Submitted:

14 November 2024

Posted:

15 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Behavioural Tasks

2.2.1. Behaviour Rating Inventory of Executive Function—Adult Version (BRIEF-A)

2.2.2. The Sensitivity to Punishment and Sensitivity to Reward Questionnaire (SPSRQ)

2.2.3. Go/No-Go Task

2.2.4. Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART)

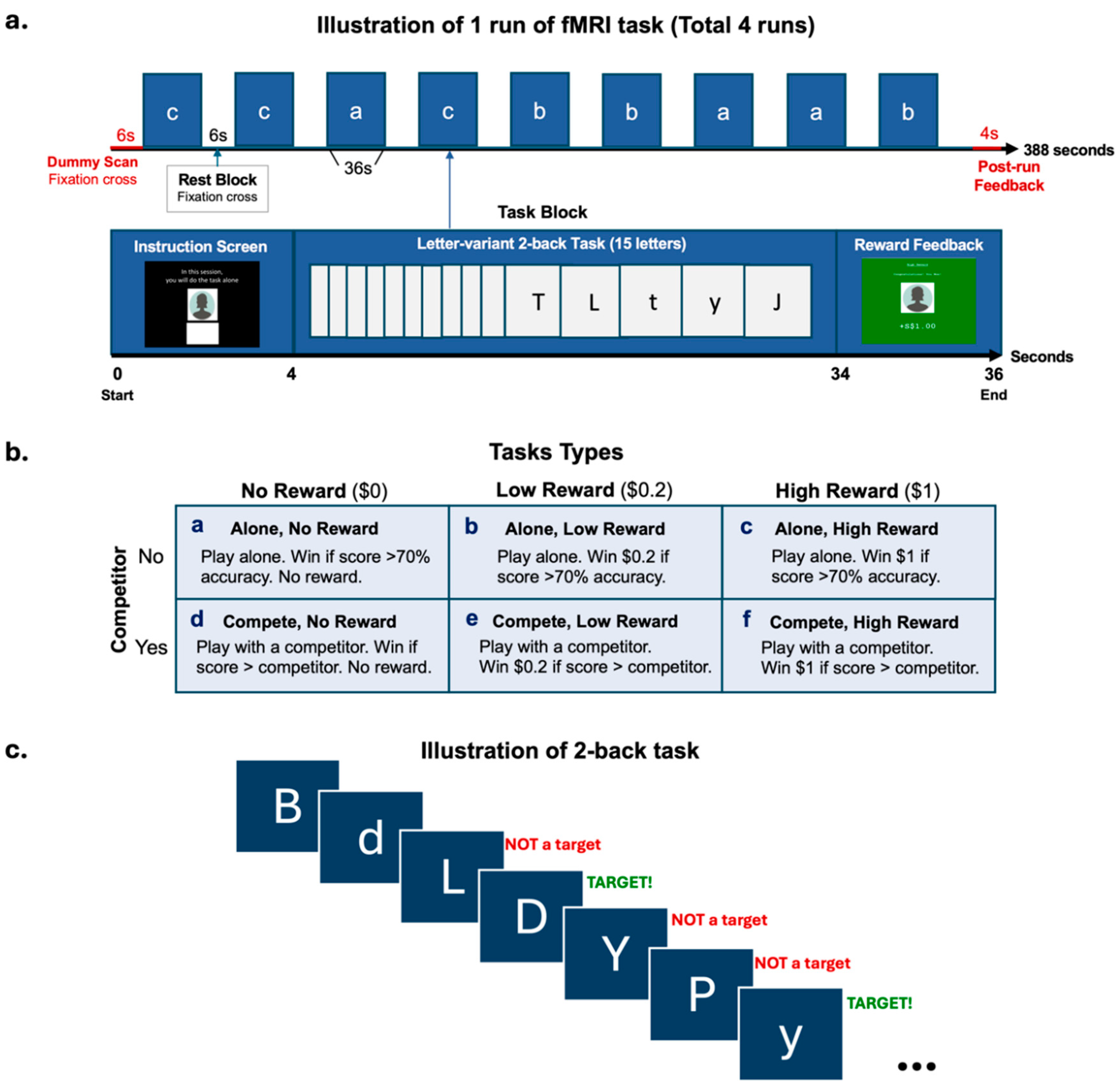

2.3. fMRI Task Design

2.4. Experimental Procedure

2.5. MRI Data Acquisition

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

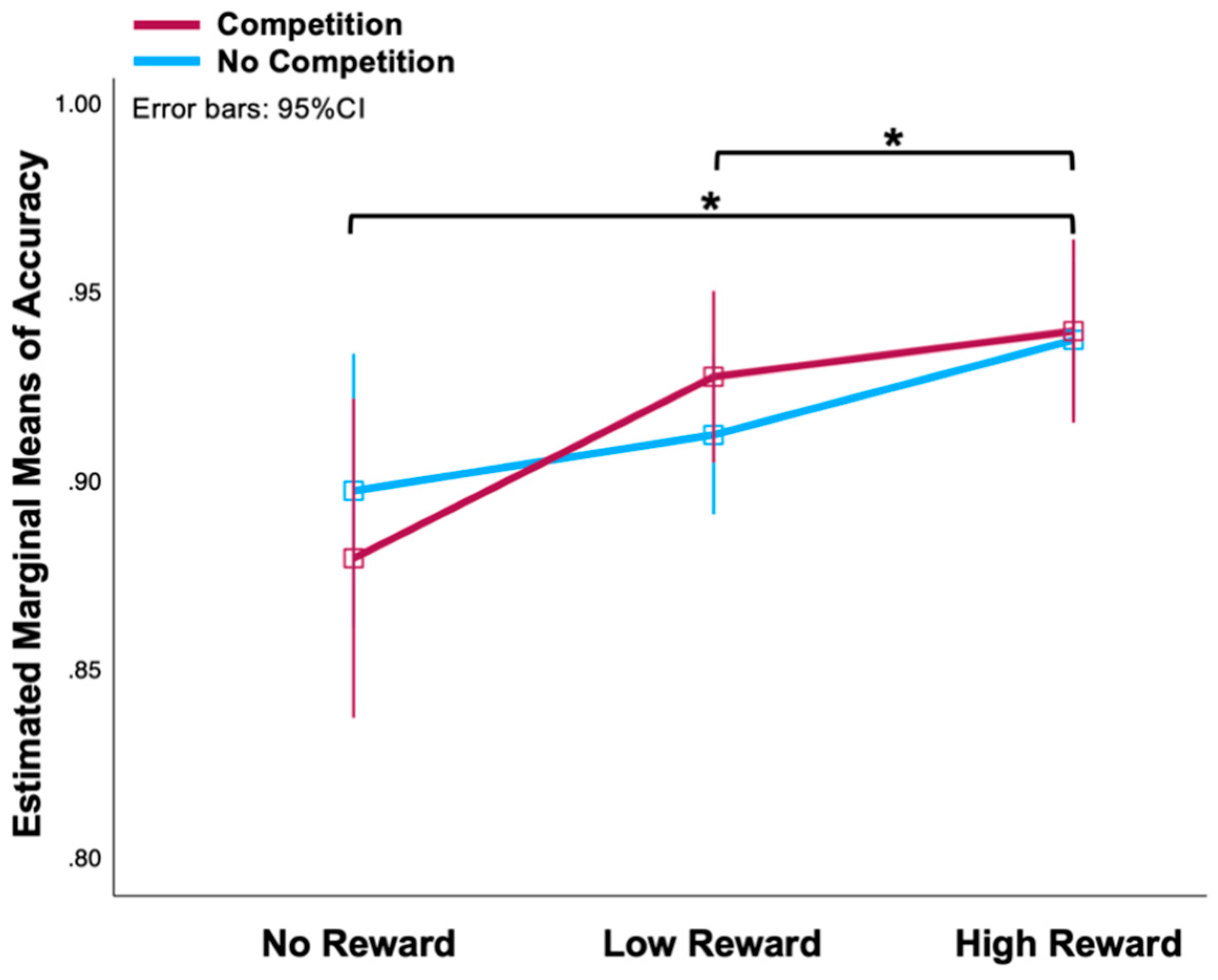

3.1. Behavioural Measures

3.2. fMRI Task

3.3. Debriefing

3.4. Neuroimaging Results

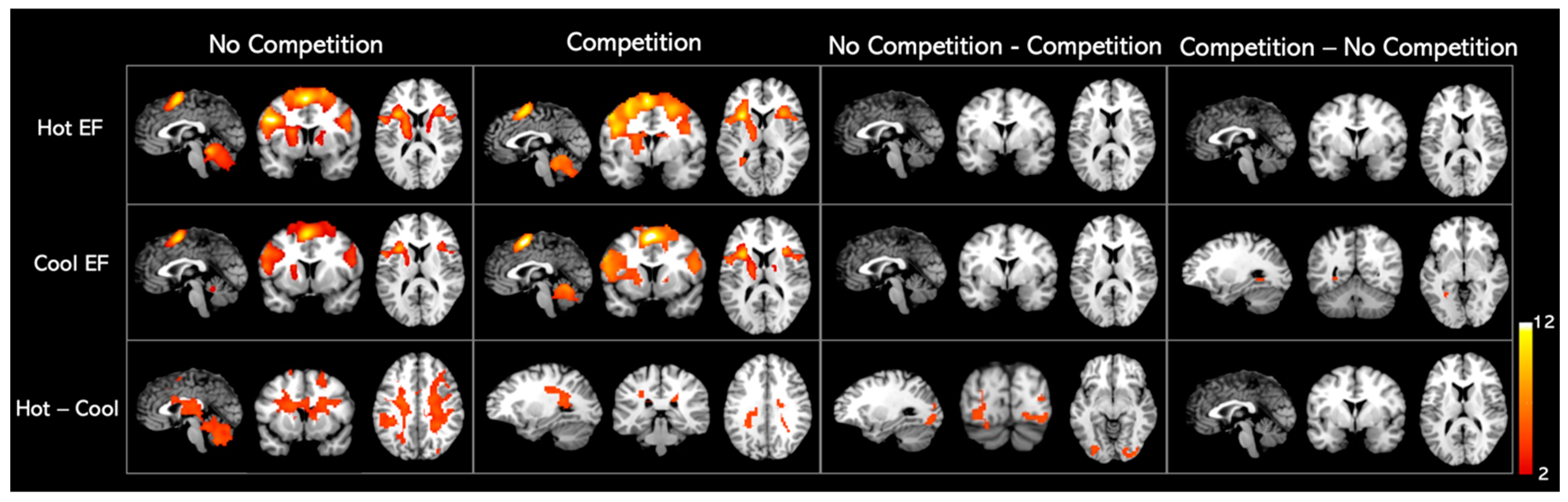

3.5. Correlation Analysis

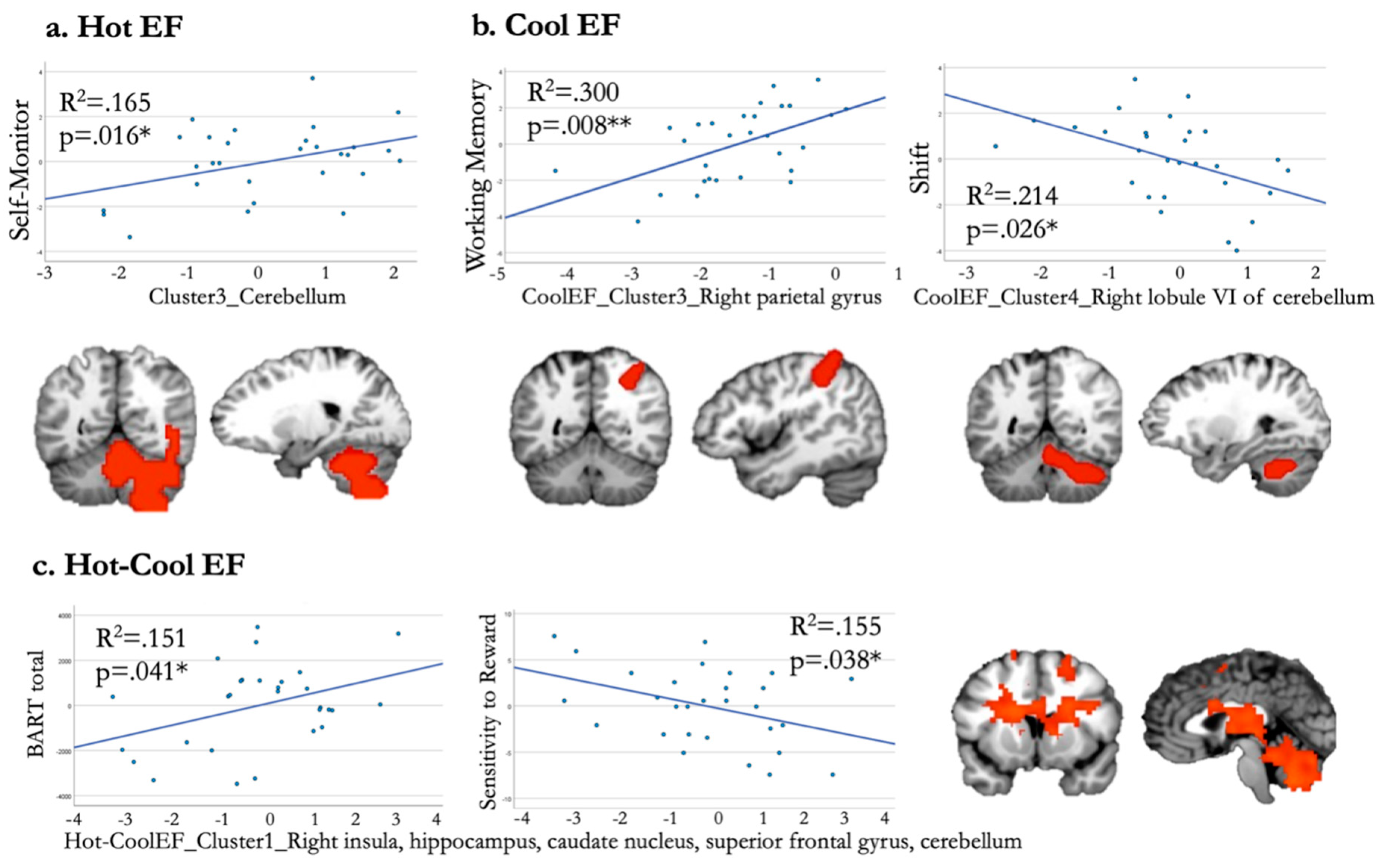

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

References

- Adrián-Ventura, J., Costumero, V., Parcet, M. A., & Ávila, C. (2019). Linking personality and brain anatomy: a structural MRI approach to Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci, 14(3), 329-338. [CrossRef]

- Aharon, I., Etcoff, N., Ariely, D., Chabris, C. F., O'Connor, E., & Breiter, H. C. (2001). Beautiful faces have variable reward value: fMRI and behavioral evidence. Neuron, 32(3), 537-551. [CrossRef]

- Ansari, D. (2012). Culture and education: new frontiers in brain plasticity. Trends Cogn Sci, 16(2), 93-95. [CrossRef]

- Ashburner, J. (2007). A fast diffeomorphic image registration algorithm. NeuroImage, 38(1), 95-113. [CrossRef]

- Baumann, O., & Mattingley, J. B. (2022). Cerebellum and Emotion Processing. Adv Exp Med Biol, 1378, 25-39. [CrossRef]

- Beck, S. M., Locke, H. S., Savine, A. C., Jimura, K., & Braver, T. S. (2010). Primary and secondary rewards differentially modulate neural activity dynamics during working memory. PLoS One, 5(2), e9251. [CrossRef]

- Berger, A., Sadeh, M., Tzur, G., Shuper, A., Kornreich, L., Inbar, D., Cohen, I. J., Michowiz, S., Yaniv, I., Constantini, S., Kessler, Y., & Merian, N. (2005). Task switching after cerebellar damage. Neuropsychology, 19(3), 362-370. [CrossRef]

- Berridge, K. C., & Kringelbach, M. L. (2015). Pleasure systems in the brain. Neuron, 86(3), 646-664. [CrossRef]

- Bigliassi, M., & Filho, E. (2022). Functional significance of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex during exhaustive exercise. Biol Psychol, 175, 108442. [CrossRef]

- Bobo, L., & Licari, F. C. (1989). EDUCATION AND POLITICAL TOLERANCE: TESTING THE EFFECTS OF COGNITIVE SOPHISTICATION AND TARGET GROUP AFFECT. Public Opinion Quarterly, 53(3), 285-308. [CrossRef]

- Brandl, F., Le Houcq Corbi, Z., Mulej Bratec, S., & Sorg, C. (2019). Cognitive reward control recruits medial and lateral frontal cortices, which are also involved in cognitive emotion regulation: A coordinate-based meta-analysis of fMRI studies. NeuroImage, 200, 659-673. [CrossRef]

- Brissenden, J. A., Adkins, T. J., Hsu, Y. T., & Lee, T. G. (2023). Reward influences the allocation but not the availability of resources in visual working memory. J Exp Psychol Gen, 152(7), 1825-1839. [CrossRef]

- Camerer, C., & Weber, M. (1992). Recent developments in modeling preferences: Uncertainty and ambiguity. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 5(4), 325-370. [CrossRef]

- Carver, C. S., Johnson, S. L., & Joormann, J. (2008). Serotonergic function, two-mode models of self-regulation, and vulnerability to depression: what depression has in common with impulsive aggression. Psychol Bull, 134(6), 912-943. [CrossRef]

- Catani, M., Dell’Acqua, F., & Thiebaut de Schotten, M. (2013). A revised limbic system model for memory, emotion and behaviour. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 37(8), 1724-1737. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Wu, S., & Li, F. (2022). Cognitive Neural Mechanism of Backward Inhibition and Deinhibition: A Review [Review]. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 16. [CrossRef]

- Ciapponi, C., Li, Y., Osorio Becerra, D. A., Rodarie, D., Casellato, C., Mapelli, L., & D'Angelo, E. (2023). Variations on the theme: focus on cerebellum and emotional processing. Front Syst Neurosci, 17, 1185752. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L., & Dehaene, S. (2004). Specialization within the ventral stream: the case for the visual word form area. NeuroImage, 22(1), 466-476. [CrossRef]

- Colonna, S., Eyre, O., Agha, S. S., Thapar, A., van Goozen, S., & Langley, K. (2022). Investigating the associations between irritability and hot and cool executive functioning in those with ADHD. BMC Psychiatry, 22(1), 166. [CrossRef]

- Craig, A. D. (2004). Human feelings: why are some more aware than others? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8(6), 239-241. [CrossRef]

- Cubillo, A., Makwana, A. B., & Hare, T. A. (2019). Differential modulation of cognitive control networks by monetary reward and punishment. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci, 14(3), 305-317. [CrossRef]

- Davidow, Juliet Y., Foerde, K., Galván, A., & Shohamy, D. (2016). An Upside to Reward Sensitivity: The Hippocampus Supports Enhanced Reinforcement Learning in Adolescence. Neuron, 92(1), 93-99. [CrossRef]

- Dawson, E. L., Shear, P. K., & Strakowski, S. M. (2012). Behavior regulation and mood predict social functioning among healthy young adults. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 34(3), 297-305. [CrossRef]

- Delgado, M. R., Stenger, V. A., & Fiez, J. A. (2004). Motivation-dependent Responses in the Human Caudate Nucleus. Cerebral Cortex, 14(9), 1022-1030. [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. (2013). Executive Functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64(1), 135-168. [CrossRef]

- Dichter, G. S., Felder, J. N., Green, S. R., Rittenberg, A. M., Sasson, N. J., & Bodfish, J. W. (2012). Reward circuitry function in autism spectrum disorders. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci, 7(2), 160-172. [CrossRef]

- DiMenichi, B. C., & Tricomi, E. (2017). Increases in brain activity during social competition predict decreases in working memory performance and later recall. Hum Brain Mapp, 38(1), 457-471. [CrossRef]

- du Boisgueheneuc, F., Levy, R., Volle, E., Seassau, M., Duffau, H., Kinkingnehun, S., Samson, Y., Zhang, S., & Dubois, B. (2006). Functions of the left superior frontal gyrus in humans: a lesion study. Brain, 129(Pt 12), 3315-3328. [CrossRef]

- Duverne, S., & Koechlin, E. (2017). Rewards and Cognitive Control in the Human Prefrontal Cortex. Cerebral Cortex, 27(10), 5024-5039. [CrossRef]

- Engelmann, J., Damaraju, E., Padmala, S., & Pessoa, L. (2009). Combined effects of attention and motivation on visual task performance: transient and sustained motivational effects [Original Research]. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 3. [CrossRef]

- Friederici, A. D., Fiebach, C. J., Schlesewsky, M., Bornkessel, I. D., & von Cramon, D. Y. (2006). Processing Linguistic Complexity and Grammaticality in the Left Frontal Cortex. Cerebral Cortex, 16(12), 1709-1717. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, N. P., & Robbins, T. W. (2022). The role of prefrontal cortex in cognitive control and executive function. Neuropsychopharmacology, 47(1), 72-89. [CrossRef]

- Gossen, A., Groppe, S. E., Winkler, L., Kohls, G., Herrington, J., Schultz, R. T., Gründer, G., & Spreckelmeyer, K. N. (2013). Neural evidence for an association between social proficiency and sensitivity to social reward. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 9(5), 661-670. [CrossRef]

- Greening, S. G., Finger, E. C., & Mitchell, D. G. (2011). Parsing decision making processes in prefrontal cortex: response inhibition, overcoming learned avoidance, and reversal learning. NeuroImage, 54(2), 1432-1441. [CrossRef]

- Grill-Spector, K., & Malach, R. (2004). The human visual cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci, 27, 649-677. [CrossRef]

- Hikosaka, O., & Isoda, M. (2010). Switching from automatic to controlled behavior: cortico-basal ganglia mechanisms. Trends Cogn Sci, 14(4), 154-161. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M., Bhatt, M., Adolphs, R., Tranel, D., & Camerer, C. F. (2005). Neural systems responding to degrees of uncertainty in human decision-making. Science, 310(5754), 1680-1683. [CrossRef]

- Insel, T. R., & Fernald, R. D. (2004). How the brain processes social information: searching for the social brain. Annu Rev Neurosci, 27, 697-722. [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, I., Liu, X., Clerkin, S., Schulz, K., Friston, K., Newcorn, J. H., & Fan, J. (2012). Effects of motivation on reward and attentional networks: an fMRI study. Brain and Behavior, 2(6), 741-753. [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263-291. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. H., Yoon, H., Kim, H., & Hamann, S. (2015). Individual differences in sensitivity to reward and punishment and neural activity during reward and avoidance learning. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci, 10(9), 1219-1227. [CrossRef]

- Klingberg, T., Forssberg, H., & Westerberg, H. (2002). Increased brain activity in frontal and parietal cortex underlies the development of visuospatial working memory capacity during childhood. J Cogn Neurosci, 14(1), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Kohls, G., Schulte-Rüther, M., Nehrkorn, B., Müller, K., Fink, G. R., Kamp-Becker, I., Herpertz-Dahlmann, B., Schultz, R. T., & Konrad, K. (2013). Reward system dysfunction in autism spectrum disorders. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci, 8(5), 565-572. [CrossRef]

- Kryza-Lacombe, M., Christian, I., Liuzzi, M., Owen, C., Hernandez, B., Dougherty, L., & Wiggins, J. (2020). Executive functioning moderates neural reward processing in youth. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 21. [CrossRef]

- Kuhnen, C. M., & Knutson, B. (2005). The neural basis of financial risk taking. Neuron, 47(5), 763-770. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H., Walker, Z. M., Hale, J. B., & Chen, S. H. A. (2017). Frontal-subcortical circuitry in social attachment and relationships: A cross-sectional fMRI ALE meta-analysis. Behavioural Brain Research, 325, 117-130. [CrossRef]

- Leggio, M., & Olivito, G. (2018). Topography of the cerebellum in relation to social brain regions and emotions. Handb Clin Neurol, 154, 71-84. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z., Nie, C., Zhang, Y., Chen, Y., & Yang, T. (2020). Evidence accumulation for value computation in the prefrontal cortex during decision making. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(48), 30728-30737. [CrossRef]

- Locke, H. S., & Braver, T. S. (2008). Motivational influences on cognitive control: Behavior, brain activation, and individual differences. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 8(1), 99-112. [CrossRef]

- Miller, E. K., & Cohen, J. D. (2001). An Integrative Theory of Prefrontal Cortex Function. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 24(1), 167-202. [CrossRef]

- Miyake, A., Friedman, N. P., Emerson, M. J., Witzki, A. H., Howerter, A., & Wager, T. D. (2000). The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex "Frontal Lobe" tasks: a latent variable analysis. Cogn Psychol, 41(1), 49-100. [CrossRef]

- Moreno-López, L., Stamatakis, E. A., Fernández-Serrano, M. J., Gómez-Río, M., Rodríguez-Fernández, A., Pérez-García, M., & Verdejo-García, A. (2012). Neural correlates of hot and cold executive functions in polysubstance addiction: association between neuropsychological performance and resting brain metabolism as measured by positron emission tomography. Psychiatry Res, 203(2-3), 214-221. [CrossRef]

- Moriguchi, Y. (2022). Relationship between cool and hot executive function in young children: A near-infrared spectroscopy study. Dev Sci, 25(2), e13165. [CrossRef]

- Motzkin, J. C., Baskin-Sommers, A., Newman, J. P., Kiehl, K. A., & Koenigs, M. (2014). Neural correlates of substance abuse: reduced functional connectivity between areas underlying reward and cognitive control. Hum Brain Mapp, 35(9), 4282-4292. [CrossRef]

- Nejati, V., Salehinejad, M. A., & Nitsche, M. A. (2018). Interaction of the Left Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex (l-DLPFC) and Right Orbitofrontal Cortex (OFC) in Hot and Cold Executive Functions: Evidence from Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS). Neuroscience, 369, 109-123. [CrossRef]

- Niendam, T. A., Laird, A. R., Ray, K. L., Dean, Y. M., Glahn, D. C., & Carter, C. S. (2012). Meta-analytic evidence for a superordinate cognitive control network subserving diverse executive functions. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 12(2), 241-268. [CrossRef]

- Padmala, S., & Pessoa, L. (2010). Interactions between cognition and motivation during response inhibition. Neuropsychologia, 48(2), 558-565. [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Titz, W., & Perry, R. P. (2002). Academic Emotions in Students' Self-Regulated Learning and Achievement: A Program of Qualitative and Quantitative Research. Educational Psychologist, 37(2), 91-105. [CrossRef]

- Peterburs, J., & Desmond, J. E. (2016). The role of the human cerebellum in performance monitoring. Curr Opin Neurobiol, 40, 38-44. [CrossRef]

- Pochon, J. B., Levy, R., Fossati, P., Lehericy, S., Poline, J. B., Pillon, B., Le Bihan, D., & Dubois, B. (2002). The neural system that bridges reward and cognition in humans: an fMRI study. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 99(8), 5669-5674. [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y., Galvan, A., Fuligni, A. J., Lieberman, M. D., & Telzer, E. H. (2015). Longitudinal Changes in Prefrontal Cortex Activation Underlie Declines in Adolescent Risk Taking. The Journal of Neuroscience, 35(32), 11308. [CrossRef]

- Quan, P., He, L., Mao, T., Fang, Z., Deng, Y., Pan, Y., Zhang, X., Zhao, K., Lei, H., Detre, J. A., Kable, J. W., & Rao, H. (2022). Cerebellum anatomy predicts individual risk-taking behavior and risk tolerance. NeuroImage, 254, 119148. [CrossRef]

- Rademacher, L., Krach, S., Kohls, G., Irmak, A., Gründer, G., & Spreckelmeyer, K. N. (2010). Dissociation of neural networks for anticipation and consumption of monetary and social rewards. NeuroImage, 49(4), 3276-3285. [CrossRef]

- Remijnse, P. L., Nielen, M. M., Uylings, H. B., & Veltman, D. J. (2005). Neural correlates of a reversal learning task with an affectively neutral baseline: an event-related fMRI study. NeuroImage, 26(2), 609-618. [CrossRef]

- Richard, J. M., Castro, D. C., Difeliceantonio, A. G., Robinson, M. J., & Berridge, K. C. (2013). Mapping brain circuits of reward and motivation: in the footsteps of Ann Kelley. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 37(9 Pt A), 1919-1931. [CrossRef]

- Rolls, E. T., Huang, C.-C., Lin, C.-P., Feng, J., & Joliot, M. (2020). Automated anatomical labelling atlas 3. NeuroImage, 206, 116189. [CrossRef]

- Roth, R. M., Isquith, P. K., & Gioia, G. A. (2005). Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function® - Adult Version (BRIEF-A).

- Roth, R. M., Lance, C. E., Isquith, P. K., Fischer, A. S., & Giancola, P. R. (2013). Confirmatory factor analysis of the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function-Adult version in healthy adults and application to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Clin Neuropsychol, 28(5), 425-434. [CrossRef]

- Salehinejad, M. A., Ghanavati, E., Rashid, M. H. A., & Nitsche, M. A. (2021). Hot and cold executive functions in the brain: A prefrontal-cingular network. Brain Neurosci Adv, 5, 23982128211007769. [CrossRef]

- Scarmeas, N., & Stern, Y. (2003). Cognitive reserve and lifestyle. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol, 25(5), 625-633. [CrossRef]

- Scott-Van Zeeland, A. A., Dapretto, M., Ghahremani, D. G., Poldrack, R. A., & Bookheimer, S. Y. (2010). Reward processing in autism. Autism Res, 3(2), 53-67. [CrossRef]

- Seghier, M. L. (2012). The Angular Gyrus: Multiple Functions and Multiple Subdivisions. The Neuroscientist, 19(1), 43-61. [CrossRef]

- Spreckelmeyer, K. N., Krach, S., Kohls, G., Rademacher, L., Irmak, A., Konrad, K., Kircher, T., & Gründer, G. (2009). Anticipation of monetary and social reward differently activates mesolimbic brain structures in men and women. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci, 4(2), 158-165. [CrossRef]

- Strathearn, L., Fonagy, P., Amico, J., & Montague, P. R. (2009). Adult attachment predicts maternal brain and oxytocin response to infant cues. Neuropsychopharmacology, 34(13), 2655-2666. [CrossRef]

- Tang, H., Bartolo, R., & Averbeck, B. B. (2021). Reward-related choices determine information timing and flow across macaque lateral prefrontal cortex. Nature Communications, 12(1), 894. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y., Zhang, W., Chen, K., Feng, S., Ji, Y., Shen, J., Reiman, E. M., & Liu, Y. (2006). Arithmetic processing in the brain shaped by cultures. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103(28), 10775-10780. [CrossRef]

- Todd, J. J., & Marois, R. (2004). Capacity limit of visual short-term memory in human posterior parietal cortex. Nature, 428(6984), 751-754. [CrossRef]

- Tsoi, L., Dungan, J., Waytz, A., & Young, L. (2016). Distinct neural patterns of social cognition for cooperation versus competition. NeuroImage, 137, 86-96. [CrossRef]

- Vallesi, A., Visalli, A., Gracia-Tabuenca, Z., Tarantino, V., Capizzi, M., Alcauter, S., Mantini, D., & Pini, L. (2022). Fronto-parietal homotopy in resting-state functional connectivity predicts task-switching performance. Brain Struct Funct, 227(2), 655-672. [CrossRef]

- van den Bos, W., Rodriguez, C. A., Schweitzer, J. B., & McClure, S. M. (2014). Connectivity strength of dissociable striatal tracts predict individual differences in temporal discounting. J Neurosci, 34(31), 10298-10310. [CrossRef]

- van den Bos, W., Rodriguez, C. A., Schweitzer, J. B., & McClure, S. M. (2015). Adolescent impatience decreases with increased frontostriatal connectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 112(29), E3765-3774. [CrossRef]

- Van Overwalle, F., Baetens, K., Mariën, P., & Vandekerckhove, M. (2014). Social cognition and the cerebellum: a meta-analysis of over 350 fMRI studies. NeuroImage, 86, 554-572. [CrossRef]

- Votinov, M., Myznikov, A., Zheltyakova, M., Masharipov, R., Korotkov, A., Cherednichenko, D., Habel, U., & Kireev, M. (2021). The Interaction Between Caudate Nucleus and Regions Within the Theory of Mind Network as a Neural Basis for Social Intelligence. Front Neural Circuits, 15, 727960. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Chen, B., Zhong, X., Hou, L., Zhang, M., Yang, M., Wu, Z., Chen, X., Mai, N., Zhou, H., Lin, G., Zhang, S., & Ning, Y. (2022). Static and dynamic functional connectivity variability of the anterior-posterior hippocampus with subjective cognitive decline. Alzheimers Res Ther, 14(1), 122. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Lv, C., He, Q., & Xue, G. (2020). Dissociable fronto-striatal functional networks predict choice impulsivity. Brain Struct Funct, 225(8), 2377-2386. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., & Ji, H. (2024). Hot and cool executive function in the development of behavioral problems in grade school. Dev Psychopathol, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., & Liu, Y. (2021). The Development of Internalizing and Externalizing Problems in Primary School: Contributions of Executive Function and Social Competence. Child Development, 92(3), 889-903. [CrossRef]

- Xin, F., & Lei, X. (2015). Competition between frontoparietal control and default networks supports social working memory and empathy. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci, 10(8), 1144-1152. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S., Pan, Y., Wang, Y., Spaeth, A. M., Qu, Z., & Rao, H. (2016). Real and hypothetical monetary rewards modulate risk taking in the brain. Scientific Reports, 6(1), 29520. [CrossRef]

- Xue, G., Lu, Z., Levin, I. P., & Bechara, A. (2010). The impact of prior risk experiences on subsequent risky decision-making: the role of the insula. NeuroImage, 50(2), 709-716. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Shields, G. S., Zhang, Y., Wu, H., Chen, H., & Romer, A. L. (2022). Child executive function and future externalizing and internalizing problems: A meta-analysis of prospective longitudinal studies. Clin Psychol Rev, 97, 102194. [CrossRef]

- Yin, H. H., Ostlund, S. B., & Balleine, B. W. (2008). Reward-guided learning beyond dopamine in the nucleus accumbens: the integrative functions of cortico-basal ganglia networks. Eur J Neurosci, 28(8), 1437-1448. [CrossRef]

- Zelazo, P. D., & Carlson, S. M. (2012). Hot and cool executive function in childhood and adolescence: Development and plasticity. Child Development Perspectives, 6, 354-360.

- Zhang, J., Hu, Y., Wang, Z., Wang, M., & Dong, G. H. (2020). Males are more sensitive to reward and less sensitive to loss than females among people with internet gaming disorder: fMRI evidence from a card-guessing task. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 357. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Li, M., Zhang, X., Zhang, D., Tan, H. Y., Yue, W., & Yan, H. (2022). Unsuppressed Striatal Activity and Genetic Risk for Schizophrenia Associated With Individual Cognitive Performance Under Social Competition. Schizophr Bull, 48(3), 599-608. [CrossRef]

| Measures | Mean (Standard deviation) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 25.55 (4.54) |

| BART_total (points) | 7777.59 (1937.21) |

| BRIEF_Inhibit* | 51.45 (9.04) |

| BRIEF_Shift* | 55 (8.73) |

| BRIEF_EmotionalControl* | 50.33 (9.31) |

| BRIEF_SelfMonitor* | 47.3 (8.65) |

| BRIEF_WorkingMemory* | 53.94 (9.21) |

| SPSRQ_Reward | 10.72 (4.17) |

| Go/No-Go_Overall Accuracy | 96.7% (2.6%) |

| Condition | Cluster | Volume | Cluster p(FWE) | T | x | y | z | label |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hot EF (High reward - Rest) | ||||||||

| No Compete | 1 | 7270 | 4.16*10-11 | 15.87 | -39 | -42 | 45 | Left parietal gyrus excluding supramarginal and angular gyrus |

| 14.98 | -27 | -3 | 57 | Left Superior frontal gyrus-dorsolateral | ||||

| 14.28 | -30 | 18 | 9 | Left insula | ||||

| 13.95 | -42 | 3 | 30 | Left Precentral gyrus | ||||

| 13.82 | -6 | 0 | 57 | Left supplementary motor area | ||||

| 12.13 | -54 | -24 | 45 | Left postcentral gyrus | ||||

| 12.12 | -45 | -36 | 42 | Left parietal gyrus excluding supramarginal and angular gyrus | ||||

| 12.10 | -27 | -57 | 48 | Left Superior parietal gyrus | ||||

| 11.91 | 30 | 18 | 6 | Right insula | ||||

| 11.41 | -45 | 0 | 42 | Left precentral gyrus | ||||

| 10.46 | 18 | 0 | 63 | Right superior frontal gyrus-dorsolateral | ||||

| 10.27 | 24 | -6 | 51 | Right precentral gyrus | ||||

| 8.91 | 45 | 3 | 33 | Right precentral gyrus | ||||

| 8.55 | 9 | 15 | 45 | Right supplementary motor area | ||||

| 2 | 608 | 0.000001 | 10.97 | -45 | -69 | -3 | Left middle occipital gyrus | |

| 8.38 | -42 | -51 | -30 | Left crus I of cerebellar hemisphere | ||||

| 7.65 | -27 | -54 | -30 | Left crus VI of cerebellar hemisphere | ||||

| 6.48 | -42 | -84 | -6 | Left inferior occipital gyrus | ||||

| 6.14 | -33 | -90 | -9 | Left inferior occipital gyrus | ||||

| 3 | 2416 | 2.22*10-16 | 6.62 | 0 | -45 | -15 | Lobule III of vermis | |

| 9.05 | 42 | -54 | -33 | Right Crus I of cerebellar hemisphere | ||||

| 9.03 | 30 | -48 | -33 | Right Lobule VI of cerebellar hemisphere | ||||

| 9.02 | 18 | -66 | -48 | Right Lobule VIII of cerebellar hemisphere | ||||

| 8.74 | 39 | -60 | -30 | Right Crus I of cerebellar hemisphere | ||||

| 8.71 | 24 | -57 | -27 | Right Lobule VI of cerebellar hemisphere | ||||

| 8.70 | 12 | -72 | -45 | Right Lobule VII of cerebellar hemisphere | ||||

| 7.96 | 15 | -48 | -21 | Right Lobule IV-V of cerebellar hemisphere | ||||

| 7.39 | 9 | -69 | -24 | Right Lobule VI of cerebellar hemisphere | ||||

| 7.17 | 6 | -66 | -27 | Lobule VII of vermis | ||||

| 7.05 | 51 | -69 | -6 | Right inferior temporal gyrus | ||||

| 6.58 | -24 | -66 | -51 | Left Lobule VIII of cerebellar hemisphere | ||||

| 4 | 647 | 7.67*10-7 | 9.59 | 39 | -42 | 48 | Right parietal gyrus excluding supramarginal and angular gyrus | |

| 5.38 | 27 | -60 | 54 | Right superior parietal gyrus | ||||

| 5.16 | 15 | -63 | 54 | Right precuneus | ||||

| 4.45 | 30 | -66 | 27 | Right superior occipital gyrus | ||||

| Compete | 1 | 6621 | 1.72*10-10 | 15.01 | -39 | -42 | 45 | Left parietal gyrus excluding supramarginal and angular gyrus |

| 12.82 | -6 | 0 | 60 | Left supplementary motor area | ||||

| 12.79 | -27 | -57 | 48 | Left superior parietal gyrus | ||||

| 12.5 | -27 | -3 | 57 | Left superior frontal gyrus-dorsolateral | ||||

| 12.46 | -45 | 0 | 30 | Left precentral gyrus | ||||

| 12.39 | -30 | 15 | 9 | Left insula | ||||

| 12.32 | -3 | 3 | 57 | Left supplementary motor area | ||||

| 12.06 | -24 | -6 | 60 | Left superior frontal gyrus-dorsolateral | ||||

| 11.66 | -48 | -3 | 45 | Left Precentral gyrus | ||||

| 11.43 | -6 | 9 | 51 | Left supplementary motor area | ||||

| 9.9 | 24 | -3 | 54 | Right Precentral gyrus | ||||

| 9.26 | 15 | 3 | 57 | Right supplementary motor area | ||||

| 7.92 | -39 | -54 | -30 | Left crus I of cerebellar hemisphere | ||||

| 2 | 1719 | 8.22*10-14 | 9.19 | 18 | -51 | -24 | Right Lobule IV-V of cerebellar hemisphere | |

| 9.16 | 30 | -48 | -30 | Right Lobule VI of cerebellar hemisphere | ||||

| 9.08 | 3 | -57 | -12 | Lobule IV-V of vermis | ||||

| 8.75 | 27 | -57 | -27 | Right Lobule VI of cerebellar hemisphere | ||||

| 8.43 | 12 | -72 | -45 | Right Lobule VIII of cerebellar hemisphere | ||||

| 8.1 | 0 | -45 | -21 | Lobule III of vermis | ||||

| 8.02 | 18 | -63 | -48 | Right Lobule VIII of cerebellar hemisphere | ||||

| 7.74 | 0 | -45 | -15 | Lobule III of vermis | ||||

| 7.42 | 3 | -66 | -33 | Lobule III of vermis | ||||

| 6.37 | -21 | -69 | -51 | Right Lobule VIII of cerebellar hemisphere | ||||

| 3 | 591 | 8.56*10-7 | 8.93 | 36 | -45 | 48 | Right parietal gyrus excluding supramarginal and angular gyrus | |

| 7.75 | 45 | -36 | 48 | Right parietal gyrus excluding supramarginal and angular gyrus | ||||

| 4 | 187 | 0.004 | 8.05 | 45 | -66 | -6 | Right inferior temporal gyrus | |

| 6.10 | 45 | -81 | -6 | Right inferior occipital gyrus | ||||

| Cool EF (No reward - Rest) | ||||||||

| No compete | 1 | 4056 | 3.38*10-10 | 14.61 | -6 | 0 | 57 | Left supplementary motor area |

| 11.35 | -27 | -3 | 57 | Left superior frontal gyrus-dorsolateral | ||||

| 9.99 | -30 | 18 | 9 | Left insula | ||||

| 9.85 | -45 | -33 | 45 | Left parietal gyrus excluding supramarginal and angular gyrus | ||||

| 9.57 | -54 | -21 | 48 | Left postcentral gyrus | ||||

| 9.48 | -42 | 0 | 30 | Left precentral gyrus | ||||

| 9.31 | -48 | 0 | 42 | Left precentral gyrus | ||||

| 9.06 | -39 | -42 | 45 | Left parietal gyrus excluding supramarginal and angular gyrus | ||||

| 7.87 | -27 | -54 | 45 | Left parietal gyrus excluding supramarginal and angular gyrus | ||||

| 7.03 | -54 | -18 | 24 | Left postcentral gyrus | ||||

| 7.01 | -48 | -30 | 60 | Left postcentral gyrus | ||||

| 6.81 | 18 | 0 | 63 | Right superior frontal gyrus-dorsolateral | ||||

| 5.76 | -39 | 27 | 33 | Left middle frontal gyrus | ||||

| 2 | 473 | 0.00003 | 7.07 | 30 | -48 | -30 | Right lobule VI of cerebellar hemisphere | |

| 7.00 | 42 | -54 | -33 | Right crus I of cerebellar hemisphere | ||||

| 6.76 | 39 | -60 | -30 | Right crus I of cerebellar hemisphere | ||||

| 5.87 | 15 | -51 | -21 | Right lobule IV-V of cerebellar hemisphere | ||||

| 4.90 | 6 | -54 | -15 | Lobule IV-V of vermis | ||||

| 4.58 | 0 | -45 | -15 | Lobule III of vermis | ||||

| 3 | 297 | 0.001 | 7.02 | 21 | -66 | -51 | Right lobule VIII of cerebellar hemisphere | |

| 6.97 | 24 | -69 | -54 | Right lobule VIII of cerebellar hemisphere | ||||

| 4.97 | 6 | -78 | -45 | Right lobule VIIB of cerebellar hemisphere | ||||

| 4 | 176 | 0.009 | 7.00 | -42 | -69 | -3 | Left middle occipital gyrus | |

| 5.64 | -42 | -84 | -6 | Left inferior occipital gyrus | ||||

| 5 | 376 | 0.0002 | 6.80 | 30 | 18 | 9 | Right insula | |

| 6.12 | 48 | 3 | 30 | Right precentral gyrus | ||||

| 6.02 | 51 | 6 | 21 | Right precentral gyrus | ||||

| 6 | 280 | 0.001 | 6.40 | 48 | -33 | 48 | Right parietal gyrus excluding supramarginal and angular gyrus | |

| 5.92 | 39 | -42 | 48 | Right parietal gyrus excluding supramarginal and angular gyrus | ||||

| 4.78 | 45 | -45 | 60 | Right superior parietal gyrus | ||||

| 4.61 | 30 | -54 | 45 | Right parietal gyrus excluding supramarginal and angular gyrus | ||||

| Compete | 1 | 5661 | 3.39*10-10 | 14.6 | -3 | 3 | 57 | Left supplementary motor area |

| 14.38 | -3 | 9 | 54 | Left supplementary motor area | ||||

| 14.28 | -6 | 0 | 60 | Left supplementary motor area | ||||

| 13.83 | -9 | -3 | 63 | Left supplementary motor area | ||||

| 12.67 | -27 | -3 | 54 | Left superior frontal gyrus-dorsolateral | ||||

| 11.32 | -33 | 15 | 9 | Left insula | ||||

| 10.71 | -45 | -3 | 42 | Left precentral gyrus | ||||

| 10.51 | -48 | -33 | 48 | Left postcentral gyrus | ||||

| 10.34 | -45 | 0 | 30 | Left precentral gyrus | ||||

| 9.9 | 27 | 0 | 51 | Right precentral gyrus | ||||

| 9.78 | -54 | 6 | 30 | Left precentral gyrus | ||||

| 9.64 | -36 | -42 | 48 | Left parietal gyrus excluding supramarginal and angular gyrus | ||||

| 9.32 | -51 | 3 | 21 | Left precentral gyrus | ||||

| 9.06 | -27 | -57 | 48 | Left superior parietal gyrus | ||||

| 2 | 1229 | 1.3*10-11 | 9.20 | 30 | -51 | -30 | Right lobule VI of cerebellar hemisphere | |

| 8.13 | 3 | -57 | -12 | Lobule IV-V of vermis | ||||

| 8.01 | 39 | -60 | -30 | Right Crus I of cerebellar hemisphere | ||||

| 7.76 | 18 | -60 | -45 | Right lobule VIII of cerebellar hemisphere | ||||

| 7.64 | 21 | -66 | -48 | Right lobule VIII of cerebellar hemisphere | ||||

| 6.11 | 12 | -45 | -24 | Right lobule III of cerebellar hemisphere | ||||

| 4.11 | 3 | -75 | -30 | Lobule VII of vermis | ||||

| 3 | 190 | 0.002 | 9.17 | -39 | -54 | -30 | Left Crus I of cerebellar hemisphere | |

| 4 | 450 | 0.000006 | 7.66 | 51 | -33 | 48 | Right parietal gyrus excluding supramarginal and angular gyrus | |

| 7.49 | 48 | -36 | 51 | Right parietal gyrus excluding supramarginal and angular gyrus | ||||

| 7.37 | 36 | -42 | 45 | Right parietal gyrus excluding supramarginal and angular gyrus | ||||

| 5.89 | 30 | -54 | 45 | Right parietal gyrus excluding supramarginal and angular gyrus | ||||

| 4.06 | 15 | -63 | 54 | Right Precuneus | ||||

| 5 | 228 | 0.001 | 7.62 | -42 | -69 | 0 | Left middle occipital gyrus | |

| 4.61 | -42 | -84 | -6 | Left inferior occipital gyrus | ||||

| 6 | 170 | 0.004 | 6.97 | 45 | -66 | -6 | Right inferior temporal gyrus | |

| 5.71 | 42 | -84 | -6 | Right inferior occipital gyrus | ||||

| 5.54 | 48 | -78 | -3 | Right inferior occipital gyrus | ||||

| Hot - Cool EF | ||||||||

| No Compete | 1 | 12249 | 0.0003 | 7.87 | 5.67 | 33 | 3 | Right insula |

| 7.06 | 30 | -36 | 3 | Right Hippocampus | ||||

| 6.66 | -15 | 15 | 12 | Left caudate nucleus | ||||

| 6.6 | -12 | -15 | 18 | Left ventral lateral nucleus | ||||

| 6.48 | -30 | -51 | 60 | Left superior parietal gyrus | ||||

| 6.42 | 24 | -9 | 60 | Right superior frontal gyrus-dorsolateral | ||||

| 6.19 | -21 | -57 | 63 | Left superior parietal gyrus | ||||

| Compete | 1 | 392 | 0.001 | 4.78 | 18 | -54 | 45 | Right precuneus |

| 3.59 | 15 | 12 | 21 | Right caudate nucleus | ||||

| No Compete - Compete | 1 | 387 | 0.0004 | 5.27 | 33 | -87 | -6 | Right inferior occipital gyrus |

| 5.23 | 27 | -90 | 9 | Right middle occipital gyrus | ||||

| 4.53 | 21 | -81 | -6 | Right lingual gyrus | ||||

| 4.35 | 36 | -57 | -18 | Right fusiform gyrus | ||||

| 3.97 | 30 | -69 | -18 | Right fusiform gyrus | ||||

| 2 | 216 | 0.007 | 4.86 | -30 | -78 | -6 | Left fusiform gyrus | |

| 4.41 | -24 | -87 | 15 | Left middle occipital gyrus | ||||

| 4.25 | -21 | -90 | 12 | Left superior occipital gyrus | ||||

| 3.84 | -21 | -78 | -18 | Left Lobule VI of cerebellar hemisphere | ||||

| 3.77 | -12 | -90 | 15 | Left cuneus | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).