; Takahashi, N.; Wajima, T.; Hara, Y.; Negoro, T.; Hiroi, T.; Kiuchi, Y.; Okada, T.; et al. TRPM2-mediated Ca2+influx induces chemokine production in monocytes that aggravates inflammatory neutrophil infiltration. Nature medicine 2008, 14, 738–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, S.; Abreu, N.; Levitz, J.; Kruse, A.C. Structural basis for KCTD-mediated rapid desensitization of GABA(B) signalling. Nature 2019, 567, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeCoursey, T.E.; Chandy, K.G.; Gupta, S.; Cahalan, M.D. Voltage-gated K+ channels in human T lymphocytes: a role in mitogenesis? Nature 1984, 307, 465–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, A.; Lin, Z.; Humble, M.; Creech, C.D.; Wagoner, P.K.; Krafte, D.; Jegla, T.J.; Wickenden, A.D. Distribution and functional properties of human KCNH8 (Elk1) potassium channels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2003, 285, C1356–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokhtaeva, E.; Sachs, G.; Vagin, O. Assembly with the Na,K-ATPase alpha(1) subunit is required for export of beta(1) and beta(2) subunits from the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 11421–11431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Hoel, C.M.; Brohawn, S.G. Structures of tweety homolog proteins TTYH2 and TTYH3 reveal a Ca(2+)-dependent switch from intra- to intermembrane dimerization. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 6913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweadner, K.J.; Rael, E. The FXYD gene family of small ion transport regulators or channels: cDNA sequence, protein signature sequence, and expression. Genomics 2000, 68, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Hasegawa, Y.; Yamashita, H.; Shimizu, K.; Ding, Y.; Abe, M.; Ohta, H.; Imagawa, K.; Hojo, K.; Maki, H.; et al. Vasohibin as an endothelium-derived negative feedback regulator of angiogenesis. J Clin Invest 2004, 114, 898–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.Y.; Sorensen, L.K.; Brooke, B.S.; Urness, L.D.; Davis, E.C.; Taylor, D.G.; Boak, B.B.; Wendel, D.P. Defective angiogenesis in mice lacking endoglin. Science 1999, 284, 1534–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacherjee, A.; Daskhan, G.C.; Bains, A.; Watson, A.E.S.; Eskandari-Sedighi, G.; St Laurent, C.D.; Voronova, A.; Macauley, M.S. Increasing phagocytosis of microglia by targeting CD33 with liposomes displaying glycan ligands. J Control Release 2021, 338, 680–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erickson-Miller CL, Freeman SD, Hopson CB, D'Alessio KJ, Fischer EI, Kikly KK, et al. Characterization of Siglec-5 (CD170) expression and functional activity of anti-Siglec-5 antibodies on human phagocytes. Exp Hematol. 3: 2003;31(5), 2003.

- Suematsu, R.; Miyamoto, T.; Saijo, S.; Yamasaki, S.; Tada, Y.; Yoshida, H.; Miyake, Y. Identification of lipophilic ligands of Siglec5 and -14 that modulate innate immune responses. J Biol Chem 2019, 294, 16776–16788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.R.; Fong, J.J.; Carlin, A.F.; Busch, T.D.; Linden, R.; Angata, T.; Areschoug, T.; Parast, M.; Varki, N.; Murray, J.; et al. Siglec-5 and Siglec-14 are polymorphic paired receptors that modulate neutrophil and amnion signaling responses to group B Streptococcus. J Exp Med 2014, 211, 1231–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoi, H.; Myers, A.; Matsumoto, K.; Crocker, P.R.; Saito, H.; Bochner, B.S. Alteration and acquisition of Siglecs during in vitro maturation of CD34+ progenitors into human mast cells. Allergy 2006, 61, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkman-Van der Linden, E.C.; Varki, A. New aspects of siglec binding specificities, including the significance of fucosylation and of the sialyl-Tn epitope. Sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin superfamily lectins. J Biol Chem 2000, 275, 8625–8632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]