Submitted:

15 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

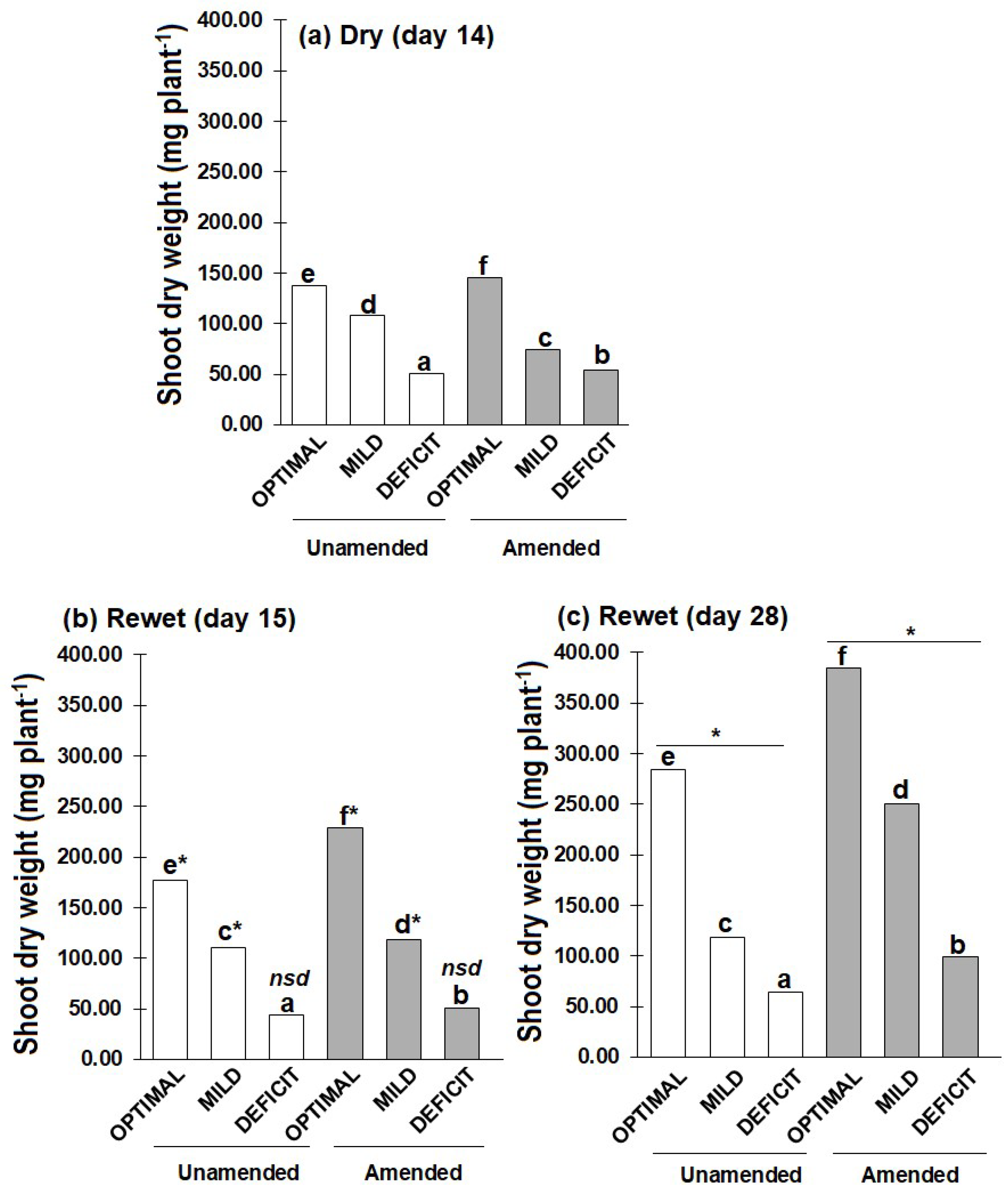

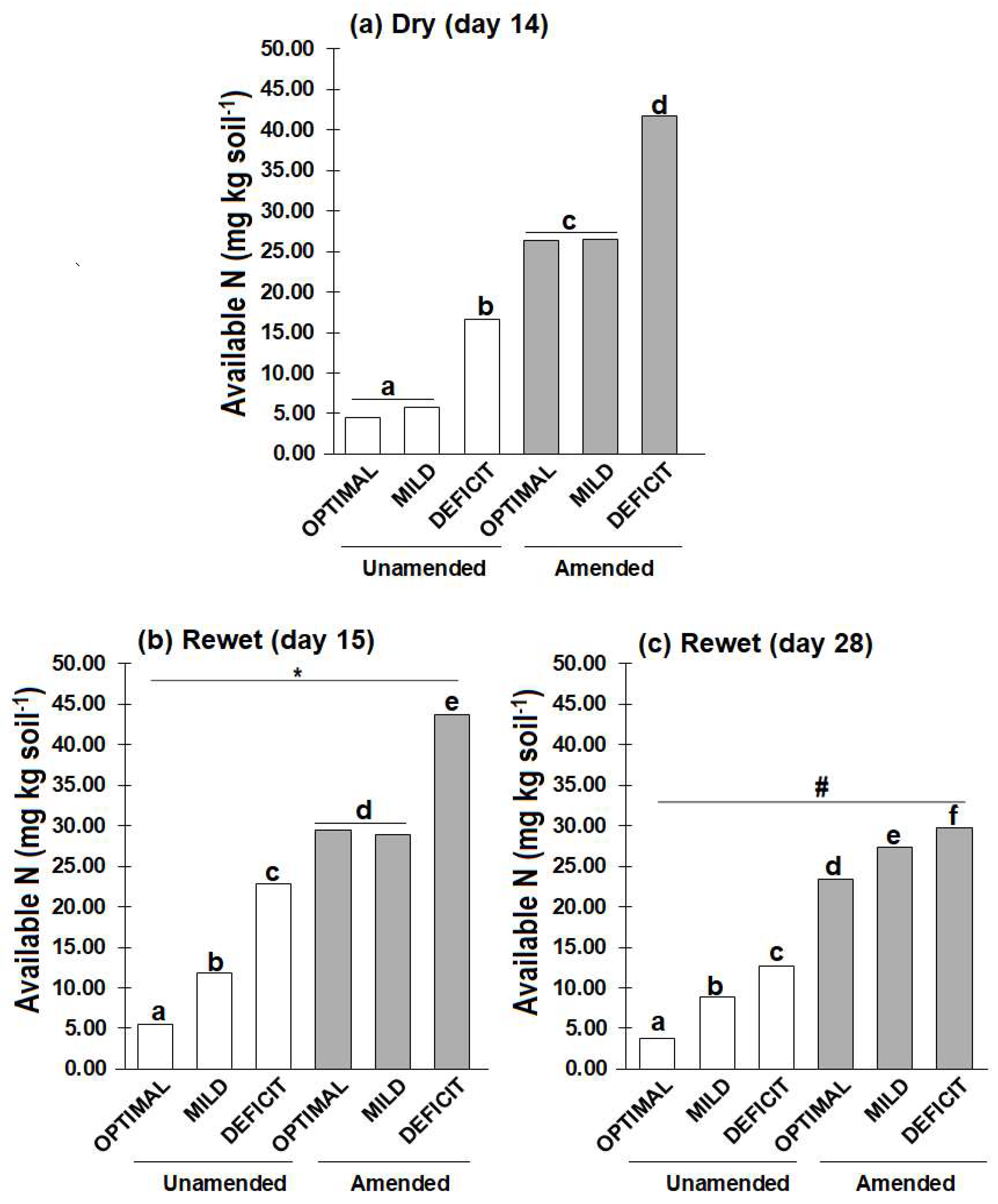

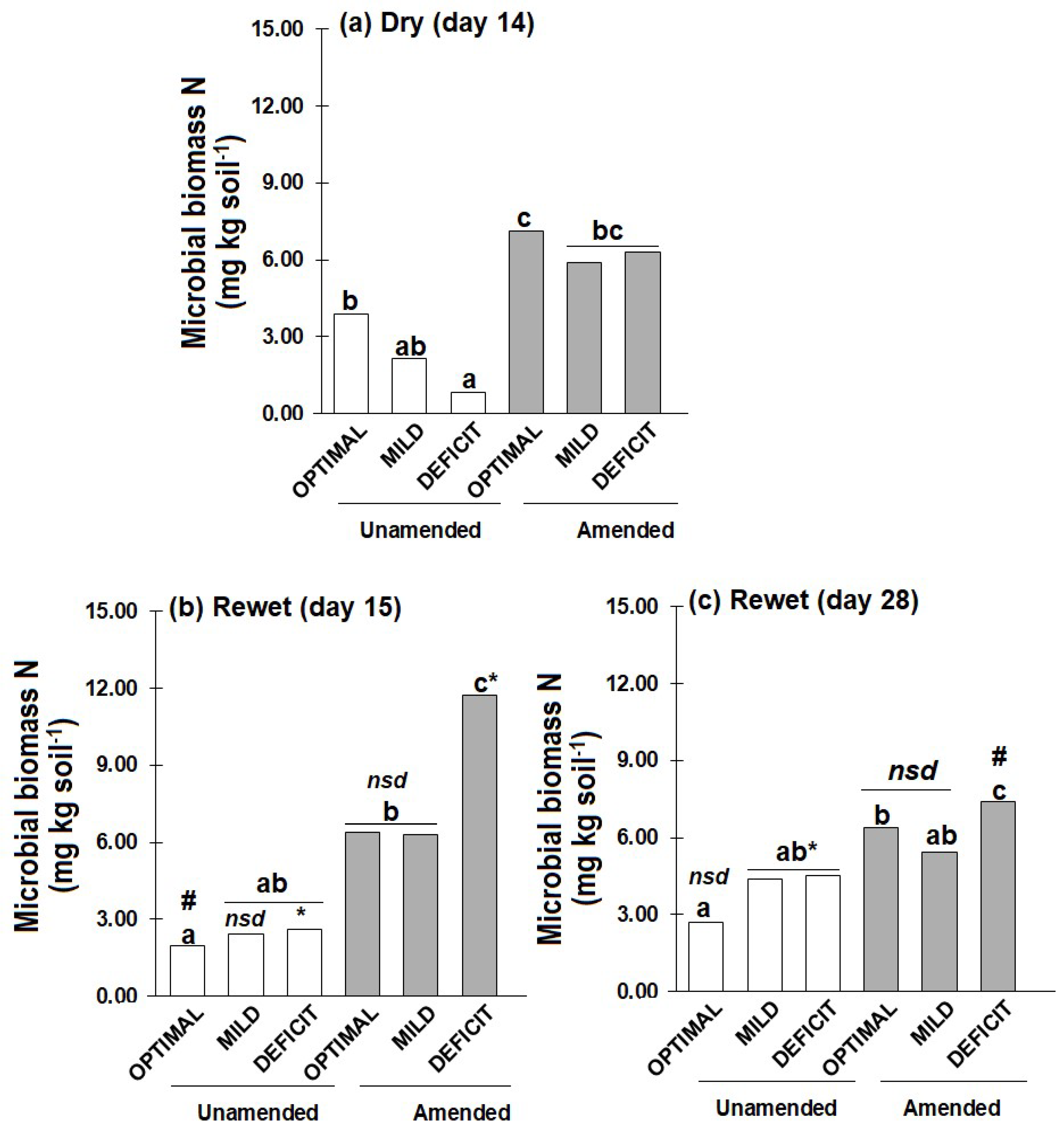

With predicted increase in the intervals between rainfall events becoming more apparent, little is known about how short-term (few weeks) drought events influence plant growth and nitrogen (N) uptake after rewetting, and how this legacy effect is modulated by drought intensity and soil amendment. Methods: Soil (50% water holding capacity, WHC) unamended or amended with faba bean residue (C/N 9) was planted with wheat for two weeks. Thereafter, drought was imposed by reducing soil water content to 10% (DEFICIT) or 30% (MILD) WHC and maintained for two weeks (days 0 to 14). Thereafter, soils (deficit and mild) were rewetted to 50% WHC and maintained at this water content for additional two weeks. Control soils were maintained at 50% WHC (OPTIMAL) throughout the experiment. Results: At the end of the dry period, shoot dry weight was about 60% lower in DEFICIT than OPTIMAL. Contrarily, soil available N was higher in DEFICIT (16.65-41.72 mg kg-1) than OPTIMAL (4.57-26.42 mg kg-1). While MBN did not differ with amendment, it was about 80% lower in DEFICIT than OPTIMAL without amendment. During the two-weeks after rewetting (days 15 to 28), shoot dry weight, N concentration and available N changed little without amendment. But in the amended soil particularly in DEFICIT treatments, shoot dry weight nearly doubled, shoot N concentration increased by about 40%, plant N uptake increased by about 70%, and MBN decreased by about 40%. However, shoot dry weight and plant N uptake were still lower than the OPTIMAL. Conclusion: The reduced plant growth, shoot N concentration and plant N uptake induced by a short period of drying (<30% WHC) is not compensated by increased growth and N uptake after rewetting.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Plant Growth, shoot N Concentration and N Uptake

2.2. Soil Available N and Microbial Biomass N

3. Discussion

3.1. Dry Period

3.2. After Rewetting

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Soil and Crop Residues

4.2. Experimental Design

4.3. Analyses

4.4. Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPCC. “Climate Change and Land: An Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems.” edited by P.R. Shukla, J. Skeg, E. Calvo Buendia, V. Masson-Delmotte, H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, P. Zhai, R. Slade, S. Connors, S. van Diemen, M. Ferrat, E. Haughey, S. Luz, M. Pathak, J. Petzold, J. Portugal Pereira, P. Vyas, E. Huntley, K. Kissick, M. Belkacemi and J. Malley, 864. Geneva, 2019.

- Manzoni, S., Chakrawal, A., Fischer, T., Schimel, J.P., Porporato, A., and Vico, G. Rainfall Intensification Increases the Contribution of Rewetting Pulses to Soil Heterotrophic Respiration. Biogeosciences 2020, 17, (15): 4007-4023. [CrossRef]

- Borken, W., and Matzner, E. Reappraisal of Drying and Wetting Effects on C and N Mineralization and Fluxes in Soils. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2009, 15, (4): 808-824. [CrossRef]

- Canarini, A., and Dijkstra, F.A. Dry-Rewetting Cycles Regulate Wheat Carbon Rhizodeposition, Stabilization and Nitrogen Cycling. J. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 81: 195-203. [CrossRef]

- Tecon, R., and Or, D. Biophysical Processes Supporting the Diversity of Microbial Life in Soil. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 41, (5): 599-623. [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, M.K., Klein, T., Jansen, S., Choat, B., and Sack, L. The Correlations and Sequence of Plant Stomatal, Hydraulic, and Wilting Responses to Drought. J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2016, 113, (46): 13098-13103. [CrossRef]

- Scoffoni, C., and Sack, L. The Causes and Consequences of Leaf Hydraulic Decline with Dehydration. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, (16): 4479-4496. [CrossRef]

- Verslues, P.E., and Longkumer, T. Size and Activity of the Root Meristem: A Key for Drought Resistance and a Key Model of Drought--Related Signaling. Physiol. Plant. 2022, 174, (1): e13622. [CrossRef]

- García, I., Mendoza, R., and Pomar, M.C. Deficit and Excess of Soil Water Impact on Plant Growth of Lotus Tenuis by Affecting Nutrient Uptake and Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Symbiosis. Plant Soil 2008, 304: 117-131. [CrossRef]

- He, M., and Dijkstra, F.A. Drought Effect on Plant Nitrogen and Phosphorus: A Meta--Analysis. New Phytol. 2014, 204, (4): 924-931. [CrossRef]

- Xue, R., Shen, Y., and Marschner, P. Low Soil Water Content During Plant Growth Influences Soil Respiration and Microbial Biomass after Plant Removal and Rewetting. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2016, 16, (4): 955-966. [CrossRef]

- Bogati, K., and Walczak, M. The Impact of Drought Stress on Soil Microbial Community, Enzyme Activities and Plants. Agronomy 2022, 12, (1): 189. [CrossRef]

- Erinle, K.O., Doolette, A., and Marschner, P. Changes in Phosphorus Pools in the Detritusphere Induced by Removal of P or Switch of Residues with Low and High C/P Ratio. Biol. Fert. Soils 2020, 56, (1): 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Lund, V., and Goksøyr, J.J. Effects of Water Fluctuations on Microbial Mass and Activity in Soil. Microb. Ecol. 1980, 6: 115-123. [CrossRef]

- Schimel, J.P. Life in Dry Soils: Effects of Drought on Soil Microbial Communities and Processes. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2018, 49, (1): 409-432. [CrossRef]

- Erinle, K.O., and Marschner, P. Soil Water Availability Influences P Pools in the Detritusphere of Crop Residues with Different C/P Ratios. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2019, 19, (4): 771-779. [CrossRef]

- Bista, D.R., Heckathorn, S.A., Jayawardena, D.M., Mishra, S., and Boldt, J.K. Effects of Drought on Nutrient Uptake and the Levels of Nutrient-Uptake Proteins in Roots of Drought-Sensitive and-Tolerant Grasses. Plants 2018, 7, (2): 28. [CrossRef]

- Kolter, R., Siegele, D.A., and Tormo, A. The Stationary Phase of the Bacterial Life Cycle. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1993, 47: 855-875. [CrossRef]

- Bünemann, E.K., Keller, B., Hoop, D., Jud, K., Boivin, P., and Frossard, E. Increased Availability of Phosphorus after Drying and Rewetting of a Grassland Soil: Processes and Plant Use. Plant Soil 2013, 370: 511-526. [CrossRef]

- Butterly, C.R. Drying/Rewetting Cycles in Southern Australian Agricultural Soils: Effects on Turnover of Soil Phosphorus, Carbon and the Microbial Biomass. Ph.D, The University of Adelaide, South Australia, 2008.

- Sardans, J., and Peñuelas, J. Increasing Drought Decreases Phosphorus Availability in an Evergreen Mediterranean Forest. Plant Soil 2004, 267: 367-377. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, N. Soil Microbial Activity and Community Structure as Affected by Osmotic and Matric Potential. Ph.D, University of Adelaide, South Australia, 2011.

- Zhu, B., and Cheng, W. Impacts of Drying–Wetting Cycles on Rhizosphere Respiration and Soil Organic Matter Decomposition. J. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2013, 63: 89-96. [CrossRef]

- Li, L., Ma, H., Xing, J., Liu, F., and Wang, Y. Effects of Water Deficit and Nitrogen Application on Leaf Gas Exchange, Phytohormone Signaling, Biomass and Water Use Efficiency of Oat Plants. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2020, 183, (6): 695-704. [CrossRef]

- Hammad, H.M., Farhad, W., Abbas, F., Fahad, S., Saeed, S., Nasim, W., and Bakhat, H.F. Maize Plant Nitrogen Uptake Dynamics at Limited Irrigation Water and Nitrogen. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24: 2549-2557. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, K.D., Beier, C., Michelsen, A., and Emmett, B.A. Effects of Experimental Drought on Microbial Processes in Two Temperate Heathlands at Contrasting Water Conditions. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2003, 24, (2): 165-176. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., Shi, S., Lin, F., Hao, Z., Jiang, P., and Dai, G. Effects of Soil Water and Nitrogen on Growth and Photosynthetic Response of Manchurian Ash (Fraxinus Mandshurica) Seedlings in Northeastern China. PloS one 2012, 7, (2): e30754. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X., Zhang, Y., Ji, X., Downing, A., and Serpe, M. Combined Effects of Nitrogen Deposition and Water Stress on Growth and Physiological Responses of Two Annual Desert Plants in Northwestern China. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2011, 74: 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Buckley, T.N. How Do Stomata Respond to Water Status? J New Phytol 2019, 224, (1): 21-36.

- Schimel, J.P., and Bennett, J. Nitrogen Mineralization: Challenges of a Changing Paradigm. Ecology 2004, 85, (3): 591-602.

- Ali, S., Dongchu, L., Jing, H., Ahmed, W., Abbas, M., Qaswar, M., Anthonio, C.K., Lu, Z., Boren, W., and Yongmei, X. Soil Microbial Biomass and Extracellular Enzymes Regulate Nitrogen Mineralization in a Wheat-Maize Cropping System after Three Decades of Fertilization in a Chinese Ferrosol. J. Soil Sediment 2021, 21: 281-294. [CrossRef]

- Geisseler, D., and Horwath, W.R. Relationship between Carbon and Nitrogen Availability and Extracellular Enzyme Activities in Soil. Pedobiologia 2009, 53, (1): 87-98. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Hou, L., Liu, M., Lin, X., Li, Y., and Li, S. Primary Effects of Extracellular Enzyme Activity and Microbial Community on Carbon and Nitrogen Mineralization in Estuarine and Tidal Wetlands. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99: 2895-2909. [CrossRef]

- Barnard, R.L., Osborne, C.A., and Firestone, M.K. Responses of Soil Bacterial and Fungal Communities to Extreme Desiccation and Rewetting. The ISME J. 2013, 7, (11): 2229-2241. [CrossRef]

- Fierer, N., and Schimel, J.P. Effects of Drying–Rewetting Frequency on Soil Carbon and Nitrogen Transformations. J. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2002, 34, (6): 777-787. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, A., and Or, D. Hydration and Diffusion Processes Shape Microbial Community Organization and Function in Model Soil Aggregates. J Water Resour. Res. 2015, 51, (12): 9804-9827. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z., Bian, H., Xu, L., Li, M., and He, N. Pulse Effect of Precipitation: Spatial Patterns and Mechanisms of Soil Carbon Emissions. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9: 673310. [CrossRef]

- Cousins, O.H., Garnett, T.P., Rasmussen, A., Mooney, S.J., Smernik, R.J., Brien, C.J., and Cavagnaro, T.R. Variable Water Cycles Have a Greater Impact on Wheat Growth and Soil Nitrogen Response Than Constant Watering. J. Plant Sci. 2020, 290: 110146. [CrossRef]

- Erinle, K.O., Li, J., Doolette, A., and Marschner, P. Soil Phosphorus Pools in the Detritusphere of Plant Residues with Different C/P Ratio—Influence of Drying and Rewetting. Biol. Fert. Soils 2018, 54: 841-852. [CrossRef]

- Ge, G., and Or, D. “Particle Size Analysis.” In Methods of Soil Analysis. Part 4. Physical Methods, edited by J. Dane and G. Topp, 255-294. Madison, USA: Soil Science Society of America, 2002.

- Rayment, G., and Higginson, F.R. Australian Laboratory Handbook of Soil and Water Chemical Methods. Melbourne: Inkata Press Pty Ltd., 1992.

- Walkley, A., and Black, I.A. An Examination of the Degtjareff Method for Determining Soil Organic Matter, and a Proposed Modification of the Chromic Acid Titration Method. Soil Sci. 1934, 37, (1): 29-38. [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, H., and Wallace, H.S. The Kjeldahl Determination of Nitrogen: A Critical Study of Digestion Conditions-Temperature, Catalyst, and Oxidizing Agent. Aust. J. Chem. 1954, 7, (1): 55-70. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N., Singh, R.J., and Kumar, K. Dry Matter Accumulation and Nutrient Uptake by Wheat (Triticum Aestivum L.) under Poplar (Populus Deltoides) Based Agroforestry System. Int. Sch. Res. Notices. 2012, 2012, (1): 359673.

- Willis, R.B., Montgomery, M.E., and Allen, P.R. Improved Method for Manual, Colorimetric Determination of Total Kjeldahl Nitrogen Using Salicylate. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1996, 44, (7): 1804-1807. [CrossRef]

- Miranda, K.M., Espey, M.G., and Wink, D.A. A Rapid, Simple Spectrophotometric Method for Simultaneous Detection of Nitrate and Nitrite. Nitric oxide 2001, 5, (1): 62-71. [CrossRef]

- Moore, J., Klose, S., and Tabatabai, M. Soil Microbial Biomass Carbon and Nitrogen as Affected by Cropping Systems. Biol. Fert. Soils 2000, 31: 200-210. [CrossRef]

| Amendment | Moisture treatment | (a) Dry period | (b) After rewetting | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 14 | Day 15 | Day 28 | |||

| Shoot N concentration (mg g-1) | |||||

| Unamended | OPTIMAL | 26.94±0.17cC | 21.03±0.10dB | 7.76±0.99aA | |

| MILD | 22.07±0.25bC | 19.11±0.04cB | 12.03±0.05bA | ||

| DEFICIT | 17.25±0.16aB | 15.57±0.58aA | 16.85±0.11dB | ||

| Amended | OPTIMAL | 30.05±0.18eC | 26.41±0.31fB | 14.19±0.23cA | |

| MILD | 29.03±0.03dC | 24.00±0.21eB | 15.87±0.04dA | ||

| DEFICIT | 22.52±0.13bB | 17.33±0.09bA | 28.55±0.22eC | ||

| N uptake (mg plant-1) | |||||

| Unamended | OPTIMAL | 3.69±0.03eB | 3.71±0.03eB | 2.21±0.28cA | |

| MILD | 2.40±0.03dA | 2.11±0.00cA | 1.43±0.01bA | ||

| DEFICIT | 0.87±0.01aB | 0.69±0.03aA | 1.09±0.01aC | ||

| Amended | OPTIMAL | 4.38±0.04fA | 6.04±0.08fC | 5.46±0.09fB | |

| MILD | 2.16±0.00cA | 2.85±0.02dB | 3.98±0.01eC | ||

| DEFICIT | 1.23±0.00bB | 0.88±0.01bA | 2.82±0.02dC | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).