Submitted:

14 November 2024

Posted:

18 November 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

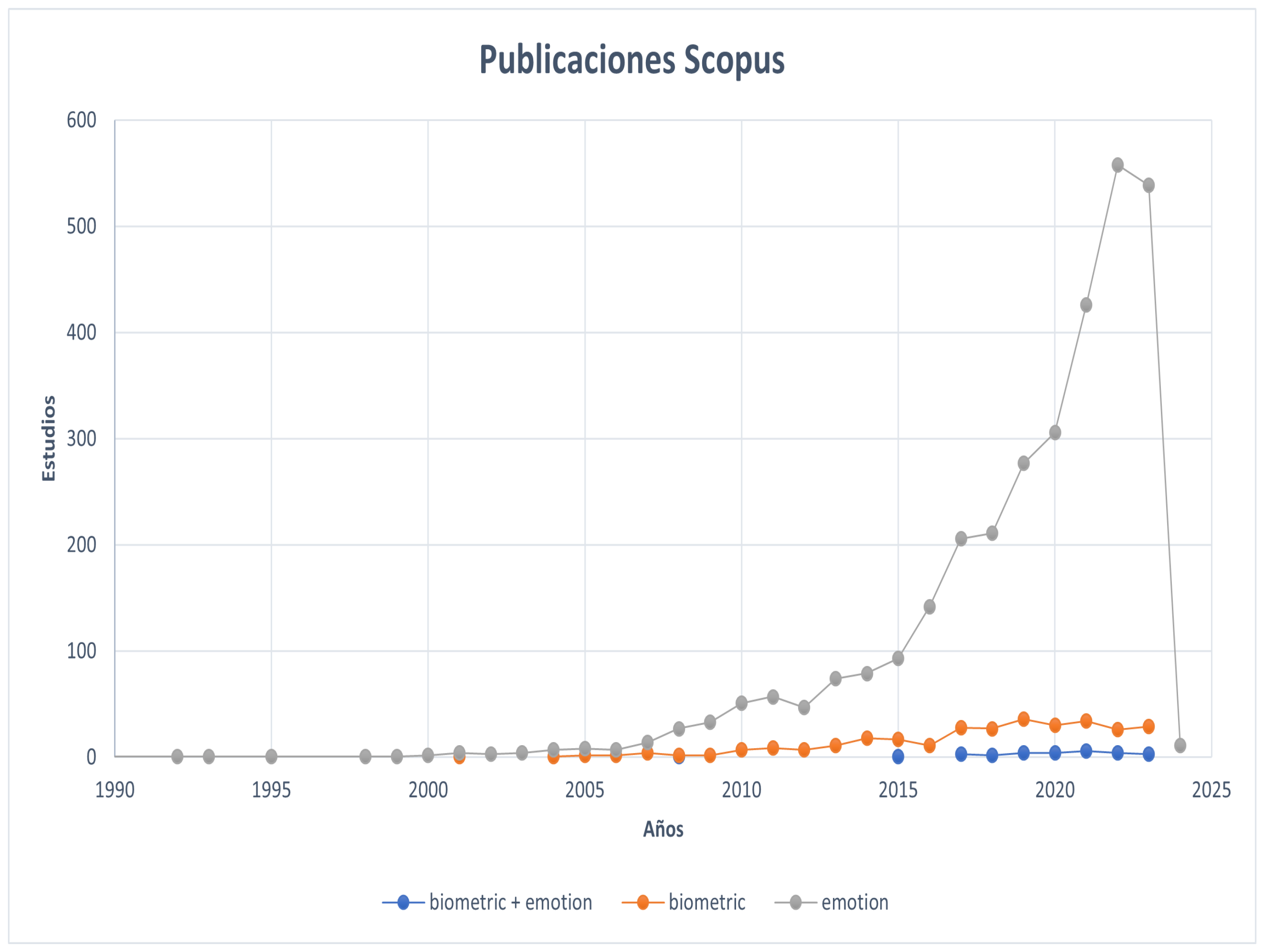

2. Literature Review Process

3. Electroencephalography (EEG): Foundations and Applications

3.1. Brain Anatomy Relevant to EEG

3.2. EEG Signals and Their Properties

| Cite | Database | Feature Extraction | Clasification Method | Accuracy | Year |

| [27] | Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (PTB) database and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology-Beth Israel Hospital (MIT-BIH) arrhythmia database | The time-domain feature extraction method is a semi-fiducial procedure that uses the Pan-Tompkins algorithm to detect the R wave peaks of the QRS complexes, and then selects fixed-width time segments for further dimensionality reduction and feature extraction | Only sed the newly proposed Method, but they do not mention the method | PTB 98.6% sensitivity. 90.6% sensitivity (MIT-BIH) | 2023 |

| [28] | They have used two SSVEP datasets for pi, the speller dataset and the EPOC dataset | auto-regressive (AR) modeling, power spectral density (PSD) energy of EEG channels, wavelet packet decomposition (WPD), and phase locking values (PLV). | combines common spatial patterns with specialized deep-learning neural networks. | recognition rate of 99 | 2023 |

| [29] | The paper doesn’t mention the name of the dataset; it only includes citation 32. Upon reviewing the article, it appears that the dataset used is BCI200 | The system uses a Random Forest based binary feature selection method to filter out meaningless channels and determine the optimum number of channels for the highest accuracy | Hybrid Attention-based LSTM-MLP | 99.96% and 99.70% accuracy percentages for eyes-closed and eyes-open datasets | 2023 |

| [30] | The authors used the dataset of ’Big Data of 2-classes MI’ and Dataset IVa | In this study, we used CSP, ERD/S, AR, and FFT to transform segmented data into informative features. The TDP method is excluded from this work because it is suitable for motor execution rather than motor imagination | SVM, GNB | SVM (CSP (98.97%), ERD/S (98.94%), AR (98.93%), and FFT (97.92%)).GNB (CSP (97.47%), ERD/S (94.58%), FFT (53.80%), and AR (50.24%)). | 2023 |

| [31] | Dataset I was the main one and con-sisted of a self-collected dataset using a non-expensive EEG device. Dataset II was used to test the proposed method with a large number of subjects. This is a widely used dataset from PhysioNet BCI [41]. | EEG signals were processed using the FieldTrip toolbox for Matlab. The toolbox provides various useful tools to process EEG, MEG, and invasive electrophysiological data. EEG signals were processed by first applying a baseline correction relative to the mean voltage, and then a finite impulse response (FIR) bandpass filter from 5 to 40 Hz for noise reduction. These preprocessing steps were necessary to smooth the classification procedures and remove or minimize undesired noise nuisance. | Support Vector Machines (SVM), Neural Networks (NN), and Discriminant Analysis (DA). | identification accuracy rates of up to 100% with a low-cost EEG device | 2023 |

| Cita | Base de datos | Extraccion de caracteristicas | metodos de clasificacion | exactitud | año |

| [32] | dataset | uses only two EEG channels and a signal measured over a short temporal window of 5 seconds | CNN | identification result of 99% and an equal error rate of authentication performance of 0.187%. | 2023 |

| [33] | dataset which can be found on the Kaggle repository (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/msambare/fer2013). UTKFace dataset | The article does not mention de preprocessing | KNN, SVM, and deep learning techniques like CNN and VGG-16 with transfer learning | SVM model with an F1 score of 0.83 for age detection and 0.46 for facial emotion recognition, and with less computation involved the current VGG model achieved an accuracy of 95.31% in the validation phase | 2023 |

| [34] | The data is collected from 50 volunteer | 1) spectral information, 2) coherence, 3) mutual correlation coefficient, and 4) mutual information. | SVM | authentication error rate (ERR) was found to be 0.52%, with a classification rate of 99.06%. | 2023 |

| [35] | WeSAD and the MIT-BIH Arrhythmia databases | uses two waveform similarity distances, namely Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) and Time Series Forest (TSF), to provide features for classification. Additionally, the paper proposes a new feature extraction method called the ECG Morphological Feature Extraction (EMFE) method. | k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN), Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forest (RF), and Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) | ..... | 2023 |

| [36] | DEAP | phase locking value (PLV) | CNN | 85% | 2023 |

| [37] | SEED and DEAP | The proposed model uses an Inventive brain optimization algorithm and frequency features to enhance detection accuracy. | optimized deep convolutional neural network (DCNN) K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest (RF), and Deep Belief Network (DBN). | (DCNN) model achieved an accuracy of 97.12% at 90% of training and 96.83% according to K-fold analysis | 2023 |

| Cita | Base de datos | Extraccion de caracteristicas | metodos de clasificacion | exactitud | año |

| [38] | SEED https://github.com/heibaipei/ DE-CNNv in this link we can find the code of this article | The proposed method consists of the following steps: Obtaining the time-frequency content of EEG signals using the modified Stockwell transform. Extracting deep features from each channel’s time-frequency content using a deep convolutional neural network. Fusing the reduced features of all channels to construct the final feature vector. Utilizing semi-supervised dimension reduction to reduce the features. | CNNs The Inception-V3 CNN and support vector machine (SVM) classifier | ... | 2023 |

| [39] | DEAP | 10-fold cross-validation has been employed for all experiments and scenarios. Sequential floating forward feature (SFFS) selection has been used to select the best features for classification | Support Vector Machine (SVM) with Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel has been applied for classification | In our study the CCR is in the range of 88%-99%, whilst the Equal Error Rate (EER) in the aforementioned research is in the range of 15%-35% using SVM | 2017 |

| [40] | DEAP, MAHNOB-HCI, and SEED | The feature extraction process involved the use of time-domain and frequency-domain features | classification algorithms used were Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forest (RF), and k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN). | ..... | 2021 |

| [41] | They collected theirs data – 60 users using Emotiv Epoc+ | the signals are filtered by Savitzky-Golay filter to attenuate its short term variations | Hidden Markov Model (HMM) based temporal classifier and Support Vector Machine (SVM) | User identification performance of 97.50% and 93.83% have been recorded with HMM and SVM classifiers, respectively. | 2017 |

3.3. Feature Extraction from EEG Signals

4. Emotion Recognition and Biometric Identification Using EEG

4.1. Biometric from EEG Signals

| Cita | Preproceso | Base de datos | Extracción y selección | Clasificación biométrica | Exactitud |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Kamaraju et al., 2023) | Multivariate variational mode decomposition (MVMD) | Base de datos propia (35 sujetos) | Fourier-Bessel series expansion-based (FBSE) entropies | K-NN | 93.4 ± 7.0% |

| (Ortega-Rodríguez et al., 2023) | FieldTrip, bandpass 4-40 Hz, beta frequency band 13-30 Hz | Base de datos propia (13 personas) y PhysioNet BCI (109 personas) | PCA, Wilcoxon test, fast Fourier transform, Power Spectrum (PS), Asymmetry index | RBF-SVM, K-fold, Cross-validation | 99.9 ± 1.39% |

| (M. Benomar, Steven Cao, Manoj Vishwanath, Khuong Quoc Vo, 2022) | PREP pipeline, notch filter, standardScaler, high pass filter 1 Hz, low pass filter 50 Hz | The BED (Biometric EEG Dataset) 21 sujetos | PCA, Wilcoxon test, optimal spatial filtering | Deep learning (DL) | 86.74% |

| (Tian et al., 2023) | - | https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-99-0479-2_294 | Functional connectivity (FC) | Multi-stream GCN (MSGCN) | 98.05% |

| (Kralikova et al., 2022) | Notch filter, Bandpass filter, common average reference (CAR) | Base de datos propia (21 sujetos) | 1D-CNN | Cross 5-fold, LDA, SVM, K-NN, DL | 99% |

| (Wibawa et al., 2022) | Finite Impulse Response (FIR), Automatic Artifact Removal EOG (AAR-EOG), Artifact Subspace Reconstruction (ASR), and Independent Component Analysis (ICA) | Base de datos propia (43 sujetos) | Power Spectral Density (PSD) | Naive Bayes, Neural Network, SVM | 97.7% |

| (Hendrawan et al., 2022) | ICA, Butterworth filter | Base de datos propia (8 sujetos) | Power Spectral Density (PSD) from delta (0.5–4 Hz), theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–14 Hz), beta (14–30 Hz), gamma (30–50 Hz) bands, LDA | K-NN, SVM | 80% |

| (Lai et al., 2022) | - | PhysioBank database (109) | CNN | CNN-ECOC-SVM | 98.49% |

| (Jijomon & Vinod, 2018) | Matlab edfread, 7.5 second window | PhysioNet database (109) | Power spectral, PSD, Mean Correlation Coefficient (MCC) | Método propuesto por el autor | Error rate of 0.016 |

| (Waili et al., 2019) | 2nd order Butterworth filter | Base de datos propia (6 sujetos) | Daubechies (db8) wavelet, PSD | Multilayer Perceptron Neural Network (MLPNN) | 75.8% |

| (Jijomon Chettuthara Monsy, 2020) | Matlab edfread | PhysioNet database (16 sujetos) | Frequency-weighted power (FWP) | Método propuesto por el autor | EER of 0.0039 |

4.2. Emotion Recognition from EEG Signals

4.3. Emotion-Aware Biometric Identification

| Autores | Año | Preproceso | Extracción y selección | Clasificación de emociones |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Murugappan, Nagarajan Ramachandran | 2010 | Filtro de superficie Laplaceano | Transformada wavelet, Fuzzy C Means (FCM) y Fuzzy K-Means (FKM) | Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) y K Nearest Neighbor (K-NN) |

| You-Yun Lee, Shulan Hsich | 2014 | FFT, EEGLAB | Correlación, Coherencia y sincronización de fase | Análisis de discriminante cuadrático |

| Daniela Iacovielloa, Andrea Petraccab | 2015 | Filtro wavelet | PCA | SVM |

| Nitin Kumar, Kaushikee Khaund | 2015 | Blind source separation, Filtro de paso de banda 4.0-45.0 Hz | HOSA (Higher order Spectral Analysis) | LS-SVM, Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) |

| Nitin Kumar, Kaushikee Khaund | 2016 | Filtro Butterworth | Análisis Biespectral con HOSA | SVM |

| G. Mejía, A. Gómez | 2016 | Filtros Butterworth | Transformada wavelet estacionaria | Quadratic discriminant analysis (QDA) |

| Yong Zhang, Xiaomin Ji | 2016 | Algoritmo basado en Análisis Independiente de Componentes | Entropía de muestras, Entropía Cuadrática, Distribución de Entropía | SVM |

| Beatriz García | 2016 | Algoritmo basado en Análisis de Componentes Independientes | Entropía de muestras, Entropía Cuadrática, Distribución de Entropía | SVM |

| Yasar Dasdemir, Esen Yildirim | 2017 | EEGLAB, MARA, AAR | Valor de bloqueo de fase (PLV) con ANOVA para medir significancia | SVM |

| Moon Inder Singh, Mandeep Singh | 2017 | Filtro de superficie Laplaceano | Transformada wavelet | SVM Polinomial |

| Baharch Nakisa, Mohammad Naim Rastgoo | 2018 | Filtro Butterworth y Notch | Algoritmos ACA, SA, GA, SPO | SVM |

| Jia Wen Li, Xiangyu Zeng, Huiming Zhao | 2023 | DWT, EMD | Smoothed pseudo-Wigner–Ville distribution (RSPWVD) | K-NN, SVM, LDA y LR |

| Georgia SOVATZIDI, Dimitris K. IAKOVIDIS | 2023 | Finite Impulse Response, Artefact Subspace Reconstruction (ASR) | Power Spectral Density (PSD) | Naïve Bayes (NB), K-NN, SVM, Fuzzy Cognitive Map (FCM) |

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zapata, J.C.; Duque, C.M.; Gonzalez, M.E.; Becerra, M.A. Data Fusion Applied to Biometric Identification—A Review. Advances in Computing and Data Sciences 2017, 721, 721–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; An, X.; Di, Y.; Zhang, L.; Ming, D. Review on identity feature extraction methods based on electroencephalogram signals. 2021, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhadj, F. Biometric system for identification and authentication. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Revelo, M.; Ortega-Adarme, M.; Peluffo-Ordoñez, D.; Alvarez-Uribe, K.; Becerra, M. Comparison among physiological signals for biometric identification. 2017, 10585 LNCS. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyasseri, Z.A.A.; Alomari, O.A.; Makhadmeh, S.N.; Mirjalili, S.; Al-Betar, M.A.; Abdullah, S.; Ali, N.S.; Papa, J.P.; Rodrigues, D.; Abasi, A.K. EEG Channel Selection for Person Identification Using Binary Grey Wolf Optimizer. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 10500–10513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi Alkareem Alyasseri, Z.; Alomari, O.A.; Al-Betar, M.A.; Awadallah, M.A.; Hameed Abdulkareem, K.; Abed Mohammed, M.; Kadry, S.; Rajinikanth, V.; Rho, S. EEG Channel Selection Using Multiobjective Cuckoo Search for Person Identification as Protection System in Healthcare Applications. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience 2022, 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwan, S.H.; El-Telbany, M.; Arafa, W.; Ali, R.A. Deep Learning Approaches for Personal Identification Based on EGG Signals. Lecture Notes on Data Engineering and Communications Technologies 2022, 100, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrawan, M.A.; Saputra, P.Y.; Rahmad, C. Identification of optimum segment in single channel EEG biometric system. Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science 2021, 23, 1847–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, D.; Dixit, V.V. Hybrid classification model for emotion detection using electroencephalogram signal with improved feature set. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2025, 100, 106893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Yang, S. TVRP-based constructing complex network for EEG emotional feature analysis and recognition. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2024, 96, 106606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, A. DEEPHER: Human Emotion Recognition Using an EEG-Based DEEP Learning Network Model. Engineering Proceedings 2021, 10, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakalle, A.; Tomar, P.; Bhardwaj, H.; Acharya, D.; Bhardwaj, A. A LSTM based deep learning network for recognizing emotions using wireless brainwave driven system. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvão, F.; Alarcão, S.M.; Fonseca, M.J. Predicting exact valence and arousal values from EEG. Predicting exact valence and arousal values from EEG 2021, 21, 3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiorana, E. Deep learning for EEG-based biometric recognition. Neurocomputing 2020, 410, 374–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabowo, D.W.; Nugroho, H.A.; Setiawan, N.A.; Debayle, J. A systematic literature review of emotion recognition using EEG signals. Cognitive Systems Research 2023, 82, 101152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, M.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X. Multi-modal emotion recognition using EEG and speech signals. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2022, 149, 105907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouka, N.; Fourati, R.; Fdhila, R.; Siarry, P.; Alimi, A.M. EEG channel selection-based binary particle swarm optimization with recurrent convolutional autoencoder for emotion recognition. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2023, 84, 104783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Hu, Z.; Chen, W.; Zhang, S.; Liang, Z.; Li, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z. M3CV: A multi-subject, multi-session, and multi-task database for EEG-based biometrics challenge. NeuroImage 2022, 264, 119666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, M.C.; Scheibel, A.B.; Elson, L.M. libro de trabajo el Cerebro Humano. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Romeo Urrea, H. El Dominio de los Hemisferios Cerebrales. Ciencia Unemi 2015, 3, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamma, E. Left Brain Vs. Right Brain: Hemisphere Function, 2023.

- Sciotto, E.A.; Niripil, E.B. Salud En La Educación Ondas Cerebrales, Conciencia Y Cognición. Salud en la educación 2018. [Google Scholar]

- García Domínguez, A.E. Análisis de ondas cerebrales para determinar emociones a partir de estímulos visuales. 2015, 137. [Google Scholar]

- Changoluisa Romero, D.P.; Escalante Viteri, F.J. Diseño e implementación de un sistema de adquisición de ondas cerebrales (EEG) de seis canales y análisis en tiempo, frecuencia y coherencia. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Caballero, P.A.O. Diseño De Mecanismos De Procesamiento Interactivos Para EL Analisis de ondas cerebrales. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lundqvist, M.; Herman, P.; Warden, M.R.; Brincat, S.L.; Miller, E.K. Gamma and beta bursts during working memory readout suggest roles in its volitional control. Nature Communications 2018, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, D.; Luengo, D. Efficient Clustering-Based electrocardiographic biometric identification. Expert Systems with Applications 2023, 219, 119609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oikonomou, V.P. Human Recognition Using Deep Neural Networks and Spatial Patterns of SSVEP Signals. 2023, 23, 2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcı, F. DM-EEGID: EEG-Based Biometric Authentication System Using Hybrid Attention-Based LSTM and MLP Algorithm. Traitement Du Signal 2023, 40, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, S.J.; Jeong, J. User Biometric Identification Methodology via EEG-Based Motor Imagery Signals. IEEE Access 2023, XX. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Rodríguez, J.; Martín-Chinea, K.; Gómez-González, J.F.; Pereda, E. Brainprint based on functional connectivity and asymmetry indices of brain regions: A case study of biometric person identification with non-expensive electroencephalogram headsets. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsumari, W.; Hussain, M.; Alshehri, L.; Aboalsamh, H.A. EEG-Based Person Identification and Authentication Using Deep Convolutional Neural Network. Axioms 2023, 12, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teja Chavali, S.; Tej Kandavalli, C.; Sugash, T.M.; Subramani, R. Smart Facial Emotion Recognition With Gender and Age Factor Estimation. Procedia Computer Science 2023, 218, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TajDini, M.; Sokolov, V.; Kuzminykh, I.; Ghita, B. Brainwave-based authentication using features fusion. Computers and Security 2023, 129, 103198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bıçakcı, H.S.; Santopietro, M.; Guest, R. Activity-based electrocardiogram biometric verification using wearable devices. IET Biometrics 2023, 12, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Li, X.; Touyama, H. Emotion recognition based on group phase locking value using convolutional neural network. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khubani, J.; Kulkarni, S. Inventive deep convolutional neural network classifier for emotion identification in accordance with EEG signals. Social Network Analysis and Mining 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zali-Vargahan, B.; Charmin, A.; Kalbkhani, H.; Barghandan, S. Deep time-frequency features and semi-supervised dimension reduction for subject-independent emotion recognition from multi-channel EEG signals. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2023, 85, 104806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahid, A.; Arbabi, E. Human identification with EEG signals in different emotional states. In Proceedings of the 2016 23rd Iranian Conference on Biomedical Engineering and 2016 1st International Iranian Conference on Biomedical Engineering, ICBME 2016; 2017; pp. 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnau-González, P.; Arevalillo-Herráez, M.; Katsigiannis, S.; Ramzan, N. On the Influence of Affect in EEG-Based Subject Identification. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing 2021, 12, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, B.; Singh, D.; Roy, P.P. A Novel framework of EEG-based user identification by analyzing music-listening behavior. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2017, 76, 25581–25602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, B.; Sierra, J.E.; Ulloa, A.B. Técnicas de extracción de características de señales EEG en la imaginación de movimiento para sistemas BCI. Extraction techniques of EEG signals characteristics in motion imagination for BCI systems. Espacios 2018, 39, 36–48. [Google Scholar]

- Manuel. Análisis en el dominio de la frecuencia - Análisis de Fourier 2005. p. 27.

- Colominas, M.A. Métodos guiados por los datos para el análisis de señales: contribuciones a la descomposición empírica en modos. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lara, L.; Stoico, C.; Machado, R.; Castagnino, M. Estimación de los exponentes de lyapunov. 2003, XXII, 1441–1451. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, A.; Bolle, R.; Pankanti, S. Introduction to biometrics. International Conference on Pattern Recognition 2008, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer-Camino, D.; Alarcon-Aquino, V. Recent advances in biometrics and its standardization: a survey. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Wallberg, K. ECG Biometric Recognition by Convolutional Neural Networks with Transfer Learning Using Random Forest Approach. Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies (Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies) 2022, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H. EEG-Based Biometric Close-Set Identification Using CNN-ECOC-SVM. 2021, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.Q.; Ibrahim, H.; Suandi, S.A.; Abdullah, M.Z. Convolutional Neural Network for Closed-Set Identification from Resting State Electroencephalography. 2022, 10, 3442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Lo, F.P.W.; Lo, B. EEG-based user identification system using 1D-convolutional long short-term memory neural networks. 2019, 125, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliraman, B.; Nain, S.; Verma, R.; Thakran, M.; Dhankhar, Y.; Hari, P.B. Pre-processing of EEG signal using Independent Component Analysis. 2022, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, M.; Nakazawa, M.; Nishikawa, Y.; Abe, N. Examination and It’s Evaluation of Preprocessing Method for Individual Identification in EEG. 2020, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhawna, K.; Priyanka; Duhan, M. Electroencephalogram Based Biometric System: A Review. Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering 2021, 668, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, D.; Lende, M.; Lathia, K.; Shirgurkar, S.; Kumar, N.; Madrecha, S.; Bhardwaj, A. Comparative Analysis of Feature Extraction Technique on EEG-Based Dataset. 2020, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carla, F.; Yanina, W.; Daniel Gustavo, P. ¿Cuántas Son Las Emociones Básicas? Anuario de Investigaciones 2017, 26, 253–257. [Google Scholar]

- Gantiva, C.; Camacho, K. CARACTERISTICAS DE LA RESPUESTA EMOCIONAL GENERADA POR LAS PALABRAS: UN ESTUDIO EXPERIMENTAL DESDE LA EMOCIÓN Y LA MOTIVACIÓN. 2016, 10, 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Koelstra, S.; Muhl, C.; Soleymani, M.; Lee, J.S.; Yazdani, A.; Ebrahimi, T.; Pun, T.; Nijholt, A.; Patras, I. DEAP: A Database for Emotion Analysis; Using Physiological Signals. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleymani, M.; Lichtenauer, J.; Pun, T.; Pantic, M. A Multimodal Database for Affect Recognition and Implicit Tagging. 2012, 3, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.L.; Guo, H.T.; Lu, B.L. Revealing critical channels and frequency bands for emotion recognition from EEG with deep belief network. In Proceedings of the 2015 7th International IEEE/EMBS Conference on Neural Engineering (NER); IEEE, 2015; pp. 154–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekmekcioglu, E.; Cimtay, Y. Loughborough University Multimodal Emotion Dataset-2. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, Z.Y.; Saidatul, A.; Vijean, V.; Ibrahim, Z. Non Linear Features Analysis between Imaginary and Non-imaginary Tasks for Human EEG-based Biometric Identification. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2019, 557, 012033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brás, S.; Ferreira, J.H.T.; Soares, S.C.; Pinho, A.J. Biometric and Emotion Identification: An ECG Compression Based Method. Frontiers in Psychology 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.X.; Mao, Z.J.; Yao, W.X.; Huang, Y.F. EEG-based biometric identification with convolutional neural network. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2020, 79, 10655–10675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandharipande, M.; Chakraborty, R.; Kopparapu, S.K. Modeling of Olfactory Brainwaves for Odour Independent Biometric Identification. In Proceedings of the 2023 31st European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO); IEEE, 2023; pp. 1140–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Wang, C.; Ruan, Q. DE-CNN: An Improved Identity Recognition Algorithm Based on the Emotional Electroencephalography. Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine 2020, 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque-Mejía, C.; Castro, A.; Duque, E.; Serna-Guarín, L.; Lorente-Leyva, L.L.; Peluffo-Ordóñez, D.; Becerra, M.A. Methodology for biometric identification based on EEG signals in multiple emotional states; [Metodología para la identificación biométrica a partir de señales EEG en múltiples estados emocionales]. RISTI - Revista Iberica de Sistemas e Tecnologias de Informacao 2023, 2023, 281–288. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Yao, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Chen, W.; Boots, R. Cascade and Parallel Convolutional Recurrent Neural Networks on EEG-based Intention Recognition for Brain Computer Interface. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benomar, M.; Cao, S.; Vishwanath, M.; Vo, K.; Cao, H. Investigation of EEG-Based Biometric Identification Using State-of-the-Art Neural Architectures on a Real-Time Raspberry Pi-Based System. 2022, 22, 9547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrawan, M.A.; Rosiani, U.D.; Sumari, A.D. Single Channel Electroencephalogram (EEG) Based Biometric System. Information Technology International Seminar (ITIS) 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jijomon Chettuthara Monsy, A.P.V. EEG-based biometric identification using frequency-weighted power feature. The Institution of Engineering and Technology 2020, 9, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalaly Bidgoly, A.; Jalaly Bidgoly, H.; Arezoumand, Z. A survey on methods and challenges in EEG based authentication. Computers and Security 2020, 93, 101788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Zhu, J.; Song, T.; Chang, H. Subject-Independent EEG Emotion Recognition Based on Genetically Optimized Projection Dictionary Pair Learning. 2023, 13, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuvaraj, R.; Baranwal, A.; Prince, A.A.; Murugappan, M.; Mohammed, J.S. Emotion Recognition from Spatio-Temporal Representation of EEG Signals via 3D-CNN with Ensemble Learning Techniques. Emerging Trends of Biomedical Signal Processing in Intelligent Emotion Recognition 2023, 13, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, X.; Huang, D.; Sun, Y.; Huang, S.; Huang, H.; Ming, D. Transformer-based ensemble deep learning model for EEG-based emotion recognition. Brain science advances 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Zheng, X. EEG Emotion Recognition Based on Temporal and Spatial Features of Sensitive signals. Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering 2022, 2022, 5130184:1–5130184:8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Dong, S.Y. Deep learning-based self-induced emotion recognition using EEG. Frontiers in neuroscience 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, X.; Lv, X.; Yang, P.; Liu, K.; Sun, K. Emotion Recognition Method Based on EEG in Few Channels. Data Driven Control and Learning Systems (DDCLS) 2022, 1291–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).